Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cobalt tungstate, Sonocatalysis, Tetracycline, Wastewater treatment

Highlights

-

•

Ag3PO4/CoWO4 nanocomposite was prepared by a facile precipitation method.

-

•

Nanocomposite had been characterized by various techniques.

-

•

Sonocatalytic activity of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 were studied through TC degradation.

-

•

The sonocatalytic degradation mechanism of TC by Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was proposed.

-

•

Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composite showed good stability and reusability in four reuses.

Abstract

In this study, 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites were synthesized by hydrothermal method. The prepared materials were systematically characterized by techniques of scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), X-ray diffractometer (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), N2 adsorption/desorption, and UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectrum (DRS). Furthermore, the sonocatalytic degradation performance of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites towards tetracycline (TC) was investigated under ultrasonic radiation. The results showed that, combined with potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites achieved a high sonocatalytic degradation efficiency of 97.89 % within 10 min, which was much better than bare Ag3PO4 or CoWO4. By measuring the electrochemical properties, it was proposed that the degradation mechanism of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 is the formation of S-scheme heterojunction, which increases the separation efficiency of electron-hole pairs (e--h+) and generates more electrons and holes, thereby enhancing the degradation activity. The scavenger experiments confirmed that hole (h+) was the primary active substance in degrading TC, and free radicals (•OH) and superoxide anion radical (•O2–) were auxiliary active substances. The results indicated that 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 nanocomposites could be used as an efficient and reliable sonocatalyst for wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

As one of the significant discoveries of the last century, antibiotics have considerably changed the treatment of a series of infectious diseases. It has been widely used in bacterial infections [1] of humans and animals as well as in agricultural and aquacultural areas [2]. However, only a tiny part of antibiotics can be metabolized or absorbed in humans or animals during the process of application. Most antibiotics (about 40–90 %) are discharged into the water environment or soil in the form of original drugs or primary metabolites [3]. With the deposition of antibiotics in different areas of the environment (including surface water, groundwater, drinking water, municipal sewage, soil, plants and sludge) [4], which leads to the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARBs) and antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs), with severe impacts on agriculture, aquaculture, humans and livestock [5]. TC is the second most produced and used antibiotic due to its broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and low production cost [6], [7]. It is not easily to be destroyed [8], [9] and enriched over time in various aquatic environments for its benzene skeleton structure and high hydrophilicity. Since TC is biologically toxic and carcinogenic [10], [11], it is potentially harmful to human health [12], aquatic ecosystems, and microbial populations [13] if it is accumulated in large quantities in the environment for a long time.

Traditional sewage treatment plants and biological treatment technologies are not sufficient to remove antibiotics from wastewater [14], so an advanced technology with simple operation, high efficiency, good effect, low price, and eco-friendliness is sought to alleviate the problem of environmental pollution. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) degrade pollutants by generating free radicals with strong oxidizing ability [15], which have the advantages of simple operation [16], fast degradation rate, good degradation effect [17], low toxicity of degradation products [18], and non-selectivity in the oxidation of contaminants [19]. As a kind of AOPs, sonocatalytic is a chemical effect of ultrasonic waves caused by acoustic cavitation [15], which refers to the propagation of ultrasonic waves in a liquid that could change local pressures over time and space and lead to the formation of bubbles. The radii of the bubbles expand, contract and/or collapse as these pressures change [20]. The collapse of transient bubble leads to the appearance of sonoluminescence (SL) and “hot spots”, which can generate high temperature and high pressure, exceeding 5000 K and 1000 atm, respectively [21], [22]. Under such extreme conditions, water thermally decomposes to form free radicals, such as •OH, •H, •O2–, which are highly reactive and non-selective, attack organic molecules to produce CO2, H2O, and inorganic ions, or less toxic intermediates [23], [24]. Since ultrasonic degradation combines sonic decomposition and photocatalysis, it is easier to increase the degradation of organic matter than AOPs alone [25], and has the advantages of strong penetrating ability, simple operation, and no secondary pollution [26], [27]. However, the degradation of pollutants by a simple sonocatalytic process usually requires long reaction times, limited degradation efficiency, and high energy consumption [25], [28]. So, some scientists have combined ultrasound with other AOPs technologies to further improve the performance of catalysts for the removal of pollutants. Aydin Hassani et al. found that the combination of ultrasound and electrochemical processes have synergistic effects that lead to enhanced mineralization of organic pollutants [29], such as the combination of Electro-Peroxone (EP) and ultrasound effectively enhanced acid orange 7 degradation [30]. At the same time, studies have shown that solid catalysts in ultrasonic systems could provide more nucleation sites for bubble cavitation and more charge carriers for the formation of free radicals, thereby enhancing the ultrasonic degradation effect [31], [32]. For example, some nanoparticles act as sonocatalysts, which can reduce the energy and time required for the degradation of organic pollutants [33]. According to recent studies, many semiconductor materials, such as TiO2 [34], CdS [35], ZnO [31], N-TiO2/Ti3C2 [36], CoFe2O4-rGO [37], Fe3O4/SnO2/NGP [38] etc., have been used as sonocatalysts.

The nano-semiconductor material cobalt tungstate (CoWO4) has excellent catalytic and electrochemical properties [39], [40]. At the same time, it has the advantages of a simple preparation method [41], high chemical stability [42], and environmental friendliness [43]. It is used in the fields of photovoltaic electrochemical cell luminescent materials [44], supercapacitors [41], conventional oxidation catalysts, and environmental purification photocatalysts [45], [46]. Although CoWO4 has a good application in catalysis, it has a low utilization rate of sunlight, slow degradation efficiency, and low separation efficiency of e--h+, which may limit its catalytic degradation ability. These disadvantages can be ameliorated by modifying it [47]. For example, the CoWO4/g-C3N4 heterostructure prepared by Prabavathi et al. has better photocatalytic activity [48]; Cui et al. [49] constructed a Z-scheme-based CoWO4/CdS, which greatly enhanced the activity for hydrogen production and dye degradation. Recently, silver-based photocatalysts, such as Ag3PO4, Ag2WO4 [50], Ag2CO3 [51], AgX (X = Cl, Br, I) and Ag2MoO4 [52] have received extensive attention in the field of photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Among them, Ag3PO4 has a strong oxidizing ability under visible light excitation and nearly 90 % quantum utilization efficiency [53], [54], which is considered as a promising visible-light-driven photocatalyst. However, the stability of the Ag3PO4 photocatalytic system has always been a significant problem. First, the slight solubility of Ag3PO4 in aqueous solution will reduce its stability under working conditions [55]; second, during the degradation of Ag3PO4, Ag+ in the lattice is reduced to metallic Ag by photogenerated electrons [56], which leads to the structural destruction of Ag3PO4, which affects the absorption of visible light by Ag3PO4 and reduces its photocatalytic activity [55]. This problem can be addressed by techniques such as structure and morphology control, metal doping, composites carbon-based materials [57], and coupling with other semiconductors [58]. Therefore, this study, for the first time, considered the application of Ag3PO4 to the sonocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical wastewater. Compositing it with CoWO4 to form a heterojunction and accelerate electron migration, thereby reducing the recombination rate of photogenerated e--h+ [59] and the probability of electron reduction of Ag+ [54], making the composites exhibit more excellent sonocatalytic activity and stability.

In this paper, Ag3PO4 was used for the first time in the application of sonocatalysis, and the Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites sonocatalyst was produced by combining with CoWO4 by hydrothermal method. The prepared composites sonocatalyst was characterized, and the physical and chemical properties of the modified catalysts were analyzed. The sonocatalytic performance of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was studied by degrading TC, and the influence of different factors on the degradation performance during the degradation process was investigated. In addition, added K2S2O8 to improve the catalytic activity further. At the same time, the reuse experiment was carried out to investigate the stability and reusability of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4. Furthermore, the sonocatalytic mechanism of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was discussed by radical trapping experiments and the Mott-Schottky equation. At present, there’s no report about Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites, and this is the first time that Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites have been synthesized and used in the field of sonocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants.

