Abstract

Background

Therapies for refractory cytomegalovirus infections (with or without resistance [R/R]) in transplant recipients are limited by toxicities. Maribavir has multimodal anti-cytomegalovirus activity through the inhibition of UL97 protein kinase.

Methods

In this phase 3, open-label study, hematopoietic-cell and solid-organ transplant recipients with R/R cytomegalovirus were randomized 2:1 to maribavir 400 mg twice daily or investigator-assigned therapy (IAT; valganciclovir/ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir) for 8 weeks, with 12 weeks of follow-up. The primary endpoint was confirmed cytomegalovirus clearance at end of week 8. The key secondary endpoint was achievement of cytomegalovirus clearance and symptom control at end of week 8, maintained through week 16.

Results

352 patients were randomized (235 maribavir; 117 IAT). Significantly more patients in the maribavir versus IAT group achieved the primary endpoint (55.7% vs 23.9%; adjusted difference [95% confidence interval (CI)]: 32.8% [22.80–42.74]; P < .001) and key secondary endpoint (18.7% vs 10.3%; adjusted difference [95% CI]: 9.5% [2.02–16.88]; P = .01). Rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were similar between groups (maribavir, 97.4%; IAT, 91.4%). Maribavir was associated with less acute kidney injury versus foscarnet (8.5% vs 21.3%) and neutropenia versus valganciclovir/ganciclovir (9.4% vs 33.9%). Fewer patients discontinued treatment due to TEAEs with maribavir (13.2%) than IAT (31.9%). One patient per group had fatal treatment-related TEAEs.

Conclusions

Maribavir was superior to IAT for cytomegalovirus viremia clearance and viremia clearance plus symptom control maintained post-therapy in transplant recipients with R/R cytomegalovirus. Maribavir had fewer treatment discontinuations due to TEAEs than IAT.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT02931539 (SOLSTICE).

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, transplant recipients, antiviral agents, drug resistance, maribavir

In this phase 3 study of refractory cytomegalovirus (with/without resistance) post-transplant, maribavir was superior to investigator-assigned treatment (IAT) for viremia clearance and clearance plus symptom control maintained post-therapy, with less nephrotoxicity (vs foscarnet), myelotoxicity (vs valganciclovir/ganciclovir), and discontinuations (vs IAT).

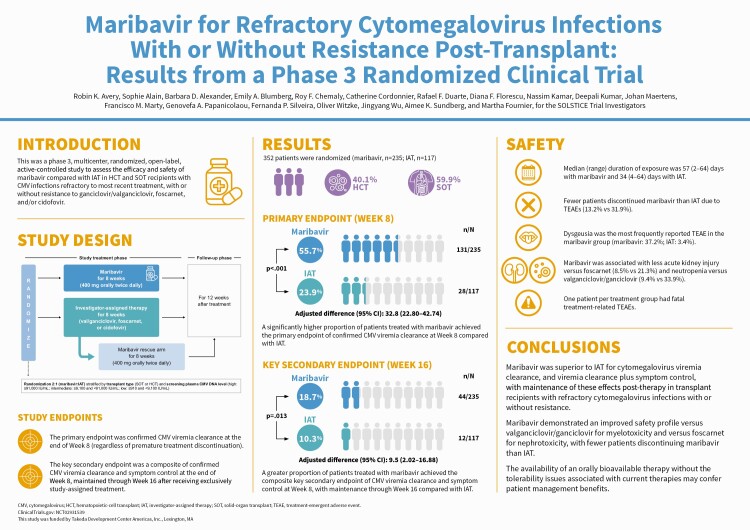

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, a serious post-transplantation complication [1], significantly increases the risk of morbidity and mortality [2–5], particularly among transplant recipients with resistant or refractory infection [6–8]. Transplant recipients with resistant or refractory CMV often require prolonged anti-CMV therapy [6, 7], and treatment options are suboptimal due to limited efficacy [9, 10], toxicities, and possible resistance or cross-resistance among currently available anti-CMV agents [11, 12]. Treatment-limiting toxicities associated with available antiviral agents include myelosuppression with valganciclovir/ganciclovir and nephrotoxicity with foscarnet or cidofovir [5, 13–15]. Thus, there is an unmet need for new, effective agents with improved safety profiles.

Maribavir, a benzimidazole riboside, has multimodal anti-CMV activity, inhibiting CMV DNA replication, encapsidation, and nuclear egress of viral capsids via inhibition of the UL97 protein kinase and its natural substrates [16–19]. Maribavir is active in vitro and in vivo against CMV, including strains resistant to ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir [20, 21]. In 2 phase 2 studies of maribavir (400 mg, 800 mg, and 1200 mg twice daily [BID]) in solid-organ (SOT) and hematopoietic-cell transplant (HCT) recipients, maribavir was efficacious in clearing viremia within 6 weeks in patients with refractory CMV infection (with or without resistance [R/R]) [22], as well as in patients without R/R CMV infection or CMV organ disease [23]

This phase 3 trial compared the efficacy and safety of maribavir versus investigator-assigned therapy (IAT) for treatment of R/R CMV infection in SOT and HCT recipients.

METHODS

The roles of the independent Data Monitoring Committee and the Endpoint Adjudication Committee (EAC) are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Trial Design and Patients

