Abstract

Objective

There is no medical treatment proven to limit abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) progression. This systematic review aimed to summarise available trial evidence on the efficacy of pharmacotherapy in limiting AAA growth and AAA-related events.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed to examine the efficacy of pharmacotherapy in reducing AAA growth and AAA-related events. Pubmed, Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), and the Cochrane library were searched from March, 1999 to March 29, 2022. AAA growth (mm/year) in the intervention and control groups was expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). The results of AAA growth were expressed as mean difference (MD) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events.Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. Forest plots were created to show the pooled results of each outcome.

Outcomes

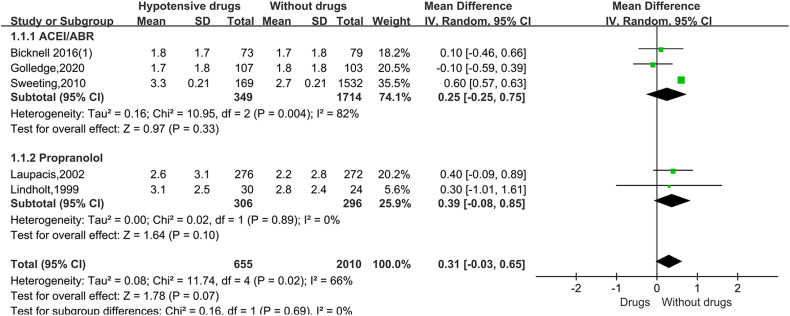

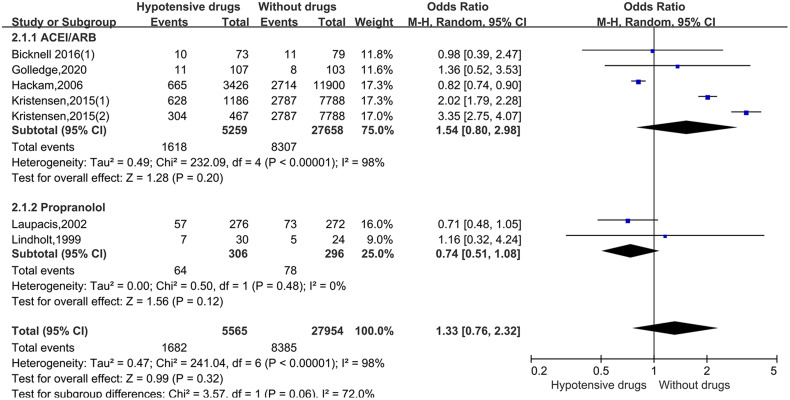

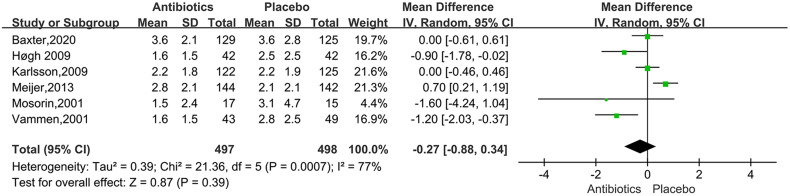

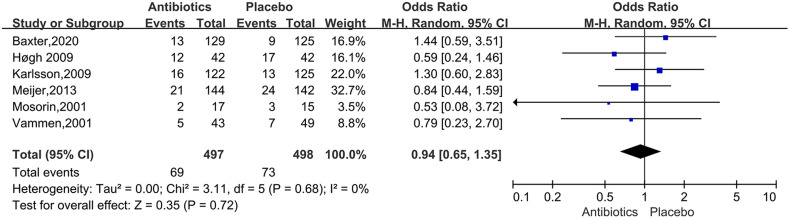

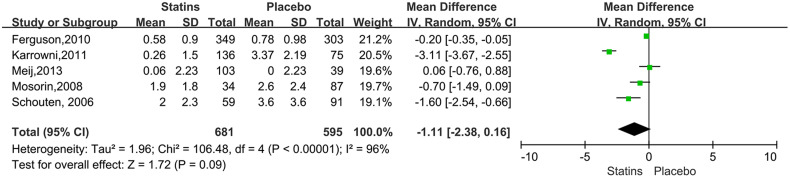

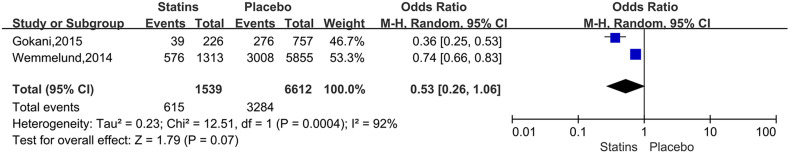

A total of 1373 articles were found in different databases according to the search strategy, and 10 articles were identified by hand searching. A total of 26 articles were included in our systematic review after the screening. For the studies of metformin, the meta-analysis demonstrated that metformin use was associated with a lower AAA growth rate (MD: −0.81 mm/y, 95% CI: −1.19 to −0.42, P < 0.0001, I2 = 87%), Metformin use also was related to the lower rates of AAA-related events (OR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.76, P = 0.0007, I2 = 60%). The hypotensive drugs of the studies mainly included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARB), and propranolol. The overall meta-analysis of blood pressure-lowering drugs reported no significant effect in limiting the AAA growth (MD: 0.31mm/year, 95%CI: −0.03 to 0.65, P = 0.07, I2 = 66%) and AAA-related events (OR: 1.33, 95%CI: 0.76 to 2.32, P = 0.32, I2 = 98%), In the subgroup analysis of the hypotensive drugs, the ACEI/ARB and propranolol also showed no significant in reducing the AAA growth and AAA-related events. The meta-analysis of the antibiotics demonstrated that the antibiotics were not associated with a lower AAA growth rate (MD: −0.27 mm/y, 95% CI: −0.88 to 0.34, P = 0.39, I2 = 77%) and AAA-related events (OR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.35, P = 0.72, I2 = 0%). The results of statins also showed no significant effect in limiting AAA growth (MD: −1.11mm/year, 95%CI: −2.38 to 0.16, P = 0.09, I2 = 96%) and AAA-related events (OR: 0.53, 95%CI: 0.26 to 1.06, P = 0.07, I2 = 92%).

