Standfirst

During the COVID-19 pandemic, genomics and bioinformatics have emerged as essential public health tools. The genomic data acquired using these methods have supported the global health response, facilitated development of testing methods, and allowed timely tracking of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants. Yet the virtually unlimited potential for rapid generation and analysis of genomic data is also coupled with unique technical, scientific, and organizational challenges. Here, we discuss the application of genomic and computational methods for the efficient data driven COVID-19 response, advantages of democratization of viral sequencing around the world, and challenges associated with viral genome data collection and processing.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious pathogen that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, which reached an unprecedented scale of infection not seen since the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919. Within a month of its first reported case in Wuhan, China in December 2019, the virus had spread to many regions within the country as well as in several neighboring countries, including Thailand, Korea, and Japan. As international flights continued to operate, SARS-CoV-2 rapidly spread to Europe and North America1.

During this time, it became clear that the genomic toolkits are essential for public health decision making, including testing for COVID-19, monitoring for emergence of new virus variants with altered biological or immunological properties, identification of at-risk individuals and informing epidemiological models that describe outbreaks in communities2. This has allowed for the observation of SARS-CoV-2 genome evolution in almost real time, rapid tracking of SARS-CoV-2 genetic lineages, and variants of interest and concern (VOIs, VOCs) which in turn have facilitated the development of SARS-CoV-2 clinical tests and prediction of vaccines efficacy against viral variants3,4. However, to reach the full potential of genomic data for future public health surveillance and outbreak response, we believe it is necessary to expand and coordinate best practices in genomics and bioinformatics that have now been field tested during the COVID-19 response5. Herein, we discuss the genomic techniques and corresponding bioinformatics algorithms that are addressing many of the pressing public health issues associated with COVID-19.

Genomics-based methods enabled early warnings of COVID-19 pandemic

When a local team of health professionals was investigating a small local outbreak of pneumonia consisting of the first 59 suspected cases from Wuhan in December 2019, they quickly discovered that they were dealing with a novel virus of unknown origin6. This rapid discovery was made possible by modern robust and accurate genomic and bioinformatic tools, which while now used routinely, did not exist a couple of decades ago. On January 30, 2020, when WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) 339 SARS-CoV-2 genomes had already been sequenced and characterized1.

To investigate the newly emerging outbreak, scientists in China performed whole-genome sequencing on specimens, followed by de-novo assembly and end mapping to annotate the complete 29,903 nucleotides long SARS-CoV-2 genome. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that the genome organization of SARS-CoV-2 was consistent with single-stranded, positive-sense RNA from the genus Betacoronavirus7. Additionally, sequence alignment tools including BLAST8 were used to search for related species of the newly discovered virus in the NCBI GenBank database, revealing alarming similarities to SARS-CoV (SARS-CoV-1), and a much higher similarity with Betacoronavirus from bats, proposing zoonotic origin of the virus. Some SARS-CoV-2 genome fragments, in addition, have the highest similarity to the corresponding fragments from pangolins, which suggests that there were possible recombination events. Subsequent analyses including on additional sarbecovirus genomes from bats and pangolins further scrutinized the evolution and recombination history, and found that the lineage giving rise to SARS-CoV-2 had been probably circulating unnoticed in bats for decades9,10.

Genomics-based methods shaped the effective COVID-19 response

Once the SARS-CoV-2 genome was sequenced, the authors immediately publicly deposited the genome to GenBank7,11. Timely open access release of the virus genome sequence was a laudable decision that allowed informed scientific analyses and pandemic preparation to begin immediately.

