Abstract

Purpose of Review

Given the continued controversy among orthopedic surgeons regarding the indications and benefits of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM), this review summarizes the current literature, indications, and outcomes of partial meniscectomy to treat symptomatic meniscal tears.

Recent Findings

In patients with symptomatic meniscal tears, the location and tear pattern play a vital role in clinical management. Tears in the central white-white zone are less amenable to repair due to poor vascularity. Patients may be indicated for APM or non-surgical intervention depending on the tear pattern and symptoms. Non-surgical management for meniscal pathology includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy (PT), and intraarticular injections to reduce inflammation and relieve symptoms. There have been several landmark multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studying the outcomes of APM compared to PT or sham surgery in symptomatic degenerative meniscal tears. These most notably include the 2013 Meniscal Tear in Osteoarthritis Research (MeTeOR) Trial, the 2018 ESCAPE trial, and the sham surgery-controlled Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY), which failed to identify substantial benefits of APM over nonoperative treatment or even placebo surgery.

Summary

Despite an abundance of literature exploring outcomes of APM for degenerative meniscus tears, there is little consensus among surgeons about the drivers of good outcomes following APM. It is often difficult to determine if the presenting symptoms are secondary to the meniscus pathology or the degenerative disease in patients with concomitant OA. A central tenet of managing meniscal pathology is to preserve tissue whenever possible. Most RCTs show that exercise therapy may be non-inferior to APM in degenerative tears if repair is not possible. Given this evidence, patients who fail nonoperative treatment should be counseled regarding the risks of APM before proceeding to surgical management.

Keywords: Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, Sham surgery, Degenerative tear, Traumatic tear, Meniscal tear, Osteoarthritis, Physical therapy

Introduction

The menisci are wedge-shaped fibro-cartilaginous structures that play a crucial role in absorbing shock and distributing loads throughout the knee joint. Though previously dismissed as developmental remnants in early medical literature, our modern understanding of the menisci has instead shown that they serve a protective function in the joint and that meniscal pathology is linked to the early onset of osteoarthritis (OA) [1, 2]. Meniscal pathology, which encompasses both acute and degenerative meniscal tears, is a relatively common source of knee pain and dysfunction in the general population. The incidence of meniscus tears in the USA has been estimated at 12–14% of the population per year, with 61 cases per 100,000 persons [3]. Furthermore, knee arthroscopy to treat meniscal pathology is the third most common elective orthopedic procedure in the USA after total knee and hip arthroplasty (TKA and THA) [4]. An arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) is a high-volume procedure, with over 500,000 surgeries performed annually in the USA. Despite an estimated cost of around $3,800 per case and declining rates of meniscectomy in favor of non-operative treatment or meniscus repair over the past two decades, APM remains one of the most widely used surgical treatments for symptomatic meniscus tears [5••, 6–9].

Much of the controversy surrounding APM centers on the abundant but inconclusive literature on its use in patients with underlying degenerative joint disease (DJD) as well as younger patients who have irreparable tears [5••, 10, 11•, 12, 13••]. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted over the past two decades, most notably the Meniscal Tear in Osteoarthritis Research (MeTeOR) Trial and the Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY), failed to identify substantial benefits of APM over nonoperative treatment or even placebo surgery [5••, 13••, 14•]. Further debate has emerged surrounding revised guidelines issued by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in 2021, which stated that APM could be used for “the treatment of meniscal tears in patients with concomitant mild to moderate OA who have failed physical therapy or other non-surgical treatments.” This statement drew criticism since the evidence used to support it came from just three RCTs which demonstrated the non-inferiority of physical therapy compared to APM [15–17]. Other opinion pieces have further disputed the evidence for and against the use of APM for meniscus pathology, with some defending the use of sham surgery as a comparison group and others opposing the practice [18–21]. The present review aims to summarize the most current literature on the use of APM to treat meniscal pathology, particularly in patients with preexisting degenerative joint disease, and provide context for the ongoing debate about appropriate indications for this procedure.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