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co (NO3)2·6H2O) was analytical reagent (AR) and purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory. Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4·2H2O, AR) was purchased from Tianjin No.4 Chemical Reagent Factory. Sodium phosphate (Na3PO4·12H2O, AR) was purchased from Tianjin Yongda Chemical Reagent Co., ltd. Silver nitrate (AgNO3, 98 %) was purchased from Tianjin Fengchuan Chemical Reagent Technology Co., ltd. Mannitol (d-Man, AR) was purchased from Tianjin Bodi Chemical Co., ltd. K2S2O8 (AR) was purchased from Tianjin Hengxing Chemical Reagent Manufacturing Co., ltd. Ammonium oxalate monohydrate (AO, AR) and TC (96 %) was purchased from Maya Reagent Co., ltd. Deionized water was used in the experiments.

2.2. Preparation of Ag3PO4 and Ag3PO4/CoWO4

CoWO4 was prepared by a simple hydrothermal method [60]. The preparation method of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites material was as follows: 0.6156 g of CoWO4 was ultrasonically dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water, and 0.6115 g of AgNO3 was weighed and dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water. Then 0.45614 g of 20 ml Na3PO4·12H2O deionized aqueous solution was added dropwise to the mixed solution, and the magnetic stirring was continued for 1 h. The obtained precipitate was vacuum filtered, washed several times with deionized water, dried at 60 °C for 15 h and then ground. Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites material was obtained finally. Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites with different molar ratios (0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2) were obtained by adjusting the addition amounts of AgNO3 and Na3PO4·12H2O. Pure Ag3PO4 was prepared by using a similar process without the addition of CoWO4.

2.3. Characterization of Ag3PO4/CoWO4

The morphology of the samples was observed by TESCAN MIRA4 SEM. The elemental composition and content of the samples were determined by Thermo Scientific K-alpha XPS at 12 kV monochromatic Al Kα radiation. The crystal structures of the samples was determined by using a MiniFlex 600 XRD under Cu Kα radiation with a 2θ scan rate of 10°/min and a scan range from 10° to 80°. The UV absorption spectrum and UV DRS were measured by using a Shimadzu UV-3600 UV–vis-NIR spectrophotometer with BaSO4 as a reference and a wavelength range of 200–800 nm. The Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) and pore distribution of the samples were determined by using a Mack TriStar II 3020 N2 adsorption/desorption analyzer at 60 °C.

2.4. Sonocatalytic degradation experiment of TC

In the ultrasonic degradation experiment, the initial conditions were set follows: 20 mg Ag3PO4/CoWO4 powder was added to 20 ml of TC solution, the TC concentration was 45 mg/L, the ultrasonic power was 500 W, and the ultrasonic time was 2 h. Interrelated factors were adjusted in a single factor test. Added Ag3PO4/CoWO4 powder to the TC solution before sonication, then stirred magnetically for 30 min in the darkness to ensure that the adsorption/desorption equilibrium was reached. Afterwards, according to the above conditions, samples were irradiated by using an ultrasonic bath (KQ5200, 40 kHz, 500 W, Kunshan Ultrasonic Instrument Co., ltd., China) at 313 K, during which light was avoided. After ultrasonication, the solution was filtered with a 0.22 μm microporous membrane, and the absorbance at 354.5 nm of the obtained solution was measured with a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The degradation rate was calculated according to the Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where is the initial absorbance of TC, and is the absorbance of TC when the ultrasonic time is t.

To examine the cycling stability of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4, the samples used in the sonocatalysis reaction were recovered and used repeatedly for four cycles. To detect the active species in the sonocatalysis process, d-Man [61], AO [62], and N2 [63] were used as •OH, h+, •O2– scavengers for active substance studies.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of nanocomposites

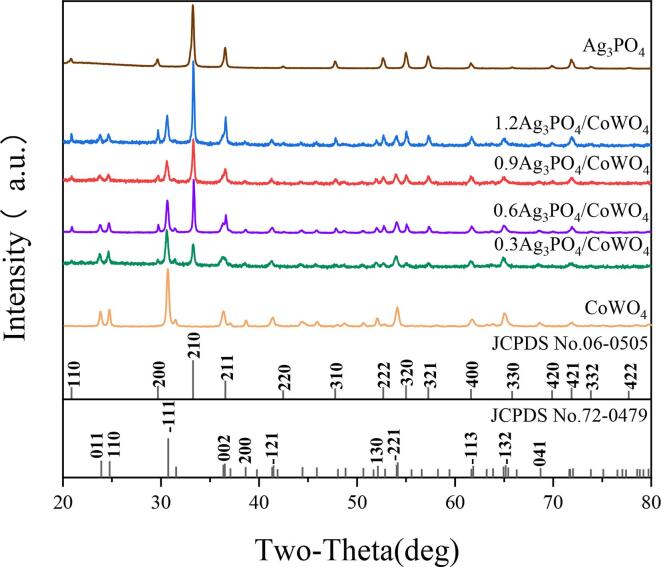

The crystal structure and phase purity of the as-prepared composites were determined by using XRD patterns. Fig. 1 showed the standard patterns of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and the XRD patterns of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 with different molar ratios, respectively. According to Fig. 1, the peak of 2θ values was 20.8°, 29.7°, 33.3°, 36.6°, 42.5°, 47.8°, 52.7°, 55.1°, 57.3°, 61.7°, 65.9°, 70.0°, 71.9°, 73.9° and 77.7°, corresponded to the (1 1 0), (2 0 0), (2 1 0), (2 1 1), (2 2 0), (3 1 0), (2 2 2), (3 2 0), (3 2 1), (4 0 0), (3 3 0), (4 2 0), (4 2 1), (3 3 2) and (4 2 2) plane of Ag3PO4(JCPDS No. 06–0505) [56]. The diffraction peaks of 2θ characteristic peaks at 23.8°, 24.6°, 30.6°, 36.3°, 38.5°, 41.4°, 52.0°, 54.0°, 61.8°, 65.1°, 68.6° were similar to (0 1 1), (1 1 0), ( −1 1 1), (0 0 2), (2 0 0), ( −1 2 1), (1 3 0), ( −2 2 1), ( −1 1 3), ( −1 3 2) and (0 4 1) plane of CoWO4 (JCPDS-72–0479) [64]. For the spectrum of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites in Fig. 1, all the diffraction peaks could be marked as characteristic peaks of Ag3PO4 or CoWO4. The intensity of the (2 0 0), (2 1 0), (2 1 1), (3 1 0), (2 2 2), (3 2 0), (3 2 1), (4 0 0), (4 2 1) peak increased significantly with the increasing of Ag3PO4 composites ratio, indicating that the successful assembly of these two materials did not cause obvious change or destruction of the crystal structure. And it could be seen that the shape of the diffraction peaks was very sharp and the intensity is high, indicating that the synthesized Ag3PO4/CoWO4 had a high crystallinity.

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of standard spectra of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and Ag3PO4/CoWO4 with different molar ratios.

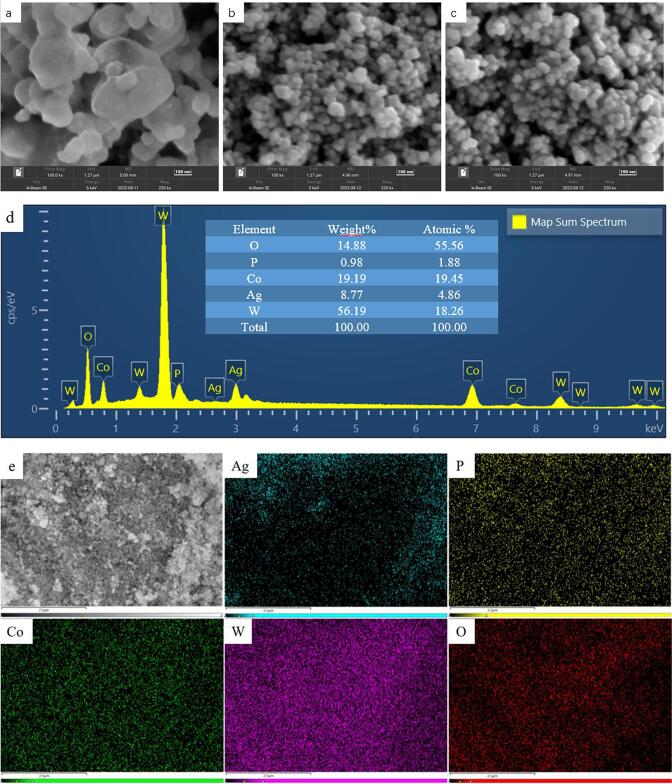

The surface morphologies of the prepared bare CoWO4, Ag3PO4, and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 were investigated by SEM. As shown in Fig. 2a that CoWO4 is a spherical nanoparticle with large particle size, about 100–200 nm, and the agglomeration phenomenon is obvious. Fig. 2b is the SEM image of Ag3PO4, and its nanoparticles are also spherical, with a particle size slightly smaller than that of CoWO4, about 50–80 nm, with slight agglomeration. Fig. 2c is the SEM of the composite material. It could be seen that Ag3PO4 particles are uniformly wrapped on the surface of CoWO4, forming a spherical shape. Compared with the pure material, the dispersion degree is slightly improved and the agglomeration phenomenon is reduced. The elemental purity of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was determined by the EDX system. As the EDX peaks shown in Fig. 2d 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 is composed of Ag, P, Co, W, and O elements. In addition, no impurity peaks appear, indicated that the obtained 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 is of high purity, and the relative element/weight ratio was shown in the table (inset Fig. 2d). Fig. 2e showed the specified SEM images of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 nanocomposites and corresponding elemental mapping. It was further explained that the Ag, P, Co, W, and O elements in the composite are evenly distributed, indicated that Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 are thoroughly combined.

