Abstract

Objectives: Suffering is intimately linked to the experience of illness, and its relief is a mandate of medicine. Advances in knowledge around terminal illness have enabled better management of the somatic dimension. Nevertheless, there is what can be called “non-somatic” suffering which in some cases may take precedence. Inspired by Paul Ricoeur's thinking on human suffering, our aim in this qualitative study was to better understand the experience of non-somatic suffering. Methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 19 patients. The results were qualitatively analyzed following a continuous comparative analysis approach inspired by grounded theory. Results: Three key themes synthesize the phenomenon: “the being enduring the suffering”, “the being whose agency is constrained”, and “the being in relationship with others.” The first describes what patients endure, the shock and fears associated with their own finitude, and the limits of what can be tolerated. The second refers to the experience of being restricted and of mourning the loss of their capacity to act. The last describes a residual suffering related to their interactions with others, that of loneliness and of abandoning their loved ones, two dimensions that persist even when they have accepted their own death. Conclusions: Non-somatic suffering can be multifarious, even when minimized by the patient. When evaluating suffering, we must keep in mind that patients can reach a “breaking point” that signals the state of unbearable suffering. In managing it, we probably need to make more room for family and friends, as well as a posture of caring based more on presence and listening.

Keywords: non-somatic suffering, palliative care, patients’ perspectives, Ricoeur

Introduction

It is generally accepted that alleviating suffering is a primary aim of medicine1-3 and even more so, of palliative care (PC).4,5 Nevertheless, despite the importance of suffering in our lives, research into this phenomenon is still in the early days.6,7

In the healthcare literature, several attempts at defining suffering have been published. The most accepted definition remains Cassell's 8 proposal that suffering is severe distress induced by a loss of integrity and cohesion of the person, or by a real or apprehended threat of an attack on this integrity. Many authors have corroborated this definition.9-11 However, critiques have recently been published. For example, Cassell's differentiation between pain and suffering is now contested.12,13 Likewise, the fact that Cassell's conception of suffering relies on a threat to the integrity of the person is problematic, as some can suffer without feeling that threat.6,14

Alternatively, drawing upon the thinking of Cecily Saunders, Beng and colleagues 15 distinguish four types of suffering: somatic, psychological, social, and existential. Thus, suffering includes somatic dimensions associated with the bodily experience of illness, but also stems from non-somatic dimensions corresponding to the psychological, social, and existential impacts of illness. This dichotomy between somatic and non-somatic dimensions also appears in other empirical studies. For example, two survey studies, one done in Australia on 100 patients coming from a day oncology clinic 16 and the other on 75 dying patients recruited by general practitioners in the Netherlands, 17 have shown the significant entanglement between physical symptoms and non-somatic impairments. These results have been corroborated by qualitative studies done in the UK and in Switzerland.9,18

Some research suggests patients experience non-somatic suffering more intensely than the strictly physical suffering of illness. While studies by Chochinov's group in Manitoba and Australia19-22 build on this, Krikorian and colleagues, in their literature review of 145 articles, conclude that “many [patients] contend that most of their suffering derives from non-physical sources”. 23 This is particularly well illustrated by research in Canada following enactment of the law decriminalizing medical assistance in dying (MAID). 24 In that research, requests for MAID were usually motivated not by physical complaints, but rather by non-somatic considerations such as loss of dignity, not wanting to be a burden to others, and inability to enjoy life. These results are corroborated by other studies from the United States and elsewhere in Canada.25-27

However, in a systematic review of research published between 1992 and 2012, Best and colleagues concluded there was no clear definition or consensus on what constitutes non-somatic suffering, 28 as evidenced by the many synonyms used to describe it: depression, death anxiety, or anhedonia, among others. 29 Since the publication of that review, to our knowledge, aside from one study of US veterans showing that they confused psychosocial distress with physical pain, 30 few studies have helped to better define non-somatic suffering.

