Abstract

Objectives

This study sought to assess the prevalence and factors associated with antenatal care (ANC) uptake among women in Papua New Guinea.

Study design

This is a secondary data analysis of a nationally representative population based cross-sectional survey of households in Papua New Guinea conducted from 2016 to 2018.

Methods

Descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and percentages and multinomial logistic regression analysis were done to assess the factors associated with ANC uptake and statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The prevalence of 4 or more ANC visits was 51.4%. The multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that women aged 35–39 [ARRR = 1.630, 95% CI = 1.016,2.615], those in the richest wealth quintile [2.361, 95% CI = 1.595,3.496], women who had secondary/higher level of education [ARRR = 3.644, 95% CI = 2.614,5.079], and those whose partners had secondary/higher education [ARRR = 1.706, 95% CI = 1.310,2.223] were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits. The likelihood of 4 or more ANC visits increased among women in Momase region [ARRR = 3.574, 95% CI = 2.683,4.762], those with parity 1 [ARRR = 2.065, 95% CI = 1.513,2.816], women who did not have a big problem with permission to go to the hospital for care [ARRR = 1.331, 95% CI = 1.110,1.597] and distance to health facility [ARRR = 1.970, 95% CI = 1.578,2.458]. However, women who were not working [ARRR = 0.756, 95% CI = 0.630,0.906], those in rural areas [ARRR = 0.712, 95% CI = 0.517,0.980] and those who do not take healthcare decisions alone [ARRR = 0.824, 95% CI = 0.683,0.994] were less likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits.

Conclusion

It was found that 51.4% of women have attained 4 or more ANC visits. Age, wealth status, employment, maternal and partner’s education, region and place of residence, parity, exposure to mass media, problem with distance and getting money needed for treatment and decision making on healthcare are associated with 4 or more ANC uptake among women in Papua New Guinea. To promote optimal number of ANC visits, there is the need for a multi-sectorial collaboration. For example, the various ministries such as the Ministry of Labour/Employment, Education, Development, Women affairs and Finance could collaborate with the Ministry of Health to achieve universal ANC coverage.

Keywords: Antenatal care, Pregnant women, Utilisation, Papua New Guinea, Public health

1. Introduction

Maternal mortality is a major public health concern worldwide [1] as stipulated in Sustainable Development Goal 3.1. One of the ways to reduce maternal mortality is to provide antenatal care services to women during pregnancy [2]. Antenatal care (ANC) attendance is described by Gebresilassie et al. [3] as pregnant women visiting antenatal clinics to receive care from health professionals. At this period, medical professionals usually assess the mother's and fetus's wellbeing. Pregnant women in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) should have at least four ANC visits according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. Nonetheless, this has been revised to at least 8 minimum visits in 2016 by the WHO due to the enormous benefits associated with its usage. The use of ANC is important for detecting pregnancy-related issues and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight, stillbirth, and intrauterine fetal death [[3], [4], [5]].

Pregnancy and childbirth-related complications claim the lives of approximately 830 women every day and more than 303,000 every year [1]. According to these figures, the majority of the cases (99%) occur in LMICs [1,6]. Papua New Guinea has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in Asia Pacific [7,8], with obstetric haemorrhage, sepsis, embolism, eclampsia, and unsafe abortion being the leading causes of death [7]. The uptake of ANC services can help predict some of the complications that contribute to high maternal mortality. Despite this, many women in LMICs do not pursue ANC at all or do so late [3,9], with a global prevalence of 58.6% (48.1% in developing regions and 84.8% in developed regions, as well as 81.9% in high-income countries and 24.0% in low-income countries) [10].

Studies have shown that several factors are associated with ANC attendance. These factors include age [5,11,12], wealth status [5,13], work or employment [11,14], level of education of women and their partners [3,5,12,13,15], marital status [11], place and region of residence [15], parity [16], pregnancy intentions [3,[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]], sex of household head, exposure to mass media [17], decision maker on healthcare, permission before seeking healthcare, money needed to seek healthcare and distance to health facility [16]. Despite this evidence, to the best of my knowledge, none of such studies has been conducted in Papua New Guinea using nationally representative dataset to determine the prevalence and assess the factors associated with the uptake of ANC services. Findings from such a nationwide study will be of outmost importance since it could help identify specific women to target to scale up the utilization of ANC services which will go a long way to reduce maternal mortality in Papua New Guinea and help in the attainment of SDG 3.1.

