Abstract

Well-regulated clinical trials have shown FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccines to be immunogenic and highly efficacious. We evaluated seroconversion rates in adults reporting ≥ 1 dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a cohort study of nearly 8000 adults residing in North Carolina to validate immunogenicity using a novel approach: at-home, participant administered point-of-care testing. Overall, 91.4% had documented seroconversion within 75 days of first vaccination (median: 31 days). Participants who were older and male participants were less likely to seroconvert (adults aged 41–65: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.69 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.64, 0.73], adults aged 66–95: aHR 0.55 [95% CI: 0.50, 0.60], compared to those 18–40; males: aHR 0.92 [95% CI: 0.87, 0.98], compared to females). Participants with evidence of prior infection were more likely to seroconvert than those without (aHR 1.50 [95% CI: 1.19, 1.88]) and those receiving BNT162b2 were less likely to seroconvert compared to those receiving mRNA-1273 (aHR 0.84 [95% CI: 0.79, 0.90]). Reporting at least one new symptom after first vaccination did not affect time to seroconversion, but participants reporting at least one new symptom after second vaccination were more likely to seroconvert (aHR 1.11 [95% CI: 1.05, 1.17]). This data demonstrates the high community-level immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines, albeit with notable differences in older adults, and feasibility of using at-home, participant administered point-of-care testing for community cohort monitoring.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04342884.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccines, SARS-CoV-2 serology, Cohort study, Community study

1. Introduction

As of March 29, 2022, over 6 million people worldwide have died due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. Two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are currently approved for use by the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA), mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2, both as a two-dose series [2], [3]. Studies showing decreased vaccine effectiveness over time and with variants prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to recommend that everyone receive a booster shot 5 months or more after their last COVID vaccine [4]. Approximately 66% of people in the U.S. are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and approximately 50% of those eligible have received a booster dose [5]. Based on evidence that protection may wane over time in certain populations, the FDA authorized a second booster dose of either mRNA vaccine for those 12 and older with immunocompromising conditions or anyone over 50 years of age [6]. As more time passes and additional variants arise, additional boosters or boosters targeting new variants may be needed.

In clinical trials of the mRNA vaccines, participants had rapid and robust immune responses. The participants in the Phase 1 trial of mRNA-1273 all seroconverted by 15 days after first vaccination [7]. Titers varied by age in the Phase 1 trial of the BNT162b2 vaccine: for participants receiving the FDA-approved dose, those aged 18–55 years mounted titers that surpassed that of convalescent plasma 21 days after the first dose, but participants aged 65–85 years took until seven days after the second dose to reach this level [8]. Antibody responses to BNT162b2 in healthcare workers in Israel 21 days after the first dose did not differ based on sex, but IgG titers decreased with increasing age and increased in those with a history of COVID-19 infection (regardless of whether the participant had detectable antibodies at the time of vaccination) [9]. Another study in Israeli healthcare workers showed that likelihood of seroconversion after one dose of BNT162b2 decreased with increasing age and was lower in males compared to females [10]. A study in healthcare workers in Belgium showed similar differences in antibody titers by age and previous infection status, and also showed higher titers in those receiving mRNA-1273 compared to those receiving BNT162b2 [11]. Additional information regarding timing of seroconversion and any potential differences in seroconversion between groups on a population level could inform the need for further monitoring of antibody responses in groups over time to help stratify groups that may require more frequent boosting. Currently, information about antibody responses after vaccination in real-world settings in the U.S. is limited.

To address gaps in knowledge about vaccine-induced seroconversion in a real-world setting in the U.S. and evaluate the use of home point-of-care testing for monitoring of antibody responses, we evaluated seroconversion rates in adults vaccinated with mRNA COVID–19 vaccines in a large longitudinal cohort study, the North Carolina COVID-19 Community Research Partnership (NC-CCRP). We also assessed the effect of sex, age, race/ethnicity, prior seropositivity, vaccine product, and symptoms following vaccination on rates of seroconversion in our cohort.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

Participants from this study were drawn from the NC-CCRP study. This cohort included participants recruited through patient portals, public websites, and community outreach from the following health systems: Wake Forest Baptist Health, Atrium Health, Wake Med, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Vidant Health, and Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine. Adults over 18 years of age were eligible for inclusion, and there were no exclusion criteria. Study procedures included daily online questionnaires for all participants, gathering electronic health records (EHR) for those who are patients in the participating health system, and periodic at-home serological testing for a subset of participants. The Wake Forest Baptist Health Institutional Review Board (IRB), which served as the central IRB for this study, approved the study protocol. The study conformed to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. Appropriate informed consent was obtained from study participants prior to any study procedures. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04342884. Enrollment began April 2020.

2.2. Participant data

Participants in the study completed daily online questionnaires about symptoms, exposures, and risk avoidance behaviors related to COVID-19. Participants also reported history of COVID-19 vaccination (date of receipt, product, dose one or dose two, participation in a clinical trial). Where EHR data and vaccination records were available, self-report of vaccination status and vaccination records were compared for agreement.

2.3. Laboratory assay characteristics

A subset of participants representing local demographics with oversampling for high-risk groups (healthcare workers, minorities) was invited to complete at-home test kits for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies every one to two months between April 16, 2020, and November 1, 2021. Participants performed an at-home lateral flow assay, the Scanwell SARS-CoV-2 IgM IgG Test from Teco Diagnostics, which tests for IgM and IgG to both SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike proteins. This assay was tested at the National Cancer Institute against Panels 2 and 3 and was found to have a resultant combined sensitivity (IgG and IgM) of 90% and specificity of 97.5% against Panel 2 and a combined sensitivity of 96.7% and specificity of 100% against Panel 3 (Supplementary Table 1 ) [12], [13]. Participant instructions for test completion are available in the Supplementary Materials. Test results were interpreted, recorded, and transmitted using a smartphone-based application through Scanwell Health.

