Abstract

Soybean and maize are some of the main drivers of Brazilian agribusiness. However, biotic and abiotic factors are of great concern, causing huge grain yield and quality losses. Phosphorus (P) deficiency is important among the abiotic factors because most Brazilian soils have a highly P-fixing nature. Thus, large amounts of phosphate fertilizers are regularly applied to overcome the rapid precipitation of P. Searching for alternatives to improve the use of P by crops is essential to reduce the demand for P input. The use of multifunctional rhizobacteria can be considered one of these alternatives. In this sense, the objective of the present work was to select and validate bacterial strains with triple action (plant growth promoter, phosphate solubilizer, and biocontrol agent) in maize and soybean, aiming to develop a multifunctional microbial inoculant for Brazilian agriculture. Bacterial strains with high indole acetic acid (IAA) production, phosphate solubilization, and antifungal activity against soil pathogenic fungi (Rhizoctonia solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Fusarium solani) were selected from the maize rhizosphere. Then, they were evaluated as growth promoters in maize under greenhouse conditions. Based on this study, strain 03 (Ag75) was selected due to its high potential for increasing biomass (root and shoot) and shoot P content in maize. This strain was identified through genomic sequencing as Bacillus velezensis. In field experiments, the inoculation of this bacterium increased maize and soybean yields by 17.8 and 26.5%, respectively, compared to the control (25 kg P2O5). In addition, the inoculation results did not differ from the control with 84 kg P2O5, indicating that it is possible to reduce the application of phosphate in these crops. Thus, the Ag75 strain has great potential for developing a multifunctional microbial inoculant that combines the ability to solubilize phosphate, promote plant growth, and be a biocontrol agent for several phytopathogenic fungi.

Subject terms: Abiotic, Bacterial development

Introduction

Agribusiness is an essential sector of the Brazilian economy, representing 27.4% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and 40.6% (US$ 9.9 billion) of exports in 2021. Approximately 23% of foreign sales in this segment come from the soy complex (grain, meal, and oil) and 8% from maize1. In the 2021/2022 harvest, soybean was cultivated on approximately 40.8 million hectares, with a production of 122.2 million t and an average growth of 5.7 million t year−1 during the last 10 years. In turn, maize was cultivated on approximately 21.2 million hectares, had a production of 115 million tons, and had an average growth of 3.2 million t year−12.

Despite the positive scenario of soybean and maize in Brazil, biotic and abiotic factors generate great concerns, causing huge losses in grain yield and quality. Among the abiotic factors, nutritional deficiency is an important stressor because most tropical soils have high acidity, toxic levels of aluminum (Al), and low nutrient availability, especially phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N)3,4. In the case of P, most Brazilian soils are highly P-fixing soils, and large amounts of phosphate fertilizers are regularly applied to overcome the rapid precipitation of P by iron (Fe3+) and Al3+ ions3,5.

Approximately 60% of the inorganic P fertilizer used in Brazilian agriculture is currently imported, generating a high and unfavorable dependence considering geopolitical fluctuations and dollar volatility6. In this context, agricultural management strategies to improve P use efficiency by crops are essential to substantially reduce the demand for P input. Some strategies include increasing soil pH by liming, crop rotation, double cropping, cover crops between seasons, no-tillage, and the use of modern fertilizers. Other approaches involve developing P-use efficient cultivars and inoculating phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSM)5.

PSM can make P available to plants through several mechanisms, some more related to enzymatic processes (phytases and/or phosphatases) and others to cell physiology, with the extrusion of H+ ions and release of organic acids from microbial metabolism7–9. Furthermore, some of these microorganisms may have an effect as plant growth promoters and biocontrol agents against plant pathogens10–12.

Several strains of bacteria, actinobacteria, and fungi have been reported and investigated for their ability to solubilize phosphate. Among phosphate-solubilizing fungi (PSF), the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium are the most studied, while phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) include the genera Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter7,12. Some Bacillus strains are known to act as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) either through the solubilization of minerals such as phosphorus or the production of metabolites such as siderophores and phytohormones13. In addition, this genus contains excellent root colonizers, having members in the rhizosphere of a wide range of crops and can survive under many stress conditions and control various plant pathogens13,14.

The genus Bacillus has different tools for controlling phytopathogens, including competition with pathogens for ecological niches and nutrients, production of antimicrobial metabolites, and induction of resistance in the host plant15,16. Among the antimicrobial metabolites, Bacillus sp. can produce a wide range of antagonist compounds with different structures, having 5–8% of the genome dedicated to the biosynthesis of these secondary metabolites15. Non-ribosomal peptides and lipopeptides, polyketide compounds, bacteriocins, and siderophores are the main bioactive molecules controlling plant diseases16,17.

The present work aimed to select and validate bacterial strains with triple action (plant growth promoter, phosphate solubilizer, and biocontrol agent) in maize and soybean. The study has the final objective of developing a multifunctional microbial inoculant for Brazilian agriculture, as well as shedding light on the genomic mechanisms associated with these beneficial traits.

Results

Greenhouse experiment

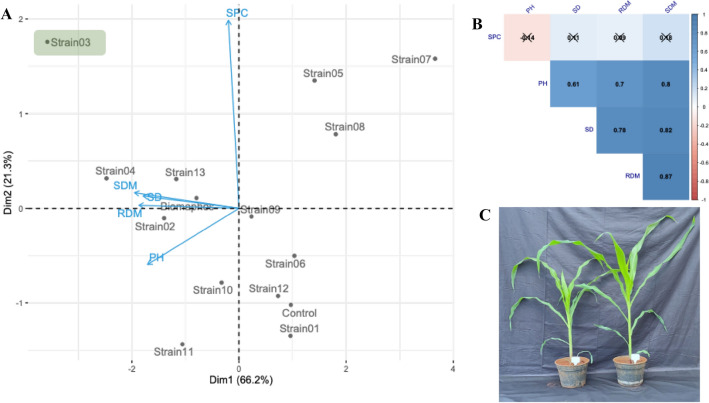

By the analysis of variance, a significant effect (p < 0.01) was observed for all the evaluated traits, indicating a wide variability between treatments (Table S3). For stem diameter (SD), the highest values were observed for the control, biomaphos, strain 02, strain 03, strain 04, strain 11, and strain 12 treatments, while for plant height (PH), the highest values were found in strain 02, strain 03, strain 04, strain 10, strain 11, strain 12, and strain 13 (Table S4). For root and shoot dry mass (RDM and SDM), seven and six strains, respectively, obtained higher values than the control, especially strains 03 and 04. For SPC, the treatments that stood out were strain 03, strain 04, strain 05, strain 07, strain 08, and strain 13.

