Abstract

Variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are continuously emerging, highlighting the importance of regular surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 and other epidemiologically significant pathogenic viruses in the current context. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is expensive, time-consuming, labor-intensive, requires a large reagent volume, and only tests a few targets in a single run. High-throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) utilizing the Biomark HD system (Fluidigm) can be used as an alternative. This study applied an HT-qPCR to simultaneously detect SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, and other pathogenic viruses in wastewater. Wastewater samples were collected from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) quarantine facility between October 2020 and February 2021 (n = 4) and from the combined and separated sewer lines of a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in Yokkaichi, Mie Prefecture, Japan, between March and August 2021 (n = 23 each). The samples were analyzed by HT-qPCR using five SARS-CoV-2, nine SARS-CoV-2 spike gene nucleotide substitution-specific, five pathogenic viruses, and three process control assays. All samples from the quarantine facility tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and the nucleotide substitutions N501Y and S69-70 del (Alpha variant) were detected in the December 2020 sample, coinciding with the first clinical case in Japan. Only three WWTP samples were positive when tested with a single SARS-CoV-2 assay, whereas more than eight samples were positive when tested with all assays, indicating that using multiple assays increases the likelihood of detection. The nucleotide substitution L452R (Delta variant) was detected in the WWTP samples of Mie Prefecture in April 2021, but the detection of Delta variant from patients had not been reported until May 2021. Aichi virus 1 and norovirus GII were prevalent in WWTP samples. This study demonstrated that HT-qPCR may be the most time- and cost-efficient method for tracking COVID-19 and broadly monitoring community health.

Keywords: High-throughput qPCR; Pathogenic viruses, SARS-CoV-2; Wastewater

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The emergence of new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants of concern (VOCs), classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as Alpha, Beta, and Gamma as previously circulating VOCs and Delta and Omicron as currently circulating VOCs has caused a significant threat to public health and the economy. Furthermore, their rapid global spread has presented a significant challenge to global efforts to control coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (WHO, 2021). SARS-CoV-2 VOCs have increased transmission and reinfection rates, increased disease severity, and diminished vaccine efficacy (WHO, 2021). In addition to SARS-CoV-2, it is crucial to monitor other epidemiologically significant pathogens (pathogens causing a significant health impacts on a large number of population), such as influenza virus, norovirus, and pathogenic intestinal bacteria. Rapid surveillance and simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, and other pathogens are crucial to controlling the pandemic.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is now universally used to detect and quantify pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2. Recently, digital PCR (dPCR) is also gaining popularity after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic (Tiwari et al., 2022). qPCR and dPCR have disadvantages, however (Ishii et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2020; Fassy et al., 2021; Tiwari et al., 2022). These methods can detect a single target (singleplex qPCR) or up to five targets (multiplex qPCR) in a single run. Therefore, qPCR and dPCR are time-consuming and labor-intensive when multiple pathogens must be detected in a short period, such as when rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 with multiple mutations is required. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO have recommended reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR assay with validated primers (Lieberman et al., 2020) for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Due to the global expansion of COVID-19 clinical testing, reagent shortages have arisen, further delaying the efficient detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and its variants (Sysmex Corporation, 2022). In this situation, pathogen detection and quantification techniques that require a minimal amount of reagents are necessary.

The above-mentioned limitations of conventional qPCR can be overcome by developing a high-throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) system based on the microfluidic technique. This new technique, performed with the Biomark HD system (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA, USA; currently Standard BioTools), is based on microfluidic technology and is a nanofluidic automated qPCR system employing dynamic arrays of integrated fluidic circuits (IFCs). In a single HT-qPCR run, a single 48.48 IFC chip permits 2304 reactions with 10.1 nL per chamber. Thus, in comparison to conventional qPCR, HT-qPCR conducts more reactions per plate, allowing for the simultaneous detection and quantification of a large number of pathogens, thereby reducing cost, time, labor, and reagents requirement. However, the initial cost for the Biomark HD system is relatively higher (approximately 10 times) than the conventional qPCR. In addition, all assays should have the same thermal condition and there is also a possibility of cross-reaction if the target sites are common.

Wastewater surveillance utilizes pooled samples from communities and is, therefore, a cost-effective and widely used method for tracking diseases in communities in real time (Ahmed et al., 2020; Bivins et al., 2020; Kitajima et al., 2020; Haramoto et al., 2020; Tandukar et al., 2022). Although a previous study reported the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater from a building even with a very low number of infected people (de Araújo et al., 2022), wastewater typically contains low viral loads, which hinders the efficient detection of pathogens. In the HT-qPCR method, a specific target is pre-amplified to increase the likelihood of detecting target genetic materials present in low quantities in samples. A previous study reported the detection and quantification of pathogens even at low concentrations (2 copies/μL) after the application of the preamplification step (Ishii et al., 2013). A previous study reported relatively lower assay limit of detection (ALOD) of RT-dPCR (2.9 and 4.6 copies/reaction for CDC N1 and CDC N2, respectively) than the RT-qPCR (14 and 11 copies/reaction for CDC N1 and CDC N2 assays, respectively) (Ahmed et al., 2022). Consequently, the HT-qPCR is particularly useful for monitoring pathogens present in low concentrations. This study aims to apply an HT-qPCR to simultaneously detect and quantify SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, and other epidemiologically significant pathogenic viruses in a single run.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Collection of water samples

A total of four grab wastewater samples were collected between October 2020 and February 2021 from a septic tank installed in a COVID-19 quarantine facility in Japan housing COVID-19 patients with mild illness (Iwamoto et al., 2022). In addition, 46 grab wastewater samples were also collected from the Hinaga wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in Yokkaichi, Mie Prefecture, Japan, having two treatment lines, one with a combined sewer system which collected stormwater along with wastewater and the other with a separated sewer system which collected only wastewater, once a week from March to August 2021 (23 samples each). Wastewater samples collected from the quarantine facility were first heated at 60 °C for 90 min and cooled at 4 °C for safety reasons.

2.2. Virus concentration, RNA extraction, and RT

The polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation method was used for virus concentration. Briefly, 4.0 g of polyethylene glycol 8000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.94 g of NaCl (Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) were added to 40 mL of wastewater sample and mixed for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the tube was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 99 min at 4 °C, then the supernatant was removed leaving approximately 5 mL of the sample. The tube was centrifuged again at 12,000 ×g for 5 min at 4 °C to completely remove the supernatant and the resultant pellet was finally resuspended in 800 μL of PCR-grade water to obtain a virus concentrate. This is a modified method from a previous study (Torii et al., 2022).

As recommended previously (Haramoto et al., 2018), 1 μL of a mixture of F-specific RNA coliphage MS2 (ATCC 15597-B1; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and Pseudomonas bacteriophage Φ6 (NBRC 105899; National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Tokyo, Japan) was added to 140 μL of the virus concentrate and PCR-grade water (i.e., a non-inhibitory control (NIC) sample) as molecular process controls (MPCs). RNA was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) to obtain 60 μL of RNA extract. Subsequently, a 30 μL of viral RNA was subjected to RT using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to obtain a 60-μL cDNA, following the manufacturer's protocol.

