Abstract

Molecular dynamic simulations are an effective tool to study complex molecular systems and are contingent upon the availability of an accurate and reliable molecular mechanics force field. The Drude polarizable force field, which allows for the explicit treatment of electronic polarization in a computationally efficient fashion, has been shown to reproduce experimental properties that were difficult or impossible to reproduce with the CHARMM additive force field, including peptide folding cooperativity, RNA hairpin structures, and DNA base flipping. Glycoproteins are essential components of glycoconjugate vaccines, antibodies, and many pharmaceutically important molecules, and an accurate polarizable force field that includes compatibility between the protein and carbohydrate aspect of the force field is essential to study these types of systems. In this work, we present an extension of the Drude polarizable force field to glycoproteins, including both N- and O-linked species. Parameter optimization focused on the dihedral terms using a reweighting protocol targeting NMR solution J-coupling data for model glycopeptides. Validation of the model include eight model glycopeptides and four glycoproteins with multiple N- and O-linked glycosylations. The new glycoprotein carbohydrate force field can be used in conjunction with the remainder of Drude polarizable force field through a variety of MD simulation programs including GROMACS, OPENMM, NAMD and CHARMM and may be accessed through the Drude Prepper module in the CHARMM-GUI.

Introduction

Atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of biomolecular systems have increasingly been part of biophysical studies to gather insights on various biological processes,1 including multiple studies targeting carbohydrates.2 The majority of MD studies to date have used empirical potential energy functions based on nonpolarizable, additive force fields due to the computational efficiency as well as availability. 3, 4 However, with the rapid improvements in the computational power and highly tailored algorithms we can now opt for higher accuracy in modeling of atomistic interactions, such as improved treatment of electrostatic interactions. To this end, there are multiple ongoing efforts to develop force fields that provide an explicit electronic polarization response. These include the AMOEBA model, the classical Drude oscillator model developed in our lab as well as other models developed in a number of laboratories.5, 6 Although requiring additional computational resources, polarizable force fields have proved that certain limitations of additive forces can be resolved by the explicit inclusion of polarizability.6, 7 Toward developing a comprehensive polarizable force field, we have extended the Drude force field to include parameters for carbohydrates,8–11 molecular ions,12, 13 small molecules,14 nucleic acids,15, 16 atomic ions,17 lipids,18 and proteins.19 Details of the Drude energy function, parametrization strategies, and methodological information have been reported in previous studies.12, 16, 20

Protein-carbohydrate interactions occur frequently in various biological processes such as metabolic activities, cell recognition and signaling, inflammation, among others.21 For example, enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass is the most abundant protein-carbohydrate interaction in nature that recycles carbon. In addition, protein-protein interactions are also mediated through glycosylated entities on either one or both the proteins, for example, playing important roles in the immune system.22 Simulations of glycosylated proteins using nonpolarizable force fields have already been performed in multiple studies to get better insights about catalytic mechanisms, binding specificities and kinetic and thermodynamic preferences.23 N- and O-linked glycosylations are the two most common types of glycosylation where the glycan is covalently linked to a protein via either the nitrogen of the Asn side chain (N-linked) or the oxygen of the Ser or Thr side chains (O-linked).

Post-translational protein modification by N-linked glycosylation, which occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum, plays a critical role in cell surface expression and is often required for protein stability and biological function.24 It has been found that N-linked glycosylation generally occurs at the sequence Asn-X-Ser/Thr, where X is any amino acid except proline.25 This type of glycosylation is found in nearly all eukaryotes,24 and in most cases the linkage occurs between Asn and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), replacing the alcohol moiety of GlcNAc C1 with an amide linkage to the Asn side chain. The O-glycosidic carbohydrate–protein bond is an important biological linkage present, for example, in mucin glycoproteins26 and as a post-translational modification for cytosolic proteins in signaling pathways.27 O-linkages do not have a preferred sequence motif. To allow for polarizable simulations of glycopeptides and glycoproteins, parameters for these linkages are required.

In this work, parameters for the glycosidic linkage between carbohydrates and proteins in the context of the Drude polarizable force field are developed and validated. The linkages build on the previously parametrized polysaccharides 9 to include N- or O-glycosidic linkages to proteins, thereby allowing the simulation of carbohydrates that are important in biomolecular function and molecular recognition. In addition to the parameter optimization and validation presented in this study, the newly developed parameters were applied to characterize the structure and properties of O-glycosidic linkages in the absence of restraint data, thereby indicating their utility in molecular modeling of larger glycoproteins.

Computational Methods

Model Systems

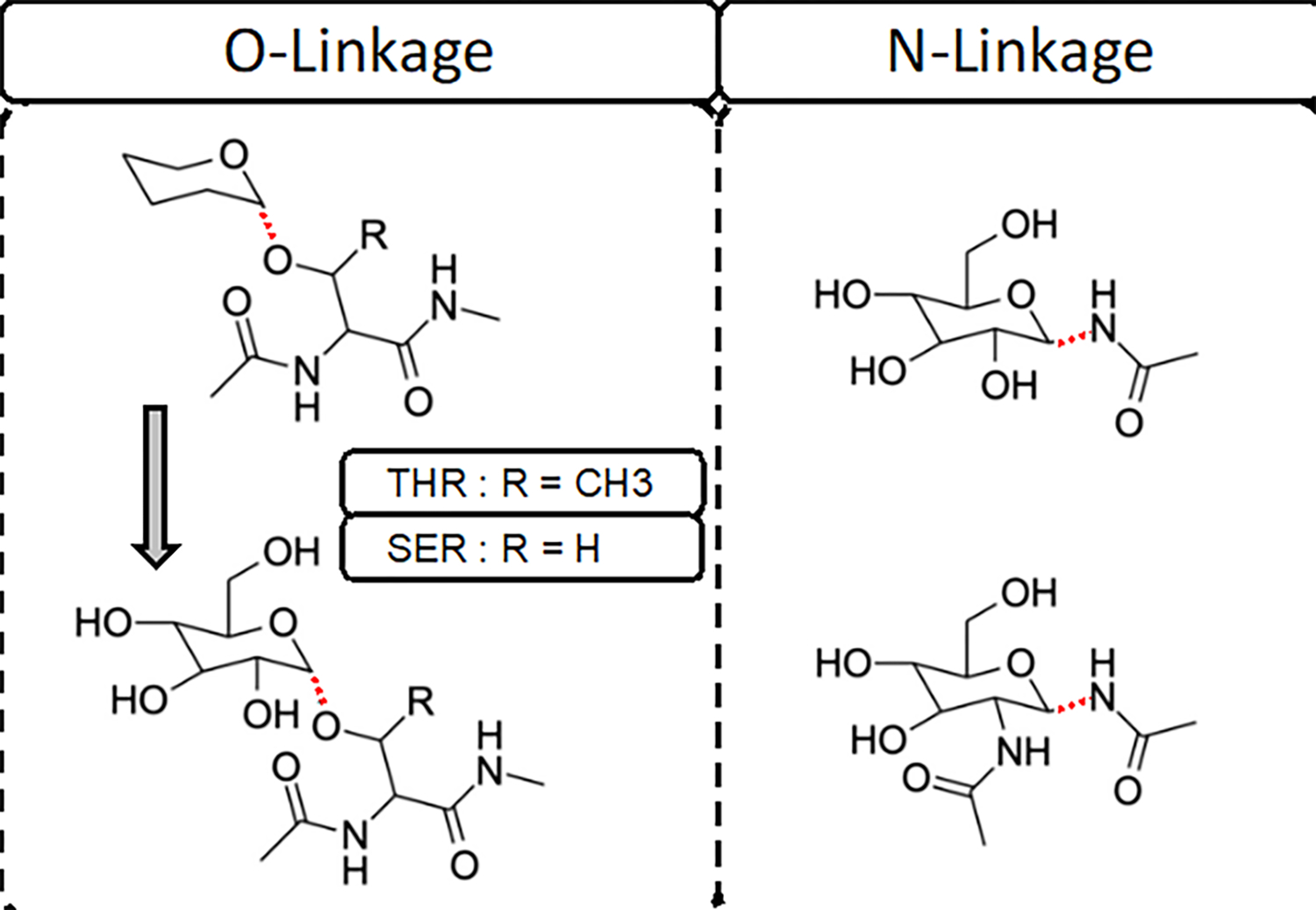

Model compounds with a hexopyranose monosaccharide connected to N-acetyls or dipeptides were selected for parametrization. For O-linked models both Ser and Thr dipeptides were used (Figure 1, left panel). For the N-linked parameters, parametrization was initiated with the previously parametrized N-acetylglucoseamine model compound11 with the N-acetyl group at the C1 position (Figure 1, top of right panel) or at both the C1 and C2 positions ((Figure 1, bottom of right panel). Quantum mechanical (QM) calculations were performed with the PSI428 and Gaussian 0329 programs. Adiabatic dihedral potential energy scans (PES) were performed by geometry optimization at the MP2/6–31G(d) model chemistry with the target dihedral constrained followed by RIMP2/cc-pVQZ single point energies (i.e., RIMP2/cc-pVQZ//MP2/6–31G(d) QM model chemistry). Analogous adiabatic MM PES were then computed with the target dihedral constrained to the QM values with the targeted dihedral parameter force constants set to zero.9 The energy difference between the MM and QM (MM-QM) PES was then targeted for the initial fitting of the dihedral parameters using the least squares fitting program developed in this laboratory specifically for use in parameter optimization.30 During fitting four multiplicities, n of 1, 2, 3, and 6, were included and the phase angle, δ, was limited to 0° and 180° as required to ensure applicability of the parameters to stereoisomers about a chiral center.

Figure 1.

Model compounds used in dihedral fitting of the O- and N-linkages. For O-linkage, an initial simple model compound based on THP-Thr/Ser without the hydroxyls on the hexopyranose ring was used (top of left panel) to perform the dihedral potential energy scans. Subsequently the full model compounds with the hydroxyls (bottom of left panel) were created based on conformations of the THP-based model compounds. Both α and β anomers of both the N- and O-glycan linkages were included explicitly in this study, therefore the linkages are represented with dotted line.

