The IL9 gene is located on chromosome 5q31-q33 in proximity to other TH2 cytokine genes important to the pathogenesis of asthma, including IL4, IL5, and IL13. Understanding the biology of the chromosome 5q cytokine genes IL4, IL5, and IL13 has led to important advances in US Food and Drug Administration–approved therapeutics for asthma targeting the cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, including therapies targeting the IL-4 receptor alpha (which inhibits IL-4 and IL-13, as both cytokines bind to the IL-4 receptor alpha), as well as therapies targeting IL-5 and the IL-5 receptor. The chromosome 5q location and the biology of IL-9 suggest that IL-9 might also be a therapeutic target in asthma based on studies of its level of expression in the airway in asthmatic individuals,1–3 as well as on studies demonstrating an asthma phenotype in mice that express increased levels of IL-9.4 For example, expression of increased levels of IL-9 in the lungs of transgenic mice causes airway inflammation, mast cell hyperplasia, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness,4 whereas IL-9–deficient mice have reductions in pulmonary mastocytosis and goblet cell hyperplasia.3 In human studies, segmental allergen challenge in patients with atopic asthma leads to increased IL-9 expression in the lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.1 In addition, increased levels of expression of IL-9 and the IL-9 receptor (IL-9R) have been detected in asthma.2

