Abstract

Escherichia coli adapted to glucose-limited chemostats contained mutations in ptsG resulting in V12G, V12F, and G13C substitutions in glucose-specific enzyme II (EIIGlc) and resulting in increased transport of glucose and methyl-α-glucoside. The mutations also resulted in faster growth on mannose and glucosamine in a PtsG-dependent manner. By use of enhanced growth on glucosamine for selection, four further sites were identified where substitutions caused broadened substrate specificity (G176D, A288V, G320S, and P384R). The altered amino acids include residues previously identified as changing the uptake of ribose, fructose, and mannitol. The mutations belonged to two classes. First, at two sites, changes affected transmembrane residues (A288V and G320S), probably altering sugar selectivity directly. More remarkably, the five other specificity mutations affected residues unlikely to be in transmembrane segments and were additionally associated with increased ptsG transcription in the absence of glucose. Increased expression of wild-type EIIGlc was not by itself sufficient for growth with other sugars. A model is proposed in which the protein conformation determining sugar accessibility is linked to transcriptional signal transduction in EIIGlc. The conformation of EIIGlc elicited by either glucose transport in the wild-type protein or permanently altered conformation in the second category of mutants results in altered signal transduction and interaction with a regulator, probably Mlc, controlling the transcription of pts genes.

The phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent glucose phosphotransferase system (PTS) is a complex of proteins mediating transport, phosphorylation, and sensing of glucose by Escherichia coli (27). Recognition of glucose by the PTS has major regulatory consequences, in controlling cyclic AMP levels (23) and in excluding other inducer molecules (18, 29). The glucose transporter has also been postulated to act as a signal transduction system in the transcriptional control of ptsHI gene expression (9).

The glucose-specific enzyme II (EIIGlc) component of E. coli consists of three domains, termed IIA, IIB, and IIC (15, 27). The IIA domain is a separate cytoplasmic protein, while the hydrophilic IIB domain is fused to the nonpolar, transmembrane IIC domain. The fused domains of the IICBGlc protein encoded by the ptsG gene confers sugar specificity and mediates the transport of glucose, the analogue methyl-α-glucoside (MG) and, to a lesser extent, mannose and another analogue, 2-deoxyglucose (7, 11). The EIIMan complex encoded by the manXYZ system has overlapping hexose specificity and transports mannose and 2-deoxyglucose and, to a lesser extent, glucose, fructose, glucosamine, and N-acetylglucosamine (7, 10, 24).

The determinants of substrate specificity in the PTS for sugars are poorly understood. Mutations altering the transport properties of IICBGlc are known, however. Some classes of ptsG mutations allow facilitated diffusion without glucose phosphorylation (28) or phosphorylation without transport (3). Selections forcing other sugars to use IICBGlc as a transporter resulted in ptsG mutants with increased transport of mannitol (1) or ribose (22). Most recently, V12G and V12F substitutions resulting in improved glucose transport at low substrate concentrations were identified (16). All of the above mutations affect the IIC domain, reinforcing the notion that the N-terminal domain controls transport specificity.

Recent findings further implicate IICBGlc in transcriptional regulation. Several pts genes, including ptsG, are induced by growth on glucose, and the repressor protein Mlc is involved in regulation by glucose (13, 25, 26). Mlc has no cognate inducer molecule, and it has been suggested that Mlc interacts with IICBGlc conditionally in the presence of glucose to relieve the repression of ptsG as well as other pts genes (26). This kind of mechanism is consistent with the signal transduction proposal made earlier to explain the involvement of IICBGlc in ptsHI regulation (9).

An altered interaction of Mlc with IICBGlc could result from one or both of two possibilities. First, the presence of a substrate could reduce the level of phosphorylation of the IIB domain due to phosphate transfer to the substrate. The second possibility is that substrate binding elicits a conformational change akin to a signal transduction effect found in proteins such as Tar, which changes a cytoplasmic interaction (2). As evidence for the latter possibility, we report an unexpected property of recently described V12 mutations (16). Mutations in ptsG that influence substrate affinity also affect transcriptional signal transduction. We describe other mutations with similar pleiotropic properties throughout the EIIBCGlc protein and explore an interesting correlation between relaxed substrate specificity and changes in transcriptional regulation.