The extraction-RT-qPCR efficiencies were calculated from the concentration of MS2 phage (Friedman et al., 2011) and Φ6 phage (Gendron et al., 2010) in sample and NIC tubes as the ratio of the concentration of cDNA in a sample qPCR tube to that in a NIC tube.

The calculated extraction-RT-qPCR efficiencies of the MPCs higher than the recommended level (>10 %) (Benabbes et al., 2013; da Silva et al., 2007), 47.1 ± 24.5 % (n = 46) for MS2 phage and 83.9 ± 48.9 % (n = 46) for Φ6 phage, indicated that there was no substantial loss and/or inhibition in the water samples during RNA extraction, RT, and qPCR.

2.3. Pre-amplification of cDNA

Initially, forward and reverse primer pair mixes (20 μM each) of each assay were combined and diluted to prepare a pooled assay in a single tube so that each primer is at a final concentration of 200 nM (Ishii et al., 2013). Pre-amplification mix (5 μL) was prepared using 1.0 μL of PreAmp Master Mix (Fluidigm), 1.25 μL of the pooled assay, 1.50 μL of PCR-grade water, and 1.25 μL of cDNA or positive or negative controls (Fluidigm Corporation, 2016). Ten-fold serial dilutions (1.0 × 105 (1.0 × 104 for SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA qPCR assays) to 1.0 copies/1.25 μL) of gBlocks (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, LA, USA) or artificially synthesized plasmid DNA (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan, or Eurofins Genomics, Tokyo, Japan) were used to create a standard curve, except for the NIID_2019-nCOV_N (NIID) (Shirato et al., 2020) and N_Sarbeco (Corman et al., 2020) assays for which ten-fold serial dilutions from 2.0 × 104 to 2.0 copies/1.25 μL were used. PCR-grade water was used as a negative control. Pre-amplification was performed in a TaKaRa PCR Thermal Cycler Dice Touch (Takara Bio) and the thermal conditions included an initial activation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 14 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 4 min (Ishii et al., 2013). The amplified PCR products were diluted with TE buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 12090015) in a 1:5 ratio.

2.4. HT-qPCR

Initially, a total of 24 different qPCR assays were tested for the purpose of development of HT-qPCR and applied to wastewater samples as shown in Table 1 . This included five qPCR assays specific to SARS-CoV-2 which can detect both prototype Wuhan virus and the mutants (CDC N1, CDC N2, CDC N1 + N2 (CDC, 2020), N_Sarbeco (Corman et al., 2020), and NIID (Shirato et al., 2020)), ten SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA qPCR assays (D80A, E484Q, K417N, T19R, and T478K (Lee et al., 2021), E484K and L452R (Wang et al., 2021), N501Y (Bedotto et al., 2021), and ND3L and S69-70 del (Peterson et al., 2022)), six qPCR assays of epidemiologically significant pathogenic viruses (influenza A virus (InfA) (Nakauchi et al., 2011), noroviruses of genogroups I (NoV-GI) and II (NoV-GII) (Kageyama et al., 2003), enteroviruses (EnV) (Katayama et al., 2002; Shieh et al., 1995), rotaviruses A (RVA) (Jothikumar et al., 2009), and Aichi virus 1 (AiV-1) (Kitajima et al., 2013)), one wastewater indigenous virus, pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) (Zhang et al., 2006; Haramoto et al., 2013), and two molecular process control qPCR assays, Φ6 (Gendron et al., 2010) and MS2 (Friedman et al., 2011) phages, except for the quarantine facility samples and the WWTP samples collected from March to June 2021, for which five SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA qPCR assays were not tested (D80A, E484Q, K417N, T19R, and T478K). In addition, conventional qPCR was also performed for PMMoV assay to compare its concentration with that of HT-qPCR. The procedure for the conventional qPCR is described in a previous study (Haramoto et al., 2020). In this study, epidemiologically significant pathogens were chosen based on previous research on the review of the prevalence of human enteric viruses in environmental water worldwide, especially the viruses prevalent in raw and treated wastewater (Haramoto et al., 2018) which did not enlist human polyomaviruses and hepatitis A virus as prevalent viruses. In addition, a study on the epidemiology of gastroenteritis viruses in Japan (Thongprachum et al., 2016) was also accessed. Few studies have reported a very low hepatitis A virus antibody sero-prevalence profile in Japan (Yamamoto et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Primers and probes used in HT-qPCR.

| Target | Assay | Function | Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Product length (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | CDC-N1 | Forward primer | 2019-nCoV_N1-F | GACCCCAAAATCAGCGAAAT | 72 | CDC, 2020 |

| Reverse primer | 2019-nCoV_N1-R | TCTGGTTACTGCCAGTTGAATCTG | ||||

| Probe | 2019-nCoV_N1-P | FAM-ACCCCGCAT/ZEN/TACGTTTGGTGGACC-IBFQ | ||||

| CDC-N2 | Forward primer | 2019-nCoV_N2-F | TTACAAACATTGGCCGCAAA | 67 | CDC, 2020 | |

| Reverse primer | 2019-nCoV_N2-R | GCGCGACATTCCGAAGAA | ||||

| Probe | 2019-nCoV_N2-P | FAM-ACAATTTGC/ZEN/CCCCAGCGCTTCAG-IBFQ | ||||

| NIID | Forward primer | NIID_2019-nCOV_N_F2 | AAATTTTGGGGACCAGGAAC | 158 | Shirato et al., 2020 | |

| Reverse primer | NIID_2019-nCOV_N_R2ver3 | TGGCACCTGTGTAGGTCAAC | ||||

| Probe | NIID_2019-nCOV_N_P2 | FAM-ATGTCGCGC/ZEN/ATTGGCATGGA-IBFQ | ||||

| N_Sarbeco | Forward primer | N_Sarbeco_F1 | CACATTGGCACCCGCAATC | 128 | Corman et al., 2020 | |

| Reverse primer | N_Sarbeco_R1 | GAGGAACGAGAAGAGGCTTG | ||||

| Probe | N_Sarbeco_P1 | FAM-ACTTCCTCA/ZEN/AGGAACAACATTGCCA-IBFQ | ||||

| Nucleotide substitutions | D80A | Forward primer | MT-F-D80A | ACCAATGGTACTAAGAGGTTCGC | 81 | Lee et al., 2021 |

| Reverse primer | R-D80 | GTTAGACTTCTCAGTGGAAGCA | ||||

| Probe | Ps-D80 | FAM-ACCCTGTCC/ZEN/TACCATTTAATGATGGTGT- IBFQ | ||||

| E484K | Forward primer | E484K_FWD | CTGAAATCTATCAGGCCGGTA | 133 | Wang et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | E484K_REV | GAAAGTACTACTACTCTGTATGG | ||||

| Probe | E484K_MT_CY5 | FAM-CTTGTAATG/ZEN/GTGTTAAAGGTTT-IBFQ | ||||

| E484Q | Forward primer | MT-F-E484Q | GCACACCTTGTAATGGTGCTC | 109 | Lee et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | R-E484 | GTACTACTACTCTGTATGGTTGGTAAC | ||||

