Abstract

Background:

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are medications contra-indicated in particular circumstances. We sought to characterize PIMs by level of polypharmacy by age, sex and race/ethnicity.

Methods:

We performed a cross-sectional drug dispensing study using electronic health records available through the US Department of Veterans Affairs. We extracted pharmacy fill and refill records during fiscal year 2016 (i.e., October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016) for all patients aged 49 to 70 who accessed care in the preceding fiscal year. PIMs were defined by the combined Beers and Laroche (henceforth Beers Laroche) criteria used for older patients and the PROMPT criteria used for middle-aged.

Results:

In the 1 499 586 patients aged 49–64, PIMs prevalence by PROMPT in patients with 0–4, 5–9 and ≥10 medications was 14.0%, 62.2% and 86.1%, respectively, and by Beers Laroche was 14.3%, 63.4% and 85.7%, respectively. In the 1 249 119 patients aged 65–70, PIMs prevalence by Beers Laroche was 14.8%, 59.9% and 83.3%, and by PROMPT was 13.9%, 57.4% and 82.0%, respectively. Meaningful differences in prevalence were shown by sex and race/ethnicity according to both set of criteria (e.g. PROMPT in patients with 5–9 medications: 66.1% women vs. 59.3% men; Standardized-mean-differences (SMD) = 0.14; 61.7% of White vs. 54.5% of non-White; SMD= 0.15). The most common PIMs were digestive, analgesic, antidiabetic and psychotropic medications.

Conclusion:

Prevalence of PIMs was high and increased with polypharmacy. Beers Laroche and PROMPT provided similar estimations inside and outside their target age, suggesting that PIMS are common among those with polypharmacy regardless of age.

Keywords: Pharmacoepidemiology, Age, Data analysis, Older, Middle-aged, Population health, Polypharmacy, Potentially inappropriate medications, Drug utilization study

Introduction

Polypharmacy, typically defined as the use of five or more concurrent medications, is common and associated with adverse drug events [1], drug-drug interactions [2], non-adherence [3], cognitive impairment [4], falls [5], hospitalisations [6] and mortality [7]. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are defined as drugs for which risks outweigh potential benefits [8]. PIMS include specific drugs that should not be used in general, or in patients with multimorbidity, or at a certain age.

Large national healthcare databases offer real-world data, and can help understand the specific mechanisms for harm from polypharmacy [9]. For instance, healthcare databases provide the opportunity to look at trends in prescription drug use. In the United States (US), polypharmacy increased from 8.2% to 15.0% between 1999 and 2012 among adults, aged 20 years and over [10].

Lists of PIMS have been created by experts and may help explain harms associated with polypharmacy [11,12]. Most of these lists focus on patients aged 65 or over because advanced age is associated with altered pharmacokinetics; pharmacodynamics and multiple diseases, which can help trigger these adverse events [13]. The Beers criteria were created in the US in 1991 and regularly updated with the latest version in 2019. The Laroche list was published in 2007 and is an adaptation to the French setting but also provides additional data. PROMPT criteria were developed in 2014 to target specifically middle aged patients (45 to 64 years old) [14]. These criteria overlap and commonalities and differences can help paint a more comprehensive picture of PIMs [14–16].

PIMs lists have been applied in health care databases mainly in Europe and among those over 65 years with few consideration of sex or race [17]. Very little work has been done among those under 65 years of age or according to sex and race/ethnicity. The aim of this study was to measure the prevalence of PIMs by level of polypharmacy using three commonly used PIMs criteria among patients aged 49 to 70 years old in the largest integrated healthcare system in the US, overall and by demographic subgroups.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional drug utilization study using data from electronic health records available through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The VA provides healthcare benefits to more than 9 million patients annually at over 1200 points-of-care. The CDW includes all pharmacy fills and refills, inpatient and outpatient diagnosis, and demographics. The Veteran Birth Cohort is a subset of CDW and includes patients born between 1945 and 1965, which accounts for approximately 4.5 million patients [18,19]. We extracted data from fiscal year 2016 (i.e., October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016) on all patients in the Veteran Birth Cohort who were alive on October 1, 2015 and accessed care in the preceding fiscal year. The Veteran Birth Cohort has been approved by the institutional review boards of Yale University (ref #1506016006) and VA Connecticut Healthcare System (ref #AJ0013), granted a waiver of informed consent, and deemed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant.

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) and polypharmacy

All drugs were considered regardless of route of administration (systemic or not). Specific therapeutic classes were excluded: antiseptics, soap, deodorants, keratolytics, diagnosis agents, vaccines, immunoglobulins, contact lens, eye washes, dental agents, and devices. Fixed dose combinations were split into active ingredients for systemic and oral drugs. Topical combinations (including dermatological, nasal, optical and otic agents) were not split and counted as one medication.

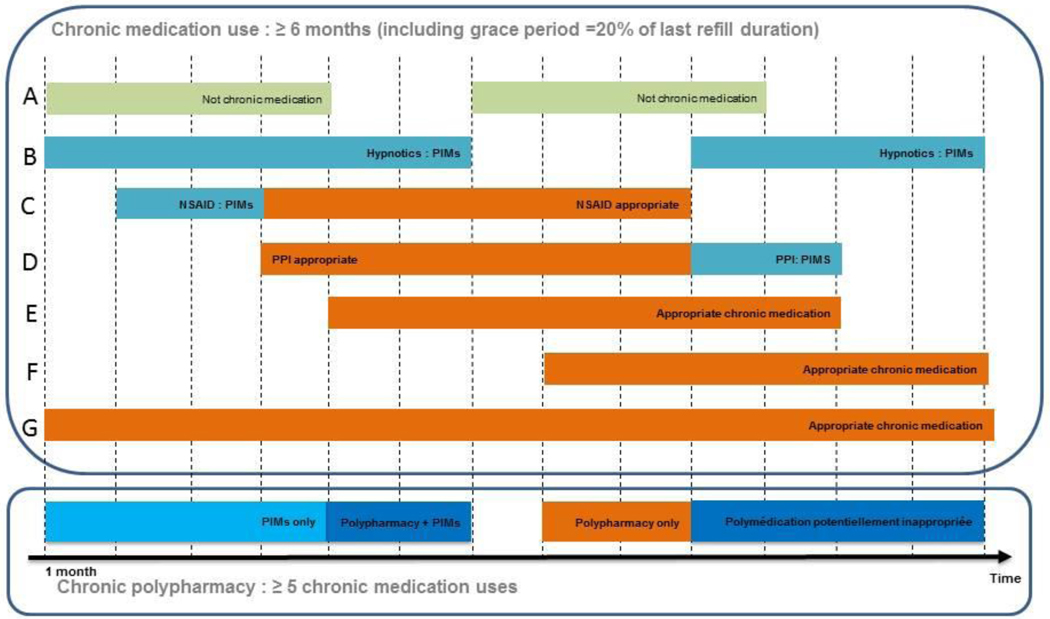

Chronic medication use was defined as uninterrupted duration of dispensed medication for at least 183 days (6 months), allowing for a grace period of 20% the prescription duration after each fill to account for potential stockpiling. Polypharmacy was defined by the use of five to nine chronic medications on any single day during the study period; hyperpolypharmacy by the use of ten chronic medications or more (Figure 1). We extracted medication data from up to one year prior to the study period, fiscal year 2015, to identify chronic medications that had already started before and continued after the start of the study.

Figure 1:

Definition of exposure to chronic polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) in 2016. The exemple presented defined an individuals who is prevalent of PIMs and polypharmacy in 2016

PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; NSAID: Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug

Beers and Laroche criteria were combined (henceforth referred to simply as Beers Laroche) and applied simultaneously and PROMPT criteria were applied separately (Table S1 and S2). We used only the criteria that were applicable in the VA according to clinical (e.g., benign prostatic hyperplasia or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were not identifiable) and pharmacy data (e.g., aspirin indication could not be identified as antiplatelet or an analgesic). For Beers/Laroche criteria, if a medication was mentioned in both lists with different requirement, when applied to the data, the list applied was the one with the broader criteria (e.g., Benzodiazepines and hypnotics are inappropriate at any dose according to Beers while half dose can be used according to Laroche. The Beers criteria were applied in this case).

PIMs were considered as any drug identified as potentially inappropriate by at least one applicable criterion of either Beers Laroche or PROMPT lists, regardless of age [12,14,20].

