Abstract

Bacillus subtilis can grow under anaerobic conditions, either with nitrate or nitrite as the electron acceptor or by fermentation. A DNA microarray containing 4,020 genes from this organism was constructed to explore anaerobic gene expression patterns on a genomic scale. When mRNA levels of aerobic and anaerobic cultures during exponential growth were compared, several hundred genes were observed to be induced or repressed under anaerobic conditions. These genes are involved in a variety of cell functions, including carbon metabolism, electron transport, iron uptake, antibiotic production, and stress response. Among the highly induced genes are not only those responsible for nitrate respiration and fermentation but also those of unknown function. Certain groups of genes were specifically regulated during anaerobic growth on nitrite, while others were primarily affected during fermentative growth, indicating a complex regulatory circuitry of anaerobic metabolism.

In recent years, Bacillus subtilis has been shown to be a facultative bacterium capable of growing with nitrate or nitrite as the electron acceptor or growing by fermentation in the absence of oxygen (22). The process of dissimilatory reduction of nitrate to ammonia is carried out by two enzymes, the membrane-bound nitrate reductase and the NADH-dependent nitrite reductase (8, 9, 19). The nitrate reductase is encoded by the narGHJI operon, which is controlled by FNR, an anaerobic regulator (12). The nitrite reductase is encoded by the nasDEF operon, which is not controlled by FNR, since no effect on anaerobic growth on nitrite has been observed in fnr mutant strains. Both fnr and nasDEF regions are regulated by the two-component signal transduction system ResDE, which also controls the expression of the resABC, qcrABC, and cta regions (16, 23, 28). Furthermore, the ResDE− mutant requires six-carbon sugars for normal growth. These results indicate that ResDE plays a global role in both aerobic and anaerobic respiration.

In the absence of nitrate and nitrite, B. subtilis grows poorly on glucose under anaerobic conditions (18). Efficient fermentative growth can be obtained if pyruvate is provided. Lactates, acetate, and ethanol are found to be the end products of fermentation. Fermentative growth requires the ftsH gene but does not require the FNR gene. In addition, resD and resDE mutations have a moderate effect on fermentative growth. These results suggest that nitrate respiration and fermentation are governed by divergent regulatory pathways (18).

Recent advances in functional genomic technologies such as DNA microarray construction provide a unique way to explore the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale (6). The fact that the complete sequence of B. subtilis is available (14) makes it feasible to apply these functional genomic technologies. To investigate the global changes in gene expression associated with anaerobiosis in B. subtilis, we constructed DNA microarrays containing 4,020 open reading frames (ORFs). These microarrays were used to investigate the differential gene expression patterns of aerobic and anaerobic cultures during exponential growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis 168 derivative JH642 was obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Columbus, Ohio). Strain THB2 was from Dieter Jahn (8).

B. subtilis strains were grown at 37°C in 2× YT medium (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Maryland) supplemented with 1% glucose and 20 mM K3PO4 (pH 7.0). For aerobic growth, 20 ml of prewarmed medium inoculated with 0.1 ml of overnight culture (1:200 dilution) was placed in a 250-ml flask on a rotary platform, which was rotated at the speed of 250 rpm. For anaerobic growth, 120 ml of prewarmed medium was placed in a 150-ml serum bottle. Potassium nitrate at a concentration of 5 mM or potassium nitrite at a concentration of 2.5 mM was added for anaerobic growth with alternative electron acceptors. The serum bottle was capped with a Teflon-coated stopper, the gas phase was flushed, and the bottle was filled with argon gas. For RNA isolations, samples were taken at an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.4 for aerobic cultures, an OD of 0.25 for cultures grown on nitrate, an OD of 0.15 for cultures grown on nitrite, an OD of 0.12 for cultures grown by fermentation, and an OD of 0.16 for cultures grown by fermentation in the presence of pyruvate.

PCR amplification.

The oligonucleotides for all 4,100 ORFs of the B. subtilis genome were purchased from Genosys (Woodlands, Tex.). The HotStart PCR kit from Qiagen (Valencia, Calif.) was used for all PCRs. The cycling conditions were as follows: 30 s of annealing at 55°C, 2 min of elongation at 72°C, and 30 s of denaturing at 95°C. The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick Multiwell PCR purification kit from Qiagen, and the quality of the PCRs was checked by electrophoresis on an agarose (1%) gel. Each image was stored in a database, and the observed sizes of the PCR products were automatically compared to the expected sizes. All information related to problematic reactions (wrong size, contamination, or missing bands) was used to redesign oligonucleotides. This information was also used as a reference to check the quality of hybridization at a later stage. After two rounds of PCR, about 95% of the reactions were successful and the remaining ORFs were amplified with another set of oligonucleotides. If an ORF was larger than 3 kb, only a portion of the gene (2 kb or less) was amplified. A total of 4,020 PCR products were obtained. These PCR products were spotted onto sodium thiocyanate-optimized type-6 slides (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) with the Generation III spotter (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Each of the 4,020 PCR products was spotted in duplicate on a single slide.

RNA isolation, labeling, and slide hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from B. subtilis with the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit. Cells grown to exponential phase were suspended directly in lysis buffer and placed in a 2-ml tube with ceramic beads from the FastRNA kit (Bio101, Vista, Calif.). The tube was shaken for 40 s at the speed setting of 6.0 in a bead beater (FP120 FastPrep cell disrupter; Savant Instruments, Inc., Holbrook, N.Y.). Residue DNA was removed on-column with Qiagen RNase-free DNase. To generate cDNA probes with reverse transcriptase, 10 to 15 μg of RNA was used for each labeling reaction. The protocol for labeling was similar to the one previously described for yeast (6). For this work, random hexamers (Gibco BRL) were used for priming and the fluorophor Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was used for labeling. After the labeling, RNA was removed by NaOH treatment and cDNA was immediately purified with a Qiagen PCR Mini kit. The efficiency of labeling was routinely monitored by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm (for DNA concentration), 550 nm (for Cy3), or 650 nm (for Cy5).

