Abstract

We present a case of severe bowel perforation during lenvatinib treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Although the Hartmann's procedure was performed, the patient died 48 h after the operation. The histopathological findings suggested that lenvatinib was involved in the etiology of bowel perforation in this case.

Keywords: Lenvatinib, Bowel perforation, Hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Lenvatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that was developed as a molecular targeting agent and inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 1–3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1–4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, stem cell factor receptor, and rearranged during transfection proto-oncogene. All of which play key roles in tumor angiogenesis [1].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common neoplasm worldwide and has a high mortality rate. Patients with HCC typically exhibit high levels of VEGF expression. Sorafenib, a TKI that blocks the VEGF signal transduction pathway, was the first anticancer agent used for metastatic HCC. Although sorafenib is generally well tolerated and has an acceptable toxicity profile, gastrointestinal perforation has been reported as a rare adverse event [2].

Recently, lenvatinib has become a first-line agent that may have better efficacy in HCC with nonhepatitis C etiology and advanced HCC without portal vein thrombosis. Lenvatinib was associated with significant improvements compared with sorafenib in terms of higher objective response rate and longer progression-free survival. Lenvatinib is typically well tolerated, with the most common treatment-emergent adverse events including hypertension, diarrhea, and decreased appetite [3]. Gastrointestinal toxicity is one of the most drastic side effects of lenvatinib. Although lenvatinib-induced small intestine perforation has been previously described, no studies have reported colon perforation due to lenvatinib [4].

Case Report

A 78-year-old woman was diagnosed with HCC at our hospital after presenting with abdominal pain. She had a history of hypertension, liver cirrhosis, and antibodies for hepatitis C virus for more than 10 years. Computed tomography revealed advanced HCC measuring 7.5 cm with portal invasion and a few daughter nodules. As this HCC presentation exceeded the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer extended criteria, the patient underwent medical intervention.

Lenvatinib was initiated at 8 mg/day. The treatment was interrupted 2 months later when she developed proteinuria. Lenvatinib was subsequently resumed at 4 mg/day after 10 months of discontinuation. One week before visiting the emergency department, she was feeling unsteady on her feet while walking and would vomit immediately after ingesting small amounts of food. She presented with respiratory distress, urge incontinence, and night sweats.

The initial evaluation indicated dehydration and shock. Blood pressure was not measurable, and she had a heart rate of 137 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 33 breaths/min, and a body temperature of 36.4°C. Her abdomen was soft and nontender with no guarding. Laboratory tests revealed the following: white blood cells: 15,700/μL, hemoglobin: 16.0 g/dL, platelets: 216,000/μL, creatinine: 2.90 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein: 18.2 mg/L.

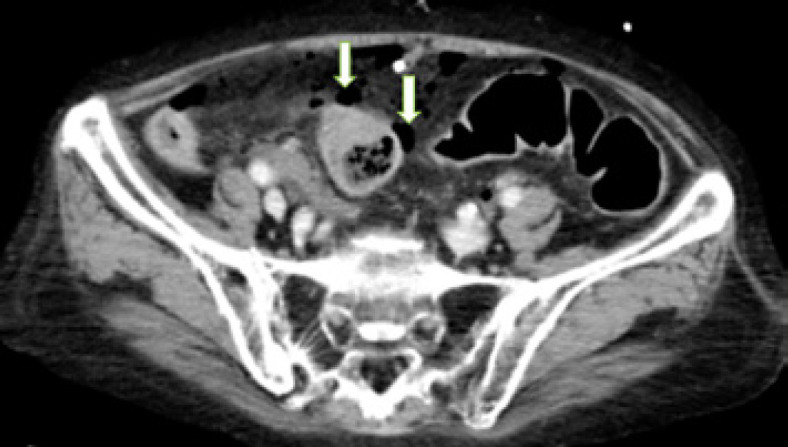

Computed tomography showed free air bubbles in the abdomen and pelvis near the large bowel (Fig. 1). Subsequently, an emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed, where peritonitis with a purulent exudate was identified in the lower abdomen. A focally necrotic and well-circumscribed perforation was detected on the antemesenteric surface of the sigmoid colon. We performed a Hartmann's procedure with a 15-cm sigmoid resection and created an end colostomy. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit postoperatively, but the patient died 48 h after emergent surgery with no improvement in the sepsis.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography scan indicating free air bubbles (arrows) in the abdomen and pelvis.

