Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to examine the correlation between the different types of migrant acculturation strategies according to Berry’s model of acculturation (integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalisation) and their effects on mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety and PTSD.

Study design

Systematic Review.

Methods

Three databases (PubMed, Ovid and Ebsco) were searched using different combinations of search terms to identify relevant articles to be included. The search terms were pre-identified using relevant synonyms for “migrants”, “mental health” and “integration”. The list of article titles from these searches were then filtered using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The mental health consequences included a range of common conditions including suicide/self-harm, depressive disorders, psychosis, as well as substance misuse.

Results

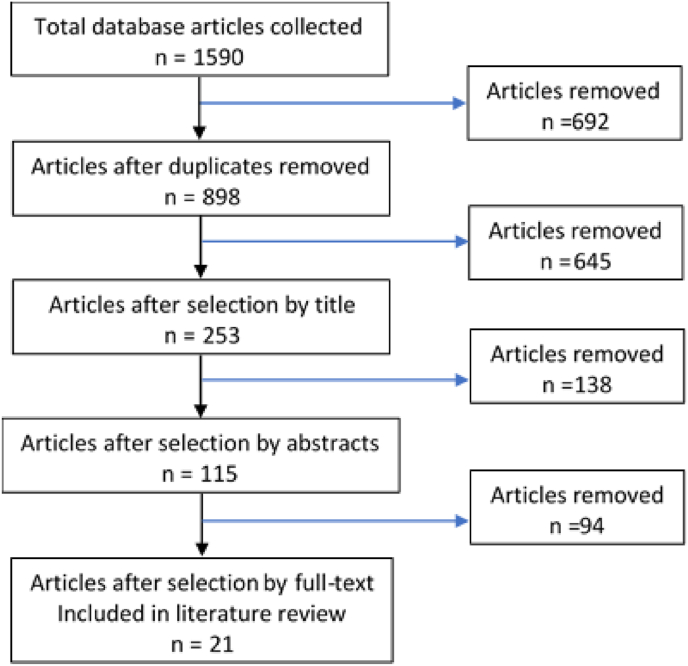

21 primary studies were included in the review, which assessed 61,885 migrants in total (Fig. 1 and Supplemental File 1). Of these, seven were cohort studies and fourteen were cross-sectional studies.

Most studies showed that marginalisation was associated with worse depression symptoms, compared to integration, assimilation and separation, while integration was associated with the least depressive symptoms.

Marginalisation more than triples the likelihood of anxiety-related symptoms compared to integration. Similarly, separation increased the likelihood of anxiety-related symptoms nearly six-fold.

Conclusions

Our review found out that marginalisation had the worst effects on mental health of the migrant populations while integration had the most positive effects. The study also identified three key sources which may contribute to acculturation stress and worse mental health: low education or skill set, proficiency of the host country’s language, and financial hardships.

Keywords: Migrant, Berry’s model, Acculturation, Integration, Assimilation, Separation, Marginalisation, Mental health, DEPRESSION, Anxiety, PTSD

1. Introduction

According to United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there has been an increase in the number of displaced persons globally from 41.1 million in 2010 to 79.5 million in 2019 [1]. Nearly 26 million of them are refugees with half of whom are under the age of 18 [2].

Migration is driven by a combination of factors that can be categorised as ‘macro-‘, ‘meso-’ and ‘micro-factors’ [3]. ‘Macro-factors’ include political turmoil, conflict, and environmental changes. These ‘macro-factors’ are the main drivers of forced migration that generate large numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. ‘Meso-factors’ include the influence of communication technology, and in particular social media, attracting people out of their origin countries into their destination country due to the perceived attractiveness of the destination country [3]. Moreover, diasporic links with family members who have migrated abroad can reinforce the desire to migrate from their origin country [3]. ‘Micro-factors’ include education, marital status, religion and personal willingness to migrate [3]. The ‘meso-’ and ‘micro-factors’ are often the key drivers for migrants who leave their own countries in search of better opportunities elsewhere [3].