For validation eight O-linked model systems were selected based on availability of experimental data and previous studies using the additive CHARMM36 force field.31, 32 α and β conformers of N-acetylgalactosamine, β conformer of N-acetylglucosamine and β conformer of D-glucose sugars were built with a glycosidic linkage to both Ser and Thr dipeptides (Table S1). The systems were solvated in a 36 Å cubic water box. The Solution Builder and Drude Prepper modules in CHARMM-GUI were used to generate the simulation inputs for both nonpolarizable and polarizable systems.33, 34 Additionally, four glycoproteins with high glycosylation content were selected for bulk testing as shown in Table 1. The glycoproteins were also built using the CHARMM-GUI and were simulated in the NPT ensemble at 300 K for 500 ns each with the Drude FF using OpenMM 7.4.2. 35 Standard MD inputs from Drude Prepper were used to run the simulations.

Table 1.

Glycoprotein Systems and Their Glycosylation Sites.a

| PDB | SER residues with O-linkage | THR residues with O-linkage | ASN residues with N-linkage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1K7C 36 | - | - | 104 (CARB), 182 (CARA) |

| 1MYR 37 | - | - | 21(CARE), 90(CARF), 218(CARA), 244(CARG), 265(CARB), 292(CARC), 346(CARH), 361(CARD), 482(CARI) |

| 1RMG38 | 368(CARC), 373(CARK), 380(CART), 383(CARM), 400(CARN), 409(CARG), 418(CARH) | 367(CARS), 370(CARD), 371(CARQ), 372(CARL), 374(CARI), 376(CARP), 385(CARE), 386(CARR), 398(CARF), 405(CARJ), 408(CARO) | 32(CARA), 299(CARB) |

| 3GLY 39 | 443(CARC), 444(CARD), 453(CARE), 455(CARF), 459(CARI), 460(CARJ) | 452(CARG), 457(CARH), 462(CARK), 464(CARL) | 171(CARA), 395(CARB) |

The glycan at each glycosylation site is defined by segment identifiers in parentheses generated by the CHARMM-GUI, such as CARA, CARB, CARC, etc.

MD Simulation Settings

All molecular mechanics calculations for parametrization were carried out using the CHARMM program version c41a2 and with the polarizable Drude force field.10, 11, 40, 41 The water model is the polarizable SWM4-NDP model. 42 The validation MD simulations were carried out using OpenMM 7.4.2 with both additive CHARMM36 force field 4, 31, 43 and polarizable CHARMM Drude force field. CHARMM modified TIP3P water model was used in the additive simulations.44 All polarizable MD simulations used a 1 fs time step while the additive simulations used 2 fs time step. All MD simulations were performed at 300 K, unless otherwise stated. All minimizations and MD equilibrations were performed following the previously presented protocol for lipids10, 41 and details of the integrators and treatment of nonbond interactions were those presented in our recent protein force field optimization study.19 Validation MD simulations to calculate NMR coupling constants were run for 0.5 μs each using both the additive and polarizable force fields.

J Coupling Equations

NMR heteronuclear three-bond proton-carbon coupling constants (in Hz) for the glycopeptide angle rotations 3JHαHβ, 3JHNHα, 3JHΝH2 were computed from the simulations using modified Karplus eqs 1–5. 45

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

To compare J coupling between published experimental data and ensemble averages from the MD simulations, the value of the dihedral angle of interest was first calculated for each snapshot of each glycopeptide in the simulation for which the corresponding J coupling value was calculated using the above equations. The resulting J coupling values for the dihedral angle of interest were then averaged for all snapshots from the 0.5 μs MD simulations (coordinates saved every 10 ps) yielding the presented ensemble average. The convergence of J coupling was evaluated by dividing the trajectories into ten 50 ns blocks.

Parametrization Using Reweighting Targeting Experimental Condensed Phase Data 46:

In parameter optimization through reweighting we minimize the target function, f,

| 6 |

where τ represents the probability of conformations reproducing the experimental observable A, RMSE is the root-mean-square error between the initial and new parameters, λ and Δλ, respectively, and w is an assigned weighting factor to balance the contributions of reproduction of the experimental observables and the change in the parameters during the reweighting procedure. β is the Boltzmann constant multiplied by the temperature. The ensemble average, indicated by brackets, < >, of the targeted experimental properties, A, associated with a new force field parameter set λ + Δλ is determined from

| 7 |

, in which Eλ and Eλ + Δλ are the potential energies with parameters λ and λ + Δλ for each sampled conformation. Sampling of parameter changes is performed using Metropolis Monte Carlo sampling and the RMSE between the initial and new parameter is calculated based on eq 8 where n is the number of parameters being optimized.

| 8 |

Results and Discussion

Parametrization Strategy

The initial electrostatic parameters, including the partial atomic charges, atomic polarizabilities (ALPHA values) and atomic Thole scaling factors (THOLE values), were transferred directly from the full monosaccharides, the available glycosidic linkages, and the proteins. Details of the optimization of the electrostatic parameters applied to the N- and O-linkage nitrogen and oxygen atoms, respectively, were presented in previous work.9, 11

N-Glycans.

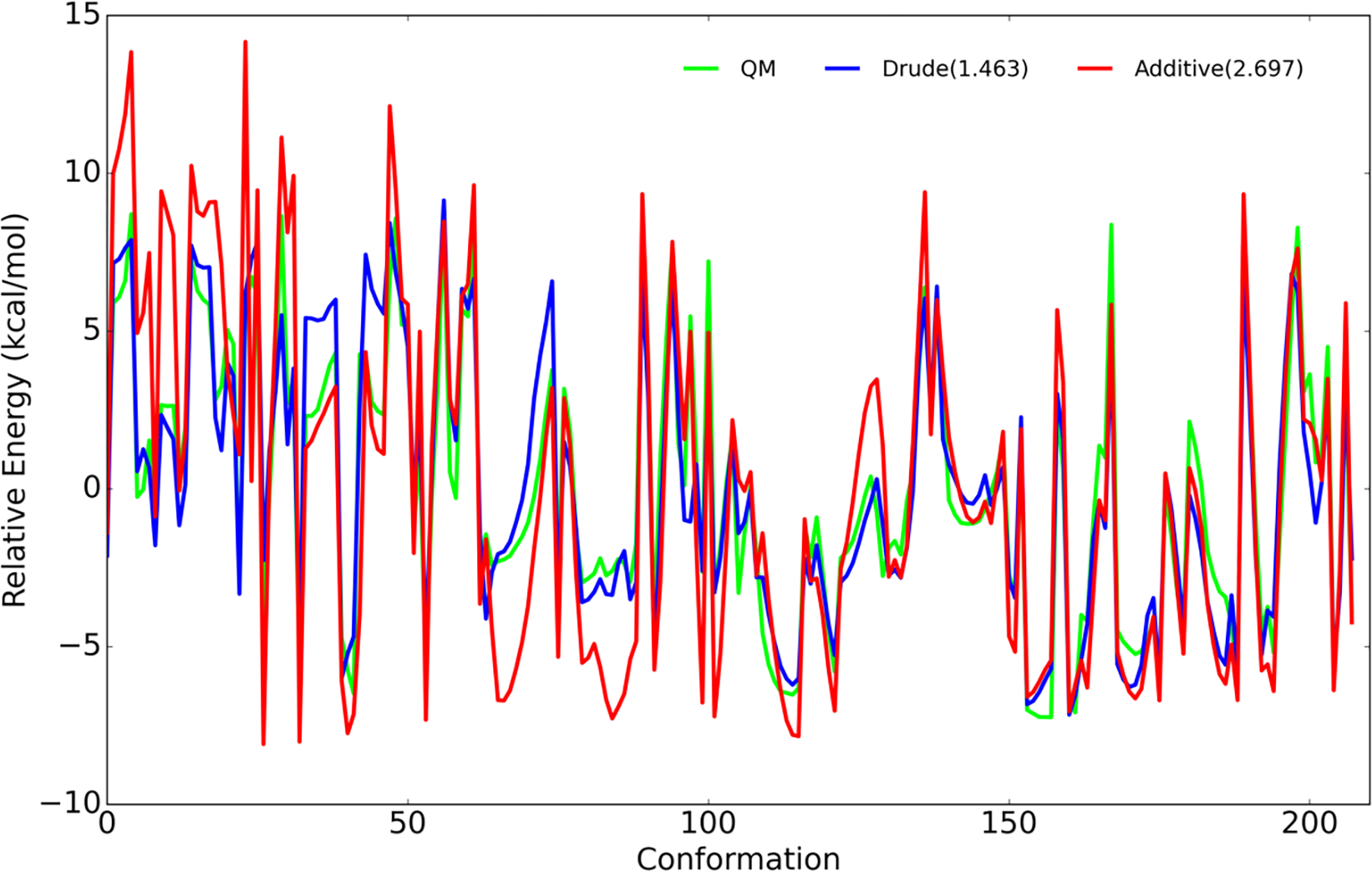

To develop the Drude force field parameters for the N- linkage, hexopyranose with an N-acetyl moiety substituted at C1 was used. Both α and β anomers of the linkage were treated explicitly. Most of the initial bond, angle, and dihedral parameters were readily transferred from the N-acetyl substituent at the C2 position, as previously developed for GlcNAc and GalNAc. The missing dihedral parameters (C–N–C1–C2/O5, N–C1–C2/O5-C3/C5) were optimized targeting a 1D QM scan at the MP2/6–31G*//RIMP2/cc-pVTZ model chemistry of the C–N–C1–C2 dihedral. The dihedral parameters were optimized using a least squares fitting protocol to minimize the root-mean-square (RMS) error between the QM and MM energy surfaces. Energy surfaces were offset to zero at the lowest energy conformation over all model compound anomers, and the conformations with relative QM energies of > 12 kcal/mol were excluded during the fitting. The refined dihedral parameters obtained from the least squares fitting protocol were able to reproduce the low-energy profiles for both α- and β-anomers of N-acetyl derivative (Figure 2). The final RMSE for the Drude force field was 1.46 kcal/mol versus 2.70 kcal/mol for the additive C36 force field indicating the ability to yield improved conformational properties due to the presence of explicit polarization in the Drude model. Potentially contributing to the difference in the level of agreement of the Drude and C36 FFs with the QM data is the use of different model compounds and energy scans as target data for the optimization, although both efforts used the QM (RI)MP2/cc-pVTZ//MP2/6–31G(d) model chemistry with the only difference being the use of canonical MP2 with C36 versus RIMP2 with the Drude for the treatment electron correlation in the single point calculations.

Figure 2.

