Abstract

Background

Patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) are more likely to develop severe course of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and experience increased risk of mortality compared to SARS-CoV-2 patients without CRC.

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients and analyse the demographic parameters, clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in CRC patients with COVID-19 illness.

Methods

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched Proquest, Medline, Embase, Pubmed, CINAHL, Wiley online library, Scopus and Nature for studies on the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients, published from December 1, 2019 to December 31, 2021, with English language restriction. Effect sizes of prevalence were pooled with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sub-group analyses were performed to minimize heterogeneity. Binary logistic regression model was used to explore the effect of various demographic and clinical characteristics on patient’s final treatment outcome (survival or death).

Results

Of the 472 papers that were identified, 69 articles were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (41 cohort, 16 case-report, 9 case-series, 2 cross-sectional, and 1 case-control studies). Studies involving 3362 CRC patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 (all patients were adults) were analyzed. The overall pooled proportions of CRC patients who had laboratory-confirmed community-acquired and hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections were 8.1% (95% CI 6.1 to 10.1, n = 1308, 24 studies, I2 98%, p = 0.66), and 1.5% (95% CI 1.1 to 1.9, n = 472, 27 studies, I2 94%, p < 0.01). The median patient age ranged from 51.6 years to 80 years across studies. The majority of the patients were male (n = 2243, 66.7%) and belonged to White (Caucasian) (n = 262, 7.8%), Hispanic (n = 156, 4.6%) and Asian (n = 153, 4.4%) ethnicity. The main source of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients was community-acquired (n = 2882, 85.7%; p = 0.014). Most of those SARS-CoV-2 patients had stage III CRC (n = 725, 21.6%; p = 0.036) and were treated mainly with surgical resections (n = 304, 9%) and chemotherapies (n = 187, 5.6%), p = 0.008. The odd ratios of death were significantly high in patients with old age (≥ 60 years) (OR 1.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.96; p < 0.001), male gender (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.41–0.47; p < 0.001) CRC stage III (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.02–1.05; p = 0.041), CRC stage IV (OR 1.69, 95% CI 0.17–1.2; p = 0.009), recent active treatment with chemotherapies (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.5–0.66; p = 0.023) or surgical resections (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.8–0.73; p = 0.016) and admission to ICU (OR 1.88, 95% CI 0.85–1.12; p < 0.001) compared to those who survived.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patient is not uncommon and results in a mortality rate of 26.2%. Key determinants that lead to increased mortality in CRC patients infected with COVID-19 include older age (≥ 60 years old); male gender; Asian and Hispanic ethnicity; if SARS-CoV-2 was acquired from hospital source; advanced CRC (stage III and IV); if patient received chemotherapies or surgical treatment; and if patient was admitted to ICU, ventilated or experienced ARDS.

Keywords: SARS-Cov-2, Cancer, Colon, Colorectal, COVID-19, Rectum, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Background

Since its outbreak in China in December 2019, corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across the world to become a global pandemic. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of July 21, 2022, 562,672,324 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, with 6,367,793 deaths [1]. Established, probable, and possible comorbidities that have been associated with severe COVID-19 in at least 1 meta-analysis or systematic review, in observational studies, or in case series were: age ≥ 65 years, asthma, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease (interstitial lung disease, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), chronic liver disease (cirrhosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis), diabetes mellitus, type 1 and type 2, heart conditions (such as heart failure, coronary artery disease, or cardiomyopathies), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI 25 to 29 kg/m2), pregnancy or recent pregnancy, primary immunodeficiencies, smoking (current and former), sickle cell disease or thalassemia, solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation, tuberculosis, use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications [2–4]. In a systematic analysis that calculated the total number of community infections through seroprevalence surveys from 53 countries prior to vaccine availability, the COVID-19 infection mortality rate was 0.005 percent at 1 year, decreased to 0.002 percent by age 7, and increased exponentially after that: 0.006 percent at age 15, 0.06 percent at age 30, 0.4 percent at age 50, 2.9 percent at age 70, and 20 percent at age 90 [5].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is common and deadly disease, and globally, CRC still remains the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females [6]. CRC is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy and disproportionately affects medically underserved populations [7]. Patients with CRC are more likely to develop severe course of severe acute respiratorcy syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and experience increased risk of mortality compared to SARS-CoV-2 patients without CRC [8–16]. Higher mortality rates in CRC patients infected with COVID-19 case-series and cohort studies were reported; for instance, in two small Chinese case-series, rates of death reached up to 61.5 to 70% [11, 15], and in a large French cohort (a total of 376 CRC patients infected with COVID-19 cases), mortality rate was 37.8% [8]; and there was a lower proportion of death of all hospitalized CRC patients infected with COVID-19 based on two different studies in China (5.9%) and Turkey (6.4%) [14, 17]. The recent UK Coronavirus Cancer Monitoring Project (UKCCMP) prospective cohort study of 2,515 patients conducted at 69 UK cancer hospitals among adult patients (≥ 18 years) with an active cancer and COVID-19 reported a 38% (966 patients) mortality rate with an association between higher mortality in patients with haematological malignant neoplasms, particularly in those with acute leukaemias or myelodysplastic syndrome (OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.30–3.60) and myeloma or plasmacytoma (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.04–2.26) [18]. Lung cancer was also significantly associated with higher COVID-19-related mortality (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.11–2.25) [18]. A possible reason for increased mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with CRC is because most health care systems have been required to reorganize their infrastructure and staffing to manage the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. The pandemic has called for a review of healthcare workers daily medical practices, including our approach to CRC management where treatment puts patients at high risk of virus exposure. Given their higher median age, CRC patients are at an increased risk for severe symptoms and complications in cases of infection, especially in the setting of immunosuppression. Considering that the reduction in CRC screening following SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is due to the restrictions imposed for the high prevalence of COVID-19 illness and the lack of referrals due to the fear of developing SARS-CoV-2 infection [20–22] (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A caricature depicts surgeon’s worriment about contracting the SARS-CoV-2 and patient’s possible risk of getting post-surgical SARS-CoV-2 infection in a CRC patient

To date, some studies have been performed to evaluate the SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients, but the results of these studies were inconsistent because most of these are single-centre studies with limited sample sizes [23–36]. In light of newer case reports, case-series and cohort studies that were done to re-evaluate the development of COVID-19 disease in CRC patients, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients and analyse the demographic parameters, clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in CRC patients with COVID-19 illness with larger and better-quality data.

Methods

Design

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) in conducting this systematic review and meta-analysis [37]. The following electronic databases were searched: PROQUEST, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED, CINAHL, WILEY ONLINE LIBRARY, SCOPUS and NATURE with Full Text. We used the following keywords: COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Severe acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 OR Coronavirus Disease 2019 OR 2019 novel coronavirus AND colorectal cancer OR colon OR rectal OR rectum OR CRC OR bowel cancer OR tumor OR cancer OR neoplasm. The search was limited to papers published in English between 1 December 2019 and 31 December 2021. Based on the title and abstract of each selected article, we selected those discussing and reporting occurrence of CRC in COVID-19 patients.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) published case reports, case series and cohort studies that focused on COVID-19 in CRC patients that included children and adults as our population of interest; (2) studies of experimental or observational design reporting the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CRC; (3) the language was restricted to English.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) editorials, commentaries, case and animal studies, discussion papers, preprints, news analyses, reviews and meta-analyses; (2) studies that did not report data on CRC and SARS-CoV-2; (3) studies that never reported details on SARS-CoV-2 identified cases with CRC; (4) studies that reported CRC in patients with negative COIVD-19 PCR tests; (5) duplicate publications.

Data extraction

Six authors critically reviewed all of the studies retrieved and selected those judged to be the most relevant. Data were carefully extracted from the relevant research studies independently. Articles were categorized as case report, case series, cross-sectional, case–control or cohort studies. The following data were extracted from selected studies: authors; publication year; study location; study design and setting; age; proportion of male patients; patient ethnicity; methods used for CRC diagnosis; total number of patients and number of CRC patients with positive PCR SARS-CoV-2; source of SARS-CoV-2 infection [community-acquired or hospital-acquired]; CRC staging; treatments received; symptoms from tumor; comorbidities; if patient was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU), placed on mechanical ventilation, and/or suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); assessment of study risk of bias; and treatment outcome (survived or died); which are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies with evidence on colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 69 studies), 2020–2021

| Author, year, study location | Study design, setting | Age (years)a | Male, n (%) | Ethnicityb | CRC diagnosed through | Number of patients (n = 98,131) | Number of SARS-CoV-2 patients with CRC (%) [n = 3362, 3.43%] | Source of SARS-CoV-2 infection | CRC Staging | Treatment, n | Symptoms from the tumor, n | Comorbidities, n | Admitted to ICU, n | Mechanical ventilation, n | ARDS, n | NOS score; and Treatment outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Shamsi et al. 2020 [23], United Arab Emirates | Prospective, cohort, single centre | 51.6 (40-76) | 1 (50) | 2 Arabs | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 85 | 2 | Community-acquired | Not reported | 2 Chemotherapies | Not reported | Not reported | 1 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Aschele et al. 2021 [43], Italy | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 68 (28–89) | Not reported | 38 Whites, (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 406 | 38 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

28 Chemotherapies 16 Monoclonal antibodies: [CRC use (n = 5) and COVID-19 use (n = 11)] Immunotherapies 0 Targeted therapies 3 Hormones |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Ayhan et al. 2021 [44], Turkey | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 61.0 (21–84) | Not available | 11 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 84 | 11 | Community-acquired |

Stage I (n = 1) Stage II (n = 3) Stage III (n = 1) Stage IV (n = 6) |

8 Chemotherapies 5 Targeted therapies 2 Immunotherapies |

Not reported |

3 Hypertension 5 Diabetes mellitus 2 Coronary artery disease 1 COPD 1 Chronic renal failure |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Aznab 2020 [45], Iran | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | 72 Persians | Not reported | 279 | 72 | Community-acquired |

