Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous cell population with potent suppressive and regulative properties. MDSCs’ strong immunosuppressive potential creates new possibilities to treat chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases or induce tolerance towards transplantation. Here, we summarize and critically discuss different pharmacological approaches which modulate the generation, activation, and recruitment of MDSCs in vitro and in vivo, and their potential role in future immunosuppressive therapy.

Keywords: MDSC, pharmacotherapy, immune suppression, immunomodulation, inflammation

1. Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous immature immune cell population, originating from the common myeloid progenitor cell, with potent immunosuppressive effect on T cell proliferation and activity (1). MDSCs were first described in cancer patients and associated with increased tumor growth and T cell dysfunction (2). In this respect, MDSCs are mainly studied in the tumor microenvironment, where they inhibit the anti-tumor immune response and support tumor angiogenesis (1, 3). In the context of the tumor microenvironment, dampening MDSCs may decrease metastatic niche formation (3–5). However, MDSCs not only play a role in cancer but also in a variety of other pathological conditions associated with an inflammatory state, such as, chronic infections, autoimmunity, asthma, or obesity (6–9). In autoimmune diseases, MDSCs can be useful to protect against tissue damage driven by an imbalanced immune reaction. Furthermore, if the immune response needs to be dampened, e.g. after allograft transplantation, or in conditions such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), MDSCs’ immunosuppressive potential might be beneficial. So far, the majority of imbalanced immune conditions are treated by corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs which include substantial side effects. Therefore, MDSCs are a promising therapeutic target due to their immunosuppressive properties (10). This review discusses pharmacological approaches involved in the generation, recruitment and activation of MDSCs, providing possible clues for novel cellular immunosuppressive therapies.

1.1 Subsets

Due to the heterogeneity of the MDSC population, most marker proteins are not unique to MDSCs nor universally expressed. Nevertheless, two major subtypes can be distinguished: polymorphonuclear (PMN-) and monocytic (M-) MDSCs based on their similarities to neutrophils and monocytes, respectively. In mice, PMN-MDSCs are defined as CD11b+ Ly-6G+ Ly-6Clow and M-MDSCs as CD11b+ Ly-6G- Ly-6Chigh, while in humans PMN-MDSCs express CD11b+ CD14- CD15+ or CD11b+ CD14- CD66b+ and M-MDSCs CD11b+ CD14+ HLA-DR-/low CD15-. Only by means of these markers, PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs are undistinguishable from neutrophils and monocytes, respectively, and functional assays, such as T cell proliferation and cytokine release assays, are needed to evaluate the immunosuppressive activity (11). Unfortunately, MDSC heterogeneity as well as the significant overlap with more ‘conventional’ immune cell populations complicate the refinement of a universal distinctive MDSC signature. Quantitative tools, such as single-cell RNA sequencing and mass cytometry, as well as other advances contributing to the multi-omics approach, are starting to provide more insights into the phenotypic, morphological and functional heterogeneity of MDSCs. Recently, lectin-type oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1) has been described as a new marker for PMN-MDSCs in humans. LOX-1 can be found on macrophages, endothelial and smooth muscles cells, but importantly is not expressed on neutrophils and therefore presents a surface marker that helps to identify PMN-MDSCs (12). Furthermore, CD84 and JAML were recently identified as potential markers of MDSCs in breast cancer (13). Additionally, two arginase-1-expressing myeloid clusters were identified –Spp1+Apoe+C1qa+ and Gpnmb+Vegfa+Clec4d+Trem2+ – in murine tumors, where Trem2 was found to be associated with immunosuppressive function (14).