The combined effects on transcription and sugar selectivity of the mutations described here are very reminiscent of the properties of a controversial umgC mutation described some years ago (12). The umgC mutation caused constitutiveness in ptsG, improved growth on glucosamine in the absence of the EIIMan system, and mapped close to ptsG. An understanding of the properties of this umgC mutation is now possible in light of the new selectivity mutations and is discussed below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All bacterial strains used in this study are derivatives of E. coli K-12 and are listed in Table 1. BW2952 was the strain from which ptsG mutants (with V12F, V12G, and G13C changes) were isolated in chemostats set up as described previously (16). All other ptsG mutants were obtained by selection on minimal glucosamine plates by the method of Jones-Mortimer and Kornberg (12). Briefly, strain BW3407 was grown in nutrient broth, centrifuged, and resuspended in basal minimal medium A (MMA). Approximately 108 bacteria were then spread onto a minimal glucosamine plate, and colonies appeared after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. The colonies were sequenced for changes in ptsG as described below. ptsG and mlc mutations were introduced into a ManXYZ− background by P1 transductional crosses (17) using P1 cml clr1000 grown on appropriate strains. ptsG mutations were transferred to a PtsG− ManXYZ− background (UE26) by selecting for cotransduction (80%) with zce-726::Tn10 and growth on minimal glucose plates. The mlc mutation (ΔC at P343) originated in a chemostat isolate, 15D5 (20, 21), and was transferred by P1 transduction to MC4100 using Tn10 (zde-3173::Tn10) inserted close to the mlc gene (75% cotransduction) to form BW3180. A P1 lysogen of this strain was then used to transduce a PtsG+ ManXYZ− strain (BW3214) to create BW3213 by selecting for tetracycline resistance and increased sensitivity to the glucose analogue MG (20, 21).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source, reference, or constructiona |

|---|---|---|

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 deoC1 relA1 thiA ptsF25 flbB5301 rbsR | 5 |

| BW2952 | MC4100 Φ(malG-lacZ+) | 19 |

| 15D5 | BW2952 mlc + other mutations | Chemostat isolate (20, 21) |

| UE26 | ptsG2 ptsM1 glk7 rpsL | W. Boos |

| BW3180 | MC4100 mlc zde-3173::Tn10 | P1 (15D5 Tcr) × MC4100 = Tcr MGs |

| BW3213 | BW3214 mlc zde-3173::Tn10 | P1 (BW3180) × BW3214 = Tcr MGs |

| BW3214 | UE26 ptsG+ | P1 (MC4100) × UE26 = Glc+ MGs |

| BW3224 | BW3407 ptsG(P384R) | This study |

| BW3256 | UE26 ptsG(G13C) | This study |

| BW3259 | BW3407 ptsG(G176D) | This study |

| BW3260 | BW3407 ptsG(A288V) | This study |

| BW3261 | BW3407 ptsG(G320S) | This study |

| BW3407 | UE26 ptsG+ zce-726::Tn10 | 16 |

| BW3406 | UE26 ptsG(V12F) zce-726::Tn10 | 16 |

| BW3408 | UE26 ptsG(V12G) zce-726::Tn10 | 16 |

MGs, MG sensitive.

Growth medium and culture conditions.

The basal salts medium used in all experiments was MMA (17) supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, glycerol, glucosamine, or mannose as specified for each experiment. Batch cultures were harvested during mid-exponential growth. ptsG mutants were isolated from chemostats set up as described previously (16). For determination of growth rates, overnight cultures were subcultured into 30 ml of MMA with an appropriate substrate (0.2%) and incubated at 37°C with good aeration. The absorbance of the cultures at an optical density at 580 nm was measured periodically, and the growth rate was determined. Antibiotics were added to the growth medium when required (chloramphenicol, 12.5 μg/ml; tetracycline, 15 μg/ml).

Transport studies.

The initial rate of uptake of 10 μM MG (d configuration; U-14C labeled) by glucose-grown bacteria was determined using bacteria resuspended in MMA to optical densities at 580 nm of 0.1 for mutant strains and 0.4 for control (wild-type ptsG) strains as described previously (8, 19). The rate of transport was calculated as picomoles of sugar transported per minute per 108 bacteria. Transport kinetics with glycerol-grown bacteria were measured in the same way. Fifty microliters of bacterial suspension was added to 50 μl of a solution containing six different MG concentrations ranging from 5 to 60 μM. The mean of three independent experimental rates at each concentration was plotted in a double-reciprocal plot with linear regression analysis using Origin 4.1 software. Inhibition of 10 μM MG transport was carried out with glucose-grown cells and d-ribose, d-glucosamine, or d-fructose at a concentration of 0.1 M; bacteria were added to a previously prepared mixture of substrate and inhibitor.