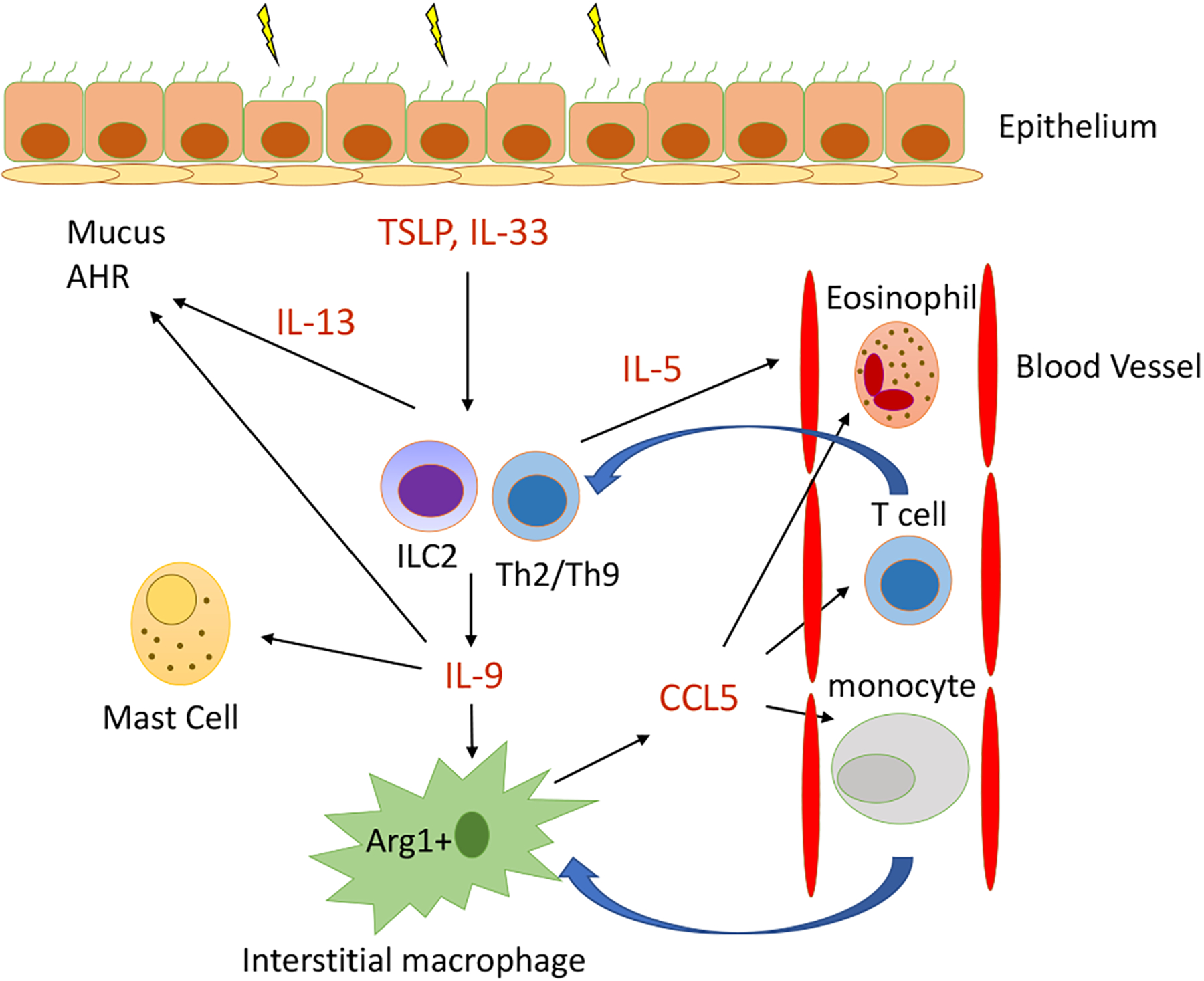

A recent study by Fu et al in Science Immunology5 provides novel insight into the mechanism by which increased IL-9 might contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma. IL-9 is produced by CD4+ TH2 and TH9 subsets, as well as by group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s)4,6 (Fig 1). However, the cellular targets and cell-specific roles of IL-9 during type 2 inflammation are not well established. Fu et al5 utilized mouse models of allergen challenge to investigate the mechanisms downstream of IL-9 that promote type 2 lung inflammation. Using IL-9R knockout (IL-9R−/−) mice, Fu et al5 demonstrate that IL-9R deficiency results in reduced eosinophilic lung inflammation and fewer lung mast cell and F4/80+ CD206+ macrophages in allergen-challenged mice. Experiments on wild-type (WT) and IL-9R−/− bone marrow chimeric mice revealed that during type 2 inflammation, hematopoietic cells contribute to IL-9 responses more so than non-hematopoietic cells do. Moreover, macrophages strongly expressed IL-9R and were found to be important IL-9 responders. Depletion of macrophages during house dust mite–induced lung inflammation led to reduced lung eosinophil counts and peribronchial infiltration, supporting an overall proinflammatory role of macrophages during allergen exposure. Interestingly, adoptive transfer of WT CD11c+ or CD11c– interstitial macrophages (IMs), but not Siglec-F+ CD11c+ alveolar macrophages, into IL-9R−/− mice restored airway hyperresponsiveness and lung inflammation. Transcriptomic studies revealed that CD11c+ lung IMs were closely related to peripheral blood monocytes and that IL-9 promoted recruitment of blood monocytes to the lung during allergic inflammation and implicated development of monocytes into lung IMs. Thus, IL-9 contributed to type 2 inflammation through IM responses and promoted recruitment of blood monocytes that resemble IMs.

FIG 1.

The IL-9/Arg1/CCL5 axis in type 2 lung inflammation. Allergens, including house dust mite and Aspergillus species, induce the alarmins thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-33, which promote IL-9 production from group 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2s). IL-9 can also be secreted from CD4+ TH2 or TH9 cells. IL-9 is known to induce mast cell accumulation, and recent work by Fu et al5 demonstrated that IL-9 induces high levels of Arg1 in lung IMs, which is required for maximal CCL5 chemokine secretion. CCL5 then recruits eosinophils, T cells, and monocytes into the lung to propagate type 2 inflammation. ILC2s and TH2 cells also produce IL-5, which stimulates eosinophil egress from bone marrow, and IL-13, which promotes mucus production, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and remodeling.