1.2 Origin and generation of MDSCs

During normal hematopoiesis common myeloid progenitor cells develop from hematopoietic stem cells and differentiate via immature myeloid cells into red blood cells, granulocytes, monocytes, thrombocytes and mast cells under the influence of growth factors, interleukins and other regulatory molecules. Under certain pathological conditions such as cancer, with chronic stimuli of a relatively low intensity, two signals are required for MDSCs proliferation. The first signal is responsible for stimulation of myelopoiesis with the inhibition of maturation and differentiation of progenitor cells and the expansion of immature myeloid cells while the second signal promotes the transformation into immunosuppressive MDSCs (15). Factors shown to be involved in MDSC expansion and activation include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), stem cell factor (SCF), cyclooxygenase (COX-) 2, prostaglandins (PG), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin (IL-) 6 (1). The Janus kinase (JAK) 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 pathway appears to be the most important regulator for MDSC expansion (1). For example, GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-6 induce the expansion of MDSCs through activation of STAT3 (15–18). The transcription factor interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 8 – downregulated by GM-CSF and G-CSF – acts as a STAT3- and STAT5-dependent negative regulator of MDSC generation (19). In addition, the β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) has been shown to play a role in MDSC generation and activation through STAT3 (20). Further underlining the importance of STAT3, several studies revealed that STAT3 inhibition dampened MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment and proved to be a useful anticancer therapy (21–23). Interferon (IFN-) γ activates the STAT1 pathway and leads to activation of MDSCs (24). Similarly, activation of the STAT6 pathway through IL-4 and IL-13 can induce immunosuppressive properties of MDSCs (15). Pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-) α, IL-1β, IL-12, PGE2 or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands enhance the immunosuppressive capacities of MDSCs through the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway (25–30). In detail, activation of PGE2 receptor (EP) 2 and EP4 inhibits receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3), which in turn enhances the NF-κB pathway, as activated RIPK3 is involved in its downregulation (31). Furthermore, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response pathway ends up in the NF-κB pathway and promotes the activation of immunosuppressive MDSCs. The function of this pathway is to protect the cell from cellular stress like shortage of nutrients, hypoxia, or low pH (12). Furthermore, inhibition of the Notch pathway and activation of the adenosine receptor promote the expansion of MDSCs (32, 33). Those mechanisms create possible targets for in vitro and in vivo generation of MDSCs. MDSCs themselves are considered as immature cells with a high plasticity. Under hypoxic conditions, MDSCs are able to differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages, M2-like macrophages, inflammatory dendritic cells or fibrocytes (34). Hence, some researchers state that MDSCs are not a definitive cell group, but rather cells in transitory states, whose differentiation is ongoing.

1.3 Recruitment

Once generated, MDSCs are recruited to the site of activity by chemokines. The role of several cytokines, chemokines and their receptors in MDSC recruitment is reviewed elsewhere (35). These chemokines have been described to play an important role in MDSC recruitment through their interaction with corresponding G-protein coupled chemokine receptors: C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL)1/CXCL2/CXCL5 with C-X-C motif receptor (CXCR)2, CXCL8 with CXCR1/CXCR2, CXCL17 with CXCR8, C-C motif ligand (CCL)2/CCL12 with CCR2, CCL3/CCL4/CCL5 with CCR5, and CCL15 with CCR1. Specifically, CXCR2 appears to be critical for MDSC recruitment (4, 36–42).

1.4 Mechanisms of immunosuppressive activity

Activated MDSCs carry out their suppressive activity on T cell proliferation by different mechanisms, which were reviewed by Gabrilovich and Nagaraj (1). Upon upregulation of transcription factors like STAT1, 3, 6 and NF-κB, the expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS), arginase-1 (Arg-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), NF-κB and idoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is increased. Production of ROS by nicotiamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase suppresses T cell function by destroying proteins, lipids and inducing apoptosis among other mechanisms (43, 44). Both Arg-1 and iNOS deprive L-arginine – an amino acid essential for T cell metabolism – from the microenvironment and thus, inhibit T cell proliferation by suppressing T cell cycle progression (45). In addition, the iNOS product nitric oxide (NO) suppresses T cell function and induces apoptosis by itself through different mechanisms (1). Simultaneously, IDO inhibits T cell proliferation by depleting tryptophan from T cell metabolism as well as increasing regulatory T cells (Treg) recruitment (46). Shifting the T cell population towards immunosuppressive forkhead box (Fox) P3+ Tregs presents another effective way of immunosuppression (47, 48). In addition, MDSCs have been shown to suppress B cell responses (49). There are also subset specific differences: M-MDSCs mainly use NO produced by iNOS to suppress T cell function, while PMN-MDSCs express higher levels of ROS and peroxynitrite, a product from the reaction of NO and superoxide anion (50, 51). Both M- and PMN-MDSC secrete Arg-1 (50).

