Abstract

The lrpC gene was identified during the Bacillus subtilis genome sequencing project. Previous experiments suggested that LrpC has a role in sporulation and in the regulation of amino acid metabolism and that it shares features with Escherichia coli Lrp, a transcription regulator (C. Beloin, S. Ayora, R. Exley, L. Hirschbein, N. Ogasawara, Y. Kasahara, J. C. Alonso, and F. Le Hégarat, Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:63–71, 1997). To characterize the interactions of LrpC with DNA, the protein was overproduced and purified. We show that LrpC binds to multiple sites in the upstream region of its own gene with a stronger affinity for a region encompassing P1, one of the putative promoters identified (P1 and P2). By analyzing lrpC-lacZ transcriptional fusions, we demonstrated that P1 is the major in vivo promoter and that, unlike many members of the lrp/asnC family, lrpC is not negatively autoregulated but rather slightly positively autoregulated. Production of LrpC in vivo is low in both rich and minimal media (50 to 300 LrpC molecules per cell). In rich medium, the cellular LrpC content is six- to sevenfold lower during the exponentional phase than during the stationary growth phase. Possible determinants and the biological significance of the regulation of lrpC expression are discussed.

LrpC from Bacillus subtilis belongs to the Lrp/AsnC family of proteins named after two regulators identified in Escherichia coli: Lrp (leucine-responsive regulatory protein) and AsnC (3, 6, 17, 27). Lrp from E. coli is a global regulatory protein that controls the expression of about 75 genes (26), whereas AsnC regulates the expression of the asnA gene only, which codes for asparagine synthetase A (17). Sequences of several genomes revealed not only the presence of lrp/asnC-like genes in gram-positive eubacteria and in archaea but also a surprising multiplicity of these genes in the genome of B. subtilis. Seven genes encoding proteins of the Lrp/AsnC family, including lrpC, can be detected in B. subtilis using the BLAST program (1): lrpC (EMBL accession no. Z99106), lrpA (yddO) (EMBL accession no. Z99106), lrpB (yddP) (EMBL accession no. Z99106), yezC (EMBL accession no. Z99107), ywrC (EMBL accession no. Z93767), azlB (EMBL accession no. Y11043), and yugG (EMBL accession no. Z93934). In addition to the lrpC gene, three other lrp genes have already been studied: lrpA (yddO), lrpB (yddP) (10), and azlB (2). lrpA and lrpB are implicated in KinB-dependent sporulation, probably through regulation of glyA transcription by their corresponding proteins (10). azlB, initially described as a locus conferring resistance to 4-azaleucine (44), was found to be a negative regulator of the azlBCDEF operon involved in branched-chain amino acid transport (2).

LrpC is a 16.4-kDa protein that cross-reacts with antibodies against E. coli Lrp (3). It shares 34 and 25% identity with the E. coli Lrp and AsnC proteins, respectively. An lrpC mutant does not display a radically altered phenotype, suggesting that LrpC can be replaced with the other Lrp/AsnC-like proteins of B. subtilis or that it does not have a detectable role under laboratory conditions. Furthermore, growth of the lrpC mutant was not affected. We reported a possible role for LrpC in entry into sporulation, either by controlling factors that trigger the onset of sporulation or by regulating early sporulation genes (3). The LrpC N-terminal region includes a typical DNA-binding helix-turn-helix motif. Results of heterologous complementation experiments show that the E. coli ilvIH operon is repressed by LrpC (3). Taken together, these data suggest that LrpC is a transcriptional regulator. This idea was tested by studying the binding of purified LrpC to the promoter of its own gene and by investigating the regulation of lrpC in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

An overexpression system (36) based on T7 RNA polymerase comprised plasmid pET3blrpC and E. coli strain BL21 (λDE3)pLysS [F− hsdS gal (λcIts857 indI Sam7 nin-5 lacUV5-T7 gene 1) rB− mB− pLysS]. Strain 168 (trpC2 BGSC 1A1) was routinely used in this work. The construction of lrpC mutant strain FC1 (trpC2 lrpC::cat) has been previously described (3).

Plasmids pUC18 (49), pLysS, pET3b (36), pHP13 (14), and pMUTIN4m (39) have been previously described. The construction of pT712lrpC, used in sequencing reactions, has been previously described (3). pHP13lrpC consists of a 1,184-bp fragment from the B. subtilis 168 chromosome, containing the whole lrpC gene with its transcription-translation signals, cloned between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pHP13.

For the construction of plasmid pET3blrpC, the lrpC gene was amplified by PCR using B. subtilis strain 168 chromosomal DNA as the template and oligonucleotides 1 and 2 (Table 1). These primers were engineered to contain NdeI and BamHI restriction sites near the 5′ end and also one translation initiation and one termination codon. The PCR product, 440 bp in length and containing the lrpC gene, was cleaved by NdeI and BamHI and then ligated to the NdeI-BamHI-cleaved pET3b vector, giving the pET3blrpC plasmid. The lrpC gene was then under the control of the φ10 promoter of the T7 bacteriophage. The construction was verified by sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this worka

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-GGATGTTCATATGAAACTTGACCAGATT-3′ (NdeI) |

| 2 | 5′-GCGGGGATCCCTAACCGCGCCCGTTTTTCGT-3′ (BamHI) |

| 3 | 5′-GCGGGATCCCTGCCCAATATTTAAGCG-3′ (BamHI) |

| 4 | 5′-CTCGGATCCATTCAGATCAATCTGGTC-3′ (BamHI) |

| 5 | 5′-GCGTGGATCCCAATCCGGGGGGGCATATG-3′ (BamHI) |

| 6 | 5′-GTTTTTTCTGGTCGACCTC-3′ |

| 7 | 5′-GATCGGCGTGTGCAGCAT-3′ |

| 8 | 5′-CAAGCTGTCTTACCCGTT-3′ |

| 9 | 5′-GGATTAAGAGTGACATTCC-3′ |

| 10 | 5′-CTGCCTAATTCCCTCATC-3′ |

| 11 | 5′-AGCGGCCATTTGACAGAG-3′ |

| 12 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCTACAGTTCCCTAGAAAAG-3′ (BamHI) |

| 13 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCATCGTGCGAAGTCTTCGG-3′ (BamHI) |

| 14 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCTTTGATTTTGTACACATT-3′ (BamHI) |

| 15 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCCCGAACATTTTTTGAAAG-3′ (BamHI) |

| 16 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCATGCCCCCCCGGATTGTT-3′ (BamHI) |

| 17 | 5′-GGCCGGATCCTTGTCATTTACAAAAATACCC-3′ (BamHI) |

| 18 | 5′-GGCCGAATTCCTGCCCAATATTTAAGCG-3′ (EcoRI) |

| 19 | 5′-GCGTGAATTCCAATCCGGGGGGGCATATG-3′ (EcoRI) |

| 20 | 5′-GCGATTAAGTTGGGTA-3′ |

| 21 | 5′-CCAAGCTTATCGCGTGGCTGACAAAG-3′ |

| 22 | 5′-TCTTCCCGATGATTAAGCTTG-3′ |

| 23 | 5′-TTCTGCCTAATTCCCTCATC-3′ |

Some of these oligonucleotides were engineered to contain NdeI, BamHI, and EcoRI restriction sites (underlined) at the 5′ end. In primers 1 and 2, used to clone the lrpC gene in overexpressing vector pET3b (36), translation initiation and termination codons are in bold.

For the construction of plasmid pUC18prolrpC, the lrpC promoter region was amplified by PCR using B. subtilis strain 168 chromosomal DNA as the template. Primers 3 and 4 (Table 1) were engineered to contain BamHI restriction sites near the 5′ end. The PCR product, 331 bp in length, was cleaved by BamHI and ligated to the BamHI-cleaved pUC18 vector, giving the pUC18prolrpC plasmid. The integrity of the cloned region was confirmed by sequencing.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was used for routine growth and maintenance of E. coli cells. LB and glucose minimal Spizizen (34) media were used to grow B. subtilis cells in LrpC immunodetection and β-galactosidase experiments. The antibiotics used were ampicillin at 50 or 200 μg/ml (for overexpression experiments), chloramphenicol (CM) at 50 μg/ml, and erythromycin (ERM) at 5 μg/ml.

Overexpression and purification of the LrpC protein.

