Abstract

A method for x-ray-guided robotic positioning of surgical instruments is reported and evaluated in preclinical studies of spine pedicle screw placement with the aim of improving delivery of transpedicle drills and screws. The known-component registration (KC-Reg) algorithm was used to register the 3D patient CT and the surface model of a drill guide to intraoperatively acquired 2D radiographs. Resulting transformations, combined with offline hand-eye calibration, drive a robotically-held drill guide to target trajectories established in the preoperative patient CT. The proposed method was assessed against more conventional surgical tracker guidance, and robustness to clinically realistic errors was tested in phantom and cadaver studies. Target registration error (TRE) was computed as drill guide deviation from the planned trajectory. The KC-Reg approach resulted in 1.51 ± 0.51 mm error at tooltip and 1.01 ± 0.92° in approach angle, showing comparable performance to the tracker-guided approach. In cadaver studies with anatomical deformation, TRE of 2.31 ± 1.05 mm and 0.66 ± 0.62° were observed, with statistically improved performance over a surgical tracker through registration of locally rigid bony anatomy. X-ray guidance offers an accurate means of driving robotic systems that is compatible with conventional fluoroscopic workflow. Specifically, such procedures involve multi-planar fluoroscopic views that are qualitatively interpreted by the surgeon; the KC-Reg approach accomplishes this using the same multi-planar views to provide greater quantitative accuracy and valuable guidance and QA. The method was robust against anatomical deformation due to the radiographic scene’s local nature used in registration, presenting a potentially major surgical benefit.

Keywords: Known-component registration, 3D-2D registration, image-guided surgery, surgical robotics

1. INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE

A growing number of procedures in orthopaedic spine surgery rely on robust spinal fixation through accurate placement of screws within the vertebrae. This task involves targeting a narrow bone corridor within the vertebral body, in proximity to critical structures, and is often repeated for multiple vertebral levels (e.g., in multibody spinal fixation) during a single case. Screw malplacement–e.g., perforation of the cortical bone–is observed in as high as 41% and 55% of lumbar and thoracic cases respectively,1 often requiring immediate/costly revision surgeries.

The current standard of care involves manual placement of pedicle screws, commonly under x-ray fluoroscopy guidance, which relies on correct identification of anatomical features and strong hand-eye coordination to navigate a 3D space from 2D projective views. While surgical tracking technologies are well established, their adoption in fluoroscopy-guided procedures have been limited, potentially due to incompatibility with existing clinical workflow and/or additional requirements on surgical instruments.2,3

Motivated by high accuracy requirements and procedural repetitiveness (for multiple pedicle trajectories along the spine), this work proposes robotic positioning of a pedicle drill guide, thus presenting the surgeon with an accurately placed port through which other instruments (e.g., k-wires or screws) may be delivered. The proposed approach builds on a 3D-2D registration algorithm, which incorporates information on device shape (known component) to solve for its 3D pose from 2D radiographs. On top of utilizing images already acquired in existing workflow, the robotic approach has the additional benefit of keeping surgeons’ hands outside the x-ray field of view (FoV) during imaging.4 The manuscript below summarizes and evaluates the approach in phantom and cadaver studies, in comparison to a more conventional approach in which the image-registration pipeline is replaced by an optical tracker.5

2. METHODS

2.1. Known-component registration

The primary means for guidance is a novel algorithm dubbed Known-Component Registration (KC-Reg), which uses a two-step process to perform a 3D-2D registration of the patient anatomy (represented by a preoperative CT volume, v), followed by the registration of a device of known design (viz., known component, KC).6,7 The objective function for the former step may be expressed as:

| (1) |

which can be used to iteratively solve for the transformation that maximizes the gradient orientation (GO) between the acquired radiographs (Rθ) and the simulated forward projections (viz., digitally reconstructed radiographs) of the volume at pose T in the coordinate frame of the imaging device (C-arm, c).8 The current implementation typically completed the registrations within several minutes.

Drill guide as a known component.

