Abstract

The synthesis of macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I [Mph(A)], which inactivates erythromycin, is inducible by erythromycin. The expression of high-level resistance to erythromycin requires the mph(A) and mrx genes, which encode Mph(A) and an unidentified protein, respectively. We have studied the mphR(A) gene, which regulates the inducible expression of mph(A). An analysis of the synthesis of Mph(A) in minicells and results of a complementation test indicated that mphR(A) is located downstream from mrx and that its product, MphR(A), represses the production of Mph(A). DNA sequencing indicated that the mph(A), mrx, and mphR(A) genes exist as a cluster that begins with mph(A) and that the deduced amino acid sequence of MphR(A) can adopt an α-helix–turn–α-helix structure. To study the regulation of gene expression by MphR(A), we performed Northern blotting and primer extension. A transcript of 2.9 kb that corresponded to the transcript of mph(A) through mphR(A) was detected, and its level was elevated upon exposure of cells to erythromycin. Gel mobility shift assays and DNase I footprinting indicated that MphR(A) binds specifically to the promoter region of mph(A), and the amount of DNA shifted as a results of the binding of MphR(A) decreased as the concentration of erythromycin was increased. These results indicate that transcription of the mph(A)-mrx-mphR(A) operon is negatively regulated by the binding of a repressor protein, MphR(A), to the promoter of the mph(A) gene and is activated upon inhibition of binding of MphR(A) to the promoter in the presence of erythromycin.

Macrolide antibiotics are active mainly against gram-positive bacteria, but erythromycin (EM) and clarithromycin are active against Helicobacter, Legionella, and Mycoplasma spp. (6, 31). Furthermore, it is becoming clear that some of these antibiotics have various other pharmacological activities, for example, as anti-inflammatory agents in addition to antibacterial agents (11). Thus, the medical use of macrolide antibiotics has increased significantly in recent years.

Resistance to macrolide antibiotics is usually due to modification of the target site (12, 29), active efflux of the antibiotic (24), or inactivation of the antibiotic (13). However, macrolide-inactivating enzymes, namely, EM esterases (1, 20) and macrolide 2′-phosphotransferases (10, 19), that mediate such resistance have been found in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, which is naturally resistant to macrolides. Furthermore, almost all macrolide-inactivating enzymes are constitutively produced in E. coli (1, 2, 10, 20). However, the production of macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I [Mph(A); formerly MPH(2′)I] (22), which is a strong inactivator of 14-member ring macrolides, such as EM and oleandomycin (OL), is induced by EM in the original strain E. coli Tf481A (19). Furthermore, although the mph(A) gene confers low-level resistance to EM, cells that carry the mph(A) and mrx genes come to exhibit high-level resistance to EM. The deduced product of the mrx gene, Mrx, is a hydrophobic protein, but its function remains to be determined.

As an inducible macrolide resistance gene, the ermC gene, which encodes an rRNA methylase, is been well known (29). Inducible expression of ermC is regulated at the posttranscriptional level by attenuation of translation (30). However, not only the mechanism of the macrolide resistance conferred by ermC but also the structure of the ermC gene is completely different from that of the mph(A) gene.

In the present study of the inducible expression of mph(A), we identified the gene that regulates its expression and characterized the gene product. We also developed a model that explains the inducible expression of mph(A).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and antibiotics.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Expression of the mph(A) gene was induced by treatment with a subinhibitory concentration of EM (25 or 50 μg/ml) (16, 19).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description [genotype of plasmid insert(s)] | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| Tf481A | Emr; clinical isolate | 19 |

| MV1189 | Strain used for complementation and sequencing experiments | 26 |

| DH5α | Strain used for general cloning experiments | 26 |

| TH1219 | Minicell-producing strain | 25 |

| BL21(DE3) | Host strain for expression of pGEX | 5 |

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 | Indicator strain used in microbioassays | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC119 | Apr; cloning vector | 26 |

| pSTV28 | Cmr; cloning vector with origin of pACYC184 that is compatible with pUC119 | Takaraa |

| pHSG399 | Cmr; pUC19-derived cloning vector in which bla was replaced with cat | Takara 28 |

