Abstract

Reticence toward COVID-19 vaccination is more prevalent among women, people with low income, people who feel close to parties on the Far Right and Far Left and people who feel close to no party at all. It illustrates a mistrust of state institutions and policy-makers in general.

The arguments in favor of Covid vaccine refusal are safety concern, and the contention that COVID is a mild disease. That said, vaccine hesitancy is vaccine-specific, with a major difference between Pfizer/Moderna and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines.

Aside from vaccine hesitancy, vaccination intention rate has approached 80%.

Keywords: Covid vaccine, Vaccine hesitancy, RNA vaccine, Health pass

The profile of people not planning to be vaccinated against COVID-19 has remained very stable since the beginning of the campaign. Reticence toward COVID-19 vaccination is more prevalent among women, people with low income, people who feel close to parties on the Far Right and Far Left and people who feel close to no party at all [1], [2], [3].

The “non-party” group is among the most reticent towards vaccines, illustrating general mistrust of state institutions and policy-makers. The relationship between distrust of state institutions and vaccine hesitancy is particularly evident in the overseas territories and in southern France.

Age is also an important factor in vaccine hesitancy, with very large differences in vaccination intentions between people under 45 and those over 65 years old. The differences illustrate the perceived threat of the disease and the notion that for the most vulnerable people can COVID-19 be severe.

The reasons for refusal of COVID-19 vaccines have remained stable and are based on two main perceptions: that vaccines are not safe, and that COVID-19 is not a serious disease. These two motives are actually related, as behind the perception that “vaccines are not safe” is the implication that COVID-19 is “not particularly dangerous”. Indeed, the definition of how safe a vaccine must be to be perceived as safe is largely dependent on how dangerous is the disease.

Vaccine hesitancy is largely vaccine-specific. As early as December 2020, studies showed a preference for Pfizer-BioNTech-vaccines over Oxford-AstraZeneca-vaccines, which was strongly reinforced after the pharmacovigilance alerts of March 2021 [4]. It should be stressed that these public perceptions are not entirely at odds with scientific reality. In fact, differences in effectiveness between Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca-vaccines have been suggested, and pharmacovigilance alerts led to restriction of the indications of Oxford-AstraZeneca-vaccines.

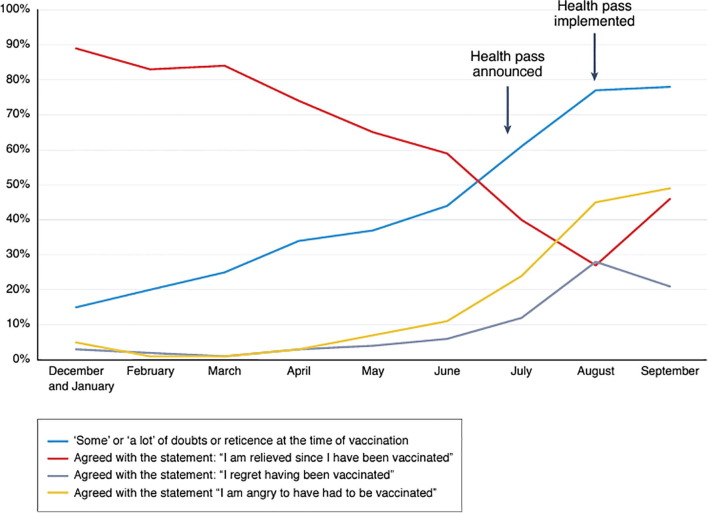

In parallel to evolution of the hesitancy profile and the reasons for vaccine refusal, vaccination intentions have varied significantly. In early July 2021, vaccination intentions came to 80%, but vaccination coverage was lower. This discrepancy sheds light on a potential disconnect between attitudes and behaviors. There are two main reasons for this: access to vaccination and complacency. The French health pass was announced in July 2021, implemented in August 2021 and proved to be very effective in getting the complacent to transform their intention into action. At the same time, it forced many people to get vaccinated, even though they were not convinced of the benefits of this campaign. (Fig. 1 ) [5]. Paradoxically, the health pass did not reduce vaccine hesitancy.

Fig. 1.

Doubts about vaccination among the vaccinated [5].

The persistence of hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination is visible in the strong resistance of young children (5–11 years) towards vaccination [6].

As restrictions are being limited, it seems crucial not to neglect those still hesitant people who were vaccinated due to the constraints entailed by the health pass. Vaccination intentions depend, as we have mentioned, on perceptions of the danger of the disease, and at this time, the Omicron wave and the media in general have led some of us to believe that COVID-19 is not (or no longer) dangerous.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The meeting in which this topic was presented was funded by the French Infectious Diseases Society (SPILF).

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Peretti-Watel P., Seror V., Cortaredona S., Launay O., Raude J., Verger P., et al. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:769–770. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward J.K., Alleaume C., Peretti-Watel P., Peretti-Watel P., Seror V., Cortaredona S., et al. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113414. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajos N., Spire A., Silberzan L., Group for the E study The social specificities of hostility toward vaccination against Covid-19 in France. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0262192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward JK, Launay O, Bonneton M, Botelho-Nevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A, Grison D, et al. Enquête COVIREIVAC: les français et la vaccination. 2021. http://www.orspaca.org/sites/default/files/enquete-COVIREIVAC-rapport.pdf. Last accessed 06/18/2022.

- 5.Ward J.K., Gauna F., Gagneux-Brunon A., Botelho-Nevers E., Cracowski J.-L., Khouri C., et al. The French health pass holds lessons for mandatory COVID-19 vaccination. Nat Med. 2022;28:232–235. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CoviPrev : une enquête pour suivre l’évolution des comportements et de la santé mentale pendant l’épidémie de COVID-19 [Internet]. [cité 1 avr 2022]. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/coviprev-une-enquête-pour-suivre-l’évolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-sante-mentale-pendant-l-epidemie-de-covid-19.