2.4. Participant inclusion and exclusion

To examine vaccine-induced seroconversion in our study population, we analyzed data from participants who were ≥ 18 years old, self-reported receiving ≥ 1 dose of an mRNA vaccine, were seronegative on the last test before first dose and had ≥ 1 test result within 4–75 days after vaccination and prior to November 1, 2021. As of November 1, 2021, the NC-CCRP had 21,215 participants enrolled in the serological arm of the study. Of these, 16,996 (80.1%) participants reported receiving at least one mRNA vaccine.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Seroconversion was defined as a positive serological assay > 4 days after first dose, as it is likely that seroconversion at or before 4 days after first dose is related to infection and not to vaccination [14]. Follow-up time was from 5 days after first dose to day of documented seroconversion, last serological test, or 75 days after first dose, whichever came first. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate cumulative incidences. To obtain adjusted hazard ratios while controlling for possible violations of the proportional hazards assumption, a weighted Cox regression model adjusted for sex, age group, race/ethnicity, prior seropositivity, vaccine product, and reported symptoms after vaccination was used [15]. Prior seropositivity was comprised of participants who had previously tested positive on a serological test but seroreverted to negative on or before their last serological test prior to vaccination. For the analysis of reported symptoms after vaccination, participants were defined as having missing data if they did not complete at least one symptom survey in the seven days prior to vaccination and one in the seven days after vaccination. Wald-type 95% confidence intervals (CI) were constructed. R version 4.0.3 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

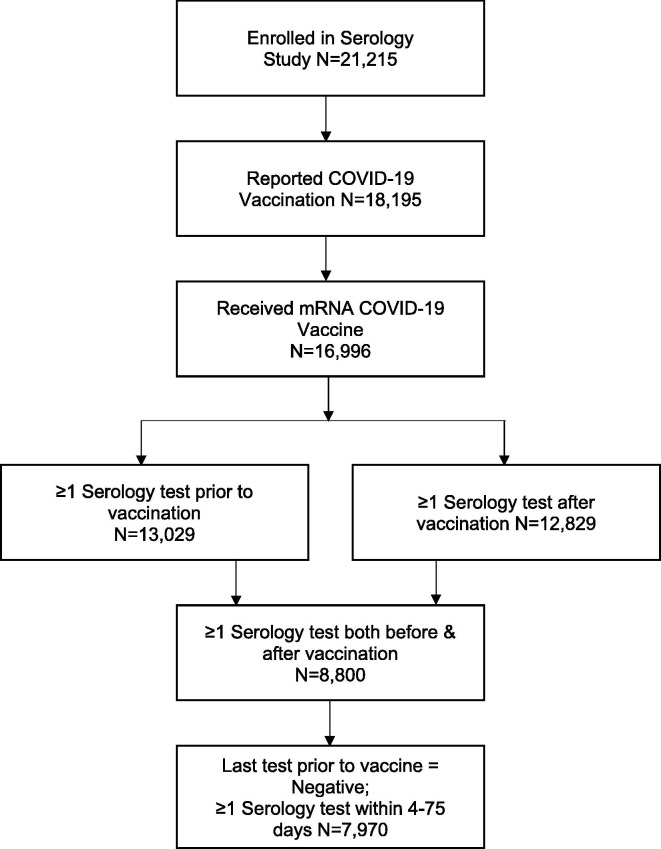

In the study population, 8,800 participants had at least one serology test before and one serology test within 75 days after the first vaccine dose, but 830 were excluded because they were seropositive on the last serological assay prior to vaccination or seroconverted less than four days after vaccination (Fig. 1 ). Therefore, a total of 7,970 participants were included in the analysis. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

Participant Inclusion Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics.

| Did not Seroconvert | Seroconverted | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 687 (8.6%) | 7283 (91.4%) | 7970 (100%) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 438 (7.8%) | 5194 (92.2%) | 5632 (70.7%) |

| Male | 249 (10.7%) | 2089 (89.3%) | 2338 (29.3%) |

| Age | |||

| 18–40 years | 132 (6.3%) | 1959 (93.7%) | 2091 (26.2%) |

| 41–65 years | 366 (8.4%) | 4009 (91.6%) | 4375 (54.9%) |

| 66–95 years | 189 (12.6%) | 1315 (87.4%) | 1504 (18.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (not Hispanic/Latino) | 657 (8.5%) | 7057 (91.5%) | 7714 (96.8%) |

| Other race/ethnicity1 | 30 (11.7%) | 226 (88.3%) | 256 (3.2%) |

| History of seropositivity2 | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.2%) | 134 (97.8%) | 137 (1.7%) |

| No | 684 (8.7%) | 7149 (91.3%) | 7833 (98.3%) |

| Vaccine received | |||

| BNT162b2 | 509 (8.6%) | 5428 (91.4%) | 5937 (74.5%) |

| mRNA-1273 | 178 (8.8%) | 1855 (91.2%) | 2033 (25.5%) |

Other race/ethnicity included Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, those who identified as Other, and those who did not or did not wish to specify their race.

History of previous positive serologic assay. The last serologic assay prior to vaccination was required to be negative for inclusion in this study.

