Abstract

Homelessness and housing instability undermine engagement in medical care, adherence to treatment and health among persons with HIV/AIDS. However, the processes by which unstable and unsafe housing result in adverse health outcomes remain understudied and are the focus of this manuscript. From 2012 to 2014, we conducted qualitative interviews among inpatients with HIV disengaged from outpatient care (n = 120). We analyzed the content of the interviews with participants who reported a single room occupancy (SRO) residence (n = 44), guided by the Health Lifestyle Theory. Although SROs emerged as residences that were unhygienic and conducive to drug use and violence, participants remained in the SRO system for long periods of time. This generated experiences of living instability, insecurity and lack of control that reinforced a set of tendencies (habitus) and behaviors antithetical to adhering to medical care. We called for research and interventions to transform SROs into housing protective of its residents’ health and wellbeing.

Keywords: Housing instability, Single room occupancy (SRO), HIV inpatients, Health habitus, Drug use, Violence

Resumen

La indigencia y la inestabilidad de vivienda reducen la participación en la atención médica, la adherencia al tratamiento y la salud de las personas viviendo con VIH/SIDA. Sin embargo, los procesos mediante los cuales la vivienda inestable e insegura conllevan a resultados adversos de salud permanecen poco estudiados y son el enfoque de este manuscrito. En el 2012–2014, llevamos a cabo entrevistas cualitativas con pacientes hospitalizados con VIH desconectados de servicios de atención ambulatoria (n = 120). Analizamos el contenido de las entrevistas (n = 44) con participantes que residían en un programa de ocupación de habitación individual (SRO, por sus siglas en inglés), guiados por la Teoría del Estilo de Vida Saludable. Aunque el programa de ocupación de habitación individual surgió en las entrevistas como residencias antihigiénicas y propicias para el uso de drogas y la violencia, los participantes se mantuvieron en el programa de ocupación de habitación individual por largo tiempo. Esto generó experiencias de inestabilidad en la vivienda, inseguridad y falta de control que reforzó tendencias (habitus) y comportamientos antitéticos a adherirse a la atención médica. Pedimos investigaciones e intervenciones para transformar los programas de ocupación de habitación individual en viviendas que protejan la salud y el bienestar de sus residentes.

Background

Housing instability and homelessness have been identified as primary structural barriers to receiving consistent medical care, adhering to antiretroviral treatment (ART) and safeguarding one’s health among persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) [1–3]. Numerous studies have substantiated a correlation and few a causal association between housing instability and/or homelessness and non-engagement in HIV care, non-adherence to ART, substance use and non-suppression [1, 4–8]. There is, however, a lack of studies that identify the processes by which different housing statuses and experiences influence health and health behavior among PLWH. Recent systematic literature reviews have called for empirical studies on the pathways and processes that link housing instability, precariousness and literal homelessness to adverse health outcomes among PLWH, directly and indirectly through non-engagement in medical care [1, 9].

To address this literature gap, we must recognize that housing is more than a physical structure that provides shelter. Housing is the place where individuals shape their everyday lives, identities, and relationships [10–12]. Along-side its objective features (e.g., construction quality, location), housing also has subjective meaning that determines whether a person experiences a place as stable, safe, private and comfortable as a home or contrary, as temporary, unsafe, and lacking privacy or comfort, that is, not a home. Moreover, this determination influences a person’s motivation and ability to attend to his or her physical and mental wellbeing [10, 12]. Therefore, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the processes by which housing impacts the health of PLWH, it is crucial to examine the psychological, social and meaningful features of the different types of housing where their lives unfold [1, 9].

The single room occupancy (SRO) housing is a type of living arrangement where residents occupy a single room in a multi-room building and typically share a bathroom, shower and kitchen [13]. SRO housing, at market rate and publicly subsidized, is available in most cities in the US and Canada, including in New York City (NYC). Subsidized SROs often house PLWH and persons with substance use and/or mental health disorders in an attempt to prevent street homelessness. Subsidized motels and hotels are typically included in the same category as SROs. Specifically, in NYC the HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA) housing program relies on SROs, motels and hotels that are operated commercially or by non-profit organizations to provide what the agency calls, “emergency housing” to PLWHA [14]. According to HASA’s guidelines, living in a SRO is supposed to be time limited, as this type of housing is deemed appropriate for “short stays.” However, in NYC similarly to other cities, length of residence in SROs, quality of buildings, management policies, extent of public funding, and provision of on-site supportive services vary extensively. This variation in SRO features largely explains why researchers have classified living in this type of housing as being homeless [15], not homeless [16], unstably housed [17], and marginally housed [18]. This lack of consistency in classifying SROs, motels and hotels is particularly salient because these abodes are used extensively by low-income PLWH. Further, although SROs are supposed to serve as temporary residences prior to transitioning to a more permanent housing situation, there is a lack of research data on whether this outcome is achieved. Despite the widespread use of SROs by PLWH, there is a dearth of research on the association between living in SROs and HIV-related health outcomes and behavior [19]. Indeed, most of the insights on SROs and health are based on studies examining residents with substance use and/or mental health disorders [20–22]. These few SRO-focused studies suggest that overall these abodes afford substandard living conditions, limited safety and stability and increase residents’ sex and drug risk behaviors. SROs seem to emerge as risk instead of protective environments. Given the extensive use of SROs by PLWH and the accompanying potential risks imposed upon its residents, it is imperative to investigate how living in an SRO can contribute to poor health and risky health behavior to develop effective intervention strategies.

The goal of this manuscript is to identify the processes by which housing shapes health behaviors and outcomes. This analysis focuses on the housing experiences of 44 HIV-infected hospitalized patients who were disengaged from outpatient care and who identified SROs and/or hotels as a recent primary residence. This manuscript is based on data from a larger study called, Bedside to Community, or B2C (n = 120). The B2C study aimed to identify the structural- and individual-level barriers to engaging in HIV outpatient care and was guided by Cockerham’s Health Lifestyle Theory [23, 24].