2. Pharmacological approaches to modulate MDSCs

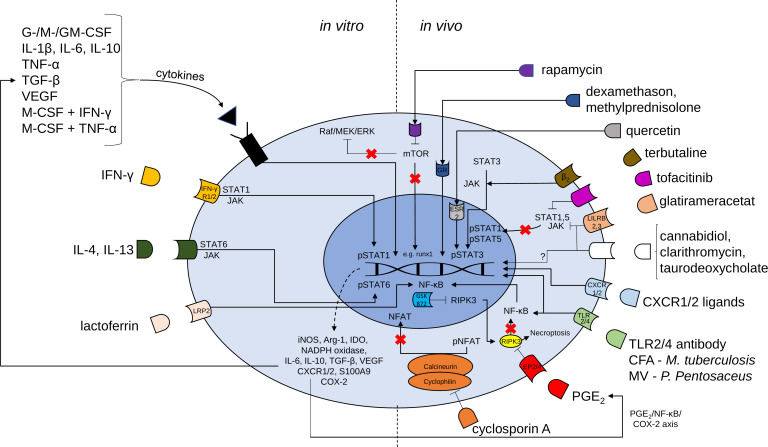

There are in principle two main pharmacological approaches for MDSC generation: Expanding MDSCs ex vivo and adoptively transferring them into patients or stimulating endogenous MDSC expansion/activation. Possible pharmacological approaches for MDSCs generation, activation and recruitment are presented in Table 1 as well as Figure 1 .

Table 1.

Potential pharmacological targets and drugs to modulate MDSCs to dampen inflammation.

| Target | Potential pharmacological drug | Effect of potential drug on MDSCs | Murine model(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2-AR | β2-AR agonists (Terbutalin) | Increased number | GVHD | (52) |

| Calcineurin | Calcineurin inhibitors (Cyclosporin A, Tacrolimus) | Increased number Increased activity |

Skin allograft | (53, 54) |

| CXCR1,2 | CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCL17 agonists | Increased number Increased activity |

Pulmonary hypertension | (4, 36–40) |

| EP2/4 | PGE2 (EP2/4 agonists) | Increased number Increased activity |

Asthma | (31, 55–57) |

| ERK1/2 | Glucosamine | Increased number Increased activity |

– | (58) |

| ESR2 | Quercetin | Increased number Increased activity |

Prostate carcinoma | (59, 60) |

| ETAR | ETAR antagonists (BQ123) | Increased number | Autoimmune hepatitis Colitis Pneumonia |

(61, 62) |

| Glucocorticoid receptor | Glucocorticoids (Dexamethasone, Methylprednisolone) | Increased number | Cardiac/skin allograft Multiple sclerosis |

(63–65) |

| LILRB | Glatirameracetat | Increased number Increased activity |

Inflammatory bowel disease | (66, 67) |

| LRP2 | Lactoferrin | Increased number | Autoimmune hepatitis Lung inflammation Necrotizing enterocolitis |

(68) |

| mTOR | mTOR inhibitors (Rapamycin) | Increased number Increased activity |

Cardiac/corneal/skin allograft GVHD Heart failure Hepatic/renal injury Wound healing |

(40, 48, 69–77) |

| RIPK3 | RIPK3 inhibitors (GSK872) | Increased number | Autoimmune hepatitis Multiple sclerosis |

(78–80) |

| STAT1, STAT5 | Tofacitinib, IFN-γ | Increased number Increased activity |

Arthritis Interstitial lung disease |

(81, 82) |

| TLR2, TLR4 | TLR2 ligands, TLR4 ligands (CFA-M.tuberculosis, MV-P.pentosaceus) | Increased number Increased activity |

Fibrosis Peritonitis Type-1-diabetes |

(83–87) |

| Unclear | Cannabidiol | Increased number | Autoimmune hepatitis Multiple sclerosis |

