Abstract

Tumor acidity is one of the cancer hallmarks and is associated with metabolic reprogramming and the use of glycolysis, which results in a high intracellular lactic acid concentration. Cancer cells avoid acid stress major by the activation and expression of proton and lactate transporters and exchangers and have an inverted pH gradient (extracellular and intracellular pHs are acid and alkaline, respectively). The shift in the tumor acid–base balance promotes proliferation, apoptosis avoidance, invasiveness, metastatic potential, aggressiveness, immune evasion, and treatment resistance. For example, weak-base chemotherapeutic agents may have a substantially reduced cellular uptake capacity due to “ion trapping”. Lactic acid negatively affects the functions of activated effector T cells, stimulates regulatory T cells, and promotes them to express programmed cell death receptor 1. On the other hand, the inversion of pH gradient could be a cancer weakness that will allow the development of new promising therapies, such as tumor-targeted pH-sensitive antibodies and pH-responsible nanoparticle conjugates with anticancer drugs. The regulation of tumor pH levels by pharmacological inhibition of pH-responsible proteins (monocarboxylate transporters, H+-ATPase, etc.) and lactate dehydrogenase A is also a promising anticancer strategy. Another idea is the oral or parenteral use of buffer systems, such as sodium bicarbonate, to neutralize tumor acidity. Buffering therapy does not counteract standard treatment methods and can be used in combination to increase effectiveness. However, the mechanisms of the anticancer effect of buffering therapy are still unclear, and more research is needed. We have attempted to summarize the basic knowledge about tumor acidity.

Keywords: cancer, metabolism, acidity, hallmark, treatment target

Introduction

Cancer cells have an inverted pH gradient: extracellular and intracellular pHs (pHe, pHi) are acid and alkaline, respectively (1). The acid shift in the tumor microenvironment (TME) is closely associated with hypoxia (2) but, more specifically, with highly activated glycolysis in tumor cells. Even in normoxia, about 80% of all malignant tumors use aerobic glycolysis, described as the Warburg effect (3), which is an integral part of metabolic reprogramming and sustaining biosynthetic pathways in cancer cells (4).

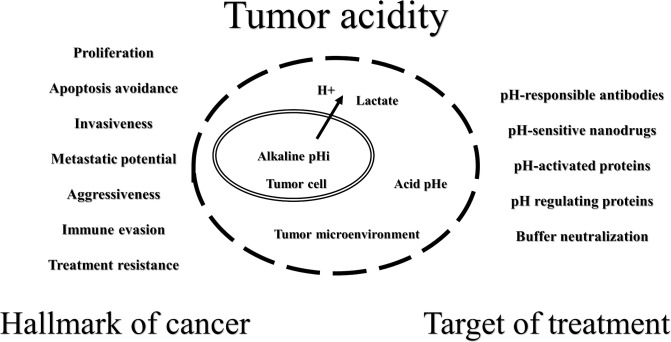

According to the present knowledge, the shift in the tumor acid-base balance promotes proliferation, apoptosis avoidance, invasiveness, metastatic potential, aggressiveness, immune evasion, and treatment resistance (5–8). On the other hand, inversion of the pH gradient in tumors could be a weakness that will allow for the development of new promising therapies ( Figure 1 ). It is possible to create acid stress inside cancer cells by inhibiting proton release systems or by using drugs that decrease mitochondrial activity to increase lactate production (5, 9, 10). The acidity of the TME could be used for the drug delivery of cytotoxic agents and/or carriers that are more active and/or change physicochemical properties under such conditions (11–13). It is very attractive to increase the pHe by a combination of an alkaline diet and bicarbonate therapy (14–16) or by direct local isolated perfusion of the tumor with bicarbonate solutions (17, 18).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of tumor acidity properties.

Obviously, the altered acid-base state of the tumor affects every stage of cancer development, from dysplasia to metastatic disease (1, 2). In this mini-review, we have attempted to summarize the basic knowledge about tumor acidity from hallmark of cancer to target of treatment.

Tumor acidity as a hallmark of cancer

One of the causes of tumor heterogeneity is altered tumor vasculature, which leads to different perfusion of nutrients and oxygen and to the accumulation of acidic metabolites (19, 20). Due to the reprogramming of metabolism in such conditions and the use of glycolysis as a major source of ATP production, tumor cells have an acidic pHe (6.4-7.1) and an alkaline pHi (7.1-7.8). For normal tissues, the pHe is around 7.4, and the pHi is around 7.2 (2, 21). Large amounts of lactate produced during glycolysis result in a significant increase in the intracellular proton (H+) concentration. It should be noted that glutaminolysis is another way for ATP production and an additional source of lactate and H+ in cancer cells (21–24). In addition, glutamine uptake and metabolism in oxidative cancer cells can be promoted by lactate (25). However, even in the presence of oxygen, glucose is almost completely converted into lactate. At the same time, glutamine is not fully respired, but it is rather fermented into lactate or pyruvate. Increased glutamine flux can enhance aerobic glycolysis and make it optimal for tumor proliferation (22, 26).

As acid stress triggers apoptosis (27), cancer cells use several ways to evade it (28). Activation and expression of H+ (and lactate) transporters and exchangers are the main mechanisms of tumor cell adaptation to intracellular acidification and of the inverted pH gradient phenomenon (29–32). It should be noted that not only H+ ejection systems lead to an increase in the pHi, but also a reduction of CO2 by decreased activity of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (1, 10). Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) additionally support the pH regulation of cancer cells by catalyzing the reversible hydration of CO2 to HCO3− and H+ (32).

Acidosis of the TME is an essential stage associated with high rates of tumor cell proliferation (33). Numerous studies have shown a role for tumor acidity in acquiring aggressive cancer characteristics, so it is recognized as a hallmark of cancer (21, 31, 34–36). For example, melanoma cells exposed to acidosis are characterized by a high invasive potential, high resistance to apoptosis and drug therapy, fixed independent growth, and a phenotype of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (37). Under growth factor limitations, alkaline pHi favors cancer cells survival (38). The acid adaptation of tumor cells leads to a gene expression response that correlates with human cancer tissue gene expression profiles and survival (39). Acidic TME improves the activity of regulatory T-cells and inhibits effector T-cells (40). In view of the foregoing, acidic TME could serve as an incubator that represses overabundant proliferation and cultures cells with a restricted growth rate but with strong proliferative potential (41). Clinicians should consider tumor acidity when diagnosing and determining optimal treatment, as it is also connected with poor cancer patients prognosis (39).