Fig. 2.

The SEM images of CoWO4 (a), Ag3PO4 (b) and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 (c) and EDX spectra of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 (d) and specified SEM images of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 nanocomposites and elemental mapping (e).

In order to shed more light on inner structure of the sample, TEM analysis was taken for 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4. As shown in Fig. 3a that Ag3PO4 particles were uniformly fixed on the surface of CoWO4 particles, and the particle size of CoWO4 was reduced to 20–50 nm, while that of Ag3PO4 was reduced to 2–5 nm. The HRTEM in Fig. 3b showed clear lattice fringe of the composites, with band spacing of 0.269 nm and 0.36 nm corresponded to plane (2 1 0) of Ag3PO4 [56] and plane (0 1 1) of CoWO4 [43], respectively.

Fig. 3.

The TEM images (a) and HRTEM images (b) of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4.

The chemical state and composition of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 were further affirmed by high-resolution XPS. Fig. 3a showed the XPS scanning spectra of CoWO4, Ag3PO4, and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites. It could be seen that the composites sonocatalysis contained Ag, P, Co, W, and O elements. The high-resolution XPS spectra of Ag 3d, P 2p, Co 2p, and W 4f were shown in Fig. 4b-e. Two prominent peaks of Ag 3d are observed at 367.48 eV and 373.48 eV in Fig. 4b, which were attributed to Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2 photon electrons, respectively, indicated that Ag exists in the form of Ag+. It could be seen from Fig. 4c that the P5+ ion in PO43− had a single peak [56] at 132.38 eV, and combined with Fig. 4a, we could infer the formation of Ag3PO4. Two prominent peaks of Co 2p were observed at 781.18 eV and 797.88 eV in Fig. 4d, which were attributed to Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 photons, respectively, indicated that Co exists in the form of Co2+. At the binding energies of 787.78 eV and 803.65 eV, two satellite peaks on the catalyst surface, corresponded to the adsorption of hydroxide and cobalt salt [65]. At 35.78 eV and 37.98 eV in Fig. 4e, two prominent peaks of W 4f were observed, ascribed to W 4f7/2 and W 4f5/2 photons, respectively, indicated that W in WO42- exists as + 6 ion [66]; and combined with Fig. 4a, we could infer the formation of CoWO4. Compared with the pure material, the binding energy of the composite had shifted, in which the binding energy of Ag and P elements were reduced, while the binding energy of Co and W elements were enhanced, indicated that there was a strong interaction between CoWO4 and Ag3PO4, which might be related to the formation of S-scheme heterojunctions. In conclusion, the XPS results indicated that 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was successfully synthesized.

Fig. 4.

XPS scanning spectra of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites and high-resolution XPS measurement spectrum of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 nanocomposites.

It is well known that specific surface area and pore size are crucial for catalytic activity [67]. Therefore, N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were used to study the specific surface area and pore size distribution of the samples. The results were shown in Table 1. The corresponding N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and the pore distribution were shown in Fig. 5. It was indicated that the prepared sonocatalyst has scheme IV isotherm. From the BET surface area analysis, it could be seen that the BET of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 were comparatively smaller, 35.78 and 18.20 m2/g, respectively, while the BET increases to 40.48 m2/g when the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites is formed. Used the Barrett-Joyner-Harenda (BJH) diagram to give the pore size of the composites, the average pore size of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was 0.10 cm3/g, which is larger than that of Ag3PO4 (0.06 cm3/g) and CoWO4 (0.08 cm3/g). It could be found that the addition of Ag3PO4 could increase the specific surface area and pore size. Due to the large specific surface area and abundant pore structure, the adsorption performance of the catalyst can be enhanced and more active catalytic sites can be provided [60]. Therefore, the large specific surface area and pore size of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 are beneficial for improving its sonocatalytic activity [35].

Table 1.

BET and BJH parameters of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites.

| Sample | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoWO4 | 35.78 | 0.08 | 9.22 |

| Ag3PO4 | 18.20 | 0.06 | 12.27 |

| 0.6CoWO4/ Ag3PO4 | 40.48 | 0.10 | 9.43 |

Fig. 5.

N2 adsorption/desorption curves (a) and pore distribution diagrams (b) of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites.

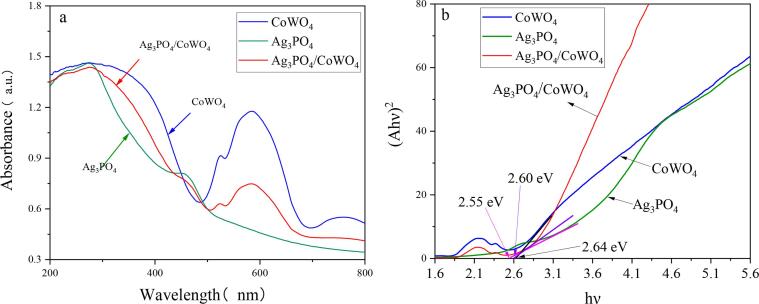

The light absorption capacity of the catalyst has a significant influence on its catalytic activity [64]. Therefore, to study the absorption of the sample in the UV–visible region, its UV–visible absorption spectrum was scanned, as shown in Fig. 6a. It could be seen that, Ag3PO4, CoWO4, and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 all have excellent UV–vis responses. Among them, the absorption limit of Ag3PO4 was 580 nm, and the peak shape was wider, indicated that Ag3PO4 has strong visible light absorption. There are two prominent absorption peaks in the absorption curve of CoWO4, which were located in the ultraviolet area of 225–375 nm and the visible area of 550–600 nm, and an inconspicuous peak was formed at about 525 nm. The peak shape in the ultraviolet area was broader, and the peak shape distribution in the visible area was narrower. It shows that CoWO4 has a high absorption and utilization efficiency for ultraviolet light, but relatively low utilization for visible light. Compared with pure CoWO4, the absorbance of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites decreased after adding Ag3PO4, but the absorbance appeared red-shifted in the visible region, indicated that 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 has better photoresponse [56]. The band gap energy (Eg) of each sample was calculated with the following Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where α represents the absorption coefficient, hν represents the photon energy, Eg represents the band gap, and A represents the proportionality constant [68]. The value of n depends on the transition scheme of the semiconductor (n = 1 when the transition is allowed directly, n = 4 when the transition is allowed indirectly [69]). Using the light absorption data and Tauc equation, the band gap values of pristine Ag3PO4, CoWO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 were 2.55 eV, 2.64 eV and 2.60 eV respectively (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

UV–vis-DRS spectra (a) and curves of (αhν)2 and hν (b) of CoWO4, Ag3PO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites.