(88, 89) |

| Unclear | Claritromycin | Increased number | Post-influenza pneumonia Sepsis |

(90) |

| Unclear | Taurodeoxycholate | Increased number Increased activity |

Sepsis | (91) |

β2-AR, β2-adrenergic receptor; CFA, Complete Freund’s adjuvant; CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; EP, Prostaglandin E2 receptor; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ESR, Estrogen signaling receptor; ETAR, Endothelin A receptor; GVHD, Graft-versus-host disease; LILRB, Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; LRP, Lactoferrin receptor; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; MV, Membrane vesicles; RIPK3, Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3; STAT, Signal transducer and activator of transcription; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of possible pharmacological targets for the induction of MDSCs. Proliferation and activation of MDSCs is regulated by transcription factors such as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, STAT1, STAT5, STAT6 and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB). In vitro generation of MDSCs is induced by a large variety of cytokines and cytokine combinations and lactoferrin. MDSC generation may be followed by adoptive transfer cell therapy to induce the beneficial effects of MDSCs. Various compounds [e.g. rapamycin, glucocorticoids, terbutaline, tofacitinib, glatirameracetat, cannabidiol, clarithromycin, taurodeoxycholate, CXCR1 or CXCR2 ligands, complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), membrane vesicles (MV), Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/4 agonistic antibodies, prostaglandin E2, cyclosporine A and receptor interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 3 inhibitor (GSK 872)] may be used for accumulation of MDSCs in vivo. G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, M-CSF macrophage CSF, GM-CSF granulocyte-macrophage CSF, IL Interleukin, TNF tumor necrosis factor, TGF transforming growth factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, IFN interferon, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, JAK Janus kinase, LRP lactoferrin receptor, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, Arg arginase, IDO indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, NADPH nicotiamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, NFAT nuclear factor of activated t cells, p phosphorylated, CXCR CXC chemokine receptors, COX cyclooxygenase.

2.1 Adoptive transfer of in vitro/ex vivo generated/activated MDSCs

Non-stem cell-based cell therapies that use cells such as CAR-T cells, dendritic cells and natural killer cells are promising and rapidly evolving (92). MDSC cell therapy may be another promising strategy in this list, especially considering its potent immunosuppressive capacity and its role in maintaining immune tolerance in transplantation and autoimmunity. Several pre-clinical studies have shown promising therapeutic effects of the adoptive transfer of MDSCs in organ transplantation, autoimmune diseases as well as in a variety of other immune-related disorders, such as cyclosporin A-induced hypertension, heart failure and asthma (63, 69, 93–100). Here, we briefly discuss some of the cytokines and pharmacological compounds that have been identified to promote the generation and/or activation of MDSCs in vitro/ex vivo and were applied as MDSC cell therapy.

2.1.1 Cytokines

Park et al. demonstrated the beneficial role of in vitro generated MDSCs in the context of GVHD (101). Here, the highest efficiency of in vitro production of MDSCs from CD34+ human umbilical cord blood cells was achieved with a combination of GM-CSF and SCF, whereas G-CSF/SCF and M-CSF/SCF were less effective (101). Adoptively transferred MDSCs were shown to ameliorate GVHD and prolong survival in a murine xenogeneic model of GVHD by promoting Tregs and inhibiting the T helper (Th) 1 and Th17-driven inflammatory responses (101). MDSCs generated with GM-CSF/SCF were shown to exhibit increased immunosuppressive activity after the transfer in vivo compared to MDSCs generated in the presence of either G-CSF/SCF or M-CSF/SCF (101). Hsieh et al. also showed beneficial effects of adoptive transfer of MDSCs in renal fibrosis and diabetic neuropathy in diabetic mice (102). Here, murine bone marrow-derived MDSCs were induced with GM-CSF, IL-1β and IL-6 in vitro. In addition, Yang et al. induced M-MDSCs with combinations of M-CSF/IFN-γ and M-CSF/TNF-α, respectively, and demonstrated prolonged skin allograft survival upon adoptive transfer (103, 104). In vitro generated MDSCs, induced by GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-6, efficiently ameliorated autoimmune arthritis in mice (105). Recently, another group demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of splenic CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs, obtained from G-CSF-treated donor mice, are capable of prolonging heart allograft survival (93).

As already discussed above, there are many cytokines and cytokine combinations identified to play important roles in MDSC generation and activation. Here it is important to consider that certain cytokine signaling is required to induce MDSCs, and the discussed pharmacological compounds are insufficient to induce in vitro/ex vivo MDSCs without additional cytokine signaling.

2.1.2 Glucocorticoids

Zhao et al. induced MDSCs in vitro by means of GM-CSF and dexamethasone (63). Adoptive transfer of dexamethasone-induced MDSCs into mice prolonged heart allograft survival, likely through increased levels of iNOS and increased number of Tregs (63). Indeed, dexamethasone is already an established immunosuppressive drug, and these findings show that a part of its immunosuppressive activity is likely mediated by their effect on MDSCs.

