Abstract

The CA1 pyramidal neurons are embedded in an intricate local circuitry that contains a variety of interneurons. The roles these interneurons play in the regulation of the excitatory synaptic plasticity remains largely understudied. Recent experiments showed that recurring cholinergic activation of α7 nACh receptors expressed in oriens-lacunosum-moleculare (OLMα2) interneurons can directly induce LTP in Schaffer collateral (SC)–CA1 synapses. Here, we pair in vitro studies with biophysically based modeling to uncover the underlying mechanisms. According to our model, α7 nAChR activation increases OLM GABAergic activity. This results in the inhibition of the fast-spiking interneurons that provide feedforward inhibition onto CA1 pyramidal neurons. This disinhibition, paired with tightly timed SC stimulation, can induce potentiation at the excitatory synapses of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Our work details the role of cholinergic modulation in disinhibition-induced hippocampal plasticity. It relates the timing of cholinergic pairing found experimentally in previous studies with the timing between disinhibition and hippocampal stimulation necessary to induce potentiation and suggests the dynamics of the involved interneurons plays a crucial role in determining this timing.

Keywords: hippocampus, synaptic plasticity, disinhibition, Schaffer Collateral, nicotinic receptors, GABA neurons

Significance Statement

We use a combination of experiments and mechanistic modeling to uncover the key role for cholinergic neuromodulation of feedforward disinhibitory circuits in regulating hippocampal plasticity. We found that cholinergic activation of α7 nAChR expressed in oriens-lacunosum-moleculare interneurons, when tightly paired with stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals, can cancel feedforward inhibition onto CA1 pyramidal cells, enabling the potentiation of the SC–CA1 synapse. Our work details how cholinergic action on GABAergic interneurons can tightly regulate the excitability and plasticity of the hippocampal network, unraveling the intricate interplay of the hierarchal inhibitory circuitry and cholinergic neuromodulation as a mechanism for hippocampal plasticity.

Introduction

The hippocampal networks are characterized by a variety of locally connected GABAergic interneurons exerting robust control on network excitability. Previous work has detailed the importance of inhibitory inputs in modulating local hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Wigström and Gustafsson, 1985; Meredith et al., 2003; Chevalerye and Piskorowski, 2014; Saudargienė and Graham, 2015). Furthermore, several experimental studies show that disinhibition facilitates the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) at excitatory synapses (Ormond and Woodin, 2009; Yang et al., 2016). However, how the disinhibition controlling hippocampal excitatory synapses is modulated (e.g., by neuromodulators) is not clearly understood, and the precise circuitry and its dynamics underlying this type of plasticity remains an open question.

GABAergic interneurons receive significant cholinergic innervation from the medial septum. They are endowed with various subtypes of nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs) that regulate excitability, plasticity, and cognitive functions (Pitler and Alger, 1992; Behrends and Ten Bruggencate, 1993; Hasselmo et al., 1995; Alkondon et al., 1997; Patil et al., 1998; McQuiston and Madison, 1999; Patil and Hasselmo, 1999; Levin, 2002; Hasselmo, 2006; Parikh et al., 2007; Bell et al., 2011, 2015; Griguoli and Cherubini, 2012; Yakel, 2012; Desikan et al., 2018; Nicholson and Kullmann, 2021). Moreover, alterations of cholinergic action on hippocampal GABAergic interneurons have been implicated in cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Schmid, et al., 2016). These studies, among others, furnish clear evidence that cholinergic inputs exert a powerful role in regulating hippocampal activity. Still, because of the abundance of cholinergic receptors (both muscarinic and nicotinic) and the complexity of the networks in which they are embedded, it is difficult to access the exact mechanisms through which cholinergic action on the hippocampus modulates its microcircuits.

Previous studies showed that activation of α7 nACh receptors expressed in oriens-lacunosum-moleculare (OLMα2) interneurons increases Schaffer collateral (SC)–CA1 transmission and suggest that this happens through disinhibition by reducing the activity of stratum radiatum (s.r.) interneurons that in turn provide feedforward inhibition onto pyramidal (PYR) neurons (Leão et al., 2012). Consistent with these studies, Gu et al. (2020) found that repeated coactivation of α7 nAChR on OLMα2 interneurons and a local SC pathway increased CA1 EPSCs and reduced IPSCs. However, the mechanisms through which the activation of the OLMα2 interneurons regulates the activity of inhibitory interneurons targeting the CA1 pyramidal cell, and how this facilitates the increase of SC-evoked EPSPs of the CA1 pyramidal cells remain elusive.

In the CA1 region, α7 nAChR can be found on both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites of GABAergic synapses (Fabian-Fine, 2001). For this reason, the outcome of α7 nAChR activation and how it modulates OLMα2 interneuron activity is difficult to address. Activation of postsynaptic α7 nAChRs could increase the spiking frequency of OLMα2 interneurons, although, to our knowledge, OLMα2 spiking by nAChRs has not been clearly characterized, while presynaptic α7 nAChRs regulate the release of neurotransmitter by activating calcium-dependent pathways that lead to the fusion of neurotransmitter vesicles with the membrane of the neuron (Desikan et al., 2018).

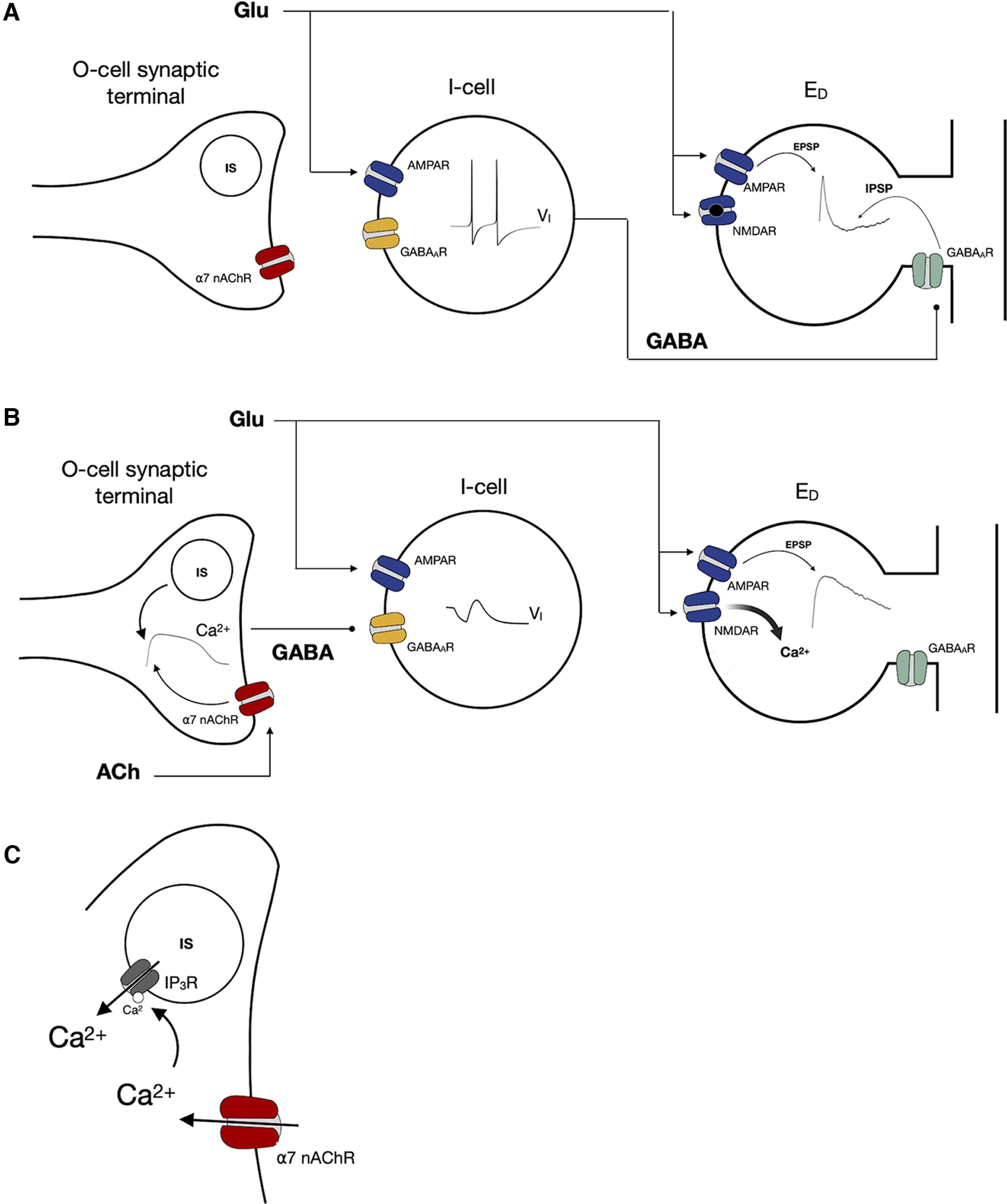

In this work, we use a minimal biophysical circuit model, driven quantitatively by in vitro data, to show how modulation of OLM cells (O-cells) influences the activity of fast-spiking interneurons whose GABAergic inputs are colocalized with the SC glutamatergic synapses onto a CA1 pyramidal cell dendrite, and how this promotes the induction of plasticity at the SC–CA1 synapse. We seek to determine how cholinergic activation of the OLM cells through presynaptic α7 nAChRs can downregulate the GABAergic signaling onto the pyramidal cells, and how recurrent decreased inhibitory inputs can indirectly enhance the plasticity of the excitatory SC–CA1 synapse. We thus constructed a minimal circuit consisting of a single compartment spiking model of an OLM interneuron (O-cell) with α7 nAChRs, a fast-spiking interneuron (I-cell) with AMPA and GABAA receptors, and a pyramidal cell dendritic compartment (ED) with AMPA, NMDA, and GABAA receptors. They are connected as schematically shown in Figure 1.

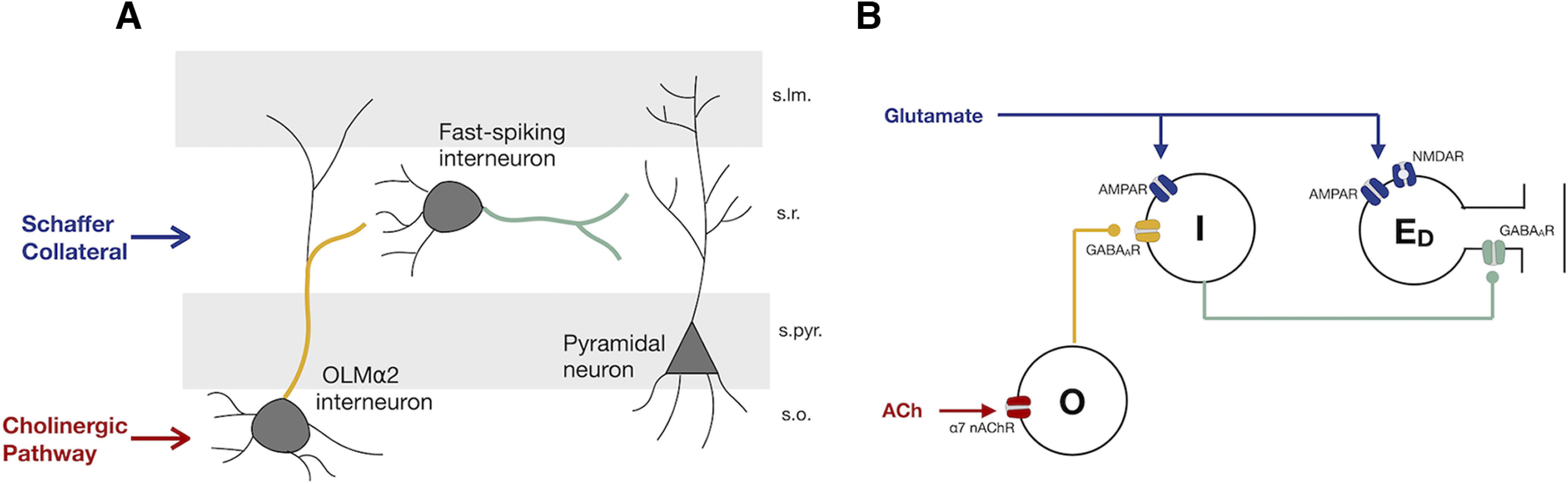

Figure 1.