The principal component analysis showed that the first two components explained 87.5% of the total variation (PCA1 and PCA2 with 66.2 and 21.3%, respectively) (Fig. 1A). PH, SD, RDM, and SDM had a high correlation with each other and did not correlate with SPC (Fig. 1B). Strain 03 stood out for all traits, with increments of 16, 45, 42, and 35% for PH, RDM, SDM, and SPC, respectively, in relation to the control (Fig. 1C). Based on these results, strain 03, which was called Ag75, was selected for further experiments.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (A) and Pearson correlation (B) between traits evaluated in the greenhouse experiment with maize seeds inoculated with different phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Comparison of the control treatment (without inoculation) with strain 03. SD stem diameter, PH plant height, RDM root dry mass, SDM shoot dry mass, SPC shoot phosphorus content.

Field experiments

Based on the analysis of variance, a significant effect of the environment and treatments (p < 0.01) was observed for grain yield in the maize and soybean experiments (Table 1). For both experiments, no significant effect of the treatment × environment interaction was observed. The coefficients of variation were 10.77 and 11.12 for the maize and soybean experiments, respectively, indicating good experimental precision.

Table 1.

Analysis of variance for grain yield in maize and soybean experiments with seeds inoculated with phosphate-solubilizing bacteria.

| Source of variation1/ | DF | Maize | DF | Soybean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean square | Mean square | |||

| rep/env | 18 | 435,164.4 | 16 | 36,016.4 |

| Environment (Env.) | 5 | 76,681,001.6** | 4 | 9,173,354.7** |

| Treatments (T) | 4 | 6,525,342.7** | 4 | 1,498,355.2** |

| Env. × T | 20 | 529,651.1ns | 16 | 197,868.4ns |

| error | 74 | 617,919.8 | 60 | 127,521.2 |

| CV (%) | 10.77 | 11.12 | ||

| Env.1 | 8939.23 | 2519.91 | ||

| Env.2 | 7024.80 | 2515.99 | ||

| Env.3 | 5497.00 | 4060.03 | ||

| Env.4 | 4996.57 | – | ||

| Env.5 | 10,101.20 | 3553.94 | ||

| Env.6 | 7236.21 | 3399.64 |

1/Env1.: Londrina (2020/2021), Env2.: Maringá (2020/2021), Env3.: Guarapuava (2020/2021), Env4.: Londrina (2021/2021), Env5.: Londrina (2021/2022) and Env6.: Guarapuava (2021/2022).

ns, ** and * indicates non-significance, significance at levels 1 and 5% of probability by the F test, respectively.

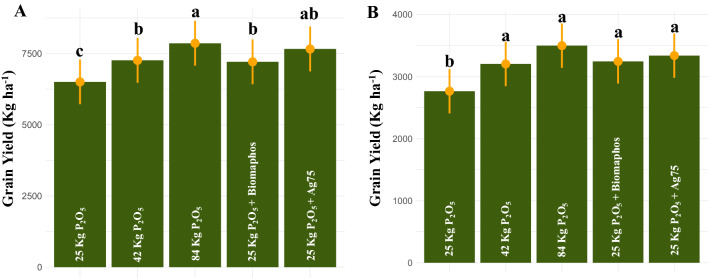

For the maize experiments, the average grain yield between environments ranged from 4996.57 (Londrina—2021/2021 off-season) to 10,101.20 kg ha−1 (Londrina—2021/2022 harvest) (Table S5). The control treatment—84 kg P2O5 had the highest average yield (7861.04 kg ha−1), not differing statistically from the Ag75 (7660.90 kg ha−1) and control—42 kg P2O5 (7260.58 kg ha−1) treatments (Fig. 2A). By unfolding the environments, the biological treatments (Biomaphos and Ag75) did not differ from the control—84 kg P2O5 in the evaluated environments, indicating the possibility of reducing the application of phosphate in maize. The inoculation of Ag75 allowed an average increase of 17.8% in grain yield in relation to the control—25 kg P2O5.

Figure 2.

Effect of phosphate solubilizing bacteria on grain yield in maize (A) and soybean (B) experiments.

For soybean, the average grain yield between environments ranged from 2519.91 (Londrina—2020/2021) to 4060.03 kg ha−1 (Guarapuava—2020/2021) (Table S6). The control treatment—25 kg P2O5 had the lowest productivity, and the Biomaphos, Ag75, control—42 kg P2O5, and control—84 kg P2O5 treatments did not differ from each other (Fig. 2B). These treatments obtained an average increase in grain yield of 15.8, 26.5, 17.4, and 20.8%, respectively, in relation to the control—25 kg P2O5.

For the phosphorus use efficiency indices, significant effects were observed for the environment (p < 0.01) for all variables, while for treatments, only PUtE_g was not significant (Table 2). For treatment × environment interactions, no significant effect was observed. The CV (%) ranged from 21.52 (PUpE_g) to 32.09 (PUE_g—maize). For PUpE_g, the highest values were observed for the biological treatments (Biomaphos and AgPhos), with increases of 23 and 42%, respectively, in relation to the control—25 kg P2O5. For PUsE_g, in the maize experiment, the highest values were observed for Ag75, Biomaphos, and the control—25 kg P2O5. For soybean, the highest PUsE values were found in Ag75 and Biomaphos, with increases of 19 and 29%, respectively.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance and Tukey’s test for phosphorus uptake efficiency (PUpE_g), phosphorus utilization efficiency (PUtE_g), and phosphorus use efficiency (PUsE_g) in maize and soybean experiments with seeds inoculated with phosphate-solubilizing bacteria.

| Source of variation1/ | DF | Maize – mean square | Soybean—mean square | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUpE_g | PUtE_g | PUsE_g | PUsE_g | ||

| rep/env | 9 | 0.02 | 65,497.1 | 80,434.7 | 4206.8 |

| Environment (Env.) | 2 | 0.82** | 10,236,391.6** | 1,152,283.1** | 31,648.3** |

| Treatments (T) | 4 | 0.67** | 81,158.5ns | 305,295.4** | 52,608.2** |

| Env. × T | 8 | 0.08ns | 186,044.6ns | 15,301.0ns | 1512.5ns |

| Error | 36 | 0.04 | 129,875.7 | 54,256.5 | 1822.7 |

| CV (%) | 21.57 | 26.56 | 32.09 | 29.30 | |

| Means | |||||

| 25 kg P2O5 | 0.66bc | 996.4a | 524.5ab | 165.1b | |

| 42 kg P2O5 | 0.56cd | 970.2a | 458.7b | 95.8c | |

| 84 kg P2O5 | 0.34d | 1107.6a | 332.1b | 58.4d | |

| 25 kg P2O5 + Biomaphos | 0.83ab | 877.2a | 681.1a | 196.6ab | |

| 25 kg P2O5 + Ag75 | 0.95a | 976.8a | 718.4a | 212.5a | |

ns, ** and * indicates non-significance, significance at levels 1 and 5% of probability by the F test, respectively.