Relative conformational energies of selected conformations of hexopyranose with N-acetyl substituted at C1 for both the α and β anomers. All the model compound conformations with relative QM energies below 12 kcal/mol are included. RMSE of Drude and additive C36 relative energies with respect to QM are included in parentheses shown in the inset.

O-Glycans.

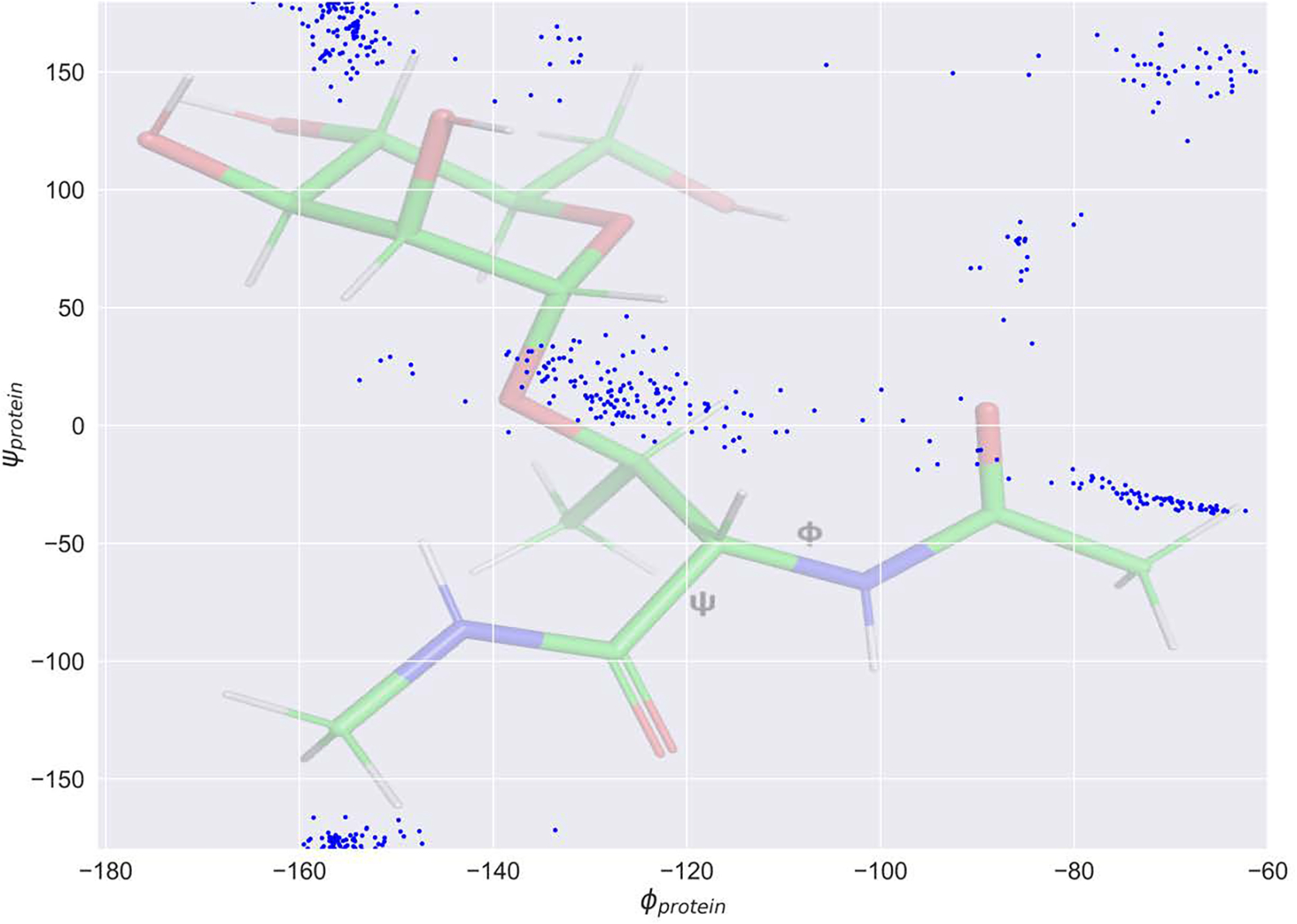

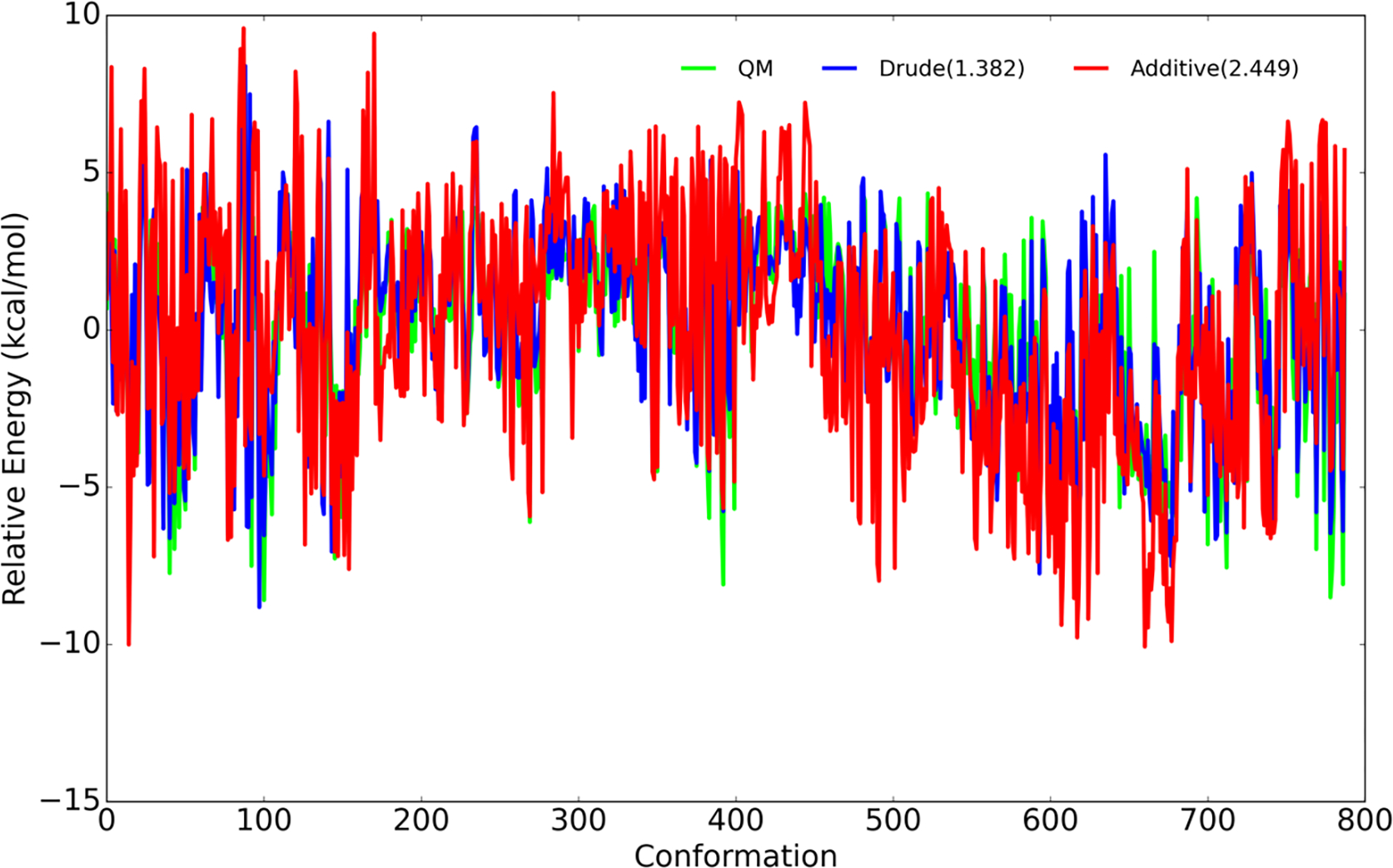

To develop Drude force field parameters for O-glycosidic linkages, the α and β anomers of Ser- and Thr-linked hexopyranose monosaccharide were used. Initial values for bonded and nonbonded parameters were transferred from the carbohydrates 8–11 and proteins 40. For each linkage type there are a total of 32 possible diastereomers associated with the eight possible diastereomers for the monosaccharide and two possible amino acids (namely, Ser and Thr) times the α and β anomers for the monosaccharide (8×2×2×1=32). Since the number of possible 2D scans is huge and computationally expensive, it was necessary to prepare target data on a practical number of energy surfaces. Accordingly, QM scans were performed on the THP-Thr/Ser model compounds shown in Figure 1 (top left panel). Besides the computational cost of omitting the hydroxyl groups, use of this simple compound can reduce the occurrence of gas phase hydrogen bonds between the carbohydrate and amino acids that can complicate the energy surfaces. In addition to the THP-Thr/Ser QM 2D φ/ψ scan, QM data were also generated by scanning the χ glycosidic dihedrals every 15°. Since the amino acid φ/ψ dihedrals are important for the conformation of the protein, for both 2D φ/ψ and χ, the protein φ/ψ dihedrals were kept close to the values from the distributions shown in Figure 3. The carbohydrate ring oxygen was constrained in three different orientation (at −60°, 0°, and 60° as shown in Figure S1) with respect to the amino acid HN for the χ scan and χ was constrained at −60°, 0°, and 60° for the glycopeptide linkage φ/ψ scan with THP-Thr/Ser. The QM calculation involved geometry optimization in the presence of the constraints for the model compounds at the ab initio MP2/6–31G(d) model chemistry. The final QM conformations of the THP-Thr/Ser model compounds with relative energies lower than 8.0 kcal/mol were then used to construct the full glycopeptide linkage model compound with hydroxyls shown in Figure 1 (bottom left panel). All generated conformers were then subjected to QM optimization and single point energy calculations to generate the final target data for the fitting shown in Figure 4. Since the O linkage based on Ser shares the same atom types with p1→6p glycosidic linkages that were previously parametrized, the parameters were transferred from existing glycosidic linkage 9 and only missing parameters were optimized. Table S2 includes a list of the optimized parameters along with the final values obtained in this study. As with the N-glycan conformational energies, there is significant improvement with the RMSE for the Drude FF being 1.38 kcal/mol versus 2.45 kcal/mol for the additive C36 FF (Figure 4). This again points to the presence of explicit polarization in the Drude FF leading to improved treatment over the additive FF.