3.2. Influence of operating parameters on sonocatalytic performance

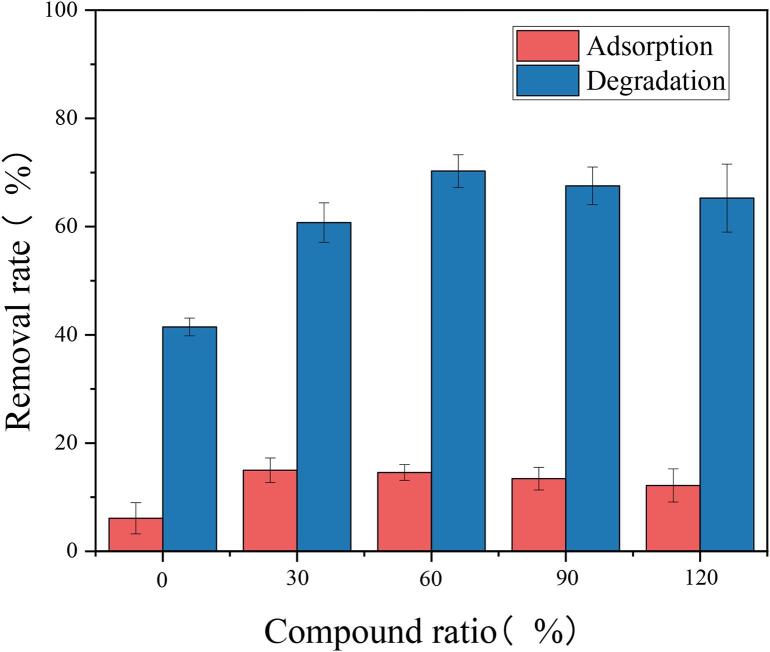

3.2.1. Influence of different Ag3PO4 compound ratios

By changing the addition amount of AgNO3 and Na3PO4·12H2O in the preparation process, the composites with compound ratios of 0.3,0.6,0.9, and 1.2 were synthesized, and TC was degraded under the same ultrasonic conditions. As shown in Fig. 7, with the increasing compound amount of Ag3PO4, the degradation of TC by the composites showed a trend of increasing firstly (from 0.3 to 0.6) and then decreasing (from 0.6 to 1.2). It showed that the molar ratio of Ag3PO4 in Ag3PO4/CoWO4 has a great contribution to the catalytic activity of the composites, because the photogenerated holes in the Ag3PO4 conduction band represent a robust oxidizing ability, when there was an excess of Ag3PO4 in the composites, not only the light absorption intensity of the composites being reduced, but also the photo corrosion of Ag3PO4 being enhanced, thereby reducing the sonocatalysis activity of the composites [54]. When the compound molar ratio of Ag3PO4 to CoWO4 was 0.6, the sonocatalytic degradation rate was the highest, so the subsequent degradation experiments used a composites material with a molar ratio of 0.6.

Fig. 7.

Effect of Ag3PO4 compound ratio on degradation rate. (Catalyst addition = 1 g/L, Initial concentration of TC = 45 mg/L, Ultrasonic power = 500 W, Ultrasonic time = 2 h).

3.2.2. Influence of the amount of catalyst added

By changing the addition amount of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 catalyst, the effect of the additional amount on the degradation rate was studied. The results were presented in Fig. 8(a). It could be seen that when the addition amount was changed from 0.5 to 2 g/L, the degradation rate increased (from 0.5 to 1 g/L) firstly and then remained almost unchanged. The degradation rate was the highest (71 %) when the dosage was 1 g/L. The reason for the improved degradation efficiency is that an appropriate amount of catalyst can provide sufficient surface area and active sites for sonocatalysis [70], while when the dose continues to increase, the solid particles will have a masking effect on the penetration ability of the ultrasonic wave, thereby reducing the surface reaction sites of •OH radical generation. Moreover, the ultrasound might be disseminated by the additional catalyst in the solution, which could inhibit heat and energy conduction near the surface of the catalyst [71].

Fig. 8.

Effect of catalyst addition amount (a) (Initial concentration of TC = 45 mg/L, Ultrasonic power = 500 W, Ultrasonic time = 2 h), initial tetracycline concentration (b) (Catalyst addition = 1 g/L, Ultrasonic power = 500 W, Ultrasonic time = 2 h), ultrasonic power (c) (Catalyst addition = 1 g/L, Initial concentration of TC = 15 mg/L, Ultrasonic time = 2 h) on degradation rate.

3.2.3. Effect of initial TC concentration

The effect of different TC concentrations (15, 25, 35, 45, and 55 mg/L) on the degradation effect was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 8(b). It could be seen that the degradation rate decreased continuously when the concentration increased (from 15 mg/L to 25 mg/), and the degradation efficiency was the highest when the concentration was 25 mg/L. The reason is that at low concentration, the catalyst can be fully contacted with the solution, and a large number of reactive oxygen species in the solution can react with TC molecules, resulting in a higher degradation rate [72]. However, when the initial solution concentration of TC increases and the catalyst was quantitative, the generated active sites and the surface area of bubbles used for the reaction cannot meet the progress of the catalytic reaction, resulting in a decrease in the degradation rate of TC [73]. By calculating the degradation quality, it was found that although the degradation rate decreased when the initial concentration of TC increased, the degradation quality showed an increasing state, indicated that the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites still had an excellent sonocatalytic degradation effect for high concentrations of TC.

3.2.4. Influence of ultrasonic power

The effect of ultrasonic power on the degradation rate was shown in Fig. 8(c). When the ultrasonic power was small, the degradation rate was lower. This is because with the increase of ultrasonic power, not only the energy of cavitation is enhanced, but also the threshold of cavitation is lowered. Therefore, more cavitation microbubbles will be generated during the ultrasonic process, and accordingly more active free radicals will be generated, which significantly improves the catalytic activity [74].

3.2.5. Effect of different ultrasound time

Fig. 9a showed the degradation of TC at different time without catalyst and with Ag3PO4, CoWO4, and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 catalysts, respectively. It could be seen that when the degradation time was 120 min, the self-degradation of TC was only 34.52 % without the addition of catalyst. Among the three catalysts, the degradation effect of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was the best, reaching 73.45 %, which was 1.6 times that of CoWO4 (45.11 %) and 1.5 times that of Ag3PO4 (48.41 %), respectively.

Fig. 9.

Degradation of TC in different degradation systems (a) and plots of -ln (Ct/C0) vs ultrasonic time (b) (Catalyst addition = 1 g/L, Initial concentration of TC = 15 mg/L, Ultrasonic power = 500 W).

The kinetic behavior of TC degradation under different catalysts was investigated by using pseudo-first-order equations, and the results were shown in Fig. 9b. The sonocatalytic rate constant could be estimated by Eq. (3).

| (3) |

where is the initial drug concentration, is the drug concentration at time t, t is the irradiation time, and k is the rate constant. The first-order rate constants k of Ag3PO4, CoWO4 and 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 were 0.00404 min−1, 0.00409 min−1 and 0.01454 min−1, respectively. It could be seen that k value of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 was the largest, which was 3.55 times that of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4. The synergy factor (SF) was obtained by Eq. (4) [75], [76], it was found that SF > 1 (SF = 1.79), indicated that Ag3PO4 compound CoWO4 has a positive synergistic effect on the degradation of TC.

| (4) |

To sum up, when the addition amount of sonocatalyst was 1 g/L, the initial concentration of TC was 15 mg/L, the ultrasonic power was 500 W, and the ultrasonic time was 90 min, the degradation rate of TC by the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites was 75.3 %.

3.2.6. Effect of adding K2S2O8

According to literature reports, SO4-• can be generated by ultrasonic activation after adding persulfate during the degradation process [77]. Compared with •OH, SO4-• has greater redox capacity and longer half-life, which may help to enhance the degradation effect [78], [79]. Therefore, K2S2O8 in different concentrations was added during the degradation process, and their influence on the degradation effect was studied. The results were presented in Fig. 10. It could be observed that adding K2S2O8 can significantly improve the degradation rate and shorten the degradation time. When 10 mg of K2S2O8 was added, the degradation rate of TC could reach 97.89 % in 10 min. It showed that K2S2O8 was an ideal additive in sonocatalytic degradation reaction, which had a synergistic effect with the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites in the degradation process.

Fig. 10.

Effect of adding K2S2O8 on the degradation rate.

