Abstract

The cholate-resistant Lactococcus lactis strain C41-2, derived from wild-type L. lactis MG1363 through selection for growth on cholate-containing medium, displayed a reduced accumulation of cholate due to an enhanced active efflux. However, L. lactis C41-2 was not cross resistant to deoxycholate or cationic drugs, such as ethidium and rhodamine 6G, which are typical substrates of the multidrug transporters LmrP and LmrA in L. lactis MG1363. The cholate efflux activity in L. lactis C41-2 was not affected by the presence of valinomycin plus nigericin, which dissipated the proton motive force. In contrast, cholate efflux in L. lactis C41-2 was inhibited by ortho-vanadate, an inhibitor of P-type ATPases and ATP-binding cassette transporters. Besides ATP-dependent drug extrusion by LmrA, two other ATP-dependent efflux activities have previously been detected in L. lactis, one for the artificial pH probe 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) and the other for the artificial pH probe N-(fluorescein thio-ureanyl)-glutamate (FTUG). Surprisingly, the efflux rate of BCECF, but not that of FTUG, was significantly enhanced in L. lactis C41-2. Further experiments with L. lactis C41-2 cells and inside out membrane vesicles revealed that cholate and BCECF inhibit the transport of each other. These data demonstrate the role of an ATP-dependent multispecific organic anion transporter in cholate resistance in L. lactis.

Primary bile salts, such as glyco- and taurocholate and glyco- and taurochenodeoxycholate, are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver. The steroid nucleus is conjugated with an amide bond at the carboxyl C-24 position to one of two amino acids, glycine or taurine. Following synthesis, the bile salts are secreted into bile and enter the lumen of the small intestine, where they facilitate absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, lipids, and cholesterol. Most of these bile salts are absorbed from the small intestine, returned to the liver via the portal circulation, and resecreted into bile (13, 25). The remaining part of the bile salts is deconjugated by the action of bile salt hydrolases present in intestinal bacteria, with the formation of the corresponding free bile acids, such as cholate and chenodeoxycholate (6). The free bile acids are further metabolized by some members of the intestinal bacteria into secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholate and lithocholate (8).

Free bile acids are obviously toxic for living cells because they have the ability to disaggregate the ordered structure of biological membranes. With bile salts and free bile acids flowing in large amounts through the digestive tract, the bacterial members of the gastrointestinal microflora must have evolved the ability to survive under these toxic conditions. Although evidence has been obtained for the presence of proton motive force-dependent bile salt transporters in gram-negative bacteria (11, 18, 20, 34), these systems have not yet been studied in detail in gram-positive bacteria. In this paper, the gram-positive bacterium Lactococcus lactis MG1363 was used as a model organism. The sensitivity of this strain to millimolar concentrations of cholate allowed the selection of a cholate-resistant L. lactis strain, C41-2. The cholate resistance mechanism in L. lactis C41-2 was investigated. Cholate transport studies in cells and inside out membrane vesicles revealed the presence of an ATP-dependent cholate extrusion system. To our knowledge, this is the first paper describing the presence of this type of system in bacteria. Interestingly, the cholate transporter in L. lactis C41-2 showed specificity for the anionic pH indicator 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) and hence may be functionally related to members of the mammalian multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) subfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins and other eukaryotic ABC transporters, such as yeast Pdr12, with specificity for structurally unrelated organic anions, including weak acids and carboxyfluorescein derivatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

M17 broth was obtained from Difco. Sodium taurocholate, sodium cholate, potassium cholate, and sodium deoxycholate were purchased from Sigma. [carboxyl-14C] cholic acid (50 mCi/mmol) was from New England Nuclear Corp. 2′,7′-Bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF), BCECF acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM), 5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), 5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFDASE), and fluorescein isothiocyanate were purchased from Molecular Probes.

Bacterial strains and cultures.

L. lactis MG1363 was grown at 30°C in M17 medium containing 17 g of M17 broth/liter, 5 g of glucose/liter unless otherwise indicated, and 15 g of agar/liter when appropriate. Cholate-resistant strains of L. lactis were isolated by selecting for growth in M17 medium containing stepwise-increasing sodium cholate concentrations up to 14 mM. Subsequently, cholate-resistant cells were plated on M17 agar without cholate to enable the isolation of single colonies. Pure cultures of the cholate-resistant strains of L. lactis in M17 medium were supplemented with glycerol at a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol) and stored at −80°C.

Cell cytotoxicity assays.

To test the sensitivity of cells to bile acid or salt, precultures of wild-type L. lactis and the cholate-resistant L. lactis C41-2 were diluted 200-fold in M17 medium containing various concentrations of sodium cholate, sodium taurocholate, or sodium deoxycholate. The growth of the cells was compared by monitoring the optical density at 660 nm (OD660) after 6 h of incubation. During this incubation period, wild-type cells had reached the end of the exponential growth phase in cultures without added bile acid or salt. From the data, the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of bile acid or salt, which reduced the growth of cells by 50%, were determined. The cell cytotoxicities of ethidium bromide and rhodamine 6G were determined in 96-well plates as described previously (1). Here, the IC50 was determined to be the drug concentration which resulted in a 50% reduction of the growth rate relative to that observed in the absence of drug.

