Abstract

ς38 (or ςS, the rpoS gene product) is a sigma subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli and directs transcription from a number of stationary-phase promoters as well as osmotically inducible promoters. In this study, we analyzed the function of the carboxy-terminal 16-amino-acid region of ς38 (residues 315 to 330), which is well conserved among the rpoS gene products of enteric bacterial species. Truncation of this region was shown to result in the loss of sigma activity in vivo using promoter-lacZ fusion constructs, but the mutant ς38 retained the binding activity in vivo to the core enzyme. The in vitro transcription analysis revealed that the transcription activity of ς38 holoenzyme under high potassium glutamate concentrations was significantly decreased by the truncation of the carboxy-terminal tail element.

Sigma factor is a subunit of RNA polymerase in eubacteria and donates to catalytic core RNA polymerase the ability to recognize promoter sequence and to initiate specific transcription (8). In Escherichia coli, seven sigma subunit species are known to exist, each sigma controlling a specific subset of genes for corresponding cellular functions. Six of the seven sigma factors belong to the ς70 family; ςN does not (14).

The principal sigma factor, ς70, is the most abundant and essential sigma, responsible for transcription of most housekeeping genes. The RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing ς70 (Eς70, where E represents the core enzyme) recognizes so-called consensus promoters, which consist of bipartite sequences TATAAT and TTGACA located around the −10 and the −35 base pairs, respectively, upstream from the transcription initiation sites (8). E. coli cells have another primary sigma factor, ς38 (or ςS, the rpoS gene product), that is structurally closely related to ς70. ς38 positively regulates a number of stationary-phase specific promoters and osmotically inducible promoters (9). The RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing ς38 (Eς38) recognizes many consensus promoters as well as Eς70 does, although the recognition sequence preference is somehow different between the two holoenzymes (23, 25). Both enzymes recognize similar −10 consensus sequences, but a set of promoters are recognized only by Eς38, suggesting that Eς38 recognizes as-yet-unidentified unique sequence elements (4, 28).

Four conserved regions, from the amino-terminal region 1 through the carboxy-terminal region 4, have been proposed to exist in ς70 family proteins, and each region can be further divided into subregions (14). Functions for some subregions have been suggested or demonstrated by genetic and biochemical analyses. In the case of ς70, region 1.1 inhibits binding of the sigma factor to DNA in the absence of the core polymerase (3). Region 2.1 includes a binding site with the core polymerase (13), and regions 2.4 and 4.2 are involved in the recognition of promoter DNA sequences (19).

In this study, we focused on the function of the extreme carboxy-terminal 16-amino-acid region of ς38. This region is located immediately downstream of region 4.2. Although contact sites with some transcription factors were mapped in the corresponding region of ς70 (11, 15), no general function has been assigned for this portion of sigma factors. Nevertheless, this region is highly conserved among the rpoS gene products from enteric bacterial species. Here we show an essential function for this region of ς38.

Structure of the carboxy-terminal region of ς38.

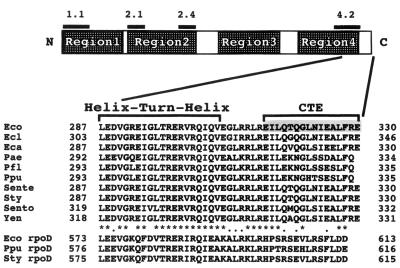

Region 4, the carboxy-terminal region among the four conserved sequences of the ς70 family proteins, is further divided into two parts, regions 4.1 and 4.2. Region 4.2 contains a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif, and in fact, the second helix has been shown to interact directly with the promoter −35 hexamer sequence (14). The downstream flanking sequence of region 4, which we named here CTE for carboxy-terminal tail element, is unique for each ς subunit, and a striking similarity was found among CTEs of the rpoS gene products (ς38-CTE; Fig. 1) from various bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the carboxy-terminal region of RpoS. The thick bar represents a linear diagram of ς38. N and C indicate the amino and carboxy termini of ς38, respectively. Conserved regions 1 to 4 are indicated, and subregions 1.1, 2.1, 2.4, and 4.2, for which functions were assigned, are indicated above the thick bar. Amino acid sequences of the carboxy-terminal region are aligned below the thick bar. GenBank database searches were performed by the BLAST program through homepages of National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Amino acid sequences were aligned using the Clustal V program with a fixed gap penalty of 10 and a floating gap penalty of 10. Asterisks represent identical residues, and periods represent residues having similar characteristics. The abbreviations denote the following bacterial species: Eco, E. coli; Ecl, Enterobacter cloacae; Eca, Erwinia carotovora; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Pfl, Pseudomonas fluorescens; Ppu, Pseudomonas putida; Sente, Salmonella enterica; Sty, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; Sento, Serratia entomophila; and Yen, Yersinia enterocolitica. A bracket indicates a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif at region 4.2. The shaded area indicates the carboxy-terminal 16-amino-acid region (CTE) that was truncated in this study.