Figure 3.

2D protein φ/ψ distribution of target data used during the O-linked dihedral fitting. The distribution is overlaid on the structure of the full O-linked Thr model compound (Figure 1, bottom left panel).

Figure 4.

Relative conformational energies of selected conformations of the hexopyranose monosaccharide linked to the Ser and Thr dipeptides for both the α and β anomers. All the model compound conformations with relative QM energies below 12 kcal/mol are included. RMSE of Drude and additive C36 relative energies with respect to QM are included in parentheses shown in the inset.

Reweighting-Based Parameter Optimization Targeting Solution NMR Data

After the initial optimization of the dihedral parameters targeting the QM data, MD simulations of the target glycopeptides were performed. NMR J-coupling data calculated from these simulations did not reproduce J values very well (shown as DrudeQM in Figure 5). We therefore performed a reweighting optimization on the new parameters targeting the experimental J-coupling data associated with the protein backbone. The reweighting procedure was adopted from a previously used reweighting protocol as described in eqs 6–8.46 Using the target dihedral and corresponding J values from the initial trajectories small perturbation to the dihedral force constant was undertaken and then converted to the observable J values using equations 1–5. A Monte Carlo simulated annealing (MCSA) protocol was combined in the context of reweighting eqs 6–8 to drive the optimization against the target experimental value. The reweighting follows the standard Metropolis acceptance criteria for updating dihedral force constants. An additional constraint was included as a penalty to avoid overfitting. This was based on the RMSE between the perturbed and original values of the dihedral force constants, eq 8, thereby limiting the change in the parameters from the initial values from the QM fitting. The final parameter sets therefore represent an agreement of improved reproduction of the experimental J values and minimum perturbation from initial QM-based dihedral parameter values (Table S2).

Figure 5.

3JHαHβ vs φ (protein) distribution obtained from MD. 3JHαHβ calculated based on eq 1 for every 1° form −180° to 180°. “QM” indicates the initial QM-based dihedral parameters.