Conclusion

In conclusion, effective pharmacotherapy for AAA was still lacking. Although the meta-analysis showed that metformin use was associated with lower AAA growth and AAA-related events, all of the included studies about metformin were cohort studies or case-control studies. More randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed for further verification.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, Pharmacotherapy, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is characterized by permanent, localized dilations of the abdominal aorta, defined as having diameters 1.5 times greater than normal. 1 Most patients with AAA are asymptomatic until the aneurysm rupture, while the rupture can bring high mortality. The ruptured AAA, symptomatic AAA, larger AAA(>5.5 cm), and the AAA with rapid expansion rate are recommended to be performed either by endovascular aortic repair(EVAR) or open repair surgery. Without repair, AAAs usually continue to enlarge, and increasing diameter also increases the risk of rupture. 2 Thus, the drugs which can effectively limit the rupture risk and growth of AAA are needed.

Clinical studies have been performed to verify the efficacy of drugs to slow AAA growth or rupture risk. Metformin is the most well-established diabetes treatment, and it has been shown to limit the matrix remodeling and inflammation in AAA pathological mechanisms. 3 Blood pressure plays a vital role in the AAA progression, 4 and lower blood pressure is related to slower AAA growth 5 or rupture. 6 Blood pressure-lowering drugs are commonly used to manage AAA. Studies about AAA treated by antihypertensive medications have been reported in recent years, while not all drugs can inhibit AAA growth. 7 The antibiotics have been reported to reduce the AAA growth through multiple mechanisms, including anti-infective effects, anti-inflammatory and the downregulation of extracellular matrix remodelling. 8 Statins can promote the regression of atherosclerotic plaques and reduce vascular inflammation. 9 They have also been shown to reduce collagen breakdown by regulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases, 10 statin therapy is associated with a reduction in AAA progression. 11 In addition to these medications, other drugs on AAA growth have also been reported, such as stem cells, 12 fenofibrate, 13 and ticagrelor, 14 but the number of these studies is relatively small.

With the emergence of a number of pharmacotherapy clinical trials on AAA, relevant meta-analysis needs to be updated and summarized. This systematic review aimed to summarise available trial evidence on the efficacy of drugs on AAA growth and AAA-related clinical events.

Method

Literature Search Strategy

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 15 Pubmed, Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), and the Cochrane library were searched from March 1, 1999 to March 29, 2022. The term “aortic aneurysm, abdominal” was used across all fields. Focused searches including the terms “Drug Therapy” OR “Metformin” OR “Antihypertensive agent’OR “Antibiotic agent” OR “Statins’ were used to identify additional studies of relevance. Titles and abstracts were screened to identify studies for inclusion. If the suitability of an article was uncertain, the full text was reviewed.

Eligible Criteria

Two reviewers (Zhixiang Su, and Jianming Guo) independently reviewed all the articles. Any disagreements were settled by a third independent reviewer (Yongquan Gu). Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies were included if they met the following criteria: Studies included AAA patients treated by drugs; AAA growth rate and AAA-related events (AAA rupture, repair, or related death) had been reported. Case reports and case series were excluded. Conference abstracts were considered if sufficient data were available for analysis.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors extracted data independently, checked for consistency, and negotiated with a third party in the event of ambiguity. The major data extracted included: first author, year of publication, study design, baseline diameter of AAA, sample size, follow-up time, AAA growth rate, and AAA-related events. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was applied to evaluate the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials. 16 The methodological quality of cohort studies and case control studies was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/ clinical_epidemiology/ oxford.asp). Two authors completed data extraction and quality assessment independently. The discrepancy was eliminated after the discussion.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (version 5.4). A meta-analysis was performed comparing AAA growth and AAA-related events in the intervention and control groups. AAA growth (mm/year) in the intervention and control groups was expressed as mean and standard deviation(SD), the results of AAA growth were expressed as mean difference(MD) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events. Heterogeneity was quantitatively analyzed by I2 and the significance level was set to 50%, which means the heterogeneity is significant among the studies when I2 > 50%. The fixed effect model was used when there is no statistical heterogeneity. Analysis outcomes were performed with the random effects model when the statistical heterogeneity is significant. Eventually, we show the results with forest plots.

Results

Search, Screening, and Full-Text Review

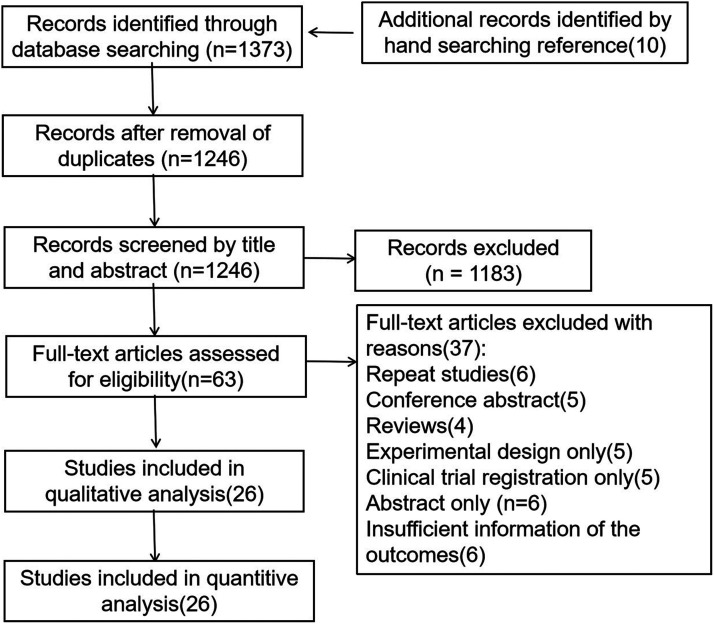

A total of 1373 articles were found in different databases according to the search strategy, and 10 articles were identified by hand-searching, 1246 articles were retained after the removal of duplicates. Of the 1246 articles screened, 1183 were excluded, and 63 passed screening based on the title and abstract. Following full-text articles, 37 articles were excluded: repeated studies (6), conference abstract (5), reviews (4), experimental design only (5), clinical trial registration only (5), abstract only (6), insufficient information on AAA growth rate (6). A total of 26 articles were included in our systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram illustrating the selection of the included trials.