Other definitions of suffering are based on philosophical works. For example, drawing on Aristotle's ideas, van Hooft differentiates among vegetative life (biological processes), appetitive life (related to desire and emotions), practical and rational life (agency), and contemplative life (the sense of meaning of one's existence). Suffering occurs when one of these dimensions cannot be lived, leading to frustration. 1 For Wittgenstein, suffering requires that the phenomenon be experienced over time and occupy a central place in a subject's psychic life. 14 For Frankl, loss of physical well-being alone does not cause suffering, but rather, the determining factor is loss of meaning. 31

Finally, a definition not widely known in the biomedical community comes from the work of Paul Ricoeur, whose conception stems from his idea of what it is to be human. 32 In his view, man is sometimes acting, sometimes suffering. Ricoeur asserts that suffering is not just physical pain, nor even mental pain, but the decline, or even destruction, of one's capacity to act, of potency, experienced as an attack on the integrity of the self. 33 The endurance or bearing up that is inherent in the human being's capacity to be affected by life is revealed, in its passive dimension, as a suffering.

The objective of our study was to understand the perspectives of people living with life-threatening illness about non-somatic suffering in order to better comprehend this phenomenon.

Methods

Due to the fact that non-somatic suffering is a complex human experience for which in-depth analysis is required, a qualitative methodology (based on grounded theory) was used.34-36 In this field of research on suffering, several studies have used a qualitative design when aiming to understand and explain this phenomenon.37-39 The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Centre-Sud de l’Île-de Montréal (Certificate #VN 17-18-28). All participants signed a consent form stating that their participation was voluntary.

Setting and Recruitment

The study was conducted with individuals receiving home-based palliative care (HBPC) in a highly urbanized setting. Contact information for potential participants was provided by the HBPC team's nurses and physicians. The researchers then contacted those persons to obtain informed consent.

Recruitment was conducted in several phases, following the continuous comparative analysis approach. 40 Sampling and data collection continued until new data became redundant and construct saturation was reached.41,42

Inclusion criteria were: (1) having an illness in the palliative phase, that is, having received a diagnosis of incurable and terminal disease with a predictable length of survival of under a year; (2) being 18 years of age or older; (3) having no cognitive impairment; (4) being able to speak in English or French; and (5) having sufficient energy to participate.

Of all patients referred by the team, only one was not interviewed.

Data Collection

Our design was aimed at gaining a better understanding of end-of-life suffering through two complementary modes of expression: one based on verbal language, and one based on drawing. Artistic methods are increasingly being used to access sensitive material otherwise inaccessible through the more conventional methods of individual interviews or focus groups.43-46 The impacts on results of using drawing are the subject of another publication. 47 Thus, for each participant, data collection consisted of two semi-structured interviews with a drawing session in between. Interviews were audio-recorded and conducted by two research team members (SD, MA) experienced in this mode of data collection. Questions were asked in a non-directive manner, to let participants express themselves as freely as possible. The first interview was focused on getting to know the participant and collecting their illness story, including baseline information about the suffering experienced. During the drawing activity, participants were invited to put on paper elements of their experience related to suffering or non-suffering. This was done in the researcher's absence, to constrain expression as little as possible. The drawings themselves were not analyzed nor compared between subjects, as their use was only intended to help participants better articulate their experience of suffering. The second interview was focused on discussing the meaning given by the participant to what had been put on paper. The two interviews and the drawing activity were conducted either in one continuous session or in two or three separate sessions depending on the participant's preference. At the end of the second interview, a socio-demographic questionnaire was completed. Table 1 presents the questions initially addressed.

Table 1.

Interview Guide.

| Initial Questions |

| I need to know you; what could you tell me about yourself? What could your friends and family say about you? |

| Do you remember how you were told about the illness? What was your first reaction? |

| How did you feel in the days following the diagnosis? |

| If I say the word “suffering” to you, what does it make you think of? What comes to mind? |

| In living through this illness, have you experienced suffering? If so, have you always experienced the same suffering, or has it been greater at certain times? |

| If there were a word (an image) to define (this) suffering, what would it be for you? |

| You talked to me about suffering; are there different types of suffering, in your view? |

| Instructions before the drawing activity |

| As agreed, I would now ask you to draw a picture or shapes (or several, it's up to you) of what suffering means to you, what makes you suffer. The goal isn't to make beautiful drawings. It's simply a matter of putting into images what you feel, what you think. Then we’ll talk about it together. |

| Questions following the drawing activity |

| Could you tell me what you have drawn, illustrated? |

| And, in relation to what you’re going through, what does this drawing mean for you? |

| Conclusion |

| Thank you for this meeting. Before we stop, would you anything else to add; something that we haven't talked about and that you’d like to share? |

