Abstract

Introduction

Benign liver tumours and cysts (BLTCs) comprise a heterogeneous group of cystic and solid lesions, including hepatic haemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma. Some BLTCs, for example, (large) hepatocellular adenoma, are at risk of complications. Incidence of malignant degeneration or haemorrhage is low in most other BLTCs. Nevertheless, the diagnosis BLTC may carry a substantial burden and patients may be symptomatic, necessitating treatment. The indications for interventions remain matter of debate. The primary study aim is to investigate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of patients with BLTCs, with special regards to the influence of invasive treatment as compared with the natural course of the disease.

Methods and analysis

A nationwide observational cohort study of patients with BLTC will be performed between October 2021 and October 2026, the minimal follow-up will be 2 years. During surveillance, a questionnaire regarding symptoms and their impact will be sent to participants on a biannual basis and more often in case of invasive intervention. The questionnaire was previously developed based on PROs considered relevant to patients with BLTCs and their caregivers. Most questionnaires will be administered by computerised adaptive testing through the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Data, such as treatment outcomes, will be extracted from electronic patient files. Multivariable analysis will be performed to identify patient and tumour characteristics associated with significant improvement in PROs or a complicated postoperative course.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was assessed by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen and the Amsterdam UMC. Local consultants will provide information and informed consent will be asked of all patients. Results will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Study registration

NL8231—10 December 2019; Netherlands Trial Register.

Keywords: hepatobiliary surgery, hepatobiliary tumours, hepatobiliary disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The BELIVER study will lead to an expansion of the current knowledge on patient-reported outcomes in patients with benign liver tumours and cysts (BLTCs) in the Netherlands and the influence of interventions hereupon.

The long-term, biannual follow-up and increased frequency of questionnaires postoperatively will provide data to enable professionals to better inform patients what to expect and to enable patients and professionals to make well-informed treatment decisions together.

As the study is conducted nationwide, the extent of medical practice variation regarding management of BLTCs can be assessed.

Questionnaires are continued even after cessation of medical follow-up, which may introduce disease burden but may just as well be a confirmation of well-being for patients.

Patient burden is minimised through use of questionnaires using computerised adaptive testing.

Introduction

Benign liver tumours and cysts (BLTCs) comprise a heterogeneous groups of cystic and solid lesions.1 Although extensive research has been performed in the field of BLTCs, their natural course including their influence on patient reported outcomes (PROs) has been underexposed. The most common and relevant cystic lesions are simple non-parasitic liver cysts (estimated incidence of 18%) and ‘cystadenomas’ (1%–5% of all liver cysts),2 now referred to as mucinous cystic lesions of the liver and biliary system and intraductal papillary neoplasms of the liver and bile ducts (MCNs and IPNBs). Solid lesions include hepatic haemangioma (0.4%–20%), focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH, 0.4%–3%) and hepatocellular adenoma (HCA, 0.001%–0.004%).3–6

Many BLTCs are found incidentally on routine imaging for unrelated pathology.3 7 The rising incidence of those so-called incidentalomas is at least partly attributable to the increasing use of non-invasive imaging modalities.2 Main complications of BLTCs are bleeding and malignant transformation—both of which rarely occur.8 9 Of the five most common and relevant solid and cystic lesions, only (large) HCAs and ‘cystadenomas’ have a known risk of malignant transformation.9 Treatment indications remain an important matter of debate. In general, treatment of BLTCs is only recommended when they either have a risk of complications or cause severe complaints often with associated impairment of quality of life. When little or no risk of complications is present, the latter is often the sole indication for treatment.3

However, this recommendation has various nuances, which hampers shared decision and makes the management of BLTCs exceptionally prone to undesirable practice variation.10 11 First, the influence of treatment on PROs is important but rarely reported.12 Second, in the current literature, PROs after treatment by surgery or interventional radiology are rarely compared with conservative management.12 13 Finally, variations in diagnostic methods may be present, for example, FNH is easily misdiagnosed as HCA when inadequate diagnostics are applied.3 14 15