Other characteristics

We extracted data on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and race/ethnicity). We also used inpatient and outpatient ICD-9 diagnostic codes occurring in the year prior to study start to identify a large set of clinical characteristics, including hyperlipidemia, hypertension, mild depression, diabetes, pulmonary disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol abuse, myocardial infarction, anxiety, major depression, bipolar disorder, chronic seizure, delirium, dementia, helicobacter pylori, heart failure, gastric or duodenal ulcers, falls, fractures, oesophagitidis, pathological hypersecretory condition, Parkinson disease, and schizophrenia (Table S3)

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of polypharmacy/hyperpolypharmacy was defined as the number of patients who had at least one day of polypharmacy/hyperpolypharmacy in fiscal year 2016 out of the number of all eligible patients included in the study (n=2,748,705). Prevalence of PIMs was defined as the number of individuals with at least one day of any chronic PIMs (Figure 1) over patients with 0–4 medications, polypharmacy (5–9 medications) or hyperpolypharmacy (10 or more). All analyses were stratified on age (49 – 64 years old and 65 – 70 years old), sex and race/ethnicity. White and Black patients, were defined as such if they had no Hispanic ethnicity. Hispanic are defined by ethnicity regardless of other races. Race “other” were patients who were not in any of the above categories. Standardised mean differences (SMDs) were used to estimate differences of PIMs prevalence between age, sex and races groups with a SMD < 0.1 indicating no difference, 0.2 a small difference, 0.5 a moderate difference and 0.8 a large difference [21]. All data management and analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Of 3 923 534 patients in the Veteran Birth Cohort alive on October 1, 2015 who had ever accessed VA care, 808 796 were excluded because they did not access VA care in the preceding fiscal year, and 366 033 were excluded because they initiated VA care in the preceding fiscal year and therefore were unlikely to have established chronic care in the VA before study start. Therefore, 2 748 705 patients with active use and an established clinical history were included in this study. They were mostly men (93.3%) and the mean age was 62 years old, with 45.4% of patients aged 65 −70. They were mostly White (68.7%) or Black (20.3%). The most frequent chronic conditions were hyperlipidemia (66.0%), hypertension (64.8%), depression (34.3%) and diabetes (30.1%). In fiscal year 2016, the prevalence of polypharmacy (5–9 medications) was 23.0% and hyperpolypharmacy (≥ 10 medications) was 7.3%. The prevalence of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy in patients aged 65–70 were 27.0% and 9.1%respectively , and in patients aged 49–64 19.7% and 5.8% respectively. Among men, the prevalence of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy were 23.3% and 7.4%, and among women 18.9% and 5.9%. Prevalence of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy by race were 24.0% and 7.9% in White, 21.6% and 6.1% in Black, 22.3% and 6.7% in Hispanic, and 16.0% and 4.7% in other race (Table 1, Table S4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients aged 49–70 years in 2016 according to age and sex

| Birth cohort | 49 – 64 years old | 65 – 70 years old | Men | Women | ||||||

| 2 748 705 | 1 499 586 | 1 249 119 | 2 563 239 | 185 466 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age – mean(sd) | 62.1 | (5.8) | 57.7 | (4.3) | 67.3 | (1.5) | 62.4 | (5.8) | 57.9 | (5.3) |

| Sex – n(%) | ||||||||||

| Men | 2 563 239 | (93.3) | 1 339 478 | (89.3) | 1 223 761 | (98.0) | - | - | ||

| Women | 185 466 | (6.8) | 160 108 | (10.7) | 25 358 | (2.0) | - | - | ||

| Chronic medication count | ||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 1 914 269 | (69.6) | 1 116 351 | (74.4) | 797 918 | (63.9) | 1 774 904 | (69.2) | 139 365 | (75.1) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 633 061 | (23.0) | 296 032 | (19.7) | 337 029 | (27.0) | 597 938 | (23.3) | 35 123 | (18.9) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 201 375 | (7.3) | 87 203 | (5.8) | 114 172 | (9.1) | 190 397 | (7.4) | 10 978 | (5.9) |

| Race/Etdnicity – n(%) | ||||||||||

| White | 1 888 697 | (68.7) | 899 278 | (60.0) | 989 419 | (79.2) | 1 780 727 | (69.5) | 107 970 | (58.2) |

| Black | 558 521 | (20.3) | 399 971 | (26.7) | 158 550 | (12.7) | 501 921 | (19.6) | 56 600 | (30.5) |

| Hispanic | 164 378 | (6.0) | 96 802 | (6.5) | 67 576 | (5.4) | 156 192 | (6.1) | 8 186 | (4.4) |

| Other | 137 109 | (5.0) | 103 535 | (6.9) | 33 574 | (2.7) | 124 399 | (4.9) | 12 710 | (6.9) |

| Chronic diseases1 – n(%) | ||||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 813 447 | (66.0) | 889 619 | (59.3) | 923 828 | (74.0) | 1 709 605 | (66.7) | 103 842 | (56.0) |

| Hypertension | 1 780 446 | (64.8) | 872 946 | (58.2) | 907 500 | (72.7) | 1 686 583 | (65.8) | 93 863 | (50.6) |

| Mild depression | 942 054 | (34.3) | 551 503 | (36.8) | 390 551 | (31.3) | 852 953 | (33.3) | 89 101 | (48.0) |

| Diabetes | 826 715 | (30.1) | 390 551 | (26.0) | 447 226 | (35.8) | 788 915 | (30.8) | 37 800 | (20.4) |

| Pulmonary disorder | 611 315 | (22.2) | 313 425 | (20.9) | 297 890 | (23.8) | 562 852 | (22.0) | 48 463 | (26.1) |

| PTSD | 560 230 | (20.4) | 239 752 | (16.0) | 320 478 | (25.7) | 517 983 | (20.2) | 42 247 | (22.8) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 552 995 | (20.1) | 346 246 | (23.1) | 206 749 | (16.6) | 532 290 | (20.8) | 20 705 | (11.2) |

| Myocardial Infarction/Coronary artery diseases | 517 395 | (18.8) | 200 191 | (13.3) | 317 204 | (25.4) | 503 572 | (19.6) | 13 823 | (7.5) |

| Anxiety | 517 012 | (18.8) | 309 583 | (20.6) | 207 429 | (16.6) | 462 526 | (18.0) | 54 486 | (29.4) |

| COPD | 489 461 | (17.8) | 239 542 | (15.9) | 249 919 | (20.0) | 459 359 | (17.9) | 30 102 | (16.2) |

| Major depression | 433 809 | (15.8) | 266 357 | (17.8) | 167 452 | (13,4) | 383 146 | (14.9) | 50 663 | (27.3) |

The eleven most frequent chronic disease identified in the birth cohort are listed. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

We applied PROMPT criteria inside the target age of our population, patients aged 49–64, and we found the prevalence of having at least one PIMs was 14.0% among patients with 0–4 medications, 62.2% in patients with polypharmacy, 86.1% in patients with hyperpolypharmacy. Most common PIMs were proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; respectively 6.2% of patients with 0–4 medications, 30.1% of patients with polypharmacy, 48.5% with hyperpolypharmacy), non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, 3.2%, 14.8%, 25.2%), sulfonylureas (1.5%, 12.4%, 19.4%), opioids without concurrent laxatives (1.5%, 7.2%, 13.5%), stimulant laxative (0.5%, 4.9%, 18.0%) and benzodiazepines (0.9%, 5.4%, 12.7%). When we applied Beers Laroche in this same age group we found PIMs prevalences of 14.3%, 63.4% 85.7% respectively. Similarly, the most common PIMs were PPIs (5.9%, 26.3%, 34.6%), sulfonylureas (1.5%, 12.4%, 19.5%), NSAIDs (2.9%, 11.6%, 15.4%), stimulant laxatives (0.5%, 5.6%, 21.3%) and benzodiazepines (0.6%, 3.6%, 8.7%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

prevalences of most common potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by either combined Beers Laroche and prevalances of most common PIMs defined by PROMPT criteria in US veteran patients aged 49–70 years according to polypharmacy in 2016

| Birth cohort | 49 – 64 years old | 65 – 70 years old | ||||||||||

| N total | 2 748 705 | 1 499 586 | 1 249 119 | |||||||||

| N 0 – 4 medications | 1 914 269 | 1 116 351 | 797 918 | |||||||||

| N 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 633 061 | 296 032 | 337 029 | |||||||||

| N ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 201 375 | 87 203 | 114 172 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Beers Laroche | PROMPT | Beers Laroche | PROMPT | Beers Laroche | PROMPT | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potentially inappropriate medications - Overall – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 277 690 | (14.5) | 267 697 | (14.0) | 159 886 | (14.3) | 156 665 | (14.0) | 117 804 | (14.8) | 111 032 | (13.9) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 389 499 | (61.5) | 377 738 | (59.7) | 187 556 | (63.4) | 184 248 | (62.2) | 201 943 | (59.9) | 193 490 | (57.4) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 169 842 | (84.3) | 168 727 | (83.8) | 74 734 | (85.7) | 75 106 | (86.1) | 95 108 | (83.3) | 93 621 | (82.0) |

| Pump Proton Inhibitors – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 121 209 | (6.3) | 125 541 | (6.6) | 66 336 | (5.9) | 69 151 | (6.2) | 54 873 | (6.9) | 56 390 | (7.1) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 164 208 | (25.9) | 185 205 | (29.3) | 77 805 | (26.3) | 89 224 | (30.1) | 86 403 | (25.6) | 95 981 | (28.5) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 68 155 | (33.8) | 93 347 | (46.4) | 30 158 | (34.6) | 42 307 | (48.5) | 37 997 | (33.3) | 51 040 | (44.7) |

| Sulfonylureas – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 33 507 | (1.8) | 33 507 | (1.8) | 16 662 | (1.5) | 16 662 | (1.5) | 16 845 | (2.1) | 16 845 | (2.1) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 90 115 | (14.2) | 90 115 | (14.2) | 36 610 | (12.4) | 36 610 | (12.4) | 53 505 | (15.9) | 53 505 | (15.9) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 45 385 | (22.5) | 45 385 | (22.5) | 17 032 | (19.5) | 17 032 | (19.5) | 28 353 | (24.8) | 28 353 | (24.8) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 47 206 | (2.5) | 51 821 | (2.7) | 32 180 | (2.9) | 35 205 | (3.2) | 15 026 | (1.9) | 16 616 | (2.1) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 58 667 | (9.3) | 75 420 | (11.9) | 34 237 | (11.6) | 43 846 | (14.8) | 24 430 | (7.3) | 31 574 | (9.4) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 25 277 | (12.6) | 41 398 | (20.6) | 13 455 | (15.4) | 21 928 | (25.2) | 11 822 | (10.4) | 19 470 | (17.1) |