3.3. Mechanism of sonocatalysis

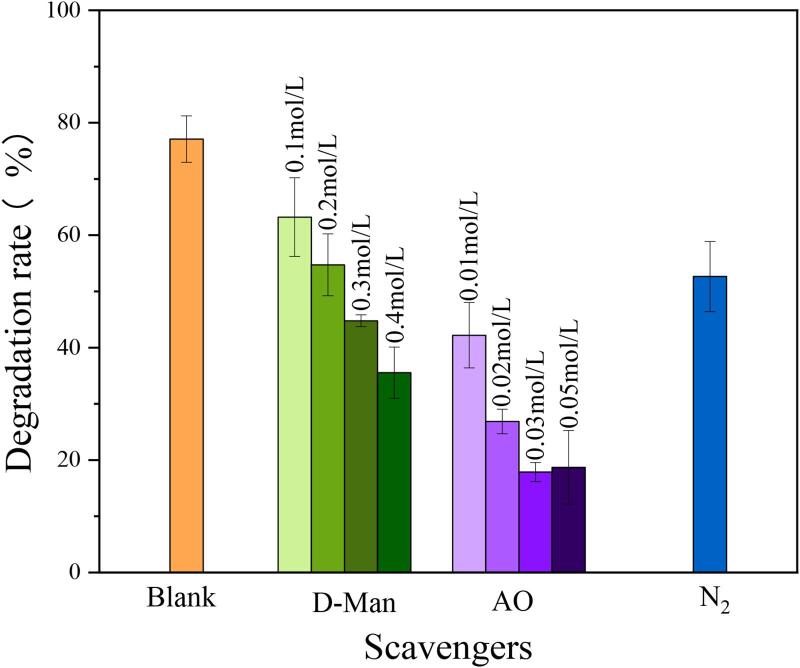

In order to study the main active substances in the degradation of TC by 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites, d-Man (•OH scavengers), AO (h+ scavengers), N2 (•O2– scavengers) were added as scavengers to the TC degradation process. The results were presented in Fig. 11. It could be observed that the degradation rate of TC decreased when d-Man and N2 were added, but did not fluctuate significantly. In contrast, the degradation rate decreased significantly when AO was added. It showed that h+ was the primary active substance, and •OH and •O2– were auxiliary active substances.

Fig. 11.

Degradation rate of TC after adding different scavengers.

The semiconductor band gap positions have an essential impact on their catalytic performance, as they determine the interfacial charge transfer behavior. Therefore, the band structures and semiconductor type of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 were analyzed by using the Mott-Schottky dot plots, as shown in Fig. 12. Flat band potentials (Ef) can be estimated from intercepts of the X-axis and are close to Fermi Levels (EF) [80]. The Ef of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 were 1.45 V and −0.55 V versus saturated calomel electrode (SCE), respectively [81]. According to the Nernst equation, the potentials are 1.69 V and −0.31 V (vs NHE), respectively. For n-type semiconductors, the position of CB is 0.1–0.3 V above the Ef, and for p-type semiconductors, the position of VB is 0.1–0.3 V above the Ef [82]. It could be known from Fig. 6b that the Eg of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 were 2.55 eV and 2.64 eV, respectively. Since the energy difference of 1 eV in solid-state physics is the same as the difference in energy of 1 V in the field of electrochemistry. According to the empirical formula EVB = ECB + Eg [83], the calculated VB values of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 were 1.89 V and 2.13 V, respectively, and the CB values were −0.66 V and −0.51 V.

Fig. 12.

Mott-Schottky dot plots of Ag3PO4 (a) and CoWO4 (b).

Based on the above discussion about the band structure, the left side of Fig. 13 showed the band arrangement diagram of the composite 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 before contact. As observed, the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) of Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 generated h+ and e-, respectively, because of the appropriate band structure. As shown on the right of Fig. 13, when Ag3PO4 formed heterojunctions with CoWO4, e- on CoWO4 CB spontaneously transfered to VB on Ag3PO4. Depletion layer was generated on the CoWO4 side and accumulation layer was formed on the Ag3PO4 side, forming the internal electric field from CoWO4 to Ag3PO4. Since e- was acquired by Ag3PO4, the binding energy of Ag and P in Ag3PO4 decreased. Conversely, the binding energy of Co and W in CoWO4 increased due to the loss of e- in CoWO4, which was consistent with the XPS results [84].Then the e- in the CB of CoWO4 were recombined with the h+ in the VB of Ag3PO4 through conventional charge separation [85]. Therefore, the e- of Ag3PO4 on relatively negative CB and the h+ of CoWO4 on relatively positive VB are maintained, facilitating to produce more radicals •O2– and •OH [86]. Then the e- on the CB (Ag3PO4) reacted with the adsorbed O2 to generate •O2–, because the CB of Ag3PO4 more negative than the potential of O2/•O2– (E0(O2/•O2–) = −0.33 V). Meanwhile, a part of the h+ on VB (CoWO4) could directly catalyze TC, and the other part h+ could oxidize OH– to •OH (because its oxidation potential is higher than OH–/•OH (1.99 V). According to the above mechanism, Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 produced interfacial contact, which effectively prevented e--h+ pairs from recombining, improves its separation efficiency, and generated more e- and h+, thereby enhancing the degradation activity. Possible reactions were listed in Eq. (5)-(8). These results indicated that the heterojunction formed by Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 could effectively improve the ultrasonic catalytic performance.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Fig. 13.

Schematic diagram of the sonocatalysis mechanism.

After the addition of K2S2O8 Eq. (9), S2O82- could react with the e- reaction on Ag3PO4 VB to produce SO4-• [87]. SO4-• is a strong oxidant and can effectively degrade many organic pollutants Eq. (10) [79]. In addition, SO4-• can also be converted to •OH by reacting with H2O in solution, which can degrade TC and further improve the catalytic activity [88] Eq. (8). In this paper, the reaction time was reduced, and the degradation effect was improved by adding K2S2O8.

| (9) |

| (10) |

3.4. Stability and cycling

The stability and reproducibility of sonocatalytic materials is critical for their applications [56]. Therefore, the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites was recycled 4 times. All nanocomposites were collected after each sonication, washed and dried at 60 °C for 2 h. The results were shown in Fig. 14(a). It could be observed that the degradation rate was only reduced by 3 % after 4 cycles. This result indicated that the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites had excellent reproducibility. As shown in Fig. 14(b), the XPS patterns of the recycled composites and the newly prepared composites were the same. The decrease in TC degradation rate might be related to the decline of Ag ions. Therefore, after cycling experiments, we used ICP to measure the leaching of individual ions in the solution. The results showed that the leaching rate of Ag ions was slightly higher, about 2.65 %, and the leaching rates of Co and W were lower, 0.0008 % and 1.77 %, respectively. It showed that Ag ions were still consumed in the experimental process, but had little effect on the degradation rate. Both XPS and ICP results proved good stability of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites.

Fig. 14.

Recovery efficiency of Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites (a) and XPS spectra before and after sonocatalytic degradation (b).

3.5. Comparison of catalytic activity with published catalysts

Due to the harmful effects of antibiotic wastewater pollution on the environment and human beings, many research have been devoted to developing materials that can degrade TC wastewater in recent years. Table 2 reports a comprehensive comparison of this study, together with other sonocatalysts for TC degradation activity published recently. It could be observed in the table that it usually takes a long time for each material to degrade TC. For example, Qiao et al. [9] used the ternary SrTiO3/Ag2S/CoWO4 composites as a sonocatalyst to degrade TC solution in 300 min. In contrast, the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites in this study can achieve a degradation rate of 75.3 % in only 120 min. In addition, Reza Darvishi Cheshmeh et al. [89] found that adding some free radical enhancers (hydrogen peroxide, periodate, persulfate, and percarbonate, etc.) during the reaction can increase the degradation effect. For example, Hoseini et al. [90] added H2O2 in TiO2 ultrasonic degradation of TC, and the degradation rate could reach 100 % within 75 min. Compared with that, this work achieved a degradation rate of 97.89 % within 10 min by adding K2S2O8, which considerably shortened the reaction time and improved the degradation effect. It indicated that combining K2S2O8 with 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 is a promising TC degradation scheme. These results provide valuable references for the practical application of 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4.

Table 2.

