Abstract

The increased use of herbal medicines necessitates their quality and safety assurance. Among of other factors affecting herbal medicines is adulteration with conventional drugs that can potentially contribute to human health effects. This stimulate the high level of quality control that can be done by having strengthened analytical capacity. The present study developed a high throughput method for the determination of five (5) non-opioid analgesics namely acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen and diclofenac. A developed method was validated for its selectivity, sensitivity, linearity, accuracy, precision, recovery, matrix effects and stability. The results showed a good linear relationship with the concentration of the analytes over wide concentration ranges (0.001–10.00 µg/mL) with a coefficient of determination, R2 ≥ 0.9931. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for each compound were within the range of 0–3.7 µg/mL. The intra-precision of the method was expressed as relative standard deviation and was less than 9.5% with varying matrix effect from 68.56 to 138.88%. The absolute recoveries ranged from 59.63 to 107.10%. Among 132 collected samples, 21% were adulterated with caffeine and acetylsalicylic acid. The method developed met the ICH guidelines for detection and quantification of acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, diclofenac and ibuprofen in HM. Elimination of adulteration by introducing measures like setting education programmes for practitioners are recommended.

Keywords: Herbal medicines, Adulteration, Analgesics, Liquid chromatography, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

The rapid growth of the Herbal Medicines (HM) industry to cater for dietary supplements, cosmetics and medicines is experienced globally [21, 42]. Their increased use is ascribed to several factors including the management of the COVID 19 pandemic [24, 35], trust of the users, their availability, affordability and accessibility [21, 23, 42]. Despite the increased use of herbal medicines, their quality, safety and efficacy are still questionable [5]. Adulteration of HM with conventional drugs is among the factors affecting the safety of HM that may contribute to extrinsic adverse effects due to the failure of good manufacturing practices [2, 22, 27]. Adulteration of HM with sildenafil, tadalafil, sulfoaidenafil, sibutramine, phenolphthalein, chlorzoxazone, amoxicillin, ampicillin, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are reported globally (Ðy et al. 2014; [9, 15, 22, 37, 40], Lin et al. 2018). Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic drugs such as paracetamol, diclofenac, caffeine, ibuprofen, indomethacin, naproxen, and piroxicam have been reported as adulterants in HM in South Korea and China [16, 39]. Theses drugs are also reported in South Africa, Uganda and Kenya as common adulterants [3, 30, 44].

The World Health Organization (WHO) promotes safety, quality and efficacy of HM through her Traditional Medicine Strategies emphasizing the regulation of products, practices and practitioners [33]. The traditional Medicine Council of Tanzania regulates the HM safety and quality [26], however there is low capacity to monitor adulterants in HM. This needs analytical methods for screening and confirmatiom of adulterants in HM to be in place at the Tanzania Bureau Standards (TBS) and the Government of Chemistryr Laboratory Authority (GCLA) who are responsible to inform the traditional medicine Council. Different analytical techniques have been employed for screening of HM for quality check [13, 28, 43]. Analysis of adulterants have been achieved by chromatographic techniques such as such as Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC), High-performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography (GC) [5, 39].

These techniques are important at different levels to ensure the standards and quality of HM. A HPLC is considered to be simple, rapid, and inexpensive technique for preliminary screening of compounds but has low sensitivity and is applicable in a small number of samples or local health authorities [17, 29]. So far, some painkillers as adulterants have been determined in herbal products using an Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system. equipped with Xevo [16]. Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) is becoming the most popular analytical method of choice since it combines the separation capacity of LC with high sensitivity, resolution and selectivity of MS detector [36, 45].

Tanzania promotes high quality HM despite the existing limited information regarding the methods for detection of adulterants in HM and limited information on the levels and extent of adulteration. Due to these limitations, the country is striving towards attaining both high technology equipment and high skill human resources for setting benchmark methods for quality check of HM. The availability LC–MS/MS technology in Tanzania creates opportunity to set up specific analytical methods for detecting adulterants in HM. This study was conceived as one of the efforts in ensuring the safety of HM by developing a single high throughput LC–MS/MS method for the determination of acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen and diclofenac that are potentially used as adulterants in HM. Its availability will contribute in expanding the capability of doing routine detection of non-opioid analgesics in HM for quality check-up.

Materials and Methods

Solvents and Chemicals

Five (5) compounds of non-opioid analgesics including acetaminophen (99%), caffeine (98%), acetylsalicylic acid (99%), diclofenac ibuprofen (98%), sodium salt (98%), and internal standard (IS)—acetaminophen-d4 (99%) were bought from Sigma Aldrich (Fig. 1). For LC–MS/MS analysis, HPLC grade solvents including acetonitrile (MeCN, 99.9%), methanol (MeOH, 99.8%) and water (H2O) from Finar® Company were used. Also analytical grade formic acid (FA, 98%) from Finar® Company was used.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of the studied non-opioid analgesics

Operating Conditions for Mass Spectrometry

A Triple Quadrupole Mass spectrometry (Waters, Micromass UK Limited) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface operated with Masslynx 4.1 software was used. The MS detection was performed in both positive (+ ve) and negative (− ve) ion modes to capture the strongest ion. All compounds were first analysed individually in syringe infusion condition with a flow rate of 5µL/min. Optimization of parameters of the MS method was obtained by entering the molecular ion masses into the massLynx software. The default ranges for cone voltage and collision energy were used to enable MassLynx software to automatically determine all other parameters, such as capillary voltage, desolvation temperature, gas flows and Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) transitions. Nitrogen and argon gases were used as nebulizing and collision gases respectively. The ion source parameters were capillary 3.2 kV; exit potential 3 V; radio frequency (RF) lens 0.2 V; source temperature 110 °C; and desolvation temperature 400 °C. The desolvation and cone gas flow were 650 and 130 L/hr. Product ions and corresponding collision energies were stored in the method files. The two most intense MRM transitions were selected for quantification and qualification except ibuprofen, of which one precursor ion was observed because of the very low intensity of the second product ion.