Study Characteristics

A total of 26 studies were included. 10 studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 13 studies were cohort studies, and 3 studies were case-control studies. Among them, 6 trials were for metformin (Unosson 2020, 17 Itoga 2018, 18 Golledge 2018, 19 Katrine 2017, 20 Golledge 2017, 21 Fujimura 2016, 3 ) 7 trials were for blood pressure-lowering drugs (Golledge 2020, 22 Bicknell 2016, 23 Kristensen 2015, 24 Sweeting 2010, 25 Hackam 2006, 26 Laupacis 2002, 27 Lindholt 1999, 28 ) 6 trials were for antibiotics (Baxter2020, 29 Meijer 2013, 30 Karlsson 2009, 31 Høgh 2009, 32 Vammen 2001, 33 Mosorin 2001, 34 ) 7 trials were for statins (Gokani 2015, 35 Wemmelund 2014, 36 Meij 2013, 37 Ferguson 2010, 38 Karrowni2011, 39 Mosorin 2008, 40 Schouten 2006. 41 ) The first author, year of publication, study design, baseline diameter of AAA, sample size, follow-up time, AAA growth rate, and AAA-related events were included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies.

| Country | Design | Drug | Baseline Diameter (mm) | Sample size | Follow-up Time(year) | AAA growth mm (SD) per year | P-value | AAA-related events | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin | ||||||||||

| Unosson, 2020 17 | Sweden | RCS | Metformin(T2DM) | 36.5 (5.9) | 65 | 3.2 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Without metformin(T2DM) | 37.5 (6.0) | 33 | 1.6 (1.4) | |||||||

| No diabetes | 38.2 (6.1) | 428 | 2.3 (2.2) | |||||||

| Itoga, 2018 18 | United States | RCS | Metformin | 38.0 (7.1) | 5492 | 4.2(2.6) | 1.2 (1.9) | P < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 8342 | 1.5 (2.2) | ||||||||

| Golledge, 2018 19 | Australia | PCS | No diabetes | 46.6(11.5) | 846 | 2.5(3.3) | NA | NA | 378 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 45.3(10.0) | 105 | 2.2(2.9) | 44 | ||||||

| Diabetes prescribed metformin | 43.4(10.3) | 129 | 3.2(3.3) | 32 | ||||||

| Katrine, 2017 20 | Denmark | CC | Diabetes prescribed metformin | NA | 1152 | 5 | NA | NA | 81 | NA |

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 1875 | 184 | ||||||||

| Golledge, 2017 21 | Australia and New Zealand | RCS(1) | Diabetes prescribed metformin | 36.9(6.3) | 118 | 3.6(2.4) | 1.03(2.68) | 0.012 | NA | NA |

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 99 | 1.60(2.94) | 0.217 | |||||||

| No diabetes | 1140 | 1.62(2.45) | ||||||||

| RCS(2) | Diabetes prescribed metformin | 40.9(7.3) | 39 | 2.9(2.6) | 1.40(2.99) | 0.004 | NA | NA | ||

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 30 | 2.18(2.96) | 0.514 | |||||||

| No diabetes | 218 | 2.55(3.04) | ||||||||

| RCS(3) | Diabetes prescribed metformin | NA | 16 | NA | 0.37(1.28) | 0.018 | NA | NA | ||

| Diabetes not prescribed metformin | 3 | 0.95(1.18) | 0.693 | |||||||

| No diabetes | 34 | 1.46(1.52) | ||||||||

| Fujimura, 2016 3 | USA | RCS | Metformin(T2DM) | NA | 43 | 2.6(0.3) | 0.4(0.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| Without metformin(T2DM) | 15 | 1.7(0.5) | ||||||||

| Hypotensive drugs | ||||||||||

| Golledge, 2020 22 | Australia | RCT | Telmisartan | 43.3 (4.8) | 107 | 2 | 1.7(1.8) | 0.663 | 11 | 0.52 |

| Placebo | 43.1 (5.2) | 103 | 1.8(1.8) | 8 | ||||||

| Bicknell, 2016 23 | London | RCT | Perindopril | 40.5 (6.5) | 73 | 2 | 1.8(1.7) | 0.78 | 10 | 0.85 |

| Amlodipine | 40.3 (6.9) | 72 | 1.8(1.7) | 0.68 | 11 | |||||

| Placebo | 40.6 (6.7) | 79 | 1.7(1.8) | 11 | ||||||

| Kristensen, 2015 24 | Denmark | RCS | ACEIs | NA | 1186 | 5 | NA | NA | 628 | NA |

| ARB | NA | 467 | 304 | |||||||

| No ACEIs/ARB | NA | 7788 | 2787 | |||||||

| Sweeting, 2010 25 | London | RCS | ACEIs | 44.1 (7.4) | 169 | 5.3 | 3.3(0.21) | 0.009 | NA | NA |

| No ACEIs | 42.7 (6.8) | 1532 | 2.7(0.21) | |||||||

| Hackam, 2006 26 | Canada | CC | ACEI | NA | 3426 | 10 | NA | NA | 665 | 0.008 |

| No ACEI | 11900 | 2714 | ||||||||

| Laupacis, 2002 27 | Canada | RCT | Propranolol | 3.92 (0.54) | 276 | 2.5(1.1) | 2.6(3.1) | 0.11 | 57 | NA |

| Placebo | 3.94 (0.53) | 272 | 2.2(2.8) | 73 | ||||||

| Lindholt, 1999 28 | Denmark | RCT | Propranolol | NA | 30 | NA | 3.1(2.5) | 0.7 | 7 | NA |

| Placebo | 24 | 2.8(2.4) | 5 | |||||||

| Antibiotics | ||||||||||

| Baxter, 2020 29 | United States | RCT | Doxycycline | 4.3 (0.4) | 129 | 2 | 3.6(2.1) | 0.93 | 13 | 0.41 |