Therefore, this observational cohort study aims to investigate the PROs of patients with BLTCs during their natural courses as well as after treatment. These data will enable patients and professionals to make well-informed treatment decisions together to optimise value-based outcomes. In addition, the study will provide an overview of the clinical practice in the Netherlands.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The BELIVER study (Natural Course and Clinical Outcome in BEnign LIVER tumours and Cysts) is an investigator-initiated, nationwide, multicentre observational cohort study. All Dutch medical centres treating patients with BLTCs are eligible for participation, facilitated and coordinated through the Dutch Benign Liver Tumor Group (DBLTG) network. The study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register. Reporting of the study protocol and, eventually, of the full study is done according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2021-055104supp001.pdf (140.4KB, pdf)

Study population

Adult patients (≥18 years old) presenting with a common and/or clinically relevant BLTC at participating centres are eligible for inclusion. Clinically relevant BLTCs are defined as all BLTCs potentially eligible for either surgical intervention or follow-up. Strict cut-off values regarding BLTC size will not be defined and are assessed on a per patient basis by treating professionals.

The study will be conducted from October 2021 till October 2026, the minimal follow-up will be 2 years. Patients diagnosed with an uncommon BLTC, unwilling or unable to provide written informed consent or to fill in the questionnaire and patients with another disease substantially affecting PROs, will be excluded. Uncommon BLTCs and clinically less relevant are excluded. These include choledochal cysts, hepatic angiomyolipoma and biliary hamartoma/Von Meyenburg complexes.16 Additionally, patients with polycystic liver disease are excluded as they form a circumscript group of patients with very typical symptoms and treatments, including liver transplantation and they are currently already included in another international study.17

Study objectives and outcomes

The primary study objective is to systematically record the PROs during the natural course and after (minimally) invasive treatment of patients with BLTCs. Secondary study objectives are to evaluate changes in tumour/cyst diameter and the occurrence of any mortality and complications, related to either the natural course of the disease (malignant transformation or haemorrhage) or related to tumour or cyst treatment. The study will also provide an overview of potential variation in management and outcomes of Dutch patients with BLTCs.

The primary study outcome measure is change in PROs including severity of symptoms from the start compared with the end of the follow-up period. Symptoms are measured by a questionnaire, focusing on PROs relevant to patients with BLTCs and their caregivers and partly administered through the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

The questionnaire is administered biannually. Although a multiplicity would have enabled a more accurate longitudinal study with correction for confounding events, increasing questionnaire frequency will also probably lead to a reduction of study adherence and result in an increased patient burden. Moreover, one might argue that continuing surveys even after cessation of medical follow-up may introduce disease burden that remind patients of their diagnosis. However, the biannual questionnaires may just as well be a confirmation of well-being for patients. In addition, currently some patients might be subjected to extended periods of follow-up even in the absence of this study as a consequence of practice variation.

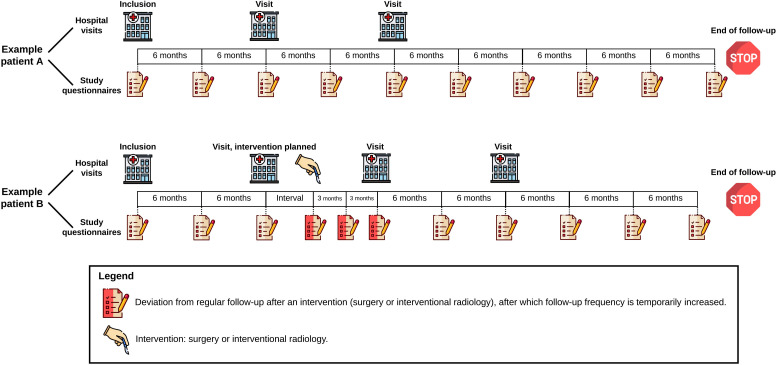

Secondary outcomes related to interventions include postoperative complications according to Clavien-Dindo Classification, the Comprehensive Complication Index, 30 and 90-day mortality and the Society of Interventional Radiology classification for adverse events.18–20 Treatment effects will be evaluated with additional questions regarding intervention indication, the effectiveness of the treatment on symptoms and the likeliness of patients to choose the treatment again. If surgical intervention is applied, questions on incisional herniation are added to the questionnaire after intervention. Supplementary questionnaires will be sent after interventions at 3, 6 and 12 months, thereafter resuming to biannual questionnaires. An example of two cases and their follow-up with questionnaires is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

