Summary

Background

Overweight and obesity is a growing public health issue as it contributes to the future burden of obesity-related diseases, including cancer, especially in high-income countries. In Australia, 4.3% of all cancers diagnosed in 2013 were attributable to overweight and obesity. Our aim was to examine Australian age-specific incidence trends over the last 35 years for obesity-related cancers based on expert review (colorectal, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, breast in postmenopausal women, uterine, ovary, kidney, thyroid, and multiple myeloma) individually and pooled.

Methods

Australian incidence data for 10 obesity-related cancers among people aged 25–84 years, diagnosed from 1983 to 2017, were obtained from the Australian Cancer Database. We used age–period–cohort modelling and joinpoint analysis to assess trends, estimating incidence rate ratios (IRR) by birth-cohort for each individual cancer and pooled, and the annual percentage change. The analyses were also conducted for non-obesity-related cancers over the same period.

Findings

The total number of cancers where some proportion is obesity-related, diagnosed from 1983-2017, was 1,005,933. This grouping was 34.7% of cancers diagnosed. The IRR of obesity-related cancers increased from 0.77 (95% CI 0.73, 0.81) for the 1903 birth-cohort to 2.95 (95% CI 2.58, 3.38) for the recent 1988 cohort relative to the 1943 cohort. The IRRs of non-obesity related cancers were stable with non-significant decreases in younger cohorts. These trends were broadly similar across sex and age groups.

Interpretation

The incidence of obesity-related cancers in Australia has increased by birth-cohort across all age-groups, which should be monitored. Obesity, a public health epidemic, needs to be addressed through increased awareness, policy support and evidence-based interventions.

Funding

This research received no specific funding.

Keywords: Cancer, Obesity, Overweight, Age–period–cohort, Incidence

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Emerging evidence from the United States indicated that the incidence of some obesity-related cancers has increased in young adults (25–49 years) with steeper rises in successively recent birth cohorts, using age-period-cohort modelling. We searched PubMed for articles published between 1 March 2019 and 14 January 2022, using terms “obesity” AND “cancer” AND “birth cohort”, and “modelling” OR “analysis” to identify further evidence. Our search was not restricted by language or type of publication. Most high-income countries are experiencing an ‘obesity epidemic’, with rising rates of overweight and obesity experienced in both children and adults. This shift may be a result in changing lifestyles due to increased sedentary behaviours including increased technology use and desk-based jobs, changes in the food supply including availability, pricing and promotion of less healthy foods, and a lack of population-wide policies regarding physical activity and healthy eating. A result of this obesity-shift is an increasing chronic disease burden. Despite growing awareness, there are few studies to inform policy makers of the growing incidence of potentially preventable cancers where some proportion of the burden can be attributed to overweight and obesity.

Added value of this study

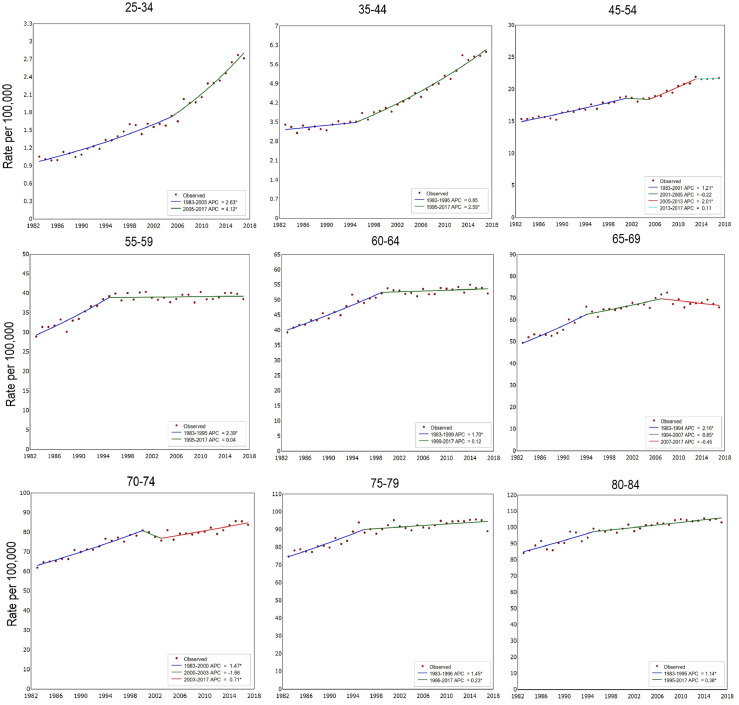

We studied cancer incidence data from the Australian Cancer Database to examine individual and pooled incidence trends for 10 obesity-related cancers over a 35-year period, which included 1,005,933 diagnoses. We used age–period–cohort modelling to assess trends, estimating incidence rate ratios by birth-cohort for each individual cancer and pooled together. We also assess the annual percentage change (APC) using joinpoint analysis. We found that the pooled IRR of obesity-related cancers increased from 0.77 (95% CI 0.73, 0.81) for the 1903 birth-cohort to 2.95 (95% CI: 2.58–3.38) for the youngest cohort. The APC showed a consistent increase in incidence by age group across the time periods with the greatest increase by 4.1 in 25–34 year olds from 2005–2017 (4.1 95% CI: 3.4–4.8).

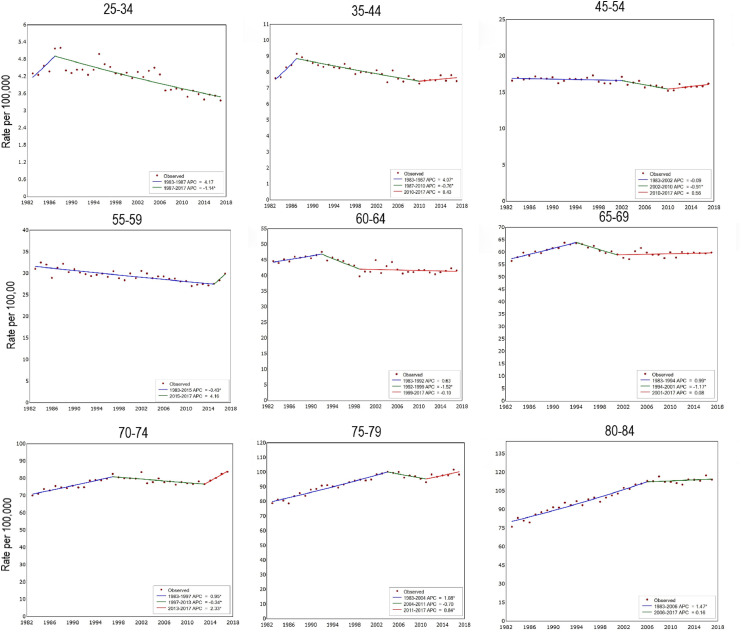

There was a small increase in non-obesity related cancers over the same time period, though to a lesser extent than obesity-related cancers and not statistically significant in the more recent cohorts, with an IRR of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.55–0.74) for the 1903 birth cohort to 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89–0.98) for the 1943 birth cohort and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.62–1.17) for the youngest birth cohort (1988). The APC showed a decrease in incidence for all age groups from 25–69 as well as 80–84 in the most recent time period. There was, however, an APC of 2.5% per annum (95% CI 0.5–4.7) for those aged 70–74 from 2014–2017 and 1.3% per annum (95% CI 0.9–1.8) in 1997–2008 for those 75–79.