Theoretical Framework

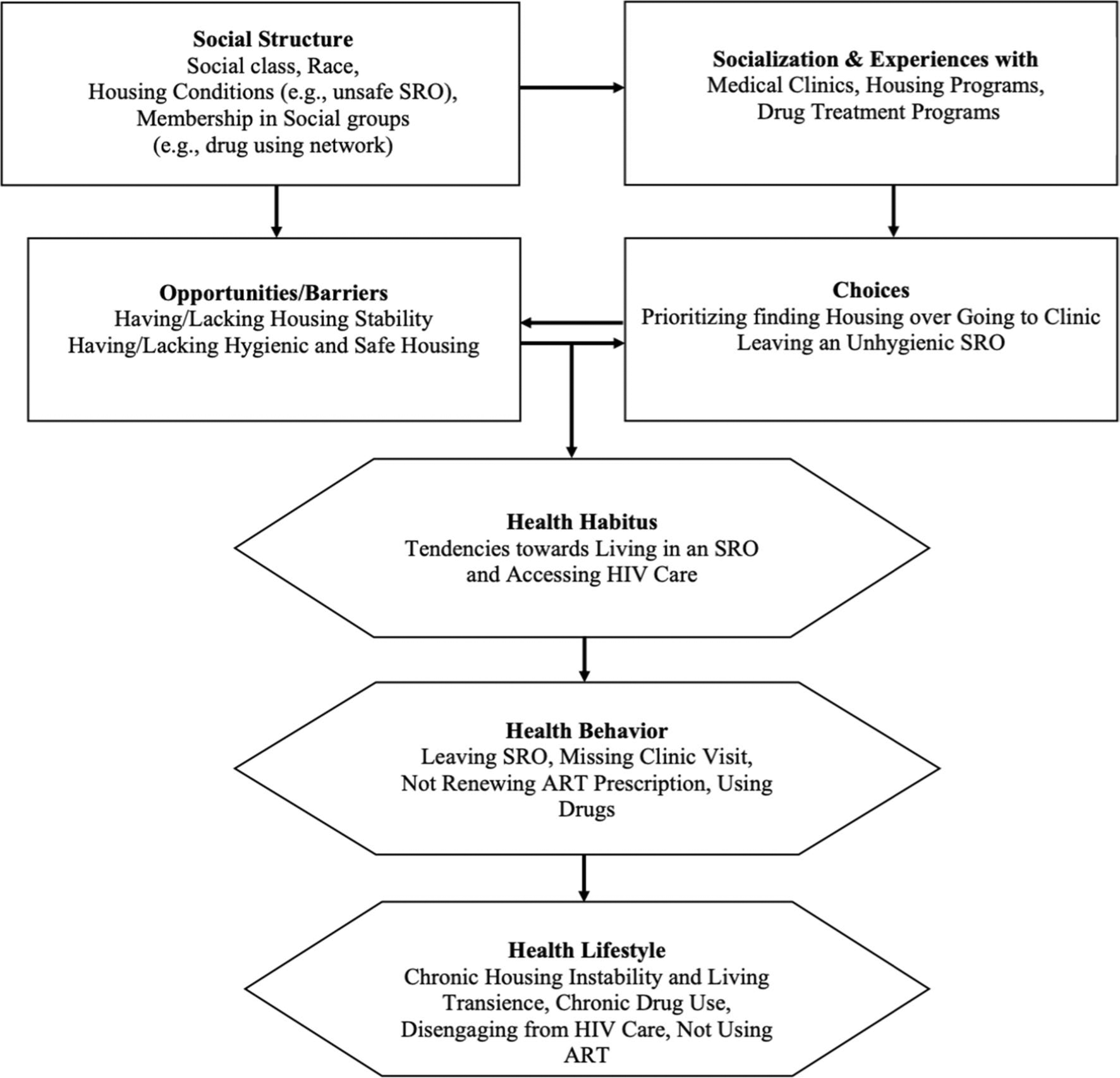

The Health Lifestyle Theory [23, 24] integrates the concept of health habitus to explain the different health behaviors individuals develop that affect their health. Building on Bourdieu’s concept of habitus [25, 26], health habitus refers to the lasting dispositions or tendencies to care for our health in certain ways, including accessing routine medical appointments, or not. These tendencies integrate our perceptions and evaluations of the world, and become a mental map that guides our health-related actions, or behavior. Over time and with repetition of the same health behavior, individuals develop health lifestyles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theory of Health Lifestyle (Based on Cockerham [23])

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, health habitus is shaped by the interplay between the life opportunities or barriers we face in caring for our health and the health-related life choices we make as individuals. Opportunities and barriers (e.g., having or lacking housing stability, having or lacking a hygienic and safe residence) are based on our place in the social structure. Social class, race, housing conditions, and membership in social groups (e.g., network of persons who use substances, HIV support group) are key components of the social structure. Choices (e.g., prioritizing finding housing over attending a medical appointment or leaving an unhygienic SRO residence to live on the street) are based on our early socialization and also our later life experiences, including experiences with institutions and programs (e.g., medical clinics, public assistance agencies, housing programs and drug treatment programs). Socialization and experiences are also shaped by our place in the social structure. For instance, social class and race influence how we are reared and how we interact with institutions such as, school, workplace, public assistance agencies and healthcare places. Therefore, health habitus (i.e., our tendencies to care for our health in certain ways) includes the impact of structural factors but also the role of choice and individual agency in shaping health behavior and overtime health lifestyles. The concept of health habitus allows us to escape the extremes of structural and of individual overdeterministic interpretations of health behaviors and this is why we chose the Health Lifestyle Theory for the B2C study.

Using the Health Lifestyle Theory in the design of the B2C study and the data analysis enabled us to collect data on the processes by which structural opportunities/barriers (e.g., living in an un/hygienic, un/safe SRO residence) interface with an individual’s choices (e.g., not/engaging in a drug-using network with fellow SRO residents) to shape an individual’s health habitus (e.g., the tendency to access medical care in an emergency department only when in a health crisis, or to medicate one’s depression with illegal drugs), and then behavior (e.g., not/accessing outpatient HIV care). This enabled us to go beyond the well-established relationship between housing instability, precariousness, or homelessness and adverse health outcomes, and to describe several of the mechanisms that account for this specific association between living in an SRO and not engaging in HIV outpatient care.