Validation Runs

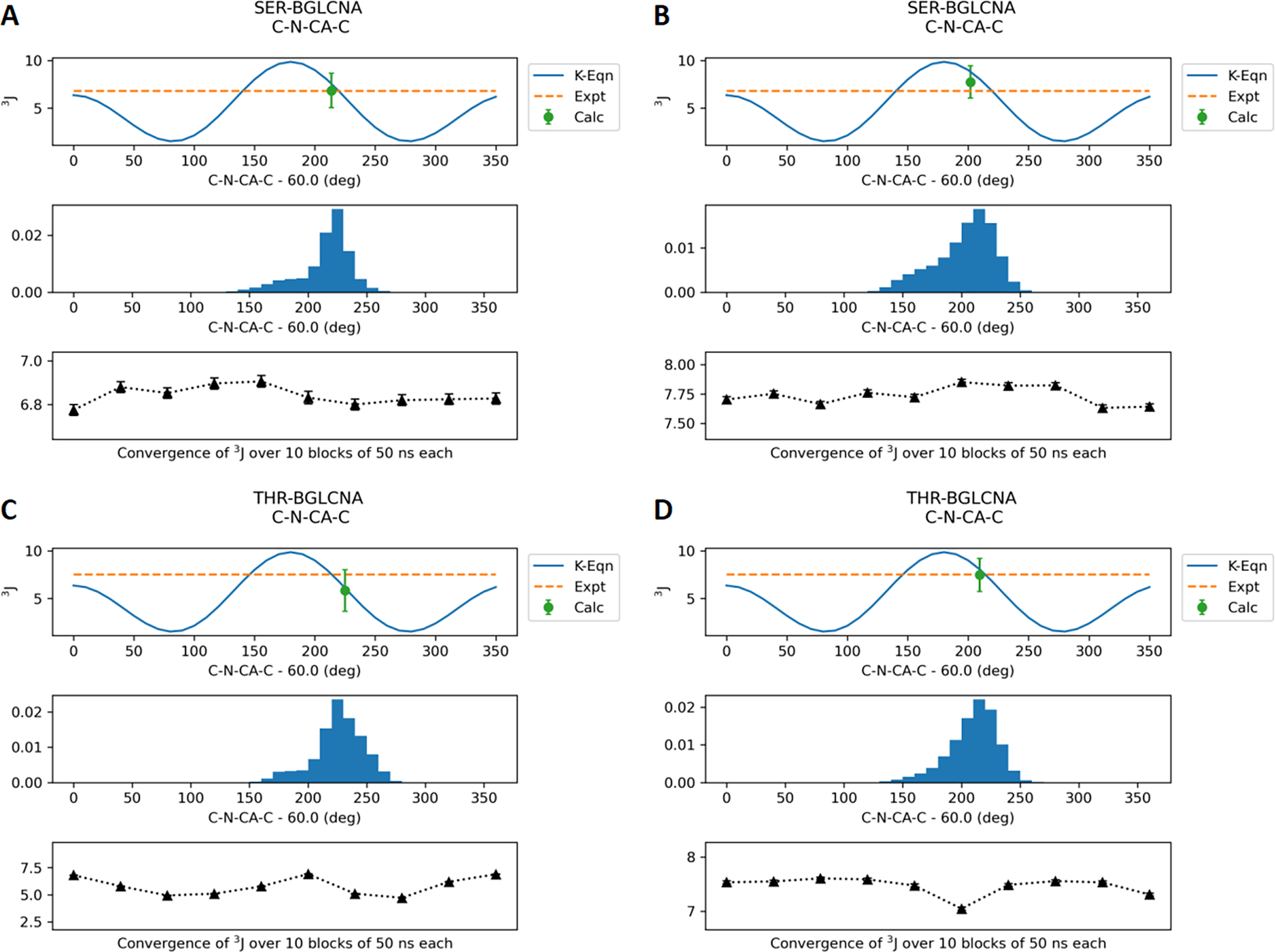

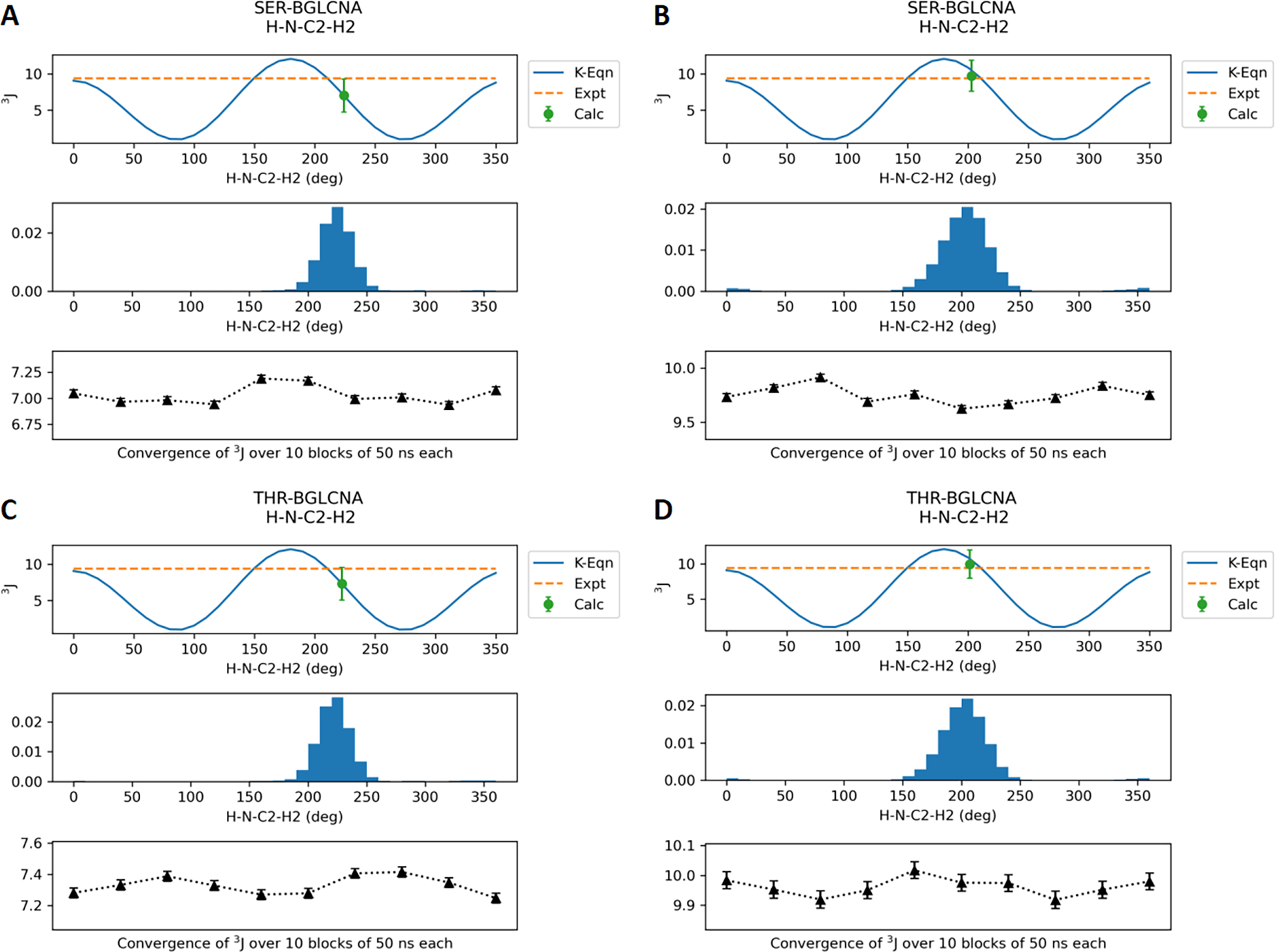

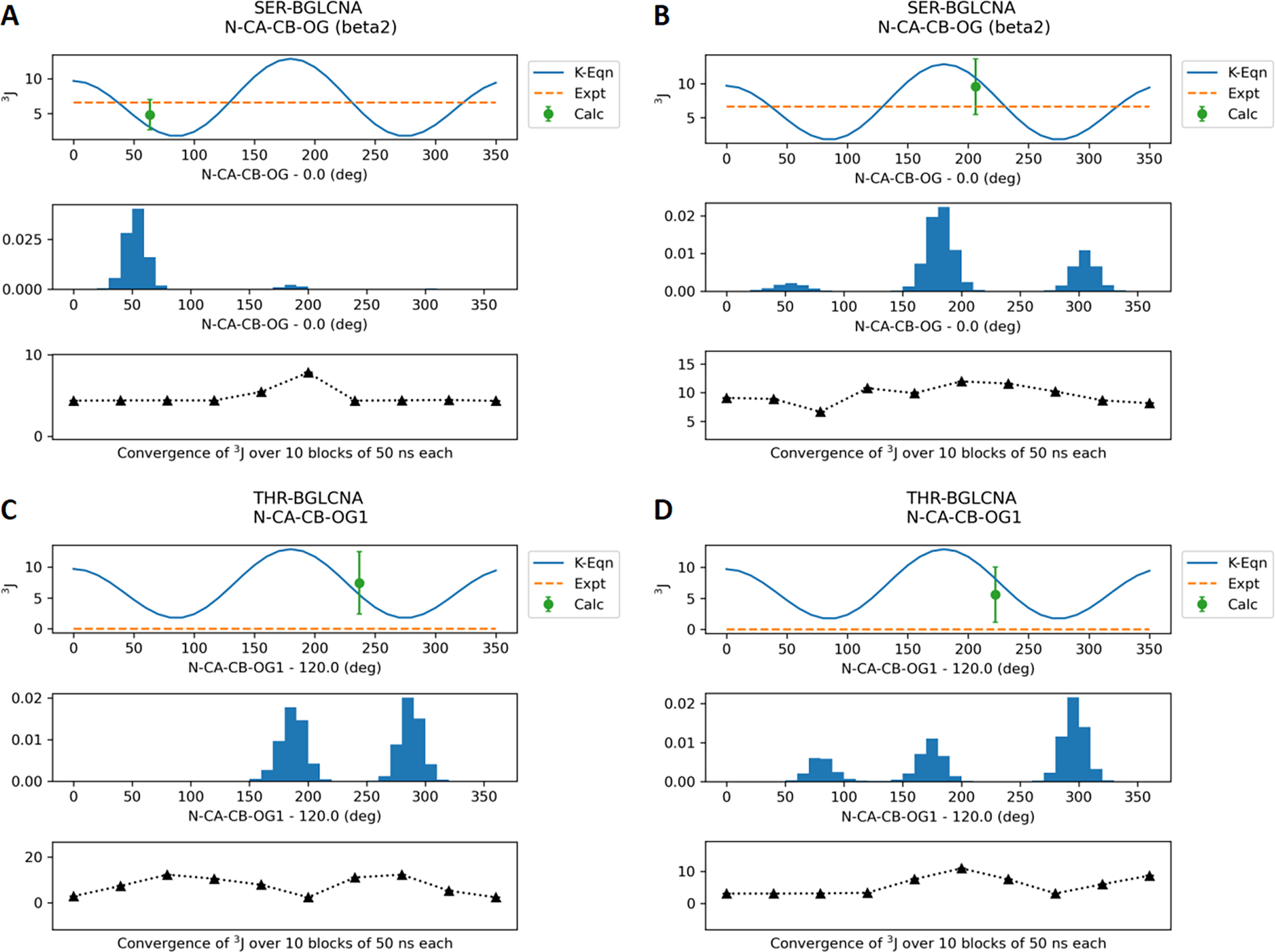

Final parameters for the O-linkages were validated by calculating J-coupling values based on trajectories generated using reweighted dihedral parameters. The eight model compounds with O-linkages to Ser/Thr were simulated with the optimized Drude force field as well as CHARMM36 for 0.5 μs each. The average J coupling values calculated using eqs 1–5 over the trajectories are shown in Table 2. The Drude J coupling values for backbone φ are in agreement with the experimental values with the RMSE increased slightly compared to C36. Figure 6 shows the distribution of the φ dihedral (C-N-CA-C) in SER/THR-BGLCNA along with the average values calculated every 50 ns. Similar distributions for other model compounds are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S2–S4). In the case of glycopeptides with N-acetyl side chains, the J coupling values for the θ dihedral (HN-N-C2-H2) are consistently lower than experimental values with RMSE increased significantly. However, the majority of the conformations sampled are between 120° and 240° (Figures 7, S5, and S6) that correspond to the anti conformation observed in the experimental data. Note that the φ and θ dihedral parameters were optimized in a prior studies11 and are only analyzed for validation. Most importantly, the J coupling values for the χ dihedrals (N-CA-CB-OG/OG1) optimized in this study show good agreement with the experimental data. Lower RMSE was obtained with the Drude FF relative to C36 in the case of J coupling calculated with eq 4 for the SER models. Figure 8 shows the dihedral distribution for SER/THR-BGLCNA, while distributions for other six model compounds are shown in Figure S7–S9.

Table 2.

J Coupling Constants for Different Dihedrals from the Model Compounds from Experiment, the Drude Force Field and the C36 Additive Force Field.a

| ϕ (CY-N-CA-C) | θ (HN-N-C2-H2) | χ (N-CA-CB-OG) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | name | expt | C36 | Drude | expt | C36 | Drude | expt | C36 | Drude | ||||

| Eq4 | Eq5 | Eq3 | Eq4 | Eq5 | Eq3 | |||||||||

| 1 | SER-AGALNA | 6.2 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 7.2 | 5.5, 4.5 | 9.4 | 5.6 | - | 10.4 | 3.0 | - |

| 2 | THR-AGALNA | 8.8 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 7.5 | 2.5 | - | - | 3.4 | - | - | 2.7 |

| 3 | SER-BGALNA | 6.6 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 6.8, NA | 9.6 | 5.7 | - | 5.6 | 2.8 | - |

| 4 | THR-BGALNA | 7.4 | 7.6 | 5.4 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 7.5 | 3.5 | - | - | 3.3 | - | - | 9.8 |

| 5 | SER-BGLC | 6.9 | 7.7 | 6.9 | - | - | - | 4.6, NA | 9.3 | 5.3 | - | 4.4 | 2.8 | - |

| 6 | THR-BGLC | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.8 | - | - | - | 3.4 | - | - | 3.7 | - | - | 8.2 |

| 7 | SER-BGLCNA | 6.8 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 7.0 | 6.6, 5.2 | 9.6 | 5.9 | - | 4.8 | 2.9 | - |

| 8 | THR-BGLCNA | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 7.3 | - | - | - | 5.6 | - | - | 7.4 |

| RMS diff b | - | 0.88 | 1.42 | - | 0.43 | 2.21 | - | 3.67 | - | - | 2.69 | - | - | |

NA – Not available

Root mean square difference was calculated for values only if experimental data are available for all relevant systems.

Figure 6.

J-coupling values for the protein (φ) dihedral C-N-CA-C for the model compounds SER-BGLCNA and THR-BGLCNA. (A) and (C) represent the Drude FF results. (B) and (D) represent the additive C36 FF results. The results for the other six compounds are provided in the Supporting Information.

Figure 7.

J-coupling values for the dihedral HN-N-C2-H2 for the model compounds SER-BGLCNA and THR-BGLCNA. (A) and (C) represent the Drude FF results. (B) and (D) represent the additive C36 FF results. The results for the other four compounds are provided in the Supporting Information.

Figure 8.

J-coupling values for the dihedral N-CA-CB-OG for the model compounds SER-BGLCNA and THR-BGLCNA. (A) and (C) represent the Drude FF results. (B) and (D) represent the additive C36 FF results. With THR-BGLCNA experimental data is not available. The results for the other four compounds are provided in the Supporting Information.

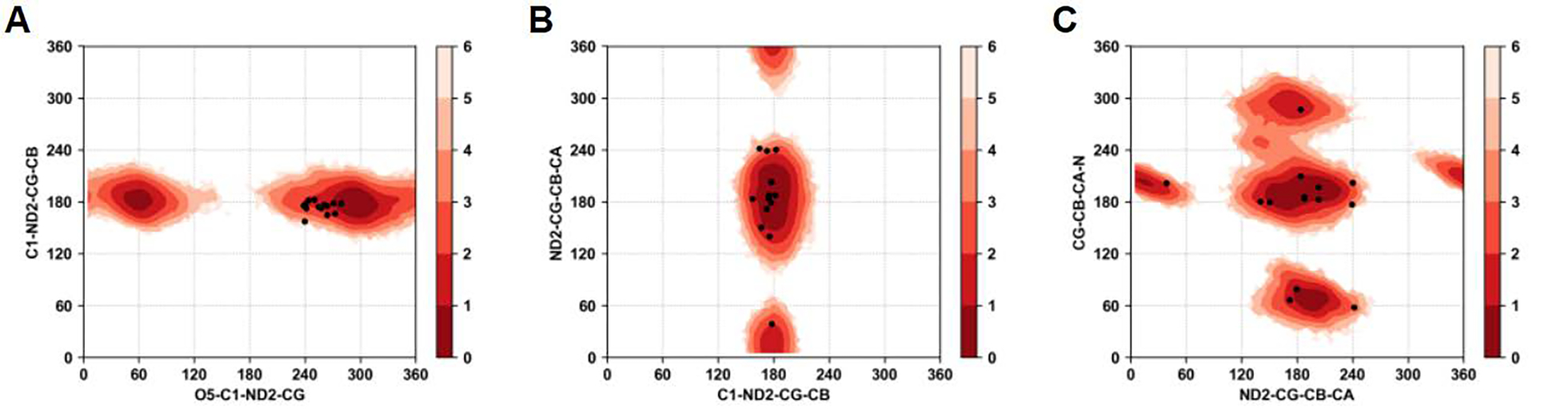

Four glycoproteins were studied with multiple O- and N-linked glycosylations by starting from the crystal structures reported in Table 1. Analysis of the trajectories was performed on the conformational variability of the different carbohydrates and proteins. Trajectories were aligned to starting structure with respect to protein backbone atoms before RMSD calculations. RMSD of all carbohydrates grouped together compared to RMSD of all protein showed that the glycan portions are sampling large regions of conformational space around the glycosylation site. Figure S10 shows the RMSD of protein, carbohydrate, and protein+carbohydrate for all four systems over the 0.5 μs simulations. RMSD of the proteins remain lower than 3 Å for all systems except for PDB code 1K7C where it increased to 4 Å gradually from 2 Å during 100–300 ns and then stabilized. The RMSD of the carbohydrates varied from 6 to 16 Å across the systems. Such high flexibility of the glycans is consistent with high conformational diversity of carbohydrates as observed in NMR and crystallographic studies. Contributing to the magnitude of the RMSD is the presence of multiple glycans on each protein, where the RMSD is overall the glycans listed in Table 1. Analysis was also performed on the dihedral angle distributions of the glycosidic linkages by pooling the MD simulations for all systems. Figure 9 shows that for the N-glycans the glycosidic dihedral angle distributions are in good agreement with the values from the crystal structures. The glycosidic linkage dihedral O5-C1-ND2-CG shows two minima around 60° and 300°, while closer to the protein the dihedral C1-ND2-CG-CB shows a narrow distribution around 180°. The only region sampled in the MD simulations but not observed in the crystal structure occurs with the O5-C1-ND2-CG dihedral in the region around 60°.