A wide range of non-invasive and minimally invasive imaging modalities have been studied preclinically for tumor pH monitoring, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and spectroscopy, positron emission tomography, electron paramagnetic resonance, and optical and photoacoustic imaging (42). To date, among the methods used, MRI appears to be the most promising, particularly chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI, which has good in vivo sensitivity for assessing tumor acidosis and changes in pH after therapeutic treatment, with a high spatial resolution to determine the heterogeneity of extracellular acidification. For example, CEST MRI has been used successfully to map tumor pH in a rabbit liver cancer model (43). In another study, tumor acidosis assessed by CEST MRI revealed the metastatic potential of breast cancer in mice (44). Translating the results of preclinical studies into clinical trials is only beginning to yield significant results. CEST MRI shows good results for measuring pH in ovarian cancer patients (45). In addition, CEST MRI has recently been shown to differentiate between benign and malignant liver tumors in patients (46). However, it is still difficult to routinely measure the pH of tumors in the clinic. In addition to direct measurements, tumor acidity can be assessed indirectly by determining the concentrations of bicarbonate (47) and lactate ions in the blood and using biopsy data (48). However, each clinical situation requires an individual approach.

Tumor acidity and tumor resistance

Cancer cell survival strategies in acidic TME promote resistance to radiation and chemotherapy. Radioresistance is closely related to hypoxia. Available clinical data show that the presence of large hypoxia areas in solid tumors is associated with a poor prognosis in cancer patients after radiotherapy (49). The cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation are mainly due to damage to genomic DNA as a result of the indirect action of generated free radicals (50). Molecular oxygen must be present during irradiation, which is insufficient under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia also prevents DNA repair and leads to the inhibition of the G1/S cell cycle checkpoint, an increase in DNA errors, and an increase in chromosomal instability. At the same time, the alkaline pHi of tumor cells prevents mitotic arrest initiated by activated checkpoints during DNA damage (21, 51). Thus, the inversion of the pH gradient of the tumor is a “partner” of hypoxia in creating conditions for radioresistance, and clinicians should consider acidic TME in the planning of radiation therapy.

Acidic TME itself can lead to chemoresistance due to ongoing physicochemical changes in the structure and charge of drugs. Weak-base chemotherapeutic agents, such as vincristine, mitoxantrone, doxorubicin, vinblastine, and paclitaxel, may have substantially reduced cellular uptake capacity due to neutralization or protonation [“ion trapping” (52)]. Therefore, the cytotoxic effects of these drugs may be reduced, resulting in a stable tumor phenotype. Interestingly, reversing the pH gradient may increase the intracellular concentrations of some weak-acid drugs, including cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil (53–56). Acidic TME induces p-glycoprotein (multiple drug resistance (MDR) protein) activity by promoting p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (57–59). Tumor acidosis induces the expression of the transcription factor SOX2 by inhibiting vitamin D receptor-mediated transcription, which also results in drug resistance (60). Oxidation-induced lactic acidosis increases resistance to uprosertib, a serine/threonine protein kinase inhibitor, in colon cancer cells (61). To obtain the maximum effect of chemotherapy, the acidity of the TME must be considered.

Current knowledge strongly suggests that acidic TME inhibits the antitumor immune response, although the complication of experimentally measuring tumor acid-base status makes it difficult to obtain direct evidence (7, 62). For instance, a decrease in the pHe leads to a decrease in the activity and proliferation of T cells (63, 64). In an acidic environment, effector T cells require higher thresholds for full activation and co-stimulatory signals (e.g., CD28) and show increased negative regulatory signaling through upregulation of interferon gamma receptor 2 (IFN-γR2) and cytotoxic T cell-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (64). Acidic extracellular conditions reduce the expression of T-lymphocyte receptor components (65). Since the movement of lactate between the cytosol and the extracellular space depends on its concentration gradient, a high concentration of extracellular lactate in the TME prevents the export of lactate from T cells. This negatively affects the functions of activated T-lymphocytes dependent on glycolysis for ATP production (66). Notably, the functions of effector T- lymphocytes could be restored after normalization of pH (65–69), so the acidity does not have a cytotoxic effect. A significant effect of low acidity appears to be its negative effect on effector cytokines production by T cells, which is significantly reduced under acidic conditions (70–72). However, receptor interactions also play an important role. For example, in acidic TME, the V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), which is expressed by tumor-infiltrating myeloid suppressor cells, is activated and suppresses effector T cells (73). The inhibitory effect of acidic TME on dendritic cells is not related to the high concentration of H+, which actually stimulates antigen presentation (74). This inhibition can be explained by the accumulation of lactate, which modulates the dendritic cell phenotype and causes increased production of anti-inflammatory (e.g., IL-10) and decreased production of pro-inflammatory (e.g., IL-12) cytokines (75, 76). An acidic pHe and a high concentration of lactate together lead to a decrease in the activity of natural killers, including the depletion of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and their ability to infiltrate the tumor (71, 77, 78). At the same time, for example, an acidic environment stimulates regulatory T cells (Tregs) activity by involving lactic acid in metabolism (79). In addition, lactic acid promotes Tregs’ expression of programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) by absorption through monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1). Thus, the PD-1 blockade activates PD-1-rich Tregs, resulting in treatment failure (80). Besides this, the acidity of the TME upregulates programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in tumor cells (81).

It seems clear that the acidic conditions of the TME must be considered in monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anticancer therapy. On the one hand, slightly acidic conditions are probably optimal for most mAbs (82), i.e., acidity in solid tumors may only slightly influence the deterioration of the therapeutic properties of mAbs. On the other hand, the possibility of the degradation of mAbs under such conditions cannot be excluded (7). For example, the rate of antibody Fc fragment oxidation and aggregation, which determines antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), has been shown to increase with decreasing pH (83, 84). Despite the fact that cancer immunotherapy uses immune checkpoint-blocking mAbs that are specifically modified to eliminate interactions with Fc receptors, fatal changes in other parts of mAbs that determine their activity are also possible at low pH values. For example, the chemical degradation of aspartic acid induced by acidic pH in the complementarity-determining region (CDR) of a monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) causes a loss of antibody-binding activity (85). The high structural and physicochemical affinity of mAbs to their targets is a condition for achieving a therapeutic effect. In particular, histidine residues in interacting sites can increase pH-mediated dissociation due to protonation under acidic conditions, favoring electrostatic repulsion between rigid domains in protein–protein interaction (86). The low pHe can also greatly affect the bioavailability of therapeutic mAbs. At the same time, the “useful” side of acidic TME is the possibility of creating therapeutic pH-selective mAbs (87, 88).

Tumor acidity as a target of treatment

Tumor-targeted pH-sensitive antibodies should be screened for low pH activity, and antibody engineering should not be limited to finding molecules with activity over a wide pH range (87). For example, despite the pH-independent affinity of CTLA-4 for ipilimumab, an analog was developed with up to a 50-fold affinity for CTLA-4 at pH 6.0 compared to pH 7.4 (89). A bispecific pH-responsive anticarcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule (CEACAM) 5 antibody that binds pH-independently to CEACAM6 was generated (88). Likewise, acidic TME allows for pH-activated molecular targets, such as VISTA. A combination of anti-VISTA mAb with anti-PD-L1 therapy demonstrated a significant survival benefit in tumor-bearing mice (90). Nanotechnologies also provide a good tool for creating pH-responsible anticancer drugs based on pH-responsible polymer nanomaterials, nanogels, etc. (91, 92). It has recently been summarized that several types of pH-sensitive nanoparticle conjugates with paclitaxel, doxorubicin, or others enhance drug delivery and potentiate anticancer effects in various experimental cancer cell lines (93).