Each total RNA preparation was labeled with both Cy3-dCTP and Cy5-dCTP. To hybridize a single glass slide, the Cy3-dCTP-labeled probe from one growth condition was mixed with the Cy5-dCTP-labeled probe from another and vice versa. As a result, each experiment required two slides. An equal amount of Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP-labeled probe, based on the incorporated dye concentration, was applied to each slide. The hybridization was carried out at 37°C overnight with Microarray hybridization buffer containing formamide (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Slides were washed at 15-min intervals, once with a solution containing 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 37°C and three times with a solution containing 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS at room temperature. The slides were then rinsed with 0.1× SSC and distilled water. After drying under a stream of N2, the slides were scanned for the fluorescent intensity of both the Cy5 and Cy3 fluors. The signal from each spot in the array was quantified using ArrayVision software from Molecular Dynamics.

Construction of resDE mutant.

The 1.1-kb SphI and KpnI fragment was amplified with the primers GCATACATGCATGCCATTTCATCACAAGGTGGGCTGC and ATCGGGGTACCGCTTCGTCATCAACTACTAAT and cloned into the same restriction sites downstream of the chloramphenicol resistance marker of a pBR322 derivative. The 0.78-kb BamHI and XhoI fragment in the resE region was amplified with primers ATCGCGGATCCTGCGGAATCGCACGTCAGAG 3′ and ATCCGCTCGAGAGATTCTTCGGCAAATTCAG and cloned into a site upstream of the chloramphenicol resistance marker. The resulting construct was linearized and introduced into the B. subtilis JH642 strain by transformation. The resDE mutant strain was designated RY106. In this mutant strain, 0.67 kb of resD and 1.0 kb of resE were deleted and replaced by the chloramphenicol resistance cassette.

RESULTS

Construction of B. subtilis DNA microarrays for global gene expression profiling.

B. subtilis can grow under anaerobic conditions, either with nitrate or nitrite as the electron acceptor or by fermentation. In order to explore the gene expression profiles of B. subtilis grown under these conditions, 4,020 out of 4,100 possible ORFs in the genome were amplified and arrayed individually on glass slides. Total RNA isolated from an aerobic or anaerobic culture was labeled with the fluorescent dyes Cy3-dCTP and Cy5-dCTP. The Cy3-dCTP- and Cy5-dCTP-labeled probes from two samples to be compared were combined and hybridized to the same slide. The fold induction or repression in gene expression level was represented by the fluorescence intensity ratio of these two dyes in the individual spot. Among the 4,020 genes studied, the narGHJI locus, which encodes the membrane-bound nitrate reductase, was the most highly induced region (Table 1). The fnr gene, which encodes the anaerobic regulator, had a fold induction value of approximately 100. A lower-fold induction level (range, 8 to 40) was observed for the nitrite reductase region, nasDEF, during anaerobic growth on nitrate or nitrite. As expected, no induction was observed for the nar genes with fnr mutant strain THB2 grown under oxygen-limiting conditions (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Induction of genes involved in nitrate and nitrite respiration in B. subtilis JH642 grown under anaerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Description | Induction (fold)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate respiration | Nitrite respiration | Fermentation | ||

| narG | Nitrate reductase (alpha subunit) | 398.8 | 488.9 | 275.5 |

| narH | Nitrate reductase (beta subunit) | 636.6 | 743.4 | 430.8 |

| narJ | Assembling factor | 215.8 | 208.5 | 125.1 |

| narI | Nitrate reductase (gamma subunit) | 112.2 | 102.6 | 61.4 |

| narK | Nitrite extrusion protein | 137.8 | 136.8 | 110.9 |

| fnr | Global anaerobic regulator | 105.1 | 117.1 | 115.8 |

| hmpb | Flavohemoglobin | 137.1 | 166.2 | 4.6 |

| nasD | Subunit of NADH-dependent nitrite reductase | 39.8 | 38.6 | 15.3 |

| nasE | Subunit of NADH-dependent nitrite reductase | 16.9 | 15.0 | 3.9 |

| nasF | Cofactor; uroporphyrin-III C-methyltransferase | 9.9 | 9.0 | 2.4 |

| resD | Two-component response regulator | 4.5 | 6.8 | 5.7 |

| resE | Sensor kinase | 4.4 | 6.3 | 5.4 |

Cultures were grown in a buffered 2× YT medium with 1% glucose, as described in Materials and Methods. For anaerobic growth, 5 mM potassium nitrate or 2.5 mM potassium nitrite was used if needed. No pyruvate was added during fermentation growth. Total RNA was isolated from cells at exponential phase. The fold induction value was obtained by calculating the ratio of the dye intensity of the anaerobic sample to that of the aerobic sample. Each data point is an average of the results of four independent experiments. A ratio of 2.0 or below was not considered a significant increase.

Physiological function is not known.

Induction of genes involved in carbon metabolism.