Arginase-1 (Arg1) is known to be expressed by M2 macrophage subsets that are induced during type 2 inflammation. To better understand the mechanisms by which IL-9 regulates IM responses, Fu et al5 focused on IM Arg1, given that IL-9 strongly induced macrophage Arg1 expression. Mice with macrophage-specific Arg1 deletion had reduced type 2 lung inflammation, and adoptive transfer of Arg1+ macrophages, but not Arg1−/− macrophages, into IL-9R−/− mice restored lung inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Arg1−/− and IL-9R−/− macrophages also secreted reduced levels of the chemokine CCL5 (RANTES) versus WT macrophages. CCL5 has a known role in recruitment of eosinophils, T cells, and monocytes into the lung. In translational human studies, IL-9, arginase, and CCL5 levels were elevated in samples from asthmatic children compared with in samples from controls. Further, PBMC IL-9 levels were correlated with serum CCL5 levels, suggesting that the IL-9/CCL5 axis found in mice may also be present in human asthma. Overall, the work identifies a novel pathway by which lung IMs respond to IL-9, leading to induction of Arg1 and CCL5 production, which are required for type 2 inflammation (Fig 1). As Fu et al5 point out, the role of Arg1 in allergen challenge models is controversial, and differences among strains of mice and cell-specific versus nonspecific Arg1 deletions may account for the varied findings. There are also contrasting reports regarding the proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory7 roles of macrophages during type 2 inflammation that might be explained by specific effects on macrophage subsets (M1 vs M2 and alveolar macrophages vs IMs) induced in specific models. In addition, the proinflammatory role of CCL5 has been challenged in studies in mice in which therapeutic administration of CCL5 contributes to the resolution of allergen-induced asthma by orchestrating the transition from effector GATA-3+ CD4+ T cells and inflammatory eosinophils into immunoregulatory type T cells and resident eosinophils, respectively.6 Finally, although the correlative human data presented may support the findings of Fu et al5 from mice, whether the IL-9/Arg1/CCL5 pathway contributes to human asthma remains unknown. Future studies to assess these mechanisms in patients receiving anti–IL-9 therapy could potentially provide insight.

There are 3 clinical trials of anti–IL-9 therapy in asthma that have been published in 2 reports.8,9 The first 2 clinical trials were randomized phase 2a studies in subjects with asthma; the 2 studies evaluated the safety profile and clinical activity of multiple subcutaneous doses of MEDI-528, a humanized anti–IL-9 mAb that was administered twice weekly for 4 weeks.8 The initial 2 phase 2a study populations were either adults with mild asthma (in study 1, which included 36 asthmatic subjects)10 or adults with stable, mild-to-moderate asthma, and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (in study 2, which included 11 asthmatic subjects).8 There was no statistically significant improvement in the asthma outcomes studied (asthma exacerbations, FEV1 value, exercise challenge) during the 4 week anti–IL-9 treatment period compared with in the placebo group. In both phase 2a studies, there was no difference in adverse events between the MEDI-528– and placebo-treated subjects.8

An anti–IL-9 mAb has also been studied in uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma9 as opposed to in either mild asthma or stable mild-to-moderate asthma in the initial phase 2a studies.8 In this prospective double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group study, 329 adults with confirmed uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma were randomized (1:1:1:1) to subcutaneous placebo or anti–IL-9 (MEDI-528 in doses of 30, 100, or 300 mg every 2 weeks for 24 weeks) in addition to their usual asthma medications. The primary end point was change in mean 6-Item Asthma Control Questionnaire score at week 13. The addition of MEDI-528 to existing asthma controller medications was not associated with any improvement in 6-Item Asthma Control Questionnaire scores, asthma exacerbation rates, or FEV1 values; nor was it associated with any major safety concerns.9

