Abstract

Current expert recommendations suggest anal cytology followed by high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) for biopsy and histological confirmation may be beneficial in cancer prevention, especially in people living with HIV (PLWH). Guided by the social ecological model, the purpose of this study was to examine sociodemographic and clinical variables, individual-level factors (depression, HIV/AIDS-related stigma, and health beliefs) and interpersonal-level factors (social support) related to time to HRA follow-up after abnormal anal cytology. We enrolled 150 PLWH from a large HIV community clinic, with on-site HRA availability, in Atlanta, GA. The median age was 46 years (interquartile range of 37–52), 78.5% identified as African American/Black, and 88.6% identified as born male. The average length of follow-up to HRA after abnormal anal cytology was 380.6 days (standard deviation = 317.23). Only 24.3% (n = 39) of the sample had an HRA within 6 months after an abnormal anal cytology, whereas 57% of the sample had an HRA within 12 months. HIV/AIDS-related stigma [odds ratio (OR) 0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33–0.90] and health motivation (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67–0.95) were associated with time to HRA follow-up ≤6 months. For HRA follow-up ≤12 months, we found anal cytology [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions/atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cannot exclude HSIL (HSIL/ASCUS-H) vs. low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.00–0.70; atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) vs. LSIL OR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.02–0.64] and health motivation (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.65–0.99) were associated. Findings from this study can inform strategies to improve follow-up care after abnormal anal cytology at an individual and interpersonal level in efforts to decrease anal cancer morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: anal cytology, high-resolution anoscopy, anal cancer, stigma, health education

Introduction

Owing to the advancements in treatment and an aging HIV population, people living with HIV (PLWH) are less likely to die from opportunistic infections but now face a growing problem of non-AIDS defining cancers, particularly human papillomavirus (HPV)-related anal cancer.1 HPV-related anal cancer occurs in excess rates in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. The general incidence of anal cancer in the HIV population is 35 per 100,000 and this trend has been increasing over the years in this population.2–4 HIV-infected men and women are 28 times more likely to be diagnosed with anal cancer than the general population.5,6 Further, the incidence of anal cancer occurs in remarkable excess particularly in men who have sex with men (MSM), who experience up to 40-fold increase in risk.6–8

Persistent HPV infection is a significant cause of anal precancerous lesions and 90% of anal cancer cases in PLWH.9–11 Similar to the cervix, the anal canal has a transformation zone, which is vulnerable to the development of precancerous lesions from HPV infection.12,13 Analogous to cervical cancer screening, anal cytology involves collecting cells from the anal canal for cytological examination. Abnormal anal cytology, regardless of grade, is recommended to be followed up by high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and biopsy of suspected precancerous lesions for histological confirmation.14

Although the efficacy of treating high-grade dysplasia is currently under investigation Anal Cancer HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) study,15 NCT 02135419), HRA is important in identifying areas that require treatment in efforts to prevent progression to anal cancer. Further, a longitudinal study of HIV-positive MSMs reported an association with anogenital warts and high-grade anal dysplasia, thus suggesting HRA may be beneficial for management and surveillance for PLWH presenting with low-risk HPV-associated anal warts.16

Although no formal anal cancer screening program has been established for individuals living with HIV, national expert recommendations available suggest anal cancer screening with anal cytology and HRA for biopsy and confirmation may be beneficial in cancer prevention, especially in high-risk groups such as HIV-positive MSM and women with a history of cervical or vulvar dysplasia.9,17,18 Further, the primary argument in favor of anal cancer screening is the biological similarities between anal and cervical cancer where similar screening procedures for anal dysplasia have the potential to decrease mortality and morbidity as seen with cervical cancer.