Although fermentative growth on glucose is poor for B. subtilis, efficient growth can be obtained with the addition of pyruvate (18). The gene expression profiles related to carbon metabolism during fermentative growth on glucose with or without pyruvate addition were investigated (Table 2). Without the addition of pyruvate, expression of the lctP and lctE genes, which encode the l-lactate permease and l-lactate dehydrogenase, was increased by more than 100-fold compared to that in aerobic culture. These two genes were also induced under anaerobic conditions with the addition of pyruvate, but the level of induction was reduced. Under the same conditions, the expression level of the pdhAB region encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha and beta subunits was repressed by more than 20-fold. Only a slight repression was observed with pdhC and pdhD genes. This repression effect was alleviated by adding pyruvate to the growth medium, indicating that pyruvate was required for the full expression of the pdhABCD region.

TABLE 2.

Expression of genes involved in carbon metabolism of B. subtilis JH642 grown under anaerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Description | Induction or repression (fold)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate respiration | Nitrite respiration | Fermentation

|

|||

| −Pyruvate | +Pyruvate | ||||

| lctE | l-Lactate dehydrogenase | 1.7 | 12.8 | 150.9 | 4.8 |

| lctP | l-Lactate permease | 1.4 | 9.2 | 103.8 | 12.4 |

| alsD | Alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase | 8.2 | 16.5 | 45.1 | 11.1 |

| pdhA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1 alpha subunit) | (1.7) | (3.3) | (26.9) | (1.8) |

| pdhB | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1 beta subunit) | (1.4) | (2.8) | (26.9) | (1.9) |

| pdhC | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E2 subunit) | (1.3) | (2.0) | (3.2) | (1.4) |

| pdhD | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E3 subunit) | (1.2) | (1.5) | (2.4) | (1.1) |

| glpF | Glycerol uptake facilitator | (2.7) | (5.7) | (2.7) | (2.9) |

| glpK | Glycerol kinase | (2.6) | (6.9) | (6.4) | (4.5) |

| glpT | Glycerol-3-phosphate permease | (5.6) | (5.8) | (9.5) | (1.6) |

| glpQ | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | (7.5) | (5.8) | (9.6) | (2.2) |

The concentration of pyruvate was 1% when added. The fold induction was the ratio of the dye intensity of the anaerobic sample to that of the aerobic sample. The fold repression (values in parentheses) was the ratio of the dye intensity of the aerobic sample to that of the anaerobic culture. Each data point is an average of the results of four independent experiments. A ratio of 2.0 or below was not considered a significant increase. −Pyruvate, without pyruvate; +Pyruvate, with pyruvate.

When nitrite was used as the alternative electron acceptor, the lctP and lctE genes were induced at levels about 10-fold higher, and the mRNA level for the pdhAB region was slightly reduced. No significant change in expression level for these genes was found when nitrate was used.

The alsD gene encodes the acetolactate decarboxylase involved in conversion of pyruvate to acetoin (25). This enzyme is generally synthesized in detectable amounts only in cells that have reached the stationary phase. Under anaerobic conditions, however, the alsD gene was highly induced (Table 2). Interestingly, the glpTQ and glpFK regions involved in glycerol metabolism were repressed under anaerobic conditions.

Expression profiles of uncharacterized DNA regions.

Currently, a significant portion of the ORFs in the B. subtilis genome remains uncharacterized. With the DNA microarray, the mRNA levels of many uncharacterized ORFs were affected under anaerobic conditions (Table 3). One of the induced unknown genes was ydjL, which had an expression pattern similar to that of alsD. The gene product of ydjL is similar to the 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas putida (11) and the sorbitol dehydrogenase encoded by gutB, both of which belong to the zinc-containing superfamily of dehydrogenases. The induced uncharacterized gene ytkA is located upstream of the stress-response gene dps, whose mRNA level was also increased under anaerobic conditions (data not shown). The unknown region yolIJK is located downstream from the lantibiotic gene sunA (24). The gene product YolJ is similar to PlnO, containing a putative motif for aspartyl protease. The yolK and yolI genes encode proteins that have similarities to the disulfide bond oxidoreductase (disulfide bond formation protein) and thioredoxin. This suggests that the yolIJK region could potentially have a role in the processing of sublancin 168 lantibiotic precursor.

TABLE 3.

Expression profiles of unknown DNA regions of B. subtilis JH642 when grown under anaerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Similar protein or gene | Induction or repression (fold)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate respiration | Nitrite respiration | Fermentation

|

|||

| −Pyruvate | +Pyruvate | ||||

| ydjL | Sorbitol or 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase | 7.7 | 11.6 | 23.2 | 8.4 |

| yolI | Thioredoxin | 16.1 | 13.6 | 5.0 | 10.3 |

| yolJ | PlnO of Lactobacillus plantarum | 14.8 | 12.5 | 5.0 | 9.5 |

| yolK | Disulfide bond oxidoreductase | 6.1 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 3.6 |

| yclJ | Response regulator | 2.0 | 4.2 | 11.7 | 4.2 |

| yclK | Sensor histidine kinase | 2.5 | 5.0 | 13.7 | 5.0 |

| yxaK | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 13.9 | |

| yxaL | 16.0 | 15.8 | 18.8 | 19.5 | |

| yfmQ | 8.4 | 11.3 | 15.2 | 5.8 | |

| yncM | 4.0 | 6.4 | 21.5 | 7.4 | |

| ytkA | 6.6 | 12.7 | 16.6 | 10.5 | |

| ywfI | 4.6 | 7.8 | 13.0 | 5.6 | |

| ydhE | Macrolide glycosyltransferase | 4.0 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 2.7 |