The comparative effect of the composites material in this study and other reported catalysts in the degradation of tetracycline.

| Catalyst | Source and method of degradation | TC concentration (mg/L) | Catalyst dosage (g/L) | pH | Degradation Efficiency and Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SrTiO3/Ag2S/CoWO4 | Ultrasonic | 10 | 1.0 | 6 | 86.47 % in 300 min | [9] |

| BiOI | Ultrasonic | 10 | 0.5 | – | 95.5 % in 70 min | [91] |

| BiOBr/MgFe2O4 | Ultrasonic | 10 | 2.0 | 7 | 91.10 % in 30 min | [84] |

| ZnO/NC | Ultrasonic+0.01 M PMS | 50 | 0.5 | 4 | 96.4 % in 15 min | [89] |

| TiO2 | Ultrasonic+100 mg/L H2O2 | 75 | 0.25 | 4 | 100 % in 75 min | [90] |

| FeII-MIL-88B/GO/P25 | Ultrasonic+20 mM H2O2 | 10 | 0.3 | 5 | 83.3 % in 7 min | [92] |

| 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 | Ultrasonic | 25 | 1.0 | – | 75.3 % in 120 min | This work |

| 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 | Ultrasonic+10 mg K₂S₂O₈ | 25 | 1.0 | – | 97.89 % in 10 min | This work |