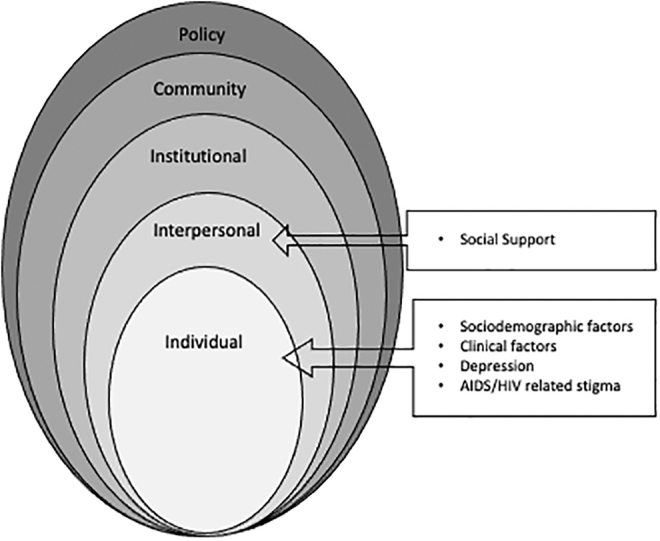

Even without conclusive evidence of its efficacy, many clinics have implemented screening programs for anal cancer to help reduce the increasing clinical and personal burden of anal cancer in PLWH.19–22 Guided by the social ecological model, the purpose of this study was to examine sociodemographic and clinical variables, individual-level factors (depression, HIV/AIDS-related stigma, and health beliefs) and interpersonal-level factors (social support) related to HRA follow-up care after abnormal anal cytology (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Social ecological model for health decisions.

Methods

Study sample

The study received institutional review board approval at Emory University and from the recruitment site's research oversight committee. A descriptive cross-sectional design of a convenience sample of 150 men and women living with HIV were recruited from a large HIV community clinic in Atlanta, GA. This clinic is a comprehensive HIV clinic that performs anal cytology with an on-site anoscopy clinic where HRA with biopsies are available and provided at the clinic for HIV-positive men and women. This service is covered once an individual is eligible and enrolls in the Infectious Disease Program (IDP). The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) HIV-positive men and women enrolled and managed at the study clinic; (2) a documented abnormal anal Pap test during the study period; (3) 21 years or older; (4) able to read, write, and understand English; and (5) lives within metropolitan Atlanta city limits.

Study procedures

Potential participants were identified by the principal investigator (PI), while following all HIPPA guidelines, by pre-screening medical records of those referred to the anoscopy clinic after documented abnormal anal cytology. Potential participants who were within the study's inclusion criteria were approached at their clinic visit. In a private interview room or private area in the clinic, the PI or trained research coordinator described the purpose of the study, what participation entails, and the risks/benefits of participating in the study. Informed consent was obtained before enrollment into the study. Data were collected at one time point by patient self-report on pencil and paper questionnaires administered by the PI and/or trained research assistants and through a medical chart review. A $25 gift card was provided to participants after completion of study measures.

Main outcome variable

Follow-up after an abnormal anal cytology was assessed through scrutiny of medical records. Using the same time to threshold for colposcopy follow-up in a sample of HIV-positive women by Cejtin et al.,23 we examined follow-up anoscopy within 6 months after an abnormal anal cytology. In addition, expert recommendations include follow-up to occur 6–12 months after abnormal anal cytology in high-risk groups.18 Thus, we also examined HRA follow-up within 12 months after abnormal anal cytology.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables

A demographic and clinical measure was compiled by the PI to collect sociodemographic variables that included self-reported age, race/ethnicity, education, marital or partner status, income, housing status, smoking status, sexual orientation, sexual behaviors, employment, and type of health insurance. A medical chart review was performed to abstract nadir CD4+ count, most recent documented anal cytology results, date of the most recent anal cytology that occurred during the study time period, and date of most recent HRA/biopsy that occurred after the documented abnormal cytology, and most recent CD4+ count that occurred during the study period.

Anal cytology was abstracted from medical charts and classified using the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) as follows: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL); high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS); ASCUS cannot exclude HSIL (ASCUS-H). Regardless of grade, all abnormal anal cytology is recommended to be followed up by HRA and biopsy of the lesion.14 Patients with an abnormal anal cytology and a referral to the anoscopy clinic were commonly scheduled for a HRA and biopsy performed at the clinic by a trained and certified physician.

Individual-level factors

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale assessed depression. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report scale designed to survey mood, somatic complaints, interactions with others, and motor function. The CES-D is not a diagnostic tool and is only a measure of depressive symptomology where a score equals or is greater than 16 is indicative of positive symptomology over the past week. The instrument has support for its construct validity and internal consistency estimates ranging from 0.8 to 0.9.24

The Champion Health Belief Model Scale was adapted and psychometrically tested to measure health beliefs concerning anal cancer. This health belief model scale measures five subscales of perceived susceptibility to anal cancer, seriousness of anal cancer, perceived benefits of HRA follow-up, and perceived barriers to HRA follow-up, and general motivation for follow-up. Each statement is rated “strongly agree” (5) to “strongly disagree” (1). Score ranges for the susceptibility subscale is 6–30, the seriousness subscale is 12–60, perceived benefits subscale is 5–25, perceived barriers subscale 8–40, and health motivation subscale is 8–40. The responses result in a summative score for each subscale where a higher score is indicative of higher levels of that perception. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients for subscales range from 0.80 to 0.93.25