| pTZ3509 | Apr Emr [mph(A) mrx mphR(A)]; pUC119 with 4.1-kb PstI fragment | 16 |

| pTZ3519 | Apr Emr [mph(A) mrx mphR(A)]; pUC119 with 3.3-kb BamHI-PstI fragment | 16 |

| pTZ3519ORF3TGA | Apr [mrx]; derivative of pTZ3519 carrying mph(A) with nonsense mutation | 16 |

| pTZ3519ORF4TGA | Apr Emr [mph(A)]; derivative of pTZ3519 carrying mrx with nonsense mutation | 16 |

| pTZ3519Δ318 | Apr Emr [mph(A)]; derivative of pTZ3519 without mrx | 16 |

| pSTV3519Δ318 | Cmr Emr [mph(A)]; pSTV29 with 2.2-kb PstI-BamHI fragment of pTZ3519Δ318 | This study |

| pTZ3509Δ361 | Apr [mph(A)]; derivative of pTZ3509 without mph(A) and mrx | 16 |

| pSTV3509Δ361 | Cmr [mphR(A)]; pSTV29 with 1.5-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment of pTZ3509Δ361 | This study |

| pTZ3510 | Cmr Emr [mph(A) mrx mphR(A)]; pHSG399 with 4.1-kb PstI fragment of pTZ3509 | This study |

| pTZ3513 | Cmr [mrx mphR(A)]; pHSG399 with 4.1-kb pstI fragment of pTZ3509 carrying mph(A) with nonsense mutation | This study |

| pTZ3514 | Cmr Emr [mph(A) mphR(A)]; pHSG399 with 4.1-kb PstI fragment of pTZ3509 carrying mrx with nonsense mutation | This study |

| pTZ3517 | Cmr Emr [mph(A) mrx]; pHSG399 with 3.3-kb BamHI-PstI fragment of pTZ3519 | This study |

| pGEX4T-1 | Apr; cloning vector for expression of GST fusion protein | Pharmaciab |

| pGEX4T-mphR(A) | Apr [mphR(A)]; pGEX4T-1 with 0.6-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment carrying mphR(A) | This study |

Takara Shuzo Co.

Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.

Analysis of protein expression in minicells.

Minicells were prepared from E. coli TH1219 that carried the indicated plasmid, and plasmid-encoded proteins were analyzed as described previously (17). Standard proteins for determination of molecular weight were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

Enzymatic inactivation of antibiotics.

A crude preparation of enzymes was used as the source of Mph(A). The preparation of enzymes and the enzymatic inactivation of macrolide antibiotics were performed as described previously (18).

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

All DNA manipulations were performed by standard methods (26). DNA amplification by PCR was performed using Gene Taq polymerase (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Nucleotide sequences were determined with an automated DNA sequencer (PRIZM 377) and a dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (both from PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Northern blotting and primer extension analysis.

RNA was prepared from E. coli as described previously (18). A 508-bp fragment that had been amplified by PCR with primers mphA+835 (5′-GCTCGACTATAGGATCGTGATCGC) and mphA−1343 (5′-CGTAGAGATCGCCATGCACCAC) was used as the probe for mph(A) transcripts. The probe was labeled with an AlkPhos Direct labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.) and allowed to hybridize with RNA in accordance with the instructions from the manufacturer of the labeling kit. Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (18), using primer mphA−795 (5′-CCATGTCGGGCTGCAAGTGCGTACAGTTGGG), which was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase.

Construction of a plasmid carrying a fusion gene for MphR(A)-GST and purification of MphR(A).

A DNA fragment containing the mphR(A) structural gene was amplified by PCR with two primers that included EcoRI and SalI restriction sites (underlined), namely, mphR+1 (5′-AAGGTGAGAATTCATGCCCCGCCCCAAGCT) and mphR−1 (5′-GGACTCTGTCGACCTCCGTTTACGCATGTG), respectively. Plasmid pGEX-mphR(A) was constructed by subcloning an EcoRI-SalI mphR(A) fragment from pTZ3509 between the EcoRI and SalI sites of pGEXT4-1. The synthesis of the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-MphR(A) fusion protein and purification of MphR(A) were performed as described by Smith and Johnson (27). The concentration of protein was estimated by Bradford's method (3) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Gel mobility shift assay.