The large increase seen in migration in recent years may be attributable to the significant ‘macro-factors’ driving migration. For example, political and economic turmoil in countries such as Venezuela have led to an exodus to other parts of Latin America, North America, and the Caribbean [2]. Environmental changes has similarly led to an increase in climate change immigrants from affected countries such as Bangladesh [4], and countries in the Lake Chad basin [3]. Climate change is manifesting directly through environmental degradation, food insecurity, water stress and economic decline. In turn, climate change has been linked with conflict, arguably the largest cause of forced migration in the last decade [5,6]. Since the so-called Arab spring, countries such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen have had seen large population movements both internally and abroad [1,2]. Continuing conflicts in several Sub-Saharan African countries including South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mali and Somalia also contribute to the rise in refugees globally [1,2].

Migration is however not without consequence for the migrants involved. One recognized consequence is the impact on the mental health and wellbeing of migrants. Greater prevalence of mental health conditions such as PTSD, depression and anxiety have been reported in migrants [[7], [8], [9]]. Traumatic events such as conflicts and arduous migration journeys can cause a range of traumatic psychological stress responses in these refugees [10]. In addition, migrants often face a whole host of new challenges when they arrive at their new geographic location, such as acculturation stress, discrimination, and considerable socioeconomic disadvantage.

Coping and cultural adaptation strategies have a key role in mitigating the adverse mental health consequences of migration [11]. Consequently, a fuller understanding of these strategies and how they influence the acculturation process is essential. Four main categories of acculturation strategies have been proposed by Berry (1997) [12]: Integration, Assimilation, Separation and Marginalisation. Integration refers to the strategy where someone from a different culture adopts the cultural norm of the country they have moved to, while retaining their own culture. Assimilation refers to the strategy where someone adopts the new culture while rejecting their own cultural norms. Separation refers to the strategy where someone retains their own cultural norms while rejecting the new culture of the country they have moved to, and marginalisation refers to the rejection of both the new and their own cultures.

This study aims to examine the correlation between the different types of migrant acculturation strategies and their effects on mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety and PTSD. In addition, the study aims to explore factors and determinants that may impact the acculturation and mental health of migrant populations. In this article, the term “migrants” was used to encompass refugees, asylum seekers, displaced people and migrants due to war or conflict, economic, environmental, political, and humanitarian reasons.

2. Methods

Three databases (PubMed, Ovid and Ebsco) were searched using different combinations of search terms (Table 1) to identify relevant articles to be included. The search terms were pre-identified using relevant synonyms for “migrants”, “mental health” and “integration”.

Table 1.

Search terms and permutations used for databases.

| Main terms | Migrants | Mental health | Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative terms | Refugees Asylum seekers Displaced person Migrants |

Mental health Depression PTSD Anxiety Suicide Substance abuse Self-harm Schizophrenia |

Integration Assimilation Belonging Settled Part of society Incorporation Inclusion |

With reference to Table 1, the search function used for all the databases was (Refugees OR Asylum seekers OR Displaced person OR Migrants) AND (Mental health OR Depression OR PTSD OR Anxiety OR Suicide OR Substance abuse OR Self-harm OR Schizophrenia) AND (Integration OR Assimilation OR Belonging OR Settled OR Part of society OR Incorporation OR Inclusion). From these searches, a total of 1590 articles were initially identified: 492 articles via Pubmed, 316 via Ovid and 782 via Ebsco.

The list of article titles from these searches were then filtered using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). We included only articles written in English that were focused on international migrants, acculturation and mental health. Articles written before 1999 were excluded as we were interested in studying the impacts of recent migratory patterns in the last 20 years. Case studies were excluded due to the recognized limitation that such anecdotal reports have significant potential for bias. As the focus was on migration abroad, hence studies of internal migration were excluded. We also excluded studies on children or adolescents as their acculturation and mental health are likely to be influenced by other complex factors unique to their development process.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Written in English Addressed the aim of the study directly |

Written in other languages Systematic reviews Case studies Internal migration Before 1999 Adolescents/Children |

The articles were filtered in four stages (Fig. 1): firstly the list was de-duplicated, then screened for relevance based on their titles, and subsequently filtered by abstracts and finally through full article appraisals. If there was uncertainty about the inclusion or exclusion of articles, they were discussed within the research team until consensus was reached.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart depicting methodology.

The final list of articles included were assessed for validity and quality using either the CASP tool for cohort studies (Supplemental File 2) or CEBMa checklist for cross-sectional studies (Supplemental File 3) as appropriate. The articles were then analysed and relevant information extracted using a predesigned template (Table 3). Migrants were categorised by: war/conflict reasons, economic reasons, environmental reasons, political reasons or humanitarian reasons (i.e. post disaster). Articles were also categorised between consequences reportedly arising within the short term (within 5 years of migration) or longer term (beyond 5 years of migration).