Mutation analysis.

PCR amplification of the ptsG and mlc genes, sequencing, and identification of mutations were done as previously described (16, 20, 21).

RNA extraction.

Total cellular RNA was extracted by the hot phenol method. Briefly, bacteria growing exponentially in minimal glycerol medium were harvested by rapid cooling to 0°C by the addition of crushed ice kept at −70°C, followed by centrifugation at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.6 ml of ice-cold buffer 1 (10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]). Immediately after resuspension, 0.5 ml of buffer 2 (0.4 M NaCl, 40 mM EDTA, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]) with 100 μl of water-saturated phenol, which had been kept in a tube at 70°C for 5 min, was added, and the solution was boiled for 40 s. The RNA was phenol extracted three times and ethanol precipitated before resuspension in water. The RNA was quantitated by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. Samples were run on a 1% agarose gel to check the equivalence of loadings and RNA integrity.

Total RNA (50 μg) was run on a 1.4% denaturing agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde before being blotted overnight at 4°C onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) as described previously (30). ptsG transcripts were detected with an oligonucleotide probe complementary to ptsG mRNA (5′-CCAGCGCGGATACGCCATCG-3′). To the 3′ end of the probe was added digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled dUTP using a DIG oligonucleotide tailing kit (Roche Diagnostics Australia Pty. Ltd.) and the recommended protocol. Prehybridization and hybridization reactions were carried out at 58°C. A DIG luminescent detection kit for nucleic acids (Roche Diagnostics Australia Pty. Ltd.) with the recommended protocol was used to detect DIG-labeled transcripts.

To measure mRNA decay rates, total cellular RNA was extracted as described above at intervals after transcription inhibition by rifampin (200 μg/ml), and each sample was processed as described above. Data from autoradiograms were quantitated by laser densitometry using a Molecular Dynamics SI personal densitometer.

RESULTS

Effect of ptsG mutations on specificity toward other sugars.

The chemostat-selected ptsG V12G and V12F mutations (16) were transferred to a strain mutated in manXYZ by P1 transduction to restrict analysis to ptsG effects and avoid hexoses being taken up by the EIIMan system with overlapping specificity. In addition to the V12 mutations previously described (16), another chemostat isolate with improved growth on limiting glucose and altered in G13C was also studied. The rate of growth of the mutants on a number of sugars was tested as shown in Table 2. The IICB-dependent growth of the mutant strains was significantly increased on mannose and glucosamine as substrates. The V12 and G13 mutations also significantly increased transport of the glucose analogue MG, as shown in Table 3. A more detailed kinetic analysis of MG uptake with glycerol-grown bacteria showed that the apparent Vmax increased and the Km decreased in the mutants, with the V12F mutant having the best affinity and the V12G mutant having the highest Vmax. These results indicated that changes at residues 12 and 13 broaden the substrate specificity and introduce changes to substrate recognition in IICBGlc.

TABLE 2.

Mean generation times for E. coli strains on different carbon sources

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | Generation time (h) onb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Mannose | Glucosamine | ||

| BW3407 | ptsG(WT) | 0.8 | 6.0 | >24 |

| BW3213 | ptsG(WT) mlc | 0.8 | 1.9 | 4.6 |

| BW3406 | ptsG(V12F) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.9 |

| BW3408 | ptsG(V12G) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| BW3256 | ptsG(G13C) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| BW3259 | ptsG(G176D) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| BW3260 | ptsG(A288V) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.4 |

| BW3261 | ptsG(G320S) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| BW3224 | ptsG(P384R) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 |

All strains carry a mutation in manXYZ. WT, wild type.

Carbon sources were supplied at 0.2%. Values are averages of at least three replicates.

TABLE 3.