Grossly, the menisci consist of two wedge-like structures composed of fibrocartilaginous tissue, which articulate inferiorly with the tibial plateau and superiorly with the femoral condyles. In a normal knee, the menisci distribute axial loads, absorb shocks, lubricate the joint, and contribute to stability [22]. The vascular anatomy of the menisci has a significant impact on lesion healing potential and thus management. The red zone (or red-red zone) is the well-vascularized peripheral border of the meniscus. The white zone (or white-white zone) is the thin, poorly vascularized innermost border. The transitional space between these two zones is known as the red-white zone [22–24]. Lesions of the red-red zone have the highest healing potential, and thus meniscal repair is the preferred surgical approach [24, 25]. Lesions in the white-white zone are highly unlikely to heal due to the poor blood supply, and therefore excision of the torn tissue with partial meniscectomy is preferred [24, 25]. Management of red-white zone lesions is more controversial, and some surgeons variably opt for repair versus excision. However, long-term outcomes of repairs of meniscal tears in the red-white zone lesion show comparable outcomes to those of red-red zone [26–29].

A major biomechanical concern following APM is that any loss of meniscal tissue may significantly alter the biomechanics of the knee joint, leading to abnormal loading of the tibiofemoral joint and increased risk of secondary OA [30–33]. Multiple cadaveric studies have found APM to have a detrimental impact on joint biomechanics, with several studies reporting an increase in tibiofemoral contact pressures by up to 80–90% as more meniscal tissue is removed [34]. Clinical studies have also identified alterations in gait kinematics among patients who have undergone APM [35]. Sturnieks et al. conducted a prospective analysis of knee joint biomechanics in a cohort of APM patients versus healthy controls. They found that while both groups were generally similar in terms of spatiotemporal parameters and knee kinematics, the APM group had significantly larger adduction moments over stance, which could contribute to higher medial compartment loading [35]. Starkey et al. conducted a secondary analysis of an RCT to determine whether a 12-week exercise regimen could reduce peak contact forces in patients who had undergone medial APM but found no significant change in peak loads compared to a no-exercise control group [36]. Multiple cohort studies with follow-up greater than 15 years have identified higher rates of radiographic OA among post-meniscectomy patients versus controls [37]. As a result, treatment guidelines have increasingly prioritized the preservation of meniscus tissue with repair instead of excision in order to maintain native biomechanics and reduce the risk of OA.

Natural History

While there is no agreed-upon definition for a traumatic, a generally accepted definition is the following: a tear that occurs in an otherwise healthy meniscus following a specific event or injury. Most of these lesions have a vertical or radial tear pattern [38]. On the other hand, degenerative meniscus tears are described as slowly developing meniscal lesions resulting from repetitive forces, involving a horizontal cleavage pattern of the menisci, and are most commonly seen in older patients. Over time, stress forces result in reduced meniscal cellularity and disruption of collagenous fibers [39, 40]. These lesions are common incidental findings on MRI and have been documented in up to 35% of the general population over 50 years, with the incidence increasing to 60% in patients with underlying radiographic evidence of OA [2, 41]. Given that meniscus tears and OA often co-exist and share common risk factors like obesity, overuse, and history of injury; there remains significant controversy regarding whether degenerative meniscal tears lie on the causal pathway of OA [42, 43]. In a longitudinal study of the natural history of meniscus tears conducted over 8 years, Khan et al. demonstrated that tear progression was independently associated with an increase in knee pain and structural damage, suggesting a relationship between meniscus tears and knee OA [44]. Additionally, because the pathophysiology of these lesions is poorly understood, it is difficult for clinicians to ascertain whether the meniscal tear is a contributor to the patient’s OA-related pain or if it is a cause of the degenerative processes within the knee. Despite the high prevalence of meniscal tears in patients over 50 years, only 2/3 of these lesions are symptomatic [41]. Menisci possess nociceptive innervation in the periphery, which may lend meniscus tears the ability to cause pain [44]. However, studies have shown conflicting results in this regard. Bhattacharya et al. demonstrated that osteoarthritic knee patients with meniscal tears reported similar pain levels to OA patients without meniscal tears [45].

In a multicenter OA study, Englund et al. demonstrated an association between meniscus pathology and knee pain, aching, and stiffness in patients over 50 years old. However, meniscus damage was present with concomitant OA in most cases, and when considered in concert, no independent relationship between knee symptoms and meniscal pathology was demonstrated [46, 47]. In addition, studies have shown that there is no clear relationship between the presence of structural meniscal pathology on MRI and patient-reported pain and functional outcomes [48]. A finding that calls into question the utility of APM in patients with recorded meniscal pathology on imaging.