Another approach to influencing tumor aggressiveness and/or therapeutic response is the regulation of tumor pH levels. First, since glycolysis is the main source of lactate and H+, would it be possible to reduce lactate production by limiting glucose? Also considering that hyperglycemia is known to be associated with reduced survival rates in some types of cancer (94–97), although this is still controversial, for example, in pancreatic (98–100) or colorectal cancers (101–103). Indeed, glucose restriction can reverse the Warburg effect and decrease lactate production in vitro (104). However, cancer cells can also use glycogenolysis, glycogen synthesis, and gluconeogenesis to compensate for glucose starvation (105–107). Many therapies targeting glucose metabolism (e.g., targeting glucose transporters, glycogen phosphorylase, glycogen synthase kinase 3β, hexokinase 2, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, etc.) have been developed, but have not yet been successful in clinical trials (107). Furthermore, glycolysis is the main metabolic pathway of neutrophils, M1 macrophages, dendritic cells, naive T cells, effector T cells, etc. (108). For example, glucose-deficient TME limits the anaerobic glycolysis of tumor-infiltrating T cells and thus suppresses tumor-killing effects (109). Nutritional deficiencies in the TME, especially glucose, impair the metabolism of NK cells and their antitumor activity (110). It is important to note that human glucose levels may be reduced to very low levels without causing harm (111), and ketone bodies can be used for energy production with benefits for the organism (112, 113). For instance, a ketogenic diet improves the function of T cells (114, 115) and possibly creates an unfavorable metabolic environment for cancer cells (116, 117). However, ketone bodies utilization or formation may be a promoter for tumor cells proliferation and metastasis (118–121). Therefore, limiting glucose or its metabolism to reduce lactate production can have a completely ambiguous effect.

A more optimal way to reduce lactate production seems to be the inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA). This approach provides the simultaneous restriction of lactate synthesis from both glycolysis and glutaminolysis. Indeed, the inhibition of LDHA in vivo redirects pyruvate to support OXPHOS (122, 123). To date, a large number of LDHA inhibitors have been studied preclinically, but unfortunately, the clinical utility of such inhibitors may be limited due to nonselective toxicity or complex interactions with other cellular components. Optimization of existing compounds and continued search and development of new LDHA inhibitors will be reasonable strategies to obtain direct antitumor effects or enhance, for example, immunotherapy results (48, 124, 125). For example, since the effect of immunotherapy can be prevented by lactate (79, 80) and high LDH levels before treatment are correlated with a poor response to immunotherapy (126, 127), inhibition of LDHA can improve the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy (128).

Alternate modality to regulate tumor acidity is the pharmacological inhibition of proteins responsible for regulating pHi or mitochondrial activity (5, 9, 10). For example, inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate transporter (MPC) works to block lactate utilization while preventing oxidative glucose metabolism (129). Blocking the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) (used to import lactate as an energy source in oxidative cancer cells) with the specific MCT1 inhibitor AZD3965 prevents lactate consumption, increases its concentration in the TME, and has an antiproliferative effect (130–132). Conversely, the inhibition of MCT4 (expressed to remove lactate in glycolytic tumor cells) causes intracellular lactate accumulation, a decrease in pHi, but also reduces tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (132, 133). The cooperative use of MCT1/MCT4 inhibitors or nonspecific MCT inhibitors has good therapeutic potential (125, 132, 134, 135). Also of great importance to decrease pHi values is the pharmacological inhibition of the proton pump H+-ATPase (136), sodium-hydrogen antiporter 1 (NHE1) (137), and carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) (138). For example, according to the results of a phase III clinical trial (NCT01069081), intermittent use of a high dose of the proton pump inhibitor esomeprazole potentiates the effects of docetaxel and cisplatin chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer without causing further toxicity (139). In a retrospective study, omeprazole was found to have a synergistic effect with chemoradiotherapy and to significantly reduce the risk of rectal cancer recurrence (140). Other ion exchangers and transporters are involved in tumor pH regulation, but their role in cancer progression remains unclear (2).

Another way to affect tumor acidity is the use of buffer systems, such as sodium bicarbonate. Preclinical and some clinical studies suggest that “direct” tumor deacidification may slow progression or improve therapeutic response (34). Oral administration of sodium bicarbonate can increase the efficacy of doxorubicin and mitoxantrone in model experiments (52, 55). Furthermore, peroral administration of sodium bicarbonate and other buffer solutions significantly reduced the invasion and metastasis of various experimental (including spontaneous) tumors in genetically modified animals but had no effect on the growth of primary tumors (141–146). Neutralization of tumor acidity improved the antitumor response to anti-CTLA-4 and PD-1 mAbs, as well as the adoptive transfer of T-lymphocytes in experiments using the B16 melanoma model and Panc02 pancreatic cancer in mice (69).

At the same time, the first three clinical trials of oral sodium bicarbonate (NCT01350583, NCT01198821, NCT01846429) to improve outcomes and reduce pain in pancreatic adenocarcinoma failed due to poor taste sensation and gastrointestinal disturbances, resulting in bad compliance (147). However, a recent clinical study successfully examined the effect of alkalinization therapy (an alkaline diet supplemented with oral sodium bicarbonate) in combination with chemotherapy on the survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (UMIN 000035659). The median overall survival rate in patients whose urine pH became high (>7.0) after the start of therapy was significantly greater than in patients with low urine pH (≤7.0) (16.1 vs 4.7 months; p<0.05) (14). In another study (UMIN000043056), the combination of alkalinization therapy with intravenous vitamin C was also associated with favorable outcomes in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) receiving chemotherapy. The median overall survival for the intervention group was 44.2 months vs. 17.7 months for the control group (15).

Parenteral administration of buffer systems to directly neutralize tumor acidity is also of great importance, but it must be done under the close supervision of medical personnel and can have some serious side effects (148). The use of nanoobjects to deliver buffers due to the enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR) can overcome such limitations (149). For example, the administration of sodium bicarbonate-loaded liposomes in combination with subtherapeutic doses of doxorubicin in mice with triple-negative breast cancer resulted in a superior therapeutic response compared to drug administration alone (150). Performing an isolated infusion or perfusion of the tumor with buffer solutions is another option. In the ChiCTR-IOR-14005319 clinical study, the efficacies of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) with or without local administration of 5% sodium bicarbonate solution in patients with large-focal hepatocellular carcinoma were compared. In the case of sodium bicarbonate, the objective response rate (ORR) was 100% vs. 44.4% in the case of conventional TACE in a nonrandomized cohort and 63.6% in a randomized study (151). In a preclinical study, it was found that intraperitoneal perfusion with 1% sodium bicarbonate solution significantly prolonged overall survival in mice with the ascitic form of Ehrlich’s adenocarcinoma (median survival, 24 vs. 17 days; p < 0.05) when compared to 0.9% sodium chloride solution (18). In another study, perfusion was performed with a 4% sodium bicarbonate solution of rat limbs with a Pliss lymphosarcoma graft. The median survival in the sodium bicarbonate group was 17 days, while in the nonperfused group and in the isotonic saline group it was 13 days (17).