Labeled DNA fragments were prepared by PCR using primers that had been end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. The 66-bp fragment designated DNA-1, containing the promoter region of mph(A), was generated with primers mphA+638 (5′-CTGCCTCATCGCTAACTTTG) and mphA−703 (5′-CCTAAATGTAACAGTCA). The 77- and 60-bp fragments designated DNA-2 and DNA-3 were generated with primers mphA+591 (5′-GGTAAGCAGAGTTTTTGAAATGTAAGGCCT) and mphA−667 (5′-GGCACTGTTGCAAAGTTA) and primers mphA+696 (5′-CATTTAGGTGGCTAAACCC) and mphA−755 (5′-CGGTCGTGACTACGGTCATGA), respectively. The 32P-labeled DNA fragments (approximately 5 × 103 cpm/reaction) were incubated with MphR(A) in DNA binding buffer that contained 5 μg of bovine serum albumin, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), and 10% glycerol in a total volume 30 μl (7). After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixtures were analyzed by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in Tris-borate buffer.

DNase I footprinting.

DNase I footprinting of the promoter region of mph(A) was performed using a 165-bp DNA fragment that had been amplified by PCR with primer mphA−755, which had been end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP, and primer mphA+591 (4). Reaction mixtures for analysis of binding contained approximately 1 pmol of labeled DNA and 10, 25, or 50 pmol of purified MphR(A) in 50 μl of a reaction buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 μg of bovine serum albumin, 0.2 μg of poly(dI-dC), and 10% glycerol. Each reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Then, 0.5 U of DNase I (Promega) was added to the reaction mixture and the mixture was incubated for 1 min at room temperature. The DNA fragments were analyzed by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sequencing with a G+A sequencing ladder (15).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession number AB038042.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification and nucleotide sequence of the mphR(A) gene.

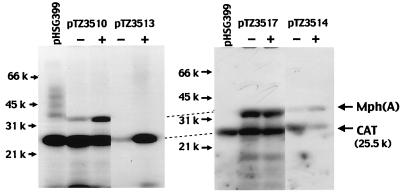

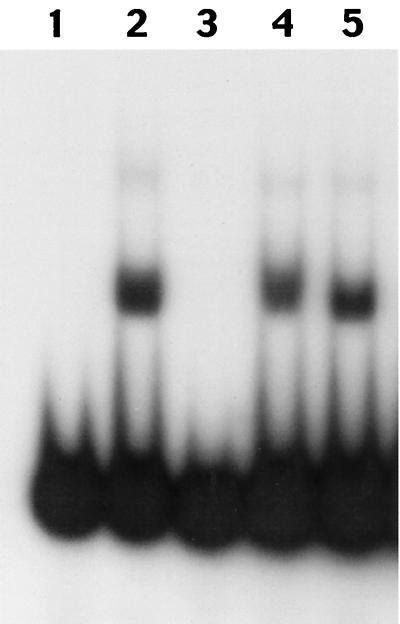

To confirm the production of Mph(A) directly and to identify the regulatory gene [mphR(A)] that controls the inducible expression of the mph(A) gene for Mph(A) in minicells, we recloned the inserts in pUC119 into pHSG399, in which the ampicillin resistance gene of pUC19 had been replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance gene, since the electrophoretic mobility of β-lactamase (32 kDa), which was generated from the ampicillin resistance gene on the pUC119 vector, was similar to that of Mph(A) (16). We introduced various derivatives of pHSG399 into minicell-producing E. coli and analyzed the radiolabeled products (Fig. 1). In the case of plasmid pTZ3517, which contained a 3.3-kb PstI-BamHI fragment that included the mph(A) and mrx genes, high-level production of Mph(A) was recognized when cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of EM (Fig. 1). However, in case of plasmid pTZ3510, which contained a 4.1-kb PstI fragment that consisted of 0.8 kb of the BamHI-PstI fragment that included the downstream region of the mrx gene and the above-mentioned 3.3-kb PstI-BamHI fragment, the level of Mph(A) produced in the absence of EM was lower than that produced in the presence of EM. This result indicated that the regulatory gene mphR(A) is located downstream from the mrx gene and that the expression of mph(A) is negatively regulated by mphR(A). However, no specific products encoded by mrx and mphR(A), respectively, were detected after autoradiography of the proteins produced in minicells. Furthermore, although the product of the mrx gene is required for expression of the high-level resistance to EM mediated by Mph(A), the production of Mph(A) in the minicells carrying pTZ3514, which included mrx with a nonsense mutation, was as enhanced in the presence of EM as that of the minicells carrying pTZ3510. This result indicated that mrx is not required for the inducible expression of mph(A).