Strain BL21 (λDE3)pLysS(pET3blrpC) was grown in LB medium containing ampicillin at 200 μg/ml and CM at 50 μg/ml to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. Overexpression was then induced by 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 h. Crude extracts prepared from cultures induced for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–16% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), allowing the verification of LrpC overproduction.

The purification protocol was finalized by S. Ayora and performed with modifications as follows. The 16-kDa LrpC protein (predicted molecular mass, 16,449.86 Da) was purified by monitoring LrpC and E. coli Lrp using immunodetection with antibodies raised against E. coli Lrp. The pellet of a 2-liter culture of strain BL21 (λDE3)pLysS(pET3blrpC) induced by IPTG for 3 h and collected by low-speed centrifugation was resuspended in 50 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol). All further procedures were carried out at 4°C. The cells were broken in a French press at 25,000 lb/in2. The total extract was clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm (Sorvall SS34 rotor) for 20 min. Supernatant I was kept. The crude pellet was sonicated three times for 1 min each time in a Braun Labsonic U/B apparatus and centrifuged again at 12,000 rpm for 30 min. Supernatant II was kept. Supernatants I and II were pooled, and polyethylenimine (10%, pH 7.5) was slowly added with constant stirring to a final concentration of 0.25%. The solution was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm, and the pellet was washed several times with buffer A and discarded. The B. subtilis LrpC protein, which remains in the supernatant, was precipitated by addition of solid ammonium sulfate to a final saturation of 60%. The pellet was resuspended in 70% ammonium sulfate solution and pelleted again.

The protein pellet was resuspended in buffer A, dialyzed against buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl, and loaded onto a 30-ml phosphocellulose column equilibrated with buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl. The column was extensively washed with buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl. The LrpC protein was eluted from the column by using four steps of 200 mM, 300 mM, 450 mM, and 1 M NaCl in buffer A. E. coli Lrp protein was eluted at 300 mM NaCl, whereas B. subtilis LrpC was eluted at 450 mM NaCl. Fractions of the 450 mM NaCl eluate were pooled and concentrated against Sephadex G200. They were then loaded on a Sephacryl S100-HR column. The elution fractions corresponding to proteins with molecular masses of 10 to 70 kDa were monitored by SDS-PAGE, and those containing pure LrpC were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A containing 300 mM NaCl. After the last purification step, the B. subtilis LrpC protein was more than 98% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE and free of E. coli Lrp as judged by Western blotting with anti-Lrp antibodies (data not shown). Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 20%, and samples were stored at −80°C.

The LrpC protein concentration was determined by using a molar extinction coefficient of 7,860 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm.

The isoelectric point (pI) of LrpC (predicted pI, 7.89) was determined using the PHAST system with isoelectric focusing (IEF) gels 3 to 9 from Pharmacia under nondenaturing conditions. Pure LrpC (2 μg) was applied to the middle of the gel, and migration was performed in accordance with the Pharmacia PHAST IEF protocol. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue dye, and the pI of LrpC was estimated in accordance with IEF standards 3 to 9.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against LrpC were conventionally prepared using purified LrpC. Prior to immunodetection, the serum was absorbed against a crude protein extract of strain FC1 (lrpC−).

Curvature of the lrpC promoter region. (i) Two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis.

A 200-ng sample of the 331-bp fragment (amplified with primers 3 and 4, corresponding to fragment d in the curvature assay; Table 1) containing the lrpC promoter region was mixed with the Gibco BRL 123-bp DNA ladder. First- and second-dimension electrophoresis was carried out at 4°C with 89 mM Tris borate–2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) (TBE 1×) in 2% agarose at 10 V/cm and 8% acrylamide–N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (80:1 final ratio) at 2 V/cm, respectively. DNA was stained by incubating the gel in TBE 1× containing ethidium bromide at 0.2 μg/ml.

(ii) Software analysis.

Curvature of the promoter region was verified using the DNA ReSCue program (21). This program is based on the different analysis methods of Koo and Crothers (18), Bolshoy et al. (4), and de Santis et al. (11).

(iii) Assay for localization of maximum curvature of the 5′ lrpC region.

Five different 331-bp fragments, containing the predicted curved region of the lrpC promoter region at different locations relative to the ends of the fragment (see Fig. 3A), were amplified by PCR using strain 168 chromosomal DNA as the template, proofreading Vent DNA polymerase, and the following combinations of oligonucleotides (Table 1): fragment a, 5 and 6; fragment b, 7 and 8; fragment c, 9 and 10; fragment d, (this fragment corresponds to the region cloned in pUC18 and used in 2D analysis and also in retardation experiments), 3 and 4; fragment e, 11 and 12. A 100-ng sample of each fragment was then subjected to electrophoresis with a 6% acrylamide–N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (80:1 final ratio) gel in 40 mM Tris acetate–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) at 10 V/cm and 4°C (see Fig. 3B). For each fragment, the distance migrated, in centimeters, was plotted against the position of the estimated maximum curvature relative to the center of the fragment (y − x) (see Fig. 3C).

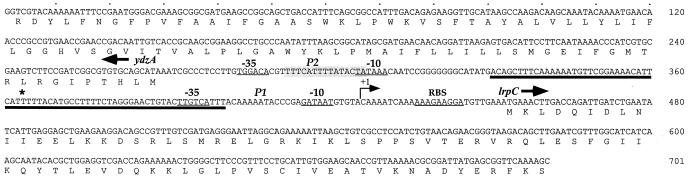

FIG. 3.

Localization of the maximum curvature of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region. (A) Five different ∼331-bp fragments (a to e) of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region were PCR amplified. The positions of the start and end points of the fragments with respect to the sequence given in Fig. 1 are as follows: a, 302 to 633; b, 251 to 582; c, 202 to 531; d, 157 to 488; e, 63 to 392. The maximum curvature predicted by in silico analysis (thick arrow) was displaced along the ∼331-bp fragments. x and y represent the distances, in base pairs, of this putative curvature maximum from the 5′ and 3′ extremities of the fragment, respectively. P1, P2, and ATG of lrpC are indicated. (B) The five ∼331-bp fragments were run on a 6% polyacrylamide gel at 4°C. Lanes M represent linear 100-bp DNA ladders (Promega). (C) For each fragment, the distance migrated (centimeters) was plotted against the position of the predicted curvature maximum relative to the center of the fragment (y − x). Zero on the abscissa corresponds to the position of curvature maximum predicted by computer analysis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

The different promoter segments were amplified by PCR using the following combinations of oligonucleotides (Table 1): 331-bp fragment, 3 and 4 (fragment d of the curvature assay); 265-bp fragment, 13 and 4; 213-bp fragment, 13 and 14; 169-bp fragment, 13 and 12; 128-bp fragment, 13 and 15; 103-bp fragment, 13 and 16; 90-bp fragment, 5 and 12; 105-bp fragment, 17 and 4; 168-bp fragment, 5 and 4; 130-bp fragment, 19 and 14.

A typical assay mixture contained 25 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 or 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mM PMSF, 4 mM spermidine, 0.5 nM 32P-end-labeled DNA probe, and various amounts of purified LrpC protein in a volume of 20 μl. Where indicated, 0.15 μM competitor DNA (250-fold excess in mass) that corresponds to a synthetic 266-bp fragment, S15-12, containing tandem repeats of a 15-mer (×10) and flanked by residual pTZ18R polylinker sequences at both of its ends (47) was added. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the reaction mixture was loaded immediately onto a 6% acrylamide–N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (80:1 final ratio) gel containing 10% glycerol in 44.5 mM Tris borate–2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) (31). Electrophoresis was performed at 10 V/cm and 4°C. Gels were dried, visualized by autoradiography, and quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Isolation of RNA.

Total RNA was prepared from B. subtilis strains 168pHP13 and 168pHP13lrpC, which carries lrpC on a five-copy-number plasmid (3). This strain was used in order to obtain sufficient levels of lrpC mRNA. Cells were harvested at an OD600 of 1.0 by centrifugation at 4°C. Total RNA was prepared using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit. The concentration and purity of RNA were determined by measuring the OD260 and the OD260/OD280 nm ratio, respectively, and by analysis on formaldehyde-agarose gels. Forty micrograms of RNA was precipitated with 3 volumes of ethanol and 1/10 volume of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) and resuspended in a final volume of 5 μl of water.

Primer extension.