The Internalized HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma Scale is a 6-item instrument that assess self-defacing beliefs and negative perceptions of people living with HIV/AIDS. Each item is rated dichotomously with “agree” (1) or “disagree” (0). The sum total of the scale is a score that ranges from 0 to 6 with higher scores signifying greater internalized stigma. The scale has been tested in individuals living with HIV/AIDS is South Africa, Swaziland, and Atlanta, GA, and has shown good internal reliability (overall alpha coefficient = 0.75) and criterion validity.26

Interpersonal-level factors

The general Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) is a 20-item multi-dimensional survey that measures the functional aspects of perceived social support. The survey is divided into four subscales measuring perceived adequacy of tangible support, informational and emotional support, positive social interaction, and affectionate support. Responses for each item is on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) “none of the time” to (5) “all of the time.” A total score ranges from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better perceived social support. Cronbach's alpha was reported to be 0.97 for the overall scale and subscales ranged from 0.91 to 0.96.27

Data analysis

Characteristics of the cohort are described using median, quartile one, and quartile three for continuous measures and count and percentage for categorical characteristics. The association of individual and interpersonal factors on adherence status was examined through chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical characteristics and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous characteristics. Multi-variable logistic regression models assessed factors associated with HRA follow-up after abnormal anal cytology within 6 months and within 12 months. A priori factors considered for inclusion in multi-variable models were as follows: Internalized HIV/AIDS-related stigma score, social support (total score), perceptions of health beliefs (susceptibility, seriousness, benefits, barriers, and health motivation subscores), abnormal anal cytology (HSIL/ASCUS-H, LSIL, and ASCUS), depressive symptoms (yes, no), smoked cigarettes (yes, former smoker, and never smoked), viral suppression, and CD4+ count.

Owing to poor model fit, depressive symptoms, smoked cigarettes, and viral suppression were dropped from the model. Model fit was assessed by Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test as well as c-statistic. Model-based estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. Significance was set at α = 0.05 for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.4 and SPSS version 27.

Results

Univariate analysis

We enrolled 150 participants, with one participant who did not complete study questionnaires at enrollment and was lost to follow-up. The median age of the sample (n = 149) was 46 years with an interquartile range of 37–52, majority of the sample (78.5%) identified as African American/Black, and 88.6% identified as born male. Approximately 48% of the sample are current or former smokers. The median CD4+ count was 392 mm3 with an interquartile range of 259–556 mm3. Only 20% of the sample reported history of anal receptive intercourse (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cohort and by Time to High-Resolution Anoscopy After Abnormal Anal Cytology

| Overall (N = 149) |

HRA ≤ 6 months (n = 39) |

HRA >6 months (n = 110) |

p a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Sociodemographic characteristic | ||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| African American/Black | 117 | 78.5 | 29 | 76.3 | 87 | 79.1 | 0.73 | |||

| Caucasian/White | 24 | 16.1 | 6 | 15.8 | 18 | 16.4 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino/other | 8 | 5.4 | 3 | 7.9 | 5 | 4.5 | ||||

| Sex at birth | ||||||||||

| Born male | 133 | 88.6 | 35 | 89.7 | 96 | 88.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Born female | 17 | 11.4 | 4 | 10.3 | 13 | 11.9 | ||||

| Average monthly gross household income (all sources) | ||||||||||

| ≤$1000 | 54 | 36.0 | 15 | 38.5 | 39 | 35.5 | 0.99b | |||

| $1001–2500 | 71 | 47.3 | 18 | 46.2 | 53 | 48.2 | ||||

| $2501–6250 | 21 | 14.0 | 5 | 12.8 | 15 | 13.6 | ||||

| >$6250 | 4 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.7 | ||||

| Housing status | ||||||||||

| Own home/apartment | 100 | 66.7 | 27 | 69.2 | 72 | 65.5 | 0.90 | |||

| Someone else's home/apartment/shelter | 41 | 27.3 | 10 | 25.6 | 31 | 28.2 | ||||

| Homeless, correctional, or treatment facility | 9 | 6.0 | 2 | 5.1 | 7 | 6.4 | ||||

| Highest grade of school completed | ||||||||||

| High school diploma | 21 | 14.1 | 5 | 12.8 | 16 | 14.7 | 0.98 | |||

| High school diploma/GED | 95 | 63.8 | 25 | 64.1 | 70 | 64.2 | ||||

| Attended/completed college | 20 | 13.4 | 5 | 12.8 | 14 | 12.8 | ||||

| Attended/completed graduate school | 13 | 8.7 | 4 | 10.3 | 9 | 8.3 | ||||

| Currently employed (full or part time) | ||||||||||

| No | 64 | 43.0 | 21 | 53.8 | 43 | 39.4 | 0.12 | |||

| Yes | 85 | 57.1 | 18 | 46.2 | 66 | 60.6 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single/never married | 106 | 71.6 | 28 | 71.8 | 77 | 71.3 | 0.99 | |||