Disynaptic disinhibition circuit for nAChR-modulated long-term plasticity in the CA1. A, Simplified wiring diagram of an interneuron network that mediates feedforward inhibition in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Activation of the SC pathway leads to the activation of CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites and s.r. interneurons, which provide feedforward inhibition onto the pyramidal cell. Cholinergic activation of OLMα2 interneurons in s.o. leads to the inhibition of the s.r. interneurons, counteracting SC feedforward inhibition (Leão et al., 2012). B, Minimal network to investigate plasticity induced by the pairing of cholinergic and SC activation. Glutamate activates postsynaptic AMPARs and NMDARs at the pyramidal cell ED and postsynaptic AMPARs at I-cells, which in turn provide feedforward inhibition onto ED by activating postsynaptic GABAARs. Cholinergic inputs act on presynaptic α7 nAChRs of O-cells, which results in GABA release of the O-cells that it is going to bind to postsynaptic GABAARs of the I-cell.

Overwhelming evidence suggests that most types of LTP involve calcium influx through NMDARs and subsequent changes in the properties of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (AMPARs), namely changes in their number and phosphorylation state (Collingridge et al., 1983; Barria et al., 1997; Lüscher and Malenka, 2012). To reflect these mechanisms, we use the calcium-based synaptic plasticity model (proposed by Shouval et al., 2002) to model synaptic plasticity of the SC–CA1 excitatory synapse.

In this study, we use a combination of experiments with computational modeling to put together a coherent picture of the multiple mechanisms through which concurrent disinhibition directly induces local SC–CA1 plasticity. More specifically, we show how repeated concurrent disinhibition induces LTP by mediating AMPAR trafficking. Our modeling results also put together all the pieces of the puzzle to lay out how nAChR cholinergic action on OLM interneurons, working through calcium-dependent regulation of GABA neurotransmission, can downregulate the GABAergic signaling onto CA1 pyramidal cells and induce potentiation of the SC–CA1 synapse.

Materials and Methods

Animals and materials

All procedures related to the use of mice followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the NIEHS. ChAT-cre mice [B6;129S6-Chattm2(cre)Lowl/J], Sst-cre mice [Ssttm2.1(cre)Zjh], and floxed α7 nAChR knock-out mice [B6(Cg)-Chrna7tm1.1Ehs/YakelJ] were originally purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and then bred at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). OLMα2-cre mice [Tg(Chrna2cre)OE29Gsat/Mmucd] were originally obtained from Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Centers and then bred at NIEHS. Mice (of either sex) were used for slice culture from day 6 to 8.

Culture media were from Sigma-Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 helper plasmid was obtained from James Wilson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The AAV vector containing floxed ChR2 (catalog #20297, Addgene) and floxed enhanced NpHR (eNpHR; catalog #26966, Addgene) were obtained from Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Gradinaru et al., 2010; Witten et al., 2010). AAV viruses were packaged with serotype 9 helper at the Viral Vector Core facility at the NIEHS.

Brain slice culture and AAV infection

To study the effects of cholinergic coactivation on the plasticity of SC–CA1 synapses (Fig. 2C,E), coronal septal slices (350 μm) from ChAT-cre mice and horizontal hippocampal slices from floxed α7 nAChR mice or OLMα2-cre/floxed α7 nAChR mice (350 μm) were cut with a vibratome (model VT1000S, Leica). Medial septal tissue containing cholinergic neurons was then dissected out and placed next to the hippocampus on a six-well polyester Transwell insert (Corning) and cultured there for ∼2 weeks before being used for experiments, similar to those previously described (Gu and Yakel, 2017). AAVs containing a double-floxed ChR2 construct (5 nl) were microinjected to the septal tissue with a microinjector (Drummond Scientific) on the second day of culture. To study the effects of disinhibition on the plasticity of SC–CA1 synapses (see Fig. 4C), horizontal hippocampal slices from Sst-cre mice were cultured and AAVs containing double-floxed eNpHR construct were microinjected to the hippocampus the next day.

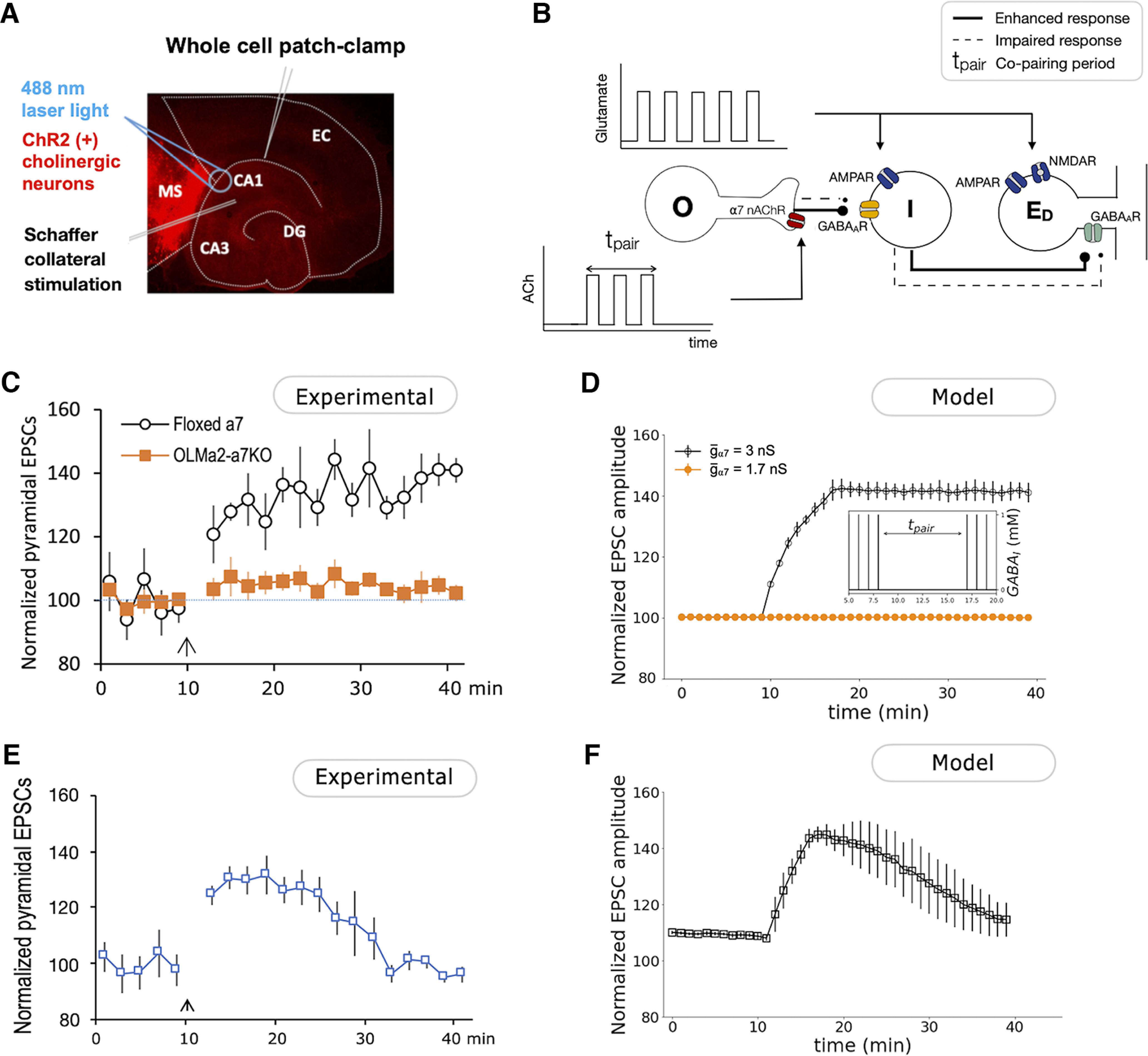

Figure 2.

Cholinergic activation of OLM interneurons potentiates SC-evoked EPSCs. A, Scheme of in vitro induction of cholinergic pairing-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity. EPSCs were recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons. Cholinergic neurons were activated via channelrhodopsin-2 that was specifically expressed in ChAT-positive neurons. The SC pathway was activated by a stimulating electrode. Adapted from the study by Gu et al. (2017). B, Scheme of the minimal network used to study the role of cholinergic inputs in the potentiation of SC-evoked EPSCs. Glutamatergic inputs activate the pyramidal cell ED and the fast-spiking I-cell that projects to it. Square pulses of ACh activate the O-cell during the copairing period. The neural response of O-cell, I-cell, and ED when the system receives one pulse of glutamate paired or not with ACh is shown in Extended Data Figure 2-1. The release of GABA from the O-cells is calculated using the simplified model described by Equation 16. The Extended Data Figure 2-2 shows that the simplified neurotransmitter release model results in a similar synaptic activation function as the detailed model described in the study by Destexhe et al. (1998). Different ACh synaptic profiles are explored in Extended Data Figure 2-3. C, Normalized SC-evoked EPSC responses from CA1 pyramidal neurons showing that the enhancement of EPSCs was impaired in hippocampal slices from mice with selective α7 nAChR knockout in OLMα2 interneurons. Adapted from the study by Gu et al. (2020). D, Numerical simulation of normalized EPSC amplitude when glutamatergic inputs acting on the I-cell and ED are paired with cholinergic inputs acting on the O-cell (from t = 10 min to t = 18 min). The EPSCs are calculated as the sum of postsynaptic AMPA and NMDA currents, IAMPA and INMDA, resulting from 10 simulations with white noise on the ED membrane potential. Noisy membrane potentials of the O-cells and I-cells that induce spontaneous spiking are considered in Extended Data Figure 2-4. Normalization of the results was calculated according with the expression (100 + (EPSC – EPSCmin) · (150–100))/(EPSCmax – EPSCmin). Inset, Concentration of GABA released from fast-spiking interneurons (I), calculated according to Equation 15 (see Materials and Methods). E, Normalized SC-evoked EPSC responses from CA1 pyramidal neurons showing that enhancement of EPSCs during a copairing period of 5 min. F, Numerical simulation of normalized EPSC amplitude when glutamatergic inputs acting on the I-cell and ED are paired with cholinergic inputs acting on the O-cell (from t = 10 min to t = 15 min).