4. Conclusion

The 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composite sonocatalyst was prepared for the first time by a simple hydrothermal method and characterized by SEM, TEM, XRD, XPS, BET and UV–vis DRS. 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 had an average particle size of 20 ∼ 50 nm, a narrow band gap of 2.60 eV and a large specific surface area. Compared with Ag3PO4 and CoWO4, the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites had a better sonocatalytic degradation effect on TC solution, and the degradation rate could get 75.3 % within 90 min. After adding 10 mg of K2S2O8, the degradation effect could reach 97.89 % in 10 min. The mechanism was that Ag3PO4 and CoWO4 form an S-scheme heterojunction, which accelerated the separation efficiency of e--h+, and the generated h+, •OH, and •O2– effectively mineralized TC. In addition, the 0.6Ag3PO4/CoWO4 composites still had good recyclability and high stability after 4 cycles. This study provides a feasible idea for the modification of CoWO4, and provides a direction for preparing a new high-efficiency sonocatalyst and the solution to wastewater treatment problems.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Young Scientific and Technological Talents Seedling Project of Education Department of Liaoning Province (LQN202016) and Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2020-MS-136, 2019-ZD-0190).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Polianciuc S.I., Gurzău A.E., Kiss B., Georgia Ştefan M., Loghin F. Antibiotics in the environment: causes and consequences. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2020;93:231–240. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdelall M.F., Hafez S.S., El Fayad M., Nour El-Din H.A., Abdallah S.A. Tetracycline Resistant Genes as Bioindicators of Water Pollution. J. Biol. Res. 2020;93:9–21. doi: 10.4081/jbr.2020.8490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting Zhu T., Xian Su Z., Xia Lai W., Bin Zhang Y., Wen Liu Y. Insights into the fate and removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes using biological wastewater treatment technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;776:145906. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezaei S.S., Kakavandi B., Noorisepehr M., Isari A.A., Zabih S., Bashardoust P. Photocatalytic oxidation of tetracycline by magnetic carbon-supported TiO2 nanoparticles catalyzed peroxydisulfate: Performance, synergy and reaction mechanism studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;258:117936. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sodhi K.K., Kumar M., Balan B., Dhaulaniya A.S., Shree P., Sharma N., Singh D.K. Perspectives on the antibiotic contamination, resistance, metabolomics, and systemic remediation. SN Appl. Sci. 2021;3:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-04003-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Z., Zhang Y., Shen X., Duoerkun G., Zhu B., Zhang L., Li M., Chen Z. Fabrication of g-C3N4/BiOBr heterojunctions on carbon fibers as weaveable photocatalyst for degrading tetracycline hydrochloride under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;386 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H., Hu S., Zhao H., Luo X., Liu Y., Deng C., Yu Y., Hu T., Shan S., Zhi Y., Su H., Jiang L. High-performance Fe-doped ZIF-8 adsorbent for capturing tetracycline from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;416 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H., Zhang C.Y., Chang T.L., Su J.Z., Wu X.F., Song M.C., Wang L.L., Yang H., Ci L.J. Preparation and characterization of Sn-doped In2.77S4 nanosheets as a visible-light-induced photocatalyst for tetracycline degradation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021;32:2822–2831. doi: 10.1007/s10854-020-05035-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiao J., Zhang H., Li G., Li S., Qu Z., Zhang M., Wang J., Song Y. Fabrication of a novel Z-scheme SrTiO3/Ag2S/CoWO4 composite and its application in sonocatalytic degradation of tetracyclines. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019;211:843–856. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q.Q., Ying G.G., Pan C.G., Liu Y.S., Zhao J.L. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: Source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:6772–6782. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peak N., Knapp C.W., Yang R.K., Hanfelt M.M., Smith M.S., Aga D.S., Graham D.W. Abundance of six tetracycline resistance genes in wastewater lagoons at cattle feedlots with different antibiotic use strategies. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagamine M., Osial M., Jackowska K., Krysinski P., Widera-Kalinowska J. Tetracycline Photocatalytic Degradation under CdS Treatment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020;8:483. doi: 10.3390/jmse8070483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao J., Zhu Y., Yuan S., Wang F., Tang H., Bao Z., Zhou H., Chen Y. Adsorption of Tetracycline with Reduced Graphene Oxide Decorated with MnFe2O4 Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018;13 doi: 10.1186/s11671-018-2814-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isari A.A., Mehregan M., Mehregan S., Hayati F., Rezaei Kalantary R., Kakavandi B. Sono-photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline and pharmaceutical wastewater using WO3/CNT heterojunction nanocomposite under US and visible light irradiations: A novel hybrid system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;390 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan M., Kaur N., Bansal P., Kumar R., Srinivasan S., Chaudhary G.R. Proficient Photocatalytic and Sonocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using CuO Nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6123178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassani A., Eghbali P., Kakavandi B., Lin K.Y.A., Ghanbari F. Acetaminophen removal from aqueous solutions through peroxymonosulfate activation by CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposite: Insight into the performance and degradation kinetics. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2020.101127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamal Sisi A., Fathinia M., Khataee A., Orooji Y. Systematic activation of potassium peroxydisulfate with ZIF-8 via sono-assisted catalytic process: Mechanism and ecotoxicological analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;308 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bethi B., Sonawane S.H., Bhanvase B.A., Gumfekar S.P. Nanomaterials-based advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: A review. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2016;109:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2016.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karim A.V., Hassani A., Eghbali P., Nidheesh P.V. Nanostructured modified layered double hydroxides (LDHs)-based catalysts: A review on synthesis, characterization, and applications in water remediation by advanced oxidation processes. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022;26 doi: 10.1016/j.cossms.2021.100965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanias A., Frontistis Z., Vakros J., Arvaniti O.S., Ribeiro R.S., Silva A.M.T., Faria J.L., Gomes H.T., Mantzavinos D. Degradation of methylparaben by sonocatalysis using a Co–Fe magnetic carbon xerogel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G., Ma X., Liu J., Qin L., Li B., Hu Y., Cheng H. Design and performance of a novel direct Z-scheme NiGa2O4/CeO2 nanocomposite with enhanced sonocatalytic activity. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cako E., Gunasekaran K.D., Cheshmeh Soltani R.D., Boczkaj G. Ultrafast degradation of brilliant cresyl blue under hydrodynamic cavitation based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) Water Resour. Ind. 2020;24 doi: 10.1016/j.wri.2020.100134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyikoglu R., Khataee A., Lin H., Orooji Y. Vanadium (V)-doped ZnFe layered double hydroxide for enhanced sonocatalytic degradation of pymetrozine. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;434 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.134730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khataee A., Kalderis D., Motlagh P.Y., Binas V., Stefa S., Konsolakis M. Synthesis of copper (I, II) oxides/hydrochar nanocomposites for the efficient sonocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021;95:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2020.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youcef R., Benhadji A., Zerrouki D., Fakhakh N., Djelal H., Taleb Ahmed M. Electrochemical synthesis of CuO–ZnO for enhanced the degradation of Brilliant Blue (FCF) by sono-photocatalysis and sonocatalysis: kinetic and optimization study. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2021;133:541–561. doi: 10.1007/s11144-021-01961-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu P., Park B., Choi J., Thokchom B., Pandit A.B., Khim J. A review on heterogeneous sonocatalyst for treatment of organic pollutants in aqueous phase based on catalytic mechanism. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;45:29–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun M., Lin X., Meng X., Liu W., Ding Z. Ultrasound-driven ferroelectric polarization of TiO2/Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 heterojunctions for improved sonocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2022;892 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.162065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassani A., Eghbali P., Metin Ö. Sonocatalytic removal of methylene blue from water solution by cobalt ferrite/mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4) nanocomposites: response surface methodology approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:32140–32155. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassani A., Malhotra M., Karim A.V., Krishnan S., Nidheesh P.V. Recent progress on ultrasound-assisted electrochemical processes: A review on mechanism, reactor strategies, and applications for wastewater treatment. Environ. Res. 2022;205:112463. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghanbari F., Zirrahi F., Lin K.Y.A., Kakavandi B., Hassani A. Enhanced electro-peroxone using ultrasound irradiation for the degradation of organic compounds: A comparative study. J. Environ Chem. Eng. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan Y.Y., Pang Y.L., Lim S., Chong W.C. Sonocatalytic degradation of Congo red by using green synthesized silver doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 2020;46:1948–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saqlain S., Cha B.J., Kim S.Y., Ahn T.K., Park C., Oh J.M., Jeong E.C., Seo H.O., Kim Y.D. Visible light-responsive Fe-loaded TiO2 photocatalysts for total oxidation of acetaldehyde: Fundamental studies towards large-scale production and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;505 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmadi S., Rahdar A., Igwegbe C.A., Mortazavi-Derazkola S., Banach A.M., Rahdar S., Singh A.K., Rodriguez-Couto S., Kyzas G.Z. Praseodymium-doped cadmium tungstate (CdWO4) nanoparticles for dye degradation with sonocatalytic process. Polyhedron. 2020;190:114792. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu P., Li W., Thokchom B., Park B., Cui M., Zhao D., Khim J. Uniform core-shell structured magnetic mesoporous TiO2 nanospheres as a highly efficient and stable sonocatalyst for the degradation of bisphenol-A. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:6492–6500. doi: 10.1039/c4ta06891b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadeghi M., Farhadi S., Zabardasti A. Fabrication of a novel magnetic CdS nanorod/NiFe2O4/NaX zeolite nanocomposite with enhanced sonocatalytic performance in the degradation of organic dyes. New J. Chem. 2020;44:8386–8401. doi: 10.1039/d0nj01393e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding Z., Sun M., Liu W., Sun W., Meng X., Zheng Y. Ultrasonically synthesized N-TiO2/Ti3C2 composites: Enhancing sonophotocatalytic activity for pollutant degradation and nitrogen fixation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;276:119287. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassani A., Çelikdağ G., Eghbali P., Sevim M., Karaca S., Metin Ö. Heterogeneous sono-Fenton-like process using magnetic cobalt ferrite-reduced graphene oxide (CoFe2O4-rGO) nanocomposite for the removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:841–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paramarta V., Saleh R. Wastewater treatment by sonocatalysis and sonophotocatalysis using Fe3O4/SnO2 composite supported on nanographene platelets. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023;2018:1–7. doi: 10.1063/1.5064010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia H., Stark J., Zhou L.Q., Ling C., Sekito T., Markin Z. Different catalytic behavior of amorphous and crystalline cobalt tungstate for electrochemical water oxidation. RSC Adv. 2012;2:10874–10881. doi: 10.1039/c2ra21993j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling C., Zhou L.Q., Jia H. First-principles study of crystalline CoWO4 as oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. RSC Adv. 2014;4:24692–24697. doi: 10.1039/c4ra03893b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He G., Li J., Li W., Li B., Noor N., Xu K., Hu J., Parkin I.P. One pot synthesis of nickel foam supported self-assembly of NiWO4 and CoWO4 nanostructures that act as high performance electrochemical capacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:14272–14278. doi: 10.1039/c5ta01598g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taneja P., Sharma S., Umar A., Mehta S.K., Ibhadon A.O., Kansal S.K. Visible-light driven photocatalytic degradation of brilliant green dye based on cobalt tungstate (CoWO4) nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018;211:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.02.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu X., Shen J., Li N., Ye M. Facile synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/CoWO4 nanocomposites with enhanced electrochemical performances for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;150:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.10.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandey P.K., Bhave N.S., Kharat R.B. Characterization of spray deposited CoWO4 thin films for photovoltaic electrochemical studies. J. Mater. Sci. 2007;42:7927–7933. doi: 10.1007/s10853-007-1551-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alborzi A., Abedini A. Synthesis, characterization, and investigation of magnetic and photocatalytic property of cobalt tungstate nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016;27:4057–4061. doi: 10.1007/s10854-015-4262-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmadi F., Rahimi-Nasrabadi M., Fosooni A., Daneshmand M. Synthesis and application of CoWO4 nanoparticles for degradation of methyl orange. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016;27:9514–9519. doi: 10.1007/s10854-016-5002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montini T., Gombac V., Hameed A., Felisari L., Adami G., Fornasiero P. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic performance of transition metal tungstates. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010;498:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prabavathi S.L., Govindan K., Saravanakumar K., Jang A., Muthuraj V. Construction of heterostructure CoWO4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite as an efficient visible-light photocatalyst for norfloxacin degradation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019;80:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.08.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui H., Li B., Zhang Y., Zheng X., Li X., Li Z., Xu S. Constructing Z-scheme based CoWO4/CdS photocatalysts with enhanced dye degradation and H2 generation performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43:18242–18252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.08.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senthil R.A., Osman S., Pan J., Khan A., Yang V., Kumar T.R., Sun Y., Lin Y., Liu X., Manikandan A. One-pot preparation of AgBr/α-Ag2WO4 composite with superior photocatalytic activity under visible-light irradiation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020;586 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arumugam Senthil R., Khan A., Pan J., Osman S., Yang V., Kumar T.R., Sun Y., Liu X. A facile single-pot synthesis of visible-light-driven AgBr/Ag2CO3 composite as efficient photocatalytic material for water purification. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020;586 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Senthil R.A., Wu Y., Liu X., Pan J. A facile synthesis of nano AgBr attached potato-like Ag2MoO4 composite as highly visible-light active photocatalyst for purification of industrial waste-water. Environ. Pollut. 2021;269:116034. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mousavi M., Habibi-Yangjeh A., Abitorabi M. Fabrication of novel magnetically separable nanocomposites using graphitic carbon nitride, silver phosphate and silver chloride and their applications in photocatalytic removal of different pollutants using visible-light irradiation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;480:218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li N., Chen J., Chen X., Lai Y., Yu C., Yao L., Liang Y. Novel visible-light-driven SrCoO3/Ag3PO4 heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic performance for tetracycline degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29:9693–9706. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang H., Fu Y., Chang S., Xie S., Tang G. Construction of Ag3PO4/Ag2MoO4 Z-scheme heterogeneous photocatalyst for the remediation of organic pollutants. Cuihua Xuebao/Chinese J. Catal. 2017;38:337–347. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(16)62570-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X., Zhang H., Xiang Y., Hao S., Zhang Y., Guo R., Cheng X., Xie M., Cheng Q., Li B. Synthesis of silver phosphate/graphene oxide composite and its enhanced visible light photocatalytic mechanism and degradation pathways of tetrabromobisphenol A. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018;342:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jun B.M., Kim Y., Yoon Y., Yea Y., Park C.M. Enhanced sonocatalytic degradation of recalcitrant organic contaminants using a magnetically recoverable Ag/Fe-loaded activated biochar composite. Ceram. Int. 2020;46:22521–22531. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin D.J., Liu G., Moniz S.J.A., Bi Y., Beale A.M., Ye J., Tang J. Efficient visible driven photocatalyst, silver phosphate: performance, understanding and perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:7808–7828. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00380f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Senthil R.A., Osman S., Pan J., Sun Y., Kumar T.R., Manikandan A. A facile hydrothermal synthesis of visible-light responsive BiFeWO6/MoS2 composite as superior photocatalyst for degradation of organic pollutants. Ceram. Int. 2019;45:18683–18690. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.06.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu L., Wang S.H., Jin Y., Liu N.P., Wu X.Q., Wang X. Preparation of Cobalt tungstate nanomaterials and study on sonocatalytic degradation of Safranint. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;276:119405. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He L.L., Guo Y.X., Zhu Y., Guo X.T., Wang N., Wang X.F., Wang X. Fabrication of Ag2O/MgWO4 p-n heterojunction with enhanced sonocatalytic decomposition performance for Rhodamine B. Mater. Lett. 2021;284:128927. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2020.128927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pullar R.C., Farrah S., Alford N.M.N. MgWO4, ZnWO4, NiWO4 and CoWO4 microwave dielectric ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007;27:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2006.05.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X., Yu S., Li Z.H., He L.L., Liu Q.L., Hu M.Y., Xu L., Wang X.F., Xiang Z. Fabrication Z-scheme heterojunction of Ag2O/ZnWO4 with enhanced sonocatalytic performances for meloxicam decomposition: Increasing adsorption and generation of reactive species. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;405 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.S. Selvi, R. Rajendran, D. Barathi, N. Jayamani, Facile Synthesis of CeO2/CoWO4 Hybrid Nanocomposites for High Photocatalytic Performance and Investigation of Antimicrobial Activity, J. Electron. Mater. 50 (2021) 2890–2902. doi:10.1007/s11664-020-08729-z.