| yxjG | 1.9 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 3.5 | |

| ywcJ | Putative formate or nitrite transporter | 2.4 | 6.7 | 52.7 | 7.6 |

| yumD | 1.1 | 3.6 | 30.2 | 1.1 | |

| ywiD | 11.6 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 1.8 | |

| ywiC | 8.0 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 3.1 | |

| yvyD | 3.8 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 4.8 | |

| yvaW | 5.4 | 7.0 | 4.5 | 20.6 | |

| yvaX | 5.8 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 17.1 | |

| yvaY | 8.9 | 8.1 | 5.3 | 24.0 | |

| ysfC | Flavoprotein of glycolate oxidase subunit (GlcD) and d-lactate dehydrogenase (cytochrome) | 11.7 | 24.8 | 19.8 | 1.2 |

| ysfD | [Fe-S] protein | 7.0 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 1.0 |

| yjdD | Fructose phosphotransferase system enzyme II | 5.2 | 4.8 | (3.6) | 3.9 |

| yjdE | Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | 5.4 | 4.7 | (3.1) | 3.7 |

| yjdF | 2.8 | 2.8 | (1.7) | 1.7 | |

| ykuN | Flavodoxin | 2.2 | 19.5 | (1.8) | 0.8 |

| ykuO | 1.8 | 20.0 | (3.6) | 1.0 | |

| ykuP | Flavodoxin | 2.0 | 18.1 | (2.4) | 0.9 |

| yukM | Antibiotic synthetase | 2.4 | 34.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| yukL | Antibiotic synthetase | 1.5 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| yvfV | [Fe-S] protein | (1.4) | (7.0) | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| yvfW | (1.6) | (8.0) | 1.1 | 1.5 | |

| yvbY | (1.4) | (5.3) | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| yjlC | Unknown | (7.2) | (7.1) | (9.4) | (3.6) |

| yjlD | NADH dehydrogenase | (6.5) | (5.9) | (6.8) | (3.1) |

| yxxG | (4.4) | (4.7) | (12.7) | (1.2) | |

| yxiF | (4.3) | (4.6) | (11.3) | (1.6) | |

| yxzC | (4.7) | (5.1) | (13.3) | (1.6) | |

| yxiG | (4.5) | (4.2) | (11.6) | (1.6) | |

| yxiH | (3.4) | (4.1) | (7.0) | (1.5) | |

| yxzG | (3.9) | (3.9) | (8.8) | (1.6) | |

| yxiI | (4.1) | (4.1) | (9.9) | (1.6) | |

| yxiJ | (3.1) | (3.9) | (5.9) | (1.5) | |

| yxiK | (3.5) | (4.4) | (7.0) | (1.9) | |

| yxiM | (3.0) | (4.2) | (5.7) | (1.9) | |

| yurY | ABC transporter | (2.5) | (2.6) | (6.7) | (1.7) |

| yurX | (2.6) | (2.5) | (6.9) | (1.9) | |

| yurW | NifS | (2.5) | (2.1) | (6.3) | (1.9) |

| yurV | NifU | (2.6) | (2.2) | (7.5) | (1.5) |

| yurU | (2.3) | (2.0) | (6.0) | (1.8) | |

| yclN | (3.0) | (1.8) | (5.6) | (2.7) | |

| yclO | ABC transporter | (3.8) | (1.2) | (8.9) | (2.3) |

| yclP | Ferrichrome ABC transporter | (3.7) | (1.3) | (10.5) | (2.7) |

| yclQ | (3.5) | (1.2) | (6.4) | (2.7) | |

| yfmC | Ferrichrome ABC transporter | (4.1) | (2.1) | (15.4) | (2.8) |

Transcriptional levels of some unknown genes, such as ywcJ, yumD, ykzH, ykjA, ysfC, and ysfD, were increased significantly under specific anaerobic conditions. Levels for ywcJ and yumD genes, for example, were increased by 30- or 50-fold under fermentative conditions in the absence of pyruvate. High mRNA levels for ykzH and ykjA genes were observed when the cells were grown on nitrate or nitrite. It is possible that the presence of nitrate or nitrite is required for the expression of these two genes. The ykzH and ykjA genes are located adjacent to hmp, and it is unclear whether their expression was due to the read-through of the hmp promoter. The ysfCD region was induced during respiration on nitrate and nitrite and during fermentation on glucose. No induction was found when pyruvate was added. The gene product YsfD is similar to proteins containing iron-sulfur clusters ([Fe-S] proteins), while YsfC is similar to one of the flavoprotein subunits of glycolate oxidase of Escherichia coli and to d-lactate dehydrogenase of yeast.

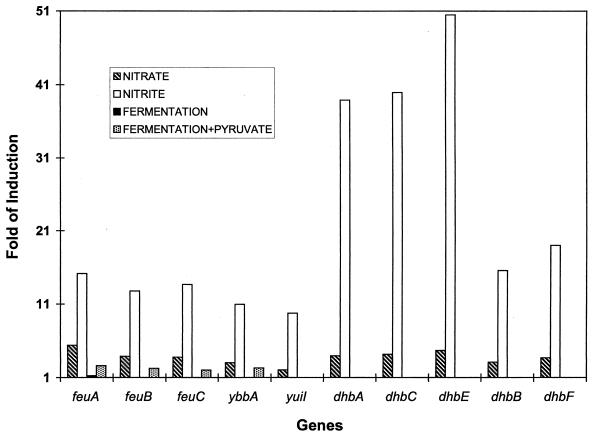

Respiration on nitrite specifically induced or repressed a group of unknown regions, including yvfVWY, ykuNOP, and yukML. The gene products YkuN and YkuP appear to be flavodoxins, which often serve as electron transport components. The yukM and yukL genes are located downstream from the dhb region, and their expression patterns were similar (Table 3 and Fig. 1). It is possible that they were regulated by the same promoter(s).