Table 3.

Classification of information extracted from each article.

| Type of migrant | War, Economic, Environmental, Humanitarian, Political |

|---|---|

| Migrant country of origin | Country, WHO region |

| Migrant destination | Country, WHO region |

| Type of mental health disorder | Suicide/Self-harm, Depression, PTSD, Anxiety, Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Addiction/Substance abuse, Behaviour disorders (Conduct, antisocial personality disorder), Psychosomatic Symptoms, Others (specify) |

| Type of article | Cohort study, Cross-sectional |

| Length of study | Short term (<5 years), Long-term (>5 years) |

| Effects of acculturation on mental health | Integration, Assimilation, Separation, Marginalisation |

The mental health consequences included a range of common conditions including suicide/self-harm, depressive disorders, psychosis, as well as substance misuse. According to ICD-11, depressive disorders are characterised by depressive mood (feelings of sadness, irritability, emptiness) or loss of pleasure accompanied by other cognitive, behavioural, or neurovegetative symptoms that significantly affect the individual’s ability to function [13]. Some symptoms include low mood, low self-esteem, feelings of guilt and hopelessness, lack of motivation, and suicidal ideation.

Anxiety disorders encompass a wide array of mental health conditions, with the predominant symptom of feeling anxious. For the purposes of this study, the clinical definition and symptoms of anxiety disorders was obtained from the ICD-11 classification of Mental Health and Behavioural disorders [14]. The key symptoms of anxiety disorders can include feeling of losing control, anxiety and other accompanying physical symptoms.

ICD-11 describes PTSD as re-experiencing traumatic events in a vivid manner which leads to persistent perceptions of heightened threat and avoiding thoughts, memories or activities reminiscent of the event [15]. The symptoms have to persist for several weeks and cause impairment to areas of functioning in an individual.

3. Results

21 primary studies were included in the review, which assessed 61,885 migrants in total (Fig. 1 and Supplemental File 1). Of these, seven were cohort studies and fourteen were cross-sectional studies. Migrants in these studies originated from multiple countries, but principally from Russia, Iran, Turkey, Syria, former USSR nations, Morocco, Eritrea, and Sudan. The host destinations were mainly European countries and North America. The main reasons for migration cited in these studies were primarily due to war (74.4%), or economic reasons (75.7%). Of the 21 studies, three analysed the effects on mental health in the short term (<5 years), eleven measured longer term effects on mental health (>5 years), three measured both short and longer term effects, and four papers did not specify the duration. According to the CASP and CEBMa checklists, twelve studies were assessed to be of high quality, while the rest were considered to be of lower quality.

3.1. Different acculturation strategies and their impact on depressive symptoms

3.1.1. Depressive symptoms

P9, P10, P21 showed that marginalisation was associated with worse depression symptoms, compared to integration, assimilation and separation (Table 4). P4, P6, P9, P10, P19, P21 showed that integration was associated with the least depressive symptoms. However, two articles [P9, P10] found no statistically significant differences between the effects of integration and assimilation on levels of depressive symptoms. One article [P21] reported no significant difference between integration and separation on levels of depressive symptoms. Three studies observed that assimilation is associated with lower depressive symptoms compared to separation [P4, P9, P10].

Table 4.

Each cell shows the articles supporting the acculturation strategy in the title column against the acculturation strategy in the corresponding row. NS - non-significant differences reported.

| Superior | Integration | Assimilation | Separation | Marginalisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | P9 – NS P10 – NS |

P21 | – | |

| Assimilation | P4, P6, P19 | – | – | |

| Separation | P4, P9, P10, P19 | P4, P9, P10 | – | |

| Marginalisation | P9, P10, P19, P21 | P9, P10 | P21 |

3.1.2. Anxiety symptoms

One study [P21] showed that marginalisation more than triples the likelihood of anxiety-related symptoms (OR 3.70; 95% CI, 1.03–13.31) compared to integration. Similarly, separation increased the likelihood of anxiety-related symptoms nearly six-fold (OR 5.82; 95% CI, 1.20–28.34).

