Abstract

Background

Childbearing-aged female patients and elderly patients with bipolar disorder need special attention for pharmacological treatments, but current guidelines provide little information on their pharmacological treatment. In particular, the risk/benefit balance of pharmacological treatment for childbearing-aged females with bipolar disorder is a growing concern. Therefore, we aimed to address the effect of age and sex on psychotropic drug prescription for outpatients with bipolar disorder.

Methods

The MUlticenter treatment SUrvey for BIpolar disorder in Japanese psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI) study was conducted, and data on age, sex, and details of pharmacological treatment were collected.

Results

A total of 3106 outpatients were included in this study. Among young females (age ≤ 39), 25% were prescribed valproate. There was no significant difference in the frequency and daily dose of valproate prescription for young females among all groups. Valproate prescriptions were significantly less frequent among young males and more frequent among middle-aged males. Lithium prescriptions were significantly less frequent among young females and more frequent among older males (age ≥ 65) and older females. Lamotrigine prescriptions were significantly more frequent among young males and young females and less frequent among older males and older females. Carbamazepine prescriptions were significantly less frequent among young males and more frequent among older males.

Conclusions

Biased information about the risk and safety of valproate and lithium for young females was suggested, and further study to correct this bias is needed. Older patients were prescribed lithium more commonly than lamotrigine. Further studies are needed to determine the actual pharmacotherapy for elderly individuals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12991-022-00415-0.

Keywords: Valproate, Mood stabilizer, Childbearing age, Elderly, Real world, Outpatients

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a recurrent chronic disorder characterized by fluctuations in mood state and energy [1]. The prevalence rate of bipolar disorder among the world’s population is approximately 1–2% [2, 3]. Pharmacological treatments are standard care to prevent and treat fluctuations in mood state. There have been several clinical practice guidelines, such as the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT 2018), Korean Medical Algorithm Project for Bipolar Disorder 2018 (KMAP-BP 2018) and the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017) [4–6].

Because some mood stabilizers have teratogenic risk, childbearing-aged females need special attention for pharmacological treatment. Lithium is known as a risk factor for Ebstein’s anomaly [7]. However, one meta-analysis reported no significantly increased risk of congenital malformations [8]. Valproate increases the risks of autism and lowers intelligence quotient (IQ) scores [9, 10]. A lower IQ score was dose-dependently more severe among children with in utero exposure to valproate by their mothers with epilepsy [9]. Carbamazepine increases the risks of spina bifida [11]. Elderly patients also need special attention for pharmacological treatment because of their lower tolerability. To prevent lithium toxicity due to a decrease in renal function, careful monitoring of serum lithium concentrations is needed [12]. Because of these issues, pharmacological treatments tend to be adjusted by age and sex.

Recent Japanese expert consensus guidelines reported that there were no first-line treatments for depressive and manic episodes in elderly individuals [13]. CANMAT 2018 reported that monotherapy with lithium or valproate was recommended as a first-line treatment for elderly individuals with acute mania. Regarding elderly individuals with depression, monotherapy with quetiapine or lurasidone was recommended as a first-line option [6]. Regarding mania in elderly individuals, KMAP-BP 2018 reported that monotherapy with atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilizers was the first-line treatment. In addition, first-line mood stabilizers included valproate and lithium, and first-line atypical antipsychotics included aripiprazole, quetiapine and olanzapine. For depression in elderly individuals, they reported that monotherapy of atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilizers, mood stabilizers plus atypical antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics plus lamotrigine, and mood stabilizers plus lamotrigine were first-line treatments. In addition, first-line mood stabilizers included lamotrigine, valproate and lithium, and first-line atypical antipsychotics included aripiprazole, quetiapine and olanzapine [5]. For pregnant females, CANMAT 2018 reported no specific recommendation, but that valproate should be avoided [6]. KMAP-BP 2018 reported no first-line recommendation for females of childbearing age [5]. CINP-BD-2017 reported that monotherapy of atypical antipsychotics and lamotrigine (in doses < 200 mg/day) are reasonable choices for pregnant females who need pharmacological treatments. In addition, they reported that valproate and carbamazepine should be avoided in any pregnant cases [4].

Approximately 90% of patients with bipolar disorder in Japan receive outpatient treatment, and half of them are treated at clinics that are members of Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics [14]. Current guidelines provide little information on pharmacological treatment for special populations, such as childbearing-aged female and elderly patients, because they lack information on the first-line treatment or optimal dose. Therefore, we aimed to address the effect of age and sex on psychotropic drug prescription for outpatients with bipolar disorder.

Methods

Participants and methods

This study (the MUlticenter treatment SUrvey on Bipolar disorder in Japanese psychiatric clinics, MUSUBI) was a cross-sectional study conducted at 176 outpatient clinics belonging to the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics [15–24]. MUSUBI was conducted between September 2016 and October 2016, and a questionnaire was administered. Patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder according to the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision were included in this study. Clinical psychiatrists were asked to complete a questionnaire about patients, and the medical records of the patients were reviewed to obtain medication and demographic data (age and sex). We mailed 20 copies of the questionnaire to each outpatient clinic. A chlorpromazine equivalent for antipsychotics, imipramine equivalent for antidepressants and diazepam equivalent for benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs) were used for the purpose of comparison [25].

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) and number (%). Those younger than 39 years were grouped into the “young” group, those 40–64 years old were grouped into the “middle-aged” group, and those older than 65 years were grouped into the “older” group. Chi-square tests were performed for categorical variables, and residual analysis was performed to compare more than three groups. Two-tailed t tests were performed for continuous variables. Dose differences in mood stabilizers among age groups or among age and sex groups were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni correction. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS statistics software for Windows version 27.0.0.0 (Japan IBM, Tokyo, Japan) and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego California, USA).