Methods

Sample Eligibility

To be eligible for the B2C study, participants had to: (1) be 21 years or older; (2) self-identify as non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic; (3) self-identify as HIV-infected; (4) be HIV-infected, based on medical record; (5) report having been diagnosed with HIV for at least two years; (6) be currently hospitalized in the Adult Infectious Disease unit of a large urban hospital; (7) have a most recent CD4 cell count under 350, based on medical record; and (8) report being disengaged from outpatient care. Disengagement was defined as one of the following: (a) no HIV outpatient scheduled visit in the past 6 months; or (b) missed at least one HIV outpatient scheduled visit in the past 6 months and were not on ART for the two weeks prior to hospitalization; or (c) in the past 12 months, had not been to at least two HIV outpatient scheduled visits separated by 90 days or longer. These different ways of defining disengagement were adopted due to the lack of consensus on how best to measure this outcome [27]. Seventy-one percent of the sample (71%) met the first and most stringent criterion (i.e., no scheduled HIV outpatient visit in past 6 months). Based on clinician’s assessment, patients with significant physical and/or cognitive impairment were excluded. Patients who self-identified as non-Hispanic White were also excluded because this study focused on the two racial/ethnic groups with the highest HIV prevalence in New York City [28].

Sample Recruitment and Screening

Potentially eligible participants admitted to the hospital’s Adult Infectious Disease unit were initially identified through medical records. These individuals were then approached and asked to participate in the study. Those interested were screened for remaining eligibility criteria at bedside, and screening typically lasted 20–25 min. If eligible, informed consent was obtained and, in most cases, the interview took place immediately after the screening. Otherwise, interviews were conducted later the same day or on the next day at the patient’s request. The first part of the interview consisted of an interviewer-administered sociodemographic questionnaire that included a few housing-related questions. The second part consisted of an in-depth qualitative interview that was audio-recorded and transcribed for content analysis. The qualitative interviews lasted on average 95 min (SD = 33 min). Ten interviews (8%) were conducted in Spanish. These interviews were first transcribed in Spanish and then translated in English by a translation company compliant with the researchers’ Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. The fidelity and quality of transcription and translation were assessed by two of the study’s bilingual interviewers as follows: they separately listened to the Spanish audio files and examined both the transcription and the translation, and next they jointly resolved any identified discrepancies. At the end of the interview, each participant received an honorarium of $75. All interviews were conducted between June 2012 and June 2014. The Institutional Review Board of the university and the hospital affiliated with the study and the authors approved the study.

Data Analysis

For this content analysis, we used a combination of two strategies, interacting with analytic profiles and with coded transcripts. After each interview, interviewers listened to the audio recording of their own interview and prepared an analytic profile (ranging from 7 to 20 pages) that summarized the interview. The profile summary addressed the research aims and the participant’s background and experiences related to the current hospitalization. These summaries also included the interviewer’s interpretations substantiated by verbatim data extracted from the interview. Each profile concluded with a description of the participant’s health habitus and how it affected their engagement in care. Analytic profiles are an effective way of organizing in-depth qualitative data without fragmenting or decontextualizing participants’ rich accounts. We have used this strategy in prior studies [29, 30].

Two research analysts read the analytic profiles for each participant included in this study to become familiar with the data and identify the sections and summaries that included housing-related data. These were mostly organized under the study aim that referred to the structural barriers and opportunities participants faced in caring for their health. Next, they independently coded a set of ten interview transcripts and the data excerpts in all profiles. They engaged initially in open and subsequently selective coding focusing on the topics of housing, health, use of and adherence to antiretroviral treatment and engagement in care. Substance use emerged as another important topic [31, 32]. After reconciling all coding differences, the two research analysts jointly coded five additional transcripts to finalize the coding scheme. The inductive codes generated by this process were the following: SROs and time (subcodes: transiency, in/stability); SROs and hygiene (subcodes: pests, un/clean, body invasion); SROs and substance use (subcodes: psychological, social and structural elements); and SROs and violence (subcodes: physical, symbolic). Health habitus, health behavior and health lifestyle, were the deductive codes that were also included in the coding scheme and interpretatively linked to the inductive codes. For instance, we linked the deductive code of the habitus of prioritizing immediate survival (i.e., securing shelter and food) over accessing medical care to the inductive code of being in a state of chronic living transiency associated with moving in and out of different SROs. This enabled us to identify how the “habitus of instability, insecurity and lack of control over one’s health” emerged out of the state of long-term transiency and resulted in not accessing outpatient medical care and becoming hospitalized. Similarly, we linked the deductive codes of the substance use behavior and lifestyle to the inductive codes of (1) being tempted by fellow substance users and SRO residents to use drugs (subcode: psychological factor) and (2) participating with fellow substance users and SRO residents into buying and sharing the drugs (subcode: social factor). Long duration of the same health behavior was used to define a health lifestyle.

We developed and applied the final coding scheme to all the transcripts manually, simply using the comment box and highlight functions of the WORD program. After extracting and interacting with the coded data and the full analytic profiles, we identified the following analytic themes: long-term transiency, embodiment of the SRO, SROs generating opportunities for drug use, and SROs as places of violence.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In this analysis, we included all B2C study participants that identified a Single Room Occupancy (SRO) or a hotel as a primary residence in the past year. Of the total sample of 120 participants, 44 (37%) met this requirement. All 44 participants reported receiving public assistance to cover the SRO or hotel room payment. SROs/Hotels constituted the most prevalent type of housing (37%), and a rented apartment paid for with public assistance was the second most prevalent type of housing (34%). For this analysis, we combined SROs with subsidized hotels because participants discussed them as the same type of residence, even when asked for clarification. Also, most participants lived in SROs that did not have on-site supportive services (63%), and this also suggested that the living conditions in subsidized hotels and SROs were very similar. Henceforth, the term SRO also refers to subsidized hotels.