1.1. Conceptual framework

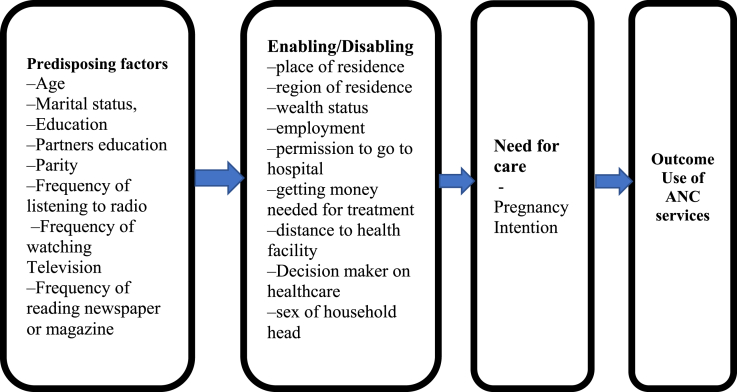

To study the usage of ANC services, this study used Andersen's healthcare utilization model as its conceptual framework (Fig. 1). Three key variables are interconnected according to the model as drivers of health-care use [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. These are predisposing, enabling, and need for care factors. In the first place, the predisposing factors are characteristics that have an impact prior to the occurrence of a specific health behaviour, such as promoting or inhibiting ANC attendance. All characteristics that might condition an individual's perceptions of need and use of ANC services are referred to as predisposing factors [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. Demographic characteristics such as age, marital status, parity, religion, and education are examples of predisposing factors [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. Second, enabling factors include financial status, community resources, and other factors that promote or hinder the use of health services. Third, according to Andersen's model, the "Need" for care is critical in shaping actions [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. In addition to an extensive review of scientific literature [3,5,[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]], Andersen's model was used as a guide to identify possible factors related to ANC service uptake. The explanatory variables in the study were grouped into predisposing factors (age, marital status, education, partners education, parity, frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching Television, frequency of reading newspaper or magazine), enabling factors (place of residence, region of residence, wealth status, employment, permission to go to hospital, getting money needed for treatment, decision maker on healthcare, distance to health facility, sex of household head), and need for care (pregnancy intention) factors.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework adapted from Anderson and Newman (1973).

2. Methods

2.1. Data and sampling design

The study used data from the 2016–2018 Papua New Guinea Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS), which was collected from October 2016 to December 2018. The survey adopted a two-stage stratified sampling technique. Each province was stratified into urban and rural areas, yielding 43 sampling strata, with the exception of National Capital District, which has no rural areas. Samples of Census Units (CUs) were selected independently in each stratum in two stages. In the first stage, 800 CUs were selected with probability proportional to CU size, which is the number of residential households found in the CU during the 2011 National Population and Housing Census (NPHC). Some of the selected clusters were large, with more than 200 households. To minimise the task of the listing team, these selected clusters were segmented. Only one segment was selected for the survey, with probability proportional to segment size. Household listing was conducted only in the selected segment. This means that a cluster is either a CU or a segment of a CU. In the second stage of selection, a fixed number of 24 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing, resulting in a total sample size of approximately 19,200 households. All women aged 15–49 who were usual members of the selected households or who spent the night before the survey in the selected households were eligible for individual interview. A total of 17,505 households were selected for the sample, of which 16,754 were occupied and 16,021 were successfully interviewed (96% response rate). In the interviewed households, 18,175 women age 15–49 were identified for individual interviews but 15,198 women were reached (84% response rate). However, 5,208 women in unions (married or cohabiting) who had given birth 5 years prior to survey constituted the sample size for this study. Women who were not in unions, women who gave birth more than 5 years prior to the survey and those without information on the variables of interest were excluded from the study. Details of the methodology, pretesting, training of field workers, the sampling design and selection are available in the PDHS final report [22] which is also available online at: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr364-dhs-final-reports.cfm.

2.2. Derivation of study variables

2.2.1. Outcome variable

The outcome variable for this study was ANC attendance from skilled healthcare providers such as doctors, midwives, nurses (including trained community health workers), and trained village health volunteers [22]. It was derived from the question “How many times did you receive antenatal care during this pregnancy?” Since the WHO recommends a minimum of at least 4 ANC visits per pregnancy, the responses were recoded into no ANC visit = 0, 1–3 = 1, and 4 or more = 2 [4,22]. Although the minimum number of ANC visits has been increased to 8 in 2016, this data was collected at the time the policy had just begun. That is the reason why the previous categorisation was used in this paper.

2.2.2. Independent variables

Eighteen independent variables were considered in this study. They were chosen based on two reasons, thus, their availability in the dataset [22] and conclusion drawn on them to be associated with ANC attendance in previous studies [5,[12], [13], [14],17,23]. The variables comprised maternal age, wealth status, employment, education, partner’s education, marital status, place of residence, region of residence, parity, pregnancy intention, permission to go to hospital, getting money needed for treatment, distance to health facility, frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching Television, frequency of reading newspaper or magazine, and sex of household head. The coding of these variables have been described in Table 1. These variables were grouped based on the conceptual framework (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Variables description and coding.

| No | Variable | Description/Question | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | |||

| ANC attendance | How many times did you receive antenatal care during this pregnancy? |

0 = 0 1 = 1-3 2 = 4 or more |

|

| Explanatory/independent variables | |||

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Age | Age of respondent | 1 = 15-19 2 = 20-24 3 = 25-29 4 = 30-34 5 = 35-39 6 = 40-44 7 = 45-49 |

|

| Education | Education level | 0 = No formal education 1 = Primary 2 = Secondary/Higher |

|

| Partner's education | Educational level of partner | 0 = No formal education 1 = Primary 2 = Secondary/Higher |

|

| Marital status | What is your marital status | 1 = Married 2 = Cohabiting |

|

| Region | Region of residence | 1 = Southern 2 = Highlands 3 = Momase 4 = Islands |

|

| Parity | Number of pregnancies reaching viable gestational age | 1 = 1 2 = 2 3 = 3 4 = 4 and above |

|

| Enabling factors | |||

| Household Wealth Status | Household wealth quintile | 0 = Poorest 1 = Poorer 2 = Middle 3 = Richer 4 = Richest |