3.2. Level of acculturation and its impact on mental health

Ten studies reported on the degree of acculturation and its effects on depression. Four studies observed a statistically significant negative correlation between acculturation and depressive symptoms [P7, P14, P15, P19]. One article [P18] reported that levels of acculturation had no significant effect on depressive symptoms, but had a positive correlation with life satisfaction. Three studies reported on the degree of acculturation and its effects on anxiety. They observed a negative correlation between acculturation and anxiety symptoms [P7, P14]. Two studies [P14, P21] reported on the degree of acculturation and its effects on PTSD. These studies found that higher degrees of acculturation was associated with lower symptoms of PTSD.

3.3. Factors that negatively impact acculturation of migrants

A total of eleven studies reported factors that may influence the level of acculturation (Supplemental file 4). Sixteen factors were identified, and were categorised as intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The main intrinsic factors were PTSD [P1], worry about family or friends [P5], host language proficiency [P4, P5], significant past mental health conditions [P14], the extremes of age [P14, P19], nationality of the migrant [P7], and low education status [P19]. One paper [P18] reported no effect of gender over 18 years of age, and another [P16] found no effect of migration status on acculturation.

The extrinsic factors that negatively impacted acculturation were longer duration of stay [P2], unemployment [P19] and lack of a long-term partner [P19]. Interestingly, nationality was identified as a factor that may impact acculturation of migrants. This may be due to similarities in language, practices and culture, or having a well-established community in the host country. One paper [P5] suggested that discrimination towards the migrants had no statistical significance on acculturation.

3.4. Factors that negatively impact the general mental health of migrants

A total of five studies reported on the factors that may influence the level of acculturation (Supplemental file 5). Nineteen factors were identified. Intrinsic factors included ethnicity [P1], poor physical health [P1], lower levels of host language proficiency [P13], low sense of belonging [P13, P17], low education [P17], extremes of age [P17], female gender [P17], and previous war experiences [P20]. Extrinsic factors identified included not being married [P1], lack of social activity outside of home [P1], unemployment [P1, P17], integration stressors [P5], greater financial hardships [P13], lower income [P17], and less preservation of cultural traditions [P20]. However, nationality [P17] and length of stay in the country over 5 years [P17] did not appear to have a negative impact on their mental health. In the short term, i.e. length of stay in the host country less than five years, had a positive impact on mental health [P17].

3.5. Factors associated with a higher risk depression symptoms

A total of twelve studies reported on the factors that may influence the level of acculturation (Supplemental file 5). 22 factors were identified. Intrinsic factors included female gender [P3, P9, P18], low skills [P7], low education level [P8, P9, P12], worse host language proficiency [P9], poor perceived health [P11], poor physical health [P15], nationality [P16], strong cultural preservation [P8], and past traumatic events [P6]. However, some studies showed that age [P4, P10], gender [P10] and level of education [P10] had no effect on increasing the risk of depression symptoms.

Extrinsic factors included perceived cultural gap [P11], low sociocultural adaptation [P1], stressful life events [P11], high levels of acculturative stress [P12], family dysfunction [P12], poor family relationships [P15 ], low income [P3, P12], number of children living in proximity [P11], assistance from adult children [P11], length of stay [P11], ineffective social support [P12], lack of acculturation [P15], and involuntary or forced migration [P18]. The lack of visa status was not reported to have an impact on increasing the risk of depression symptoms [P15].

4. Discussion

Our review showed how the different acculturation strategies affected the mental health of migrants. The most striking finding was that marginalisation had the worst effects on mental health of the migrant populations. This corroborates with previous observations by Yoon et al. [16], and Berry and Hou [17]. Marginalisation is a complex phenomenon. Migrant populations may choose to reject both the host and their own ethnic culture for various reasons. Migrants may feel discrimination and rejection from both cultures when their entry to the host country is not legitimate. For example, it has been reported that some Mexican migrants in the United States were rejected by their own ethnic groups due to their illegal immigration status, which was associated with an increased risk of depression [18]. Alternatively, systemic discrimination faced in the host country might cause migrants to reject their own cultures for self-protection and in an attempt to blend into host societies better.