Influence of ptsG mutations on the transport of MG, a IIBCGlc substrate

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | Rate of transport of 10 μM MG (pmol/min/108 bacteria)bc | Vmax for MG (pmol/min/108 bacteria)bd | Km for MG (μM)bd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW3407 | ptsG(WT) | 142 ± 37 | 0.3 | 51 |

| BW3213 | ptsG(WT) mlc | 133 ± 22 | 1.9 | 59 |

| BW3406 | ptsG(V12F) | 715 ± 55 | 1.0 | 9 |

| BW3408 | ptsG(V12G) | 624 ± 10 | 2.9 | 28 |

| BW3256 | ptsG(G13C) | 436 ± 55 | 1.0 | 32 |

| BW3259 | ptsG(G176D) | 567 ± 75 | 1.7 | 113 |

| BW3260 | ptsG(A288V) | 425 ± 5 | 1.3 | 55 |

| BW3261 | ptsG(G320S) | 571 ± 48 | 1.2 | 40 |

| BW3224 | ptsG(P384R) | 621 ± 25 | 1.2 | 26 |

All strains carry a mutation in manXYZ. WT, wild type.

Values are based on at least three replicates for each strain.

Bacteria were grown on glucose (0.2%).

Bacteria were grown on glycerol (0.2%).

Further mutations in ptsG affecting the transport of glucosamine.

The above results suggested that mutations with a similar phenotype should be obtained by plating of the manXYZ mutant on glucosamine, exactly the selection used to obtain the umgC mutants in an earlier study (12). Glucosamine plate selection for faster-growing isolates was hence repeated with four independent cultures. From each of the four independent plates, one or two fast-growing colonies were directly sequenced for changes in ptsG. The V12G mutation was indeed present in one of the plate isolates. More surprisingly, sequence changes in ptsG were also found to result in G176D, A288V, G320S, and P384R substitutions in other colonies.

The growth rates on glucosamine and mannose were enhanced in all ptsG mutants, as shown in Table 2. The uptake of MG increased and transport kinetics were also affected in all mutants, as shown in Table 3. All mutants exhibited an increased apparent Vmax but variously showed decreased, increased, or unaltered Km, consistent with altered structural properties of IICBGlc.

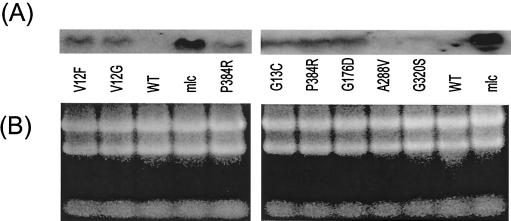

Regulatory changes in ptsG expression.

A characteristic feature of the original umgC mutation was the constitutive expression of ptsG (12). To check whether any or all of the isolates in Table 2 also showed altered ptsG expression, the RNA transcripts of the gene were blotted and probed as shown in Fig. 1. These experiments were undertaken with glycerol-grown bacteria in the absence of glucose to determine if basal, uninduced expression was elevated. Interestingly, ptsG expression was found to increase in all but two of the isolates (Fig. 1). The difference in the V12G, V12F, G13C, P384R, and G176D mutants was approximately the same in this and three other blots, and densitometer scans of the blots with equivalent loadings suggested a four- to fivefold increase in ptsG RNA levels above the level found with wild-type bacteria. This increase was not as high as the 20-fold increase in an mlc mutant derepressed for ptsG expression. Only the A288V and G320S mutants showed no change from wild-type transcript levels. The latter two mutants did show increased expression after growth on glucose (results not shown) and so were still glucose inducible. Clearly, there were two classes of mutations permitting growth on glucosamine, the two in transmembrane residues (288 and 320), without increased transcription, and the others, outside the transmembrane segments, with higher ptsG expression.

FIG. 1.

Expression of ptsG in E. coli mutants. (A) Northern blots of RNA extracted from glycerol-grown bacteria. (B) Ethidium bromide-stained samples showing control rRNA bands for the ptsG mutants and for an mlc mutant in two separate gels. All mutations were present in the BW3407 background shown in Table 1. Fifty micrograms of RNA was loaded in all lanes. WT, wild type.

To investigate whether the V12G and G13C effect was due to altered RNA stability in the mutants, the decay of the transcript was monitored over a 40-min period. There was no obvious difference in the decay patterns of the mutants and the wild type (results not shown), so that the increase in RNA levels in Fig. 1 was more likely to be due to increased transcription.

Is the change in transport in some mutants due to increased expression or altered specificity?