Forty micrograms of total cell RNA was mixed with 1 pmol of 5′-end 32P-labeled oligonucleotide primer (no. 23 in Table 1; positions 515 to 533 in Fig. 1) in 10 μl of avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT). The hybridization conditions were 1 min at 90°C, 10 min at 55°C, and then 15 min on ice. After hybridization, 10 μl of reaction buffer containing 2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 8 mM DTT, 0.2 volume of 5× AMV RT buffer, RNasin (Promega) at 1 U/μl, and 10 U of AMV RT was added and primer extension was carried out at 42°C for 1 h. After extension, products were precipitated with 3 volumes of ethanol and 1 M lithium chloride for 30 min at −80°C, washed with 70% ethanol, and dried. Pellets were resuspended in 12 μl of formamide loading buffer–Tris-EDTA (1:1) and analyzed on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel (Sequagel-6, Prolabo). The same 5′-end 32P-labeled oligonucleotide was used for a sequence reaction using the Promega fmol DNA sequencing kit and plasmid pT712lrpC as the template.

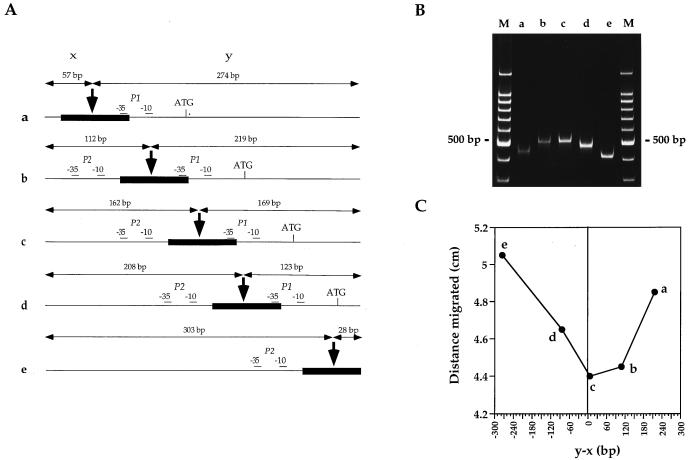

FIG. 1.

Relevant nucleotide sequence of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region. The nucleotide sequence of a 700-bp fragment containing the whole lrpC 5′ noncoding region is presented. Putative transcriptional and translational signals are underlined. The 15-bp sequence containing 12 bp matching the E. coli Lrp consensus binding site is shaded. The transcription start site of P1 (+1), determined by primer extension (see Fig. 7), is represented by a black arrow. The intrinsically bent segment localized between promoters P1 and P2 is thickly underlined. The center of the curvature is indicated by the asterisk. The gene ydzA, whose function is unknown, and which is located 185 bp upstream of lrpC, is also indicated, as well as the first 90 amino acids it encodes. It is transcribed in the opposite direction with respect to lrpC.

Detection of LrpC in vivo.

B. subtilis strain 168 was grown in LB or supplemented Spizizen glucose minimal medium (containing 0.5% glucose, 0.04% MgSO4-7H2O, and 50 μg of tryptophan per ml). At different growth times, the bacterial concentration was determined (bacteria were counted on plates of appropriate dilutions) and samples corresponding to 109 bacteria were harvested. Pellets were washed in buffer M (50 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT) and resuspended in 200 μl of the same buffer. Lysis was carried out by adding lysozyme at 0.1 mg/ml and incubating the mixture for 10 min at 37°C. A freezing-defreezing procedure was used to obtain complete cell lysis. DNA was degraded by DNase I at 1 μg/ml in 10 mM MgCl2 for 10 min at 37°C. Samples were then boiled for 5 min and conserved at −20°C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (31).

A 12-μg sample of each protein extract was fractionated by 0.1% SDS–16% PAGE (18), blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubate with antibodies raised against the LrpC protein. Antibody binding was visualized using the alkaline phosphatase system. LrpC protein standards (0.1 to 1 ng of pure protein) were mixed with 12 μg of crude extracts of lrpC mutant strain FC1 in order to mimic the strain 168 crude-extract situation and loaded next to protein samples of strain 168 from LB or glucose minimal medium, and immunodetection was performed. The established standard curve was then compared by scanning analysis with LrpC protein detected in crude extracts from cells grown in LB and glucose minimal medium.

Construction and analysis of lrpC-lacZ fusion.

Plasmid pMUTIN4m (Ermr) (39) contained an IPTG-inducible promoter, Pspac, followed by a polylinker sequence for cloning and the lacZ gene preceded by the strong ribosome-binding site of the spoVG gene. The region containing the Pspac promoter was deleted from pMUTIN4m, giving plasmid pFus. Three fragments corresponding to different regions of the lrpC promoter were amplified by PCR using strain 168 chromosomal DNA as the template, proofreading Vent DNA polymerase, and the following oligonucleotides (Table 1): fragment 1 (289 bp), 18 and 14; fragment 2 (244 bp), 18 and 12; fragment 3 (205 bp), 18 and 15. Primers were engineered to contain EcoRI or BamHI restriction sites near the 5′ end. The three PCR products were digested by EcoRI and BamHI and cloned upstream of the lacZ gene in the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the pFus plasmid, resulting in plasmids pFus1 to pFus3 (see Fig. 6A). Cloned fragments were sequenced to verify their integrity. These three plasmids were then used independently to transform B. subtilis 168 and FC1 competent cells via a single crossover (12). Ermr transformants carrying lacZ transcriptionally fused to lrpC were selected for further analysis and named LF1 to LF3 (168 was the recipient strain) or LF1′ to LF3′ (FC1 was the recipient strain). Integrations were verified by PCR analysis of the junctions of the integration (5′ junction, primers 20 and 21; 3′ junction, primers 22 and 4) (Table 1; see Fig. 6A) and Southern blot analysis performed on EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA using the lacZ gene as the probe. The absence of LrpC protein in LF1′, LF2′, and LF3′ was checked by immunodetection for each recombinant strain (data not shown).

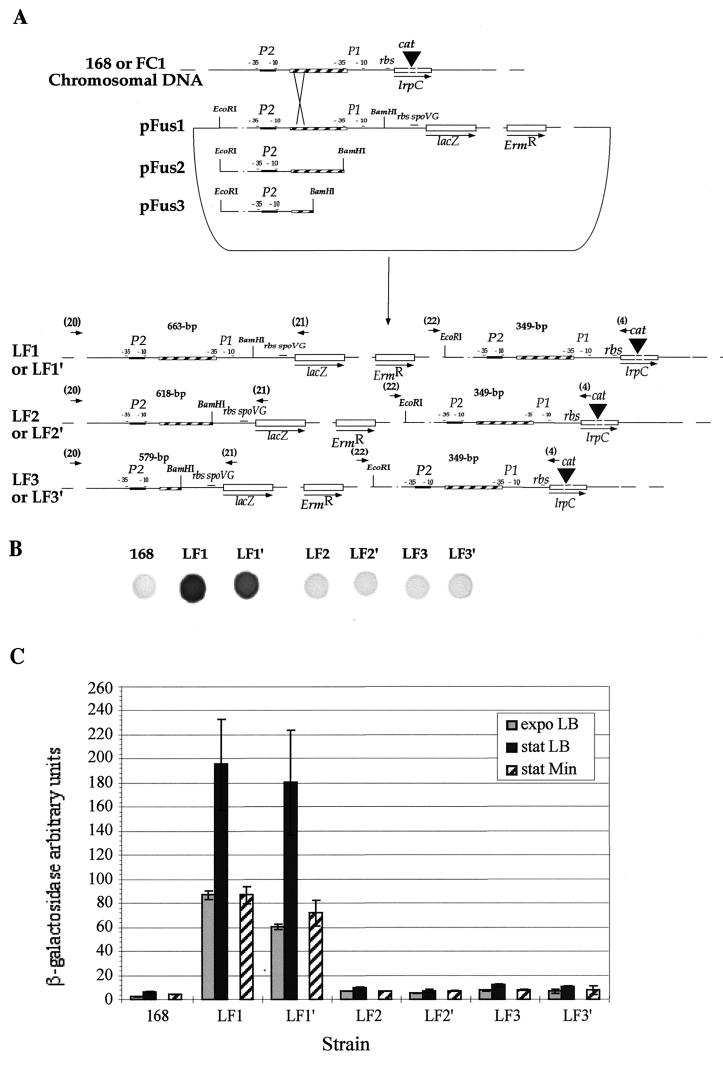

FIG. 6.