2.1.3 Lactoferrin

Adoptive transfer of in vitro generated murine bone marrow-derived MDSCs treated with lactoferrin (LF) prolonged survival and ameliorated inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis in newborn mice as well as concanavalin-induced hepatitis and ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation (68). Both in vitro and in vivo LF treatment increased MDSC numbers, likely via NF-κB activation, but only in infant mice due to decreased LF receptor (LRP) 2 expression in adults (68). However, in vivo administration of LF was shown to be much less effective in recruiting and activating MDSCs compared to the adoptive transfer of in vitro generated MDSCs using LF. This study demonstrates the potential of targeting NF-κB and LRP2 to recruit MDSCs (68).

2.1.4 PGE2

PGE2, in combination with GM-CSF and either IL-4 or IL-6, was found to efficiently induce MDSCs ex vivo (55, 100). From the four EP subreceptors (EP1-4) of PGE2, EP2 and EP4, and not EP1 and EP3, were found to induce MDSC development, hinting at an important role of the adenylate cyclase/cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway (55, 100). Furthermore, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs generated in the presence of a selective EP4 receptor agonist dampened airway inflammatory features in a murine model of asthma (100).

2.1.5 Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

The combination of M-CSF and PMA was recently shown to induce MDSCs in vitro (106). The adoptive transfer of PMA-induced MDSCs induced immune tolerance in a mouse skin transplantation model, by inhibiting the T cell response, promotion of cytokine secretion and inducing Tregs (106). PMA significantly upregulated Arg-1 expression in MDSCs, and an Arg-1 inhibitor (nor-NOHA) diminished MDSC activity (106). This study confirms that in vitro induced-MDSCs may be promising targets for adoptive transfer to modulate immunosuppression, such as in organ transplantation.

2.1.6 Rapamycin

The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is frequently used in immunosuppressive therapy following allograft transplantation in order to prevent allograft rejection. Rapamycin is also applied on drug-eluting stents to decrease stent stenosis, via its anti-proliferative properties. Nakamura et al. performed adoptive transfer of in vitro generated MDSCs, treated with rapamycin, directly into the coronary artery of heart allografts in mice (48). Administration of rapamycin-induced MDSCs prolonged skin allograft survival and demonstrated the possibility of local MDSC therapy. Adoptive transfer of rapamycin-treated MDSCs resulted in improved outcomes concerning acute kidney injury, with increased Tregs number and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to adoptive transfer of MDSCs not treated with rapamycin (40).

To this end, the in vitro/ex vivo generation and subsequent adoptive transfer of MDSCs has been established in animal models and most studies observe a beneficial effect in the treatment of inflammatory diseases, yet human studies are needed to further confirm the therapeutic concepts. However, at the time of writing this review, no clinical trials investigating MDSC adoptive transfer as a cell therapy have been performed nor were registered in the clinical trial databases of the National Institute of Health 1 or the EU clinical trial register 2 . Nevertheless, the generation/expansion of endogenous MDSC, by administration of the right cytokine combination or potential medications, would be the more elegant way to generate, activate and recruit the MDSCs and dampen inflammatory diseases. We discuss the possibilities in the following chapter of this review.

2.2 In vivo generation, recruitment, and activation of MDSCs

2.2.1 Acetaminophen

Hsu et al. showed that the increase of intrahepatic MDSCs by a sublethal dose of acetaminophen was able to protect mice against subsequent lethal doses of acetaminophen, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/D-galactosamine or concanavalin A (107). This finding was confirmed by a loss of protection after MDSC depletion (107). The observed protective effect was likely mediated by increased iNOS expression, as iNOS-expressing MDSCs were found to induce the apoptosis of activated neutrophils and decreased the intrahepatic infiltration of elastase-expressing neutrophils (107). Furthermore, the group of Hsu et al. were able to generate human PMBC-derived MDSCs with a similar phenotype (107).

