Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound assisted collagen peptide of chicken cartilage reduced the drip loss.

-

•

A smaller degree of water migration at −18 °C by the combined treatment.

-

•

The texture of ultrasound assisted treatment were significantly improved.

-

•

Ultrasound assisted treatment had no significance on the color of chicken breast.

Keywords: Collagen peptide, Chicken cartilage, Storage quality, Ultrasound, Chicken breast meat

Abstract

This study investigated the effect of ultrasound assisted chicken cartilage collagen peptide (CP) treatment on the storage quality of chicken breast meat. There were five meat groups at 4 °C for 60 min as follows: untreatment (Control), immersing in deionized water (DW), ultrasound treatment in DW (UDW), immersing in CP (0.15 g/100 mL) solution and immersing in ultrasound combined with CP (UCP). The results showed that the drip and cooking loss of meat decreased significantly in UCP at 4 and −18 °C with the extension of storage time. A large amount of non-flowing water transformed into free water in the 4 °C for 5 d, and the smallest degree of water migration was observed at −18 °C in UCP. The texture parameters of UCP group were significantly improved, especially for decreased hardness and increased elasticity. Furthermore, there had no significant effect on the color of chicken breast.

1. Introduction

Chicken breast meat is rich in protein and has low fat content and tight muscle fiber, which is easy to be absorbed and utilized by human body [1]. However, chicken breast meat is easy to lose water during storage and transportation, and the edible quality of meat will decline during further processing, especially for fitness lovers [2]. Nychas et al. reported that the different packaging methods was employed on the quality of fresh reindeer meat stored at 4 °C, more emphasis on food safety and microbial spoilage [3]. Interestingly, there are many studies on the quality of aquatic products under storage and transportation conditions [4]. The edible quality of livestock and poultry meat needs to be further studied under different storage and transportation conditions.

To alleviate or retard protein denaturation in muscle food, cryoprotectants have been widely used. Cryoprotectants are employed to decrease the denaturation and/or aggregation of myofibrillar protein during low temperature storage, thereby maintaining functional characteristics, such as solubility, emulsifying capacity, water and oil holding capacity and gel-forming ability of proteins [5]. Protein hydrolysates from various sources were also used as a cryoprotectant in frozen food products [6]. Collagen hydrolysates, which are prepared from meat processing by-products, have scavenging activity toward oxidation radicals, and the ability to conjugate with myofibrillar proteins to improve solubility [7]. Zhu et al. found that sea bass collagen peptide (SBCP1) has good water holding capacity [8]. Moreover, the tetrapeptide isolated from Amur sturgeon skin gelatin could decrease the loss of intra myofibrillar water and prevent the denaturation of actomyosin induced by repeated freezethawing [9]. Gelatin from shark skin hydrolysate was used as the cryoprotectant to replace conventional sugars [10]. Furthermore, the cryoprotective effect of collagen hydrolysate was explained by their ability to increase the bound water amount, leading to structural stabilization of proteins and increase hydration of protein molecules [11]. Ultrasound is a green and energy-saving processing technology. A large number of studies have found that ultrasound could assist reagents to marinate meat in order to improve the quality of meat [12].

In recent years, broiler breeding volume and total output value of chicken in China have ranked among the top in the world [13]. Therefore, a large number of by-products of chicken slaughtering and processing have been produced. Chicken cartilage is rich in collagen, with a collagen yield of 42 % [14]. Therefore, it is suitable as a raw material for producing collagen peptide. In this study, the cold fresh chicken breast meat was taken as the research object. Based on the excellent properties of ultrasound assisted collagen peptide treatment, its effects on the changes of water retention, texture and myofibril structure of chicken breast meat during storage was studied.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Material

Chicken cartilage was purchased from Shanghai Guye Food Co., ltd., and washed with distilled water. After low-temperature ventilation and drying, it was sub packed and stored in − 20 °C freezer for standby. Tyson cold fresh chicken breast was purchased from a supermarket in Zhongling street, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province.

2.2. Preparation method of collagen peptide solution from chicken cartilage

The extraction method of collagen peptide from chicken cartilage was performed by our previous method [14]. Chicken cartilages were weighed ∼5 g (wet weight) after the degreasing and impurity removal. Alkaline protease (4000 U/g) was added into the mixture of chicken cartilages. The ultrasound assisted extraction for the collagen peptide from chicken cartilages was applied as the following steps. The material liquid ratio was 1:26 (w/v, the solution was deionized water); ultrasonic power was 250 W (working time of 2 s, rest time of 3 s, total ultrasound time of 30 min) and enzyme extraction time was 4 h (The best extraction process was obtained through pre-experiment). The extraction rate of chicken cartilage collagen peptide could reach 48.73 %. UV spectrum analysis showed that the characteristic absorption peak of collagen peptide of chicken cartilage appeared at the wavelength of 200 ∼ 230 nm. The circular dichroism chromatogram showed no positive absorption peak at the wavelength of 220 ∼ 224 nm, and there was no obvious turning point in the positive and negative absorption bands. The molecular weight of 69 % collagen peptide is in the range of 1.35 kDa ≤ MW < 17 kDa, and the molecular weight of 28 % collagen peptide is less than 1.35 kDa. These results indicated that its characteristics were the basic structure of collagen peptide.

2.3. Sample preparation

The fresh chicken breast meats were cleaned with deionized water and cut into small pieces with ∼20 ± 1 g (40 mm × 30 mm × 10 mm). The chicken breast meats were randomly divided into 5 groups. These five groups were carried out as following treatments. The first group was the untreated treatment group, which was wrapped with fresh-keeping film and stored at 4 °C for 60 min, and was recorded as the Control group. The second group was immersed in deionized water at 4 °C for 60 min, which was recorded as the DW group. The third group was treated with ultrasound for 5 min and then immersed in deionized water at 4 °C for 55 min, which was recorded as the UDW group. The forth group was treated in collagen peptide solution from chicken cartilage (0.15 g/100 mL, CCCP) and marinated at 4 °C for 60 min to ensure that the collagen peptides solution was fully reacted with the meat, which was recorded as the CP group. The fifth group was treated with ultrasound for 5 min, then placed in CCCP solution and marinated at 4 °C for 55 min, which was recorded as the UCP group. After treatment, the meat pieces were taken out respectively. Then, the visible water on the surface of the meat pieces were gently wiped with filter paper. At last, the samples were put into sealed bags.

