Abstract

The Escherichia coli promoter pBAD, under the control of the AraC protein, drives the expression of mRNA encoding the AraB, AraA, and AraD gene products of the arabinose operon. The binding site of AraC at pBAD overlaps the RNA polymerase −35 recognition region by 4 bases, leaving 2 bases of the region not contacted by AraC. This overlap raises the question of whether AraC substitutes for the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase in recognition of the −35 region or whether both AraC and sigma make important contacts with the DNA in the −35 region. If sigma does not contact DNA near the −35 region, pBAD activity should be independent of the identity of the bases in the hexamer region that are not contacted by AraC. We have examined this issue in the pBAD promoter and in a second promoter where the AraC binding site overlaps the −35 region by only 2 bases. In both cases promoter activity is sensitive to changes in bases not contacted by AraC, showing that despite the overlap, sigma does read DNA in the −35 region. Since sigma and AraC are thus closely positioned at pBAD, it is possible that AraC and sigma contact one another during transcription initiation. DNA migration retardation assays, however, showed that there exists only a slight degree of DNA binding cooperativity between AraC and sigma, thus suggesting either that the normal interactions between AraC and sigma are weak or that the presence of the entire RNA polymerase is necessary for significant interaction.

The sigma subunit of RNA polymerase (referred to here as sigma) is responsible for the binding of the holoenzyme to promoters during transcription initiation (2, 46). It does this by making sequence-specific contacts with bases in hexameric sequences centered at 10 and 35 bases upstream of the transcription start site on promoters (3, 13, 18, 32, 45, 50). At the −10 hexamer, sigma makes base-specific contacts with the nontemplate strand (23, 34, 41, 42). In addition to sigma-DNA interactions during initiation, protein-protein contacts also occur between transcriptional activators and subunits of RNA polymerase (1, 11, 14, 21, 22, 36, 43).

At many promoters, the recognition sequences of transcriptional activator proteins partly overlap the 6 bases of the −35 region that are contacted by the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase (4). In these cases, does the activator substitute for sigma in the recognition of the −35 region; do both proteins read the −35 region, necessitating overlapped reading by both proteins; or does sigma read an adjacent sequence?

On one hand, direct protein-protein contacts between sigma and upstream transcriptional activators seem to occur. At the λ pRM promoter, the binding site of λcI overlaps the −35 region for sigma by 2 nucleotides, and genetic experiments suggest an interaction between the λcI protein and the −35 recognition motif of sigma 70 (25, 31). Recently, interactions between sigma and Ada, an AraC homologue from the XylS family of proteins, have been demonstrated genetically at the ada, alkA, and aidB promoters (27, 28). A direct sigma-Ada interaction at the ada and aidB promoters has also been revealed biochemically with DNA migration retardation assays similar to those presented in this paper (27). On the other hand, at the PhoB-dependent PpstS and the CRP-dependent P1gal promoters, where the activator binding site completely overlaps the −35 hexamer, it appears possible that the activator can substitute entirely for recognition by sigma in the −35 region (26).

We studied the ara promoter, pBAD, which is under the control of two activators, CRP (29, 30) and AraC (12, 15) (Fig. 1). The binding of AraC to the I1 and I2 half-sites is stimulated by the presence of arabinose. When these sites are occupied by AraC, and if they overlap the −35 hexamer by 2 or 4 bases, transcription is actively initiated from pBAD (39).

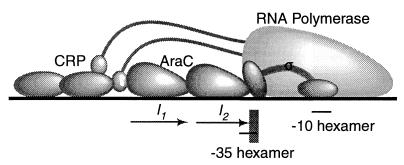

FIG. 1.

Polymerase-promoter and activator-promoter interactions at pBAD. The ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase contacts the −35 and −10 hexamers. Occupancy of the I1 and I2 half-sites by AraC activates transcription with the aid of the CRP protein, most likely utilizing the α-subunit–activator interactions as shown. The binding sites of ς70 and AraC overlap by 4 bp at pBAD. The nucleotides in the −35 hexamer that lie outside the region of overlap are shaded.

At pBAD, it is likely that the C-terminal domain of the α subunit of polymerase interacts both with CRP and with AraC (49). Two lines of reasoning suggest that AraC may also interact with the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. First, the R596H mutation in the sigma subunit allows AraC to stimulate pBAD to high levels in the absence of the normally required CRP (19). Second, although AraC can activate transcription from its position partially overlapping the −35 hexamer, it cannot activate (39) as CRP (14, 47) or OmpR (33) can when they are moved upstream by one or more helical turns.