Construction and activities of various lrpC-lacZ fusions. (A) Three fragments encompassing different parts of the 5′ lrpC region were cloned upstream of the lacZ gene in plasmid pFus (this work) and sequenced to verify their integrity. The 15-bp sequence matching the E. coli Lrp consensus binding site is in the black box, whereas the curved DNA region is in the hatched box. Integrations were then performed by single crossover in the lrpC locus in a wild-type (168 leading to LF1 to LF3) or mutant (FC1 leading to LF1′ to LF3′) lrpC genetic context. Plasmid DNA is included between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. Ermr recombinant strains were used for further analysis. The lacZ gene is controlled by the P1-P2 region in LF1 and LF1′ and by the P2 region in LF2 and LF2′ (with the whole curved DNA region) and in LF3 and LF3′ (with the first third of the curved DNA region). In LF1, LF2, and LF3, the wild-type lrpC gene is under the control of the entire P1-P2 region. Oligonucleotides used for junction verification and predicted sizes of the corresponding PCR fragments are indicated. rbs, ribosome-binding site. (B) β-Galactosidase activity of the lrpC-lacZ fusions on solid medium. Approximately 2 · 106 bacteria of each transformant type were placed on a petri dish of glucose minimal Spizizen medium (see Materials and Methods) with ERM at 5 μg/ml and X-Gal at 100 μg/ml. Incubation was performed for 16 h at 37°C and prolonged at room temperature (25°C) until sufficient blue coloration appeared. (C) β-Galactosidase activity of the lrpC-lacZ fusions in liquid medium. The different strains were grown in glucose minimal Spizizen and LB media, and the expression of lrpC was monitored using the sensitive liquid Galacto-Light Assay protocol (Tropix). Relative luminescence units were then converted to β-galactosidase units using a standard curve. Arbitrary β-galactosidase units correspond to (β-galactosidase units per minute per milliliter per unit of OD600) × 10−6.

β-Galactosidase assays on solid medium were performed as follows. A drop of each LB culture containing approximately 2 × 106 cells was placed on a petri dish of Spizizen glucose minimal medium (containing 0.5% glucose, 0.04% MgSO4-7H2O, and 50 μg of tryptophan per ml) with added ERM at 5 μg/ml and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) at 100 μg/ml. Petri dishes were incubated for 16 h at 37°C and placed at room temperature until sufficient blue color appeared. Several transformants of each type were checked for coloration. In addition, each transformant was plated at least three times to confirm coloration.

β-Galactosidase assays in liquid medium were performed as follows. Strains 168 and LF1 to LF3 were grown at 37°C in Spizizen glucose minimal medium (containing 0.5% glucose, 0.04% MgSO4-7H2O, and 50 μg of tryptophan per ml) and LB with added ERM at 5 μg/ml when necessary. Strains LF1′ to LF3′ were grown in the same medium with an additional 5 μg of CM per ml. Eight milliliters of each culture in the exponential (OD600, ∼0.5) and stationary phases (OD600, ∼2) was pelleted, resuspended in 200 μl of lysis solution (100 mM KHPO4, 20% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, benzamidine at 315 μg/ml, pepstatin A at 1.4 μg/ml, leupeptin at 0.26 μg/ml, and antipain, chymostatin, and PMSF each at 2 μg/ml) and then mechanically broken using glass beads. Lysates were then centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g and 4°C. Ten- and 20-μl samples of each supernatant were tested in duplicate using the Galacto-Light Assay protocol (obtained from Tropix) and measured in a luminometer. Relative luminescence units were then expressed per minute, volume of culture (milliliters), and OD unit and converted to β-galactosidase units using a standard curve. Arbitrary units therefore correspond to (β-galactosidase units/minute/milliliter/OD600 unit) × 10−6. For average values of two independent experiments, see Fig. 6C.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequence of the 5′ noncoding region of lrpC has been assigned EMBL database accession no. Z99106.

RESULTS

Purification and properties of LrpC.

The LrpC protein was overproduced using the T7 RNA polymerase expression system (36). Briefly, plasmid pET3blrpC, which carries the lrpC gene downstream of a T7 promoter, was introduced into E. coli strain BL21 (λDE3)pLysS and the lrpC gene was overexpressed following addition of IPTG. The overproduced 16.4-kDa polypeptide was purified by conventional column chromatography (see Materials and Methods). The LrpC polypeptide was free of the 21-kDa E. coli Lrp protein, as revealed by immunoblotting with antibodies to E. coli Lrp, and was more than 98% pure (data not shown). The LrpC polypeptide has a calculated pI of 7.89 (Program Compute pI/MW at http://www.expasy.ch/ch2d/pi_tool.html). The experimentally determined pI of LrpC protein was 7.6 (see Materials and Methods).

LrpC comprises 144 amino acids, corresponding to a molecular mass of 16.4 kDa (deduced from the nucleotide sequence). The molecular mass of the native LrpC protein, estimated by gel filtration, corresponds to a tetrameric form of the protein in solution (37).

The lrpC promoter region is intrinsically curved.

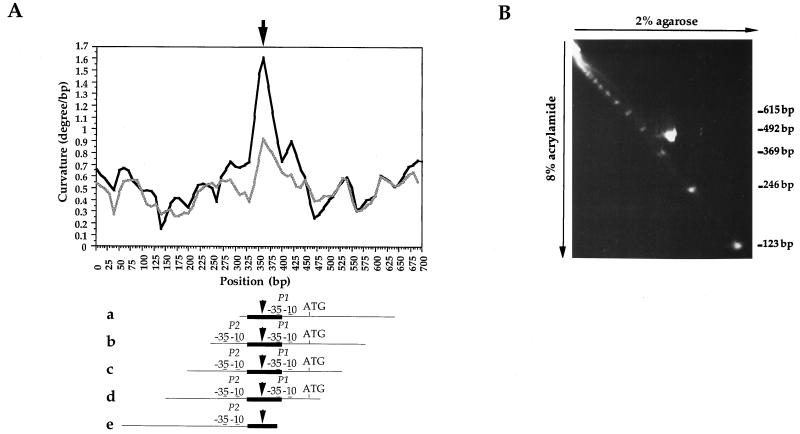

Prior to analysis of the DNA-binding properties of the pure LrpC protein, the upstream region of the lrpC gene was examined for possible regulatory elements. Several interesting features were observed, and their importance for LrpC binding was assessed. lrpC gene promoter curvature was assessed using the DNA ReSCue program (see Materials and Methods). Analyses revealed sharply increased curvature around position 363 between the two putative lrpC promoters (Fig. 1 and 2A).

FIG. 2.

Detection of lrpC 5′ noncoding region curvature. (A) Computer analysis of the curvature of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region. The 700-bp sequence presented in Fig. 1 was subjected to the DNA ReSCue program (21). Two curves, determined as described by Koo and Crothers (18) (black) and Bolshoy et al. (4) (grey), are presented. Curvature (degrees per base pair) is plotted against position in the sequence. Maximum curvature is indicated by the arrow. The permuted fragments used in the curvature assay (see Fig. 3) are aligned under the 700-bp sequence curvature graph. (B) 2D electrophoresis of a 331-bp fragment (amplified with primers 3 and 4 and corresponding to fragment d in the curvature assay) containing the lrpC promoter region. The 331-bp fragment and the 123-bp linear DNA ladder (Gibco BRL) were separated in the first dimension in a 2% agarose gel and in the second dimension in an 8% polyacrylamide gel at 4°C. DNA was stained by incubating the gel with ethidium bromide at 0.2 μg/ml.

Curved DNA sequences are common in promoters of prokaryotic genes (41). The relationship between intrinsic DNA curvature and transcriptional activity in vivo has been suggested in a number of cases (15, 24, 35, 48).

The presence of a curved region in the lrpC 5′ noncoding sequence was verified experimentally by analyzing the 331-bp PCR-amplified lrpC promoter region (positions 157 to 488) by 2D electrophoresis at 4°C (Fig. 2B). The fragment migrated above the diagonal line formed by the noncurved DNA ladder, as expected for curved DNA (25).