Our study was also able to assess these trends by sex and age-group. Obesity-related cancers in males increased steadily for the 1953 birth cohort through to the youngest cohort. For non-obesity related cancers, the IRR increased from the same cohort, reaching a high of 1.23 (95% CI 1.08–1.41) for the 1968 birth cohort to a non-significant IRR of 0.96 (95% CI 0.58–1.59) in the youngest cohort. This was largely driven by the rising incidence of prostate cancer from the 1990s. In females, there was an increase in obesity-related cancers from the 1958 birth cohort to the youngest cohort (IRR 1.05 vs 2.61). Conversely the IRR for non-obesity related cancers in women decreased consistently from the 1953 birth cohort to the youngest birth cohort (IRR 0.97 vs 0.68).

Across age groups, the APC showed a decrease in the incidence of non-obesity-related cancers with the exception of those ages 70–79 where incidence increased in the most recent time period. In males, obesity-related cancer incidence increased by age group except for males aged 65–79 where incidence decreased. This was similar in females with a small decrease found in females aged 35–44. For non-obesity-related cancers, there was a small decrease in incidence which decreased in male ages 35–69 in the most recent time period but in older males incidence generally increased. In females, those aged 25–44 had decreasing incidence of non-obesity-related cancers whereas females aged 55–84 had increased incidence through to the 2000s.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings suggest that the incidence of obesity-related cancers in Australia is increasing by birth-cohort across age groups and by sex. These data provide novel evidence that this concerning trend requires monitoring in Australia and in other countries that are also experiencing increasing obesity trends. Obesity, a public health epidemic in high-income countries, needs to be addressed through a combined effort of increased awareness, policy support and evidence-based interventions from childhood and into adulthood.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

The rising burden of overweight and obesity has generated growing concern, especially in high-income countries, as it contributes to the current and future burden of obesity-related diseases.1,2 Internationally, governments are under increasing pressure to take action to combat the “obesity epidemic”.3,4 The link between overweight and obesity with cancer is well established across numerous cancer sites5,6 with an estimated 3.9% of all new cancer cases attributed to overweight and obesity globally.7 Emerging evidence from the United States,8,9 Canada,10 and the United Kingdom11 identified increasing incidence of some obesity-related cancers (multiple myeloma, colorectal, uterine, gallbladder, kidney, and pancreatic cancer) in young adults, with steeper rises in successively recent birth cohorts. Cancer trends in recent birth cohorts can have lasting effects on disease burden. This is becoming problematic in high-income countries where there has been a higher incidence of cancer diagnoses among recent birth cohorts compared to developing countries.12

Australia is an example of a high-income country with increasing rates of overweight and obesity. The 2017/18 National Health Survey found that 67% of Australians 18 years and over were considered overweight (35.6%) or obese (31.3%), with the obesity prevalence increasing substantially from 19% in 1995,13 and projected to increase further to 38% by 2030.14 Males (74.5%) had a higher rate of overweight and obesity than females (59.7%), with the highest prevalence among males being between ages 45–74 and 65–84 for females.15 A recent study assessing the age-period-cohort effect of obesity, physical inactivity and smoking in Australia found the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased with age until 64 and then decreased, with increasing shifts in overweight, obesity and physical inactivity trends in more recent time-periods and younger birth cohorts.16 The increasing trend in obesity patterns is evident among younger generations who are predicted to have higher obesity levels when they reach middle-age compared to older generations.17 An Australian burden of disease study found that overweight and obesity contributed to 8.4% of all disease burden, second only to tobacco smoking (8.6%), highlighting the growing burden of obesity-related diseases.18

In Australia, there were an estimated 5,371 cancer cases (4.3% of all cancers) diagnosed in 2013 attributable to overweight and obesity.19 Oesophageal adenocarcinoma, endometrial cancer and kidney cancer accounted for cancers in Australia with the highest proportion of diagnoses in 2010 that were causally associated with overweight and obesity, accounting for 31.4%, 26.4% and 19.1% of all diagnoses, respectively.20 The population attributable fraction (PAF) for other overweight and obesity cancers were 14.2 for gallbladder cancer, 7.8 for pancreatic and postmenopausal breast cancer and 3.6 for ovarian cancer.20 Colorectal cancer, with a PAF of 10.1 for colon cancer and 5.8 for rectal cancer,20 also has increasing incidence in people under the age of 50 in Australia, which could be partially attributed to the changing prevalence of overweight and obesity21 and may be enhanced by inadequate lifestyles including poor diet and physical inactivity. As obesity prevalence increases in Australia with a birth cohort effect,16 a more thorough assessment of obesity-related cancers by age and time-period is warranted. Our aim was to examine age-specific incidence trends in Australia over the last 35 years for 10 obesity-related cancers based on expert review (colorectal, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, breast in postmenopausal women, uterine, ovary, kidney, thyroid, and multiple myeloma) pooled together, and each cancer type individually.

Methods

Study population

Cancer is a notifiable disease across Australia.22 We obtained incidence data for cancers among people aged 25–84 years, diagnosed from 1983 to 2017, from the Australian Cancer Database.22 The age range for this analysis was limited due to the small case numbers in people aged under 25 years and the open-ended age categorisation for the 85 years or over. Australian cancer incidence data have high standards of completeness and quality, cover all jurisdictions in the country and are included by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in Cancer Incidence in Five Continents.23,24 The 10 cancer types included in this study are based on their association with obesity according to expert reviews:5,6 colorectal, liver (hepatocellular carcinoma), gallbladder, pancreas, breast in postmenopausal women, uterine, ovary, kidney (renal cell carcinoma), and thyroid, as well as multiple myeloma. We included data for all histological types combined for cancers of the liver and kidney as incidence data by subtypes are not available in Australian Cancer Database.23 We excluded data on cancers of the oesophagus, stomach and breast under age 50 as evidence is only sufficient for subgroups of these cancer types, namely adenocarcinoma of oesophagus, gastric cardia, and postmenopausal women with breast cancer.23 To enable a comparison, we also analysed non-obesity related cancers (lung, melanoma of the skin, cervix, prostate, testis, bladder, brain, cancer of unknown primary, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, other cancers of the blood & lymphatic system, and myelodysplastic syndromes).25 These were chosen as they represent the most common non-obesity-related cancer types based on incidence data from the Australian Cancer Database in 2021.25 As these tabulated data are publicly accessible, ethics approval was not required. The STROBE guidelines for observational research were followed in the reporting of this study (Supplementary File 1).

Age, diagnosis period, and birth cohorts

Age group at cancer diagnosis was categorised into five-year intervals from 25–29 years to 80–84 years. Period of diagnosis was categorised into five-year intervals from 1983–1987 to 2013–2017. A total of 18 partly overlapping 10-year birth cohorts were constructed by subtracting the midyears of age from the midyears of diagnosis, referenced by mid-year of birth (from 1899–1908 [1903 cohort] to 1984–93 [1988 cohort]).

Statistical analysis

Joinpoint analysis: Annual incidence rates from 1983 to 2017 were estimated for 9 age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84), with 10-year age groups used for those under 55 years of age given lower incidence. The joinpoint analysis was done separately by sex for obesity-related cancers and non-obesity related cancers, along with individual cancers of colorectal cancer and postmenopausal women with breast cancer (those with sufficient case numbers). Joinpoint regression analysis, a commonly used technique to discern temporal trends in cancer incidence, was used to identify the points of change in direction and estimate the magnitude of change in rates.26 SEER*Stat (version 4.7.0) was used.