Instrumentation and Optimization of HPLC Operation Conditions

A chromatographic separation was carried out on Agilent 1100 liquid chromatography system consisting of Degasser, G1379A; Binary pump, G1312A; Autosampler, G1313A; Column oven, G1316A; Diode array detector (DAD), G1315B; German. Separation was performed on a Kinetex® 2.6 µm, C18, 100 Å LC (75 × 2.1 mm) waters analytical column placed in column oven at 40 °C. MassyLynx software was used for data collection and handling.

The chromatographic conditions like the composition of mobile phase, flow rate, and column temperature played a critical role in achieving good chromatographic separation and appropriate ionization. Different mobile phase composition of solvents mixture including HPLC grade methanol, acetonitrile and water using different percentages of formic acid as a buffer at different flow rates ranging from 0.25 to 0.4 mL/min in three different column temperatures (30, 35, and 40 °C) were tested for better resolution of all compounds. The best conditions with good resolution were achieved for analysis, see Appendix 1. The mobile phase was composed of A (0.1% FA in 95% water) and B (0.1% FA in 5% acetonitrile) with linear gradient elution: 0–11.5 min, 5–5% B; 11.5–13.5 min, 95% B; 13.5–13.6 min, 5% B; the initial conditions were held for 6.4 min as a requilibration step. The injection volume was of sample 10 µL. Tthe effectiveness of the method was tested at higher, middle, and lower concentrations, i.e., 20.0, 2.0 and 0.2 µg/mL respectively.

Preparation of Standards

The stock solutions (1000 µg/mL) for acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, and diclofenac were prepared in 10 mL MeOH with 0.1% FA. Besides, the stock concentration of acetaminophen-d4, internal standard was prepared by dissolving 5.033 mg in MeOH with 0.1% FA to make a solution of 2516.50 µg/mL. These solutions were stored at − 20 °C before analysis. During the LC–MS/MS experiments, the working standard solutions of 20 µg/mL for each compound was diluted in dilution solvent (95:5 (water: MeCN v/v) with 0.1% FA in both).

Optimization of Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction

The Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) method was optimized for use in this study. Three parameters which are water bath temperature, type of organic solvent and sample to extraction solvent ratio were optimized sequentially. Each parameter was optimized at a time while the other parameters were kept constant. The effectiveness of the parameter was determined by its recovery. In each parameter optimization procedure, a liquid sample was subjected to three processes of sonication, centrifugation and evaporation as per [7] with slight modification. Where by a minimum of 3 mL of a sample was spiked with 5 µL of 25.165 µg/mL IS. The sample was then vortexed for 1, 6 mL of extraction solvent was added and the mixture was sonicated for 30 min. After sonication the mixture was vortexed for 1 min followed by centrifugation for 30 min at 4000 rpm. Six (6 mL) of supernatant was transferred to a clean culture tube, evaporated in a water bath to 1 mL. The residues were diluted with mobile phase to 2 mL, then 10 µL was injected into the LC–MS/MS. Using the explained procedure, four types of organic solvents were explored including pure MeCN, MeCN with 0.1% FA, pure MeOH, and MeOH with 0.1% FA. The tested sample to extraction solvent ratio were 5:0, 5:0.5, 5:2, 5:3, 5:5, and 5:7 and 5:10 (v/v, mL) while the tested water bath temperatures were 80, 83, 85, 90 and 100 °C.

Sampling of Liquid Herbal Medicines

A total of 132 liquid herbal medicines (HM) indicated for having analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory activities were purposively collected from herbalists, shops, clinics, and open markets in Dar es Salaam, Mwanza, Morogoro and Njombe regions. The regions were selected representing specific hot spots for the Traditional medicines markets in Tanzania.

Method Validation

The method validation for detecting adulterants in HM was done referring to the United State (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines on biological method validation [14]. The validation parameters included specificity, selectivity, linearity, precision, accuracy, matrix effects and recovery.

Evaluation of Specificity and Selectivity of the Method

The specificity of the method was evaluated by comparing complete separated chromatograms of matrix blanks (HM without standard mixture (STDs)) with spiked blank (STDs in dilution solvent) and a spiked matrix (HM with STDs mixture). Selectivity was evaluated by comparing the retention time of compounds in dilution solvent with those in the sample matrix as per International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines, to ensure no matrix components co-elutes with analytes [12]. The selectivity of the method was confirmed by calculating peak resolution of all compounds using Eq. (1); where tRA is the retention time for peak 1 and tRB is the retention time for the peak 2, W1 and W2 are full width for peak 1 and 2 respectively.

| 1 |

Determination of Recoveries from the Developed LC–MS/MS Method

The recoveries of five (5) analytes were calculated by comparing the mean area of prespiked samples (spiked before extraction) to that of post-spiked samples (spiked after extraction) in the same concentration. The recovery of IS was similarly estimated. Equations (2, 3) were used for recoveries experiments.