We have examined whether sigma reads that part of the −35 region that lies outside the AraC-contacting region. If it does read this region, then AraC is not substituting for the contacts made by sigma in the region, and either sigma reads the −35 region as before, or it is only slightly displaced by the presence of AraC. We also analyzed sigma binding at the −35 hexamer at a second promoter where the AraC binding site overlaps the hexamer by only 2 bases.

Our results showed that sigma contacts the nonoverlapped bases of the −35 hexamer. Because of the close spatial placement of AraC and sigma on the promoter DNA, we then looked for an interaction between AraC and sigma that would reveal itself as cooperativity in the binding of AraC and sigma to DNA. To avoid the difficulties that would arise from the known interactions between AraC and the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase (49), we used purified sigma in the absence of the other RNA polymerase subunits. Also, to enhance the weak DNA binding affinity of sigma in the absence of core polymerase, we used a truncated variant of sigma (Δ133). This truncation rid the protein of the N-terminal acidic domain that interferes with binding of sigma to DNA (6, 7), and we were able to observe a slight cooperativity between AraC and sigma in binding to pBAD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The plasmid used for the initial construction of the I1-I*pBAD mutants contained an I1-I2pBAD–galK fusion in pES51 (20). The promoter region of the p7 plasmid, which carries an I1-I1–lacZ fusion (39), was replaced with the I1-I*pBAD promoter region, resulting in an I1-I*pBAD–lacZ fusion. Promoter activity was assayed in TR322 cells (araC+B+A+D+ galK Strr) (only relevant markers are shown) (16).

The plasmid used for overexpression of the ς70 variants was pQE30 (QIAgen), in which the rpoD gene is under the control of the T5 promoter (48). This was a kind gift from Alicia Dombroski. Protein was overexpressed in XL1 Blue cells (recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1) from Stratagene.

Construction of mutant I1-I*pBAD templates.

Site-directed PCR mutagenesis was performed to modify the promoter-proximal araI site in pBAD and to randomize the nonoverlapping bases (X) in the −35 box. The I* half-site (TAGCGGATCCATCCATA) contained the beginning sequence of the I2 half-site (TAGCGGATCCTACCTGA) and the later sequence of I1 (TAGCATTTTTATCCATA). The promoter region was amplified from pES51 with two oligo nucleotides, AAGATTAGCGGATCCATCCATAXXXXCTTTTTATCGCAA (containing the underlined I* araI half-site and the randomized nucleotides marked X) and ACTTAAACTAACCACTTGTG, in PCR buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 ng of each oligonucleotide, 1 ng of plasmid DNA as a template, and 5 U of Taq polymerase with 29 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 40°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The amplified fragment was treated with 5 μg of proteinase K/ml in 0.01 M Tris-Cl (pH 7.8), 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 56°C for 30 min. The sample was extracted with an equal volume of phenol followed by ethanol precipitation, digestion with BamHI and HindIII endonucleases, and electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel. The doubly digested fragment was purified from the agarose gel using the Geneclean II gel extraction kit from Bio 101 and cloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pES51 to obtain the I1-I*–galK constructs. To transfer the mutant promoter region to a lacZ-containing plasmid, the promoter region of each I1-I*–galK construct was cloned into the AseI and HindIII cloning sites of the p7 plasmid (39).

Assays.

The promoter activity of the pBAD promoter variants was quantitated in Escherichia coli TR322 cells (16) with either β-galactosidase or galactokinase levels. The cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 in M10 minimal salts, 0.4% glycerol, 10 μg of vitamin B1 per ml, 0.4% Casamino Acids, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.2% arabinose (44), 1 ml was withdrawn, and promoter activity was assayed for β-galactosidase, as described by Miller (37), or for galactokinase (10, 35).

Construction of promoter templates for the DNA migration retardation assay.

End-labeled DNA fragments were generated by PCR using two oligonucleotides such that the I1-I* site was centrally located on the 100-bp product. PCR was performed using 100 ng of γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide (ATTTGCACGGCGTCACAC) at 106 cpm/ng, 300 ng of unlabeled oligonucleotide (CGTTTCACTCCATCCAAA), and 10 ng of template plasmid with 0.4 U of Taq polymerase in PCR buffer for 29 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min.

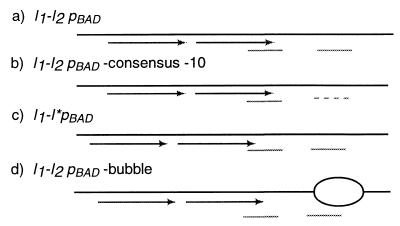

The I1-I2pBAD (Fig. 2a), I1-I2pBAD consensus −10 (Fig. 2b), and I1-I*pBAD (Fig. 2c) variant promoter fragments used to test for sigma binding were generated by PCR. The I1-I2pBAD bubble (Fig. 2d) was constructed by annealing two oligonucleotides. For the I1-I2pBAD consensus −10 template, the TATAAT sequence at the −10 box was introduced into pBAD by in vitro mutagenesis as described below before PCR amplification.