Age-period-cohort modelling: Age-period-cohort models are well-developed approaches to study temporal trends in disease rates.27 The trends based on calendar period reflect changes in exposures affecting the whole population during a particular period, while trends according to birth cohort reflect variation in risk factors among people born during different eras. In this study, we used age-period-cohort modelling to assess trends, adapting analysis code provided with a previously published age-period-cohort analysis tool28 from the US National Cancer Institute (https://github.com/CBIIT/nci-webtools-dceg-age-period-cohort/blob/master/apc/apc.R, accessed 14 January 2019). To compare incidence rates by birth cohort, we estimated incidence rate ratios (IRR) by birth cohort and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI), with the 1948 cohort as the referent group. This was done separately for men and women. We chose 1948 as referent birth cohort as it is midway between the examined cohorts. To examine whether these models provide an adequate description of the data, we calculated the average absolute relative bias (difference between observed and predicted rates) for each age group across all periods.

In a sensitivity analysis, we replicated the analysis of incidence by birth cohort for 12 obesity-related cancers, that is including data for oesophagus, stomach and women <50 years for breast cancer.

Role of the funding source

This research received no specific grant funding with no role of the funding source in this work.

Results

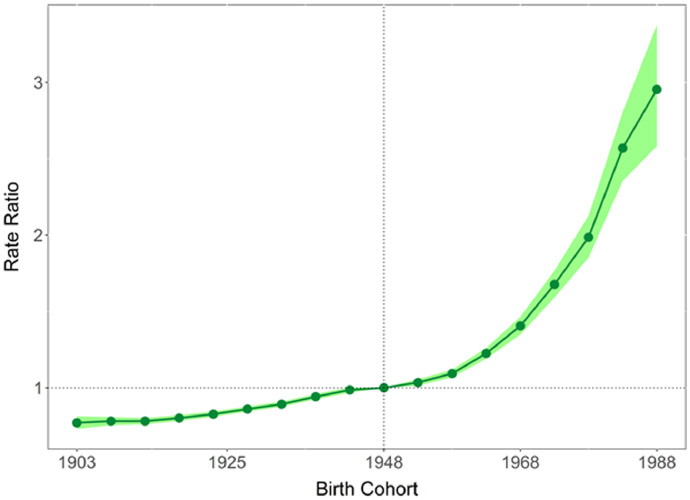

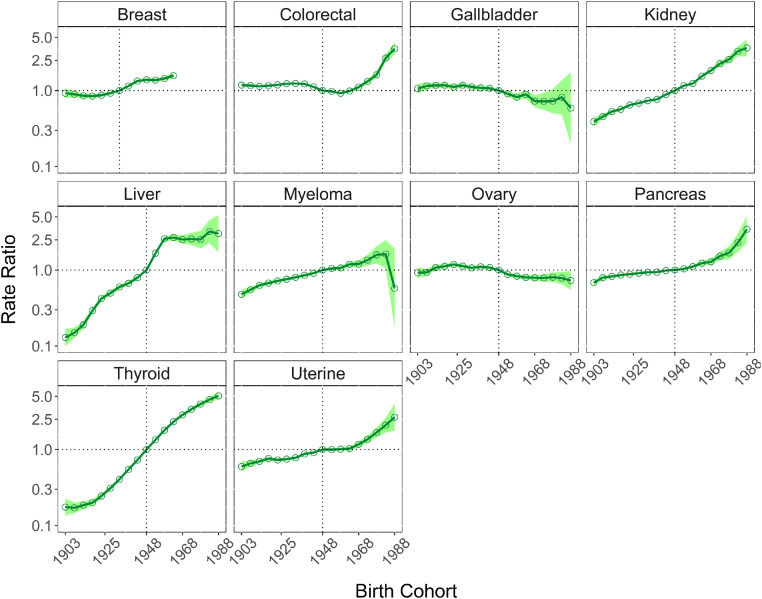

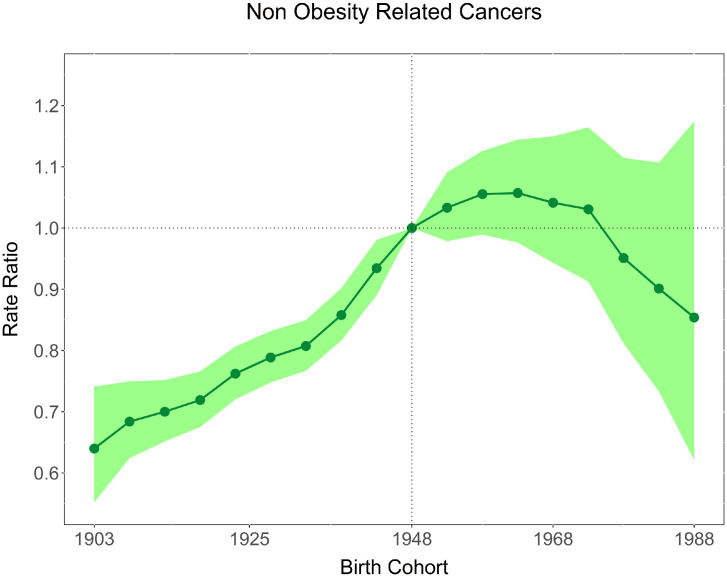

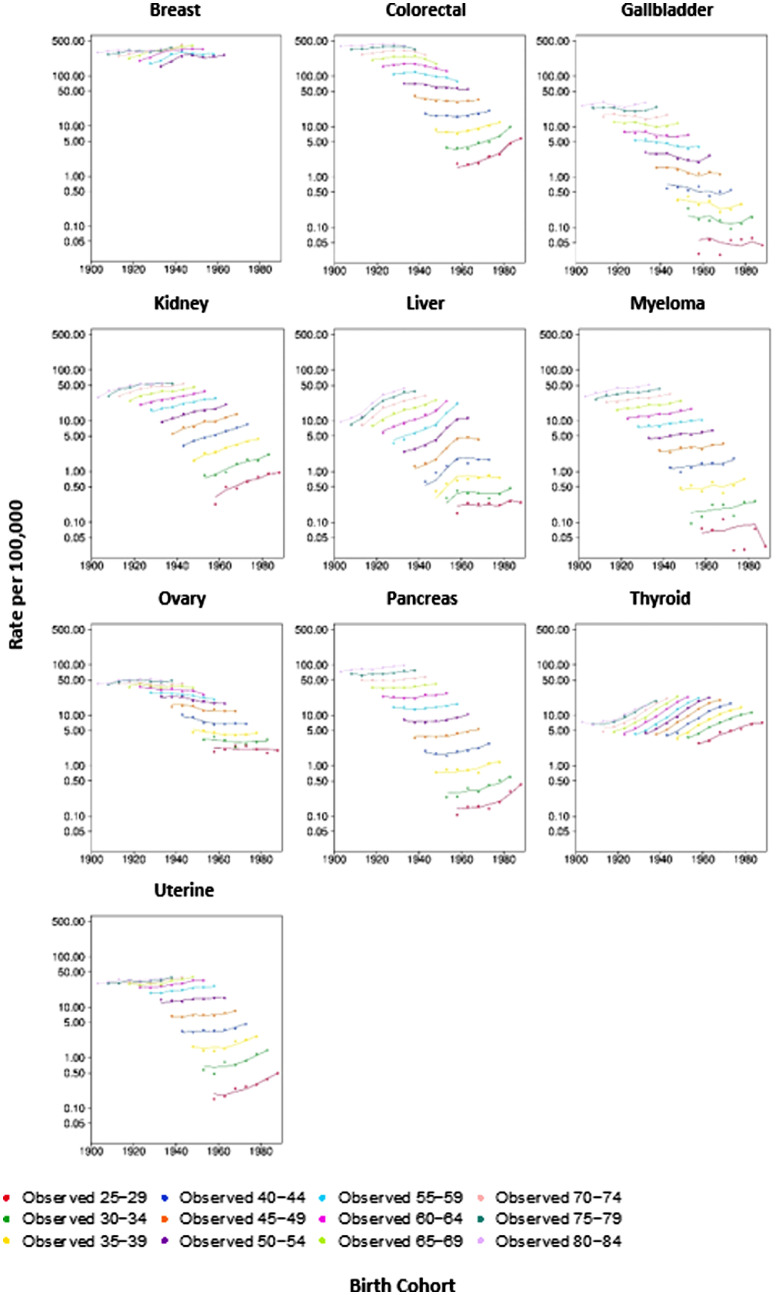

Between 1983 and 2017, 1,005,933 Australian adults aged 25 to 84 years were diagnosed with a cancer related to obesity. This grouping represents 34.7% of all cancers diagnosed over this period. The IRRs by birth cohort for obesity-related cancers overall and individual cancer sites are presented in Table 1, Figures 1 and 2. The IRR of obesity-related cancers increased over time with the 1903 birth cohorts showing an IRR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.73–0.81), increasing to 2.95 (95% CI 2.58–3.38) for the 1988 birth cohort, the youngest cohort. Figure 1 illustrates the gradual increase over time. Figure 3 shows that for non-obesity related cancers, there was a small increase over the same time period, though to a lesser extent than obesity-related cancers and not statistically significant in younger cohorts, with an IRR of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.55–0.74) for the 1903 birth cohort to 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89–0.98) for 1943 birth cohort to 0.85 (95% CI: 0.62–1.17) for the most recent birth cohort (1988) (Table 1). The trends by individual obesity-related cancer type show increasing incidence in successively recent birth cohorts for eight cancers, with three of the highest increases