- 65.Jin Z., Yan X., Hao X. Rational design of a novel p-n heterojunction based on 3D layered nanoflower MoSx supported CoWO4 nanoparticles for superior photocatalytic hydrogen generation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;569:34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rajagopal S., Nataraj D., Khyzhun O.Y., Djaoued Y., Robichaud J., Mangalaraj D. Hydrothermal synthesis and electronic properties of FeWO4 and CoWO4 nanostructures. J. Alloys Compd. 2010;493:340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.12.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu S., Yu Y., Qiao K., Meng J., Jiang N., Wang J. A simple synthesis route of sodium-doped g-C3N4 nanotubes with enhanced photocatalytic performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021;406 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.S. Sajjadi, A. Khataee, R. Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani, A. Hasanzadeh, N, S co-doped graphene quantum dot–decorated Fe3O4 nanostructures: Preparation, characterization and catalytic activity, J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 127 (2019) 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.12.014.

- 69.Chang F., Lei B., Yang C., Wang J., Hu X. Ultra-stable Bi4O5Br 2/Bi2S3 n-p heterojunctions induced simultaneous generation of radicals [rad]OH and [rad]O2− and NO conversion to nitrate/nitrite species with high selectivity under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;413 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Motlagh P.Y., Khataee A., Hassani A., Sadeghi Rad T. ZnFe-LDH/GO nanocomposite coated on the glass support as a highly efficient catalyst for visible light photodegradation of an emerging pollutant. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;302 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.P. Eghbali, A. Hassani, B. Sündü, Ö. Metin, Strontium titanate nanocubes assembled on mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (SrTiO3/mpg-C3N4): Preparation, characterization and catalytic performance, J. Mol. Liq. 290 (2019) 111208. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111208.

- 72.S. Dehghan, B. Kakavandi, R.R. Kalantary, Heterogeneous sonocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using ZnO@Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposite: Influential factors, reusability and mechanisms, J. Mol. Liq. 264 (2018) 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2018.05.020.

- 73.Geng M., Thagard S.M. The effects of externally applied pressure on the ultrasonic degradation of Rhodamine B. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chang F., Wu F., Yan W., Jiao M., Zheng J., Deng B., Hu X. Oxygen-rich bismuth oxychloride Bi12O17Cl2 materials: construction, characterization, and sonocatalytic degradation performance. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;50:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fedorov K., Plata-Gryl M., Khan J.A., Boczkaj G. Ultrasound-assisted heterogeneous activation of persulfate and peroxymonosulfate by asphaltenes for the degradation of BTEX in water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;397 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.N. Yousef Tizhoosh, A. Khataee, R. Hassandoost, R. Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani, E. Doustkhah, Ultrasound-engineered synthesis of WS2@CeO2 heterostructure for sonocatalytic degradation of tylosin, Ultrason. Sonochem. 67 (2020) 105114. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Chen Y., Deng P., Xie P., Shang R., Wang Z., Wang S. Heat-activated persulfate oxidation of methyl- and ethyl-parabens: Effect, kinetics, and mechanism. Chemosphere. 2017;168:1628–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.A.A. Isari, S. Moradi, S.S. Rezaei, F. Ghanbari, E. Dehghanifard, B. Kakavandi, Peroxymonosulfate catalyzed by core/shell magnetic ZnO photocatalyst towards malathion degradation: Enhancing synergy, catalytic performance and mechanism, Sep. Purif. Technol. 275 (2021) 119163. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119163.

- 79.Yuan R., Jiang M., Gao S., Wang Z., Wang H., Boczkaj G., Liu Z., Ma J., Li Z. 3D mesoporous Α-Co(OH)2 nanosheets electrodeposited on nickel foam: A new generation of macroscopic cobalt-based hybrid for peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;380 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.F. Chang, X. Wang, S. Zhao, X. Zhang, X. Hu, Fabrication of Bi12GeO20/Bi2S3 hybrids with surface oxygen vacancies by a facile CS2-mediated manner and enhanced photocatalytic performance in water and saline water, Sep. Purif. Technol. 287 (2022) 120532. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120532.

- 81.Chang F., Yan W., Wang X., Peng S., Li S., Hu X. Strengthened photocatalytic removal of bisphenol a by robust 3D hierarchical n-p heterojunctions Bi4O5Br 2-MnO2 via boosting oxidative radicals generation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;428 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.F. Chang, X. Wang, C. Yang, S. Li, J. Wang, W. Yang, F. Dong, X. Hu, D. guo Liu, Y. Kong, Enhanced photocatalytic NO removal with the superior selectivity for NO2−/NO3− species of Bi12GeO20-based composites via a ball-milling treatment: Synergetic effect of surface oxygen vacancies and n-p heterojunctions, Compos. Part B Eng. 231 (2022) 109600. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109600.

- 83.Chen Y., Jiang Y., Chen B., Ye F., Duan H., Cui H. Construction of S-doped MgO coupled with g-C3N4 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. New J. Chem. 2021;45:16227–16237. doi: 10.1039/d1nj01956b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.L. He, J. Bai, X. Li, S. Qi, S. Li, X. Wang, BiOBr/MgFe2O4 composite as a novel catalyst for the sonocatalytic removal of tetracycline in aqueous environment 33 (2022).

- 85.Qu J., Du Y., Feng Y., Wang J., He B., Du M., Liu Y., Jiang N. Visible-light-responsive K-doped g-C3N4/BiOBr hybrid photocatalyst with highly efficient degradation of Rhodamine B and tetracycline. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2020.105023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.F. Chang, S. Li, Z. Shi, Y. Qi, D. guo Liu, X. Liu, S. Chen, Boosted photocatalytic NO removal performance by S-scheme hierarchical composites WO3/Bi4O5Br2 prepared through a facile ball-milling protocol, Sep. Purif. Technol. 278 (2022) 119662. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119662.

- 87.Madihi-Bidgoli S., Asadnezhad S., Yaghoot-Nezhad A., Hassani A. Azurobine degradation using Fe2O3@multi-walled carbon nanotube activated peroxymonosulfate (PMS) under UVA-LED irradiation: performance, mechanism and environmental application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.H. Zhu, B. Yang, J. Yang, Y. Yuan, J. Zhang, Persulfate-enhanced degradation of ciprofloxacin with SiC/g-C3N4 photocatalyst under visible light irradiation, Chemosphere. 276 (2021) 130217. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Soltani R.D.C., Mashayekhi M., Naderi M., Boczkaj G., Jorfi S., Safari M. Sonocatalytic degradation of tetracycline antibiotic using zinc oxide nanostructures loaded on nano-cellulose from waste straw as nanosonocatalyst. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;55:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoseini M., Safari G.H., Kamani H., Jaafari J., Ghanbarain M., Mahvi A.H. Sonocatalytic degradation of tetracycline antibiotic in aqueous solution by sonocatalysis. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2013;95:1680–1689. doi: 10.1080/02772248.2014.901328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhong L.L., Wang C., Cui X., Hu J., Mo R., Guo J. Study on Sonocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride by Mesoporous BiOI Microspherical Under Ultrasonic Irradiation. SSRN Electron. J. 2021:1–28. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3875192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Geng N., Chen W., Xu H., Ding M., Xie Z., Wang A. Removal of tetracycline hydrochloride by Z-scheme heterojunction sono-catalyst acting on ultrasound/H2O2 system. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022;165:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2022.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.