Abstract

Quantitative MRI (qMRI) has been used to evaluate the structural integrity of knee joint structures. However, variations in acquisition parameters between scanners pose significant challenges. Understanding the effect of small differences in acquisition parameters for quantitative sequences is vital to the validity of cross-institutional studies, and for the harmonization of large, heterogeneous datasets to train machine learning models. The study objective was to assess the reproducibility of T2* relaxometry and the constructive interference in steady state sequence (CISS) across scanners, with minimal hardware-necessitated changes to acquisition parameters. It was hypothesized that there would be no significant differences between scanners in ACL T2* relaxation times and CISS signal intensities (SI). Secondarily, it was hypothesized that differences could be corrected by rescaling the SI distribution to harmonize between scanners. Seven volunteers were scanned on 3T Prisma and Tim Trio scanners (Siemens). Three correction methods were evaluated for T2*: inverse echo time scaling, z-scoring, and Nyúl histogram matching. For CISS, scans were normalized to cortical bone, scaled by the background noise ratio, and log-transformed. Prior to correction, significant mean differences of 6.0±3.2ms (71.8%;p=.02) and 0.49±0.15 units (40.7%;p=.02) for T2* and CISS across scanners were observed, respectively. After rescaling, T2* differences decreased to 2.6±2.7ms (23.9%;p=.03), 1.3±2.5ms (10.9%;p=.13), and 1.27±3.0ms (19.6%;p=.40) for inverse echo time, z-scoring, and Nyúl, respectively, while CISS decreased to 0.01±0.11units (4.0%; p=.87). These findings suggest that small acquisition parameter differences may lead to large changes in T2* and SI values that must be reconciled to compare data across magnets.

Keywords: MRI, T2* Relaxometry, CISS, reproducibility, harmonization

Introduction

With the increasing prevalence of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (qMRI) to perform noninvasive and objective analyses of the knee soft tissues,1–10 it is critical to understand the robustness and reproducibility of qMRI sequences frequently used across MR scanners. The scalability of qMRI methods, and the comparison of qMRI results across studies, depend on the inter-scanner reproducibility of a given sequence. Should differences across scanners be observed, it would be important to understand the source of variability, and how to correct for it.

T2* relaxometry and its variants are commonly used to evaluate the integrity of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or ACL graft post-surgery.1; 3–5; 11–13 The T2* relaxation times of the ligament or graft have been shown to reflect its structural properties,1; 3; 4 and longitudinal changes in T2* relaxation time have been associated with tissue remodeling.11; 13 The advantage of T2* relaxometry and the reason behind its recent popularity is that it is directly dependent on the collagen organization of the soft tissue of interest and is considered robust to inter-scanner bias.14

However, due to the lack of standardization of T2* sequences, acquisition parameters may vary between studies and even within a study, for reasons such as hardware differences and limitations.15 Beyond meeting minimum echo time thresholds to detect the short T2* decay of the highly organized ACL tissue, there is considerable variation in parameters across studies, such as in the number of echoes used, echo times, and the repetition time. In recent studies, for example, the flip angle ranged from 9–30°, repetition time ranged from 13–86.2ms, and first echo time ranged from 0.032–2.8ms.1; 6; 11–13

Similarly, T2*-weighted constructive interference in steady state (CISS) scans have also been associated with ACL structural properties.3; 10 While typical T2-weighted sequences are thought to have increased inter-scanner variability in the signal intensity (SI) distribution due to increased sensitivity to hardware related effects,16 this has not been empirically demonstrated for T2*-weighted CISS. In fact, inter-scan variability in CISS may be diminished by normalizing the ACL SI to a low signal reference tissue, such as cortical bone.2; 10 However, like T2* relaxometry, the sensitivity of CISS to variations in its acquisition parameters is unknown.

A number of approaches have been applied for post-acquisition harmonization of MRI scans. These range from post-processing methods that act by shifting and scaling the SI distribution to match a reference (e.g. Nyúl, z-scoring)17; 18 to machine learning-based interpolation methods.19 These approaches have shown promising results for both diffusion MRI19; 20 and radiomics,17 though MRI sequences for evaluation of the ACL, including T2* relaxometry and the CISS sequence, have not been evaluated using harmonization methods.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to assess the reproducibility of T2* relaxometry and the SI values of the CISS sequence across scanners with hardware-necessitated differences in acquisition parameters, and to evaluate harmonization methods to address these potential differences for the native ACL. The null hypothesis was that there would not be significant differences in T2* relaxation time (for T2* relaxometry) or signal intensity (for the CISS sequence) between scanners with minor differences in acquisition parameters. Secondarily, it was hypothesized that differences in T2* relaxation time and CISS SI between scanners may be corrected by harmonizing the SI distribution.