The expression data raised the possibility that the increased growth on nonglucose substrates and the increased Vmax of isolates after growth on glycerol were due to the presence of more IICBGlc protein rather than changes in specificity. To test whether increased ptsG transcription per se was responsible for these phenotypes, the transport and growth properties of the mlc strain with derepressed ptsG (Fig. 1) were investigated. Growth on glucosamine and mannose was faster for the mlc strain than for the wild type but slower than for any of the ptsG mutants. Hence, a high level of expression was not sufficient to explain the rates of growth of the mutants on glucosamine and indicates a structural difference in IICBGlc function in the isolates. The transport results shown in Table 3 also support this conclusion; after growth on glucose, an inducing substrate that reduces transcriptional differences in ptsG expression (25), there was little difference in transport between the wild type and the mlc mutant. However, all of the ptsG mutants had higher transport rates, consistent with a structural effect in each case. The altered apparent Kms for MG reinforce this conclusion. Likewise, the increased Vmaxs of the A288V and G320S mutants occurred without increased expression and so were due to a structural change.

Specificity of ptsG mutants toward glucosamine, ribose, and fructose.

An unexpected result from the glucosamine selections was that the isolate with the G176D mutation contained exactly the same change as ptsG mutants selected to grow on ribose (22); in addition, one change at G320 was in a residue altered in ptsG and resulting in increased transport of mannitol (1). However, another of the mutations, at residue 288, was in a transmembrane region containing three other ribose uptake mutations. Furthermore, the V12F mutation was also recently found to increase the transport of fructose, but without phosphorylation (14). This pleiotropic broadening of substrate specificity toward glucosamine, mannose, ribose, and fructose could be either an affinity change at the glucose binding site in IICBGlc or the result of an increasing flux of all of these sugars through a more open channel. An increase in affinity toward glucosamine, ribose, or fructose should be reflected in a measurable increase in competition for transport between sugars.

The transport properties of mutants toward glucosamine, ribose, and fructose were investigated using an assay involving competitive inhibition of MG transport. As expected, an mlc mutation did not change the transport inhibition properties, shown by the assays in Table 4. The transport of MG was also unaffected by ribose in any of the ptsG mutants, even with a 10,000-fold molar excess of sugar over the MG substrate. The effect of ribose on glucose transport was not tested by Oh et al. (22), who reported increased transport of nonphosphorylated ribose in the G176 mutant. Also, only one mutant (G13C) had a weakly increased affinity for fructose relative to the wild type. In contrast to ribose and fructose, glucosamine did have a slightly higher affinity for the IICBGlc protein in all of the mutants and did inhibit MG transport but still required a large molar excess for inhibition (Table 4). Given the high concentrations used, there is the possibility that a minor contamination of glucosamine by glucose could explain this low-level inhibition. Nevertheless, the simplest conclusion is that IICBGlc is altered in the mutants without a marked increase in affinity for other sugars.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition of MG transport

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | % Inhibition by a 0.1 M concn ofb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucosamine | Ribose | Fructose | ||

| BW3407 | ptsG(WT) | 34 | 36 | 30 |

| BW3213 | ptsG(WT) mlc | 25 | 30 | 25 |

| BW3406 | ptsG(V12F) | 60 | 30 | 32 |

| BW3408 | ptsG(V12G) | 58 | 21 | 29 |

| BW3256 | ptsG(G13C) | 63 | 35 | 50 |

| BW3259 | ptsG(G176D) | 62 | 31 | 24 |

| BW3260 | ptsG(A288V) | 63 | 24 | 33 |

| BW3261 | ptsG(G320S) | 61 | 20 | 24 |

| BW3224 | ptsG(P384R) | 62 | 36 | 20 |

All strains carry a mutation in manXYZ. WT, wild type.

MG was used at 10 μM in all assays. Values are averages of at least three replicates with glucose-grown bacteria.