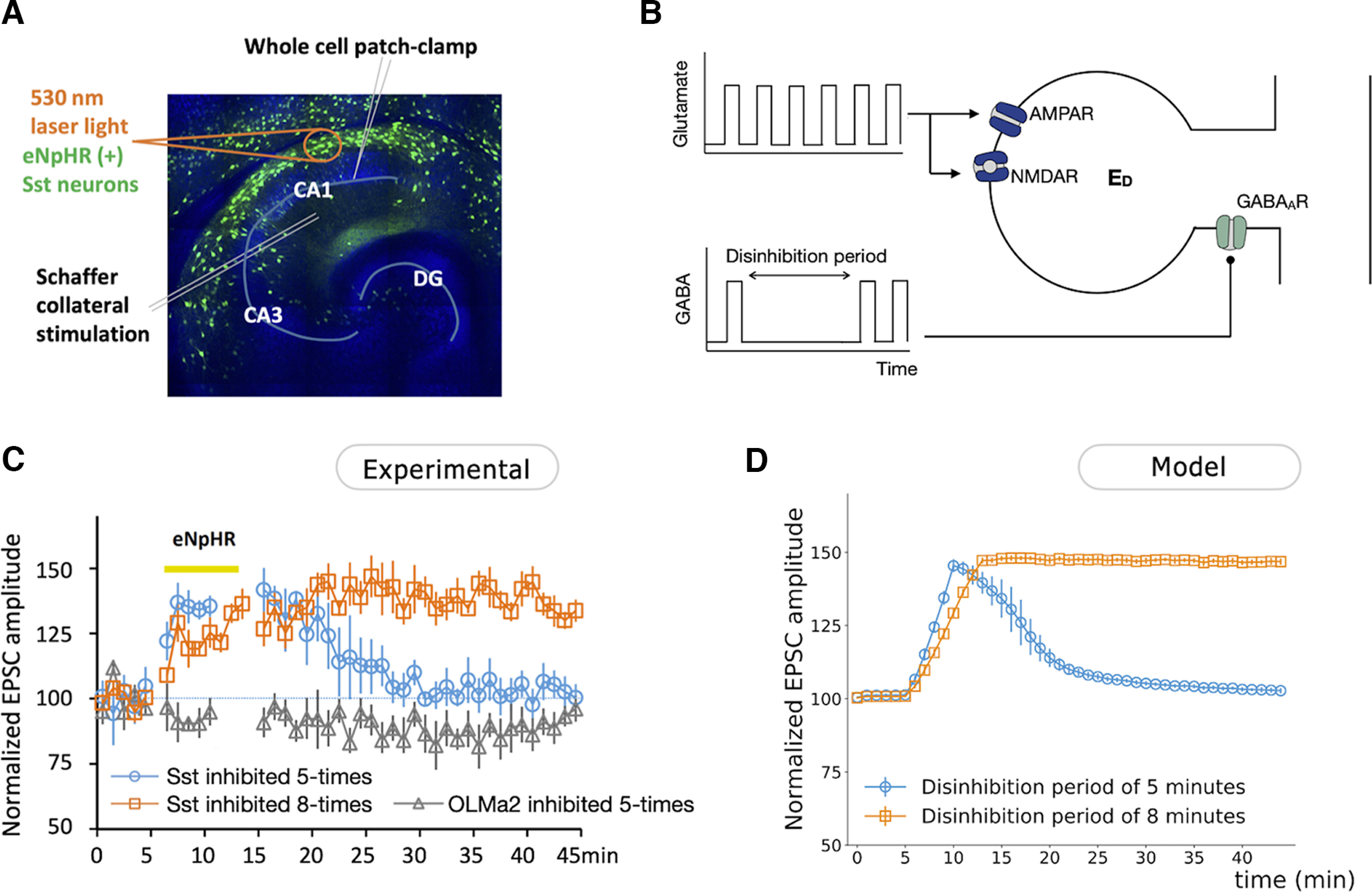

Figure 4.

Disinhibition of CA1 pyramidal cell facilitates the induction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. A, Scheme of in vitro induction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity through concurrent Sst inhibition. EPSCs were recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons. Sst neurons were inhibited via eNpHR that was specifically expressed in Sst-positive neurons. The SC pathway was activated by a stimulating electrode. B, Schematic representation of a CA1 pyramidal neuron dendritic compartment ED with postsynaptic GABAA, AMPA, and NMDA receptors used to study the disinhibitory mechanisms for induction of plasticity at the SC–CA1 excitatory synapse. The dendritic compartment of the pyramidal cell receives one pulse of both glutamate and GABA per minute, except during the disinhibition period, where it only receives pulses of glutamate. The GABA pulse, presumably from the I-cell, is described by a square function with similar amplitude and duration as the glutamate pulse (see Materials and Methods; Extended Data Figs. 4-1, 4-2, justification). Glutamate binds to the excitatory AMPA and NMDA receptors, while GABA binds to the inhibitory GABAA receptor. The synaptic currents and membrane potential of ED when a pulse of glutamate is paired (or not) with a pulse of GABA are shown in Extended Data Figure 4-3. C, Experimental measurements showing the effects of inhibition of Sst and OLMα2 interneurons in s.o. on SC-evoked EPSCs (n = 5 slices for each group). Inhibition of Sst interneurons from t = 5 min to t = 10 min enhanced the SC-evoked EPSC amplitude of the CA1 pyramidal cell, followed by a return to the baseline after the inhibition period (blue line). Inhibition of Sst interneurons from t = 5 min to t = 13 min increased SC-evoked amplitude EPSCs, which remained potentiated after the inhibition period (orange line). D, Numerical simulation of normalized EPSCs of ED for a disinhibition period of 5 min (from t = 5 min to t = 10 min) and 8 min (from t = 5 min to t = 13 min). Normalization of the results was calculated according with the expression (100 + (EPSC – EPSCmin) · (150–100))/(EPSCmax – EPSCmin).

A, Before copairing, the α7 nAChR at OLM is not activated, and the OLM cell is not depolarized (dashed line). During copairing, OLM receives a square pulse of ACh with an amplitude of 1 mm and 5 ms of duration (solid line). The OLM is weakly depolarized (solid line). B, Before copairing, there are no changes in the intracellular calcium concentration Cai (dashed line). During copairing, calcium through α7 nAChR triggers CICR mechanisms that increase the intracellular calcium concentration of the O-cell (solid line). C, An increase in intracellular calcium results in GABA release from the O-cell (GABAO). The neurotransmitter concentration is calculated according to the simplified model (solid line). D, The release of GABAO during copairing suppresses spiking of the I-cell evoked by glutamatergic activation (solid line). E, Before copairing, the spiking of the I-cell is not suppressed and inhibits ED, which cannot depolarize a lot (dashed line). During copairing, ED does not receive inhibition, only excitation from glutamatergic stimulation, and it depolarizes (solid line). Download Figure 2-1, TIF file (7.6MB, tif) .

Simplified neurotransmitter release model. A, Square calcium pulse of 0.10 μm amplitude and 1 ms of duration. B, GABA concentration elicited by a calcium pulse of 0.10 μm amplitude and 1 ms of duration computed using the detailed model of transmitter release described in the study by Destexhe et al. (1998) and using Equation 16. C, Both models of GABA concentration elicit similar synaptic activation functions, rG (described by Eq. 14 with αG = 5 ms/m and βG = 0.18 ms). Download Figure 2-2, TIF file (6.6MB, tif) .

Not much is known about the ACh profile in the synaptic cleft upon release from cholinergic neurons; more specifically, not much is known about the time it takes for ACh to be broken down by the cholinesterase and therefore, how long it is available to bind to the cholinergic receptors. We consider the observations made by Gu and Yakel (2011) that pairing cholinergic inputs 10 ms prior to SC stimulation induces depression of the SC–CA1 synapse, while if the cholinergic inputs are activated 100 ms prior to SC stimulation, potentiation is induced. A–D, A square pulse of ACh followed by a pulse of glutamate 10 and 100 ms after will induce, respectively, depression or potentiation if the duration of the ACh pulse is equal or greater than the glutamate. E–H, If ACh is described by an α function with an instantaneous rise time; the smaller the amplitude of the ACh pulse, the longer the decay time needs to be for the results to agree with those in the study by Gu and Yakel (2011). That being said, we model ACh as a square pulse with a duration of 5 ms and concentration of 1 mm, similar to glutamate. Please note that the decay and duration times, as well as the amplitude, of both the ACh and glutamate pulses serve merely as a guide to what types of neurotransmitter profiles we should consider. They are qualitative, and not quantitative, predictions of the synaptic profile of ACh. Copairing of one pulse of ACh (with different synaptic profiles) with one square pulse of glutamate (with a duration of 5 ms and amplitude of 1 mm) for a relative pairing time Δt of 10 and 100 ms. A, Left, One square pulse of ACh with a duration of 1 ms and concentration of 0.5 mm followed 10 ms after by a square pulse of glutamate produces no changes in the maximal conductance of AMPAR, . Right, Similarly, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, no changes are induced. B, Left, One square pulse of ACh with a duration of 5 ms and a concentration of 0.5 mm followed 10 ms after by a pulse of glutamate decreases the maximal conductance of AMPAR, . Right, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, potentiation is induced. C, Left, One square pulse of ACh with a duration of 1 ms and concentration of 1 mm followed 10 ms after by a square pulse of glutamate produces no changes in the maximal conductance of AMPAR, . Right, Similarly, if the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, no changes are induced. D, Left, One square pulse of ACh followed 10 ms after by a pulse of glutamate with the same characteristics (duration of 5 ms and 1 mm concentration) decrease the maximal conductance of AMPAR, . Right, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, potentiation is induced. E, Left, One pulse of ACh with an amplitude of 0.39 mm and a decay time constant of 1 ms followed 10 ms after by a square pulse of glutamate induces no changes in . Right, Similarly, if the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, no changes are induced. F, Left, One pulse of ACh with an amplitude of 0.39 mm and a decay time constant of 4 ms followed 10 ms later by a square pulse of glutamate depresses . Right, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, potentiation is induced. G, Left, One pulse of ACh with an amplitude of 1 mm and a decay time constant of 1 ms followed 10 ms later by a square pulse of glutamate provokes a decrease in . Right, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, no changes are induced. H, Left, One pulse of ACh with an amplitude of 1 mm and a decay time constant of 4 ms followed 10 ms later by a square pulse of glutamate depresses . Right, If the pulse of glutamate arrives 100 ms after, potentiation is induced. Download Figure 2-3, TIF file (23.1MB, tif) .

A, Time evolution of the membrane potential of the O-cell, I-cell, and ED with noisy background currents when cholinergic inputs are paired with SC inputs, and resultant EPSCs. B, Mean trace of normalized EPSCs after 10 simulations. Adding a noisy background current to the O-cell and I-cell induces spontaneous spiking. Copairing cholinergic and glutamatergic inputs from t = 10 min to t = 18 min induces potentiation of the pyramidal cell EPSC. The O-cell releases GABA when the intracellular calcium concentration is high enough (Eq. 16) and when the cell spikes (Eq. 15). All the remaining parameters are identical to the ones used to produce Figure 6. Noise was incorporated by adding a stochastic term , where ζ is a random Gaussian variable with a mean of μ = 0 and an SD of σ (=1.1, 0.1, and 0.2 for the O-cells, I-cells, and ED, respectively), to the Euler equations describing the Vx. Normalization of the results was calculated according with the expression (100 + (EPSC – EPSCmin) · (150 – 100))/(EPSCmax – EPSCmin). Download Figure 2-4, TIF file (7.4MB, tif) .

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

SC–CA1 EPSCs were recorded from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons under whole-cell patch clamp, similar to recordings described in the studies by Gu and Yakel (2011, 2017). Briefly, 2–3 weeks after culturing, the slices were removed from transwell inserts and put into a submerged chamber, continuously perfused with 95% O2/5% CO2 balanced ACSF (in mm: 122 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 25 glucose) at room temperature. EPSCs were recorded at −60 mV under voltage clamp through a glass pipette filled with an internal solution (in mm: 130 potassium gluconate, 2 MgCl2, 3 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, and 1 EGTA) at pH ∼7.2–7.3 and osmolarity of ∼280–290 mOsm. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Data were digitized with an analog-to-digital signal converter (Digidata 1550) and collected with Clampex. The amplitudes of EPSCs were analyzed with Clampfit, and graphs were drawn with Excel. The amplitudes were normalized to the mean of the 10 min baseline recording before cholinergic pairing or disinhibition pairing. Values were presented as the mean ± SEM.

EPSCs were evoked every 60 s by stimulating the SC pathway with an electrode placed in the stratum radiatum through a stimulator (model S88X, Grass). The stimulation intensity was 1–10 μA for 0.1 ms. To study the effects of cholinergic coactivation on SC–CA1 synaptic plasticity (Fig. 2C,E), cholinergic terminals in the hippocampus were optogenetically activated (10 pulses at 10 Hz, 1 s before SC stimulation) through ChR2 that was selectively expressed in ChAT-cre-positive (cholinergic) neurons. ChR2 was activated with 488 nm laser light (5 mW, 20 ms) through a 40× objective over CA1 stratum oriens (s.o.) near the septum with an spinning disk confocal microscope (Andor Technology). To examine the effects of disinhibition on SC–CA1 synaptic plasticity (see Fig. 4C), somatostatin (Sst)-positive neurons were inhibited optogenetically through eNpHR which was activated through a 40× objective over CA1 stratum oriens with 530 nm laser light (20 mW) for 1 s flanking SC stimulation.

The amplitudes of EPSCs were analyzed with Clampfit, and graphs were drawn with Excel. The amplitudes were normalized to the mean of the 5 min baseline recording before cholinergic pairing or disinhibition pairing. Values were presented as the mean ± SEM EPSC amplitudes at 5 and 30 min after pairing were compared with the amplitude at 5 min before pairing. The effect at 5 min after pairing was considered to be a short-term effect, and the effect at 30 min after pairing was considered to be a long-term effect. Recordings were performed in five slices from three individual mice in each group. Statistical significance was tested by Student’s t test. The sample size was estimated by Student’s t test with an expected effect of 40% change, an expected SD of 15%, and an 80% confidence interval width.