being for cancers of thyroid, kidney and colorectal (IRR estimates for the most recent birth cohort 5.08 [95% CI 4.56–5.66], 3.64 [95% CI 2.81–4.70], and 3.65 [95% CI 2.96–4.28], respectively). Conversely, the IRRs indicated a decrease for recent birth cohorts for cancers of the gallbladder, and ovary (with e.g. IRR estimates for the most recent cohort 0.59 [95% CI 0.20–1.74], 0.73 [95% CI 0.55–0.96], respectively). Figure 4 illustrates the age-specific incidence by birth cohort illustrating that older birth cohorts are less affected over time compared to the younger cohorts for cancers of the colorectum, kidney, uterus and pancreas. Exceptions to this were seen for liver and thyroid cancers.

Table 1.

Incidence Rate Ratios by birth cohort for obesity-related cancers (ORC) diagnosed in 1983–2017 Australia.

| Birth Cohort | All ORC* | All Non ORC | Colorectal | Liver | Gall Bladder | Pancreatic | Breast ≥ 50 years | Uterine | Ovarian | Kidney | Thyroid | Multiple Myeloma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 0.77 [0.73, 0.81] | 0.64 [0.55, 0.74] | 1.18 [1.11, 1.26] | 0.13 [0.10, 0.17] | 1.06 [0.91, 1.23] | 0.68 [0.63, 0.75] | 0.92 [0.80, 1.07] | 0.60 [0.51, 0.69] | 0.92 [0.78, 1.09] | 0.39 [0.34, 0.44] | 0.17 [0.14, 0.23] | 0.48 [0.42, 0.55] |

| 1908 | 0.78 [0.75, 0.81] | 0.68 [0.62, 0.75] | 1.16 [1.12, 1.21] | 0.15 [0.13, 0.17] | 1.15 [1.04, 1.27] | 0.79 [0.75, 0.84] | 0.89 [0.81, 0.98] | 0.66 [0.60, 0.72] | 0.93 [0.84, 1.03] | 0.46 [0.42, 0.49] | 0.17 [0.15, 0.20] | 0.55 [0.51, 0.60] |

| 1913 | 0.78 [0.76, 0.80] | 0.70 [0.65, 0.75] | 1.13 [1.10, 1.17] | 0.19 [0.17, 0.21] | 1.17 [1.08, 1.27] | 0.82 [0.78, 0.86] | 0.85 [0.80, 0.91] | 0.70 [0.65, 0.75] | 1.08 [1.00, 1.17] | 0.53 [0.50, 0.56] | 0.19 [0.17, 0.21] | 0.63 [0.59, 0.67] |

| 1918 | 0.80 [0.78, 0.82] | 0.72 [0.68, 0.77] | 1.16 [1.12, 1.19] | 0.29 [0.27, 0.32] | 1.17 [1.09, 1.27] | 0.86 [0.82, 0.90] | 0.85 [0.80, 0.90] | 0.76 [0.72, 0.80] | 1.12 [1.05, 1.20] | 0.57 [0.54, 0.59] | 0.20 [0.18, 0.22] | 0.67 [0.64, 0.72] |

| 1923 | 0.83 [0.81, 0.84] | 0.76 [0.72, 0.81] | 1.19 [1.16, 1.22] | 0.42 [0.39, 0.45] | 1.11 [1.04, 1.20] | 0.88 [0.85, 0.92] | 0.87 [0.82, 0.91] | 0.73 [0.70, 0.76] | 1.18 [1.12, 1.26] | 0.65 [0.62, 0.67] | 0.24 [0.23, 0.26] | 0.72 [0.68, 0.76] |

| 1928 | 0.86 [0.84, 0.88] | 0.79 [0.75, 0.83] | 1.23 [1.20, 1.26] | 0.50 [0.46, 0.53] | 1.17 [1.09, 1.26] | 0.91 [0.87, 0.94] | 0.92 [0.88, 0.97] | 0.75 [0.72, 0.78] | 1.13 [1.06, 1.19] | 0.68 [0.66, 0.71] | 0.31 [0.29, 0.33] | 0.76 [0.72, 0.80] |

| 1933 | 0.89 [0.88, 0.91] | 0.81 [0.77, 0.85] | 1.24 [1.21, 1.27] | 0.60 [0.56, 0.64] | 1.12 [1.04, 1.19] | 0.94 [0.90, 0.97] | 1 [1, 1] | 0.78 [0.75, 0.81] | 1.07 [1.01, 1.13] | 0.74 [0.71, 0.76] | 0.41 [0.38, 0.43] | 0.80 [0.76, 0.84] |

| 1938 | 0.94 [0.92, 0.96] | 0.86 [0.82, 0.90] | 1.22 [1.19, 1.25] | 0.67 [0.63, 0.71] | 1.08 [1.01, 1.16] | 0.94 [0.90, 0.97] | 1.15 [1.10, 1.20] | 0.87 [0.84, 0.91] | 1.10 [1.05, 1.16] | 0.77 [0.74, 0.79] | 0.55 [0.52, 0.57] | 0.85 [0.81, 0.89] |