Next we designed an assay to determine regions of the promoter with large curve-inducing propensities. According to Wu and Crothers (46), aberrant migration of curved DNA is more marked the closer the bend is to the middle of the molecule. Five different fragments of 331 bp in which the putative maximum curvature region (Fig. 3A) was positioned in a distal (a and e), intermediate (b and d), or central (c) position of the molecule were run on a polyacrylamide gel at 4°C and showed different mobilities (Fig. 3B). A graph representing the distance migrated as a function of the position of the maximum curvature in relation to the center of the molecule (y − x) revealed that fragment c is the most retarded fragment, followed by fragments b, d, a, and e (Fig. 3C). This result is in good agreement with the localization of the maximum curvature predicted by in silico analysis. However, fragments a and e, where the maximum curvature is localized near the end of the DNA, were also slightly retarded. This could be explained by the presence of an additional minor curved region(s) that contributes to the three-dimensional trajectory of the fragments. Furthermore, considering the estimated position of maximum curvature (Fig. 3A), fragment b should be less retarded than fragment d. An additional minor curved region, as for fragments a and e, or alternatively a special conformation of fragment b undetected by DNA ReSCue analysis could explain this greater retardation.

DNA-binding characteristics of LrpC.

Computer analysis of the 5′ noncoding region of the lrpC gene revealed two putative promoters (P1 and P2). In addition, a 15-bp sequence (TTTCATTTTATACTA, coordinates 293 to 307 in Fig. 1) matching the DNA-binding consensus sequence for the E. coli Lrp protein (12 of 15 positions) overlaps putative promoter P2 (3, 9).

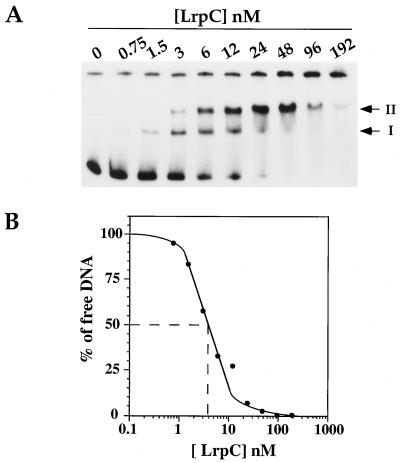

A 331-bp DNA fragment (0.5 nM) corresponding to the 5′ noncoding region containing P1, the curved region, and P2 was therefore 32P end labeled and incubated with increasing concentrations of purified LrpC protein. The formation of protein-DNA complexes was analyzed by nondenaturing PAGE. As shown in Fig. 4A, LrpC binds its own promoter region in several steps. At low LrpC concentrations (0.75 to 1.5 nM LrpC in tetramers), a type I complex was formed, whereas with increasing protein concentrations (3 to 12 nM), a second, more slowly migrating complex (type II) accumulated. Both complexes were very distinct and could correspond to one or two tetramers of LrpC bound to DNA at one or multiple binding sites. At high LrpC concentrations (24 to 96 nM), complex II was the major LrpC-DNA complex observed, whereas at even greater concentrations (192 nM), a higher-order complex that did not migrate into the gel was observed.

FIG. 4.

Binding of LrpC to its own promoter region. (A) The 5′ lrpC region (0.5 nM, 331 bp) corresponding to fragment d (Fig. 3A) was 32P end labeled and mixed with increasing LrpC concentrations ranging from 0 to 192 nM (calculated on the basis of the tetramer form of the protein) in a 20-μl final volume. Complexes were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried, bands were visualized by autoradiography, and each band was quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The positions of complexes I and II are indicated. (B) Binding isotherm of free DNA (percent) at various LrpC concentrations. The Kapp value was estimated as the LrpC concentration required for 50% saturation of the 331-bp DNA promoter region.

The bands corresponding to free DNA were quantitated using a PhosphorImager, and a binding isotherm was then calculated from the decrease in the level of free DNA. The apparent binding constant (Kapp) value representing the LrpC concentration required for 50% saturation of the promoter region (Fig. 4B) is ca. 4 nM at pH 8.0 and room temperature. The same results were obtained when the experiments were performed in the presence of a 250-fold excess of nonspecific competitor DNA. The shape of the curve of LrpC protein binding to the 5′ noncoding region indicates cooperative binding of LrpC to DNA; this was confirmed by the calculation of a Hill coefficient of 1.5 (data not shown).

In certain cases, leucine can modify the binding of E. coli Lrp to the promoter of a gene it regulates (for example, ilvIH [30] and gltBDF [13]). However, binding of LrpC to the 5′ noncoding region of lrpC was not modified by addition of up to 16 mM leucine (data not shown). This result suggests that, in vivo, leucine probably does not affect LrpC binding to its own promoter.

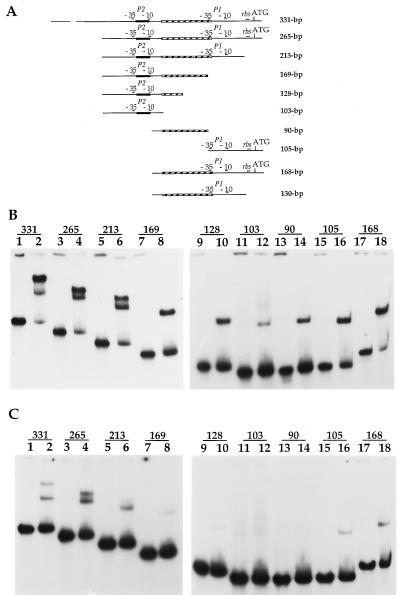

In order to investigate the binding of LrpC to different parts of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region, several DNA fragments were probed for the ability to bind the pure protein. Ten different DNA fragments (Fig. 5A) were individually incubated with 12 nM LrpC (tetrameric) in binding buffer containing either 50 mM (Fig. 5B) or 150 mM (Fig. 5C) NaCl to discriminate between high- and low-affinity LrpC binding.

FIG. 5.

Binding of LrpC to different segments of the lrpC 5′ noncoding region. (A) Ten fragments containing different parts of the 5′ lrpC promoter region were generated by PCR (see Materials and Methods). Each fragment was identified by its size in base pairs. Each 32P-end-labeled fragment (0.5 nM) was mixed with LrpC (12 nM) in a 20-μl final volume and in the presence of a 250-fold excess in mass of synthetic competitor S15-12 DNA (0.15 μM). Complexes were formed under two saline conditions, in 50 mM NaCl (B) and in 150 mM NaCl (C), to discriminate between high- and low-affinity LrpC binding. Complexes were resolved in a 6% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried, and bands were visualized by autoradiography and quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Percentages of bound DNA in 50 and 150 mM NaCl, respectively, were as follows: 331-bp fragment, 84.6 and 23.7%; 265-bp fragment, 77.5 and 46%; 213-bp fragment, 70.4 and 18.3%; 169-bp fragment, 47 and 6.8%; 128-bp fragment, 36.4 and 4.9%; 103-bp fragment, 14 and 4.9%; 90-bp fragment, 19.8 and 3.5%; 105-bp fragment, 50.5 and 11.7%; 168-bp fragment, 76.7 and 18.4%.

LrpC bound with similar affinity to DNA segments of 331 and 265 bp encompassing P1, P2, and the beginning of the lrpC gene. When the 265-bp segment was subdivided into three fragments, 103 bp containing only the P2 region, 90 bp containing the curved segment, and 105 bp encompassing the P1 region, a different outcome was observed. At 50 mM NaCl, the percentages of DNA bound by LrpC were, respectively, 14, ∼20, and ∼50% for these three fragments (Fig. 5B, lanes 11 and 12, 13 and 14, and 15 and 16), whereas at 150 mM NaCl, these percentages decreased, respectively, to ∼5, 3.5, and ∼12% (Fig. 5C, lanes 11 and 12, 13 and 14, and 15 and 16). This indicated that LrpC bound to all three regions but showed different affinities for them. The highest affinity was for the P1 region.

In addition, the affinity of LrpC for a 168-bp fragment with P1 and the curved segment is higher than that for a 169-bp fragment containing P2 and the curved segment (P1 plus curved segment, ∼77% of bound DNA at 50 mM NaCl [Fig. 5B, lanes 17 and 18] and ∼18% at 150 mM [Fig. 5C, lanes 17 and 18]; P2 plus curved segment, ∼47% at 50 mM [Fig. 5B, lanes 7 and 8] and ∼7% at 150 mM [Fig. 5C, lanes 7 and 8]).