Indications

Despite baseline differences in patient demographics and tissue health, treatment modalities remain the same for both traumatic and degenerative injuries. In the case of traumatic tears, patients presenting with a tear in the avascular zone of the meniscus, are often indicated for APM. The management of degenerative meniscal tears remains a more controversial topic. Despite the evidence pointing to the non-inferiority of physical therapy compared to APM, the volume of meniscectomies performed in the USA continues to grow [8, 9]. Key factors in clinical decision-making include the presence of mechanical symptoms, tear pattern on preoperative imaging (Fig. 1), degree of OA, and age. Many cite that the presence of mechanical symptoms is a clear indication for performing APM; however, in the absence of a locked knee, patient-reported sensation of locking or catching was not found to be specific to meniscal tear on arthroscopy and was not found to modify the outcomes of APM [47, 49].

Fig. 1.

Preoperative MRI showing horizontal component of complex medial meniscus tear denoted by yellow arrow

Identification of patients who can benefit from surgical intervention can be challenging. A recent physician survey by Van de Graaf et al. reported that among orthopedic surgeons in the Netherlands, surgeons were better at identifying patients who would respond well to APM; however, they had lower success identifying patients who did not improve following surgery. This led the authors to speculate that surgeons were overly optimistic regarding APM outcomes, and despite successfully identifying those who are appropriate for surgical intervention, there seemed to be little consensus regarding which factors would contraindicate surgery [50].

In 2017, the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery & Arthroscopy (ESSKA) published the first European consensus for treating symptomatic degenerative meniscal lesions. The main conclusion of this statement was that APM should not be considered a first-line treatment for patients presenting with meniscal tears in the setting of degenerative disease of the knee [51]. The main reason cited was difficulty assessing whether the patient reported pain is secondary to the meniscal pathology or if the pain is simply a symptom of early OA [48]. Similarly, the British Association for Surgery of the Knee (BASK) assembled the Meniscal Working Group in 2016, and 2018, which published treatment guidelines indicating meniscectomy for irreparable bucket handle, displaced tears, root tears, patients with a locked knee, or those who exhibit meniscal symptoms persisting beyond 3 months [52]. In their recently published guidelines for the management of knee OA, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) suggested there is moderate evidence that APM is appropriate for treatment for meniscal tears in patients with preexisting mild to moderate OA [53].

Management and Outcomes

Options for non-surgical management of irreparable meniscal tears include physical therapy, NSAIDs, corticosteroid injections, hyaluronic acid, and orthobiologics such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Currently, surgical management of meniscal tears prioritizes preservation and repair of meniscal tissue. However, APM continues to be a common procedure for managing degenerative meniscal tears (Fig. 2). Despite its minimally invasive nature, APM is not without its risk of complications; Salzler et al. found the prevalence of complications following meniscectomy to be 2.4%, including medical, surgical, and anesthesia-related [54].

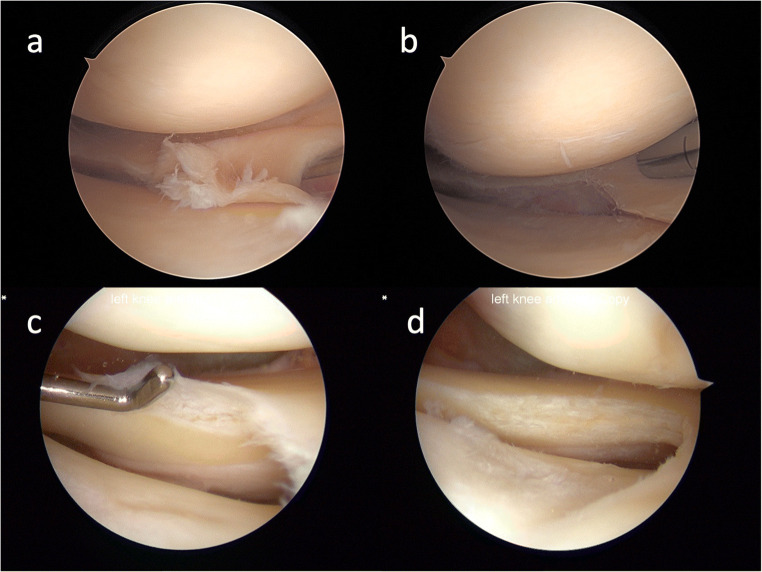

Fig 2.