The meat was immersed in a 1000 mL beaker (containing 800 mL ice water), which was used to avoid the overheating effect caused by ultrasound treatment for samples. The diameter of ultrasound probe was 12 mm. The surface of the meat was 15 mm away from the ultrasound probe. According to the optimization results of previous experiments, the ultrasound power of 200 W (ultrasound frequency of 20 kHz, intensity of 15.6 W/cm2) was selected for the working parameters [15]. When the ultrasound treatment reached to half of treatment time, the meat was turned over and continued the ultrasound treatment, so that the ultrasound treatment can effect on the whole meat.

2.4. Storage of chicken breast meat at cold fresh (4 °C) and frozen (-18 °C) environment

The processed meats were place for the following condition: 0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 d at 4 °C and at 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 d −18 °C respectively. The total bacterial reached about 6 (lg(CFU/cm2)) when the Control group was stored for 7 d at 4 °C. The microorganism of the sample was exceeded the standard when the storage time was extended to 9 d, indicating that the chicken breast meat stored for 7 d under this condition can be studied. The quality changes of chicken breast meat were studied within 30 d of storage at −18 °C.

2.5. Determination of drip loss rate

It was determined according to the method of Bedane et al. [16] with slightly modified. The initial mass of meat was record as m1 (g) in section 2.4. The meat was hanged with a metal hook and suspended it in a 100 mL centrifugal tube. The centrifugal tube was sealed the mouth with a fresh-keeping film. In order to reserve enough space to deposit the water exuded from the meat samples, the height of the bottom of the meat in the centrifugal tube shall be kept at a certain distance from the bottom of the tube. The above centrifugal tube was stored at 4 °C for 24 h. The fresh-keeping film was removed. The surface water of meat was gently wiped with filter paper and then the mass of the meat again was recorded (m2, g). The drip loss rate is calculated according to formula (1).

| (1) |

2.6. Determination of cooking loss rate

The cooking loss rate was determined according to the method of Liu and Lanier [17]. After gently wiping the surface moisture of the meat with filter paper, the weight of the meat mass was record as m1 (g). The meats were put into the self-sealing cooking bag. The probe of digital thermometer was inserted into the center of chicken breast meat along the direction of muscle fiber and then placed them in a constant temperature water bath pot at 85 °C. The meats were taken out immediately after the central temperature of the meat at 75 °C, and placed in a beaker filled with ice to cool for room temperature. The surface water of meat was gently wiped with filter paper and then the mass of the meat again was recorded (m2, g). The cooking loss rate is calculated according to formula (2).

| (2) |

2.7. Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR)

According to the method of Han et al. [18], the water distribution of chicken breast was measured by low field NMR with slight modification. The meat sample (∼2 g) was cut along the direction of the internal muscle fibers of chicken breast and placed in a 15 mm glass NMR tube. The proton resonance frequency was set to 22.6 MHz. Before determination, all samples were balanced at 25 °C for 30 min and carried out at 32 °C. The pulse sequence was CPMG, and the transverse relaxation time (T2) was measured. The measurement parameters were set as follows: the diameter of RF coil was 25 mm; the waiting time for repeated sampling was 4000 ms; the number of echoes was 15000; the echo interval was 0.25 MS, and the number of repeated scanning was 16. The resulting attenuation curve was inversed by MultiExp Inv analysis software, and each group was repeated for 3 times. These samples were stored at 4 °C for 7 d.

2.8. Texture profile analysis (TPA)

The method of texture determination was according to the method of Aguirre et al. [19] with slightly modification. The cooked meat was cut along the fiber direction of chicken breast with a ruler and scalpel 20 mm × 20 mm × 10 mm meat pieces in section 2.6. According to the TPA model, the meat pieces under different treatment conditions were analyzed twice. The hardness, elasticity, stickiness and chewiness of meat pieces were measured by physical property analyzer at room temperature. The test parameters were as follows: the probe model was p/50 flat bottom cylindrical; test rate was 120 mm/min; shape variable was 50 % and trigger force was 5 g. Each group of samples was measured in parallel for 7 times, and the average value was received.

2.9. Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

According to the method of Li et al. [20], the pressurization condition of scanning electron microscope (SEM) was set at 10.0 kV. The meat was cut into pieces along the direction of muscle fibers 5 mm × 5 mm × 3 mm. The slices were fixed with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde solution, and then gradient eluted with ethanol (50 %, 70 %, 80 %, 90 % and 95 %, v/v respectively). After the above step, the samples were vacuum freeze-dried and sprayed with gold coating. The microstructure was observed by SEM with magnification of 500.

2.10. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of tissue

After cooking in section 2.5, the meats were cut into squares of 5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde, which was convenient to prepare paraffin sections. After dewaxing, HE staining was carried out, dehydrated and sealed. After being examined by an upright optical microscope, clear color images were collected for tissue structure analysis [2].

2.11. Statistical analysis

The above experiments were repeated for 3 times, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. SPSS 24.0 software was used for one-way ANOVA. Tukey test was used for the data difference between groups. P < 0.05 indicates that the difference is significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Drip loss rate

The water retention of meat directly affects the economic value and quality characteristics of meats. Additionally, the water retention is also closely related to the color, texture and tenderness of meat [21]. In meat processing, excessive water loss could lead to low yield of meat products and bad taste. It was found that ultrasound treatment promoted the release of salt soluble protein. Soluble protein was wrapped on the surface of droplets to form small-size emulsion droplets, so that more water was captured by muscle fibers and reduce the liquid loss during suspension of meaty by ultrasound treatment [22].