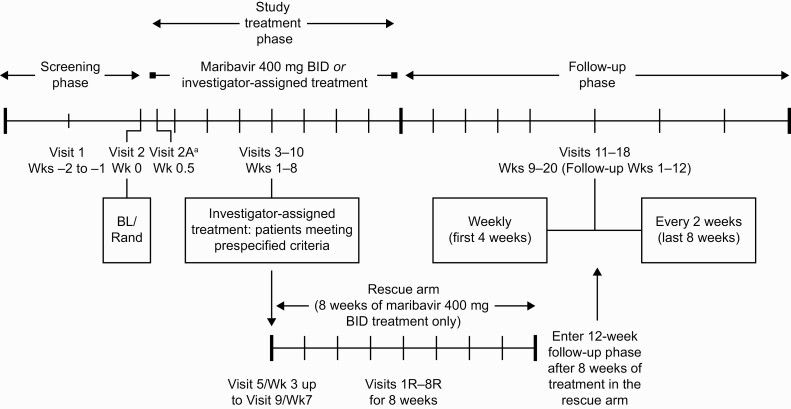

In this phase 3, randomized, open-label, multicenter, active-controlled trial, HCT and SOT recipients (aged ≥12 years) were eligible if they had documented CMV infection in plasma (DNAemia, referred to as viremia), with a CMV DNA screening value of 910 IU/mL or greater in 2 consecutive tests separated by 1 or more day determined by local/central specialty laboratory quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The detailed trial design is shown in Figure 1. The patient’s CMV infection must have been refractory to the most recent treatment, defined as failure to achieve a more than 1-log10 decrease in CMV DNA after 14 days or more of anti-CMV treatment [22]. Patients with resistant CMV infection, defined as 1 or more genetic mutation associated with resistance to ganciclovir/valganciclovir, foscarnet, and/or cidofovir, were also included if they met refractory criteria. Key exclusion criteria included resistant or refractory CMV infection due to inadequate adherence to prior anti-CMV treatment; CMV disease with central nervous system involvement or retinitis; and concomitant need for leflunomide, letermovir, or artesunate (Supplementary Methods).

Figure 1.

Trial design. aVisit 2A/2A(R) was only required for patients receiving tacrolimus, cyclosporine, everolimus, or sirolimus at visit 2/2R. Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; BL, baseline; R, rescue; Rand, randomization; Wk, week.

Eligible patients were randomized 2:1 to receive maribavir (400 mg orally BID) or IAT for 8 weeks (Figure 1) through a centralized interactive response technology system. Randomization was stratified by transplant type (HCT/SOT) and CMV DNA level (using the most recent local/central laboratory qPCR screening results available; high, ≥91 000 IU/mL; intermediate, ≥9100 to <91 000 IU/mL; low, <9100 to ≥910 IU/mL). The treatment phase was followed by 12 weeks of follow-up, in which patients were off study-assigned therapy.

The choice of specific IAT was at the investigators’ discretion and could include mono- or combination therapy (≤2 drugs) with intravenous (IV) ganciclovir, oral valganciclovir, IV foscarnet, or IV cidofovir (Supplementary Methods). Switching between ganciclovir and valganciclovir was permitted. A maribavir rescue arm was an option for patients originally assigned IAT after 3 or more weeks of treatment upon medical monitor confirmation of meeting 1 of 3 prespecified criteria (Supplementary Methods).

The study was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review boards/independent ethics committees at each center approved the trial. All patients/legal guardians provided written informed consent.

Endpoints and Assessments

The primary endpoint was confirmed CMV viremia clearance at the end of week 8 (regardless of premature treatment discontinuation). Confirmed viremia clearance was defined as plasma CMV DNA level below the lower limit of quantification (<137 IU/mL) in 2 consecutive post-baseline samples, separated by 5 or more days, performed at the central laboratory using COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan CMV Test (Roche Diagnostics). Patients who received maribavir rescue or alternative anti-CMV treatment before the end of week 8, or who failed to achieve confirmed CMV viremia clearance at week 8 (including missing virologic data), were considered nonresponders.

The key secondary endpoint was a composite of confirmed CMV viremia clearance and symptom control at the end of week 8, maintained through week 16 (8 weeks beyond the treatment phase) after receiving exclusively study-assigned treatment. Symptom control was defined as resolution/improvement of CMV disease/syndrome for patients symptomatic at baseline or absence of the development of CMV disease/syndrome for patients asymptomatic at baseline. Cytomegalovirus disease/syndrome was assessed by the investigator using the classification in Ljungman et al [24, 25]; assessments were adjudicated by an independent, blinded EAC. Additional secondary and exploratory endpoints and study assessment details are within the Supplementary Methods.

Safety endpoints included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and serious TEAEs (TESAEs).

Statistical Analysis

Sample size determination details are described within the Supplementary Methods. Analyses of the primary and key secondary endpoints were conducted in the treatment group to which patients were randomized (Randomized Population). Difference in the proportion of patients achieving the primary endpoint between treatment groups was obtained using Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel weighted average across strata of baseline central laboratory CMV viral load (low, <9100 IU/mL; intermediate/high, ≥9100 IU/mL) and transplant type (SOT, HCT). If the difference in the proportion of patients achieving clearance at the end of week 8 with maribavir was higher than IAT (P ≤ .05), maribavir was superior to IAT. The key secondary endpoint was analyzed using the same method. The primary endpoint was also evaluated in prespecified subgroups in the randomized population using similar methods, including any applicable stratification factors, and in multiple prespecified sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Methods). Additionally, an analysis of the primary endpoint in the subset of patients who completed 8 weeks of treatment was conducted. Hypothesis testing of primary and key secondary endpoints was adjusted for multiple comparisons using a fixed-sequence testing procedure to control the family-wise type 1 error rate at a 2-sided 5% level. Other analyses did not control for multiplicity of inferences (Supplementary Methods). Safety data were analyzed descriptively in all patients who received a dose of study drug (Safety Population).