CTE is required for promoter activation in vivo.

To analyze the function of ς38-CTE in vivo, the rpoS gene was mutagenized so as to express a mutant ς38 lacking CTE. Using oligonucleotide I (Table 1) and pKTF1 (a 2.3-kb KpnI fragment containing the rpoS gene in the same direction as lacZ of vector plasmids pTZ19R [24]), the 315th codon of the rpoS open reading frame (ORF) was mutagenized to TAA with the MUTA-GENE In Vitro Mutagenesis Kit (Bio-Rad), and the resultant plasmid was named pKTF314. Both the wild-type and the mutant rpoS genes were expressed under the control of the inducible araBAD promoter. For this purpose, 1.8-kb NcoI-PvuII fragments containing the rpoS ORF were purified from pKTF1 and pKTF314 and were cloned in the NcoI-SmaI site of pBAD22A (7) to make pBF1 and pBF314, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| I | 5′-GTTTGCGCTAAATCCTG-3′ |

| II | 5′-TGGTGGATCCGCCAGAC-3′ |

| III | 5′-CCCCAAGCTTCTAGCGCAAACGGCGCAG-3′ |

| IV | 5′-TTTTAAGCTTTCCCTATA-3′ |

| Va | 5′-TTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′ |

| VI | 5′-TTCAATCGTCTGGCGGATCCACCAGGTTGCGTA-3′ |

| VII | 5′-CTGGTGGATCCGCCAGACGATTGAA-3′ |

| VIII | 5′-GGATCCTTATTGAGCTCAGAAAAAACCAGCC-3′ |

Oligonucleotide V is a T7 promoter primer.

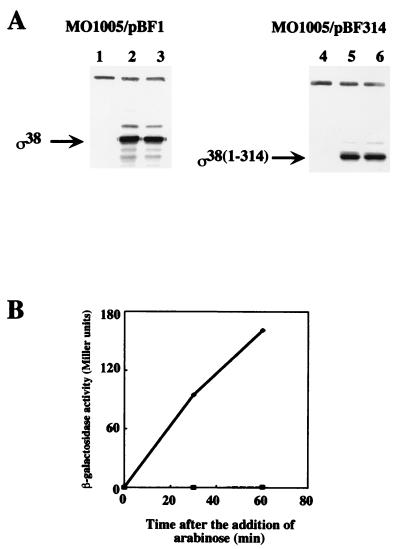

Each of these constructs was introduced into a null rpoS mutant strain, MO1005EL, which was constructed based on NM522 (16) by P1 transduction of rpoS::Tn10 (22) and λkatE::lacZ (22). The corresponding gene products were detected after the arabinose induction (Fig. 2A), confirming that the system was functioning appropriately as expected. As a reporter system to detect the sigma activity of the rpoS gene products, the katE promoter that is transcribed dependent on rpoS (22) was fused with lacZ and positioned in the E. coli chromosome as a single copy by using a λ phage-mediated system (21). While the β-galactosidase activity was increased after induction of the wild-type rpoS gene, no increase of the activity was detected after induction of the mutant sigma factor [ς38(1-314)] (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we concluded that the katE promoter transcription requires ς38-CTE.

FIG. 2.