FIG. 1.

Expression of genes involved in iron uptake by B. subtilis JH642 grown under anaerobic conditions. The growth conditions were the same as those described in Table 1. The fold induction value was obtained by calculating the ratio of the dye intensity of the anaerobic sample to that of the aerobic sample. Each data point is an average of the results of four independent experiments.

The unknown regions yjlCD and yxxG-yxiM were found to be down-regulated during dissimilatory reduction of nitrate and nitrite and during fermentative growth without pyruvate. The change in mRNA levels for yxxG-yxiM was not significant when pyruvate was added. The yxxG-yxiM region is located downstream from wapA, which encodes a cell wall-associated protein precursor. The wapA gene had the same expression pattern as the yxxG-yxiM region (data not shown).

Induction of cytochrome genes.

The most highly induced cytochrome genes were those in the cydABCD region (Table 4), which is involved in the production of cytochrome bd oxidase (29). On the other hand, the induction for the qcrABC and qoxABCD regions was marginal. A modest induction for hemHYE, resABC, and some genes in the cta region was observed. Increases in transcriptional levels of these cytochrome genes were found in the fnr mutant THB2 (data not shown), suggesting that FNR was not essential for their expression.

TABLE 4.

Expression of genes involved in electron transport or cytochrome metabolism in B. subtilis JH641 grown under anaerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Description | Induction (fold)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate | Nitrite | Fermentation | ||

| cydA | Cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase (subunit I) | 5.4 | 27.8 | 62.2 |

| cydB | Cytochrome bd uniquinol oxidase (subunit II) | 16.1 | 40.0 | 78.4 |

| cydC | ABC membrane transporter (ATP-binding protein) | 16.5 | 61.2 | 104.4 |

| cydD | ABC membrane transporter (ATP-binding protein) | 19.6 | 59.4 | 74.2 |

| ctaA | Heme-containing membrane protein | 6.5 | 11.1 | 13.7 |

| ctaB | Cytochrome caa3 oxidase assembly factor | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 |

| ctaC | Cytochrome caa3 oxidase (subunit II) | 5.3 | 6.1 | 9.7 |

| ctaD | Cytochrome caa3 oxidase (subunit I) | 4.5 | 6.6 | 11.4 |

| ctaE | Cytochrome caa3 oxidase (subunit III) | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.3 |

| ctaF | Cytochrome caa3 oxidase (subunit IV) | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| ctaG | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | |

| hemH | Ferrochelatase | 6.3 | 8.3 | 13.8 |

| hemY | Protoporphyrinogen IX and coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | 6.2 | 8.1 | 12.1 |

| hemE | Uroporphyrinogen III decarboxylase | 5.2 | 8.3 | 12.5 |

| resA | Similar to cytochrome c biogenesis protein | 3.8 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| resB | Similar to cytochrome c biogenesis protein | 4.2 | 5.7 | 6.3 |

| resC | Similar to cytochrome c biogenesis protein | 4.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 |

| qcrA | Menaquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase (iron-sulfur subunit) | 3.6 | 3.7 | 2.6 |

| qcrB | Menaquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase (cytochrome b subunit) | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.0 |

| qcrC | Menaquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase (cytochrome bc subunit) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| qoxA | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit II) | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| qoxB | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit I) | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| qoxC | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit III) | 2.1 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| qoxD | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit IV) | 2.2 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

Growth conditions and data presentation are as described in Table 1. No pyruvate was added for fermentation growth.

Induction of genes involved in Fe uptake or transport.

The dhb region encodes enzymes responsible for the production of siderophore 2,3-dihydroxylbenzoate, which is produced under iron-limiting conditions so that the cell may acquire extracellular iron (26). During anaerobic respiration on nitrite, mRNA levels for genes in the dhbABCE region were increased by 10- to 50-fold compared to those observed for the aerobic culture (Fig. 1). A higher level of mRNA was also observed with iron uptake region feuABC. The induction level for the dhb region was lower during anaerobic growth on nitrate, while no induction was found with cells grown under fermentation conditions.

The fhuDBGC region encodes a ferrichrome uptake system in B. subtilis (27). The mRNA levels of this region were reduced by 3- to 10-fold during fermentative growth on glucose. Under the same conditions, the mRNA levels of yfmC and yclNOPQ, which encode proteins that may have ferrichrome uptake function, were also reduced (Table 3). These repression effects were alleviated by the addition of pyruvate.

Induction of genes involved in macrolide or antibiotic production.

During anaerobic growth, the mRNA levels for genes involved in the production of three types of antibiotics were increased (Table 5). Induction of the sbo-alb locus responsible for the production of the subtilosin A (1, 30) was increased by 4- to 90-fold. Induction of the sunA gene, which encodes a lantibiotic precursor (24), was 6- to 11-fold higher. Only a slight induction was found with a number of pks genes involved in macrolide biosynthesis during nitrate respiration, but levels were higher during respiration on nitrite or under fermentation conditions. The unknown gene ydhE, which encodes a protein similar to macrolide glycosyltransferase, was also induced (Table 3).

TABLE 5.