FIG. 2.

DNA template variants used to test sigma binding. The two AraC binding half-sites are shown with arrows (underlined in the sequences), and the −35 and −10 hexamers for sigma are shown with solid or broken lines (boldface in the sequences). (a) I1-I2pBAD with the wild-type araI half-sites for AraC and the 4-nucleotide overlap at the −35 hexamer. The sequence of the −10 hexamer was not changed. 5′GCCCATAGCATTTTTATCCATAAGATT AGCGGATCCTACCTGACGCTTTTTATCGCAACTCTCTACTGTTTCTCC 3′. (b) I1-I2pBAD consensus −10. The −10 hexamer in I1-I2pBAD was changed to the consensus sequence TATAAT to generate a stronger ς70 binding site. 5′G CCCATAGCATTTTTATCCATAAGATTAGCGGATCCTACCTGACGCTT TTTATCGCAACTCTCTATAATTTCTCC3′. (c) I1-I*pBAD containing the I* site in place of the I2 araI half site in pBAD. The sequence of the nonoverlapping nucleotides in the −35 hexamer was the same as the parental 5′GACG3′. The I* site is not as tight a binding site for AraC as I1 but is tighter than the I2 site. 5′GCCCATAGCATTTTTATCCATAAGATTAGCGGATCCATCCATAGAC GCTTTTTATCGCAACTCTCTACTGTTTCTCC3′. (d) I1-I2pBAD bubble is the same as the wild-type I1-I2pBAD with a heteroduplex mismatched stretch of DNA (lowercase letters) at the −10 region. 5′GCCCATAGCATTTTTATCCATAA GATTAGCGGATCCTACCTGACGCTTTTTATCGCAACTCTCTAgcacttctcc ATACCCG3′.

For the in vitro mutagenesis reaction, 50 ng of double-stranded-DNA template was mixed with 125 ng each of the two complementary oligonucleotides containing in 50 μl of 10 mM KCl, 6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10 μg of nuclease-free bovine serum albumin (BSA)/ml. The extension reaction was performed with 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase with the following cycling parameters: 95°C for 30 s and then 18 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 12 min per cycle. The reaction generated unmethylated complementary double-stranded DNA containing the desired mutation. Ten units of DpnI endonuclease was added for 1 h at 37°C to digest the original methylated DNA template present in the reaction. This is the site-directed mutagenesis technique of the QuikChange protocol of Stratagene.

End-labeled DNA templates for the in vitro DNA migration retardation assay were prepared by PCR amplification. For PCR, 100 ng of γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide at 106 cpm/ng, 300 ng of unlabeled oligonucleotide(s), and 25 ng of template plasmid containing the required promoter were mixed in 100 μl of PCR buffer. The PCR cycle parameters were 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 29 cycles. The oligonucleotides used to amplify the I1-I2pBAD, I1-I2pBAD consensus −10, and I1-I*pBAD templates were ATTTGCACGGCTCACAC and CGTTTCACTCCATCCAAA. The I1-I2pBAD bubble DNA was prepared by hybridizing ACTTTGCTAGCCCATAGCATTTTTATCCATAAGAT TAGCGGATCCTACCTGACGCTTTTTATCGCAACTCTCTAgcacttctccATA CCCGTTTTTTTGG and CCAAAAAAACGGGTATcctcttcacgTAGAGAGTT GCGGATAAAAAGCGTCAGGTAGGTACCGCTATCTTATGGATAAAAA TGCTATGGGCTAGCAAAGT (the underlined sequences represent the AraC half-sites I1 and I2, the boldface letters represent the −35 sequence, and the lowercase letters show the bubble region around the −10 region). For this I1-I2pBAD bubble, the two oligonucleotides were mixed in equimolar concentrations in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM KCl, heated for 10 min at 94°C, and cooled slowly to room temperature over the course of an hour.

Purification of the sigma subunit.

The R596H mutation was introduced into the Δ133 sigma-encoding DNA template by in vitro site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange). The hexahistidine tag-containing Δ133 and R596HΔ133 sigma variants were overexpressed, purified from inclusion bodies by using nickel columns under denaturing conditions, and renatured as described previously (9, 48).

DNA migration retardation assay.