| Opioids without concurrent laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | - | 22 250 | (1.2) | - | 16 295 | (1.5) | - | 5 955 | (0.8) | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | - | 33 187 | (5.2) | - | 21 425 | (7.2) | - | 11 762 | (3.5) | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | - | 20 993 | (10.4) | - | 11 789 | (13.5) | - | 9 204 | (8.1) | |||

| Stimulant Laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 9 415 | (0.5) | 8 752 | (0.5) | 5 654 | (0.5) | 5 221 | (0.5) | 3 761 | (0.5) | 3 531 | (0.4) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 32 182 | (5.1) | 28 904 | (4.6) | 16 574 | (5.6) | 14 609 | (4.9) | 15 608 | (4.6) | 14 295 | (4.2) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 39 982 | (19.9) | 34 634 | (17.2) | 18 564 | (21.3) | 15 658 | (18.0) | 21 418 | (18.8) | 18 976 | (16.6) |

| Insulin sliding scale – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 16 369 | (0.9) | - | 8 482 | (0.8) | - | 7 887 | (1.0) | - | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 35 024 | (5.5) | - | 15 127 | (5.1) | - | 19 897 | (5.9) | - | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 23 431 | (11.6) | - | 9 125 | (10.5) | - | 14 306 | (12.5) | - | |||

| Antidepressants– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 16 401 | (0.9) | - | 9 763 | (0.8) | - | 6 638 | (0.8) | ||||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 27 634 | (4.4) | - | 13 996 | (4.7) | - | 13 638 | (4.0) | ||||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 18 646 | (9.3) | - | 8 994 | (10.3) | - | 9 652 | (8.5) | ||||

| Benzodiazepines, Long and Intermediate/ short acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 11 694 | (0.6) | 17 569 | (0.9) | 6 928 | (0.6) | 10 424 | (0.9) | 4 766 | (0.6) | 7 145 | (0.9) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 20 059 | (3.2) | 29 460 | (4.7) | 10 772 | (3.6) | 15 937 | (5.4) | 9 287 | (2.8) | 13 523 | (4.0) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 15 560 | (7.7) | 22 414 | (11.1) | 7 610 | (8.7) | 11 102 | (12.7) | 7 950 | (7.0) | 11 312 | (9.9) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (PIMs) used in combination with venlafaxine. – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | - | 13 025 | (0.7) | - | 8 361 | (0.8) | - | 4 664 | (0.6) | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | - | 20 403 | (3.2) | - | 10 991 | (3.7) | - | 9 412 | (2.8) | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | - | 13 825 | (6.9) | - | 6 678 | (7.7) | - | 7 147 | (6.3) | |||

| First-generation antihistamines– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 788 | (0.5) | 8 788 | (0.5) | 5 609 | (0.5) | 5 609 | (0.5) | 3 179 | (0.4) | 3 179 | (0.4) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 137 | (2.9) | 18 137 | (2.9) | 10 305 | (3.5) | 10 305 | (3.5) | 7 832 | (2.3) | 7 832 | (2.3) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 231 | (8.6) | 17 231 | (8.6) | 9 024 | (10.4) | 9 024 | (10.4) | 8 207 | (7.2) | 8 207 | (7.2) |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 7 725 | (0.4) | - | 5 773 | (0.5) | - | 1 952 | (0.2) | - | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 493 | (2.9) | - | 12 381 | (4.2) | - | 6 112 | (1.8) | - | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 513 | (8.7) | - | 10 229 | (11.7) | - | 7 284 | (6.4) | - | |||

| Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (Z-drugs) – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 543 | (0.5) | 8 543 | (0.5) | 4 990 | (0.5) | 4 990 | (0.5) | 3 553 | (0.5) | 3 553 | (0.5) |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 14 407 | (2.3) | 14 407 | (2.3) | 7 599 | (2.6) | 7 599 | (2.6) | 6 808 | (2.0) | 6 808 | (2.0) |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 10 236 | (5.1) | 10 236 | (5.1) | 5 170 | (5.9) | 5 170 | (5.9) | 5 066 | (4.4) | 5 066 | (4.4) |

| Corticoids without concomitant bisphosphonate – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | - | 3 586 | (0.2) | - | 1 815 | (0.2) | - | 1 771 | (0.2) | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | - | 7 151 | (1.1) | - | 3 138 | (1.1) | - | 4 013 | (1.2) | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | - | 6 141 | (3.1) | - | 2 593 | (3.0) | - | 3 548 | (3.1) | |||

| Cardio-selective calcium-channel blockers (verapamil or Diltiazem) used in combination with beta-adrenoceptor blocking drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | - | 1 792 | (0.1) | - | 776 | (0.1) | - | 1 016 | (0.1) | |||

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | - | 7 541 | (1.2) | - | 2 860 | (1.0) | - | 4 681 | (1.4) | |||

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | - | 5 758 | (2.9) | - | 2 113 | (2.4) | - | 3 645 | (3.2) | |||

We applied the Beers Laroche criteria inside target age of our population, patients aged 65–70, and we found PIMs prevalences of 14.8% in patients taking 0 −4 medications, 59.9% in patients with polypharmacy, 83.3% in patients with hyperpolypharmacy. The most common PIMs were PPIs (6.9% of patients taking 0–4 medications, 25.6% of patients with polypharmacy, 33.3% of patients with hyperpolypharmacy), sulfonylureas (2.1%, 15.9%, 24.8%), NSAIDs (1.9%,7.3%, 10.4%), stimulant laxatives (0.5%, 4.6%, 18.8%), insulin sliding scale (1.0%, 5.9%, 12.5%), antidepressants (0.8%,4.0%, 8.5%) followed by benzodiazepines (0.6% 2.8%, 7.0%). When we applied the PROMPT criteria in this same age group, we found prevalences of 13.9%, 57.4% and 82.0% respectively. Similar common PIMs were found: PPIs (7.1%, 28.5%, 44.7%), sulfonylureas (2.1%, 15.9%, 24.8), NSAIDs (2.1%, 9.4%, 17.1%), stimulant laxatives (0.4%, 4.2%, 16.6%) and benzodiazepines (0.9%, 4.0%, 9.9%) (Table 2)

Among patients with 0 −4 medications, PIMs prevalence were similar between patients aged 49–64 and patients aged 65 – 70 according to both Beers Laroche (14.3% vs. 14.8%, SMD = 0.01) and PROMPT criteria (14.0% vs. 13.9%, SMD = 0.00). Among those with polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy, The Beers Laroche criteria showed no differences in PIMs prevalence according to age (63.4% vs. 59.9%, SMD = 0.07 and 85.7% vs. 83.3%, SMD = 0.07 respectively) but PROMPT criteria showed small differences (62.2% vs. 57.4%, SMD = 0.10 and 86.1% vs. 82.0%, SMD = 0.11, respectively) suggesting that patients aged 49 – 64 had a higher PIMs prevalence than patients aged 65–70. Small differences of PIMs prevalence were observed according to sex with a higher prevalence in women than men in polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy according to the Beers Laroche criteria (68.6% vs. 61.1%, SMD = 0.16 and 89.2% vs. 84.1%, SMD = 0.15 respectively) and PROMPT criteria (66.1% vs. 59.3% SMD = 0.14 and 89.0% vs. 83.5% SMD = 0.16). Differences existed according to race/ethnicity: For instance according to PROMPT, White and Black patients had small differences compared to non-White and non-Black, White patients having higher prevalence compared to Black, Hispanic and other race/ethnicity (61.7% vs. 54.5% of patients with polymarmacy, SMD = 0.15; 84.7% vs. 81.0% of patients with hyperpolypharmacy, SMD = 0.10) and Black lower prevalence than White, Hispanic and other race/ethnicity (52.3% vs. 61.4% of patients with polymarmacy, SMD = 0.19; 79.8% vs. 84.6% of patients with hyperpolypharmacy, SMD = 0.13) (Tables 3 – 6, Tables S5 – S8).

Table 3.