2.2.2 Rapamycin and other mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors

Besides the immune regulating features of rapamycin and its ability to generate MDSCs in vitro for cell therapy, rapamycin has also been linked to MDSC recruitment and activation in vivo. Nakamura et al. reported prolonged heart allograft survival in mice under Rapamycin administration, which was found to be related to increased number of MDSCs, particularly M-MDSCs, and iNOS expression (48). Zhang et al. showed that rapamycin treatment ameliorated acute kidney injury through the recruitment and activation of mainly PMN-MDSCs (40). A recent study by Scheurer et al. demonstrated that rapamycin administered after bone marrow transplantation promoted immunosuppressive properties of MDSCs and thus prevented GVHD (70). Furthermore, rapamycin treatment ameliorated heart failure in mice, likely through the induction of MDSCs, as MDSC depletion diminished this beneficial effect (69). Wei et al. treated cornea transplanted mice with eye drops containing rapamycin nano-micelles (71). An increased recruitment of MDSCs and expression of Arg-1 and iNOS was observed and was in line with a prolonged allograft survival. Also, in immunological hepatic injury, rapamycin treatment was found to promote MDSC recruitment, generation, and activity, and ameliorated the disease (72). Recently, our group demonstrated the allograft survival prolonging properties of rapamycin in obese mice through increased M-MDSCs number and activity (73). Taken together, rapamycin seems to be an efficient inductor of MDSC generation and activation, with the advantage of already being approved for clinical use for certain diseases. Furthermore, a novel mTOR inhibitor, INK128, was shown to promote wound healing in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice (74). mTOR deficiency in M-MDSCs was shown to induce tolerance of mouse cardiac allografts (75), while adoptive transfer of PMN-MDSCs lacking mTOR expression was shown to dampen acute GVHD (76), confirming the beneficial role of mTOR inhibition in promoting MDSC immune suppression.

However, the linking mechanism between mTOR and MDSCs is not fully understood. Nakamura et al. stated that mTOR inhibition could lead to increased activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, which caused MDSC recruitment and activation (48). Another possible mechanism responsible for MDSC activation is the downregulation of runt-related transcription factor 1 (runx1) gene expression (40). A third possible mechanism was recently described by Jia et al. who reported that AKT1, a known downstream target of mTOR, regulates MDSC immunosuppressive activities by suppressing hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-dependent glycolysis (77). Therefore, further research is necessary to further clarify the underlying mechanism.

2.2.3 Glucocorticoids

Evidence emerged showing that glucocorticoids may also carry out their immunosuppressive effect through the induction as well as the recruitment of MDSCs. Mechanistically, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is critical for the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs as GR activation leads to a release of CXCR2, which is one of the main chemokines involved in the recruitment of MDSCs to areas of inflammation (64). Liao et al. demonstrated the same effects and mechanisms of dexamethasone administration in vivo in a mouse model of skin allograft transplantation (64). Another frequently used glucocorticoid is methylprednisolone. Direct correlations between methylprednisolone administration and increases in the number of MDSCs, particularly PMN-MDSCs, have recently been demonstrated in a murine model of multiple sclerosis (MS) and human MS patients by Wang et al. (65). Interestingly, a difference in MDSC immunosuppressive activity was observed in mice compared to human MS patients, whereas MDSCs show higher immunosuppressive activity in the latter upon treatment with methylprednisolone. This was revealed by measuring MDSC activity in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice and MS patients, before and after methylprednisolone treatment (65). In mice, increased number of MDSCs were observed at the onset of EAE, but not after methylprednisolone pulse therapy. In contrast, in MS patients increasing MDSC numbers were observed in PBMCs after methylprednisolone application, and disease remission after treatment was correlated to the increased number of MDSCs (65). This highlights the complexity and importance of analyzing MSDC behavior, not only in mice, but also in humans. Furthermore, the mechanism of MDSC induction by glucocorticoids is linked to inhibition and downregulation of GR-β, which, if activated, antagonizes the effect of glucocorticoids (65). Mice only express one type of GR which might explain the higher MDSC activity observed in humans (63). Methylprednisolone is considered the main drug for chronic inflammatory conditions and is frequently used, not only in MS patients, but also in many other autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and rheumatic diseases (108). Hence, methylprednisolone and the GR, with its different subtypes, may provide promising targets for further research.