As data collection and analysis were simultaneous, purposive theoretical sampling 48 was used to avoid recruiting subjects of similar age, gender, or diagnosis and to broaden the spectrum of experiences studied. Several measures were taken to ensure reflexivity: the interviewers and research team had no prior contact with participants, who were recruited from several different profiles; each interview was followed by a debriefing discussion to identify any bias, and routine journaling was maintained; and all analyses were done by the team, which incorporated many disciplines.

Data Analysis

All interviews were fully transcribed and systematically validated by the interviewer after transcription. 49

The analysis was based on techniques proposed by Miles and colleagues 40 and Paillé and Mucchielli. 35 The first stage involved becoming familiar with the collected material through extensive and repeated readings of the interview transcripts. The second was characterized by open coding as close as possible to the collected material, to allow as many descriptions of the phenomenon of interest to emerge as possible. We then produced a conceptual categorization (axial coding) to create and compare the explanatory codes and categories. Lastly, we grouped the categories within broader conceptual themes describing the phenomenon under study. All analyses were conducted independently by at least two researchers, and discrepancies were brought to the team meetings held regularly throughout the research process to reach consensus among the researchers. Also, at these team meetings, all codes, categories, and selected citations illustrating the emergent conceptualization were discussed. The analysis was carried out using NVivo software (version 12, 2018).

Results

The sample consisted of 11 men and eight women (Table 2). Average age was 64.8 years. Seventeen participants had various forms of cancer; two had end-stage pulmonary fibrosis. The findings from our analyses are described below.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participants.

| Sex: 11 males; 8 females |

| Average age: 64.8 years (range 35-82) |

| Diagnoses |

| Pancreatic cancer: 5 |

| Prostate cancer: 3 |

| Breast cancer: 2 |

| Colon cancer: 2 |

| End-stage pulmonary fibrosis: 2 |

| Lung cancer: 1 |

| Esophageal cancer: 1 |

| Ovarian cancer: 1 |

| Sarcoma: 1 |

| Melanoma: 1 |

| Marital status |

| Living in a couple: 9 |

| Divorced: 6 |

| Single: 4 |

While not denying the existence of somatic suffering, participants tended to assign more importance to non-somatic suffering.

Q: If I say the word “suffering” what does it make you think of?

R: For me, it’ s more psychological suffering than physical. (Participant 1)

First, two categories of non-somatic sufferers emerged: the being enduring the suffering and the being whose agency is constrained by it.

The Being Enduring the Suffering

Suffering is experienced when a person passively endures what is happening. In our data, this experience was synthesized into four dimensions: (1) stupefaction; (2) obsessive affliction; (3) fears; and (4) reaching the breaking point. These were not experienced linearly, as participants could go back and forth among them many times.

From the narratives, there emerges the idea of a first death in the person's existence, conveyed, for example, as a heavy blow to the head.

Q: When you found out you were sick, do you remember how you reacted?

A: It was as if the house – not just a brick – it was as if the house had fallen in on me. (Participant 2)

Besides the shock itself, there is stupefaction, the sensation of unreality, of non-acceptance of the suffering, or of its pure and simple refusal. This shock induces a kind of petrification that blocks the person's capacities.

There’s the news: you’re told you’re sick, that it’s over…. And then suddenly, the visit with the doctor is done. “Go to room 14 for a blood test. Go get your appointments in corridor C.” You get there: “Hello, sir. What day do you want your appointment? Do you need parking?” It gets totally crazy. The pharmacist who starts explaining the drugs I’m going to get…. It all happens within the space of 20 minutes. But it’s because I’m going to die! I don’t care about parking. I didn’t understand anything that happened. I was totally in shock. (Participant 10)

This disabling of the affective life undoubtedly responds to need to protect oneself by not feeling the distress. This great upheaval is caused by the direct confrontation with death and one's own finitude.