Figure 9.

Boltzmann inverted glycosidic dihedral angle distributions associated with all the N-glycans from all four glycoproteins. A) C1-ND2-CG-CB vs. O5-C1-ND2-CG, B) ND2-CG-CB-CA vs. C1-ND2-CG-CB, and C) CG-CB-CA-N vs. ND2-CG-CB-CA. Black dots indicate the values of the dihedrals observed in crystallographic structures.

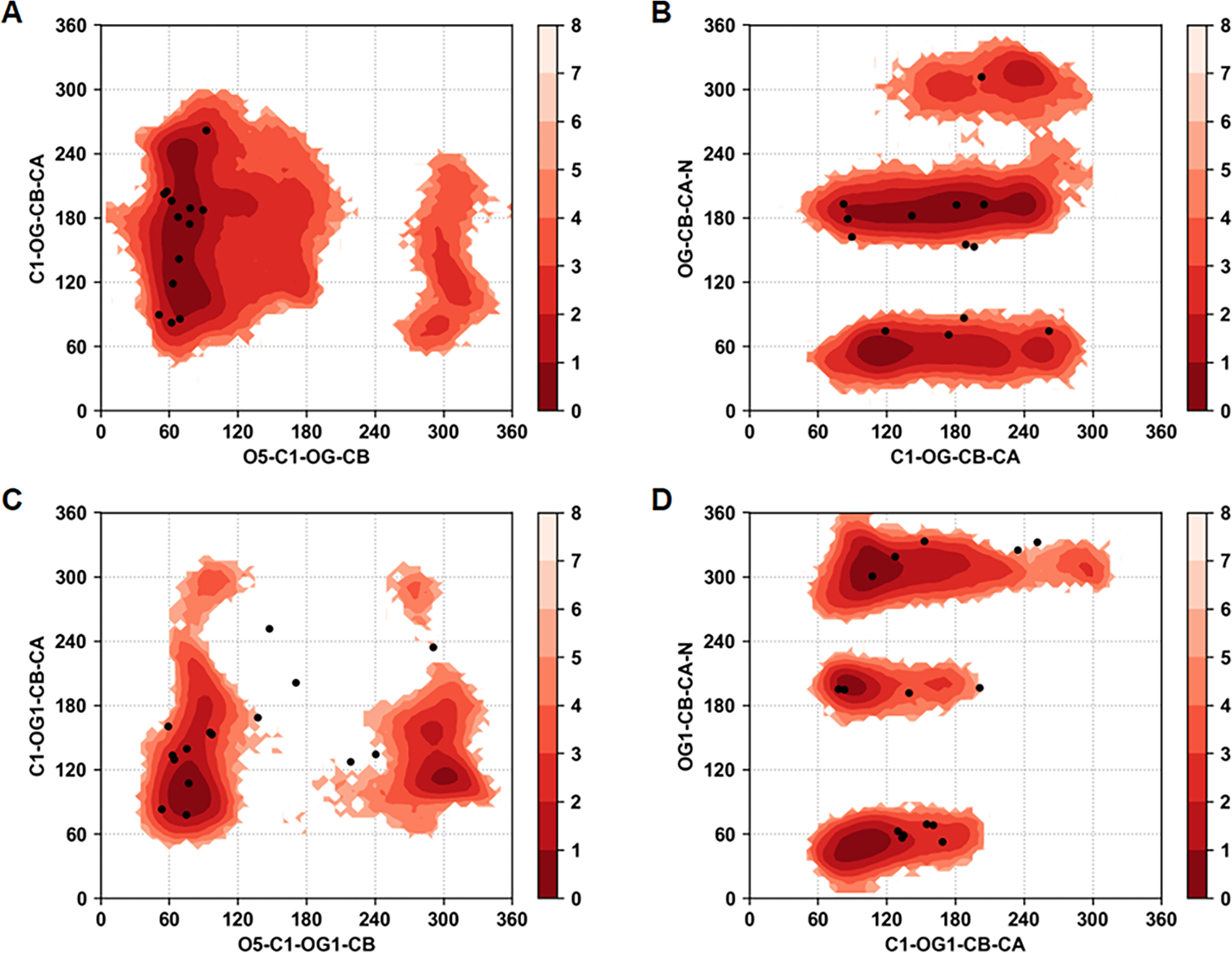

Similarly for the O-glycans dihedral sampling near the glycosidic linkage is in very good agreement with the experimentally observed values in the crystal structures. Figure 10 shows the Boltzmann inverted dihedral distributions for the pooled data of the dihedrals for the O-linked glycans from PDB codes 1RMG and 3GLY. Both the SER and THR linked O-glycans show three clear minima for the dihedral OG-CB-CA-N sampling the g(+), g(−), and anti conformational states. Importantly, the glycosidic linkage dihedral O5-C1-OG-CB for both SER and THR linked glycans shows a minima around 60° for α anomers and another minima at 300° for β anomers. A broader sampling of the dihedral C1-OG-CB-CA was observed in SER linked glycans compared the same in THR linked glycans. Overall, these results indicate that the developed parameters are sampling conformations of the glycosidic linkages consistent with those observed in glycoprotein crystal structures.

Figure 10.

Boltzmann inverted glycosidic dihedral angle distributions associated with all the O-glycans from all four glycoproteins. (A) C1-OG-CB-CA vs. O5-C1-OG-CB in Ser O-linkages, (B) OG-CB-CA-N vs. C1-OG-CB-CA in Ser O-linkages, (C) C1-OG1-CB-CA vs. O5-C1-OG1-CB in Thr O-linkages, and (D) OG1-CB-CA-N vs. C1-OG1-CB-CA in Thr O-linkages. Black dots indicate the values of dihedrals observed in crystallographic structures.

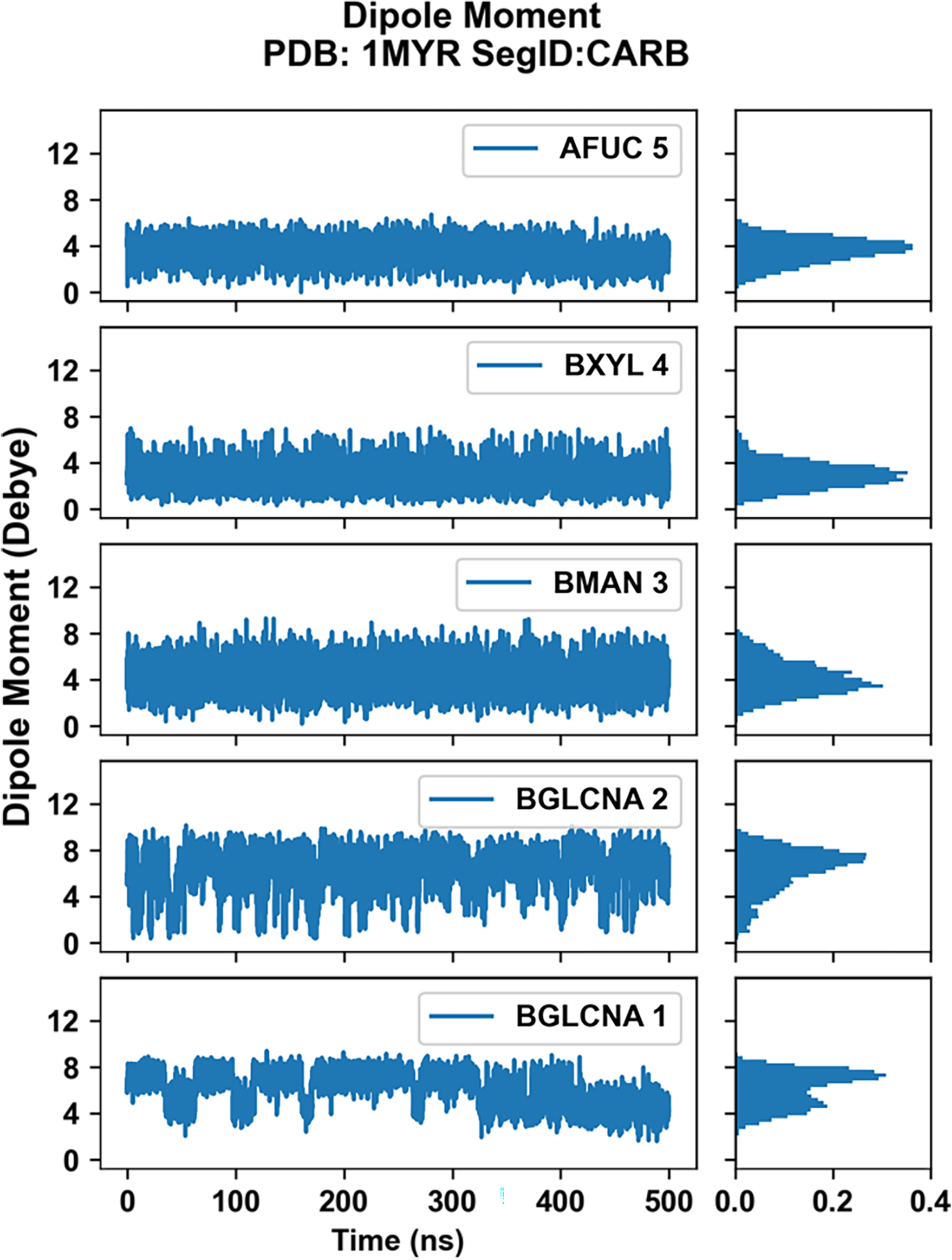

The presence of explicit polarization in the Drude FF allows for variations in the dipole moments beyond those due to changes in intramolecular geometry. Accordingly, dipole moment analysis was performed on each monosaccharide by selecting the groups of atoms with integer charge. Figure S11 shows the atom selection scheme. More details about selection of atoms appropriate calculation of dipole can be obtained in the CHARMM-GUI Drude Prepper article.34 We observed that most of the cases with N-glycans containing the N-acetyl glucosamines (BGLCNA) at positions 1 and 2 showed slightly different dipole moments going from 1 to 2. In some cases, as shown in Figure 11 for N-glycosylation at Asn265 for PDB code 1MYR, the BGLCNA residues show a bimodal distribution of the dipole moment. Analysis of the time series shows the dipole moment of the BGLCNA monosaccharides to undergo multiple transitions between the lower and higher dipole moments. Similar behavior is observed for the majority of monosaccharides for which a bimodal distribution exist, though exceptions are present (Figure S11). Such dipole variability indicates that the Drude FF will be of utility to investigate the role of changes in the electronic structure of glycopeptides and glycoproteins in biologically relevant scenarios.