| 2 |

| 3 |

Determination of Matrix Effect

The matrix effect was determined by comparing the retention time (Rt) and the MS response (peak areas) of analyte and IS into sample matrix spiked before extraction with the peak areas of the same analyte and IS spiked into the dilution solvent having the same concentration of 1 µg/mL. The competition between analyte ions and matrix components leads to an effective decrease (ion suppression < 100%) or increase (enhancement > 100%) in the ionization process. The matrix effects was expressed by signal suppression/enhancement (SSE) [20], Eq. (4).

| 4 |

Determination of Precision and Accuracy

The intra-day precision of the method was determined by eight (8) replicates analysis at two concentrations (n = 8) of 0.1 and 1.0 µg/mL. It was expressed as relative standard deviation (%) of a series of eight (8) measurements [32]. Spike–and–recovery experiments were used in the determination of accuracy and recovery of the method. The accuracy of the method was determined by Eq. (5).

| 5 |

Preparation of Calibration Curve, LOD and LOQ of the Developed Method

The linearity of the method was investigated using dilution solvent spiked with different concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 10.0 µg/mL for acetylsalicylic acid, 0.003 to 10.0 µg/mL for caffeine and 0.01 to 10.0 µg/mL for acetaminophen, ibuprofen and diclofenac sodium salt. Linearity was determined by plotting the peak area ratio of the analytes to internal standard versus their relative concentrations’ ratio of the analytes to IS. The calibration curves were best fitted using a least-square linear regression model y = mx + b, in which y is the peak area ratio of the analyte to IS, m is the slope of the calibration curve, b is the y-axis intercept of the calibration curve and x is the analyte concentration. The unknown sample concentrations were calculated from the weighted least-squares regression analysis of the standard curves. The LOD and LOQ were calculated using the formula recommended by The ICH Guidelines [8], using Eqs. (6, 7) respectively.

| 6 |

| 7 |

Stability Test of Compounds

Stability of compounds was conducted to test their stability in working dilution solvent at different conditions. It was evaluated by preparing three (3) STDs in dilution solvent with an equal concentration of 20 µg/mL for each compound. The STDs was stored in different temperatures (at freezer, − 18 °C; fridge, 4 °C; and room temperature, 20 °C). The samples were analysed three (3) times within 4 weeks, after 3, 15 and 28 days. The stability was evaluated via peak areas using Eq. (8) [18]

| 8 |

where, S0 is the initial peak area, determined on the first day without introducing any extra pauses in the analysis process; St is the concentration obtained when analysis is carried out with making a pause with duration t in the analysis.

Analysis of HM

The presence of specific compounds was confirmed by comparing the retention times and fragments ion properties (quantifier and qualifier ions) of the sample from those of standards, Table 1.

Table 1.

Optimized MS parameters

| Compound | Ionization mode | Parent ion (m/z) | Product ions | Cone voltage (V) | Collision energy (V) | Retention time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | + | 151.87 |

64.40 109.70 |

20 20 |

30 19 |

1.84 |

| Acetaminophen-d4 | + | 155.92 |

96.2 113.8 |

26 26 |

21 17 |

1.84 |

| Caffeine | + | 195.04 |

82.50 137.80 |

22 22 |

27 18 |

4.67 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | − | 178.95 |

92.60 136.80 |

10 10 |

23 7 |

6.61 |

| Ibuprofen | − | 205.08 | 161.00 | 16 | 7 | 10.41 |

| Diclofenac sodium salt | − | 294.04 |

214.00 249.90 |

16 16 |

20 11 |

10.28 |

Results

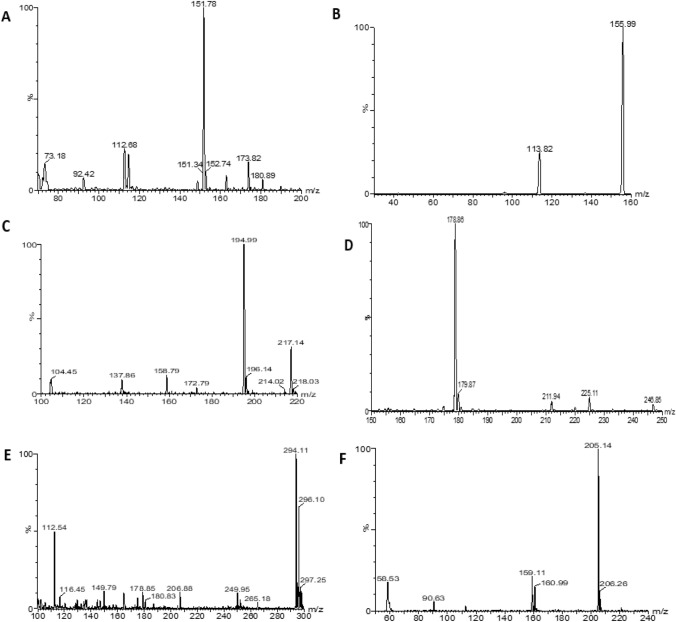

Optimized LC–MS/MS parameters

The results from ESI clearly illustrated that the compounds of interest were ionized in both positive and negative ion modes. ESI negative ion mode yielded the best sensitivity for ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid and diclofenac while acetaminophen and caffeine ionized in positive ion mode. The optimized MS/MS parameters were shown in Table 1. Reports were automatically generated specifying the optimized settings for the MRM method. The mass spectra of the compound of interest are shown in Appendix 2. The experimental information about the examined compounds with the fragment ions spectra along with cone voltages and collision energy values is shown in Table 1.