Methods

Imaging

A total of 7 healthy volunteers were recruited after the study received IRB approval (BCH: IRB-P00033650 and RIH CMTT#: 006520). All volunteers granted their informed consent. The sample size was sufficient to detect a 10% difference in T2* relaxation time or CISS SI with 80% power. The subjects were scanned on two magnets: a 3T Prisma (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at Brown University and a 3T Tim Trio (Siemens) at Boston Children’s Hospital, Waltham. A 15-channel transmit/receive coil (Siemens) was used with both scanners. A summary of acquisition parameters for both magnets is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

MRI acquisition parameters for T2* relaxometry and CISS sequences on Prisma and Tim Trio scanners.

| T2* | CISS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| MR scanner | Prisma | Tim Trio | Prisma | Tim Trio |

| Flip Angle [°] | 12 | 12 | 35 | 35 |

| Repetition Time [ms] | 29 | 29 | 12.92 | 12.78 |

| Echo Time(s) [ms] | [2.5, 6.9, 11.2, 15.6, 20, 24.4] | [3.4, 6.9, 11.2, 15.6, 20, 24.4] | 6.46 | 6.39 |

| Field of View [mm] | 160 | 160 | 130 × 160 | 140 |

| Acquisition Matrix [-] | 384 × 384 | 384 × 384 | 512 × 270 | 384 × 384 |

| Voxel Size [mm] | 0.42 × 0.42 × 0.80 | 0.42 × 0.42 × 0.80 | 0.31 × 0.31 × 1.00 | 0.36 × 0.36 × 1.50 |

Quantitative Measurements

The ACL was manually segmented from the MR image stack using commercial software (Mimics Research 19.0, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The CISS scans were segmented by one segmenter with more than 5 years of experience. The T2* scans were segmented by a separate segmenter with 4 years of experience. It was previously shown that there was no significant difference between the two segmenters and that inter-segmenter (ICC=.97) and intra-segmenter (ICC≥.97) reliability was high.21

From the CISS images, mean SI and ligament volume were extracted from the segmentation mask.1 For the T2* images, the T2* relaxation time was calculated by using a custom software package in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) to fit an exponential decay curve to the per echo SI on a voxel-wise basis.1

Post-Acquisition Harmonization

For the T2* correction, three post-processing correction methods were investigated. First, the ACL SI at each echo was scaled using the inverse echo time ratio of that echo. Second, the ACL SI was mean centered and scaled by the standard deviation of the reference sequence SI. Third, the SI histogram was scaled relative to the reference sequence standard histogram using the Nyúl algorithm.18 The Nyúl algorithm performs segmental linear histogram matching using landmarks from the reference standard histogram.17; 18 For all scaling methods, the results on the Prisma were treated as the reference, and images on the Tim Trio treated as the target to be scaled. Following SI scaling with each of these methodologies, the T2* relaxation time was recalculated in the same manner as previously described.

For the CISS scan correction, one method was assessed, which was an extension of a previously described method.2; 10 Because of the previous success of the earlier iteration of this approach, other post-processing methods were not considered for CISS.2; 10 In the original method, ACL SI was normalized to the anterior cortex of the femur, which is consistently near the noise floor. Next, the normalized SI was log-base 2 transformed because the ACL SI values were not normally distributed. To this, a background noise scaling term was added to account for differences in noise texture between steady state acquisitions. To do so, the noise was calculated from segmenting the background in the same central slice used to segment the cortical bone. Prisma scans were scaled to Tim Trio scans, which had the shorter echo time.

| Equation. 1 |

Leave-One-Out Analysis

Because the z-score and Nyúl scaling methods used references that included the subjects being scaled, an additional leave-one-out analysis was performed to validate the generalizability of these scaling methods. Each subject was successively withheld from the dataset to be used as the scaling reference. The remaining 6 subjects were then scaled with each method using the withheld subject reference, and the T2* relaxation time was recalculated.