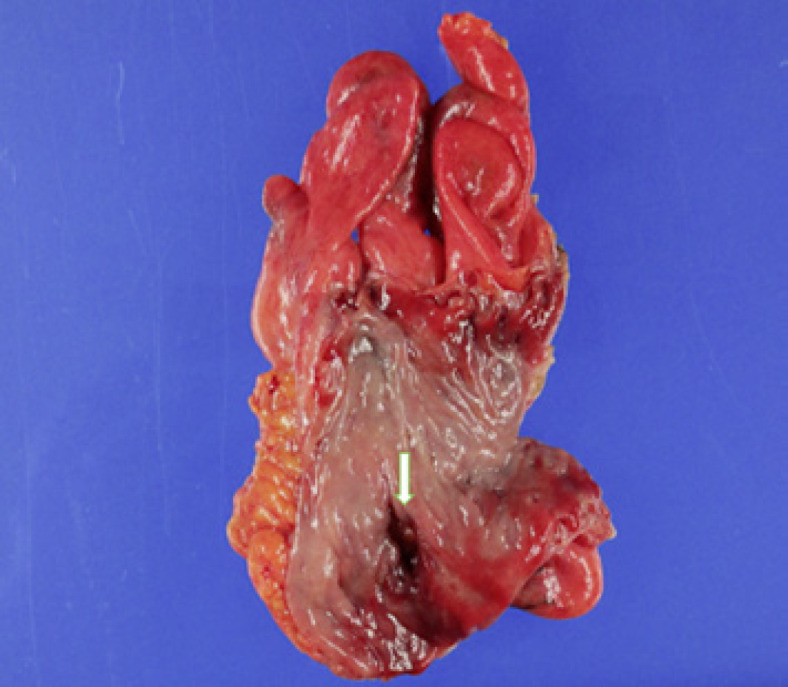

Macroscopic examination of the resected sigmoid (Fig. 2) colon specimen was grossly unremarkable except for a hole with a diameter of about 1.0 cm. Histopathological examination (Fig. 3) revealed infiltration of neutrophils and hemorrhage around the perforation site but no malignant lesion. Thus, lenvatinib-related bowel perforation was suspected based on the conspicuous mitotic arrest in the colonic epithelium with numerous mitotic spindles around the perforation site.

Fig. 2.

Resected sigmoid specimen showing the perforation site (arrow) and grossly unremarkable mucosa.

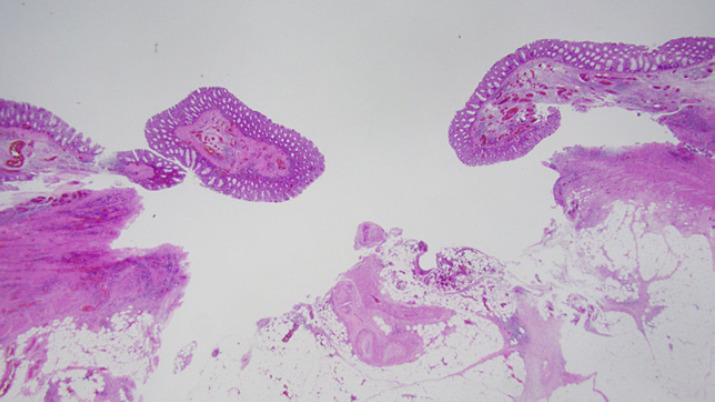

Fig. 3.

Histopathologic examination of the perforation site. Staining, hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×4.

Discussion

The mortality rate from HCC has been increasing over the past 20 years. Lenvatinib inhibits the kinase activity of VEGF receptors and has been demonstrated to have antitumor activity in HCC by inhibiting angiogenesis.