Cholate transport.

To preload cells with [14C]cholate, exponentially growing L. lactis cells were harvested, washed once with 50 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM MgSO4, and resuspended in this buffer to an OD660 of about 20. The cells were deenergized by incubation in the presence of 10 mM 2-deoxyglucose for 30 min at 30°C, washed three times with KPi buffer, and resuspended in this buffer to an OD660 of about 8 (3 mg of protein/ml). Aliquots (96 μl) of the cell suspension were dispensed in glass tubes, and glucose was added as a source of metabolic energy at a final concentration of 10 mM. After a preincubation for 5 min at 30°C, 2 μl of 5.8 mM [14C]cholate (16 mCi/mmol) was added (final cholate concentration, 0.116 mM at time zero), and the cell suspensions were incubated for another 35 min. After the glucose was depleted, at approximately 15 min from time zero, the cells rapidly accumulated cholate. The steady-state level of cholate accumulation in glucose-depleted cells which was obtained by this procedure was 1.3 nmol/mg of protein for both L. lactis C41-2 and L. lactis MG1363, with a variance of less than 6% (n = 4).

The energy-dependent extrusion of cholate from preloaded cells was initiated by the addition of glucose to a final concentration of 10 mM. When appropriate, valinomycin and/or nigericin was added to a final concentration of 2 and 1 μM, respectively. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 100 μl. At various time intervals (see Fig. 2, 3, 4, and 7), the amount of [14C]cholate which remained associated with the cells was estimated by the rapid-filtration method. Samples were mixed with 3 ml of ice-cold wash buffer (100 mM KPi [pH 7.0] supplemented with 100 mM LiCl) and filtered over 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose-acetate filters. The filters were washed once again with 3 ml of the wash buffer. Subsequently, the radioactivity retained on the filter was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. The background level of radioactivity obtained for control incubations without cells was subtracted from all readings. An intracellular volume of 3 μl per mg of protein was used to calculate the intracellular cholate concentration (31). To study the effect of ortho-vanadate on cholate transport, cells were grown in M17 medium supplemented with 50 mM galactose plus 50 mM l-arginine, rather than glucose, to induce enzymes of the arginine deiminase pathway. Since ortho-vanadate inhibits glycolysis, metabolic energy for transport was generated through the vanadate-insensitive arginine deiminase pathway (5, 30). The cells were cultured until exponential phase, and the deenergized cell suspension was prepared as described above, using 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 6.5) containing 1 mM MgSO4 instead of the KPi buffer. Phosphate-free buffer was required to avoid competition between ortho-vanadate and inorganic phosphate in the inhibition experiments. Aliquots (95 μl) of the cell suspension were dispensed in glass tubes, and l-arginine was added to a final concentration of 20 mM in the presence or absence of 1 mM ortho-vanadate. After incubation at 30°C for 10 min, when the cells generated metabolic energy and when ortho-vanadate was transported into the cells, valinomycin was added to a final concentration of 2 μM. Subsequently, 2 μl of 5.8 mM [14C]cholate (16 mCi/mmol) was added to start the transport assays. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 100 μl. At appropriate time intervals, cell-associated cholate was measured by the rapid-filtration method as described above.

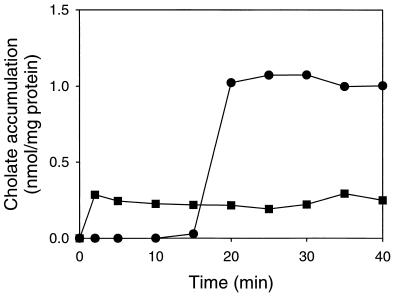

FIG. 2.

Loading of L. lactis C41-2 cells with cholate. Incubations were done in the presence (●) and absence (■) of 10 mM glucose. Cholate was added at time zero to an external concentration of 0.116 mM.

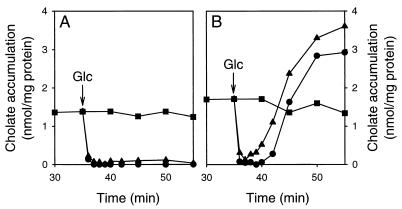

FIG. 3.

Energy-dependent extrusion of cholate in the cholate-resistant L. lactis C41-2 and in wild-type L. lactis MG1363. After the cells were loaded with cholate (■), glucose was added to a final concentration of 10 mM at the time point indicated by the arrow. Subsequently, the amount of cell-associated cholate was measured over time in the absence (●) and presence (▴) of 2 μM valinomycin, which selectively dissipated the transmembrane potential. (A) Strain C41-2; (B) strain MG1363.

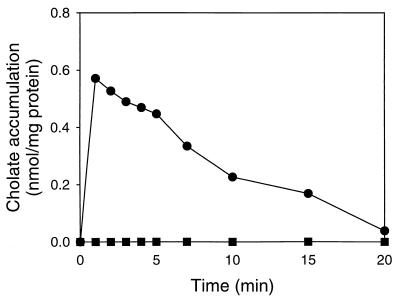

FIG. 4.