Model

The minimal network used in this study consists of an O-cell, a fast-spiking I-cell, and a pyramidal cell. All the cells in the network are modeled as point neurons. Since we are interested in the local changes at the SC–CA1 synapse, the pyramidal cell is represented by a dendritic compartment (ED). The cells of the network are connected through feedforward connections. Although recurrent connections from the CA1 pyramidal cell and the fast-spiking interneurons may exist, adding this connection did not change our results. Adding connections between the CA1 pyramidal cell and the OLM interneuron also did not significantly alter our results. Therefore, we did not include synapses between the CA1 pyramidal and the OLM cells in our model. Our modeling choice is further supported by experimental studies showing that the IPSC elicited by an OLM interneuron has a small amplitude at the soma of CA1 pyramidal cells since these synapses are on the distal parts of the dendritic tree (Maccaferri, et al., 2000), and that an action potential in CA1 pyramidal cells is insufficient to make the OLM cell membrane potential (Vm) cross the action potential threshold (Ali et al., 1998; Müller and Remy, 2014). Although repeated firing of CA1 pyramidal cells with theta frequency can facilitate excitatory inputs onto OLM, a theta activation protocol of the CA1 cell is beyond the scope of this article.

Neuron dynamics models

The O-cells and I-cells are modeled following the Hodgkin–Huxley formalism [Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952; transient (INa), delayed rectifier potassium (IK), and leak (Ileak)], with synaptic currents (Isyn). Its Vm is described as follows:

| (1) |

where Cm is the membrane capacitance. The Ileak, IK, and INa currents are given by:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where and Ei are, respectively, the maximal conductance and reversal potential of channel i (i = leak, K, Na), and m, h, and n are gating variables that obey the following differential equation:

| (5) |

where αx and βx are voltage-dependent rate constants.

Following Rotstein et al. (2005), we included an applied current (Iapp) = −260 pA, a persistent Na current (Ip), and a hyperpolarization-activated inward current (Ih; with a slow and fast component) on the O-cells, as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

While the gate variable p obeys Equation 5, hf and hs are described by the following equation:

| (8) |

where x∞ is the voltage-dependent steady state and τx is the time constant. Definitions for the αx, βx, x∞, and τx for each of the dynamic variables are as follows.

For the O-cells:

For the I-cells:

The parameter values used in the simulations are the ones presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of pyramidal cell, OLM interneuron, and fast-spiking interneuron dynamics

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| O-cells | |

| Cm | 100 pF |

| gleak | 50 nS |

| Eleak | −70 mV |

| 1100 nS | |

| EK | −90 mV |

| 5200 nS | |

| ENa | 55 mV |

| 50 nS | |

| 145 nS | |

| Eh | −20 mV |

| I-cells | |

| Cm | 100 pF |

| gleak | 10 nS |

| Eleak | −67 mV |

| 8000 nS | |

| EK | −100 mV |

| 10,000 nS | |

| ENa | 50 mV |

| ED | |

| Cm | 100 pF |

| gleak | 1 nS |

| Eleak | −68 mV |

All the parameter values and expressions here described were taken from the study by Rotstein et al. (2005), considering a surface area of 1 × 10−4 cm2, except for the reversal potential of the leakage current of the OLM, which was set to have the resting potential of the OLM cells at −60 mV, as reported in the study by Leão et al. (2012).

Since we are interested in studying local synaptic changes of the SC–CA1 synapse, we use the following equation to describe the activity of the pyramidal cell dendritic compartment:

| (9) |

The parameters C, gleak, and Eleak were set to 100 pF, 1 nS, and −68 mV, respectively.

For the simulations presented in Figure 2D, noise was added to the dendritic compartment ED to allow direct comparison with the experimental results portrait in Figure 2C. In addition to ED, white noise was added to the O-cells and I-cells to study plasticity induction when these cells show spontaneous spiking (Extended Data Figs. 2-1, 2-2, 2-3, 3-1, 3-2, 4-1). Since we used the Euler method to solve the differential equations describing VO, VI, and VED, ( ) noise was incorporated by adding a stochastic term ( ), where is a random Gaussian variable with mean and SD σ(=1.1, 0.1, and 0.3 for the O-cells, I-cells, and ED cells, respectively).

Synaptic models

The O-cell model includes a current mediated by α7 nAChR channels, which in the real OLM neurons are presynaptic to the O-cell to I-cell synapse. The description of the current used is an adaptation of the model proposed in the study by Graupner et al. (2013), and it is given by the following equation:

| (10) |

where is the maximal conductance of the α7 nAChR channel, and Eα7 is the reversal potential. The opening gate variable rα7 is described by Equation 8, with τrα7 (= 5 ms) constant and r(α7)∞ given by the following:

| (11) |

where n is the Hill’s coefficient of activation.

The I-cell has excitatory AMPA and inhibitory GABAA synaptic currents, described by the following set of equations:

| (12) |

| (13) |

The gating variable rx is, as described in the study by Destexhe et al. (1998), given by the following:

| (14) |

where αx and βx are the opening and closing rates of the receptor channel, and [T] is the concentration of the neurotransmitter that is available for binding.

The GABA released by the I-cell is described by using the Destexhe et al. (1998) simplified neurotransmitter release model. The intervening reactions in the release process are considered to be fast: a presynaptic action potential elicits a rapid influx of calcium, leading to the activation of transmitter-containing vesicles and neurotransmitter release. A stationary relationship between presynaptic voltage and neurotransmitter release is deduced by fitting the model to experimental results. The following equation gives the neurotransmitter release as a function of the presynaptic voltage:

| (15) |

where Tmax= 1 mm is the maximal neurotransmitter concentration, Kp = 5 mV gives the steepness of the function, and Vp = 2 mV sets the value at which the function is half-activated. These parameters were directly taken from the study by Destexhe et al. (1998).

Spiking of the OLM cells directly because of the nAChR activation has not been clearly characterized. Experimentally measured nicotinic responses of OLM cells are small (Leão et al., 2012), and, although they may modulate the firing rate of the neuron, it is unlikely they are causing spiking on their own (Fig. 2D). For that reason, we consider that GABA release by the O-cell results from the activation of presynaptic α7 nAChR on O–I GABAergic synapses.

Experimental studies revealed that the activation of α7 nAChRs trigger intracellular calcium rise and calcium-dependent signaling pathways—in particular calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from intracellular stores—that enhance the release of neurotransmitter at presynaptic terminals (Tsuneki et al., 2000; Dajas-Bailador et al., 2002; Griguoli and Cherubini, 2012). To avoid the detailed computation of the mechanisms whereby calcium leads to exocytosis, we assume a sigmoid relationship between intracellular calcium and transmitter concentration given by the following:

| (16) |

where Tmax= 1 mm is the maximal neurotransmitter concentration, K(Ca)p = 1 × 10−6 mm gives the steepness of the function, and Cap = 4 × 10−5 mm sets the value at which the function is half-activated. These parameters were chosen so that a pulse of calcium elicits GABA release with approximately the same characteristics (amplitude and duration) as the detailed model of transmitter release in the study by Destexhe et al. (1998; Extended Data Fig. 2-2, compare detailed and simplified models of neurotransmitter release). Note that although Cap is below the calcium resting values typically observed, in our model the calcium concentration decays to zero, similar to that in the studies by Graupner and Brunel (2005, 2012), Higgins et al. (2014), and Shouval et al. (2002).

The passive dendritic compartment of the pyramidal cell ED is modeled using synaptic GABAA, AMPA, and NMDA currents. The GABAA and AMPA currents are given by Equations 12 and 13, respectively. The following equation describes the NMDA current:

| (17) |

where rN is the gating variable described by Equation 14. Because of the presence of an Mg2+ block, the NMDA channels have an additional voltage-dependent term, B(Vm), defined as follows:

| (18) |

The parameters αA, βA, EA, αN, βN, EN, [Mg2+], αG, βG, and EG were estimated by Destexhe et al. (1998) by fitting the models of postsynaptic AMPA, NMDA and GABAA currents to experimental data. Regarding the synaptic currents of ED, the maximal conductances of AMPA and NMDA receptors were chosen such that at V = −70 mV, a glutamate pulse of 1 mm and 10 ms duration evoked AMPA and NMDA currents with amplitudes of 240 and 40 pA, respectively (Andrásfalvy et al., 2003). The maximal conductance of GABAA receptors was chosen such that at V = 0 mV a pulse of GABA with 1 ms duration and a concentration of 1 mm evokes a current with an amplitude of 500 pA (Schulz et al., 2018). For the I-cell, the AMPA receptor maximal conductance value is such that one pulse of glutamate coming from the SC evokes a volley of action potentials. Concerning the α7 nAChR postsynaptic current, the parameters EC50, τrα7, and n were taken from the study by Graupner et al. (2013), where the kinetics of α7 nAChR is described. The parameter Eα7 was deduced from the study by Castro and Albuquerque (1995), and gα7 was chosen such that activation of the α7 nAChR by a pulse of ACh evokes a current of 35 pA (Leão et al., 2012). The values of the parameters can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter values of synaptic currents IAMPA, INMDA, IGABAA, and Iα7

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| αA | 1.1 ms−1 mM−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| βA | 0.19 ms−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| 7*, 4† nS | Andrásfalvy et al. (2003) | |

| EA | 0 mV | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| [Mg2+] | 1 mm | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| αN | 0.072 ms−1 mM−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| βN | 6.6 × 10−3 ms−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| 25 nS | Andrásfalvy et al. (2003) | |

| E N | 0 mV | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| αG | 5 ms−1 mM−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| βG | 0.18 ms−1 | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| 14*, 7† nS | Schulz et al. (2018) | |

| EG | −80 mV | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| E α 7 | 0 mV | Castro and Albuquerque (1995) |

| 3 nS | Leão et al. (2012) | |

| EC50 | 80 × 10–3 mm | Graupner et al. (2013) |

| τrα7 | 5 ms | Graupner et al. (2013) |

| n | 1.73 | Graupner et al. (2013) |

| T max | 1 mm | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| K p | 5 mV | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| V p | 2 mV | Destexhe et al. (1998) |

| K (Ca)p | 1 × 10–6 mm | Materials and Methods |

| Cap | 4 × 10–5 mm | Materials and Methods |

*Values refer to the conductance of postsynaptic channels on the fast-spiking interneurons.

†Values refer to the conductances of the dendritic compartment ED.

CICR mechanism

Calcium entry through α7 nAChRs initiates calcium release from internal stores (Tsuneki et al., 2000; Dajas-Bailador et al., 2002; Griguoli and Cherubini, 2012). The calcium concentration in the cytosol of OLM cells (Cai) is described by the following equation:

| (19) |

where ξ′=2.1 × 10−6 mm/(ms pA) is a parameter that converts current into concentration, α′ = 0.05 reflects the 5% calcium permeability of the α7 nAChRs (Vernino et al., 1994), and τCa is the calcium decay constant. The parameter ξ′ was chosen so that the intracellular calcium concentration is of the same order of magnitude as observed experimentally in the study by Sabatini et al. (2002; i.e., in the 0.1 μm range). The parameter τCa was taken directly from the same study. CaIS represents the calcium concentration of the internal stores given by the following:

| (20) |

where τ (= 10 ms) is the calcium decay constant, and w∞ is the open probability of calcium-permeable channels on the internal store, given by the following:

| (21) |

where kd (= 2 × 10−4 mm) is the half-activation of the function. The model assumes three calcium binding sites (Young and Keizer, 1992) and a calcium concentration at the internal stores of 0.44 μm at rest (this value can be different as long as it is bigger than the intracellular calcium concentration Cai). Please note that the CICR mechanism described is a simplification of the model proposed by Rinzel (1985), where we limit the model to account for the calcium activation sites of the calcium-permeable IP3 receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum.