FIG. 1.

Autoradiogram after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing plasmid-encoded proteins labeled with [14C]leucine that were produced in minicells. The autoradiograms show radioactive proteins synthesized in the absence of EM (− lanes) and in the presence of EM (+ lanes). The mobilities and molecular weights (in thousands) of standard proteins are indicated on the left. CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; Mph(A), macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I.

To determine whether inducible expression of the mph(A) gene requires the product of mphR(A), we performed a complementation analysis and assessed the induction of mph(A) by monitoring the inactivation of OL. When pSTV3509Δ361 carrying the mphR(A) gene was introduced into cells that harbored pTZ3519Δ318 carrying the mph(A) gene, an extract from the cells that had been cultured in the presence of EM inactivated OL more strongly than that from cells cultured in the absence of EM (data not shown). The complementation assay indicated that inducible expression of the mph(A) gene requires the product, MphR(A), of the mphR(A) gene.

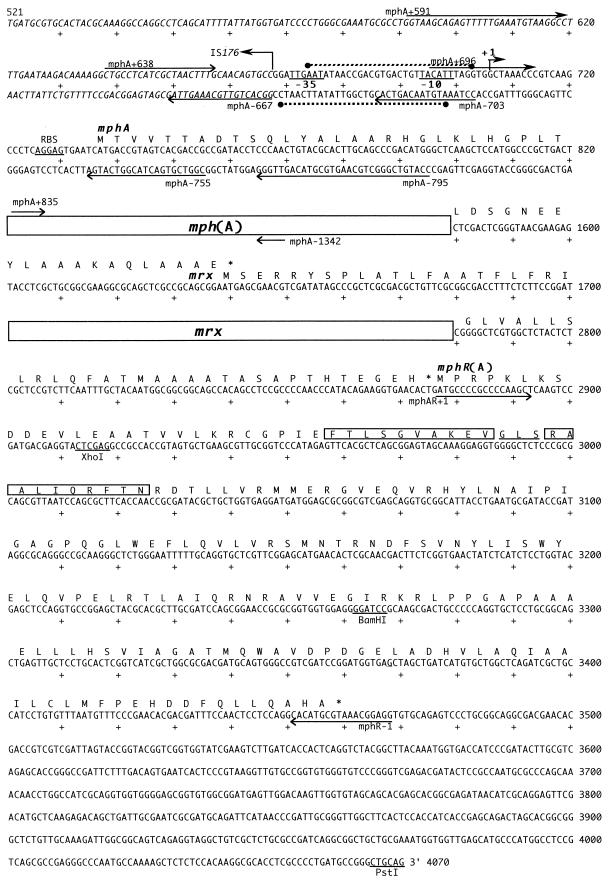

We determined the nucleotide sequence of the region (a 0.9-kb BamHI-PstI fragment) downstream of the mrx gene, and the sequence, including that of the mph(A) gene, is shown in Fig. 2. The region downstream of the mrx gene contains a single open reading frame that starts with the ATG initiation codon at nucleotide (nt) 2877. The open reading frame encodes a putative protein of 194 amino acids with a molecular weight of 21,627. The amino-terminal region of the putative protein includes an α-helix–turn–α-helix structure of the type conserved in DNA-binding proteins (21). The ATG initiation codon of the mrx gene overlaps the termination codon of mph(A) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the initiation codon of mphR(A) overlaps the termination codon of the mrx gene. Therefore, it is clear that mph(A), mrx, and mphR(A) are arranged in close proximity and form a gene cluster that begins with mph(A).