DISCUSSION

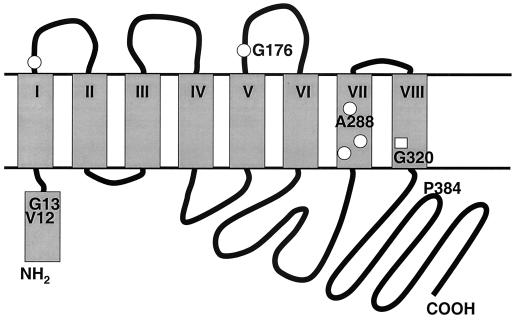

Improved growth on glucosamine via the ptsG-encoded transporter can be obtained with amino acid substitutions at many dispersed sites in the IICBGlc protein. The effect of the substitutions studied here needs to be interpreted in light of the positions of the amino acid changes causing relaxed substrate specificity and regulatory effects. The two-dimensional model of IICBGlc (4) is shown in Fig. 2 with the altered positions highlighted. The substitutions at residues 288 and 320 were located in transmembrane segments VII and VIII, and the others were scattered throughout external and internal segments. All mutations resulted in increased MG transport and growth on glucosamine, but only the changes at nontransmembrane residues affected ptsG transcription.

FIG. 2.

Model of the IICBGlc protein with sites of mutation superimposed. The model is based on the detailed structural analysis of Buhr and Erni (4). Proposed transmembrane segments are shaded and designated I to VIII. Also shaded is the α-helical segment on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. Open circles show the positions of ribose selectivity changes (22); the open square shows the position of the mannitol mutation (1). The positions of substitutions studied here are shown.

Previous reports of substitutions such as at G176, some in the seventh transmembrane segment (22), or at G320, resulting in increased transport of mannitol (1), were considered binding site changes selective for a particular sugar. There was indeed a small change of affinity for mannitol phosphorylation in the G320 mutant (1). For the mutants described here, we found little evidence for increased transport competition for alternate substrates, such as ribose, fructose, or even glucosamine utilized via IICB. Indeed, ribose and fructose cross IICBGlc without concomitant phosphorylation (14, 22). To unify these observations, a possible explanation is that the transport effect of the mutations is due to a wider or more open IICBGlc channel, leading to a relaxation of specificity for a range of substrates able to fit the altered channel. A wider channel could explain the absence of substrate phosphorylation for particular substrates but would result in increased permeation of the growth substrates reported here.

Two separate types of structural change can explain the different transcriptional effects of the substitutions. For transmembrane residues, changes are proposed to exert localized effects on the selectivity filter of the IICBGlc channel. In contrast, broadening of substrate specificity by amino acid changes on both sides of the membrane and in the C-terminal hydrophilic domain in Fig. 2 requires a slightly different explanation. The results obtained with the mutants tested are more consistent with long-range, conformational effects rather than the direct involvement of each of the mutated residues in hexose binding. This conclusion is particularly relevant to the substitution at P384 in the IIB-IIC hinge region (4).

An attractive feature of the proposed conformational change is that it links an open, substrate-relaxed conformation with signal transduction pathways. To explain the regulatory changes, the simplest notion is that the open conformation of the protein in the V12, G13, G176, and P384 mutants actually provides the signal for increased transcription. Signal transduction through binding of glucose to wild-type protein is presumably due to the same conformation. The V12, G13, G176, and P384 mutants are proposed to be permanently in this open conformation, to be more accessible to alternative substrates, and to have simultaneously altered signal transduction. The two transmembrane mutants still have the conformational change but require the binding of glucose, as they are still substrate inducible.

Our data do not reveal the partner of IICBGlc in signal transduction. However, the most likely possibility is an alteration in the site of interaction with Mlc (the transcriptional regulator). This notion is an extension of the idea that Mlc interacts with IICBGlc conditionally in the presence of glucose to relieve repression of ptsG as well as other pts genes (26). Further protein-protein analysis is required to reveal the nature of mutant interactions with Mlc and the additional role of phosphorylation of IIB (26) in the interaction with Mlc. Again, the properties of the P384 hinge mutation suggest the possibility that changes in the soluble, C-terminal region containing the IIB domain could feed back to change the channel structure.

The classic umgC mutation (12) has now been related to changes within ptsG (J. Plumbridge, personal communication; K. Jahreis and J. W. Lengeler, personal communication). The changes in substrate specificity and transcriptional regulation for the original umgC mutation can also be explained within the constraints of the proposed model.

The proposal involving simultaneous sensing and transport activities in PTS proteins is not unique to IICBGlc, and the regulation of bgl gene expression is well documented as involving the recognition of β-glucosides by an enzyme II system (6). It remains to be seen whether there are further similarities between IICBGlc and the nonhomologous IIBCABgl, organized in a different type of enzyme II complex.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Plumbridge, H. Kornberg, and K. Jahreis for open exchanges of unpublished information.