| 1943 | 0.99 [0.97, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.89, 0.98] | 1.12 [1.09, 1.15] | 0.79 [0.75, 0.84] | 1.07 [1.00, 1.15] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.02] | 1.34 [1.28, 1.40] | 0.91 [0.88, 0.95] | 1.08 [1.02, 1.13] | 0.89 [0.86, 0.91] | 0.73 [0.69, 0.76] | 0.91 [0.87, 0.95] |

| 1948 | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1.39 [1.32, 1.45] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 1] |

| 1953 | 1.03 [1.01, 1.06] | 1.03 [0.98, 1.09] | 0.98 [0.95, 1.00] | 1.66 [1.57, 1.77] | 0.91 [0.83, 0.98] | 1.04 [1.00, 1.08] | 1.37 [1.30, 1.44] | 1.00 [0.96, 1.04] | 0.87 [0.83, 0.92] | 1.16 [1.12, 1.20] | 1.34 [1.29, 1.40] | 1.05 [0.99, 1.10] |

| 1958 | 1.09 [1.07, 1.12] | 1.06 [0.99, 1.13] | 0.92 [0.89, 0.96] | 2.59 [2.41, 2.77] | 0.82 [0.74, 0.90] | 1.11 [1.05, 1.17] | 1.44 [1.36, 1.53] | 1.01 [0.97, 1.06] | 0.83 [0.78, 0.88] | 1.24 [1.19, 1.29] | 1.80 [1.72, 1.88] | 1.07 [1.00, 1.14] |

| 1963 | 1.23 [1.19, 1.26] | 1.06 [0.98, 1.14] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.03] | 2.68 [2.45, 2.93] | 0.89 [0.79, 1.01] | 1.23 [1.15, 1.32] | 1.57 [1.45, 1.70] | 1.03 [0.97, 1.09] | 0.80 [0.74, 0.86] | 1.55 [1.48, 1.62] | 2.32 [2.22, 2.43] | 1.19 [1.10, 1.29] |

| 1968 | 1.41 [1.35, 1.46] | 1.04 [0.94, 1.15] | 1.11 [1.05, 1.17] | 2.53 [2.23, 2.87] | 0.72 [0.60, 0.87] | 1.28 [1.17, 1.41] | 1.17 [1.08, 1.27] | 0.79 [0.72, 0.86] | 1.84 [1.73, 1.95] | 2.86 [2.72, 3.01] | 1.20 [1.07, 1.34] | |

| 1973 | 1.68 [1.59, 1.77] | 1.03 [0.91, 1.16] | 1.32 [1.23, 1.42] | 2.57 [2.14, 3.07] | 0.72 [0.56, 0.93] | 1.53 [1.35, 1.73] | 1.37 [1.23, 1.52] | 0.79 [0.70, 0.88] | 2.26 [2.09, 2.43] | 3.39 [3.20, 3.59] | 1.35 [1.15, 1.59] | |

| 1978 | 1.99 [1.85, 2.13] | 0.95 [0.81, 1.11] | 1.61 [1.46, 1.78] | 2.52 [1.93, 3.28] | 0.72 [0.50, 1.05] | 1.68 [1.39, 2.04] | 1.68 [1.44, 1.95] | 0.81 [0.70, 0.93] | 2.55 [2.29, 2.84] | 3.96 [3.71, 4.23] | 1.58 [1.22, 2.05] | |

| 1983 | 2.57 [2.35, 2.80] | 0.90 [0.73, 1.11] | 2.68 [2.37, 3.02] | 3.22 [2.28, 4.54] | 0.82 [0.49, 1.37] | 2.29 [1.74, 3.01] | 2.09 [1.68, 2.61] | 0.78 [0.65, 0.94] | 3.29 [2.83, 3.83] | 4.54 [4.20, 4.91] | 1.62 [1.06, 2.48] | |

| 1988 | 2.95 [2.58. 3.38] | 0.85 [0.62, 1.17] | 3.65 [2.96, 4.28] | 3.02 [1.72, 5.29] | 0.59 [0.20, 1.74] | 3.44 [2.29, 5.16] | 2.66 [1.77, 4.01] | 0.73 [0.55, 0.96] | 3.64 [2.81, 4.70] | 5.08 [4.56, 5.66] | 0.57 [0.17, 1.90] | |

| Total # Cases | 1,005,933 | 1,368,849 | 374,155 | 30,782 | 19,306 | 63,184 | 276,761 | 55,771 | 38,308 | 67,551 | 44,976 | 35,139 |

^All ORC= all 10 obesity-related cancers, excluding breast cancer in women under 50. The 1948 birth cohort is the reference cohort, except among breast cancer aged ≥50 years, in which the 1933 birth cohort is the reference cohort.

Figure 1.

Incidence rate ratios by birth cohort for 10 obesity-related cancers diagnosed in 1983–2017, Australia (shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals).

Figure 2.

Incidence rate ratios by birth cohort for 10 individual obesity-related cancers in Australia (shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals). The 1948 birth cohort is the reference cohort.

Figure 3.

Incidence rate ratios by birth cohort for non-obesity-related cancers diagnosed in 1983–2017, Australia (shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals).

Figure 4.

Age-specific incidence by birth cohort from 1903 to 1988 for 10 obesity-related cancers, diagnosed in 1983–2017 Australia. Dots denote observed incidence by age groups and birth cohorts and solid lines represent the corresponding fitted rates from the age-period-cohort models.

The joinpoint analysis illustrated age trends for obesity-related and non-obesity-related cancers (Table 2, Figures 5 and 6). For obesity-related cancers, incidence increased in younger people and then stabilised or slightly decreased through middle age before a small, but significant, increase in those aged 70–84. There was a small increase in non-obesity related cancers over the same time period, though to a lesser extent than obesity-related cancers and not statistically significant in the more recent cohorts,

Table 2.

APC in obesity-related and non-obesity-related cancers by age diagnosed in 1983–2017, Australia.

|

Note: aThe APC is significantly different from zero at alpha=0.05. Statistically significant positive APCs are in light gray boxes, and statistically significant negative APCs are in dark gray boxes.

Figure 5.

Age-specific incidence and APC for 10 obesity-related cancers diagnosed in 1983–2017, Australia.

Figure 6.

Age-specific incidence and APC for non-obesity-related cancers diagnosed in 1983–2017, Australia.

These trends were broadly similar for obesity-related cancers in males and females separately with IRRs of 3.66 (95% CI 3.11–4.31) and 2.61 (95% CI 2.22–3.07) in the youngest cohorts, respectively. However, obesity related cancer incidence decreased in the most recent time period for males aged 65–79 and a small decrease was seen in females aged 35–44 (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). For non-obesity related cancers, there was a small overall increase in IRR for males for birth cohorts from 1953 to 1973 but APCs by age group showed decreasing trends in younger males whereas IRRs in younger females lower relative to the 1943 cohort (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figures 3 and 4).

The analysis for colorectal cancer showed that incidence for this obesity-related cancer increased in younger cohorts consistently for men and women (Supplementary Table 1). Overall there was an increase in incidence for those 55 and older and there was a statistically significant increase for people 25–34 and 35–44 in the most recent time period, by 7.2% per annum (2004–2017) and 2.7% per annum (2002–2017), respectively. In postmenopausal women with breast cancer, there was an increase in incidence with the exception of women 55–59, where there was a decrease from 2002–2007 which then plateaued, and women 60–64 whose incidence increased from 1983 to 2000 and then also stabilised.

The sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess 12 obesity-related cancers (Supplementary Table 1 & Supplementary Figure 5). The analysis displayed a slightly weaker birth cohort effect, with the IRR for all obesity-related cancers being 2.22 (2.00–2.46) for the most recent cohort (1988), representing the highest IRR compared to the reference cohort. This was partially driven by a decreased IRR in all women with breast cancer.

Discussion

Our study of over 1 million obesity-related cancer diagnoses identified that incidence has increased for recent Australian birth cohorts since the late 1940s. Conversely there was a decreasing trend in non-obesity related cancer incidence by birth cohort over the same time period. The increasing rates of most obesity-related cancers among recent birth cohorts identified in our study have been identified previously in similar studies around the world.8,21,29, 30, 31, 32 Evidence of a causal association exists for only sub-sites of three cancers (stomach, oesophageal and breast cancers). A sensitivity analysis including these cancers resulted in a lower IRR in the most recent cohort (2.22 vs 2.95 in the main analysis) supporting the association for sub-sites only. Additionally, the age-specific incidence trends largely reinforced these findings with increasing incidence in obesity-related cancers, with the exception of decreases seen in males 65–79 and females 35–44 when assessed separately.

The overall non-obesity-related cancer APC showed a significant decrease in incidence for most age groups in the most recent time period with the exception of those aged 70–79. This increase was reflected in males rather than females, where there was a consistent and significant decrease in incidence from the 1953 birth cohort onwards. In males, increased IRRs were evident from the same birth cohort, driving the overall indication of increasing incidence in non-obesity related cancers and largely driven by prostate cancer rates.

The age-period-cohort modelling approach has been used in other studies to explore obesity-related cancers. Sung et al similarly identified increasing risks of obesity-related cancers among recent birth cohorts in multiple myeloma, colorectal, uterine, kidney and pancreatic cancers from 1995 to 2014 in the United States,8 and Heer et al also identified increasing trends in some cancers in recent birth cohorts in Canada from 1983 to 2012.10 Other studies have also displayed increasing cancer incidence in younger birth cohorts particularly among kidney33 and colorectal cancers.21 More recent studies support the causal relationship between overweight and obesity and cancer,5,6 further reinforcing this ecological evidence. A large Israeli cohort identified increased cancer incidence from adolescent obesity as BMI increased.34 Increased risk was found in males but not in females, except when cervical and breast cancer cases were excluded.34 While our study shows increased incidence by birth cohort and age group in obesity-related cancers overall, there are differing trends by individual cancer types. There were notable increases in incidence by birth cohort in cancers of the colorectum, pancreas, liver, kidney, breast, uterus, and thyroid but decreasing incidence for cancers of the gallbladder and ovary. Evidence from mendelian randomisation studies reinforced causal relationships with cancers of the colorectum, endometrium, ovary, kidney, pancreas and oesophagus (adenocarcinoma) but similarly could not confirm causality for gallbladder cancer, gastric cardia cancer, and multiple myeloma, citing low power of the included studies.35

In our study, almost 65% of the obesity-related cases diagnosed were colorectal cancer and postmenopausal women with breast cancer. The increasing trend of colorectal cancer rates among younger cohorts, seen in Western countries including Australia and at least partially driven by increases in obesity levels, was not consistently found in high-income Asian countries,36 which likely reflecting differences in lifestyles across regions. Screening practices in Australia have contributed to the decreasing incidence of colorectal cancer since the establishment of the national program in 2006 targeting average-risk people aged 50–74.25 A decrease in colorectal cancer incidence in people 55 and older was found in this study for both males and females, whereas the rising incidence of people 25–44 identified here support the findings of an earlier Australian study.21 In Australia, it has been estimated that 49.8% of colorectal cancers are attributed to modifiable factors, and of this, 9% are attributable to overweight and obesity but to a greater extent in males compared to females,37 which is supported by our findings.

We identified increased incidence of breast cancers among postmenopausal women by birth cohort. In Australia, there is an organised biennial mammography based screening program for women aged 50–74 that may impact incidence rates in this age group,25 as well as other modifiable risk factors.37 International studies have identified similar breast cancer increases in incidence.38, 39, 40 The burden of obesity-related breast cancers in Korea has been estimated to nearly double in 2030 compared to 2013, likely due to nationwide lifestyle changes.39 A US study found that high BMI increased the incidence of breast cancer in women under 50 by approximately 3%.40 A global analysis found an increasing temporal incidence trend of breast cancer in postmenopausal women in countries undergoing a socio-economic transition but, for Australia, they found a non-significant increase in incidence from 1998 to 2012.38 This difference could be driven by the additional data used in our study, given the increasing trends are mostly seen in the most recent time period.

Kidney and pancreatic cancer and multiple myeloma incidence was found to be higher in younger cohorts but other local evidence showed that overall incidence may be stabilising41 or moderately increasing,25,42 respectively. The incidence of uterine cancer increased in younger cohorts, but this was not seen for ovarian cancer. A recent pooled analysis of Australian studies found that overweight and obesity was positively associated with increased risk of endometrial cancer, the most common form of uterine cancer in Australia, but not for ovarian cancer.43 The incidence of gallbladder cancer increased for older cohorts but showed a non-significant decreased incidence in the younger cohorts of this study. Recent Australian findings identified an overall increase in gallbladder incidence overall and by sex but noted an increase in the median age at diagnosis which is consistent with our findings.44

Additionally, screening and early detection practices can impact incidence trends, as has been noted for colorectal and breast cancer in Australia. The increase in thyroid cancer incidence identified in this analysis could also be partially attributed to changes in detection techniques. Despite this, approximately 19% of thyroid cancer cancers have been attributed to overweight and obesity.45,46 Surveillance programs for liver cancer facilitate an earlier diagnosis rather than increasing incidence rates.47 Increases can be attributed to key risk factors including viral hepatitis infection and alcohol consumption alongside overweight and obesity.48 In Australia, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis infection has steadily decreased overall but still remains high in some priority population groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.49 However, the increased risk of liver cancer with obesity has been identified as independent of other risk factors.50

The changing prevalence of key modifiable risk factors could also contribute to the increase in incidence of obesity-related cancers among recent birth cohorts. In Australia, smoking prevalence has decreased in recent decades and, as such, would have greater impact in those born before the late 1940s where, for example, a higher incidence of colorectal cancer was seen.51,52 Conversely, the gradual downward trend for non-obesity related cancers for the more recent cohorts could be partially attributed to the decreasing smoking prevalence and the inclusion of some smoking-related cancers (e.g. lung cancer) in this grouping. Additionally, high alcohol consumption (≥14 standard drinks/week) is associated with a higher risk of colorectal, breast and liver cancer but a lower risk of kidney cancer.53,54 However, the proportion of people drinking in excess of lifetime risk guidelines has reportedly declined in Australia.55 Other factors such as hormone imbalances, physical inactivity and environmental exposures can also increase the risk of these cancers and may contribute to the trends that cannot be isolated in these results.56 In our study, adjustments were not possible for these risk factors nor for hysterectomy trends or medication use (oral contraceptive or menopausal hormone therapy) which may affect the results and limit our ability to determine the causal contribution of specific risk factors to changes in cancer incidence.