|

| Employment | What is your occupation | 1 = Working 2 = Not working |

|

| Permission to go to hospital | Getting permission to get medical advice or treatment | 1 = Big problem 2 = Not a big problem |

|

| money needed for treatment | Getting money needed for treatment | 1 = Big problem 2 = Not a big problem |

|

| Distance to health facility | Distance to health facility | 1 = Big problem 2 = Not a big problem |

|

| Decision maker on healthcare | Person who usually decides on respondent's health care | 1 = Not alone 2 = Respondent alone |

|

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | Do you read a newspaper or magazine at least once a week, less than once a week or not at all? | 1 = Not at all 2 = Less than once a week 3 = At least once a week |

|

| Frequency of watching television | Do you watch television at least once a week, less than once a week or not at all? |

1 = Not at all 2 = Less than once a week 3 = At least once a week |

|

| Frequency of listening to radio | Do you listen to the radio at least once a week, less than once a week or not at all? |

1 = Not at all 2 = Less than once a week 3 = At least once a week |

|

| Sex of household head | What is the sex of household head | 1 = Male 2 = Female |

|

| Need for care | |||

| Pregnancy intention | When you were pregnant with [Name of the child] was the pregnancy wanted?” | 1 = Planned (then) 2 = Mistimed (later) 3 = Unwanted (not at all) |

|

2.3. Statistical analyses

In this study, both descriptive, bivariate and multinomial logistic regression analysis were conducted. The descriptive analysis (frequencies and percentages) were used to describe the study sample. The bivariate analysis was conducted using Chi-square test [χ2] to assess the differentials in the prevalence of ANC attendance across all the independent variables. All the variables that appeared statistically significant (p<0.05) were moved to the multinomial logistic regression analysis stage. Multinomial logistic regression model was employed because the dependent variable had three outcomes (No ANC attendance, 1–3 and 4 or more times). The results for the multinomial logistic regression analyses were presented as adjusted relative risk ratios (ARRR) along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) signifying precision. The multinomial logistic regression analysis also made it clear the factors associated with either partial attendance or optimal attendance using no attendance as a base category. Using the variance inflation factor (VIF), a multicollinearity test was carried out and the results showed no evidence of collinearity among the independent variables (Mean VIF = 1.4, Max VIF = 1.72, Minimum = 1.01). The sample weight (wt) was used to account for the complex survey (svy) design and generalizability of the findings. All the analyses were done with Stata version 14.2 for MacOS. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ (STROBE) statement was followed in conducting this study and writing the manuscript.

2.4. Ethical issues

The 2016–2018 PDHS report indicated that ethical approval was granted by the ICF Institutional Review Board. Both written and verbal informed consent were also sought from all the participants during the data collection exercise. The data were requested on the 10th March 2020. The dataset can be accessed freely at https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Papua-New-Guinea_Standard-DHS_2017.cfm?flag=0.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics and prevalence of ANC uptake

Table 2 presents the prevalence of ANC attendance among women in Papua New Guinea. It was found that 51.4% of women who delivered 5 years prior to the survey had 4 or more ANC visits. Table 2 also shows the background characteristics of the women. It was found that 26.9% were aged 25–29. Approximately 21.4% were in the poorest wealth category and 66.8% were not working. Less than half (48.8%) had primary level of education and the majority (82.3%) were married. The majority (89.2%) were also in rural areas while 40.1% had 4 or more children. The results further showed that 57.8% of the women aged 15–19 had 4 or more ANC visits. It was also found that 68.4% of the richest, 58.8% of those working, 69.3% of those with secondary or higher level of education and 52% of those who were married had 4 or more ANC visits. The chi-square analysis showed that all the independent variables had statistically significant association with ANC uptake at p<0.05 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics and prevalence of ANC uptake among women (N = 5208).

| Variable χ2(df),p-value | Weighted n | Weighted % | ANC attendance |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (%) | 1-3 (%) | 4 or more(%) | |||