As shown in Table 1, when the meat was stored at 4 °C for 3 d, the drip loss rate was increased significantly (P < 0.05), and then decreased slightly. This may be due to the increase of the degradation degree of myofibrillar protein, resulting in the destruction of the network structure of myofibrillar protein, and the water was broken through the barrier and migrates from the inside to the outside of muscle fiber [23]. On the other hand, when the meats were stored at −18 °C for 5 d, the dripping loss rate of chicken breast meat reached the maximum in this study. These results might be due to the influence of sharp ice crystals formed during freezing on the structure of muscle fibers, which caused certain damage and reduced its water holding capacity [24]. The drip loss rate of chicken breast meat stored at − 18 °C for 5 d was higher than that of all meats stored at 4 °C. The phenomenon could be due to the formation of a large number of ice crystals from −18 °C for 5 d, resulting in more cell membrane rupture and increased drip loss of samples [25]. Under the two storage temperatures, the centrifugal loss rate of each group showed an increasing trend with the extension of storage time. The reason was due to the reduction of static charge and repulsive force carried by protein in chicken breast during storage. Therefore, the distance between protein molecules was shortened, so as to discharge the water distributed therein outward and reduce the water retention [26]. The drip loss rate of CP and UCP group was significantly lower than that of Control, DW and UDW. The chicken cartilage collagen peptide solution had a certain viscosity, which could cause the adhesion between meat fibers. On the other hand, glycine, proline and hydroxyproline, which are rich in collagen peptides, may also have non reductive cross-linking reaction with proteins in muscle. These factors resulted in less water leakage in chicken during centrifugation, and more bound water or less flowing water was retained in muscle fibers [27]. UCP treatment can accelerate the penetration of collagen peptide from chicken cartilage into chicken breast meat, leading to reduce drip loss.

Table 1.

Effect of ultrasound-assisted chicken cartilage collagen peptide treatment on drip loss and cooking loss of chicken breast meat during storage at 4 °C and −18 °C.

| Storage (d) | Control | DW | UDW | CP | UCP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drip loss (%) | |||||

| 0 (4/-18 °C) | 3.32 ± 0.42C | 3.30 ± 0.41C | 3.28 ± 0.46C | 3.1 ± 0.24B | 3.08 ± 0.23C |

| 1 (4 °C) | 3.88 ± 0.36aC | 3.81 ± 0.37aC | 3.71 ± 0.35aC | 3.28 ± 0.33bB | 3.24 ± 0.31bC |

| 3 (4 °C) | 5.64 ± 0.45aAB | 5.61 ± 0.48aAB | 5.56 ± 0.47aAB | 4.69 ± 0.33bA | 4.57 ± 0.30bA |

| 5 (4 °C) | 4.87 ± 0.21aB | 4.76 ± 0.23aB | 4.62 ± 0.22aB | 4.21 ± 0.20bA | 4.01 ± 0.17bB |

| 7 (4 °C) | 5.01 ± 0.39aB | 5.02 ± 0.40aB | 4.98 ± 0.37aB | 4.39 ± 0.29bA | 4.30 ± 0.26bAB |

| 5 (-18 °C) | 6.98 ± 0.82aA | 6.96 ± 0.75aA | 6.87 ± 0.77aA | 4.96 ± 0.64bA | 5.03 ± 0.66bA |

| 10(-18 °C) | 6.74 ± 0.83aA | 6.81 ± 0.85aA | 6.7 ± 0.81aA | 4.46 ± 0.77bA | 4.45 ± 0.81bAB |

| 15 (-18 °C) | 6.62 ± 0.83aA | 6.66 ± 0.81aA | 6.48 ± 0.79aA | 4.51 ± 0.71bA | 4.33 ± 0.80bAB |

| 20 (-18 °C) | 6.42 ± 0.77aA | 6.41 ± 0.72aA | 6.22 ± 0.88aA | 4.03 ± 0.81bAB | 4.01 ± 0.91bB |

| Cooking loss (%) | |||||

| 0 (4/-18 °C) | 22.41 ± 0.82aC | 21.90 ± 1.36aC | 20.60 ± 0.71abE | 18.41 ± 1.67bC | 18.34 ± 1.04bD |

| 1 (4 °C) | 22.62 ± 0.63aC | 22.05 ± 0.55aC | 20.55 ± 0.88abE | 18.53 ± 0.64bC | 18.41 ± 1.07bD |

| 3 (4 °C) | 28.78 ± 0.54aAB | 28.43 ± 0.67aAB | 24.68 ± 0.47bC | 22.12 ± 0.33cB | 21.98 ± 0.55cBC |

| 5 (4 °C) | 26.63 ± 1.01aB | 26.21 ± 0.35aB | 23.86 ± 0.63bCD | 20.96 ± 0.53cBC | 20.56 ± 0.48cC |

| 7 (4 °C) | 24.12 ± 0.53aBC | 23.94 ± 0.67aBC | 22.75 ± 0.37aD | 19.45 ± 0.29bBC | 19.27 ± 0.66bAB |

| 5 (-18 °C) | 30.92 ± 0.78aA | 30.76 ± 0.45aA | 29.93 ± 0.66aA | 26.04 ± 0.86bA | 25.76 ± 0.44bA |

| 10(-18 °C) | 29.78 ± 0.99aA | 29.56 ± 0.78aA | 28.22 ± 0.52aAB | 25.23 ± 0.77bA | 24.32 ± 0.51bAB |

| 15 (-18 °C) | 28.23 ± 1.02aAB | 28.62 ± 0.77aAB | 27.98 ± 0.33aB | 23.91 ± 0.52bB | 22.65 ± 0.38bB |

| 20 (-18 °C) | 28.32 ± 1.04aAB | 28.78 ± 0.56aAB | 28.12 ± 0.56aAB | 24.53 ± 0.75bAB | 23.97 ± 0.39bB |

Different lowercase letters in the same line indicate that there are significant differences among the groups at the same storage time (P < 0.05). Different capital letters in the same column indicate significant differences in the same group and different storage time (P < 0.05).