a View from the anterolateral viewing portal showing a complex tear of the medial meniscus. b View of the complex tear following the meniscectomy. c View from the anteromedial viewing portal showing a cleavage tear of the lateral meniscus. d View of the cleavage tear following the meniscectomy

There is little evidence examining outcomes following APM for traumatic meniscal tears. The literature is limited to cohort studies comparing outcomes of APM in traumatic vs. degenerative tears; however, results have been conflicting, with some groups reporting no differences between groups [55], others reporting superior outcomes in traumatic tears [56], and others superior outcomes in degenerative tears [57]. On the other hand, over the past two decades, 12 RCTs have studied the outcomes of APM compared to physical therapy and sham surgery for degenerative meniscal tears [11•, 13••, 14•, 58–63].

Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy vs. Physical Therapy

One of the first RCTs to explore the efficacy of APM for meniscus tears in patients with underlying OA was the 2007 study by Herrlin et al., which prospectively enrolled 90 patients with nontraumatic medial meniscus tears. Patient-reported outcomes were obtained at enrollment, including Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Tegner activity level, and visual analog scale (VAS) for pain. PT was found to be non-inferior to APM at the 6-month follow-up timepoint, and both arms of the study experienced statistically significant improvement in KOOS, Lysholm Knee Score, and decreases in pain.

Similarly, a 2018 multicenter RCT by Van de Graaf et al. (ESCAPE Trial) enrolled 321 subjects with mild to moderate OA and randomized them to APM or physical therapy. IKDC was used to measure improvement at 24 months. By 24 months, 29% of the PT cohort had crossed over to the APM arm of the study. There were no significant differences in IKDC scores between groups [64]. These results mirror those of other RCTs, including Kirkley et al., Yim et al., and Kise et al., concluding that exercise therapy is non-inferior to APM for treating degenerative meniscus tears [11•, 61, 65].

Another landmark study was the 2013 multicenter RCT by Katz et al., the MeTeOR trial. This group enrolled patients over 45 years of age presenting with a meniscal tear and evidence of concomitant knee OA. A total of 351 patients were enrolled and randomized into PT alone or APM plus PT postoperatively. At 6 months follow-up, 30% of those randomized to the physical therapy arm crossed over and underwent APM; intention to treat analysis revealed that differences in WOMAC score from baseline were not significantly different between groups at 6 months [60]. However, the high rate of crossover in the MeTeOR trial and other studies such as those by Van de Graaf et al. and Herrlin et al. is considered a major limitation and is often taken to imply that symptoms persist following conservative interventions [14•, 50, 58–60].

Only one trial has shown improved outcomes following APM for degenerative meniscal tears. Gauffin et al. found that among middle-aged individuals with 3 months of symptomatic meniscal tear, those who underwent APM showed lower KOOS pain scores at 3 months and 1 year from baseline than those assigned to a PT-only regimen. However, these findings were not sustained at 3-year, or 5-year follow-up, where any additional benefit conferred by APM was not detectable. In line with these findings, a 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis by Abram et al. found evidence that when compared to exercise therapy, APM may confer improvements in knee function and pain in patients without evidence of underlying OA preoperatively [66].

Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy vs. Sham Surgery

In 2002 Moseley et al. were among the first to conduct a blinded RCT comparing the effectiveness of intraarticular interventions, including partial meniscectomy, chondroplasty, and loose body removal, compared to incision-only sham surgery. This study found early improvement in the surgical arm of the study, but the improvements were undetectable on long-term follow-up [63]. This early trial led to further multicenter sham-controlled studies looking to explore the effect of placebo surgery on meniscal pathology.