Effect of ortho-vanadate on the transport of cholate in L. lactis C41-2. The transport of cholate was measured in the presence (●) and absence (■) of 1 mM ortho-vanadate, using cells which obtained metabolic energy from the catabolism of l-arginine. To maximize the ΔpH-driven accumulation of cholate in the cells, measurements were performed at pH 6.5 in the presence of 2 μM valinomycin.

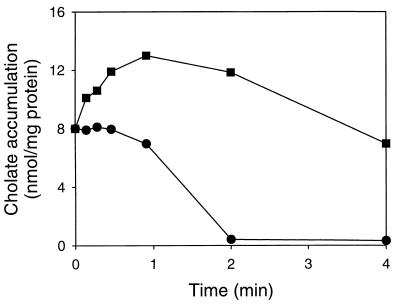

FIG. 7.

Effect of BCECF on the efflux of cholate in L. lactis C41-2. Cells loaded with BCECF (■) or unloaded cells (●) were equilibrated in the presence of 2.7 mM [14C]cholate and 1 μM nigericin. Transport was initiated at time zero by the addition of glucose to a final concentration of 20 mM.

BCECF transport.

Cells of L. lactis were loaded with BCECF using its hydrophobic nonfluorescent acetoxy-methyl ester (BCECF-AM), which is membrane permeable and which is hydrolyzed into hydrophilic fluorescent BCECF in the cytoplasm by nonspecific esterase activity (3). Deenergized cell suspensions with OD660s of about 0.5 received 20 μM BCECF-AM and were incubated for 10 min at 20°C. The internal BCECF concentrations which were reached in cells by this method varied between 10 and 20 mM. After being loaded, the cells were washed four times in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM MgSO4. To initiate BCECF efflux, cell suspensions were prewarmed at 30°C and glucose was added to a final concentration of 20 mM. At various time intervals, the cell suspensions were centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge, and the supernatants were mixed with 10 to 30 volumes of 50 mM bis-tris propane (pH 9.1). BCECF fluorescence was measured with a Perkin-Elmer model LS-50B luminescence spectrometer equipped with a thermostat and magnetically stirred cuvette holder at excitation and emission wavelengths of 502 and 525 nm, respectively, and with slit widths of 4 and 8 nm, respectively. The BCECF fluorescence was compared to that of BCECF standard solutions in the bis-tris propane buffer mentioned above.

The transport of BCECF in inside out membrane vesicles of L. lactis was measured by a rapid-centrifugation technique. Inside out membrane vesicles were prepared using a French pressure cell as described previously (22), resuspended to a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. To measure BCECF transport, the membrane vesicles were diluted to a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, 0.17 mM BCECF, 1 μM valinomycin, 1 μM nigericin, 5 mM phosphocreatine, and 0.1 mg of creatine kinase/ml. Transport was initiated by the addition of 2 mM Mg-ATP. At various time intervals, samples were centrifuged in an airfuge (Beckman) for 5 min at 20 lb/in2. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the membrane vesicle pellet was washed with 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0). The pellet was solubilized in 50 mM bis-tris propane (pH 9.1) supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. The BCECF concentration was measured by fluorimetry as described above, using a BCECF calibration curve prepared in buffer containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100.

FTUG transport.

N-(fluorescein thio-ureanyl)-glutamate (FTUG) was freshly prepared from fluorescein isothiocyanate and potassium glutamate as described previously (10). Cells of L. lactis were loaded with FTUG by lowering the external pH of a cell suspension (OD660, about 0.5) to values between 1 and 3 by the addition of small aliquots of 0.5 M HCl. FTUG was added to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 1 mM. In this way, the negatively charged carboxylic groups were neutralized, allowing the acid form of the probe to enter the cytoplasm. Once inside, the probe was rapidly deprotonated and trapped due to the relatively alkaline internal pH. After an acid shock of 5 min, an excess of 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) was added, and the cells were washed four times in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM MgSO4. The washed cell pellet, which contained a fair amount of FTUG (as judged by the intensity of its color) after treatment with the smallest amount of acid, was used for further experiments. In general, these cells contained between 0.2 and 1.5 mM FTUG. The cell pellets were resuspended in wash buffer and equilibrated at 30°C, and FTUG export was initiated by the addition of glucose to a concentration of 20 mM. FTUG efflux was measured as described for BCECF efflux. FTUG fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 494 and 518 nm, respectively, with slit widths of 4 nm each. FTUG transport in inside out membrane vesicles was measured as described for BCECF transport at an FTUG concentration of 0.5 mM.

Measurement of the proton motive force.