3.2. Cooking loss rate

It can be seen from Table 1 that the overall trend of cooking loss rate of chicken breast stored at 4 °C and −18 °C increased first and then decreased with the extension of storage time. With the extension of storage time, the permeated collagen peptide solution can form a water barrier film on the surface or inside of the meat, so that more water can be retained in the muscle. There is no significant difference in cooking loss rate between Control and DW under the same storage condition. Compared with Control and DW, the cooking loss rate of chicken in CP and UCP decreased significantly (P < 0.05), indicating that the above treatments can effectively reduce the cooking loss of chicken breast. Control and DW had higher cooking loss because the heating process induced the irreversible denaturation of muscle protein in these two groups [28]. The lowest cooking loss rate in UCP might be that the collagen peptide solution fully entered the chicken breast meat tissue and reacted with the muscle protein after ultrasound treatment, so that more water entered the muscle fiber structure [29]. At the same time, the permeated collagen peptide solution from chicken cartilage formed a film on the surface or inside of the chicken breast meat after cooking. Hence, more water was retained in the myofibril, so as to reduce the cooking loss and improve the water retention of chicken breast meat.

3.3. Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF NMR)

LF NMR is used to analyze the water distribution and state in meat by measuring the relaxation characteristics of hydrogen nuclei in magnetic field [30]. According to the difference of transverse relaxation time T2, the changes of water in different states in chicken breast meat are determined in Table 2. The greater T2 is, the higher the degree of free water in meat is. The water distribution and fluidity of chicken breast meat in the five treatment groups during storage at 4 °C and −18 °C were evaluated by transverse relaxation time T2 and peak area (P). There were three characteristic peaks in the transverse relaxation time T2 of chicken breast meat in the five groups at different storage temperatures, corresponding to bound water (T21, 0 ∼ 10 ms), non-flowing water (T22, 10 ∼ 100 ms) and free water (T23, 100 ∼ 1000 ms). It can be seen that P22 of chicken breast meat in the five groups decreased significantly and P23 increased significantly with the extension of storage time under the conditions of storage at 4 °C for 0, 5 d and −18 °C for 20 d. The difficult flowing water in chicken breast meat in each group transformed into free water, and the water locking capacity gradually weakened. Therefore, the water retention became worse with the extension of storage time.

Table 2.

Effect of ultrasound-assisted chicken cartilage collagen peptide treatment on water distribution of chicken breast meat stored at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d, and −18 °C for 20 d.

| Control | DW | UDW | CP | UCP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C −0 d T21 (ms) | 0.735 ± 0.032C | 0.730 ± 0.035C | 0.736 ± 0.027C | 0.738 ± 0.026C | 0.734 ± 0.034C |

| T22 (ms) | 18.559 ± 0.31aC | 18.541 ± 0.35aC | 15.124 ± 0.57bC | 9.567 ± 0.64cC | 10.569 ± 0.816cC |

| T23 (ms) | 233.27 ± 1.26cA | 347.35 ± 1.67aA | 350.13 ± 1.89aA | 352.24 ± 1.33aA | 303.36 ± 1.20bA |

| P21 | 620.29 ± 3.23bA | 585.05 ± 2.64cA | 573.11 ± 3.02cA | 642.43 ± 2.49bA | 695.83 ± 2.57aA |

| P22 | 10134.75 ± 2.30eA | 10268.54 ± 1.98dA | 10452.63 ± 1.37cA | 12392.63 ± 1.71bA | 12702.81 ± 1.86aA |

| P23 | 103.31 ± 1.79aC | 100.69 ± 1.43aC | 96.75 ± 0.68bC | 36.96 ± 0.57cA | 35.16 ± 0.56cC |

| 4 °C −5 d | |||||

| T21 (ms) | 1.27 ± 0.19aB | 1.31 ± 0.56aB | 1.02 ± 0.44bB | 0.88 ± 0.11cB | 0.87 ± 0.10cB |

| T22 (ms) | 28.23 ± 0.62aB | 28.19 ± 0.34aB | 18.579 ± 0.59bB | 14.154 ± 0.43cB | 13.21 ± 0.14cB |

| T23 (ms) | 167.25 ± 1.12cB | 154.22 ± 1.66dB | 176.36 ± 1.93bB | 225.48 ± 1.34aAB | 224.17 ± 1.35aB |

| P21 | 421.18 ± 1.41dB | 435.25 ± 1.27eB | 483.46 ± 1.32cB | 607.58 ± 1.20bB | 630.36 ± 1.26aB |

| P22 | 9265.74 ± 1.62dB | 9175.33 ± 1.52eB | 9734.62 ± 2.24cB | 11242.91 ± 2.08bB | 11798.31 ± 2.41aB |

| P23 | 510.23 ± 1.89aB | 512.48 ± 1.91bB | 462.71 ± 1.03cB | 223.43 ± 1.76dB | 178.56 ± 1.85eB |

| −18 °C −20 d | |||||

| T21 (ms) | 2.01 ± 0.036aA | 2.02 ± 0.035aA | 1.76 ± 0.052bA | 1.32 ± 0.057cA | 1.30 ± 0.060cA |

| T22 (ms) | 49.68 ± 1.02aA | 49.37 ± 1.03aA | 28.53 ± 1.02bA | 19.14 ± 0.98cA | 18.67 ± 0.97cA |

| T23 (ms) | 114.826 ± 1.01dC | 130.72 ± 1.00cC | 131.36 ± 1.37cC | 172.74 ± 1.45bC | 200.37 ± 1.85aC |

| P21 | 391.67 ± 1.22dC | 392.13 ± 1.23dC | 433.84 ± 1.94cC | 571.38 ± 0.87aC | 507.13 ± 1.02bC |

| P22 | 7684.32 ± 1.96dC | 7679.54 ± 2.0dC | 8326.86 ± 1.32cC | 9768.75 ± 1.27bC | 9820.67 ± 1.68aC |

| P23 | 978.53 ± 1.95aA | 975.26 ± 1.97aA | 870.42 ± 1.08bA | 633.78 ± 1.79cA | 543.26 ± 1.43dA |

Different lowercase letters in the same line indicate that there are significant differences among the groups at the same storage time (P < 0.05). Different capital letters in the same column indicate significant differences in the same index and different storage time (P < 0.05).