An overview of the hospital visits and study questionnaires of two fictional patients included in the study are shown. In general, patients receive a questionnaire every 6 months. Deviations from this normal course of follow-up caused by patients undergoing an intervention are indicated by red questionnaires. Please note that these two patients were included around similar dates, but total follow-up durations might differ between patients depending on the date of inclusion.

In addition to data collected from questionnaires, data will be extracted from local electronic patient files. This includes the following data: (1) baseline patient characteristics (age, gender, comorbidity), (2) tumour or cyst characteristics (among which diameter, imaging and histopathological examination), (3) certain data specific for the type of BLTC the patient was diagnosed with and (4) details on the intervention performed. Table 1 summarises collected variables. All tumour and cyst diameters will be measured according to RECIST V.1.1 criteria.21

Table 1.

Overview of recorded variables

| Baseline information | Tumour or cyst specific questions | Treatment characteristics | ||||

| Patient characteristics | Tumour/cyst characteristics* | Solid lesions | Cystic lesions | Intervention | Surgery | Interventional radiology |

| Age | Total number of lesions at baseline | Focal nodular hyperplasia | Simple hepatic cysts | Date of intervention | Type of approach (open, laparoscopic, robot) | Type of procedure (aspiration sclerotherapy, TAE, RFA/MWA) |

| Sex | Location of lesion (left hemiliver, right hemiliver, bilobar) | Haemangioma | Mucinous cystic neoplasms | Duration of hospital stay | Occurrence and reason for conversion | Sclerotherapy (volume of aspiration, length of sclerosing, type of sclerosing agent) |

| Mortality If yes, reason |

Type of lesion | Hepatocellular adenoma | Intraductal papillary neoplasms | Operation or procedure time | Type of procedure (fenestration, wedge resection, segmental resection, hemihepatectomy, transplantation) | TAE (volume and type of embolisation agent(simple embolisation, chemo-embolisation or lipiodolisation)) |

| Comorbidity (ASA score and Elixhauser comorbidity index) | Diameter, date and modality of diagnosis | 30-day and 90-day mortality | Specification of resected segments | |||

| Diameter, date and modality of follow-up | Amount of blood loss | |||||

| Occurrence of misdiagnosis If so, revised diagnosis and diagnostic modality |

Additional procedures (eg, argon beam coagulation, omental transposition, concurring cholecystectomy) | |||||

| Histopathological diagnosis with immunohistochemistry if available | Complications (type, CD, CCI and SIR) | |||||

*According to RECIST V.1.1 criteria, lesions will only be measured on CT or MRI (longest diameter), measured on the transversal plane on post-contrast series. Maximum of two lesions. If the target lesion is not visible on follow-up imaging (index imaging is imaging shortest before inclusion), then the diameter of the next largest tumour will be measured.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CCI, comprehensive complication index; CD, Clavien-Dindo; MWA, microwave ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SIR, society of interventional radiologists classification for adverse events; TAE, transarterial embolisation.

Patient involvement and questionnaire selection

Various questionnaires have been used to evaluate PROs of patients with BLTCs. However, these questionnaires were not developed for the evaluation of outcomes of patients with BLTC and, therefore, most likely do not appropriately measure outcomes relevant to patients with BLTCs. Based on the literature and focus groups with patients with BLTCs and their caregivers, we selected relevant PROs. These were: insecurity/anxiety, pain, fatigue and limitations in daily life. The domains anxiety, fatigue, ability to participate and pain interference will be evaluated in the current study using computerised adaptive testing through the Dutch-Flemish PROMIS.22–24 PROMIS instruments have recently successfully been used in research on various patient groups.25 26 Additionally, numerical rating scales for pain (current and most, least, and average pain over a week) and two general health and quality of life questions will be assessed.