| Placebo | 4.3 (0.4) | 125 | 3.6(2.8) | 9 | ||||||

| Meijer, 2013 30 | Netherlands | RCT | Doxycycline | 43.0 (5.5) | 144 | 1.5 | 2.8(2.1) | 0.016 | 21 | NA |

| Placebo | 43.1 (5.5) | 142 | 2.1(2.1) | 24 | ||||||

| Karlsson, 2009 31 | Sweden | RCT | Azithromycin | 40(6.1) | 122 | 1.5 | 2.2(1.8) | 0.85 | 16 | NA |

| Placebo | 40.3(5.2) | 125 | 2.2(1.9) | 13 | ||||||

| Høgh 2009 32 | Denmark | RCT | Roxithromycin | 38.14 (5.7) | 42 | 5.27(1.99) | 1.6(1.5) | 0.055 | 12 | 0.337 |

| Placebo | 37.12 (5.3) | 42 | 2.5(2.5) | 17 | ||||||

| Vammen, 2001 33 | Denmark | RCT | Roxithromycin | 38.1(5.7) | 43 | 2 | 1.6(1.5) | 0.02 | 5 | NA |

| Placebo | 36.9(5.1) | 49 | 2.8(2.5) | 7 | ||||||

| Mosorin, 2001 34 | Finland | RCT | Doxycycline | 32.4(8.9) | 17 | 1.5 | 1.5(2.4) | NA | 2 | NA |

| Placebo | 35.3(7.4) | 15 | 3.1(4.7) | 3 | ||||||

| Statins | ||||||||||

| Gokani, 2015 35 | United Kingdom | RCS | Stains | 67 | 226 | 7 | NA | NA | 39 | NA |

| No statins | 68 | 757 | 276 | |||||||

| Wemmelund, 2014 36 | Canada | CC | Statins | NA | 1313 | 12 | NA | NA | 576 | NA |

| No-statins | 5855 | 3008 | ||||||||

| Meij, 2013 37 | Netherlands | RCS | Statins | 43.4 (5.5) | 103 | NA | 0.06(2.23) | 0.89 | NA | NA |

| placebo | 42.2 (5.5) | 39 | 0(2.23) | |||||||

| Karrowni, 2011 39 | United States | RCS | Statin | 40.6(5.2) | 136 | 1 | 0.26(1.50) | <0.0001 | NA | NA |

| Placebo | 40.2(4.5) | 75 | 3.37(2.19) | |||||||

| Ferguson, 2010 38 | Australia | RCS | Statins | 34.9(3.34) | 349 | 6 | 0.58(0.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| Placebo | 33.5(4.1) | 303 | 0.78(0.98) | |||||||

| Mosorin, 2008 40 | Finland | RCS | Statins | 38.7(7.0) | 34 | 3.6(2.2) | 1.9(1.8) | 0.27 | NA | NA |

| Placebo | 39.3(6.3) | 87 | 2.6(2.4) | |||||||

| Schouten, 2006 41 | Netherlands | RCS | Statins | 40 (8.5) | 59 | 5.9(8.9) | 2.0(2.3) | 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Placebo | 37 (7.0) | 91 | 3.6(3.6) | |||||||

RCS:Retrospective cohort study, T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, PCS: Prospective cohort study, CC:Case contral study, RCT: Randomised controlled trial, ACEIs: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,ARBs: Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers,NA:not applicable

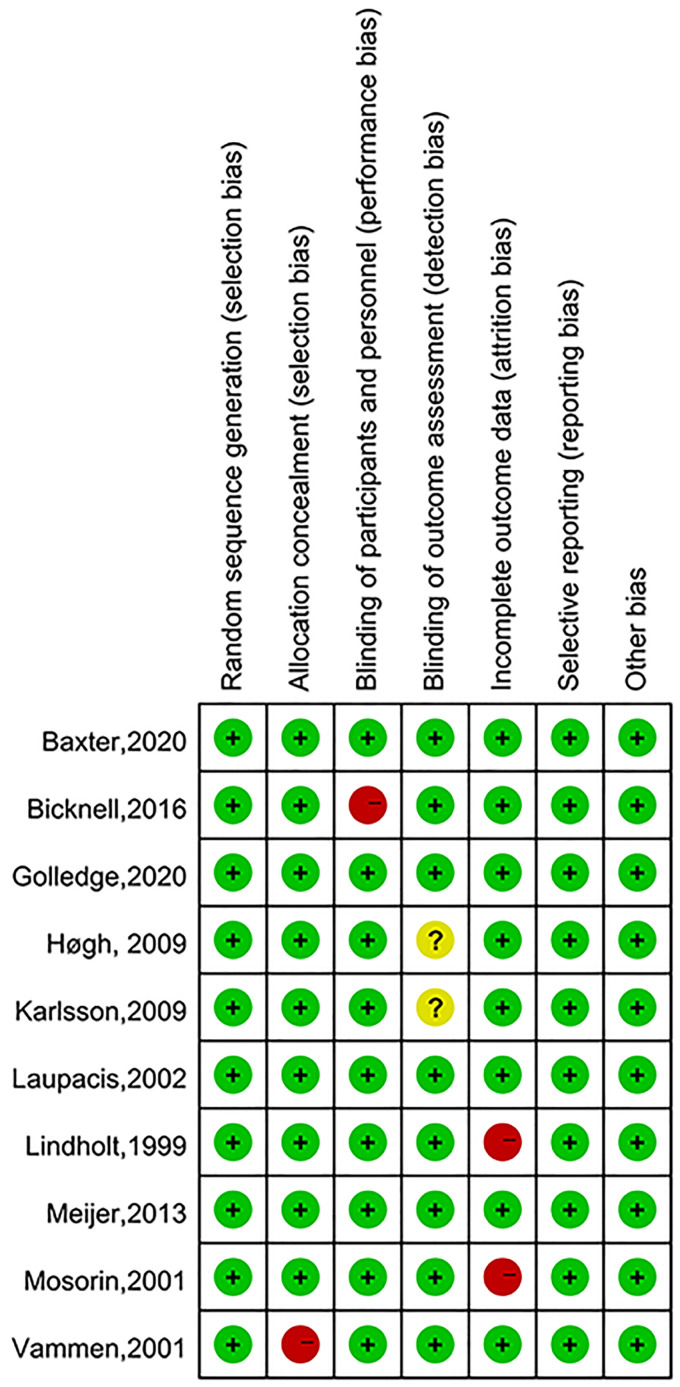

Risk of Bias

The cohort studies and case control studies were deemed to have moderate to high quality(NOS score≥7) (Table 2). The overall risk of bias for RCTs was judged to be low (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Quality Assessment of Cohort Studies and Case Control Studies.