Prevalence of most frequent potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

| Birth cohort | 49 – 64 years old | 65 – 70 years old | SMD | Men | Women | SMD | ||||||

| N total | 2 748 705 | 1 499 586 | 1 249 119 | 2 563 239 | 185 466 | |||||||

| N 0 – 4 medications | 1 914 269 | 1 116 351 | 797 918 | 1 774 904 | 139 365 | |||||||

| N 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 633 061 | 296 032 | 337 029 | 597 938 | 35 123 | |||||||

| N ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 201 375 | 87 203 | 114 172 | 190 397 | 10 978 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potentially inappropriate medications - Overall – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 277 690 | (14.5) | 159 886 | (14.3) | 117 804 | (14.8) | 0.01 | 255 845 | (14.4) | 21 845 | (15.7) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 389 499 | (61.5) | 187 556 | (63.4) | 201 943 | (59.9) | 0.07 | 365 417 | (61.1) | 24 082 | (68.6) | 0.16* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 169 842 | (84.3) | 74 734 | (85.7) | 95 108 | (83.3) | 0.07 | 160 045 | (84.1) | 9 797 | (89.2) | 0.15* |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 121 209 | (6.3) | 66 336 | (5.9) | 54 873 | (6.9) | 0.04 | 112 634 | (6.4) | 8 575 | (6.2) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 164 208 | (25.9) | 77 805 | (26.3) | 86 403 | (25.6) | 0.01 | 153 578 | (25.7) | 10 630 | (30.3) | 0.10* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 68 155 | (33.8) | 30 158 | (34.6) | 37 997 | (33.3) | 0.02 | 63 723 | (33.5) | 4 432 | (40.4) | 0.14* |

| Sulfonylureas – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 33 507 | (1.8) | 16 662 | (1.5) | 16 845 | (2.1) | 0.05 | 32 274 | (1.8) | 1 233 | (0.9) | 0.08 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 90 115 | (14.2) | 36 610 | (12.4) | 53 505 | (15.9) | 0.10* | 87 517 | (14.6) | 2 598 | (7.4) | 0.23* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 45 385 | (22.5) | 17 032 | (19.5) | 28 353 | (24.8) | 0.13* | 43 986 | (23.1) | 1 399 | (12.7) | 0.27* |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 47 206 | (2.5) | 32 180 | (2.9) | 15 026 | (1.9) | 0.07 | 43 022 | (2.4) | 4 184 | (3.0) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 58 667 | (9.3) | 34 237 | (11.6) | 24 430 | (7.3) | 0.15* | 54 107 | (9.1) | 4 560 | (13.0) | 0.13 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 25 277 | (12.6) | 13 455 | (15.4) | 11 822 | (10.4) | 0.15* | 23 341 | (12.3) | 1 936 | (17.6) | 0.15 |

| Stimulant Laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 9 415 | (0.5) | 5 654 | (0.5) | 3 761 | (0.5) | 0.01 | 8 352 | (0.5) | 1 063 | (0.8) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 32 182 | (5.1) | 16 574 | (5.6) | 15 608 | (4.6) | 0.04 | 29 526 | (4.9) | 2 656 | (7.6) | 0.11* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 39 982 | (19.9) | 18 564 | (21.3) | 21 418 | (18.8) | 0.06 | 37 108 | (19.5) | 2 874 | (26.2) | 0.16* |

| Insulin sliding scale – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 16 369 | (0.9) | 8 482 | (0.8) | 7 887 | (1.0) | 0.02 | 15 583 | (0.9) | 786 | (0.6) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 35 024 | (5.5) | 15 127 | (5.1) | 19 897 | (5.9) | 0.03 | 33 728 | (5.6) | 1 296 | (3.7) | 0.09 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 23 431 | (11.6) | 9 125 | (10.5) | 14 306 | (12.5) | 0.06 | 22 677 | (11.9) | 754 | (6.9) | 0.17* |

| Antidepressants– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 16 401 | (0.9) | 9 763 | (0.8) | 6 638 | (0.8) | 0.00 | 14 364 | (0.8) | 2 037 | (1.5) | 0.06 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 27 634 | (4.4) | 13 996 | (4.7) | 13 638 | (4.0) | 0.03 | 25 045 | (4.2) | 2 589 | (7.4) | 0.14* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 18 646 | (9.3) | 8 994 | (10.3) | 9 652 | (8.5) | 0.06 | 17 152 | (9.0) | 1 494 | (13.6) | 0.15* |

| Benzodiazepines - Short/intermediate acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 3 672 | (0.2) | 1 856 | (0.2) | 1 816 | (0.2) | 0.01 | 3 374 | (0.2) | 298 | (0.2) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 6 520 | (1.0) | 2 990 | (1.0) | 3 530 | (1.1) | 0.00 | 6 141 | (1.0) | 379 | (1.1) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 4 835 | (2.4) | 2 016 | (2.3) | 2 819 | (2.5) | 0.01 | 4 577 | (2.4) | 258 | (2.4) | 0.00 |

| Benzodiazepines - Long acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 073 | (0.4) | 5 103 | (0.5) | 2 970 | (0.4) | 0.01 | 7 280 | (0.4) | 793 | (0.6) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 13 714 | (2.2) | 7 870 | (2.7) | 5 844 | (1.7) | 0.06 | 12 604 | (2.1) | 1 110 | (3.2) | 0.07 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 10 902 | (5.4) | 5 680 | (6.5) | 5 222 | (4.6) | 0.08 | 10 114 | (5.3) | 788 | (7.2) | 0.08 |

| First-generation antihistamines– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 788 | (0.5) | 5 609 | (0.5) | 3 179 | (0.4) | 0.02 | 7 691 | (0.4) | 1 097 | (0.8) | 0.05 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 137 | (2.9) | 10 305 | (3.5) | 7 832 | (2.3) | 0.07 | 16 349 | (2.7) | 1 788 | (5.1) | 0.12* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 231 | (8.6) | 9 024 | (10.4) | 8 207 | (7.2) | 0.11* | 15 637 | (8.2) | 1 594 | (14.5) | 0.20* |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 7 725 | (0.4) | 5 773 | (0.5) | 1 952 | (0.2) | 0.04 | 6 746 | (0.4) | 979 | (0.7) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 493 | (2.9) | 12 381 | (4.2) | 6 112 | (1.8) | 0.14* | 16 466 | (2.8) | 2 027 | (5.8) | 0.15* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 513 | (8.7) | 10 229 | (11.7) | 7 284 | (6.4) | 0.19* | 15 777 | (8.3) | 1 736 | (15.8) | 0.23* |

| Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (Z-drugs) – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 543 | (0.5) | 4 990 | (0.5) | 3 553 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 7 651 | (0.4) | 892 | (0.6) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 14 407 | (2.3) | 7 599 | (2.6) | 6 808 | (2.0) | 0.04 | 13 220 | (2.2) | 1 187 | (3.4) | 0.07 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 10 236 | (5.1) | 5 170 | (5.9) | 5 066 | (4.4) | 0.07 | 9 508 | (5.0) | 728 | (6.6) | 0.07 |

Standardized Mean Difference were interpreted as: < 0.1 no difference; 0.2 small difference; 0.5 moderate difference; 0.8 large difference

Table 6.

Prevalence of most frequent potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

| White | SMD | Black | SMD | Hispanic | SMD | Other | SMD | |||||

| N total | 1 888 697 | 558 521 | 164 378 | 137 109 | ||||||||

| N 0 – 4 medications | 1 285 126 | 403 806 | 116 673 | 108 664 | ||||||||

| N 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 453 487 | 120 885 | 36 698 | 21 991 | ||||||||

| N ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 150 084 | 33 830 | 11 007 | 6 454 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potentially inappropriate medications - Overall – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 198 137 | (15.4) | 0.13* | 43 042 | (10.7) | 0.13* | 15 670 | (13.4) | 0.02 | 10 848 | (10.0) | 0.13* |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 279 796 | (61.7) | 0.15* | 63 157 | (52.3) | 0.19* | 21 582 | (58.8) | 0.02 | 13 203 | (60.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 127 166 | (84.7) | 0.10* | 26 991 | (79.8) | 0.13* | 9 139 | (83.0) | 0.02 | 5 431 | (84.2) | 0.01 |

| Pump Proton Inhibitors – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 97 342 | (7.6) | 0.13* | 17 171 | (4.3) | 0.13* | 6 418 | (5.5) | 0.05 | 4 610 | (4.2) | 0.11* |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 142 067 | (31.3) | 0.16* | 27 790 | (23.0) | 0.18* | 9 262 | (25.2) | 0.10* | 6 086 | (27.7) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 72 119 | (48.1) | 0.13* | 13 594 | (40.2) | 0.14* | 4 719 | (42.9) | 0.07 | 2 915 | (45.2) | 0.02 |

| Non–cyclooxygenase-selective NSAIDs, oral – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 37 026 | (2.9) | 0.03 | 9 578 | (2.4) | 0.03 | 2 785 | (2.4) | 0.02 | 2 432 | (2.3) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 55 997 | (12.4) | 0.05 | 12 600 | (10.4) | 0.06 | 3 829 | (10.4) | 0.05 | 2 994 | (13.6) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 31 350 | (20.9) | 0.03 | 6 346 | (18.8) | 0.05 | 2 161 | (19.6) | 0.02 | 1 541 | (23.9) | 0.08 |

| Sulfonylureas, long acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 21 727 | (1.7) | 0.01 | 7 064 | (1.8) | 0.00 | 3 115 | (2.7) | 0.07 | 1 601 | (1.5) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 63 963 | (14.1) | 0.01 | 15 924 | (13.2) | 0.04 | 6 764 | (18.4) | 0.12* | 3 464 | (15.8) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 33 804 | (22.5) | 0.00 | 7 331 | (21.7) | 0.03 | 2 730 | (24.8) | 0.06 | 1 520 | (23.6) | 0.02 |

| Opioids without concurrent laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 16 949 | (1.3) | 0.05 | 3 316 | (0.8) | 0.04 | 1 097 | (0.9) | 0.02 | 888 | (0.8) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 25 855 | (5.7) | 0.08 | 4 742 | (3.9) | 0.08 | 1 480 | (4.0) | 0.06 | 1 110 | (5.1) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 16 736 | (11.2) | 0.10* | 2 723 | (8.1) | 0.10* | 923 | (8.4) | 0.07 | 611 | (9.5) | 0.03 |