| Probe | Ps-E484 | FAM-TGGTTTCCA/ZEN/ACCCACTAATGGTGTTG-IBFQ | ||||

| K417N | Forward primer | F-K417N | TAGAGGTGATGAAGTCAGACAA | 76 | Lee et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | R-MT-K417N | TCTGGTAATTTATAATTATAATCAGCAGTA | ||||

| Probe | Pas-K417 | FAM-TTTCCAGTT/ZEN/TGCCCTGGAGCGAT-IBFQ | ||||

| L452R | Forward primer | L452R_REV | CTTGATTCTAAGGTTGGTGGTAA | 79 | Wang et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | L452R_FWD | CTCTCTCAAAAGGTTTGAGATTAGACT | ||||

| Probe | L452R_MT_HEX | FAM-CCTAAACAA/ZEN/TCTATACCGGTAATT-IBFQ | ||||

| ND3L | Forward primer | F | TTAGAGTATCATGACGTTCGTGTTG | 94 | Peterson et al., 2022 | |

| Reverse primer | R | GGTGCATTTCGCTGATTTTGG | ||||

| Probe | Variant | FAM-AATGTCTCTAAATGGACC-NFQ-MGB | ||||

| N501Y | Forward primer | Pri_IHU_N501Y_F1 | ATCAGGCCGGTAGCACAC | 156 | Bedotto et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | Pri_IHU_N501Y_R1 | AAACAGTTGCTGGTGCATGT | ||||

| Probe | Pro_IHU_C_GB_1_MBP | FAM-CCACTTATG/ZEN/GTGTTGGTTACCAA-IBFQ | ||||

| S69-70 del | Forward primer | F | CATTCAACTCAGGACTTGTTCTTACC | 104 | Peterson et al., 2022 | |

| Reverse primer | R | GGTAGGACAGGGTTATCAAACCTC | ||||

| Probe | Variant | FAM-TCCATGCTATCTCTG-NFQ-MGB | ||||

| T19R | Forward primer | MT-F-T19R | AGTCTCTAGTCAGTGTGTTAATCTCAG | 136 | Lee et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | R-T19 | AGAACAAGTCCTGAGTTGAATGTA | ||||

| Probe | Ps-T19 | FAM-TCACACGTG/ZEN/GTGTTTATTACCCTGACA-IBFQ | ||||

| T478K | Forward primer | F-T478 | TGTTTAGGAAGTCTAATCTCAAACC | 91 | Lee et al., 2021 | |

| Reverse primer | MT-R-T478K | CCTTCAACACCATTACAAGATT | ||||

| Probe | Pas-T478 | FAM-TGCTACCGG/ZEN/CCTGATAGATTTCAGTTG-IBFQ | ||||

| Pathogenic viruses | AiV-1 | Forward primer | Forward primer | GTCTCCACHGACACYAAYTGGAC | 108–111 | Kitajima et al., 2013 |

| Reverse primer | Reverse primer | GTTGTACATRGCAGCCCAGG | ||||

| Probe | Probe | FAM-TTYTCCTTYGTGCGTGC-NFQ-MGB | ||||

| EnV | Forward primer | Forward primer | CCTCCGGCCCCTGAATG | 195 | Shieh et al., 1995 | |

| Reverse primer | Reverse primer | ACCGGATGGCCAATCCAA | ||||

| Probe | Probe | FAM-CCGACTACTTTGGGTGTCCGTGTTTC-TAMRA | Katayama et al., 2002 | |||

| InfA | Forward primer | MP-39-67For | CCMAGGTCGAAACGTAYGTTCTCTCTATC | 146 | Nakauchi et al., 2011 | |

| Reverse primer | MP-183-153Rev | TGACAGRATYGGTCTTGTCTTTAGCCAYTCCA | ||||

| Probe | MP-96-75ProbeAs | FAM-ATYTCGGCTTTGAGGGGGCCTG-NFQ-MGB | ||||

| NoV-GI | Forward primer | Primer COG1F | CGYTGGATGCGNTTYCATGA | 85 | Kageyama et al., 2003 | |

| Reverse primer | Primer COG1R | CTTAGACGCCATCATCATTYAC | ||||

| Probe | RING1(b)-TP | FAM-AGATYGCGATCYCCTGTCCA-TAMRA | ||||

| NoV-GII | Forward primer | Primer COG2F | CARGARBCNATGTTYAGRTGGATGAG | 98 | Kageyama et al., 2003 | |

| Reverse primer | Primer COG2R | TCGACGCCATCTTCATTCACA | ||||

| Probe | Probe RING2-TP | FAM-TGGGAGGGCGATCGCAATCT-TAMRA | ||||

| RVA | Forward primer | JVKF | CAGTGGTTGATGCTCAAGATGGA | 131 | Jothikumar et al., 2009 | |

| Reverse primer | JVKR | TCATTGTAATCATATTGAATACCCA | ||||

| Probe | JVKP | FAM-ACAACTGCAGCTTCAAAAGAAGWGT-TAMRA | ||||

| Process control | MS2 phage | Forward primer | Not available | ATCCATTTTGGTAACGCCG | 68 | Friedman et al., 2011 |

| Reverse primer | Not available | TGCAATCTCACTGGGACATAT | ||||

| Probe | Not available | FAM-TAGGCATCTACGGGGACGA-NFQ-MGB | ||||

| Phi6 phage | Forward primer | Not available | TGGCGGCGGTCAAGAGC | 232 | Gendron et al., 2010 | |

| Reverse primer | Not available | GGATGATTCTCCAGAAGCTGCTG | ||||

| Probe | Not available | FAM-CGGTCGTCG/ZEN/CAGGTCTGACACTCGC-IBFQ | ||||

| PMMoV | Forward primer | PMMV-FP1 | GAGTGGTTTGACCTTAACGTTTGA | 68 | Zhang et al., 2006 | |

| Reverse primer | PMMV-FP1-rev | TTGTCGGTTGCAATGCAAGT | Haramoto et al., 2013 | |||

| Probe | PMMV-Probe1 | FAM-CCTACCGAAGCAAATG-NFQ-MGB | Zhang et al., 2006 |

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; IBFQ, Iowa Black Fluorescent quencher; MGB, minor groove binder; NFQ, nonfluorescent quencher; TAMRA, 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine; B = G/T/C; N = A/G/C/T; R = G/A; Y=C/T.