Data collection

Data will be collected using electronic case report forms using an online-based platform, which automatically generates patient identifiers consisting of the hospital code and a number. A subject identification log will be kept in each centre by the principal investigator or local coordinating investigator. This subject identification log will contain the personal details, which can be used to send questionnaires to patients. Only this dedicated person has the key for decoding patient data. At completion of the follow-up period, the database will be exported from the online platform. The database will be hosted on a secure server with the infrastructure, configuration and licenses that are consistent with current norms and laws to ensure safe and secure data storage and processing.

Sample size and statistical analysis

No sample size calculation was conducted as this is an observational cohort study. A previous single-centre prospective cohort study on the (conservative and surgical) treatment of HCAs and FNHs included 110 patients in 4.5 years.27 This current study has a broader scope as it spans across at least seven medical centres, includes more BLTC types and also includes patients treated by interventional radiological procedures. Therefore, the aim is to include at least 450 patients.

Statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS statistics for Windows V.24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) and R for Windows V.3.6.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Categorical data will be presented as proportions. Continuous data will be presented as mean and SD or median and IQR. Categorical variables will be compared using the Fisher exact test or the χ2 test. Continuous variables will be compared using the Mann-Whitney U test or the Student’s t test. Cox proportional hazards model will be used when appropriate. A two-tailed p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Scores for each PRO measure at the start and end of follow-up will be compared using a paired t test, and factors associated with significant gain in these measures will be evaluated. Patients will be stratified according to treatment strategy (conservative, surgical, transarterial (chemo-) embolisation and lipiodolisation, aspiration and sclerotherapy or radiofrequency or microwave ablation). Sensitivity analyses will be performed for the type of BLTC, and for the time between questionnaires and hospital visits, as hospital visits and imaging may increase the extent of the emotional burden experienced by patients. For surgically treated patients, predictors of a complicated course (Clavien Dindo ≥3 b) will also be evaluated.

Study sites

Initiating centres are Amsterdam UMC and University Medical Center Groningen. At least all other centres participating in the DBLTG will be included. Participating centres will at least include:

Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

In order to identify and/or avoid selection bias, non-DBLTG and non-academic centres will also be enabled to join during the course of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

This trial will be conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and as stated in the laws governing human research and Good Clinical Practice. The study does not interfere or change the process of treatment of the BLTCs in the included patients. The study was determined to be beyond the scope of the Dutch law on research on human subjects (Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen, WMO) according to the Medical Ethics Committee (MEC) of the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC (MEC AMC W19_134 # 19.167) and the MEC of the University Medical Center Groningen (MEC UMCG 201900292). The study will be evaluated by MECs of all participating centres. Moreover, the study will also be reviewed according to local requirements of each centre. Finally, the study proposal was reviewed by the scientific committee of the DBLTG. All substantial amendments will be notified to these committees and organisations. Data will be kept for at least 15 years after study completion.

Informed consent and withdrawal of consent

Informed consent for use of the questionnaires and the data collected from the electronic patient files will be obtained from all patients by the treating professional in participating centres. Information will be provided to patients by physicians. This will consist of both printed folders and links to digital information. A dedicated website has been created (URL: https://www.DBLTG.nl/BELIVER/). Also, dedicated e-mailboxes have been constructed.

Patients can withdraw from study participation at any time and without consequences or reason. With each questionnaire that is sent, it is noted that if patients wish to withdraw, they can do so at any time. In case of withdrawal, patients will be contacted and asked for allowance of data analysis until that point. There is no specific replacement of individual subjects after withdrawal. Patients who have chosen to withdraw from the study will receive follow-up and treatment according to current standard of care by their treating physician. If participants do not respond to questionnaires, a reminder will be sent after 1 month. If there is no reaction to this reminder, patients will be contacted by telephone to verify whether they still wish to participate or not.