Despite this and given the increasing obesity rates, known links to cancer, and rising incidence of obesity-related cancers in younger cohorts, this study supports obesity-related public policy initiatives as they contribute to reducing the cancer burden. It has been estimated that up to 13% of overweight and obesity-related cancers in men and 11% in women could be avoided over a 25-year period if overweight and obesity were eliminated from the Australian population (≈190,000 cancers avoided),57 thus nation-wide efforts are critically needed. Public policy can support obesity control and create environments that promote health lifestyle behaviours.7 In Australia, such policies have a high level of community support,58 but more limited political support. Governments have previously developed frameworks for action,59 which included initiatives such as reductions in children's exposure to unhealthy food advertising and clear nutrition labelling. Recent strategies reinforced previous calls to action for obesity control and outlined a range of cost-effective actions, including fiscal policy to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and reducing marketing of unhealthy foods to children.60,61 Additionally, the public understanding of the role of obesity in increasing cancer risk is considered low,62, 63, 64 thus including this in health promotion messaging may provide a novel angle to generate attention and motivate behavioural change and action. Using these frameworks and strategies to set clear targets, have consistent and accountable governance and invest in effective interventions is crucial moving forward to improve health outcomes,3 and could contribute to reducing the economic impact of obesity-related cancers. The rising rates of obesity-related cancers are becoming increasingly important to address given that obesity-related cancers have twice the economic burden compared to other cancers.65

Interventions to increase physical activity from early childhood have been shown to decrease the risk of developing obesity-related cancers including breast, colon and endometrial.66 Physical activity also improves metabolic health and reduces metabolic syndrome, which can result from improved insulin sensitivity, chronic inflammation, and endogenous sex steroids (e.g. lowering testosterone and oestradiol concentrations in postmenopausal women),67 which are associated with obesity development and cancer progression.68 Improving metabolic health has been shown to lower risk of developing obesity-related cancers, such as liver cancer.69,70 Obesity surgery can be effective as a weight reduction intervention and may help to reduce cancer incidence and mortality but individuals may still carry an elevated cancer risk after surgery.71,72 Therefore, primary prevention of obesity remains a priority, with particular focus on addressing adolescent obesity,34 with support from surgical interventions in adulthood in those most at risk.72

A strength of this study included using high standards of completeness and quality population-based incidence data,23 which allowed the analysis to be representative for the national population, while we used a systematic approach for the age-period-cohort modelling and joinpoint analysis across all major cancers. Analyses of these kinds have previously been used as a robust assessment of trends and their possible association with risk factor prevalence, in the absence of linked data. These analyses included an assessment by sex and highlight largely similar trends across the population. They provide guidance to further support policy and public health interventions to improve cancer-related outcomes and highlight cancers, that may be less common, but could be of growing concern as their incidence increases in younger cohorts.

This study is not without its limitations. As a population-based study, we are not able to infer cause and effect based on these results, which are not able to disentangle other drivers that could influence the trends for individual cancers. As a result, we are unable to claim that changing trends are solely a result of overweight and obesity. However, we know that overweight and obesity is an influential risk factor for these cancer types and, at least in part, is driving these changes. Age-period-cohort models are based on assumptions and one of which is that interactions between age and period can be described as birth cohort effects.8 However, our results suggest that there is no violation of this assumption because the observed age-specific rates by birth cohort are broadly close to the predicted rates. Our findings do not present data on race or sociodemographics, in which future studies may explore to identify at-risk populations for obesity-related cancers.

The incidence of obesity-related cancers in Australia has increased by birth cohort from 1903 to 1988, predominantly driven by rising colorectal cancer cases in recent generations. Increasing obesity prevalence is concerningly growing in high-income countries, with an increasing impact on several chronic diseases including cancer, particularly among younger people. This public health epidemic should be monitored with particular focus on prevention activities by implementing evidence-based interventions that create supportive food and physical activity environments and promote healthy weight from early in life to prevent the onset of obesity.

Contributors

EF, AA and XQY were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. AA and XQY were responsible for data analysis and preparing the tables and figures. AA and XQY were responsible for data acquisition. All authors were responsible for writing and editing of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are publicly available, and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The code developed for current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

The Daffodil Centre has received competitive grant and contract funding for non-related projects from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Australian Department of Health and Cancer Council Australia that include Dr Eleonora Feletto, Mr Paul Grogan and Professor Karen Canfell. Dr Eleonora Feletto received honoraria for presentations at the Japanese Cancer Association Conference and the APEC Regional Workshop on Capacity Building of Cancer Prevention and Control. Dr David Mizrahi has received a Fullbright Association Fellowship. Ms Clare Hughes has received funding through nib Healthsmart and NHMRC, the latter in collaboration with the University of Wollongong. Professor Karen Canfell is co-PI of an investigator-initiated trial of cervical screening, “Compass”, run by the Australian Centre for Prevention of Cervical Cancer (ACPCC), which is a government-funded not-for-profit charity. Compass receives infrastructure support from the Australian government and the ACPCC has received equipment and a funding contribution from Roche Molecular Diagnostics, USA. She is also co-PI on a major implementation program Elimination of Cervical Cancer in the Western Pacific which has received support from the Minderoo Foundation and the Frazer Family Foundation and equipment donations from Cepheid Inc.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100575.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Webber L, Divajeva D, Marsh T, et al. The future burden of obesity-related diseases in the 53 WHO European-Region countries and the impact of effective interventions: a modelling study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellew W, Bauman A, Kite J, et al. Obesity prevention in children and young people: what policy actions are needed? Public Health Res Pract. 2019;29(1):e2911902. doi: 10.17061/phrp2911902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nittari G, Scuri S, Petrelli F, Pirillo I, di Luca NM, Grappasonni I. Fighting obesity in children from European World Health Organization member states. Epidemiological data, medical-social aspects, and prevention programs. Clin Ter. 2019;170(3):e223–e230. doi: 10.7417/CT.2019.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer — viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research/American Institute for Cancer Research . WCRF; London: 2018. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Body Fatness and Weight Gain and the Risk of Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung H, Siegel RL, Torre LA, et al. Global patterns in excess body weight and the associated cancer burden. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(2):88–112. doi: 10.3322/caac.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(3):e137–e147. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Patel AV, et al. The association between body mass index and pancreatic cancer: variation by age at body mass index assessment. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(2):108–115. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heer EV, Harper AS, Sung H, Jemal A, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Emerging cancer incidence trends in Canada: the growing burden of young adult cancers. Cancer. 2020;126(20):4553–4562. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Exarchakou A, Donaldson LJ, Girardi F, Coleman MP. Colorectal cancer incidence among young adults in England: trends by anatomical sub-site and deprivation. PLoS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Onc. 2017;18(12):1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and obesity: an interactive insight Canberra AIHW; 2019 [cited 2022 2 Feb 2022]. Available from:https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-and-obesity-an-interactive-insight/related-material.