| Marred/living together | 27 | 18.2 | 7 | 17.9 | 20 | 18.5 | ||||

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 15 | 10.1 | 4 | 10.3 | 11 | 10.2 | ||||

| Smoked cigarettes within past 12 months | ||||||||||

| Yes | 43 | 29.7 | 12 | 32.4 | 31 | 29.0 | 0.41 | |||

| No, former smoker | 26 | 17.9 | 4 | 10.8 | 22 | 20.6 | ||||

| No, never smoked | 76 | 52.4 | 21 | 56.8 | 54 | 50.5 | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||||

| Heterosexual/straight | 21 | 14.4 | 4 | 10.3 | 16 | 15.1 | 0.75 | |||

| Bisexual/other | 26 | 17.8 | 7 | 17.9 | 19 | 17.9 | ||||

| Lesbian/gay | 99 | 67.8 | 28 | 71.8 | 71 | 67.0 | ||||

| Health insurance | ||||||||||

| Government (any) | 68 | 45.3 | 19 | 48.7 | 49 | 44.6 | 0.92 | |||

| No coverage/self-pay | 35 | 23.3 | 9 | 23.1 | 26 | 23.6 | ||||

| Other | 22 | 14.7 | 6 | 15.4 | 16 | 14.6 | ||||

| Private health insurance | 25 | 16.7 | 5 | 12.8 | 19 | 17.3 | ||||

| Clinical characteristic | ||||||||||

| Engage in receptive anal intercourse? | ||||||||||

| No | 116 | 80.1 | 29 | 76.3 | 87 | 81.3 | 0.51 | |||

| Yes | 29 | 19.9 | 9 | 23.7 | 20 | 18.7 | ||||

| Viral suppression (undetectable or <200 copies/mL) | ||||||||||

| No | 8 | 12.1 | 2 | 8.3 | 6 | 14.3 | 0.70 | |||

| Yes | 58 | 87.9 | 22 | 91.7 | 36 | 85.7 | ||||

| Abnormal anal cytology results | ||||||||||

| LSIL | 66 | 44.6 | 17 | 43.6 | 49 | 45 | 0.72 | |||

| HSIL/ASCUS-H | 20 | 13.5 | 4 | 10.3 | 16 | 14.7 | ||||

| ASCUS | 62 | 41.9 | 18 | 46.2 | 44 | 40.4 | ||||

| Overall (n = 149) |

HRA ≤ 6 months (n = 39) |

HRA >6 months (n = 110) |

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | p c | |

| Age, years |

46 |

37 |

52 |

47 |

36 |

51 |

45 |

37 |

53 |

0.96 |

| CD4+ count |

392 |

259 |

566 |

387 |

258 |

551.5 |

392 |

276 |

576 |

0.87 |

| CD4+ nadir | 147.5 | 50 | 310 | 106 | 45 | 175 | 199 | 58.5 | 407.5 | 0.05 |

Chi-square test unless otherwise noted.

Fisher's exact test.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASCUS-H, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cannot exclude HSIL; HRA, high-resolution anoscopy; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions.

For abnormal anal cytology, we found 43.4% of the sample had LSIL, 5.9% had HSIL, 40.8% was ASCUS, 7.9% ASCUS, ASCUS-H. The average length of follow-up after an abnormal anal cytology to HRA was 380.6 days (standard deviation = 317.23). Only 24.3% (n = 39) of the sample had an HRA within 6 months after a documented abnormal anal cytology, whereas 57% of the sample had an HRA within 12 months of a documented abnormal anal cytology. Demographic characteristics did not differ by time to follow-up (i.e., ≤6 months vs. >6 months; see Table 1).

The median CES-D score was 12 with an interquartile range of 6–20 with 39% of the sample reporting positive symptomology (scores ≥16). The median AIDS-related stigma score was 2 with an interquartile range 0–3. The total social support score for the sample was 77.6 with an interquartile range of 56.7–94.7. Individual-level and interpersonal-level factors are described in Table 2 and did not differ by time to HRA follow-up.

Table 2.

