Abstract

Genes yiaP and yiaR of the yiaKLMNOPQRS cluster of Escherichia coli are required for the metabolism of the endogenously formed l-xylulose, whereas yiaS is required for this metabolism only in araD mutants. Like AraD, YiaS was shown to have l-ribulose-5-phosphate 4-epimerase activity. Similarity of YiaR to several 3-epimerases suggested that this protein could catalyze the conversion of l-xylulose-5-phosphate into l-ribulose-5-phosphate, thus completing the pathway between l-xylulose and the general metabolism.

On the basis of the similarity displayed by some of the gene products of the yiaKLMNOPQRS (yiaK-S) gene cluster (accession no. U00039) Sofia et al. (14) have proposed that this cluster could be involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates, although the precise substrate has not been determined. More recently, analyses in silico of the corresponding protein sequences by Reizer et al. (11) have permitted the comparison with other known proteins and the suggestion of putative biochemical functions for some of them.

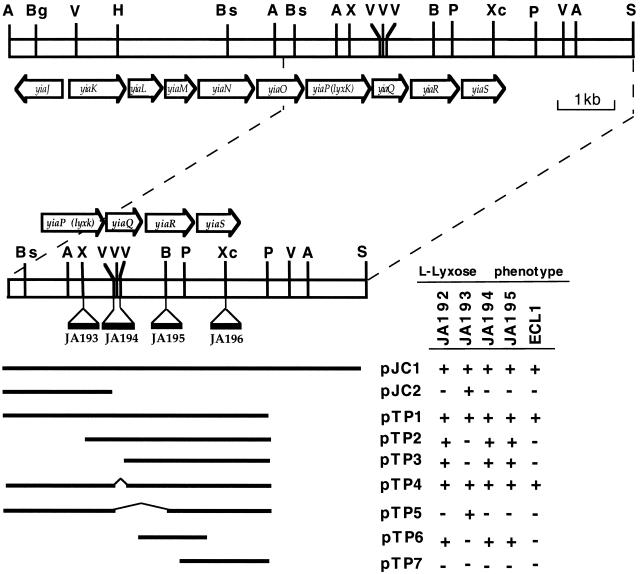

In another context, the characterization of the metabolic pathway allowing the utilization of l-lyxose by mutants of Escherichia coli has shown the presence of a gene encoding a new highly specific l-xylulose kinase (12). l-Xylulose was formed in these mutants by the action of l-rhamnose isomerase on l-lyxose. The restriction map of the region encompassing this gene has permitted its identification as the gene yiaP of the yiaK-S operon. To specify if some other genes among the nine belonging to the yiaK-S operon (Fig. 1) were involved in l-lyxose metabolism, complementation analysis of l-lyxose-negative strains with plasmids containing different fragments of this gene cluster was performed.

FIG. 1.

Genetic map of the region encompassing the yiaK-S operon and complementation analysis of different yiaK-S mutants. The open bar represents the genomic DNA of strain JA134 and the arrows represent the extension and direction of the transcribed yiaK-S genes. Insertions of the CAT cassette are indicated by black bars below the map and are labeled by the name of the mutant strain carrying them. Thick lines correspond to the different inserts of the plasmids used in the complementation experiments whose results are shown in the contiguous table. Thin lines show the deleted fragment in the corresponding plasmid. A, AgeI; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; Bs, BstXI; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI; V, EcoRV; X, XhoI; Xc, XcmI.

l-Lyxose phenotypic complementation of yiaQ, yiaR, and yiaS mutants.

Several mutants unable to utilize l-lyxose were derived from strain JA134 (12) by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis (10), growth on rich medium (3), and selection by replica plating on minimal medium (3) with l-lyxose or glucose. The presence of l-xylulose kinase activity, measured as described previously (12), in some of the mutants indicated that their negative phenotype was due to impairment of a gene function other than l-xylulose kinase. Mutations in the l-rhamnose permease or isomerase required for l-lyxose metabolism (2, 12) were ruled out by analyzing the ketose excretion (7) when grown on l-rhamnose. After this screening, strain JA192 was selected for further analysis.

Previous experiments had shown that l-lyxose utilization did not require genes of the yiaK-S system other than those included in plasmid pJC1 (12). Partial fragments of the insert present in pJC1 were cloned in pBR322 vector, and the derivative plasmids (Fig. 1) were used in complementation analysis of strain JA192. The mutation yielding the l-lyxose-negative phenotype was located in the yiaR gene, since it was complemented by every plasmid except pJC2, pJTP5, or pJTP7 (Fig. 1). To study whether the yiaQ and yiaS gene products are involved in l-lyxose metabolism and to confirm the yiaR participation, chromosomal null mutations in each of these genes were obtained by insertional mutation of the CAT19 cassette (8) and subsequent transference, first to strain JC7623 (15) and then to our genetic background according to the method of Winans et al. (16). When the knockout constructs of yiaP, yiaQ, and yiaR were transferred to the JA134 background (strains JA193, 194, and JA195, respectively), the cells became l-lyxose negative (Fig. 1). The knockout construct of yiaS (strain JA196) did not affect the l-lyxose phenotype.