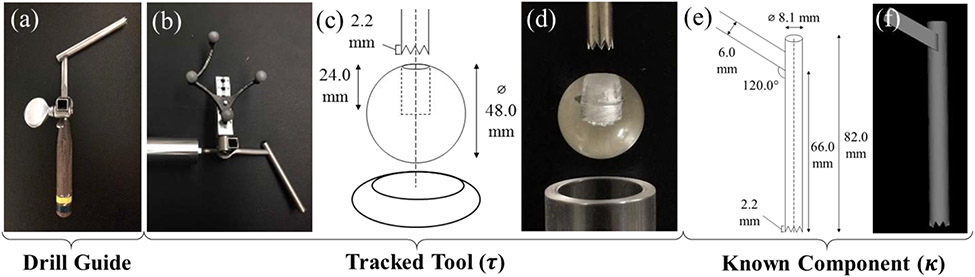

Empirical measurements of the pedicle drill guide tool (Figure 1a) were used to create the component surface model (κ) in Figure 1e-f, where the tooltip was defined as the centroid of the drill guide teeth and the central axis aligned with the cannula. A small portion of the handle was included in the model to ensure a unique solution of the 3D pose. Substituting v with κ in Equation (1) and using the GC (gradient correlation) metric that favors high intensity edges (metal/tissue),9 the component pose (Tκ) can be solved in an analogous manner. Combined with former step, a solution for the drill guide (component) pose in the patient’s preoperative CT scan can be computed as .

Figure 1.

(a) Standard hand-held pedicle drill guide; (b) custom optical marker attachment, (c-d) sphere-in-circle attachment for pivot calibration, keeping the tooltip at the sphere center during pivoting; (e) measured instrument dimensions; (f) KC-Reg component surface model.

Drill guide as a tracked tool.

For purposes of obtaining a baseline for comparison, an optical tracker was used as a more conventional method for guiding the robot. Unlike the KC approach, this required modification of the instrument to accommodate an optical marker, m, as in Figure 1b. A tooltip calibration was performed using a spherical attachment to obtain the translational offset , followed by an axis calibration to obtain the rotational alignment . The resulting pose of the tracked tool (τ) is therefore in the coordinate frame of the optical tracker (o)–analogous to of the KC approach.

2.2. Hand-eye calibration

Separate, offline calibration steps are needed to relate the robot (UR5, Universal Robots, Odense, Denmark) end-effector to the known (κ) and tracked (τ) components. Formulation of this problem depends upon measurements of a target tool at multiple poses from two fixed reference coordinate frames defined as the hand H and eye E respectively. Then, for any two-set of measurements (i, j):

| (2) |

such that Hi is the robot pose, specifically a transform from the robot base to the end-effector , and Ei is or , for KC and tracker guidance, respectively. Substituting , and , the hand-eye calibration (X) simplifies to the solution of the well-known AX = XB problem.10

In the experiments detailed below, 32 randomized sets of robot end-effector poses were measured within a volume spanning 5x5x5 cm3. The tracker measurements were averaged to reduce potential jitter, and the KC measurements used 8 radially distributed projections (more than the minimum 2 required) to solve for the component. 5 independent trials were obtained to further assess the performance of different solvers through a leave-one-out analysis and measurement of overall consistency of the solution relative to measurement noise / pose selection.

2.3. Robotic alignment of the drill guide

All thesteps covered above can be performed offline prior to the procedure. Thus, the remaining task is to intraoperatively drive the robot to the planned trajectory , defined within the preoperative CT. Using 3 radiographs (e.g. AP, lateral, and oblique) to simultaneously solve for and and following the chain of transforms depicted in Figure 2, the desired robot end-effector pose () can be derived from an initial pose by,

| (3) |

Figure 2.

Illustration of the transformation tree for tracker (left, red), and the proposed KC (right, blue) guidance.

Similarly, an analogous expression can be defined for the tracker guidance scenario:

| (4) |

where is the pose of a rigidly secured reference marker and is a fiducial registration to the preoperative volume. Note that these two transforms are simply replaced by in KC guidance, which gets updated with each new radiographic acquisition.