HT-qPCR was performed on the Biomark HD system using a 48.48 dynamic arrays IFC, which allowed to analyze 48 independent samples against 24 different qPCR assays in duplicate, totaling 2304 reaction chambers with 10.1 nL per chamber in one experiment. The reaction mixtures were prepared following the previous study, with slight modifications (Ishii et al., 2013). Briefly, each 10× assay mix (14 μL) contained 7.0 μL of 2× Assay Loading Reagent (Fluidigm), 5.6 μL of 20 μM primer pair mix with a final concentration of 8 μM of each primer, and 1.4 μL of 10 μM probe of each assay with a final concentration of 1 μM of each probe and sample premix (6.0 μL) contained 3.0 μL of TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific), 0.3 μL of 20× GE Sample Loading Reagent (Fluidigm), and 2.7 μL of 5-fold diluted pre-amplified cDNA. Control line fluid was injected to 48.48 IFC before priming in an IFC controller (MX; Fluidigm). After priming, 5.0 μL of 10× assay mix of each assay was applied to the assay inlet of primed IFC in duplicate and 5.0 μL of sample mix in the sample inlet and loaded with the IFC controller. Finally, the loaded IFC was transferred to the Biomark HD system and HT-qPCR was performed following the thermal cycling conditions mentioned previously (Ishii et al., 2013), except for the annealing step of 70 °C for 5 s which was not included in this study. The thermal cycling conditions included incubation at 50 °C for 2 min, followed by 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Negative control for the Biomark HT-qPCR contained 2.25 μL of PCR-grade water and 2.75 μL of sample premix.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test was used to compare the positive ratios of the detection of at least one SARS-CoV-2 assay and pathogenic viruses between the combined and the separated sewer systems, whereas paired t-test was used to compare the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by different SARS-CoV-2 assays in the quarantine facility and to compare the concentration of PMMoV between the conventional- and HT-qPCRs. The statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and a significant value was set at p = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Development of HT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses

To develop a HT-qPCR for simultaneous monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 variants and other pathogenic viruses in wastewater, different combinations of the qPCR assays targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA, SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, and epidemiologically important pathogenic virus genes were tested. A total of 24 assays were used for initial screening and the two assays, ND3L and RVA, that did not exhibit fluorescence signals were excluded. However, ND3L and RVA assays showed good performance in a conventional qPCR with efficiencies of 105 % and 92 %, slopes of the standard curves −3.20 and −3.53, y-intercepts 42.5 and 43.8, and the coefficient of determination (R2) 0.990 and 0.999, respectively. Finally, a total of 22 assays were selected, as mentioned above in Section 2.4, including five SARS-CoV-2 assays (CDC N1, CDC N2, CDC N1 + N2, N_Sarbeco, and NIID), nine SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substitution-specific qPCR assays (D80A, E484K, E484Q, K417N, L452R, N501Y, S69-70 del, T19R, and T478K), five qPCR assays of pathogenic viruses (InfA, NoV-GI, NoV-GII, EnV, and AiV-1), one wastewater indigenous virus (PMMoV), and two molecular process control qPCR assays (Φ6 and MS2 phages). The qPCR amplification efficiencies of SARS-CoV-2, nucleotide substitution-specific, and pathogenic virus assays were 90.6 ± 10.1 % (n = 5), 68.2 ± 17.1 % (n = 9), and 90.8 ± 13.7 % (n = 5), respectively, and the negative controls were consistently negative. The slopes of the standard curves were −3.60 ± 0.26, −4.60 ± 0.81, and −3.60 ± 0.39; y-intercepts were 27.6 ± 1.70, 33.9 ± 6.5, and 30.8 ± 3.9; and the R2 values were 0.987 ± 0.02, 0.981 ± 0.03, and 0.991 ± 0.01 for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 5), nucleotide substitution-specific (n = 9), and pathogenic virus assays (n = 5), respectively. The lower limits of detection (LOD) were 1.0 × 101 copies/1.25 μL for all SARS-CoV-2 assays, 1.0 × 102 copies/1.25 μL for all SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substitution-specific and pathogenic virus assays, except for N501Y, T19R, and T478K nucleotide substitution-specific assays and AiV-1 and InfA pathogenic virus assays for which the LOD value was 1.0 × 101 copies/1.25 μL.

3.2. Detection of PMMoV in the quarantine facility and WWTP

To evaluate the sample preparation processes from PEG precipitation to pre-amplification of cDNA, indigenous virus, PMMoV, was tested. PMMoV was detected in all the samples tested with a mean concentration of 9.0 ± 0.2 log copies/L (n = 4) in the quarantine facility and 8.5 ± 0.2 log copies/L (n = 23) and 8.7 ± 0.2 log copies/L (n = 23) in combined and separated sewer lines, respectively.

3.3. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and nucleotide substituted RNA in the quarantine facility

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in all wastewater samples (n = 4) collected from the quarantine facility by all five SARS-CoV-2 HT-qPCR assays as shown in Table 2 . CDC N1 assay showed the highest SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration (7.2 ± 1.1 log copies/L) among the five SARS-CoV-2 assays tested (paired t-test; p < 0.05). However, there was no substantial difference in the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA obtained from other assays. The concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA increased from October to December 2020 but sharply decreased in February 2021. Nucleotide substitutions, N501Y, mainly found in Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants and S69-70 del, mainly found in Alpha variant (previously termed as UK variant at the time of survey) were detected in the sample collected in December 2020 with the concentration of 7.1 log copies/L each (Table 2) when the highest concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was observed. There was a difference of 1.4 log between the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and nucleotide substitution RNA in that sample, indicating that all the COVID-19 positive patients isolated in the quarantine facility were not positive for variants.

Table 2.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA in a COVID-19 quarantine facility by HT-qPCR.

| Date of sample collection (dd/mm/yyyy) | SARS-CoV-2 RNA (log copies/L) |

SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA (log copies/L) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC N1 | CDC N2 | CDC N1 + N2 | NIID | N_Sarbeco | E484K | L452R | N501Y | S69-70 del | |

| 27/10/2020 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 27/11/2020 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 7.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 24/12/2020 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 7.8 | ND | ND | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| 21/2/2021 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 5.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| No. of positive samples (%) | 4 (100 %) | 4 (100 %) | 4 (100 %) | 4 (100 %) | 4 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (25 %) | 1 (25 %) |

| Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | NA | NA | 7.1 | 7.1 |

SD, standard deviation; ND, not detected; NA, not applicable.

Mean concentration of positive samples.

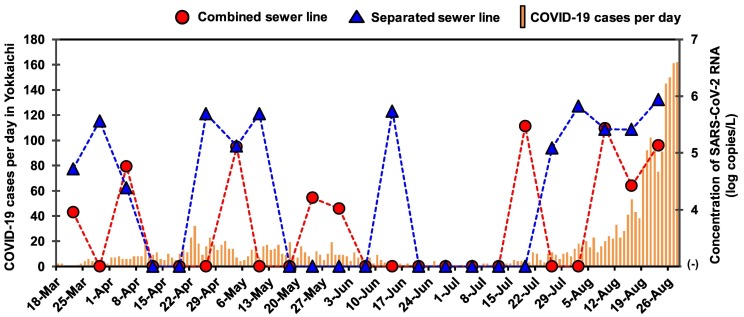

3.4. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in WWTP

Table 3 shows the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in samples from the WWTP in Yokkaichi, Mie Prefecture. Of the total 23 samples each from the combined and separated sewer lines, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected more frequently by CDC N2 (26%) and CDC N1 + N2 assays (26 %) in the combined sewer line samples, whereas this RNA was more frequently detected by CDC N1 (30%) and N_Sarbeco assays (30 %) in the separated sewer line samples as shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the positive ratio of detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by CDC N1 (22%, 10/46) and CDC N2 (24 %, 11/46) and by at least one assay between the combined (39 %, 9/23) and separated sewer line samples (52 %, 12/23) (Chi-square test; p > 0.05). The range of concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was 4.8 ± 1.3–5.3 ± 0.5 log copies/L and 5.3 ± 0.8–5.6 ± 0.6 log copies/L in the combined and separated sewer lines, respectively. The samples collected in August were more frequently positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in both combined (75 %, 3/4) and separated sewer lines (100 %, 4/4) compared to those of other months. The concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the WWTP samples, tested by CDC N1, CDC N2, CDC N1 + N2, NIID, and N_Sarbeco assays, and the reported COVID-19 cases in Yokkaichi during the respective time period are shown in Fig. 1 . When SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected by more than one assays in a single sample, the average concentration was calculated. The WWTP samples collected during August had frequent detection and increased concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and the reported COVID-19 cases also peaked in August.