| Benzodiazepines, Long and short acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 14 596 | (1.1) | 0.07 | 1 296 | (0.3) | 0.09 | 1 050 | (0.9) | 0.00 | 627 | (0.6) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 24 268 | (5.4) | 0.12* | 2 446 | (2.0) | 0.17* | 1 904 | (5.2) | 0.03 | 842 | (3.8) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 18 149 | (12.1) | 0.13* | 1 990 | (5.9) | 0.22* | 1 622 | (14.7) | 0.11* | 653 | (10.1) | 0.03 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors used in combination with venlafaxine. – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 10 371 | (0.8) | 0.05 | 1 425 | (0.4) | 0.09 | 711 | (0.6) | 0.00 | 518 | (0.5) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 16 660 | (3.7) | 0.10* | 2 061 | (1.7) | 0.17* | 1 016 | (2.8) | 0.03 | 666 | (3.0) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 11 308 | (7.5) | 0.11* | 1 364 | (4.0) | 0.22* | 721 | (6.6) | 0.11* | 432 | (6.7) | 0.03 |

| Anticholinergics , First-generation antihistamines – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 5982 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 1 844 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 555 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 407 | (0.4) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 12817 | (2.8) | 0.01 | 3 522 | (2.9) | 0.00 | 1 131 | (3.1) | 0.01 | 667 | (3.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 12794 | (8.5) | 0.00 | 2 832 | (8.4) | 0.01 | 989 | (9.0) | 0.02 | 616 | (9.5) | 0.04 |

| Stimulant Laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 5 030 | (0.4) | 0.03 | 2 730 | (0.7) | 0.04 | 683 | (0.6) | 0.02 | 309 | (0.3) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 112 | (4.0) | 0.09 | 7 870 | (6.5) | 0.11* | 1 963 | (5.4) | 0.04 | 959 | (4.4) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 24 028 | (16.0) | 0.12* | 7 454 | (22.0) | 0.15* | 2 077 | (18.9) | 0.05 | 1 075 | (16.7) | 0.01 |

| Nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics (Z-drugs) – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 6 666 | (0.5) | 0.03 | 981 | (0.2) | 0.04 | 543 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 353 | (0.3) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 11 319 | (2.5) | 0.05 | 1 713 | (1.4) | 0.08 | 875 | (2.4) | 0.01 | 500 | (2.3) | 0.00 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 8 014 | (5.3) | 0.05 | 1 226 | (3.6) | 0.08 | 693 | (6.3) | 0.06 | 303 | (4.7) | 0.02 |

| Corticoids without concomitant bisphosphonate – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 2 551 | (0.2) | 0.01 | 727 | (0.2) | 0.00 | 180 | (0.2) | 0.01 | 128 | (0.1) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 5 218 | (1.2) | 0.01 | 1 358 | (1.1) | 0.00 | 342 | (0.9) | 0.02 | 233 | (1.1) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 4 531 | (3.0) | 0.01 | 1 105 | (3.3) | 0.01 | 317 | (2.9) | 0.01 | 188 | (2.9) | 0.01 |

| Cardio-selective calcium-channel blockers (verapamil or Diltiazem) used in combination with beta-adrenoceptor blocking drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 1 359 | (0.1) | 0.01 | 304 | (0.1) | 0.01 | 56 | (0.1) | 0.02 | 73 | (0.1) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 5 821 | (1.3) | 0.03 | 1 236 | (1.0) | 0.02 | 248 | (0.7) | 0.06 | 236 | (1.1) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 4 522 | (3.0) | 0.04 | 895 | (2.7) | 0.02 | 192 | (1.7) | 0.08 | 149 | (2.3) | 0.04 |

Standardized Mean Difference were interpreted as: < 0.1 no difference; 0.2 small difference; 0.5 moderate difference; 0.8 large difference

Small differences in prevalence of the most common PIMs were observed between age, sex and race/ethnicity. If looking only in patients with polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy, patients aged 49 – 64 had higher prevalence of NSAIDs (SMD between 0.15 – 0.20), skeletal muscle relaxants (0.14 – 0.19), opioids (0.17 – 0.18) and lower prevalence of sulfonylureas (0.10 – 0.13) than patients aged 65–70. Similarly, women had higher prevalence of NSAIDs (0.13 – 0.20), PPIs (0.10 – 0.18), skeletal muscle relaxants (0.15 – 0.23), antidepressants (0.14 – 0.19), benzodiazepines (0.10 – 0.12), antihistamines (0.12 – 0.20), stimulant laxatives (0.10 – 0.16) and lower prevalence of sulfonylureas (0.23 – 0.27) and insulin sliding scale (0.17) than men. Similarly, White had higher prevalence of PPIs (0.13 – 0.17) and opioids (0.10) than non-White, and Black lower prevalence of PPIs (0.14 – 0.18), opioids (0.10), antidepressants (0.10) and benzodiazepines than non-Black (0.14 – 0.22) (most frequent PIMs presented in Table 2 - 6, all PIMs are presented in Table S5 – S8).

Discussion

Approximately six in ten patients with polypharmacy and eight in ten patients with hyperpolypharmacy were exposed to PIMs by either Beers Laroche criteria targeting older people or PROMPT criteria targeting middle-aged people. PROMPT criteria showed small differences in PIMs prevalence between patients aged 49 – 64 and patients aged 65 – 70, while no difference existed with Beers Laroche criteria. Women were more exposed to PIMs than men and White more than all other race/ethnicities but these differences were largely driven by number of medications prescribed. Once analyses were stratified by polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy, differences were small. Both PIMS criteria identified similar common PIMs such as PPIs, sulfonylureas, NSAIDs, antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Small differences of patterns existed according to age, sex and race.

Most previous PIMs research was focused on people of 65 years of age and older even though some included information on younger people [15,16,22,23]. In our study we observed that PIMs were as prevalent in people <65 as in older people. The prevalence of PIMs observed in younger individuals should raise concern. It has been seen in other studies such as in Japan where PIMs concerned 71.9% of patients older than 45 and receiving care at home [22] and in a study in the Netherlands that showed that younger patient were subjected to a higher prevalence of PIMs than older patients with polypharmacy between 2012 and 2016 [16]. This suggests that initiation of PIMs in younger patients with polypharmacy is an increasing concern.

Most studies used criteria according to the age of the studied population, i.e., Beers and Laroche for older patients and PROMPT for middle-aged patients. Beers criteria were created for individuals aged 65 and over, the Laroche list for individuals aged 75 and over, and PROMPT criteria were created for middle-aged people aged 45 to 64. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to show that the use of either Beers Laroche or PROMPT criteria in a population aged 49–70 provides similar estimations whether applied in the target population or not. We observed a high prevalence that increased with polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy with any criteria and at any age category. This suggest that these criteria may be used in both middle aged and older people regardless of the initial target population. These criteria also provided close estimations of PIMs prevalence in analysis stratified by sex and race/ethnicity. Another argument is that all these medications may be pharmacologically inappropriate in anyone when used chronically.

Previous PIMs research used to be conducted in small samples of patients, often those who visited or were discharged from a single hospital, so may not be generalizable. However, new population-based study such as ours described similar common PIMs. Benzodiazepines, analgesics, NSAID and PPIs were showed in two small sized study in Spain [24,25]. Proportion of the lists that was actually used may also vary between studies but results stayed consistent and similar to ours. Similarly, two studies employing somewhat different applications of Beers criteria use showed that gastrointestinal medications including PPIs were among the most frequent PIMs in older people (≥ 65 years old) in two different hospitals in 2016, one in Jordan [26] and one in Saudi Arabia [27]. PPIs were identified as the major PIMs regardless of the subcategories of Beers criteria use. Studies using PROMPT showed similar results to ours: In the United Kingdom (UK), France and the Netherlands, proton pump inhibitors, benzodiazepines were among the most frequent PIMs[14–16,23]. These similarities suggest that those common PIMs are a feature of polypharmacy.

Identification of inappropriate PPIs according to Beers/Laroche and PROMPT criteria sometimes demands clinical data such as conditions that justified the chronic use of a PPI (esophagitis, Helicobacter pylori) or other drugs. From the VA data we could identify these specific clinical conditions but it was not possible to distinguish antiplatelet aspirin (only low-dose aspirin) from analgesics (either low-dose or high dose). Consequently, we considered PPIs used concurrently with low-dose aspirin (antiplatelet) always appropriate even though they are not, leading to a possible underestimation of PIMs. Despite this, the prevalence of PPIs remains high in our study, similarly to what was observed in France [15], the Netherlands [16] Spain [24] and the UK [23].

Beers Laroche and PROMPT criteria overlap with slight differences which helped us to better understand PIMs use. In addition to oesophagitis and helicocter, PPIs were considered appropriate if used concomitantly with a chronic NSAID or oral corticoids with Beers Laroche criteria but not with PROMPT criteria. Furthermore, Beers Laroche criteria listed specific NSAIDs contrary to PROMPT that would consider NSAIDs overall. The close estimations between our criteria suggested that most people used chronically PPIs without NSAIDs, and vice versa. PPIs and NSAIDs are known to be frequently initiated at the same time, often without following the recommendations, i.e. without gastrointestinal risk factors [28,29]. Once either PPIs or NSAIDs have been discontinued, treatment is probably rarely re-evaluated, leading to chronic and inappropriate use of either treatment.

Benzodiazepines and hypnotics are often reported as the most common PIMs for instance in Korea [30] and in most European countries (Spain [25], France [15,31], the Netherlands [16], Lithuania [32],Finland [33], Germany [34] and Scotland [35]). Our data allowed the identification of patients with chronic anxiety, a condition for which Beers Laroche criteria considers short acting benzodiazepines appropriate, contrary to the PROMPT criteria [12,14]. Close prevalences between criteria suggest that anxiety cannot explain the high use of these drugs by itself, in our study and in Europe, despite the risks of associated adverse effects [36–39].