Individual-Level and Interpersonal-Level Characteristics by Time to High-Resolution Anoscopy After Abnormal Anal Cytology

| Overall (n = 149) |

HRA ≤ 6 months (n = 39) |

HRA >6 months (n = 110) |

p a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| Individual level | ||||||||||

| CES-D scoreb | 12 | 6 | 20 | 13.5 | 6.5 | 24.5 | 12 | 6 | 20 | 0.82 |

| Health beliefsc | ||||||||||

| Perceived susceptibility | 15 | 10 | 19 | 15 | 11 | 19 | 16 | 10 | 19 | 0.94 |

| Perceived barriers | 20 | 14 | 24 | 19 | 17 | 23 | 20 | 13 | 24 | 0.73 |

| Perceived benefits | 21 | 18 | 24 | 20.5 | 18 | 24 | 21 | 18 | 24 | 0.99 |

| Perceived seriousness | 36 | 30 | 42 | 36 | 30.5 | 43.5 | 37 | 30 | 41 | 0.69 |

| Health motivation | 30.5 | 26 | 34 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 34 | 30 | 26 | 34 | 0.88 |

| HIV/AIDS-related stigma scored | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||

| Social support subscorese | ||||||||||

| Emotional/information | 78.1 | 59.4 | 100 | 78.1 | 56.3 | 100 | 76.6 | 59.4 | 96.9 | 0.88 |

| Positive interaction | 83.3 | 54.2 | 100 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 100 | 83.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 0.14 |

| Affection | 83.3 | 58.3 | 100 | 75.0 | 58.3 | 100 | 83.3 | 58.3 | 100 | 0.18 |

| Tangible | 75.0 | 43.8 | 93.8 | 81.3 | 56.3 | 87.5 | 75.0 | 43.8 | 93.8 | 0.86 |

| Total score | 77.6 | 56.6 | 94.7 | 73.0 | 56.6 | 94.7 | 77.6 | 55.3 | 94.7 | 0.40 |

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

CES-D Scale: Scores range from 0 to 60 where positive depressive symptomology is indicative at scores ≥16.

Health beliefs measured by the Champion Health Belief Model Scale. Score ranges for the susceptibility subscale is 6–30, the seriousness subscale is 12–60, perceived benefits subscale is 5–25, perceived barriers subscale 8–40, and health motivation subscale is 8–40. Higher score = higher levels of that perception.

AIDS-related stigma scale ranges from 0 to 6 with higher scores = greater internalized stigma.

Social support measured by the MOS Social Support Survey. Total score ranges from 0 to 100 where higher scores = greater support.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; HRA, high-resolution anoscopy; MOS, Medical Outcomes Study.

Multi-variate analysis

In multi-variate analysis, HIV/AIDS-related stigma (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.33–0.90) and health motivation (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67–0.95) were associated with time to HRA follow-up ≤6 months (Table 3). Specifically, participants with increased HIV/AIDS related stigma were associated with an 46% lower likelihood of receiving HRA within 6 months (p = 0.02). In addition, general perceived health motivation was associated with a 20% lower likelihood of follow-up with HRA within 6 months (p = 0.01).

Table 3.

Multi-Variable Logistic Regression Assessing Characteristics Associated with Follow-Up with High-Resolution Anoscopy ≤6 Months

| Effect | OR | 95% CI LB | 95% CI UB | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS-related stigma | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.02* |

| CD4+ count | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.18 |

| Social support (total score) | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 0.07 |

| Perceived susceptibility to anal cancer | 0.95 | 0.84 | 1.09 | 0.47 |

| Health motivation | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.01* |

| Perceived barriers to follow-up | 1.13 | 0.97 | 1.30 | 0.11 |

| Perceived benefits of anal cytology | 1.16 | 0.99 | 1.36 | 0.06 |

| Perceived seriousness of anal cancer | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.15 | 0.33 |

| Anal cytology results HSIL/ASCUS-H vs. LSIL | 0.63 | 0.04 | 10.90 | 0.15 |

| Anal cytology results ASCUS vs. LSIL | 0.20 | 0.04 | 1.04 |

p < 0.05.

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASCUS-H, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cannot exclude HSIL; CI, confidence interval; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; LB, lower bound; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; OR, odds ratio; UB, upper bound.

Subanalysis to follow-up HRA ≤12 months

In multi-variable analysis with the outcome variable as HRA follow-up ≤12 months, we found anal cytology (HSIL/ASCUS-H vs. LSIL OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.00–0.70; ASCUS vs. LSIL OR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.02–0.64) and health motivation (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.65–0.99) were associated with time to HRA follow-up within 12 months (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multi-Variable Logistic Regression Assessing Characteristics Associated with Follow-Up with High-Resolution Anoscopy ≤ 12 Months

| Effect | OR | 95% CI LB | 95% CI UB | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS-related stigma | 0.85 | 0.55 | 1.31 | 0.99 |

| CD4+ count | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.45 |

| Social support (total score) | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 0.97 |

| Perceived susceptibility to anal cancer | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.23 | 0.09 |

| Health motivation | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.04* |

| Perceived barriers to follow-up | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.16 | 0.74 |

| Perceived benefits of anal cytology | 1.04 | 0.90 | 1.20 | 0.61 |

| Perceived seriousness of anal cancer | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.78 |

| Anal cytology results HSIL/ASCUS-H vs. LSIL | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.02* |

| Anal cytology results ASCUS vs. LSIL | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.64 |

p < 0.05.

