Abstract

Three insertion sequences (IS) elements were isolated from the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Southern hybridization using these IS elements as probes revealed hybridization profiles that varied greatly between different strains of the pathogen. During a spontaneous phenotype conversion event, the promoter of the phcA gene was interrupted by one of these IS elements.

Ralstonia solanacearum is the causative agent of bacterial wilt disease in taxonomically diverse plant hosts, and the biological heterogeneity of the species is reflected in its genetic (4, 6), genomic, and biochemical complexities (12, 13, 16). Genomic variation in many bacterial species is generated by mobile DNA, which is common among bacterial genomes (14). Insertion sequence (IS) elements are the simplest transposable DNA in bacteria and have been major causes of genomic changes, such as insertion, deletion, and inversion (9). In pathogenic bacteria, IS elements modify the expression and cause the transposition of genes controlling interactions of the pathogen with the host organism (8, 10, 15), suggesting an important role for DNA transposition and rearrangement in the evolution of host-pathogen interactions.

During a screening for repetitious DNA that was unique to biovar 2 strain ACH0158 of R. solanacearum (Table 1), we isolated and characterized three novel IS elements, designated ISRso4, ISRso3, and ISRso2. Phenotype conversion (PC) (2) was also investigated for potential association with the movement of an IS element. PC is a phenomenon in which wild-type strains of R. solanacearum spontaneously lose their ability to produce large amounts of extracellular polysaccharide and a range of secreted proteins and become more motile, resulting in mutant strains with greatly reduced virulence (2). In several cases, PC has been reported to result from mutations in phcA (1, 2), a global regulatory gene controlling the transcription of genes associated with the virulence of the pathogen (18). In this study, ACH0158-M81C (Table 1) was identified as a PC mutant resulting from the insertion of ISRso4 within phcA (1, 2).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| R. solanacearum strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ACH0158 | Wild-type strain isolated from potato | A. C. Hayward |

| ACH0158-M81C | Spontaneous PC mutant of ACH0158 | This study |

| ACH0158-M3 | Spontaneous PC mutant of ACH0158 | This study |

| ACH0158-M8 | Spontaneous PC mutant of ACH0158 | This study |

| ACH1061 | Wild-type strain isolated from potato | A. C. Hayward |

| ACH1068S | Wild-type strain isolated from potato | A. C. Hayward |

| CIP418 | Wild-type strain isolated from peanut | CIP |

| CIP419 | Wild-type strain isolated from peanut | CIP |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKS(+), pKS(−), pSK(+), pSK(−) | Bluescript vectors; Apr | Stratagene |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector; Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pGEM-T Easy | Cloning vector; Apr | Promega |

| pISBE | 5.2-kb EcoRI fragment containing ISRso2 from wild-type ACH0158 cloned into pKS; Apr | This study |

| pSV102 | 2.7-kb EcoRI fragment containing ISRso4 and ISRso3 from wild-type ACH0158 cloned pKS; Apr | This study |

| pWT | 1.46-kb EcoRI fragment containing phcA from wild-type ACH0158 cloned into pGEM-T Easy; Apr | This study |

| pM81C | 1.64-kb EcoRI fragment containing phcA81C from PC mutant ACH0158-M81C cloned into pGEM-T Easy; Apr | This study |

| pM3 | 1.33-kb EcoRI fragment containing phcA3 from PC mutant ACH0158-M3 cloned into pGEM-T Easy; Apr | This study |

| pM8 | 1.46-kb EcoRI fragment containing phcA8 from PC mutant ACH0158-M8 cloned into pGEM-T Easy; Apr | This study |

Apr, resistance to ampicillin.

CIP, International Potato Centre, Lima, Peru.

Isolation of IS elements.

Plasmid clones of Sau3AI- and SalI-digested genomic DNA of the wild-type R. solanacearum biovar 2 strain ACH0158 were prepared with pBluescript or pUC19 (Table 1), and duplicate DNA blots from colonies were hybridized with [α-32P]dATP-labeled total genomic DNA from ACH0158 and ACH0171 (a taxonomically distant biovar 3 strain). Colonies showing strong hybridization to the ACH0158 probe and little or no hybridization to the ACH0171 probe were selected for further characterization. Several such clones were sequenced, and those that showed similarity to known IS elements were used as probes for a plasmid library of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from ACH0158 to yield clones containing full-length IS elements. A 2.7-kb EcoRI fragment (pSV102; Table 1) was sequenced and found to contain two adjacent IS elements, designated ISRso4 and ISRso3. Similarly, sequencing of a 5.2-kb EcoRI fragment (pISBE; Table 1) revealed a third IS element, designated ISRso2.

Characterization of IS elements.