Table 3.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA in WWTP samples by HT-qPCR.

| Date of sample collection | SARS-CoV-2 RNA |

SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC N1 | CDC N2 | CDC N1 + N2 | NIID | N_ Sarbeco | D80A | E484K | E484Q | K417N | N501Y | L452R | S69-70 del | T19R | T478K | |

| 22-Mar | −/− | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | +/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 29-Mar | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 5-Apr | +/+ | +/− | +/− | −/− | −/+ | NT | −/+ | NT | NT | −/− | −/+ | −/− | NT | NT |

| 12-Apr | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 19-Apr | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 26-Apr | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 4-May | −/+ | +/− | +/− | +/− | −/+ | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | +/− | NT | NT |

| 10-May | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ | NT | −/− | NT | NT | +/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 18-May | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 24-May | −/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | +/− | −/− | +/− | NT | NT |

| 31-May | −/− | −/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 7-Jun | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 14-Jun | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ | NT | −/− | NT | NT | −/− | −/− | −/− | NT | NT |

| 21-Jun | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 28-Jun | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5-Jul | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 12-Jul | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 19-Jul | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | +/− | −/− | −/− |

| 26-Jul | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 2-Aug | −/+ | −/− | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 9-Aug | +/− | +/+ | +/− | +/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 16-Aug | −/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | −/− |

| 23-Aug | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/+ | −/+ | −/− |

| No. of positive samples | 3/7 | 6/5 | 6/5 | 4/3 | 4/7 | 1/0 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/0 | 2/1 | 3/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 |

+, detected; −, not detected; NT, not tested.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA in the combined and separated sewer lines is designated by ‘/’ (combined/separated sewer lines).

Fig. 1.

Number of daily new reported cases of COVID-19 and the concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in influent samples of combined (denoted by solid circle) and separated sewer lines (denoted by solid triangle).

3.5. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA in WWTP

In total, nine SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substitutions were tested in the WWTP samples, except for those collected until June 14 for which only four genes were tested, as shown in Table 4 . The E484K (Beta and Gamma label) and L452R (Delta and Kappa label) nucleotide substitutions were detected in the separated sewer line sample collected on April 5. The N501Y and the S69-70 del nucleotide substituted RNA was detected in two samples collected in May and one sample was positive for both. Out of four samples collected from the combined sewer line in July, one sample was positive for L452R and S69-70 del nucleotide substituted RNA. In August, six different nucleotide substituted RNA were detected (D80A, E484Q, K417N, L452R, S69-70 del, and T19R) and one sample collected on August 23 from the separated sewer line was positive for four nucleotide substituted RNA (E484Q, K417N, S69-70 del, and T19R). Another sample collected on August 16 was positive for D80A and T19R genes. The range of mean concentrations of the nucleotide substituted RNA was 2.9–6.1 log copies/L and 5.3–7.0 log copies/L in the combined and separated sewer lines, respectively, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 in WWTP samples.

| WWTP sample | No. of samples tested | Mean ± SDb (log copies/L) (no. of positive samples) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 RNA |

SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA |

||||||||||||||

| CDC N1 | CDC N2 | CDC N1 + N2 | NIID | N_Sarbeco | D80Aa | E484K | E484Qa | K417Na | L452R | N501Y | S69-70 del | T19Ra | T478Ka | ||

| Combined sewer line | 23 | 5.3 ± 0.5 (3) | 4.9 ± 0.3 (6) | 5.0 ± 0.7 (6) | 4.8 ± 1.3 (4) | 5.0 ± 0.7 (4) | 2.9 (1) | NA (0) | NA (0) | NA (0) | 5.6 ± 0.6 (2) | 6.1 ± 0.1 (2) | 6.0 ± 0.2 (3) | 5.3 (1) | NA (0) |

| Separated sewer line | 23 | 5.5 ± 0.5 (7) | 5.5 ± 0.4 (5) | 5.6 ± 0.6 (5) | 5.5 ± 0.8 (3) | 5.3 ± 0.8 (7) | NA (0) | 7.0 (1) | 5.3 (1) | 6.4 (1) | 5.7 (1) | NA (0) | 5.6 (1) | 5.4 (1) | NA (0) |

NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

No. of samples tested = 10 each for the combined and separated sewer lines.

Mean concentration of positive samples.

3.6. Detection of pathogenic viruses in COVID-19 quarantine facility and WWTP

The detection ratio and concentration of pathogenic viruses in the samples from the quarantine facility and WWTPs are shown in Table 5 . At least one pathogenic virus tested was detected in each sampling event in the quarantine facility. AiV-1 was detected in the samples collected in December 2020 and in February 2021 with a mean concentration of 6.3 ± 0.6 log copies/L (n = 2). Likewise, EnV was detected in the sample collected in October 2020 (5.4 log copies/L) and NoV-GII in November 2020 (6.3 log copies/L). On the other hand, InfA and NoV-GI were not detected in any of the samples from the quarantine facility.

Table 5.

Positive ratios and mean concentrations of pathogenic viruses in the quarantine facility and WWTP samples.

| WWTP sample | No. of samples tested | AiV-1 |

EnV |

InfA |

NoV-GI |

NoV-GII |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive samples (%) | Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | No. of positive samples (%) | Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | No. of positive samples (%) | Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | No. of positive samples (%) | Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | No. of positive samples (%) | Mean ± SDa (log copies/L) | ||

| Quarantine facility | 4 | 2 (50) | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 1 (25) | 5.4 | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (25) | 6.3 |

| Combined sewer line | 23 | 18 (78) | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 3 (13) | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 0 (0) | NA | 3 (13) | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 16 (70) | 6.6 ± 0.6 |

| Separated sewer line | 23 | 19 (83) | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 4 (17) | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 1 (4) | 2.4 | 5 (22) | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 20 (87) | 6.9 ± 0.6 |

NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Mean concentration of positive samples.