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASCUS-H, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cannot exclude HSIL; CI, confidence interval; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study examined individual and interpersonal factors associated with follow-up with HRA after abnormal anal cytology in PLWH. To date, no study has examined follow-up behaviors for HIV-positive men and women at risk for anal cancer. As seen with cervical cancer, anal cancer screening can be beneficial for capturing anal precancerous lesions early; thus, subsequent follow-up with HRA and biopsy for detection of precancerous lesions is important for an effective cancer prevention plan. Anal cytology becomes fruitless if all recommended follow-up steps are not received, especially in high-risk groups such as people with HIV.

A population-based cohort of HIV-positive adults with long-term follow-up found the 1 year risk of progression from high-grade cytology (defined as anal intraepithelial neoplasia III) to anal cancer was 1.2% and 5.7% for 5-year risk for progression.28 This progression rate to anal cancer has also been shown in retrospective studies of HIV-positive patients with high-grade anal dysplasia.29,30 We found 75% of our sample's follow-up with HRA exceeded more than 6 months after a documented abnormal anal cytology, whereas 43% of the sample received follow-up HRA by 12 months of documented abnormal anal cytology. Time to follow-up for HRA averaged 380 days for our sample. Further, HRA with biopsy is an important component to anal cancer screening and management due to high prevalence of high-risk HPV and false negatives associated with anal cytology alone in this group.31 This highlights the importance of timely HRA after an abnormal anal cytology as part of an effective screening strategy in this population.

Much of our sample with abnormal anal cytology was documented as either LSIL (43%) or ASCUS (41%). A multi-center study of HIV+ men found a majority of their sample with LSIL and ASCUS anal cytology regressed within 2 years.32 Yet, 19% of the sample with untreated HSIL or ASCUS-H maintained the same grade at 2 years, whereas 15% progressed from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade (ASCUS-H or HSIL). Since high-grade dysplasia is considered a precursor to anal cancer, experts recommend these patients should be prioritized for follow-up with HRA.18 Our study found HSIL and ASCUS to be protective of follow-up delays were the likelihood of receiving follow-up with 12 months was increased for patients with high-grade dysplasia. This finding is congruent with current expert recommendation for increased surveillance of this high-risk group.

We found HIV/AIDS-related stigma was associated with lower likelihood of receiving HRA follow-up within 6 months. HIV/AIDS-related stigma is defined as prejudice, discounting, discrediting, and discrimination directed at people living with HIV/AIDS.33,34 The psychological mechanisms of stigma is a complex interplay of knowledge and perceptions that living with HIV is a violation of social norms and subject to negative treatment. These mechanisms can impact psychological, behavioral, and health that often lead to negative outcomes.35 Prior studies also suggest stigma even occurs in health care environments and has deleterious impact on secondary health-related factors such as missing HIV medical care visits.36,37 Our findings are similar to Newman et al. who revealed in a focus group of gay men that stigma is a considerable barrier to anal cancer screening.38

Men in the focus group reported anal cancer screening requires disclosure of personal information regarding sexual behaviors and sexuality that may be stigmatizing. Additional qualitative findings among MSMs suggest stigma toward anal sexuality resulted in delay, avoidance, or discontinuation of health care.36 Our study substantiated these qualitative findings and the detrimental role stigma plays in health care and is a significant barrier to follow-up after abnormal anal cytology. It is important to note, transgender populations, specifically transgender women, have an increased risk for HPV and associated diseases.39–41 The transgender community face even greater stigma and barriers to health care, which can impact access to anal cancer screening and follow-up, thus driving inequalities and disparities.42,43 Future research should address the unique challenges among the transgender community to promote safe and equitable access to anal cancer screening and follow-up.

We found low health motivation as a barrier to HRA follow-up within 6 and 12 months. Anal cancer screening and HRA have been shown to be acceptable among PLWH;31,44–46 yet, barriers to anal cancer screening and management have been reported.38,47 A sample of HIV+ MSM in France reported a barrier to anal cancer screening uptake was lack of interest in screening.47 Further increased knowledge was higher among those who were willing to screen, whereas lower knowledge was reported among patients who were lost to follow-up for anal cancer screening.