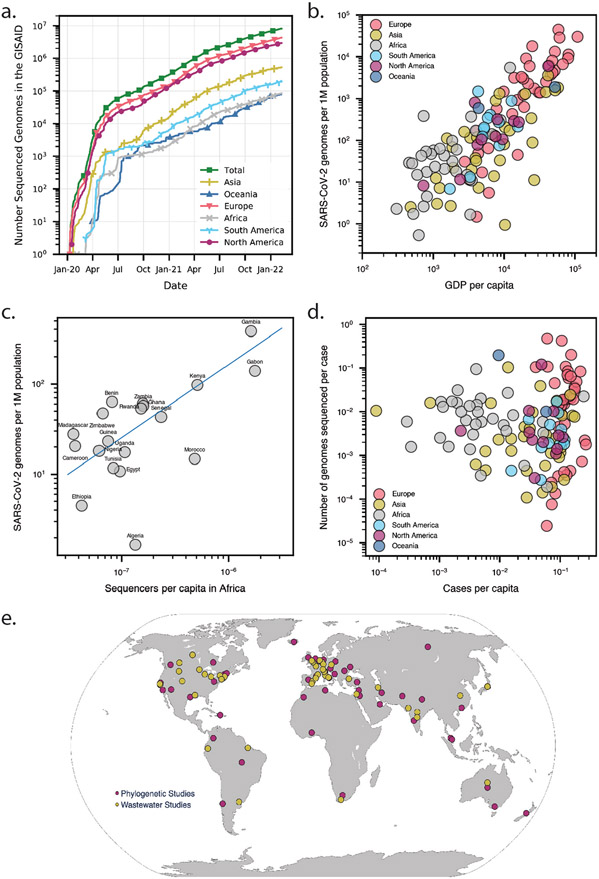

As the pandemic progressed, increased availability of modern sequencing technologies prompted the collection of SARS-CoV-2 viral genomic data at an unprecedented scale. Within a month, on average about 1,300 genomes were being submitted per day. Within six months of the pandemic (May 2020), GISAID had 110,000 SARS-CoV-2 full-length genome sequences. By December 2021, two years into the pandemic, 67,000 genomes per day were being deposited into public viral genome data repositories like GISAID, COG-UK, and GenBank, which currently contain over 6 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes12-14 (Figure 1a, Table S1). The unprecedented volume of data collection for SARS-CoV-2 is seen when contrasted with HIV genomic data collection. HIV that consistently captivated the attention of public health officials and the general public since 1980’s, has fewer than 16,000 full-length genome sequences collected by the biggest public HIV database at Los Alamos sequence National Laboratory over the past 40 years15 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Available SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequencing data and its usage for outbreak investigation.

(a) The number of SARS-CoV-2 genomes sequenced according to Global Initiative On Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) between January 2020 and December 2021. (b) The number of available SARS-CoV-2 sequences in GISAID per 1 million (1M) individuals for each country or region vs. the number of cases per capita up to March 2021. (c) The number of available SARS-CoV-2 sequences in GISAID per 1 million (1M) individuals for each country in Africa vs. the number of sequencers per capita up to March 2021. Blue line is the correlation of all data points on the plot. (d) The number of available SARS-CoV-2 sequences in GISAID per number of reported COVID-19 cases for each country or region vs. the number of reported COVID-19 cases per capita from December 2019 up to December 2021. (e) Global outbreak investigations by phylogenetic analysis (red) and wastewater studies (yellow), dots were placed in the geographical centers of each country or region.

Sequencing data collected all over the world and rapidly shared on online databases ultimately aided public health officials and governments in making better-informed decisions16. However, to fully explore the potential of such databases, there are a few issues which need to be solved. Despite the unprecedented pace overall, inevitable delays caused by shortage of sequencing capacity and political interference in some regions led to problems in the logistical chain in these regions, including in sample collection, transporting, and shipping samples17. Depending on the country and the strength of their public health infrastructure, the median collection to submission time lag differs, ranging from one day to one year. Several factors impact the rate and scale of viral genomic sequencing across the globe. Countries with minimal sequencing are likely to encounter outbreaks of higher severity, leading to blind spots of genomic surveillance that can facilitate the spread of new variants to other countries17. On average high-income countries shared about 100 times more sequences per capita than low-income countries (Figures 1b and S2). However, some African countries with a low GDP per capita were able to sequence a comparable number of viral genomes of middle- and high-income countries18. This preparedness can be attributed to previous global initiatives to support African countries in mitigating outbreaks of other viruses that has enhanced the sequencing capacity of the region. Africa provides a remarkable example of the necessity of international cooperation that could be implemented in other parts of the globe to improve pandemic response (Figure 1c). The number of shared coronavirus genomes per capita is correlated with the country's GDP per capita (Figure 1d).

Moving forward, several important data sharing issues need to be addressed to facilitate open and rapid viral genome data sharing. Scientists depositing sequencing data should trust that their rights will be respected by data users and that their authorship rights will not be violated19. For instance, GISAID data access mechanism proved its ability to overcome these obstacles to the international sharing of virus data, making GISAID the largest repository of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 genomic data16,20.

Bioinformatics methods are capable of accurately tracking SARS-CoV-2 genomic evolution

As SARS-CoV-2 has spread through the world population over the first year of the pandemic, it gradually evolved into several viral lineages21-24. Based on statistical analysis of collected SARS-CoV-2 genomes, it was shown that SARS-CoV-2 has a mutation rate of at least 10-fold lower than seasonal influenza25. The lower mutation rate initially gave hope for efficient control of the pandemic through vaccination because the slower the virus mutates, the less chances it has to adapt to vaccines. However, given the large number of COVID-19 cases (>277 million and climbing, according to WHO) and possibly because of SARS-CoV-2 recombination events, new variants continue to evolve, which are being classified as variant under investigation (VUI), of interest (VOI), and of concern (VOC) according to their epidemiological, biological and/or immunological properties. Indeed, some variants acquired numerous mutations in a rapid fashion (variants Alpha and Omicron) and showed evidence of immune escape (Omicron). Notably, it was observed that immunodeficient individuals with unusually long periods of SARS-CoV-2 infection can create a plausible environment for faster SARS-CoV-2 evolution because their immune system allows for viral immune escape26.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the public health community has had experience with tracking and responding to genome evolution for viruses such as the seasonal flu causing influenza viruses. The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) was established by WHO for timely collection, genetic and antigenic characterization of these viruses27. Sharing of virus sequence data in the GISAID database along with Nextstrain28 online phylogenetic tool was utilized for biannual influenza A and B vaccine seed strain selection and understanding viral genomic evolution and antigenic drift. GISAID and Nextstrain were both promptly adopted for collecting and analyzing SARS-CoV-2 genomic data, becoming the largest global system for tracking SARS-CoV-2 evolution and monitoring of the new variants.