Model of synaptic plasticity

To study plasticity induction at the SC–ED synapse, we use a calcium-based synaptic plasticity model based on the study by Shouval et al. (2002). We assume that changes in the AMPA receptor conductance reflect changes in the strength of the excitatory SC–CA1 synapse. Our synaptic plasticity model is formulated as follows:

| (22) |

where σ is a decay constant and g0 (= 4 nS) is the value of the maximal conductance of the AMPAR at t = 0. The variable η is a calcium-dependent learning rate described by Equation 23, and Ω determines the sign magnitude of synaptic plasticity as a function of the intracellular Ca levels (Eq. 24).

| (23) |

| (24) |

The parameters θ↑ and θ↓ define the potentiation and depression onset (i.e., the calcium levels that trigger the removal and insertion of AMPAR in the membrane, respectively), and and represent the maximal insertion and removal rate of the AMPARs from the membrane. Please note that on the original model, the parameters θ↑ and θ↓ are represented by θp and θd, and define the potentiation and depression threshold, respectively, but, as will be evident in the Results section, we find that this terminology can be misleading (i.e., we show that crossing these levels is necessary but not sufficient for potentiation).

We assume that the primary source of Ca2+ in ED is the calcium flux entering the cell through the NMDA receptor channels. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration evolves according to the following equation:

| (25) |

where ξ is a parameter that converts current into concentration, α = 0.1 refers to the fact that only ∼10% of the NMDA current is composed of calcium ions (Burnashev et al., 1995), and τCa (= 12 ms) refers to the calcium decay constant. The parameter ξ was chosen so that the intracellular calcium concentration is of the same order of magnitude as observed experimentally in the study by Sabatini et al. (2002). The parameter τCa was taken directly from the same study. P1, P2, P3, and P4 were chosen to have a calcium-dependent learning rate that increases monotonically with calcium levels (Shouval et al., 2002). The parameters θ↑ and θ↓ were determined such that before the copairing period the calcium concentration does not cross either while crossing the potentiation onset θ↑ when pairing starts (with θ↑ > θ↓). The parameters σ, and were chosen to reproduce the experimental results concerning potentiation of CA1 PYR cell EPSC during coactivation of SC and disinhibition/cholinergic inputs (with > ).

Stimulation protocol

ACh–SC pairing

We constructed a minimal feedforward circuit with an O-cell, a fast-spiking I-cell, and the pyramidal cell s.r. ED connected, as schematically shown in Figure 2B, to examine mechanistically how pairing cholinergic activation of the O-cell with glutamatergic activation of the I-cell and ED can potentiate the EPSCs of ED. We look at how the EPSC of ED, modeled as the sum of the postsynaptic AMPA current (IAMPA) and NMDA current (INMDA), changes when the glutamatergic inputs acting on the I-cell and ED are paired with the cholinergic inputs that act on the presynaptic α7 nAChR of the O-cell during a copairing period of 5 and 8 min, identical to the experimental protocol. The I-cell and ED receive one glutamate pulse per minute before, during, and after the copairing period. During the copairing period, the O-cell gets a pulse of ACh per minute, 100 ms before each glutamate pulse (Δt = 100 ms). Not much is known about the concentration profile of ACh in vivo, but it is believed that it can be cleared from the synaptic cleft within milliseconds. After testing different ACh profiles, we decided to model ACh as a square pulse with a duration of 5 ms and concentration of 1 mm, similar to glutamate, although similar results were obtained for a variety of profiles of ACh (Extended Data Fig. 2-3, for more details).

We explore the copairing temporal parameters that regulate plasticity by fixing the frequency of stimulations at 1 pulse/min while varying the copairing period tpair (Figs. 2, 3A, results). We also study how the frequency of stimulation modulates synaptic plasticity by fixing tpair at 4 min while changing the frequency of copaired stimulation (Fig. 3B). Finally, we consider different pairing times of ACh and glutamate (Δt; Fig. 3C,D).

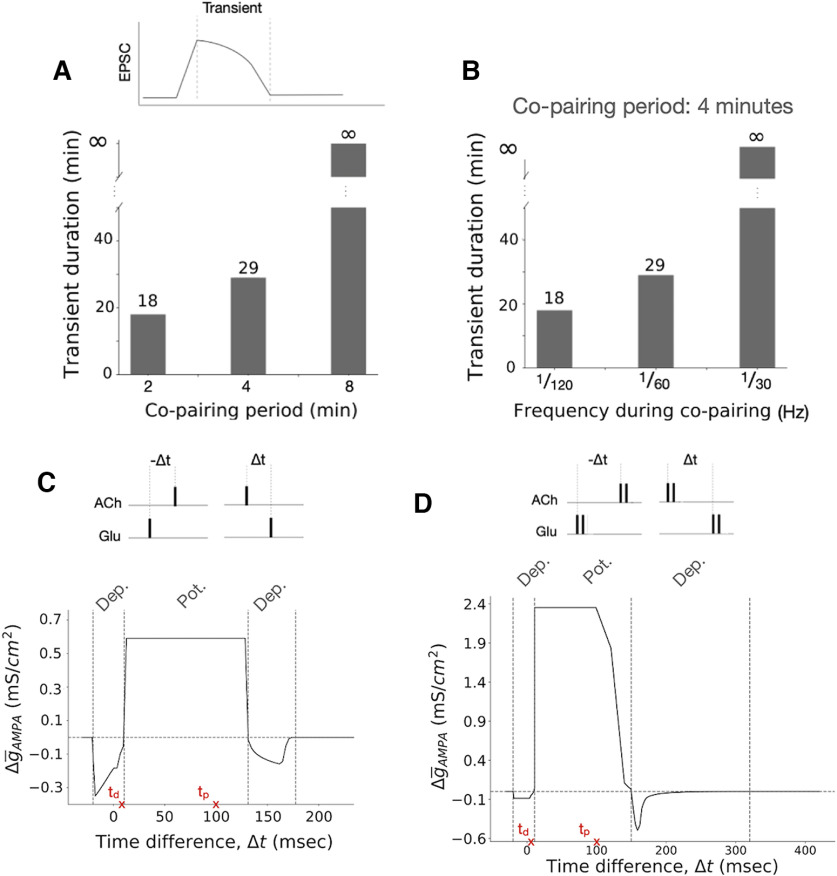

Figure 3.

Copairing temporal parameters determines the duration and polarity of synaptic plasticity: relative timing among cholinergic and glutamatergic stimulation, the extent of the copairing period, and the frequency of stimulation (model results). A, Synaptic strength transient duration is proportional to the extent of the pairing period. Here, the transient duration is defined as the time it takes the EPSC to go back to baseline after copairing is over. The I-cell and ED receive a pulse of glutamate per minute. During the copairing period, the O-cell receives a pulse of ACh per minute, 100 ms before the glutamate pulses. B, Synaptic strength transient duration is proportional to the ACh and glutamate pulses frequency during the copairing period. Before and after the copairing period, the I-cell and ED receive a pulse of glutamate per minute. During the copairing period (4 min), the frequency changes to 1/20, 1/60, or 1/30 s, and the O-cell receives a pulse of ACh 100 ms before the glutamate pulses with the same frequency. C, Relative pairing timing of single pulses provides a window of opportunity for plasticity. If glutamatergic inputs are administered within 10.4 ms < Δt < 131.1 ms, the ED excitatory synapse is potentiated. If glutamatergic inputs are administered within −19.9 ms < Δt < 10.4 ms or 10.4 ms < Δt < 131.1 ms, depression is induced. The change in the AMPAR conductance Δ AMPA is measured 60 ms after one pairing. The relative time between cholinergic and glutamatergic activation of the network determines how efficiently the O-cells suppress spiking of the I-cells, as shown in Extended Data Figure 3-1. If noise is added to the membrane potential of ED, the window of depression and potentiation is not as well defined, as shown in Extended Data Figure 3-2. D, Pairing multiple pulses of glutamate and ACh can change the window of opportunity for plasticity. Two pulses of glutamate and ACh with a frequency of 2 Hz are paired. If glutamatergic inputs arrive within −19.9 ms < Δt < 10.9 ms or 149.9 ms < Δt < 320 ms of the cholinergic inputs, depression is induced. If glutamatergic inputs are administered within 10.9 ms < Δt < 149.9 ms, the ED excitatory synapse is potentiated. The change in the AMPAR conductance Δ AMPA is measured 60 ms after one pairing. The pairing times of cholinergic and SC inputs found by Gu and Yakel (2011) to induce short-term depression and long-term potentiation at the SC–CA1 synapse (indicated with the red cross) are within our range of depression and potentiation.

Tightly timed pairing of cholinergic to glutamatergic inputs can cancel the I-cell feedforward inhibition. For Δt = –30 ms (Region I), a pulse of glutamate activates the I-cell. When the OLM cell receives a pulse of ACh 30 ms after and releases GABA, the I-cell already emitted two spikes and inhibit ED, no plasticity is induced. For Δt =0 ms (Region II), the I-cell and OLM receive a pulse of glutamate and ACh, respectively, simultaneously. Due to its fast dynamics, the I-cell manages to emit one spike before being inhibited by GABAO. The I-cell inhibits ED only moderately and depression is induced. For Δt = 100 ms (Region III), OLM receives an ACh pulse at t = 0 ms and releases GABAO into the I-cell. When the I-cell receives glutamate 100 ms after, it is hyperpolarized and cannot spike; potentiation is induced. For Δt = 150 ms (Region IV), the hyperpolarization of the I-cell is starting to wear off and the cell manages to emit one spike, sending moderate inhibition to ED; depression is induced. For Δt = 300 ms (Region V), the I-cell can emit two spikes when it receives glutamate 300 ms after cholinergic activation; no plasticity is induced. Download Figure 3-1, TIF file (5.4MB, tif) .

Mean relative pairing timing of single pulses of ACh and glutamate with noisy membrane potential of ED after 10 simulations. Noise was incorporated by adding a stochastic term , where ζ a random Gaussian variable with a mean of μ = 0 and an SD of σ = 0 to the Euler equations describing the VED. The mean trace of normalized EPSCs after 10 simulations. When a noisy membrane potential is considered, the transition between the depression and potentiation windows is less sharp (Fig. 3C, comparison). Download Figure 3-2, TIF file (2.7MB, tif) .

Disinhibition–SC pairing

To study the disinhibitory mechanism of plasticity induction, we consider the dendritic compartment ED subjected to glutamate and GABA pulses, as schematically shown in Figure 4B. Both GABA and glutamate are modeled as square pulses with a duration of 1 ms and 1 mm of amplitude (Extended Data Fig. 4-2A, different durations and amplitudes of glutamate and GABA reproduce the same results), and a frequency of 1 pulse/min, with glutamate preceding GABA by 2 ms.

I-cell GABA release evoked can be approximated by a square function. A, Membrane potential of the I-cell when it receives two pulses of glutamate (with an amplitude of 1 mm and a duration of 3 ms) with a frequency of 0.2 ms. B, GABA release from I-cell when it receives the action potentials described in A, calculated using Equation 15. Download Figure 4-1, TIF file (4.2MB, tif) .

Sets of parameters that qualitatively reproduce Figure 4D. A, Numerical simulations of normalized EPSCs of ED for varying the amplitude and duration of the glutamate and GABA pulses. B, Parameters of maximum depression (γ↓), maximum potentiation (γ↑), synaptic plasticity decay constant (σ), and potentiation threshold (θ↑) from the shaded areas qualitatively reproduce Figure 4D. The quality of EPSC traces generated with different parameters was evaluated by measuring the relative variations of EPSC amplitude (in non-normalized and non-noisy simulations) from 5 to 30 min after the disinhibition period was over for a 5 and 8 min disinhibition period. Simulations were the variation (percentage of plasticity) was<4% and >22% for the long and short disinhibition periods, respectively, and were considered to conserve the shape of the experimental EPSC trace. This ensures that, for the long disinhibition period, the EPSCs do not decay faster than the experimental EPSCs observed, or slower, for the case of the short period, and therefore have a similar shape. Experimental measures describe the relative increase in EPSC amplitude from the baseline value to 5 min (%(5-B)) and 30 min (%(30-B)) after the disinhibition period is over (see the Results section for the values of %(5-B) and %(30-B) for 5 and 8 min disinhibition periods). This allows us to derive the relative changes from 5 to 30 min [%(30-5) = (%(30-B) – %(5-B))/(100 + %(5-B)) × 100]. By considering the relative changes between 5 and 30 min after the disinhibition period instead of the changes between the baseline and 5 and 30 min, we decrease the number of conditions to evaluate and the computational cost of performing the parameter exploration. The gray and beige areas represent the parameter space where both conditions are met. Note that increasing the synaptic plasticity decay constant σ decreases the robustness of the model to variations of the maximum depression and potentiation, γ↓ and γ↑ (B, beige area). On the other hand, increasing the potentiation threshold θ↑ changes the robustness of the model to changes in γ↑. As θ↑ approaches the depression threshold θ↓ or the maximum calcium amplitude Camax, the robustness in γ↑ decreases. b1, Gray and beige area: parameter space γ↓ – γ↑ where the percentage of plasticity is<4% for an 8 min disinhibition period and >22% for a 5 min disinhibition period for σ = 0.004 and σ = 0.005, respectively. b2, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 5 min and σ = 0.005 for different values of γ↓ and γ↑. b3, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 8 min and σ = 0.005 for different values of γ↓ and γ↑. b4, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 5 min and σ = 0.004 for different values of γ↓ and γ↑. b5, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 8 min and σ = 0.004 for different values of γ↓ and γ↑. b6, Gray area: parameter region γ↑ – θ↑ where the percentage plasticity is<4% for an 8 min disinhibition period and >22% for a 5 min disinhibition period for σ = 0.004. b7, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after the disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 5 min for different values of γ↑ and θ↑. b8, Relative variation of EPSC amplitude from 5 to 30 min after the disinhibition period (percentage plasticity) for a disinhibition period of 8 min for different values of γ↑ and θ↑. b9, Numerical simulations of normalized EPSCs of ED for different points of the parameter space γ↓ – γ↑ and γ↑ – θ↑. Download Figure 4-2, TIF file (27.5MB, tif) .