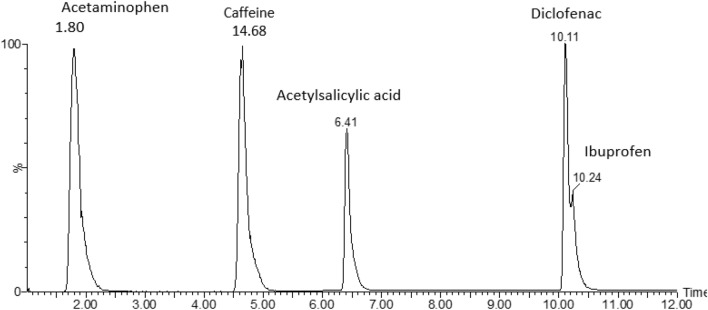

The LC analysis of the standard mixture shows that the positive ion mode compounds eluted first in the range of 0–6.0 min while the negative ion mode compounds eluted between 6 and 12 min. Figure 2 shows the overlaid chromatogram for separation of compounds. The method could analyse selectively studied compounds without interferences from any other compounds.

Fig. 2.

Representative overlaid chromatogram showing the separation of acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen and diclofenac

Optimized Sample Preparation Parameters

Optimized UAE Parameters for Extraction

The recoveries are at different temperatures as shown in Table 2. The high recovery of analytes were observed at the waterbath temperature of 85 °C and thus considered as the best water bath temperature. The Absolute recoveries of all compounds at this temperature were good except for ASA which had 55.1%. Recovery using MeCN with 0.1% FA was the highest (91.1–121.3%) and the best sample to extraction solvent ration was 2:1 (v/v) with recovery of 81.3–112.7% The overall absolute recoveries observed from sample preparation to analysis for the analytes ranged from 60 to 107%. These are acceptable recovery range as reported by other reseachres > 60% [1] as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Absolute and relative recoveries (%) for water bath temperatures

| Compound | Water bath temperature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 °C | 83 °C | 85 °C | 90 °C | 100 °C | |

| Acetaminophen | 101.7 | 106.8 | 103.9 | 102.6 | 94.9 |

| Acetaminophen-d4 | 99.9 | 98.8 | 98.2 | 92.1 | 101.3 |

| Caffeine | 105.8 | 97.3 | 91.4 | 100.3 | 91.9 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 11.1 | 22.8 | 55.1 | 30.7 | 21.6 |

| Ibuprofen | 110.5 | 96.9 | 90.9 | 99.3 | 65.9 |

| Diclofenac | 106.7 | 98.2 | 92.3 | 98.3 | 84.5 |

Table 3.

Absolute and relative recoveries (%) for the overall extraction procedures

| Compound | Entire sample preparation method | |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute, % | Relative, % | |

| Acetaminophen | 102 | 95 |

| Caffeine | 103 | 96 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 60 | 56 |

| Ibuprofen | 78 | 73 |

| Diclofenac sodium salt | 86 | 81 |

| Acetaminophen-d4 | 107 | 100 |

Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification

The Calibration curves were linear and the values of coefficient of determination (R2) ranged from 0.9931 to 0.9982. The LOD and LOQ show that all analysed compounds are detectable and quantifiable at the level of microgram per millilitre as shown in Table 3.

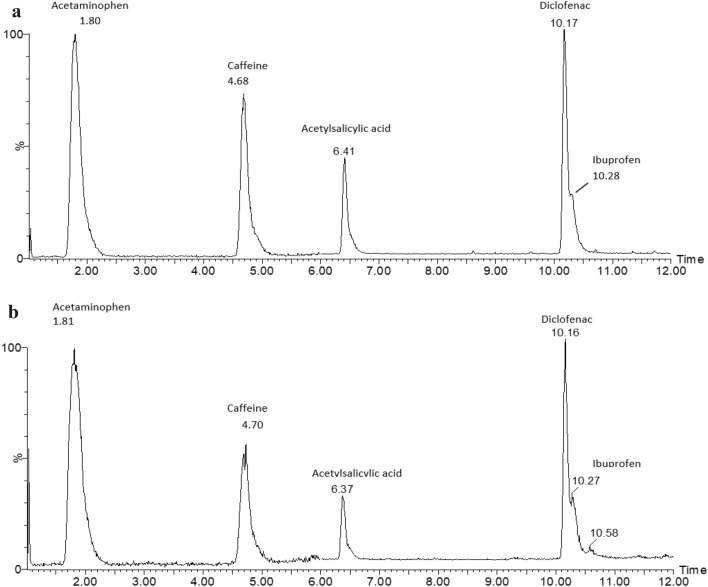

Specificity and Selectivity

The method shows good chromatographic specificity and selectivity. No interfering peaks were detected at the RT of all analytes in the matrix, Fig. 3a, b. Also, good peak resolution (Rs) were observed to acetaminophen, caffeine and acetylsalicylic acid which was > 2 as required by ICH and FDA [18] guidelines. Poor resolution of < 2 was obserserved for diclofenac sodium salt and ibuprofen.