| Prevalence | 23.6 | 25.0 | 51.4 | ||

| Predisposing factors | |||||

| Age (χ2= 44 (12), p<0.001) | |||||

| 15–19 | 181 | 3.5 | 19.85 | 22.35 | 57.80 |

| 20–24 | 1,116 | 21.4 | 18.20 | 31.74 | 50.06 |

| 25–29 | 1,400 | 26.9 | 23.85 | 23.10 | 53.04 |

| 30–34 | 1,100 | 21.1 | 24.39 | 22.59 | 53.02 |

| 35–39 | 850 | 16.3 | 27.34 | 21.30 | 51.36 |

| 40–44 | 415 | 8.0 | 23.13 | 28.85 | 48.01 |

| 45–49 | 147 | 2.8 | 39.13 | 24.42 | 36.45 |

| Education (χ2= 713.2(5), p<0.001) | |||||

| No education | 1,356 | 26.0 | 46.84 | 23.43 | 29.73 |

| Primary | 2,541 | 48.8 | 20.38 | 25.83 | 53.80 |

| Secondary/Higher | 1,311 | 25.2 | 5.66 | 25.09 | 69.25 |

| Partner'sEducation (χ2=440(5), p<0.001) | |||||

| No education | 1,097 | 21.1 | 41.58 | 22.88 | 35.54 |

| Primary | 2,231 | 42.8 | 26.00 | 23.74 | 50.26 |

| Secondary/Higher | 1,880 | 36.1 | 10.16 | 27.78 | 62.06 |

| Marital status (χ2= 6.5(2), p=0.038) | |||||

| Married | 4,284 | 82.3 | 22.69 | 25.34 | 52.0 |

| Cohabiting | 924 | 17.7 | 27.61 | 23.52 | 48.87 |

| Parity (χ2= 106.9(6) p<0.001) | |||||

| 1 | 1,118 | 21.5 | 13.51 | 25.50 | 60.99 |

| 2 | 1,042 | 20.0 | 18.85 | 26.51 | 54.64 |

| 3 | 962 | 18.5 | 26.46 | 25.98 | 47.56 |

| 4+ | 2,087 | 40.1 | 29.96 | 23.58 | 46.47 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine (χ2= 418.4,p<0.001) | |||||

| Not at all | 3,487 | 67.0 | 31.38 | 25.12 | 43.50 |

| Less than once a week | 972 | 18.7 | 10.40 | 24.76 | 64.84 |

| At least once a week | 749 | 14.4 | 4.22 | 24.87 | 70.91 |

| Frequency of watching television (χ2=236.9(4), p<0.001) | |||||

| Not at all | 4,130 | 79.3 | 27.91 | 24.88 | 47.21 |

| Less than once a week | 457 | 8.8 | 10.34 | 24.32 | 65.34 |

| A t least once a week | 620 | 11.9 | 4.32 | 26.48 | 69.20 |

| Frequency of listening to radio (χ2= 241.5(4), p p<0.001) | |||||

| Not at all | 3,467 | 66.6 | 29.37 | 25.48 | 45.15 |

| Less than once a week | 939 | 18.0 | 13.85 | 22.77 | 63.38 |

| A t least once a week | 802 | 15.4 | 9.81 | 25.65 | 64.55 |

| Sex of household head (χ2= 25.6 (4), p<0.001) | |||||

| Male | 4,537 | 87.1 | 24.81 | 24.22 | 50.97 |

| Female | 671 | 12.9 | 15.12 | 30.40 | 54.48 |

| Enabling factors | |||||

| Permission to go to hospital (χ2= 147.5(2), p<0.001) | |||||

| Big problem | 1,750 | 33.6 | 34.06 | 25.39 | 40.56 |

| Not a big problem | 3,458 | 66.4 | 18.25 | 24.83 | 56.92 |

| Getting money needed for treatment (χ2= 246.4(2), p<0.001) | |||||

| Big problem | 3,363 | 64.6 | 30.12 | 25.08 | 44.80 |

| Not a big problem | 1,845 | 35.4 | 11.61 | 24.90 | 63.49 |

| Distance to health facility (χ2= 416.4(2), p<0.001) | |||||

| Big problem | 3,130 | 60.1 | 32.14 | 25.41 | 42.45 |

| Not a big problem | 2,078 | 39.9 | 10.65 | 24.42 | 64.93 |

| Decision maker on healthcare (χ2= 14.8(2),p=0.001) | |||||

| Not alone | 3,696 | 71.0 | 24.79 | 25.29 | 49.92 |

| Alone | 1,512 | 29.0 | 20.55 | 24.36 | 55.08 |

| Region (χ2= 278.8(6), p<0.001) | |||||

| Southern region | 1,007 | 19.3 | 16.42 | 21.49 | 62.09 |

| Highlands region | 1,992 | 38.2 | 26.67 | 26.20 | 47.13 |

| Momase region | 1,489 | 28.6 | 31.59 | 26.85 | 41.56 |

| Islands region | 720 | 13.8 | 8.34 | 22.92 | 68.74 |

| Residence (χ2= 229.5(2), p<0.001) | |||||

| Urban | 561 | 10.8 | 10.26 | 21.88 | 67.86 |

| Rural | 4,647 | 89.2 | 25.16 | 25.40 | 49.44 |

| Wealth (χ2= 678.1(8), p<0.001) | |||||

| Poorest | 1,115 | 21.4 | 45.06 | 23.26 | 31.69 |

| Poorer | 1,051 | 20.2 | 29.85 | 24.48 | 45.67 |

| Middle | 1,041 | 20.0 | 21.31 | 24.46 | 54.23 |

| Richer | 1,021 | 19.6 | 14.33 | 25.96 | 59.71 |

| Richest | 980 | 18.8 | 4.36 | 27.21 | 68.42 |

| Employment (χ2= 51.3(2), p<0.001) | |||||

| Not working | 3,476 | 66.8 | 26.28 | 25.87 | 47.85 |

| Working | 1,732 | 33.2 | 18.11 | 23.31 | 58.58 |

| Need for care | |||||

| Pregnancy intention (χ2= 17.9(4), p=0.001) | |||||

| Planned | 3,665 | 70.4 | 23.94 | 23.77 | 52.29 |

| Mistimed | 592 | 11.4 | 16.05 | 30.55 | 53.40 |

| Unwanted | 951 | 18.3 | 26.77 | 26.37 | 46.86 |

Source: 2016-18 PDHS.