Means followed by different letters on the same line differ significantly from each other as measured by the Tukey test at the significance level of 5%.

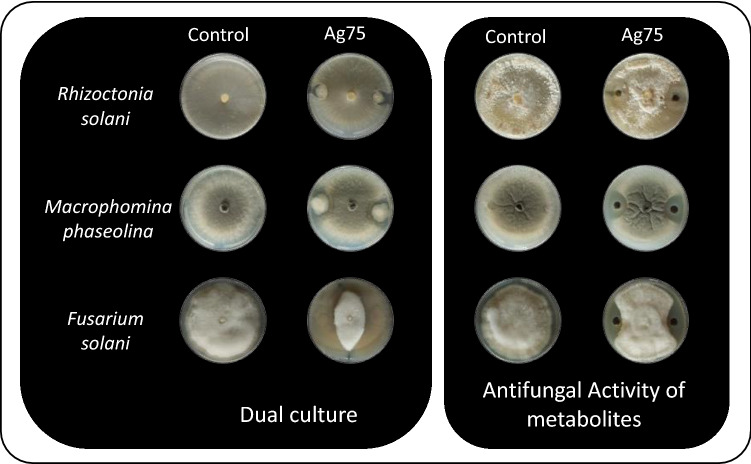

Antifungal activity

The Ag75 strain showed antifungal activity against Rhizoctonia solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Fusarium solani, with percent mycelial growth inhibition of 44, 49 and 61%, respectively, indicating antagonism of this strain against these fungi (Fig. 3). When analyzing the CFS against these fungi, mycelial growth inhibition percentages of 54 and 46% were observed for M. phaseolina and F. solani, respectively. For R. solani, inhibition with CFS was not observed.

Figure 3.

Mycelial growth inhibition of the fungi Rhizoctonia solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Fusarium solani using dual culture and cell-free supernatant of the Ag75 strain.

Assembly and annotation of the Ag 75 genome

The CLC Genomics Workbench 11 and IDBA Hybrid genome assembly strategies demonstrated the best results for assembly. A BLASTN search was performed using the largest contig to find a reference genome for the CONTIGuator step. The strain Bacillus velezensis NKG-1 was selected to align the contigs and generate pseudocontigs (scaffold). The scaffold contained 22 gaps that were first treated with GapCloser and then manually aligned using Bowtie2 and CLC Genomics Workbench 11. The genome of the Ag75 strain showed a 98.14% alignment rate of reads with a 3,980,135 bp size and a G+C average content of 46.5% (GenBank accession number CP099465; culture collection: CCT8089). A total of 4053 protein-coding genes, 24 rRNA genes, and 85 tRNA genes were found (Figure S1). Most of these genes are associated with functions such as amino acid transport and metabolism, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, transcription, inorganic ion transport and metabolism, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism.

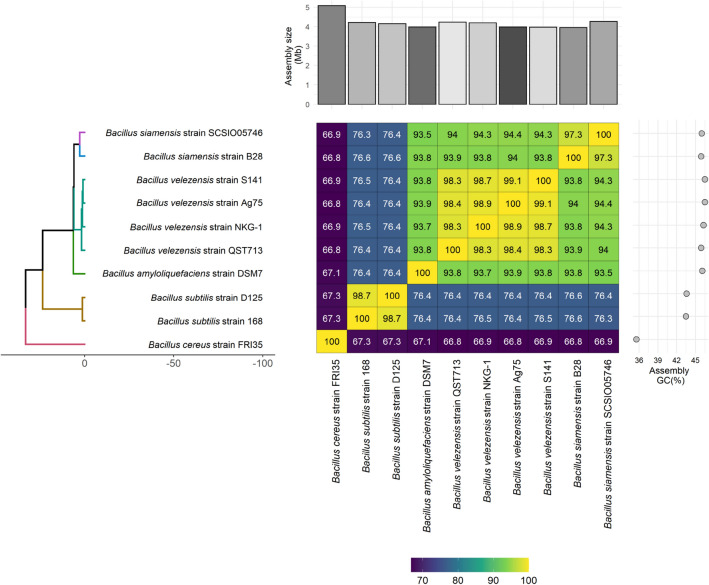

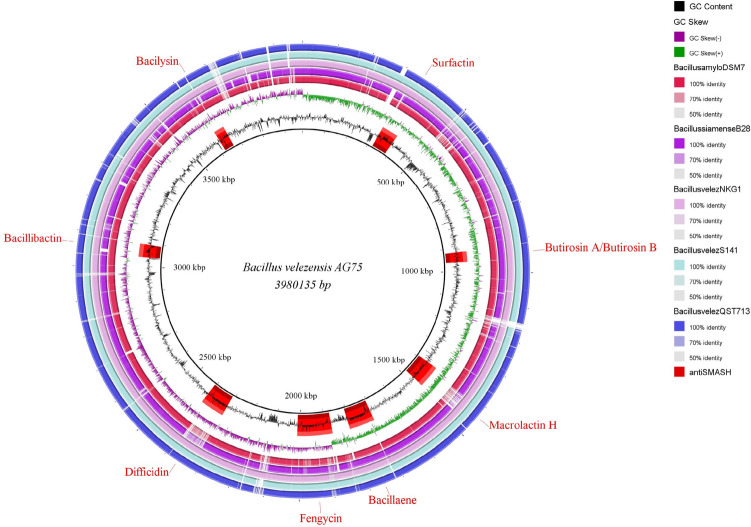

Comparing the Ag75 strain with the main species of the Bacillus subtilis group, the ANI and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) were higher with the isolates of Bacillus velezensis, with values ranging from 98.44 to 99.12% for ANI and 92.3 to 94.2% for dDDH. In the comparison performed with Gegenees and ortthoANI/GGDC, it was observed that the Ag75 strain is located within the cluster containing most species of Bacillus velezensis (Fig. 4). The circular genome of the Ag75 strain is represented in Fig. 5.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood analysis using 10 available genomic assemblies of Bacillus velezensis, Bacillus siamensis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus subtilis, and Bacillus cereus with heatmap annotation. The mean nucleotide identity (ANI) values (%) are displayed on the heatmap, ranging from lowest (violet) to highest sequence identity (green–yellow), grouped according to the phylogenetic tree. The heatmap was annotated with a bar graph showing the varying sizes (Mb) of all 10 assemblies (on the top) and their respective GC content (%) (right side).