Thus, at present, the limited clinical trials of anti–IL-9 in asthma do not suggest it as a clinical target in patients with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma, who comprise the subset of asthmatic individuals most in need of novel therapeutics. Studies targeting IL-9 in mouse models of asthma may or may not predict similar outcomes in asthmatic humans. In addition, in murine models the cytokine signaling pathway can be genetically targeted for deletion compared with the potential partial effect of an antibody given for a restricted time under specific routes of injection in humans. Could there be an endotype of IL-9–high asthma that would respond to anti–IL-9 therapy? At present, this question remains unanswered, as none of the asthmatic subjects in the clinical trials of anti–IL-9 were endotyped as to IL-9 levels. Interestingly, the study by Fu et al demonstrated that PBMCs from asthmatic subjects expressed higher levels of IL-9 protein than did non-asthma controls.5 As there was a range of IL-9 levels detected in the PBMCs from asthmatic subjects (some high IL-9 levels and some low IL-9 levels), it may be possible to enroll study subjects in any future asthma clinical trial of anti–IL-9 using PBMC IL-9 levels as an IL-9 biomarker. In addition, as the number of IL-9–expressing allergen-specific T cells in PBMCs is greater in asthmatic individuals than in nonasthmatic individuals with house dust mite allergy as assessed by single-cell RNA sequencing,10 quantitating allergen-specific IL-9–positive T cells in PBMCs may be another method to potentially identify IL-9–responsive asthmatic individuals. If anti–IL-9 were to reduce asthma outcomes in an asthmatic population enriched for expression of IL-9, it would suggest that IL-9 may be a target in a subset of IL-9–high asthmatic individuals. However, if anti–IL-9 did not reduce asthma outcomes in such an enriched IL-9 asthma subset, it would suggest that IL-9 is not a likely therapeutic target in asthma.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI 070535, AI 107779, and AI 242236 [to D.H.B.] and AI 070535 [to T.A.D.]) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (Biomedical Laboratory R&D award BX005073 [to T.A.D.]).

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Erpenbeck VJ, Hohlfeld JM, Volkmann B, Hagenberg A, Geldmacher H, Braun A, et al. Segmental allergen challenge in patients with atopic asthma leads to increased IL-9 expression in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:1319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimbara A, Christodoulopoulos P, Soussi-Gounni A, Olivenstein R, Nakamura Y, Levitt RC, et al. IL-9 and its receptor in allergic and nonallergic lung disease: increased expression in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;105:108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakraborty S, Kubatzky KF, Mitra DK. An update on interleukin-9: from its cellular source and signal transduction to its role in immunopathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temann UA, Geba GP, Rankin JA, Flavell RA. Expression of interleukin 9 in the lungs of transgenic mice causes airway inflammation, mast cell hyperplasia, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Exp Med 1998;188:1307–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu Y, Wang J, Zhou B, Pajulas A, Gao H, Ramdas B, et al. An IL-9–pulmonary macrophage axis defines the allergic lung inflammatory environment. Sci Immunol 2022;7:eabi9768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, Mirzakhani H, Kiefer A, Koelle J, Vuorinen T, Rauh M, et al. Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) drives the resolution of allergic asthma. iScience 2021;24:103163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soroosh P, Doherty TA, Duan W, Mehta AK, Choi H, Adams YF, et al. Lung-resident tissue macrophages generate Foxp31 regulatory T cells and promote airway tolerance. J Exp Med 2013;210:775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker JM, Oh CK, LaForce C, Miller SD, Pearlman DS, Le C, et al. MEDI-528 Clinical Trials Group: safety profile and clinical activity of multiple subcutaneous doses of MEDI-528, a humanized anti-interleukin-9 monoclonal antibody, in two randomized phase 2a studies in subjects with asthma. BMC Pulm Med 2011;11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh CK, Leigh R, McLaurin KK, Kim K, Hultquist M, Molfino NA. A randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effect of an anti-interleukin-9 monoclonal antibody in adults with uncontrolled asthma. Respir Res 2013;14:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seumois G, Ramírez-Suástegui C, Schmiedel BJ, Liang S, Peters B, Sette A, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of allergen-specific T cells in allergy and asthma. Sci Immunol 2020;5:eaba6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]