3.2. Multinomial logistic regression analysis on ANC uptake among women in Papua New Guinea

Table 3, presents the results on the multinomial logistic regression analysis on ANC uptake among women in Papua New Guinea. With no ANC attendance as the base outcome, the results showed that women aged 35–39 were more likely [ARRR = 1.630, 95% CI = 1.016,2.615] to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared with those aged 45–49. Compared with those in the poorest wealth quintile, the likelihood of 4 or more ANC visits increased with wealth. Specifically, those in the richest wealth quintile had the highest likelihood [ARRR = 2.361, 95% CI = 1.595,3.496] of attaining 4 or more ANC visits. In terms of educational level, the study showed that women who had secondary/higher education [ARRR = 3.644,95% CI = 2.614,5.079] as well as their partners [ARRR = 1.706, 95% CI = 1.310,2.223] had the highest likelihood of attaining 4 or more ANC visits compared with those with no education as well as their partners. Compared with women in Momase region, women in all the other regions had higher likelihood of attaining 4 or more ANC visits, with those at Islands region having the highest likelihood [ARRR = 3.574, 95% CI = 2.683,4.762]. In terms of parity, compared with those with parity 3, those with parity 1 had the highest likelihood [ARRR = 2.065, 95% CI = 1.513,2.816] of attaining 4 or more ANC visits. Women who did not have a big problem with permission to go to the hospital for care [ARRR = 1.331, 95% CI = 1.110,1.597] and distance to health facility [ARRR = 1.970, 95% CI = 1.578,2.458] were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits. With employment, the study showed that women who were not working had lower likelihood of attaining 4 or more ANC visits [ARRR = 0.756, 95% CI = 0.630,0.906] compared with those who were working. Women in rural areas [ARRR = 0.712, 95% CI = 0.517,0.980] and those who do not take their healthcare decisions alone [ARRR = 0.824, 95% CI = 0.683,0.994] were less likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared with those in urban areas and those who take decisions on their healthcare alone (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis on ANC uptake among women in Papua New Guinea.

| Variable | Base outcome (No ANC attendance) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1–3 |

4 or more |

|

| ARRR (95%CI) | ARRR (95%CI) | |

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Age | ||

| 15–19 | 1.134[0.549,2.341] | 0.969[0.490,1.919] |

| 20–24 | 0.955[0.555,1.645] | 0.914[0.548,1.523] |

| 25–29 | 1.003[0.604,1.666] | 1.197[0.743,1.928] |

| 30–34 | 1.17[0.709,1.933] | 1.565[0.978,2.507] |

| 35–39 | 1.225[0.740,2.027] | 1.630*[1.016,2.615] |

| 40–44 | 1.441[0.835,2.489] | 1.609[0.962,2.692] |

| 45–49 | Ref | Ref |

| Educational level | ||

| No education | Ref | Ref |

| Primary | 1.713***[1.372,2.138] | 2.263***[1.847,2.774] |

| Secondary/Higher | 2.432***[1.695,3.491] | 3.644***[2.614,5.079] |

| Partner'sEducation | ||

| No education | Ref | Ref |

| Primary | 1.197[0.943,1.519] | 1.206[0.969,1.499] |

| Secondary/Higher | 1.563**[1.172,2.086] | 1.706***[1.310,2.223] |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 1.097[0.872,1.381] | 1.105[0.894,1.366] |

| Cohabiting | Ref | Ref |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 1.471* [1.056,2.049] | 2.065***[1.513,2.816] |

| 2 | 0.932[0.698,1.245] | 1.262[0.966,1.649] |

| 3 | Ref | Ref |

| 4+ | 0.740*[0.574,0.955] | 0.860[0.679,1.089] |

| Sex of household head | ||

| Male | 0.674**[0.507,0.897] | 0.933[0.709,1.229] |

| Female | Ref | Ref |

| Frequency of reading newspaper/magazine | ||

| Not at all | 0.553**[0.358,0.853] | 0.619*[0.411,0.932] |

| Less than once a week | 0.667[0.416,1.068] | 0.836[0.536,1.304] |

| At least once a week | Ref | Ref |

| Frequency of watching television | ||

| Not at all | 0.742[0.458,1.204] | 0.616*[0.391,0.971] |

| Less than once a week | 0.813[0.449,1.470] | 0.711[0.409,1.237] |

| At least once a week | Ref | Ref |

| Frequency of listening to radio | ||

| Not at all | 1.026[0.729,1.445] | 0.991[0.722,1.361] |

| Less than once a week | 1.024[0.678,1.548] | 1.289[0.881,1.885] |

| At least once a week | Ref | Ref |

| Enabling factors | ||

| Permission to go to hospital | ||

| Big problem | Ref | Ref |

| Not a big problem | 1.295*[1.062,1.578] | 1.331**[1.110,1.597] |

| Getting money needed for treatment | ||

| Big problem | Ref | Ref |

| Not a big problem | 1.014[0.791,1.298] | 1.126[0.898,1.411] |

| Distance to health facility | ||

| Big problem | Ref | Ref |

| Not a big problem | 1.382** [1.083,1.763] | 1.970***[1.578,2.458] |

| Decision maker on healthcare | ||

| Not alone | 0.936[0.763,1.148] | 0.824*[0.683,0.994] |

| Alone | Ref | Ref |

| Region of residence | ||

| Southern region | 1.277* [1.011,1.630] | 1.638***[1.312,2.046] |

| Highlands region | 1.473** [1.157,1.875] | 1.448** [1.157,1.812] |

| Momase region | Ref | Ref |

| Islands region | 2.317***[1.696,3.165] | 3.574***[2.683,4.762] |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 0.781[0.553,1.103] | 0.712* [0.517,0.980] |