Results

Completed questionnaires of 3213 outpatients from 176 originally solicited outpatient clinics were returned. A total of 107 outpatients with missing data were excluded, which included the data lacking age (n = 28), sex (n = 3) and all blank paper (n = 76); thus, a total of 3106 outpatients were included in this study. The frequency of prescriptions for mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs divided by age and sex is shown in Table 1. The proportion of patients who were prescribed lithium was 51.0% among males and 44.5% among females. The Chi-square test showed significant differences (p < 0.001). The proportion of patients who were prescribed BZRAs was significantly different between sexes (p = 0.015). Among the three age groups, the proportions of patients who were prescribed lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs were significantly different (p < 0.001, p = 0.004, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.002, p < 0.001, respectively). Residual analysis revealed significant differences in the young group and older group among those prescribed lithium (Additional file 1: Table S1). Regarding valproate, the young group and middle-aged group were significantly different. Regarding lamotrigine, the young group and older group were significantly different. Regarding antipsychotics, the middle-aged group and older group were significantly different. Regarding antidepressants, the middle-aged group and older group were significantly different. Regarding BZRAs, the young group and middle-aged group were significantly different.

Table 1.

Numbers (%) of drugs for mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs divided by age and sex

| Sex | Age (years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Significance | ≤ 39 | 40–64 | ≥ 65 | Significance | |

| N = 1408 | N = 1698 | N = 676 | N = 1899 | N = 531 | |||

| Mood stabilizers | |||||||

| Lithium | 718 (51.0%) | 755 (44.5%) | < 0.001 | 287 (42.5%) | 902 (47.5%) | 284 (53.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Valproate | 408 (29.0%) | 474 (27.9%) | 0.513 | 160 (23.7%) | 575 (30.3%) | 147 (27.7%) | 0.004 |

| Lamotrigine | 337 (23.9%) | 397 (23.4%) | 0.717 | 200 (29.6%) | 465 (24.5%) | 69 (13.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Carbamazepine | 72 (5.1%) | 77 (4.5%) | 0.452 | 21 (3.1%) | 103 (5.4%) | 25 (4.7%) | 0.053 |

| Other medications | |||||||

| Antipsychotics | 777 (55.1%) | 911 (53.6%) | 0.393 | 387 (57.2%) | 1075 (56.6%) | 226 (42.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Antidepressants | 566 (40.1%) | 713 (41.9%) | 0.312 | 271 (40.0%) | 822 (43.2%) | 186 (35.0%) | 0.002 |

| BZRAs | 969 (68.8%) | 1236 (72.7%) | 0.015 | 443 (65.5%) | 1391 (73.2%) | 371 (69.8%) | < 0.001 |

BZRAs, benzodiazepine receptor agonists

The daily doses of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs divided by age and sex are shown in Table 2. The daily dose of lithium was significantly higher among males than females (p < 0.001). Among the three aged groups, the doses of lithium, valproate, antipsychotics, and antidepressants were significantly different by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.018, p = 0.024, respectively). Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis showed that the daily dose of lithium in the older group was significantly lower than that in the young group and middle-aged group (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). Regarding valproate, the daily dose in the middle-aged group was significantly higher than that in the older group (p < 0.001). Regarding antipsychotics, the daily dose in the middle-aged group was significantly higher than that in the older group (p = 0.047). Regarding antidepressants, the daily dose in the middle-aged group was significantly higher than that in the older group (p = 0.027).

Table 2.

Dose of drugs for mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs divided by age and sex

| Sex | Age (years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Significance | ≤ 39 | 40–64 | ≥ 65 | Significance | |

| N = 1408 | N = 1698 | N = 676 | N = 1899 | N = 531 | |||

| Mood stabilizers | |||||||

| Lithium | 599.9 (248.1) | 519.2 (235.4) | < 0.001 | 601.7 (275.7) | 579.7 (241.0) | 447.5 (186.0) | < 0.001 |

| Valproate | 535.8 (272.0) | 504.2 (268.9) | 0.083 | 490.6 (281.6) | 543.7 (273.4) | 451.9 (231.6) | < 0.001 |

| Lamotrigine | 160.2 (98.6) | 158.2 (103.0) | 0.780 | 159.9 (98.4) | 161.1 (103.6) | 143.0 (88.5) | 0.376 |

| Carbamazepine | 354.9 (208.8) | 372.1 (197.4) | 0.606 | 352.3 (199.0) | 384.4 (211.7) | 288.0 (145.9) | 0.098 |

| Other medications | |||||||

| Antipsychotics | 206.0 (227.4) | 218.8 (264.1) | 0.302 | 196.2 (209.5) | 225.9 (268.5) | 180.3 (201.4) | 0.018 |

| Antidepressants | 125.2 (101.1) | 127.1 (106.3) | 0.746 | 121.9 (97.6) | 131.5 (104.7) | 109.4 (108.1) | 0.024 |

| BZRAs | 14.4 (19.5) | 15.1 (28.1) | 0.484 | 14.3 (27.4) | 15.6 (25.0) | 12.4 (19.9) | 0.078 |

BZRAs, benzodiazepine receptor agonists

Table 3 shows the five most often prescribed drugs for antipsychotics, antidepressants and BZRAs divided by age and sex. Regarding antipsychotics, aripiprazole was the most often prescribed antipsychotic among young males (25.7%), young females (26.4%), middle-aged males (20.2%) and middle-aged females (20.6%). Olanzapine was the most often prescribed antipsychotic among older males (12.4%), and quetiapine was the most often prescribed antipsychotic among older females (11.4%). Regarding antidepressants, duloxetine was the most often prescribed antidepressant among middle-aged males (8.6%), middle-aged females (7.9%) and older females (7.1%). Escitalopram was the most often prescribed antidepressant among young males (9.5%) and young females (8.7%), and mirtazapine was the most often prescribed antidepressant among older males (7.6%). Flunitrazepam was the most often prescribed BZRA among young males (12.6%), young females (13.6%), middle-aged males (21.7%), middle-aged females (22.2%), older males (21.5%) and older females (21.1%).