Expression of genes or DNA regions related to antibiotic production or polyketide biosynthesis in B. subtilis JH642 when grown under anaerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Description | Induction or repression (fold)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate respiration | Nitrite respiration | Fermentation

|

|||

| −Pyruvate | +Pyruvate | ||||

| sbo | Subtilosin A | 14.4 | 33.5 | 66.1 | 42.3 |

| albA | Similar to protein for PQQ synthesis | 21.4 | 42.8 | 91.3 | 38.6 |

| albB | 8.0 | 18.2 | 31.0 | 16.1 | |

| albC | Similar to ABC-type transporter | 8.9 | 15.0 | 37.0 | 18.8 |

| albD | 18.9 | 38.0 | 55.9 | 30.5 | |

| albE | 29.7 | 40.1 | 54.0 | 38.6 | |

| albF | Similar to processing peptidase beta subunit | 20.6 | 49.7 | 77.9 | 41.7 |

| albG | 4.7 | 14.2 | 26.9 | 8.0 | |

| sunA | Sublancin 168 lantibiotic precursor | 8.8 | 11.5 | 6.1 | 7.7 |

| pksB | Polyketide biosynthesis | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 2.4 |

| pksC | 2.7 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 6.1 | |

| pksD | 3.7 | 10.1 | 21.8 | 11.2 | |

| pksE | 2.2 | 6.1 | 9.0 | 3.9 | |

| pksF | 1.9 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 6.1 | |

| pksG | 2.2 | 7.7 | 4.6 | 9.1 | |

| pksH | 1.6 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 6.0 | |

| pksI | 1.9 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 7.3 | |

Gene expression profiles of resDE mutant.

Since the resDE mutant cannot grow on nitrate or nitrite under anaerobic conditions, mRNA levels from both wild-type and mutant strains induced under oxygen-limiting conditions without the presence of nitrate or nitrite were compared. It has been reported that expression of resABCDE, qcrABC, narGHJI, ctaABCD, nasDEF, hmp, and sbo-alb is regulated by ResDE (15, 16, 21, 28, 30). Similar observations were made with DNA microarrays (Table 6). In this experiment, the levels of mRNA for narGHJI in the resDE mutant were 37- to 53-fold lower than those in the wild type. Yet, significant amounts of mRNA for these genes were present in the mutant strain after anaerobic induction (data not shown). The same phenomenon was found with the narK and fnr genes. Only background levels of mRNA signals for these nar genes were, however, detected in the fnr mutant strain THB2. The array data also showed that mRNA levels for qoxABCD and hemEHY in the resDE mutant strain were reduced compared to those in the wild type (Table 6). Furthermore, the resDE mutation affected the mRNA levels of a number of other genes, including sunA, yolI, yolJ, yfmQ, ytkA, yxaL, yxaK, ywcJ, yvyD, and yncM. Expression of lctE and alsSD was increased in both wild-type and mutant strains under oxygen-limiting conditions, but the extent of induction was reduced in the resDE mutant. No difference in mRNA levels was observed for the cydABCD region.

TABLE 6.

Difference in mRNA levels between the wild-type and resDE mutant strains after anaerobic induction in the absence of nitrate and nitritea

| DNA | Difference in mRNA level (fold)b |

|---|---|

| narG | 37.9 |

| narH | 53.0 |

| narJ | 50.4 |

| narI | 41.4 |

| ywiC | 2.3 |

| ywiD | 4.8 |

| narK | 6.4 |

| fnr | 8.5 |

| nasD | 27.7 |

| nasE | 6.5 |

| nasF | 7.9 |

| hmp | 40.5 |

| cydA | 0.8 |

| cydB | 0.8 |

| cydC | 0.8 |

| cydD | 0.7 |

| ctaA | 19.6 |

| ctaB | 3.8 |

| ctaC | 3.2 |

| qoxA | 4.5 |

| qoxB | 4.1 |

| qoxC | 6.5 |

| qoxD | 3.5 |

| resA | 6.3 |

| resB | 8.4 |

| resC | 5.4 |

| hemE | 7.5 |

| hemH | 8.1 |

| hemY | 5.3 |

| lctE | 3.9 |

| alsS | 5.5 |

| alsD | 5.8 |

| sunA | 3.1 |

| yolI | 4.0 |

| yolJ | 3.7 |

| sbo | 9.9 |

| yfmQ | 15.5 |

| ytkA | 12.3 |

| dps | 7.6 |

| ywfI | 4.4 |

| ywcJ | 18.3 |

| yxaK | 4.4 |

| yxaL | 5.1 |

| yncM | 6.1 |

| yvyD | 6.8 |

| yckF | 5.1 |

| yckG | 5.1 |

| yjdD | 19.8 |

| yjdE | 6.8 |

| yjdF | 2.4 |

The wild-type and mutant cultures were placed in serum bottles with Teflon-coated stoppers when the aerobic cultures reached an OD at 600 nm of approximately 0.3. Oxygen-limiting conditions were obtained by sparging the bottles with argon gas for 2 min. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm). Total RNA was isolated after 2 h of induction. No nitrate or nitrite was added.

Data are ratios of the dye intensity of the wild-type strain to that of the mutant strain. Each data point is an average of the results from three independent experiments. A ratio of 2.0 or below was not considered a significant increase.

When the expression profiles were compared with those of cells induced under anaerobic conditions in the presence of nitrate, a drastic reduction in transcription levels of the pdhABCD region was found in the mutant but not in the wild type (data not shown). A reduction in pdhABCD expression reflects the inability of the resDE mutant to utilize nitrate or nitrite as an electron acceptor under anaerobic conditions.