| Wealth status | ||

| Poorest | Ref | Ref |

| Poorer | 1.187[0.919,1.535] | 1.472**[1.163,1.864] |

| Middle | 1.244[0.950,1.629] | 1.591***[1.243,2.036] |

| Richer | 1.666** [1.229,2.259] | 1.895***[1.431,2.511] |

| Richest | 1.781** [1.164,2.724] | 2.361***[1.595,3.496] |

| Employment | ||

| Not working | 0.775* [0.637,0.943] | 0.756** [0.630,0.906] |

| Working | Ref | Ref |

| Need for care | ||

| Pregnancyintention | ||

| Mistimed | Ref | Ref |

| Planned | 0.947[0.702,1.278] | 1.059[0.800,1.401] |

| Unwanted | 0.854[0.602,1.210] | 0.753[0.543,1.043] |

| N | 5208 | |

Source: 2016-18 PDHS.

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals [CIs] in square brackets.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ref = reference, ARRR = Adjusted Relative Risk Ratios.

4. Discussion

This study sought to assess the prevalence and determinants of ANC attendance among women in unions in Papua New Guinea. It was revealed that 51.4% of the women had attained at least 4 ANC visits whereas 23.6% did not go for ANC at all. This finding is similar to what was found in Pakistan (57.3%) [24]. The result in this current study, is however, lower than what was found in Ghana (89%) [25] and Cameroon (70%) [26]. The differences in the study findings could be explained by the differences in study settings, and the times the various studies were conducted [5,10].

It was also found that women aged 35–39 were more likely to have 4 or more ANC visits. This confirms previous studies in Rwanda [27], Tanzania [28] and Cameroon [26]. This finding can also be discussed within the context of the Anderson and Newman's healthcare utilisation model which shows that a person’s age can serve as a predisposing factor to healthcare accessibility [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. The resultsalso revealed that women with secondary/higher level of education and those whose partners also have secondary/higher education were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared with those who are not educated. This is consistent with previous studies in Nepal [29], Ethiopia [30] and elsewhere [31]. The probable explanation is that those who are highly educated know the importance associated with ANC uptake and might be able comprehend the health education they receive from the health providers.

In agreement with previous studies [32,33], women in the richest wealth quantile were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits. Another major finding in this study was that women who were not working were less likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared to women who were working. This is consistent with several empirical studies in various parts of the world such as Ghana [34], Nepal [35], Ethiopia [36,37] and Nigeria [38,39]. Okedo-Alex et al. [40], explained that employment has an association with income and education. For example, those who are highly educated tend to be employed and consequently earn income which could be used to take care of the direct and indirect cost associated with ANC uptake. This findings has also been elucidated by the healthcare utilisation model [18]. It explains that a person’s wealth and employment status can either serve as enabling or disabling factors in a person’s quest to seeking healthcare [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. It is, therefore, crucial to ensure women empowerment programmes and provision of employment opportunities to help women access adequate number of ANC visits [41].

Another major fining in this study was that women who made decisions alone on their healthcare were less likely to attain 4 ore more ANC visits. This is similar to previous findings [40,[42], [43], [44]]. It was also found that women with parity 1 were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared to those with parity three. This is in line with previous studies [[45], [46], [47]] which consistently indicate that high parity is associated with low uptake of antenatal care services. Probable explanation for this finding as reported by Dangal [48] is that successive pregnancies might carry lower risks for complications if the first pregnancy and birth were uncomplicated. Pallikadavath, Foss and Stones [49] have also indicated that women who do not experience any complication for a previous pregnancy might not see the need to seek early ANC during their current pregnancy. Pell et al. [50] are also of the view that high parity women who have had previous successful pregnancies might think they are well ‘experienced’ and might delay ANC initiation or uptake.

The study also found that variations in regions and place of residence exist in the likelihood of 4 or more ANC attendance. Specifically, women in the Islands region were more likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits compared to those in the Momase region. This is also consistent with previous studies [[51], [52], [53]]. Relatedly, women in rural areas were less likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits. This corroborates previous studies that have documented the effect of rural residence on ANC [40,54]. It is therefore, imperative to institute measures such as community-wide sensitisation on ANC, encouragement of women who do not take up the recommended number of ANC visits, provision of basic amenities, and redistribution of health services across regions taking into consideration the rural-urban disparities [40,55]. Access to mass media showed statistically significant influence on the number of ANC visits. Specifically women who were not exposed to the mass media were less likely to attain 4 or more ANC visits. Similar findings have been reported in Nepal [29,55], India [56], Bangladesh [57,58] and Uganda [59].The probable explanation is that exposure to mass media has the ability to increase ones’ health literacy, which has been identified as key determinant to healthcare utilization [60]. The regional variations, and access to mass media could all explain how enabling or disabling factors can influence an individuals access to healthcare services [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. In this current study, women living in resource deprived areas and those without access to mass media have less optimal ANC attendance.