3.2. Accuracy of vaccine Self-Report and time to seroconversion

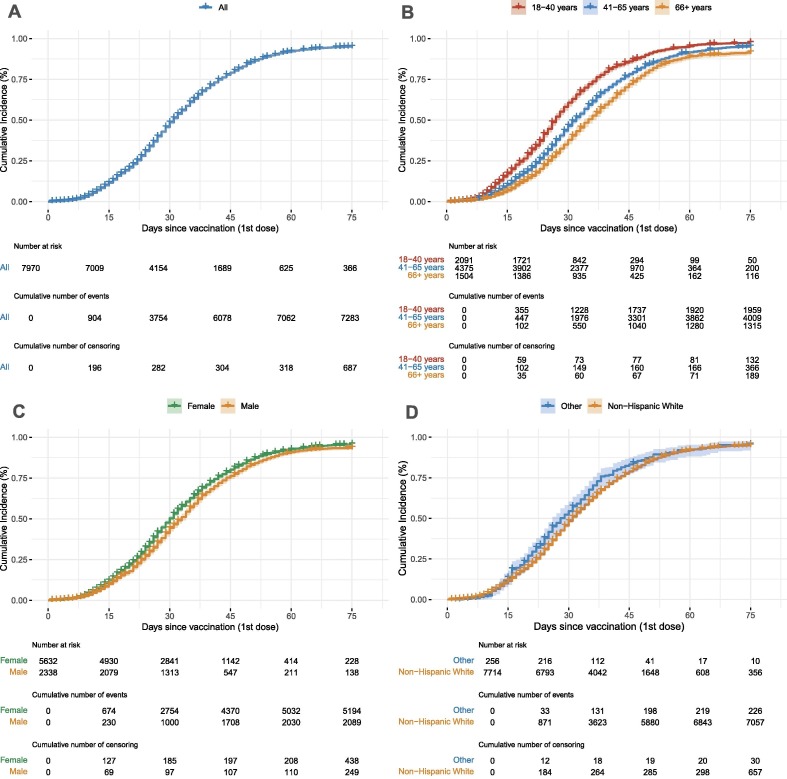

For 1,834 (23.0%) of the 7,970 participants included in the analysis, EHR data and self-report data regarding timing of vaccine dosing was available. The self-report matched the EHR data within ± 3 days for 1,655 (90.2%) of these 1,834 participants. Median time from vaccine to first test was 22 days and median time from vaccine to last test or date of censoring was 75 days. Participants had a median of two tests between vaccination and censoring. Overall, 7,283 (91.4%) of participants had documented seroconversion within 75 days of vaccination and median time to documented seroconversion after first vaccination was 31 days (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

A. Overall cumulative incidence of seroconversion in the cohort. Over 90% of participants seroconverted within 75 days of vaccination, with a median time of 31 days. B. Cumulative incidence of seroconversion based on age. Older participant age at the time of vaccination was associated with longer median time to seroconversion: 27 days for participants aged 18 to 40 years, 32 days for participants aged 41 to 65 years, and 35 days for participants 66 to 95 years. C. Cumulative incidence of seroconversion based on sex. Men had a longer median time to seroconversion (33 days) than women (30 days). D. Cumulative incidence of seroconversion based on race/ethnicity. Non-Hispanic White participants had a median time to documented seroconversion of 31 days compared to 28 days for other races/ethnicities. The number at risk, number of events, and number of censoring are listed below each figure and correspond to 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 days.

3.3. Seroconversion by Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity

We found that older participant age at the time of vaccination was associated with a longer median time to seroconversion: participants aged 18–40 years had a median time to seroconversion of 27 days compared to 32 days for participants aged 41–65 years, and 35 days for participants 66–95 years (Fig. 2 B). The median time to seroconversion was 30 days in women and 33 days in men (Fig. 2 C). The median time to seroconversion for White, non-Hispanic participants was 31 days compared to 28 days for all other races/ethnicities (Fig. 2 D). In the multivariate Cox model, we found that participants were less likely to seroconvert with increasing age: adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0.68 (95% CI: 0.64, 0.73) for participants 41–65 years of age and 0.55 (95% CI: 0.50, 0.60) for participants 66–95 years of age, compared to participants 18–40 years of age (Table 2 ). Males were less likely to seroconvert than females with an aHR of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.87, 0.98) (Table 2). Race/ethnicity was marginally significant in the multivariate model: White, non-Hispanic participants had an aHR of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.72, 0.99) compared to other races/ethnicities.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of Participant Characteristics and Likelihood of Seroconversion.

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) | 0.0082 |

| Age | ||

| 18–40 years | Ref | Ref |

| 41–65 years | 0.68 (0.64–0.73) | <0.0001 |

| 66–95 years | 0.55 (0.50–0.60) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Other race/ethnicity1 | Ref | Ref |

| White (not Hispanic/Latino) | 0.85 (0.72–0.99) | 0.0365 |

| History of seropositivity2 | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.70 (1.35–2.15) | <0.0001 |

| Vaccine received | ||

| Moderna mRNA-1273 | Ref | Ref |

| Pfizer BNT162b2 | 0.83 (0.77–0.88) | <0.0001 |

| Symptomatic after first dose | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 0.9594 |

| Symptomatic after second dose | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | 0.0004 |

Other race/ethnicity included Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, those who identified as Other, and those who did not or did not wish to specify their race.

History of previous positive serologic assay. The last serologic assay prior to vaccination was required to be negative for inclusion in this study.