The transmembrane potential (ΔΨ; interior negative) in cells was determined from the distribution of tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+) using a TPP+-selective electrode (32). The standard assay was performed in 1 ml of a suspension of deenergized cells (OD660, about 8) as described for cholate transport in the presence of 4 μM TPP+ at 30°C. The cells were supplied with metabolic energy by the addition of glucose to a concentration of 10 mM. Measurements were corrected for dilution and nonspecific probe binding to the cells (17). The transmembrane pH gradient (ΔpH; interior alkaline) was calculated from the increase in the ΔΨ upon the addition of 1 μM nigericin, assuming a complete interconversion of the ΔpH into the ΔΨ. The ΔpH in cells was also estimated by a direct measurement of the internal pH in L. lactis using the internally conjugated fluorescent pH probe CFSE (4). This probe was accumulated in the cells by the addition of a 4 μM concentration of its membrane-permeable diacetate ester (CFDASE) to a cell suspension with an OD660 of about 0.5 (prepared as described for cholate transport), followed by incubation for 30 min at 30°C. In the cytoplasm of the cells, CFSE was covalently trapped through the conjugation of its succinimidyl group with aliphatic amines. Unconjugated CFSE was effluxed from loaded cells by the addition of glucose to a concentration of 20 mM. Cells containing conjugated CFSE were washed two times in prewarmed 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM MgSO4. The washed cells were resuspended to an OD660 of about 0.5 and dispensed in a cuvette. The cell-associated CFSE fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 490 and 520 nm, respectively, with slit widths of 2.5 nm each. CFSE fluorescence was calibrated in cell suspensions containing 5 μM valinomycin plus 5 μM nigericin (the pH of the cytoplasm [pHin] equals the pH of the external buffer [pHout]) in a pH range of 6 to 8 using a pH microelectrode. The ΔΨ was calculated from the increase in the pHin upon the addition of 1 μM valinomycin, assuming a complete interconversion of the ΔΨ into the ΔpH.

Protein measurements.

Cell suspensions were boiled in 1 N NaOH for 10 min, after which the protein concentrations were measured by the method of Lowry et al. (19). Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard.

RESULTS

Selection of a cholate-resistant strain.

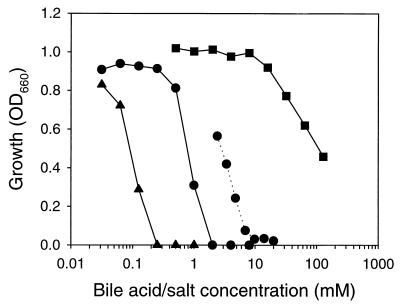

The growth of wild-type L. lactis MG1363 is sensitive to the presence of millimolar concentrations of deoxycholate or cholate but insensitive to the presence of millimolar concentrations of taurocholate (Fig. 1). This degree of sensitivity is consistent with the hydrophobicity of the compounds, which is highest for deoxycholate and lowest for taurocholate, and hence, with the ability of the compounds to diffuse across biological membranes (16). To study the mechanisms of cholate resistance in L. lactis MG1363, cholate-resistant strains were isolated by the sequential transfer of the bacteria in media with increasing concentrations of cholate. One of these strains, L. lactis C41-2, was selected for further study. In the absence of bile salt or acid, the growth rate of L. lactis C41-2 was comparable to that of L. lactis MG1363 (1.27 ± 0.04 versus 1.64 ± 0.08 h−1), and the OD660s of the cultures at the stationary growth phase were close to 1 for both strains (1.05 for strain C41-2 versus 0.95 for strain MG1363). Although the growth level of L. lactis C41-2 decreased with increasing cholate concentrations, this strain survived even in the presence of 20 mM sodium cholate (Fig. 1). The IC50 of cholate for L. lactis C41-2 was 2.5 mM, which was three times the IC50 of 0.8 mM obtained for wild-type cells. In contrast, the IC50 of deoxycholate, 0.09 mM, was comparable to the value of 0.12 mM obtained for wild-type cells. Thus, L. lactis C41-2 displayed an increased resistance to cholate.

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of wild-type L. lactis MG1363 and the cholate-resistant L. lactis C41-2 to cholate, deoxycholate, and taurocholate. Both strains were grown for 6 h in M17 medium containing various concentrations of cholate (●), deoxycholate (▴), and taurocholate (■). The solid lines and the dotted line represent L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis C41-2, respectively.

Passive influx of cholate.

Differences in the magnitudes of the transmembrane proton gradient (−ZΔpH; interior alkaline) in glucose-energized cells of L. lactis MG1363 versus L. lactis C41-2 may explain the differences in the passive influx and accumulation of cholate and hence in cholate resistance. Therefore, the proton motive forces in both strains were measured in the presence of glucose, using a TPP+-selective electrode. The transmembrane potential (ΔΨ; interior negative) of −56 mV and −ZΔpH of −45 mV in L. lactis C41-2 were comparable to the ΔΨ of −59 mV and −ZΔpH of −30 mV in wild-type cells. These data were confirmed in wild-type cells using the internally conjugated fluorescent pH probe CFSE. In this method, the ΔΨ and −ZΔpH in wild-type cells were estimated to be −44 and −32 mV, respectively. Thus, the enhanced cholate resistance of L. lactis C41-2 was not due to a decreased driving force for passive influx and accumulation of cholate in these cells.

Preloading of cells with cholate and active cholate efflux.