Stage II (n = 11) Stage III (n = 36) Stage IV (n = 25) |

72 Chemotherapies 25 Monoclonal antibodies: [CRC use (n = 9) and COVID-19 use (n = 16)] |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 71 survived 1 died |

| Berger et al. 2021 (25), Austria | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 23 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported |

1 Chemotherapy 1 Targeted therapy 1 Immunotherapy |

Not reported | No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Bernard et al. 2021 [8], France | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 73 (64–82) | Not reported | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 6201 | 518 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not possible to extract | 67 | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 8) 376 survived 142 died |

| Binet et al. 2021 [46], Belgium | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 62 | 0 (0) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | 1 Colectomy |

1 Abdominal pain 1 Nausea and vomiting |

1 Hypertension 1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Dyslipidaemia 1 Acute ischemic stroke |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 died |

| Calvo et al. 2021 [47], Spain | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 63.9 ± (10.2) | 3 (60) | 5 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 653 | 5 | Hospital- acquired | Stage IV (n = 3) |

3 Chemotherapies 2 Radiotherapies 3 Steroids 3 Antivirals 3 HCQ 3 Surgical resections 1 Immunotherapies |

Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 6) 3 survived 2 died |

| COVIDSurg Collaborative 2021 [9], 40 countries | Prospective, cohort, multicentre | < 50: n = 174; 50–69: n = 966; AND ≥ 70: n = 933 | 1236 (59.6) | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 2073 | 78 | Hospital- acquired |

Stage I-II (n = 838) Stage III (n = 653) Stage IV (n = 133) |

38 Surgical resections | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 7) 63 survived 15 died |

| Cosma et al. 2020 [48], Italy | Retrospective, case report, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | Not reported | Not reported | No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 5) 1 survived |

| Costanzi et al. 2020 [49], Italy | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 62 | 0 (0) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Surgical resection 1 Chemotherapy 1 Ileostomy 1 Antivirals 1 Antibiotics 1 HCQ 1 RBC transfusion |

1 Haematochezia (blood per anus) 1 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) 1 Blood per rectum 1 Weight loss |

No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Filipe et al. 2021 [26], The Netherlands | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | - | - | 2 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 21 | 2 | Hospital- acquired |

Stage II (n = 1) Stage IV (n = 1) |

2 Chemotherapies 2 Surgical resections |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 7) 1 survived 1 died |

| Gao et al. 2020 [50], China | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 69 | 0 (0) | 1 Asian | Symptoms and exploratory laparotomy | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

1 Colectomy 1 Lymph node dissection |

1 Abdominal pain 1 Change in bowel habits 1 Weight loss |

No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Glasbey et al. 2021 [51], 55 countries | Prospective, cohort, multicentre | - | - | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 2310 | 134 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported | 134 Surgical resections | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 7) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Haque et al. 2021 [52], United Kingdom | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 69 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, CT and colonoscopy | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

1 RBC transfusions 1 Antibiotics 1 Tranexamic acid 1 Palliative haemostatic radiotherapy |

1 Melena (black tarry stools) 1 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) |

1 Lynch Syndrome 1 Pancolectomy 1 Ileo-rectal anastomosis 1 Adenocarcinoma 1 Nephroureterectomy 1 Recurrent VTE |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Huang et al. 2020 [141], China | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 48 | 1 (100) | 1 Asian | Symptoms, and CT | 1 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Stage II (n = 1) |

1 Sigmoidectomy 1 Colonic decompression 1 Anastomosis 1 Ileostomy |

1 Abdominal pain 1 Constipation |

1 Hepatitis B virus | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Joharatnam-Hogan et al. 2020 [53], United Kingdom | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 76 (72–77.5) | 4 (80) |

4 Whites (Caucasi ans) 1 Black |

Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 699 | 5 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported |

2 Chemotherapies 1 Colectomy 2 Surgical resections 1 Radiotherapy |

3 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 5 survived |

| Johnson et al. 2020 [54], United States | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 63 | 1 (100) | 1 Asian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Chemotherapy 1 Hepatectomy |

Not reported |

1 Lynch syndrome 1 Colon, liver, and thyroid cancer 1 Hepatitis C virus |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Karam et al. 2020 [55], Australia | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 66 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, and CT | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

1 Antibiotics 1 Surgical debridement 1 Colostomy |

1 Haematochezia (blood per anus) 1 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) 1 Change in bowel habits |

1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Renal impairment 1 Chronic anaemia 1 Diabetic ketoacidosis |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Khan et al. 2021 [27], United Kingdom | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 78 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 8 | 1 | Hospital- acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | 1 Conservative treatment |

1 Abdominal pain 1 Change ion bowel habits |

1 Heart failure 1 Chronic kidney disease | 1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 1 died |

| Kuryba et al. 2021 [56], United Kingdom | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre |

60–74: 43.05%; AND 50–69: 26.3% |

54 (55.6) | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 3227 | 97 | Hospital- acquired |

Stage I (n = 30) And Stage ≥ II (n = 23) |

83 Surgical resections 33 Colectomies 6 Hartmann’s procedure 5 Stomas 2 Stents |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Kumar et al. 2020 [68], India | Ambispective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | 10 Indians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 107 | 10 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported |

4 Radiotherapies 8 Chemotherapies 10 Surgeries 2 Palliative managements 1 Stoma closure |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 10 survived |

| Larfors et al. 2021 [10], Sweden | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | Not reported | Not reported | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 54,651 | 50 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported | 22 Chemotherapies | Not reported | Not reported | 50 | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 50 died |

| Liang et al. 2020 [57], China | Prospective, cohort, multicentre | 67.5 (53.7–85) | 4 (100) | 4 Asians | Not reported | 1590 | 4 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported |

3 Surgical resections 3 Chemotherapies |

Not reported |

1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension 1 COPD |

2 | 2 | Not reported |

(NOS, 7) 2 survived 2 died |

| Liu et al. 2020 [28], China | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 65.5 (54.5–73.0) | 3 (60) | 6 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 52 | 5 | Hospital- acquired | Not reported |

5 Surgical resections 2 Sigmoidectomies 1 Colectomy 1 Hartmann's procedure |

1 Abdominal pain 2 Diarrhoea |

3 Hypertension 1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Tuberculosis |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 4 survived 1 died |

| Liu et al. 2021 [58], China | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | All patients were > 60 | 3 (60) | 5 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 189 | 5 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

5 Surgical resections 2 Chemotherapies 1 Targeted therapy |

1 Abdominal pain 3 Change in bowel habits 1 Nausea and vomiting 2 Diarrhoea |

2 Hypertension 2 Diabetes 1 Coronary heart disease |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 4 survived 1 died |

| Liu et al. 2021 [17], China | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 65.06 ± (11.51) | 23 (63.9) | 36 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 81 | 36 | Community-acquired |

Stage I (n = 5) Stage II (n = 7) Stage III (n = 11) Stage IV (n = 7) |

21 Conservative treatment 4 Chemotherapies 4 Surgeries 32 Antivirals 28 Antibiotics 16 Steroids 10 IgG |

7 Change in bowel habits 9 Diarrhoea |

9 Diabetes mellitus 18 Hypertension 3 Cardiovascular disease 4 Cerebrovascular disease 3 COPD |

6 | 5 | 8 |

(NOS, 6) 34 survived 2 died |

| Liu et al. 2021 [58], China | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | > 65: n = 3; AND ≤ 65: n = 2 | 3 (60) | 5 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 135 | 5 | Community-acquired | Stage I (n = 2); Stage II (n = 2); and Stage III (n = 1) |

4 Antibiotics 3 Antivirals 3 Immunomodulator 4 Systemic glucocorticoids |

Not reported |

1 Diabetes mellitus 3 Hypertension 1 Coronary heart disease 1 Renal disease |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 8) 4 survived 1 died |

| Ma et al. 2020 [11], China | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 62 (59–70) | 6 (54.5) | 11 Asians | Not available | 1380 | 11 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

4 Surgeries 3 Radiotherapies 7 Chemotherapies 2 Targeted therapies 2 Immunotherapies |

2 Haematochezia (blood per anus) 3 Diarrhoea |

3 Diabetes mellitus 2 Hypertension 1 COPD |

4 | 4 | 4 |

(NOS, 7) 7 survived 4 died |

| Manlubatan et al. 2021 [59], Philippines | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 75 | 1 (100) | 1 Asian | Symptoms, and CT | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Abdominotransanal resection 1 Total mesorectal excision 1 Intersphincteric resection 1 Stoma was created |

1 Haematochezia (blood per anus) 1 Melena (black tarry stools) 1 Change in bowel habits 1 Blood per rectum 1 Weight loss |

No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 died |

| Mansi et al. 2021 [29], France | Prospective, cohort, multicentre | 70.5 (69–70.5) | 1 (50) | 2 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 28 | 2 | Community-acquired |

Stage III (n = 1) Stage IV (n = 1) |

2 Chemotherapies 1 Monoclonal antibody: [CRC use (n = 1)] |

Not reported | 1 Dyslipidemia | 1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 7) 1 survived 1 died |

| Martín-Bravo et al. 2021 [60], Spain | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 64 (52–64) | 1 (50) | 2 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 673 | 2 | Hospital-acquired | Stage IV (n = 2) |

2 Chemotherapies 2 Surgical resections 2 Palliative treatments 1 Immunotherapy 1 Targeted therapy 1 Radiotherapy |

Not reported | No comorbidities | 1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived 1 died |

| Martínez et al. 2021 [61], Spain | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 77 (57-80) | 2 (66.7) | 3 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 32 | 3 | Hospital-acquired | Stage II (n = 3) |