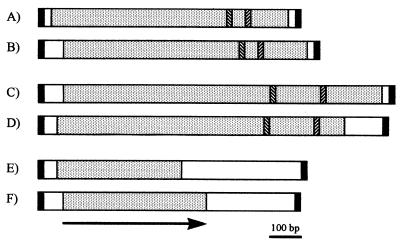

ISRso4 was readily identified because of its similarity to known IS elements, such as IS1031 (7). It is 855 bp long and has perfectly matched 17-bp inverted repeats (IRs) flanked by 4-bp CTAG direct repeats (DRs). The deduced amino acid sequence for a putative transposase within ISRso4 showed similarity to those of several IS elements belonging to the IS5 family from various bacterial species (17), including IS1031 from Acetobacter xylinum (35.2% identical, 57.2% similar). Amino acid sequences for the putative transposase of ISRso4 and those of the homologous IS elements had two conserved domains (17), N3 with D+I(G/A)(Y/F) and C1 with R+3E as invariant motifs that are typical features of the IS5 family.

The second element, ISRso3, is 1,209 bp long and has imperfect 18-bp IRs with 4 nucleotide mismatches and 4-bp CTAG DRs. The 3′ DR of ISRso3 is shared with the 5′ DR of ISRso4. For ISRso3, the amino acid sequence of the predicted transposase showed about 50% identity and 70% similarity to those of IS elements from distantly related Pseudomonas species and Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. This second group also shared the typical features of the IS5 family, but the core sequences of two domains were further apart than in ISRso4 (compare Fig. 1A and 1C). Therefore, ISRso3 is also a member of the IS5 family but has significant differences from ISRso4 in sequence and size.

FIG. 1.

Structural organization of ISRso4, ISRso3, and ISRso2 compared with that of known IS elements. (A) ISRso4. (B) IS1031 from A. xylinum (GenPept accession number AAA25029) (7). (C) ISRso3. (D) IS1384 from P. putida plasmid pPGH1 (GenPept accession number AAC98743). (E) ISRso2. (F) IS1301 from N. meningitidis (GenPept accession number CAA88914). Only one of the two ORFs in IS1301 was significantly similar to the ISRso2 sequence (11). Symbols: ■, IRs of each IS element; ░⃞, ORFs of each IS element; ▧, locations of the signatures for N3 [D+I(G/A)(Y/F)]; ▨, C1 (R+3E) motif. The arrow indicates the direction of transcription.

ISRso2 is 864 bp long and has 15-bp IRs with a base-pair mismatch. Its putative open reading frame (ORF) (encoding 134 amino acids) showed sequence similarity to several IS elements from diverse bacteria, including Neisseria meningitidis (with only one of the two ORFs of IS1301 showing 28% identity and 49% similarity) (11). This group of IS elements has conserved amino acid sequences but as yet has not been classified into a particular family. Some bacterial species in which elements similar to ISRso2 have been found are taxonomically distant from R. solanacearum, such as N. meningitidis, a human pathogen causing meningococcal meningitis.

Each of the three IS elements from R. solanacearum showed conserved domains and strong sequence similarities, both nucleotide and derived amino acid, to different families of IS elements from a diverse range of bacteria.

Distribution of IS elements.

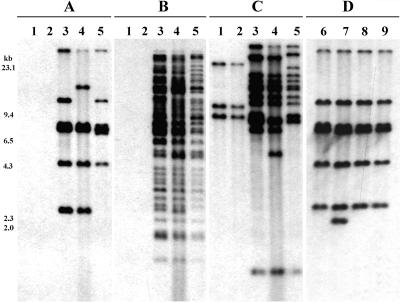

To ascertain the copy numbers and sequence distribution of the IS elements within the R. solanacearum genome and to look for differences between genetically different isolates, the three IS elements were used individually as probes in Southern analyses. ISRso4 hybridized to six EcoRI fragments in three biovar 2 strains (Fig. 2A) and was concluded to be present in at least six copies because of the lack of internal EcoRI sites in its sequence. In these biovar 2 strains, ISRso3 hybridized to numerous (>40) EcoRI fragments (Fig. 2B) and ISRso2 hybridized to approximately 12 fragments (Fig. 2C). For ISRso3 and ISRso2, these copy numbers may be underestimated because of the possibility of multiple copies of the elements in the more strongly hybridizing fragments. The differences in hybridization intensity may reflect the presence of truncated fragments or relics that have diverged sufficiently in sequence to reduce the level of hybridization at high stringency. As we have sequenced only single examples of ISRso3 and ISRso2, we cannot distinguish between these possibilities.

FIG. 2.