Figure 5.

Circular representation of the genome of Bacillus velezensis strain Ag75 using the BRIG program. From inside to outside, the legends are as follows: GC content, GC slope, and position of BGCs in the genome indicated by antiSMASH for DSM7, B28, NKG-1, S141, and QST 713.

AntiSMASH analysis of secondary metabolites

Using the antiSMASH 5.1.0 webserver, 12 clusters of BGCs were identified in the genome of Ag75 (Table S7). Of these, six clusters showed 100% similarity and were linked to the synthesis of macrolactin, bacillaene, fengycin, difficidin, bacillibactin, and bacilisyn. One cluster had 82% similarity, responsible for surfactin, and another had 7% similarity, responsible for butyrosine A and B synthesis. Four clusters showed no similarity with the database.

Genetic basis for plant growth-promoting to activities

A number of genes/gene groups associated with plant growth promotion were identified in the Ag75 genome, including production of volatile compounds, phytohormone promoters and phosphatases related to P solubilization (Tables 3, 4). They include 10 putative genes involved in the production of indole-3-acetic acid. In addition, putative genes encoded cytochrome P450 synthase and spermidine acetyltransferase, which are predicted to produce spermidine and polyamine. Other genes encoding proteins involved in the production glucose dehydrogenase, phenazine, trehalose, heat and cold shock, glycine-betaine, and peroxidases, were present. The Ag75 genome has 10 genes involved in the process of biofilm development and regulation and 11 phosphatase genes involved in phosphate solubilization.

Table 3.

Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to be involved in plant growth-promoting activity.

| Gene ID | Gene name | Protein coded by the gene |

|---|---|---|

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in the production of indole acetic acid (IAA) | ||

| AG75_002206 | trpA | Tryptophan synthase subunit alpha |

| AG75_002207 | trpB | Tryptophan synthase subunit beta |

| AG75_002209 | trpC | Indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase TrpC |

| AG75_002210 | trpD | Anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase |

| AG75_002211 | trpE | Anthranilate synthase component I |

| AG75_002208 | trpF | Phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase |

| AG75_002829 | ywdH | Aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| AG75_000692 | ysnE | GNAT family N-acetyltransferase |

| AG75_003625 | ywkB | Auxin efflux carrier family protein |

| AG75_000284 | amhX | Amidohydrolase |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in the production spermidine and polyamine | ||

| AG75_001904 | bioI | Biotin biosynthesis cytochrome P450 |

| AG75_003671 | speE | Spermidine synthase |

| AG75_000568 | bltD | Spermidine acetyltransferas |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in the production volatile compound (VOC) | ||

| AG75_003512 | budA | Acetolactate decarboxylase |

| AG75_003513 | AlsS | Acetolactate synthase |

| AG75_003514 | alsR | Transcriptional regulator |

| AG75_00627 | bdhA | 2,3-Butanediol dehydrogenase |

| AG75_00798 | acoA | Acetoin dehydrogenase |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in biofilm formation, development, and regulation | ||

| AG75_001543 | ylbF | Controls biofilm development |

| AG75_001749 | ymcA | Biofilm development |

| AG75_003250 | ioIW | Scyllo-inositol 2-dehydrogenase (NADP(1) involved in biofilm formation protein |

| AG75_001694 | sigD | RNA polymerase sigma factor for flagellar operon and Biofilm formation |

| AG75_002430 | sinR | Master regulator of biofilm formation |

| AG75_002934 | luxS | S-Ribosyl homocysteine lyase for Quorum sensing Biofilm formation |

| AG75_003332 | rpoN | RNA polymerase sigma-54 factor for Biofilm formation |

| AG75_003444 | csrA | Carbon storage regulator for Biofilm formation |

| AG75_003450 | flgM | Negative regulator of flagellin synthesis flgmfor Biofilm formation |

| AG75_003473 | wecB | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase for Biofilm formation |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved to Glucose dehydrogenase | ||

| AG75_000268 | ycdF | Glucose 1-dehydrogenase |

| AG75_000391 | gdh | Glucose 1-dehydrogenase |

| AG75_002348 | zwf | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| AG75_003465 | tuaD | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in Phenazine production and Trehalose metabolism | ||

| AG75_000825 | phzF | PhzF family phenazine biosynthesis isomerase |

| AG75_000762 | treP | PTS system trehalose-specific EIIBC component |

| AG75_000764 | treR | Trehalose operon repressor |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in heat and cold shock | ||

| AG75_000061 | hslR | Ribosomal RNA binding protein involved in 50S recycling heat shock protein |

| AG75_000609 | GroeL | Heat shock protein 60 kDa family chaperone GroEL |

| AG75_000608 | GroeS | Heat shock protein 10 kDa family chaperone GroES |

| AG75_000504 | cspC | Cold shock protein CspC |

| AG75_000897 | cspB | Cold shock-like protein CspB |

| AG75_002124 | cspD | Cold-shock protein CspD |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved in Glycine-betaine production | ||

| AG75_000281 | opuAA | Glycine/proline betaine ABC transporter ATP-binding protein OpuAA |

| AG75_000282 | opuAB | Glycine/proline betaine ABC transporter permease subunit OpuAB |

| AG75_000283 | opuAC | Glycine/betaine ABC transporter |

| AG75_002884 | opuD | Glycine betaine transporter OpuD |

| Genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to involved to Peroxidases | ||

| AG75_002120 | bsaA | Glutathione peroxidase |

| AG75_000854 | bcp | Thiol peroxidase |

Table 4.