1 Sigmoidectomy 1 Hartmann procedure 1 Colostomy 1 Laparoscopic approach 1 Stoma creation |

1 Melena (black tarry stools) 1 Diarrhoea |

1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension 1 COPD |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 7) 3 survived |

| Martínez-Mardones et al. 2021 [30], Chile | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 72 | 1 (100) | 1 Hispanic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 16 | 1 | Hospital-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | Not reported |

1 Haematochezia (blood per anus) 1 Weight loss |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 5) 1 survived |

| McCarthy et al. 2020 [12], 2 countries | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 80 (71.5–86.5) | - | Multi-ethnic | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | Not reported | 1564 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 1139 survived 425 died |

| Mehta et al. 2020 [62], United States | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 50–60: n = 1; 60–70: n = 3; 70–80: n = 1; 80–90: n = 2 | 6 (85.7) | Multi-ethnic | Not reported | 218 | 21 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

2 Morbid obesity 2 Congestive heart failure 2 Hypertension 1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Coronary artery disease 1 Chronic kidney disease 1 Hepatitis C virus 1 COPD 1 Malabsorption |

5 | 5 | 7 |

(NOS, 6) 13 survived 8 died |

| Miyashita et al. 2020 [63], United States | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | Multi-ethnic | Not reported | 334 | 16 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 7) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Montopoli et al. 2020 [64], Italy | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | Not reported | Not reported | Multi-ethnic | Not reported | 9280 | 65 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 7) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Nagarkar et al. 2021 [65], India | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | 53 Indians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 458 | 53 |

46 Community-acquired 7 Hospital-acquired |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 6) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Nakamura et al. 2021 [31], Japan | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 70.5 (54–70.5) | 1 (50) | 2 Asian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 32 | 2 | Hospital-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

2 Antivirals 2 Steroids 2 Chemotherapies 2 Surgical resections |

Not reported |

2 Hypertension 1 Coronary heart disease 1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Asthma |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived 1 died |

| Ospina et al. 2021 [13], Colombia | Ambispective, cohort, multicentre | 50–60: 23.34%; 61–70: 22.24%; AND > 70: 27.22% | Not reported | 92 Hispanics | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 742 | 92 | Community-acquired |

Stage I (n = 37) Stage II (n = 21) Stage III (n = 10) Stage IV (n = 24) |

Not possible to extract | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 19 | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 64 survived 28 died |

| Ottaiano et al. 2021 [32], Italy | Retrospective, case reports, single centre | 60 (58–60) | 2 (66.7) | 3 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 3 | 3 | Hospital-acquired |

Stage III (n = 2) Stage IV (n = 1) |

3 Chemotherapies 3 Colectomies 1 Monoclonal antibody: [CRC use (n = 1)] |

Not reported |

1 Peritoneal disease 1 Lung disease |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 3 survived |

| Özdemir et al. 2021 [14], Turkey | Ambispective, cohort, multicentre | 61 (19–94) | 771 (50.6) | 165 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1523 | 165 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 6) 155 survived 10 died |

| Pawar et al. 2020 [66], India | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 28 | 0 (0) | 1 Indian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Not reported | 1 Laparoscopic anterior resection | 1 Blood per rectum | No comorbidities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 5) 1 survived |

| Pertile et al. 2021 [33], Italy | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 76 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 25 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 RBC transfusions 1 Laparotomy 1 Rectal resection 1 Radical cystectomy 1 Right ureterostomy 1 Segmental small bowel resection 1 Lumbar-aortic lymphadenectomy 1 HCQ 1 Antibiotics |

1 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) 1 Blood per rectum |

1 Chronic renal failure 1 Bilateral ureteral stenting 1 Hypertension 1 Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 1 died |

| Pordány et al. 2020 [67], Hungary | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 75 | 0 (0) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | 1 Colectomy | Not reported | 1 Cardiac arrest | 1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 5) 1 survived |

| Quaquarini et al. 2020 [34], Italy | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 60 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 7 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) | 1 Chemotherapy | Not reported |

1 Hypertension 1 Cardiac failure 1 Renal failure 1 Rheumatoid arthritis |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 7) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Robilotti et al. 2020 [69], United States | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Most patients were adults over the age of 60 years | Not reported | Not reported | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 2035 | 37 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not reported |

(NOS, 8) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Ruiz-Garcia et al. 2021 [70], Mexico | Prospective, cohort, multicenter | Not reported | Not reported | 56 Hispanics | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 599 | 56 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not possible to extract |

16 Abdominal pain 11 Nausea and vomiting |

Not possible to extract | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Serrano et al. 2020 [71], Spain | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 78 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

1 Antivirals 1 HCQ 1 Interferon beta-1b |

Not reported |

1 Hypertension 1 Chronic kidney disease |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Sobrado et al. 2021 [72], Brazil | Retrospective, cross-sectional, single centre | 72 (67–72) | 3 (60) | 5 Hispanics | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 103 | 5 | Hospital-acquired |

Stage III (n = 2) Stage IV (n = 3) |

4 Surgical resections 2 Colectomies 1 Adrenalectomy 1 Colostomy closure 1 Hartmann’s procedure reversal |

1 Abdominal pain 1 Change in bowel habits |

2 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension 1 Mesenteric ischemia 1 Pulmonary embolism |

3 | 3 | 3 |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived 3 died |

| Sorrentino et al. 2020 [73], Italy | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | Not reported | Not reported | 3 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | Not reported | Not reported | Hospital-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived 1 died |

| Sukumar et al. 2020 [74], India | Prospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | 63 (70) | 1 Indian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 90 | 1 | Hospital-acquired | Stage II (n = 1) |

1 Surgical resection 1 Chemotherapy |

Not reported |

1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Tateno et al. 2021 [75], Japan | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 63 | 1 (100) | 1 Asian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage II (n = 1) |

1 Colectomy 1 Antibiotics 1 Antivirals |

Not reported | 1 Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Taya et al. 2021 [76], United States | Retrospective, cross-sectional, single centre | 63 (63–68) | 3 (30) | 7 Whites (Caucasians) 3 Blacks | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 745 | 10 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Tejedor et al. 2021 [77], Spain | Prospective, cohort, multicentre | 76.5 (69–76.5) | 3 (100) | 3 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 301 | 3 | Hospital-acquired |

Stage II (n = 2) Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Chemotherapy 1 Surgical resection 1 Sigmoidectomy 1 Colectomy |

Not reported |

1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension |

2 | 0 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived 1 died |

| Tolley et al. 2020 [35], United Kingdom | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | 67.5 (55–84) | 2 (66.7) | 3 Whites (Caucasians) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 21 | 3 | Hospital-acquired |

Stage III (n = 2) Stage IV (n = 1) |

3 Surgeries | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived 1 died |

| Tolley et al. 2020 [78], United Kingdom | Retrospective, case-series, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 21 | 3 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived 1 died |

| Tuech et al. 2021 [79], France | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 461 | 6 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

3 Hypertension 2 Diabetes mellitus 1 COPD 1 Chronic kidney disease |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 6 survived |

| Vicente et al. 2021 [80], Brazil | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 64 (62–64) | 1 (50) | 2 Hispanics | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 41 | 2 | Hospital-acquired | Stage II (n = 2) |

2 Sigmoidectomies 1 Chemotherapy 1 Radiotherapy 1 Ileostomy |

Not reported |

1 Morbid obesity 1 Diabetes mellitus 1 Hypertension |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 2 survived |

| Wang et al. 2021 [81], United States | Retrospective, case–control, multicentre | Not reported | Not reported | Multi-ethnic | Not reported | 1200 | 60 | Community-acquired | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not possible to extract | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

(NOS, 8) Treatment outcome was not available |

| Wang et al. 2020 [15], China | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 63 (55–70) | 26 (76.5) | 34 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 283 | 34 | Community-acquired | Most patients were stage I (n = 20) | Not possible to extract |

11 Change in bowel habits 7 Nausea and vomiting 6 Diarrhoea |

Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 5) 20 survived 14 died |

| Woźniak et al. 2021 [82], Poland | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 56 | 1 (100) | 1 White (Caucasian) | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1 | 1 | Community-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Chemotherapy 1 Sigmoidectomy |

1 Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) 1 Weight loss |

1 Coronary heart disease 1 Myocardial infarction 1 Coronary artery angioplasty 1 Polyneuropathy |

0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Wu et al. 2020 [36], China | Retrospective, case-series, multicenter | 29 | 0 (0) | 1 Asian | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 11 | 1 | Hospital-acquired | Stage IV (n = 1) |

1 Surgery 1 Immunotherapy 1 Antibiotics 1 Chemotherapy |

Not reporter | No comorbidities | 1 | 1 | 0 |

(NOS, 6) 1 died |

| Yang et al. 2020 [16], China | Retrospective, cohort, multicenter | 63 (56–70) | Not reported | 28 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 205 | 28 | Community-acquired |

Stage I-II (n = 20) Stage III-IV (n = 6) |

Not possible to extract | Not reported |

11 Hypertension 8 Diabetes mellitus 1 Coronary heart disease 1 Hepatitis B virus |

Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract | Not possible to extract |

(NOS, 8) 22 survived 6 died |

| Yang et al. 2020 [83], China | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | Not reported | Not reported | 11 | ||||||||||||

| Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1575 | 13 | Community-acquired | Not reported |

13 Antivirals 12 Antibiotics 5 Chemotherapies 3 Steroids 2 Surgical resections 1 Immunotherapy |

1 Nausea and vomiting 1 Diarrhoea |

8 Hypertension 6 Diabetes mellitus 2 Coronary heart disease 1 COPD 1 Cerebrovascular disease |

2 | 2 | 2 |

(NOS, 6) 11 survived 2 died |

||||

| Ye et al. 2020 [84], China | Retrospective, case report, single centre | 62 | 1 (100) | 1 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, and radiological imaging | 1 | 1 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported |

1 Colectomy 1 Antibiotics 1 Antivirals 1 Antifungals |

Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 5) 1 survived |

| Yu et al. 2020 [83], China | Retrospective, cohort, single centre | 66 (48–78) | 2 (100) | 2 Asians | Not reported | 1524 | 2 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported |

1 Best supportive care 1 Newly diagnosed; treatment yet to commence |

Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Zhang et al. 2020 [85], China | Retrospective, cohort, multicentre | 77.5 (75–77.5) | 2 (100) | 2 Asians | Symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers | 1276 | 2 | Hospital-acquired | Not reported |

2 Antivirals 2 Antibiotics 1 Surgical operation 1 Chemotherapy 1 Steroids |

1 Diarrhoea |

1 Hypertension 1 Coronary heart disease 1 COPD |

1 | 1 | 1 |

(NOS, 6) 1 survived 1 died |

ARDS Acute respiratory distress syndrome, COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CRC Colorectal carcinoma, CT Computerized tomography, HCQ Hydroxychloroquine, ICU Intensive care unit, IgG Immunoglobulin G, IV Intravenous, NOS Newcastle ottawa scale, RBC Red blood cell, SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, VTE Venous thromboembolism

aData are presented as median (25th–75th percentiles), or mean ± (SD)

bPatients with black ethnicity include African-American, Black African, African and Afro-Caribbean patients

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the studies was undertaken based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the quality of the selected studies [38]. This assessment scale has two different tools for evaluating case–control and cohort studies. Each tool measures quality in the three parameters of selection, comparability, and exposure/ outcome, and allocates a maximum of 4, 2, and 3 points, respectively [38]. High-quality studies are scored greater than 7 on this scale, and moderate-quality studies, between 5 and 7 [38]. Quality assessment was performed by six authors independently, with any disagreement to be resolved by consensus.

Data analysis

We examined primarily the proportion of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CRC. This proportion was further classified based on source of SARS-CoV-2 infection (if CRC patient contracted SARS-CoV-2 from the community or hospital). Community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection is the infection that CRC patients contracted outside the hospital (i.e., SARS-CoV-2 infection that become clinically apparent within 48 h of the hospital admission or CRC patients have had the infection when admitted to the hospital for some other reason) [39]. Hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection is the infection that CRC patients contracted within the hospital, the SARS-CoV-2 infections contracted within the hospital but not become clinically apparent until after the discharge of the CRC patient, or SARS-CoV-2 infections contracted by the healthcare workers as a result of their direct or indirect contact with the CRC patients [39]. Taking a conservative approach, a random effects with the DerSimoniane-Laird model was used [40], which produces wider confidence intervals (CIs) than a fixed effect model. Results were illustrated using forest plots. The Cochran’s chi-square (χ2) and the I2 statistic provided the tools of examining statistical heterogeneity [41]. An I2 value of > 50% suggested significant heterogeneity [42]. Examining the source of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was conducted based on study location (if continent of Asia, America, Europe or multi-countries).

Individual CRC patient data on demographic parameters and clinical variables and associated treatment outcomes (survived or died) were extracted from the included studies. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis were used to estimate odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs of the association of each variable with the treatment outcomes of CRC patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. All p-values were based on two-sided tests and significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05. R version 4.1.0 with the packages finalfit and forestplot was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Study characteristics and quality

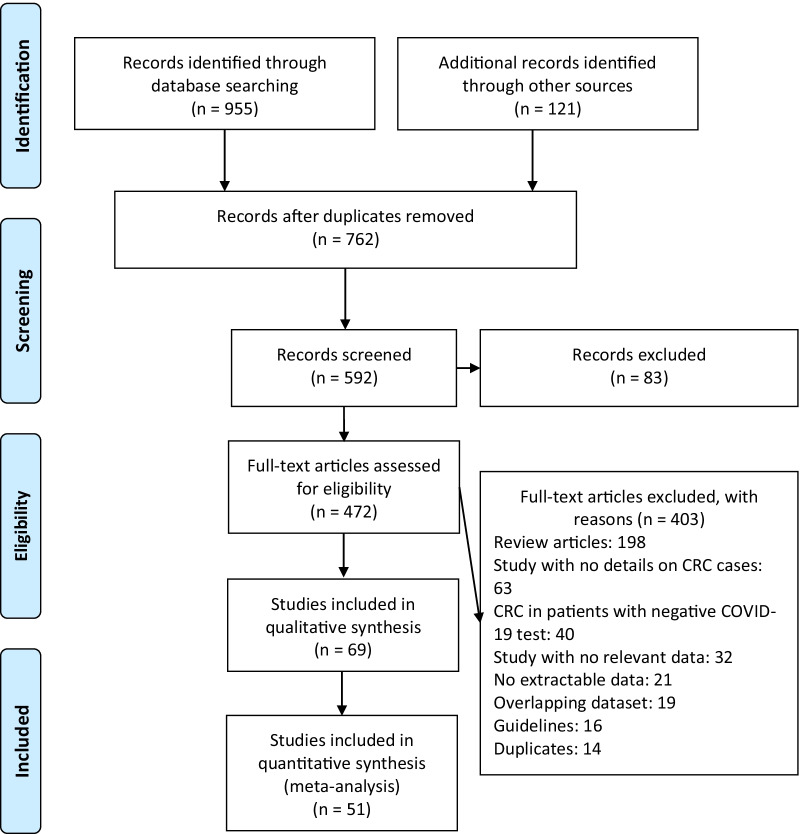

A total of 1076 publications were identified (Fig. 2). After scanning titles and abstracts, we discarded 314 duplicate articles. Another 83 irrelevant articles were excluded based on the titles and abstracts. The full texts of the 472 remaining articles were reviewed, and 403 irrelevant articles were excluded. As a result, we identified 69 studies that met our inclusion criteria and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients [8–17, 23, 25–36, 43–85]. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. There were 16 case report [16, 32, 46, 48–50, 52, 54, 55, 59, 66, 67, 71, 75, 82, 84], 9 case series, 41 cohort [8–17, 23, 25, 26, 29, 31, 34, 43–45, 51, 53, 56–58, 60–65, 68–70, 73, 74, 77, 79, 80, 83, 85], 2 cross-sectional [72, 76] and 1 case–control [81] studies. These studies were conducted in China (n = 15), Italy (n = 8), United States (n = 6), United Kingdom (n = 6), Spain (n = 5), India (n = 4), France (n = 3), Turkey (n = 2), Brazil (n = 2), Japan (n = 2), Colombia (n = 1), Philippines (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1), United Arab Emirates (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), Hungary (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), and Chile (n = 1). Few studies were made within multi-countries (n = 3) [9, 12, 51]. The majority of the studies were single centre [11, 16, 23, 25, 27, 28, 30–35, 44–50, 52, 54, 55, 58, 59, 61–63, 65–69, 71, 72, 74–76, 78, 80, 82–84] and only 25 studies were multi-centre [8–10, 12–17, 26, 29, 36, 43, 51, 53, 56, 57, 60, 64, 70, 73, 77, 79, 81, 85]. The median NOS score for these studies was 6 (range, 5–7). Among the 69 included studies, 64 studies were moderate-quality studies (i.e., NOS scores were between 5 and 7) and 5 studies demonstrated a relatively high quality (i.e., NOS scores > 7); Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of literature search and data extraction from studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CRC