Table 3.

Numbers (%) and dose of the five most often prescribed drugs divided by age and sex

| n (%) | Mean dose (SD) | n (%) | Mean dose (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| Young males | Young females | ||||

| Aripiprazole | 65 (25.7) | 5.4 (5.6) | Aripiprazole | 112 (26.4) | 7.5 (7.0) |

| Olanzapine | 42 (16.6) | 5.3 (4.4) | Quetiapine | 52 (12.2) | 129.6 (163.0) |

| Quetiapine | 29 (11.5) | 80.5 (74.7) | Olanzapine | 50 (11.7) | 5.1 (4.6) |

| Sulpiride | 15 (5.9) | 100.0 (53.4) | Risperidone | 20 (4.7) | 1.4 (1.0) |

| Levomepromazine | 9 (3.5) | 12.3 (15.1) | Levomepromazine | 19 (4.4) | 32.3 (37.4) |

| Middle-aged males | Middle-aged females | ||||

| Aripiprazole | 192 (20.2) | 7.2 (6.9) | Aripiprazole | 197 (20.6) | 8.1 (7.7) |

| Olanzapine | 126 (13.3) | 6.2 (5.1) | Olanzapine | 137 (14.3) | 6.7 (5.4) |

| Quetiapine | 104 (10.9) | 149.0 (157.5) | Quetiapine | 126 (13.2) | 137.3 (174.3) |

| Sulpiride | 73 (7.7) | 122.9 (69.8) | Levomepromazine | 57 (5.9) | 30.5 (55.6) |

| Levomepromazine | 50 (5.2) | 26.1 (29.8) | Risperidone | 41 (4.3) | 1.8 (1.3) |

| Older males | Older females | ||||

| Olanzapine | 26 (12.4) | 5.8 (3.5) | Quetiapine | 37 (11.4) | 88.3 (113.1) |

| Quetiapine | 20 (9.5) | 110.0 (158.7) | Olanzapine | 35 (10.8) | 7.1 (5.7) |

| Levomepromazine | 13 (6.2) | 26.1 (25.0) | Aripiprazole | 24 (7.4) | 6.8 (5.9) |

| Sulpiride | 11 (5.2) | 103.8 (65.1) | Levomepromazine | 15 (4.6) | 13.2 (8.8) |

| Aripiprazole | 8 (3.8) | 13.8 (10.8) | Sulpiride | 12 (3.7) | 97.9 (45.7) |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Young males | Young females | ||||

| Escitalopram | 24 (9.5) | 13.3 (7.6) | Escitalopram | 37 (8.7) | 12.4 (5.3) |

| Duloxetine | 23 (9.1) | 36.0 (16.1) | Duloxetine | 37 (8.7) | 37.8 (17.8) |

| Mirtazapine | 14 (5.5) | 23.0 (11.9) | Sertraline | 29 (6.8) | 57.3 (30.5) |

| Paroxetine | 11 (4.3) | 21.1 (11.3) | Trazodone | 27 (6.3) | 46.2 (38.5) |

| Sertraline | 6 (2.3) | 62.5 (30.6) | Paroxetine | 22 (5.1) | 24.3 (15.4) |

| Middle-aged males | Middle-aged females | ||||

| Duloxetine | 82 (8.6) | 38.7 (16.4) | Duloxetine | 76 (7.9) | 42.6 (16.1) |

| Mirtazapine | 80 (8.4) | 22.5 (12.9) | Escitalopram | 63 (6.6) | 12.9 (5.6) |

| Trazodone | 57 (6.0) | 49.0 (33.2) | Mirtazapine | 63 (6.6) | 26.7 (12.2) |

| Paroxetine | 51 (5.3) | 22.1 (13.2) | Trazodone | 58 (6.0) | 46.9 (26.1) |

| Escitalopram | 46 (4.8) | 12.6 (5.2) | Paroxetine | 46 (4.8) | 22.9 (13.7) |

| Older males | Older females | ||||

| Mirtazapine | 16 (7.6) | 23.9 (9.1) | Duloxetine | 23 (7.1) | 41.7 (14.9) |

| Trazodone | 9 (4.3) | 55.5 (24.2) | Mirtazapine | 22 (6.8) | 19.4 (14.5) |

| Duloxetine | 8 (3.8) | 43.7 (15.0) | Fluvoxamine | 16 (4.9) | 68.7 (40.5) |

| Amoxapine | 7 (3.3) | 51.4 (30.3) | Trazodone | 14 (4.3) | 35.7 (12.8) |

| Fluvoxamine | 7 (3.3) | 75.0 (38.1) | Paroxetine | 13 (4.0) | 12.3 (12.1) |

| BZRAs | |||||

| Young males | Young females | ||||

| Flunitrazepam | 32 (12.6) | 1.8 (0.8) | Flunitrazepam | 58 (13.6) | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Zolpidem | 27 (10.7) | 8.7 (2.2) | Brotizolam | 50 (11.7) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Brotizolam | 26 (10.3) | 0.2 (0.1) | Etizolam | 40 (9.4) | 1.4 (1.6) |