RESULTS

Patients

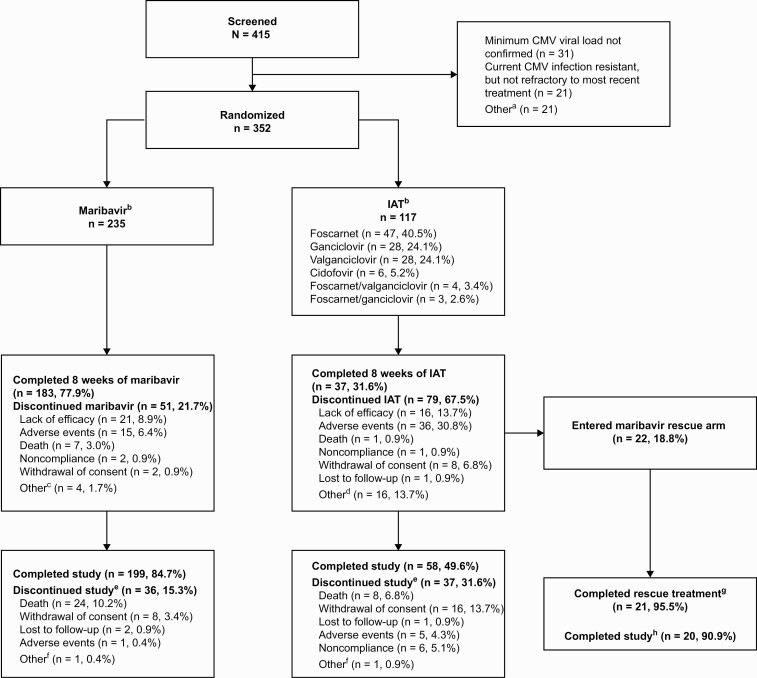

The study was conducted between December 2016 and August 2020. A total of 415 patients were screened (101 sites, 12 countries) and 352 were randomized (maribavir, n = 235; IAT, n = 117) (Figure 2); 1 patient per group did not receive the study drug. The median age of patients was 55 (range, 19–79) years and baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment groups (Table 1; Supplementary Tables 1 and 2); 40.1% of patients had undergone HCT and 59.9% SOT. Overall, 257 patients (73.0%) completed the study (maribavir, 199 [84.7%]; IAT, 58 [49.6%]), and 22 patients received maribavir as rescue treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition at enrollment, randomization, and follow-up. Percentages were calculated based on the number of patients randomized to each treatment group. Percentages may not total to 100% due to rounding. Serious AEs were recorded until the end of trial participation or resolution (whichever was later); median on-study duration was 141.0 days in each group. aPatients could have multiple reasons for not being randomized. Other reasons were: patient did not receive an HCT or SOT (n = 1); CMV infection not confirmed refractory to most recent treatment (n = 2); investigator not willing to treat the patient with ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir (n = 2); platelet count <25 000/mm3 (n = 5); hemoglobin <8 g/dL (n = 1); eGFR ≤30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 1); pregnancy (n = 1); patient was not willing/not able to comply fully with study procedures/restrictions (n = 3); current refractory or resistant CMV infection due to inadequate adherence to prior treatment (n = 2); serum aspartate aminotransferase >5 × ULN at screening, or serum alanine aminotransferase >5 × ULN at screening, or total bilirubin ≥3.0 × ULN at screening (n = 1); received any investigational agent with known anti-CMV activity within 30 days before initiation of study treatment or investigational CMV vaccine at any time (n = 1); and active malignancy (n = 1). bOne patient per group was randomized but did not receive trial medication. Percentage for each IAT type was calculated based on n = 116. cOther reasons for treatment discontinuation in the maribavir group included investigator decision to switch to letermovir, CMV detected in patient’s cerebrospinal fluid, nothing-by-mouth status with mental status change with risk for aspiration, and disease progression (in 1 patient each). dOther reasons for treatment discontinuation in the IAT group were: low viral load/CMV clearance (with concern of toxicity with continued administration of IAT (n = 9), patient safety (n = 3), patient/investigator request (n = 2), no efficacy and patient ineligible for rescue therapy (n = 1), and peripherally inserted central catheter issues (n = 1). eThese results are based on investigator determination for the primary reason for study discontinuation. fOther reasons for study discontinuation in maribavir or IAT group included investigator discretion to discontinue 1 patient before dosing with maribavir, and no efficacy with IAT for a patient who was not eligible for rescue therapy. gPer protocol, maribavir rescue arm treatment was discontinued in 1 patient due to CMV encephalitis. hOne patient was unable to complete follow-up visits in the study due to hospitalization in a different city and therefore did not complete the maribavir rescue study period. Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CMV, cytomegalovirus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HCT, hematopoietic-cell transplant; IAT, investigator-assigned therapy; SOT, solid-organ transplant; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline (Randomized Population)

| Characteristics | Maribavir (n = 235) | IAT (n = 117) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 57.0 | 54.0 |

| Range | (19–79) | (19–77) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 148 (63.0) | 65 (55.6) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 179 (76.2) | 87 (74.4) |

| Black or African American | 29 (12.3) | 18 (15.4) |

| Asian | 9 (3.8) | 7 (6.0) |

| Other | 16 (6.8) | 5 (4.3) |

| Missing | 2 (0.9) | 0 |

| Solid-organ transplant,a n (%) | 142 (60.4) | 69 (59.0) |

| Kidneyb | 74 (52.1) | 32 (46.4) |

| Lungb | 40 (28.2) | 22 (31.9) |

| Heartb | 14 (9.9) | 9 (13.0) |

| Multipleb | 5 (3.5) | 5 (7.2) |

| Liverb | 6 (4.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pancreasb | 2 (1.4) | 0 |

| Intestineb | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Hematopoietic-cell transplant,c n (%) | 93 (39.6) | 48 (41.0) |

| Allogeneicd | 92 (98.9) | 48 (100.0) |

| Donor typee | ||

| HLA identical sibling | 13 (14.1) | 2 (4.2) |

| HLA matched other relative | 12 (13.0) | 10 (20.8) |

| HLA mismatched relative | 11 (12.0) | 7 (14.6) |

| Unrelated donor | 56 (60.9) | 29 (60.4) |

| Stem cell sourcee | ||

| Peripheral blood stem cell | 71 (77.2) | 30 (62.5) |

| Bone marrow | 16 (17.4) | 13 (27.1) |

| Cord blood | 5 (5.4) | 5 (10.4) |

| Presence of acute GvHD confirmed for HCT recipientsf | 23 (25.0) | 8 (17.0) |

| Presence of chronic GvHD confirmed for HCT recipientsf | 6 (6.5) | 5 (10.6) |

| CMV DNA levels by central laboratory at baseline, IU/mL | ||

| Median (IQR)g | 3377.0 (1036.0–12 544.0) | 2869.0 (927.0–11 636.0) |

| CMV DNA levels category as reported by central laboratory at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Low (<9100 IU/mL) | 153 (65.1) | 85 (72.6) |

| Intermediate (≥9100 and <91 000 IU/mL) | 68 (28.9) | 25 (21.4) |

| High (≥91 000 IU/mL) | 14 (6.0) | 7 (6.0) |

| Symptomatic CMV infection by Endpoint Adjudication Committee,h n (%) | 21 (8.9) | 8 (6.8) |

| CMV syndrome in SOT recipients | 10 (47.6) | 7 (87.5) |

| CMV diseasei | 12 (57.1) | 1 (12.5) |

| CMV serostatus for SOT recipients, n (%) | n = 142 | n = 69 |

| Donor +/recipient + | 11 (7.7) | 8 (11.6) |

| Donor −/recipient + | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.4) |