2.4. Experiments in phantom and cadaver

As shown in Figure 3a, the viability of optical tracking guidance was validated in a separate, stable setting prior to experiments. Thereafter, the accuracy and feasibility of the proposed approach was evaluated in phantom experiments, targeting 17 pedicle trajectories spanning T1–L5. For each trajectory, the robot-held drill guide was placed close to the plan, such that both the bony anatomy and the component were captured within the x-ray FoV. Following acquisition of AP, lateral, and oblique radiographs, the robot was driven to the planned trajectory and a cone-beam CT scan was acquired at the target for offline error analysis. Returning back to the same initial pose, the same steps were repeated for tracker guidance. For cadaver experiments shown in Figure 3b, the lumbar spine was exposed, and 6 trajectories spanning L3–L5 were targeted.

Figure 3.

Experimental setups: (a) phantom experiments on the optical bench; (b) cadaver experiments in the operating room, with the robot mounted on a mobile cart and positioned next to the operating table.

The accuracy of the system was quantified in terms of the target registration error at the drill guide tip (TREx) and in aligning the principal component axis to target plan (TREϕ):

| (5) |

where the last column ([·]4) of the transformation matrix defines the tip, and the 3rd column (or last column of rotation matrix) defines the principal (z) axis of the component. The true poses of the patient and component were established by independent 3D-3D registrations of the CT volume () and component model () to the cone-beam reconstruction, respectively.

3. RESULTS AND BREAKTHROUGH WORK

3.1. Accuracy and consistency of hand-eye calibration

While hand-eye calibration is well established for robotic control using an optical tracker, performing it within the context of image-based guidance warrants additional study. Evaluating different solvers for AX = XB, the distribution of the translational component of leave-one-out errors (εx) in Figure 4a suggests the use of certain separable solvers over others.

Figure 4.

(a) Distribution of translational leave-one-out errors for AX = XB solvers by (from left to right) Tsai, Horaud, Park, Chou, Andreff, Daniilidis, Shiu, Wang et al.; (b) εx values for a selected calibration using the KC approach; (c) differences across repeat trials for the tracker (upper left) and KC (lower right) approaches.

Using the solver by Park et al, εx was observed to be 0.60 ± 0.25 mm (Figure 4b). A cross validation across repeat trials in Figure 4c highlights consistent results for the KC approach. A possible reason for the improved consistency of the KC approach might be due to its ability to capture a larger variety of drill guide poses, c.f. the passive markers are only visible from the side that faces the tracker.

3.2. Phantom study

Analyzing the errors for KC guidance yielded 1.51 ± 0.51 mn TREx and 1.01 ± 0.92° TREϕ, while the tracker guidance resulted in 2.17 ± 0.89 mn TREx and 0.94 ± 0.48° TREϕ. Although the results are comparable overall, a paired t-test revealed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) error reduction in TREx with KC. A likely reason is the (intentional) spatial distribution of registration fiducials around the lumbar region (only), as such limited coverage is fairly common in normal practice. This results in a degradation in TRE for the tracker at greater distance from the lumbar vertebrae, as shown in Fig. 5c. KC is shown to be robust to such effects due to updated registration of the patient with new acquisitions. Still, both approaches offered acceptable error (within pedicle cortex) as shown in Figure 5e.

Figure 5.

Results of phantom study: (a) TREx and (b) TREϕ for KC and tracker guided approaches; (c) TREx and (d) TREϕ relative to the target vertebrae; (e) error windows in relation to planned trajectory of a 6×45 mm screw (green) based on mean errors for KC (cyan) and tracker (magenta) guidance.

3.3. Cadaver study

Robotic KC guidance in the cadaver resulted in 2.31 ± 1.05 mm TREx and 0.66 ± 0.62° TREϕ, slightly higher than results in phantom. While the gradients produced by the deforming soft tissue and the reduced image quality due to higher attenuation (especially in the lateral view) presented challenges, the approach successfully stayed within the bony cortex as shown in Figure 6c. Despite care in transformation and placement of the specimen on the table, the induced deformation from the time of preoperative CT scan and the experiment resulted in significantly (p < 0.05) higher errors when guiding with the tracker. In comparison, the KC approach remained robust to such changes as it relies on locally rigid structures (3–4 vertebrae) when registering the patient anatomy.