In the 2013 multicenter double-blind randomized controlled FIDELITY trial, Sihvonen et al. randomly assigned a cohort of patients with degenerative meniscal tears to receive either APM or sham surgery. This study found that at 12 months follow-up, both groups had experienced an improvement in symptoms from baseline, and there were no between-group differences in Lysholm or Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET) scores [13••, 67]. At 5-year-follow-up, Sihvonen et al. found an increased risk of progression of OA in subjects who underwent APM. However, these were not related to clinical or statistically significant differences in WOMET or knee pain scores [5••].

In 2018, Roos et al. published the results of a multicenter RCT comparing APM to sham surgery (skin incision only). This study found that patients who underwent APM at 2 years of follow-up reported greater improvement assessed by KOOS than the incision-only group. However, this study had severe limitations. It was underpowered, with a high rate of crossover from the sham surgery group to APM (36%) and high rates of unblinding prior to follow-up. Roos and co-authors found that patients who underwent incision-only procedures reported higher KOOS scores in the per-protocol analysis at 3 months [12••]. These findings contrast those of the FIDELITY trial, which found no differences in outcomes between study arms [13••]. It should be noted that sham surgery in the FIDELITY trial consisted of manipulating the knee and inserting arthroscopic instruments for the duration of a standard APM. Conversely, in the study by Roos et al., sham surgery consisted of performing a skin incision under anesthesia, suggesting that postoperative morbidity following APM may be related to the trauma associated with intraarticular surgical instrumentation [12••, 13••].

Conclusion

The available literature and professional guidelines surrounding APM for degenerative meniscus tears overwhelmingly demonstrate that exercise therapy and sham surgery are non-inferior to APM for the treatment of degenerative meniscus tears and suggest delaying surgery until nonoperative modalities have been exhausted. Despite some evidence that APM may confer early benefit for patients without OA, physicians must ensure that patients are properly counseled on the risks of undergoing APM including progression of DJD, increased risk of progression to TKA, and failure of symptoms to resolve.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Amanda Avila declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Kinjal Vasavada declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Dhruv Shankar declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Laith M. Jazrawi has received consulting fees from Flexion Therapeutics; research support from Arthrex, Mitek, and Smith & Nephew; and education support from Gotham Surgical and Arthrex.

Eric J Strauss has received consulting fees from Arthrex, Fidia, Flexion Therapeutics, the Joint Restoration Foundation, Organogenesis, Smith & Nephew, Subchondral Solutions, and Vericel; research support from Fidia, Organogenesis, and CartiHeal.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Meniscus

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;252:19–31. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englund M, Guermazi A, Lohmander SL. The role of the meniscus in knee osteoarthritis: a cause or consequence? Radiol Clin N Am. 2009;47(4):703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ, Godges J. Knee pain and mobility impairments: meniscal and articular cartilage lesions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(6):A1–597. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina CS, Thakore RV, Blumer A, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Use of the national surgical quality improvement program in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1574–1581. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3597-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Kalske J, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 5 year follow-up of the placebo-surgery controlled FIDELITY (Finnish Degenerative Meniscus Lesion Study) trial. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(22):1332–1339. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnds B, Morris B, Mullen S, Schroeppel JP, Tarakemeh A, Vopat BG. Increased rates of knee arthroplasty and cost of patients with meniscal tears treated with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus non-operative management. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2316–2321. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery SR, Zhang A, Ngo SS, Wang JC, Hame SL. Cross-sectional analysis of trends in meniscectomy and meniscus repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(8):e1007–e1013. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130724-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333–2339. doi: 10.1177/0363546513495641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker BR, Hurwitz S, Spang J, Creighton R, Kamath G. Surgical trends in the treatment of meniscal tears: analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification Examination Database. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1717–1723. doi: 10.1177/0363546516638082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abram SGF, Judge A, Beard DJ, Price AJ. Adverse outcomes after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a study of 700 000 procedures in the national Hospital Episode Statistics database for England. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2194–2202. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31771-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.• Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, Ranstam J, Engebretsen L, Roos EM. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ. 2016:i3740. 10.1136/bmj.i3740Randomized controlled trial to determine if APM was superior to PT in patients with degenerative meniscal tears. No difference in KOOS4 between groups at 2 years; PT group showed greater quadriceps strength than APM group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Roos EM, Hare KB, Nielsen SM, Christensen R, Lohmander LS. Better outcome from arthroscopic partial meniscectomy than skin incisions only? A sham-controlled randomised trial in patients aged 35-55 years with knee pain and an MRI-verified meniscal tear. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019461. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2515–2524. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1305189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz JN, Shrestha S, Losina E, Jones MH, Marx RG, Mandl LA, et al. Five-year outcome of operative and nonoperative management of meniscal tear in persons older than forty-five years. Arthritis Rheum. 2020;72(2):273–281. doi: 10.1002/art.41082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leopold SS. Editorial: Appropriate use? Guidelines on arthroscopic surgery for degenerative meniscus tears need updating. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(5):1283–1286. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leopold SS. Editorial: The new AAOS guidelines on knee arthroscopy for degenerative meniscus tears are a step in the wrong direction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;480(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000002068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AAOS Practice Guidelines: osteoarthirtis of the knee. AmericAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/osteoarthritis-of-the-knee/oak3cpg. Acessed 21 Feb 2021.