The DNA migration retardation assay was used to measure dissociation rates of AraC from mutant I1-I*pBAD templates as previously described (17). AraC was bound to the mutant I1-I*pBAD templates in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 1 mM K-EDTA, 75 mM or 150 mM KCl (depending on the salt concentration required), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, 50 mM arabinose, and 0.05% NP-40. The higher salt concentration was used when the binding reactions were performed in the presence of arabinose because AraC binds more tightly to DNA in the presence of its ligand and does not show any significant dissociation at lower salt concentrations. For the binding reaction, purified AraC was added so that just 100% of 1 ng (∼104 cpm) of end-labeled DNA was bound. Binding of AraC to DNA was allowed to proceed for 10 min, after which an excess of a competitor containing four tandem I1 half-sites was added. Aliquots were withdrawn at different time points and loaded onto a native 6% polyacrylamide gel cross-linked with 0.1% methylene-bisacrylamide. The samples were separated by electrophoresis at 150 V for 1.5 h in 100 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.4) and 1 mM K-EDTA. A Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager PC was used to quantitate bound versus free DNA, and dissociation rates were determined from a plot of the DNA fraction bound by AraC as a function of dissociation time by a least-squares fit.

Sigma or variants were diluted in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 0.4 μg of BSA/ml, and 5% glycerol. Binding reactions were performed in 25 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.4), 14 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.03% Triton X-100, 100 μg of BSA/ml, and 5% glycerol. To look for cooperative DNA binding between AraC and sigma, sufficient AraC was added so that ∼100% of 1 ng (∼104 cpm) of γ-32P-end-labeled DNA would be bound. After 10 min, sigma protein was added for 20 min before electrophoresis of the sample to separate free DNA and the various protein-bound species.

RESULTS

Do Sigma and AraC both contact the −35 region?

Since the I2 binding half-site of AraC overlaps the promoter −35 recognition region by 4 bp, it is conceivable that the sigma subunit does not contact the −35 region at all and that AraC assumes the role normally taken by part of sigma. One way to determine whether sigma makes DNA contacts in the −35 region is to vary the sequence of that part of the −35 region that is not contacted by AraC. If promoter activity is insensitive to such sequence changes, we could reasonably infer that sigma does not contact DNA in the region.

Altering the two bases of the natural ara pBAD promoter −35 region (Fig. 3) that are not part of I2 from CG→TT and CG→CC decreased promoter activity to 90 and 50%, respectively, of that of the parental sequence. These results suggest that sigma does read the sequence of the two bases. In the P22 ant promoter however, Moyle and coworkers found that C and G are equivalent at position −30 and that a C-to-T change at position −31 reduces activity to 10% (38). Most likely the difference between the modest change to 90% activity in our system and the dramatic change to 10% in the ant promoter results from the very different contexts in which the sequence changes occur. In the ara system, AraC and CRP are required for normal activation of RNA polymerase, whereas in the ant system, no auxiliary activators are needed by RNA polymerase.

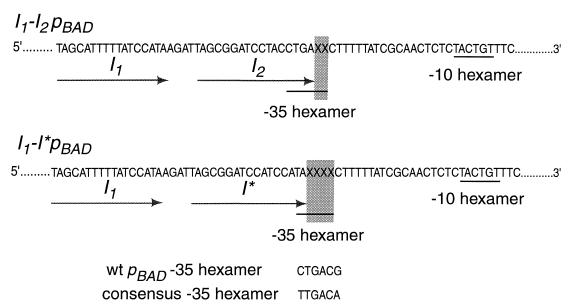

FIG. 3.

Sequences of I1-I2pBAD promoter (top) and I1-I*pBAD promoter (bottom). Oligonucleotide-directed PCR mutagenesis was used to randomize the nonoverlapping bases (marked X and shaded) in the −35 hexamer. wt, wild type.

To increase the number of bases in the −35 region that are not contained within the promoter-proximal AraC binding site, we designed a promoter variant, I1-I*pBAD (Fig. 3), in which the AraC binding site has been moved upstream by 2 bases. The I* site contains the beginning sequence of the I2 site and the later sequence of the I1 site. This promoter is still AraC dependent and is 2.3 times as active as the wild-type pBAD promoter. Making such a change in the promoter permits four bases in the −35 region to be altered without affecting AraC binding. We chose to alter these four nucleotides in two ways—by directed and by random mutagenesis. If, despite its requirement for AraC and CRP for full stimulation, and despite the results obtained from the 2-base overlap, pBAD possesses the same promoter sequence dependence as “bare” promoters like P22 ant, then a change to taGACA should have a particularly dramatic stimulatory effect because of increased homology to the consensus −35 hexamer. Table 1 shows that the activity of taGACA was not significantly different from that of the parental sequence, taGACG. The activities of most of the entries shown in Table 1 that resulted from random mutagenesis, however, were strongly dependent upon the sequence of the −35 region outside the I* half-site, thereby indicating that sigma does contact the four bases.

TABLE 1.