Statistical Analysis

The differences in T2* relaxation times and CISS signal intensity values between scanners and before and after correction between scanners were assessed with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Significant differences in T2* relaxation time or SI were noted when p<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in Python using SciPy.22

Results

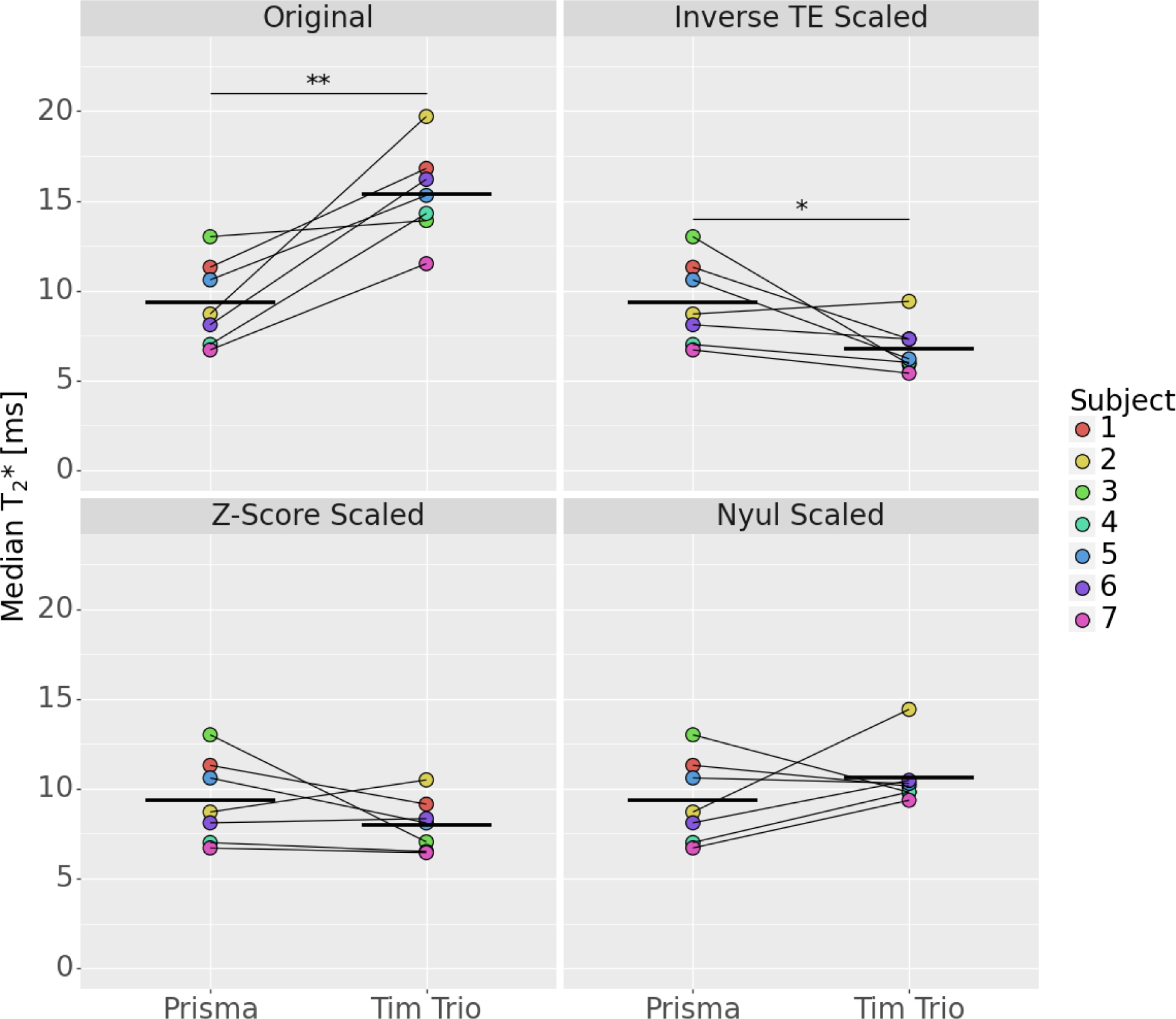

The results of the T2* scaling methods are shown in Figure 1. A mean per subject difference of 6.0±3.2ms (71.8%) in the T2* relaxation time was observed between the Tim Trio versus the Prisma scanner (p=.02). When scaling by the inverse echo time ratio, a mean per subject difference of 2.6±2.7ms (23.9%) was observed, which was significant (p=.03). When scaling by the z-score method, there was a mean per subject difference of 1.3±2.5ms (10.9%), which was not significant (p=.13). Scaling by the Nyúl algorithm resulted in a mean per subject difference of 1.27±3.0ms (19.6%), which was not significant (p=.40).