- 14.Ampofo AG, Boateng EB. Beyond 2020: modelling obesity and diabetes prevalence. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;167 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2018. National Health Survey: First Results, 2017-18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Y, Wang Z. Prevalence of three lifestyle factors among Australian adults from 2004 to 2018: an age-period-cohort analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(4):827–832. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes AJ, Lung TW, Bauman A, Howard K. Modelling obesity trends in Australia: unravelling the past and predicting the future. Int J Obes. 2017;41(1):178–185. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2021. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 - Key findings. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson LF, Antonsson A, Green AC, et al. How many cancer cases and deaths are potentially preventable? Estimates for Australia in 2013. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(4):691–701. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall BJ, Wilson LF, Olsen CM, et al. Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to overweight and obesity. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39(5):452–457. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feletto E, Yu XQ, Lew JB, et al. Trends in colon and rectal cancer incidence in Australia from 1982 to 2014: analysis of data on over 375,000 cases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(1):83–90. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberrra: 2019. Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality (ACIM) Books. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2017. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2020. Australian Cancer Database (ACD) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2021. Cancer in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistical Research and Applications Branch NCI . National Cancer Institute; Bethesda MD: 2020. Joinpoint Regression Program. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson C, Boyle P. Age-period-cohort analysis of chronic disease rates. I: modelling approach. Stat Med. 1998;17(12):1305–1323. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980630)17:12<1305::aid-sim853>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg PS, Check DP, Anderson WF. A web tool for age-period-cohort analysis of cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2296–2302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Harper A, Ruan Y, et al. International trends in the incidence of cancer among adolescents and young adults. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(11):1105–1117. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegel RL, Torre LA, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence in young adults. Gut. 2019;68(12):2179–2185. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young JP, Win AK, Rosty C, et al. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in Australia over two decades: report and review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(1):6–13. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh CM, Jung KW, Won YJ, Shin A, Kong HJ, Lee JS. Age-period-cohort analysis of thyroid cancer incidence in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(3):362–369. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furer A, Afek A, Sommer A, et al. Adolescent obesity and midlife cancer risk: a population-based cohort study of 2.3 million adolescents in Israel. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(3):216–225. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang Z, Song M, Lee DH, Giovannucci EL. The role of mendelian randomization studies in deciphering the effect of obesity on cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(3):361–371. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung RY, Tsoi KKF, Kyaw MH, Lui AR, Lai FTT, Sung JJ. A population-based age-period-cohort study of colorectal cancer incidence comparing Asia against the West. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;59:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteman DC, Webb PM, Green AC, et al. Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to modifiable factors: summary and conclusions. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39(5):477–484. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H, McCormack V, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(8):e1027–e1037. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JE, Lee SA, Kim TH, et al. Projection of breast cancer burden due to reproductive/lifestyle changes in Korean women (2013-2030) using an age-period-cohort model. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(4):1388–1395. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeiffer RM, Webb-Vargas Y, Wheeler W, Gail MH. Proportion of U.S. trends in breast cancer incidence attributable to long-term changes in risk factor distributions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(10):1214–1222. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman R, Kahokehr A, O'Callaghan M, D'Onise K, Foreman D. Trends in primary kidney cancer: a South Australian registry review. Renal Cancer. 2019;2(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barreto SG, D'Onise K. Pancreatic cancer in the Australian population: identifying opportunities for intervention. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(11):2219–2226. doi: 10.1111/ans.16272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laaksonen MA, Arriaga ME, Canfell K, et al. The preventable burden of endometrial and ovarian cancers in Australia: a pooled cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(3):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mollah T, Chia M, Wang LC, Modak P, Qin KR. Epidemiological trends of gallbladder cancer in Australia between 1982 to 2018: a population-based study utilizing the Australian Cancer Database. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2022;26(3):263–269. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.21-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glasziou PP, Jones MA, Pathirana T, Barratt AL, Bell KJ. Estimating the magnitude of cancer overdiagnosis in Australia. Med J Aust. 2020;212(4):163–168. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laaksonen MA, MacInnis RJ, Canfell K, et al. Thyroid cancers potentially preventable by reducing overweight and obesity in Australia: a pooled cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2022;150(8):1281–1290. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singal AG, Zhang E, Narasimman M, et al. HCC surveillance improves early detection, curative treatment receipt, and survival in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2022;77(1):128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melaku YA, Appleton SL, Gill TK, et al. Incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and risk factors of cancer in Australia and comparison with OECD countries, 1990-2015: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;52:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirby Institute . University of New South Wales; Sydney: 2018. HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmissible Infections in Australia: Annual Surveillance Report 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Wang X, Wang J, Yan Z, Luo J. Excess body weight and the risk of primary liver cancer: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2137–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber MF, Sarich PEA, Vaneckova P, et al. Cancer incidence and cancer death in relation to tobacco smoking in a population-based Australian cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2021;149(5):1076–1088. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scollo M, Winstanley M. 2016. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria.www.TobaccoInAustralia.org.au Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarich P, Canfell K, Egger S, et al. Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns and cancer incidence in an Australian cohort of 226,162 participants aged 45 years and over. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(2):513–523. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research . WCRF; London: 2018. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Alcoholic Drinks and the Risk of Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2021. Alcohol, Tobacco & Other Drugs in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colditz GA, Sellers TA, Trapido E. Epidemiology — identifying the causes and preventability of cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(1):75–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson LF, Baade PD, Green AC, et al. The impact of changing the prevalence of overweight/obesity and physical inactivity in Australia: an estimate of the proportion of potentially avoidable cancers 2013-2037. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(9):2088–2098. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson WL, Sarich P, Hughes C, Dessaix A. Monitoring changes in community support for policies on obesity prevention. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021;45(5):482–490. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Preventative Health Taskforce . Australian Government Department of Health; Canberra: 2010. Taking Preventative Action – a Response to Australia: the Healthiest Country by 2020 – the Report of the National Preventative Health Taskforce. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Australian Government Department of Health. National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030. Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra; 2021. Available from:https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-preventive-health-strategy-2021-2030.

- 61.Australian Government Department of Health. National Obesity Prevention Strategy 2022-2032. Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra; 2022. Available from:https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-obesity-strategy-2022-2032.

- 62.Sanderson SC, Waller J, Jarvis MJ, Humphries SE, Wardle J. Awareness of lifestyle risk factors for cancer and heart disease among adults in the UK. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shahab L, McGowan JA, Waller J, Smith SG. Prevalence of beliefs about actual and mythical causes of cancer and their association with socio-demographic and health-related characteristics: findings from a cross-sectional survey in England. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kippen R, James E, Ward B, et al. Identification of cancer risk and associated behaviour: implications for social marketing campaigns for cancer prevention. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):550. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hong Y-R, Huo J, Desai R, Cardel M, Deshmukh AA. Excess costs and economic burden of obesity-related cancers in the United States. Value Health. 2019;22(12):1378–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hidayat K, Zhou H-J, Shi B-M. Influence of physical activity at a young age and lifetime physical activity on the risks of 3 obesity-related cancers: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Rev. 2019;78(1):1–18. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rinaldi S, Key TJ, Peeters PHM, et al. Anthropometric measures, endogenous sex steroids and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: a study within the EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(11):2832–2839. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Friedenreich CM, Ryder-Burbidge C, McNeil J. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behavior in cancer etiology: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(3):790–800. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao Z, Zheng X, Yang H, et al. Association of obesity status and metabolic syndrome with site-specific cancers: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(8):1336–1344. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-1012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams LA, Roberts SK, Strasser SI, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease burden: Australia, 2019–2030. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(9):1628–1635. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Östlund MP, Lu Y, Lagergren J. Risk of obesity-related cancer after obesity surgery in a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;252(6):972–976. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e33778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aminian A, Wilson R, Al-Kurd A, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with cancer risk and mortality in adults with obesity. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2423–2433. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.9009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.