| Triazolam | 24 (9.5) | 0.3 (0.1) | Alprazolam | 38 (8.9) | 0.9 (0.4) |

| Etizolam | 19 (7.5) | 1.2 (0.8) | Zolpidem | 37 (8.7) | 9.1 (2.0) |

| Middle-aged males | Middle-aged females | ||||

| Flunitrazepam | 206 (21.7) | 1.9 (1.7) | Flunitrazepam | 212 (22.2) | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Brotizolam | 131 (13.8) | 0.2 (0.1) | Brotizolam | 150 (15.7) | 0.4 (2.0) |

| Triazolam | 90 (9.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | Zolpidem | 90 (9.4) | 9.5 (9.9) |

| Etizolam | 86 (9.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | Triazolam | 88 (9.2) | 0.3 (0.1) |

| Zolpidem | 75 (7.9) | 9.0 (2.0) | Etizolam | 86 (9.0) | 1.4 (1.7) |

| Older males | Older females | ||||

| Flunitrazepam | 45 (21.5) | 1.5 (0.6) | Flunitrazepam | 68 (21.1) | 1.8 (0.7) |

| Brotizolam | 28 (13.3) | 0.6 (1.8) | Brotizolam | 51 (15.8) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| Triazolam | 18 (8.6) | 0.2 (0.1) | Etizolam | 29 (9.0) | 0.9 (0.6) |

| Etizolam | 17 (8.1) | 1.2 (0.7) | Zolpidem | 23 (7.1) | 7.2 (2.7) |

| Zolpidem | 15 (7.1) | 9.0 (3.8) | Alprazolam | 18 (5.5) | 0.8 (0.5) |

BZRAs, benzodiazepine receptor agonists

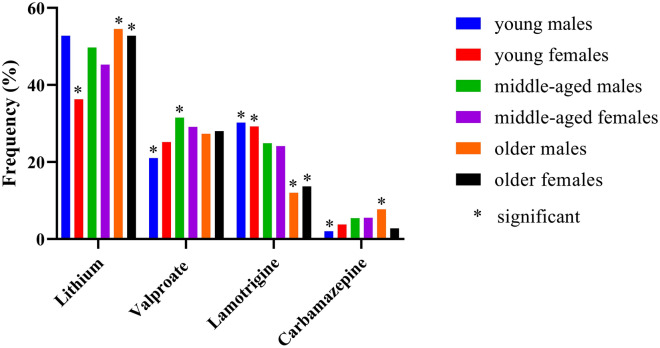

The comparison of frequencies of mood stabilizer prescriptions in each age–sex group is shown in Fig. 1. Significant differences in the frequencies of lithium, valproate, lamotrigine and carbamazepine were shown by the Chi-square test (p < 0.001, p = 0.018, p < 0.001, p = 0.019, respectively). Residual analysis showed significant differences in the frequency of lithium prescriptions among young females, older males and older females (Additional file 2: Table S2). The frequencies of valproate prescriptions among young males and middle-aged males were significantly different. The frequencies of lamotrigine prescriptions among young males, young females, older males and older females were significantly different. The frequencies of carbamazepine prescriptions among young males and older males were significantly different.

Fig. 1.