To test if active cholate efflux from cells was the basis for the observed cholate resistance in L. lactis C41-2, cells of this strain were preloaded with cholate at an external concentration of 0.116 mM. In the absence of glucose, simple equilibration of cholate between the inside and outside of the cells was obtained (Fig. 2). In the presence of glucose, no uptake of cholate was observed. However, cholate accumulation increased about fourfold in the cells after glucose was depleted, approximately 15 min after the addition of [14C]cholate (Fig. 2). The selective dissipation of the ΔΨ by valinomycin did not significantly affect the accumulation of cholate after the glucose was consumed (data not shown). However, after the depletion of glucose, cholate accumulation above equilibration levels was not observed in the presence of nigericin. Since nigericin selectively dissipates the ΔpH (data not shown), these data are consistent with the notion that cholic acid is a weak acid (pKa, 6.4) which, in its undissociated form, diffuses across the plasma membrane and becomes trapped as cholate in the cytoplasm in a ΔpH-dependent fashion. For L. lactis MG1363, the kinetics of preloading and the steady-state level of cholate accumulation were similar to the data obtained for L. lactis C41-2 (data not shown and Fig. 3). The amount of cell-associated cholate did not change over time in preloaded cells of L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis C41-2 in the absence of glucose (Fig. 2 and 3).

The cholate accumulation levels obtained in glucose-depleted cells of L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis C41-2 were sufficient to study the active efflux of cholate. Upon the addition of glucose to cholate-loaded cells of L. lactis C41-2, a rapid extrusion of cholate was detected (Fig. 3A). Within 2 min after the addition of glucose, cholate was completely effluxed from the cells, after which the amount of cell-associated cholate remained very low for another 15 to 20 min. This efflux pattern was different from that observed for wild-type cells (Fig. 3B). There, the efflux of cholate was immediately followed by the accumulation of cholate up to a steady-state level, at which the internal concentration was sevenfold higher than that of the extracellular medium. The reaccumulation of cholate in wild-type cells appeared to be due to the increase in ΔpH (interior alkaline) under these conditions. Consistent with this notion, the reaccumulation of cholate was significantly enhanced in glucose-energized wild-type cells in which the ΔΨ was interconverted into the ΔpH due to the presence of valinomycin (Fig. 3B). This interconversion process in wild-type cells was confirmed in measurements in which the pH probe CFSE was used to estimate the internal pH (data not shown). Hence, it seems reasonable to consider that the activity of the cholate extrusion system in L. lactis C41-2 was strong enough to overcome the passive ΔpH-dependent cholate influx. On the other hand, the passive ΔpH-dependent influx of cholate in L. lactis MG1363 exceeded the active efflux and resulted in the reaccumulation of cholate. These data led us to conclude that the difference in cholate resistance between the wild-type L. lactis MG1363 and the cholate-resistant L. lactis C41-2 was due to enhanced extrusion of cholate in L. lactis C41-2.

To investigate the driving force for cholate expulsion from L. lactis C41-2, the rate of cholate efflux was measured in the presence of 2 μM valinomycin plus 1 μM nigericin. In a parallel experiment, the complete dissipation of the proton motive force by these amounts of ionophores was confirmed by measurements of the ΔΨ using the TPP+-selective electrode. However, glucose-dependent cholate efflux from preloaded cells was not affected by the presence of the ionophores, suggesting that the proton motive force was not a driving force for cholate extrusion (data not shown). To study the role of phosphate bond energy in ATP as a driving force for cholate efflux, the effect of ortho-vanadate on cholate extrusion was tested (Fig. 4). Vanadate is a well-known inhibitor of ABC transporters and P-type ATPases. When L. lactis C41-2 was energized with l-arginine, a significant accumulation of cholate in the cells was observed in the presence of ortho-vanadate but not in its absence, suggesting that the cholate extrusion system was inhibited by ortho-vanadate. These data suggest that cholate extrusion in L. lactis C41-2 is dependent on the hydrolysis of ATP. With hindsight, we can say that the loading of L. lactis C41-2 with cholate, as depicted in Fig. 2, is only possible after the ATP-dependent cholate efflux activity has been sufficiently reduced due to a lack of ATP production by glycolysis.

Cholate transporter shows specificity for BCECF.