Additional burden and risk associated with study participation

The proposed study does not interfere with standard patient care. No additional blood samples, increase in number of hospital visits, physical examination or other tests are indicated. However, in case of cessation of medical follow-up, patients included in the study will still receive questionnaires.

There are no direct benefits for patients participating in this study. There are no risks involved with participating in this study. The additional burden of the study is considered to be minimal. Completion of the questionnaire will take approximately 15 min. The questionnaires might remind patients of their BLTC diagnosis. Some of the questions might be confronting (ie, questions regarding the impact of complaints on daily life and work).

Administrative aspects, monitoring and publication

All results, either positive or negative, will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. All results will be reported suiting reporting guidelines provided by the EQUATOR-network (URL: https://www.equator-network.org/). All Dutch centres collaborating in the DBLTG will be invited to participate in this study. All results originating from this study will be published on behalf of the DBLTG. Coauthorship is available for one physician at each centre supplying at least five cases and for two physicians at each centre supplying at least 10 cases. In each centre, it may be decided individually which one or two physicians will be mentioned as coauthors. Coauthorships may also be offered to persons who contributed substantially to the conceptualisation and execution of the study. All coauthorships will have to fulfil the international committee of medical journal editors regulations.28

In addition to these coauthorships, others involved may be listed as collaborator and the journal will be asked to list them as such also in MEDLINE/PubMed. For each centre supplying at least 30 cases, one collaborator may be included; for centres supplying at least 40 cases, two collaborators; for centres supplying 50 or more cases, three collaborators.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @MarcBesselink

Collaborators: Dutch Benign Liver Tumor Group (DBLTG): I D Munsterman, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud UMC, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. D Ramsoekh, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Amsterdam Gastroenterology Endocrinology Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit, The Netherlands. M D Doukas, Department of Pathology, Erasmus MC, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. J C Beckervordersandforth, Department of Pathology, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. C van der Leij, Department of Radiology, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. R Miclea, Department of Radiology, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. ETTL Tjwa, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud UMC, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. PB van den Boezem, Department of Surgery, Radboud UMC, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. JHW de Wilt, Department of Surgery, Radboud UMC, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. S van Koeverden, Department of Radiology, Radboud UMC, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. AE Braat, Department of Surgery, Leiden UMC, Leiden University, The Netherlands. MJ Coenraad, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Leiden UMC, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. SSLP Crobach, Department of Pathology, Leiden UMC, Leiden University, The Netherlands. S Feshtali, Department of Radiology, Leiden UMC, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. M C Burgmans, Department of Radiology, Leiden UMC, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. K P de Jong, Department of Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. T M van Gulik, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam Gastroenterology Endocrinology Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. R Swijnenburg, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam Gastroenterology Endocrinology Metabolism, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Contributors: AF, MPDH, BVvR, MGB, VEDM, JIE: conceptualisation of the study. MGB, RAdM, JNMIJ, MGJT, MK, MC, MET, AEB, RJdH, EWD, GK, OMvD, JV, RBT, FJCC: investigation and data curation. AF, MPDH, VEDM, JIE: drafting of the manuscript, study coordinators. BVvR, AJK, MGB, RAdM, JNMIJ, MGJT, MK, MC, MET, AEB, RJdH, EWD, GK, OMvD, JV, RBT, FJCC: methodology of the study, revision of the manuscript. AF, MPDH, BVvR, AJK, MGB, RAdM, JNMIJ, MGJT, MK, MC, MET, AEB, RJdH, EWD, GK, OMvD, JV, RBT, FJCC, VEDM, JIE: approval of the final manuscript. AF and MPDH share first authorship to this paper. VEDM and JIE share senior authorship to this paper.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Society of Gastroenterology (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Gastroenterologie) to the Dutch Benign Liver Tumor Group, and by a personal grant from Amsterdam UMC location AMC to A Furumaya.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Dutch Benign Liver Tumor Group (DBLTG):