Of the 44 participants included in this analysis, 29 (66%) were male, and 15 (34%) were female. Thirteen (30%) identified as Hispanic (henceforth called Latino/a) and 31 (70%) as non-Hispanic Black (henceforth called Black). Mean age was 45 years old (SD = 10). Twenty-eight participants (64%) were classified as active substance users, as assessed by the AUDIT and DAST standardized measures [33, 34]. Alcohol and crack/cocaine were the two most prevalent drugs of choice. The average number of hospitalizations in the past six months was 4.96. Using the definition of being homeless as, “not have your own place to sleep–not an apartment you were renting and not even a friend’s, or family member’s place you were welcome to stay at,” we found that 42 of the 44 participants reported ever having been homeless (96%) and 34 (77%) reported that their longest period of homelessness lasted more than six months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics

| Number | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 44) | ||

| Male | 29 | 65.9 |

| Female | 14 | 31.8 |

| Transgender | 1 | 2.3 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 44) | ||

| Non-hispanic black | 31 | 70.5 |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 13 | 29.5 |

| Sexual orientation (n = 44) | ||

| Completely heterosexual | 33 | 75.0 |

| Not completely heterosexual | 11 | 25.0 |

| Education (n = 44) | ||

| Less than high school | 24 | 54.5 |

| High school grad/GED | 12 | 27.2 |

| More than High School | 7 | 15.9 |

| Missing | 1 | 2.3 |

| Marital status (n = 44) | ||

| Married/domestic partnership/common law marriage | 7 | 15.9 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 19 | 43.2 |

| Single (never married) | 18 | 40.9 |

| Employment (n = 44) | ||

| Not employed | 42 | 95.5 |

| Employed | 2 | 4.5 |

| Substance use (n = 44) a | ||

| Active substance user | 28 | 63.6 |

| Not active substance user | 16 | 36.4 |

| Food insecurity (n = 44) b | ||

| Yes | 33 | 25.0 |

| No | 11 | 75.0 |

| Ever incarcerated (n = 44) | ||

| Yes | 37 | 84.1 |

| No | 7 | 15.9 |

| Ever homeless (n = 44) | ||

| Yes | 42 | 96 |

| No | 2 | 5 |

| Mean # Hospitalizations (past 6 months) | 4.96 |

Active substance use: Report any of the following 3 criteria: (1) used in the past 90 days: any injection drugs, heroin, other non-prescribed opioids, crack/cocaine, or methamphetamine; or (2) binge drinking in the past 90 days as defined by the AUDIT-C scale; or (3) substance abuse symptoms that yield a score of greater than 6 on the DAST-10 scale

Food Insecurity: “In the past 12 months, were you ever unable to eat because you could not afford food?”

The subsample of 44 participants was slightly more disadvantaged than the total sample of 120. They were significantly less likely to be employed, and significantly more likely to have ever experienced food insecurity and incarceration. However, there was no difference in terms of active substance use (data analysis not shown).

Qualitative Findings

To understand the different pathways that led from living in an SRO to health care disengagement, we describe below how participants’ residential experiences shaped their health habitus, behavior and lifestyle.

Long-Term Living Transiency--

SROs were ideally designed as a means of temporary housing to ensure individuals had shelter while transitioning to a more stable long-term housing situation. However, we found that SROs were a type of long-term yet unstable housing. The time restrictions on SRO length of stay (ranging from 28 days to 6 months) resulted in participants often having to move out of one SRO and into another, while waiting for an apartment. Other regulatory aspects of SROs (e.g., curfews, prohibiting being absent for one night or having visitors) often led to the expulsion of residents, moving in and out of different SROs and experiencing housing instability. Substandard living conditions and endemic substance use that characterized most SROs also contributed to this phenomenon of cycling in and out of SROs. In general, participants described becoming trapped in a discouraging cycle of housing instability as they moved through SROs, shelters, the street, hospitals and nursing homes. For instance, a 37-year-old Latina participant referred to her housing instability as the primary barrier in caring for her health. She regarded SROs, hotels and shelters as similarly unstable abodes. Asked about the last time she went to an outpatient HIV clinic, she replied:

Participant (P): I can’t recall. That’s how long it’s been. In and outta shelter system. In and out, in and out, in and out. … Shelters. … Like women’s shelters and stuff like that. SROs. Hotels. … I started doing a lotta things [relapsed in drug use]. I seen people that I know. I started staying at friends’ houses. … I didn’t have a permanent residence, no. Wherever I seen a place for me to sleep warm, I laid. … Slept in a building, in abandoned buildings and stuff like that. … Housing. Homelessness. All that. Screwed my life up. How? Not bein’ able to feed myself right. Have to find pantries, this and that. Can’t walk that much. Can’t breathe. Stupid stuff.

Interviewer (I): And how did it [housing instability] also affect your taking care of your health?

P: It made me not wanna get outta bed and stuff, you know. I don’t know. I just didn’t want to get out the bed.

Rather than protecting participants from housing instability, SROs contributed to a state of long-term living transiency that often lasted for years. When asked how long he had been living in different SROs, a 43-year-old male Black participant said: “Off and on? That’s hard to explain, but I’m gonna say, maybe, about four or five years.” He preferred being in the hospital than restarting the SROs cycle and asked to be discharged to a nursing home:

I didn’t want, I mean, I’ve been to all the SROs. It’s not my first time, being in an SRO. But I felt, felt more secure here [in the hospital] than I did anywhere else at this point in time, and I didn’t wanna have to go back out there in the streets. And, you know, and deal with going to another place [SRO] or something like that.

A 53-year-old male Black participant that had been moving from one SRO to another for the past two years described the barriers to getting an apartment:

I’m goin’ through that with my social worker. You know, I get her, I say, “I want my own place.” And she keep tryin’ to put me in these SROs, and I keep tellin’ her, “I don’t want no SRO. I want my own place.” So now she’s puttin’ me in these places. And I’m gettin’ sick, and I’m endin’ up in the hospitals. … She said that there’s a lot of people that need housin’. I’m not the only one. You know, and I says to her, I said, “Well, I’ve been goin’ to SRO for years. You shoulda been helping me get a place. And I’m on SSI. So, what is the problem?” … but I’d rather go in a nursing home and let ‘em deal with it from there.

As the quote above indicated, the shortage of subsidized apartments combined with a complex bureaucratic process of finding and getting approval for such a unit contributed to participants staying in the SRO system for years and SROs becoming long-term abodes. This participant also suggested that the unhygienic conditions in the SROs had undermined his health and resulted in his hospitalization. This theme is discussed next.