Under the storage condition at −18 °C for 20 d, the T23 (free water) of chicken breast meat was lower than that at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d. The reason could be due to the dual effect of low temperature and sharp ice crystal extrusion on the structure of chicken breast meat during repeated freezing and thawing at −18 °C [31]. This could result in difficult flowing water flow. As a result, the water composition and structure changed, and the free water content increased sharply. Comparing different groups under the same storage temperature and time, it was seen that P23 in UDW was significantly less than that in DW, and P22 in UCP was significantly greater than that in CP. This might be because UDW marinatation enhanced the ability of meat to capture water, so as to improve the water retention of meat [32]. Furthermore, ultrasound treatment promoted muscle fiber swelling and provided more space for the penetration of collagen peptides from chicken cartilage, and the soluble protein exudation caused by ultrasound retained more water in the meat fiber structure in UCP [1].

3.4. Texture profile analysis (TPA)

It can be seen from Table 3 that the hardness and elasticity of chicken breast meat were negatively correlated with storage time when each group was stored at 4 °C for 0, 5 d and −18 °C for 20 d respectively. The above results were due to the fact that the meat quality of chicken breast gradually became loose and the integrity of muscle tissue was damaged with the extension of storage time [33]. For different groups under the same storage condition, the overall order of hardness was Control, followed by DW, UDW, CP, and UCP, and the overall order of elasticity was UCP, followed by CP, UDW, DW, and Control. These results showed that the chicken breast meat in UCP showed the characteristics of low hardness and high elasticity, and the synergistic treatment of ultrasound and chicken cartilage collagen peptide could achieve a significant improvement effect. The stickiness of chicken breast meat in different groups under the same storage condition decreased from Control to UCP. The decrease of chewability of chicken breast meat indicated that it was easier to chew, which may be due to the decrease of hardness of chicken breast meat [34]. This phenomenon enlarged the gap between muscle filaments and muscle tissue. The chewability and stickiness decreased gradually from Control to UCP in different groups with the same storage conditions, indicating that the edible performance of UCP group was better.

Table 3.

Effect of ultrasound-assisted chicken cartilage collagen peptide treatment on texture profile of chicken breast meat stored at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d, and −18 °C for 20 d.

| Control | DW | UDW | CP | UCP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C −0 d | |||||

| Hardness (N) | 21.18 ± 0.77aA | 21.09 ± 0.65aA | 21.01 ± 0.59aA | 13.34 ± 1.10bA | 14.56 ± 0.64bA |

| elasticity (mm) | 3.66 ± 0.43A | 3.65 ± 0.31A | 3.72 ± 0.44A | 3.81 ± 0.62A | 3.89 ± 0.41A |

| stickiness (N) | 12.44 ± 0.76aA | 12.34 ± 0.71aA | 12.89 ± 0.69aA | 5.42 ± 0.53bA | 5.31 ± 0.54bA |

| chewiness (mJ) | 45.60 ± 0.74aA | 43.10 ± 0.57aA | 30.11 ± 0.77bA | 24.30 ± 0.56cA | 23.14 ± 0.75cA |

| 4 °C −5 d | |||||

| Hardness (N) | 15.62 ± 0.67aB | 15.99 ± 0.76aB | 14.37 ± 0.55bB | 6.03 ± 1.01cB | 5.79 ± 0.67cB |

| elasticity (mm) | 2.98 ± 0.55AB | 2.79 ± 0.54AB | 3.03 ± 0.62AB | 2.61 ± 0.64B | 2.75 ± 0.39B |

| stickiness (N) | 8.91 ± 0.77aB | 7.91 ± 0.58aB | 8.84 ± 0.53aB | 3.12 ± 0.64bB | 2.51 ± 0.43bC |

| chewiness (mJ) | 28.17 ± 1.21aB | 29.12 ± 1.01aB | 21.09 ± 0.92aB | 11.21 ± 0.76bB | 11.18 ± 0.81bB |

| −18 °C −20 d | |||||

| Hardness (N) | 12.21 ± 0.88aC | 12.32 ± 0.91aC | 12.01 ± 0.78aC | 5.42 ± 0.45bB | 5.13 ± 0.49bB |

| elasticity (mm) | 2.53 ± 0.33B | 2.51 ± 0.24B | 2.68 ± 0.31B | 2.41 ± 0.36B | 2.56 ± 0.44B |

| stickiness (N) | 8.03 ± 0.58aB | 8.01 ± 0.61aB | 9.26 ± 0.78aB | 3.52 ± 0.33B | 3.61 ± 0.39bB |

| chewiness (mJ) | 25.30 ± 1.02aC | 25.20 ± 1.04aC | 18.61 ± 0.98bC | 11.92 ± 0.77cB | 11.83 ± 0.74cB |

Different lowercase letters in the same line indicate that there are significant differences among the groups at the same storage time (P < 0.05). Different capital letters in the same column indicate significant differences in the same index and different storage time (P < 0.05).