| Donor +/recipient − | 120 (84.5) | 56 (81.2) |

| Donor −/recipient − | 7 (4.9) | 3 (4.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) |

| CMV serostatus for HCT recipients, n (%) | n = 93 | n = 48 |

| Donor +/recipient + | 42 (45.2) | 17 (35.4) |

| Donor −/recipient + | 39 (41.9) | 26 (54.2) |

| Donor +/recipient − | 6 (6.5) | 3 (6.3) |

| Donor −/recipient − | 5 (5.4) | 1 (2.1) |

| Missing | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| Patients with or without CMV mutations known to confer resistance to ganciclovir, foscarnet, and/or cidofovir,j n (%) | ||

| Refractory CMV infection with resistance | 121 (51.5) | 69 (59.0) |

| Refractory CMV infection without resistance | 96 (40.9) | 34 (29.1) |

| Missing resistance results | 18 (7.7) | 14 (12.0) |

| Most recent anti-CMV agent prior to randomization,k n (%) | ||

| Ganciclovir/valganciclovir | 204 (86.8) | 98 (83.8) |

| Foscarnet | 27 (11.5) | 18 (15.4) |

| Cidofovir | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

Maribavir, n = 235, and IAT, n = 117, unless otherwise specified. All CMV DNA levels reported by central laboratory were based on plasma concentration.

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; GvHD, graft-versus-host disease; HCT, hematopoietic-cell transplant; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IAT, investigator-assigned therapy; IQR, interquartile range; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; SOT, solid-organ transplant.

Based on most recent transplant type. Those classed as “multiple” had multiple organs transplanted at once.

The denominator is the number of patients who received SOT within each treatment arm.

There was 1 (1.1%) autologous HCT in the maribavir group.

The denominator is the number of patients who received HCT within each treatment arm.

The denominator is the number of patients who received allogenic HCT within each treatment arm.

Based on the safety population.

Half of the LLOQ value (ie, 137/2 = 68.5) was imputed for those who had <LLOQ.

Patients were not stratified by symptomatic infection at randomization. One patient had both CMV disease and syndrome at baseline.

Most patients had CMV gastrointestinal disease: 10/12 for the maribavir arm and 1/1 for the IAT arm.

Per central laboratory results.

Defined as the most recent anti-CMV agent, used to confirm refractory eligibility criteria.

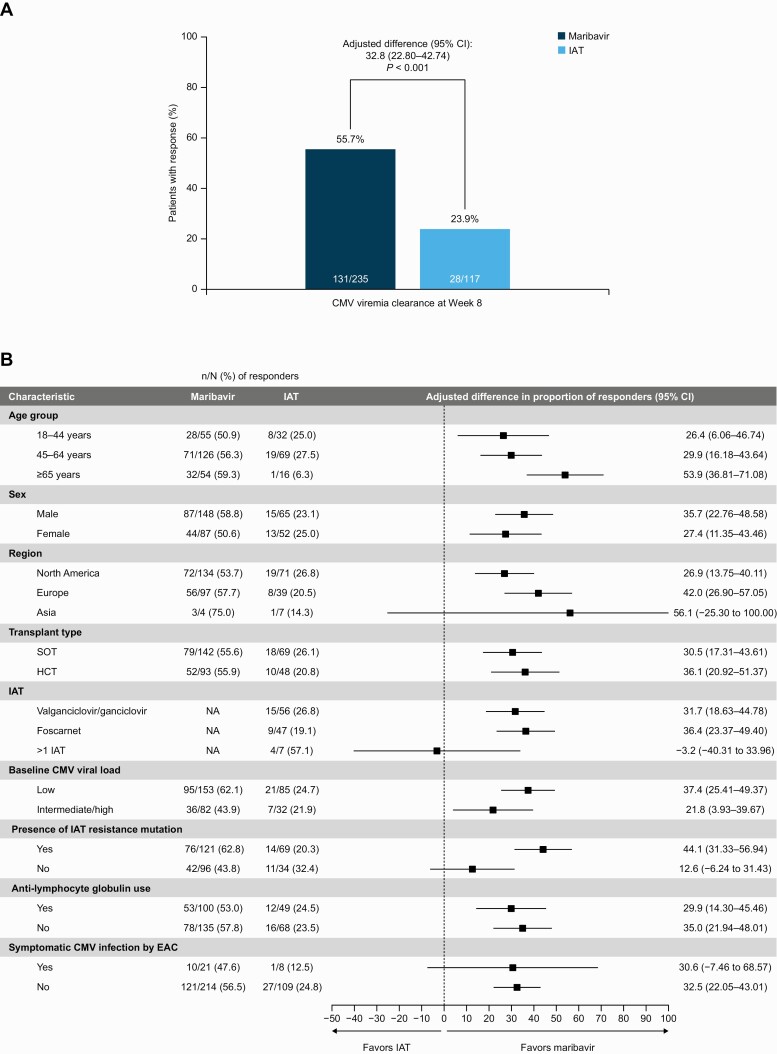

Efficacy

Primary Endpoint

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the maribavir group achieved confirmed CMV viremia clearance at week 8 than in the IAT group (55.7% [131/235] vs 23.9% [28/117]; adjusted difference: 32.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 22.80–42.74%; P < .001) (Figure 3A). Across prespecified subgroups, results remained generally consistent, including transplant type (Figure 3B). A greater proportion of patients with baseline genotypic resistance to IAT achieved viremia clearance at the end of week 8 in the maribavir versus IAT group (62.8% vs 20.3%; adjusted difference: 44.1%; 95% CI: 31.33–56.94%). A numeric treatment difference between maribavir and IAT was also observed among patients with refractory (nonresistant) CMV infection (43.8% vs 32.4%; adjusted difference: 12.6%; 95% CI: −6.24 to 31.43%). Reasons for primary endpoint nonresponders are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted, and the results were consistent with the primary analysis results (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 3.