Properties of the I1-I* variant promoters

| −35 sequence | Relative promoter activitya | AraC dissociation half-time (min)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| −Ara | +Ara | ||

| Parental taGACG | 1.00 | 25 | 110 |

| taGACA | 1.00 | 22 | 110 |

| taGCCT | 0.35 | 25 | |

| taTGAT | 0.30 | 26 | |

| taTGGT | 0.30 | 25 | 110 |

| taGGTT | 0.20 | 26 | |

| taCAAC | 0.20 | ||

| taCAAT | 0.20 | 22 | 110 |

| taATTA | 0.20 | 23 | |

| taTGTC | <0.05 | 28 | |

| taTTTG | <0.05 | 28 | 110 |

| taATTG | <0.05 | 26 | |

| taTTGT | <0.05 | 26 | 100 |

| taAGGT | <0.05 | 28 | |

| taAAGT | <0.05 | 28 | |

| taATTT | <0.05 | 26 | |

| taTTCT | <0.05 | 25 | |

Relative in vivo promoter activities were quantitated from β-galactosidase assays performed in the presence of arabinose on exponentially growing TR322 cells containing the mutant promoters in the p7 plasmid. The parental I1-I*pBAD promoter activity of 16,000 U was assigned a relative value of 1.

The dissociation half-times of AraC from mutant I1-I*pBAD DNA templates in 75 mM KCl (no arabinose [−Ara]) and 150 mM KCl (plus arabinose) were measured using the DNA migration retardation assay as described in Materials and Methods and in the legend to Fig. 4.

Two potential factors could invalidate the conclusion that I1-I*pBAD activity is dependent upon the identity of the −35 region nucleotides outside the I* half-site. First, introduction of the altered nucleotides might have inadvertently altered nucleotides elsewhere in the plasmid as well, for example, within the β-galactosidase gene. To verify that the decreased levels of β-galactosidase activity we observed with some of the variants were indeed due to changes in the −35 region of the promoter and not due to extraneous mutations elsewhere on the plasmids, we changed the four randomized bases in three mutant templates back to the parental sequence by oligonucleotide-directed site-specific mutagenesis. These changes returned the β-galactosidase levels to those observed for the parental sequence, indicating that the plasmid carried no additional relevant mutations on the mutant templates.

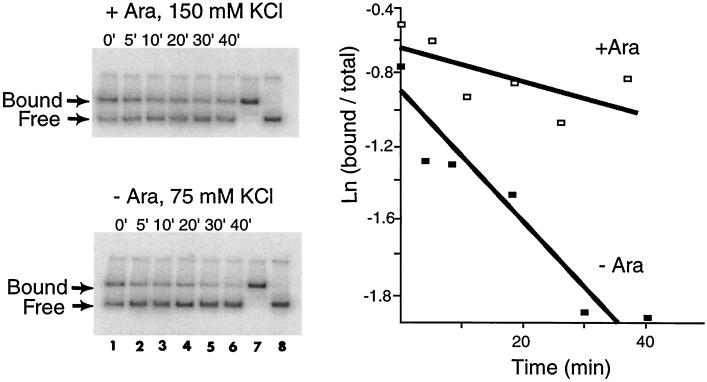

A second possibility is that AraC binding actually is sensitive to DNA sequence outside I1 and I*. This possibility was excluded by measurement of the dissociation rates of AraC from the I1-I*pBAD templates using the in vitro DNA migration retardation assay (typical data is shown in Fig. 4). Identical dissociation rates were obtained for AraC from all the I1-I*pBAD templates (Table 1), indicating that the reduction in promoter activity from these templates was unlikely to be due to altered AraC binding at the −35 region. The results suggest that altered sigma binding is the cause of the reduction.

FIG. 4.

In vitro DNA migration retardation assays to measure dissociation rates of AraC from the I1-I*pBAD templates. The two gels show the bound and free DNA at each time point (lanes 1 to 6) as well as fully bound DNA (lane 7) and free DNA (lane 8). The ratio of bound to total DNA was quantitated and plotted as a function of time. + Ara, with arabinose; − Ara, without arabinose.

Does sigma directly interact with AraC?

On one hand, the partial interdigitation of the AraC and RNA polymerase sigma subunit binding sites on DNA suggests that the two proteins could be located very close to each other and hence might have critical interactions with one another. On the other hand, the fact that the binding site of AraC can be moved 2 bases upstream without strongly affecting promoter activity, as in I1-I1pBAD (39) and I1-I*pBAD, suggests that perhaps AraC and sigma do not make specific contacts with each other. To test if AraC and sigma do interact with one another, we looked for cooperativity in their binding to DNA.