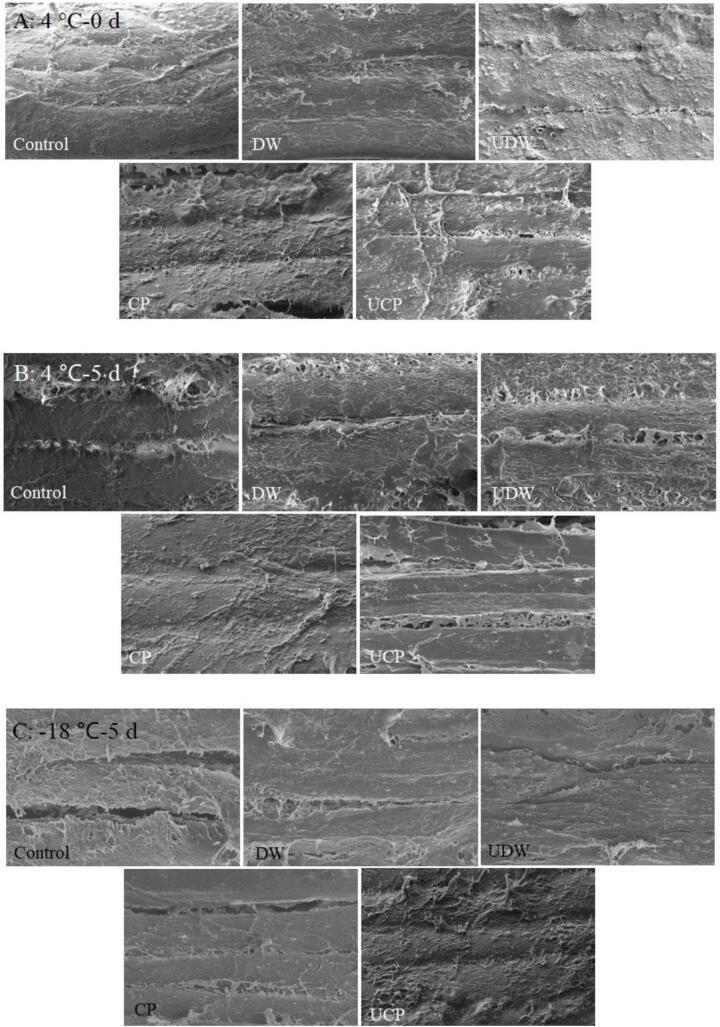

3.5. SEm

The microstructure of meat is closely related to water retention and quality [35]. It can be seen from Fig. 1A to 1C that chicken cartilage collagen peptide can effectively prevent the strong degradation of myofibrils in chicken breast under the conditions of storage at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d and −18 °C for 20 d, so as to maintain the integrity of myofibril structure in chicken breast and have a positive impact on the quality and water retention of chicken breast [36]. UCP treatment properly maintained the integrity of chicken breast myofibril structure. Furthermore, it accelerated the effective penetration of chicken cartilage collagen peptide into muscle fiber tissue, and effectively protected the integrity of myofibril during the storage. Therefore, ultrasound treatment could cooperate with chicken cartilage collagen peptide to improve the quality of stored chicken breast. When stored at 4 °C for 0 d, the myofibrils of chicken breast meat in Control and DW were arranged orderly and stable intact, and there was basically no fault and gap between fibers. It was obvious that myofibrils were broken more or less, and the contents were dissolved and there were small voids in groups UDW, CP and UCP. When stored at 4 °C for 5 d, the destruction of myofibrils in groups Control, DW and UDW was more serious than that in CP and UCP, with obvious massive damage structure and filamentous hanging phenomenon. When stored at −18 °C for 20 d, the structures of UDW, CP and UCP were more intact, which might be due to the lower storage temperature and the protection of myofibrillar protein structure by collagen peptide treatment [37].

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron microscopic images of chicken breast meat in different treatments stored at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d, and −18 °C for 20 d (×500).