The study had limitations largely related to the data source and population. The Veteran Birth Cohort included patients aged 49 to 70 as of October 2015; therefore, our findings may not generalize to patients aged younger than 49 or older than 70. Although the cohort included proportionally few women (∼7%), the large nature of our study meant this translated to 185,466 women; though, our findings may not generalize to women in the general population. Given the cohort was mostly men, overall estimates of the prevalence of PIMs is likely to be an underestimate of the prevalence in the general population since medication use is, in part, driven by sex and gender (e.g., estrogens are frequently prescribed PIMs [40]). Importantly, we found a small difference of PIMS prevalence in sex-stratified analyses for medication usually not driven by sex such as a higher prevalence of antidiabetic PIMs in men compared to women, and a higher prevalence of central nervous system PIMs in women compared to men. Dose and indication of treatment were not available which limited full use of some of the Beers Laroche and PROMPT criteria. For instance, PROMPT criteria say that PPIs should not be used at doses above the recommended maintenance dosage for greater than eight weeks, so we only took account of the duration of treatment. In addition, some clinical data might be inconsistently coded (e.g., anxiety is rarely coded using ICD-9 codes so prevalences of Benzodiazepines – short/intermediate acting PIMs might be overestimated). Over-the-counter medications and medications dispensed outside of the VA were not available, which could have resulted in the underestimation of the true prevalence. However, our analysis included patients with active use and an established clinical history in the VA and assumed most patients have received most or all of their medications through the VA, which minimized the potential risk for underestimation.

This study was reported using the observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE; Table S9) [41]. A comparative table with all studies cited in this discussion is available in supplementary materials (Table S10).

Conclusion

PIMs prevalence was high and increased with polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy in US veterans aged 49 −70. Beers, Laroche and PROMPT criteria provides very close estimation of PIMs prevalence if they are used either inside or outside their target age (middle age or older patients). Furthermore, regardless of the criteria used, differences in PIMs prevalence between patients aged 49 – 64 and patients aged 65 – 70 were small or absent, suggesting that PIMs exposure should be addressed as well in middle aged people as in older people. The most common PIMs were gastrointestinal such as PPIs and stimulant laxatives, antidiabetics such as sulfonylureas and insulin sliding scale, analgesics and psychotropics such as NSAIDs, opioids, benzodiazepines and antidepressants. These medications should be prioritized for deprescribing interventions, especially among patients with polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy. Small differences in patterns were observed according to sex and race ethnicity suggesting that intervention should target every patient with polypharmacy regardless of age, sex and race.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Drugs identified as potentially inappropriate medications defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria according to the VA generic name and specific requirement of the definition.

Table S2 Drugs identified as potentially inappropriate medications defined by PROMPT criteria according to the VA generic name and specific requirement of the definition.

Table S3 Codes from the International classification of disease 9th edition (ICD 9th) used to identify most frequent chronic diseases and clinical requirements.

Table S4 Characteristics of included patient aged 49 – 70 according to race/ethnicity

Table S5 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S6 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to race and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S7 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S8 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to race and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S10 Prevalences of PIMs defined by Beers, Laroche and PROMPT criteria according to polypharmacy in previous international studies

Table S9 The RECORD statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE) checklist of items, extended from the STROBE and RECORD statements, which should be reported in non-interventional pharmacoepidemiological studies using routinely collected health data

Table 4.

Prevalence of most frequent potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to race and polypharmacy in 2016

| White | SMD | Black | SMD | Hispanic | SMD | Other | SMD | |||||

| N total | 1 888 697 | 558 521 | 164 378 | 137 109 | ||||||||

| N 0 – 4 medications | 1 285 126 | 403 806 | 116 673 | 108 664 | ||||||||

| N 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 453 487 | 120 885 | 36 698 | 21 991 | ||||||||

| N ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 150 084 | 33 830 | 11 007 | 6 454 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potentially inappropriate medications - Overall – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 202 287 | (15.7) | 0.11* | 47 364 | (11.7) | 0.00 | 16 829 | (14.4) | 0.00 | 11 210 | (10.3) | 0.13* |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 285 322 | (62.9) | 0.10* | 67 640 | (56.0) | 0.14* | 22 996 | (62.6) | 0.02 | 13 541 | (61.6) | 0.00 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 127 284 | (84.8) | 0.05 | 27 777 | (82.1) | 0.07 | 9 361 | (85.1) | 0.02 | 5 420 | (84.0) | 0.01 |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 94 189 | (7.3) | 0.13* | 16 447 | (4.1) | 0.13* | 6 165 | (5.3) | 0.05 | 4 408 | (4.1) | 0.11* |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 126 994 | (28.0) | 0.17* | 23 952 | (19.8) | 0.18* | 8 020 | (21.9) | 0.10* | 5 242 | (23.8) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 53 392 | (35.6) | 0.15* | 9 464 | (28.0) | 0.15* | 3 296 | (29.9) | 0.09 | 2 003 | (31.0) | 0.06 |

| Sulfonylureas – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 21 727 | (1.7) | 0.01 | 7 064 | (1.8) | 0.00 | 3 115 | (2.7) | 0.07 | 1 601 | (1.5) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 63 963 | (14.1) | 0.01 | 15 924 | (13.2) | 0.04 | 6 764 | (18.4) | 0.12* | 3 464 | (15.8) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 33 804 | (22.5) | 0.00 | 7 331 | (21.7) | 0.03 | 2 730 | (24.8) | 0.06 | 1 520 | (23.6) | 0.02 |

| Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 33 294 | (2.6) | 0.02 | 9 097 | (2.3) | 0.02 | 2 573 | (2.2) | 0.01 | 2 242 | (2.1) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 42 696 | (9.4) | 0.02 | 10 503 | (8.7) | 0.02 | 3 106 | (8.5) | 0.03 | 2 362 | (10.7) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 18 705 | (12.5) | 0.01 | 4 255 | (12.6) | 0.00 | 1 370 | (12.5) | 0.00 | 947 | (14.7) | 0.06 |

| Stimulant Laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 5 432 | (0.4) | 0.03 | 2 891 | (0.7) | 0.04 | 746 | (0.6) | 0.02 | 346 | (0.3) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 20 423 | (4.5) | 0.09 | 8 468 | (7.0) | 0.10* | 2 210 | (6.0) | 0.04 | 1 081 | (4.9) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 28 094 | (18.7) | 0.11* | 8 266 | (24.4) | 0.13* | 2 379 | (21.6) | 0.05 | 1 243 | (19.3) | 0.02 |

| Insulin sliding scale – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 11 270 | (0.9) | 0.01 | 3 112 | (0.8) | 0.01 | 1 371 | (1.2) | 0.03 | 616 | (0.6) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 24 941 | (5.5) | 0.01 | 6 069 | (5.0) | 0.03 | 2 906 | (7.9) | 0.10 | 1 108 | (5.0) | 0.02 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 463 | (11.6) | 0.00 | 3 538 | (10.5) | 0.04 | 1 717 | (15.6) | 0.12* | 713 | (11.1) | 0.02 |

| Antidepressants– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 12 642 | (1.0) | 0.04 | 2 155 | (0.5) | 0.05 | 946 | (0.8) | 0.01 | 658 | (0.6) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 21 657 | (4.8) | 0.07 | 3 494 | (2.9) | 0.10* | 1 550 | (4.2) | 0.01 | 933 | (4.3) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 14 624 | (9.7) | 0.07 | 2 421 | (7.2) | 0.09 | 1 047 | (9.5) | 0.01 | 554 | (8.6) | 0.02 |

| Benzodiazepines - Short/intermediate acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 2 991 | (0.2) | 0.03 | 321 | (0.1) | 0.04 | 248 | (0.2) | 0.00 | 112 | (0.1) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 5 222 | (1.2) | 0.04 | 615 | (0.5) | 0.07 | 474 | (1.3) | 0.03 | 209 | (1.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 3 841 | (2.6) | 0.04 | 499 | (1.5) | 0.08 | 374 | (3.4) | 0.06 | 121 | (1.9) | 0.04 |

| Benzodiazepines - Long acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 6 685 | (0.5) | 0.05 | 633 | (0.2) | 0.06 | 451 | (0.4) | 0.01 | 304 | (0.3) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 11 279 | (2.5) | 0.08 | 1 135 | (0.9) | 0.12* | 916 | (2.5) | 0.02 | 384 | (1.8) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 8 777 | (5.6) | 0.08 | 1 009 | (3.0) | 0.14* | 774 | (7.0) | 0.07 | 342 | (5.3) | 0.01 |

| First-generation antihistamines– n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 5 982 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 1 844 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 555 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 407 | (0.4) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 12 817 | (2.8) | 0.01 | 3 522 | (2.9) | 0.00 | 1 131 | (3.1) | 0.01 | 667 | (3.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 12 794 | (8.5) | 0.00 | 2 832 | (8.4) | 0.01 | 989 | (9.0) | 0.02 | 616 | (9.5) | 0.04 |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 5 726 | (0.5) | 0.02 | 1 302 | (0.3) | 0.02 | 346 | (0.3) | 0.02 | 351 | (0.3) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 14 182 | (3.1) | 0.04 | 2 886 | (2.4) | 0.04 | 700 | (1.9) | 0.07 | 725 | (3.3) | 0.02 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 13 666 | (9.1) | 0.06 | 2 547 | (7.5) | 0.05 | 718 | (6.5) | 0.09 | 582 | (9.0) | 0.01 |

| Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (Z-drugs) – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 6 666 | (0.5) | 0.03 | 981 | (0.2) | 0.04 | 543 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 353 | (0.3) | 0.02 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 11 319 | (2.5) | 0.05 | 1 713 | (1.4) | 0.08 | 875 | (2.4) | 0.01 | 500 | (2.3) | 0.00 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 8 014 | (5.3) | 0.05 | 1 226 | (3.6) | 0.08 | 693 | (6.3) | 0.06 | 303 | (4.7) | 0.02 |

Standardized Mean Difference were interpreted as: < 0.1 no difference; 0.2 small difference; 0.5 moderate difference; 0.8 large difference

Table 5.