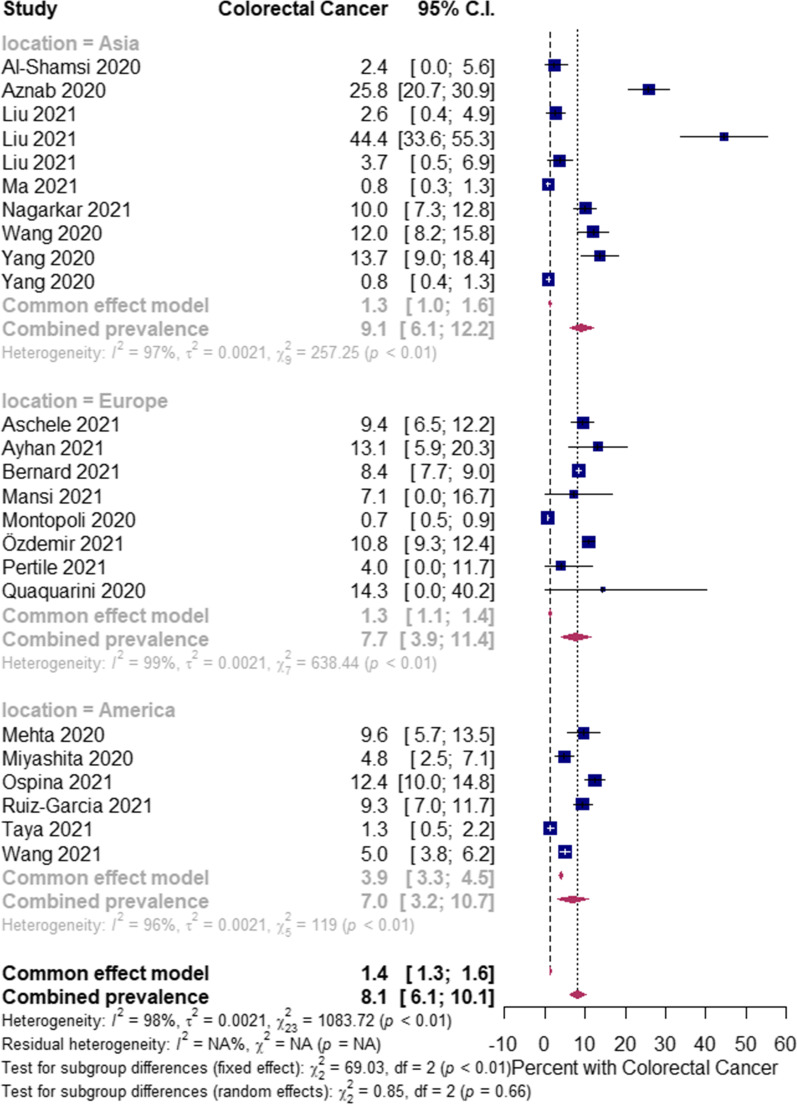

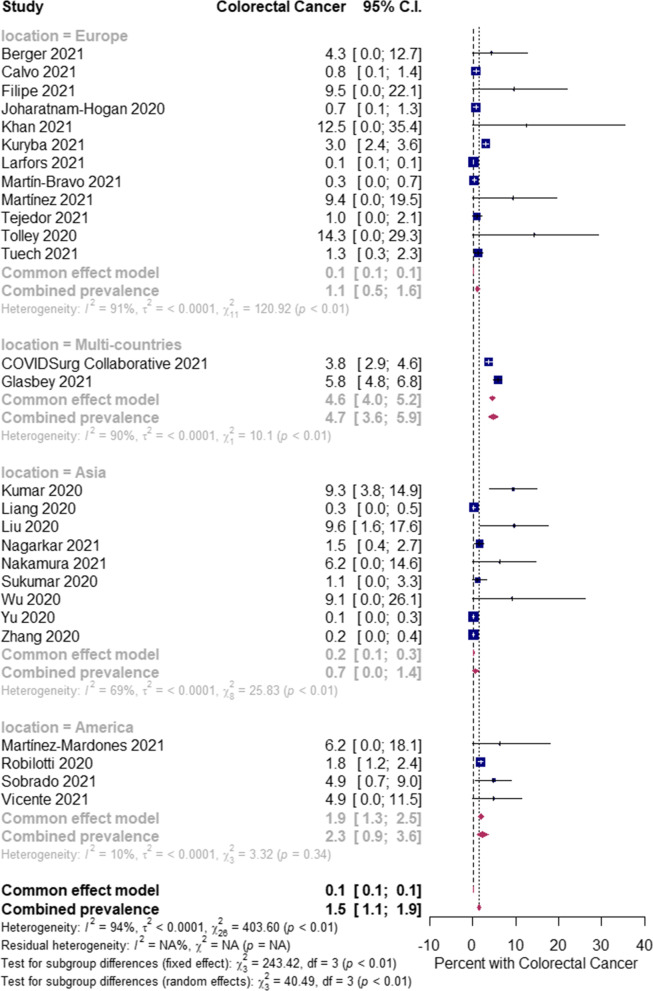

The overall pooled proportions of CRC patients who had laboratory-confirmed community-acquired and hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections were 8.1% (95% CI 6.1 to 10.1, n = 1308, 24 studies, I2 98%, p = 0.66), and 1.5% (95% CI 1.1 to 1.9, n = 472, 27 studies, I2 94%, p < 0.01), respectively; (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Pooled estimate for the prevalence of community-acquired COVID-19 infection in colorectal cancer patients stratified by the study location type

Fig. 4.

Pooled estimate for the prevalence of hospital-acquired COVID-19 infection in colorectal cancer patients stratified by the study location type

In community-acquired infected SARS-CoV-2 patients, subgroup analysis showed some difference in the rates between all patients (Asia, Europe and America groups) [8, 11, 13–17, 23, 28, 29, 33, 34, 43–45, 58, 62–65, 70, 76, 81, 86]; and the Asia group [(9.1% (95% CI 6.1 to 12.2, n = 252, 10 studies, I2 = 97%)] [11, 15–17, 23, 28, 45, 58, 65, 86]; Europe group [(7.7% (95% CI 3.9 to 11.4, n = 801, 8 studies, I2 = 99%)] [8, 14, 29, 33, 34, 43, 44, 64]; and America group [7.0% (95% CI 3.2 to 10.7, n = 229, 6 studies, I2 = 96%)] [13, 62, 63, 70, 76, 81], respectively; Fig. 3. In the hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, subgroup analysis showed a significant difference in the rates between all patients (Europe, multi-countries, Asia and America) [9, 10, 25–28, 30, 31, 35, 36, 47, 51, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61, 65, 68, 69, 72, 74, 77, 79, 80, 83, 85]; and Europe only patients [1.1% (95% CI 0.5 to 1.6, n = 178, 12 studies, I2 = 91%)] [10, 25–27, 35, 47, 53, 56, 60, 61, 77, 79]; multi-countries only patients [4.7% (95% CI 3.6 to 5.9, n = 212, 2 studies, I2 = 90%)] [9, 51]; Asia only patients [0.7% (95% CI 0.0 to 1.4, n = 32, 9 studies, I2 = 69%)] [28, 31, 36, 57, 65, 68, 74, 83, 85]; and America only patients [2.3% (95% CI 0.9 to 3.6, n = 32, 4 studies, I2 = 10%)] [30, 69, 72, 80], respectively; Fig. 4.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of CRC patients with SARS‑CoV‑2 infection

The included studies had a total of 3362 CRC patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection as detailed in Table 1. Amongst these 3362 patients, all patients were adults. The median patient age ranged from 51.6 years to 80 years across studies. There was an increased male predominance in CRC patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 in most of the studies [n = 2243, 66.7%] [9, 11, 14, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32–35, 47, 52–59, 61, 62, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77, 81–85] and majority of the patients belonged to White (Caucasian) (n = 262, 7.8%), Hispanic (n = 156, 4.6%) and Asian (n = 153, 4.5%) ethnicity [11, 13–17, 25–34, 36, 43, 44, 46–50, 52–55, 57–61, 67, 70–73, 75–78, 80, 81, 83–85]. Most patients were diagnosed for CRC through symptoms, endoscopy, radiological imaging, biopsies and tumor markers [8–10, 12–14, 16, 17, 23, 25–36, 43, 44, 46–56, 58–61, 65–77, 80–85]. The main source of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients was community-acquired (n = 2882, 85.7%; p = 0.014) [8, 11–17, 23, 28, 29, 33, 34, 43–45, 48, 50, 52, 55, 58, 59, 62–67, 70, 71, 75, 76, 81–83]. Most of those SARS-CoV-2 patients had stage III CRC (n = 725, 21.6%; p = 0.036) [9, 13, 17, 35, 45, 72, 83]; and were treated mainly with surgical resections (n = 304, 9%) and chemotherapies (n = 187, 5.6%), p = 0.008 [9–11, 16, 17, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31–36, 43–45, 47, 49, 51, 53, 54, 56–58, 60, 61, 68, 72, 74, 77, 80, 82, 85]. The most common tumor symptoms patients experienced were change in bowel habits (n = 26, 0.8%), diarrhoea (n = 25, 0.7%), abdominal pain (n = 23, 0.7%), and nausea and vomiting (n = 21, 0.6%); p = 0.048 [11, 16, 17, 27, 46, 50, 55, 58, 61, 70, 72, 81]. Many of the CRC patients infected with COVID-19 had pre-existing hypertension (n = 68, 2%) and/or diabetes mellitus (n = 49, 1.4%), p = 0.027 [11, 17, 28, 31, 33, 34, 44, 46, 55, 57, 58, 61, 62, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77, 79, 80, 83, 85].

Patient treatment outcome and predictors of mortality

Patients were stratified based on treatment outcome (mortality or survival). A summary of the demographic, source of SARS-CoV-2 infection, CRC staging, treatment received, symptoms of tumor, comorbidities and medical complications with regards to final treatment outcome in 2787 patients who had either survived (n = 2056) or died (n = 731) is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic data of the SARS-CoV-2 patients with colorectal cancer, stratified by treatment outcome (n = 69 studies), 2020–2021

| Variable | Findingsb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 3362) | Survived (n = 2056) | Died (n = 731) | p-valuec | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 60 | 126 (3.7) | 1990 (86.8) | 5 (0.7) | 0.000* |

| ≥ 60 | 1126 (33.5) | 106 (5.1) | 664 (90.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 236 (7.0) | 151 (7.3) | 17 (2.3) | 0.000* |

| Male | 2243 (66.7) | 58 (2.8) | 50 (6.8) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White (Caucasian) | 262 (7.8) | 185 (9) | 20 (2.7) | 0.011* |

| Hispanic | 156 (4.6) | 69 (3.3) | 31 (4.2) | |

| Asian | 153 (4.5) | 117 (5.7) | 37 (5.1) | |

| Persian | 72 (2.1) | 71 (3.4) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Indian | 65 (1.9) | 12 (0.6) | 0 | |

| Blacka | 4 (0.12) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Arab | 2 (0.06) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Source of SARS-CoV-2 infection | ||||

| Community-acquired | 2882 (85.7) | 1932 (94) | 647 (88.5) | 0.014* |

| Hospital-acquired | 480 (14.3) | 124 (6) | 84 (11.5) | |

| Colorectal cancer staging | ||||

| Stage I | 524 (15.6) | 134 (6.5) | 4 (0.5) | 0.036* |

| Stage II | 507 (15.1) | 51 (2.5) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Stage III | 725 (21.6) | 66 (3.2) | 17 (2.3) | |

| Stage IV | 227 (6.7) | 39 (1.9) | 61 (8.3) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgical resections | 304 (9.0) | 53 (2.6) | 21 (2.9) | 0.008* |

| Chemotherapies | 187 (5.6) | 111 (5.4) | 39 (5.3) | |

| Antibiotics | 53 (1.6) | 46 (2.2) | 7 (0.9) | |

| Antivirals | 49 (1.4) | 54 (2.6) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Colectomies | 46 (1.4) | 12 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 43 (1.3) | 26 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Steroids | 29 (0.9) | 21 (1) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Surgeries (nonspecific) | 24 (0.7) | 19 (0.9) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Conservative (no treatment) | 22 (0.6) | 19 (0.9) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Targeted therapies | 20 (0.6) | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Immunotherapies | 17 (0.5) | 8 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Radiotherapy | 12 (0.3) | 10 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Stoma creation | 10 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Immunoglobulin G | 10 (0.3) | 8 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Hartmann’s procedure | 9 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Sigmoidectomies | 8 (0.2) | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 6 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Palliative treatment | 5 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Ileostomy | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Colostomy | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Hormones | 3 (0.1) | – | – | |