Southern hybridization of genomic DNA from five strains of R. solanacearum and three PC mutants derived from wild-type ACH0158. Lane 1, CIP418 (biovar 1); lane 2, CIP419 (biovar 1); lanes 3 and 6, ACH0158 (biovar 2); lane 4, ACH1061 (biovar 2); lane 5, ACH1068S (biovar 2); lane 7, ACH0158-M81C; lane 8, ACH0158-M3; lane 9, ACH0158-M8. Southern membranes were hybridized with ISRso4 (A and D), ISRso3 (B), and ISRso2 (C) probes. Molecular sizes are shown on the left. The figure was produced by use of Adobe Photoshop 5.0.

Southern hybridization of DNA from three biovar 2 strains revealed similar hybridization patterns for a particular probe. Fourteen additional biovar 2 race 3 strains were also tested (results not shown), and hybridization profiles very similar to those shown in Fig. 2 were obtained. The overall similarity of the Southern hybridization patterns in biovar 2 strains is consistent with genetic uniformity in biovar 2 strains. Based on restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of several isolates of the species, Cook and others (4, 6) suggested that biovar 2 (race 3) strains have almost identical genomes, commensurate with the uniformity of their metabolic and other biological characteristics regardless of their geographical origins. Taken together, these results support the suggestion that all biovar 2 strains have a clonal origin in South America (6). Cook and Sequeira (5, 6), however, also observed that a race 3-specific 2-kb DNA fragment isolated by subtractive hybridization was present in a minority (less than 6%) of non-race 3 strains and suggested the possibility of lateral gene transfer between distantly related strains within the species. Our results support this suggestion as we observed ISRso2-like sequences in two biovar 1 (non-race 3) strains (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 2), although a small number of strains was tested.

ISRso4 disrupts the phcA gene in a PC mutant.

To investigate the possibility of active transposition of these IS elements, the behavior of ISRso4 during PC was examined (2). Three spontaneous PC mutants were isolated from wild-type ACH0158, and their EcoRI-digested genomic DNA was probed with ISRso4 in Southern analyses. The hybridization pattern of ACH0158-M81C showed an additional 2.1-kb band (Fig. 2D, lane 7) compared with the patterns of the wild type (Fig. 2D, lane 6) and the other two PC mutants (Fig. 2D, lanes 8 and 9).

The regions flanking the new insertion in ACH0158-M81C were obtained by inverse PCR and cloned as pM81C (Table 1). Sequence comparisons of this clone and DNA databases revealed greater than 99% amino acid sequence identity to the product of the phcA gene of R. solanacearum strain AW1 (2). The phcA gene has been characterized as a global regulator of virulence genes and as being central to the mechanism of PC (1, 3). Brumbley et al. (1) characterized the PhcA protein as a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators that control the expression of genes encoding virulence factors (3, 18). Brumbley and Denny (2) observed hybridization of the sequences flanking phcA to repetitious DNA in the genomes of AW1 and related strains.

The new copy of ISRso4, integrated between nucleotide positions 120 and 121 within the phcA gene of ACH0158-M81C, created 5-bp (CTGAG) DRs (results not shown), and the sequence differed from the CTAG DRs in pSV102 and the CTAG DRs in a third, independently isolated copy of ISRso4 (results not shown). Variations in target duplication length and sequence at the point of insertion are not unusual (9) and may be influenced by different helix conformations of the nucleotide sequence of the phcA gene during the initial cleavage by ISRso4. However, additional variations in the length and sequence of the DR motif between different genomic copies of ISRso4 cannot be ruled out, as we have characterized only three of seven possible insertion sites. These results suggest that IS elements contribute to genomic variation and heterogeneity among strains and also to significant phenotypic changes related to virulence in R. solanacearum.

The phcA genes were also cloned from wild-type ACH0158 and two additional PC mutants (ACH0158-M3 and ACH0158-M8) in clones pWT, pM3, and pM8, respectively (Table 1). The two PC mutants showed sequence lesions within phcA, confirming the importance of this gene in PC. However, ISRso4 was not involved, and neither were ISRso3 and ISRso2. ACH0158-M3 (Table 1) had between nucleotides 23 and 155 a 132-bp deletion that removed the start codon of phcA (results not shown). ACH0158-M8 (Table 1) contained at nucleotide position 648 in the ORF of phcA a 2-bp (TG) insertion causing a frameshift that resulted in an early stop codon and a truncated protein similar to that previously described for the phcA1 allele from a spontaneous PC mutant, AW1-PC (1). Therefore, the movement of ISRso4 contributes to a range of different mutations that cause PC. However, the transposition of DNA into phcA is not a common cause of PC. Southern analysis indicated that genomic DNA of only 1 in 10 PC mutants probed with phcA showed a band shift consistent with IS element insertion (results not shown). The mutation in ACH0158-M3 is clearly irreversible, whereas the reversibility of PC may be important in vivo. The latter is possible in ACH0158-M81C by perfect IS element excision. However, so far we have been unable to demonstrate the restoration of wild-type ACH0158 from either ACH0158-M81C or ACH0158-M8. It is possible that many insertions are merely “dead ends”—giving rise to cells which not only are incapable of infection but also have lost the capacity to regain these functions.