Of the total 23 samples of the combined sewer line tested, AiV-1 (78 %, 5.5 ± 0.9 log copies/L) and NoV-GII (70 %, 6.6 ± 0.6 log copies/L) were detected more frequently than EnV (13 %, 5.7 ± 0.2 log copies/L) and NoV-GI (13 %, 5.4 ± 1.3 log copies/L). None of the tested samples were positive for InfA. Similarly, out of 23 samples of the separated sewer line, AiV-1 (83 %, 5.7 ± 0.9 log copies/L) and NoV-GII (87 %, 6.9 ± 0.6 log copies/L) were detected more frequently compared to EnV (17 %, 5.9 ± 0.6 log copies/L), NoV-GI (22 %, 5.7 ± 1.4 log copies/L), and InfA (4 %, 2.4 log copies/L). All of the combined sewer line samples and all but one separated sewer line sample were positive for at least one pathogenic virus. More importantly, there was no significant difference in the detection of any of the tested pathogenic viruses in the combined and the separated sewer lines (Chi-square test; p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study established an HT-qPCR technique to simultaneously test 22 different assays, including SARS-CoV-2, nucleotide substitutions, and other pathogenic viruses in a single run. HT-qPCR overcomes some of the drawbacks of conventional qPCR including a larger number of reactions per plate, making it cost- and time-efficient, smaller reaction volume required that is reduced from 10 μL to 10 nL volume, which will be very advantageous when there is a short supply of reagents and consumables. With the continuous emergence of variants, it is essential to develop a tool that is capable of detecting SARS-CoV-2 and identifying variant types in samples in a single run. In the present study, we adapted HT-qPCR to detect SARS-CoV-2 and its variants simultaneously. Compared to sequencing, HT-qPCR becomes more cost-effective and flexible and has important implications in the epidemiological monitoring of the pandemic. Recently, the Omicron variant is circulating all over the world. Unlike other variants, it has more than fifty mutation sites, which makes it difficult to identify by a singleplex qPCR or even multiplex qPCR which normally targets up to four different sites or genes. Thus, this technique could be an effective tool for the initial screening of the variants or other target genes. In addition, the assimilation of qPCR assays can be changed easily as a rapid response to the emergence of new mutant strain and pathogens.

The range of amplification efficiencies were 82.2–114.5 % and 76.4–113.4 % for SARS-CoV-2 and pathogenic virus assays, respectively. However, the range of amplification efficiency of the nucleotide substitution-specific assays was 45.1–99.8 %. In the preamplification step, forward and reverse primers of 22 assays were mixed in a single reaction tube and preamplified. During the amplification process, cross-reaction of the targets might have occurred because the target sites of most of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA assays were common, thus, resulting to low amplification efficiencies for the SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA qPCR assays. The forward primers of CDC-N2 and NIID assays have the possibility of cross-reactions with the reverse primers of NIID and CDC-N2 assays, respectively. However, the qPCR efficiencies of CDC-N2 and NIID assays were in the range of 82.2–93.8 %, meaning that there was no substantial loss in PCR amplification. Similarly, there is a possibility of cross-reaction among S gene primers, such as forward primer of S69-70 del assay with reverse primer of D80A assay; forward primer of E484Q assay with reverse primers of E484K and N501Y assays; forward primer of E484K assay with reverse primers of E484Q, N501Y, and T478k assays; forward primer of N501Y assay with reverse primers of E484K and E484Q assays; forward primer of T478K assay with reverse primers of E484K, E484Q, and N501Y assays; forward primer of L452R with reverse primers of E484K, E484Q, T478K, and N501Y assays. However, the possible cross-reactions were not considered while calculating the concentration of the targets. Avoiding the use of assays which target the overlapping sequence could provide the solution. Thus, the following combinations could be mixed in pre-amplification without any significant problem: CDC N1, N_Sarbeco, ND3L, and CDC N2 or NIID assays for N-gene target and S69-70 del or D80A, T19R, and K417N or L452R or T478K or E484K or E484Q or N501Y assays for S-gene target. However, it is recommended to perform preliminary trials to check for the possible combinations of the assays if used different reagents and thermal cycler platforms.

The detection of PMMoV, the most abundant virus in wastewater (Kitajima et al., 2014) in all the tested samples in this study with the concentration of 7.9–9.1 log copies/L, which is similar to the concentration reported in previous studies (Haramoto et al., 2020; Tori et al., 2022), indicates that HT-qPCR can be successfully applied to the wastewater samples. There was no significant difference in the mean concentration of PMMoV between the conventional qPCR (8.5 ± 0.3 log copies/L in the combined and 8.7 ± 0.3 log copies/L in the separated sewer line samples, n = 23 each) and HT-qPCR (8.5 ± 0.2 log copies/L in the combined and 8.7 ± 0.2 log copies/L in the separated sewer line samples, n = 23 each) (paired t-test; p > 0.05). The samples from the combined and separated sewer lines were collected without avoiding the rainy days and the average rainfall during the sampling period was 8.0 ± 17.7 mm/day (https://meteostat.net/en/station/47684?t=2021-03-23/2021-08-22). Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by at least one SARS-CoV-2 assay in the combined (39 %, 9/23) and separated sewer line samples (52 %, 12/23) although rainfall events occurred during several sampling occasions. This result indicated that the effect of precipitation on the virus detection from the combined sewer line samples was negligible. However, the effect could be different in other countries where precipitation events can be different. When SARS-CoV-2 was tested by only one assay, the positive ratio was as low as 13 % each in the combined and separated sewer lines. Thus, the application of more than one assay or at least two assays (CDC N1 and CDC N2) is recommended for the effective detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, N501Y and S69-70 del, were detected in the December 2020 sample in the quarantine facility (Table 2). In the same month, the detection of UK variant (now termed as Alpha variant) was reported in clinical samples in Japan (Nikkei Asia, 2020). However, in the WWTP samples, these RNA were detected in two samples collected in May 2021, and one sample was positive for both, indicating that HT-qPCR can be successfully applied to monitoring of variants of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. This result was consistent with the fact that the Alpha variant was prevalent in Mie Prefecture in May 2021 (Mie Prefectural Government, 2021). In addition, the sample collected on April 5, 2021 was positive for the E484K nucleotide substituted RNA (Beta and Gamma label) and L452R nucleotide substituted RNA (Delta and Kappa label). This showed that multiple variants were circulating in the community at that time. Delta variant was first reported in May 2021 in Mie Prefecture (YouYokkaichi, 2021). In line with the results of previous studies (de Araújo et al., 2022; La Rosa et al., 2021; Randazzo et al., 2020), the detection of Delta variant in the WWTP sample earlier than the first reported case in the Prefecture in the current study highlighted the use of wastewater monitoring as a potential early warning system. In August, all samples collected from the separated sewer line were positive for at least one SARS-CoV-2 assay. In addition, one sample collected on August 23 was positive for four SARS-CoV-2 nucleotides substituted RNA (E484Q, K417N, S69-70 del, and T19R). Interestingly, these results coincided with the increased COVID-19 cases in August which peaked in the fourth week in Mie Prefecture (Yokkaichi City Office, 2021) (Fig. 1).

In addition to the SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, pathogenic viruses were also successfully detected in the quarantine facility and the municipal WWTP samples by the HT-qPCR simultaneously. Of the total five pathogenic viruses tested, at least one pathogenic virus was detected in all the municipal WWTP samples, except for one separated sewer system WWTP sample in which none of the tested virus was detected. AiV-1 and NoV-GII were found to be more prevalent than other tested viruses in Mie Prefecture, while InfA was not prevalent. This study proved that HT-qPCR could be a potential technique to simultaneously detect not only SARS-CoV-2 and its variants but also the epidemiologically important pathogenic viruses to monitor community health. Thus, HT-qPCR could be a beneficial technique in the routine wastewater monitoring programs which are being rapidly implemented globally.