Thus, it is suggested a lack of motivation or interest in anal cancer screening may be due to a decrease in knowledge or awareness of anal cancer among PLWH. Previous studies found decreased awareness and knowledge of anal cancer among PLWH.48–50 Given the suggested relationship between knowledge and screening adherence, it is warranted to increase knowledge and awareness of anal cancer screening and among this high-risk group. Further, the importance of follow-up care is also a critical component of comprehensive cancer prevention education.

The study's findings should be considered with limitations. The authors did not examine clinic-level factors that may have impacted time to HRA follow-up in this sample. HRA requires a clinician to be trained and certified to perform this procedure, which may impact availability and access to HRA. Notably, at the time of this study, the study site had one trained clinician to perform HRA, which may impact time to follow-up. Next, our study population received care at a comprehensive HIV clinic and is not representative of HIV patients who may receive care at a clinic that does not have access to anal cancer screening and HRA procedures.

Thus, follow-up to HRA after an abnormal anal cytology may be impacted if the patient must be referred to another clinic for these screening procedures. Thus, more research is warranted in diverse clinical settings. Women living with HIV was underrepresented in our sample (17%); thus, unique gender-specific barriers may not have been captured in this study. Finally, other factors that were not accounted for in the study may play a role in time to follow-up after abnormal anal cytology (i.e., community-level and policy-level barriers) and should be investigated in future studies.

Anal cancer screening and management guidelines supported by findings from a randomized clinical trial are forthcoming.51 Therefore, it is likely to be an increased uptake in anal cancer screening, thus subsequent HRA for histological confirmation to determine future management for PLWH. Nonadherence or missed opportunities at any stage of management can interfere with cancer prevention. Thus, our findings are at the forefront of identifying potential barriers to comprehensive management of PLWH after anal cancer screening.

Stigma and health motivation were found to be barriers to timely HRA follow-up and can interfere with an effective cancer preventive management. Raising knowledge and awareness of anal cancer screening and the importance of follow-up after abnormal anal cytology may help overcome these interpersonal barriers. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of such educational strategies. Further, clinician knowledge and practice, system-level and policy-level barriers must be further explored in future studies.

Authors' Contributions

Funding acquisition (lead), conceptualization (lead), and writing—original draft (lead) by J.W. Clinical supervision, writing—review and editing (equal) by L.F. Formal analysis (lead), writing—review and editing (equal) by C.C.M. Writing—review and editing (equal) by R.C. Investigation (supporting), writing—review and editing (equal) by R.K. Conceptualization (supporting), writing—review and editing (equal) by M.M.H. and D.W.B.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by grant funding from National Institute of Nursing Research (K01NR015733). The funder did not have input in the development or content of this article.

References

- 1. Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1500–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson L, Madeleine M, Newcomer L, Schwartz S, Daling J. Anal cancer incidence and survival: The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results experience, 1973–2000. Cancer 2004;101:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shiels M, Goedert J, Engels E. Recent trends and future directions in human immunodeficiency virus-associated cancer. Cancer 2010;116:5344–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Bringman D, Anton-Culver H. Increased incidence of squamous cell anal cancer among men with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shiels M, Cole S, Kirk G, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52:611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colón-López V, Shiels MS, Machin M, et al. Anal cancer risk among people with HIV infection in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:1026–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hessol NA, Whittemore H, Vittinghoff E, et al. Incidence of first and second primary cancers diagnosed among people with HIV, 1985–2013: A population-based, registry linkage study. Lancet HIV 2018;5:e647–e655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chin-Hong PV, Palefsky JM. Human papillomavirus anogenital disease in HIV-infected individuals. Dermatol Ther 2005;18:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Gonzales J, Berline J, Ahn DK, Greenspan JS. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in anal intraepithelial neoplasia and anal cancer. Cancer Res 1991;51:1014–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Da Costa M, Greenblatt RM. Prevalence and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Infect Dis 2001;183:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Devaraj B, Cosman BC. Expectant management of anal squamous dysplasia in patients with HIV. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Hogeboom CJ, Berry JM, Jay N, Darragh TM. Anal cytology as a screening tool for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997;14:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palefsky J. Practising high-resolution anoscopy. Sex Health 2012;9:580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee JY, Lensing SY, Berry-Lawhorn JM, et al. Design of the anal cancer/HSIL outcomes research study (ANCHOR study): A randomized study to prevent anal cancer among persons living with HIV. Contemp Clin Trials 2022;113:106679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goddard SL, Templeton DJ, Petoumenos K, et al. Prevalence and association of Perianal and intra-anal warts with composite high-grade squamous Intraepithelial lesions among Gay and bisexual men: Baseline data from the study of the prevention of anal cancer. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020;34:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiao EY, Giordano TP, Palefsky JM, Tyring S, El Serag H. Screening HIV-infected individuals for anal cancer precursor lesions: A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wells JS, Holstad MM, Thomas T, Bruner DW. An integrative review of guidelines for anal cancer screening in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. New York State Department of Health. Primary Care Approach to the HIV-Infected Patient. New York: New York State Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ortoski RA, Kell CS. Anal cancer and screening guidelines for human papillomavirus in men. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011;111:S35–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palefsky J, Berry JM, Jay N. Anal cancer screening. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e279–e280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Primary Care of Veterans with HIV: Anal Dysplasia.. 2009. Available at: www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/pcm-manual.pdf (Last accessed October 16, 2013).