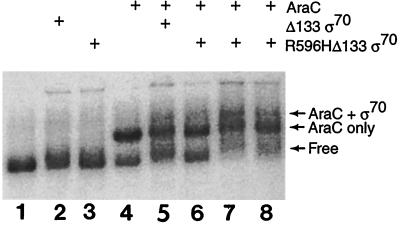

Purified sigma factor does not detectably bind to promoters by itself, but truncation of its acidic N-terminal domain reveals a weak promoter binding specificity (6, 7, 48). Therefore in looking for cooperativity between AraC and sigma factor in binding at AraC-activated promoters, we used a sigma variant with its N-terminal 133 amino acids deleted. The binding of sigma was examined on I1-I2pBAD and parental I1-I*pBAD templates, but no binding was observed on either template in the presence or absence of bound AraC protein (see Materials and Methods for a description of the DNA templates). Changing the conserved arginine at position 596 to a histidine in the sigma subunit enables RNA polymerase to be active on pBAD in the absence of CRP (19). Possibly the increased activation results from a sigma-AraC interaction, either an interaction where none existed before or a stronger interaction. Therefore, we introduced the R596H mutation into the Δ133 sigma variant. We were still unable to observe sigma binding to either the I1-I2pBAD or parental I1-I*pBAD DNA in the presence or absence of AraC. To create a stronger sigma binding site on pBAD, we changed the −10 hexamer to the consensus −10 sequence (see Materials and Methods), but still no binding was observed for either the Δ133 or the R596HΔ133 sigma variant on I1-I2pBAD consensus −10.

In a further effort to increase sigma binding, we used a template that mimics the DNA present in the open complex (RPo) during transcription initiation (6, 8). Such a bubble sequence provides a significant advantage for sigma binding, as shown by the preference of RNA polymerase holoenzyme for binding to premelted sequences (5). We used a heteroduplex mismatch bubble-containing template, I1-I2pBAD bubble, that contained the AraC binding sites, I1 and I2, with a mismatch region spanning the −10 region (see Materials and Methods). With such DNA, we observed some AraC-dependent DNA binding by the Δ133 and R596HΔ133 sigma variants (Fig. 5). Using another bubble template with binding sites for AraC and the consensus −10 region on the nontemplate strand of the bubble (34) did not enhance binding by sigma in the presence or absence of AraC. We note that the AraC-dependent binding by the truncated sigma protein in all these experiments was not completely reliable, and occasional experiments failed to demonstrate any cooperativity in the binding of AraC and sigma to DNA.

FIG. 5.

DNA migration retardation assay showing weak cooperativity in the binding of AraC and ς70 to I1-I2pBAD bubble DNA. The ingredients present (+) are indicated, and except in lanes 7 and 8, where the concentrations of R596HΔ133 ς70 were 190 nM and 130 nM, respectively, the concentrations used were 420 pM AraC, 60 nM Δ133 ς70, and 380 nM R596HΔ133 ς70.

DISCUSSION

Our experiments yield the following conclusions: AraC and the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase both make contacts with DNA in the −35 region of the pBAD promoter, and interactions between AraC and a truncated form of sigma can be observed in their binding in vitro to DNA, but these interactions are not strong.

The −35 hexamer of pBAD shares homology of four bases with the consensus −35 sequence, making it a potentially tight binding site for the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase (Fig. 3). On the other hand, because the polymerase-proximal half-site of AraC overlaps the −35 region by 4 bp, it is possible that AraC substitutes for the role taken by the domain of sigma that normally contacts the −35 region. In the experiments reported here, we found that pBAD activity is strongly dependent on the identities of the bases of the −35 hexamer that are not contacted by AraC. We presume, then, that these bases are contacted by sigma. Consequently, we further presume that either the remaining bases of the −35 region are also contacted by the sigma subunit or sigma is displaced and reads the bases immediately adjacent to the AraC binding site.

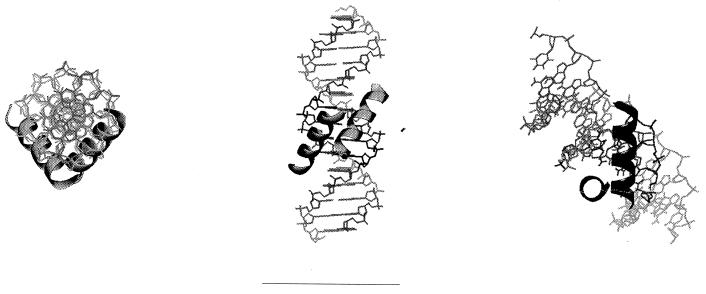

It is possible that AraC and the sigma subunit sequentially contact the common four bases in their partially overlapping binding sites at pBAD. We note, however, that simultaneous contact of these bases by alpha helices is also geometrically possible (Fig. 6). Our detection of cooperativity, albeit weak, in the binding of sigma and AraC to the DNA indicates a direct interaction between the two, suggesting simultaneous DNA binding. We must add that our in vitro binding studies utilized AraC and the sigma subunit alone but that the normal binding involves AraC and the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. The additional subunits of RNA polymerase could also interact with AraC or alter the structure of sigma and alter the interaction.