| Cohort studies | Representativeness of exposed cohort (1) | Selection of nonexposed cohort (1) | Ascertainment of exposure(1) | Absence of outcome at start of study (1) | Comparability of cohorts(2) | Outcome assessment (1) | Length of follow-up(1) | Adequacy of follow-up (1) | Risk of score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unosson, 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Itoga, 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Golledge, 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Golledge,2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Fujimura, 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kristensen, 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Sweeting, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Gokani, 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Meij, 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Karrowni, 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Ferguson, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Mosorin, 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Schouten, 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Case-control studies | Case definition(1) | Representativeness of Cases(1) | Selection of controls(1) | Definition of controls(1) | Comparability of cases and controls(2) | Ascertainment of Exposure(1) | Consistent exposure Ascertainment(1) | Nonresponse rate(1) | Risk of score |

| Katrine, 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Hackam, 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wemmelund, 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

Score per the Cochrane risk of bias tool for Bicknell et al and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the case-control and cohort studies. A Newcastle[1]Ottawa Scale score ≧8 indicates low risk of bias, 6-7 indicates moderate risk of bias, and ≦5 indicates high risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Meta-Analysis of Outcomes

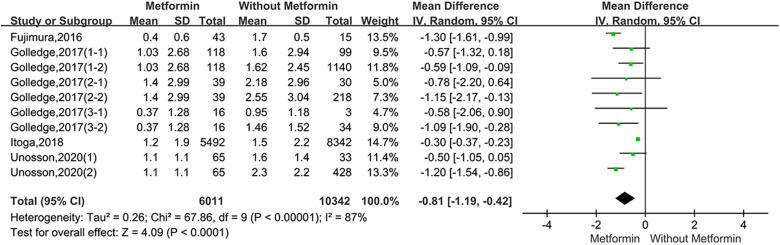

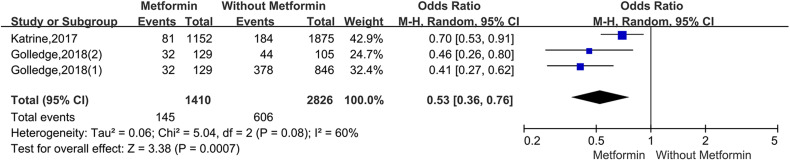

For the studies of metformin, meta-analysis demonstrated that metformin use was associated with a lower AAA growth rate (MD: −0.81 mm/y, 95%CI: −1.19 to −0.42, P < 0.0001, I2 = 87%) (Figure 3). Metformin also was related to the lower rates of AAA-related events(OR: 0.53, 95%CI: 0.36 to 0.76, P = 0.0007, I2 = 60%) (Figure 4). The hypotensive drugs of the studies mainly included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARB), and propranolol, the overall meta-analysis of blood pressure-lowering drugs reported no significant effect in limiting the AAA growth (MD: 0.31mm/year, 95%CI: −0.03 to 0.65; P = 0.07, I2 = 66%) and AAA-related events (OR: 1.33, 95%CI: 0.76 to 2.32, P = 0.32, I2 = 98%), In the subgroup analysis of the hypotensive drugs, the ACEI/ARB and propranolol also showed no significant in reducing the AAA growth and AAA-related events (Figures 5 and 6). The meta-analysis of the antibiotics demonstrated that the antibiotics were not associated with a lower AAA growth rate (MD: −0.27 mm/y, 95%CI: −0.88 to 0.34, P = 0.39, I2 = 77%) (Figure 7) and AAA-related events (OR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.35, P = 0.72, I2 = 0%) (Figure 8). The results of statins also showed no significant effect in limiting the AAA growth (MD: −1.11mm/year, 95%CI: −2.38 to 0.16, P = 0.09, I2 = 96%) (Figure 9) and AAA-related events(OR:0.53, 95%CI: 0.26 to 1.06, P = 0.07, I2 = 92%) (Figure 10).

Figure 3.

Forrest plot summarising the effect of metformin on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Shown is the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. MD is the mean difference in abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate (mm/year) between participants who were prescribed metformin and participants who were without metformin. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect. (Golledge, 2017(1-1) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus diabetes not prescribed metformin in Golledge,2017(Cohort1), Golledge, 2017 (1-2) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus no diabetes in Golledge,2017 (Cohort1); Golledge, 2017(2-1) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus diabetes not prescribed metformin in Golledge,2017(Cohort2), Golledge,2017(2-2) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus no diabetes in Golledge, 2017(Cohort2); Golledge, 2017(3-1) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus diabetes not prescribed metformin in Golledge,2017(Cohort3), Golledge,2017(3-2) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus no diabetes in Golledge,2017(Cohort3); Unosson,2020(1) represent diabetes prescribed metformin versus diabetes not prescribed metformin; Unosson,2020(2) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus no diabetes).

Figure 4.

Forrest plot summarising the metformin on abdominal aortic aneurysm-related clinical events (AAA rupture, repair or related death). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect. (Golledge,2018(2) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus diabetes not prescribed metformin, Golledge, 2018(1) represents diabetes prescribed metformin versus no diabetes).

Figure 5.

Forrest plot summarising the effect of hypotensive drugs on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Shown is the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. MD is the mean difference in abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate (mm/year) between participants who received hypotensive drugs and participants who did not receive certain hypotensive drugs. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect. ACEI(angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) ARB(angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers).

Figure 6.