A, CMV viremia clearance at week 8 overall (primary endpoint). B, CMV viremia clearance at week 8 in subgroups (randomized population). Between-group differences adjusted for applicable stratification factor(s) of baseline CMV DNA level (low or intermediate/high) and SOT/HCT. Six patients received cidofovir as IAT (data not shown); 1 patient did not receive a dose of IAT. Symptomatic CMV infection at baseline was determined by an independent and blinded EAC. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EAC, Endpoint Adjudication Committee; HCT, hematopoietic-cell transplant; IAT, investigator-assigned therapy; NA, not applicable as adjusted between-group differences used the full maribavir group; SOT, solid-organ transplant.

Secondary Endpoints

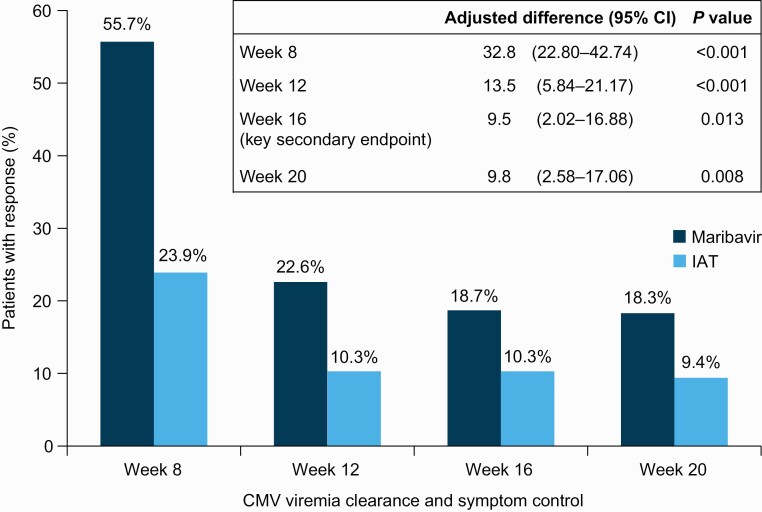

A higher proportion of patients randomized to maribavir versus IAT demonstrated CMV viremia clearance and symptom control at the end of week 8, maintained through week 16 (key secondary endpoint; 18.7% vs 10.3%; adjusted difference: 9.5%; 95% CI: 2.02–16.88%; P = .01) (Figure 4). This effect was consistent at weeks 12 (22.6% vs 10.3%; P < .001) and 20 (18.3% vs 9.4%; P = .008). Viremia clearance after 8 weeks of study-assigned treatment and recurrence during the first 8 weeks of the study are described in the Supplementary Results.

Figure 4.

Secondary endpoints: confirmed viremia clearance and symptom control at week 8 and maintained through week 12, week 16 (key secondary endpoint), and week 20 (randomized population). Symptom control was defined as resolution/improvement of CMV disease/syndrome for patients symptomatic at baseline or absence of the development of CMV disease/syndrome for patients asymptomatic at baseline. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; IAT, investigator-assigned therapy.

Overall, 40 deaths were reported (Supplementary Table 4); 8 deaths were due to CMV disease (maribavir: 4 [1.7%]; IAT: 4 [3.4%]). All-cause mortality was 11.5% with maribavir and 11.1% with IAT.

Exploratory Evaluations

Kaplan–Meier median (95% CI) time to first confirmed CMV viremia clearance (within study week 8) occurred earlier in the maribavir versus IAT groups (22.0 [21.0–23.0] vs 27.0 [22.0–30.0] days; P = .04, log-rank test) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Clinically relevant recurrence (ie, recurrence among responders, after week 8, who received alternative anti-CMV treatment) occurred less frequently in patients randomized to maribavir (26.0%) than IAT (35.7%). Among the 22 patients who initially received IAT and subsequently received maribavir rescue treatment due to lack of response, 11 (50.0%) achieved confirmed CMV viremia clearance at week 8 of the maribavir rescue treatment phase.

Safety

Median (range) duration of exposure was 57 (2–64) days with maribavir and 34 (4–64) days with IAT. At least 1 TEAE was reported in 97.4% and 91.4% of patients in the maribavir and IAT groups, respectively (Table 2). Fewer patients discontinued maribavir than IAT due to TEAEs (13.2% and 31.9%) (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Occurring in ≥10% of Patients in Either Treatment Group or for Individual Investigator-Assigned Therapy (Safety Population)

| System Organ Class Preferred Term | Maribavir (n = 234) | IAT (n = 116) | IAT Typea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ganciclovir/Valganciclovir (n = 56) | Foscarnet (n = 47) | Cidofovir (n = 6) | |||

| Any TEAE | 228 (97.4) | 106 (91.4) | 51 (91.1) | 43 (91.5) | 5 (83.3) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | |||||

| Anemia | 29 (12.4) | 14 (12.1) | 4 (7.1) | 9 (19.1) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 7 (3.0) | 8 (6.9) | 7 (12.5) | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 22 (9.4) | 26 (22.4) | 19 (33.9) | 7 (14.9) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||

| Diarrhea | 44 (18.8) | 24 (20.7) | 13 (23.2) | 9 (19.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| Nausea | 50 (21.4) | 25 (21.6) | 8 (14.3) | 14 (29.8) | 1 (16.7) |

| Vomiting | 33 (14.1) | 19 (16.4) | 7 (12.5) | 8 (17.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | |||||

| Fatigue | 28 (12.0) | 10 (8.6) | 7 (12.5) | 3 (6.4) | 0 |

| Edema peripheral | 17 (7.3) | 9 (7.8) | 3 (5.4) | 5 (10.6) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 24 (10.3) | 17 (14.7) | 6 (10.7) | 9 (19.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Infections and infestations | |||||

| CMV viremiab | 24 (10.3) | 6 (5.2) | 4 (7.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | |||||

| Hypokalemia | 8 (3.4) | 11 (9.5) | 1 (1.8) | 9 (19.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 9 (3.8) | 10 (8.6) | 2 (3.6) | 7 (14.9) | 1 (16.7) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 4 (1.7) | 5 (4.3) | 0 | 5 (10.6) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | |||||

| Dysgeusia | 87 (37.2) | 4 (3.4) | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Headache | 19 (8.1) | 15 (12.9) | 6 (10.7) | 8 (17.0) | 0 |

| Paresthesia | 4 (1.7) | 5 (4.3) | 0 | 5 (10.6) | 0 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | |||||

| Acute kidney injury | 20 (8.5) | 11 (9.5) | 1 (1.8) | 10 (21.3) | 0 |

| Vascular disorders | |||||

| Hypertension | 9 (3.8) | 8 (6.9) | 1 (1.8) | 6 (12.8) | 0 |

Data are presented as n (%).The cidofovir group was not considered in the application of the 10% cutoff due to low patient numbers (n = 6). The on-treatment observation period started at the time of study-assigned treatment initiation through 7 days after the last dose of study-assigned treatment or through 21 days if cidofovir was used, or until the maribavir rescue treatment initiation or until the nonstudy CMV treatment initiation, whichever was earlier. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 23.0.