Fig. 3.

a Overlaid chromatogram showing the separation of compounds in Dilution solvent, b representative overlaid chromatogram showing the separation of compounds in a sample matrix

Accuracy and Precision

The intra-day precision and accuracy of five (5) analytes ranged from 0.34 to 9.417% and 96.76 to 105.86% respectively. These accuracy and precision results were within acceptable criteria, showing that the developed method is reliable for quantification of five (5) analytes in HM, see Table 4.

Table 4.

The calibration equation, linearity (R2), precision (%RSD), LOD and LOQ

| Compound | Calibration equation | R2 | %RSD | Accuracy, % | LOD (µg/mL) | LOQ (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 µg/mL | 0.1 µg/mL | ||||||

| Acetaminophen | y = 1.0976x + 0.0141 | 0.998 | 7.30 | 3.896 | 100.27 | 0.1293 | 0.3919 |

| Caffeine | y = 1.1494x + 0.0288 | 0.997 | 3.87 | 2.142 | 103.11 | 0.1513 | 0.4584 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | y = 0.294x + 0.026 | 0.997 | 0.54 | 6.239 | 105.86 | 0.1203 | 0.3645 |

| Ibuprofen | y = 0.0793x + 0.0081 | 0.998 | 0.53 | 9.417 | 96.76 | 1.221 | 3.6998 |

| Diclofenac sodium salt | y = 0.7216x + 0.2011 | 0.993 | 0.34 | 3.633 | 104.82 | 0.1938 | 0.5872 |

Matrix Effects

The matrix effects ranged from 68.56 to 138.88%. Moderate signal enhancement was observed in acetylsalicylic acid with 118.96% while high signal enhancement was observed in acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and diclofenac with 138.88, 132.47, and 130.14% respectively. In contrast, higher signal suppression was observed in acetaminophen-d4 and caffeine with 68.56 and 69.28% respectively. Thus, the majority of the compounds are affected by signal enhancement (≤ 39%).

Stability Test of Analytes in Dilution Solvent

Figure 4 shows that, the stability of analytes was decreasing as the time increase for four (4) weeks. The rate of stability decrease was higher in sample stored at room temperature compared to those stored in the fridge (4 °C) and freezer (− 18 °C) respectively.

Fig. 4.

Stability test of all compounds at – 18, 4 and 20 °C for 3, 15 and 28 days

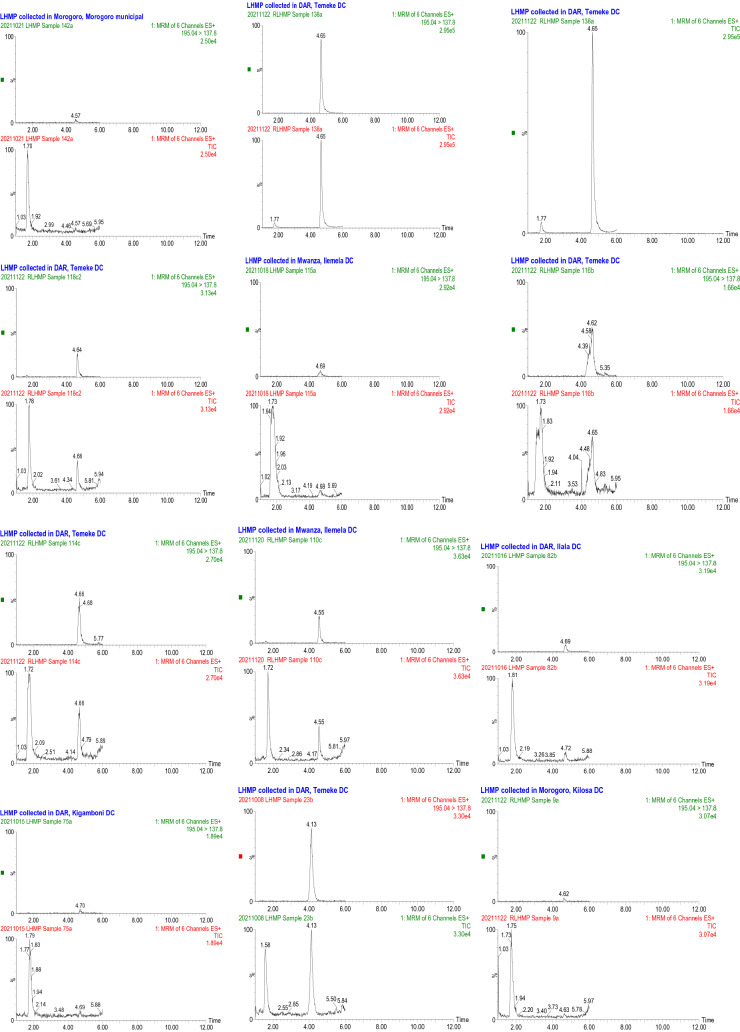

Detected adulterants in HM samples

Caffeine was detected in 26 samples equal to 20% of all analysed samples, acetylsalicylic acid in 1 sample equal to 1%. Table 5 shows the adulterated HM and their concentrations, where the negative concentrations means adulterants were detected but not quantifiable. Appendix 3 shows chromatograms of some adulterated samples.

Table 5.