Prescriptions of mood stabilizers by age and sex. *p < 0.05

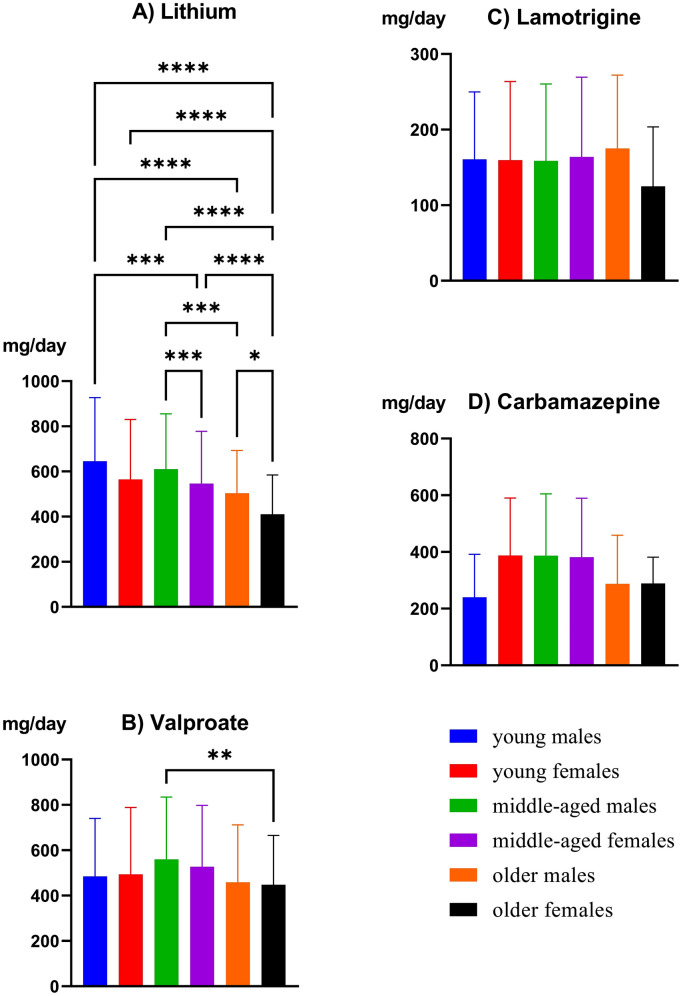

The comparison of daily doses for mood stabilizer prescriptions in each age–sex group is shown in Fig. 2. Significant differences were shown by one-way ANOVA regarding lithium and valproate (p < 0.001, p = 0.003, respectively). Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis showed that the daily dose of lithium among young males was significantly higher than that among middle-aged females, older males and older females (p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, respectively). The daily dose of lithium among young females was significantly higher than that among older females (p < 0.0001). The daily dose of lithium among middle-aged males was significantly higher than that among middle-aged females, older males and older females (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, respectively). The daily dose of lithium among middle-aged females was significantly higher than that among older females (p < 0.001). The daily dose of lithium among older males was significantly higher than that among older females (p = 0.016). Regarding valproate, the daily dose among middle-aged males was significantly higher than that among older males (p = 0.008).

Fig. 2.

Daily dose of mood stabilizers by age and sex. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Discussion

This study had two main findings. First, among young females in our survey, 25% were prescribed valproate. In addition, there was no significant difference in the frequency and daily dose of valproate prescription for young females among all groups. In contrast, lithium prescription for young females was significantly rare. Second, among older males and older females, lithium prescription was significantly frequent, and lamotrigine prescription was significantly rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report psychotropic drug prescriptions, including information about the frequency and daily dose, for childbearing-aged female and elderly outpatients with bipolar disorder in Japan.

Lithium was significantly less commonly prescribed to young women in this study. This is partly because psychiatrists are concerned about the risk of Ebstein's malformation [7] with lithium and because lithium is contraindicated in pregnant and parturient women in Japan. Regarding lithium, an overestimated risk of congenital malformation has been reported [26]. The risk/benefit balance of lithium for pregnant females has been debated [8]. For females of childbearing age, on the other hand, the risk of neurodevelopmental disabilities caused by valproate has become a growing concern. In addition, a worldwide survey reported that 41% of pregnancies were unintended [27]. Therefore, some guidelines have suggested against prescribing valproate for females of childbearing age [4, 6]. Valproate is contraindicated in Japan in principle for pregnant and parturient women. Nevertheless, there was no significant discrepancy in the frequency of valproate prescriptions between young women and other groups in this study. This result may be supported by a previous study [28] that surveyed Japanese psychiatrists' attitudes toward prescribing valproic acid to women of childbearing age, which lacked data on actual valproic acid prescription but reported that Japanese psychiatrists often prescribe valproic acid to women of childbearing age. The previous study [28] also reported that psychiatrists working at general hospitals tended to refrain from prescribing valproate to childbearing-aged female compared to those affiliated with other medical facilities, such as psychiatric hospitals and private clinics. Little chances and experience of psychiatrists working at clinics in consulting for pregnant female with psychiatric diseases might increase their valproate prescription to women of childbearing age. This finding supports the reported awareness of the high incidence of valproic acid prescription by Japanese psychiatrists to women of childbearing age. For younger women, lamotrigine is the preferred choice because of its relative safety during pregnancy [4].

Among elderly individuals, lithium and carbamazepine were commonly prescribed for older men, while lamotrigine was rarely prescribed. This may be due to the repeated long-term prescription of lithium and carbamazepine, which are older drugs than lamotrigine. This may be a reasonable result, since drugs that are effective in adults are also effective in older bipolar patients [29, 30]. Because lithium prescriptions are declining worldwide [31–34], older patients who are repeatedly prescribed lithium on a long-term basis are more likely than younger or middle-aged patients to be prescribed lithium more frequently. Similarly, given the downward trend in carbamazepine prescriptions [33], older men who are repeatedly prescribed carbamazepine on a long-term basis may have a statistically increased frequency of carbamazepine prescription compared to younger men. Furthermore, valproic acid prescriptions were significantly less frequent among younger men and more frequent among middle-aged men. However, there is no clear explanation as to why this significant difference occurs only among men. Since lamotrigine prescriptions are on the rise worldwide [32, 34], it is possible that younger patients, likely new patients, were prescribed lamotrigine more frequently, while older patients on ongoing treatment were repeatedly prescribed the older mood stabilizer. There is no clear explanation for this significant discrepancy. Due to the lack of data on the duration of illness in this study, it is unclear whether the prescription data in this study started with elderly individuals. Further studies are needed to determine the actual pharmacotherapy for elderly individuals.

The daily dose of valproic acid in elderly women was significantly lower than that in middle-aged men. This may be due to the higher proportion of free valproic acid in the serum of elderly women. Approximately 90% of valproic acid is protein bound, and women and elderly individuals tend to have relatively high free valproic acid concentrations [35]. Regarding the daily dose of lithium, the present study showed that it was significantly reduced by older age and female sex. This result seems reasonable since lithium is excreted by the kidneys and creatinine clearance decreases with age and in women [12].