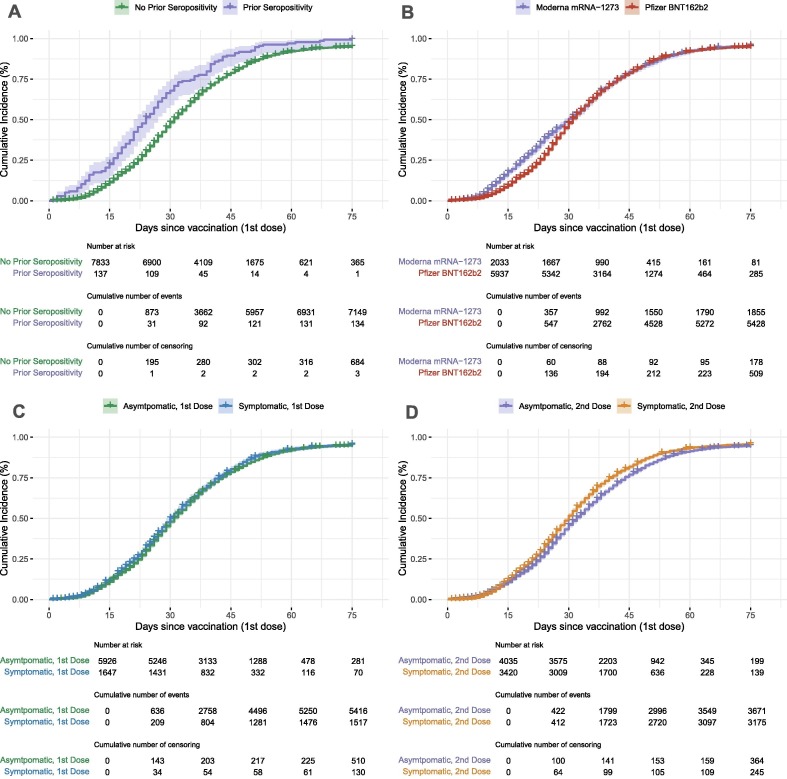

3.4. Seroconversion in previously seropositive participants

115 participants in our cohort had a prior positive serological test but had seroreverted to negative before vaccination as was required for inclusion in this study. Median time to seroconversion for this group was 25 days, compared to 31 days for those never seropositive prior to vaccination (Fig. 3 A). Previously seropositive participants were more likely to seroconvert, with a HR of 1.70 (95% CI: 1.35, 2.15) (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

A). Cumulative incidence of seroconversion based on prior seropositivity. Participants who were seropositive and then seroreverted prior to vaccination had a shorter median time to seroconversion (24 days) than those who were never seropositive prior to vaccination (31 days). B). Cumulative incidence of seroconversion based on vaccine received. Participants receiving Pfizer BNT162b2 took longer to seroconvert (31 days) than those receiving Moderna mRNA-1273 (30 days). C). Cumulative incidence of seroconversion associated with report of a new symptom after first dose. Participants who reported at least one new symptom after their first dose of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine had a median time to documented seroconversion of 30 days compared to 31 days for those who did not report any new symptom after their first COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. D). Cumulative incidence of seroconversion associated with report of a new symptom after second dose. Participants reporting at least one new symptom after their second dose of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine had a shorter median time to documented seroconversion (30 days) than those who did not report any new symptoms after their second dose (32 days). The number at risk, number of events, and number of censoring corresponds to 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 days.

3.5. Seroconversion by vaccine construct received

The majority of our study population, 5655 (74.9%) participants, received the BNT162b2 vaccine. The median time to seroconversion for participants receiving BNT162b2 was 31 days compared to 30 days for those receiving mRNA-1273 (Fig. 3 B). Participants receiving BNT162b2 were less likely to seroconvert than those receiving mRNA-1273 with an aHR of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.77, 0.88) (Table 2).

3.6. Symptoms related to vaccination and seroconversion

At least one syndromic survey was completed by 95.0% of participants in the seven days prior to and seven days following the date of first vaccination dose. Over 98% of participants (N = 7842) also reported the date of their second dose and of them, 7455 (95.1%) completed the at least one syndromic survey in the seven days prior to and seven days following the date of the second vaccination. After first vaccination, 1647 (20.7%) participants reported at least one new symptom of fever, chills, muscle pain, chest pain, fatigue, or headache (Table 3 ). Median time to seroconversion for those reporting symptoms after first vaccination was 30 days, compared to 31 days in those not, and this was not significantly associated with seroconversion in the multivariate model (aHR 1.00, 95% CI: 0.94, 1.07, Table 2). 3420 (42.9%) participants reported at least one new symptom after second vaccination (Table 3), with a median time to seroconversion of 30 days in those reporting a new symptom compared to 32 days in those not reporting a new symptom. In the multivariate model, participants reporting at least one new symptom after second vaccination were more likely to seroconvert than those who did not (aHR 1.11, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.17, Table 2). Number and percentage of participants reporting each symptom are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

New symptoms reported after each vaccination.

| Did not Seroconvert | Seroconverted | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| After First Vaccination | |||

| Any New Symptom | |||

| No | 510 (8.6%) | 5416 (91.4%) | 5926 (74.4%) |

| Yes | 130 (7.9%) | 1517 (92.1%) | 1647 (20.7%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Fever | |||

| No | 635 (8.5%) | 6849 (91.5%) | 7484 (93.9%) |

| Yes | 5 (5.6%) | 84 (94.4%) | 89 (1.1%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Chills | |||

| No | 625 (8.5%) | 6752 (91.5%) | 7377 (92.6%) |

| Yes | 15 (7.7%) | 181 (92.3%) | 196 (2.5%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Muscle pain | |||

| No | 569 (8.4%) | 6234 (91.6%) | 6803 (85.4%) |

| Yes | 71 (9.2%) | 699 (90.8%) | 770 (9.7%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Chest pain | |||

| No | 640 (8.5%) | 6929 (91.5%) | 7569 (95.0%) |

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Fatigue | |||

| No | 575 (8.4%) | 6269 (91.6%) | 6844 (85.9%) |

| Yes | 65 (8.9%) | 664 (91.1%) | 729 (9.1%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Headache | |||

| No | 597 (8.7%) | 6255 (91.2%) | 6852 (86.0%) |

| Yes | 43 (6.0%) | 678 (94.0%) | 721 (9.0%) |

| Missing | 47 (11.8%) | 350 (88.2%) | 397 (5.0%) |

| Did not Seroconvert | Seroconverted | Overall | |

| After Second Vaccination | |||

| Any New Symptom | |||

| No | 364 (9.0%) | 3671 (91.0%) | 4035 (50.6%) |

| Yes | 245 (7.2%) | 3175 (92.8%) | 3420 (42.9%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Fever | |||

| No | 569 (8.5%) | 6106 (91.5%) | 6675 (83.8%) |

| Yes | 40 (5.1%) | 740 (94.9%) | 780 (9.8%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Chills | |||

| No | 534 (8.6%) | 5695 (91.4%) | 6229 (78.2%) |

| Yes | 75 (6.1%) | 1151 (93.9%) | 1226 (15.4%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Muscle pain | |||

| No | 451 (8.9%) | 4627 (91.1%) | 5078 (63.7%) |

| Yes | 158 (6.6%) | 2219 (93.4%) | 2377 (29.8%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Chest pain | |||

| No | 606 (8.1%) | 6834 (91.9%) | 7440 (93.4%) |

| Yes | 3 (20.0%) | 12 (80.0%) | 15 (0.2%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Fatigue | |||