The toxicity profile of TKIs is reported to include hypertension, hand-foot syndrome, bleeding, arterial thromboembolism, and hematologic reactions [5]. Only a few cases of TKI-related bowel perforation have been reported, and the true incidence rate is still unknown. Lenvatinib-related bowel perforation has been documented in a patient with metastatic thyroid cancer [6].

The most likely etiology of TKI-related bowel perforation involves tumor invasion or ischemia [7]. Drug-induced bowel perforation has also been documented but without inflammatory findings, tumor invasion, ulceration, or diverticula. None of the abnormal findings such as diverticulum and inflammation had been seen in previous colonoscopy in this patient.

Bowel perforation is caused directly by regression of normal blood vessels induced by excessive inhibition of VEGF, which has been shown to decrease the density of blood vessels in the villi of the small intestine. TKIs may cause arterial thromboembolic events, leading to regional bowel ischemia and then to perforation. Furthermore, angiogenesis inhibitors may prevent healing of gastrointestinal ulcers or colonic diverticulitis that could progress to perforation [8].

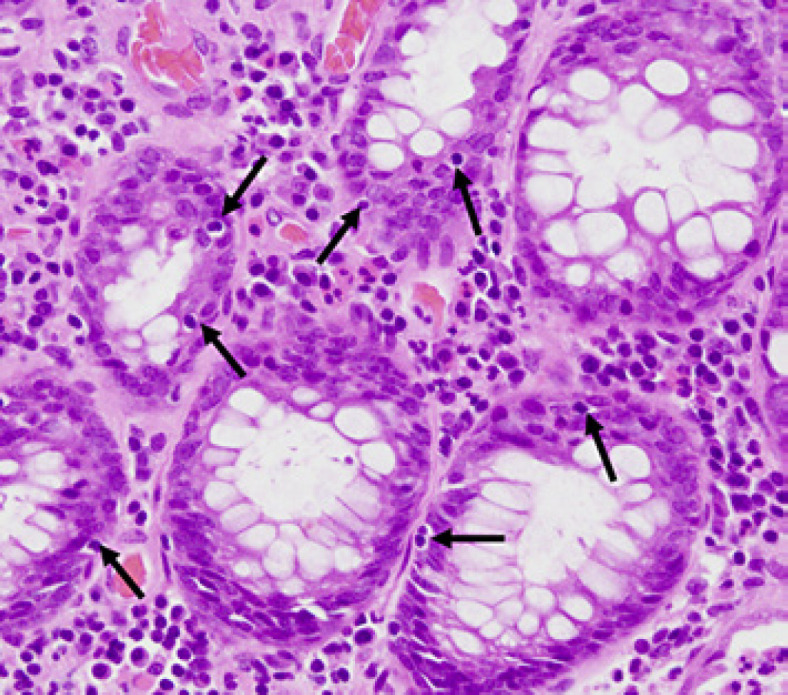

Apoptosis (Fig. 4) is a specific type of cell death that is responsible for the removal of cells from normal tissues and also occurs in specific pathologic contexts [9]. Several reports have shown that apoptosis is a key early marker of chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal injury, and crypt hyperplasia occurs during the regenerative phase following severe injury [10]. The presence of apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells adjacent to the site of ischemia was conspicuous in our patient suggesting that lenvatinib caused bowel perforation. Shaikh et al. [11] described anticancer drug-induced apoptosis may contribute to gastrointestinal perforation and may cause this event regardless of the time and dose from the start of anticancer drug administration, whether in the small or large intestine.

Fig. 4.

Crypts in the colon indicate an increase in the number of apoptotic bodies (arrows). Staining, hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×40.

A meta-analysis found that TKI-induced bowel perforation had a mortality rate of 28.6% (range, 15.0–47.6%) [4]. The risk of gastrointestinal perforation can be decreased by administering an agent with intestinotrophic and antiapoptotic effects, such as glycogen-like peptide (GLP)-2 [12]. This peptide has been shown to increase the weight of the small bowel significantly, leading to lengthening of the intestinal villi and expansion of the crypt compartment [13]. The GLP-2 analog stimulates crypt cell proliferation and has an antiapoptotic mechanism, to maintain the function and integrity of the intestine. Additionally, it was also shown to reduce histopathological damage to the intestine in rat models when treated with TKI [14].