FIG. 6.

Model showing simultaneous recognition of four overlapping bases by two α-helices fitted into the major groove visualized from the top (left), front (middle), and side looking down one DNA major groove directly at one α-helix (right).

We first used a truncated variant of sigma (Δ133) that lacked the N-terminal acidic domain to enhance the weak DNA binding affinity of sigma in the absence of core polymerase. Because we observed no binding by the truncated sigma factor and no binding cooperativity between AraC and sigma, we then tried DNA templates that should have higher affinity than double-stranded DNA. Ultimately, we did observe binding cooperativity between AraC and truncated sigma, but this required the use of a DNA template possessing a single-stranded region in the −10 region. We are aware of only one other experiment to examine by direct biochemical means an interaction between an upstream activator and sigma factor (27). This work used the Ada protein, double-stranded DNA, and intact sigma factor. As significant binding cooperativity was observed with the Ada and sigma proteins at the ada and aidB promoters, it is possible that the Ada protein interacts significantly more strongly with sigma than does AraC. Alternatively, it is possible that in removing the N-terminal portion of sigma to enhance its DNA binding abilities, we also removed important regions for the AraC-sigma protein interaction.

Promoter recognition at pBAD by sigma is intriguing because, while any deviation from the parental sequence causes a reduction in promoter activity, we could see no correlation between specific sequence changes and promoter activity. Similarly, at the pmelR promoter, positions 3 to 6 of the −35 region lie outside the CRP binding site and play an important role in activation by sigma. Some −35 hexamer sequences at pmelR are more tolerant of substitutions than others, and mutations that change nonconsensus bases to consensus do not necessarily increase promoter activity (40). Similar observations have been noted with the melAB promoter (24) and the P22 ant promoter (38).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alicia Dombroski for helpful advice and for providing the Δ133 sigma template and the purification protocol and members of our laboratory for ongoing discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM18277 to R.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger D K, Narberhaus F, Kustu S. The isolated catalytic domain of NIFA, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein, activates transcription in vitro: activation is inhibited by NIFL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:103–107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess R R, Travers A A, Dunn J J, Bautz E K F. Factor stimulating transcription by RNA polymerase. Nature. 1969;221:43–46. doi: 10.1038/221043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chenchick A, Beabealashvilli R, Mirzabekov A. Topography of interaction of E. coli RNA polymerase subunits with the lacUV5 promoter. FEBS Lett. 1981;128:46–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)81076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collado-Vides J, Magasanik B, Gralla J D. Control-site location and transcriptional regulation in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:371–394. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.371-394.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daube S S, von Hippel P H. Interactions of Escherichia coli ς70 within the transcription elongation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8390–8395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dombroski A I, Walter W A, Record M T, Jr, Siegele D N, Gross C A. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription initiation factor ς70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell. 1992;70:501–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90174-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dombroski A I, Walter W A, Gross C A. Amino terminal amino acids modulate ς-factor DNA-binding affinity. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2446–2455. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dombroski A J. Recognition of the −10 promoter sequence by a partial polypeptide of ς70in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3487–3494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dombroski A J. Sigma factors: purification and DNA binding. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:135–143. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn T, Hahn S, Ogden S, Schleif R. An operator at −280 base pairs that is required for repression of araBAD operon promoter: addition of DNA helical turns between the operator and promoter cyclically hinders repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5017–5020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class I CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Englesberg E, Irr J, Powers J, Lee N. Positive control of enzyme synthesis of gene C in the l-arabinose system. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:946–957. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.4.946-957.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardella T, Moyle H, Susskind M M. A mutant Escherichia coli ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase with altered promoter specificity. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaston K, Bell A I, Kolb A, Buc H, Busby S J. Stringent spacing requirements for transcriptional activation by CRP. Cell. 1990;62:733–743. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenblatt J, Schleif R F. Arabinose C protein: regulation of the arabinose operon in vitro. Nat New Biol. 1971;233:166–170. doi: 10.1038/newbio233166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn S, Dunn T, Schleif R F. Upstream repression and CRP stimulation of the Escherichia colil-arabinose operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;82:3129–3133. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrickson W, Schleif R F. Regulation of the Escherichia coli L-arabinose operon studied by gel electrophoresis DNA binding assay. J Mol Biol. 1984;174:611–628. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horowitz M S, Loeb L A. DNA sequence of random origin as probes of E. coli promoter architecture. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14724–14731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J C, Gross C A. Mutations in the sigma subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase which affect positive control of transcription. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:7–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00327502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huo L, Martin K, Schleif R F. Alternative DNA loops regulate the arabinose operon in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5444–5448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igarashi K, Ishihama A. Bipartite functional map of the E. coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit: involvement of the C-terminal region in transcriptional activation by cAMP-CRP. Cell. 1991;65:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90553-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joung J K, Keopp D M, Hocthschild A. Synergistic activation of transcription by bacteriophage λ cI protein and E. coli cAMP receptor protein. Science. 1994;265:1863–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.8091212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kainz M, Roberts J W. Structure of transcription elongation complexes in vivo. Science. 1992;255:838–841. doi: 10.1126/science.1536008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keen J, Williams J, Busby S. Location of essential sequence elements at the Escherichia coli melAB promoter. Biochem J. 1996;318:443–449. doi: 10.1042/bj3180443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuldell N, Hochschild A. Amino acid substitutions in the −35 recognition motif of ς70 that result in defects in phage λ repressor-stimulated transcription. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2991–2998. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2991-2998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Grimes B, Fujita N, Makino K, Malloch R A, Hayward R S, Ishihama A. Role of the sigma 70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in transcription activation. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:405–413. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landini P, Bown J A, Volkert M R, Busby S J W. Ada protein-RNA polymerase ς and α subunit-promoter DNA interaction are necessary at different steps in transcription initiation at the Escherichia coli ada and aidB promoters. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13307–13312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landini P, Busby S J W. The Escherichia coli Ada protein can interact with two distinct determinants in the ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase according to promoter architecture: identification of the target of Ada activation at the alkA promoter. J Biol Chem. 1998;181:1524–1529. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1524-1529.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee N, Francklyn C, Hamilton E. Arabinose-induced binding of AraC protein to araI2 activates the araBAD operon by the AraC activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8814–8818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee N, Wilcox G, Gielow W, Arnold J, Cleary P, Englesberg E. In vitro activation of the transcription of araBAD operon by AraC activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:634–638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Moyle H, Susskind M M. Target of the transcriptional activation function of phage λ cI protein. Science. 1994;263:75–77. doi: 10.1126/science.8272867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Losick R, Pero J. Cascades of sigma factors. Cell. 1981;25:582–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda S, Mizuno T. Evidence for multiple OmpR-binding sites in the upstream activation sequence of the OmpC promoter in E. coli: a single OmpR-binding site is capable of activating the promoter. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:501–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.501-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marr M T, Roberts J W. Promoter recognition as measured by binding of polymerase to nontemplate strand oligonucleotide. Science. 1997;276:1258–1260. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKenney K, Shimatake H, Court D, Schmeissner U, Brady C, Rosenberg M. A system to study promoter and terminator signals recognized by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Gene Amplif Anal. 1981;2:383–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller A, Wood D, Ebright R H, Rothman-Denes L B. RNA polymerase β′ subunit: a target of DNA binding independent activation. Science. 1997;275:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyle M, Waldburger C, Susskind M M. Heirarchies of base pair preferences in the P22 ant promoter. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1944–1950. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1944-1950.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeder T, Schleif R. AraC protein can activate transcription from only one position and when pointed in only one direction. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:205–218. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhodius V A, West D M, Webster C L, Busby S J W, Savery N J. Transcription activation at Class II CRP-dependent promtoer: the role of different activating regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:326–332. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ring B Z, Roberts J W. Function of a nontranscribed DNA strand site in transcription elongation. Cell. 1994;78:317–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts C W, Roberts J W. Base-specific recognition of the nontemplate strand of promoter DNA by E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell. 1992;86:495–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross W, Gosink K K, Salomon J, Igarashi K, Zou C, Ishihama A, Severnov K, Gourse R L. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science. 1993;262:1407–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.8248780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schleif R F, Wensink P. Practical methods in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegele D A, Hu J C, Walter W A, Gross C A. Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the sigma 70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:591–603. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Travers A A, Burgess R R. Cyclic re-use of the RNA polymerase sigma factor. Nature. 1969;222:537–540. doi: 10.1038/222537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ushida C, Aiba H. Helical phase dependent action of CRP: effect of the distance between the CRP site and the −35 region on promoter activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6325–6330. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson C, Dombroski A J. Region 1 of ς70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by E. coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:60–74. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Schleif R F. Catabolite activator protein mutations affecting the activity of the araBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:195–200. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.195-200.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuber P, Healy J, Carter H L, Cutting S, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Mutation changing the specificity of an RNA polymerase sigma factor. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:605–614. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]