| No | 469 (8.7%) | 4918 (91.3%) | 5387 (67.6%) |

| Yes | 140 (6.8%) | 1928 (93.2%) | 2068 (25.9%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

| Headache | |||

| No | 499 (8.6%) | 5287 (91.4%) | 5786 (72.6%) |

| Yes | 110 (6.6%) | 1559 (93.4%) | 1669 (20.9%) |

| Missing | 78 (15.1%) | 437 (84.9%) | 515 (6.5%) |

4. Discussion

In our community cohort, we saw rapid seroconversion after vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines used in the U.S. While we saw high rates of seroconversion overall, we noted important differences between subgroups. Similar to results reported from vaccine trials and community cohorts in other countries [7], [8], [9], [11], we saw lower rates of seroconversion in those 41–65 years old and over 65 years old compared to those aged 18–40 years. Possible implications of age-related immunosenescence include prioritization for booster doses or even increased dosages in the elderly, which are options for the prevention of influenza and varicella zoster. Our study found an increased rate of seroconversion in females compared to males, which is consistent with a retrospective study of healthcare workers in Israel, a community cohort study that found higher IgG levels in females after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination and the general observation of sex differences in immunogenicity and efficacy of other vaccines [10], [16], [17]. Our findings that participants previously seropositive were more likely to seroconvert than previously seronegative participants and those receiving the BNT162b2 vaccine were less likely to seroconvert than those receiving mRNA-1273 mirror findings from other recent cohort studies done in other countries [9], [11]. Participants reporting at least one new symptom of fever, chills, muscle pain, chest pain, fatigue and/or headache in the seven days after second vaccination was also associated with a higher likelihood of seroconversion. This mirrors findings in a cohort study of healthcare workers in Japan, which found that higher fever, fatigue, headache, and chills were all independently associated with higher IgG titers after second BNT162b2 vaccine [18]. The consistency of our findings with previous literature also provides evidence that at-home point-of-care testing can provide important and meaningful information in a community cohort.

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, we relied on participant report for dates of first and second vaccinations. We found a high correlation between participant report and cross-checked EHR data, which suggests that our participant report data is reliable. The lateral flow assay used in this study had differing performances on two NCI panels, with the calculated positive predictive value ranging from 65.5 to 100% and a negative predictive value of 99.5–99.8% [12], [13]. While test performance characteristics could have inflated the overall rates of seroconversion, it is unlikely that they affected the subgroup analyses, as all subgroups utilized the same lateral flow assay. Serological testing kits were mailed to participants approximately monthly, but testing intervals varied between participants and had variable timing in relation to vaccination. At-home testing also may have missed some seroconversion events because ≥ 1 test between 4 and 75 days after vaccination was required for inclusion into this study, but in many cases, a single early negative test was the only available data point and was interpreted as a lack of seroconversion. Of note, variability of testing intervals based on the convenient, home-based testing design and inclusion criteria were consistent throughout the cohort, which should have allowed for unbiased subgroup comparisons. Generalizability of our study is likely limited to those with a higher socioeconomic status because the study procedures required informed consent, online participation, and connection with a healthcare system. Due to small numbers of various racial and ethnic groups, we were unable to analyze each racial and ethnic group separately. We acknowledge that by grouping racial/ethnic groups together, we are potentially missing more nuanced differences in responses.

A strength of our analysis is the collection of real-world immunogenicity data from a large longitudinal cohort using an at-home serology kit. To our knowledge, our cohort is larger than any previously described cohorts that have evaluated immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in community settings and is the first to provide associations between participant characteristics and seroconversion after vaccination using point-of-care testing. Concordance with previous studies validates our findings [9], [10], [11], [18]. Follow up studies estimating rates of seroreversion and long-term vaccine effectiveness in our community cohort are ongoing.

While vaccine hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines has decreased over time, vaccination rates in the U.S. remain much lower than desired, and only about half of those eligible have received a COVID-19 booster. Second booster doses for certain groups with known blunted responses to vaccines are now recommended by the US FDA, and, in anticipation of possible seasonal COVID-19 vaccination [19], clinical trials of SARS-CoV-2 variant vaccines are ongoing. Continued investigations and methods to identify those most in need of booster doses are needed. Our study shows that at-home point-of-care testing can provide robust, biologically plausible data. With further information regarding the correlation of vaccine effectiveness with seropositivity, point-of-care testing could potentially be used to monitor responses over time, providing real world data that could help inform decision making surrounding the need for booster vaccinations.

Funding.

This work was supported by the CARES Act of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [Contract # NC DHHS GTS #49927]. Additional support was received from the National Institutes of Health [K23AI155838 to DJF-K and K23AI125720 to AAB]. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HHS or the U.S. Government.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

DeAnna J. Friedman-Klabanoff: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ashley H. Tjaden: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Michele Santacatterina: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Iqra Munawar: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. John W. Sanders: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. David M. Herrington: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Thomas F. Wierzba: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Andrea A. Berry: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The COVID-19 Community Research Partnership gratefully acknowledges the commitment and dedication of the study participants. Programmatic, laboratory, and technical support was provided by Vysnova Partners, Inc., Oracle, Scanwell Health, and Neoteryx. The Partnership is listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04342884). A complete list of Study Sites, investigators, and staff can be found in the Appendix.

Data Availability

Results of the COVID-19 CRP are being disseminated on the study website (https://www.covid19communitystudy.org/) as well as in publications and presentations in medical journals and at scientific meetings. At end of the study, the databases will be made publicly available in a de-identified manner according to CDC and applicable U.S. Federal policies.