Embodiment of the SRO--

Most participants attributed their dissatisfaction with living in an SRO to the substandard quality of these dwellings. Terms such as “filthy” and “nasty place” were used to describe the lack of cleanliness and unsanitary conditions of the SRO buildings and rooms. Some participants found the conditions in SROs so appalling that they elected to leave. For instance, a 50-year-old female Black participant attributed her non-adherence to ART and her dermatological problems that led to her hospitalization to the SROs’ intolerable conditions that triggered her living instability:

‘Cause for it [non-adherence] was because of my housing situation. You know, and the nasty places the HIV housing program will put me in, was broken. I can’t sleep with the SRO they gave me, the one they got me in, so I, I’ll go, I’ll sleep in the car for a couple days. Stuff like that, yeah. And I hadn’t been able to keep up with my wound care or my HIV meds. … Like I tell them [the physicians], I says, “Listen, for me having HIV virus, right, it’s like I don’t have that first coat of protection around me no more.” … I have caught a skin form of infection [from the SRO]. … Cause if I had to sleep in the street or emergency room or here and there, how do you expect me to get to my appointment? I can’t even wash.

Participants perceived the unhygienic conditions of SROs as becoming physically incorporated, literally embodied through their encounters with insects and bacteria, and making them sick. Shared bathrooms, showers and kitchens that were dirty were described as particularly dangerous spaces, given participants’ immunocompromised status. This health concern contributed to living instability and participants’ distress, as a 32-year-old male Black participant who had lived in SROs for the past three years suggested:

But then I don’t know if, that [skin problems] it’s due to the living conditions I lived in because a lot of the hotels I lived in had bed bugs and stuff in it. … [Stopped going to clinic and taking ART because] I had lost that place [apartment], and then I was looking for housing, and I lost my job, so I had to go on welfare, so then, they started trying to put me in these programs [including SROs] and stuff like that … I just was caught up in a, going to different shelters, or hotels. …I got a little distressed about that [living in different SROs] because, I mean, I just want to find a regular job so I can pay my own rent.

Similarly, a 43-year-old Latino participant attributed his ill health and hospitalization to living in an SRO with others who had advanced HIV disease. He considered getting an apartment as a way to protect his health:

… this infection had to do with where I live. Where I live, I’m living, there are a lot of people with a lot of infections. With AIDS; almost all have AIDS, all once get an illness, a bacteria, they give it to me since I have it [immune system] low, they give it to me. I have to live alone; like that in a room, I cannot live with people and even more with this disease, you understand me? And much less living with my blood that is sick, I’m going to wake up sick.

SROs Generating Opportunities for Drug Use--

Extensive drug use activity within SROs was another widespread complaint. Although some participants who did not use drugs indicated that they felt “uncomfortable” and unsafe when invited to purchase and use drugs, the presence of drugs on premises was most deleterious for current and past users who reported feeling tempted to use and often relapsed or continued using. For instance, a 57-year-old Latino participant who was an active crack/cocaine user indicated that living in SROs undermined his sobriety: “I still, still have that problem [drug use]. That is why I want to go to the nursing home; those hotels [SROs] are full of drugs. … ended up in hotels, so [I relapsed].” Many participants attributed their disengaging from care to living in SROs and relapsing or continuing to use drugs. For instance, a 31-year-old Latino participant described relapsing and housing instability as almost inevitable when one resides in SROs:

Well, I’ve been to quite a few of them [SROs] because people don’t last, or you don’t wanna be there because those places are just so infested with crack; cocaine; alcohol. And people just knocking on your door and bothering you. And they don’t even know you, and they wanna know if you wanna get high, or, you know, they try to see if you wanna sell your pills [ARTs]. … if you have your place and you’re stable you can continue to do it [go to clinic] and see the same person [provider] over and over, but if you’re not stable, and you’re going from SROs to hotels to this, jumping from here, you never know where they’re gonna send you. … someone ends up at your door, and you end up messing up, whether it’s alcohol, crack, cocaine, crystal meth; you name it. There’s all, all over those SROs, they’re all over. And I know they say it’s, all depends on the person, but when the urge is there, and you have someone, uh, pushing it, and you see that it’s all over the building…

Social and structural features of SROs were also conducive to promoting drug use and trafficking of street drugs and of antiretroviral medications. Residents who wanted to use drugs invited fellow residents to partake in purchasing and using drugs by knocking on their door. Money to buy drugs was often earned through selling antiretroviral medications or through exchanging sex. The enclosed space of SRO rooms allowed for the consumption of drugs on the premises. These experiences were echoed in the account of a 40-year-old female Black participant who had been living in SROs for approximately six years and who also attributed her disengagement from care to using drugs:

P: I got sidetracked again. People was knocking on my door, and you know, sending me out [to purchase drugs]. Sending me out and stuff like that; knocking on my door.

I: In the SRO, right? Do you think, if you were living in another apartment, things might be different?

P: Apartment by myself, yeah, it would be, because everybody in the SRO gets high, everybody. … If they’re not drinking, they’re smoking. If they’re not smoking, they’re sniffing, they’re shootin’, they’re doing something. Pills and everything. … Prostitution, everything.

I: Who’s buying the HIV meds?

P: A couple of people on the streets, you know, different people. … we go outside and meet ‘em. I’ll call and, you know, I’ll call ‘em. But I haven’t did that recently. I haven’t did it in about, I haven’t sold my medication in about three months.

SROs as Places of Violence: Physical and Symbolic--

Another feature of SROs that made them undesirable and dangerous was the threat and occurrence of violence. We identified two types of violence: physical and symbolic. Symbolic violence was defined as the violation of participants’ privacy, independence and loss of possessions.

Many of the participants reported feeling unsafe in SROs, because of the threat of physical violence from other residents. This concern was often based on having witnessed violence between other residents and the police being called. For instance, a 43-year old male Black participant explained how violence contributed to his living on the street and housing instability:

The last place I was at, I left after being there for like two days. No, actually, one night because it was so much trials and tribulations … two people came and they was arguing about sumpin’. … A man talkin’ about he gonna call the police on somebody else. Um, they runnin’, back and forth, up the stairs, and I heard a whole bunch of tusslin’. Then I hear the police coming. … I must’ve slept for about an hour, maybe an hour and a half. And soon as I seen the light comin’ through the window, I, I put my clothes back on and I left.

A 42-year old Latino participant attributed the violence to the residents’ drug use and explained how he protected himself:

… because there is crackheads everywhere in the building, knocking on the door for cigarette. Knocking door for chew gum. Knocking door for a meal. And sometimes, I got, got a bat. But I got in there and a few times, had to get the bat and open the door, “Yo, get the [expletive] outta here. I will break your [expletive] head.” Because they disrespectful to you because 3:00 in the morning, 4:00 in the morning, knocking the door to ask you for cigarette.