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; IAT, investigator-assigned therapy; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Overall, 7 patients received a combination of valganciclovir/ganciclovir and foscarnet (not included in the table).

Events such as worsening of CMV viremia were coded to the preferred term of CMV viremia.

Dysgeusia was the most frequently reported TEAE in the maribavir group (maribavir: 37.2%; IAT: 3.4%) (Table 2); this was reported as mostly mild, and usually resolved either on treatment or shortly after the last dose of maribavir (Kaplan–Meier median time to resolution off treatment: 7 days), and rarely led to treatment discontinuation (0.9% of patients in the maribavir group). Neutropenia was the most frequently reported TEAE in the IAT group (maribavir: 9.4%; IAT: 22.4%), with highest frequency in patients treated with valganciclovir/ganciclovir (33.9%). Rates of nausea (21.4% vs 21.6%), vomiting (14.1% vs 16.4%), and diarrhea (18.8% vs 20.7%) were similar between treatment groups. In the maribavir group, leukopenia occurred less frequently versus valganciclovir/ganciclovir (3.0% vs 12.5%). Hypokalemia and acute kidney injury (AKI) occurred less frequently in the maribavir group versus foscarnet (3.4% vs 19.1% and 8.5% vs 21.3%, respectively). For treatment-related TEAEs, neutropenia was less frequent with maribavir versus valganciclovir/ganciclovir (1.7% vs 25.0%), and AKI was less frequent with maribavir versus foscarnet (1.7% vs 19.1%) (Supplementary Table 6). There were no cases of treatment-related neutropenia or AKI leading to discontinuation in the maribavir group; 19.6% of patients discontinued valganciclovir/ganciclovir due to treatment-related neutropenia and 12.8% discontinued foscarnet due to treatment-related AKI.

There was 1 treatment-related TESAE of sudden death on study day 7 in the maribavir group, possibly due to cardiac arrhythmia resulting from drug interactions according to the investigator. The patient received concomitant medications known to interact and prolong QT intervals (domperidone and posaconazole); the event was assessed by the sponsor as being unrelated to maribavir. One patient in the IAT group had fatal TESAEs on study day 73 (febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, and tuberculosis) related to valganciclovir. Further details are described in the Supplementary Results.

Increased blood immunosuppressant drug levels were reported as TEAEs in 21 (9.0%) patients in the maribavir group (tacrolimus: n = 19; sirolimus: n = 2) and in 1 (0.9%) patient in the IAT (valganciclovir/ganciclovir) group.

DISCUSSION

This phase 3 trial in transplant recipients with R/R CMV infection demonstrated that maribavir was superior to IAT (ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir) for CMV viremia clearance at week 8. Patients in the maribavir group had a lower treatment discontinuation rate than those with IAT and also had reduced frequency of neutropenia versus valganciclovir/ganciclovir and AKI versus foscarnet (treatment-limiting toxicities frequently associated with available therapies). The inclusion of a rescue arm within the study design (Figure 1) addressed the antecedent possibility of poor outcomes with IAT.

The benefit with respect to viremia clearance at week 8 of maribavir over IAT was consistent across key subpopulations including HCT and SOT recipients, and patients with resistant CMV infection. This benefit was also maintained in analyses limited to patients completing 8 weeks of study-assigned treatment, included patients in the IAT group who switched to alternative (nonstudy) anti-CMV treatment before week 8 as responders (if meeting criteria of viremia clearance at week 8) or controlled for early treatment discontinuations in the IAT group. Cytomegalovirus viremia clearance appeared earlier with maribavir versus IAT. Notably, CMV viremia persistence in patients with refractory or resistant CMV may be the harbinger of clinical deterioration [26]. The CMV Consensus Forum recently concluded that treatment of viremia prevented disease, viral load kinetics predicted progression to disease, and viral load is an appropriate surrogate endpoint in CMV clinical trials [26]. Thus, the results reported here show that maribavir enables CMV viremia clearance (including drug-resistant strains) with an improved safety profile, illustrating the potential of maribavir to change CMV infection management.

Significantly more patients in the maribavir versus IAT group achieved viremia clearance and symptom control at week 8, with maintenance to week 16, although the percentage of patients achieving this endpoint was low in both groups. As CMV is a latent virus, in the setting of continued immunosuppression and simultaneous cessation of effective antiviral therapy CMV viremia recurrence off treatment was expected. Among patients meeting the primary endpoint, CMV recurrence necessitating additional anti-CMV treatment in the follow-up period occurred less frequently with maribavir than IAT. The results raise important questions about the current treatment paradigm for these patients, as available agents have limitations for prolonged use. The availability of an orally bioavailable therapy without the tolerability issues associated with current therapies may confer patient management benefits.

Despite shorter drug exposure with IAT than maribavir in this study, as treatment discontinuations were more than 2-fold higher with IAT than maribavir, the incidence of TESAEs was similar between groups and treatment-related TESAEs occurred less frequently with maribavir than IAT. Dysgeusia, while common with maribavir, only led to discontinuation in 0.9% of patients in the maribavir group. Importantly, consistent with previous studies [22, 23], maribavir-treated patients had substantially lower rates of neutropenia and renal impairment compared with valganciclovir/ganciclovir and foscarnet, respectively. Safety data from this phase 3 study were consistent with those from a phase 2 study of maribavir in R/R CMV infections in HCT/SOT recipients, wherein 400–1200-mg BID doses of maribavir were administered for up to 24 weeks [22]. In the current study, the TEAE of immunosuppressant drug concentration level increase was more common in patients receiving maribavir than IAT. Increased immunosuppressant levels have been previously observed in patients treated with maribavir (particularly at the highest [1200 mg BID] dose) [22, 23], and maribavir is known to inhibit P-gp, a transporter involved in distribution and disposition of standard immunosuppression medications [27]. During the trial, immunosuppressant drug concentration levels were frequently monitored throughout maribavir treatment, particularly following initiation and discontinuation of maribavir, and immunosuppressants were dose adjusted as needed.