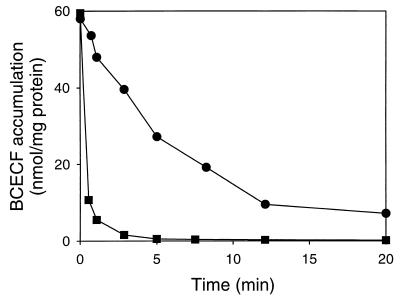

L. lactis contains at least four distinct drug transport activities: the proton motive force-dependent major facilitator superfamily (MFS) multidrug transporter LmrP (2), the ABC multidrug transporter LmrA (35–37), and two ATP-dependent transport activities for the fluorescent pH probes BCECF (24) and FTUG (10). A set of experiments was performed to link the activity of the putative cholate transporter to those of LmrA and LmrP. In liquid cultures, no differences were observed between the resistances of L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis C41-2 to cationic drugs, such as ethidium and rhodamine 6G (with IC50s around 18 and 5 μM, respectively, in both strains), indicating that cholate resistance in L. lactis C41-2 was not mediated by LmrP or LmrA. Experiments were also performed to link the cholate transport activity to the BCECF and FTUG export activities in L. lactis. Cells of L. lactis C41-2 and L. lactis MG1363 were loaded with BCECF at intracellular concentrations between 10 and 20 mM using BCECF-AM. Inside the cells, the acetoxymethyl ester bond of BCECF-AM is hydrolyzed by a nonspecific esterase activity, and membrane-impermeable BCECF remains inside the cells (3). Cells were loaded with FTUG at intracellular concentrations between 0.2 and 1.5 mM by an acid shock in which undissociated FTUG crosses the cytoplasmic membrane by passive diffusion (10). Once inside, the probe is rapidly deprotonated and captured due to the high internal pH. After loading and washing of the cells, BCECF and FTUG effluxes were initiated by the addition of glucose. Although no difference was observed between the rates of FTUG efflux in L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis C41-2 (2.6 versus 3.3 nmol/min · mg), the rate of BCECF efflux in L. lactis C41-2 was at least 10-fold higher (Fig. 5) than that observed in L. lactis MG1363. This surprising result pointed to a possible relationship between cholate efflux and BCECF efflux in L. lactis.

FIG. 5.

BCECF efflux in the wild-type L. lactis MG1363 and in L. lactis C41-2. Cells of L. lactis MG1363 (●) and L. lactis C41-2 (■) were loaded with BCECF. At time zero, BCECF efflux was initiated by the addition of glucose to a final concentration of 20 mM.

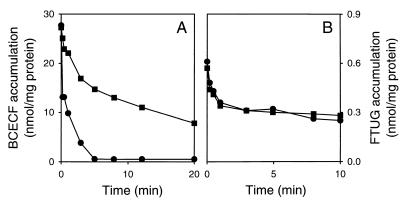

If BCECF and cholate are extruded by the same transporter in L. lactis, the presence of cholate in cells should inhibit the transport of BCECF and vice versa. The effect of cholate on the efflux of BCECF was tested by loading cells of L. lactis C41-2 with an intracellular concentration of 10 mM BCECF (about 30 nmol/mg of protein) and equilibrating the BCECF-loaded cells with 10 mM potassium cholate or 10 mM potassium chloride (control). To exclude indirect effects of cholate on BCECF transport via an alteration of the internal pH, the ΔpH in the cells was dissipated by the presence of 1 μM nigericin (pHin equals pHout). As shown in Fig. 6A, potassium cholate significantly inhibited the transport of BCECF while the presence of potassium chloride did not affect BCECF transport. A study of the dose-response relationship for the inhibition of BCECF transport by cholate revealed an IC50 of about 4 mM cholate (data not shown), which is the same range as the apparent Km of 3 mM BCECF that was determined previously for ATP-dependent BCECF transport in L. lactis (23). Consistent with these data, cholate inhibited the ATP-dependent accumulation of BCECF in inside out membrane vesicles of L. lactis C41-2, in which the proton motive force was dissipated by the presence of valinomycin plus nigericin (data not shown). In experiments with cells and inside out membrane vesicles, these inhibitions were not observed for the transport of FTUG (Fig. 6B and data not shown), pointing to a specific inhibition of BCECF transport by cholate. To investigate the effect of BCECF on the transport of cholate in L. lactis C41-2, cells were loaded with BCECF and equilibrated with [14C]cholate in the presence of nigericin. The addition of glucose to these cells resulted in the active extrusion of cholate from the cells, which was inhibited by the presence of BCECF in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7). Thus, BCECF and cholate inhibit the transport of each other, suggesting that these compounds are effluxed by a common ATP-dependent transport system.

FIG. 6.

Effect of cholate on the efflux of BCECF and FTUG in L. lactis C41-2. Cells were loaded with BCECF (A) or FTUG (B) and equilibrated with 10 mM potassium cholate (■) or 10 mM potassium chloride (●) in the presence of 1 μM nigericin. At time zero, 20 mM glucose was added to the cells to initiate efflux.

DISCUSSION

In this work, the mechanism of cholate resistance was studied in a cholate-resistant L. lactis strain, C41-2, which was derived from wild-type L. lactis MG1363 through selection. Two lines of evidence suggest that ATP-dependent extrusion of cholate is the molecular basis of cholate resistance in L. lactis C41-2: (i) in the presence of metabolic energy, L. lactis C41-2 cells extruded cholate and were able to maintain a substantial inwardly directed cholate concentration gradient, and (ii) the active extrusion of cholate in L. lactis C41-2 cells was insensitive to ionophores that dissipate the proton motive force but was inhibited by ortho-vanadate, a well-known inhibitor of P-type ATPases and ABC transporters.