- 18.Carr A. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee. BMJ. 2015;350:h2983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchbinder R. Meniscectomy in patients with knee osteoarthritis and a meniscal tear? N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1740–1741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1302696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubowitz JH, Provencher MT, Rossi MJ. Could the New England Journal of Medicine be biased against arthroscopic knee surgery? Part 2. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):654–655. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Järvinen TLN, Guyatt GH. Arthroscopic surgery for knee pain. BMJ. 2016;354:i3934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox AJS, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of human knee menisci: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health. 2012;4(4):340–351. doi: 10.1177/1941738111429419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mordecai SC, Al-Hadithy N, Ware HE, Gupte CM. Treatment of meniscal tears: an evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):233–241. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhan K. Meniscal tears: Current understanding, diagnosis, and management. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8590-e. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, Nizard R, Nourissat G, Pujol N. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2009;95(6):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaufils P, Pujol N. Management of traumatic meniscal tear and degenerative meniscal lesions. Save the meniscus. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(8s):S237–Ss44. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH. Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthrosc: J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2011;27(9):1275–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pihl K, Englund M, Christensen R, Lohmander LS, Jørgensen U, Viberg B, et al. Less improvement following meniscal repair compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a prospective cohort study of patient-reported outcomes in 150 young adults at 1- and 5-years’ follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2021;92(5):589–596. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2021.1917826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber J, Koch M, Angele P, Zellner J. The role of meniscal repair for prevention of early onset of osteoarthritis. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baratz ME, Fu FH, Mengato R. Meniscal tears: the effect of meniscectomy and of repair on intraarticular contact areas and stress in the human knee. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(4):270–275. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bargar WL, Moreland JR, Markolf KL, Shoemaker SC, Amstutz HC, Grant TT. In vivo stability testing of post-meniscectomy knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;150:247–252. doi: 10.1097/00003086-198007000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SJ, Aadalen KJ, Malaviya P, Lorenz EP, Hayden JK, Farr J, et al. Tibiofemoral contact mechanics after serial medial meniscectomies in the human cadaveric knee. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1334–1344. doi: 10.1177/0363546506286786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papalia R, Del Buono A, Osti L, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2011;99(1):89–106. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeley BT, Lau BC. Biomechanics and clinical outcomes of partial meniscectomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(24):853–863. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-17-00256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sturnieks DL, Besier TF, Mills PM, Ackland TR, Maguire KF, Stachowiak GW, et al. Knee joint biomechanics following arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(8):1075–1080. doi: 10.1002/jor.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starkey SC, Lenton GK, Saxby DJ, Hinman RS, Bennell KL, Wrigley T, et al. Effect of exercise on knee joint contact forces in people following medial partial meniscectomy: a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Gait Posture. 2020;79:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, Tu X, Amin S, Clancy M, et al. The association of meniscal pathologic changes with cartilage loss in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):795–801. doi: 10.1002/art.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poehling GG, Ruch DS, Chabon SJ. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(3):539–549. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5919(20)30705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pauli C, Grogan SP, Patil S, Otsuki S, Hasegawa A, Koziol J, et al. Macroscopic and histopathologic analysis of human knee menisci in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19(9):1132–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mesiha M, Zurakowski D, Soriano J, Nielson JH, Zarins B, Murray MM. Pathologic characteristics of the torn human meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(1):103–112. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, Hunter DJ, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1108–1115. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Englund M, Felson DT, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Wang K, Crema MD, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscal pathology on knee MRI in older US adults: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1733–1739. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding C, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Abram F, Raynauld JP, Cicuttini F, et al. Meniscal tear as an osteoarthritis risk factor in a largely non-osteoarthritic cohort: a cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(4):776–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan HI, Aitken D, Ding C, Blizzard L, Pelletier J-P, Martel-Pelletier J, et al. Natural history and clinical significance of meniscal tears over 8 years in a midlife cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0862-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, Totterman S, Gale ME, McLaughlin S, et al. The clinical importance of meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee*. JBJS. 2003;85(1):4–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Englund M, Niu J, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Hunter DJ, Lynch JA, et al. Effect of meniscal damage on the development of frequent knee pain, aching, or stiffness. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4048–4054. doi: 10.1002/art.23071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorlund JB, Pihl K, Nissen N, Jørgensen U, Fristed JV, Lohmander LS, et al. Conundrum of mechanical knee symptoms: signifying feature of a meniscal tear? Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(5):299–303. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tornbjerg SM, Nissen N, Englund M, Jørgensen U, Schjerning J, Lohmander LS, et al. Structural pathology is not related to patient-reported pain and function in patients undergoing meniscal surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(6):525–530. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macfarlane LA, Yang H, Collins JE, Guermazi A, Jones MH, Teeple E, et al. Associations among meniscal damage, meniscal symptoms and knee pain severity. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(6):850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van De Graaf VA, Bloembergen CH, Willigenburg NW, Noorduyn JCA, Saris DB, Harris IA, et al. Can even experienced orthopaedic surgeons predict who will benefit from surgery when patients present with degenerative meniscal tears? A survey of 194 orthopaedic surgeons who made 3880 predictions. Br J Sports Med. 2019:bjsports-2019-1. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Beaufils P, Becker R, Kopf S, Englund M, Verdonk R, Ollivier M, et al. Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: the 2016 ESSKA Meniscus Consensus. Joints. 2017;05(02):059–069. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abram SGF, Beard DJ, Price AJ. National consensus on the definition, investigation, and classification of meniscal lesions of the knee. Knee. 2018;25(5):834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Surgeons AAoO. Management of osteoarthritis of the knee (non-arthroplasty) evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 3rd ed2021.