The widespread application of sequencing technologies became possible because of extensive efforts by the scientific community to benchmark and standardize sequencing protocols and open-source bioinformatics workflows for accurate consensus genome assembly29. However, the use of proprietary next-generation sequencing solutions and software has been more commonplace in well-resourced national and state/province level public health labs. The accessibility of tiled primer sequences (e.g., ARCTIC or midnight primer sets), lower costs of Illumina and Oxford Nanopore sequencing along with open access bioinformatics workflows supported sequencing in dozens of regional public health labs and academic institutions across the world. By December 24th, 2021, 80.49% of available SARS-CoV-2 genomic data at GISAID was generated by Illumina sequencers, 12.46% by Oxford Nanopore, and 3.85% by Pacbio, 1.59% by IonTorrent, 1.29% by BGI, 0.31% by Sanger and 0.02% by QIAGEN (Figure S1a). NCBI GenBank has 91.04% genomic data sequenced by Illumina, 8.1% by Oxford Nanopore, 0.47% by IonTorrent, < 0.01% by PacBio, and 0.38% unspecified (Figure S1b).

This democratization of viral sequencing methods has helped build pathogen sequencing capacity in low- to middle-income countries and has fostered insights into the genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2, including emergence and spread of variants, for example in Colombia (VOI Mu), Ukraine (VOC Delta), the Philippines (VOC Alpha), in the U.K. (VOC Alpha) as it moved to the U.S., and in South Africa, where immune evasive VOC Omicron was identified by genome sequencing30-33.

Bioinformatics methods enable tracking COVID-19 geographical spread in real time

As viruses evolve, tracking the appearance of new mutations and the locations where they were introduced can reveal geographical transmission routes. These routes help distinguish imported cases from community transmission, aiding the identification of high-risk transmission routes that can be subject to enhanced public health control34. Comparative genomic analyses for studying COVID-19 outbreak transmission dynamics have been mostly conducted using classic maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic methods35. Unfortunately, ML methods are not scalable enough to handle large volumes of SARS-CoV-2 genomic data available. It is often a requirement, therefore, for ML to reduce sample size and to consider only a fraction of the data in order to conduct the analysis, which can potentially compromise the accuracy of the results. Alternatively, more scalable approximate maximum parsimony methods (MP) can be used for phylogeny reconstruction for SARS-CoV-2 dense data36. Indeed, it was shown theoretically that with dense enough sampling, MP produces an ML tree under certain maximum likelihood models37-39. Another approach has been to use network-based methods, which are significantly faster but theoretically less accurate than phylogeny-based methods40-42.

Diverse publicly available SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences from around the world have aided efficient and accurate tracking of local and global SARS-CoV-2 transmission routes43-45 (Figure S3). Phylogenetics methods (listed in Table S2) revealed that SARS-CoV-2 was introduced into Europe from China and into the US from China and Europe34,46-48 and have also been used to track domestic transmission chains and differentiate them from international ones. For example, studies showed that SARS-CoV-2 was likely introduced in Connecticut via a domestic transmission route while the most successful viral introductions in Arizona were likely via domestic travel34,49. New York City area experienced multiple introductions of SARS-CoV-2, primarily from Europe50. Similarly, phylogenetic analysis suggested that SARS-CoV-2 was likely introduced into France from several countries, including China, Italy, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Madagascar51 (Figure 1e, Tables S2).

Differences in sampling across geographical locations and over time represent a considerable challenge to accurately reconstruct spatial transmission patterns. However, additional data such as travel information and epidemiological estimates may help mitigate non-uniform sampling across geographical locations and time and contribute to a more complete picture of viral spread. This has been illustrated by a study of SARS-CoV-2 importation and establishment in the UK52. Large-scale genomic data resulted in estimates of the number and timing of introductions events, but its combination with epidemiological and travel data allowed identification of the spatiotemporal origins of these introductions. Such additional data sources are also being increasingly integrated in phylodynamic inferences. For example, a study of the contribution of persistence versus new introductions to the second COVID-19 wave in Europe made use of Google mobility data to inform the phylogeographic component of the genomic reconstruction53. Furthermore, the individual travel history of sampled individuals can be formally incorporated in such analyses54.