Forrest plot summarising the hypotensive drugs on abdominal aortic aneurysm-related clinical events (AAA rupture, repair or related death). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect.

Figure 7.

Forrest plot summarising the effect of antibiotics on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Shown is the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. MD is the mean difference in abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate (mm/year) between participants who received antibiotics and participants who did not receive certain antibiotics. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect.

Figure 8.

Forrest plot summarising the antibiotics on abdominal aortic aneurysm-related clinical events (AAA rupture, repair or related death). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect.

Figure 9.

Forrest plot summarising the effect of statins on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Shown is the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. MD is the mean difference in abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate (mm/year) between participants who received statins and those who did not receive statins. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect.

Figure 10.

Forrest plot summarising the statins on abdominal aortic aneurysm-related clinical events (AAA rupture, repair or related death). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the AAA-related events. Boxes represent a point estimate of the effect and study size. Lines represent 95%CI of the effect.

Discussion

Metformin

Metformin is recommended as a first-line treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in global practice guidelines, 42 which can suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis, increase insulin sensibility in the gut lumen, and activate the AMP (Adenosine 5′-monophosphate) -activated protein kinase for patients with T2DM. 43 Metformin has been proved to be involved in the critical pathologic mechanisms implicated in AAA. Metformin can reduce the monocyte infiltration and limit plaque formation in mice model. 44 The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was activated in aneurysmal wall tissues of AAA patients and rat model, metformin can repress the pathway to inhibit the loss of collagen, the apoptosis of aortic cells, and the breakage of elastin structure of the aorta. 45 In the AAA mice models, metformin dramatically suppressed the formation and progression of AAA by preserving medial elastin and smooth muscle and reducing aortic mural macrophage, CD8 T cell. 3 For the patients with AAA and metformin prescription, metformin can reduce expression of a large number of proinflammatory cytokines in plasma. 17

Through the meta-analysis of the clinical trials included in this study, metformin had been proved to limit AAA growth and AAA-related events. While all of the included studies were cohort studies or case-control studies, RCTs to demonstrate the effect of metformin on AAA are still lacking. Three RCTs about metformin are still ongoing, Metformin for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth Inhibition (MAAAGI) trial (NCT0422405) is a multicentre, prospective, randomized clinical trial developed by Uppsala University, Sweden, which has plans to include 500 participants in a parallel assignment to compare AAA growth rates between patients who received metformin 2 g daily and those who receive standard care. 46 Two other RCTs have been registered and may achieve complementary results, Metformin therapy in non-diabetic AAA patients (MetAAA) (NCT03507413) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2 /show/ NCT03507413?term = metformin&cond = aneurysm&draw = 2&rank = 2),Limiting AAA with metformin (LIMIT) trial(NCT04224051) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT04500756? Term = metformin&cond = aneurysm&draw = 2&rank = 3), these RCTs will provide strong evidence of whether or not metformin is efficient and safe in preventing AAA growth in the future.

Hypotensive drugs

The following four studies have shown that blood pressure-lowering drugs can inhibit the development of AAA in animal models: the ACEI and ARB could prevent the AAA progression in the mouse AAA model by infusion of angiotensin II; 47 the renin angiotensin system (RAS) plays an important role in AAA formation and growth; 48 the ARB and ACEI can block or deficient angiotensin receptor (ATR) to limit the AAA growth, perindopril (ACEI drugs) has also been shown to inhibit aortic degeneration and AAA formation in rat AAA animal models induced by elastase and calcium chloride; 49 the propranolol could delay the formation of aneurysms in the male blotchy mouse, which was related to the fact that propranolol enhanced the activity of aortic lysyl oxidase and promoted the formation and maturation of lysyl-derived crosslinks in aortic elastin. 50

The hypotensive drugs of the include studies mainly included ACEI, ARB, and propranolol, while overall meta-analysis of blood pressure-lowering drugs reported no significant effect in limiting the AAA growth, the ACEI/ARB and propranolol also showed no significance in reducing the AAA growth and AAA-related events in the subgroup analysis, the previous research had similar conclusion. 7 The main reason for the negative result was that AAA formation was a chronic process in clinical patients, and the mechanism was relatively complex, while AAA animal models were in acute formation induced by angiotensin II, elastase, or calcium chloride, these drugs may not be able to reverse a chronic structural defect in a major artery repeatedly exposed to cycles of systolic pressure. 51

Antibiotics

In murine models, the doxycycline could inhibit the Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs, mediate elastin and collagen degradation in the aortic wall) and AAA growth. 52 Chlamydia pneumoniae has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic lesions in AAA, 53 immunoglobulin A antibodies against C pneumoniae, at a level of 20 enzyme immune units, have been demonstrated to be associated with an increased expansion of small AAA, 54 macrolides had shown positive side effects on antichlamydial, while the studies about azithromycin 31 and roxithromycin 32 on AAA growth showed different conclusions. In this study, the meta-analysis reported no compelling evidence to support the use of antibiotics in limiting AAA progression, and all of the included studies were RCTs. The result further illustrated that doxycycline could not be recommended for pharmacologic treatment of small AAAs. The unexpected findings fundamentally challenge the validity of the existing models of human AAA.

Statins

Statins are 3-hydrox-3-ymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, widely prescribed for their lipid-lowering effects. They are expected to prevent AAA development through anti-oxidative effects, anti-inflammatory effects, inhibition of proteases, and upregulation of synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins. 55 Statins inhibit various inflammatory mediators and other key molecules, including MMPs produced by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and macrophages. 56 In this study, the meta-analysis of statins showed no significant effect in limiting the AAA growth in this study, which showed different results with another systemic review. 11 It should be noted that all the studies of statins are cohort studies or case-control studies, so RCTs are needed for further verification.