All-cause mortality was low and comparable between maribavir and IAT groups (~11%), and was lower than previously reported in some studies of patients with resistant or refractory CMV infection (31–50%) [5, 13]. These differences may be due to the study design (Figure 1) and the exclusion of patients from the trial at high risk of death due to underlying disease; these factors may also account for the similarities in all-cause mortality between treatment groups in this study.

With regard to the patients who died due to CMV encephalitis, it is important to note that limited preclinical data suggest that maribavir does not cross the blood–brain barrier [28]. Patients with CMV encephalitis were excluded from the study, and patients who developed new-onset encephalitis while on treatment with maribavir were required to discontinue maribavir per protocol.

Management of resistance and cross-resistance to anti-CMV therapies is challenging. Currently approved therapies inhibit CMV DNA polymerase (UL54) [29]. Valganciclovir/ganciclovir requires activation by viral UL97 protein kinase [29]. Therefore, specific mutations in the CMV genes coding for UL54 DNA polymerase or UL97 protein kinase can confer resistance to approved therapies [29]. Maribavir has a multimodal mechanism of action [16–18], does not require intracellular processing by UL97 protein kinase [30], and targets a different location on UL97 from valganciclovir/ganciclovir. Due to its unique mechanism of action, maribavir remains active against CMV strains resistant to ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir due to UL54 or UL97 viral kinase mutations [20, 21]. Therefore, maribavir may be well positioned to satisfy the high unmet need associated with resistant CMV infections. As maribavir directly inhibits UL97 protein kinase, maribavir cannot be co-administered with valganciclovir/ganciclovir.

Maribavir was previously investigated for CMV prophylaxis, with prior phase 3 studies showing that the treatment (administered at 100 mg BID) failed to prevent CMV disease in transplant recipients [31–33]. However, findings from the current phase 3 and phase 2 studies [22, 23] using a higher maribavir dose (400 mg BID) all show maribavir efficacy in clearing CMV viremia among transplant recipients with CMV infection.

Currently, there is no consensus on a CMV viral load cutoff for initiation of therapy [12, 34, 35]; while the CMV DNA cutoff for study inclusion may have excluded some patients, this threshold was selected following discussions with regulatory authorities and in careful consideration towards including patients with clinically significant CMV viremia.

The current study has limitations, including an open-label design, which may have introduced bias. Blinding was not feasible due to the need for individualized IAT drug selection/dosing adjustments and the different routes of treatment administration for IAT compared with maribavir. While this study was designed to include pediatric patients aged 12 years and older, no pediatric patients were enrolled. The benefit of maribavir over IAT was consistent across key subpopulations, including a numerically greater response in patients with refractory CMV without genotyped resistance. However, this study was not powered to detect differences between treatments in this patient subgroup. Further, as patients were not stratified by refractory or resistant CMV at randomization, more patients with refractory-only CMV were included in the maribavir group. Nevertheless, a numerical trend for maribavir versus IAT was observed for this patient subgroup, in alignment with overall study results. A higher study discontinuation rate before week 8 in the IAT group was also observed in the study. These discontinuations were primarily due to adverse events and toxicities known to be associated with available anti-CMV agents. Sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table 3) were performed to address this potential bias. Finally, the study-specified treatment duration may have necessitated patients with residual CMV at the end of the 8-week treatment phase to receive an alternative treatment during the follow-up phase and who were therefore considered nonresponders to the key secondary endpoint.

In conclusion, maribavir was superior to IAT with respect to CMV clearance in transplant recipients with R/R CMV infection, and sensitivity analyses demonstrated that a benefit of maribavir over IAT with respect to CMV clearance at week 8 was observed regardless of early discontinuations or the need for alternative treatment. Maribavir demonstrated an improved safety profile versus valganciclovir/ganciclovir with respect to neutropenia and versus foscarnet with respect to AKI, which are treatment-limiting toxicities frequently associated with these conventional therapies. Maribavir represents a promising treatment for R/R CMV infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author Contributions. All authors were involved in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Study conception and design: R. K. A., S. A., R. F. C., G. A. P., and J. W. Acquisition of data: S. A., B. D. A., E. A. B., R. F. C., D. F. F., D. K., F. P. S., O. W., M. F., J. W., A. K. S., C. C., R. F. D., and G. A. P. Analysis and interpretation of data: R. K. A., S. A., B. D. A., E. A. B., R. F. C., D. F. F., D. K., J. M., G. A. P., F. P. S., O. W., M. F., J. W., A. K. S., C. C., and R. F. D.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the patients, their families, and healthcare providers who participated in the trial. The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of their colleague, mentor, and friend, Dr. Francisco Marty (1968–2021). They also acknowledge the contributions of Arnaud Del Bello at CHU de Toulouse, France; Maryann Najdzinowicz at the University of Pennsylvania, USA; Jean-Philippe Rerolle at Dupuytren Hospital, France; Christine Robin and Ludovic Cabanne at Henri Mondor Hospital, France; as well as Javier Segovia-Cubero, Jose Portoles, and Piedad Ussetti at Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda, Spain. They also thank Obi Umeh (Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc) for his contributions to the trial design, interpretation of data, and for the critical review of a draft of the manuscript. Under the direction of the authors, Lola Parfitt, MRes, formerly of Caudex, Oxford, UK, and Jane Cheung, PhD, of Caudex, Toronto, ON, Canada, provided writing assistance (including the first draft) and coordination and collation of comments, and Michael Rowlands, PhD, of Caudex, London, UK, provided editorial assistance, funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc. The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participant’s data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months from initial request, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after their de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization.

Financial support. This work was supported by Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.

Contributor Information

Robin K Avery, Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Sophie Alain, Department of Virology and National Reference Center for Herpesviruses, Limoges University Hospital, UMR Inserm 1092, University of Limoges, Limoges, France.

Barbara D Alexander, Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Emily A Blumberg, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Roy F Chemaly, Department of Infectious Diseases, Infection Control, and Employee Health, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA.

Catherine Cordonnier, Haematology Department, Henri Mondor Hospital and University Paris-Est-Créteil, Créteil, France.