Additionally, phylogenetics can be used to monitor the effectiveness of global travel restrictions and lockdowns. For example, it was shown that the risk of domestic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Connecticut already exceeded that of international introduction at the time federal travel restrictions were imposed, highlighting the critical need for local surveillance34. Similarly in Brazil, three clades of European origin were established prior to the initiation of travel bans and lockdowns55. In the UK, lineages introduced prior to national lockdown were shown to be larger and more dispersed and lineage importation and regional lineage diversity declined after lockdown52. Phylogenetics showed that, due to violations of imposed lockdowns with sea trade, several SARS-CoV-2 international introductions likely occurred in Morocco56. In Australia, lockdown effectiveness was validated using SARS-CoV-2 genomic data coupled with agent-based modeling, a computation tool to simulate the interactions of autonomous agents such as individuals57. Phylogenetic modeling of over 11,000 SARS-CoV-2 genomes collected in Switzerland throughout 2020 enabled estimating the effect of different public health measures, including lockdown, border closure, and test-trace-isolate efforts58. Similarly, comparative phylodynamics analysis of SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics in neighboring Eastern European countries of Belarus and Ukraine, that followed highly different COVID-19 containment policies, allowed to assess the effectiveness of public health intervention measures in this region, and highlight the role of regional political and social factors in the virus spread59.

Genomics methods enable wastewater-based monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology

The presence of trace viral genomic material in wastewater has been successfully employed to track antibiotic use60, tobacco consumption61 and the monitoring of several respiratory and enteric viruses including poliovirus62. Although COVID-19 is primarily associated with respiratory symptoms, SARS-CoV-2 is regularly shed in feces of infected individuals63. As of December 2021, wastewater-based surveillance for tracking SARS-CoV-2 viral infection dynamics64 has been implemented in many countries around the world (Figure 1e).

Wastewater-based epidemiology has been shown to provide more balanced estimates of viral prevalence rates in a population than clinical testing alone due to inherent limitations in testing resources and/or testing uptake rates especially in underserved communities. Combining clinical diagnostics with wastewater-based surveillance can provide a more comprehensive community-level profile of both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, enabling identification of hospital capacity needs65-72. Additionally, an important advantage of wastewater monitoring is the ability to detect early-stage outbreaks before they become widespread62,73-76. Although tracking of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA via qPCR-based methods can reveal temporal changes of virus prevalence in a given population, it cannot provide underlying epidemiological information for identifying transmission or genomic details on emerging variants. Tracking viral genomic sequences from wastewater significantly ameliorates community prevalence estimates and also detects emerging variants. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 viral genomic sequences from wastewater using a targeted tiled amplicon-based sequencing approach would significantly ameliorate community prevalence estimates and also detect emerging variants77.

Wastewater genomic epidemiology can also act as a surrogate to elucidate strain geospatial distributions, helping identify outbreak clusters and track prevailing and newly emerging variants, covering even areas with insufficient clinical testing rates. However, the highly variable nature of wastewater, low viral loads, fragmented RNA and the presence of multiple genotypes in a single sample makes it challenging to obtain good quality genome sequences and discern lineages with a high degree of accuracy78.

The commonly used tools used for discerning viral lineages in clinical samples such as pangolin3 and UShER79 cannot deconvolute the multiple lineages that are commonly observed in a single wastewater sample and at best detect the most dominant one. As existing lineage calling methods require a single consensus sequence to perform assignment, they are ill-equipped to capture the diversity present in mixed viral samples. Hence, tools to robustly identify the multiple lineages and their relative proportions present in wastewater are critical in understanding and interpreting the underlying sequence data obtained from these samples. For example, a depth-weighted demixing algorithm Freyja80, uses a “barcode” library of lineage defining mutations to represent each viral variant and can be used to recover relative abundance in the sample. This approach enabled the early detection of emerging VOCs in wastewater up to 14 days in advance of first clinical detection and also identified multiple instances of cryptic transmission not observed via clinical genomic surveillance81. Similar algorithms for mutation calling, haplotype reconstruction, and population characterization in viral specimens, can also be used to deconvolute the mixture of variants present in a wastewater sample82,83. By searching for signature mutations co-occurring on the same amplicon, variant B.1.1.7 in wastewater was detected eight days before the first patient sample was tested positive for the variant84. Similarly, RNA transcript quantification methods, such as Kallisto, can be used to estimate the relative abundance of SARS-CoV-2 variants in wastewater85. Both digital PCR-based and sequencing-based estimates of variant abundance in wastewater have been used to derive the fitness advantage of a recently introduced variant, an important epidemiological parameter to assess the expected transmissibility and spread of the variant86,87.

Alternatively, viral genomes in wastewater can be sequenced via next generation sequencing approaches after enriching for a wider array of RNA viruses present in a sample through a hybrid probe-capture approach. This approach allows characterization of the prevalent SARS-CoV-2 genomic variants in a defined local region and dynamics of other pathogenic viruses present in the sample88-90. Shotgun metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing (i.e. community-based sequencing approaches) can provide a comprehensive snapshot of the viral community ecology and thereby aid in tracking of viruses of clinical significance in a community.

As SARS-CoV-2 transitions to become an endemic pathogen, wastewater genomic sequencing offers a scalable, less expensive, long-term passive surveillance tool for tracking emerging variants in the population. A global metagenomics approach has been suggested to detect, collect, and store samples in preparation for future pandemics91,92. Resources such as GISAID, GenomeTrakr93,94 and CDC-NWSS95 (National Wastewater Surveillance System)95 could facilitate the above efforts.