A square GABA pulse with 1 mm amplitude and 1 ms of duration evokes a GABAA current at ED, and decrease NMDA current and depolarization. A, One square pulse of GABA with 1 mm amplitude and 1 ms of duration evokes an inhibitory GABAA current at ED (IGABAA). B, When ED receives a GABA square pulse, glutamatergic activation of ED only evokes a depolarization of –63.56 mV (dashed line). C, When ED does not receive GABA inputs, glutamate inputs evoke a depolarization of –58.25 mV (solid line). When ED does not receive GABA inputs, glutamatergic activation evokes a NMDA current of 7.90 pA (solid line). When it receives a GABA square pulse, the evoked NMDA current is 6.75 pA (dashed line). Download Figure 4-3, TIF file (5.1MB, tif) .

Parameters of the model

We used experimentally determined values or values from previous modeling studies for most of the parameters. Parameters that could not be set experimentally were determined by experimental constraints imposed on the model, namely, the maximal conductances x, and the synaptic plasticity model parameters are indicated with a dash in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter values for calcium dynamics and synaptic plasticity

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| σ | 0.0040 ms−1 | Materials and Methods |

| P1 | 1.5e-6 | Shouval et al. (2002) |

| P2 | P1 × 10−4 | Shouval et al. (2002) |

| P3 | 13 | Shouval et al. (2002) |

| P4 | 1 | Shouval et al. (2002) |

| θ↑ | 0.34 μm | Materials and Methods |

| θ↓ | 0.31 μm | Materials and Methods |

| γ↑ | 0.0687,* 0.0699† nS/ms | Materials and Methods |

| γ↓ | 0.0375 nS/ms | Materials and Methods |

| α | 0.1 | Burnashev et al. (1995) |

| ξ | 0.006,* 0.045† μm/(ms/pA) | Sabatini et al. (2002) |

| τCa | 12 ms | Sabatini et al. (2002) |

| ξ′ | 2.1 × 10–6 mm/(ms pA) | Materials and Methods |

| α′ | 0.05 | Vernino et al. (1994) |

| τ | 10 ms | Materials and Methods |

| k d | 2 × 10–4 mm | Materials and Methods |

All the parameter values are defined in Tables 1, 2, and 3. We strived to constrain the parameters to physiological values based on literature, those parameters that we could not directly constrain, were optimized to ranges that ensure that our simulations showed that the measurable variables used are within the physiological range.

We note that different sets of parameters can reproduce our results (Extended Data Fig. 4-2), and that they can be more finely tuned as more experimental data are collected and more constraints are imposed on the model. This also applies for the description of the neurotransmitters ACh, GABA, and glutamate. Despite not having access to data regarding their profile in the synaptic cleft during the experiments performed, we note that the profiles of different neurotransmitters can reproduce our results. In some cases, it may require that free parameters such as ξ and ξ′, the parameters that convert currents into the calcium concentration, are readjusted to keep calcium within the electrophysiological range. In addition, for the particular case of the ACh dynamics, much higher concentrations than the ones considered here may require a more detailed description of the CICR mechanism by, for example, adding a calcium pump to the membrane of the internal stores and the OLM neuron to control the calcium flux into the intracellular medium.

We approximate the solutions of the differential equations with the Euler’s method. We use a step size of 0.02 ms, which is the biggest value for which we have nonerratic solutions. To ensure the stability of our numerical method, we ran a number of pilot simulations with a smaller time step. We found that, for example, a timestep of 0.01 ms did not produce different results, while increasing considerably the time of computation.

Code accessibility

The code described in the article is freely available at https://github.com/inesCompleto/Hippocampal_Plasticity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study (Gu et al., 2020) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Coactivation of cholinergic and glutamatergic inputs modifies the SC-CA1 synaptic transmission

First, we set out to study the cholinergic mechanisms by which activation of α7 nAChRs on OLMα2 neurons facilitates the potentiation of SC–CA1 synapses. We designed a biophysical model to reproduce the experimental results reported in the study by Gu et al. (2020; Fig. 2A,C) using the minimal network scheme presented in Figure 2B.

In our model, similar to what was reported in the study by Gu et al. (2020), repeated coactivation of cholinergic and glutamatergic inputs potentiates the SC–CA1 synapse (Fig. 2D). The longer the coactivation period, the longer lasting are these changes.

From Figure 2D, we see that during the copairing period (from t = 10 min to t = 18 min), the EPSC is increased. This increase in our model is maintained for an extended period after the copairing period is over (black line), matching experimental results. We also see that GABA release from the I-cells, GABAI, decreases significantly (Fig. 2D, inset). Before the copairing period, glutamatergic inputs activate the I-cell. This results in the inhibition of the pyramidal cell dendritic compartment ED, which shows an SC-evoked depolarization immediately followed by hyperpolarization of its membrane potential. During the copairing period, activation of α7 nAChRs 100 ms before SC stimulation results in a flux of calcium into the OLM cell that will initiate CICR from internal stores exerting a positive feedback. The increase in intracellular calcium concentration induces the release of GABA, as described by Equation 16. GABAergic inputs from the OLM cell disable the SC-evoked activation of the I-cell. As a result, ED does not receive GABAergic inputs (Extended Data Fig. 2-1).

If we reduce the maximal conductance of the α7 nAChR, α7 from 3 to 1.7 nS as an approximation of the effect of α7 knockout, copairing no longer potentiates the EPSC of ED (Fig. 2D, orange line). These observations are in accordance with experimental results showing that this form of EPSC boost was abolished by knockout of the α7 nAChR in OLMα2 interneurons (Fig. 2C).

We then examined how the key parameters of the copairing protocol influence the plasticity of the SC–CA1 EPSCs. According to our model, the duration of the copairing period, the relative time between the cholinergic and glutamatergic inputs, as well as their frequency during the copairing period can modulate the efficiency and direction of plasticity. Our simulations show that the longer the copairing period, the longer it takes the EPSCs to return to the baseline value once the copairing period is over (Figs. 2D,F, 3A). We observe a positive relationship between the frequency of the glutamatergic and cholinergic inputs during a fixed period of paring protocol and the potentiation transient duration (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, our simulations suggested that while changing the copairing period and the frequency of stimulation modulates the efficiency of the induction of potentiation, it does not change the direction of plasticity. Only when varying the relative time between the ACh and glutamate pulses could we induce a change in the plasticity direction. For single-pulse pairing, potentiation will be induced if the glutamatergic inputs arrive at I and ED within 10.4< Δt < 131.1 ms following the ACh pulse. If −19.9< Δt < 10.4 ms or 131.1< Δt < 177.4 ms, depression is induced (Fig. 3C). If we pair doublets of glutamate and ACh with a frequency of 2 Hz instead of single pulses, the potentiation window is 10.9< Δt < 149.9 ms, while the depression window is −19.9< Δt < 10.9 ms and 149.9< Δt < 320 ms (Fig. 3D). In both cases, the potentiation and depression window are well defined. These results agree with experimental findings by Gu and Yakel (2011) showing that the activation of cholinergic inputs 100 and 10 ms before SC stimulation induced SC to CA1 long-term potentiation and short-term depression, respectively.

In the simulations performed to reproduce Figure 3, C and D, we do not consider noisy membrane potentials. As a result, we obtain sharp transition between the regions of depression and potentiation—the timing at which GABAO is released from the O-cell finely tunes the number of spikes emitted by the I-cell. As we show in Extended Data Figure 3-2, adding a noisy background induces spontaneous spiking of the O-cells and I-cells, which results in smoother transitions.

Disinhibition of the CA1 pyramidal cell dendritic compartment enables potentiation of the SC–CA1 synaptic transmission

Our model shows a decrease in GABA release from I-cells during the copairing period (Fig. 2D, inset) that results in disinhibition of the ED. To study the role of this disinhibition in the potentiation of the SC–CA1 excitatory synapse, we used a model of ED submitted to a pulse of glutamate followed by a pulse of GABA, except during a disinhibition period when it only receives pulses of glutamate (Fig. 4B, scheme). This corresponds to experiments where we paired, in vitro, the inhibition of Sst interneurons (analogous to the I-cells in the model) with SC stimulation that provides the glutamatergic inputs (Fig. 4A).

We would like to note that, according to our model, the rise and decay time of GABA concentration release that results from the spiking of the I-cells is almost instantaneous (Extended Data Fig. 4-1). Therefore, in this section, the GABAergic inputs into ED are modeled as square pulses. For simplicity, both glutamate and GABA release pulses are modeled as square pulses with a duration of 1 ms and 1 mm of amplitude. It is important to note that pulses with amplitudes and durations different from the ones considered here would reproduce the same results, as long as the duration and amplitude of glutamate and GABA match each other (Extended Data Fig. 4-2A). ED receives one pulse of glutamate per minute, followed by a pulse of GABA 2 ms after, except during a disinhibition period when it only receives pulses of glutamate. We note that this simulated stimulation and pairing choice directly follows the experimental protocol (see Materials and Methods).

In our model simulations, we observe that before the disinhibition period, there were no changes in the simulated EPSC amplitude of ED. During the disinhibition period, the EPSC amplitude increases, and the longer the disinhibition period lasts, the longer these changes last. More specifically, for a disinhibition period of 5 min, the EPSC returns to baseline once the disinhibition period is over. For a longer disinhibition period of 8 min, the EPSC remains potentiated long after the disinhibition period is over (Fig. 4D). These results hold for different values of the plasticity parameters (Extended Data Fig. 4-2B). After 5 min of ED disinhibition, the EPSC amplitude was increased from 169.40 to 285.34 pA. After 8 min of disinhibition, the EPSC amplitude increased to 361.33 pA. This is in accordance with experimental results, where inhibition of Sst interneurons projecting to CA1 pyramidal cells was paired with SC stimulation for a short and long period (Fig. 4C). Inhibition of Sst interneurons via eNpHR resulted in increased SC–CA1 EPSC amplitude not only during the Sst inhibition but also after the end of Sst inhibition. The EPSC enhancement after the Sst inhibition lasted ∼10 min after 5 min of Sst inhibition and >30 min after 8 min of Sst inhibition. After 5 min of Sst inhibition, the EPSC amplitude was significantly increased at 5 min after the end of Sst inhibition (31.8% increase compared with baseline, p = 0.0003) but returned to baseline at 30 min after Sst inhibition (2.8% increase compared with baseline, p = 0.79). After 8 min of Sst inhibition, the EPSC amplitude was significantly increased at both 5 min after the end of Sst inhibition (37.3% increase compared with baseline, p < 0.0001) and 30 min after Sst inhibition (32.5% increase compared with baseline, p < 0.0001). Experiments showed that the inhibition of OLMα2 interneurons via eNpHR did not change the amplitude of SC–CA1 EPSC, indicating that the Sst interneurons inducing potentiation do not include OLM (Fig. 4C, gray line).