Summary of adulterated LHMs

| S/No | Code | Adulterants | Conc. µg/mL | Demanded treatment | Source of sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HM 01 | Caffeine | − 0.1284 | Malaria and typhoid | Shop |

| 2 | HM 02 | Caffeine | 30.9708 | Coughing | Shop |

| 3 | HM 03 | Caffeine | 0.3679 | Coughing | Shop |

| 4 | HM 04 | Caffeine | 0.2325 | Coughing | Shop |

| 5 | HM 05 | Caffeine | − 0.0339 | Coughing | Shop |

| 6 | HM 06 | Caffeine | 0.5603 | Skin diseases | Shop |

| 7 | HM 07 | Caffeine | 0.4866 | UTI | Shop |

| 8 | HM 08 | Caffeine | 3.7453 | Skin diseases | Shop |

| 9 | HM 09 | Caffeine | 3.3471 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Street vendor |

| 10 | HM 10 | Caffeine | 0.2456 | Women reproductive problems | Shop |

| 11 | HM 11 | Caffeine | 0.0519 | Detoxification and anti-pain | Shop |

| 12 | HM 12 | Caffeine | 1.9256 | Ant pain | Shop |

| 13 | HM 13 | Caffeine | 3.1309 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Shop |

| 14 | HM 14 | Caffeine | − 0.9649 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Shop |

| 15 | HM 15 | Caffeine | − 0.2640 | Miscarriage | Shop |

| 16 | HM 16 | Caffeine | 1.3012 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Shop |

| 17 | HM 17 | Caffeine | 2.5814 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Shop |

| 18 | HM 18 | Caffeine | − 0.0861 | Anti-pains to organ | Street vendor |

| 19 | HM 19 | Acetylsalicylic acid | − 0.8443 | Coughing | Street vendor |

| 20 | HM 20 | Caffeine | 5.8062 | Coughing | Street vendor |

| 21 | HM 21 | Caffeine | 1.6904 | Skin diseases | Street vendor |

| 22 | HM 22 | Caffeine | 0.5993 | Teeth problems | Street vendor |

| 23 | HM 23 | Caffeine | 13.9241 | Anti-pains to organ | Street vendor |

| 24 | HM 24 | Caffeine | 3.7499 | Coughing | Street vendor |

| 25 | HM 25 | Caffeine | 0.7056 | Malaria ^ typhoid | Shop |

| 26 | HM 26 | Caffeine | 1029.22 | UTI | Shop |

| 27 | HM 27 | Caffeine | 0.2897 | UTI | Shop |

Discussion

This study report for the first-time combined methods for determination adulterants of acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, diclofenac and ibuprofen in liquid HM which allow for their quality check. The parameters optimised are well correlated with the ICH guideline [8]. The method run time was 20 min for analysis of five adulterants in a single run reducing the run time and solvents consumption. The good response, sharp peaks and short run time, and IS in chromatographic separation is important for efficient analysis [18]. The main fragments produced as a reference were comparable with other studies [4, 16]. The low recoveries of Acetylsalicylic acid have been reported by other scientists and are explained by its instability at room temperature [25]. The high sensitivity and selectivity demonstrated by this method qualify for screening of complex matrix [34].

The peak shape and resolution were the main criteria during the optimization of the LC method. The use of acetonitrile and water with 0.1% of FA, column temperature of 40 °C at 0.3 mL/min results to better separation and good peak shape compared to others, Appendix 1, Fig. 5a, b. In determining which compound is present in HM is accomplished by using precursor ions (both qualitative and quantitative ions) and retention time. The confidence level of identifying the targeted compounds in samples was configured as an error in retention time less than 0.5 min.

Fig. 5.

a Chromatograms at 30, 35, 40 °C Column temperature at 2.5 mL/min flow rate, b Chromatograms for 30, 35, 40 °C Column temperature at 0.3 mL/min flow rate

In the sample preparation procedure, acetonitrile with 0.1% FA in a ratio of 2:1 (extraction solvent to sample volume) was compatible with the mobile phase in the LC system used for analysis. A higher level of organic solvent was used for extraction because of high recoveries and low matrix effects. In the analysis of five compounds in HM, the standard mixture was used before, after, and in the middle of the batch analysis to check the consistency of the method. The shift of retention time ≤ 0.5 min was observed during a batch analysis that allow the use of replicates for the evaluation of results. Further, IS was added before sample extraction to compensate for matrix effects during measurements and random volume injections. The sensitivity of the instrument was stable throughout the analysis. Therefore, the specification of the developed LC–MS/MS method is suitable for qualitative and quantitative analysis of five compounds of interest in HM.

The reported quantifiable concentration range of up to 1029.22 µg/mL calls for the attention of the regulatory for quality and safety checks of these products. The presence of analytes as adulterants is reported in different parts of the world [5]. The Fact that HM analysed were adulterated with caffeine (20%) than other compounds can be attributed to the natural occurrence of caffeine on the other plants [38]. Caffeine can be found in leaves, seeds and fruits in many plants such as tea leaves, cocoa beans, coffee beans, guarana and kola nuts. Also, caffeine can be added to foods and drinks to promote energy and mood. It is reported that 240 mL of coffee contain 100 mg, green tea 30–50 mg, energy drinks 80 mg of caffeine while 100 g of guarana leaves contain 4.5 g of caffeine [10]. It was reported that the normal intake of caffeine per day should not exceed 400 mg for adults, < 200 mg for pregnant/lactating women and < 2.5 mg/kg per body weight for adolescents and children [41]. Thus, the use of caffeinated products plus such kind of adulterated herbal medicine can exceed the recommended dose and put the user at high risks. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reported that over-consumption of caffeine may lead to unwanted side effects including experiencing feelings of anxiety, hyperactivity, nervousness and sleep disturbance [6, 31]. Since consumers are unaware of adulterated HM, the risks of development of resistance, chronic diseases such as liver and other organ failures increase.