Outlook

The unprecedented volume of available SARS-CoV-2 genomic data coupled with available bioinformatics tools accelerated the prompt and effective characterization of SARS-CoV-2 genomes and provided tools to epidemiologists and public health officials to more effectively respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Numerous independent efforts across the globe utilized bioinformatics methods that demonstrated the utility of genomics-based approaches and created a solid foundation for the response to COVID-19 and future pandemics. This was achieved by the standardization of methodology, protocol and data sharing, and applications of using SARS-CoV-2 genomic data in epidemiological investigations.

Genome-based surveillance has been shown to be beneficial in addressing COVID-19. However, the unprecedented volume of sequencing data, currently six million complete SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences in databases, challenged the current systems of data storage, processing, and bioinformatics analysis16,19,96. Due to various technological burdens, such systems were still in the early stages of development in December of 2019. COVID-19 has led to the mobilization of financial, scientific, and developmental resources in record time, with numerous global surveillance systems that provided resources for outbreak response using SARS-CoV-2 genome analysis (Table 1). A notable example is the timely deployment of GISAID and Nextstrain for addressing the COVID-19 response. This technology has taken a lead in centralizing efforts to collect and analyse SARS-CoV-2 genomic data.

Table 1:

Online services with SARS-CoV-2 genome resources and analytics

| Resource | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| GISAID | Platform for assembled genome sharing and analysis | https://www.gisaid.org/ |

| NCBI GenBank | Sequence read archive (SRA) | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/ |

| COG-UK | United Kingdom sequences database | https://www.cogconsortium.uk/ |

| PANGO | Lineage analytics | https://cov-lineages.org/ |

| Nextstrain | Phylogenetic analysis | https://nextstrain.org/ |

| WBEC | Wastewater analytics | https://www.covid19wbec.org/ |

| COVID-3D | Structural changes of lineages | http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/covid3d/ |

| Outbreak.info | Variants reports | https://outbreak.info/ |

| CoVizu | Global and local variant distribution analytical tool | https://filogeneti.ca/covizu/ |

| CoVsurver | GISAID quality check and annotation tool identifying phenotypically or epidemiologically interesting candidate amino acid (aa) changes for further research |

https://corona.bii.a-star.edu.sg/

https://www.gisaid.org/epiflu-applications/covsurver-mutations-app/ |

| KSA-KAUST | COVID-19 virus mutation tracker | https://www.cbrc.kaust.edu.sa/covmt/ |

| COVID Genes | Shotgun RNA-seq viral data and host responses | https://covidgenes.weill.cornell.edu/ |

Emerging VOCs, VOIs, and VUIs are likely to continue shaping the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Global genomics-based surveillance for new variants, in our view, will continue to play a leading role, with information on all SARS-CoV-2 lineages being collected and made available online for the rapid evaluation of their impact on transmission, virulence, and vaccine escape97,98. Targeted genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in immunocompromised patients, in our view, can provide useful insights into the mechanisms of appearance of newly emerging VOCs. This can be done by applying bioinformatics tools for intra-host population analysis similar to those that are already available for other RNA viruses such as HCV and HIV82,99-102.

Efficient early detection and tracking of potentially dangerous variants requires real-time data from all countries103. The European Commission, for example, recommended gaining a capacity of sequencing of at least 5% of positive test results, which can be a good global standard. Yet, many underdeveloped countries in the world face insurmountable logistic, technological, and financial barriers to operating sequencing centers to accommodate this scale, suggesting that developed countries share responsibility for global surveilance104. Following the example of many African countries, additional sequencing centers in countries without viral genomic sequencing could be established. In regions where that is not practical, a logistically efficient system of obtaining and delivering samples to sequencing centers in other countries might be an appealing alternative.

In our view, there are three potential benefits of a standard genome epidemiological sequencing system. The immediate benefit will allow improved timeliness and accuracy of tracking emerging VOI and VOC. A longer-term goal is an improved ability to learn about evolutionary pressures driving the emergence of novel, potentially dangerous variants. Presently, VOC are declared based on their increased transmissibility or virulence, or decreased effectiveness of public health and social measures, available diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics. Learning more about evolutionary dynamics of emergent strains may lead to predictions of VOI based on genomic sequence alone, further improving response times. Finally, a truly global system of pathogen genome sequencing and analysis is likely to improve our ability to combat future pandemics.