Figure 1.

T2* relaxation times from the Tim Trio before and after scaling, relative to the Prisma (bars indicate the mean value; p<.05=*; p<.005=**; p<.001=***).

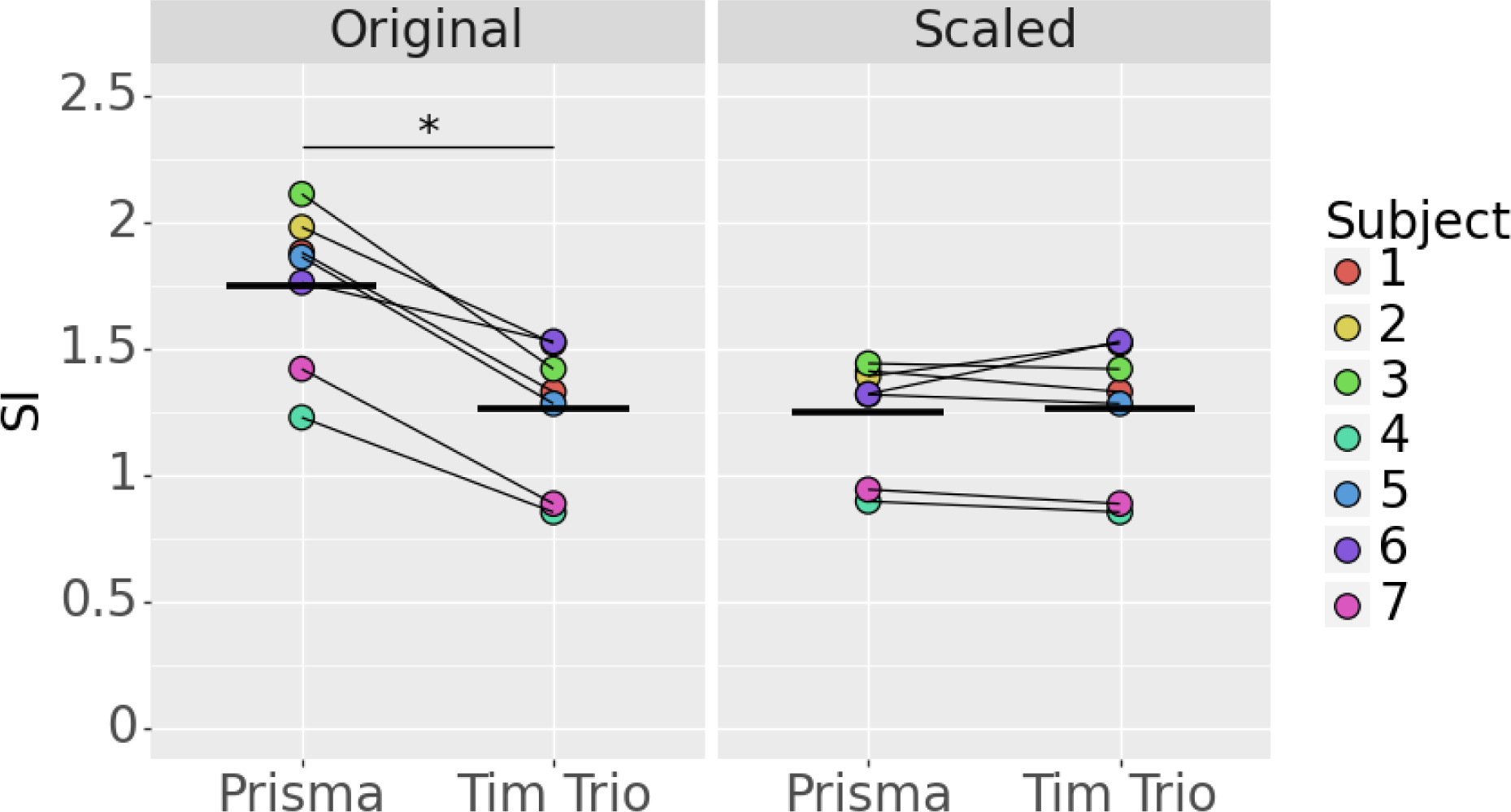

The results of CISS image SI scaling are shown in Figure 2. Prior to scaling, there was a mean per subject difference of 0.49±0.15 units (40.7%) in the CISS SI between the Tim Trio and Prisma (p=.02). After scaling, a mean per subject difference of 0.01±0.11 units (4.0%) was observed, which was not significant (p=.87).