AMPARs are known to play an important role in regulating and expressing synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Barria et al., 1997). From Figure 5, we see that there is an increase of AMPA during the disinhibition period. The longer the disinhibition period, the more significant the increase. For a disinhibition period of 5 min, there is an increase of AMPA from 4 to 6.9 nS during disinhibition. Afterward, AMPA gradually goes back to its baseline value (Fig. 5A). For a disinhibition period of 8 min, AMPA increases from 4 to 8.83 nS. When the disinhibition period is over, AMPA remains potentiated (Fig. 5B). It is important to note that without regular synaptic stimulation, AMPA decays back to its resting value after the disinhibition period (i.e., AMPA has only one stable fixed point and is not bistable).

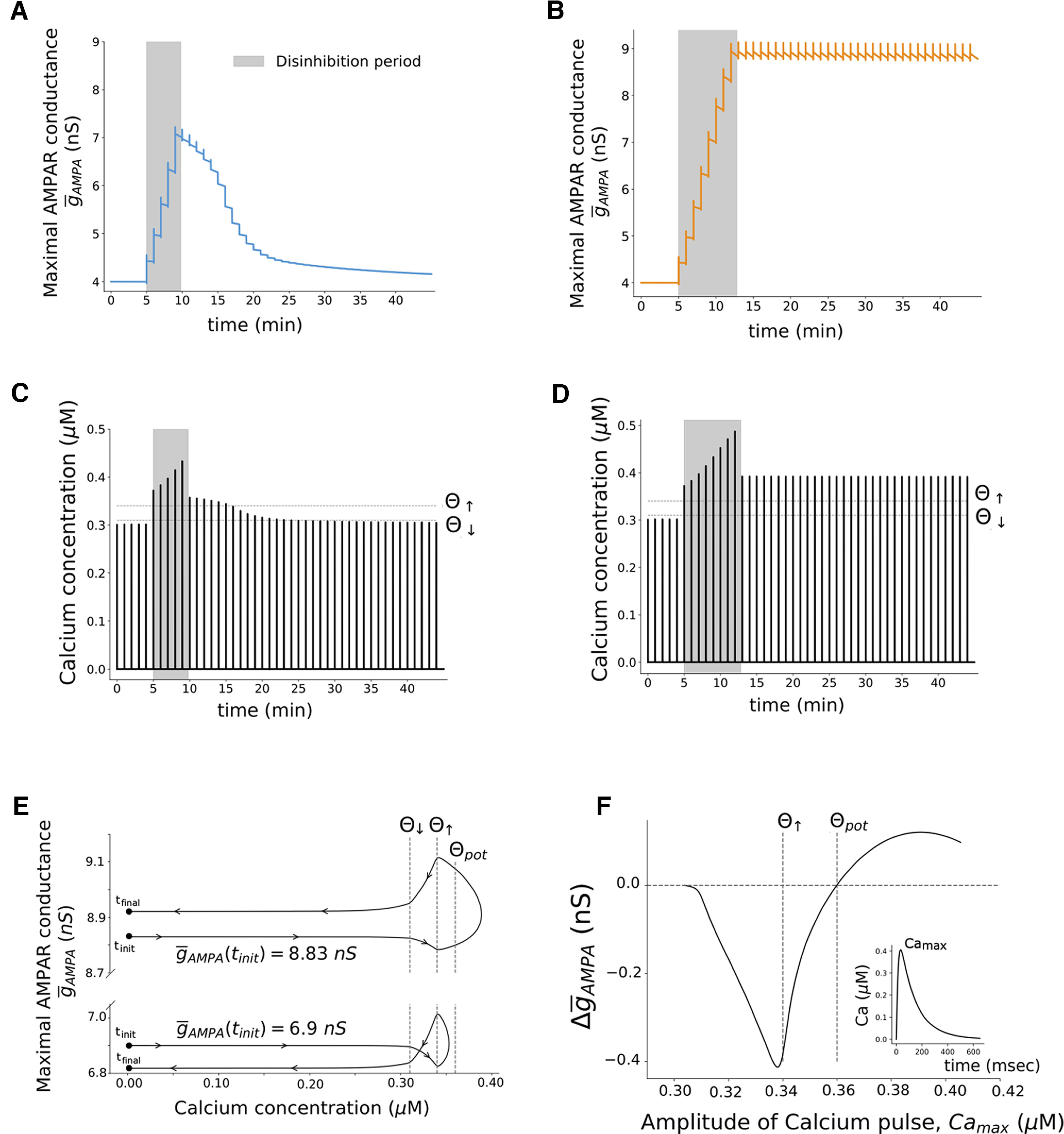

Figure 5.

Calcium dynamic is key for the induction of synaptic plasticity. A, Time course of maximal AMPAR conductance, AMPA, when the dendritic compartment is disinhibited for a short period (from t = 5 min to t = 10 min). The maximal AMPAR conductance increases from its initial value AMPA = 4 nS to AMPA = 6.9 nS during the disinhibition period (gray area). B, Time course of AMPA when the dendritic compartment is disinhibited for a long period (from t = 5 min to t = 13 min). It increases from AMPA = 4 nS to AMPA = 8.83 nS during the disinhibition period. Changes in the AMPAR conductance, AMPA, are described by Equation 22. C, Time course of intracellular calcium concentration when ED is disinhibited for a short period (from t = 5 min to t = 10 min), where θ↓ is the depression onset, and θ↑ is the potentiation onset. D, Time course of intracellular calcium concentration when the dendritic compartment is disinhibited for a long period (from t = 5 min to t = 13 min). The calcium dynamics is described by Equation 25 (see Materials and Methods). E, Trajectories of the system in the AMPA–Ca plane when a pulse of glutamate is paired with a pulse of GABA for AMPA = 6.9 nS and AMPA = 8.83 nS, where θpot is the potentiation threshold as defined in the Results section. F, Changes in the maximal AMPAR conductance, Δ AMPA, as a function of the amplitude of intracellular calcium pulse, Camax. Each point of the graph was obtained by submitting ED to a glutamate pulse for different initial values of AMPA. This induced different depolarization levels and, consequently, different activation levels of NMDARs and calcium pulses of different amplitudes.

In this study, we focused on a calcium-based synaptic plasticity model to describe changes in the excitatory SC–CA1 synapse. To gain a more detailed understanding on how the evolution of the calcium levels relate to the changes in the synaptic strengths, we can examine the calcium dynamics before, during, and after the disinhibition period.

Figure 5, C and D, shows that the calcium concentration increases significantly during the disinhibition period, crossing the potentiation onset θ↑ with a significant margin. Immediately after the end of the disinhibition period, the calcium levels decrease, yet they remain above θ↑. We can see a clear difference in calcium dynamics for the short and the long disinhibition periods. In the case of a short disinhibition period, each pairing of GABA and glutamate after the disinhibition period will elicit a calcium pulse with a smaller amplitude than the previous one. Eventually, at t = 25 min, the calcium concentration from the pairing is not enough to cross the potentiation onset θ↑. By t = 30 min, calcium does not cross either the potentiation (θ↑) or the depression onset (θ↓), having a similar amplitude as before the disinhibition period. In the case of a long disinhibition period, each pairing performed after the disinhibition period evokes a calcium pulse with a constant amplitude. In other words, long disinhibition periods ensure that the consequent pairings yield calcium responses that do not drop below the onset thresholds.

To better visualize the synaptic and calcium dynamics immediately after the disinhibition period in both cases, we plot the trajectory of the system in the Ca- AMPA plane. We do so for AMPA(tinit) = 6.9 nS and for AMPA(tinit) = 8.83 nS, which are the values of AMPA at the end of the disinhibition period for the short and long disinhibition durations (Fig. 5E). For AMPA(tinit) = 6.9 nS, the calcium concentration crosses the potentiation onset θ↑ (Camax = 0.353 μm), but there is a decrease of< AMPA from 6.9 to 6.8 nS. For AMPA(tinit) = 8.83 nS, the calcium concentration crosses θ↑ to a larger extent (Camax = 0.389 μm) and there is an increase of AMPA from 8.83 to 8.92 nS. These results suggest that it is necessary but not sufficient for calcium concentration to cross the potentiation onset to induce potentiation. To verify this, we looked at changes in maximal conductance of the postsynaptic AMPAR (Δ AMPA), as a function of the amplitude of the intracellular calcium (Camax). From Figure 5F, we see that as Camax increases we only start to have potentiation (Δ AMPA > 0) when Camax crosses not the potentiation onset θ↑, but a higher level, which we term as the potentiation threshold θpot, 0.36 μm.

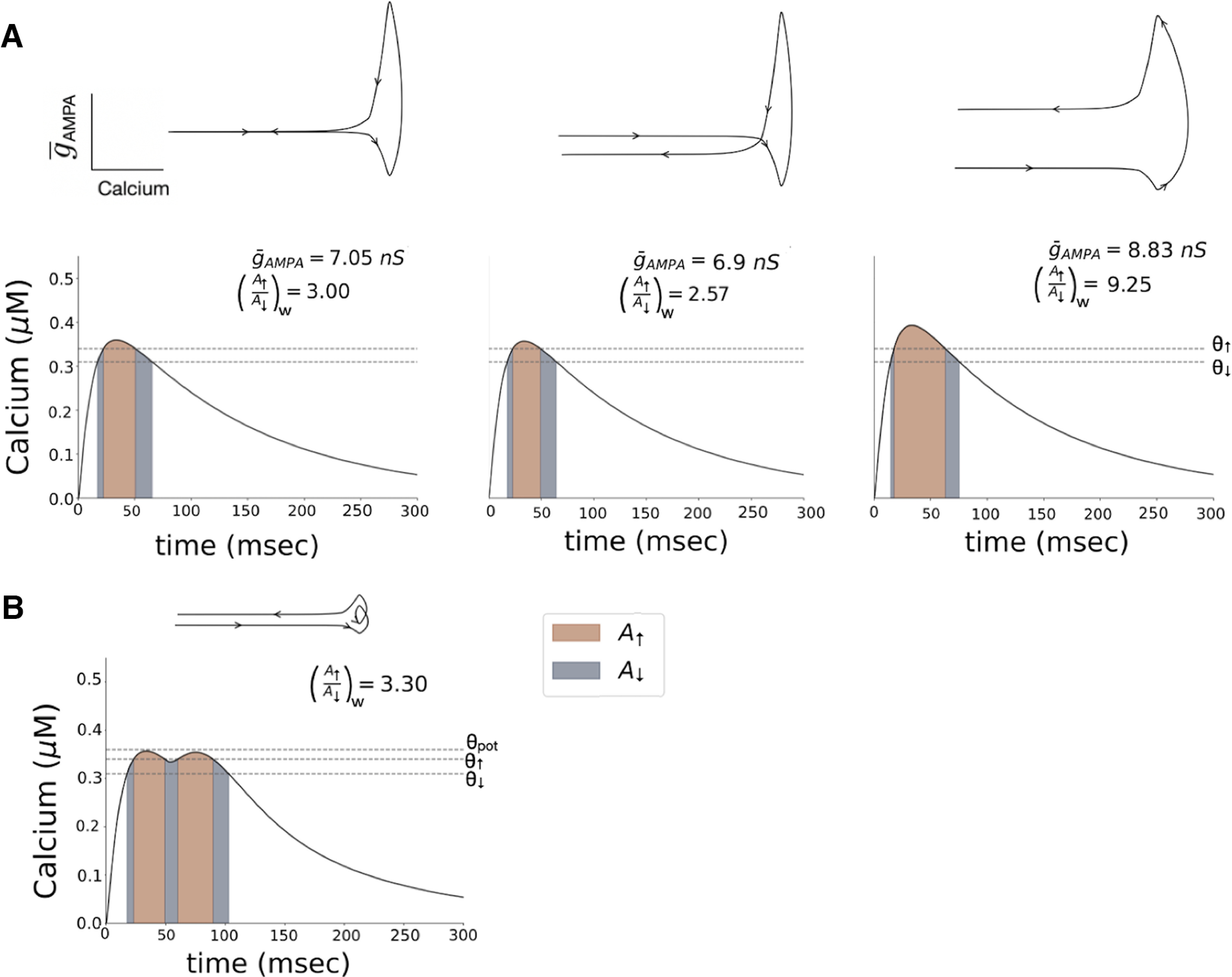

We do note that the fixed potential threshold θpot is not an ideal indicator of potentiation, as it may need to be recalculated depending on a specific case of calcium dynamics timescales and/or the induction protocol. As seen in Figure 5E, the dynamics of calcium is important in the induction of plasticity. Therefore, changing these by, for example, changing the calcium decay rate, can alter the θpot by changing the time calcium spends in the depression/potentiation onset region. This kind of analysis can also fail to identify mechanisms of the induction of potentiation. As shown in Figure 6B, if we consider a second calcium source that becomes activated at t = 80 ms, neither of the two pulses of calcium generated crosses θpot; however, the synapse is potentiated. These examples suggest that it is not the peak calcium concentration that is a key indicator of potentiation, but a measure that is based on the total amount of calcium that exceeds the onset levels. We suggest that a better quantity that can be used more generally as an indicator of plasticity is the ratio between the integral of calcium when its concentration is above the potentiation onset θ↑, which we will call the area of AMPAR insertion (Extended Data Fig. 6-1, orange area, Fig. 6, corresponding graphs) and the integral of calcium when its concentration is above the depression onset θ↓ and below the potentiation onset θ↑, the area of AMPAR removal (Extended Data Fig. 6-1, gray area, Fig. 6, corresponding graphs) weighted by the calcium-dependent learning rate η, which we named (A↑/A↓)w (for more details, see Materials and Methods). If this ratio is<3.0, depression is induced in our model; if the ratio is >3.0, potentiation is induced.