Figure 6.

Results of cadaver study: (a) TREx and (b) TREϕ for KC and tracker guided approaches, (c) error windows in relation to planned trajectory of a 6Õ45 mm screw (green) based on mean errors for KC (cyan) and tracker (magenta) guidance.

4. CONCLUSIONS

A method for robotic positioning of a pedicle drill guide was presented, using fluoroscopic views already acquired within typical surgical workflow along with prior knowledge on patient anatomy (CT) and instrument shape. Common practice in orthopaedic or neuro- spine surgery involves multi-planar fluoroscopic views that are qualitatively interpreted by surgeons to assess 3D placement of surgical devices. The KC approach accomplishes this from the same multi-planar views, providing guidance and QA that is accurate, quantitative, reproducible, and less subject to an individual’s qualitative image interpretation. Moreover, KC guidance is less susceptible to the effects of anatomical deformation than conventional tracker guidance due to its use of local image features in the fluoroscopic FoV. In phantom and cadaver experiments emulating pedicle screw placement, KC guidance was shown to perform comparably and, under certain conditions (e.g., global anatomical deformation), better than tracker guidance. The approach could be readily translated to other fluoroscopically guided procedures, such as percutaneous approaches where reliance on visual cues is not possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grants R01-EB-017226 and 5 T32 AR067708-03. The authors thank Drs. Sebastian Vogt, Gerhard Kleinszig, Markus Weiten, and Wei Wei (Siemens Healthineers) for valuable assistance regarding the mobile C-arm used in this work. The authors would also like to thank Mr. Ronn Wade (University of Maryland Anatomy Board) and Dr. Rajiv Iyer (Johns Hopkins Neurosurgery) for assistance with the cadaver specimen, Dr. Matthew Jacobson (Johns Hopkins Biomedical Engineering) for assistance with C-arm calibration and CBCT reconstruction, and Mr. Alex Martin (Johns Hopkins Biomedical Engineering) for design and fabrication of the drill guide robot attachment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pema F et al. , “Pedicle screw insertion techniques: an update and review of the literature,” in Musculoskeletal Surgery 100(3), pp. 165–169 (2016) [doi: 10.1007/s12306-016-0438-8]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koivukangas T, Katisko JP, and Koivukangas JP, “Technical accuracy of optical and the electromagnetic tracking systems.,” Springerplus 2(1), 90 (2013) [doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-90]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galloway RL and Miga MI, “Organ Deformation and Navigation,” in Imaging and Visualization in The Modern Operating Room: A Comprehensive Guide for Physicians, Fong Y et al. , Eds., pp. 121–132, Springer New York, New York, NY: (2015) [doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2326-7_9]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RH and Stoianovici D, “Medical Robotics in Computer-Integrated Surgery,” in IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 19(5), pp. 765–781 (2003) [doi: 10.1109/TRA.2003.817058]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi T et al. , “Robotic drill guide positioning using known-component 3D–2D image registration,” J. Med. Imaging 5(2), 21212–21218 (2018) [doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.5.2.021212]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uneri A et al. , “Known-component 3D-2D registration for quality assurance of spine surgery pedicle screw placement,” Phys. Med. Biol 60(20), 8007–8024 (2015) [doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/20/8007]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uneri A et al. , “Intraoperative evaluation of device placement in spine surgery using known-component 3D-2D image registration,” Phys. Med. Biol 62(8), 3330–3351 (2017) [doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa62c5]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Silva T et al. , “3D–2D image registration for target localization in spine surgery: investigation of similarity metrics providing robustness to content mismatch,” Phys. Med. Biol 61(8), 3009–3025 (2016) [doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/8/3009]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penney GP et al. , “A comparison of similarity measures for use in 2-D-3-D medical image registration.,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 17(4), 586–595 (1998) [doi: 10.1109/42.730403]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah M et al. , “An Overview of Robot-Sensor Calibration Methods for Evaluation of Perception Systems,” Proc. Work. Perform. Metrics Intell. Syst. - Permis ‘12(c), 15 (2012) [doi: 10.1145/2393091.2393095]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]