- 54.Salzler MJ, Lin A, Miller CD, Herold S, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Complications after arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):292–296. doi: 10.1177/0363546513510677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lizaur-Utrilla A, Miralles-Muñoz FA, Gonzalez-Parreño S, Lopez-Prats FA. Outcomes and patient satisfaction with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative and traumatic tears in middle-aged patients with no or mild osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(10):2412–2419. doi: 10.1177/0363546519857589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamberg P, Gillquist J. Knee function after arthroscopic meniscectomy. A prospective study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(2):172–175. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorlund JB, Englund M, Christensen R, Nissen N, Pihl K, Jørgensen U, et al. Patient reported outcomes in patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic or degenerative meniscal tears: comparative prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017:j356. 10.1136/bmj.j356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(4):393–401. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G, Hållander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):358–364. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, De Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1675–1684. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1301408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, Giffin JR, Willits KR, Wong CJ, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1097–1107. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0708333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gauffin H, Sonesson S, Meunier A, Magnusson H, Kvist J. Knee arthroscopic surgery in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a 3-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(9):2077–2084. doi: 10.1177/0363546517701431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):81–88. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa013259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van de Graaf VA, Noorduyn JCA, Willigenburg NW, Butter IK, de Gast A, Mol BW, et al. Effect of early surgery vs physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: the ESCAPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1328–1337. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK, Choi JI, Kim MC, Lee KB, et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1565–1570. doi: 10.1177/0363546513488518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abram SGF, Hopewell S, Monk AP, Bayliss LE, Beard DJ, Price AJ. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for meniscal tears of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(11):652–663. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sihvonen R, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Järvinen TL. Mechanical symptoms and arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in patients with degenerative meniscus tear: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):449–455. doi: 10.7326/m15-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]