The mechanisms of the anticancer effects of alkalization (buffering) therapy remain unclear. While the improved chemotherapeutic effect can be explained by “ion trapping” (53, 54), the antitumor, antimetastatic, and immunotherapy-enhancing effects of buffered therapy may be much more complex and have been studied predominantly as a phenomenon until now. Buffering of the TME can reduce the optimal conditions for enzymes involved in tumor invasion, such as cathepsins and matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) (152). Neutralization of acidity in the TME can result in a reduction of PD-L1 expression, which is increased at low pH through proton-sensing G protein-coupled receptors (81). Neutralization of lactic acid with sodium bicarbonate reactivates metabolically altered (in an acid environment) T cells, enabling extracellular lactate as an additional source for their energy production (153). More research is needed on the mechanisms of the effectiveness of sodium bicarbonate and other buffer solutions in cancer patients. Alkalization (buffering) therapy does not conflict with standard treatment methods but can be used in combination to increase effectiveness (154).

Conclusion

Despite extensive studies on the acid-base status of malignant tumors over the past decades, the mechanisms of tumor adaptation to acidity, induction of invasion and metastasis, and the mechanisms leading to evasion of immune surveillance are still poorly understood. Further research in this direction is needed, including the development of approaches and drugs that directly or indirectly increase the pH of the TME for use in conjunction with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy. However, it is clear that clinical options already exist to counteract tumor acidosis in patients. Additionally, the selectivity of acidosis in tumors versus healthy tissues holds promise for pH-activated or pH-targeted drugs, which are safer than traditional chemotherapy and are applicable to more cancers than many targeted drugs. Regardless of the complexity of the clinical assessment of the TME acidity, clinicians should consider acidosis in practice, and the continued development of methods for clinical assessment of tumor pH should allow for accurate diagnosis and selection of personalized treatment regimens.