| Stoma closure | 2 (0.06) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Stents | 2 (0.06) | – | – | |

| Anastomosis | 2 (0.06) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Antifungals | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Tranexamic acid | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Interferon beta-1b | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Colonic decompression | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Symptoms from the tumor | ||||

| Change in bowel habits | 26 (0.8) | 10 (0.5) | 7 (0.9) | 0.048* |

| Diarrhoea | 25 (0.7) | 18 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (0.7) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 21 (0.6) | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Anaemia (unexplained iron deficiency) | 8 (0.2) | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Haematochezia (blood per anus) | 6 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Weight loss | 5 (0.05) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Blood per rectum | 4 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Melena (black tarry stools) | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Constipation | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 68 (2) | 51 (2.5) | 14 (1.9) | 0.027* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49 (1.4) | 25 (1.2) | 19 (2.6) | |

| COPD | 11 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 11 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Chronic renal failure | 3 (0.09) | – | 2 (0.3) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (0.09) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Morbid obesity | 3 (0.09) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Heart failure | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Acute ischemic stroke | 2 (0.06) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Hepatitis B virus | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Hepatitis C virus | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Lynch Syndrome | 2 (0.06) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (0.06) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | |

| Asthma | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Chronic anaemia | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | 0 | |

| Tuberculosis | 1 (0.03) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | |

| Complications and treatment outcomes | ||||

| Patient was admitted to ICU | 153 (4.5) | 7 (0.3) | 96 (13.1) | 0.000* |

| Patient was intubated and on mechanical ventilation during the ICU stay | 51 (1.5) | 3 (0.1) | 47 (6.4) | 0.000* |

| Patient experienced acute respiratory distress syndrome | 36 (1.1) | 1 (0.05) | 29 (4) | 0.000* |

COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU Intensive care unit, SARS-CoV-2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

aPatients with black ethnicity include African-American, Black African, African and Afro-Caribbean patients

bData are presented as number (%)

cChi-square (χ2) test was used to compare between survival and death groups

Percentages do not total 100% owing to missing data

* Represents significant differences

Those patients who died were more likely to have been older in age (≥ 60 years old: 90.8% vs 0.7%; p = 0.000); and more likely to be men [male gender: 6.8% vs 2.3%; p = 0.000]. Majority of patients who died had an Asian (n = 37, 5.1%) and Hispanic ethnicity (n = 31, 4.2%; p = 0.011). CRC patients who transmitted SARS-CoV-2 from the community had a higher mortality compared to those patients who acquired the SARS-CoV-2 infection from a hospital source (88.5% vs 11.5%; p = 0.014). As expected with the CRC stating, patients with advanced stage had a high mortality [death in stage IV CRC patients occurred in n = 61 (8.3%), p = 0.036]. CRC patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who received chemotherapy had about two-fold increased risk of mortality compared to CRC patients with SARS-CoV-2 who had surgical resections (39 (5.3%) vs 21 (2.9%); p = 0.008). The most common tumor symptoms in CRC patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in whom mortality was reported were the change in bowel habits (n = 7, 0.9%) and diarrhoea (n = 5, 0.7%); p = 0.048. Patients with a pre-existing diabetes mellitus (n = 19, 2.6%) and hypertension (n = 14, 1.9%) had the highest mortality rate compared to other comorbidities; p = 0.027. Mortality rate was significantly very high in CRC patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who were admitted to the intensive care unit (0.3% vs 13.1%; p = 0.000), placed on mechanical ventilation (0.1% vs 6.4%; p = 0.000) and/or suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome (0.05% vs 4%; p = 0.000).