5. Conclusions

-

•

An efficient HT-qPCR technique was applied to simultaneously detect and quantify 22 target genes including SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, and other epidemiologically important pathogenic viral genes in a single run. Since this technique can be easily modified to include the combination of qPCR assays to be tested, it is possible to respond quickly even when a new mutant strain or pathogen appears, and it is expected to be used in future wastewater monitoring programs.

-

•

Two SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA, N501Y and S69-70 del, were detected in the samples of the quarantine facility in the same month when the Alpha variant was reported in clinical samples in Japan. Similarly, these nucleotide substituted RNA were detected in the two WWTP samples collected in May 2021 when the Alpha variant was prevalent in Mie Prefecture. In addition, E484K (Beta and Gamma label) and L452R (Delta and Kappa label) nucleotide substituted RNA were detected in the WWTP samples collected on April 5, 2021, whereas the Delta variant was first reported in May 2021 in Mie Prefecture. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide substituted RNA were detected in the quarantine facility and WWTP samples either in the same month or before the detection in clinical samples, indicating that HT-qPCR can be used for the initial screening of the variants as an early warning.

-

•

Unlike quarantine facility samples with high concentrations of target genes, samples with low concentrations of target genes, such as municipal WWTP samples, were not tested positive by all five SARS-CoV-2 assays, suggesting that the samples should be tested with more than one SARS-CoV-2 assays. For this, HT-qPCR will be a useful technique in which multiple assays can be included.

-

•

All samples collected in August 2021 from the separated sewer line were found positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by at least one SARS-CoV-2 assay, which coincided with the increased COVID-19 cases in Mie Prefecture. During that period, up to four out of nine nucleotide substitutions tested were detected in the same sample, suggesting that wastewater surveillance can be a useful tool for monitoring community health.

-

•

High prevalence of AiV-1 and NoV-GII, followed by EnV, NoV-GI, and InfA in the WWTP samples was identified, along with the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and nucleotide substitution-specific RNA, in a single run. This technique is useful for simultaneous monitoring of other diseases that are equally prevalent and transmissible in the community and thus should be included in the tool box of wastewater surveillance strategies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bikash Malla: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Ocean Thakali: Investigation. Sadhana Shrestha: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Takahiro Segawa: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Masaaki Kitajima: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Eiji Haramoto: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) through J-RAPID program (grant number JPMJJR2001) and e-ASIA Joint Research Program (grant number JPMJSC20E2), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (grant number JP20H02284). The authors would like to thank the anonymous quarantine facility for providing wastewater samples and relevant data. The authors acknowledge the laboratory members Niva Sthapit, Made Sandhyana Angga, Aulia F. Rahmani, Sunayana Raya, and Nana Frempong Manso (University of Yamanashi) for their support in the laboratory works and the staffs of the WWTPs for their support and permission on wastewater sampling.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., Brien J.W.O., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Smith W.J., Metcalfe S., Jackson G., Choi P.M., Morrison M., Field D., Gyawali P., Bivins A., Bibby K., Simpson S.L. Comparison of RT-qPCR and RT-dPCR platforms for the trace detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater. ACS ES&T Water. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.1c00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asia Nikkei. [WWW Document] URL. 2020. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Japan-reports-first-5-cases-of-UK-coronavirus-variant

- Bedotto M., Fournier P.E., Houhamdi L., Colson P., Raoult D. Implementation of an in-house real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay to detect the emerging SARS-CoV-2 N501Y variants. J. Clin. Virol. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabbes L., Ollivier J., Schaeffer J., Parnaudeau S., Rhaissi H., Nourlil J., Le Guyader F.S. Norovirus and other human enteric viruses in Moroccan shellfish. Food Environ. Virol. 2013;5(1):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s12560-012-9095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., North D., Ahmad A., Ahmed W., Alm E., Been F., Bhattacharya P., Bijlsma L., Boehm A.B., Brown J., Buttiglieri G., Calabro V., Carducci A., Castiglioni S., Gurol Z.C., Chakraborty S., Costa F., Curcio S., de los Reyes F.L., III, Vela J.D., Farkas K., Fernandex-Casi X., Gerba C., Gerrity D., Girones R., Gonzalez R., Haramoto E., Harris A., Holden P.A., Islam M.T., Jones D.L., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., Kitajima M., Kotlarz N., Kumar M., Kuroda K., La Rosa G., Malpei F., Mautus M., McLellan S.L., Medema G., Meschke J.S., Mueller J., Newton R.J., Nilsson D., Noble R.T., van Nuijs A., Peccia J., Perkins T.A., Pickering A.J., Rose J., Sanchez G., Smith A., Stadler L., Stauber C., Thomas K., van der Voorn T., Wigginton K., Zhu K., Bibby K. Wastewater-based epidemiology: global collaborative to maximize contributions in the 2 fight against COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:7754–7757. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-time rRT-PCR Diagnostic Panel.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T.Brünink, Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Haagmans B.L., Veer B., Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P.G., Drosten C., DGJC Mulders. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro. Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. pii=2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corporation Fluidigm. Gene expression preamplification with Fluidigm preamp master mix and Taqman assays. 2016. https://fluidigm.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#700000009DAw/a/4u0000019jvj/T.y.InnXR7M6pZKRvFsyl6ryYt5iNyO1LHRUY18FCos Retrieved on August 3, 2022.