Figure 2.

CISS signal intensity before and after normalization (bars indicate mean value; p<.05=*).

For the leave-one-out analysis of the T2* correction methods, the unscaled results were significantly different between scanners regardless of the subject withheld (Table 2). There were no significant differences between scanners when scaling with either the z-score or Nyúl method, regardless of the subject withheld as the reference.

Table 2.

Leave-one-out scaling results (p<.05 indicated in bold).

| Scaling Factor | Scaling Subject | Test Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Original | 1 | −4.332 | .007 |

| 2 | −5.066 | .004 | |

| 3 | −6.944 | .001 | |

| 4 | −4.173 | .009 | |

| 5 | −4.493 | .006 | |

| 6 | −4.189 | .009 | |

| 7 | −4.469 | .007 | |

|

| |||

| Z-Score | 1 | 0.849 | .435 |

| 2 | 1.045 | .344 | |

| 3 | 1.393 | .222 | |

| 4 | 1.532 | .186 | |

| 5 | 1.159 | .299 | |

| 6 | 1.258 | .264 | |

| 7 | 1.769 | .137 | |

|

| |||

| Nyúl | 1 | −1.311 | .247 |

| 2 | −0.747 | .489 | |

| 3 | −1.824 | .128 | |

| 4 | −0.696 | .517 | |

| 5 | −1.180 | .291 | |

| 6 | −0.858 | .430 | |

| 7 | −0.838 | .440 | |

Discussion

Significant differences were observed between scanners for both the unadjusted T2* relaxation times and CISS SI values. Increasing the first echo time by 0.9ms while holding other acquisition parameters constant between scanners resulted in increased T2* relaxation times. This increase is both statistically significant and clinically relevant. For example, in the ongoing BEAR III clinical trial (NCT03348995), the standard deviation of the mean T2* relaxation time for the repaired ACLs was 3.22ms (unpublished data). Therefore, the observed mean difference between scanners of 6.0ms represents 1.86 standard deviations in an ACL-injured cohort. This finding emphasizes the need to reconcile qMRI data across magnets, sites, and/or studies using appropriate harmonization methods.

In this study, we determined that two scaling methods for T2* relaxometry resulted in no significant differences between scanners with minor changes in acquisition parameters: z-score scaling and Nyúl scaling. Scaling by the inverse echo time ratio still resulted in significant differences in T2* relaxation time. Of the successful scaling methods, z-score scaling resulted in the smallest difference in T2* relaxation time, followed by Nyúl scaling.

Nyúl scaling presented a limitation in both the primary analysis and the leave-one-out analysis, where it compressed the range of inter-subject T2* values (Figure 1). This could pose a problem for downstream prediction models of the ligament or graft structural properties and/or surgical outcomes by decreasing sensitivity. By reducing the inter-subject range of T2* relaxation times, it may become more difficult to differentiate between outcomes using this metric. This limitation was not observed with the z-score scaling method.

The CISS sequence also demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically relevant difference between scanners/acquisition parameters. The mean difference of 0.49 units corresponds to 1.62 standard deviations in the same ACL-injured cohort. No significant difference was observed after correction. Furthermore, the post-correction difference was smaller than that for T2* (4% vs. 11% respectively). This finding highlights the potential for the CISS sequence to be used as a method of assessing the ACL in multi-scanner and multi-site settings, especially given that it has the advantages of higher spatial resolution and contrast relative to T2* relaxometry within a clinically useful acquisition time.