FIG. 2.

Structures of the mph(A), mrx, and mphR(A) genes. The nucleotide sequence from nt 521 to nt 4070 is shown. The −35 and −10 sequences that define the promoter and ribosome-binding site (RBS), as well as various restriction sites, are underlined. The arrows indicate the positions and directions of primers used in this study. The initiation transcription site and IS174 are indicated by hooked arrows. The binding site of MphR(A) is shown by a dotted line. The putative α-helices and turn in MphR(A) are boxed and underlined, respectively.

Repression of transcription of mph(A) by the MphR(A) protein.

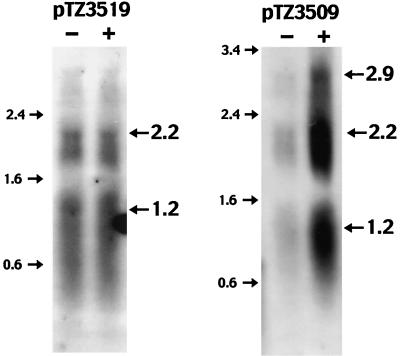

To determine whether the expression of the mph(A) gene is regulated at the transcriptional level, we analyzed the transcription of mph(A) by Northern blotting (Fig. 3). Although there was no difference in the transcript of mph(A) from pTZ3519 in the presence and in the absence of EM, as observed in our minicell experiment, the level of the transcripts from pTZ3509 was raised when cells were cultured with EM. Additionally, we found an mRNA of 2.9 kb among transcripts in cells that harbored pTZ3509 but not in those that harbored pTZ3519. The level of the 2.9-kb mRNA was markedly elevated in the presence of EM. Therefore, the expression of mph(A) was clearly regulated at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 3.

Northern blotting analysis of transcripts from E. coli cells harboring pTZ3519 and pTZ3509. Cells were grown in the absence of EM (− lanes) and in the presence of EM (+ lanes). The mobilities and sizes (kilobases) of standards are indicated on the left. Specific transcripts of interest are indicated on the right, along with their lengths in kilobases.

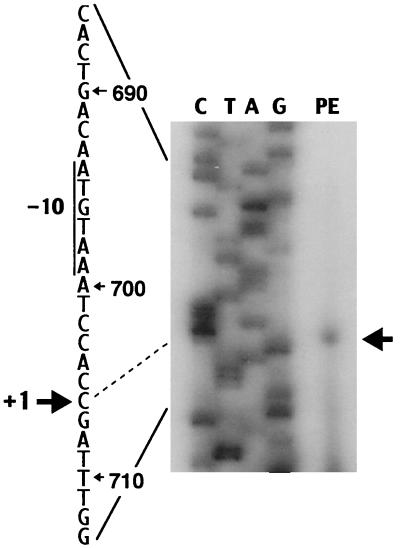

In order to identify the 5′ end of the transcript of mph(A), we performed primer extension analysis (Fig. 4). Total RNA was isolated from cells that harbored pTZ3509 and had been grown in the presence of EM. The resulting autoradiogram showed a single transcription initiation site that corresponds to G, at the RNA level, and is located 31 bp upstream from the translation initiation site of mph(A). The result was different from that obtained for the mph(K) gene, which is almost identical to the mph(A) gene (9, 22). Therefore, it appeared that the 2.9-kb mRNA was transcribed at least from the initiation site of the mph(A) gene to the 3′ terminus of the mphR(A) gene. Parts of the promoter sequence deduced from the primer extension experiment resembled the consensus sequences for the so-called −35 and −10 boxes, TTGAat and TAcAtT, respectively (where uppercase letters denote identity to the consensus sequences) (23). The distance between the putative −10 and −35 sequences was 17 nt. The results indicated that mrx and mphR(A) were transcribed from the promoter of the mph(A) gene by readthrough transcription. In the Northern blotting experiment with the cells that harbored pTZ3509, we detected two major mRNA bands of 1.2 and 2.2 kb, which correspond to transcripts of mph(A) and mph(A)-mrx, respectively, in addition to an mRNA band of 2.9 kb. We observed that levels of Mrx and MphR(A) were low in minicells, and no potential promoter with any homology to the consensus sequences of promoters in E. coli was found upstream of the mrx and mphR(A) genes. These observations suggest that the 1.2- and 2.2-kb mRNAs were generated during degradation of the 2.9-kb transcript in the cells that harbored pTZ3509. From these results, we concluded that this inducible macrolide resistance determinant consists of a gene cluster, mph(A)-mrx-mphR(A), designated the mphA operon.