Author contributions

AlB and VM contributed to the conception of the mini-review. AlB and AnB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Committee of Saint Petersburg state assignment for Saint Petersburg Clinical Research and Practical Center of Specialized Types of Medical Care (Oncological).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Corbet C, Feron O. Tumour acidosis: From the passenger to the driver’s seat. Nat Rev Cancer (2017) 17(10):577–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ward C, Meehan J, Gray ME, Murray AF, Argyle DJ, Kunkler IH, et al. The impact of tumour ph on cancer progression: Strategies for clinical intervention. Explor Targeted Anti-tumor Ther (2020) 1(2):71–100. doi: 10.37349/etat.2020.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science (1956) 123(3191):309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaupel P, Multhoff G. Revisiting the warburg effect: historical dogma versus current understanding. J Physiol (2021) 599(6):1745–57. doi: 10.1113/JP278810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Persi E, Duran-Frigola M, Damaghi M, Roush WR, Aloy P, Cleveland JL, et al. Systems analysis of intracellular ph vulnerabilities for cancer therapy. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):2997. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05261-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng T, Jäättelä M, Liu B. Ph gradient reversal fuels cancer progression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2020) 125:105796. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2020.105796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huber V, Camisaschi C, Berzi A, Ferro S, Lugini L, Triulzi T, et al. Cancer acidity: An ultimate frontier of tumor immune escape and a novel target of immunomodulation. Semin Cancer Biol (2017) 43:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Omran Z, Scaife P, Stewart S, Rauch C. Physical and biological characteristics of multi drug resistance (mdr): An integral approach considering ph and drug resistance in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol (2017) 43:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harguindey S, Stanciu D, Devesa J, Alfarouk K, Cardone RA, Polo Orozco JD, et al. Cellular acidification as a new approach to cancer treatment and to the understanding and therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Semin Cancer Biol (2017) 43:157–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koltai T. Triple-edged therapy targeting intracellular alkalosis and extracellular acidosis in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol (2017) 43:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Du J-Z, Li H-J, Wang J. Tumor-acidity-cleavable maleic acid amide (tacmaa): A powerful tool for designing smart nanoparticles to overcome delivery barriers in cancer nanomedicine. Accounts Chem Res (2018) 51(11):2848–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gong Z, Liu X, Zhou B, Wang G, Guan X, Xu Y, et al. Tumor acidic microenvironment-induced drug release of rgd peptide nanoparticles for cellular uptake and cancer therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces (2021) 202:111673. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peng S, Xiao F, Chen M, Gao H. Tumor-microenvironment-responsive nanomedicine for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Adv Sci (2022) 9(1):2103836. doi: 10.1002/advs.202103836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamaguchi REO, Narui R, Wada H. Effects of alkalization therapy on chemotherapy outcomes in metastatic or recurrent pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res (2020) 40(2):873. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamaguchi R, Narui R, Morikawa H, Wada H. Improved chemotherapy outcomes of patients with small-cell lung cancer treated with combined alkalization therapy and intravenous vitamin C. Cancer Diagn Progn (2021) 1(3):157–63. doi: 10.21873/cdp.10021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ando H, Emam SE, Kawaguchi Y, Shimizu T, Ishima Y, Eshima K, et al. Increasing tumor extracellular ph by an oral alkalinizing agent improves antitumor responses of anti-pd-1 antibody: Implication of relationships between serum bicarbonate concentrations, urinary ph, and therapeutic outcomes. Biol Pharm Bull (2021) 44(6):844–52. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b21-00076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bogdanov AA, Egorenkov VV, Volkov NM, Moiseenko FV, Molchanov MS, Verlov NA, et al. Antitumor efficacy of an isolated hind legperfusion with a ph-increased solution in thepliss’ lymphosarcoma graft rat model. Almanac Clin Med (2021) 49(8):541–9. doi: 10.18786/2072-0505-2021-49-070541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bogdanov AA, Verlov NA, Knyazev NA, Klimenko VV, Bogdanov AA, Moiseyenko VM. 46p intraperitoneal perfusion with sodium bicarbonate solution can significantly increase the lifespan of mice with ehrlich ascites carcinoma. Ann Oncol (2021) 32:S374–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gillies RJ, Brown JS, Anderson ARA, Gatenby RA. Eco-evolutionary causes and consequences of temporal changes in intratumoural blood flow. Nat Rev Cancer (2018) 18(9):576–85. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0030-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonald PC, Chafe SC, Dedhar S. Overcoming hypoxia-mediated tumor progression: Combinatorial approaches targeting ph regulation, angiogenesis and immune dysfunction. Front Cell Dev Biol (2016) 4:27. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Webb BA, Chimenti M, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Dysregulated ph: A perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer (2011) 11(9):671–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc3110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Damiani C, Colombo R, Gaglio D, Mastroianni F, Pescini D, Westerhoff HV, et al. A metabolic core model elucidates how enhanced utilization of glucose and glutamine, with enhanced glutamine-dependent lactate production, promotes cancer cell growth: The warburq effect. PloS Comput Biol (2017) 13(9):e1005758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: Transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2007) 104(49):19345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu L, Zhu X, Wu Y. Effects of glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and glutamine metabolism on tumor microenvironment and clinical implications. Biomolecules (2022) 12(4):580. doi: 10.3390/biom12040580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pérez-Escuredo J, Dadhich RK, Dhup S, Cacace A, Van Hée VF, De Saedeleer CJ, et al. Lactate promotes glutamine uptake and metabolism in oxidative cancer cells. Cell Cycle (2016) 15(1):72–83. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1120930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoo HC, Yu YC, Sung Y, Han JM. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp Mol Med (2020) 52(9):1496–516. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00504-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lagadic-Gossmann D, Huc L, Lecureur V. Alterations of intracellular ph homeostasis in apoptosis: origins and roles. Cell Death Differ (2004) 11(9):953–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koltai T. Cancer: Fundamentals behind ph targeting and the double-edged approach. Onco Targets Ther (2016) 9:6343–60. doi: 10.2147/ott.S115438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spugnini EP, Sonveaux P, Stock C, Perez-Sayans M, De Milito A, Avnet S, et al. Proton channels and exchangers in cancer. biochimica et biophysica acta (BBA). Biomembranes (2015) 1848(10, Part B):2715–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Man CH, Mercier FE, Liu N, Dong W, Stephanopoulos G, Jiang L, et al. Proton export alkalinizes intracellular ph and reprograms carbon metabolism to drive normal and malignant cell growth. Blood (2022) 139(4):502–22. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Damaghi M, Wojtkowiak J, Gillies R. Ph sensing and regulation in cancer. Front Physiol (2013) 4:370. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Becker HM, Deitmer JW. Transport metabolons and acid/base balance in tumor cells. Cancers (2020) 12(4):899. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (2009) 324(5930):1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pillai SR, Damaghi M, Marunaka Y, Spugnini EP, Fais S, Gillies RJ. Causes, consequences, and therapy of tumors acidosis. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2019) 38(1-2):205–22. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09792-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sharma M, Astekar M, Soi S, Manjunatha BS, Shetty DC, Radhakrishnan R. Ph gradient reversal: An emerging hallmark of cancers. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discovery (2015) 10(3):244–58. doi: 10.2174/1574892810666150708110608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blaszczak W, Swietach P. What do cellular responses to acidity tell us about cancer? Cancer Metastasis Rev (2021) 40(4):1159–76. doi: 10.1007/s10555-021-10005-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andreucci E, Peppicelli S, Ruzzolini J, Bianchini F, Biagioni A, Papucci L, et al. The acidic tumor microenvironment drives a stem-like phenotype in melanoma cells. J Mol Med (2020) 98(10):1431–46. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-01959-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kazyken D, Lentz SI, Fingar DC. Alkaline intracellular ph (phi) activates ampk–mtorc2 signaling to promote cell survival during growth factor limitation. J Biol Chem (2021) 297(4):101100. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yao J, Czaplinska D, Ialchina R, Schnipper J, Liu B, Sandelin A, et al. Cancer cell acid adaptation gene expression response is correlated to tumor-specific tissue expression profiles and patient survival. Cancers (2020) 12(8):2183. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang JX, Choi SYC, Niu X, Kang N, Xue H, Killam J, et al. Lactic acid and an acidic tumor microenvironment suppress anticancer immunity. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(21):8363. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peppicelli S, Andreucci E, Ruzzolini J, Laurenzana A, Margheri F, Fibbi G, et al. The acidic microenvironment as a possible niche of dormant tumor cells. Cell Mol Life Sci (2017) 74(15):2761–71. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2496-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anemone A, Consolino L, Arena F, Capozza M, Longo DL. Imaging tumor acidosis: A survey of the available techniques for mapping in vivo tumor ph. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2019) 38(1-2):25–49. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09782-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coman D, Peters DC, Walsh JJ, Savic LJ, Huber S, Sinusas AJ, et al. Extracellular ph mapping of liver cancer on a clinical 3t mri scanner. Magn Reson Med (2020) 83(5):1553–64. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Anemone A, Consolino L, Conti L, Irrera P, Hsu MY, Villano D, et al. Tumour acidosis evaluated in vivo by mri-cest ph imaging reveals breast cancer metastatic potential. Br J Cancer (2021) 124(1):207–16. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01173-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones KM, Randtke EA, Yoshimaru ES, Howison CM, Chalasani P, Klein RR, et al. Clinical translation of tumor acidosis measurements with acidocest mri. Mol Imaging Biol (2017) 19(4):617–25. doi: 10.1007/s11307-016-1029-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tang Y, Xiao G, Shen Z, Zhuang C, Xie Y, Zhang X, et al. Noninvasive detection of extracellular ph in human benign and malignant liver tumors using cest mri. Front Oncol (2020) 10:578985. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.578985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Al-Kindi SG, Sarode A, Zullo M, Rajagopalan S, Rahman M, Hostetter T, et al. Serum bicarbonate concentration and cause-specific mortality: The national health and nutrition examination survey 1999-2010. Mayo Clin Proc (2020) 95(1):113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.05.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de la Cruz-López KG, Castro-Muñoz LJ, Reyes-Hernández DO, García-Carrancá A, Manzo-Merino J. Lactate in the regulation of tumor microenvironment and therapeutic approaches. Front Oncol (2019) 9:1143. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brown JM, Wilson WR. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer (2004) 4(6):437–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suwa T, Kobayashi M, Nam J-M, Harada H. Tumor microenvironment and radioresistance. Exp Mol Med (2021) 53(6):1029–35. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00640-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bristow RG, Hill RP. Hypoxia and metabolism. hypoxia, dna repair and genetic instability. Nat Rev Cancer (2008) 8(3):180–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mahoney BP, Raghunand N, Baggett B, Gillies RJ. Tumor acidity, ion trapping and chemotherapeutics. i. acid ph affects the distribution of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro . Biochem Pharmacol (2003) 66(7):1207–18. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00467-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gerweck LE, Vijayappa S, Kozin S. Tumor ph controls the in vivo efficacy of weak acid and base chemotherapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther (2006) 5(5):1275–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-06-0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trédan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer inst (2007) 99(19):1441–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Raghunand N, Mahoney BP, Gillies RJ. Tumor acidity, ion trapping and chemotherapeutics. ii. ph-dependent partition coefficients predict importance of ion trapping on pharmacokinetics of weakly basic chemotherapeutic agents. Biochem Pharmacol (2003) 66(7):1219–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00468-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vukovic V, Tannock IF. Influence of low ph on cytotoxicity of paclitaxel, mitoxantrone and topotecan. Br J Cancer (1997) 75(8):1167–72. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sauvant C, Nowak M, Wirth C, Schneider B, Riemann A, Gekle M, et al. Acidosis induces multi-drug resistance in rat prostate cancer cells (at1) in vitro and in vivo by increasing the activity of the p-glycoprotein via activation of p38. Int J Cancer (2008) 123(11):2532–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thews O, Gassner B, Kelleher DK, Schwerdt G, Gekle M. Impact of extracellular acidity on the activity of p-glycoprotein and the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs. Neoplasia (2006) 8(2):143–52. doi: 10.1593/neo.05697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thews O, Nowak M, Sauvant C, Gekle M. Hypoxia-induced extracellular acidosis increases p-glycoprotein activity and chemoresistance in tumorsin vivo via p38 signaling pathway. Adv Exp Med Biol (2011) 701:115–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7756-4_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hu P-S, Li T, Lin J-F, Qiu M-Z, Wang D-S, Liu Z-X, et al. Vdr-sox2 signaling promotes colorectal cancer stemness and malignancy in an acidic microenvironment. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2020) 5(1):183–. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00230-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barnes EME, Xu Y, Benito A, Herendi L, Siskos AP, Aboagye EO, et al. Lactic acidosis induces resistance to the pan-akt inhibitor uprosertib in colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer (2020) 122(9):1298–308. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0777-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Worsley CM, Veale RB, Mayne ES. The acidic tumour microenvironment: Manipulating the immune response to elicit escape. Hum Immunol (2022) 83(5):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2022.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huntington KE, Louie A, Zhou L, Seyhan AA, Maxwell AW, El-Deiry WS. Colorectal cancer extracellular acidosis decreases immune cell killing and is partially ameliorated by ph-modulating agents that modify tumor cell cytokine profiles. Am J Cancer Res (2022) 12(1):138–51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bosticardo M, Ariotti S, Losana G, Bernabei P, Forni G, Novelli F. Biased activation of human t lymphocytes due to low extracellular ph is antagonized by b7/cd28 costimulation. Eur J Immunol (2001) 31(9):2829–38. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Calcinotto A, Filipazzi P, Grioni M, Iero M, De Milito A, Ricupito A, et al. Modulation of microenvironment acidity reverses anergy in human and murine tumor-infiltrating t lymphocytes. Cancer Res (2012) 72(11):2746–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-11-1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S, Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, et al. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human t cells. Blood (2007) 109(9):3812–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nakagawa Y, Negishi Y, Shimizu M, Takahashi M, Ichikawa M, Takahashi H. Effects of extracellular ph and hypoxia on the function and development of antigen-specific cytotoxic t lymphocytes. Immunol Lett (2015) 167(2):72–86. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mendler AN, Hu B, Prinz PU, Kreutz M, Gottfried E, Noessner E. Tumor lactic acidosis suppresses ctl function by inhibition of p38 and jnk/c-jun activation. Int J Cancer (2012) 131(3):633–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pilon-Thomas S, Kodumudi KN, El-Kenawi AE, Russell S, Weber AM, Luddy K, et al. Neutralization of tumor acidity improves antitumor responses to immunotherapy. Cancer Res (2016) 76(6):1381–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, Nadkarni S, Montero-Melendez T, D’Acquisto F, et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and pro-inflammatory circuits in control of t cell migration and effector functions. PloS Biol (2015) 13(7):e1002202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M, Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, et al. Ldha-associated lactic acid production blunts tumor immunosurveillance by t and nk cells. Cell Metab (2016) 24(5):657–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wu H, Estrella V, Beatty M, Abrahams D, El-Kenawi A, Russell S, et al. T-Cells produce acidic niches in lymph nodes to suppress their own effector functions. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):4113. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17756-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Johnston RJ, Su LJ, Pinckney J, Critton D, Boyer E, Krishnakumar A, et al. Vista is an acidic ph-selective ligand for psgl-1. Nature (2019) 574(7779):565–70. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1674-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vermeulen M, Giordano M, Trevani AS, Sedlik C, Gamberale R, Fernández-Calotti P, et al. Acidosis improves uptake of antigens and mhc class i-restricted presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol (2004) 172(5):3196. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gottfried E, Kunz-Schughart LA, Ebner S, Mueller-Klieser W, Hoves S, Andreesen R, et al. Tumor-derived lactic acid modulates dendritic cell activation and antigen expression. Blood (2006) 107(5):2013–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nasi A, Fekete T, Krishnamurthy A, Snowden S, Rajnavölgyi E, Catrina AI, et al. Dendritic cell reprogramming by endogenously produced lactic acid. J Immunol (2013) 191(6):3090–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Loeffler DA, Juneau PL, Heppner GH. Natural killer-cell activity under conditions reflective of tumor micro-environment. Int J Cancer (1991) 48(6):895–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pötzl J, Roser D, Bankel L, Hömberg N, Geishauser A, Brenner CD, et al. Reversal of tumor acidosis by systemic buffering reactivates nk cells to express ifn-γ and induces nk cell-dependent lymphoma control without other immunotherapies. Int J Cancer (2017) 140(9):2125–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Watson MJ, Vignali PDA, Mullett SJ, Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Peralta RM, Grebinoski S, et al. Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory t cells by lactic acid. Nature (2021) 591(7851):645–51. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03045-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K, Tanegashima T, Y-t L, Togashi Y, et al. Lactic acid promotes pd-1 expression in regulatory t cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell (2022) 40(2):201–18.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mori D, Tsujikawa T, Sugiyama Y, Kotani SI, Fuse S, Ohmura G, et al. Extracellular acidity in tumor tissue upregulates programmed cell death protein 1 expression on tumor cells via proton-sensing g protein-coupled receptors. Int J Cancer (2021) 149(12):2116–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wang W, Singh S, Zeng DL, King K, Nema S. Antibody structure, instability, and formulation. J Pharm Sci (2007) 96(1):1–26. doi: 10.1002/jps.20727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Latypov RF, Hogan S, Lau H, Gadgil H, Liu D. Elucidation of acid-induced unfolding and aggregation of human immunoglobulin igg1 and igg2 fc. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(2):1381–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ishikawa T, Ito T, Endo R, Nakagawa K, Sawa E, Wakamatsu K. Influence of ph on heat-induced aggregation and degradation of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Biol Pharm Bull (2010) 33(8):1413–7. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wang T, Kumru OS, Yi L, Wang YJ, Zhang J, Kim JH, et al. Effect of ionic strength and ph on the physical and chemical stability of a monoclonal antibody antigen-binding fragment. J Pharm Sci (2013) 102(8):2520–37. doi: 10.1002/jps.23645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Watanabe H, Matsumaru H, Ooishi A, Feng Y, Odahara T, Suto K, et al. Optimizing ph response of affinity between protein g and igg fc: how electrostatic modulations affect protein-protein interactions. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(18):12373–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809236200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Klaus T, Deshmukh S. Ph-responsive antibodies for therapeutic applications. J BioMed Sci (2021) 28(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12929-021-00709-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bogen JP, Hinz SC, Grzeschik J, Ebenig A, Krah S, Zielonka S, et al. Dual function ph responsive bispecific antibodies for tumor targeting and antigen depletion in plasma. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1892. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lee PS, MacDonald KG, Massi E, Chew PV, Bee C, Perkins P, et al. Improved therapeutic index of an acidic ph-selective antibody. MAbs (2022) 14(1):2024642–. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2021.2024642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Liu J, Yuan Y, Chen W, Putra J, Suriawinata AA, Schenk AD, et al. Immune-checkpoint proteins vista and pd-1 nonredundantly regulate murine t-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2015) 112(21):6682–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420370112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chu S, Shi X, Tian Y, Gao F. Ph-responsive polymer nanomaterials for tumor therapy. Front Oncol (2022) 12:855019. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.855019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Li Z, Huang J, Wu J. Ph-sensitive nanogels for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Biomater Sci (2021) 9(3):574–89. doi: 10.1039/D0BM01729A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Morarasu S, Morarasu BC, Ghiarasim R, Coroaba A, Tiron C, Iliescu R, et al. Targeted cancer therapy Via ph-functionalized nanoparticles: A scoping review of methods and outcomes. Gels (2022) 8(4):232. doi: 10.3390/gels8040232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Villarreal-Garza C, Shaw-Dulin R, Lara-Medina F, Bacon L, Rivera D, Urzua L, et al. Impact of diabetes and hyperglycemia on survival in advanced breast cancer patients. Exp Diabetes Res (2012) 2012:732027. doi: 10.1155/2012/732027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Iarrobino NA, Gill BS, Bernard M, Klement RJ, Werner-Wasik M, Champ CE. The impact of serum glucose, anti-diabetic agents, and statin usage in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with definitive chemoradiation. Front Oncol (2018) 8:281. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Li W, Zhang X, Sang H, Zhou Y, Shang C, Wang Y, et al. Effects of hyperglycemia on the progression of tumor diseases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2019) 38(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1309-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ramteke P, Deb A, Shepal V, Bhat MK. Hyperglycemia associated metabolic and molecular alterations in cancer risk, progression, treatment, and mortality. Cancers (2019) 11(9):1402. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhang M, Hu X, Kang Y, Xu W, Yang X. Association between fasting blood glucose levels at admission and overall survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer (2021) 21(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07859-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wang X, Xu W, Hu X, Yang X, Zhang M. The prognostic role of glycemia in patients with pancreatic carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol (2022) 12:780909. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.780909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhang P, Xiao Z, Xu H, Zhu X, Wang L, Huang D, et al. Hyperglycemia is associated with adverse prognosis in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine (2022) 77(2):262–71. doi: 10.1007/s12020-022-03100-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Cui G, Zhang T, Ren F, Feng WM, Yao Y, Cui J, et al. High blood glucose levels correlate with tumor malignancy in colorectal cancer patients. Med Sci Monit (2015) 21:3825–33. doi: 10.12659/msm.894783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lee SJ, Kim JH, Park SJ, Ock SY, Kwon SK, Choi YS, et al. Optimal glycemic target level for colon cancer patients with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2017) 124:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yang IP, Miao ZF, Huang CW, Tsai HL, Yeh YS, Su WC, et al. High blood sugar levels but not diabetes mellitus significantly enhance oxaliplatin chemoresistance in patients with stage iii colorectal cancer receiving adjuvant folfox6 chemotherapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol (2019) 11:1758835919866964. doi: 10.1177/1758835919866964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tahtouh R, Wardi L, Sarkis R, Hachem R, Raad I, El Zein N, et al. Glucose restriction reverses the warburg effect and modulates pkm2 and mtor expression in breast cancer cell lines. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) (2019) 65(7):26–33. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2019.65.7.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Khan T, Sullivan MA, Gunter JH, Kryza T, Lyons N, He Y, et al. Revisiting glycogen in cancer: A conspicuous and targetable enabler of malignant transformation. Front Oncol (2020) 10:592455. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.592455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Grasmann G, Smolle E, Olschewski H, Leithner K. Gluconeogenesis in cancer cells - repurposing of a starvation-induced metabolic pathway? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer (2019) 1872(1):24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Bose S, Zhang C, Le A. Glucose metabolism in cancer: The warburg effect and beyond. In: Le A, editor. The heterogeneity of cancer metabolism. Cham: Springer International Publishing; (2021). p. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Pearce EL, Poffenberger MC, Chang CH, Jones RG. Fueling immunity: Insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science (2013) 342(6155):1242454. doi: 10.1126/science.1242454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Cao Y, Rathmell JC, Macintyre AN. Metabolic reprogramming towards aerobic glycolysis correlates with greater proliferative ability and resistance to metabolic inhibition in cd8 versus cd4 t cells. PloS One (2014) 9(8):e104104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Cong J, Wang X, Zheng X, Wang D, Fu B, Sun R, et al. Dysfunction of natural killer cells by fbp1-induced inhibition of glycolysis during lung cancer progression. Cell Metab (2018) 28(2):243–55.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Drenick EJ, Alvarez LC, Tamasi GC, Brickman AS. Resistance to symptomatic insulin reactions after fasting. J Clin Invest (1972) 51(10):2757–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI107095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Kolb H, Kempf K, Röhling M, Lenzen-Schulte M, Schloot NC, Martin S. Ketone bodies: From enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med (2021) 19(1):313. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Puchalska P, Crawford PA. Multi-dimensional roles of ketone bodies in fuel metabolism, signaling, and therapeutics. Cell Metab (2017) 25(2):262–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hirschberger S, Gellert L, Effinger D, Muenchhoff M, Herrmann M, Briegel J-M, et al. Ketone bodies improve human cd8+ cytotoxic t-cell immune response during covid-19 infection. Front Med (2022) 9:923502. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.923502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hirschberger S, Strauß G, Effinger D, Marstaller X, Ferstl A, Müller MB, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate diet enhances human t-cell immunity through immunometabolic reprogramming. EMBO Mol Med (2021) 13(8):e14323. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Weber DD, Aminzadeh-Gohari S, Tulipan J, Catalano L, Feichtinger RG, Kofler B. Ketogenic diet in the treatment of cancer - where do we stand? Mol Metab (2020) 33:102–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ferrere G, Tidjani Alou M, Liu P, Goubet A-G, Fidelle M, Kepp O, et al. Ketogenic diet and ketone bodies enhance the anticancer effects of pd-1 blockade. JCI Insight (2021) 6(2):e145207. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.145207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Ketone body utilization drives tumor growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle (2012) 11(21):3964–71. doi: 10.4161/cc.22137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Ketone bodies and two-compartment tumor metabolism: Stromal ketone production fuels mitochondrial biogenesis in epithelial cancer cells. Cell Cycle (2012) 11(21):3956–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.22136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Gouirand V, Gicquel T, Lien EC, Jaune-Pons E, Da Costa Q, Finetti P, et al. Ketogenic hmg-coa lyase and its product β-hydroxybutyrate promote pancreatic cancer progression. EMBO J (2022) 41(9):e110466. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021110466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Sperry J, Condro MC, Guo L, Braas D, Vanderveer-Harris N, Kim KKO, et al. Glioblastoma utilizes fatty acids and ketone bodies for growth allowing progression during ketogenic diet therapy. iScience (2020) 23(9):101453. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Oshima N, Ishida R, Kishimoto S, Beebe K, Brender JR, Yamamoto K, et al. Dynamic imaging of ldh inhibition in tumors reveals rapid in vivo metabolic rewiring and vulnerability to combination therapy. Cell Rep (2020) 30(6):1798–810.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Yeung C, Gibson AE, Issaq SH, Oshima N, Baumgart JT, Edessa LD, et al. Targeting glycolysis through inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase impairs tumor growth in preclinical models of ewing sarcoma. Cancer Res (2019) 79(19):5060–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Pérez-Tomás R, Pérez-Guillén I. Lactate in the tumor microenvironment: An essential molecule in cancer progression and treatment. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12(11):3244. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Wang Z-H, Peng W-B, Zhang P, Yang X-P, Zhou Q. Lactate in the tumour microenvironment: From immune modulation to therapy. eBioMedicine (2021) 73:103627. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Zhang Z, Li Y, Yan X, Song Q, Wang G, Hu Y, et al. Pretreatment lactate dehydrogenase may predict outcome of advanced non small-cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Cancer Med (2019) 8(4):1467–73. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhao L, Liu Y, Zhang S, Wei L, Cheng H, Wang J, et al. Impacts and mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming of tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis (2022) 13(4):378. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04821-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Qiao T, Xiong Y, Feng Y, Guo W, Zhou Y, Zhao J, et al. Inhibition of ldh-a by oxamate enhances the efficacy of anti-Pd-1 treatment in an nsclc humanized mouse model. Front Oncol (2021) 11:632364. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.632364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Corbet C, Bastien E, Draoui N, Doix B, Mignion L, Jordan BF, et al. Interruption of lactate uptake by inhibiting mitochondrial pyruvate transport unravels direct antitumor and radiosensitizing effects. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1208. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Silva A, Antunes B, Batista A, Pinto-Ribeiro F, Baltazar F, Afonso J. In vivo anticancer activity of azd3965: A systematic review. Molecules (2021) 27(1):181. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Guan X, Morris ME. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of azd3965 and alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in the murine 4t1 breast tumor model. AAPS J (2020) 22(4):84. doi: 10.1208/s12248-020-00466-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Payen VL, Mina E, Van Hée VF, Porporato PE, Sonveaux P. Monocarboxylate transporters in cancer. Mol Metab (2020) 33:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Todenhöfer T, Seiler R, Stewart C, Moskalev I, Gao J, Ladhar S, et al. Selective inhibition of the lactate transporter mct4 reduces growth of invasive bladder cancer. Mol Cancer Ther (2018) 17(12):2746–55. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-18-0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Puri S, Juvale K. Monocarboxylate transporter 1 and 4 inhibitors as potential therapeutics for treating solid tumours: A review with structure-activity relationship insights. Eur J Medicinal Chem (2020) 199:112393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Benjamin D, Robay D, Hindupur SK, Pohlmann J, Colombi M, El-Shemerly MY, et al. Dual inhibition of the lactate transporters mct1 and mct4 is synthetic lethal with metformin due to nad+ depletion in cancer cells. Cell Rep (2018) 25(11):3047–58.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Eaton AF, Merkulova M, Brown D. The h(+)-atpase (v-atpase): From proton pump to signaling complex in health and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (2021) 320(3):C392–c414. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00442.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Hu Y, Lou J, Jin Z, Yang X, Shan W, Du Q, et al. Advances in research on the regulatory mechanism of nhe1 in tumors (review). Oncol Lett (2021) 21(4):273. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. McDonald PC, Chafe SC, Supuran CT, Dedhar S. Cancer therapeutic targeting of hypoxia induced carbonic anhydrase ix: From bench to bedside. Cancers (2022) 14(14):3297. doi: 10.3390/cancers14143297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Wang BY, Zhang J, Wang JL, Sun S, Wang ZH, Wang LP, et al. Intermittent high dose proton pump inhibitor enhances the antitumor effects of chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2015) 34(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0194-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Zhang J-L, Liu M, Yang Q, Lin S-Y, Shan H-B, Wang H-Y, et al. Effects of omeprazole in improving concurrent chemoradiotherapy efficacy in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol (2017) 23(14):2575–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i14.2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Robey IF, Baggett BK, Kirkpatrick ND, Roe DJ, Dosescu J, Sloane BF, et al. Bicarbonate increases tumor ph and inhibits spontaneous metastases. Cancer Res (2009) 69(6):2260–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Ibrahim-Hashim A, Wojtkowiak JW, de Lourdes Coelho Ribeiro M, Estrella V, Bailey KM, Cornnell HH, et al. Free base lysine increases survival and reduces metastasis in prostate cancer model. J Cancer Sci Ther (2011) Suppl 1(4):JCST-S1-004. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.S1-004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Ibrahim-Hashim A, Robertson-Tessi M, Enriquez-Navas PM, Damaghi M, Balagurunathan Y, Wojtkowiak JW, et al. Defining cancer subpopulations by adaptive strategies rather than molecular properties provides novel insights into intratumoral evolution. Cancer Res (2017) 77(9):2242–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-16-2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Ibrahim-Hashim A, Cornnell HH, Abrahams D, Lloyd M, Bui M, Gillies RJ, et al. Systemic buffers inhibit carcinogenesis in tramp mice. J Urol (2012) 188(2):624–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.03.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Ibrahim Hashim A, Cornnell HH, Coelho Ribeiro Mde L, Abrahams D, Cunningham J, Lloyd M, et al. Reduction of metastasis using a non-volatile buffer. Clin Exp Metastasis (2011) 28(8):841–9. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9415-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Ibrahim-Hashim A, Abrahams D, Enriquez-Navas PM, Luddy K, Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Tris-base buffer: A promising new inhibitor for cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Med (2017) 6(7):1720–9. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Pilot C, Mahipal A, Gillies R. Buffer therapy–buffer diet. J Nutr Food Sci (2018) 8:1000685. doi: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Sarno J. Prevention and management of tumor lysis syndrome in adults with malignancy. J Adv Pract Oncol (2013) 4(2):101–6. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2013.4.2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM, Peer D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1410. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03705-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Abumanhal-Masarweh H, Koren L, Zinger A, Yaari Z, Krinsky N, Kaneti G, et al. Sodium bicarbonate nanoparticles modulate the tumor ph and enhance the cellular uptake of doxorubicin. J Control Release (2019) 296:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Chao M, Wu H, Jin K, Li B, Wu J, Zhang G, et al. A nonrandomized cohort and a randomized study of local control of large hepatocarcinoma by targeting intratumoral lactic acidosis. Elife (2016) 5:e15691. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Robey IF, Nesbit LA. Investigating mechanisms of alkalinization for reducing primary breast tumor invasion. BioMed Res Int (2013) 2013:485196. doi: 10.1155/2013/485196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Uhl FM, Chen S, O’Sullivan D, Edwards-Hicks J, Richter G, Haring E, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of donor t cells enhances graft-versus-leukemia effects in mice and humans. Sci Trans Med (2020) 12(567):eabb8969. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb8969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Wada H, Hamaguchi R, Narui R, Morikawa H. Meaning and significance of “alkalization therapy for cancer”. Front Oncol (2022) 12:920843. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.920843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]