There are a few study limitations to consider. First, only two different Siemens scanners were evaluated. While both are commonly used, there are other manufacturers and scanner models that were not evaluated due to availability at our institutions. Second, the parameter space that qualifies as either a T2* relaxometry or CISS scan is vast relative to the differences in acquisition parameters examined here. In the present study, we sought to make acquisition parameters as similar as possible within the hardware constraints of the scanners used at the two sites. Different formulations within this parameter space may result in quantitative measures that are more, or less sensitive to the differences in acquisition parameters. It is possible that larger differences in acquisition parameters may result in measurements that are not reconcilable by harmonization. Future studies could be designed to address this issue. Other acquisition parameter modifications, such as increasing the number of echoes in the case of T2* relaxometry, may also reduce sensitivity to differences in acquisition parameters. However, this approach would only be applicable to a short T2* tissue such as the ACL if additional echoes are added within the upper echo time limit. In the present study, the T2* sequence used was already implemented with the minimum echo time interval. For the CISS images, normalizing to the femoral cortical bone may show decreased efficacy in elderly patients with osteoporosis, diabetes, HIV, or other conditions resulting in degenerative changes to cortical bone architecture and composition.23–25 These bone alterations result in changes to MR properties of the bone, such as an increase in magnetic susceptibility.23 However, ACL injuries are most common in adolescent patients and active young adults who typically have good bone quality.26–29 Lastly, some of the variation observed may be due to segmenter reproducibility. To address this potential issue, only experienced segmenters with validated reliability were used for this study. On a relatively large tissue such as the ACL (~10,000 voxels), median T2* relaxation time and median CISS SI are insensitive to segmentation variability.21 Furthermore, the observed inter-scanner effect sizes for both T2* relaxometry and CISS sequence far exceeded previous measures of inter- and intra-segmenter reliability.21

These study results emphasize the need for post-acquisition harmonization of qMRI measures of the ACL when performed on different scanners and across institutions, as commonly is the case in multicenter studies. In a systematic review, Van Dyck et al. showed a wide range of MRI sequences and acquisition parameters used for evaluation of the ACL.15 A more cursory review of the literature specific to T2* relaxometry (Supplementary Table 1) also indicates a wide variation in T2* acquisition parameters for quantitative measurements of the ACL. A minimum requirement for measurement of T2* decay in the ACL is a first echo time less than 10ms,13 but besides this consideration there is no standardization in echo times, repetition time, flip angle, voxel size, etc. This is due in part to a combination of hardware limitations requiring sequence modifications across scanners,16 and the balancing of unavoidable tradeoffs between signal-to-noise ratio, resolution, and acquisition time, among other challenges.14

Differences in measures of both T2* relaxation time and CISS SI values due to different hardware and acquisition parameters may propagate into large errors in downstream prediction models of ligament or graft structural properties and/or surgical outcomes.1–5 In addition, due to the lack of standardization of qMRI sequences, comparisons of results between studies utilizing different acquisition parameters or hardware without harmonization would be limited. Furthermore, to leverage large, heterogeneous qMRI datasets for training machine learning models (e.g., for predicting ACL failure load), harmonization will likely be necessary. In the present study, when acquisition parameters were set to the minimum hardware-necessitated differences, z-score scaling was an effective method for harmonizing differences in T2* relaxation time. Scaling CISS SI by the difference in background noise effectively harmonized CISS. In the future, harmonization methods could be added to standard post-processing software for both clinical and research applications. Emphasis should also be placed on the standardization of qMRI acquisition parameters should be sought to preemptively alleviate this reproducibility challenge.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Boston Children’s Hospital Orthopaedic Surgery Foundation, the RIH Orthopaedic Foundation, the Bioengineering Core of the COBRE for Skeletal Health and Repair (NIGMS P30-GM122732), the COBRE Center for Central Nervous System Function (NIGMS 1P20GM103645-01), and the Lucy Lippitt Endowment of Brown University. We would like to thank Lynn Fanella at the Brown MRI Research Facility and Kristina Pelkola at BCH for running the acquisitions for this study.

MMM is a founder and equity holder in Miach Orthopaedics, Inc, which was formed to commercialize the BEAR scaffold. AMK is a paid consultant of Miach Orthopaedics, and on the editorial board for BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. BCF is an associate editor for The American Journal of Sports Medicine, a founder of Miach Orthopaedics, and the spouse of MMM who has the previously stated conflicts. EGW is a co-founder of Theromics, Inc.