Participants recounted many periods of sadness or grief during which they became obsessed with the illness and could not stop thinking about it. One participant compared the persistence of distressing thoughts to swinging in the void, which can be explained by the fact that the obsession is about death, and specifically, one's own death. This anguish is so intense that one participant likened it to a “burial”, much like the position of the dead themselves.

I don’ t think you get used to it [the illness]. I think about it constantly. It never lets go, and you’re always in the void. It’ s always with you. (Participant 2)

It’ s like earth. It’ s as if you’re buried by your suffering. (Participant 4)

Fear was strongly present in the narratives: fear of dying and fear of suffering, to which were attached a fear of the unknown. One participant summarized the basis for the fear of death, which is that, when one dies, one is no longer there. Thus, death represents annihilation. Then there is also the fear of suffering itself. The fear of death is linked to fear of the unknown, which can be likened to fear of losing control. This fear seems to explain a substantial portion of the suffering experienced in apprehension.

Q: Are there things that scare you?

A: Besides dying?

Q: Are you afraid of dying?

A: Yes. A little, but I mean… I’m afraid of not being there anymore. (Participant 2)

Because what we’re afraid of, it was letting me suffer. That’ s what we especially don’ t want, is to suffer. (Participant 8)

You’re going into something for which you have no recipe, no keys, nothing. There’s a very, very big unknown… knowing I’m in a situation that I don’t know how I’ll get through. (Participant 8)

The dimension of reaching the breaking point came out strongly in the statements of the participants, who were suffering because they were at the end of their rope. The feeling of being overwhelmed became so strong that it made people wish for death. Some were exasperated by the numerous treatments they had to undergo. Many reported having reached their breaking point, saying they were no longer able to bear their experience. Thus, the person reaches a state that is at the limit of what they would consider bearable.

Then sometimes I was so fed up. I told my son, “I’m going to open the window and damn well throw it outside!” (Participant 14)

A: Well, I’m tired of going to treatments. It’s exhausting. It’s enough to demoralize the Pope.

Q: Do you know the Pope?

A: No, but I think he’d be fed up, too, even if he believes in God. (Participant 2)

The Being Whose Agency is Constrained

Human beings are, in essence, beings who act. This refers not only to tangible actions, but also to thoughts, emotions, and the work of the mind. When afflicted with a disease that compromises survival, the person is placed, unwillingly, in a state of impossibility to act that “imprisons” them in their body. It borders on a kind of paralysis, in which the subject becomes incapable of thinking and acting in any way, even in relation to things as simple and as primitive as choosing food to eat.

At a certain point, you get worn out. It’ s a full-time job. I think each person has a threshold for where they’ll go, and I’ve gone really far in how I’m getting through all this. (Participant 12)

What is suffering?… It’s not being able to do the things you want to do in life, that you love. To be like a prisoner in your body. (Participant 13)

At that point, the cancer wasn’t painful. So all the pain was in my head. The suffering was mental. I’d just learned I had a fatal diagnosis. I was unable to act, to think…. It was so stupid that… You’re shopping for groceries. You know you have to buy a steak, a potato. You’re in front of the potato, you don’t know whether your left hand or your right hand will pick it up. In the end, you walk out of the store and say no…. tomorrow. (Participant 10)

This notion of imprisonment is imposed by the illness that “disrupts plans,” changing one's life completely. Loss of agency was so serious for some participants that it rendered their life worthless.

This idea of cancer arrived like a bomb that turned my life completely upside down. It wasnV t expected – of course, that kind of thing is never expected. And when it happens to us, we ask ourselves why. It’ s just that we don’ t plan on being sick. (Participant 8)

Q: What’ s the greatest suffering you experienced?