2.2.4 Chemokines

CXCR1 and CXCR2, among others, are highly expressed on MDSCs and responsible for their recruitment. Blockage of CXCR1 and CXCR2 with selective antagonists was shown to severely decrease the number of MDSC infiltration in pulmonary hypertension and carcinomas (4, 37). Furthermore, intratracheal administration of recombinant mouse protein CXCL17 has been shown to result in the recruitment of MDSCs into the lungs of mice (36). Selective CXCR1, CXCR2 and CXCL17 agonists seem to be promising pharmacological drugs for increasing MDSC migration. However, these agonists need to be further studied in the context of MDSC recruitment. Recently, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) – an environmental pollutant and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist – was shown to indirectly recruit MDSCs through strong induction of CXCR2 expression by down-regulating specific miRNAs (39). Upregulation of transcription factors responsible for CXCR2 ligands (CXCL1 and CXCL2) expression, like Snail, which acts through NF-κB pathway, also provides other possible targets related to chemokines (38). In addition, mTOR inhibition with rapamycin was found to result in increased CXCR2, CXCL1 and CXCL2 expression, which was directly linked to MDSC recruitment to the site of acute kidney injury (40). Overall, targeting chemokines and their receptors for MDSC recruitment seems promising, but the involved risks, as previously reported in cancer patients, should be taken into careful consideration (3–5). However, MDSCs primarily are involved in promoting pre-metastatic niche formation and not directly in tumor growth itself (109). Thus, the question can be raised whether it could be beneficial to use locally administered CXCR1 and CXCR2 ligands or CXCL17 only for tumor-free patients in sites of chronic inflammation. As administration of those ligands could increase the risk of pre-metastatic niche formation if tumor cells are present, but not if the patient is tumor-free. Alternatively, coating of allografts with chemokines and cytokines, e.g. GM-CSF and CXCL17, could be used to recruit MDCS to the allograft and locally reduce the immune response.

2.2.5 Endothelin (ET)A receptor antagonist

ET signaling mediates strong vasoconstrictor properties, and the ETA receptor antagonist, BQ123, is an effective therapy for hypertension and obese cardiomyopathy (61). Recently, BQ123 was shown to induce PMN-MDSC-mediated immune suppression in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, papain-induced pneumonia, and concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in mice (62). Both the treatment of BQ123, as well as the transfer of BQ123-induced PMN-MDSCs were effective in dampening inflammation (62). Further analysis showed that BQ123 mediates it effects through the IL13/STAT6/Arg1 signaling pathway (62).

2.2.6 β2-agonists

Recently, one promising approach in endogenous MDSC generation was achieved with the help of β2-AR agonists in a murine model of GVHD (52). Treatment with bambuterol – a prodrug of the selective β2-agonist terbutaline – significantly increased the number of MDSCs and Tregs while effector T cells were reduced and GVHD was ameliorated (52). All other mechanisms of action were excluded, and the central role of β2-AR was confirmed (52). Accordingly, in vitro cultivation of MDSCs is also increased by terbutaline (52). Terbutaline and other β2-agonists are used to treat asthma or COPD due to their bronchodilator effect. However, part of their beneficial role also might originate from MDSC generation.

2.2.7 TLR ligands

TLR4 signaling has been shown to play a crucial role in inducing MDSCs (83). In a study on acute type 1 diabetes using non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, an agonistic TLR4 monoclonal antibody was found to have a protective effect through the induction of MDSCs (84). Furthermore, the adoptive transfer of ex vivo bone marrow cells, stimulated with TLR4 antibody, into NOD mice suppressed acute type 1 diabetes induction as well (84). TLR4 antibody was shown to alter TLR4 signaling, including NFκB signaling, resulting in the downregulation of inflammatory genes and proteins (84). Furthermore, TLR2 activation by Pam2CSK4 was found to enhance immunosuppressive activity of M-MDSCs by upregulating iNOS and NO production, partly through STAT3 activation (85). Successful in vivo generation of MDSCs was also achieved with administration of complete freund’s adjuvant (CFA) containing heat-killed Mycobacterium (M.) tuberculosis in mice (86). Interestingly, a single dose of CFA increased the number of MDSCs but did not increase MDSC activity. However, a second dose of CFA was shown to increase MDSC activity as well. Here, M-MDSC accumulation and activation was found to be favored. M. tuberculosis was shown to play a pivotal role in the induction of MDSC accumulation by CFA, most likely through activation of TLR pathways such as TLR2 and TLR4 (86). Efficient MDSC boosting is also achieved using isolated membrane vesicles (MVs) of the common human gut bacterium P. pentosaceus via the TLR2 pathway (87). Alpdundar Bulut et al. observed upregulation of MDSC numbers, Arg-1 and IL-10 levels and M2-like macrophage differentiation in vitro as well as in several murine models modelling different inflammatory conditions (87). Isolated MV administration was shown to result in improved disease outcome (87). As the role of TLRs in MDSC induction is well documented, it appears to be a logical pharmacological target with potentially promising effects of TLR2/4 antibodies and/or agonists in promoting MDSCs and dampening inflammation (83).