COVID-19 Community Research Partnership Group (*Site Principal Investigator):

Wake Forest School of Medicine: Thomas F Wierzba PhD, MPH, MS*, John Walton Sanders, MD, MPH, David Herrington, MD, MHS, Mark A. Espeland, PhD, MA, John Williamson, PharmD, Morgana Mongraw-Chaffin, PhD, MPH, Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH, Martha A. Alexander-Miller, PhD, Paola Castri, MD, PhD, Allison Mathews, PhD, MA, Iqra Munawar, MS, Austin Lyles Seals, MS, Brian Ostasiewski, Christine Ann Pittman Ballard, MPH, Metin Gurcan, PhD, MS, Alexander Ivanov, MD, Giselle Melendez Zapata, MD, Marlena Westcott, PhD, Karen Blinson, Laura Blinson, Mark Mistysyn, Donna Davis, Lynda Doomy, Perrin Henderson, MS, Alicia Jessup, Kimberly Lane, Beverly Levine, PhD, Jessica McCanless, MS, Sharon McDaniel, Kathryn Melius, MS, Christine O’Neill, Angelina Pack, RN, Ritu Rathee, RN, Scott Rushing, Jennifer Sheets, Sandra Soots, RN, Michele Wall, Samantha Wheeler, John White, Lisa Wilkerson, Rebekah Wilson, Kenneth Wilson, Deb Burcombe, Georgia Saylor, Megan Lunn, Karina Ordonez, Ashley O’Steen, MS, Leigh Wagner.

Atrium Health: Michael S. Runyon MD, MPH*, Lewis H. McCurdy MD*, Michael A. Gibbs, MD, Yhenneko J. Taylor, PhD, Lydia Calamari, MD, Hazel Tapp, PhD, Amina Ahmed, MD, Michael Brennan, DDS, Lindsay Munn, PhD RN, Keerti L. Dantuluri, MD, Timothy Hetherington, MS, Lauren C. Lu, Connell Dunn, Melanie Hogg, MS, CCRA, Andrea Price, Marina Leonidas, Melinda Manning, Whitney Rossman, MS, Frank X. Gohs, MS, Anna Harris, MPH, Jennifer S. Priem, PhD, MA, Pilar Tochiki, Nicole Wellinsky, Crystal Silva, Tom Ludden PhD, Jackeline Hernandez, MD, Kennisha Spencer, Laura McAlister.

MedStar Health Research Institute: William Weintraub MD*, Kristen Miller, DrPH, CPPS*, Chris Washington, Allison Moses, Sarahfaye Dolman, Julissa Zelaya-Portillo, John Erkus, Joseph Blumenthal, Ronald E. Romero Barrientos, Sonita Bennett, Shrenik Shah, Shrey Mathur, Christian Boxley, Paul Kolm, PhD, Ella Franklin, Naheed Ahmed, Moira Larsen.

Tulane: Richard Oberhelman MD*, Joseph Keating PhD*, Patricia Kissinger, PhD, John Schieffelin, MD, Joshua Yukich, PhD, Andrew Beron, MPH, Johanna Teigen, MPH.

University of Maryland School of Medicine: Karen Kotloff MD*, Wilbur H. Chen MD, MS*, DeAnna Friedman-Klabanoff, MD, Andrea A. Berry, MD, Helen Powell, PhD, Lynnee Roane, MS, RN, Reva Datar, MPH, Colleen Reilly.

University of Mississippi: Adolfo Correa MD, PhD*, Bhagyashri Navalkele, MD, Yuan-I Min, PhD, Alexandra Castillo, MPH, Lori Ward, PhD, MS, Robert P. Santos, MD, MSCS, Pramod Anugu, Yan Gao, MPH, Jason Green, Ramona Sandlin, RHIA, Donald Moore, MS, Lemichal Drake, Dorothy Horton, RN, Kendra L. Johnson, MPH, Michael Stover.

Wake Med Health and Hospitals: William H. Lagarde MD*, LaMonica Daniel, BSCR.

New Hanover: Patrick D. Maguire MD*, Charin L. Hanlon, MD, Lynette McFayden, MSN, CCRP, Isaura Rigo, MD, Kelli Hines, BS, Lindsay Smith, BA, Monique Harris, CCRP, Belinda Lissor, AAS, CCRP, Vivian Cook, MA, MPH, Maddy Eversole, BS, Terry Herrin, BS, Dennis Murphy, RN, Lauren Kinney, BS, Polly Diehl, MS, RHIA, Nicholas Abromitis, BS, Tina St. Pierre, BS, Bill Heckman, Denise Evans, Julian March, BA, Ben Whitlock, CPA, MSA, Wendy Moore, BS, AAS, Sarah Arthur, MSW, LCSW, Joseph Conway.

Vidant Health: Thomas R. Gallaher MD*, Mathew Johanson, MHA, CHFP, Sawyer Brown, MHA, Tina Dixon, MPA, Martha Reavis, Shakira Henderson, PhD, DNP, MS, MPH, Michael Zimmer, PhD, Danielle Oliver, Kasheta Jackson, DNP, RN, Monica Menon, MHA, Brandon Bishop, MHA, Rachel Roeth, MHA.

Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine: Robin King-Thiele DO*, Terri S. Hamrick PhD*, Abdalla Ihmeidan, MHA, Amy Hinkelman, PhD, Chika Okafor, MD (Cape Fear Valley Medical Center), Regina B. Bray Brown, MD, Amber Brewster, MD, Danius Bouyi, DO, Katrina Lamont, MD, Kazumi Yoshinaga, DO, (Harnett Health System), Poornima Vinod, MD, A. Suman Peela, MD, Giera Denbel, MD, Jason Lo, MD, Mariam Mayet-Khan, DO, Akash Mittal, DO, Reena Motwani, MD, Mohamed Raafat, MD (Southeastern Health System), Evan Schultz, DO, Aderson Joseph, MD, Aalok Parkeh, DO, Dhara Patel, MD, Babar Afridi, DO (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley).

George Washington University Data Coordinating Center: Diane Uschner PhD*, Sharon L. Edelstein, ScM, Michele Santacatterina, PhD, Greg Strylewicz, PhD, Brian Burke, MS, Mihili Gunaratne, MPH, Meghan Turney, MA, Shirley Qin Zhou, MS, Ashley H Tjaden, MPH, Lida Fette, MS, Asare Buahin, Matthew Bott, Sophia Graziani, Ashvi Soni, MS, Guoqing Diao, PhD, Jone Renteria, MS.