Phosphatase genes detected in Bacillus velezensis Ag75 genome predicated to be involved in phosphorus solubilization.

| Gene ID | Gene name | Protein coded by the gene |

|---|---|---|

| AG75_000252 | phoD | Phosphodiesterase/alkaline phosphatase D |

| AG75_000402 | ycsE | Phosphatase YcsE |

| AG75_000476 | RsbU | Serine phosphatase RsbU, regulator of sigma subunit |

| AG75_000480 | rsbX | Phosphoserine phosphatase RsbX |

| AG75_000776 | NG74_RS03905 | Low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase |

| AG75_001088 | yitU | Putative phosphatase YitU |

| AG75_000928 | PhoA | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AG75_001511 | suhB | Inositol-1-monophosphatase |

| AG75_001622 | prpC | Protein serine/threonine phosphatase PrpC, regulation of stationary phase |

| AG75_002780 | phoP | Alkaline phosphatase synthesis transcriptional regulatory protein PhoP |

| AG75_002053 | phyC | 3-Phytase |

Discussion

The world faces a major challenge in developing sustainable and eco-friendly methods to improve agricultural productivity. In this sense, great efforts have been made to discover new PGPR to generate microbial inoculants for agriculture. PGPR have multiple mechanisms of action, including increasing soil nutrient availability, regulating microbial communities in the rhizosphere, increasing the proportion of beneficial microorganisms for plants, and producing phytohormones and volatile compounds that promote root growth. Moreover, they act by increasing nutrient absorption, controlling phytopathogens through the production of antimicrobial metabolites and volatile compounds, triggering an induced systemic response in plants, and inducing tolerance to abiotic stresses in plants15,17,18. In this context, the search for multifunctional strains with multiple effects of growth promotion, phosphate solubilization, and biocontrol has become essential to developing more effective inoculants for plant development. To this end, we selected multifunctional bacteria from the maize rhizosphere and inferred the potential for application of these strains to obtain a biological product capable of increasing P uptake efficiency, promoting the growth of maize and soybean plants, and acting as a biocontrol agent for the main soil phytopathogenic fungi.

For that, strains of Bacillus sp. from the bank of microorganisms with high IAA production, phosphate solubilization, and antifungal activity were selected. IAA plays an important role in root development, mainly in root hair and lateral root formation, improving water and nutrient absorption19. In this context, strains with phosphate solubilizing capacity and with high IAA production may increase the area of nutrient uptake and thus enhance the strain's performance in phosphate solubilization. Kudoyarova et al. found that the Paenibacillus illinoisensis IB 1087 and Pseudomonas extremeustralis IB-ki-13-1A strains selected based on IAA production and phosphate solubilization contributed positively to the development of the wheat root system, favoring greater accumulation of plant biomass and phosphorus20. In the present study, seven of the 13 strains evaluated in the greenhouse increased the root system compared to the control. However, no correlation was observed with shoot P content, indicating the complexity of these bacterial × host × environment interaction mechanisms.

Based on the greenhouse study, strain 03 (Ag75) showed a high potential for increasing (root and shoot) biomass and shoot P content in maize. Furthermore, this strain showed antifungal activity against the main soil fungi (R. solani, M. phaseolina, and F. solani), indicating that it is a promising strain for the development of a multifunctional microbial inoculant. By genomic analysis, Ag75 was identified as Bacillus velezensis. This species is frequently isolated from different niches (soil, water, rhizosphere, fermented foods, among others), being considered a species adapted to the host and of high economic importance due to its ability to promote plant growth and biocontrol in several economically important crops21–24. For example, the FZB42 isolate has already been published in over 140 articles and is related to growth promotion and the identification of antimicrobial compounds responsible for biocontrol. This information is deposited in the ‘AmyloWiki’ database (http://amylowiki.top/)25.

For strain Ag75, cyclic lipopeptides (surfactin and fengycin) were identified, which have an important antagonistic effect on several fungal and bacterial pathogens, stimulating plant defense mechanisms and biofilm formation—a key factor for successful colonization of biological control agents17,26,27. Another large class of non-ribosomal peptides identified were polyketides (difficidin, bacillaene, and macrolactin), which also play a role in antimicrobial activity15,17,28.

In Ag75, the metabolite bacillibactin, an important siderophore, was also identified29. This siderophore is highly conserved in the B. subtilis group and is induced in response to iron limitation in the environment. It allows Bacillus to acquire Fe3+ and other metals efficiently, thus depriving plant pathogens of this essential element30,31. Four of the 12 clusters identified in this strain did not show similarity in the database, and therefore, their products have not yet been identified and described, opening opportunities for further studies.

In addition to producing antimicrobial metabolites, the genome of Ag75 has genes related to plant growth promotion and phosphate solubilization activity. For instance, several identified genes are functionally linked to auxin synthesis and play important roles in the strain’s ability to stimulate plant development24,32. In addition, the identified genes related to spermidine and polyamine production are suggested to participate in plant development and growth promotion, involving the production of active metabolites such as steroids, vitamin D3, cholesterol, cytokinin, statins, and terpenes24. Ag75 has several phosphatase genes related to phosphorus solubilization, including phytase, which is a particular class of phosphatases capable of mineralizing organic P from phytate and related P organic sources8,33. Other studies also verified the presence of phosphatase genes in strains of Bacillus velezensis24,34,35.

These mechanisms of P solubilization and mineralization combined with those related to promoting root system development favored an increase in P uptake and P use efficiency in maize and soybean when compared to the control without inoculation. Furthermore, these effects were reflected in higher yield increases (17.8% for maize and 26.5% for soybean) in relation to the control 25 kg P2O5 and did not differ from the control 84 kg P2O5. Therefore, these results indicate the possibility of reducing phosphate application in these crops. For phosphate solubilization, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa) in partnership with the company Bioma developed an inoculant (Biomaphos) for this purpose. This product is composed of two strains (B. megaterium CNPMS B119 and B. subtilis CNPMS B2084). Based on the studies by Paiva et al. this inoculant increased maize yield by 8.9%, which is corroborated by the present study with an average increase of 10.8% 36.

Brazil has a long history of research on rhizobia and PGPR in various crops. Currently, the use of these products by farmers is a reality, allowing an optimization of mineral fertilizers and contributing to sustainable and low-cost agriculture37. Thus, the Ag75 strain has great potential for the development of a multifunctional microbial inoculant that combines the ability to solubilize phosphate, promote plant growth, and act as a biocontrol agent for several phytopathogenic fungi.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain

Thirteen strains of Bacillus sp. from the microorganism bank of the AgBio company were used for this study. These strains were isolated from maize rhizospheric soil collected in the municipality of Italva, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and selected based on the screening performed for indole acetic acid (IAA) production, phosphate solubilization, and antifungal activity against soil pathogenic fungi (Rhizoctonia solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Fusarium solani).