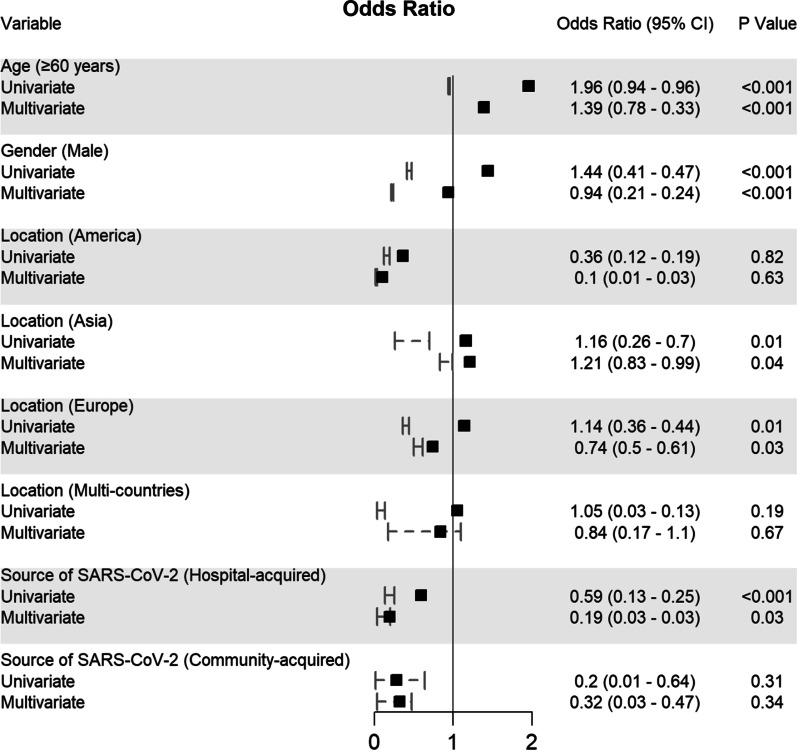

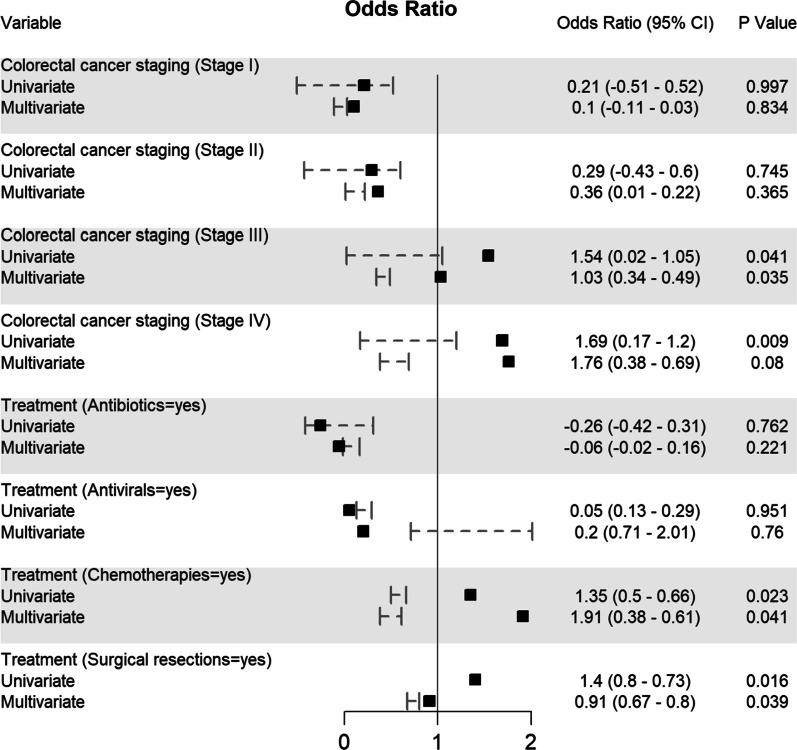

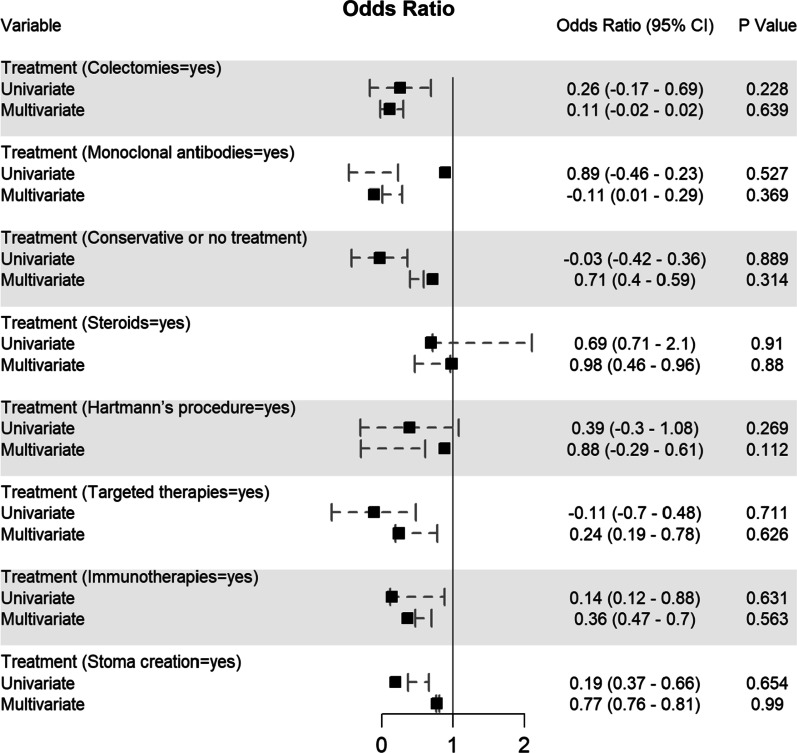

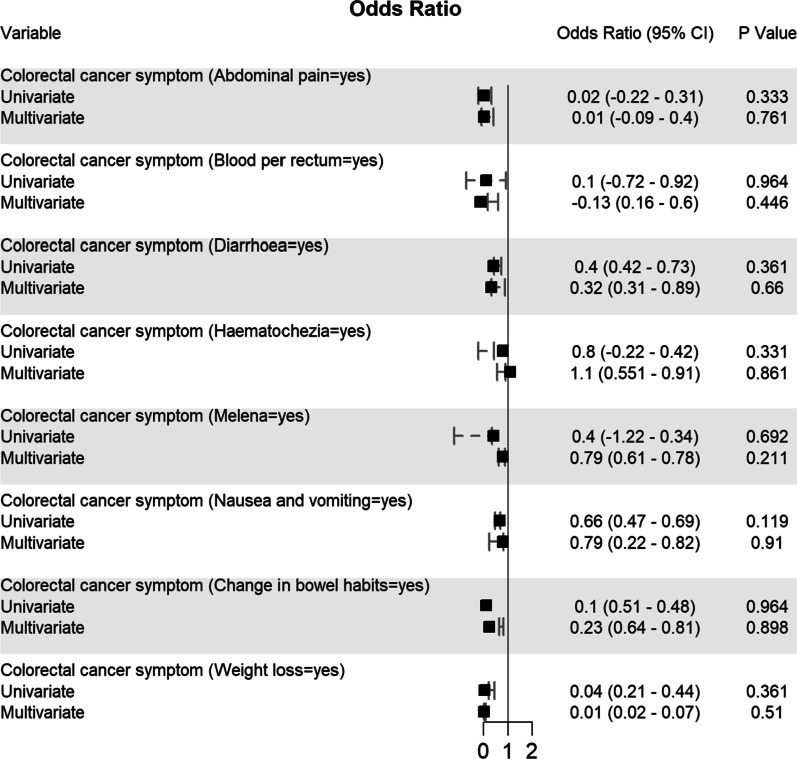

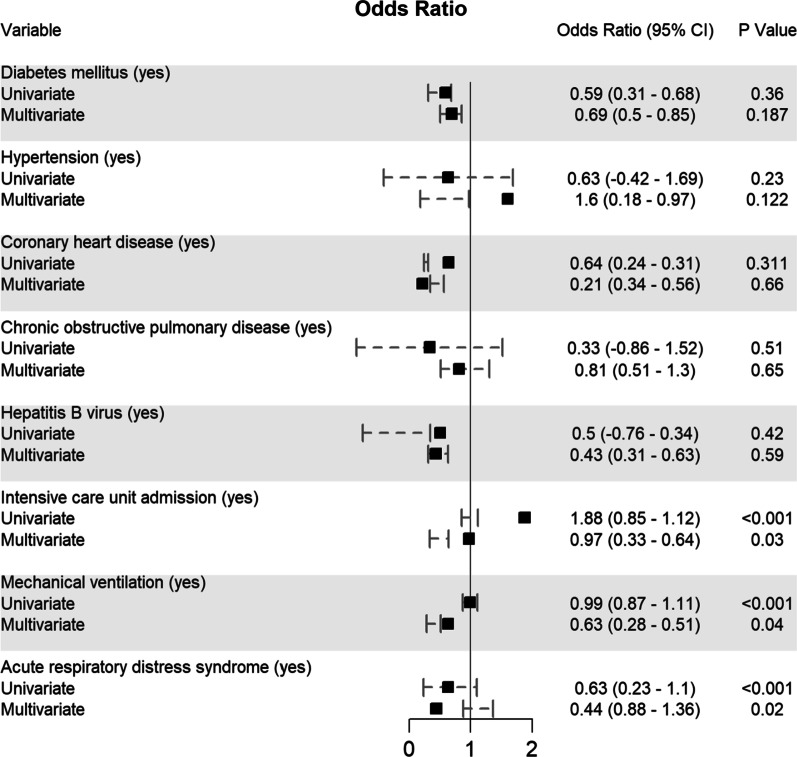

Potential determining variables associated in survival and death groups were analysed through binary logistic regression analysis and shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8 and Fig. 9. As expected, old age (≥ 60 years) (OR 1.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.96; p < 0.001), male gender (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.41–0.47; p < 0.001), CRC patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who came from Asia (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.26–0.7; p = 0.01) and Europe (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.36–0.44; p = 0.01), or transmitted the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection from a hospital source (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.13–0.25; p < 0.001) are associated with increased odd ratio for death; Fig. 5. Among the CRC staging groups, patients who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and presented with CRC stage III (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.02–1.05; p = 0.041) and stage IV (OR 1.69, 95% CI 0.17–1.2; p = 0.009) had a high OR of death; Fig. 6. The odd ratios of death were also high in CRC patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who had chemotherapy (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.5–0.66; p = 0.023) and surgical resections (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.8–0.73; p = 0.016); Fig. 6. Other predictors for increased risk of succumbing included admission to intensive care unit (OR 1.88, 95% CI 0.85–1.12; p < 0.001), intubation and placing on mechanical ventilation (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87–1.11; p < 0.001), and suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.23–1.1; p < 0.001); Fig. 9.

Fig. 5.

Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2768)

Fig. 6.

Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2768)

Fig. 7.

Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2768)

Fig. 8.

Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2768)

Fig. 9.

Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for colorectal cancer and SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2768)

These variables were considered needing further evaluation and, thus, were included in multivariate regression analysis. Nevertheless, multivariate analysis confirmed old age (≥ 60 years), male gender, CRC patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection located in Asia and Europe, who transmitted SARS-CoV-2 from hospital, CRC stage III, who had chemotherapy and surgical resections, admitted to intensive care unit, intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation and suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome were significantly associated with increased death. Although univariate analysis showed CRC stage IV patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection was significantly associated with increased mortality (p = 0.009), however, this finding was not reciprocated by multivariate analysis; Fig. 5.

Discussion

In this large systematic review and meta-analysis, we included 3362 patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from 69 observational studies in order to estimate the prevalence of COVID-19 disease in CRC patients. A better understanding of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 disease in CRC patients allows the development of more specific and more efficient ways of prevention and therapy. As expected, overall prevalence of community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients was fivefold higher compared to hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection in this group of cancer patients (8.1% vs 1.5%). This could be chiefly explained by the maintenance of good knowledge and compliance of infection prevention and control by healthcare providers [87], antimicrobial stewardship [88], and robust surveillance for hospital-acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance [89] within healthcare organizations that provide healthcare for CRC patients. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection acquired from the community in CRC patients was almost similar in Asia (9.1%, 95% CI 6.1–12.2), Europe (7.7%, 95% CI 3.9–11.4), and America (7.0%, 95% CI 3.2–10.7). However, SARS-CoV-2 infection rate acquired from the hospital in CRC patients was the highest in studies conducted in multiple countries (4.7%, 95% CI 3.6–5.9). In general, there is an approximately ninefold variation in CRC prevalence rates by world regions, with the highest rates in European regions, Australia/New Zealand, and Northern America; and rates of CRC prevalence tend to be low in most regions of Africa and in South Central Asia [90]. However, negative impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on CRC patients should be considered as the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sustained reduction in the number of people referred, diagnosed, and treated for CRC [22, 91–93]. The findings in this meta-analysis showed different results from previous systematic meta-analyses that evaluated SARS-CoV-2 infection among CRC patients [24, 94]. We reported a much lower prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients [3.43%] compared to the previous two systematic meta-analyses [45.1% and 20.5%, respectively] [24, 94]. The current meta-analysis is more comprehensive and included a total of 69 studies [8–17, 23, 25–36, 43–85] including a total of 3362 patients; whose details on final treatment outcome were available; in comparison to smaller sample size in previous meta-analyses (sample size: n = 92 and n = 20, respectively) [24, 94]. The inclusion of 65 recently published studies [8–10, 12–17, 23, 25–36, 38, 43, 44, 46–56, 58–84] contributed to the refinement on evidence of the demographic and clinical characteristics; in addition to final treatment outcome in CRC patients with SARS-CoV-2 illness.

We report no paediatric case with SARS-CoV-2 infection and CRC as the incidence of CRC is rare compared with that in adults (prevalence of CRC in patients under age 20 was reported to be 0.2%) [95]. Unlike in adults, familial cancer history is not strongly associated with CRC in children [96]. The lack of childhood cases with COVID-19 and CRC in our review can also be justified by the fact that most children with SARS-CoV-2 disease have mild symptoms or have no symptoms at all [97] and the high severity of COVID-19 tends to be much lower in children compared to adults [98]. However, CRC is more likely to be lethal in children and young adults than middle-aged adults and was explained by the higher incidence of precancerous diseases (such as polyposis, colitis) and mucinous adenocarcinoma and/or late CRC diagnosis in children [95, 96]. Hence CRC is usually diagnosed later and potentially associated with worst prognosis in young groups [95, 96], detecting CRC at an early, more treatable stage is important for cure and survival.

In our review, males gender predominated development of SARS-CoV-2 illness in CRC patients, a finding suggested in most of the reports [9, 11, 14, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32–35, 47, 52–59, 61, 62, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77, 81–85] and in contradiction with data from other reports suggesting an equal proportion of COVID-19 cases in CRC patients for both genders [14, 23, 29, 31, 60, 80] or patients with CRC and SARS-CoV-2 illness were mostly females [11, 36, 46, 49, 50, 66, 67, 76]. This review reflects previous studies in showing that the overall incidence of CRC is higher in males than in females [99–101]. This increased vulnerability of men to developing CRC may be due to a number of biological and gender-related (behavioural) factors [99, 102–104]. Men are more likely to have a diet high in red and processed meat [105], be heavier consumers of alcohol [106], and more likely to smoke [107]. Men also have a greater propensity to deposit visceral fat [108, 109] which is associated with increased risk of CRC [99–101, 110]. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 has been known to infect cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors for entry which have been found to be highly expressed in human males and the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor gene is X-linked [111, 112]. However, male excess in CRC in our review might be attributed mainly to the differences in the inclusion criteria and the population age groups included in the studies; or can be explained by higher rates of comorbidities among men [113, 114], higher trend among females to follow hand hygiene and preventive care [115, 116], stronger immune response to infections in females who outlive men [117] or lower rates of healthcare service utilization by males [118].