Figure 11.

Monosaccharide dipole moment analysis for the N-glycan of PDB code 1MYR at Asn265 (segment ID: CARB assigned by CHARMM-GUI, see Table 1). Changes in dipole moment across the simulation are shown on left. On right, the normalized probabilities of dipole moment are shown for each monosaccharide.

Conclusions

The present study performs force-field parameter optimization of glycopeptide moieties extending the Drude polarizable force field to glycopeptides and glycoproteins. Reweighting of parameters allowed for fine-tuning of the force field to reproduce the target solution properties such as J coupling with more accuracy than direct transfer of parameters based on gas phase QM data. This extension will allow for studies of the role of post-translations modifications involving the O- and N-linked glycosylation on various biological phenomena including protein-protein interactions and protein stability using molecular simulations. Currently the PDB database has more than ~9400 protein structures that exhibit O- and N-glycosylation at multiple sites indicating the range of systems to which the Drude force field may now be applied. In addition, this extension will allow use of a polarizable force field in the study of intrinsically disordered peptides that use glycosylation to protect against proteolysis.47

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the NIH (GM131710) and computational support from the University of Maryland Computer-Aided Drug Design Center and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation Grant Number OCI-1053575 are acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing interest(s): ADM Jr. is cofounder and CSO of SilcsBio LLC.

Supporting Information

Available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c04245.

Included are tables of the validation compounds and optimized parameters and figures of the model compound conformations used to QM data generation, J-coupling data and associated dihedral distributions, RMSD plots from the glycoprotein simulations, the definitions of the particles used for dipole moment calculations and times series and probability distributions of the monosaccharides from the glycoprotein MD simulations.