FIG. 4.

Mapping of the transcription initiation site of mph(A). Size markers (lanes G, A, T, and C) were generated in sequencing reactions performed with pTZ3519 DNA. The arrow on the right indicates the product of the extension reaction (PE).

Specific binding of MphR(A) to the promoter region of mph(A).

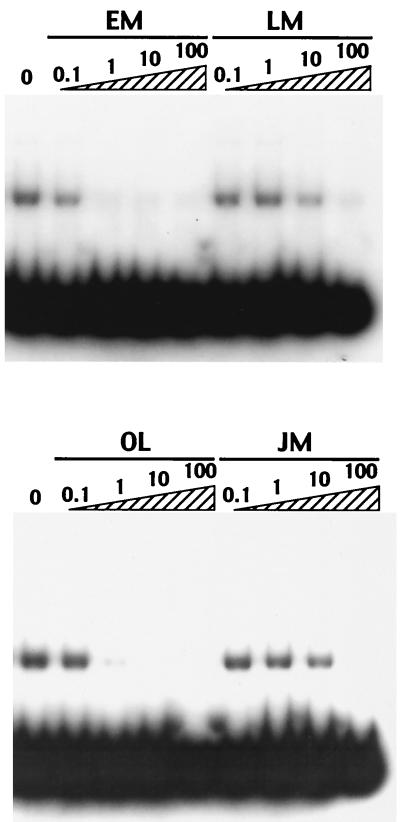

An analysis of the putative product of the mphR(A) gene revealed that the first 64 amino acids of MphR(A) exhibit strong homology to proteins in the TetR/AcrR family. The proteins in this family bind in the vicinity of the promoters of their respective target genes (8, 14). To examine whether MphR(A) is the repressor protein that controls expression of mph(A), we constructed an mphR(A) expression system and purified MphR(A). We performed gel mobility shift assays using the purified protein and a 66-bp fragment (DNA-1) that includes the promoter sequence of mph(A). As shown in Fig. 5, the mobility of the DNA-1 fragment was shifted in the presence of MphR(A). To analyze the binding specificity of MphR(A) in further detail, we performed a competition experiment. The shifted DNA band was almost completely abolished when the unlabeled DNA-1 fragment was added as a competitor to the reaction mixture before addition of the labeled DNA. By contrast, an excess of individual nonspecific competitors that included regions either upstream (DNA-2) or downstream (DNA-3) from the promoter of mph(A), as well as an excess of poly(dI-dC), had no effect on the binding of MphR(A) to radiolabeled DNA-1. These results indicated that MphR(A) bound specifically to the promoter region of mph(A).

FIG. 5.

Gel mobility shift assay with the promoter region of the mph(A) gene. A 66-bp fragment (DNA-1) including the promoter of the mph(A) gene was amplified with end-labeled primers mphA+638 and mphA−667 (see Materials and Methods) and used as the probe. Reaction mixtures contained no MphR(A) protein (lane 1); no competitor (lane 2); unlabeled competitor DNA-1 (lane 3); the DNA-2 fragment, amplified with primers mphA+591 and mphA−667 (lane 4); and the DNA-3 fragment, amplified with primers mphA+638 and mphA−703 (lane 5).

Identification of the MphR(A) binding site.