References

- 1.Beveridge JE, Machan JT, Walsh EG, et al. 2018. Magnetic resonance measurements of tissue quantity and quality using T2* relaxometry predict temporal changes in the biomechanical properties of the healing ACL. J Orthop Res 36:1701–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biercevicz AM, Akelman MR, Fadale PD, et al. 2015. MRI volume and signal intensity of ACL graft predict clinical, functional, and patient-oriented outcome measures after ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 43:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biercevicz AM, Miranda DL, Machan JT, et al. 2013. In Situ, noninvasive, T2*-weighted MRI-derived parameters predict ex vivo structural properties of an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction or bioenhanced primary repair in a porcine model. Am J Sports Med 41:560–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biercevicz AM, Murray MM, Walsh EG, et al. 2014. T2* MR relaxometry and ligament volume are associated with the structural properties of the healing ACL. J Orthop Res 32:492–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biercevicz AM, Proffen BL, Murray MM, et al. 2015. T2* relaxometry and volume predict semi-quantitative histological scoring of an ACL bridge-enhanced primary repair in a porcine model. J Orthop Res 33:1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Nazaran A, Ma Y, et al. 2019. Single- and Bicomponent Analyses of T2 Relaxation in Knee Tendon and Ligament by Using 3D Ultrashort Echo Time Cones (UTE Cones) Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biomed Res Int 2019:8597423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Titchenal MR, Williams AA, Chehab EF, et al. 2018. Cartilage subsurface changes to magnetic resonance imaging UTE-T2* 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction correlate with walking mechanics associated with knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 46:565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams A, Qian Y, Golla S, et al. 2012. UTE-T2* mapping detects sub-clinical meniscus injury after anterior cruciate ligament tear. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20:486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams AA, Titchenal MR, Andriacchi TP, et al. 2018. MRI UTE-T2* profile characteristics correlate to walking mechanics and patient reported outcomes 2 years after ACL reconstruction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 26:569–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray MM, Kiapour AM, Kalish LA, et al. 2019. Predictors of healing ligament size and magnetic resonance signal intensity at 6 months after bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair. Am J Sports Med 47:1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CR, Williams AA. 2019. Quantitative MRI UTE-T2* and T2* show progressive and continued graft maturation over 2 years in human patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med 7:2325967119863056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda T, Wengler K, Tank D, et al. 2019. Abbreviated quantitative UTE imaging in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warth RJ, Zandiyeh P, Rao M, et al. 2020. Quantitative Assessment of In Vivo Human Anterior Cruciate Ligament Autograft Remodeling: A 3-Dimensional UTE-T2* Imaging Study. Am J Sports Med 48:2939–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McRobbie DW, Moore EA, Graves MJ. 2017. MRI from picture to proton;

- 15.Van Dyck P, Zazulia K, Smekens C, et al. 2019. Assessment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft Maturity With Conventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Systematic Literature Review. Orthop J Sports Med 7:2325967119849012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deoni SCL, Williams SCR, Jezzard P, et al. 2008. Standardized structural magnetic resonance imaging in multicentre studies using quantitative T1 and T2 imaging at 1.5 T. Neuroimage 40:662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carre A, Klausner G, Edjlali M, et al. 2020. Standardization of brain MR images across machines and protocols: bridging the gap for MRI-based radiomics. Sci Rep 10:12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyul LG, Udupa JK, Xuan Z. 2000. New variants of a method of MRI scale standardization. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 19:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ning L, Bonet-Carne E, Grussu F, et al. 2020. Cross-scanner and cross-protocol multi-shell diffusion MRI data harmonization: Algorithms and results. Neuroimage 221:117128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirzaalian H, Ning L, Savadjiev P, et al. 2018. Multi-site harmonization of diffusion MRI data in a registration framework. Brain Imaging Behav 12:284–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flannery SW, Kiapour AM, Edgar DJ, et al. 2020. Automated magnetic resonance image segmentation of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Orthop Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, et al. 2020. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 17:261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sollmann N, Löffler MT, Kronthaler S, et al. 2021. MRI -Based Quantitative Osteoporosis Imaging at the Spine and Femur. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 54:12–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biver E, Calmy A, Delhumeau C, et al. 2014. Microstructural alterations of trabecular and cortical bone in long-term HIV-infected elderly men on successful antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 28:2417–2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samelson EJ, Demissie S, Cupples LA, et al. 2018. Diabetes and Deficits in Cortical Bone Density, Microarchitecture, and Bone Size: Framingham HR-pQCT Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 33:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nordenvall R, Bahmanyar S, Adami J, et al. 2012. A population-based nationwide study of cruciate ligament injury in Sweden, 2001–2009: incidence, treatment, and sex differences. Am J Sports Med 40:1808–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen KW, Orchard JW, Driscoll TR, et al. 2012. High incidence and costs for anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions performed in Australia from 2003–2004 to 2007–2008: time for an anterior cruciate ligament register by Scandinavian model? Scand J Med Sci Sports 22:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granan LP, Forssblad M, Lind M, et al. 2009. The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004–2007: baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthop 80:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders TL, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan AJ, et al. 2016. Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Sports Med 44:1502–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.