Regarding antipsychotics, prescription frequency was significantly rare in the older group and significantly frequent in the young group. This might be due to the upward trend in prescribing antipsychotics [31–33]. The daily dose of antipsychotics was significantly lower in the older group than in the middle-aged group. This is reasonable because of elderly patients’ lower tolerability to antipsychotics [36]. Aripiprazole, olanzapine, and quetiapine were the most often prescribed antipsychotics in our survey. A previous study in Denmark reported that aripiprazole, olanzapine, and quetiapine were the most often prescribed antipsychotics for patients with bipolar disorder [32], and our findings were similar to the results of that previous study. Lurasidone was not listed because this drug was approved in 2020 in Japan. Regarding antidepressants in our findings, the frequency of prescription was significantly rare in the older group and frequent in the middle-aged group. In addition, the daily dose of antidepressants in the older group was significantly lower than that in the middle-aged group. We do not have a clear explanation for this significant difference. This might be due to the greater risk of adverse events in elderly individuals because of multiple medical comorbidities and drug–drug interactions in the case of polypharmacy [37]. In our survey, escitalopram, duloxetine, and mirtazapine were the most often prescribed antidepressants. In some guidelines, the efficacy of adjuvant selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) therapy was reported [6, 38], but the efficacy of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) or mirtazapine therapy was not reported. Regarding BZRAs in our findings, the frequency of prescription was significantly frequent among females. Female sex is a known risk factor for long-term BZRA use [39], which is in line with our findings. In addition, BZRA prescriptions were significantly frequent in the middle-aged group and significantly rare in the young group. Because of the dependence and long-term use of BZRAs [40], prescription in the middle-aged group might have been relatively frequent.

There are several limitations of this study. First, because our study was a cross-sectional study, it could not elucidate causal relationships. Second, this study lacked structural clinical evaluations for patients. Third, there may be selection bias because the participants were not randomized. Fourth, our sample heterogeneously had bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder, which were not distinguished. Our sample was also heterogeneous in terms of current mood status, such as manic state and depressive state. Pharmacological treatment can differ according to mood status. Fifth, several potential confounding factors, such as comorbidities, willingness to become pregnant and duration of illness, were not assessed in our study. Finally, coadministration of mood stabilizers was not assessed.

Conclusion

Among young females, 25% were prescribed valproate. There was no significant difference in the frequency and daily dose of valproate prescription for young females among all groups. Lithium prescription for young females was significantly rare. Further study to correct biased information about the risk and safety of valproate and lithium for young females is needed. Among elderly individuals, lithium prescription was significantly frequent, and lamotrigine prescription was significantly rare. Further study to search for real-world pharmacological treatments for elderly individuals is needed.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1 Adjusted standardized residuals of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and benzodiazepine receptor agonists divided by age.