Bacterial strain preparation

Strains stored at − 80 °C in cryovials containing liquid TSB and glycerol in a 2:1 ratio were activated in Petri dishes containing LBA (Luria Bertani Agar, Neogen Corporation, United States) culture medium at 28 °C for 24 h. A pre-inoculum of each strain was prepared from pure colonies suspended in saline solution (0.85% sodium chloride). The turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 standard on the McFarland nephelometric scale (1.5 × 108 CFU mL−1). Thirty microliters of these bacterial suspensions were transferred to 125 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 mL of AgO2 culture medium (g L−1: glucose 15.0, sucrose 10.0, yeast extract 10.0, micronized soy protein 10.0, KH2PO4 1.5, MgSO4 0.5, MnSO4 0.5, and CaCl2 1.5, pH 8.0) and incubated at 30 °C for 18–20 h at 200 rpm in an orbital shaker incubator (Orbital shaker Nova Tecnica—NT 735, Brazil) for inoculum production. For fermentation, 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 mL of AgO2 culture medium were inoculated with a 4 mL aliquot of the inoculum and incubated at 30 °C for 72 h at 200 rpm. After fermentation, the production concentration was adjusted to 2.0 × 109 CFU mL−1.

Greenhouse experiment

Maize seeds of the cultivar P3340VYHR (Corteva®) were inoculated with the bacterial strains at 2 × 109 CFU mL−1, constituting 13 treatments. Biomaphos® (Bacillus subtilis strain CNPMS B2084 and Bacillus megaterium strain CNPMS B119) and untreated seeds were used as controls. For treatments inoculated with biological products, a dose of 100 mL/60,000 seeds was used.

The seeds were sown in 5-L pots containing sand:soil:manure (3:1:1), and the experiment was performed in a greenhouse at Londrina State University (UEL). The physical–chemical analysis of this mixture is shown in Table S1. The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design with six repetitions. The treatments were irrigated every 2 days, and the plants were removed 45 days after sowing. The traits evaluated were (1) stem diameter, (2) plant height, (3) shoot dry mass, (4) root dry mass, and (5) shoot phosphorus content. To determine the shoot P content, the samples were dried in an oven at 70 °C for 72 h and ground in a Willey MA340 knife mill (Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil). Then, 0.1 g aliquots were digested in nitroperchloric solution (HNO3:HClO4) according to Malavolta et al.38. The P content was determined by the molybdenum blue spectrophotometric method39, and the readings were performed in an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, California, USA) at a wavelength of 660 nm.

Experiment under field conditions

For the tests under field conditions, maize P3340VYHR (Corteva®) and soybean Credenz Result I2X (BASF®) were used. The seeds were treated with the biological products Ag75 and Biomaphos® in plastic bags using a dose of 100 mL/60,000 seeds for maize and 100 mL/50 kg seeds for soybean. Uninoculated seeds and three doses of P in the soil (25 kg P2O5, 42 kg P2O5, and 84 kg P2O5) were used as controls.

For the maize experiments, six trials were carried out: (1) Londrina (2020/2021 harvest), (2) Maringá (2020/2021 harvest), (3) Guarapuava (2020/2021 harvest), (4) Londrina (2021 harvest), (5) Londrina (2021/2022 harvest), and (6) Guarapuava (2021/2022 harvest). For soybean, five trials were conducted: (1) Londrina (2020/2021 harvest), (2) Maringá (2020/2021 harvest), (3) Guarapuava (2020/2021 harvest), (4) Londrina (2021/2022 harvest), and (5) Guarapuava (2021/2022 harvest). The physical–chemical analyses of the soils and other characteristics related to the evaluation sites are presented in Table S2.

The experiment was conducted using the complete randomized block design with four repetitions. The plots consisted of eight 6-m rows spaced 0.45 m apart with five plants per meter. Before setting up the experiment, the areas of the maize experiments were fertilized with 25 kg P2O5 ha−1, 60 kg K2O ha−1, and 21 kg N ha−1, while the soybean areas were fertilized with 25 kg P2O5 ha−1 and 60 kg K2O ha−1. The amounts of P2O5 applied in the experiments were considered 30% of the standard phosphate fertilization recommended for these crops. Topdressing fertilization in maize was carried out with 120 kg N ha−1 applied at the V6 development stage.

Five representative plants from each experimental plot were collected at the physiological maturation stage. To determine the P content in grains (maize and soybeans) and shoots (maize), the same methodology described in the previous section was used.

Grain yield (kg ha−1) was obtained after harvesting plants from the six central rows of each plot. The components of P use efficiency (PUsE) were determined according to Moll et al. for maize, while for soybean, grain P content was determined. P uptake efficiency (PUpE, in g of absorbed P per g of applied P) was calculated by the ratio between total plant P and P available to the plant 40. P utilization efficiency (PUtE, in g of grains produced per g of total P in the plant) was determined by the ratio between the grain dry biomass and the amount of total P in the plant. PUsE (in g of grains produced per g of applied P) was calculated by the product of PUpE and PUtE.

Antagonism assay and metabolite evaluation

The Ag75 strain was activated in LBA (Acumedia, USA) at 28 °C for 24 h. For the antagonism test, this strain was inoculated on the edge of the plate containing PDA medium using a bacteriological loop. Then, a 6-mm diameter mycelial disc of the phytopathogenic fungus (Rhizoctonia solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Fusarium solani) was inoculated in the center of the plate. Then, the plates were incubated at 25 °C with a 12/12 h photoperiod. Plates with only the phytopathogenic fungus were used as controls. After 3 days for R. solani or 7 days for the fungi M. phaseolina and F. solani, according to the growth rate of each phytopathogenic fungus, mycelial growth in millimeters was evaluated. The percent mycelial growth inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

where ‘MGI’ represents the percentage of mycelial growth inhibition, ‘dc’ is the mean colony diameter in the control and ‘dt’ is the mean colony diameter for each treatment, all measured in mm41.