Participants were also exposed to different forms of symbolic violence while living in SROs such as, being evicted from their room and losing their possessions. Residents’ absence from the SRO for a certain time period (ranging from one night to several days) typically gave management the right to dispose of their belongings and give their room to another resident. Participants referred to this experience as “being closed out” and indicated that this occurred even when they became hospitalized. A 51-year-old male Black participant described such an experience:

I ended up losing everything, all of my possessions. … I lost them, being in the damn hospital. SROs close your room and throw your stuff out or give it away. …I’m just mad. It took me, it took me a year to build up everything that I, I had, up until last Friday, then they just take it upon themself to throw my stuff away, which I know they didn’t throw it away, because everything is brand new [TV, stereo]. … I’m looking to, get my own apartment though. That’s what I want. I don’t want no single-room occupancy. … [Without an apartment] You don’t have no foundation. And it affects you in many different areas, multiple areas. Cuz you’re not stable. You’re not, not on your square. You’re always off balance. If you’re off balance, everything else is suspect to suffer. If you’re got a concrete place, a stable place, everything is easy, cuz, you know, you’re organized, you’re situated. You can have your medication delivered to your door.

Another expression of symbolic violence was the lack of privacy in SROs that detracted from participants’ sense of safety and wellbeing. Management and fellow residents often did not respect the privacy of the residents’ room. For instance, many SROs did not allow residents to lock their rooms. Being unable to lock one’s door, intrusive behavior by fellow residents and having items stolen from their room were discussed as violations of privacy and independence. For instance, a 32-year-old male Black participant explained that the lack of privacy weakened his ability to stabilize his life, “build myself up… gather my thoughts”:

… they would come in your room when they wanted to, like invasion in your privacy, knock at your door real hard like you were a prisoner at jail and scream your name out in the hallways and stuff like that, which is real ignorant. And this is not, it’s not comfortable.

Antiretroviral medications to be sold on the street were the items typically stolen from participants’ rooms, even in SROs that allowed residents to lock their rooms, as a 58-year-old male Black participant explained:

SROs can mislead you. You know why? Cuz most of the people want you to sell the medicine or they steal it from you. I had my medicine stolen nine times, all in all. They broke the window. They took and put the lock, jimmied the lock that I put.

Some SROs also imposed a curfew and prohibited residents from having visitors further undermining their independence. A 58-year-old male Black participant explained his decision to leave the SRO:

I didn’t like that because there’s a curfew. I didn’t have a key to my room, and they got tired of coming upstairs to open the door, but “Why don’t y’all just give me a key?” So, I had to put tape and close the door, like I would, and slam lock it. And I’d make sure nobody seen me pushing the door and going in, but I’d take the tape off, when I go to sleep.

Discussion

Subsidized SRO residences and subsidized hotels not part of supportive housing programs-are intended but fail to serve as temporary short-term residences for PLWH and other persons with medical and/or psychosocial vulnerabilities. These living arrangements were found to be unsanitary residences characterized by drug use and violence that did not afford any housing stability or security. These living conditions activated different processes that reinforced one another and resulted in participants cycling in an out of different SROs, shelters, nursing homes, hospitals, and the street. This state of long-term living transiency contributed to a habitus of instability, insecurity and lack of control over one’s life that fostered behavior detrimental to engaging in HIV outpatient care. The Theory of Health Lifestyle [23, 24] that emphasizes the role of housing and other structural factors in generating barriers and informing choices that shape our health habitus, that is, our tendencies to take care of our health in certain ways, emerged as an appropriate framework for understanding how living in SROs affects health behavior and lifestyles.

The unhygienic conditions of SROs combined with the participants’ immunosuppression were perceived as an underlying cause of different symptoms, poor health and, at times, of their hospitalization. Participants attributed physical, often dermatological symptoms to the filth and vermin found in SROs, and perceived fellow HIV-infected residents as vectors of infections and therefore, dangerous. These SRO conditions generated feelings of distress, disgust and lack of control over one’s health, and motivated many to leave the SRO and live on the street, in their car, or in a shelter. This behavior increased their living instability and exposure to health risks. The lack of a safe, clean and acceptable place to live, deprived participants of the ability and motivation to prioritize caring for their health, including adhering to their ART regimen and scheduled HIV outpatient visits. Some fled the SRO to seek medical care in emergency rooms or in nursing homes which further undermined a habitus of routine medical care-seeking and instead, reinforced a habitus of instability, insecurity and lack of control over one’s health.

A few HIV studies have identified an association between living in substandard housing and experiencing poor physical and mental health [35, 36]. For instance, Rourke and colleagues [36] found that among PLWH, higher satisfaction with the material, meaningful and spatial features of one’s residence (i.e., location) was associated with significantly higher mental health-related quality of life. Also, the older PLWH interviewed by Furlotte and colleagues [35] viewed the poor conditions in boarding homes as a sign of disrespect, and public shelters as germ-ridden, dangerous places. However, prior studies have not focused exclusively on SROs and moreover, did not examine how the quality and meaning of housing shaped tendencies and behavior. We extended this literature by revealing how defining SROs as unhealthy, dangerous places generated feelings of distress and lack of control and fostered a habitus and related behaviors (e.g., fleeing the SRO or seeking care in emergency departments) that increased living precariousness and health risks, and undermined engagement in routine medical care.

This analysis also revealed how psychological, social and spatial features of SROs facilitated substance use, sex exchange, medication diversion and undermined health and engagement in medical care. The lack of privacy and control over one’s space in SROs combined with the concentration of residents who use drugs led to the formation of a drug-using peer network. Residents engaged in sex, drugs and ART exchange, encouraged by fellow drug-using residents. These opportunities for drug use reinforced participants’ preexisting habitus of substance use that resulted in continued druguse or relapse, other illegal activities, incarceration or hospitalization thus, furthering their living instability. All these behaviors directly undermined adherence to medication and outpatient visits, and health. For the residents who were either not involved in or no longer tempted by drug use (36% reported no active substance use), the drug-related activities in SROs contributed to their perceptions and assessments of their living space as unsafe and undesirable. This reinforced their habitus of insecurity, lack of control and disrespect that motivated some to leave the SRO thus, activating a different mechanism of housing instability for this group of residents.

Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong association between housing instability and/or homelessness and increased substance use, decreased ART adherence and engagement in HIV care, and worse health outcomes [1, 5, 37, 38] These studies have identified mediating factors, such as ART medication diversion [37] or depression and anxiety [38] that bridge housing instability or homelessness to lack of adherence to ART or non-suppression, among PLWH who use substances. This analysis’s contribution is that it revealed several mechanisms linking specific psychological, social and spatial conditions in SROs, to tendencies and behaviors that directly and indirectly undermine ART adherence, engagement in HIV care and the health of substance-using PLWH.

Physical and symbolic violence was ubiquitous in SROs, and it activated several processes that undermined living stability, privacy, autonomy, self-efficacy and ultimately, medication adherence and engagement in care. Perceiving fellow residents as potentially violent, motivated participants to leave an SRO or to refrain from establishing any social connections thus, amplifying their social isolation and living instability. The SROs’ operational rules and policies also exposed residents to violence. Management typically evicted participants for being absent for a night or more and seized their possessions. Eviction and disregard for a resident’s possessions which are considered an extension of one’s self and features of one’s identify, constitute acts of violence. Personal possessions, including antiretroviral medications, were also stolen by fellow residents either because SROs did not allow participants to lock their rooms or because locks were violated by fellow residents. The threat of losing one’s room and possessions heightened participants’ sense of lack of control and autonomy. Rules such as curfews, not providing a key to one’s room, and restricting visitors further undermined residents’ autonomy and intensified feelings of being under surveillance and controlled. These experiences linked to the restrictive and punitive housing rules contributed to a habitus of confinement, lack of control and disrespect, akin to the habitus participants associated with being in the carceral system. As one participant explained, the lack of privacy and respect in SROs made him feel like a prisoner. Given that more than 80% of this sample had experienced incarceration, drawing this parallel between SRO and prison is particularly salient. This habitus of confinement, lack of control and disrespect was detrimental to developing self-efficacy and taking control over one’s health by engaging in routine medical care. Participants who could not tolerate the SROs’ infringement upon their person, elected to leave their room thus, perpetuating their living instability.

We found only a couple of studies on marginally housed impoverished women and persons who use drugs [20–22] that discuss the presence of violence in subsidized housing, including SROs. Boyd and colleagues [20] noted that in Vancouver, subsidized housing residents with substance use and mental health disorders were subjected to different forms of surveillance and social control that seemed antithetical to harm reduction and current public health practice. Our analysis extends this discussion by explaining how the endemic physical and symbolic violence in SROs deprived residents of autonomy, self-worth and self-efficacy, and contributed to a habitus antithetical to focusing on and proactively caring for one’s health, including engaging in outpatient care.

Despite their shortcomings, SROs remain a significant housing resource especially in large cities with expensive and saturated real estate markets such as New York, Chicago, or San Francisco and will continue to house medically and psychosocially vulnerable persons [13]. The challenges of SROs stem primarily from the: (1) lack of investment in the buildings and failure to meet the safety and sanitation standards for multi-unit residential facilities; (2) overly restrictive and often punitive manner of operation and management; and (3) lack of integration of supportive services such as drug treatment, medical care or care management to address the residents’ multifaceted needs. Addressing these core issues, will not necessarily transform SROs into a home but might produce stability, security and a sense of control over one’s life which can enhance residents’ health and engagement in health care. For instance, providing care management, linkage to outpatient substance use and mental health treatment to residents in subsidized apartments and SROs, has proven effective in prolonging AIDS-free survival [38–40]. Any suggestion to improve the quality of SRO buildings, their cleanliness and integration of supportive services, raises the issue of cost for those operating SROs and for the public funds, such as HASA’s emergency housing program, that subsidize the residence of PLWH in these units. However, given that all the participants received public assistance to cover their stays in SROs, regardless of whether they were operated commercially or by non-profit agencies, the question that emerges is whether public subsidies that are being spent are used to protect PLWH or further expose them to health risks.

Finally, we also suggest the need to change the SROs’ operational rules and monitoring policies to prevent the formation of drug-using networks and the exploitation of SRO residents by the illegal ART and drug market. However, these changes must be informed by a harm reduction instead of a punitive, social control approach because SROs are already perceived as coercive spaces.

The limitations of this analysis are associated first with the purposive, non-representative nature of the sample. The findings are based on in-depth interviews with 44 inpatients from one urban hospital and therefore, should not be generalized to other patient populations and settings. Second, the participants in the B2C sample were not engaged in HIV medical care, were non-adherent to ART and were hospitalized and therefore, quite ill. Indicatively, the mean number of hospitalizations in the past six months for the SRO residents was almost five times. These characteristics indicate that the sample was more marginalized and severely ailing than the typical clinic- or community-based samples of PLWH included in most studies and this also restricts the generalizability of the findings. However, since the participants in this analysis are typically excluded from HIV studies, their perspective and experiences do add to the extant literature. For instance, the fact that the participants were disengaged from HIV care and had poor health status provided a number of rich and detailed accounts on the different features of SROs that influenced the residents’ health-related tendencies, behavior, and health; a specificity than can inform SRO-focused interventions.

Although not a limitation per se, the fact that the interviews were conducted at bedside in the hospital should also be considered. Health issues were particularly salient in participants’ minds given their hospitalization. This primarily motivated them to consider why they became hospitalized and how their housing situation might have contributed to their current health status. Also, as the data suggested, being in the hospital gave participants the opportunity to compare the safety and cleanliness of the hospital to those of the SROs.

Lastly, two study features potentially extend the significance of the findings beyond its sample. First, the study was theoretically guided, and the Theory of Health Lifestyle revealed a variety of processes that explained how specific psychological, social, structural and operational features of a particular type of housing i.e., an SRO, shaped the residents’ habitus and behaviors that undermined caring for one’s health, including engaging in care. Translating on a more abstract level these processes that linked housing characteristics to habitus, health behaviors and outcomes can shed light on how the psychological, social, structural and operational features of other types of housing can shape habitus, behavior and health. Second, the analysis focuses exclusively on the experience of living in an SRO without a priori defining whether this type of housing renders its residents homeless, unstably or stably housed and thus, bypasses the literature’s lack of clarity on the classification of housing status.