The DNA microarrays were also used to investigate changes in gene expression patterns in the resDE mutant strain during exponential growth under aerobic conditions (Table 7). The mRNA levels of cydABCD were increased, and expression of a group of genes including lctP, lctE, alsS, alsD, glpD, mtlD, yrhG, yrhE, yrhD, yjlC, and yjlD appeared to be slightly elevated. These genes encode proteins that are involved or possibly involved in carbon metabolism and the production of acids. This observation is consistent with a previous report stating that the resDE mutant accumulates elevated levels of cytochrome b and acids (28).

TABLE 7.

Genes that showed increases in mRNA levels in resDE mutant grown under aerobic conditionsa

| Gene | Description | Induction (fold) |

|---|---|---|

| cydD | 12.0 | |

| cydC | 9.8 | |

| cydB | 5.3 | |

| cydA | 5.4 | |

| yrhG | Similar to formate dehydrogenase | 9.9 |

| yrhE | Similar to formate dehydrogenase | 5.6 |

| yrhD | Unknown | 3.8 |

| lctP | 6.6 | |

| lctE | l-Lactate dehydrogenase | 2.9 |

| alsS | Acetolactate synthase | 2.7 |

| alsD | 2.6 | |

| glpD | Glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) dehydrogenase | 4.3 |

| mtlD | Mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase | 5.3 |

| yjlC | Unknown | 3.4 |

| yjlD | Similar to NADH dehydrogenase | 3.4 |

Mutant and wild-type strains were grown under aerobic conditions to the exponential phase. Total RNAs from these two strains were labeled with either Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP. The probes were then combined and hybridized to the same slide. The fold induction was the ratio of the dye intensity of the mutant to that of the wild-type strain. (Data are averages from at least three independent experiments.)

DISCUSSION

A genome-wide comparison of the gene expression profiles of aerobic and anaerobic cultures of B. subtilis during exponential growth in 2× YT rich medium revealed that many genes were differentially expressed. During dissimilatory reduction of nitrate, the most highly induced genes or regions were narGHJI, narK, fnr, and hmp, followed by nasDEF, cydABCD, sbo-alb, ywiD, and ywiC. Other induced genes or regions included hemHYE, resABCDE, ctaABCDEFG, alsSD, ydjL, ywcJ, sunA, ywfI, yfmQ, ydbN, and many others. At the same time, expression of a few DNA regions such as glpTQ, glpFK, yjlCD, and yxxG-yxiM was reduced (Tables 2 and 3). During dissimilatory reduction of nitrite, similar gene expression patterns were observed. In addition, the dhbACEB cluster that is involved in iron uptake or transport and the unknown regions ykuNPO and yukML were highly induced (Table 3 and Fig. 1). During the inefficient fermentative growth on glucose, expression of a broad spectrum of genes was affected. A reduction in pdhAB expression and a dramatic increase in lctPE expression (Table 2) may be the signature gene expression profile of this anaerobic condition. Furthermore, many ribosomal genes involved in protein biosynthesis were repressed (data not shown), probably reflecting reduced protein biosynthesis due to a slower growth rate. Poor fermentative growth on glucose is likely caused by a lack of pyruvate production under anaerobic conditions (18). With the addition of pyruvate, repression of pdhAB and a few other genes was alleviated (Tables 2 and 3).

The DNA microarray data showed that many genes with unknown functions were induced under anaerobic conditions. One of the unknown genes was ydjL, which had an expression pattern similar to that of the alsSD operon that is involved in the conversion of pyruvate to acetoin (Table 2). Whether YdjL has the 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase activity as suggested by protein sequence similarity needs to be further investigated. Another uncharacterized region, yolIJK, was located downstream from the sunA gene encoding a lantibiotic peptide (24). Both the sunA gene and yolIJK region were induced under anaerobic conditions. The possible role of yolIJK in the processing of lantibiotic sublancin 168 has yet to be determined. It is apparent that genetic and biochemical studies are essential to validate hypotheses generated by DNA microarrays.

There have been reports that a significant number of genes are induced under anaerobic conditions as well as at the stationary phase. The sbo-alb operon is induced under anaerobic conditions and during the stationary phase (21, 30). The same observation has also been made with the alsSD region (Table 2) (16, 25). These results indicate that anaerobic metabolism and stationary growth share some similarities in regulatory circuits.

It has been reported that ResDE regulates the expression of genes involved in carbon metabolism, aerobic and anaerobic respiration, and antibiotic production (16, 21, 23, 28). The DNA microarray experiment revealed that in the mutant strain mRNA levels of many genes in addition to those listed in Table 6 were reduced compared to those in the wild type after anaerobic induction in the absence of nitrate or nitrite. Results obtained by DNA microarray alone, however, cannot determine which genes are directly regulated by ResDE. It is possible that lower levels of transcription for many of these genes are simply due to the pleiotrophic effects of resDE mutation.

Three types of terminal oxidases have been found in B. subtilis: aa3, caa3, and bd. The presence of multiple respiratory mechanisms and their differential expression under different conditions is believed to be advantageous in coping with changes in oxygen and nutrient availability. In E. coli, the cytochrome d oxidase has a higher affinity for oxygen than the cytochrome o oxidase complex, and it accumulates as oxygen becomes limiting (3, 4). Expression of the cydAB genes is controlled by both the ArcA/ArcB two-component regulatory system and FNR. In B. subtilis, neither the ResDE nor the FNR regulator was essential for the expression of the cyd region since this region was induced under anaerobic conditions in the fnr mutant THB2 (data not shown) and resDE mutant strain RY106 (Table 6). This result indicates that regulation of the cydABCD region depends on another regulator(s) that may sense the oxygen level, substrate availability, or electron flow. The ResDE mutant lacks the production of cytochrome aa3 which is required for the biosynthesis of both cytochrome caa3 and cytochrome aa3 oxidases (28). An increase in expression of cyd genes in aerobic culture of resDE mutant (Table 7) suggests that the cytochrome bd complex may be needed to compensate for the lack of terminal oxidases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steve Fahnestock, Vasantha Nagarajan, Mike Bramucci, and Jean-Francois Tomb for their support and technical help, Michiko Nakano and Peter Zuber for sharing their unpublished results, and Harry Taber for his insights in respiratory chains of B. subtilis.