Rafael F Duarte, Department of Haematology, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain.

Diana F Florescu, Infectious Diseases Division, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Nassim Kamar, Department of Nephrology and Organ Transplantation, Toulouse Rangueil University Hospital, INFINITY-Inserm U1291-CNRS U5051, University Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France.

Deepali Kumar, Transplant Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Johan Maertens, Haematology Department, University Hospitals Leuven, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Francisco M Marty, Department of Infectious Disease, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Genovefa A Papanicolaou, Infectious Disease Service, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Fernanda P Silveira, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Pittsburgh and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Oliver Witzke, Department of Infectious Diseases, West German Centre of Infectious Diseases, University Medicine Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

Jingyang Wu, Biostatistics, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.

Aimee K Sundberg, Clinical Sciences, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.

Martha Fournier, Clinical Sciences, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- 1. Haidar G, Boeckh M, Singh N.. Cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplantation: state of the evidence. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:S23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Felipe CR, Ferreira AN, Bessa A, et al. . The current burden of cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplant recipients receiving no pharmacological prophylaxis. J Bras Nefrol 2017; 39:413–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teira P, Battiwalla M, Ramanathan M, et al. . Early cytomegalovirus reactivation remains associated with increased transplant-related mortality in the current era: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood 2016; 127:2427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beam E, Lesnick T, Kremers W, Kennedy CC, Razonable RR.. Cytomegalovirus disease is associated with higher all-cause mortality after lung transplantation despite extended antiviral prophylaxis. Clin Transplant 2016; 30:270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Avery RK, Arav-Boger R, Marr KA, et al. . Outcomes in transplant recipients treated with foscarnet for ganciclovir-resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infection. Transplantation 2016; 100:e74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher CE, Knudsen JL, Lease ED, et al. . Risk factors and outcomes of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vejrazkova E, Pliskova L, Hubacek P, et al. . Clinical and genotypic CMV drug resistance in HSCT recipients: a single center epidemiological and clinical data. Bone Marrow Transplant 2019; 54:146–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu J, Kong J, Chang YJ, et al. . Patients with refractory cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation are at high risk for CMV disease and non-relapse mortality. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21:1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonatti H, Sifri CD, Larcher C, Schneeberger S, Kotton C, Geltner C.. Use of cidofovir for cytomegalovirus disease refractory to ganciclovir in solid organ recipients. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017; 18(2):128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pierce B, Richardson CL, Lacloche L, Allen A, Ison MG.. Safety and efficacy of foscarnet for the management of ganciclovir-resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infections: a single-center study. Transpl Infect Dis 2018; 20:e12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khawaja F, Batista MV, El Haddad L, Chemaly RF.. Resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infections after hematopoietic cell transplantation: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2019; 32:565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Razonable RR, Humar A.. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients—Guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant 2019; 33:e13512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mehta Steinke SA, Alfares M, Valsamakis A, et al. . Outcomes of transplant recipients treated with cidofovir for resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infection. Transpl Infect Dis 2021;. 23:e13521. doi:10.1111/tid.13521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maffini E, Giaccone L, Festuccia M, Brunello L, Busca A, Bruno B.. Treatment of CMV infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Rev Hematol 2016; 9:585–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mavrakanas TA, Fournier MA, Clairoux S, et al. . Neutropenia in kidney and liver transplant recipients: risk factors and outcomes. Clin Transplant 2017; 31. doi:10.1111/ctr.13058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chou S, Marousek GI.. Accelerated evolution of maribavir resistance in a cytomegalovirus exonuclease domain II mutant. J Virol 2008; 82:246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krosky PM, Baek MC, Coen DM.. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein kinase, an antiviral drug target, is required at the stage of nuclear egress. J Virol 2003; 77:905–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prichard MN. Function of human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase in viral infection and its inhibition by maribavir. Rev Med Virol 2009; 19:215–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamirally S, Kamil JP, Ndassa-Colday YM, et al. . Viral mimicry of Cdc2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 mediates disruption of nuclear lamina during human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drew WL, Miner RC, Marousek GI, Chou S.. Maribavir sensitivity of cytomegalovirus isolates resistant to ganciclovir, cidofovir or foscarnet. J Clin Virol 2006; 37:124–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chou S, Wu J, Song K, Bo T.. Novel UL97 drug resistance mutations identified at baseline in a clinical trial of maribavir for resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infection. Antiviral Res 2019; 172:104616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Papanicolaou GA, Silveira FP, Langston AA, et al. . Maribavir for refractory or resistant cytomegalovirus infections in hematopoietic-cell or solid-organ transplant recipients: a randomized, dose-ranging, double-blind, phase 2 study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1255–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maertens J, Cordonnier C, Jaksch P, et al. . Maribavir for preemptive treatment of cytomegalovirus reactivation. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:1136–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C.. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:1094–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, et al. . Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant patients for use in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Natori Y, Alghamdi A, Tazari M, et al. . Use of viral load as a surrogate marker in clinical studies of cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:617–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song IH, Ilic K, Murphy J, Lasseter K, Martin P.. Effects of maribavir on P-glycoprotein and CYP2D6 in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2020; 60:96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koszalka GW, Johnson NW, Good SS, et al. . Preclinical and toxicology studies of 1263W94, a potent and selective inhibitor of human cytomegalovirus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46:2373–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. El Chaer F, Shah DP, Chemaly RF.. How I treat resistant cytomegalovirus infection in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Blood 2016; 128:2624–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Biron KK, Harvey RJ, Chamberlain SC, et al. . Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole L-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46:2365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marty FM, Ljungman P, Papanicolaou GA, et al. . Maribavir prophylaxis for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in recipients of allogeneic stem-cell transplants: a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:284–92. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70024-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winston DJ, Saliba F, Blumberg E, et al. . Efficacy and safety of maribavir dosed at 100 mg orally twice daily for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in liver transplant recipients: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter controlled trial. Am J Transplant 2012; 12:3021–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marty FM, Boeckh M.. Maribavir and human cytomegalovirus–what happened in the clinical trials and why might the drug have failed?. Curr Opin Virol 2011; 1:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM, et al. . The third international consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid-organ transplantation. Transplantation 2018; 102:900–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ljungman P, de la Camara R, Robin C, et al. . Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stem cell transplantation from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:e260–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.