4.1. Strength and limitations of the study

The study is fraught with limitations that demand acknowledging. First, the study design makes it impossible to draw causal interpretation on the findings obtained. Second, since the study demanded women to recall previous events, there is the possibility of social desirability and recall biases. Apart from these, the relatively large sample size and the use of nationally representative dataset could make the findings generalisable to women in their reproductive age in Papua New Guinea.

5. Conclusion

It was found that 51.4% of women have attained 4 or more ANC visits. Age, wealth status, employment, maternal and partner’s education, region and place of residence, parity, exposure to mass media, problem with distance and getting money needed for treatment and decision making on healthcare are associated with 4 or more ANC uptake among women in Papua New Guinea. To promote optimal number of ANC visits, there is the need for a multi-sectorial collaboration. For example, the various ministries such as the Ministry of Labour/Employment, Education, Development, Women affairs and Finance could collaborate with the Ministry of Health to achieve universal ANC coverage. Promotion of female education, the provision of loans and other economic empowerment initiatives are also necessary to help empower women in various aspects. There is also the need to improve sensitisation on the various mass media platforms on the importance of ANC attendance. This can serve as a behavioural change mechanism for women to take up ANC services to benefit from timely disease detection and treatment strategies, the use of iron and folate supplements for the treatment of anaemia, Intermittent Preventive Treatment for malaria in pregnancy, immunization against tetanus and Tuberculosis, and detection of Sexually Transmitted Infections including HIV and AIDs to prevent mother to child transmission as well as health education in general including appropriate nutrition and personal hygiene.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgment

The author(s) is grateful to measuredhs for granting him access to the data.