Marginalisation as an acculturation strategy would likely lead to poorer mental health outcomes. A possible explanation for this could be that ethnicity provides a social platform that offers an opportunity for people to develop interpersonal relationships. This may be especially important in migrant and minority communities. Better social networks and relationships may help migrants cope with adverse and stressful situations [19]. Similarly, one’s ethnic identity may help moderate the stress of racial and ethnic discrimination. For example, an epidemiological study on Fillipino Americans in 2003 concluded that having a sense of ethnic pride, involvement of ethnic practices and cultural commitment helps protect mental health [20]. Without a sense of ethnic identity, there may be a lack of sense of solidarity in the face of discrimination. This may in turn lead to greater acculturation stress and stress from discrimination, thus leading to worse mental health [21]. Moreover, by rejecting both the host and their own ethnic cultures, migrants may lack a sense of identity or belonging to either community. This sense of belonging may be an important buffer against depressive symptoms [22].

The majority of the studies reviewed indicate that integration had the most positive effects on the mental health of migrant populations. Several studies also concluded that the effects of assimilation on mental health may also be as beneficial as that of integration. Integration as an acculturation strategy (adopting both the host culture and their own) appears to have a more significant positive effect than assimilation (adopting the host culture whilst rejecting their own). This is on the basis that having a strong sense of ethnic identity and community may help reduce one’s perception of discrimination in the host societies. Moreover, a positive ethnic identity also can help buffer and reduce the negative effects of discrimination [23,24]. The quality of relationships also have a direct influence on the mental health of migrants. Social ties have previously been shown to affect mental health, health behaviours, physical health and even mortality [25]. These effects can vary in a migrant population as migrants might be living in large communities or isolated depending on the type of acculturation strategies they have adopted. Social networks that provide avenues to communicate concerns and reduce stress might be less available in the migrant population due to the lack of accessibility [26,27].

Another theme identified was acculturation stress. As this is a broad term, three key sources which may contribute to acculturation stress were identified: low education or skill set, proficiency of the host country’s language, and financial hardships, which might be a consequence of the preceding factors. People with low financial capital are more likely to have a disproportionate burden of not only physical disease, but also mental ill health such as depression [28,29]. Unemployment, precarious employment, and having a limited skill-set, can all lead to negative mental health outcomes in migrant populations [30,31]. Furthermore, the lack of language proficiency of the host country further aggravates the stress of acculturation. The inability of migrants to speak the host language fluently impedes their ability to carry out activities of daily living, seek employment or integrate well with the host society [32,33].

This review has several limitations. Firstly, there was considerable heterogeneity in the methodologies, the populations studied and cultural contexts amongst the included studies. Secondly, the definitions of mental health conditions and symptoms used in the studies were not consistent. For example, some of the cross-sectional studies did not use a medical diagnosis but use symptomatology instead. Most of the studies included in the systematic review were from high income countries such as North America and European nations. Articles from countries which have large migrant populations like Turkey and Pakistan might have been excluded if they were not published in English.

Of the four acculturation strategies, integration was identified as the approach that has the most positive impact on migrant mental health. As such, governments of host countries should aim to implement policies and schemes to assist migrants adopt and accept both the host and their own cultures to reduce risk of developing mental health conditions. Further research is needed to identify social policies and interventions that best promote integration.

The building of social networks is likely to be key. There may be a role for providing social support such as counselling, links to support groups or shared-interest groups. Negative factors such as low skills, lower education levels and unemployment need to be addressed too. This could be through providing migrants with opportunities to pursue further education and skills training in the form of bridging courses to higher education, or courses targeted at specific skills which may be relevant to local economies. These skills and educational opportunities may not only help boost their chances of employment and self-sufficiency, but also their quality of life and general mental health. In addition, it is important for host governments to provide affordable and accessible mental health services for migrants. Governments could identify at-risk individuals using the factors highlighted in this systematic review. Given the problem of limited public resources, these scarce resources could be effectively channelled to develop mental health interventions for these at-risk individuals.

The rising trends in global migration are likely to continue and migration will be a ubiquitous phenomenon affecting many countries globally. Indeed, some host societies such as the European Union have recognized the need to address these issues and have introduced various policies and practices to better integrate migrants into their society. It remains a major public health challenge of our time and both further research into this field and action is needed in order to better inform public health policy and interventions.

Author statements

No ethical approval is required as papers analysed were freely available on the databases. No funding was required for this review. Lee A is the editor for this journal.