At present, four different drug efflux systems have been characterized in L. lactis. The ABC multidrug transporter LmrA (35–37) and the MFS multidrug transporter LmrP (2) both export multiple, mostly cationic amphiphilic drugs, such as daunomycin, rhodamine 6G, and ethidium, and are believed to play a role in the extrusion of hydrophobic toxic compounds originating from endogenous metabolism and the natural environment. The ATP-dependent BCECF transporter (24) and FTUG transporter (10) extrude the artificial anionic pH indicators BCECF and FTUG, respectively, but their physiological functions have not been identified because of a lack of insight into their natural substrates. The results obtained with L. lactis C41-2 cells and inside out membrane vesicles derived from them, (i) the enhanced ATP-dependent efflux of both cholate and BCECF, but not of FTUG, and (ii) the competition between cholate and BCECF for transport, leave no doubt that the previously characterized BCECF transporter in L. lactis shows specificity for cholate. Thus, the BCECF transporter most likely functions as a bile acid transporter in L. lactis.

Bile salt or acid transporters have been found in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. In hepatocytes, ABC transporters play an important role in the biliary excretion of bile salts. So far, three different ABC transporter-dependent pathways have been reported. Monovalent bile salts, such as taurocholate and glycocholate, are transported via the canalicular bile salt export pump (9), whereas divalent bile salts, such as taurochenodeoxycholate-3-sulfate and 6-α-glucuronosyl-hyodeoxycholate, are excreted via the canalicular multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) 2 (26, 28). Recently, the basolateral MRP3 protein was shown to transport both monovalent and divalent bile salts (12). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the vacuolar Bat1p is homologous to the MRP subgroup of ABC proteins and is involved in the transport of bile salts (27). ATP-dependent transport of bile salts has also been observed in the vacuoles of plants (15) and in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (33). To date, the known bile salt/acid transporters in prokaryotes are dependent on the proton motive force. In Eubacterium sp., a ΔpH-dependent bile acid-inducible MFS transporter, BaiG, is involved in the import of cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid, which enter the 7α-dehydroxylation pathway (21). Another member of the MFS is involved in the uptake of taurocholate in Lactobacillus johnsonii (7). The accumulated taurocholate is subsequently hydrolyzed by a bile salt hydrolase into taurine and cholate. The bile acid products of the 7α-dehydroxylation pathway in Eubacterium sp. and the bile salt hydrolase pathway in L. johnsonii must be exported from the cell by export systems which have not yet been characterized. Escherichia coli is known to express at least two proton motive force-dependent multidrug efflux systems, the resistance-nodulation-cell-division (RND) family member AcrAB (20) and the MFS protein EmrAB (18), which both play significant roles in bile acid resistance. However, an acrA emrB deletion strain of E. coli still possesses residual chenodeoxycholic acid export activity, suggesting the presence of the third bile acid efflux system in this organism (34). In Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the RND multidrug transporter MtrD plays a significant role in bile acid resistance by mediating the proton motive force-dependent efflux of bile acids (11). To our knowledge, the cholate extrusion system in L. lactis, described in this work, represents the first known ATP-dependent bile acid transporter in prokaryotes. The specificity of this transport protein towards structurally unrelated organic anions, such as cholate and BCECF, points to a functional relatedness to mammalian MRP proteins and the S. cerevisiae ABC transporter Pdr12, which have specificity for organic anions, including weak acids and carboxyfluorescein derivatives (14, 26, 29). Conservation of this activity over a broad evolutionary range suggests that this type of transporter may have a basic metabolic relevance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Monique Putman for skillful experimental assistance and Michael Müller for valuable discussions.