Caffeine can be added intentionally in skin care products because of its high biological activity and ability to penetrate the skin barriers characteristics [11] and its effectiveness in combination with other products [6]. The natural occurrence of caffeine in HM complicates its quantification, however, its presence at a higher level like the reported in this study may be caused by the intentional addition of synthetic caffeine [19].

Conclusion and Recommendation

The method developed met the ICH guidelines for detecton and quantification of acetaminophen, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, diclofenac and ibuprofen in HM. It is highly sensitive, accurate and time effective because it can analyse five compounds in one run. The information generated due to the method contribute to the country’s first report on existence of adulteration of HM with non-opioid analgesics. It is recommended that, the method be used for routine quality check to expand monitoring of HM to ensure their quality and safety to consumers and consequently propagate the market and its use. Moreover, training of products producers and handlers is very important to reduce the extent of adulteration. Studies on the development of analytical methods for screening other types adulterants in HM are also recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge great support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs through Danida Fellowship Center (DFC). The Green Resources Innovation for Livelihood Improvement (GRILI) project with DFC file number 18-3-TAN implemented by Sokoine University of Agriculture is also acknowledged.

Appendix 1

Reprentative chromatograms for optimization oc column temperature and flor rate.

See Fig. 5

Appendix 2

See Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

Representative MS scan spectra for acetaminophen (A), acetaminophen-d4 (B), caffeine (C), acetylsalicylic acid (D), diclofenac (E) and, ibuprofen (F)

Appendix 3

See Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Representative chromatograms showing the presence of Caffeine in HM

Author contributions

ALM Collected samples, collected data, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. CJM Technical assistance. FPM Conceived and designed the analysis. BS Conceived and designed the analysis.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest which could potentially influence this work.

Contributor Information

A. L. Mpanyakavili, Email: anna.mpanyakavili@sua.ac.tz, Email: mpanyaannah@gmail.com

C. J. Mwankuna, Email: cmwankuna@sua.ac.tz

F. P. Mabiki, Email: faith.mabiki@sua.ac.tz

B. Styrishave, Email: bjarne.styrishave@sund.ku.dk

References

- 1.Abarca RM. (2021) Improved Docking of Polypeptides with Glide. Nuevos Sistemas de Comunicación e Información, 2013–2015

- 2.Abdullah A. Title of the manuscript: a review on adulteration of raw materials used in ASU drug manufacturing. 2019 doi: 10.21276/sijtcm.2019.2.5.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abuga KO. 20 East and Central African journal of pharmaceutical sciences, Vol. 8. J Central African Vol Pharm Sci. 2005;8:20–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Lawati HAJ, Al Busaidi I, Kadavilpparampu AM, Suliman FO. Determination of common adulterants in herbal medicine and food samples using core-shell column coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr Sci. 2017;55(3):232–242. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmw175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calahan J, Howard D, Almalki AJ, Gupta MP, Calderón AI. Chemical adulterants in herbal medicinal products: a review. Planta Med. 2016;82(6):505–515. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-103495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cappelletti S, Piacentino D, Fineschi V, Frati P, Cipolloni L, Aromatario M. Caffeine-related deaths: manner of deaths and categories at risk. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):1–13. doi: 10.3390/nu10050611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Zhao L, Lu F, Yu Y, Chai Y, Wu Y. Determination of synthetic drugs used to adulterate botanical dietary supplements using QTRAP LC-MS/MS. Food Addit Contam—Part A Chem, Anal, Control, Expo Risk Assess. 2009;26(5):595–603. doi: 10.1080/02652030802641880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency. (2019) ICH Guideline M10 on Bioanalytical Method Validation Step 2B. Science Medicines Health, 44(March), 6/7-20/40-41/49-57. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-ich-guideline-m10-bioanalytical-method-validation-step-2b_en.pdf

- 9.Hachem R, Assemat G, Martins N, Balayssac S, Gilard V, Martino R, Malet-Martino M. Proton NMR for detection, identification and quantification of adulterants in 160 herbal food supplements marketed for weight loss. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;124:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healthline. (2021). 10 Foods and Drinks with Caffeine. In Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/foods-with-caffeine#The-bottom-line

- 11.Herman A, Herman AP. Caffeine’ s Mechanisms of Action and Its. 2013 doi: 10.1159/000343174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ICH. (2005) Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology Q2(R1)