A: [Still overcome:] It’s that all my life I was always in shape. We went to the gym. We biked, we always had activities. We travelled…. at that time, I was becoming “no longer active.”

Q: And what makes this life worth living for you?

A: Oh, it’s worthless… because I no longer have a goal. (Participant 5)

Some participants equated incapacity with their social role, their useful role. For others, to be deprived of agency was to be forced to live, to some extent, another life than the one for which they had existed until then.

It’s the fact that I’m useless. I’d like to contribute to society. I’m so tired. It’s a drag to have nothing to do…. I don’t have the strength to do anything else. (Participant 6)

It’s not that I want to die, but I’m a little tired of not living up to what I…. I have abilities but they’re not being used. I can’t use all my talents that I’d like, or all my skills. (Participant 12)

The Being in Relationship with Others

One more category emerged during our analysis: the being in relationship with others. Because a human being is a relational being, the suffering of people living with life-threatening illness is grounded in their interactions with others, which can become suppressed or transformed in a direction they do not want.

Leaving those they loved, an almost constant suffering, was observed in almost all the participants. It was present even in those who claimed they were not suffering. This is residual suffering, impossible to lessen, because it is linked to ties woven throughout life. Some participants explained they were not afraid of death, but worried that the prospect of disappearing meant abandoning their loved ones.

What’s hard… [Stops, very emotional. Crying:] is causing pain in those you love. I’m finding that hard. We’ll all leave someday. But to leave those we love, oh hell, that’s hard! (Participant 18)

Another aspect of suffering emerging from relationship with others was expressed as a feeling of loneliness. This loneliness can occur even in people who feel surrounded, as if the loneliness comes from the suffering itself.

One of the major causes of suffering is moral loneliness. Not physical loneliness, moral loneliness. (Participant 1)

The solitude, the absence of people. All this solitude, this long solitude, it’ s heavy sometimes. It’ s heavy all the time. You cry alone. You laugh alone. You hurt alone. You take pills alone. Everything like that, all alone. (Participant 10)

The phenomenon of loneliness can also be comprehended in the way loved ones react to the impending death of one of their own. Those who feel unwelcome in this final stage of life may react by cutting themselves off from their loved ones. The perceived change in the relationship can cause suffering.

I ask myself, why don’ t they understand? I have two sons who have problems with “my” disease. The younger one especially, he has a lot of trouble accepting my condition. He steps back and puts up a kind of barrier. He’ s cold. He doesn’ t understand. (Participant 4)

A Conceptualization of non-Somatic Suffering

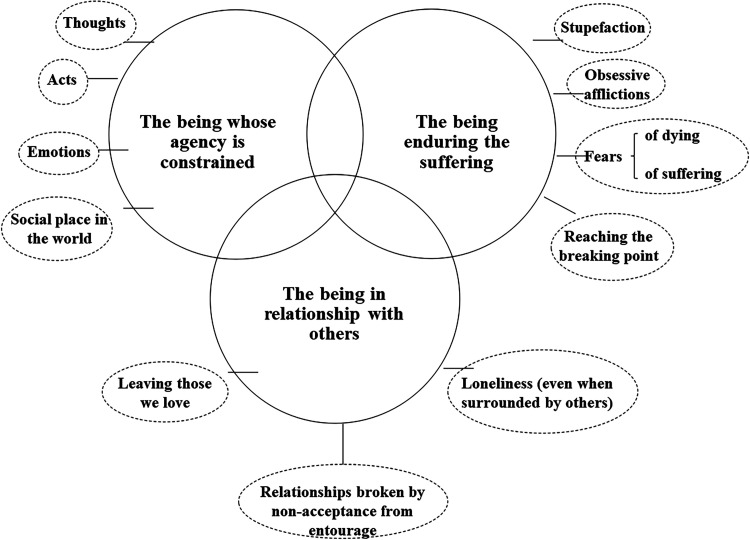

Based on these interviews, we were able to comprehend non-somatic suffering by constructing a diagram inspired by the writings of Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005), a French philosopher inspired by phenomenology who worked largely in the human and social sciences. Non-somatic suffering falls into three distinct but interrelated categories, as shown in Figure 1: the being enduring the suffering, the being whose agency is constrained, and the being in relationship with others. The proposed conceptualization of non-somatic suffering is influenced by Ricoeur's ideas in his philosophy of the will, illustrated in diverse human potentials such as action, speech, and memory. 50

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of non-somatic suffering caused by serious illness, inspired by Ricoeur.