Experiments realized with increasing concentrations of LrpC incubated independently with the 103-bp (P2), 90-bp (curved segment), or 105-bp (P1) fragment and the 168-bp (P1 plus curved segment) or 169-bp (P2 plus curved segment) fragment confirmed our conclusion that in vitro, LrpC binds to multiple sites in the 5′ noncoding region of its own gene with preferential affinity for the P1 region (data not shown).

The DNase I cleavage pattern from LrpC-DNA complexes, obtained in either the presence or the absence of a 250-fold weight excess of nonspecific competitor DNA, did not reveal any specific protected site (37). Phosphodiester bonds hypersensitive to DNase I cleavage, however, were observed in phase with the helical pitch but were not modified by addition of up to 20 mM leucine (37), confirming that leucine has no influence on the lrpC promoter-binding activity of LrpC (Fig. 4 and data not shown). These hypersensitive sites are localized close to the putative P1 promoter, therefore supporting the hypothesis that LrpC has the highest affinity for the P1 region (Fig. 5). However, it is likely that the binding of LrpC to DNA is highly dynamic and that upon binding to its 5′ promoter region, LrpC bends the DNA. The helical grooves located on the inner surface of the bend are sterically occluded, while grooves on the outer face are sites of enhanced DNase I cleavage.

Regulation of lrpC expression.

The fact that LrpC binds to its own promoter region suggests that LrpC regulates its own expression, as described for E. coli Lrp (22, 43) and B. subtilis AzlB (2). To test this hypothesis, we examined the in vivo expression of lrpC. Different DNA segments containing either one or both of the putative promoters, P1 and P2, were fused to a promoterless lacZ reporter gene carried by plasmid pMUTIN4m and integrated at the B. subtilis lrpC locus, creating lacZ transcriptional fusions to lrpC. These constructions allowed us to follow the expression of the lrpC gene at its normal locus and to avoid any influence of chromosome position on gene expression. The constructions also maintained an intact promoter region controlling the lrpC gene. They were introduced into both lrpC+ (168 and LF1 to LF3) and lrpC mutant (FC1 and LF1′ to LF3′) strains in order to monitor the effect of LrpC on its own expression (Fig. 6A).

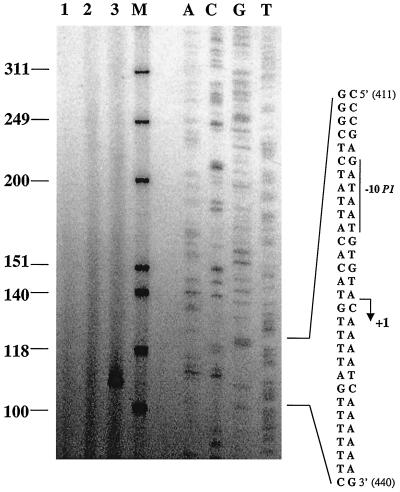

Expression of the two putative lrpC promoters was monitored using both solid (Fig. 6B) and sensitive liquid (Fig. 6C) β-galactosidase assays (see Materials and Methods). Comparison of reporter gene expression under the control of P2-P1 (LF1) and P2 alone (LF2 and LF3) clearly showed that P1 is the major promoter of the lrpC gene in vivo in both rich and minimal media (Fig. 6B and C). P1 is indeed expressed 10 to 20 times more than P2 (Fig. 6C). The P2 promoter was found to be poorly expressed, as revealed by the β-galactosidase activity observed in strains LF2 and LF3, which was only slightly higher than the background activity (Fig. 6C, strain 168). The predominance of P1 expression was confirmed by primer extension in which the transcription start site of P1 was detected whereas that of P2 was not, even when lrpC was borne on a plasmid present at five copies per cell (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Analysis of lrpC promoters by primer extension. Primer extension of in vivo-produced lrpC mRNA. Total RNAs from B. subtilis strains 168pHP13 and 168pHP13lrpC were used as templates for primer extension with 32P-end-labeled primer 23. RNA was prepared from exponential-phase (OD600 of 1.0) cells. Lanes: 1, control (without RNA); 2, strain 168pHP13; 3, strain 168pHP13lrpC; M, markers (Promega); 1 to 3, reaction at 90°C for 1 min, 55°C for 10 min, 0°C for 15 min, and extension at 42°C for 1 h; 4 to 8, control sequence performed with plasmid pT712lrpC as the template and the same 5′-end 32P-labeled oligonucleotide primer used for primer extension. The sequence read (corresponding to positions 411 to 440 in Fig. 1) and that of the complementary strand are presented. The +1 and −10 sequences of promoter P1 are indicated. The values to the left are molecular sizes (in bases).

To investigate the possible autoregulation of lrpC, expression of the P2-P1-lacZ fusion was measured either in an lrpC+ context (LF1) or in an lrpC mutant strain (LF1′, lrpC interrupted by the cat gene). Interruption of lrpC causes not an increase in the lrpC transcription level but rather a weak consistent decrease, as shown by (i) the darker coloration of the LF1 strain drop compared to the LF1′ strain drop (Fig. 6B) and (ii) the weaker expression of lrpC in LF1′ compared to LF1 cells grown in LB or minimal medium (Fig. 6C). Therefore, unlike many lrp/asnC genes, the lrpC gene is not negatively autoregulated but appears to be autoregulated in a weak positive manner. This autoregulation could be due to in vivo binding of LrpC to its own 5′ noncoding region, as seen in vitro (Fig. 4 and 5). The addition of leucine (100 μg/ml) to the growth medium did not influence lrpC autoregulation (data not shown). This is in good agreement with the fact that leucine has no effect on in vitro LrpC binding to its own promoter.

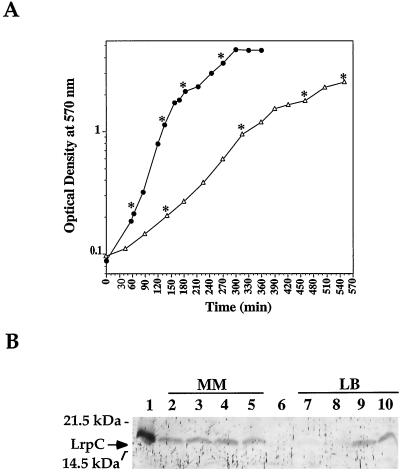

To obtain an overall view of in vivo lrpC expression, the production of LrpC was directly monitored by immunodetection under several growth conditions (Fig. 8) (see Materials and Methods) and the results were compared to those of β-galactosidase assays performed on strain LF1 (Fig. 6C). As shown in Fig. 8B, the level of LrpC did not change during growth in glucose minimal medium or even when growth was prolonged over 4 days (data not shown). The addition of leucine at 100 μg/ml to this medium did not modify the level of LrpC (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Production of lrpC in rich and minimal media during growth. (A) B. subtilis strain 168 was grown in both rich LB medium (●) and glucose minimal supplemented Spizizen medium (MM; ▵) (see Materials and Methods). At different times of growth, indicated by asterisks, cell concentrations were determined and crude protein extracts were prepared. (B) A 12-μg sample of each extract was then subjected to LrpC immunodetection. Lanes: 1, 2.5 ng of pure LrpC protein; 2 to 5, extracts from glucose minimal medium, (OD600, 0.2, 0.95, 1.78, and 2.52); 6, protein extract from FC1 (lrpC mutant) strain; 7 to 10, extracts from LB medium (OD600, 0.22, 1.13, 2.10, and 3.60).

Replacement of glucose with Casamino Acids or glycerol did not alter the LrpC level, although a putative catabolic repression element is present in the 5′ lrpC region (TGGACACGTTTTCA; 7) (coordinates 284 to 297 in Fig. 1). On the contrary, the production of LrpC appeared to be repressed in exponentially growing cells in rich LB medium compared to stationary-phase cells. An estimation of the level of LrpC per cell was made. In stationary-phase cells in glucose minimal medium and LB medium, LrpC represents about 0.0058% of the total protein whereas it decreases to 0.0008% in exponentially growing cells in LB medium. Whereas this repression in exponential phase represents a 6- to 7-fold decrease in the LrpC level, measurement of lrpC expression in LB medium revealed only ∼2.5-fold repression (Fig. 6C). This suggests that an additional factor accounts for the difference in LrpC production during growth in LB medium (see Discussion). The number of LrpC molecules per cell was estimated to be about 100 in minimal medium, 50 in exponential-phase cells in LB medium, and 300 in stationary-phase cells in LB medium. As expected, the levels of LrpC are low under the conditions tested and consistent with the weak lrpC expression levels detected.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of the phenotype of an lrpC mutant, as well as the presence in the LrpC primary sequence of a putative helix-turn-helix motif, suggested that it functions as a transcriptional regulator (3, 5). In order to test this hypothesis, both in vitro DNA-binding properties and in vivo regulatory functions were assessed. In both cases, we took advantage of the fact that all of the genes studied that encode proteins from this Lrp/AsnC family are autoregulated (8, 17, 23, 29, 43).