References

- 1.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank . 2015. United Nations: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sageer R., Kongnyuy E., Adebimpe W.O., Omosehin O., Ogunsola E.A., Sanni B. Causes and contributory factors of maternal mortality: evidence from maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in Ogun state, Southwest Nigeria. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019 Dec;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebresilassie B., Belete T., Tilahun W., Berhane B., Gebresilassie S. Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in public health institutions of Axum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2017: a mixed design study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2490-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva: 2018. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manyeh A.K., Amu A., Williams J., Gyapong M. Factors associated with the timing of antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2020 Dec 1;20(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieburg P. center for strategic and international studies; Washington, DC: 2012 Oct. Improving Maternal Mortality and Other Aspects of Women's Health. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbers G., Vogel J.P., Mola G., Bolgna J., Homer C.S. Maternal and newborn health indicators in Papua New Guinea–2008–2018. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2019 Jan 1;27(1):52–68. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1686199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams C. Maternal deaths and their impact on children in Papua New Guinea. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:405–407. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lincetto O., Mothebesoane-Anoh S., Gomez P., Munjanja S. 2006. Antenatal Care. Opportunities for Africa's Newborns: Practical Data, Policy and Programmatic Support for Newborn Care in Africa; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller A.B., Petzold M., Chou D., Say L. Early antenatal care visit: a systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013. The Lancet Global Health. 2017 Oct 1;5(10):e977–e983. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30325-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebonwu J., Mumbauer A., Uys M., Wainberg M.L., Medina-Marino A. Determinants of late antenatal care presentation in rural and peri-urban communities in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018 Mar 8;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolde F., Mulaw Z., Zena T., Biadgo B., Limenih M.A. Determinants of late initiation for antenatal care follow up: the case of northern Ethiopian pregnant women. BMC research notes. 2018 Dec 1;11(1):837. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paudel Y.R., Jha T., Mehata S. Timing of first antenatal care (ANC) and inequalities in early initiation of ANC in Nepal. Frontiers in public health. 2017 Sep 11;5:242. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolde H.F., Tsegaye A.T., Sisay M.M. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Zemen primary hospital, South Gondar, Ethiopia. Reproductive health. 2019 Dec 1;16(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewunetie A.A., Munea A.M., Meselu B.T., Simeneh M.M., Meteku B.T. DELAY on first antenatal care visit and its associated factors among pregnant women in public health facilities of Debre Markos town, North West Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2018 Dec 1;18(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1748-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alemu Y., Aragaw A. Early initiations of first antenatal care visit and associated factor among mothers who gave birth in the last six months preceding birth in Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda North West Ethiopia. Reproductive health. 2018 Dec 1;15(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0646-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geta M.B., Yallew W.W. Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2017:1–6. 2017 Jan 1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen R., Newman J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health Soc. 1973 Jan 1:95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen R.M., McCutcheon A., Aday L.A., Chiu G.Y., Bell R. Exploring dimensions of access to medical care. Health services research. 1983;18(1):49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dankwah E., Zeng W., Feng C., Kirychuk S., Farag M. The social determinants of health facility delivery in Ghana. Reproductive health. 2019 Dec;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0753-2. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Statistical Office (NSO) [Papua New Guinea] and ICF Papua New Guinea Demographic and Health Survey 2016-18. Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and Rockville. NSO and ICF; Maryland, USA: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebremeskel F., Dibaba Y., Admassu B. Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in arba minch town and arba minch District, Gamo Gofa Zone, south Ethiopia. J environ public health. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/971506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noh J.W., Kim Y.M., Lee L.J., Akram N., Shahid F., Kwon Y.D., Stekelenburg J. Factors associated with the use of antenatal care in Sindh province, Pakistan: a population-based study. PloS one. 2019 Apr 3;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adu J., Tenkorang E., Banchani E., Allison J., Mulay S. The effects of individual and community-level factors on maternal health outcomes in Ghana. PloS one. 2018 Nov 29;13(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anchang-Kimbi J.K., Achidi E.A., Apinjoh T.O., et al. Antenatal care visit attendance, intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) and malaria parasitaemia at delivery. Malar J. 2014;13:162. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rurangirwa A.A., Mogren I., Nyirazinyoye L., Ntaganira J., Krantz G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; a population based study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2017 Dec 1;17(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta S., Yamada G., Mpembeni R., Frumence G., Callaghan-Koru J.A., Stevenson R., Brandes N., Baqui A.H. Factors associated with four or more antenatal care visits and its decline among pregnant women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PloS one. 2014 Jul 18;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thapa NR. Factors Influencing the Use of Reproductive Health Services Among Young Women in Nepal: Analysis of the 2016 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bayou Y.T., Mashalla Y.S., Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. The adequacy of antenatal care services among slum residents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0930-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saad-Haddad G., DeJong J., Terreri N., et al. Patterns and determinants of antenatal care utilization: analysis of national survey data in seven countdown countries. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okedo-Alex I.N., Akamike I.C., Ezeanosike O.B., Uneke C.J. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2019 Oct 1;9(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fagbamigbe A.F., Idemudia E.S. Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria : policy implications Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria : policy implications. Health Care for Women International. 2016;38:17–37. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2016.1225743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banchani E., Tenkorang E.Y. Occupational types and antenatal care attendance among women in Ghana. Health care for women international. 2014 Sep 1;35(7–9):1040–1064. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.919581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandey S., Karki S. Socio-economic and demographic determinants of antenatal care services utilization in Central Nepal. I j of MCH and AIDS. 2014;2(2):212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ragasa N. Antenatal and postnatal care service utilization in southern Ethiopia: a population-based study. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:390–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Assefa E., Tadesse M. Factors related to the use of antenatal care services in Ethiopia: application of the zero-inflated negative binomial model. Women & health. 2017 Aug 9;57(7):804–821. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1222325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akinyemi J.O., Afolabi R.F., Awolude O.A. Patterns and determinants of dropout from maternity care continuum in Nigeria. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016 Dec 1;16(1):282. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ononokpono D.N. Maternal health care in Nigeria: do community factors moderate the effects of individual-level Education and Ethnic origin? African Population Studies. 2015 Apr 16;29(1):1554–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okedo-Alex I.N., Akamike I.C., Ezeanosike O.B., Uneke C.J. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2019 Oct 1;9(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salihu H.M., Myers J., August E.M. Pregnancy in the workplace. Occup Med. 2012;62:88–97. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gudayu T.W. Proportion and factors associated with late antenatal care Booking among pregnant mothers in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2015;19:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tekelab T., Chojenta C., Smith R., et al. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ononokpono D.N., Azfredrick E.C. Intimate partner violence and the utilization of maternal health care services in Nigeria. Health care for women international. 2014 Sep 1;35(7–9):973–989. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.924939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gitonga E. Determinants of focused antenatal care uptake among women in tharaka nithi county, Kenya. Advances in Public Health. 2017:1–4. 2017 Jan 1. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agus Y., Horiuchi S. Factors influencing the use of antenatal care in rural West Sumatra, Indonesia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012 Dec;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joshi C., Torvaldsen S., Hodgson R., Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dangal G. High-risk pregnancy. Internet J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;8(2):2. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pallikadavath S., Foss M., Stones R.W. Antenatal care: provision and inequality in rural north India. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pell C., Meñaca A., Were F., Afrah N.A., Chatio S., Manda-Taylor L., Hamel M.J., Hodgson A., Tagbor H., Kalilani L., Ouma P. Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PloS one. 2013 Jan 15;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nketiah‐Amponsah E., Senadza B., Arthur E. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in developing countries. African J Economic Manage Studies. 2013;4(1):58–73. doi: 10.1108/20400701311303159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Afulani P.A. Rural/urban and socioeconomic differentials in quality of antenatal care in Ghana. PloS one. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basha G.W. Factors affecting the utilization of a minimum of four antenatal care services in Ethiopia. Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2019 Aug 14:2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/5036783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tekelab T., Chojenta C., Smith R., et al. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Acharya D., Khanal V., Singh J.K., Adhikari M., Gautam S. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in Nepal. BMC research notes. 2015 Dec 1;8(1):345. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kulkarni M., Nimbalkar M. Influence of socio-demographic factors on the use of antenatal care. Ind J Preventive Soc Med. 2008;39(3):98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh D. Effect of mothers' exposure to electronic mass media on knowledge and use of prenatal care services: a comparative analysis of Indian States. Prof Geogr. 2006;58(3):278–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9272.2006.00568.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Islam M.R., Odland J.O. 2011. Determinants of Antenatal and Postnatal Care Visits Among Indigenous People in Bangladesh: a Study of the Mru Community. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Edward B. Factors influencing the utilisation of antenatal care content in Uganda. Australas Med J. 2011;4(9):516. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collins J.H., Bowie D., Shannon G. A descriptive analysis of health practices, barriers to healthcare and the unmet need for cervical cancer screening in the Lower Napo River region of the Peruvian Amazon. Women's Health. 2019 Dec;15 doi: 10.1177/1745506519890969. 1745506519890969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]