Other pharmacotherapy on AAA

In addition to the drugs included in the systemic review, the following studies have confirmed that other drugs have a certain effect on AAA. The trial investigating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in treating AAA is still undergoing. 12 MSCs can stimulate T regulatory (Treg) lymphocytes, which in turn inhibit CD4 + and CD8 + T-cell proliferation and function. Previous studies have demonstrated decreased quantity and functionality of Tregs in AAA conditions. 57 Furthermore, treatment with Treg infusion seemed to inhibit AAA expansion in a murine model. 58 Fibrates, such as fenofibrate or bezafibrate, are used to treat hypertriglyceridaemia. 59 Past experimental research suggests that fenofibrate could reduce macrophage infiltration to the aorta and limit excessive aortic remodeling, thereby inhibiting AAA progression; 13 Ticagrelor is a potent anti-platelet drug that acts by selectively and reversibly binding to the platelet P2Y12 receptor, blocking the actions of the platelet agonist adenosine diphosphate (ADP). 60 Platelet activation and intraluminal thrombus (ILT) renewal are key events in AAA progression, ticagrelor has been proved to inhibit platelet activation and significantly attenuated aneurysm formation in rat models, 61 while ticagrelor did not reduce the growth of small AAAs in a recent RCT. 14

Limitations

There are three limitations in this study that should be acknowledged. First, the high percentage of studies(16/26) included are not RCTs, and more RCTs are needed for further verification. Second, substantial heterogeneity among the included studies should be noted. Third, it is limited to estimating the AAA growth rate only by its maximum diameter. For a more comprehensive assessment of AAA growth, other relevant indicators need to be included: AAA volume, wall stress, and fluid dynamics. Future research should take these points into careful consideration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, effective pharmacotherapy for AAA was still lacking. Although the meta-analysis showed that metformin use was associated with lower AAA growth and AAA-related events, all of the included studies about metformin were cohort studies or case control studies. More randomized controlled trials(RCTs) are needed for further verification.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, (grant number No.2021YFC2500500).

ORCID iD: Yongquan Gu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2869-9736