We found development of COVID-19 in CRC patients was highest in people of White (Caucasian) [14, 35, 43, 44, 47, 53, 76, 77], Hispanic [13, 70, 72, 80] and Asian ethnicity [11, 15–17, 28, 57, 58, 83] (7.8%, 4.6% and 4.5%, respectively). Moreover, we found mortality rate in CRC patients infected with COVID-19 was significantly high in patients with Asian and Hispanic ethnicity [5.1% and 4.2%, p = 0.011]. CRC is a substantial public health burden and it is increasingly affecting populations in Asian and Hispanic countries [119, 120]. The risk of contracting COVID-19 in people with Asian and Hispanic ethnicity is known to be high and clinical prognosis in those people has been previously described to be poor [121, 122]. CRC screening has been playing an important role in reducing its disease burden [123]. The surveillance system in countries with high burden needed to provide facilities for CRC screening and public awareness education program should be considered in national and international planes to increases the self-participation of people [124]. Financial limitation and lack of authorities are still the main obstacles in the way of CRC screening in most Asian and Hispanic countries with low-income status [125, 126]. Because most of the studies included in our review that reported the ethnicity of CRC cases infected with COVID-19 were either from China, Italy, United States of America, or United Kingdom; representation of other ethnicities at risk to develop COVID-19 in CRC patients can be misleading. For instance, we report a very low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CRC patients in Black population (n = 4, 0.12%), yet, in the United States, the incidence and mortality rates for CRC are higher among Black patients, particularly men, than among those in other racial or ethnic groups, and, among Black patients, CRC occurs at a higher rate below age 50 years [127].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing age in combination with male gender might denote seriously sick patients who can potentially have more morbidity and propensity to die [128, 129]. The majority of CRC patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 are older and seemed to have underlying medical conditions [11, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 47, 57, 59, 60, 62, 72, 77, 85], with increased age being associated with clinical severity, including case fatality. Furthermore, comorbidities [11, 16, 17, 27, 28, 31, 33, 46, 57, 58, 62, 72, 77, 83, 85] and advanced CRC stages (stage III and IV) [26, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 36, 46–49, 60, 72, 77] affect the prognosis of COVID-19. Although chemotherapies and surgical resections are the primary treatment modalities for early stage CRC (stage I through III) [130, 131], we report active treatment of both chemotherapies and surgical resections were associated with an increased risk for severe disease and death from COVID-19 in CRC patients, a finding which is in line with previous meta-analyses [132, 133]. Although one meta-analysis found chemotherapy was associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19 in patients with cancer but failed to show any significant association between other treatments like surgery due to the very small number of included studies [132], our meta-analysis shown the possible increase in risks of severe COVID-19 and death in SARS-CoV-2-infected CRC patients receiving surgical resections which is in consistent with recent cohort and meta-analysis studies [133–135]. Chemotherapies commonly used to treat cancer, including CRC, affect not only the tumor but also the immune system [136]. Advanced COVID-19 syndrome is characterized by the uncontrolled and elevated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and suppressed immunity, leading to the cytokine storm [137]. An impaired immune system might cause a decreased inflammatory response against SARS-CoV-2 and, thus, protecting from cytokine storm [138]. The uncontrolled and dysregulated secretion of inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines in SARS-CoV-2 patients with CRC is positively associated with the severity of the viral infection and mortality rate and this cascade of events may lead to multiple organ failure, ARDS, or pneumonia and need for ICU admission and mechanical ventilation [137, 139]. Furthermore, postoperative pulmonary complications was reported to occur in half of patients with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection and are associated with high mortality [135], therefore, consideration should be given for postponing non-critical procedures and promoting nonoperative treatment in CRC patients to delay or avoid the need for surgery [140]. When hospitals recommence routine surgical treatments, this will be in hospital environments that remain exposed to SARS-CoV-2, so strategies should be developed to reduce in-hospital SARS-CoV-2 transmission and mitigate the risk of postoperative complications in CRC patients [135].

Limitations

First, while most of the evidence discussed were based on many cohorts, case reports, case-series and few cross-sectional and case–control studies, many of these are small and not necessarily generalizable to the current COVID-19 clinical environment in patients with CRC history. Second, to asses factors associated with mortality, larger cohort of patients is needed. Last, almost all studies included in this review were retrospective in design which could have introduced potential reporting bias due to reliance on clinical case records.

Conclusion

Patients with CRC are at increased risk of severe complications from SARS-CoV-2 which may include ARDS, or pneumonia and need for ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. Key determinants that lead to increased mortality in CRC patients infected with COVID-19 include older age (≥ 60 years old); male gender; Asian and Hispanic ethnicity; if SARS-CoV-2 was acquired from hospital source; advanced CRC (stage III and IV); if patient received chemotherapies or surgical treatment; and if patient was admitted to ICU, ventilated or experienced ARDS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank authors and their colleagues who contributed to the availability of evidence needed to compile this article. We would also like to thank the reviewers for very helpful and valuable comments and suggestions for improving the paper. We would like to thank Murtadha Alsuliman who created the cartoon.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19:

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CRC:

Colorectal cancer

- ICU:

Intensive care unit

- NOS:

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- PRISMA:

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- SARS-CoV-2:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Author contributions

SA, A A M, JS. B, N Al D, and AAl-O contributed equally to the systematic review. S A, A Al M, J S. B, and A A. R were the core team leading the systematic review. S A, A Al M, J S. B, N Al D, I A, and A A identified and selected the studies. H I. Al H, N A. Al A, H A. Al A, H A. A, S A A, and R M A did the quality assessment of the studies. S A, S A. B, A B, N A. A, W A, M Y A, A U. A, H A. Al, M M. A, A N. B, M A, M A. A, T K, J A. Al-T, and K D collected the data. S A, K M. Al m, A H. A, A M T, H A. A, and F M. AL analyzed the data. S A, A Al M, J S. B, N Al D, S A. B, Ali A. R, and A Al-O drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article except for the datasets generated and analysed to explore the effect of various demographic parameters and clinical variables on patient’s final treatment outcome. These datasets are not publicly available due privacy concern but will be available, please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This review is exempt from ethics approval because we collected and synthesized data from previous clinical studies in which informed consent has already been obtained by the investigators.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saad Alhumaid, Email: saalhumaid@moh.gov.sa.

Abbas Al Mutair, Email: abbas4080@hotmail.com.

Jawad S. Busubaih, Email: jawadsalman@hotmail.com

Nourah Al Dossary, Email: nofaldossary@moh.gov.sa.

Murtadha Alsuliman, Email: moalsalman@moh.gov.sa.

Sarah A. Baltyour, Email: sbaltyour@moh.gov.sa

Ibrahim Alissa, Email: ibalissa@moh.gov.sa.

Hassan I. Al Hassar, Email: hhassar@moh.gov.sa

Noor A. Al Aithan, Email: nalaithan@moh.gov.sa

Hani A. Albassri, Email: halbasri@moh.gov.sa

Suliman A. AlOmran, Email: suaalomran@moh.gov.sa

Raed M. ALGhazal, Email: dr-raed1@hotmail.com

Ahmed Busbaih, Email: busbaih@gmail.com.

Nasser A. Alsalem, Email: salemna_2000@yahoo.com

Waseem Alagnam, Email: agnamws@gmail.com.

Mohammed Y. Alyousef, Email: moyalyousef@moh.gov.sa

Abdulaziz U. Alseffay, Email: research.center@almoosahospital.com.sa

Hussain A. Al Aish, Email: halaish@moh.gov.sa

Ali Aldiaram, Email: aaldiaram@moh.gov.sa.

Hisham A. Al eissa, Email: haaleissa@moh.gov.sa

Murtadha A. Alhumaid, Email: mualhumaid@moh.gov.sa

Ali N. Bukhamseen, Email: abokhamsin@moh.gov.sa

Koblan M. Al mutared, Email: kmot@moh.gov.sa

Abdullah H. Aljwisim, Email: aaljwisim@moh.gov.sa

Abdullah M. Twibah, Email: atwibah@moh.gov.sa

Meteab M. AlSaeed, Email: mmalsaeed@moh.gov.sa

Hussien A. Alkhalaf, Email: hualkhalaf@moh.gov.sa

Fatemah M. ALShakhs, Email: falshakhs@moh.gov.sa

Thoyaja Koritala, Email: koritala.thoyaja@mayo.edu.

Jaffar A. Al-Tawfiq, Email: jaffar.tawfiq@jhah.com

Kuldeep Dhama, Email: kdhama@rediffmail.com.

Ali A. Rabaan, Email: arabaan@gmail.com

Awad Al-Omari, Email: awad.omari@drsulaimanalhabib.coms.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard 2022 [21 July 2022]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 2.Centers for disease control and prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by age group 2022 [21 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html.

- 3.Centers for disease control and prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with high risk for severe COVID-19: Information for healthcare providers 2022 [21 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html. [PubMed]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science brief: Evidence used to update the list of underlying medical conditions that increase a person's risk of severe illness from COVID-19 2022 [21 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/underlying-evidence-table.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Fclinical-care%2Funderlying-evidence-table.html. [PubMed]

- 5.Sorensen RJ, Barber RM, Pigott DM, Carter A, Spencer CN, Ostroff SM, Reiner RC, Jr, Abbafati C, Adolph C, Allorant A. Variation in the COVID-19 infection-fatality ratio by age, time, and geography during the pre-vaccine era: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1469–1488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02867-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]