Effect of truncation of ς38-CTE on the transcription activity of the katE promoter. MO1005EL cells harboring pBF1 or pBF314 were grown with shaking in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), and ampicillin (50 μl/ml) at 37°C. RpoS proteins were induced by the addition of arabinose at an optical density at 660 nm of 0.3. (A) The expression of ς38 or ς38(1-314) was monitored by Western analysis with antiserum against ς38 (25). Samples were taken at 0 min (lanes 1 and 4), 30 min (lanes 2 and 5), and 60 min (lanes 3 and 6) after the addition of arabinose. The upper signals are an unrelated band detected by the serum that are irrespective of the rpoS expression. (B) The katE transcription activity was assayed using a lacZ fusion construct. The β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (5) except that cell density was measured at 660 nm. The solid line and dashed line correspond to results obtained with MO1005EL/pBF1 and MO1005EL/pBF314, respectively. These results are averages of duplicate measurements.

To examine whether the CTE function is generally required for the ς38 activity, expression of lacZ fusion constructs to other ς38-dependent promoters, fic (26) and bolA (12), were analyzed using the same mutant ς38 as in the case of katE. Both of the tested promoters were activated by ς38 but not by ς38(1-314) (data not shown). The carboxy terminus regions of sigma factors were shown to interact with some ς-contact transcription factors to activate transcription initiation (11, 15). However, these interactions are not likely to explain the in vivo functional defects of ς38(1-314) because the activity was uniformly lost for all tested promoters which do not require additional transcription factors for function. In 1993, Zambrano and coworkers isolated an rpoS mutant that has a growth advantage at the stationary growth phase (the GASP mutant) (29). In this mutant, the CTE region of rpoS was replaced by a 46-bp duplication, resulting in a shift of the reading frame. The prediction that this mutation weakened the ς38 activity in vivo is consistent with our present observation.

CTE is not required for holoenzyme formation in vivo.

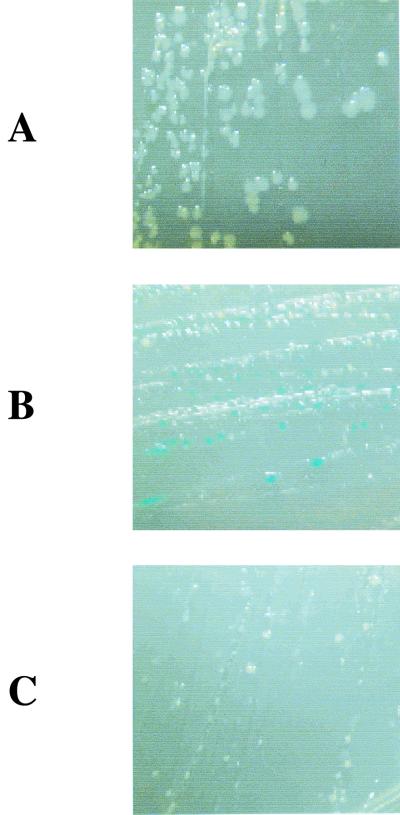

To examine whether the loss of sigma activity by the CTE truncation is due to impaired holoenzyme formation, either ς38 or ς38(1-314) was overexpressed in the null rpoS mutant strain, MO1001FL, which was constructed based on KT1008 (22) by P1 transduction of rpoS::kan (1) and λfic::lacZ (unpublished construct; K. Yamamoto and R. Utsumi, personal communication). In the case of ς70, a glutathione S-transferase fused a ς70 derivative lacking the first 72 amino acids, which has a severe defect in open complex formation and is toxic to the cell when overexpressed, since core enzyme is sequestered in nonproductive holoenzyme complex (27). Mutations that cause defects in core enzyme binding relieved the toxicity (18). As shown in Fig. 3B, overproduction of ς38 severely retarded cell growth, probably because ς38 competed the core enzyme with ς70. Since the overproduction of ς38(1-314) caused similar growth retardation (Fig. 3C), we concluded that the core binding was not impaired for ς38(1-314). However, the β-galactosidase activity was lost by the CTE truncation (Fig. 3B and C, compare colony colors), indicating that the defects were involved in later steps after the binding with the core enzyme.

FIG. 3.

ς38-CTE is not required for holoenzyme formation. pTZ19R (vector) (A), pKTF1 (ς38 overexpression plasmid) (B), and pKTF314 [ς38(1-314) overexpression plasmid] (C) were introduced into rpoS null mutant MO1001FL. Effects on growth and fic-lacZ expression resulted from ς38, and ς38(1-314) overexpression was monitored using a Luria-Bertani plate containing 40 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)/ml and 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

ς38-CTE is required for transcription activity in vitro under high-salt conditions.