- da Silva A.K., Le Saux J.C., Parnaudeau S., Pommepuy M., Elimelech M., Le Guyader F.S. Evaluation of removal of noroviruses during wastewater treatment, using real-time reverse transcription-PCR: different behaviors of genogroups I and II. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73(24):7891–7897. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01428-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo J.C., Mota V.T., Teodoro A., Leal C., Leroy D., Madeira C., Machado E.C., Dias M.F., Souza C.C., Coelho G., Bressani T. Long-term monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in sewage samples from specific public places and STPs to track COVID-19 spread and identify potential hotspots. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;838 doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.155959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassy J., Lacoux C., Leroy S., Noussair L., Hubac S., Degoutte A., Vassaux G., Leclercq V., Rouquie D., Marquette C.H., Rottman M., Touron P., Lemoine A., Herrmann J.L., Barbry P., Nahon J.L., Zaragosi L.E., Maril B. Versatile and flexible microfluidic qPCR test for high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 and cellular response detection in nasopharyngeal swab samples. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S.D., Cooper E.M., Calci K.R., Genthner F.J. Design and assessment of a real time reverse transcription-PCR method to genotype single-stranded RNA male-specific coliphages (Family Leviviridae) J. Virol. Methods. 2011;173:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron L., Verreault D., Veillette M., Moineau S., Duchaine C. Evaluation of filters for the sampling and quantification of RNA phage aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2010;44:893–901. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2010.501351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Kitajima M., Kishida N., Konno Y., Katayama H., Asami M., Akiba M. Occurrence of pepper mild mottle virus in drinking water sources in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79(23):7413–7418. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02354-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Kitajima M., Hata A., Torrey J.R., Masago Y., Sano D., Katayama H. A review on recent progress in the detection methods and prevalence of human enteric viruses in water. Water Res. 2018;135:168–186. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima K. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.04.20122747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S., Segawa T., Okabe S. Simultaneous quantification of multiple food- and waterborne pathogens by use of microfluidic quantitative PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79(9):2891–2898. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00205-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto R., Yamaguchi K., Arakawa C., Ando H., Haramoto E., Setsukinai K., Katayama K., Yamagishi T., Soranoh S., Murakami M., Kyuwa S., Kobayashi H., Okabe S., Imoto S., Kitajima M. The detectability and removal efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 in a large-scale septic tank of a COVID-19 quarantine facility in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jothikumar N., Kang G., Hill V.R. Broadly reactive TaqMan assay for real-time RT-PCR detection of rotavirus in clinical and environmental samples. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;155(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama T., Kojima S., Shinohara M., Uchida K., Fukushi S., Hoshino F.B., Takeda N., Katayama K. Broadly reactive and highly sensitive assay for Norwalk-like viruses based on real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003:1548–1557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1548-1557.2003. 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama H., Shimasaki A., Ohgaki S. Development of a virus concentration method and its application to detection of enterovirus and norwalk virus from coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:1033–1039. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1033-1039.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Hata A., Yamashita T., Haramoto E., Minagawa H., Katayama H. Development of a reverse transcription-quantitative PCR system for detection and genotyping of aichi viruses in clinical and environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:3952–3958. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Iker B.C., Pepper I.L., Gerba C.P. Relative abundance and treatment reduction of viruses during wastewater treatment processes — identification of potential viral indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;488–489:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Ahmed W., Bibby K., Carducci A., Gerba C.P., Hamilton K.A., Haramoto E., Rose J.B. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: state of the knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Brandtner D., Mancini P., Veneri C., Bonanno Ferraro G., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. Key SARS-CoV-2 mutations of alpha, gamma, and eta variants detected in urban wastewaters in Italy by long-read amplicon sequencing based on nanopore technology. Water. 2021;13(18):2503. doi: 10.3390/w13182503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.L., Gu X., Armas F., Chandra F., Chen H., Wu F., Leifels M., Xiao A., Chua F.J.D., Kwok G.W., Jolly S., Lim C.Y., Thompson J., Alm E.J. Quantitative SARS-CoV-2 tracking of variants Delta, Delta plus, Kappa and Beta in wastewater by allele-specific RT-qPCR. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.03.21261298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J.A., Pepper G., Naccache S.N., Huang M.L., Jerome K.R., Greninger A.L. Comparison of commercially available and laboratory-developed assays for in vitro detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(8) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00821-20. e00821-20. PMID: 32350048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mie Prefectural Government 2021. www.pref.mie.lg.jp/YAKUMUS/HP/m0068000066_00038.htm WWW Document.

- Nakauchi M., Yasui Y., Miyoshi T., Minagawa H., Tanaka T., Tashiro M., Kageyama T. One-step real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays for detecting and subtyping pandemic influenza A/H1N1 2009, seasonal influenza A/H1N1, and seasonal influenza A/H3N2 viruses. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;171(1):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office Yokkaichi City. 2021. https://www.city.yokkaichi.lg.jp.e.and.hp.transer.com/www/index.html WWW Document.

- Peterson S.W., Lidder R., Daigle J., Wonitowy Q., Dueck C., Nagasawa A., Mulvey M.R., Mangat C.S. RT-qPCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 mutations S 69–70 del, S N501Y and N D3L associated with variants of concern in Canadian wastewater samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;810 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Truchado P., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Simón P., Allende A., Sánchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/J.WATRES.2020.115942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh Y.S., Wait D., Tai L., Sobsey M.D. Methods to remove inhibitors in sewage and other fecal wastes for enterovirus detection by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods. 1995;54(1):51–66. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00025-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato K., Nao N., Katano H., Takayama I., Saito S., Kato F., Katoh H., Sakata M., Nakatsu Y., Mori Y., Kageyama T., Matsuyama S., Takeda M. Development of genetic diagnostic methods for novel coronavirus 2019 (nCoV-2019) in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;73(4):304–307. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysmex Corporation . Electronic Publication; 2022. Sysmex Obtains Manufacturing and Marketing Approval for Novel Coronavirus Detection Reagent (RT-PCR Method) - Building a Self-sufficient Production System in Japan for a Stable Supply of PCR Testing Kits. Retrieved on August 2, 2022.https://www.sysmex.co.jp/en/news/2021/pdf/210415.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tandukar S., Sthapit N., Thakali O., Malla B., Sherchan S.P., Shakya B.M., Shrestha L.P., Sherchand J.B., Joshi D.R., Lama B., Haramoto E. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater, river water, and hospital wastewater of Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;824 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongprachum A., Khamrin P., Maneekarn N., Hayakawa S., Ushijima H. Epidemiology of gastroenteritis viruses in Japan: prevalence, seasonality, and outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 2016;88(4):551–570. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Ahmed W., Oikarinen S., Sherchan S.P., Heikinheimo A., Jiang G., Simpson S.L., Greaves J., Bivins A. Application of digital PCR for public health-related water quality monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;837 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S., Oishi W., Zhu Y., Thakali O., Malla B., Yu Z., Zhao B., Arakawa, Kitajima M., Hata A., Ihara M., Kyuwa S., Sano D., Haramoto E., Katayama H. Comparison of five polyethylene glycol precipitation procedures for the RT-qPCR based recovery of murine hepatitis virus, bacteriophage phi6, and pepper mild mottle virus as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;807(2) doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Miller J.A., Verghese M., Sibai M., Solis D., Mfuh K.O., Jiang B., Iwai N., Mar M., Huang C., Yamamoto F., Sahoo M.K., Zehnder J., Pinsky B.A. Multiplex SARS-CoV-2 genotyping reverse transcriptase PCR for population-level variant screening and epidemiologic surveillance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021;59 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00859-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2021. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. [WWW Document]https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Gjorgjieva T., Attieh Z., Dieng M.M., Arnoux M., Khair M., Moussa Y., Al Jallaf F., Rahiman N., Jackson C.A. Microfluidic nano-scale qPCR enables ultra-sensitive and quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2. Processes. 2020;8:1425. doi: 10.3390/pr8111425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C., Ko K., Nagashima S., Harakawa T., Fujii T., Ohisa M., Katayama K., Takahashi K., Okamoto H., Tanaka J. Very low prevalence of anti-HAV in Japan: high potential for future outbreak. Sci. Rep. 2019;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37349-1. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YouYokkaichi 2021. https://www.you-yokkaichi.com/2021/05/26/13701/ [WWW Document]. URL.

- Zhang T., Breitbart M., Lee W.H., Run J.Q., Wei C.L., Soh S.W., Hibberd M.L., Liu E.T., Rohwer F., Ruan Y. RNA viral community in human feces: prevalence of plant pathogenic viruses. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(1):0108–0118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.