Declaration of competing interest

Andrew Lee is the co-Editor-in-Chief of Public Health in Practice. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100069.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Migration . 2020. Un.org.https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/migration/index.html [cited 27 July 2020]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Refugees U. 2020. Figures at a glance [Internet]. UNHCR.https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html [cited 27 July 2020]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castelli F. Drivers of migration: why do people move? J. Trav. Med. 2018;25(1) doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berchin I., Valduga I., Garcia J., de Andrade Guerra J. Climate change and forced migrations: an effort towards recognizing climate refugees. Geoforum. 2017;84:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner K., Hamza M., Oliver-Smith A., Renaud F., Julca A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Nat. Hazards. 2010 Dec 1;55(3):689–715. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abel G., Brottrager M., Crespo Cuaresma J., Muttarak R. Climate, conflict and forced migration. Global Environ. Change. 2019;54:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tinghög P., Malm A., Arwidson C., Sigvardsdotter E., Lundin A., Saboonchi F. Prevalence of mental ill health, traumas and postmigration stress among refugees from Syria resettled in Sweden after 2011: a population-based survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Close C., Kouvonen A., Bosqui T., Patel K., O’Reilly D., Donnelly M. The mental health and wellbeing of first generation migrants: a systematic-narrative review of reviews. Glob. Health. 2016;12(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0187-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steel Z., Silove D., Phan T., Bauman A. Long-term effect of psychological trauma on the mental health of Vietnamese refugees resettled in Australia: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silove D., Ventevogel P., Rees S. The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatr. 2017;16(2):130–139. doi: 10.1002/wps.20438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo B.C. Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: a theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. 2014 Jan 1;2(1):16–33. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2013.843459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry J. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organisation . WHO; 2020. ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics.https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/399670840 [online] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organisation . WHO; 2020. ICD-11 - Anxiety [online]https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/2027043655 [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation . WHO; 2020. ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics [online]https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/2070699808 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon E., Chang C., Kim S., Clawson A., Cleary S., Hansen M., et al. A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2013;60(1):15–30. doi: 10.1037/a0030652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry J., Hou F. Immigrant acculturation and wellbeing in Canada. Can. Psychol. 2016;57(4):254–264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb C., Xie D., Meca A., Schwartz S. Acculturation, discrimination, and depression among unauthorized Latinos/as in the United States. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2017;23(2):258–268. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanderhorst R., McLaren S. Social relationships as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in older adults. Aging Ment. Health. 2005;9(6):517–525. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mossakowski K. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003;44(3):318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phinney J.S. In: Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Chun K.M., Balls Organista P., Marín G., editors. American Psychological Association; 2003. Ethic identity and acculturation; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sargent J., Williams R., Hagerty B., Lynch-Sauer J., Hoyle K. Sense of belonging as a buffer against depressive symptoms. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2002;8(4):120–129. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene M., Way N., Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev. Psychol. 2006;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee R. Resilience against discrimination: ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2005;52(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umberson D., Karas Montez J. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenblatt M., Becerra R., Serafetinides E. Social networks and mental health: on overview. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1982;139(8):977–984. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.8.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saeri A., Cruwys T., Barlow F., Stronge S., Sibley C. Social connectedness improves public mental health: investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatr. 2017;52(4):365–374. doi: 10.1177/0004867417723990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everson S., Maty S., Lynch J., Kaplan G. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002;53(4):891–895. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorant V. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brydsten A., Rostila M., Dunlavy A. Social integration and mental health - a decomposition approach to mental health inequalities between the foreign-born and native-born in Sweden. Int. J. Equity Health. 2019;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0950-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jurado D., Alarcón R., Martínez-Ortega J., Mendieta-Marichal Y., Gutiérrez-Rojas L., Gurpegui M. Factors associated with psychological distress or common mental disorders in migrant populations across the world. Rev. Psiquiatía Salud Ment. 2017;10(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Priebe S., Giacco D., El-Nagib R. 47th ed. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2016. Public Health Aspects of Mental Health Among Migrants and Refugees: A Review of the Evidence on Mental Health Care for Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Irregular Migrants in the WHO European Region. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delander L., Hammarstedt M., MÅnsson J., Nyberg E. Integration of immigrants: the role of language proficiency and experience. Eval. Rev. 2005;29(1):24–41. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04270230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.