TKI therapy will continue to be an important component of treatment for solid cancers. Although there is no firm evidence that bowel perforation was drug-induced in our patient, it is important to obtain as many details as possible in such cases to improve our understanding of its mechanisms so that this life-threatening complication may be prevented in the future.

In conclusion, we treated bowel perforation in a patient with HCC while being treated with lenvatinib. Lenvatinib is considered an etiological factor in bowel perforation. Clinicians should be vigilant about the life-threatening gastrointestinal complications that may develop in patients being treated with lenvatinib and consider the use of intestinotrophic or antiapoptotic agents to prevent the potentially fatal side effects.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's children for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. This study protocol was reviewed, and the need for approval was waived by the Ethics Committee at the Tokyo Bay Urayasu Ichikawa Medical Center.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Sources

There were no finding sources.

Author Contributions

Ken Mizokami conducted a literature search and drafted this manuscript. Akira Saito edited and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Akiko Watanabe and Eriko Yamaguchi were responsible for this patient's treatment and assisted with the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Please direct further inquiries to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Suyama K, Iwase H. Lenvatinib: a promising molecular targeted agent for multiple cancers. Cancer Control. 2018 Jan–Dec;25((1)):1073274818789361. doi: 10.1177/1073274818789361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doycheva I, Thuluvath PJ. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of a rapidly evolving field. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019 Sep–Oct;9((5)):588–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Personeni N, Pressiani T, Rimassa L. Lenvatinib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence to date. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2019 Jan 31;6:31–9. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S168953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki N, Tajiri K, Futsukaichi Y, Tanaka S, Murayama A, Entani T, et al. Perforation of the small intestine after introduction of lenvatinib in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020 Feb 5;14((1)):63–9. doi: 10.1159/000505774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang ZF, Wang T, Liu LH, Guo HQ. Risks of proteinuria associated with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 12;9((3)):e90135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Date E, Okamoto K, Fumita S, Kaneda H. Gastrointestinal perforation related to lenvatinib, an anti-angiogenic inhibitor that targets multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, in a patient with metastatic thyroid cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2018 Apr;36((2)):350–3. doi: 10.1007/s10637-017-0522-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walraven M, Witteveen PO, Lolkema MPJ, van Hillegersberg R, Voest EE, Verheul HMW. Antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibition related gastrointestinal perforations: a case report and literature review. Angiogenesis. 2011 May;14((2)):135–41. doi: 10.1007/s10456-010-9197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HX, Cleck JN. Adverse effects of anticancer agents that target the VEGF pathway. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug;6((8)):465–77. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr JF, Winterford CM, Harmon BV. Apoptosis. Its significance in cancer and cancer therapy. Cancer. 1994 Apr 15;73((8)):2013–26. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940415)73:8<2013::aid-cncr2820730802>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowen JM. Development of the rat model of lapatinib-induced diarrhoea. Scientifica. 2014;2014:194185. doi: 10.1155/2014/194185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh DH, Baiomi A, Mehershahi S, Abbas H, Gongati S, Nayudu SK. Paclitaxel-induced bowel perforation: a rare cause of acute abdomen. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep–Dec;14((3)):687–94. doi: 10.1159/000510131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker DJ. The discovery of GLP-2 and development of teduglutide for short bowel syndrome. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2019 Mar;2((2)):134–42. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.9b00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen AR, Viby NE, Hare KJ, Hartmann B, Thim L, Holst JJ, et al. The intestinotrophic peptide, GLP-2, counteracts the gastrointestinal atrophy in mice induced by the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, erlotinib, and cisplatin. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Oct;55((10)):2785–96. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayo BJ, Secombe KR, Wignall AD, Bateman E, Thorpe D, Pietra C, et al. The GLP-2 analogue elsiglutide reduces diarrhoea caused by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib in rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2020 Apr;85((4)):793–803. doi: 10.1007/s00280-020-04040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Please direct further inquiries to the corresponding author.