Global coordination of genomic data surveys will also allow for wider application of wastewater-based or environmental-based virus surveillance105. Currently, wastewater-based monitoring lacks the granularity of clinical diagnostic testing and cannot discern a particular area of an outbreak when the wastewater treatment plant serves a large population. Sampling at a higher spatial resolution within the sewer system or even at a building-level scale could potentially provide early indications of viral outbreaks and help monitor their progression106.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank William M. Switzer and Ellsworth M. Campbell from the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 30333 GA, USA for useful discussions and suggestions. We thank Jason Ladner from the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ for providing suggestions and feedback. We also thank numerous anonymous reviewers who helped improve our manuscript by their valuable comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Serghei Mangul: SM was partially supported by National Science Foundation grants 2041984. Tommy Lam: TL is supported by NSFC Excellent Young Scientists Fund (Hong Kong and Macau) (31922087), RGC Collaborative Research Fund (C7144-20GF), RGC Research Impact Fund (R7021-20), the Innovation and Technology Commission’s InnoHK funding (D24H), and Health and Medical Research Fund (COVID190223). Pavel Skums: PS was supported by the NIH grant 1R01EB025022 and NSF grant 2047828. Malak Abedalthagafi: MA acknowledges King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology and the Saudi Human Genome Project for technical and financial support (https://shgp.kacst.edu.sa) Nicholas Wu: NW was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R00 AI139445, DP2 AT011966, R01 AI167910). Adam Smith: AS acknowledge funding from NSF grant no. 2029025. Alex Zelikovsky: AZ has been partially supported by NIH Grants 1R01EB025022-01 and NIH Grant 1R21CA241044-01A1. Sergey Knyazev: SK has been partly supported by Molecular Basis of Disease at Georgia State University, and NIH awards R01 HG009120, R01 MH115676, R01 AI153827, U01 HG011715. Aiping Wu: AW has been supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2021-I2M-1-061). Rob Knight: RK was supported by NSF project 2038509, RAPID: Improving QIIME 2 and UniFrac for Viruses to Respond to COVID-19. CDC project 30055281 with Scripps led by Kristian Andersen, Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 to investigate local and cross-border emergence and spread. Joel O. Wertheim: JOW was supported by NIH-NIAID R01 AI135992, receives funding from CDC unrelated to this work. Tetyana I. Vasylyeva: TIV is supported by the Branco Weiss Fellowship. Yuri Porozov: YP was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of state support for the creation and development of World-Class Research Centers “Digital biodesign and personalized healthcare” N◦075-15-2020-926. Eric Bortz: E.B. was supported by a US NIGMS IDeA Alaska INBRE (P20GM103395) and NIAID CEIRR (75N93019R00028). C.E.M. thanks Testing for America (501c3), OpenCovidScreen Foundation, Igor Tulchinsky and the WorldQuant Foundation, Bill Ackman and Olivia Flatto and the Pershing Square Foundation, Ken Griffin and Citadel, the US National Institutes of Health (R01AI125416, R01AI151059, R21AI129851, U01DA053941), and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (G-2015-13964). Charles Y. Chiu: CYC is supported by US CDC Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) for Infectious Diseases Grant 6NU50CK000539 to the California Department of Public Health, the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) at UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco, National Institutes of Health grant R33AI12945. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contract 75D30121C10991. Andrey Komissarov: AK was partly supported by RFBR grant 20-515-80017. Philippe Lemey: PL acknowledges support from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. ~725422 - ReservoirDOCS), the Wellcome Trust through project 206298/Z/17/Z (Artic Network) and from NIH grants R01 AI153044 and U19 AI135995. Keith Crandall: KC acknowledges support from the US NSF award EEID-IOS-2109688. Fyodor Kondrashov: FK’s work was supported by the ERC Consolidator grant to FAK (771209—CharFL).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG & Gao GF A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet vol. 395 470–473 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grubaugh ND et al. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nat Microbiol 4, 10–19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rambaut A et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol 5, 1403–1407 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim SSA & Karim QA Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Rockefeller Foundation Releases New Action Plan to Accelerate Development of a National System for Gathering and Sharing Information on SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Variants and Other Pathogens. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/news/the-rockefeller-foundation-releases-new-action-plan-to-accelerate-development-of-a-national-system-for-gathering-and-sharing-information-on-sars-cov-2-genomic-variants-and-other-pathogens/.