References

- 1.Golledge J, Muller J, Daugherty A, Norman P. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: pathogenesis and implications for management. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, And Vascular Biology. 2006;26(12):2605‐2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakalihasan N, Michel J, Katsargyris A, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2018;4(1):34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujimura N, Xiong J, Kettler E, et al. Metformin treatment status and abdominal aortic aneurysm disease progression. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2016;64(1):46‐54.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens R, Grytsan A, Biasetti J, Roy J, Lindquist Liljeqvist M, Gasser T. Biomechanical changes during abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. PloS One. 2017;12(11):e0187421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba T, Ohki T, Kanaoka Y, et al. Risk factor analyses of abdominal aortic aneurysms growth in Japanese patients. Annals Of Vascular Surgery. 2019;55:196‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweeting M, Thompson S, Brown L, Powell J. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The British Journal Of Surgery. 2012;99(5):655‐665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golledge J, Singh T. Effect of blood pressure lowering drugs and antibiotics on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2021;107(18):1465‐1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golledge J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2019;16(4):225‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel T, Shishehbor M, Bhatt D. A review of high-dose statin therapy: targeting cholesterol and inflammation in atherosclerosis. European Heart Journal. 2007;28(6):664‐672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans J, Powell J, Schwalbe E, Loftus I, Thompson M. Simvastatin attenuates the activity of matrix metalloprotease-9 in aneurysmal aortic tissue. European Journal Of Vascular And Endovascular Surgery : The Official Journal Of The European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2007;34(3):302‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salata K, Syed M, Hussain M, et al. Statins reduce abdominal aortic aneurysm growth, rupture, and perioperative mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7(19):e008657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Green L, Gutwein A, et al. Rationale and design of the ARREST trial investigating mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Annals Of Vascular Surgery. 2018;47:230‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moxon J, Rowbotham S, Pinchbeck J, et al. A randomised controlled trial assessing the effects of peri-operative fenofibrate administration on abdominal aortic aneurysm pathology: outcomes from the FAME trial. European Journal Of Vascular And Endovascular Surgery : The Official Journal Of The European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2020;60(3):452‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wanhainen A, Mani K, Kullberg J, et al. The effect of ticagrelor on growth of small abdominal aortic aneurysms-a randomized controlled trial. Cardiovascular Research. 2020;116(2):450‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J, Altman D, Gøtzsche P, et al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unosson J, Wågsäter D, Bjarnegård N, et al. Metformin prescription associated with reduced abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate and reduced chemokine expression in a Swedish cohort. Annals Of Vascular Surgery. 2021;70:425‐433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoga N, Rothenberg K, Suarez P, et al. Metformin prescription status and abdominal aortic aneurysm disease progression in the U.S. Veteran population. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2019;69(3):710‐716.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golledge J, Morris D, Pinchbeck J, et al. Editor’s choice - metformin prescription is associated with a reduction in the combined incidence of surgical repair and rupture related mortality in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery : the Official Journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2019;57(1):94‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristensen K, Pottegård A, Hallas J, Rasmussen L, Lindholt J. Metformin treatment does not affect the risk of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2017;66(3):768‐774.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golledge J, Moxon J, Pinchbeck J, et al. Association between metformin prescription and growth rates of abdominal aortic aneurysms. The British Journal Of Surgery. 2017;104(11):1486‐1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golledge J, Pinchbeck J, Tomee S, et al. Efficacy of telmisartan to slow growth of small abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiology. 2020;5(12):1374‐1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiru G, Bicknell C, Falaschetti E, Powell J, Poulter N. An evaluation of the effect of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on the growth rate of small abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomised placebo-controlled trial (AARDVARK). Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2016;20(59):1‐180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristensen K, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason G, Egfjord M, Rasmussen H, Hansen P. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms: nation-wide cohort study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, And Vascular Biology. 2015;35(3):733‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sweeting M, Thompson S, Brown L, Greenhalgh R, Powell J. Use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors is associated with increased growth rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2010;52(1):1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackam D, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and aortic rupture: a population-based case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2006;368(9536):659‐665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Propanolol Aneurysm Trial Investigators. Propranolol for small abdominal aortic aneurysms: results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(1):72‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindholt J, Henneberg E, Juul S, Fasting H. Impaired results of a randomised double blinded clinical trial of propranolol versus placebo on the expansion rate of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. International Angiology : A Journal Of The International Union of Angiology. 1999;18(1):52‐57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baxter B, Matsumura J, Curci J, et al. Effect of doxycycline on aneurysm growth among patients with small infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2020;323(20):2029‐2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijer C, Stijnen T, Wasser M, Hamming J, van Bockel J, Lindeman J. Doxycycline for stabilization of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized trial. Annals Of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(12):815‐823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsson L, Gnarpe J, Bergqvist D, Lindbäck J, Pärsson H. The effect of azithromycin and chlamydophilia pneumonia infection on expansion of small abdominal aortic aneurysms--a prospective randomized double-blind trial. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2009;50(1):23‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Høgh A, Vammen S, Ostergaard L, Joensen J, Henneberg E, Lindholt J. Intermittent roxithromycin for preventing progression of small abdominal aortic aneurysms: long-term results of a small clinical trial. Vascular And Endovascular Surgery. 2009;43(5):452‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vammen S, Lindholt J, Ostergaard L, Fasting H, Henneberg E. Randomized double-blind controlled trial of roxithromycin for prevention of abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion. The British Journal Of Surgery. 2001;88(8):1066‐1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosorin M, Juvonen J, Biancari F, et al. Use of doxycycline to decrease the growth rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2001;34(4):606‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gokani V, Sidloff D, Bath M, Bown M, Sayers R, Choke E. A retrospective study: factors associated with the risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. Vascular Pharmacology. 2015;65-66:13‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wemmelund H, Høgh A, Hundborg H, Thomsen R, Johnsen S, Lindholt J. Statin use and rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm. The British Journal Of Surgery. 2014;101(8):966‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Meij E, Koning G, Vriens P, et al. A clinical evaluation of statin pleiotropy: statins selectively and dose-dependently reduce vascular inflammation. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e53882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson C, Clancy P, Bourke B, et al. Association of statin prescription with small abdominal aortic aneurysm progression. American Heart Journal. 2010;159(2):307‐313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karrowni W, Dughman S, Hajj G, Miller F. Statin therapy reduces growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of Investigative Medicine : The Official Publication Of The American Federation for Clinical Research. 2011;59(8):1239‐1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosorin M, Niemelä E, Heikkinen J, et al. The use of statins and fate of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Interactive Cardiovascular And Thoracic Surgery. 2008;7(4):578‐581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schouten O, van Laanen J, Boersma E, et al. Statins are associated with a reduced infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. European Journal Of Vascular And Endovascular Surgery : The Official Journal Of The European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2006;32(1):21‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inzucchi S, Bergenstal R, Buse J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American diabetes association and the European association for the study of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schernthaner G, Schernthaner G. The right place for metformin today. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;159:107946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vasamsetti S, Karnewar S, Kanugula A, Thatipalli A, Kumar J, Kotamraju S. Metformin inhibits monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation via AMPK-mediated inhibition of STAT3 activation: potential role in atherosclerosis. Diabetes. 2015;64(6):2028‐2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Z, Guo J, Han X, et al. Metformin represses the pathophysiology of AAA by suppressing the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR/autophagy pathway in ApoE mice. Cell & Bioscience. 2019;9:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wanhainen A, Unosson J, Mani K, Gottsäter A. The metformin for abdominal aortic aneurysm growth inhibition (MAAAGI) trial. European Journal Of Vascular And Endovascular Surgery : The Official Journal Of The European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2021;61(4):710‐711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue N, Muramatsu M, Jin D, et al. Involvement of vascular angiotensin II-forming enzymes in the progression of aortic abdominal aneurysms in angiotensin II- infused ApoE-deficient mice. Journal Of Atherosclerosis And Thrombosis. 2009;16(3):164‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao S, Miralles M, Kelley B, Curci J, Borhani M, Thompson R. Suppression of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms in the rat by treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2001;33(5):1057‐1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiong F, Zhao J, Zeng G, Huang B, Yuan D, Yang Y. Inhibition of AAA in a rat model by treatment with ACEI perindopril. The Journal Of Surgical Research. 2014;189(1):166‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brophy C, Tilson J, Tilson M. Propranolol delays the formation of aneurysms in the male blotchy mouse. The Journal of Surgical Research. 1988;44(6):687‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Golledge J, Moxon J, Singh T, Bown M, Mani K, Wanhainen A. Lack of an effective drug therapy for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal Of Internal Medicine. 2020;288(1):6‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prall A, Longo G, Mayhan W, et al. Doxycycline in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms and in mice: comparison of serum levels and effect on aneurysm growth in mice. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2002;35(5):923‐929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindholt J, Ashton H, Scott R. Indicators of infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae are associated with expansion of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2001;34(2):212‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindholt J, Juul S, Vammen S, Lind I, Fasting H, Henneberg E. Immunoglobulin A antibodies against Chlamydia pneumoniae are associated with expansion of abdominal aortic aneurysm. The British Journal Of Surgery. 1999;86(5):634‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyake T, Morishita R. Pharmacological treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovascular Research. 2009;83(3):436‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Sugiyama S, et al. An HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation. 2001;103(2):276‐283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin M, Zhang J, Wang Y, et al. Deficient CD4 + CD25 + T regulatory cell function in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, And Vascular Biology. 2010;30(9):1825‐1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ait-Oufella H, Wang Y, Herbin O, et al. Natural regulatory T cells limit angiotensin II-induced aneurysm formation and rupture in mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, And Vascular Biology. 2013;33(10):2374‐2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wierzbicki A. Fibrates in the treatment of cardiovascular risk and atherogenic dyslipidaemia. Current Opinion In Cardiology. 2009;24(4):372‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurbel P, Bliden K, Butler K, et al. Randomized double-blind assessment of the ONSET and OFFSET of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the ONSET/OFFSET study. Circulation. 2009;120(25):2577‐2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dai J, Louedec L, Philippe M, Michel J, Houard X. Effect of blocking platelet activation with AZD6140 on development of abdominal aortic aneurysm in a rat aneurysmal model. Journal Of Vascular Surgery. 2009;49(3):719‐727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]