Complementation of strain JA195 (yiaR::cat) by plasmids carrying the fragment in which the insertion was located confirmed the participation of yiaR in l-lyxose metabolism. Complementation of strain JA194 (yiaQ::cat) by plasmids carrying only yiaR indicated that chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) insertion in yiaQ exerted polarity effects on yiaR and that the yiaQ gene was not necessary for l-lyxose utilization. Furthermore, growth of wild-type strain ECL1 (9) on l-lyxose when transformed with plasmid pTP4 lacking yiaQ again showed that this gene product was not required for l-lyxose metabolism.

yiaR and yiaS gene product analysis.

Computational analysis of the gene product encoded by yiaS yielded 76% identity over 231 amino acids with the l-ribulose-5-phosphate 4-epimerase of Escherichia coli (product of araD gene), which catalyzes an early step in l-arabinose utilization and 74% identity over 203 amino acids with that of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Thus, the yiaS gene product is assigned to the AraD-FucA family.

Plasmids carrying yiaS (Fig. 1) allowed the strain MC4100 (5), reported to be an araD mutant, to utilize l-arabinose, indicating that the yiaS gene complemented araD function and that its product utilized l-ribulose-5-phosphate as a substrate. In addition, Northern blot experiments indicated that l-lyxose was able to induce the ara operon transcription in strain JA134 (not shown). For these experiments, total RNA was obtained from cultures of strain JA134 in casein acid hydrolysate in the absence or in the presence of l-lyxose. An araD gene fragment obtained by PCR with primers P1 (GGCGCTAACTGACGGCAG) and P2 (TAGAAGATCTCAAACGCC) was used as a probe.

The induction of the ara system by l-lyxose and the high similarity displayed by YiaS and AraD suggest that AraD could complement the YiaS function in strain JA196. To determine whether AraD complemented YiaS function, the araD mutation of strain MC4100 was transferred into the genetic background of strain JA196 (yiaS::cat) by the following strategy. (i) A Tn10 marker was transduced from strain CAG12095 (13) into strain MC4100, and tetracycline-resistant transductants that retained the inability to utilize l-arabinose were selected. (ii) One of these transductants (strain JA197) was subsequently used to transduce the two linked markers into strain JA196. A double mutant (strain JA198) was isolated and transformed with plasmids containing yiaS or araD and tested for its ability to utilize both l-lyxose and l-arabinose. None of the transformants analyzed displayed impairment in either of these metabolisms, showing that the 4-epimerase function could be supplied by either of the two YiaS and AraD proteins.

To test if l-lyxose itself or an intermediate metabolite was the inducer of the arabinose system, a Tn5 insertion mutant in the rhaA gene (encoding rhamnose isomerase) was obtained from strain JA134 (strain JA199) by using phage λ 467 (b221 cIts857 rex::Tn5 Oam29 Pam80) (4). This mutant was selected by its inability to utilize l-lyxose and the inability to excrete l-rhamnulose when grown in the presence of l-rhamnose. The precise location of the insertion in rhaA was assessed by cloning and sequencing the chromosomal region close to the Tn5 by using an internal sequence of the transposon as a primer. Induction of the ara operon by l-lyxose in strain JA199 indicated that this compound was directly activating the arabinose operon expression.

To confirm the l-ribulose-5-phosphate 4-epimerase catalytic activity encoded by the yiaS gene, the experimental procedure described by Deupree and Wood (6) was set up. To this end, araB (encoding l-ribulose kinase), araD, and yiaS genes of E. coli were cloned into plasmid pUC19. Overexpression was determined for araB and araD by enzyme activity assays in extracts of strain ECL1 transformed with the corresponding plasmid grown on casein acid hydrolysate. The d-xylulose-5-phosphate formed when l-ribulose was added to a reaction mixture containing extracts of cells overexpressing araB and yiaS yielded an oxidation of NADH of 190 to 210 nmol/min/mg. No significant consumption of NADH was detected when araB or yiaS gene products were lacking. As a positive control, we have run in parallel a reaction with overexpressed araD instead of yiaS.

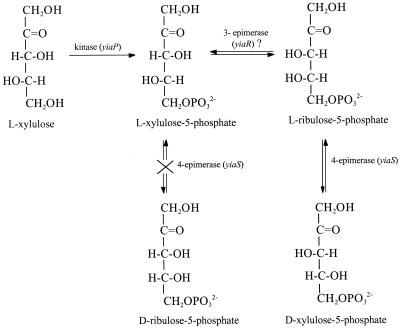

To test whether the yiaS gene product could recognize l-xylulose-5-phosphate as a substrate, another experiment was conducted coupling this gene product with commercial d-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase, which should yield d-xylulose-5-phosphate (Fig. 2). All attempts were unsuccessful, proving that the yiaS gene product did not convert l-xylulose-5-phosphate into d-ribulose-5-phosphate.

FIG. 2.

Proposed pathway for the conversion of l-xylulose into d-xylulose-5-phosphate in strain JA134.