For cell-free supernatant activity, pure colonies were suspended in saline solution (0.85% sodium chloride) and adjusted to 0.5 on the McFarland scale. To prepare the inoculum, 30 µL of this suspension was transferred to 125 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 mL of LB medium and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h at 125 rpm (Orbital shaker Nova Tecnica—NT 735, Brazil). For the production of antifungal metabolites, aliquots of 1% (v:v) of each inoculum were transferred to 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 mL of AgO2 medium and incubated at 28 °C and 200 rpm in a shaker incubator in a random arrangement for 72 h. After the production step, the cultures were centrifuged at 4 °C and 9000 rpm for 10 min and filtered through 0.22 µm membranes to obtain cell-free supernatant (CFS). Subsequently, mycelial growth was evaluated in millimeters as described above. At the edge of the plate, two wells with 6 mm diameters were made equidistantly, and 200 μL of CFS was deposited in the wells. The plates were incubated at 25 °C with a 12/12 h photoperiod. As a control, plates with only the phytopathogenic fungus were used. After 3 days for R. solani or 7 days for the fungi M. phaseolina and F. solani, according to the growth rate of each phytopathogenic fungus, the diameter of the fungal colony was determined, and the percentage of mycelial growth inhibition was calculated.

Genomic sequencing and gene prediction

For complete genome sequencing, Ag75 was grown in LB at 150 rpm and 28 °C for 48 h. DNA extraction was performed using a PureLinkTM Microbiome DNA Purification kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The integrity of the DNA was verified using a 1% agarose gel, and the DNA was quantified by spectrophotometry in a NanoDrop 2000/2000c (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware, USA). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform at the Institute for Cancer Research (IPEC), Guarapuava, Paraná, Brazil.

The quality of the reads and the cutoff parameters were observed and chosen using FastQC42. Then, with the Trimmomatic program43, the raw reads were filtered based on the parameters defined by FastQC. Finally, new analyses regarding the quality of the reads were performed after the filters to check if the chosen parameters were adequate.

A series of de novo assemblies were performed with different software (SPAdes and IDBA hybrid)44, testing diverse assembly parameters. Then, the results were compared with each other with the QUAST program45. Key metrics, such as total alignment size, number of contigs, highest contig, N50 values, and gene numbers (according to the reference genome provided in QUAST), were used to choose the best assembly. Using the Contiguator webserver46, best-assembled contigs were aligned with the Bacillus velezensis NKG-1 reference genome to generate the scaffolds. Gaps were manually filled, mapping reads with Bowtie2 and filling gaps using CLC Genomics Workbench 12 GUI47. The genome start point was determined by comparison with a reference strain genome, assuming the dnaA gene as the first gene.

The genome of the Ag75 strain was represented circularly and compared with other reference genomes using BRIG (BLAST Ring Image Generator). To determine the species, the values of ANI (average nucleotide identity) were verified with other species of Bacillus spp. using OrthoANI48. The orthoANI matrix data and information generated by the software were exported and used to create the heatmap in the R program using the ggplot2 package. The hierarchical cluster analysis used was UPGMA.

RAST software was used to predict genes related to plant growth promotion. The identified ORFs (Open Reading Frame) were submitted to functional annotation, based on the search for similarity against the Genbank non-redundant protein (nr) database, using the Blastx algorithm, with an e-value of 1.0e−3, and annotation of the Gene Ontology ontology terms, using the Blast2Go v2.5.0 software49. The identification of possible biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) was performed using the antiSMASH 4.0 web server50, which combines different genetic databases, antimicrobial molecules, and BGCs to predict the position and possible function of the clusters51.

Data analysis

The agronomic data were subjected to analysis of variance, and if the assumptions were met, they were subjected to cluster analysis of Scott–Knott mean (greenhouse trials) and Tukey mean comparison test (field trials). In addition, the greenhouse data were subjected to correlation and principal component analyses. These analyses were performed by the R program using the AgroR52 and FactoMineR53 packages.

Experimental research and field studies on plants including the collection of plant material

The authors declare that the cultivation of plants and carrying out study in Universidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL), Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM) and Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste (UNICENTRO) complies with all relevant institutional, national and international guidelines and treaties.

Statement of permissions and/or licenses for collection of plant or seed specimens

The authors declare that the seed specimens used in this study are publicly accessible seed materials and we were given explicit written permission to use them for this research.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.M., G.A., and L.S.A.G.; data curation: M.M., L.R.M., S.R.A.A., A.F.N., R.B.L.M., and D.M.Z.; formal analysis: D.M.Z., G.D.Z., G.M.T., K.S.B., and L.S.A.G.; investigation: M.M., L.R.M., S.R.A.A., A.F.N., R.B.L.F., S.M., A.Y.H., and R.M.G.; methodology: M.M., A.F.N., D.M.Z., S.M., and A.Y.H.; project administration: G.A., M.V.F., R.M.G., C.A.S., and L.S.A.G.; resources: L.S.A.G.; supervision: G.A., M.V.F., R.M.G., C.A.S., and L.S.A.G.; writing (original draft): M.M., and L.S.A.G.; writing (review and editing): G.A., M.V.F., R.M.G., C.A.S., and L.S.A.G.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from L.S.A.G on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-19515-8.

References

- 1.Agrostat. Estatísticas de Comércio Exterior do Agronegócio Brasileiro. Exportação e importação. https://indicadores.agricultura.gov.br/agrostat/index.htm (2021).

- 2.CONAB. Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. Acompanhamento da safra brasileira de grãos. http://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/graos (2022).

- 3.Roy ED, et al. The phosphorus cost of agricultural intensification in the tropics. Nat. Plants. 2016;2:16043. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Withers PJA, et al. Transitions to sustainable management of phosphorus in Brazilian agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20887-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavinato PS, et al. Revealing soil legacy phosphorus to promote sustainable agriculture in Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:15615. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anda. Associação Nacional para Difusão de Adubos. Indicadores—Fertilizantes entregues ao mercado. . https://anda.org.br (2022).