Concluding remarks.

Southern hybridization and sequence analyses suggested that the IS elements isolated in R. solanacearum may have been horizontally transferred because of the presence of highly homologous IS elements in very distantly related bacterial taxa and the lack of a clear lineage for the IS elements within diverse strains of R. solanacearum.

Only a single member of each element was fully characterized by sequencing, and evidence for the presence of other genomic copies was obtained from Southern hybridization. We describe one event where the transposition of ISRso4 to a new genomic location causes a specific gene mutation and a consequent change in phenotype. It remains to be fully explored whether these IS elements are all actively involved in genomic rearrangements that contribute to the extensive genetic heterogeneity among different isolates of this species. The availability of mechanisms, in the form of multiple IS elements, that enable fast and extensive genome changes may be essential in R. solanacearum and in other bacterial species that constantly modify the expression of genes responsible for host-pathogen interactions (8), pathogenicity (10), and metabolic pathways (15), either by mutation or regulation.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of ISRso4, ISRso3, and ISRso2 have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF079849, AF183890, and AF186082, respectively. The GenBank accession number for the phcA gene from R. solanacearum strain ACH0158 is AF184046.

Acknowledgments

We thank The University of Adelaide for an international postgraduate research scholarship to E.-L. Jeong. This study was supported in part by grant PN9452 from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

We thank Tim Denny, Viji Krishnapillai, Chris Hayward, and Mark Fegan for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brumbley S M, Carney B F, Denny T P. Phenotype conversion in Pseudomonas solanacearumdue to spontaneous inactivation of PhcA, a putative LysR transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5477–5487. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5477-5487.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brumbley S M, Denny T P. Cloning of wild-type Pseudomonas solanacearum phcA, a gene that when mutated alters expression of multiple traits that contribute to virulence. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5677–5685. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5677-5685.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clough S J, Schell M A, Denny T P. Evidence for involvement of a volatile extracellular factor in Pseudomonas solanacearumvirulence gene expression. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1994;7:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook D, Barlow E, Sequeira L. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas solanacearum: detection of restriction fragment length polymorphisms with DNA probes that specify virulence and the hypersensitive response. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1989;2:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook D, Sequeira L. The use of subtractive hybridization to obtain a DNA probe specific for Pseudomonas solanacearumrace 3. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:401–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00273930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook D, Sequeira L. Strain differentiation of Pseudomonas solanacearum by molecular genetic methods. In: Hayward A C, Hartman G L, editors. Bacterial wilt: the disease and its causative agent, Pseudomonas solanacearum. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coucheron D H. A family of IS1031 elements in the genome of Acetobacter xylinum: nucleotide sequences and strain distribution. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galán J E, Collmer A. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999;284:1322–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galas D J, Chandler M. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Berg D, Howe M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 109–162. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Mühldorfer I, Tschäpe H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammerschmidt S, Hilse R, van Putten J P, Gerardy-Schahn R, Unkmeir A, Frosch M. Modulation of cell surface sialic acid expression in Neisseria meningitidisvia a transposable genetic element. EMBO J. 1996;15:192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayward A C. Characteristics of Pseudomonas solanacearum. J Appl Bacteriol. 1964;27:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward A C. The hosts of Pseudomonas solanacearum. In: Hayward A C, Hartman G L, editors. Bacterial wilt: the disease and its causative agent, Pseudomonas solanacearum. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healy F G, Bukhalid R A, Loria R. Characterization of an insertion sequence element associated with genetically diverse plant pathogenic Streptomycesspp. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1562–1568. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1562-1568.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallastu A, Hõrak R, Kivisaar M. Identification and characterization of IS1411, a new insertion sequence which causes transcriptional activation of the phenol degradation genes in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5306–5312. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5306-5312.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opina N, Tavner F, Hollway G, Wang J-F, Li T-H, Maghirang R, Fegan M, Hayward A C, Krishnapillai V, Hong W F, Holloway B W, Timmis J N. A novel method for development of species- and strain-specific DNA probes and PCR primers for identifying Burkholderia solanacearum (formerly Pseudomonas solanacearum) Asia Pacific J Mol Biol Biotechnol. 1997;5:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rezsöhazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J, Mahillon J. The IS4family of insertion sequences: evidence for a conserved transposase motif. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schell M A. To be or not to be: how Pseudomonas solanacearumdecides whether or not to express virulence genes. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1996;102:459–469. [Google Scholar]