Prevalence of most frequent potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

| Birth cohort | 49 – 64 years old | 65 – 70 years old | SMD | Men | Women | SMD | ||||||

| N total | 2 748 705 | 1 499 586 | 1 249 119 | 2 563 239 | 185 466 | |||||||

| N 0 – 4 medications | 1 914 269 | 1 116 351 | 797 918 | 1 774 904 | 139 365 | |||||||

| N 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 834 436 | 383 235 | 451 201 | 597 938 | 35 123 | |||||||

| N ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 201 375 | 87 203 | 114 172 | 190 397 | 10 978 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potentially inappropriate medications - Overall – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 267 697 | (14.0) | 156 665 | (14.0) | 111 032 | (13.9) | 0.00 | 246 895 | (13.9) | 20 802 | (14.9) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 377 738 | (59.7) | 184 248 | (62.2) | 193 490 | (57.4) | 0.10* | 354 534 | (59.3) | 23 204 | (66.1) | 0.14* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 168 727 | (83.8) | 75 106 | (86.1) | 93 621 | (82.0) | 0.11* | 158 962 | (83.5) | 9 765 | (89.0) | 0.16* |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 125 541 | (6.6) | 69 151 | (6.2) | 56 390 | (7.1) | 0.04 | 116 631 | (6.6) | 8 910 | (6.4) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 185 205 | (29.3) | 89 224 | (30.1) | 95 981 | (28.5) | 0.04 | 173 196 | (29.0) | 12 009 | (34.2) | 0.11 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 93 347 | (46.4) | 42 307 | (48.5) | 51 040 | (44.7) | 0.08 | 87 307 | (45.9) | 6 040 | (55.0) | 0.18 |

| Non–cyclooxygenase-selective NSAIDs, oral – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 51 821 | (2.7) | 35 205 | (3.2) | 16 616 | (2.1) | 0.07 | 47 256 | (2.7) | 4 565 | (3.3) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 75 420 | (11.9) | 43 846 | (14.8) | 31 574 | (9.4) | 0.17* | 69 535 | (11.6) | 5 885 | (16.8) | 0.14* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 41 398 | (20.6) | 21 928 | (25.2) | 19 470 | (17.1) | 0.20* | 38 252 | (20.1) | 3 146 | (28.7) | 0.20* |

| Sulfonylureas, long acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 33 507 | (1.8) | 16 662 | (1.5) | 16 845 | (2.1) | 0.04 | 32 274 | (1.8) | 1 233 | (0.9) | 0.08 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 90 115 | (14.2) | 36 610 | (12.4) | 53 505 | (15.9) | 0.10* | 87 517 | (14.6) | 2 598 | (7.4) | 0.23* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 45 385 | (22.5) | 17 032 | (19.5) | 28 353 | (24.8) | 0.13* | 43 986 | (23.1) | 1 399 | (12.7) | 0.27* |

| Opioids without concurrent laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 22 250 | (1.2) | 16 295 | (1.5) | 5 955 | (0.8) | 0.07 | 20 968 | (1.2) | 1 282 | (0.9) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 33 187 | (5.2) | 21 425 | (7.2) | 11 762 | (3.5) | 0.17* | 31 098 | (5.2) | 2 089 | (6.0) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 20 993 | (10.4) | 11 789 | (13.5) | 9 204 | (8.1) | 0.18* | 19 734 | (10.4) | 1 259 | (11.5) | 0.04 |

| Benzodiazepines, Long and short acting – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 17 569 | (0.9) | 10 424 | (0.9) | 7 145 | (0.9) | 0.00 | 15 809 | (0.9) | 1 760 | (1.3) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 29 460 | (4.7) | 15 937 | (5.4) | 13 523 | (4.0) | 0.06 | 27 031 | (4.5) | 2 429 | (6.9) | 0.10* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 22 414 | (11.1) | 11 102 | (12.7) | 11 312 | (9.9) | 0.09 | 20 763 | (10.9) | 1 651 | (15.0) | 0.12* |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors used in combination with venlafaxine. – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 13 025 | (0.7) | 8 361 | (0.8) | 4 664 | (0.6) | 0.02 | 10 584 | (0.6) | 2 441 | (1.8) | 0.10 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 20 403 | (3.2) | 10 991 | (3.7) | 9 412 | (2.8) | 0.05 | 17 911 | (3.0) | 2 492 | (7.1) | 0.19* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 13 825 | (6.9) | 6 678 | (7.7) | 7 147 | (6.3) | 0.05 | 12 599 | (6.6) | 1 226 | (11.2) | 0.16* |

| Anticholinergics , First-generation antihistamines – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 788 | (0.5) | 5 609 | (0.5) | 3 179 | (0.4) | 0.02 | 7 691 | (0.4) | 1 097 | (0.8) | 0.05 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 18 137 | (2.9) | 10 305 | (3.5) | 7 832 | (2.3) | 0.07 | 16 349 | (2.7) | 1 788 | (5.1) | 0.12* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 17 231 | (8.6) | 9 024 | (10.4) | 8 207 | (7.2) | 0.11* | 15 637 | (8.2) | 1 594 | (14.5) | 0.20* |

| Stimulant Laxatives – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 752 | (0.5) | 5 221 | (0.5) | 3 531 | (0.4) | 0.00 | 7 764 | (0.4) | 988 | (0.7) | 0.04 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 28 904 | (4.6) | 14 609 | (4.9) | 14 295 | (4.2) | 0.03 | 26 504 | (4.4) | 2 400 | (6.8) | 0.10* |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 34 634 | (17.2) | 15 658 | (18.0) | 18 976 | (16.6) | 0.04 | 32 108 | (16.9) | 2 526 | (23.0) | 0.15* |

| Nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics (Z-drugs) – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 8 543 | (0.5) | 4 990 | (0.5) | 3 553 | (0.5) | 0.00 | 7 651 | (0.4) | 892 | (0.6) | 0.03 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 14 407 | (2.3) | 7 599 | (2.6) | 6 808 | (2.0) | 0.04 | 13 220 | (2.2) | 1 187 | (3.4) | 0.07 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 10 236 | (5.1) | 5 170 | (5.9) | 5 066 | (4.4) | 0.07 | 9 508 | (5.0) | 728 | (6.6) | 0.07 |

| Corticoids without concomitant bisphosphonate – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 3 586 | (0.2) | 1 815 | (0.2) | 1 771 | (0.2) | 0.01 | 3 273 | (0.2) | 313 | (0.2) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 7 151 | (1.1) | 3 138 | (1.1) | 4 013 | (1.2) | 0.01 | 6 709 | (1.1) | 442 | (1.3) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 6 141 | (3.1) | 2 593 | (3.0) | 3 548 | (3.1) | 0.01 | 5 761 | (3.0) | 380 | (3.5) | 0.02 |

| Cardio-selective calcium-channel blockers (verapamil or Diltiazem) used in combination with beta-adrenoceptor blocking drugs – n(%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 4 medications | 1 792 | (0.1) | 776 | (0.1) | 1 016 | (0.1) | 0.02 | 1 699 | (0.1) | 93 | (0.1) | 0.01 |

| 5 – 9 medications (Polypharmacy) | 7 541 | (1.2) | 2 860 | (1.0) | 4 681 | (1.4) | 0.04 | 7 247 | (1.2) | 294 | (0.8) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 10 medications (Hyperpolypharmacy) | 5 758 | (2.9) | 2 113 | (2.4) | 3 645 | (3.2) | 0.05 | 5 541 | (2.9) | 217 | (2.0) | 0.06 |

Standardized Mean Difference were interpreted as: < 0.1 no difference; 0.2 small difference; 0.5 moderate difference; 0.8 large difference

Key points

Between 2015 and 2016, about 60% of United States (US) Veterans patients aged 49 to 70 years with polypharmacy and 80% with hyperpolypharmacy were exposed to potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs).

Beers, Laroche and PROMPT criteria provided similar estimation of PIMs prevalence both inside and outside their target age population.

The prevalence of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy was substantial even among those 49–64 years of age.

Meaningful differences in PIMs prevalence were observed between patients aged 49 – 64 and patients aged 65 −70 overall, but these were small among those with polypharmacy

Proton pump inhibitors, antidiabetics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, benzodiazepines and antidepressants represented the most common PIMs.

Small differences in PIMs prevalence were observed by sex and race/ethnicity.

Plain Language Summary

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are medications contra-indicated in particular circumstances. We sought to characterize PIMs by level of polypharmacy by age, sex and race/ethnicity.