- 6.Huang C et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu F et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579, 265–269 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW & Lipman DJ Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boni MF et al. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Microbiol (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Pipes L & Nielsen R Synonymous mutations and the molecular evolution of SARS-CoV-2 origins. Virus Evol 7, veaa098 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolgin E The tangled history of mRNA vaccines. Nature 597, 318–324 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shu Y & McCauley J GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data--from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance 22, 30494 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An integrated national scale SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance network. The Lancet Microbe (2020) doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes JD et al. The UCSC SARS-CoV-2 Genome Browser. Nat. Genet 52, 991–998 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuiken C, Korber B & Shafer RW HIV sequence databases. AIDS Rev. 5, 52–61 (2003). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxmen A One million coronavirus sequences: popular genome site hits mega milestone. Nature (2021) doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01069-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalia K, Saberwal G & Sharma G The lag in SARS-CoV-2 genome submissions to GISAID. Nat. Biotechnol 39, 1058–1060 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inzaule SC, Tessema SK, Kebede Y, Ogwell Ouma AE & Nkengasong JN Genomic-informed pathogen surveillance in Africa: opportunities and challenges. Lancet Infect. Dis (2021) doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30939-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Noorden R Scientists call for fully open sharing of coronavirus genome data. Nature 590, 195–196 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elbe S & Buckland-Merrett G Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Glob Chall 1, 33–46 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geoghegan JL & Holmes EC The phylogenomics of evolving virus virulence. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 756–769 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dorp L et al. Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infect. Genet. Evol 104351 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y-Z & Holmes EC A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell 181, 223–227 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korber B et al. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell (2020) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao K et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet 22, 757–773 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp SA et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature (2021) doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hay AJ & McCauley JW The WHO global influenza surveillance and response system (GISRS)-A future perspective. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 12, 551–557 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadfield J et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bull RA et al. Analytical validity of nanopore sequencing for rapid SARS-CoV-2 genome analysis. Nat. Commun 11, 6272 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laiton-Donato K et al. Genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Colombia. bioRxiv (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.20135715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yakovleva A et al. Tracking SARS-COV-2 Variants Using Nanopore Sequencing in Ukraine in Summer 2021. Res Sq (2021) doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1044446/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tablizo FA et al. Detection and Genome Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 Variants Belonging to the B.1.1.7 Lineage in the Philippines. Microbiol Resour Announc 10, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viana R et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.12.19.21268028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fauver JR et al. Coast-to-Coast Spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the Early Epidemic in the United States. Cell (2020) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morel B et al. Phylogenetic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Data Is Difficult. Mol. Biol. Evol 38, 1777–1791 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novikov D et al. Scalable Reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 Phylogeny with Recurrent Mutations. J. Comput. Biol 28, 1130–1141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steel M & Penny D Two further links between MP and ML under the poisson model. Appl. Math. Lett 17, 785–790 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolley SM, Posada D & Crandall KA A comparison of phylogenetic network methods using computer simulation. PLoS One 3, e1913 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wertheim JO, Steel M & Sanderson MJ Accuracy in near-perfect virus phylogenies. Syst. Biol (2021) doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syab069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Weaver S, Leigh Brown AJ & Wertheim JO HIV-TRACE (TRAnsmission Cluster Engine): a Tool for Large Scale Molecular Epidemiology of HIV-1 and Other Rapidly Evolving Pathogens. Mol. Biol. Evol 35, 1812–1819 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knyazev S et al. A Novel Network Representation of SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing Data. in Bioinformatics Research and Applications 165–175 (Springer International Publishing, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell EM et al. MicrobeTrace: Retooling molecular epidemiology for rapid public health response. PLoS Comput. Biol 17, e1009300 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blair C & Ané C Phylogenetic Trees and Networks Can Serve as Powerful and Complementary Approaches for Analysis of Genomic Data. Syst. Biol 69, 593–601 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin MA, VanInsberghe D & Koelle K Insights from SARS-CoV-2 sequences. Science 371, 466–467 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodcroft EB et al. Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. Nature 595, 707–712 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNamara RP et al. High-Density Amplicon Sequencing Identifies Community Spread and Ongoing Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in the Southern United States. Cell Rep. 33, 108352 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nadeau SA, Vaughan TG, Scire J, Huisman JS & Stadler T The origin and early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Worobey M et al. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America. Science (2020) doi: 10.1126/science.abc8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladner JT et al. An Early Pandemic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Population Structure and Dynamics in Arizona. MBio 11, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez-Reiche AS et al. Introductions and early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the New York City area. Science (2020) doi: 10.1126/science.abc1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gámbaro F et al. Introductions and early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in France, 24 January to 23 March 2020. Euro Surveill. 25, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.du Plessis L et al. Establishment and lineage dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the UK. Science 371, 708–712 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lemey P et al. Untangling introductions and persistence in COVID-19 resurgence in Europe. Nature 595, 713–717 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemey P et al. Accommodating individual travel history and unsampled diversity in Bayesian phylogeographic inference of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun 11, 5110 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Candido DDS et al. Routes for COVID-19 importation in Brazil. J. Travel Med 27, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Badaoui B, Sadki K, Talbi C, Salah D & Tazi L Genetic diversity and genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Morocco. Biosaf Health 3, 124–127 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rockett RJ et al. Revealing COVID-19 transmission in Australia by SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing and agent-based modeling. Nat. Med 26, 1398–1404 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nadeau SA et al. Swiss public health measures associated with reduced SARS-CoV-2 transmission using genome data. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.11.11.21266107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nemira A et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics in Belarus in 2020 revealed by genomic and incidence data analysis. Communications Medicine 1, 1–9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fahrenfeld N & Bisceglia KJ Emerging investigators series: sewer surveillance for monitoring antibiotic use and prevalence of antibiotic resistance: urban sewer epidemiology. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology vol. 2 788–799 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castiglioni S, Senta I, Borsotti A, Davoli E & Zuccato E A novel approach for monitoring tobacco use in local communities by wastewater analysis. Tobacco Control vol. 24 38–42 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sims N & Kasprzyk-Hordern B Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: Monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level. Environ. Int 139, 105689 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Y et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol 92, 833–840 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.COVID-19 wastewater epidemiology SARS-CoV-2. covid19wbec.org https://www.covid19wbec.org.