- 13.Ichim MC. The DNA-based authentication of commercial herbal products reveals their globally widespread adulteration. Front Pharm. 2019;10(October):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imre S, Vlase L, Muntean DL. Bioanalytical method validation. Revista Romana de Medicina de Laborator. 2008;10(1):13–21. doi: 10.5958/2231-5675.2015.00035.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jairoun AA, Al-Hemyari SS, Shahwan M, Zyoud SH. Adulteration of weight loss supplements by the illegal addition of synthetic pharmaceuticals. Molecules. 2021 doi: 10.3390/molecules26226903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Lee JH, Park HJ, Kim JY, Cho S, Kim WS. Determination of non-opioid analgesics in adulterated food and dietary supplements by LC–MS/MS. Food Addit Contam—Part A Chem, Anal, Control, Expo Risk Assess. 2014;31(6):973–978. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2014.908262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kool J. Pharmaceutical properties of venom toxins and their potential in drug discovery. Indonesian J Pharm. 2016;27(1):1–8. doi: 10.14499/indonesianjpharm27iss1pp1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leito I. Validation of liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC–MS) methods (analytical chemistry) course. Tartu: University of Tartu; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton RB, Diener HC, Robbins MS, Garas SY, Patel K. Caffeine in the management of patients with headache. J Headache Pain. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0806-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matuszewski BK, Constanzer ML, Chavez-Eng CM. Strategies for the assessment of matrix effect in quantitative bioanalytical methods based on HPLC-MS/MS. Anal Chem. 2003;75(13):3019–3030. doi: 10.1021/ac020361s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mir NA, Masoodi TH, Wani AA, Ahmad PI. Ethno-Medicinal Utilization of Medicinal Plants Under Betula. 2017;18(January):14–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mwankuna CJ, Uwamaliya GA, Mariki EE, Mabiki F, Malebo HM, Mdegela R, Styrishave B. A HPLC-MS/MS method for screening of selected antibiotic adulterants in herbal drugs. Anal Methods. 2022;14(10):1060–1068. doi: 10.1039/d1ay01966j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nn A. Medicinal and aromatic plants a review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants. Princ, Strength Limit. 2015;4(3):3–8. doi: 10.4172/2167-0412.1000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nugraha RV, Ridwansyah H, Ghozali M, Khairani AF, Atik N. Traditional herbal medicine candidates as complementary treatments for COVID-19: a review of their mechanisms, pros and cons. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/2560645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paíga P, Lolić A, Hellebuyck F, Santos LHMLM, Correia M, Delerue-Matos C. Development of a SPE-UHPLC-MS/MS methodology for the determination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and analgesic pharmaceuticals in seawater. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;106:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parliament of the United Republic of Tanzania. (2002) Section Title

- 27.Pascale A. (2019) Drud adulterants and their effects on the health of users (Issue November 2019). http://www.cicad.oas.org/oid/pubs/Final ENG Drug adulterants and their effects on the health of users - a_pdf

- 28.Pratiwi R, Dipadharma RHF, Prayugo IJ, Layandro OA. Recent analytical method for detection of chemical adulterants in herbal medicine. Molecules. 2021;26(21):1–18. doi: 10.3390/molecules26216606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha T, Amaral JS, Oliveira MBPP. Adulteration of dietary supplements by the illegal addition of synthetic drugs: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Safety. 2016;15(1):43–62. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyman T, Stewart MJ, Grove A, Steenkamp V. Adulteration of South African traditional herbal remedies. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27(1):86–89. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sources of caffeine—Coffee and Health. (2017) http://www.coffeeandhealth.org/topic-overview/sources-of-caffeine/

- 32.Sveshnikova N, Yuan T, Warren JM, Piercey-Normore MD. Development and validation of a reliable LC-MS/MS method for quantitative analysis of usnic acid in Cladonia uncialis. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Traditional WHO, Strategy M. (2013) WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy. World Health Organization

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services. (2001) Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. Fda, May, 4–10. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm070107.pdf

- 35.Ugwah-Oguejiofor CJ, Adebisi IM. Potential medicinal plant remedies and their possible mechanisms against COVID-19: a review. IFE J Sci. 2021;23(1):161–194. doi: 10.4314/ijs.v23i1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaclavik L, Krynitsky AJ, Rader JI. Mass spectrometric analysis of pharmaceutical adulterants in products labeled as botanical dietary supplements or herbal remedies: a review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(27):6767–6790. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8159-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaysse J, Balayssac S, Gilard V, Desoubdzanne D, Malet-Martino M, Martino R. Analysis of adulterated herbal medicines and dietary supplements marketed for weight loss by DOSY 1H-NMR. Food Addit Contam—Part A Chem, Anal, Control, Exposure Risk Assess. 2010;27(7):903–916. doi: 10.1080/19440041003705821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verster JC, Koenig J. Caffeine intake and its sources: a review of national representative studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(8):1250–1259. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1247252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viana C, Zemolin GM, Dal Molin TR, Gobo L, Ribeiro SM, Leal GC, Marcon GZ, de Carvalho LM. Detection and determination of undeclared synthetic caffeine in weight loss formulations using HPLC-DAD and UHPLC-MS/MS. J Pharm Anal. 2018;8(6):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang XB, Zheng J, Li JJ, Yu HY, Li QY, Xu LH, Liu MJ, Xian RQ, Sun YE, Liu BJ. Simultaneous analysis of 23 illegal adulterated aphrodisiac chemical ingredients in health foods and Chinese traditional patent medicines by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26(3):1138–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WebMD. (2021) CAFFEINE_ Overview, Uses, Side Effects, Precautions, Interactions, Dosing and Reviews. WebMD

- 42.Welz AN, Emberger-Klein A, Menrad K. Why people use herbal medicine: Insights from a focus-group study in Germany. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu M, Huang B, Gao F, Zhai C, Yang Y, Li L, Wang W, Shi L. Assesment Adulterated Traditional Chinese Med China. 2019;10(November):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zamrodah Y. (2022) Evaluation of adulteration of herbal medicine used for treatment of erectile dysfunction in Nairobi County, Kenya: 15(2), 1–23. 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.13(5).2095-00

- 45.Zhu Q, Cao Y, Cao Y, Chai Y, Lu F. Rapid on-site TLC-SERS detection of four antidiabetes drugs used as adulterants in botanical dietary supplements. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(7):1877–1884. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7605-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]