We set up a study using electronic health records available through the US Department of Veterans Affairs. We analysed pharmacy fill and refill records between October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016 for all patients aged 49 to 70. PIMs were defined by lists of medications: the combined Beers and Laroche (henceforth Beers Laroche) criteria used for older patients and the PROMPT criteria used for middle-aged.

2 748 705 patients were included in the study. Among patients with 0–4, 5–9 and ≥10 medications about 14%, 60% and 85%, respectively, had at least one PIMs defined by PROMPT or Beers Laroche criteria. Small differences in prevalence were found by age. Meaningful differences in prevalence were shown by sex and race/ethnicity according to both set of criteria. The most common PIMs were digestive, analgesic, antidiabetic and psychotropic medications.

Prevalence of PIMs was high and increased with polypharmacy. Beers Laroche and PROMPT provided similar estimation inside and outside their target age, suggesting that PIMS are common among those with polypharmacy regardless of age.

Acknowledgements:

This publication does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding:

This work was supported by COMpAAAS/Veterans Aging Cohort Study, a CHAART Cooperative Agreement, supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (U24-AA020794, U01-AA020790, U01-AA020795; U10 AA013566-completed) and in kind by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work was also supported by a Fulbright Grant co-funded by the US government and the French government and by a Jean Walter Zellidja grant from the Académie Française.

Ethic statement:

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of VA Connecticut Healthcare System and Yale University. It has been granted a waiver of informed consent and is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Data availability statement:

Due to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) regulations and our ethics agreements, the analytic data sets used for this study are not permitted to leave the VA firewall without a Data Use Agreement. This limitation is consistent with other studies based on VA data. However, VA data are made freely available to researchers with an approved VA study protocol.

References

- 1.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, Mandl KD. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidem Drug Safe. 2010. Sep 1;19(9):901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallet L, Spinewine A, Huang A. The challenge of managing drug interactions in elderly people. The Lancet. 2007. Jul 14;370(9582):185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollason V, Vogt N. Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review of the role of the pharmacist. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(11):817–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011. May;20(5):514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojima T, Akishita M, Nakamura T, Nomura K, Ogawa S, Iijima K, et al. Association of polypharmacy with fall risk among geriatric outpatients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011. Oct;11(4):438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee A, Mbamalu D, Ebrahimi S, Khan AA, Chan TF. The prevalence of polypharmacy in elderly attenders to an emergency department - a problem with a need for an effective solution. Int J Emerg Med. 2011. Jun 2;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health Outcomes Associated with Polypharmacy in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014. Dec;62(12):2261–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007. Dec;5(4):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi Y, Nishida Y, Asai S. Utilization of health care databases for pharmacoepidemiology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012. Feb 1;68(2):123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999–2012. JAMA. 2015. Nov 3;314(17):1818–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motter FR, Fritzen JS, Hilmer SN, Paniz ÉV, Paniz VMV. Potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly: a systematic review of validated explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018. Jun;74(6):679–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. Jan 29; 2019 Apr; 67(4):674–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies EA, O’Mahony MS. Adverse drug reactions in special populations – the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015. Oct;80(4):796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper JA, Ryan C, Smith SM, Wallace E, Bennett K, Cahir C, et al. The development of the PROMPT (PRescribing Optimally in Middle-aged People’s Treatments) criteria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014. Oct 30;14:484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillot J, Maumus-Robert S, Marceron A, Noize P, Pariente A, Bezin J. The Burden of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Chronic Polypharmacy. J Clin Med. 2020. Nov 20;9(11); 3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oktora MP, Alfian SD, Bos HJ, Schuiling-Veninga CCM, Taxis K, Hak E, et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in older and middle-aged people treated for diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021. Jul;87(7):2807–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Petrovic M, Somers A, Colin P, Boussery K. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling older people across Europe: a systematic literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015. Dec;71(12):1415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rentsch CT, Morford KL, Fiellin DA, Bryant KJ, Justice AC, Tate JP. Safety of Gabapentin Prescribed for Any Indication in a Large Clinical Cohort of 571,718 US Veterans with and without Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020. Sep;44(9):1807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Womack JA, Murphy TE, Bathulapalli H, Smith A, Bates J, Jarad S, et al. Serious Falls in Middle-Aged Veterans: Development and Validation of a Predictive Risk Model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. Dec;68(12):2847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Merle L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007. Aug 1;63(8):725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rentsch CT, Beckman JA, Tomlinson L, Gellad WF, Alcorn C, Kidwai-Khan F, et al. Early initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation for prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 mortality in patients admitted to hospital in the United States: cohort study. BMJ. 2021. Feb 11;372:n311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CH, Umegaki H, Watanabe Y, Kamitani H, Asai A, Kanda S, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications according to STOPP-J criteria and risks of hospitalization and mortality in elderly patients receiving home-based medical services. PLOS ONE. 2019. Feb 8;14(2):e0211947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khatter A, Moriarty F, Ashworth M, Durbaba S, Redmond P. Prevalence and predictors of potentially inappropriate prescribing in middle-aged adults: a repeated cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2021. Jul;71(708):e491–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Rodriguez JA, Rogero-Blanco E, Aza-Pascual-Salcedo M, Lopez-Verde F, Pico-Soler V, Leiva-Fernandez F, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions according to explicit and implicit criteria in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. MULTIPAP: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanco-Reina E, Valdellós J, Aguilar-Cano L, García-Merino MR, Ocaña-Riola R, Ariza-Zafra G, et al. 2015 Beers Criteria and STOPP v2 for detecting potentially inappropriate medication in community-dwelling older people: prevalence, profile, and risk factors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019. Oct;75(10):1459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Azayzih A, AlAmoori R, Altawalbeh SM. Potentially inappropriate medications prescribing according to Beers criteria among elderly outpatients in Jordan: a cross sectional study. Pharmacy Practice. 2019. Jun 5;17(2):1439–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alhawassi TM, Alatawi W, Alwhaibi M. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications use among older adults and risk factors using the 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria. BMC Geriatrics. 2019. May 29;19(1):154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé (ANSM). Utilisation des inhibiteurs de la pompe à protons (IPP), Étude observationnelle à partir des données du SNDS, France, 2015. 2018. Dec. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metaxas ES, Bain KT. Review of Proton Pump Inhibitor Overuse in the US Veteran Population. J Pharm Technol. 2015. Aug;31(4):167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nam YS, Han JS, Kim JY, Bae WK, Lee K. Prescription of potentially inappropriate medication in Korean older adults based on 2012 Beers Criteria: a cross-sectional population based study. BMC Geriatr. 2016. Jun 2;16:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bongue B, Laroche ML, Gutton S, Colvez A, Guéguen R, Moulin JJ, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescription in the elderly in France: a population-based study from the French National Insurance Healthcare system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011. Dec;67(12):1291–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grina D, Briedis V. The use of potentially inappropriate medications among the Lithuanian elderly according to Beers and EU(7)-PIM list - a nationwide cross-sectional study on reimbursement claims data. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017. Apr;42(2):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leikola S, Dimitrow M, Lyles A, Pitkälä K, Airaksinen M. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use Among Finnish Non-Institutionalized People Aged ≥65 Years: A Register-Based, Cross-Sectional, National Study. Drugs & Aging. 2011. Mar;28(3):227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goltz L, Kullak-Ublick GA, Kirch W. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly outpatients in Germany: a retrospective claims data analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012. Mar;50(3):185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnett K, McCowan C, Evans JMM, Gillespie ND, Davey PG, Fahey T. Prevalence and outcomes of use of potentially inappropriate medicines in older people: cohort study stratified by residence in nursing home or in the community. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011. Mar;20(3):275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benard A, illioti de Gage S, Canarelli T, Cavalié P, Chatila K, Collin C, et al. État des lieux de la consommation des benzodiazépines en France. 2017. Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panes A, Pariente A, Bénard-Laribière A, Lassalle R, Dureau-Pournin C, Lorrain S, et al. Use of benzodiazepines and z-drugs not compliant with guidelines and associated factors: a population-based study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020. Feb 1;270(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bénard-Laribière A, Noize P, Pambrun E, Bazin F, Verdoux H, Tournier M, et al. Trends in incident use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in France from 2006 to 2012: a population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(2):162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bénard-Laribière A, Noize P, Pambrun E, Bazin F, Verdoux H, Tournier M, et al. Comorbidities and concurrent medications increasing the risk of adverse drug reactions: prevalence in French benzodiazepine users. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016. Jul 1;72(7):869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jirón M, Pate V, Hanson LC, Lund JL, Funk MJ, Stürmer T. Trends in Prevalence and Determinants of Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in the US 2007 – 2012. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016. Apr;64(4):788–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, Ehrenstein V, Nicholls SG, Filion KB, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ [Internet]. 2018. Nov 14 [cited 2020 Nov 13];363. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Drugs identified as potentially inappropriate medications defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria according to the VA generic name and specific requirement of the definition.

Table S2 Drugs identified as potentially inappropriate medications defined by PROMPT criteria according to the VA generic name and specific requirement of the definition.

Table S3 Codes from the International classification of disease 9th edition (ICD 9th) used to identify most frequent chronic diseases and clinical requirements.

Table S4 Characteristics of included patient aged 49 – 70 according to race/ethnicity

Table S5 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S6 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by combined Beers and Laroche criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to race and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S7 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to age, sex and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S8 Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) defined by PROMPT criteria in patients aged 49–70 years according to race and polypharmacy in 2016

Table S10 Prevalences of PIMs defined by Beers, Laroche and PROMPT criteria according to polypharmacy in previous international studies