- 65.Weidhaas J et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater with COVID-19 disease burden in sewersheds. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Medema G, Heijnen L, Elsinga G, Italiaander R & Brouwer A Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in Sewage and Correlation with Reported COVID-19 Prevalence in the Early Stage of the Epidemic in The Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 7, 511–516 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahmed W et al. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: A proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ 728, 138764 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonzalez R et al. COVID-19 surveillance in Southeastern Virginia using wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Res. 186, 116296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peccia J et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Medema G, Heijnen L, Elsinga G, Italiaander R & Brouwer A Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 in sewage. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.20045880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu F et al. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater foreshadow dynamics and clinical presentation of new COVID-19 cases. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.15.20117747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karthikeyan S et al. High throughput wastewater SARS-CoV-2 detection enables forecasting of community infection dynamics in San Diego county. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.16.20232900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farkas K, Hillary LS, Malham SK, McDonald JE & Jones DL Wastewater and public health: the potential of wastewater surveillance for monitoring COVID-19. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health vol. 17 14–20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larsen DA & Wigginton KR Tracking COVID-19 with wastewater. Nat. Biotechnol (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt C Watcher in the wastewater. Nat. Biotechnol 38, 917–920 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothman JA et al. RNA Viromics of Southern California Wastewater and Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Single-Nucleotide Variants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 87, e0144821 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.R&d, D. P. et al. COVID-19 ARTIC v3 Illumina library construction and sequencing protocol protocol metadata. protocols.io; https://www.protocols.io/view/covid-19-artic-v3-illumina-library-construction-an-bgxjjxkn/metadata (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharkey ME et al. Lessons learned from SARS-CoV-2 measurements in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ 798, 149177 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turakhia Y et al. Ultrafast Sample placement on Existing tRees (UShER) enables real-time phylogenetics for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat. Genet 53, 809–816 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freyja: Depth-weighted De-Mixing. (Github; ). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karthikeyan S et al. Wastewater sequencing uncovers early, cryptic SARS-CoV-2 variant transmission. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.12.21.21268143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knyazev S, Hughes L, Skums P & Zelikovsky A Epidemiological data analysis of viral quasispecies in the next-generation sequencing era. Briefings in Bioinformatics (2020) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Posada-Céspedes S et al. V-pipe: a computational pipeline for assessing viral genetic diversity from high-throughput data. Bioinformatics (2021) doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jahn K et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Switzerland by genomic analysis of wastewater samples. medRxiv (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baaijens JA et al. Variant abundance estimation for SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater using RNA-Seq quantification. medRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.08.31.21262938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Caduff L et al. Inferring transmission fitness advantage of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in wastewater using digital PCR. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.08.22.21262024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jahn K et al. Detection and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 genomic variants in wastewater. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.01.08.21249379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crits-Christoph A et al. Genome sequencing of sewage detects regionally prevalent SARS-CoV-2 variants. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.13.20193805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Izquierdo Lara RW et al. Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 circulation and diversity through community wastewater sequencing. Public and Global Health (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.09.21.20198838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagy-Szakal D et al. Targeted Hybridization Capture of SARS-CoV-2 and Metagenomics Enables Genetic Variant Discovery and Nasal Microbiome Insights. Microbiol Spectr 9, e0019721 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carbo EC et al. Coronavirus discovery by metagenomic sequencing: a tool for pandemic preparedness. J. Clin. Virol 131, 104594 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bedford J et al. A new twenty-first century science for effective epidemic response. Nature 575, 130–136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; https://www.fda.gov/food/whole-genome-sequencing-wgs-program/wastewater-surveillance-sars-cov-2-variants (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 94.BioProject. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/757291.

- 95.CDC. National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/wastewater-surveillance/wastewater-surveillance.html (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hodcroft EB et al. Want to track pandemic variants faster? Fix the bioinformatics bottleneck. Nature 591, 30–33 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rambaut A et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol 2020. Preprint] July 15, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maxmen A Massive Google-funded COVID database will track variants and immunity. Nature (2021) doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knyazev S et al. Accurate assembly of minority viral haplotypes from next-generation sequencing through efficient noise reduction. Nucleic Acids Res. (2021) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sapoval N et al. SARS-CoV-2 genomic diversity and the implications for qRT-PCR diagnostics and transmission. Genome Res. 31, 635–644 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lythgoe KA et al. SARS-CoV-2 within-host diversity and transmission. Science 372, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Butler D et al. Shotgun transcriptome, spatial omics, and isothermal profiling of SARS-CoV-2 infection reveals unique host responses, viral diversification, and drug interactions. Nat. Commun 12, 1660 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kissler SM et al. Viral Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Persons. N. Engl. J. Med 385, 2489–2491 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.MacKay MJ et al. The COVID-19 XPRIZE and the need for scalable, fast, and widespread testing. Nat. Biotechnol 38, 1021–1024 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Danko D et al. A global metagenomic map of urban microbiomes and antimicrobial resistance. Cell 184, 3376–3393.e17 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bogler A et al. Rethinking wastewater risks and monitoring in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Sustainability (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00605-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.