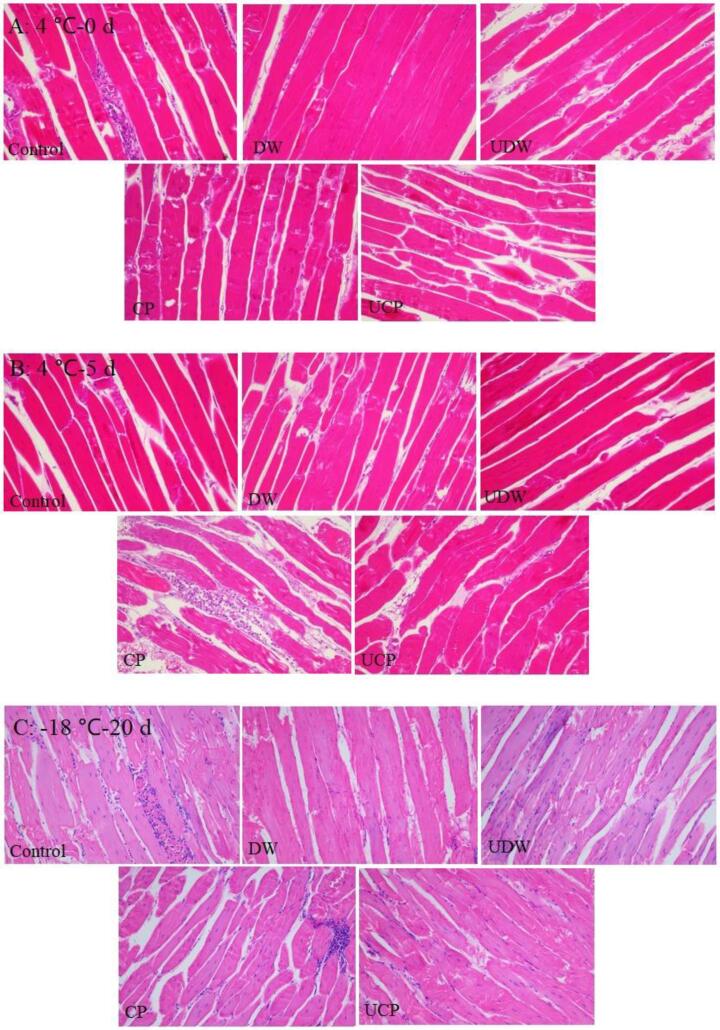

3.6. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

It can be seen from Fig. 2A-C that although the muscle fiber bundles in UDW had small intervals during storage for 0 d at 4 °C, they were generally tight and complete, and DW was accompanied by slight damage, which might be related to immersion in deionized water for a short time. Compared with DW, CP had obvious tissue fluid exudation and slight structural corrosion, which could be related to chicken cartilage collagen peptide marinatation solution. The marinatation process caused meat muscle reaction and damaged the muscle fibers and connective tissue [38]. In UDW and UCP stored at 4 °C for 5 d and −18 °C for 20 d, the increase of fiber gap and the obvious exudation of contents were observed the destruction of muscle fibers in varying degrees. After ultrasound treatment, the chicken cartilage collagen peptide solution was easier to penetrate into the tissue gap, resulting in more solution entering the tissue and more water retained in the chicken breast [39].

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained images of chicken breast meat in different treatments stored at 4 °C for 0 and 5 d, and −18 °C for 20 d.

4. Conclusions

The effects of ultrasound assisted collagen peptide treatment of chicken cartilage on the storage quality of chicken breast meat were studied. The results showed that the water in chicken breast meat gradually migrated from non-flowing water to free water with the extension of storage time under two storage temperatures, and the overall fluidity of water increased. Among them, the non-flowing water in 4 °C group was transformed into free water, and the degree of water migration in −18 °C group was less. The texture indexes and internal tissue structure characteristics of chicken breast meat in different treatment groups were further measured. Compared with other groups, the texture indexes of ultrasound treatment group were significantly improved (hardness decreased and elasticity increased). Ultrasound assisted chicken cartilage collagen peptide treatment significantly improved the quality of chicken breast meat. Combined with SEM observation and HE staining, it was found that the tissue structure of chicken breast meat in each treatment group corresponded to the results of water retention and texture one by one. The results of this study could provide reference for improving meat quality and sports fitness meat research and development in the later stage.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ye Zou: Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Liang Li: Writing – review & editing. Jing Yang: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Biao Yang: Investigation, Project administration. Jingjing Ma: Resources, Investigation. Daoying Wang: Project administration. Weimin Xu: Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the China agriculture research system (CARS-41), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901612) and Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(21)2016). We thank the staff of the Central Laboratory at Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences for their help in scanning electron microscope.

Contributor Information

Daoying Wang, Email: daoyingwang@yahoo.comxuw.

Weimin Xu, Email: xuweimin@jaas.ac.cn.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Cao C., Xiao Z., Tong H., Tao X., Gu D., Wu Y., Xu Z., Ge C. Effect of ultrasound-assisted enzyme treatment on the quality of chicken breast meat. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021;125:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi H.B., Zhang X.X., Chen X., Fang R., Zou Y., Wang D.Y., Xu W.M. How ultrasound combined with potassium alginate marination tenderizes old chicken breast meat: Possible mechanisms from tissue to protein. Food Chem. 2020;328 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nychas G.J.E., Skandamis P.N., Tassou C.C., Koutsoumanis K.P. Meat spoilage during distribution. Meat Sci. 2008;78:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Y.W., You X.P., Sun W.Q., Xiong G.Q., Shi L., Qiao Y., Wu W.J., Li X., Wang J., Ding A.Z., Wang L. Insight into acute heat stress on meat qualities of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) during short-time transportation. Aquaculture. 2021;543 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu H.Y., Sun C.B., Liu N. Effects of different cryoprotectants on microemulsion freeze-drying. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2019;54:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkelunas P.J., Li-Chan E.C.Y. Production and assessment of Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) hydrolysates as cryoprotectants for frozen fish mince. Food Chem. 2018;239:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dang Q.F., Liu H., Yan J.Q., Liu C.S., Liu Y., Li J., Li J.J. Characterization of collagen from haddock skin and wound healing properties of its hydrolysates. Biomed. Mater. 2015;10 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/10/1/015022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J., Liu L., Zhang M., Wei Z., Zhang Y., Ma Y., Chi J. Comparing the Functional Properties of Sea Bass Collagen Peptides (SBCP) with Different Molecular Weights. Modern Food Sci. Technol. 2014;30:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 9.M. Nikoo, J. Mac Regenstein, M. R. Ghomi, S. Benjakul, N. Yang, X. M. Xu, Study of the combined effects of a gelatin-derived cryoprotective peptide and a non-peptide antioxidant in a fish mince model system. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 60(2015), 358-364.