We thank the Australian Research Council for grant support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Begley G S, Warner K A, Arents J C, Postma P W, Jacobson G R. Isolation and characterization of a mutation that alters the substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli glucose permease. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:940–942. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.940-942.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair D F. How bacteria sense and swim. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:489–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhr A, Daniels G A, Erni B. The glucose transporter of Escherichia coli. Mutants with impaired translocation activity that retain phosphorylation activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3847–3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhr A, Erni B. Membrane topology of the glucose transporter of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11599–11603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casabadan M J. Transposition and fusion of the lac operon to selected promoters in E. coli using bacteriophage Lambda and Mu. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Q, Amster-Choder O. The different functions of BglF, the E. coli beta-glucoside permease and sensor of the bgl system, have different structural requirements. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17040–17047. doi: 10.1021/bi980067n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis S J, Epstein W. Phosphorylation of d-glucose in Escherichia coli mutants defective in glucose phosphotransferase, mannose phosphotransferase, and glucokinase. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:1189–1199. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.3.1189-1199.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Death A, Ferenci T. The importance of the binding-protein-dependent Mgl system to the transport of glucose in Escherichia coli growing on low sugar concentrations. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:529–537. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90002-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Reuse H, Danchin A. Positive regulation of the pts operon of Escherichia coli: genetic evidence for a signal transduction mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:727–733. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.727-733.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erni B, Zanolari B. The mannose-permease of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Gene cloning and purification of the enzyme IIMan/IIIMan complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15495–15503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson P J, Giddens R A, Jones-Mortimer M C. Transport of galactose, glucose and their molecular analogues by Escherichia coli K-12. Biochem J. 1977;162:309–320. doi: 10.1042/bj1620309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones-Mortimer M C, Kornberg H L. Amino-sugar transport systems of Escherichia coli K12. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;117:369–376. doi: 10.1099/00221287-117-2-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimata K, Inada T, Tagami H, Aiba H. A global repressor (Mlc) is involved in glucose induction of the ptsG gene encoding major glucose transporter in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1509–1519. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornberg H L, Lambourne L T, Sproul A A. Facilitated diffusion of fructose via the phosphoenolpyruvate/glucose phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1808–1812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lengeler J W, Jahreis K, Wehmeier U F. Enzymes II of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase systems: their structure and function in carbohydrate transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1188:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manché K, Notley-McRobb L, Ferenci T. Mutational adaptation of Escherichia coli to glucose limitation involves distinct evolutionary pathways in aerobic and oxygen-limited environments. Genetics. 1999;153:5–12. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson S O, Lengeler J W, Postma P W. Role of IIIGlc of the phosphoenolpyruvate-glucose phosphotransferase system in inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:360–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.360-364.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Notley L, Ferenci T. Differential expression of mal genes under cAMP and endogenous inducer control in nutrient stressed Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;160:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notley-McRobb L, Ferenci T. Adaptive mgl-regulatory mutations and genetic diversity evolving in glucose-limited Escherichia coli populations. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:33–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Notley-McRobb L, Ferenci T. The generation of multiple coexisting mal-regulatory mutations through polygenic evolution in glucose-limited populations of Escherichia coli. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:45–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh H, Park Y, Park C. A mutated PtsG, the glucose transporter, allows uptake of d-ribose. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14006–14011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterkofsky A, Gazdar C. Glucose inhibition of adenylate cyclase in intact cells of Escherichia coli B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:2324–2328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.6.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plumbridge J. Control of the expression of the manXYZ operon in Escherichia coli: Mlc is a negative regulator of the mannose PTS. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:369–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plumbridge J. Expression of ptsG, the gene for the major glucose PTS transporter in Escherichia coli, is repressed by Mlc and induced by growth on glucose. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1053–1063. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plumbridge J. Expression of the phosphotransferase system both mediates and is mediated by Mlc regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:260–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1149–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruijter G J, van Meurs G, Verwey M A, Postma P W, van Dam K. Analysis of mutations that uncouple transport from phosphorylation in enzyme IIGlc of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2843–2850. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2843-2850.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saier M H., Jr Protein phosphorylation and allosteric control of inducer exclusion and catabolite repression by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:109–120. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.109-120.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]