ADDENDUM

During the preparation of the manuscript, Marino et al. (17) found that synthesis of the YwfI protein was increased under anaerobic conditions, while amounts of Yj1D and G1pK were decreased. Meanwhile, Nakano et al. (21) and Zheng et al. (30) demonstrated that the sbo-alb operon was induced under anaerobic conditions and regulated by both ResDE and Spo0.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babasaki K, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Kurahashi K. Subtilosin A, a new antibiotic peptide produced by Bacillus subtilis 168: isolation, structural analysis, and biogenesis. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1985;98:585–603. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengtsson J, Rivolta C, Hederstedt L, Karamata D. Bacillus subtilis contains two small c-type cytochromes with homologous heme domains but different types of membrane anchors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26179–26184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook G M, Membrillo-Hernandez J, Poole R K. Transcriptional regulation of the cydDC operon, encoding a heterodimeric ABC transporter required for assembly of cytochromes c and bd in Escherichia coli K-12: regulation by oxygen and alternative electron acceptors. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6525–6530. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6525-6530.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotter P A, Melville S B, Albrecht J A, Gunsalus R P. Aerobic regulation of cytochrome d oxidase (cydAB) operon expression in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA in repression and activation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:605–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5031860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz Ramos H, Boursier L, Moszer I, Kunst F, Danchin A, Glaser P. Anaerobic transcription activation in Bacillus subtilis: identification of distinct FNR-dependent and -independent regulatory mechanisms. EMBO J. 1995;14:5984–5994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeRisi J L, Iyer V R, Brown P O. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansson M, Hederstedt L. Cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis hemEHY gene cluster, which encodes protoheme IX biosynthetic enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8081–8093. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8081-8093.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann T, Frankenberg N, Marino M, Jahn D. Ammonification in Bacillus subtilis utilizing dissimilatory nitrite reductase is dependent on resDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:186–189. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.186-189.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann T, Troup B, Szabo A, Hungerer C, Jahn D. The anaerobic life of Bacillus subtilis: cloning of the genes encoding the respiratory nitrate redutase system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homuth G, Rompf A, Schumann W, Jahn D. Transcriptional control of Bacillus subtilis hemN and hemZ. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5922–5929. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5922-5929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang M, Oppermann F B, Steinbuchel A. Molecular characterization of the Pseudomonas putida 2,3-butanediol catabolic pathway. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiley P J, Beinert H. Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: the role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knappe J. Anaerobic dissimilation of pyruvate. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A E A. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaCelle M, Kumano M, Kurita K, Yamane K, Zuber P, Nakano M M. Oxygen-controlled regulation of flavohemoglobin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3803–3808. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3803-3808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Taber H W. Catabolite regulation of the Bacillus subtilis ctaBCDEF gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6154–6163. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6154-6163.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marino M, Hoffmann T, Schmid R, Mobitz H, Jahn D. Changes in protein synthesis during the adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to anaerobic growth conditions. Microbiology. 2000;146:97–105. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano M M, Dailly Y P, Zuber P, Clark D P. Characterization of anaerobic fermentative growth of Bacillus subtilis: identification of fermentation end products and genes required for growth. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6749–6755. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6749-6755.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano M M, Hoffmann T, Zhu Y, Jahn D. Nitrogen and oxygen regulation of Bacillus subtilis nasDEF encoding NADH-dependent nitrite reductase by TnrA and ResDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5344–5350. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5344-5350.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano M M, Hulett F M. Adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to oxygen limitation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano M M, Zheng G, Zuber P. Dual control of sbo-alb operon expression by the Spo0 and ResDE systems of signal transduction under anaerobic conditions in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3274–3277. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3274-3277.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano M M, Zuber P. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis) Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano M M, Zuber P, Glaser P, Danchin A, Hulett F M. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3796–3802. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3796-3802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paik S H, Chakicherla A, Hansen J N. Identification and characterization of the structural and transporter genes for, and the chemical and biological properties of, sublancin 168, a novel lantibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis 168. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23134–23142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renna M C, Najimudin N, Winik L R, Zahler S A. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis alsS, alsD, and alsR genes involved in post-exponential-phase production of acetoin. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3863–3875. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3863-3875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowland B M, Grossman T H, Osburne M S, Taber H W. Sequence and genetic organization of a Bacillus subtilis operon encoding 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate biosynthetic enzymes. Gene. 1996;178:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider R, Hantke K. Iron-hydroxamate uptake systems in Bacillus subtilis: identification of a lipoprotein as part of a binding protein-dependent transport system. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun G, Sharkova E, Chesnut R, Birkey S, Duggan M F, Sorokin A, Pujic P, Ehrlich S D, Hulett F M. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1374–1385. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1374-1385.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winstedt L, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, von Wachenfeldt C. Cytochrome bd biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of the cydABCD operon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6571–6580. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6571-6580.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng G, Yan L Z, Vederas J C, Zuber P. Genes of the sbo-alb locus of Bacillus subtilis are required for production of the antilisterial bacteriocin subtilosin. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7346–7355. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7346-7355.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]