Additional file 2: Table S2 Adjusted standardized residuals of mood stabilizers divided by age and sex.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following psychiatrists belonging to the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics: Dr. Toshihiko Lee, Dr. Norio Okamoto, Dr. Makoto Nakamura, Dr. Junkou Sato, Dr. Kazunori Otaka, Dr. Satoshi Terada, Dr. Tadashi Ito, Dr. Munehide Tani, Dr. Atsushi Satomura, Dr. Hiroshi Sato, Dr. Hideki Nakano, Dr. Yoichi Nakaniwa, Dr. Eiichi Hirayama, Dr. Keiichi Kobatake, Dr. Koji Tanaka, Dr. Mariko Watanabe, Dr. Shiguyuki Uehata, Dr. Asana Yuki, Dr. Nobuko Akagaki, Dr. Michie Sakano, Dr. Akira Matsukubo, Dr. Yasuyuki Inada, Dr. Hiroshi Oyu, Dr. Tsuneo Tsubaki, Dr. Tatsuji Tamura, Dr. Shigeki Akiu, Dr. Atsuhiro Kikuchi, Dr. Keiji Sato, Dr. Kazuyuki Fujita, Dr. Fumio Handa, Dr. Hiroyuki Karasawa, Dr. Kazuhiro Nakano, Dr. Kazuhiro Omori, Dr. Seiji Tagawa, Dr. Daisuke Maruno, Dr. Hiroaki Furui, Dr. You Suzuki, Dr. Takeshi Fujita, Dr. Yukimitsu Hoshino, Dr. Kikuko Ota, Dr. Akira Itami, Dr. Kenichi Goto, Dr. Yoshiaki Yamano, Dr. Kiichiro Koshimune, Dr. Junko Matsushita, Dr. Takatsugu Nakayama, Dr. Kazuyoshi Takamuki, Dr. Nobumichi Sakamoto, Dr. Miho Shimizu, Dr. Muneo Shimura, Dr. Norio Kawase, Dr. Ryouhei Takeda, Dr. Takuya Hirota, Dr. Hideko Fujii, Dr. Yoichiro Watanabe, Dr. Riichiro Narabayashi, Dr. Yutaka Fujiwara, Dr. Kazu Kobayashi, Dr. Yuko Urabe, Dr. Miyako Oguru, Dr. Osamu Miura, Dr. Yoshio Ikeda, Dr. Hidemi Sakamoto, Dr. Yosuke Yonezawa, Dr. Yoichi Takei, Dr. Toshimasa Sakane, Dr. Kiyoshi Oka, Dr. Kyoko Tsuda, Dr. Shigemitsu Hayashi, Dr. Kunihiko Kawamura, Dr. Yasushi Furuta, Dr. Kazuko Miyauchi, Dr. Yoshio Miyauchi, Dr. Mikako Oyama, Dr. Keizo Hara, Dr. Misako Sakamoto, Dr. Shigeki Masumoto, Dr. Yasuhiro Kaneda, Dr. Yoshiko Kanbe, Dr. Masayuki Iwai, Dr. Naohisa Waseda, Dr. Nobuhiko Ota, Dr. Takahiro Hiroe, Dr. Ippei Ishii, Dr. Hideki Koyama, Dr. Terunobu Otani, Dr. Osamu Takatsu, Dr. Takashi Ito, Dr. Norihiro Marui, Dr. Toru Takahashi, Dr. Tetsuro Oomori, Dr. Toshihiko Fukuchi, Dr. Kazumichi Egashira, Dr. Kiyoshi Kaminishi, Dr. Ryuichi Iwata, Dr. Satoshi Kawaguchi, Dr. Yoshinori Morimoto, Dr. Hirohisa Endo, Dr. Yasuo Imai, Dr. Eri Kohno, Dr. Aki Yamamoto, Dr. Naomi Hasegawa, Dr. Sadamu Toki, Dr. Hideyo Yamada, Dr. Hiroyuki Taguchi, Dr. Hiroshi Yamaguchi, Dr. Hiroki Ishikawa, Dr. Sakura Abe, Dr. Kazuhiro Uenoyama, Dr. Kazunori Koike, Dr. Yoshiko Kamekawa, Dr. Michihito Matsushima, Dr. Ken Ueki, Dr. Sintaro Watanabe, Dr. Tomohide Igata, Dr. Yoshiaki Higashitani, Dr. Eiichi Kitamura, Dr. Junko Sanada, Dr. Takanobu Sasaki, Dr. Kazuko Eto, Dr. Ichiro Nasu, Dr. Kenichiro Sinkawa, Dr. Yukio Oga, Dr. Michio Tabuchi, Dr. Daisuke Tsujimura, Dr. Tokunai Kataoka, Dr. Kyohei Noda, Dr. Nobuhiko Imato, Dr. Ikuko Nitta, Dr. Yoshihiro Maruta, Dr. Satoshi Seura, Dr. Toru Okumura, Dr. Osamu Kino, Dr. Tomoko Ito, Dr. Ryuichi Iwata, Dr. Wataru Konno, Dr. Toshio Nakahara, Dr. Masao Nakahara, Dr. Hiroshi Yamamura, Dr. Masatoshi Teraoka, Dr. Masato Nishio, Dr. Miwa Mochizuki, Dr. Tsuneo Saitoh, Dr. Tetsuharu Kikuchi, Dr. Chika Higa, Dr. Hiroshi Sasa, Dr. Yuichi Inoue, Dr. Muneyoshi Yamada, Dr. Yoko Fujioka, Dr. Kuniaki Maekubo, Dr. Hiroaki Jitsuiki, Dr. Toshihito Tsutsumi, Dr. Yasumasa Asanobu, Dr. Seiji Inomata, Dr. Kazuhiro Kodama, Dr. Aikihiro Takai, Dr. Asako Sanae, Dr. Shinichiro Sakurai, Dr. Kazuhide Tanaka, Dr. Masahiko Shido, Dr. Haruhisa Ono, Dr. Wataru Miura, Dr. Yukari Horie, Dr. Tetso Tashiro, Dr. Tomohide Mizuno, Dr. Naohiro Fujikawa, Dr. Hiroshi Terada, Dr. Kenji Taki, Dr. Kyoko Kyotani, Dr. Masataka Hatakoshi, Dr. Katsumi Ikeshita, Dr. Keiji Kaneta, Dr. Ritsu Shikiba, Dr. Tsuyoshi Iijima, Dr. Masaru Yoshimura, Dr. Masumi Ito, Dr. Shunsuke Murata, Dr. Mio Mori, and Dr. Toshio Yokouchi.