Figure 6.

The weighted ratio (A↑/A↓)w can accurately be used as a predictor of induction of depression or potentiation. The depression and potentiation areas A↓ and A↑ are as defined in Extended Data Figure 6-1. A, Different values of AMPA evoke different levels of depolarization and, consequently, different intracellular calcium concentrations. For a weighted ratio between the calcium area of AMPAR insertion and removal at<3.00, depression is induced. For a value >3.00, potentiation is induced. B, By adding a second source of calcium that becomes activated at t = 80 ms, it is possible to have situations where the calcium never crosses the potentiation threshold θpot but potentiation is induced. The (A↑/A↓)w accurately identifies these cases as potentiation. In these numerical simulations, ED receives a pulse of glutamate followed by a pulse of GABA 2 ms after, each with an amplitude of 1 mm and a duration of 1 ms.

Area of potentiation (orange) and area of depression (gray) considered to calculate the (A↑/A↓)w. For the description of the labels, please refer to Figure 6 in the main text. From t0 to t1 and t2 to t3, calcium is above θ↓ and below θ↑. These regions constitute the area of depression A↓. From t1 to t2, calcium is above θ↑. This region constitutes the area of potentiation A↑. While the calcium concentration is above the depression onset θ↓ (but below the potentiation onset θ↑), the maximal conductance of the AMPARs AMPA is decreasing. On the other hand, when the calcium concentration is above θ↑,< AMPA is increasing. The induction of plasticity at the excitatory synapse depends on the net result of these changes of AMPA. The more time calcium spends above θ↑/θ↓, the more likely it is that potentiation/depression is induced at the synapse. Furthermore, the more time calcium spends above θ↑/θ↓, the bigger the area underneath the calcium curve in this region of insertion/removal of AMPARs. Therefore, the ratio between the area of insertion and the area of removal (A↑/A↓) can be used as a measure of induction of plasticity (Fig. 6, main text). There is an optimal ratio for which the decrease of AMPA resultant from time spent in the removal region and the increase of AMPA resultant from time spent in the insertion region will cancel each other and no plasticity is induced. If the ratio A↑/A↓ is below this value, depression is induced; if the ratio is above this value, potentiation is induced. The ratio A↑/A↓ is given by . Because the decrease and increase of AMPA is not the same in the whole removal and insertion region, we need to calculate the calcium integral weighted by the calcium-dependent learning rate η. The (A↑/A↓)w is then given by . To calculate (A↑/A↓)w, we use the trapezoidal rule to perform numerical integration of the potentiation and depression area. Download Figure 6-1, TIF file (2.2MB, tif) .

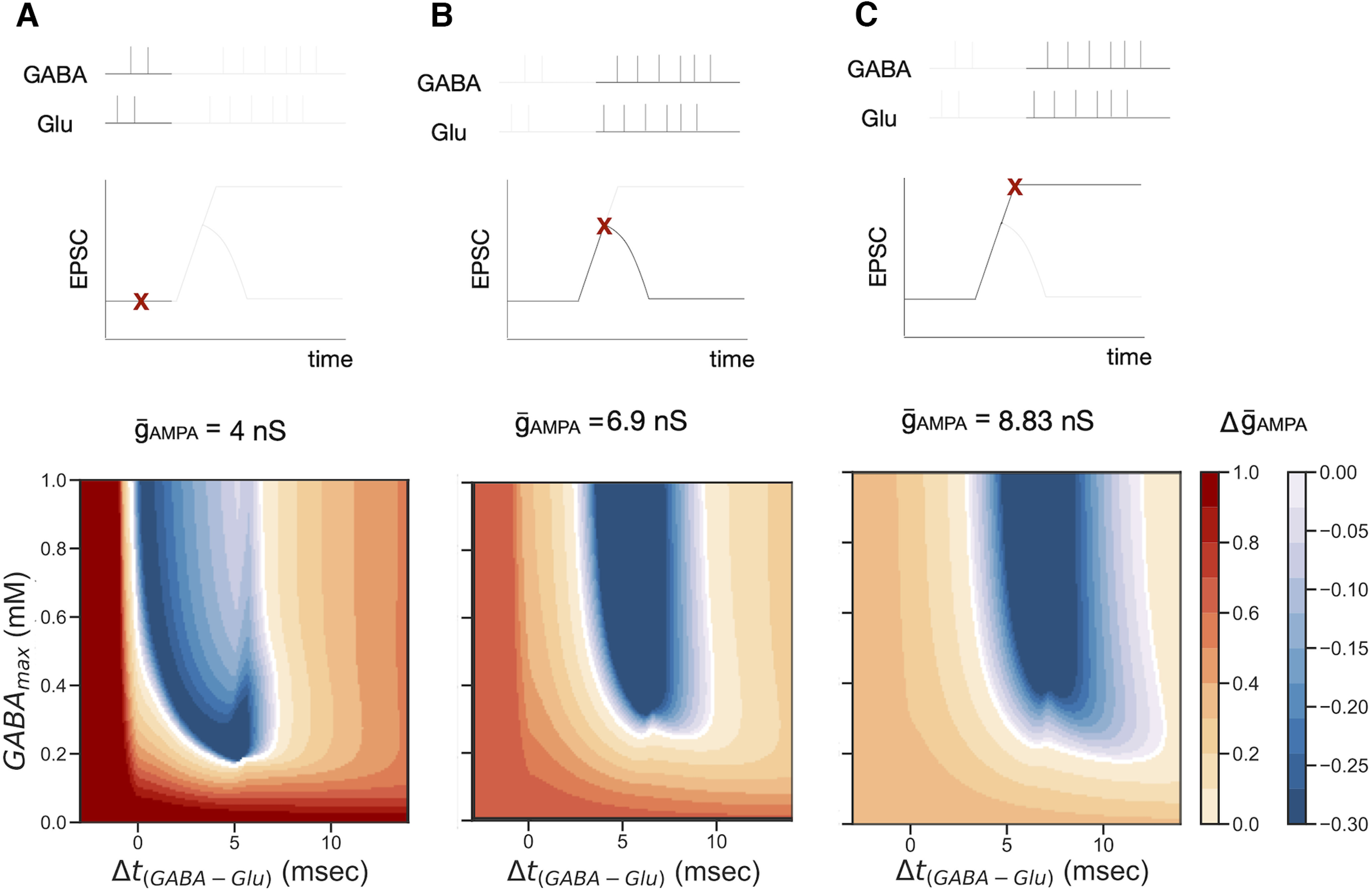

GABA amplitude and Glu–GABA pairing timing control membrane potential

Disinhibition of the pyramidal cell (i.e., reduction of GABAergic inputs), can facilitate the depolarization of the cell, which can control plasticity, as we have shown in the previous section. Therefore, we hypothesize that the amplitude of the GABA pulse, GABAmax, and the relative time between the glutamate and GABA pulses, Δt(GABA-Glu), can modulate plasticity. To explore this hypothesis, we pair glutamatergic inputs with GABAergic inputs into ED. We vary the relative time between the inputs, Δt(GABA-Glu), and the amplitude of the GABAergic inputs, GABAmax, to measure changes induced in AMPA. Simulations were repeated for different values of to understand why pulses of glutamate and GABA with the same characteristics (same amplitude and same duration) have different outcomes when administered after the short or long disinhibition periods. Simulations were performed with three initial values of : = 4 nS, = 6.9 nS, and = 8.83 nS. We identified well defined regions of potentiation and depression in the Δt(GABA-Glu)–GABAmax parameter space (Fig. 7). We also saw that the regions change with the value of AMPA. More specifically, the depression region moves toward the right of the plot as AMPA increases. In other words, as AMPA increases, the GABAergic inputs need to arrive with a longer delay relative to the glutamatergic inputs to induce depression. It is important to note that the level of potentiation or depression induced also changes as we increase AMPA. Generally, the magnitude of potentiation decreases, and the magnitude of depression increases. This is because the system saturates as AMPA increases (i.e., AMPA cannot increase indefinitely). This is a restriction imposed by the model. These results suggest that the same induction protocol may induce either potentiation or depression more or less efficiently, depending on the current phosphorylation state of the AMPA receptors (i.e., AMPA), and on the decrease of GABA during disinhibition. In other words, the net effect of a pairing protocol is state dependent.

Figure 7.

Amplitude of GABA pulse, GABAmax, and relative time between GABA and glutamate pulses, Δt(GABA−Glu), control the direction and efficiency of the induction of synaptic plasticity. A, Depression and potentiation regions for AMPA = 4 nS. This is the maximal conductance value of the AMPAR used in our simulations before the disinhibition period starts. B, Depression and potentiation regions for AMPA = 6.9 nS, which represents the state of phosphorylation of the AMPAR at the end of the short disinhibition period. C, Depression and potentiation regions for AMPA = 8.83 nS, which is the state of phosphorylation of the AMPAR at the end of the long disinhibition period. For each plot in A, B, and C, we pair one pulse of glutamate (with a concentration of 1 mm and 1 ms of duration) with one pulse of GABA with a duration of 1 ms and varying concentrations and initial time, and measure the resultant change in AMPA for each case.

Model predictions and implications

Results of model simulations and analysis make several testable predictions. First, while experiments so far have not identified precisely the exact type of s.o. interneurons that provide the feedforward inhibition to the CA1 pyramidal cell, our model predicts that it should be an interneuron type with fast dynamics (i.e., with dynamics comparable to the pyramidal cells). More specifically, we expect that EPSC on the hippocampal parvalbumin (PV)-positive interneurons in the stratum radiatum would decrease during cholinergic pairing because of the inhibition provided by the OLM neurons. Consequently, GABAA-mediated IPSCs on the proximal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells would also decrease.

In this work (both in modeling and experimentally), modulation of the OLM cells is because of cholinergic activation of α7 nAChRs. Our model more specifically suggests that the GABA release by the OLM cells is regulated by activating α7 nACh receptors, without necessarily altering the OLM firing. However, GABA release can also be controlled by the depolarization of the OLM cells and/or by modulation of their spiking activity by somatic nAChRs.

Our model predicts a relationship between the relative timing of the septal and hippocampal stimulus pairing and the synaptic plasticity direction at the SC–PYR synapse. According to our simulations, increasing the frequency of septal and hippocampal paired stimulation can induce plasticity more efficiently (i.e., fewer pairings would be required to induce LTP). At the same time, we predict that changing the relative time between septal and hippocampal activation can induce long-term depression instead of LTP.

Finally, our modeling results suggest that for the plasticity to be induced, the excitatory NMDA and AMPA receptors and the inhibitory GABAA receptors should be located sufficiently proximal to each other in the pyramidal dendritic compartment.

Discussion