ID Munsterman, D Ramsoekh, MD Doukas, JC Beckervordersandforth, C van der Leij, R Miclea, ETTL Tjwa, PB van den Boezem, JHW de Wilt, S van Koeverden, AE Braat, MJ Coenraad, SSLP Crobach, S Feshtali, MC Burgmans, TM van Gulik, R Swijnenburg, and KP de Jong

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Cristiano A, Dietrich A, Spina JC, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatic adenoma: current diagnosis and management. Updates Surg 2014;66:9–21. 10.1007/s13304-013-0222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marrero JA, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K, et al. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1328–47. 10.1038/ajg.2014.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) . EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol 2016;65:386–98. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishak KG, Rabin L. Benign tumors of the liver. Med Clin North Am 1975;59:995–1013. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)31998-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karhunen PJ. Benign hepatic tumours and tumour like conditions in men. J Clin Pathol 1986;39:183–8. 10.1136/jcp.39.2.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrim ZI, Murchison JT. The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clin Radiol 2003;58:626–9. 10.1016/S0009-9260(03)00165-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charny CK, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, et al. Management of 155 patients with benign liver tumours. Br J Surg 2001;88:808–13. 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deneve JL, Pawlik TM, Cunningham S, et al. Liver cell adenoma: a multicenter analysis of risk factors for rupture and malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:640–8. 10.1245/s10434-008-0275-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stoot JHMB, Coelen RJS, De Jong MC, et al. Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenomas into hepatocellular carcinomas: a systematic review including more than 1600 adenoma cases. HPB 2010;12:509–22. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00222.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA 2010;304:903–4. 10.1001/jama.2010.1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ 2001;322:1297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Rosmalen BV, de Graeff JJ, van der Poel MJ, et al. Impact of open and minimally invasive resection of symptomatic solid benign liver tumours on symptoms and quality of life: a systematic review. HPB 2019;21:1119–30. 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamphues C, Engel S, Denecke T, et al. Safety of liver resection and effect on quality of life in patients with benign hepatic disease: single center experience. BMC Surg 2011;11:16. 10.1186/1471-2482-11-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Auer TA, Walter-Rittel T, Geisel D, et al. HBP-enhancing hepatocellular adenomas and how to discriminate them from FNH in Gd-EOB MRI. BMC Med Imaging 2021;21:28. 10.1186/s12880-021-00552-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bieze M, van den Esschert JW, Nio CY, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in differentiating hepatocellular adenoma from focal nodular hyperplasia: prospective study of the additional value of gadoxetate disodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:26–34. 10.2214/AJR.11.7750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mezhir JJ, Fourman LT, Do RK, et al. Changes in the management of benign liver tumours: an analysis of 285 patients. HPB 2013;15:156–63. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00556.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Aerts RMM, Kievit W, de Jong ME, et al. Severity in polycystic liver disease is associated with aetiology and female gender: results of the International PLD registry. Liver Int 2019;39:575–82. 10.1111/liv.13965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khalilzadeh O, Baerlocher MO, Shyn PB, et al. Proposal of a new adverse event classification by the Society of interventional radiology standards of practice committee. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:1432–7. 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, et al. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg 2013;258:1–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alonso J, Bartlett SJ, Rose M, et al. The case for an international patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS®) initiative. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:210. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Terwee CB, Roorda LD, de Vet HCW, et al. Dutch-Flemish translation of 17 item banks from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Qual Life Res 2014;23:1733–41. 10.1007/s11136-013-0611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1179–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Meij E, Anema JR, Leclercq WKG, et al. Personalised perioperative care by e-health after intermediate-grade abdominal surgery: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:51–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wesselius HM, van den Ende ES, Alsma J, et al. Quality and quantity of sleep and factors associated with sleep disturbance in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1201–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bieze M, Busch ORC, Tanis PJ, et al. Outcomes of liver resection in hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia. HPB 2014;16:140–9. 10.1111/hpb.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. ICMJE recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals, 2014. Available: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-055104supp001.pdf (140.4KB, pdf)