Discussion

Our results suggest non-somatic suffering can be understood as an oscillation between acting and being acted upon, to which it is useful to integrate the dimension of relationship to others, which appeared fundamental in the experience of the people interviewed. This conceptualization is influenced by the ideas of Ricoeur, who also situates suffering in the self–other axis because, in his view, suffering isolates and separates. 51

This conceptualization retains several elements of Cassell's proposals,8,52 but orders them differently. The constraints on agency in our model could be likened to the attack on integrity specific to Cassell's model, whereas the issue of threat is found in the fears we now identify in the category of enduring the suffering. However, a new constituent of suffering appears, in the phenomenon of reaching the breaking point, which is at the heart of the proposed conceptualization. Thus, suffering is the experience of not being able to go on like this (being fed up), 53 which translates into an alteration of temporality. This is why the sufferer may come to prefer death to life. In effect, when in despair, life feels more impossible than death. Reaching the breaking point can also signify arrival at a threshold beyond which the person enters into a suffering they consider intolerable. This notion of threshold is also evoked in the model of Beng and colleagues, which posits that there is no suffering until this threshold is crossed. 54 This notion could be of paramount importance when thinking about the effects of factors related to the illness or to the treatment that could, in some cases, push someone beyond their limit and precipitate them into a state of suffering that requires careful management. 55 While not mentioned in Beng's model, it may well be that moving from active management to palliative care profoundly changes this threshold and that patients suffer precisely because of this change.

On the other hand, while there is a threat component included in this area under the heading of fears, it is much less present than in Cassell's model. 8 This may, at least as far as the somatic aspect of suffering is concerned, be related to the fact that several participants reported that their pain was very well controlled by the care they were receiving.

We might have the impression that the being who is no longer acting always refers to the being who is enduring suffering, on the assumption that action prevents suffering. However, we might also speculate as to whether there is a more suffering side to action. In particular, we recall this interpretation from Ricoeur, who stipulates that suffering “speaks or cries out, and this is not incidental, but attests to the persistence and destruction at the same time, in it [the suffering], of the acting and speaking man”. 56 Thus, suffering is also expressed in action which, for Ricoeur, is a crying out to others.

The category in our proposed conceptualization that concerns the relationship with others appears central and largely unexplored. Since humans are, by definition, gregarious beings, they suffer with and through others. This category in our conceptualization of suffering brings us closer to what Fridh and colleagues called interpersonal suffering, which is experienced through loss, sadness, and worry about family members and their future. 57

Krikorian and colleagues likewise suggested that the acceptance of dying is related to three conditions: personality, social support, and the spiritual or religious domain. 23 For those authors, the spiritual dimension refers to a connection the person makes with the present moment, self, others, nature, or the sacred. In our study, the religious dimension was not directly present as such. However, the spiritual dimension actualized by connection to others might reflect, in our participants, some connection to a religious dimension. In any case, this aspect of our results should be further explored in future research on the actions and postures that people develop in response to suffering.

This study presents certain limitations. The extent to which results could be transferable to a rural or more ethnically diverse population remains unknown. It is possible that persons other than those who participated in this study might define suffering differently. Also, our recruitment relied on identification of participants via the HBPC nurses and physicians, which may have influenced the patient type, in the sense that only “friendly” patients were recruited. This real possibility was counterbalanced by requests to recruit patients from marginalized groups. Another limitation is the cross-sectional and not longitudinal nature of this research. Many participants expressed the shifting nature of their relationship to suffering, and it would be interesting to access this through longitudinal studies in which participants would be met several times during their illness.