- 7.Prabhu N, Borkar S, Garg S. Advances in Biological Science Research. Elsevier; 2019. Phosphate solubilization by microorganisms; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castagno LN, Sannazzaro AI, Gonzalez ME, Pieckenstain FL, Estrella MJ. Phosphobacteria as key actors to overcome phosphorus deficiency in plants. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021;178:256–267. doi: 10.1111/aab.12673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raymond NS, et al. Phosphate-solubilising microorganisms for improved crop productivity: A critical assessment. New Phytol. 2021;229:1268–1277. doi: 10.1111/nph.16924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alori ET, Glick BR, Babalola OO. Microbial phosphorus solubilization and its potential for use in sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:25. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billah M, et al. Phosphorus and phosphate solubilizing bacteria: Keys for sustainable agriculture. Geomicrobiol J. 2019;36:904–916. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2019.1654043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawat P, Das S, Shankhdhar D, Shankhdhar SC. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms: Mechanism and their role in phosphate solubilization and uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021;21:49–68. doi: 10.1007/s42729-020-00342-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miljaković D, Marinković J, Balešević-Tubić S. The significance of Bacillus spp. in disease suppression and growth promotion of field and vegetable crops. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1037. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8071037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena AK, Kumar M, Chakdar H, Anuroopa N, Bagyaraj DJ. Bacillus species in soil as a natural resource for plant health and nutrition. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020;128:1583–1594. doi: 10.1111/jam.14506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fira D, Dimkić I, Berić T, Lozo J, Stanković S. Biological control of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. J. Biotechnol. 2018;285:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimkić I, Janakiev T, Petrović M, Degrassi G, Fira D. Plant-associated Bacillus and Pseudomonas antimicrobial activities in plant disease suppression via biological control mechanisms - A review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022;117:101754. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo L, Zhao C, Wang E, Raza A, Yin C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as an excellent agent for biofertilizer and biocontrol in agriculture: An overview for its mechanisms. Microbiol. Res. 2022;259:127016. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2022.127016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fatima F, Ahmad MM, Verma SR, Pathak N. Relevance of phosphate solubilizing microbes in sustainable crop production: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13762-021-03425-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichmann R, Richards L, Schäfer P. Hormones as go-betweens in plant microbiome assembly. Plant J. 2021;105:518–541. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudoyarova GR, et al. Effect of auxin producing and phosphate solubilizing bacteria on mobility of soil phosphorus, growth rate, and P acquisition by wheat plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017;39:253. doi: 10.1007/s11738-017-2556-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheffi Azabou M, et al. The endophytic strain Bacillus velezensis OEE1: An efficient biocontrol agent against Verticillium wilt of olive and a potential plant growth promoting bacteria. Biol. Control. 2020;142:25. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alenezi FN, et al. Bacillus velezensis: A treasure house of bioactive compounds of medicinal, biocontrol and environmental importance. Forests. 2021;2:1714. doi: 10.3390/f12121714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira GM, et al. Genomic insights into the antifungal activity and plant growth-promoting ability in Bacillus velezensis CMRP 4490. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11:25. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.618415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaid DS, Cai S, Hu C, Li Z, Li Y. Comparative genome analysis reveals phylogenetic identity of Bacillus velezensis HNA3 and genomic insights into its plant growth promotion and biocontrol effects. Microbiol. Spectrum. 2022;10:14. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02169-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan B, et al. Bacillus velezensis FZB42 in 2018: The gram-positive model strain for plant growth promotion and biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:25. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao H, et al. Biological activity of lipopeptides from Bacillus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;101:5951–5960. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penha RO, Vandenberghe LPS, Faulds C, Soccol VT, Soccol CR. Bacillus lipopeptides as powerful pest control agents for a more sustainable and healthy agriculture: Recent studies and innovations. Planta. 2020;251:70. doi: 10.1007/s00425-020-03357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caulier S, et al. Overview of the antimicrobial compounds produced by members of the Bacillus subtilis group. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:45. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miethke M, et al. Ferri-bacillibactin uptake and hydrolysis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1413–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niehus R, Picot A, Oliveira NM, Mitri S, Foster KR. The evolution of siderophore production as a competitive trait. Evolution (N Y) 2017;71:1443–1455. doi: 10.1111/evo.13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrić S, Meyer T, Ongena M. Bacillus responses to plant-associated fungal and bacterial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talboys PJ, Owen DW, Healey JR, Withers PJ, Jones DL. Auxin secretion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 both stimulates root exudation and limits phosphorus uptake in Triticum aestivium. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh B, et al. Contribution of microbial phytases to the improvement of plant growth and nutrition: A review. Pedosphere. 2020;30:295–313. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(20)60010-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwangbo K, et al. Complete GENOME SEQUENCE of Bacillus velezensis CBMB205, a phosphate-solubilizing bacterium isolated from the rhizoplane of rice in the Republic of Korea. Genome Announc. 2016;4:24. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00654-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Shi H, Heng J, Wang D, Bian K. Antimicrobial, plant growth-promoting and genomic properties of the peanut endophyte Bacillus velezensis LDO2. Microbiol. Res. 2019;218:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paiva, C. A. O., et al. Recomendação agronômica de cepas de Bacillus subtilis (CNPMS B2084) e Bacillus megeterium (CNPMS B119) na cultura do milho.

- 37.Bomfim CA, et al. Brief history of biofertilizers in Brazil: From conventional approaches to new biotechnological solutions. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021;52:2215–2232. doi: 10.1007/s42770-021-00618-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malavolta, E. ; V. G. C. ; O. S. A. de. Evaluation of the Nutritional State of Plants: Principles and Applications. (1989).

- 39.Pradhan S, Pokhrel MR. Spectrophotometric determination of phosphate in sugarcane juice, fertilizer, detergent and water samples by molybdenum blue method. Sci. World. 2013;11:58–62. doi: 10.3126/sw.v11i11.9139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moll RH, Kamprath EJ, Jackson WA. Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of nitrogen utilization1. Agron. J. 1982;74:562–564. doi: 10.2134/agronj1982.00021962007400030037x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yahyazadeh M, Omidbaigi R, Zare R, Taheri H. Effect of some essential oils on mycelial growth of Penicillium digitatum Sacc. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;24:1445–1450. doi: 10.1007/s11274-007-9636-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

- 43.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng, Y., Leung, H. C. M., Yiu, S. M. & Chin, F. Y. L. IDBA—A Practical Iterative de Bruijn Graph De Novo Assembler. 426–440 (2010). 10.1007/978-3-642-12683-3_28.

- 45.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galardini M, Biondi EG, Bazzicalupo M, Mengoni A. CONTIGuator: A bacterial genomes finishing tool for structural insights on draft genomes. Source Code Biol. Med. 2011;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee I, Ouk Kim Y, Park S-C, Chun J. OrthoANI: An improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conesa A, et al. Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber T, et al. antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blin K, et al. antiSMASH 5.0: Updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W81–W87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimizu, G. D. , M. R. Y. P. , & Gonçalves, L. S. A. Package ‘AgroR.’ (2021).

- 53.Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008;25:25. doi: 10.18637/jss.v025.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from L.S.A.G on reasonable request.