Advanced Blast T2 search (Bork Group at EMBL) of the YiaR sequence indicated a high similarity to several unknown proteins, all of them classified as putative isomerases. Further analysis by PSI-BLAST revealed a slightly lower similarity to d-tagatose-3-epimerase of Thermotoga maritima or Pseudomonas cichorii. Thus, the 3-epimerase activity required for l-lyxose metabolism was tentatively assigned to the yiaR gene.

In the metabolic system under study here, a 3-epimerase activity could convert the l-xylulose-5-phosphate generated by l-xylulose kinase into the l-ribulose-5-phosphate substrate of YiaS (Fig. 2). However, all attempts to obtain experimental evidence of the 3-epimerase activity have been unsuccessful so far. This included the purification of YiaR through its fusion to the protein glutathione S-transferase and separation of the fused protein by affinity chromatography with glutathione to assay the enzymatic activity. The studies performed on YiaR did not rule out its possible role as a 3-epimerase and suggested either a low stability of YiaR or the lack of a key cofactor required for activity and/or stability.

These metabolic conversions are further supported by the fact that l-lyxose metabolism has been shown to require the correct functioning of the pentose phosphate pathway (12) and by the previous description of an identical pathway for the metabolism of l-lyxose in Klebsiella aerogenes (1).

The yiaK-S operon is involved in the metabolism of endogenous l-xylulose.

Although the constitutive expression of the yiaK-S gene cluster allowed strain JA134 to metabolize l-xylulose generated endogenously from l-lyxose by the action of l-rhamnose isomerase, this strain was unable to efficiently utilize this ketose as a sole source of carbon and energy. Furthermore, the same behavior was observed with wild-type strain ECL1 transformed with plasmid pJC1 carrying the genes required for l-xylulose metabolism. These results suggested the inability of these cells to uptake external l-xylulose. Given the structural similarity between l-lyxose, known to be transported by l-rhamnose permease (2), and l-xylulose, competition of this ketose with l-rhamnose for l-rhamnose permease was studied. The results indicate that l-rhamnose permease does not recognize l-xylulose, in contrast to the effect observed with l-lyxose, which produced a strong inhibition of the l-rhamnose transport (data not shown). Inefficient l-xylulose transport suggests that l-xylulose has to be generated endogenously from l-lyxose or in the processing of a hitherto unknown carbohydrate.

It is likely that the yiaK-S cluster evolved for the metabolism of carbohydrate(s) other than l-lyxose, since not all the genes in the operon are involved in the metabolism of this pentose. In order to establish the function of the yiaK-S operon, it is instructive to consider that of the nine gene products of the yia operon, only three, the kinase previously reported (12) and YiaR and YiaS studied in this work, catalyzed the steps required to convert l-xylulose into a d-xylulose-5-phosphate which enters the pentose phosphate pathway. The remaining yia operon genes must be responsible for the generation of this intermediate from an internal or external precursor. Although we demonstrated that l-lyxose is an inducer of the ara operon, it is unlikely that this operon could be induced by the unknown physiological substrate. Therefore, YiaS would not be complemented by AraD and would result in an essential function for its metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant PB97-0920 from the Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior e Investigación Científica, Madrid, Spain, and partially by the help of the “Comissionat per Universitats i Recerca de la Generalitat de Catalunya.” E.I. is the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Generalitat de Catalunya.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson R L, Wood W A. Pathway of xylose and L-lyxose degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badia J, Giménez R, Baldomá L, Barnes E, Fessner W-D, Aguilar J. l-Lyxose metabolism employs the l-rhamnose pathway in mutant cells of Escherichia coli adapted to grow on l-lyxose. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5144–5150. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.5144-5150.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boronat A, Aguilar J. Rhamnose-induced propanediol oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli: purification, properties, and comparison with the fucose-induced enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:320–326. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.320-326.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruijn F J, Lupski J R. The use of transposon Tn5 mutagenesis in the rapid generation of correlated physical and genetic maps of DNA segments cloned into multicopy plasmids. Gene. 1984;27:131–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadaban M J. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deupree J, Wood W A. L-ribulose-5-phosphate 4-epimerase from Aerobacter aerogenes. Methods Enzymol. 1966;IX:412–419. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dische Z, Borenfreund E. A new spectrophotometric method for the detection and determination of keto sugars and trioses. J Biol Chem. 1951;192:583–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuqua W C. An improved chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette for site-directed marker replacement mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1992;12:223–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin E C C. Glycerol dissimilation and its regulation in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:535–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reizer J, Reizer A, Saier M H., Jr Is the ribulose monophosphate pathway widely distributed in bacteria? Microbiology. 1997;143:2519–2520. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez J C, Gimenez R, Schneider A, Fessner W-D, Baldomà L, Aguilar J, Badia J. Activation of a cryptic gene encoding a kinase for L-xylulose opens a new pathway for the utilization of L-lyxose by Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29665–29669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofia H J, Burland V, Daniels D L, Plunkett G, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome. V. DNA sequence of the region from 76.0 to 81.5 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wackernagel W. Genetic transformation in E. coli: the inhibitory role of the recBC DNAse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;51:306–311. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winans S C, Elledge S J, Krueger J H, Walker G C. Site-directed insertion and deletion mutagenesis with cloned fragments in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1219–1221. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1219-1221.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]