George Washington University Mores Lab: Christopher Mores, PhD, Abigail Porzucek, MS.

Oracle Corporation: Rebecca Laborde, Pranav Acharya.

Sneez LLC: Lucy Guill, MBA, Danielle Lamphier, MBA, Anna Schaefer, MSM, William M. Satterwhite, JD, MD.

Vysnova Partners: Anne McKeague, PhD, Johnathan Ward, MS, Diana P. Naranjo, MA, Nana Darko, MPH, Kimberly Castellon, BS, Ryan Brink, MSCM, Haris Shehzad, MS, Derek Kuprianov, Douglas McGlasson, MBA, Devin Hayes, BS, Sierra Edwards, MS, Stephane Daphnis, MBA, Britnee Todd, BS.

Javara Inc: Atira Goodwin.

External Advisory Council: Ruth Berkelman, MD, Emory, Kimberly Hanson, MD, U of Utah, Scott Zeger, PhD, Johns Hopkins, Cavan Reilly, PhD, U. of Minnesota, Kathy Edwards, MD, Vanderbilt, Helene Gayle, MD MPH, Chicago Community Trust, Stephen Redd.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.021.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine; [accessed 31 August 2021].

- 3.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Takes Key Action by Approving Second COVID-19 Vaccine, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-takes-key-action-approving-second-covid-19-vaccine; [accessed 29 March 2022].

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Approved or Authorized in the United States, https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html#recommendations; [accessed 29 March 2022].

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total; [accessed 29 March 2022].

- 6.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Second Booster Dose of Two COVID-19 Vaccines for Older and Immunocompromised Individuals, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-second-booster-dose-two-covid-19-vaccines-older-and; [accessed 30 March 2022].

- 7.Jackson L.A., Anderson E.J., Rouphael N.G., Roberts P.C., Makhene M., Coler R.N., et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1920–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh E.E., Frenck R.W., Falsey A.R., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based Covid-19 Vaccine Candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu Jabal K, Ben-Amram H, Beiruti K, Batheesh Y, Sussan C, Zarka S, et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Euro Surveill 2021; 26 https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.6.2100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shachor-Meyouhas Y., Hussein K., Szwarcwort-Cohen M., Weissman A., Mekel M., Dabaja-Younis H., et al. Single BNT162b2 vaccine dose produces seroconversion in under 60 s cohort. Vaccine. 2021;39:6902–6906. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steensels D., Pierlet N., Penders J., Mesotten D., Heylen L. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Response Following Vaccination With BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Serology Test Evaluation Report for “Scanwell SARS-CoV-2 IgM IgG Rapid Test” from Teco Diagnostics, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/presentations/maf/maf3441-a001.pdf; [accessed 09 September 2021].

- 13.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Serology Test Evaluation Report for “Scanwell SARS-CoV-2 IgM IgG Test” from Teco Diagnostics, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/presentations/maf/maf3434-a001.pdf; [accessed 09 September 2021].

- 14.Krammer F., Srivastava K., Alshammary H., Amoako A.A., Awawda M.H., Beach K.F., et al. Antibody responses in seropositive persons after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1372–1374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schemper M., Wakounig S., Heinze G. The estimation of average hazard ratios by weighted Cox regression. Stat Med. 2009;28:2473–2489. doi: 10.1002/sim.3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein S.L., Marriott I., Fish E.N. Sex-based differences in immune function and responses to vaccination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:9–15. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demonbreun A.R., Sancilio A., Velez M.E., Ryan D.T., Pesce L., Saber R., et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccination generates greater IgG levels in women compared to men. J Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tani N., Chong Y., Kurata Y., Gondo K., Oishi R., Goto T., et al. Relation of fever intensity and antipyretic use with specific antibody response after two doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2022;40(13):2062–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks P., Woodcock J., Califf R. COVID-19 Vaccination-Becoming Part of the New Normal. JAMA. 2022;327(19):1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Results of the COVID-19 CRP are being disseminated on the study website (https://www.covid19communitystudy.org/) as well as in publications and presentations in medical journals and at scientific meetings. At end of the study, the databases will be made publicly available in a de-identified manner according to CDC and applicable U.S. Federal policies.

COVID-19 Community Research Partnership Group (*Site Principal Investigator):

Wake Forest School of Medicine: Thomas F Wierzba PhD, MPH, MS*, John Walton Sanders, MD, MPH, David Herrington, MD, MHS, Mark A. Espeland, PhD, MA, John Williamson, PharmD, Morgana Mongraw-Chaffin, PhD, MPH, Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH, Martha A. Alexander-Miller, PhD, Paola Castri, MD, PhD, Allison Mathews, PhD, MA, Iqra Munawar, MS, Austin Lyles Seals, MS, Brian Ostasiewski, Christine Ann Pittman Ballard, MPH, Metin Gurcan, PhD, MS, Alexander Ivanov, MD, Giselle Melendez Zapata, MD, Marlena Westcott, PhD, Karen Blinson, Laura Blinson, Mark Mistysyn, Donna Davis, Lynda Doomy, Perrin Henderson, MS, Alicia Jessup, Kimberly Lane, Beverly Levine, PhD, Jessica McCanless, MS, Sharon McDaniel, Kathryn Melius, MS, Christine O’Neill, Angelina Pack, RN, Ritu Rathee, RN, Scott Rushing, Jennifer Sheets, Sandra Soots, RN, Michele Wall, Samantha Wheeler, John White, Lisa Wilkerson, Rebekah Wilson, Kenneth Wilson, Deb Burcombe, Georgia Saylor, Megan Lunn, Karina Ordonez, Ashley O’Steen, MS, Leigh Wagner.