References

- (1).Whitford PC; Blanchard SC; Cate JH; Sanbonmatsu KY Connecting the kinetics and energy landscape of tRNA translocation on the ribosome. PLoS Comput Biol 2013, 9 (3), e1003003. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dror RO; Pan AC; Arlow DH; Borhani DW; Maragakis P; Shan Y; Xu H; Shaw DE Pathway and mechanism of drug binding to G-protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 (32), 13118–13123. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1104614108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shaw DE; Maragakis P; Lindorff-Larsen K; Piana S; Dror RO; Eastwood MP; Bank JA; Jumper JM; Salmon JK; Shan Y; et al. Atomic-level characterization of the structural dynamics of proteins. Science 2010, 330 (6002), 341–346. DOI: 10.1126/science.1187409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McCammon JA; Gelin BR; Karplus M Dynamics of folded proteins. Nature 1977, 267 (5612), 585–590. DOI: 10.1038/267585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fadda E Molecular Simulations of complex carbohydrates and glycoconjugates. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biology 2022, 69, 102175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cornell WD; Cieplak P; Bayly CI; Gould IR; Merz KM; Ferguson DM; Spellmeyer DC; Fox T; Caldwell JW; Kollman PA A Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1995, 117 (19), 5179–5197. DOI: 10.1021/ja00124a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; MacKerell AD; Bashford D; Bellott M; Dunbrack RL; Evanseck JD; Field MJ; Fischer S; Gao J; Guo H; Ha S; et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B 1998, 102 (18), 3586–3616. DOI: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; MacKerell AD; Brooks B; Brooks CL; Nilsson L; Roux B; Won Y; Karplus M CHARMM: The Energy Function and Its Parameterization. In Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2002. [Google Scholar]; MacKerell AD Jr.; Banavali N; Foloppe N Development and current status of the CHARMM force field for nucleic acids. Biopolymers 2000, 56 (4), 257–265. DOI: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pastor RW; Mackerell AD Jr. Development of the CHARMM Force Field for Lipids. J Phys Chem Lett 2011, 2 (13), 1526–1532. DOI: 10.1021/jz200167q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kaminski GA; Friesner RA; Tirado-Rives J; Jorgensen WL Evaluation and Reparametrization of the OPLS-AA Force Field for Proteins via Comparison with Accurate Quantum Chemical Calculations on Peptides. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2001, 105 (28), 6474–6487. DOI: 10.1021/jp003919d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Damm W; Frontera A; Tirado–Rives J; Jorgensen WL OPLS all-atom force field for carbohydrates. Journal of Computational Chemistry 1997, 18 (16), 1955–1970. DOI: (acccessed 2020/01/13). [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Soares TA; Hunenberger PH; Kastenholz MA; Krautler V; Lenz T; Lins RD; Oostenbrink C; van Gunsteren WF An improved nucleic acid parameter set for the GROMOS force field. J Comput Chem 2005, 26 (7), 725–737. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pol-Fachin L; Rusu VH; Verli H; Lins RD GROMOS 53A6GLYC, an Improved GROMOS Force Field for Hexopyranose-Based Carbohydrates. J Chem Theory Comput 2012, 8 (11), 4681–4690. DOI: 10.1021/ct300479h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Guvench O; Hatcher ER; Venable RM; Pastor RW; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Glycosidic Linkages between Hexopyranoses. J Chem Theory Comput 2009, 5 (9), 2353–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shi Y; Xia Z; Zhang J; Best R; Wu C; Ponder JW; Ren P The Polarizable Atomic Multipole-based AMOEBA Force Field for Proteins. J Chem Theory Comput 2013, 9 (9), 4046–4063. DOI: 10.1021/ct4003702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Patel S; Brooks CL III CHARMM Fluctuating Charge Force Fields for Proteins: I Paramaterization and application to bulk organic liquid simulations. J Comp Chem 2004, 25 (1), 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang ZX; Zhang W; Wu C; Lei H; Cieplak P; Duan Y Strike a balance: optimization of backbone torsion parameters of AMBER polarizable force field for simulations of proteins and peptides. J Comput Chem 2006, 27 (6), 781–790. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.20386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Halgren TA; Damm W Polarizable force fields. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2001, 11 (2), 236–242. DOI: 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemkul JA; Huang J; Roux B; MacKerell AD Jr. An Empirical Polarizable Force Field Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator Model: Development History and Recent Applications. Chem Rev 2016, 116 (9), 4983–5013. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cieplak P; Dupradeau FY; Duan Y; Wang J Polarization effects in molecular mechanical force fields. J Phys Condens Matter 2009, 21 (33), 333102. DOI: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/33/333102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ponder JW; Case DA Force fields for protein simulations. Advances in Protein Chemistry 2003, 66, 27–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baker CM Polarizable force fields for molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2015, 5 (2), 241–254. DOI: 10.1002/wcms.1215 (acccessed 2020/01/15). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lopes PEM; Roux B; MacKerell AD Molecular modeling and dynamics studies with explicit inclusion of electronic polarizability: theory and applications. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2009, 124 (1), 11–28. DOI: 10.1007/s00214-009-0617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Warshel A; Kato M; Pisliakov AV Polarizable Force Fields: History, Test Cases, and Prospects. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2007, 3 (6), 2034–2045. DOI: 10.1021/ct700127w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Freddolino PL; Harrison CB; Liu Y; Schulten K Challenges in protein folding simulations: Timescale, representation, and analysis. Nature physics 2010, 6 (10), 751–758. DOI: 10.1038/nphys1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhu X; Lopes PEM; MacKerell AD Jr Recent developments and applications of the CHARMM force fields. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2012, 2 (1), 167–185. DOI: 10.1002/wcms.74 (acccessed 2019/11/06). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemkul JA; Savelyev A; MacKerell AD Jr. Induced Polarization Influences the Fundamental Forces in DNA Base Flipping. J Phys Chem Lett 2014, 5 (12), 2077–2083. DOI: 10.1021/jz5009517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang J; MacKerell AD Jr. Induction of peptide bond dipoles drives cooperative helix formation in the (AAQAA)3 peptide. Biophys J 2014, 107 (4), 991–997. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lin FY; MacKerell AD Jr. Improved Modeling of Cation-pi and Anion-Ring Interactions Using the Drude Polarizable Empirical Force Field for Proteins. J Comput Chem 2019, 41, 439–448. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.26067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemkul JA Same fold, different properties: polarizable molecular dynamics simulations of telomeric and TERRA G-quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 48, 561–575. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkz1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang J; Cieplak P; Li J; Wang J; Cai Q; Hsieh M; Lei H; Luo R; Duan Y Development of polarizable models for molecular mechanical calculations II: induced dipole models significantly improve accuracy of intermolecular interaction energies. J Phys Chem B 2011, 115 (12), 3100–3111. DOI: 10.1021/jp1121382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yang M; Aytenfisu AH; MacKerell AD Jr Proper balance of solvent-solute and solute-solute interactions in the treatment of the diffusion of glucose using the Drude polarizable force field. Carbohydrate Research 2018, 457, 41–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.carres.2018.01.004 (acccessed 2018/02/06/11:42:42). From ScienceDirect. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Aytenfisu AH; Yang M; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM Drude Polarizable Force Field for Glycosidic Linkages Involving Pyranoses and Furanoses. J Chem Theory Comput 2018, 14 (6), 3132–3143. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jana M; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM Drude Polarizable Force Field for Aldopentofuranoses and Methyl-aldopentofuranosides. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119 (25), 7846–7859. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b01767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pandey P; Aytenfisu AH; MacKerell AD Jr.; Mallajosyula SS Drude Polarizable Force Field Parametrization of Carboxylate and N-Acetyl Amine Carbohydrate Derivatives. J Chem Theory Comput 2019, 15 (9), 4982–5000. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lin FY; Lopes PEM; Harder E; Roux B; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable Force Field for Molecular Ions Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator. J Chem Inf Model 2018, 58 (5), 993–1004. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kognole AA; Aytenfisu AH; MacKerell AD Jr. Balanced polarizable Drude force field parameters for molecular anions: phosphates, sulfates, sulfamates, and oxides. J Mol Model 2020, 26 (6), 152. DOI: 10.1007/s00894-020-04399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lin FY; MacKerell AD Jr. Force Fields for Small Molecules. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 2022, 21–54. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9608-7_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Baker CM; Anisimov VM; MacKerell AD Jr. Development of CHARMM polarizable force field for nucleic acid bases based on the classical Drude oscillator model. J Phys Chem B 2011, 115 (3), 580–596. DOI: 10.1021/jp1092338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Savelyev A; MacKerell AD Jr. All-atom polarizable force field for DNA based on the classical drude oscillator model. J Comput Chem 2014, 10, 1652–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemkul JA; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable Force Field for DNA Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator: I. Refinement Using Quantum Mechanical Base Stacking and Conformational Energetics. J Chem Theory Comput 2017, 13 (5), 2053–2071. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemkul JA; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable force field for RNA based on the classical drude oscillator. J Comput Chem 2018, 39 (32), 2624–2646. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lemkul JA; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable Force Field for DNA Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator: II. Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Duplex DNA. J Chem Theory Comput 2017, 13 (5), 2072–2085. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yu H; Whitfield TW; Harder E; Lamoureux G; Vorobyov I; Anisimov VM; MacKerell AD Jr.; Roux B Simulating Monovalent and Divalent Ions in Aqueous Solution Using a Drude Polarizable Force Field. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2010, 6 (3), 774–786. DOI: 10.1021/ct900576a (acccessed 2016/07/29/19:10:15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Luo Y; Jiang W; Yu H; MacKerell AD Jr.; Roux B Simulation study of ion pairing in concentrated aqueous salt solutions with a polarizable force field. Faraday Discuss 2013, 160, 135–149; discussion 207–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li H; Chowdhary J; Huang L; He X; MacKerell AD Jr.; Roux B Drude Polarizable Force Field for Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Saturated and Unsaturated Zwitterionic Lipids. J Chem Theory Comput 2017, 13 (9), 4535–4552. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lin FY; Huang J; Pandey P; Rupakheti C; Li J; Roux BT; MacKerell AD Jr. Further Optimization and Validation of the Classical Drude Polarizable Protein Force Field. J Chem Theory Comput 2020, 16 (5), 3221–3239. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lin FY; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable Empirical Force Field for Halogen-Containing Compounds Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator. J Chem Theory Comput 2018, 14 (2), 1083–1098. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b01086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Small MC; Aytenfisu AH; Lin F-Y; He X; MacKerell AD Drude polarizable force field for aliphatic ketones and aldehydes, and their associated acyclic carbohydrates. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design 2017, 1–15, journal article. DOI: 10.1007/s10822-017-0010-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kumar A; Yoluk O; MacKerell AD Jr FFParam: Standalone package for CHARMM additive and Drude polarizable force field parametrization of small molecules. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2020, 41 (9), 958–970, 10.1002/jcc.26138. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.26138 (acccessed 2022/03/23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sacchettini JC; Baum LG; Brewer CF Multivalent Protein−Carbohydrate Interactions. A New Paradigm for Supermolecular Assembly and Signal Transduction. Biochemistry 2001, 40 (10), 3009–3015. DOI: 10.1021/bi002544j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Subedi Ganesh P.; Barb Adam W. The Structural Role of Antibody N-Glycosylation in Receptor Interactions. Structure 2015, 23 (9), 1573–1583. DOI: 10.1016/j.str.2015.06.015 (acccessed 2022/02/07). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Payne CM; Resch MG; Chen L; Crowley MF; Himmel ME; Taylor LE 2nd; Sandgren M; Stahlberg J; Stals I; Tan Z; et al. Glycosylated linkers in multimodular lignocellulose-degrading enzymes dynamically bind to cellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110 (36), 14646–14651. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1309106110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dwek RA Glycobiology: Toward Understanding the Function of Sugars. Chem Rev 1996, 96 (2), 683–720. DOI: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bause E Structural requirements of N-glycosylation of proteins. Studies with proline peptides as conformational probes. Biochem J 1983, 209 (2), 331–336. DOI: 10.1042/bj2090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hart GW; Brew K; Grant GA; Bradshaw RA; Lennarz WJ Primary structural requirements for the enzymatic formation of the N-glycosidic bond in glycoproteins. Studies with natural and synthetic peptides. J Biol Chem 1979, 254 (19), 9747–9753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Strous GJ; Dekker J Mucin-type glycoproteins. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1992, 27 (1–2), 57–92. DOI: 10.3109/10409239209082559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zachara NE; Hart GW The emerging significance of O-GlcNAc in cellular regulation. Chem Rev 2002, 102 (2), 431–438. DOI: 10.1021/cr000406u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Parrish RM; Burns LA; Smith DGA; Simmonett AC; DePrince AE 3rd; Hohenstein EG; Bozkaya U; Sokolov AY; Di Remigio R; Richard RM; et al. Psi4 1.1: An Open-Source Electronic Structure Program Emphasizing Automation, Advanced Libraries, and Interoperability. J Chem Theory Comput 2017, 13 (7), 3185–3197. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gaussian 03; Gaussian, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA, 2003. (accessed. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vanommeslaeghe K; Yang M; MacKerell AD Jr. Robustness in the fitting of molecular mechanics parameters. J Comp Chem 2015, 36 (14), 1083–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Huang J; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J Comput Chem 2013, 34 (25), 2135–2145. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Guvench O; Mallajosyula SS; Raman EP; Hatcher E; Vanommeslaeghe K; Foster TJ; Jamison FW; MacKerell AD CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Carbohydrate Derivatives and Its Utility in Polysaccharide and Carbohydrate–Protein Modeling. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2011, 7 (10), 3162–3180. DOI: 10.1021/ct200328p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jo S; Kim T; Iyer VG; Im W CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2008, 29 (11), 1859–1865. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kognole AA; Lee J; Park S-J; Jo S; Chatterjee P; Lemkul JA; Huang J; MacKerell AD Jr.; Im W CHARMM-GUI Drude prepper for molecular dynamics simulation using the classical Drude polarizable force field. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2022, 43 (5), 359–375. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.26795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Eastman P; Swails J; Chodera JD; McGibbon RT; Zhao Y; Beauchamp KA; Wang L-P; Simmonett AC; Harrigan MP; Stern CD; et al. OpenMM 7: Rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics. PLOS Computational Biology 2017, 13 (7), e1005659. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Molgaard A; Larsen S A branched N-linked glycan at atomic resolution in the 1.12 A structure of rhamnogalacturonan acetylesterase. Acta Crystallographica Section D 2002, 58 (1), 111–119. DOI: doi: 10.1107/S0907444901018479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Burmeister WP; Cottaz S; Driguez H; Iori R; Palmieri S; Henrissat B The crystal structures of Sinapis alba myrosinase and a covalent glycosyl–enzyme intermediate provide insights into the substrate recognition and active-site machinery of an S-glycosidase. Structure 1997, 5 (5), 663–676. DOI: 10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00221-9 (acccessed 2022/02/08). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Petersen TN; Kauppinen S; Larsen S The crystal structure of rhamnogalacturonase A from Aspergillus aculeatus: a right-handed parallel beta helix. Structure 1997, 5 (4), 533–544. DOI: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Aleshin AE; Hoffman C; Firsov LM; Honzatko RB Refined Crystal Structures of Glucoamylase from Aspergillus awamori var. X100. Journal of Molecular Biology 1994, 238 (4), 575–591. DOI: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lopes PEM; Huang J; Shim J; Luo Y; Li H; Roux B; MacKerell AD Polarizable Force Field for Peptides and Proteins Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2013, 9 (12), 5430–5449. DOI: 10.1021/ct400781b (acccessed 2017/05/18/19:59:03). From ACS Publications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Patel DS; He X; MacKerell AD Jr. Polarizable empirical force field for hexopyranose monosaccharides based on the classical drude oscillator. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119, 637–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lamoureux G; Harder E; Vorobyov I; Roux B; MacKerell AD Jr. A polarizable model of water for molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Chem Phys Lett 2006, 418, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Guvench O; Greene SN; Kamath G; Brady JW; Venable RM; Pastor RW; Mackerell AD Jr. Additive empirical force field for hexopyranose monosaccharides. J Comput Chem 2008, 29 (15), 2543–2564. DOI: 10.1002/jcc.21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hatcher E; Guvench O; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM additive all-atom force field for aldopentofuranoses, methyl-aldopentofuranosides, and fructofuranose. J Phys Chem B 2009, 113 (37), 12466–12476, Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural. DOI: 10.1021/jp905496e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Raman EP; Guvench O; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM additive all-atom force field for glycosidic linkages in carbohydrates involving furanoses. J Phys Chem B 2010, 114 (40), 12981–12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Patel DS; Pendrill R; Mallajosyula SS; Widmalm G; MacKerell AD Jr. Conformational properties of alpha- or beta-(1-->6)-linked oligosaccharides: Hamiltonian replica exchange MD simulations and NMR experiments. J Phys Chem B 2014, 118 (11), 2851–2871. DOI: 10.1021/jp412051v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. Journal of Chemical Physics 1983, 79 (2), 926–936. [Google Scholar]; Beglov D; Roux B Finite representation of an infinit bulk system: solvent boundary potential for computer simulations. J Chem Phys 1994, 100 (12), 9050–9063. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Tvaroška I; Hricovíni M; Petráková E An attempt to derive a new Karplus-type equation of vicinal proton-carbon coupling constants for C-O-C-H segments of bonded atoms. Carbohydrate Research 1989, 189 (Supplement C), 359–362. DOI: 10.1016/0008-6215(89)84112-6 (acccessed 2017/12/11/21:41:08). From ScienceDirect. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Huang J; Rauscher S; Nawrocki G; Ran T; Feig M; de Groot BL; Grubmuller H; MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods 2017, 14 (1), 71–73. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Langsford ML; Gilkes NR; Singh B; Moser B; Miller RC; Warren RAJ; Kilburn DG Glycosylation of bacterial cellulases prevents proteolytic cleavage between functional domains. FEBS Letters 1987, 225 (1–2), 163–167, 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81150-X. DOI: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81150-X (acccessed 2022/03/28). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.