- 23. Cejtin HE, Komaroff E, Massad LS, et al. Adherence to colposcopy among women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999;22:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res 1999;46:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Champion VL. Instrument development for health belief model constructs. Adv Nurs Sci 1984;6:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: The Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care 2009;21:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arens Y, Gaisa M, Goldstone S, et al. Risk of invasive anal cancer in HIV infected patients with high grade anal dysplasia: A population-based cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 2019;62:934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cachay ER, Mathews WC. Human papillomavirus, anal cancer, and screening considerations among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Rev 2013;15:122–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cajas-Monson LC, Ramamoorthy SL, Cosman BC. Expectant management of high-grade anal dysplasia in people with HIV: Long-term data. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:1357–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS 2016;30:1375–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. D'Souza G, Wentz A, Wiley D, et al. Anal cancer screening in men who have sex with men in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;71:570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav 2009;13:1160–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Florom-Smith AL, De Santis JP. Exploring the concept of HIV-related stigma. Nursing Forum 2012;47:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kutner BA, Simoni JM, Aunon FM, Creegan E, Balán IC. How stigma toward anal sexuality promotes concealment and impedes health-seeking behavior in the US among cisgender men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2021;50:1651–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reif S, Wilson E, McAllaster C, Pence B. The relationship of HIV-related stigma and health care outcomes in the US deep south. AIDS Behav 2019;23:242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newman PA, Roberts KJ, Masongsong E, Wiley DJ. Anal cancer screening: Barriers and facilitators among ethnically diverse gay, bisexual, transgender, and other men who have sex with men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 2008;20:328–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hutchison LM, Boscoe FP, Feingold BJ. Cancers disproportionately affecting the New York state transgender population, 1979–2016. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1260–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. LoSchiavo C, Greene RE, Halkitis PN. Human papillomavirus prevalence, genotype diversity, and risk factors among transgender women and nonbinary participants in the P18 Cohort Study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020;34:502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singh V, Gratzer B, Gorbach PM, et al. Transgender women have higher human papillomavirus prevalence than men who have sex with men—Two US cities, 2012–2014. Sex Transm Dis 2019;46:657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brookfield S, Dean J, Forrest C, Jones J, Fitzgerald L. Barriers to accessing sexual health services for transgender and male sex workers: A systematic qualitative meta-summary. AIDS Behav 2020;24:682–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown B, Poteat T, Marg L, Galea JT. Human papillomavirus-related cancer surveillance, prevention, and screening among transgender men and women: Neglected populations at high risk. LGBT Health 2017;4:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lam J, Barnell G, Merchant M, Ellis C, Silverberg M. Acceptability of high-resolution anoscopy for anal cancer screening in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 2018;19:716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Landstra J, Ciarrochi J, Deane FP. Psychosocial aspects of anal cancer screening: A review and recommendations. Sex Health 2012;9:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tinmouth J, Raboud J, Ali M, et al. The psychological impact of being screened for anal cancer in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vanhaesebrouck A, Pernot S, Pavie J, et al. Factors associated with anal cancer screening uptake in men who have sex with men living with HIV: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Prev 2020;29:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, Johnson P. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men. LGBT Health 2016;3:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rodriguez SA, Higashi RT, Betts AC, et al. Anal cancer and anal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and perceived risk among women living with HIV. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021;25:43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wells JS, Flowers L, Paul S, Nguyen ML, Sharma A, Holstad M. Knowledge of anal cancer, anal cancer screening, and HPV in HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Cancer Educ 2020;35:606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Treating anal Cancer Precursor Lesions Reduces Cancer Risk for People with HIV [press release]. Available at: https://anchorstudy.org/sites/default/files/newsletters/anchor_press_release_07oct2021.pdf (Last accessed October 7, 2021).