Atrium Health: Michael S. Runyon MD, MPH*, Lewis H. McCurdy MD*, Michael A. Gibbs, MD, Yhenneko J. Taylor, PhD, Lydia Calamari, MD, Hazel Tapp, PhD, Amina Ahmed, MD, Michael Brennan, DDS, Lindsay Munn, PhD RN, Keerti L. Dantuluri, MD, Timothy Hetherington, MS, Lauren C. Lu, Connell Dunn, Melanie Hogg, MS, CCRA, Andrea Price, Marina Leonidas, Melinda Manning, Whitney Rossman, MS, Frank X. Gohs, MS, Anna Harris, MPH, Jennifer S. Priem, PhD, MA, Pilar Tochiki, Nicole Wellinsky, Crystal Silva, Tom Ludden PhD, Jackeline Hernandez, MD, Kennisha Spencer, Laura McAlister.

MedStar Health Research Institute: William Weintraub MD*, Kristen Miller, DrPH, CPPS*, Chris Washington, Allison Moses, Sarahfaye Dolman, Julissa Zelaya-Portillo, John Erkus, Joseph Blumenthal, Ronald E. Romero Barrientos, Sonita Bennett, Shrenik Shah, Shrey Mathur, Christian Boxley, Paul Kolm, PhD, Ella Franklin, Naheed Ahmed, Moira Larsen.

Tulane: Richard Oberhelman MD*, Joseph Keating PhD*, Patricia Kissinger, PhD, John Schieffelin, MD, Joshua Yukich, PhD, Andrew Beron, MPH, Johanna Teigen, MPH.

University of Maryland School of Medicine: Karen Kotloff MD*, Wilbur H. Chen MD, MS*, DeAnna Friedman-Klabanoff, MD, Andrea A. Berry, MD, Helen Powell, PhD, Lynnee Roane, MS, RN, Reva Datar, MPH, Colleen Reilly.

University of Mississippi: Adolfo Correa MD, PhD*, Bhagyashri Navalkele, MD, Yuan-I Min, PhD, Alexandra Castillo, MPH, Lori Ward, PhD, MS, Robert P. Santos, MD, MSCS, Pramod Anugu, Yan Gao, MPH, Jason Green, Ramona Sandlin, RHIA, Donald Moore, MS, Lemichal Drake, Dorothy Horton, RN, Kendra L. Johnson, MPH, Michael Stover.

Wake Med Health and Hospitals: William H. Lagarde MD*, LaMonica Daniel, BSCR.

New Hanover: Patrick D. Maguire MD*, Charin L. Hanlon, MD, Lynette McFayden, MSN, CCRP, Isaura Rigo, MD, Kelli Hines, BS, Lindsay Smith, BA, Monique Harris, CCRP, Belinda Lissor, AAS, CCRP, Vivian Cook, MA, MPH, Maddy Eversole, BS, Terry Herrin, BS, Dennis Murphy, RN, Lauren Kinney, BS, Polly Diehl, MS, RHIA, Nicholas Abromitis, BS, Tina St. Pierre, BS, Bill Heckman, Denise Evans, Julian March, BA, Ben Whitlock, CPA, MSA, Wendy Moore, BS, AAS, Sarah Arthur, MSW, LCSW, Joseph Conway.

Vidant Health: Thomas R. Gallaher MD*, Mathew Johanson, MHA, CHFP, Sawyer Brown, MHA, Tina Dixon, MPA, Martha Reavis, Shakira Henderson, PhD, DNP, MS, MPH, Michael Zimmer, PhD, Danielle Oliver, Kasheta Jackson, DNP, RN, Monica Menon, MHA, Brandon Bishop, MHA, Rachel Roeth, MHA.

Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine: Robin King-Thiele DO*, Terri S. Hamrick PhD*, Abdalla Ihmeidan, MHA, Amy Hinkelman, PhD, Chika Okafor, MD (Cape Fear Valley Medical Center), Regina B. Bray Brown, MD, Amber Brewster, MD, Danius Bouyi, DO, Katrina Lamont, MD, Kazumi Yoshinaga, DO, (Harnett Health System), Poornima Vinod, MD, A. Suman Peela, MD, Giera Denbel, MD, Jason Lo, MD, Mariam Mayet-Khan, DO, Akash Mittal, DO, Reena Motwani, MD, Mohamed Raafat, MD (Southeastern Health System), Evan Schultz, DO, Aderson Joseph, MD, Aalok Parkeh, DO, Dhara Patel, MD, Babar Afridi, DO (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley).

George Washington University Data Coordinating Center: Diane Uschner PhD*, Sharon L. Edelstein, ScM, Michele Santacatterina, PhD, Greg Strylewicz, PhD, Brian Burke, MS, Mihili Gunaratne, MPH, Meghan Turney, MA, Shirley Qin Zhou, MS, Ashley H Tjaden, MPH, Lida Fette, MS, Asare Buahin, Matthew Bott, Sophia Graziani, Ashvi Soni, MS, Guoqing Diao, PhD, Jone Renteria, MS.

George Washington University Mores Lab: Christopher Mores, PhD, Abigail Porzucek, MS.

Oracle Corporation: Rebecca Laborde, Pranav Acharya.

Sneez LLC: Lucy Guill, MBA, Danielle Lamphier, MBA, Anna Schaefer, MSM, William M. Satterwhite, JD, MD.

Vysnova Partners: Anne McKeague, PhD, Johnathan Ward, MS, Diana P. Naranjo, MA, Nana Darko, MPH, Kimberly Castellon, BS, Ryan Brink, MSCM, Haris Shehzad, MS, Derek Kuprianov, Douglas McGlasson, MBA, Devin Hayes, BS, Sierra Edwards, MS, Stephane Daphnis, MBA, Britnee Todd, BS.

Javara Inc: Atira Goodwin.

External Advisory Council: Ruth Berkelman, MD, Emory, Kimberly Hanson, MD, U of Utah, Scott Zeger, PhD, Johns Hopkins, Cavan Reilly, PhD, U. of Minnesota, Kathy Edwards, MD, Vanderbilt, Helene Gayle, MD MPH, Chicago Community Trust, Stephen Redd.