- 10.Limpisophon K., Iguchi H., Tanaka M., Suzuki T., Okazaki E., Saito T., Takahashi K., Osako K. Cryoprotective effect of gelatin hydrolysate from shark skin on denaturation of frozen surimi compared with that from bovine skin. Fisheries Sci. 2015;81:383–392. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damodaran S., Wang S.Y. Ice crystal growth inhibition by peptides from fish gelatin hydrolysate. Food Hydrocolloid. 2017;70:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilphy A.R., Temimi A.B., Rubaiy H.H.M., Anand U., Delgado-Pando G., Lakhssassi N. Ultrasound applications in poultry meat processing: a systematic review. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:1386–1396. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piran F.S., Lacerda D.P., Camanho A.S.M., Silva C.A. Internal benchmarking to assess the cost efficiency of a broiler production system combining data envelopment analysis and throughput accounting. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021;238 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou T., Wu Y., Lu F., Yang B., Ma J., Yang J., Zou Y., Wang D., Xu W. Physicochemical and functional properties of collagen peptides derived from ultrasonic-assisted alkaline protease hydrolysis of chicken claws. Meat Res. 2021;35:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou Y., Lu F., Yang B., Ma J., Yang J., Li C., Wang X., Wang D., Xu W. Effect of ultrasound assisted konjac glucomannan treatment on properties of chicken plasma protein gelation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedane T.F., Altin O., Erol B., Marra F., Erdogdu F. Thawing of frozen food products in a staggered through-field electrode radio frequency system: A case study for frozen chicken breast meat with effects on drip loss and texture. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2018;50:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu W.J., Lanier T.C. Rapid (microwave) heating rate effects on texture, fat/water holding, and microstructure of cooked comminuted meat batters. Food Res. Int. 2016;81:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Z.Y., Zhang J.L., Zheng J.Y., Li X.J., Shao J.H. The study of protein conformation and hydration characteristics of meat batters at various phase transition temperatures combined with Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2019;280:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguirre M.E., Owens C.M., Miller R.K., Alvarado C.Z. Descriptive sensory and instrumental texture profile analysis of woody breast in marinated chicken. Poultry Sci. 2018;97(4):1456–1461. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F.F., Du X., Wang B., Pan N., Xia X.F., Bao Y.H. Inhibiting effect of ice structuring protein on the decreased gelling properties of protein from quick-frozen pork patty subjected to frozen storage. Food Chem. 2021;353 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.C. Botinestean, D. F. Keenan, J. P. Kerry, & R. M. Hamill, The effect of thermal treatments including sous-vide, blast freezing and their combinations on beef tenderness of M. semitendinosus steaks targeted at elderly consumers. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 74(2016), 154-159.

- 22.Liu H.T., Zhang H., Liu Q., Chen Q., Kong B.H. Solubilization and stable dispersion of myofibrillar proteins in water through the destruction and inhibition of the assembly of filaments using high-intensity ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straadt I.K., Rasmussen M., Andersen H.J., Bertram H.C. Aging-induced changes in microstructure and water distribution in fresh and cooked pork in relation to water-holding capacity and cooking loss – a combined confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and low-field nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation study. Meat Sci. 2007;75(4):687–695. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dang D.V.S., Bastarrachea L.J., Martini S., Matarneh S.K. Crystallization behavior and quality of frozen meat. Foods. 2021;10(11):2707. doi: 10.3390/foods10112707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei R., Wang P., Han M.Y., Chen T.H., Xu X.L., Zhou G.H. Effect of freezing on electrical properties and quality of thawed chicken breast meat. Asian-Austral. J. Anim. 2017;30(4):569–575. doi: 10.5713/ajas.16.0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji H.F., Hou X.Z., Zhang L.W., Wang X.F., Li S.S., Ma H.J., Chen F.S. Effect of ice-temperature storage on some properties of salt-soluble proteins and gel from chicken breast muscles. Cyta-J. Food. 2021;19(1):521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazorra-Manzano M.A., Torres-Llanez M.J., Gonzalez-Cordova A.F., Vallejo-Cordoba B. A capillary electrophoresis method for the determination of hydroxyproline as a collagen content index in meat products. Food Anal. Method. 2012;5(3):464–470. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markov D.I., Zubov E.O., Nikolaeva O.P., Kurganov B.I., Levitsky D.I. Thermal denaturation and aggregation of myosin subfragment 1 isoforms with different essential light chains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010;11(11):4194–4226. doi: 10.3390/ijms11114194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarlok J., Smiechowski K., Kowalska M. Hygienic properties of leather finished with formulations containing collagen hydrolysate obtained by acid hydrolysis. J. Soc. Leath. Tech. Ch. 2015;99(6):297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun H.X., Huang F., Ding Z.J., Zhang C.J., Zhang L., Zhang H. Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of the effects of heating temperature and time on braised beef. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2017;52(5):1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coombs C.E.O., Holman B.W.B., Friend M.A., Hopkins D.L. Long-term red meat preservation using chilled and frozen storage combinations: A review. Meat Sci. 2017;125:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou Y., Yang H., Zhang M.H., Zhang X.X., Xu W.M., Wang D.Y. The influence of ultrasound and adenosine 5'-monophosphate marination on tenderness and structure of myofibrillar proteins of beef. Asian-Austral. J. Anim. 2019;32(10):1611–1620. doi: 10.5713/ajas.18.0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z.Y., Ma W.R., Xian Z.J., Liu Q.S., Hui A.L., Zhang W.C. The impact of quick-freezing methods on the quality, moisture distribution and microstructure of prepared ground pork during storage duration. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agar B., Genccelep H., Saricaoglu F.T., Turhan S. Effect of sugar beet fiber concentrations on rheological properties of meat emulsions and their correlation with texture profile analysis. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016;100:118–131. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L., Huang H.B., Wang P., Xing T., Xu X.L. Water-spraying forced ventilation during holding improves the water holding capacity, impedance, and microstructure of breast meat from summer-transported broiler chickens. Poultry Sci. 2020;99(3):1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J.C., Zhang M., Cao P., Adhikari B. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles combined radio frequency pasteurization on the protein structure and water state of chicken thigh meat. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2020;134 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walayat N., Xiong Z.Y., Xiong H.G., Moreno H.M., Nawaz A., Niaz N., Hu C., Taj M.I., Mushtaq B.S., Khalifa I. The effect of egg white protein and beta-cyclodextrin mixture on structural and functional properties of silver carp myofibrillar proteins during frozen storage. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;135 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin J.X., Zhang Y.Y., Li Y.W., Sun P.Z., Ren X., Li D.M. Improving the texture properties and protein thermal stability of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) by L-lysine marination. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2022;102(9):3916–3924. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sergeev A., Shilkina N., Tarasov V., Mettu S., Krasulya O., Bogush V., Yushina E. The effect of ultrasound treatment on the interaction of brine with pork meat proteins. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.