DNA-binding proteins often bind sequences displaying dyad symmetry. However, no repeated sequence was present in the region of the promoter of the mph(A) gene. We identified the exact location of the binding site of MphR(A) in a DNase I footprinting experiment with purified MphR(A) and an end-labeled 165-bp DNA fragment that included the promoter region of mph(A). Relative to the transcription initiation site of mph(A), the region protected by MphR(A) extended from nt −32 (674 nt) to nt −3 (703 nt) on the coding strand and from nt −37 (669 nt) to nt −9 (698 nt) on the noncoding strand (Fig. 6). Thus, the protected region (from nt −37 to nt −3) on the two strands corresponds exactly to the promoter region of the mph(A) gene. These results indicated that MphR(A) represses the initiation of transcription of the mphA operon by blocking the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter of the mph(A) gene.

FIG. 6.

DNase I footprinting analysis of protection by MphR(A) of the promoter region of mph(A). (A) Footprinting analysis of the coding strand. (B) Footprinting analysis of the noncoding strand. G+A indicates patterns of Maxam-Gilbert chemical cleavage reactions. Lanes 0 through 50 indicate digestion with DNase I of DNA in reaction mixtures that contained increasing concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter) of DNase I. The thick vertical lines delineate regions protected by MphR(A). The transcription initiation site and the promoter region (−10 and −35) are also indicated. The values to the right are lengths in kilobases.

Effects of macrolides on binding of MphR(A) to the promoter.

In the presence of a subinhibitory concentration of EM, namely, 25 μg/ml (19), the rate of transcription of mph(A) is elevated. To determine whether macrolides can directly inhibit the binding of MphR(A) to the promoter of mph(A) and to identify the kinds of macrolide that can act as inducers, we performed gel mobility shift assays using a variety of macrolides at various concentrations. Included were EM and OL as representative 14-member ring macrolides and kitasamycin and josamycin as representative 16-member ring macrolides. Each macrolide in the reaction mixture abolished the binding of purified MphR(A) to the promoter fragment as the concentration of the macrolide was increased. However, the concentration at which 14-member ring macrolides inhibited the binding of MphR(A) to the DNA was 100-fold lower than at which 16-member ring macrolides inhibited such binding (Fig. 7). This result is supported by the profiles of inactivation of macrolides by Mph(A) and the pattern of susceptibility to macrolides of E. coli that carried the mphA operon. Although the inhibition of the binding of MphR(A) to the DNA by EM was slightly stronger than that of OL, we found no difference in the ability to induce mph(A) in the presence of EM and OL by monitoring the inactivation of OL (data not shown). These results indicated that 14-member ring macrolides are the inducers of the mphA operon and directly inhibited the binding of MphR(A) to the promoter of the mph(A) gene.

FIG. 7.

Gel mobility shift assays showing the binding of MphR(A) to the promoter region of mph(A) in the presence of various macrolides. Lanes 0 through 100 contained increasing concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter) of macrolides. LM, kitasamycin; JM, josamycin.

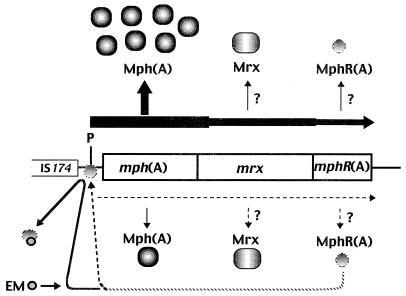

A model for regulation of expression of the mphA operon.

Based on our results, a model of the inducible expression of the macrolide resistance determinant mphA is presented in Fig. 8. Thus, the mechanism of inducible expression of the mphA determinant is entirely different from that of the typical macrolide resistance determinant ermC.

FIG. 8.

A model for regulation of the expression of the mph(A) operon in E. coli. P represents the promoter of the mph(A) gene. Induced and uninduced expression is indicated by dotted and solid lines, respectively. The mph(A) gene encodes the repressor protein MphR(A) and the macrolide resistance determinant consisted of the mphA operon, which is made up of the mph(A), mrx, and mph(A) genes. The expression of the mphA operon is negatively regulated at the transcriptional level by the binding of MphR(A) to the promoter of the mph(A) gene. In the presence of a subinhibitory concentration of a 14-member ring macrolide, transcription of the mphA operon is activated by blockage of the binding of MphR(A) to the mph(A) promoter.