LrpC binds its own promoter.

We demonstrated that LrpC, like some other members of the LrpC/AsnC family, binds to the upstream 331-bp lrpC region with an apparent Kd of about 4 nM (in tetramers) (Fig. 4B). This Kd is in the range of that measured in the case of specific binding of E. coli Lrp to various promoters (for a review, see reference 6). As is the case for E. coli Lrp, LrpC binding to DNA is specific and cooperative. In contrast to E. coli Lrp, which is a dimer, LrpC is a tetramer in solution (37), suggesting that LrpC binds DNA as a tetramer of four identical subunits.

Analysis of capacities to bind to different parts of the 5′ lrpC region led to the conclusion that the most effective binding site for LrpC corresponds to a region including the P1 promoter. However, LrpC is able to bind to multiple sites in its 5′ noncoding region. The 15-bp sequence that resembles the E. coli Lrp binding site is a minor determinant of LrpC binding. It is more likely that the DNA structure influences LrpC binding, since LrpC also binds in vitro to the curved DNA segment preceding the P1 promoter. This idea has already been proposed for E. coli Lrp, which seems to bind efficiently not only to its consensus sequence but also to promoter regions containing A-T-rich sequences that have been proposed to be intrinsically curved (43). DNase I protection experiments performed in parallel with LrpC revealed no specific protected region but rather hypersensitive sites localized around the P1 region (37), confirming our localization of LrpC binding.

However, the binding of LrpC to multiple sites and the presence of two different types of complexes (I and II, Fig. 4A) suggest that several tetramers of LrpC could actually bind this 5′ lrpC region. Indeed, at very high LrpC/DNA ratios, the appearance of higher-order complexes indicates polymerization and/or aggregation of LrpC on DNA.

Interestingly, the distance separating complexes I and II is more pronounced for the 331-bp fragment than for the 265- and 213-bp fragments (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 6). This might mean that the length of the DNA could influence the mode of binding of LrpC or the effect of LrpC on DNA. Further characterization of LrpC DNA-binding properties should elucidate this point. It should also determine if and how LrpC modifies the DNA conformation upon binding, as observed for E. coli Lrp, Crp, Fis, and IHF (16, 38, 43), as well as the influence of the characteristics of the DNA (length, supercoiling, etc.) on this modification of the DNA conformation.

Regulation of lrpC expression.

Primer extension analysis revealed that the P1 promoter is the major promoter of lrpC in vivo (Fig. 7). Expression from the putative P2 promoter could not be detected under the conditions tested, suggesting that P2 is very poorly expressed. This was confirmed by measuring lacZ reporter gene expression under the control of various parts of the 5′ lrpC region (Fig. 6). However, the computer prediction for this promoter is quite strong and close to the B. subtilis consensus promoter region. This suggests that this putative P2 promoter is expressed conditionally under certain growth conditions not realized in this work. Monitoring of lrpC expression by the lacZ reporter gene demonstrated that lrpC is not negatively autoregulated (Fig. 6), unlike that of many members of the Lrp/AsnC family. lrpC is weakly positively autoregulated. This positive autoregulation is not unique to lrpC; several other B. subtilis regulators are subject to this type of regulation. For example, the B. subtilis spoIIIG gene encoding the sporulation sigma factor ςG (32) or the comK gene, which is essential for the development of genetic competence (40), are both positively autoregulated. Positive autoregulation of these genes increases the concentration of the gene products that are required for triggering sporulation or competence, respectively. In our case, the LrpC protein content in the cell remains low probably because of the low factor of positive autoregulation.

Since LrpC binds to its promoter region in vitro, it appears that autoregulation of lrpC is probably due to direct activation by its product. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of an indirect effect of LrpC, since LrpC could regulate the expression of a gene coding for a protein that regulates the P1 lrpC promoter.

This weak positive mode of autoregulation is unprecedented in the Lrp/AsnC family. This difference in the autoregulation mode is in agreement with our previous indications that LrpC might act in a different way than E. coli Lrp or other Lrp/AsnC family members. Indeed, B. subtilis LrpC has previously been shown, using complementation experiments, to repress the E. coli ilvIH operon normally activated by Lrp (3). LrpC also differs from Lrp by its oligomeric state since it is tetrameric whereas Lrp is dimeric (45) and also by its pI since LrpC is neutral (pI 7.6; our work) whereas Lrp is basic (pI 8.9), two parameters known for their influence on the mode of DNA binding. LrpC therefore appears to be an original member of this Lrp/AsnC family which merits further investigation.

As revealed by monitoring of the expression of lrpC in strain LF1 (lrpC-lacZ), its transcription is repressed two- to threefold in the exponential phase compared to the stationary phase in rich medium (Fig. 6). This repression could be due to various processes, such as another regulatory protein targeting the 5′ lrpC region. For instance, the 15-bp sequence resembling the so-called consensus binding sequence of Lrp from E. coli could be bound by one of the other six B. subtilis Lrp/AsnC proteins, leading to repression of lrpC. Alternatively, the intrinsically curved DNA region could be a target for curved DNA-binding proteins, such as HBsu (50) or the transition state regulator AbrB (35). It is known that E. coli Lrp is negatively regulated by H-NS, a curved-DNA-binding protein that binds to the lrp promoter region (28).

Production of LrpC in rich and minimal media.

The production of the LrpC protein was directly followed during growth in rich and glucose minimal media. LrpC was expressed at a very low level (ranging from about 50 to 300 molecules per cell), confirming the weak β-galactosidase activity observed for the lrpC-lacZ fusions. Furthermore, the level of LrpC was almost constant in cells growing in glucose minimal medium whereas in LB medium it was reduced six- to sevenfold during the exponential phase. This reduction could be explained in part by the repression of lrpC transcription under the latter conditions. However, the level of this repression is only two- to threefold, compared to a six- to sevenfold reduction in LrpC content. This indicates that an additional posttranscriptional factor accounts for this content reduction, such as less efficient translation of LrpC mRNA or increased turnover of LrpC protein in the exponential phase.

Interestingly, azlB, another lrp/asnC-like gene of B. subtilis, is regulated in a completely opposite way with respect to lrpC (2). In the wild-type strain, azlB expression is very low in both rich and minimal media. In rich medium, weak induction of azlB is observed during exponential growth. In an azlB mutant, azlB expression is highly derepressed, demonstrating negative autoregulation, but the induction of expression in the exponential phase is conserved in both rich and glucose minimal media. In contrast, for both LrpC and E. coli Lrp, the levels of proteins are highest during slow growth, pointing to a role for these proteins under unfavorable growth conditions (20). Whereas lrpC and azlB are both members of the B. subtilis lrp-like family, their regulation and function appear to be radically different.

Possible physiological roles for LrpC.

The amount of LrpC in the cell corresponds to 10 to 80 tetramers. These levels are not consistent, at least at first glance, with a global regulatory role for LrpC such as that observed for E. coli Lrp. This is also the case for other Lrp-like proteins, such as BkdR, which is present at 20 to 40 tetramers per cell and is only implicated in the regulation of the branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase system in Pseudomonas putida (23).

Previous experiments have demonstrated the influence of LrpC on sporulation (3). LrpC is also suspected to play a role in the regulation of genes required for long-term adaptation to stress. Indeed, in high-osmolarity minimal medium (1.2 M NaCl), a lrpC mutant strain grew faster than the wild type during early exponential growth (C. Beloin, unpublished results). Furthermore, colonies from an lrpC mutant appeared significantly smaller than those of wild-type cells when grown in LB medium plates at 20°C (Beloin, unpublished). Together, these results suggest that LrpC is a transcriptional regulator of genes induced during processes requiring drastic modification of the bacterial physiology.

Several transition state regulators, such as the AbrB, Sin, and Deg proteins, have been identified in B. subtilis (33). LrpC could be a part of this complex network regulating cell responses to environmental changes. A first indication of this is that the level of LrpC itself responds to environmental changes. Indeed, the LrpC level in minimal medium (100 molecules per cell) and in stationary-phase cells in LB medium (300 molecules per cell) is higher than in exponential-phase cells in LB medium (50 molecules per cell). These data suggest that higher levels of LrpC correlate with nutrition starvation signals, indicating a role for LrpC in response to starvation.