As an attempt to understand the reason why CTE is required for the in vivo function of ς38, we performed in vitro transcription experiments using purified ς38 proteins. Using oligonucleotide II (Table 1) and pKTF18 (a 2.3-kb KpnI fragment containing the rpoS gene in the same direction as lacZ of vector plasmid pTZ18R), a BamHI site was introduced into the mid-portion of the rpoS ORF without changing the amino acid sequence of the gene product, while a BamHI site in the plasmid polylinker of the resulting plasmid pKTF18B was deleted by partial digestion with BamHI and fill-in-ligation reactions. From pKTFB thus constructed, a 1.5-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment containing the 3′ half of the rpoS ORF was purified and cloned in pTZ19R to yield pRPO. To change the 315th codon of the rpoS ORF to a nonsense TAG codon, an inverse PCR was performed using oligonucleotides III and IV as primers and pRPO as a template. The PCR-amplified product was digested with HindIII and self-ligated to make pRPO314.

To introduce a BamHI site into the rpoS ORF at the same position as pKTFB, PCRs were performed to amplify the 5′ and 3′ parts of the rpoS ORF, using pETF (25) and two sets of primers, oligonucleotides V and VI and oligonucleotides VII and VIII, respectively. Both PCR products were purified and mixed to perform the mega-primer PCR (10). The resultant fused products were digested with NdeI and SacI and inserted into pET21b to make pETS. A 541-bp BamHI-HindIII region containing the rpoS 3′ part was replaced by a 491-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of pRPO314 to yield pETS314.

ς38 and ς38(1-314) were overexpressed in BL21 (DE3) pLysS (Novagen) by using pETF and pETS314, respectively, and the protein purification was carried out basically as previously described (25) except for the protein renaturation process. After the inclusion body was solubilized, renaturation was performed by dialysis against TGED (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]–5% glycerol–0.1 mM EDTA–0.1 mM dithiothreitol) buffer. The solubilized proteins were further purified by POROS HQ column chromatography (6).

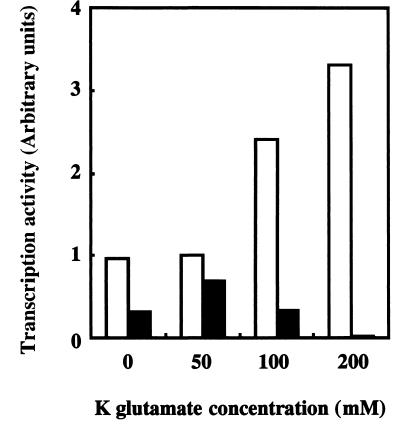

To examine the activity of ς38 and ς38(1-314), in vitro transcription experiments were performed using the fic promoter as a template. Since it has been shown by using various promoters as templates that optimum salt concentrations for Eς38 are rather high compared with those for Eς70 (2), we carried out in vitro transcription reactions under various potassium glutamate concentrations. As shown in Fig. 4, while transcription activity of Eς38 was increased concomitantly with the increase in potassium glutamate concentration at least up to 200 mM, the optimum potassium glutamate concentration for Eς38(1-314) was 50 mM, and the transcription activity of Eς38(1-314) was severely inhibited at 200 mM potassium glutamate. Therefore, ς38-CTE is important for the transcription activation by high concentrations of potassium glutamate. Since intracellular K+ concentrations are kept in a range of 0.1 to 0.5 M (20) and since glutamate is a natural counterion for K+, these results are in good agreement with the observations shown in Fig. 2 and 3. Thus, ς38-CTE might specifically donate salt resistance to this stationary sigma factor. However, underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be analyzed.

FIG. 4.