Abbreviations

- CANMAT

The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments 2018

- KMAP-BP 2018

Korean Medical Algorithm Project for Bipolar Disorder 2018

- CINP-BD-2017

The International College of Neuropsychopharmacology Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in adults

- BZRAs

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists

- MUSUBI

The MUlticenter treatment SUrvey on Bipolar disorder in Japanese psychiatric clinics

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of this study. Dr. Kawamata analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Ken Tanaka memorial research grant (grant numbers: 2016-2, 2017-4 and 2019-3). The funder had no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The ethics committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics set restrictions on data sharing because the data contain potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Please contact the institutional review board of the ethics committee when requesting data. Contact information for our ethics committee: The institutional review board of the ethics committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics; Shibuya-ku, Yoyogi 1-38-2, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan, Postal Code 151–0053, Phone + 81-3-3320-1423.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data collection protocol for this study (ID.20160822) was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics. This protocol was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Since this was a retrospective medical survey, informed consent was not needed. However, we released information on this research so that patients were free to opt out [24].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Yasushi Kawamata has received speaker’s honoraria from Eisai. Norio Yasui-Furukori has received grant/research support or honoraria from, and received speaker’s honoraria of Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. Naoto Adachi and Kazuhira Miki declare no Conflict of Interests for this article. Hitoshi Ueda has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. Seiji Hongo has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. Takaharu Azekawa has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Eisai. Yukihisa Kubota has received consultant fees from Pfizer and Meiji-Seika Pharma and speaker’s honoraria from Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, and Eisai. Eiichi Katsumoto has received speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, UCB, and Viatris. Koji Edagawa has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Kyowa, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. Eiichiro Goto has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma. Masaki Kato has received grant funding from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology and the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and speaker’s honoraria from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Eli Lilly, MSD K.K., Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck and Ono Pharmaceutical and participated in an advisory/review board for Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Shionogi and Boehringer Ingelheim. Atsuo Nakagawa has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida, Dainippon Sumitomo and NTT Docomo, and participated in an advisory board for Takeda, Meiji Seika, Tsumura and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. Toshiaki Kikuchi has received consultant fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical and the Center for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Training. Takashi Tsuboi has received consultant fees from Pfizer and speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, MeijiSeika Pharma, MSD, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. Reiji Yoshimura has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo, Otsuka, and Esai. Kazutaka Shimoda has received research support from Novartis Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Eisai, Pfizer, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, and Takeda Pharmaceutical and honoraria from Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer. Koichiro Watanabe has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, has received research/grant support from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Viatris. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Ustun TB, et al. Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1234–1246. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, Young A, Yatham L, Blier P, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) treatment Guidelines for bipolar disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017), part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):180–195. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo YS, Bahk WM, Lee JG, Jeong JH, Kim MD, Sohn I, et al. Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Bipolar Disorder 2018 (KMAP-BP 2018): Fourth Revision. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16(4):434–448. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.4.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nora JJ, Nora AH, Toews WH. Letter: lithium, ebstein's anomaly, and other congenital heart defects. Lancet. 1974;2(7880):594–595. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, Stockton S, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721–728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61516-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Clayton-Smith J, Combs-Cantrell DT, Cohen M, et al. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1597–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veroniki AA, Rios P, Cogo E, Straus SE, Finkelstein Y, Kealey R, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs for neurological development in children exposed during pregnancy and breast feeding: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e017248. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosa FW. Spina bifida in infants of women treated with carbamazepine during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(10):674–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103073241006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun M, Herrmann N, Shulman KI. Lithium toxicity in older adults: a systematic review of case reports. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(3):201–209. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai H, Kato M, Yasui-Furukori N, Suzuki T, Baba H, Watanabe K, et al. Pharmacological management of bipolar disorder: Japanese expert consensus. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(8):822–830. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi N, Kubota Y, Goto E, Ueda H, Azekawa T, Hongo S, et al. Estimated population with affective disorders in membership clinics of the japanese association of neuro-psychiatric clinics. J Jpn Assoc Psychiatr Clin. 2016;42:957–959. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugawara N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, Azekawa T, et al. Determinants of 3-year clinical outcomes in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI) J Psychiatr Res. 2022;151:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikenouchi A, Konno Y, Fujino Y, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, et al. relationship between employment status and unstable periods in outpatients with bipolar disorder: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (musubi) study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:801–809. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S353460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinozaki M, Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Ueda H, Hongo S, Azekawa T, et al. Differences in prescription patterns between real-world outpatients with bipolar I and II disorders in the MUSUBI survey. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;67:102935. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi N, Azekawa T, Edagawa K, Goto E, Hongo S, Kato M, et al. Estimated model of psychotropic polypharmacy for bipolar disorder: Analysis using patients' and practitioners' parameters in the MUSUBI study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2021;36(2):e2764. doi: 10.1002/hup.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konno Y, Fujino Y, Ikenouchi A, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, et al. Relationship between mood episode and employment status of outpatients with bipolar disorder: retrospective cohort study from the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (musubi) project. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:2867–2876. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S322507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokumitsu K, Norio YF, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, et al. Real-world clinical predictors of manic/hypomanic episodes among outpatients with bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0262129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokumitsu K, Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, et al. Real-world clinical features of and antidepressant prescribing patterns for outpatients with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):555. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02967-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato M, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, Ueda H, Edagawa K, et al. Clinical features related to rapid cycling and one-year euthymia in bipolar disorder patients: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI) J Psychiatr Res. 2020;131:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, Goto E, Edagawa K, et al. Factors associated with doses of mood stabilizers in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18(4):599–606. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuboi T, Suzuki T, Azekawa T, Adachi N, Ueda H, Edagawa K, et al. Factors associated with non-remission in bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI) Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:881–890. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S246136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(8):440–447. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen LS, Friedman JM, Jefferson JW, Johnson EM, Weiner ML. A reevaluation of risk of in utero exposure to lithium. JAMA. 1994;271(2):146–150. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510260078033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tachibana M, Hashimoto T, Tanaka M, Watanabe H, Sato Y, Takeuchi T, et al. Patterns in psychiatrists' prescription of valproate for female patients of childbearing age with bipolar disorder in japan: a questionnaire survey. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:250. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P, Dols A, Rej S, Sajatovic M. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of mania in older-age bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(8):46. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dols A, Beekman A. Older age bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyall LM, Penades N, Smith DJ. Changes in prescribing for bipolar disorder between 2009 and 2016: national-level data linkage study in Scotland. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(1):415–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessing LV, Vradi E, Andersen PK. Nationwide and population-based prescription patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(2):174–182. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, Wilkinson ST. 20-Year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706–715. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19091000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karanti A, Kardell M, Lundberg U, Landen M. Changes in mood stabilizer prescription patterns in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowden CL. Valproate. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(3):189–202. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maixner SM, Mellow AM, Tandon R. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antipsychotics in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 8):29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kok RM, Reynolds CF., 3rd Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2114–2122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Bipolar disorder: assessment and management (CG185). London. 2018. [PubMed]

- 39.Enomoto M, Kitamura S, Tachimori H, Takeshima M, Mishima K. Long-term use of hypnotics: analysis of trends and risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;62:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soyka M. Treatment of benzodiazepine dependence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1147–1157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1611832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1 Adjusted standardized residuals of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants and benzodiazepine receptor agonists divided by age.

Additional file 2: Table S2 Adjusted standardized residuals of mood stabilizers divided by age and sex.

Data Availability Statement

The ethics committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics set restrictions on data sharing because the data contain potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Please contact the institutional review board of the ethics committee when requesting data. Contact information for our ethics committee: The institutional review board of the ethics committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics; Shibuya-ku, Yoyogi 1-38-2, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan, Postal Code 151–0053, Phone + 81-3-3320-1423.