Hendrik W. van Veen thanks the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for awarding a fellowship which enabled him to visit Atsushi Yokota and other prominent scientists in Japan. Atsushi Yokota received a Nuffic scholarship from the Netherlands Organization for International Cooperation in Higher Education. Hendrik W. van Veen is a fellow of the Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolhuis H, Molenaar D, Poelarends G, van Veen H W, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Proton-motive force-driven and ATP-dependent drug extrusion systems in multidrug resistant Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6957–6964. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6957-6964.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolhuis H, van Veen H W, Brands J R, Putman M, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Energetics and mechanism of drug transport mediated by the Lactococcal multidrug transporter LmrP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24123–24128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolhuis H, van Veen H W, Molenaar D, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Multidrug resistance in Lactococcus lactis: evidence for ATP-dependent drug extrusion from the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. EMBO J. 1996;15:4239–4245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breeuwer P, Drocourt J L, Rombouts F M, Abee T. A novel method for continuous determination of the intracellular pH in bacteria with the internally conjugated fluorescent probe 5 (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:178–183. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.178-183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crow V L, Thomas T D. Arginine metabolism in lactic streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:1024–1032. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1024-1032.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doerner K C, Takamine F, LaVoie C P, Mallonee D H, Hylemon P B. Assessment of fecal bacteria with bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating activity for the presence of bai-like genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1185–1188. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1185-1188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkins C A, Savage D C. Identification of genes encoding conjugated bile salt hydrolase and transport in Lactobacillus johnsonii 100-100. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4344–4349. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4344-4349.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklund C V, Baron S F, Hylemon P B. Characterization of the baiH gene encoding a bile acid-inducible NADH:flavin oxidoreductase from Eubacterium sp. strain VPI 12708. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3002–3012. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3002-3012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerloff T, Stieger B, Haugenbuch B, Madon J, Landmann L, Roth J, Hofmann A F, Meier P J. The sister of P-glycoprotein represents the canalicular bile salt export pump of mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10046–10050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaasker E, Konings W N, Poolman B. The application of pH-sensitive fluorescent dyes in lactic acid bacteria reveals distinct extrusion systems for unmodified and conjugated dyes. Mol Membr Biol. 1996;13:173–181. doi: 10.3109/09687689609160594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagman K E, Lucas C E, Balthazar J T, Snyder L, Nilles M, Judd R C, Shafer W M. The MtrD protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a member of the resistance/nodulation/division protein family constituting part of an efflux system. Microbiology. 1997;143:2117–2125. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirohashi T, Suzuki H, Takikawa H, Sugiyama Y. ATP-dependent transport of bile salts by rat multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (Mrp3) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2905–2910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofmann A F. Chemistry and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Hepatology. 1984;4:4S–14S. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holyoak C D, Bracey D, Piper P W, Kuchler K, Coote P J. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae weak-acid-inducible ABC transporter Pdr12 transports fluorescein and preservative anions from the cytosol by an energy-dependent mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4644–4652. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4644-4652.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hortensteiner S, Vogt E, Hagenbuch B, Meier P J, Amrheim N, Martinoia E. Direct energization of bile acid transport into plant vacuoles. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18446–18449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamp F, Hamilton J A. Movement of fatty acid analogues and bile acids across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11074–11086. doi: 10.1021/bi00092a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lolkema J S, Hellingwerf K J, Konings W N. The effect of “probe binding” on the quantitative determination of the proton-motive force in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;681:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomovskaya O, Lewis K. emr, an Escherichia coli locus for multidrug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8938–8942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A J, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma D, Cook D N, Alberti M, Pon N G, Nikaido H, Hearst J E. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallonee D H, Hylemon P B. Sequencing and expression of a gene encoding a bile acid transport from Eubacterium sp. strain VPI 12708. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7053–7058. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7053-7058.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolles M, Putman M, van Veen H W, Konings W N. The purified and functionally reconstituted multidrug transporter LmrA of Lactococcus lactis mediates the transbilayer movement of specific fluorescent phospholipids. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16298–16306. doi: 10.1021/bi990855s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molenaar D, Abee T, Konings W N. Continuous measurement of the cytoplasmic pH in Lactococcus lactis with a fluorescent pH indicator. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1991;1115:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molenaar D, Bolhuis H, Abee T, Poolman B, Konings W N. The Efflux of a fluorescent probe is catalyzed by an ATP-driven extrusion system in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3118–3124. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3118-3124.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller M, Jansen P L M. Molecular aspects of hepatobiliary transport. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1285–G1303. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.6.G1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller M, Meijer C, Zaman G J R, Borst P, Scheper R J, Mulder N H, de Vries E G E, Jansen P L M. Overexpression of the gene encoding the multidrug resistance-associated protein results in increased ATP-dependent glutathione S-conjugate transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:13033–13037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortiz D F, St. Pierre M V, Abdulmessih A, Arias I M. A yeast ATP-binding cassette-type protein mediating ATP-dependent bile acid transport. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15358–15365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulusma C C, Bosma P J, Zaman G J R, Bakker C T M, Otter M, Scheffer G L, Scheper R J, Borst P, Oude Elferink R P J. Congenital jaundice in rats with a mutation in a multidrug resistance-associated protein gene. Science. 1996;271:1126–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piper P, Mahé Y, Thompson S, Pandjaitan R, Holyoak C, Egner R, Mühlbauer M, Coote P, Kuchler K. The Pdr12 ABC transporter is required for the development of weak organic acid resistance in yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:4257–4265. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Regulation of arginine-ornithine exchange and the arginine deiminase pathway in Streptococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2755–2761. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5597-5604.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poolman B, Smid E J, Veldkamp H, Konings W N. Bioenergetic consequences of lactose starvation for continuously cultured Streptococcus cremoris. J Bacteriol. 1986;169:1460–1468. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1460-1468.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinbo T, Kamo N, Kurihara K, Kobatake Y. A PVC-based electrode sensitive to DDA+ as a device for monitoring the membrane potential in biological systems. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;187:414–422. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.St. Pierre M V, Ortiz D F, Arias I M. Yeast as a model for studying transport of bile acids and other organic anions. Hepatology. 1994;20:173A–178A. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanassi D G, Cheng L W, Nikaido H. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2512–2518. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2512-2518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Veen H W, Venema K, Bolhuis H, Oussenko I, Kok J, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Multidrug resistance mediated by a bacterial homolog of the human multidrug transporter MDR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10668–10672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Veen H W, Callaghan R, Soceneantu L, Sardini A, Konings W N, Higgins C F. A bacterial antibiotic-resistant gene that complements the human multidrug-resistance P-glycoprotein gene. Nature (London) 1998;391:291–295. doi: 10.1038/34669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Veen H W, Margolles A, Müller M, Higgins C F, Konings W N. The homodimeric ATP-binding cassette transporter LmrA mediates multidrug transport by an alternating two-site (two-cylinder engine) mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:2503–2514. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]