ς38-CTE is required for effective transcription activity at high ionic strength in vitro. The core enzyme and either ς38 or ς38(1-314) were mixed at the ratio of 1:4 and incubated for 30 min at 37°C to reconstitute holoenzymes. Single-round in vitro transcription assays were performed essentially as previously described (17). Transcription reactions were carried out under various ionic strengths (0, 50, 100, and 200 mM of K glutamate) with 100 nM reconstituted holoenzyme and 3 nM template DNA containing the fic promoter, i.e., the BamHI-EcoRI fragment (776 bp) of pFL1 (26). The DNA template produced in vitro transcripts 242 nucleotides in length. Transcription activity at 50 mM K glutamate by Eς38 was set at 1. Open bars represent transcription activity of Eς38, and closed bars represent that of Eς38(1-314). These results are averages of duplicate experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Utsumi and K. Yamamoto for providing unpublished material (λfic::lacZ). We also thank K. Hayashi for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, Biodesign Research Program of RIKEN to K.T. and H.T., and CREST (Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology) of the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST) to A.I. and K.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohannon D E, Connel N, Keener J, Tormo A, Espinosa-Urgel M, Zambrano M M, Kolter R. Stationary-phase-inducible “Gearbox” promoters: differential effects of katF mutations and role of ς70. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4482–4492. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4482-4492.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding Q, Kusano S, Villarejo M, Ishihama A. Promoter selectivity control of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by ionic strength: differential recognition of osmoregulated promoters by EςD and EςS holoenzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:649–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dombroski A J, Walter W A, Record M T, Jr, Siegele D A, Gross C A. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription factor ς70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell. 1992;70:501–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90174-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinosa-Urgel M, Chamizo C, Tormo A. A consensus structure for ςS-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:657–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farewell A, Kvint K, Nyström T. Negative regulation by RpoS: a case of sigma factor competition. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1039–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto-Seki A, Shirokane M, Masuda S, Tanaka K, Takahashi H. Specificity crosstalk among group 1 and group 2 sigma factors in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942: in vitro specificity and a phylogenetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:473–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzman L, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmann J D, Chamberlin M J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:839–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1497–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki R K. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7366. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landini P, Brown J A, Volkert M R, Busby S J W. Ada protein-RNA polymerase ς subunit interaction and α subunit-promoter DNA interaction are necessary at different steps in transcription initiation at the Escherichia coli ada and aidB promoters. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13307–13312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Growth phase-regulated expression of bolA and morphology of stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells are controlled by the novel sigma factor ςS. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4474–4481. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4474-4481.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesley S A, Burgess R R. Characterization of the Escherichia coli transcription factor ς70: localization of a region involved in the interaction with core RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7728–7734. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross C A. The ς70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationship. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonetto M, Rhodius V A, Lamberg K, Kiley P, Busby S J W, Gross C A. Identification of a contact site for different transcription activators in region 4 of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase ς70 subunit. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1353–1365. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mead D A, Skorupa E S, Kemper B. Single stranded DNA SP6 promoter plasmids for engineering mutant RNAs and proteins: synthesis of a ‘stretched’ preproparathyroid hormone. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1103–1118. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.4.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishiyama M, Kobashi N, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Tanokura M. Cloning and characterization in Escherichia coli of the gene encoding the principal sigma factor of an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;172:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharp M M, Chan C L, Lu C Z, Marr M T, Nechaev S, Merritt E W, Severinov K, Roberts J W, Gross C A. The interface of ς with core RNA polymerase is extensive, conserved, and functionally specialized. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3015–3026. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegele D A, Hu J C, Walter W A, Gross C A. Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the ς70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:591–603. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver S. Transport of ionic cations. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1091–1102. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka K, Handel K, Loewen P C, Takahashi H. Identification and analysis of the rpoS-dependent promoter of katE, encoding catalase HPII in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1352:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka K, Kusano S, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Takahashi H. Promoter determinants for Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing ς38 (the rpoS gene product) Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:827–834. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka K, Takahashi H. Cloning, analysis and expression of an rpoS homologue gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Gene. 1994;150:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka K, Takayanagi Y, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Takahashi H. Heterogeneity of the principal ς factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, ς38, is a second principal ς factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utsumi R, Nakayama T, Iwamoto N, Kawamukai M, Tanabe H, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Noda M. Mutational analysis of the fic promoter recognized by RpoS (ς38) in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:1573–1575. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willson C, Dombroski A J. Region 1 of ς70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:60–74. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise A, Brems R, Ramakrishnan V, Villarejo M. Sequences in the −35 region of Escherichia coli rpoS-dependent genes promote transcription by Eς38. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2785–2793. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2785-2793.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zambrano M M, Siegele D A, Almirón M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase. Science. 1993;259:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]