In conclusion, this study broadens and deepens our understanding of the non-somatic suffering of people with terminal illness. This study informs practice in the sense that every caregiver confronted with suffering should consider what the non-somatic causes of suffering might be in order to respond to them. At the policy level, this study argues for including more humanities-trained caregivers in palliative care teams. Finally, future research should focus on the entanglement of non-somatic sources of suffering with the strictly biological aspects of the diseases we manage.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Jean Grondin for his reading of the manuscript and his insightful comments. They also thank Corinne Boussin, Michelle Gauthier, Lyne Vezina, Valérie Therrien and Dr Stephen di Tomasso for their assistance in recruiting participants. Thanks also to Donna Riley for translation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Blanchard Family Chair for Teaching and Research in Palliative Car (no grant number); the Dr Sadok Besrour Chair in Family Medicine (no grant number); and the Fondation Jacques-Bouchard (no grant number).

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1.van Hooft S. Suffering and the goals of medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 1998;1(2):125-131. doi: 10.1023/a:1009923104175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansen L, Sulmasy D. Proportionality, terminal suffering and the restorative goals of medicine. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(4–5):321-337. doi: 10.1023/a:1021209706566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beng TS, Guan NC, Jane LE, Chin LE. Health care interactional suffering in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(3):307-314. doi: 10.1177/1049909113490065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Den Hartogh G. Suffering and dying well: on the proper aim of palliative care. Med Health Care Philos. 2017;20(3):413-424. doi: 10.1007/s11019-017-9764-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrahm J. The role of the clinician in palliative medicine. JAMA. 2000;283(1):116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tate T, Pearlman R. What we mean when we talk about suffering—and why ERIC cassell should not have the last word. Perspect Biol Med. 2019;62(1):95-110. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2019.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VanderWeele TJ. Suffering and response: directions in empirical research. Soc Sci Med. 2019;224:58-66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(11):639-645. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis J, Cobb M, O’Connor T, Dunn L, Irving G, Lloyd-Williams M. The meaning of suffering in patients with advanced progressive cancer. Chronic Illn. 2015;11(3):198-209. doi: 10.1177/1742395314565720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daneault S, Lussier V, Mongeau S, et al. The nature of suffering and its relief in the terminally ill: a qualitative study. J Palliat Care. 2004;20(1):7-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montoya-Juarez R, Garcia-Caro MP, Campos-Calderon C, et al. Psychological responses of terminally ill patients who are experiencing suffering: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffee CM. Pain versus suffering: a distinction currently without a difference. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:175-178. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2019-105902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffee C. An intellectual history of suffering in the encyclopedia of bioethics, 1978–2014. Med Humanit. 2021;47:274-282. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2019-011800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards SD. Three concepts of suffering. Med Health Care Philos. 2003;6(1):59-66. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537117643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beng TS, Yun LA, Yi LX, et al. The experiences of suffering of end-stage renal failure patients in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):401-410. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.03.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lethborg C, Aranda S, Cox S, Kissane D. To what extent does meaning mediate adaptation to cancer? The relationship between physical suffering, meaning in life, and connection to others in adjustment to cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5(4):377. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruijs CD, Kerkhof AJ, van der Wal G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Symptoms, unbearability and the nature of suffering in terminal cancer patients dying at home: a prospective primary care study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renz M, Reichmuth O, Bueche D, et al. Fear, pain, denial, and spiritual experiences in dying processes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(3):478-491. doi: 10.1177/1049909117725271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chochinov H, Cann B. Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S103-SS15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5520-5525. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.08.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753-762. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70153-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chochinov HM, McClement SE, Hack TF, et al. Health care provider communication: an empirical model of therapeutic effectiveness. Cancer. 2013;119(9):1706-1713. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krikorian A, Limonero JT, Maté J. Suffering and distress at the end-of-life. Psychooncology. 2012;21(8):799-808. doi: 10.1002/pon.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li M, Watt S, Escaf M, et al. Medical assistance in dying - implementing a hospital-based program in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2082-2088. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1700606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Rabadi L, LeBlanc M, Bucy T, et al. Trends in medical Aid in dying in oregon and Washington. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198648. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuhn A, Holmes S, Kelly M, Just A, Shaw J, Wiebe E. Experiences and perspectives of people who pursued medical assistance in dying: qualitative study in vancouver, BC. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(9):e380-e386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiebe E, Shaw J, Green S, Trouton K, Kelly M. Reasons for requesting medical assistance in dying. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(9):674-679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Best M, Aldridge L, Butow P, Olver I, Webster F. Conceptual analysis of suffering in cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):977-986. doi: 10.1002/pon.3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anquinet L, Rietjens J, van der Heide A, et al. Physicians’ experiences and perspectives regarding the use of continuous sedation until death for cancer patients in the context of psychological and existential suffering at the end of life. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):539-546. doi: 10.1002/pon.3450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Cadet TJ, Ferral AJ, Ko EJ, Thompson B, Mishra SI. Moving closer to death: understanding psychosocial distress among older veterans with advanced cancers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(12):5919-5931. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05452-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankl V. Man’s Search for Meaning: An introduction to Logotherapy. Holt Rinehart & Winston; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricoeur P. Soi-même Comme un Autre. Seuil; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricoeur P. La souffrance n’est pas la douleur. In: Kaenel JV, Ajchenbaum-Boffety B, eds. Souffrances: Corps et âme, épreuves Partagées. Autrement; 1994:58-70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charmaz K. Grounded theory : objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. (2nd Edn). Sage; 2000:509-535. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paillé P, Mucchielli A. L’analyse Qualitative en Sciences Humaines et Sociales. Paris, France: Armand Colin; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daneault S. The essential role of qualitative research in building knowledge on health. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018;37(2):105-107. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malhotra C, Malhotra R, Bundoc F, et al. Trajectories of suffering in the last year of life Among patients With a solid metastatic cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(11):1-8. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iskandar AC, Rochmawati E, Wiechula R. Patient’s experiences of suffering across the cancer trajectory: a qualitative systematic review protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(2):1037-1042. doi: 10.1111/jan.14628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamm-Faber TE, Engels Y, Vissers KCP, Henssen D. Views of patients suffering from failed back surgery syndrome on their health and their ability to adapt to daily life and self-management: a qualitative exploration. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook. Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morse JM. Data were saturated …. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(5):587-588. doi: 10.1177/1049732315576699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews Are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591-608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holloway I, Todres L. Thinking differently: challenges in qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2007;2(1):12-18. doi: 10.1080/17482620701195162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knowles JG CA. Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parsons JA, Boydell KM. Arts-based research and knowledge translation: some key concerns for health-care professionals. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(3):170-172. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.647128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rieger K, Schultz AS. Exploring arts-based knowledge translation: sharing research findings through performing the patterns, rehearsing the results, staging the synthesis. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(2):133-139. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azri M, Ummel D, Côté A, et al. Better understanding suffering: drawings’ potential for generating deeper data on terminal illness (Submitted). 2022.

- 48.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kvale S. Doing Interviews. Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grondin J. Paul Ricœur. Presses Universitaires de France, Que sais-je? n° 3952; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svandra P. Douleur et souffrance, sur les pas de paul ricœur. Soins Psychiatrie. 2012;33(282):12-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassell EJ. Recognizing suffering. Hastings Center Report. 1991;21(3):24-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porée J. Le sens temporel de la souffrance. L’Encéphale. 2015;41(4):S22 − S2S8. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(15)30003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beng TS, Guan NC, Seang LK, et al. The experiences of suffering of palliative care patients in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):45-56. doi: 10.1177/1049909112458721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daneault S. Souffrance et Médecine. Québec, QC: Les Presses de l’Université du Québec (PUQ); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worms F. Souffrant, agissant et vivant. In: Zaccai-Reyners N, Marin C, eds. Souffrance et Douleur. Autour de Paul Ricœur. Presses Universitaires de France; 2013:35-46. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fridh I, Kenne Sarenmalm E, Falk K, et al. Extensive human suffering: a point prevalence survey of patients’ most distressing concerns during inpatient care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(3):444-453. doi: 10.1111/scs.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]