Staying in different single room occupancy residences emerged as a long-term living situation that often lasted for years. Moreover, SROs were characterized by unsanitary conditions, substance use and violence that contributed to living instability, insecurity and lack of control over one’s health. By explaining how these SRO conditions contributed to a habitus and behaviors that undermined health and engagement in medical care, this manuscript highlighted the need to invest in SROs and transform them from risk to protective environments.

Funding

This manuscript is based on a grant funded by NIH R01 MH095849 (PI: Helen-Maria Lekas and Lisa Rosen-Metsch).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None of the Authors have any conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval As indicated on page 8 of the Blind copy of the manuscript: “The Institutional Review Board of the university and the hospital affiliated with the study and the authors approved the study.”

Consent to Participate The consenting process was described in pages 7 and 8 of the Blind copy of the manuscript and was approved by the IRB of the university and hospital affiliated with the study and the authors: “Potentially eligible participants admitted to the hospital’s Adult Infectious Disease unit were initially identified through medical records. These individuals were then approached and asked to participate in the study. Those interested were screened for remaining eligibility criteria at bedside, and screening typically lasted 20–25 min. If eligible, informed consent was obtained and, in most cases, the interview took place immediately after the screening.”

Consent for Publication The manuscript is based on verbatim excerpts from in-depth interviews and survey data. These data were elicited through patient interviews for which we obtained IRB permission. We have IRB permission to publish out findings, provided we de-identify the data which we did. We had also obtained a federal certificate of confidentiality to further protect the study participants’ confidentiality.

Data Availability

Based on the IRB, only persons on the IRB protocol and affiliated with the study have access to the data.

References

- 1.Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living With HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Royal S, et al. Access to housing as a structural intervention for homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV: Rationale, methods, and implementation of the housing and health study. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):149–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milloy MJ, Marshall BDL, Montaner J, et al. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. CURR HIV-AIDS REP. 2012;9(4):364–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin JJ, Botsko M, Behar E, Finkelstein R. More than ancillary: HIV social services, intermediate outcomes and quality of life. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Bangsberg DR, et al. Homelessness as a structural barrier to effective antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(1):60–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rourke SB, Bekele T, Tucker R, et al. Housing characteristics and their influence on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV in Ontario, Canada: Results from the positive spaces, healthy places study. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2361–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie CM, Wiewel EW, Zhong Y, et al. Multilevel factors associated with a lack of viral suppression among persons living with HIV in a federally funded housing program. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):784–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parashar S The place of housing stability in HIV research: A critical review of the literature. Housing Theory Soc. 2016;33(3):342–56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aidala AA, Sumartojo E. Why housing? AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn JR, Hayes MV. Social inequality, population health, and housing: A study of two Vancouver neighborhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(4):563–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somerville P. Homelessness and the meaning of home: Rooflessness or rootlessness? Int J Urban Reg Res. 1992;16(4):529–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proctor E Single room occupancy housing. In: Carswell AT, editor. The encyclopedia of housing. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012. p. 678–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NYC Human Resources Administration. HIV/AIDS services administration https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hra/help/hasa-faqs.page. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

- 15.Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2 Suppl):101–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldrop-Valverde D, Valverde E. Homelessness and psychological distress as contributors to antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19(5):326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parashar S, Palmer AK, O’Brien N, et al. Sticking to it: The effect of maximally assisted therapy on antiretroviral treatment adherence among individuals living with HIV who are unstably housed. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushel M, Colfax G, Ragland K, Heineman A, Palacio H, Bangsberg DR. Case management is associated with improved antiretroviral adherence and CD4+ cell counts in homeless and marginally housed individuals with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(2):234–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowen EA, Mitchell CG. Homelessness and residential instability as covariates of HIV risk behavior among residents of single room occupancy housing. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2016;15(3):269–83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd J, Cunningham D, Anderson S, Kerr T. Supportive housing and surveillance. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;34:72–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight KR, Lopez AM, Comfort M, Shumway M, Cohen J, Riley ED. Single room occupancy (SRO) hotels as mental health risk environments among impoverished women: The intersection of policy, drug use, trauma, and urban space. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):556–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shannon K, Ishida T, Lai C, Tyndall MW. The impact of unregulated single room occupancy hotels on the health status of illicit drug users in Vancouver. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):107–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockerham WC. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(1):51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cockerham WC. Bourdieu and an update of health lifestyle theory. In: Cockerham WC, editor. Medical sociology on the move: new directions in theory. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. p. 127–54. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourdieu P Outline of a theory of action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourdieu P The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(5):574–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. 2018.

- 29.Lekas HM, Siegel KS, Leider J. Felt and enacted stigma among HIV/HCV adults: The impact of stigma layering. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(9):1205–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegel K, Meunier E, Lekas HM. Accounts for unprotected sex with partners met online from heterosexual men and women from large US metropolitan areas. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(7):315–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Given LM, editor. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods, vol. 1–2. Thousand Oaks, Cal: SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saldaña J Qualitative data analysis the coding manual for qualitative researchers, 3rd ed. Vol. 12, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):781–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(2):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furlotte C, Schwartz K, Koornstra JJ, Naster R. ‘Got a room for me?’ housing experiences of older adults living with HIV/AIDS in Ottawa. Can J Aging. 2012;31(1):37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rourke SB, Bekele T, Tucker R, et al. Housing characteristics and their influence on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV in Ontario, Canada: Results from the positive spaces. Healthy Places Study AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2361–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surratt HL, O’Grady CL, Levi-Minzi MA, Kurtz SP. Medication adherence challenges among HIV positive substance abusers: The role of food and housing insecurity. AIDS Care. 2014;27(3):307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wainwright JJ, Beer L, Tie Y, Fagan JL, Dean HD, Medical Monitoring Project. Socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of persons living with HIV who experience homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(6):1701–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall G, Singh T, Lim SW. Supportive housing promotes AIDS-free survival for chronically homeless HIV positive persons with behavioral health conditions. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):776–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunningham CO, Shapiro S, Berg KM, Sacajiu G, Paccione G, Goulet JL. An evaluation of a medical outreach program targeting unstably housed HIV-infected individuals. J Health Poor Underserved. 2005;16(1):127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Based on the IRB, only persons on the IRB protocol and affiliated with the study have access to the data.