Although the redundancy of the lrp/asnC genes in B. subtilis and information available for four of these proteins (LrpA, LrpB, AzlB, and LrpC) favor specialized functions, we believe they could perhaps act cooperatively in different situations to allow the cell metabolism to adapt to changes in, e.g., the availability of nutrients or other parameters of cell growth. Future analysis should take this possibility into account and should be performed on multiple mutants to gain insights into a more global role for this family of regulatory proteins in bacterial physiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eric Larquet and the Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Microscopy (IGR, Villejuif, France) for providing the DNA-ReSCue program and S. Rety for LrpC pI determination. We thank Y. Hauck, J. Vodolanova, L. Novakova, and A. Blondel for their technical contribution; M. Bayley for her help with the English language; S. Joyce for helpful discussions and corrections; J. L. Gantier for preparing anti-LrpC antibodies; R. Hasan for help with β-galactosidase assays; and H. Putzer for help with RNA extraction.

C. Beloin, R. Exley, and M. Zouine, respectively, acknowledge the receipt of MENESR (French Ministère de l'Éducation Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche) and FRM (Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale) fellowships, a European TMR (Training and Mobility of Researchers) Biotechnology grant (contract BIO4 CT 975141), and MESM (Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur Marocain) and ARC (Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer) fellowships. This work was partially supported by grants from CNRS/Université Paris XI (UMR 2225 and ARC 6794) to F.L.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belitsky B R, Gustafsson M C U, Sonenshein A L, Von Wachenfeldt C. An lrp-like gene of Bacillus subtilis involved in branched-chain amino acid transport. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5448–5457. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5448-5457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beloin C, Ayora S, Exley R, Hirschbein L, Ogasawara N, Kasahara Y, Alonso J C, Le Hégarat F. Characterization of an lrp-like (lrpC) gene from Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s004380050546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolshoy A, McNamara P, Harrington R E, Trifonov E N. Curved DNA without A-A: experimental estimation of all 16 DNA wedge angles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2312–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan R G, Matthews B W. The helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1903–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo J M, Matthews R G. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:466–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.466-490.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambliss G. Carbon source-mediated catabolite repression. In: Sonenshein A, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho K, Winans S C. The putA gene of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is transcriptionally activated in response to proline by an Lrp-like protein and is not autoregulated. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:1025–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui Y, Wang Q, Stormo G D, Calvo J M. A consensus sequence for binding of Lrp to DNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4872–4880. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4872-4880.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dartois V, Liu J, Hoch J A. Alterations in the flow of one-carbon units affect KinB-dependent sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:39–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4491805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Santis P, Palleschi A, Savino M, Scipioni A. Validity of the nearest-neighbor approximation in the evaluation of the electrophoretic manifestations of DNA curvature. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9269–9273. doi: 10.1021/bi00491a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubnau D, Davidoff-Abelson R. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. 1. formation and properties of the donor-recipient complex. J Mol Biol. 1971;56:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernsting B R, Denninger J W, Blumenthal R M, Matthews R G. Regulation of the gltBDF operon of Escherichia coli: how is a leucine-insensitive operon regulated by the leucine-responsive regulatory protein? J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7160–7169. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7160-7169.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haima P, Bron S, Venema G. The effect of restriction on shotgun cloning and plasmid stability in Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;209:335–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00329663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu L M, Giannini J K, Leung T W, Crosthwaite J C. Upstream sequence activation of Escherichia coli argT promoter in vivo and in vitro. Biochemistry. 1991;30:813–822. doi: 10.1021/bi00217a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolb A, Spassky A, Chapon C, Blazy B, Buc H. On the different binding affinities of CRP at the lac, gal and malT promoter regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:7833–7852. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.22.7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kölling R, Lother H. AsnC: an autogenously regulated activator of asparagine synthetase A transcription in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:310–315. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.310-315.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo H S, Crothers D M. Calibration of DNA curvature and a unified description of sequence-directed bending. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1763–1767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landgraf J R, Wu J, Calvo J M. Effects of nutrition and growth rate on Lrp levels in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6930–6936. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6930-6936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larquet E, Furrer P, Stasiak A, Dubochet J, Revet B. DNA ReSCue: 3D reconstruction, simulation and curvature of DNA from the analysis of electron micrographs. J Biomol Struct Dynamics. 1995;12:134. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin R, D'Ari R, Newman E B. λ placMu insertions in genes of the leucine regulon: extension of the regulon to genes not regulated by leucine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1948–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1948-1955.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madhusudhan K T, Huang N, Sokatch J R. Characterization of BkdR-DNA binding in the expression of the bkd operon of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:636–641. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.636-641.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAllister C F, Achberger E C. Effect of polyadenine-containing curved DNA on promoter utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11743–11749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizuno T. Random cloning of bent DNA segments from Escherichia coli chromosome and primary characterization of their structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:6827–6841. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.6827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman E B, D'Ari R, Lin R T. The leucine-Lrp regulon in E. coli: a global response in search of a raison d'être. Cell. 1992;68:617–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman E B, Lin R T, d'Ari R. The leucine/Lrp regulon. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger M E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1513–1525. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oshima T, Ito K, Kabayama H, Nakamura Y. Regulation of lrp gene expression by H-NS and Lrp proteins in Escherichia coli: dominant negative mutations in lrp. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:521–528. doi: 10.1007/BF00290342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peekhaus N, Tolner B, Poolman B, Kramer R. The glutamate uptake regulatory protein (Grp) of Zymomonas mobilis and its relation to the global regulator Lrp of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5140–5147. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5140-5147.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricca E, Aker D A, Calvo J M. A protein that binds to the regulatory region of the Escherichia coli ilvIH operon. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1658–1664. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1658-1664.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt R, Decatur A L, Rather P N, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Bacillus subtilis Lon protease prevents inappropriate transcription of genes under the control of the sporulation transcription factor sigma G. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6528–6537. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6528-6537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith I. Regulatory proteins that control late growth development. In: Sonenshein A, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 785–800. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spizizen J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:407–408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strauch M A, Ayazifar M. Bent DNA is found in some, but not all, regions recognized by the Bacillus subtilis AbrB protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:756–760. doi: 10.1007/BF00290723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Studier W F, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 polymerase to direct the expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tapias A, Lopez G, Ayora S. Bacillus subtilis LrpC is a sequence-independent DNA-binding protein and DNA-bending protein which bridges DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:552–559. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.2.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J F, Landy A. Empirical estimation of protein-induced DNA bending angles: applications to lambda site-specific recombination complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9687–9705. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich S D. A vector for systematic inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1998;144:3097–4104. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Sinderen D, Venema G. comK acts as an autoregulatory control switch in the signal transduction route to competence in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5762–5770. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5762-5770.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Wye J D, Bronson E C, Anderson J N. Species-specific patterns of DNA bending and sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5253–5261. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q, Calvo J M. Lrp, a major regulatory protein in Escherichia coli, bends DNA and can organize the assembly of a higher-order nucleoprotein structure. EMBO J. 1993;12:2495–2501. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Wu J, Friedberg D, Plakto J, Calvo J M. Regulation of the Escherichia coli lrp gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1831–1839. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1831-1839.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ward J B, Jr, Zahler S A. Regulation of leucine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:727–735. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.2.727-735.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willins D A, Ryan C W, Platko J V, Calvo J M. Characterization of Lrp, an Escherichia coli regulatory protein that mediates a global response to leucine. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10768–10774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu H M, Crothers D M. The locus of sequence-directed and protein-induced DNA bending. Nature. 1984;308:509–513. doi: 10.1038/308509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada H, Muramatsu S, Mizuno T. An Escherichia coli protein that preferentially binds to sharply curved DNA. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1990;108:420–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada H, Yoshida T, Tanaka K, Sasakawa C, Mizuno T. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli hns gene encoding a DNA-binding protein, which preferentially recognizes curved DNA sequences. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:332–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00290685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanish-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zouine M, Beloin C, Ghelis C, Le Hégarat F. The L17 ribosomal protein of Bacillus subtilis binds preferentially to curved DNA. Biochimie. 2000;82:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]