This conclusion predicts that the production of the Mrx and MphR(A) proteins in E. coli with an mphA operon should be enhanced in the presence of EM. Since we failed to detect proteins with molecular weights of approximately 41,000 and 22,000 that might have been encoded by mrx and mphR(A), respectively, in minicell experiments (Fig. 1), it was not clear whether levels of Mrx and MphR(A) might be enhanced in the presence of EM. However, the increase in the level of the 2.9-kb transcript upon addition of EM to the culture medium indicated that the transcription of the mph(A)-mrx-mphR(A) cluster was regulated by MphR(A). Therefore, it appears that MphR(A) negatively autoregulates the transcription of its own gene.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Horii, Y. Fujii, M. Suzuki, and A. Sato for their skilled technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant for private universities from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan, and by a grant from the Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Autissier D, Courvalin P. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the ereB gene encoding the erythromycin esterase type II. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4987–4999. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.12.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur M, Courvalin P. Contribution of two different mechanisms to erythromycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:694–700. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galas D J, Schmitz A. DNase footprinting: a simple method for the detection of protein-DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:3157–3170. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grodberg J, Dunn J J. OmpT encodes the Escherichia coli outer membrane protease that cleaves T7 RNA polymerase during purification. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1245–1253. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1245-1253.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guay D R P. Macrolide antibiotics in paediatric infection diseases. Drugs. 1996;51:515–536. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennighausen L, Lubon H. Interaction of protein with DNA in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:721–735. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillen W, Klock G, Kaffenberger I, Wray L V, Reznikoff W S. Purification of the TET repressor and TET operator from the transposon Tn10 and characterization of their interaction. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6605–6613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S-K, Baek M-C, Choi S-S, Kim B-K, Choi E-C. Nucleotide sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the Escherichia coli mphK gene encoding macrolide-phosphotransferase K. Mol Cells. 1996;6:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kono M, O'Hara K, Ebisu T. Purification and characterization of macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase type II from a strain of Escherichia coli highly resistant to macrolide antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;97:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labro M T. Anti-inflammatory activity of macrolides: a new therapeutic potential? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(Suppl. B):37–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Intrinsic and unusual resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics in bacteria. Anitmicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1273–1276. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma D, Alberti M, Lynch C, Nikaido H, Hearst J E. The local repressor AcrR plays a modulating role in the regulation of acrAB genes of Escherichia coli by global stress signals. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:101–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.357881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noguchi N, Emura A, Matsuyama H, O'Hara K, Sasatsu M, Kono M. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of erythromycin resistance determinant that encodes macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2359–2363. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noguchi N, Katayama J, O'Hara K. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the mphB gene for macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase II in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noguchi N, Tamura Y, Katayama J, Narui K. Expression of the mphB gene for macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase II from Escherichia coli in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;159:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Hara K, Kanda T, Ohmiya K, Ebisu T, Kono M. Purification and characterization of macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase from a strain of Escherichia coli that is highly resistant to erythromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1354–1357. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ounissi H, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence of the gene ereA encoding the erythromycin esterase in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1985;35:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pabo C O. Protein-DNA recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:293–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts M C, Sutcliffe J, Courvalin P, Jensen L B, Rood J, Seppala H. Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg M, Court D. Regulatory sequences involved in the promotion and termination of RNA transcription. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:319–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross J I, Eady E A, Cove J H, Cunliffe W J, Baumberg S, Wootton J C. Inducible erythromycin resistance in staphylococci is encoded by a member of the ATP-binding transport super-gene family. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1207–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakakibara Y. dnaR function of the prs gene of Escherichia coli in initiation of chromosome replication. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:989–996. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91047-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Goto T. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene. 1987;61:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisblum B. Insight into erthromycin action from studies of its activity as inducer of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:797–805. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams J D, Sefton A M. Comparison of macrolide antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl. C):11–26. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_c.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]