2.2.8 PGE2/RIPK3 inhibitors

Increased PGE2 levels resulted in elevated activity and production of Arg-1, IL-6, VEGF, S100A9 and NO, while it also further inhibited RIPK3, creating a positive feedback loop for MDSC activation (31). Decreased receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) expression was found to be correlated with increased MDSC number and activity in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma, likely mediated by the NF-κB/COX-2/PGE2 axis (31, 78). Inhibition of RIPK3 with GSK872 was shown to prevent immune-mediated hepatitis (79). The authors showed that RIPK3 inhibition led to an increase in MDSCs number, which likely mediated the observed protective effect, as it was lost after MDSC depletion (79). RIPK3 knockdown resulted in increased MDSC recruitment in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma, which could be inhibited by a CXCR2 antagonist (78). All in all, these findings indicate that RIPK3 inhibition may be another promising pharmacological target to promote MDSC recruitment, likely via the NF-κB/COX-2/PGE2 and CXCR2 chemokine axis. Another possible MDSC activation mechanism linked to the NF-κB/COX-2/PGE2 axis may be the target of the PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4. Both EP2 and EP4 receptors may be promising targets for research by inducing them via their transcription factors or activating them with agonists. The study of Jontvedt Jorgensen et al. highlighted the potential of using this axis as a therapeutical target, as they demonstrated reduced MDSC numbers in murine models of tuberculosis after COX-2 inhibitor administration (56). Recently, we showed that a selective EP4 agonist could generate and activate MDSCs and dampen airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma (57).

2.2.9 Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib is a JAK inhibitor approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), among others. Sendo et al. showed that tofacitinib promoted MDSC expansion and ameliorated chronic inflammation in a murine model of RA-associated interstitial lung disease (ILD) (81). Previously, the same group showed the increase of the number of MDSCs and the following improvement of RA upon tofacitinib administration (82). Tofacitinib treatment was found to inhibit phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT5, while STAT3 levels remained constant which underlined the role of STAT3 in MDSC activation. The beneficial effect of tofacitinib in ILD may reveal the potential effect of JAK inhibitors on MDSC recruitment.

2.2.10 Quercetin

Quercetin, a natural substance found in many fruits and seeds, has already been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties in the context of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (110–112). Furthermore, Quercetin has been used as an anti-tumor therapy, due to its potential to induce tumor apoptosis and necrosis (59). Recently, Ma et al. showed a controversial correlation between MDSC regulation through quercetin and its anticancer properties (60). Quercetin treatment promoted PMN-MDSC expansion as well as its immunosuppressive activity in a murine model of prostate cancer (60). Mechanistically, quercetin binds to estrogen signaling receptors (ESR), especially ESR2, and exerts downstream phosphorylation of STAT3 in PMN-MDSCs and increased the expression of iNOS, NADPH oxidase and IDO. However, the same study showed that quercetin induces apoptosis in M-MDSCs through the estrogen signaling pathway (60). Nevertheless, quercetin may be a promising compound for the selective induction and activation of PMN-MDSCs through ESR/STAT3 signaling pathway, further supplementing the anti-inflammatory properties associated with quercetin.

2.2.11 Cannabidiol

Recently, Elliott et al. showed that administration of cannabidiol – a non-psychoactive cannabinoid – ameliorated autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice through the induction of MDSCs (88). Adoptive transfer of in vitro generated MDSCs, treated with CBD, was similarly found to improve encephalomyelitis, while MDSC depletion had the opposite effect. The same group demonstrated similar effects of CBD treatment in autoimmune hepatitis induced mice (89).

2.2.12 Clarithromycin

One study also revealed clarithromycin as a potential target for MDSC induction in vivo (90). Intraperitoneal and oral treatment with clarithromycin was shown to increase the number of MDSCs and prolong their survival in a murine model of LPS endotoxin shock and post-influenza pneumococcal pneumonia. In healthy humans, clarithromycin intake seems to enhance immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs (90).

2.2.13 Taurodeoxycholate

Chang, S. et al. indicated that TDCA – a taurine-conjugated bile acid – can be used to induce MDSCs (91). Here, administration of TDCA was found to improve survival in a mouse model of sepsis, likely through the generation and activation of MDSCs. Still, further research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

2.2.14 Cyclosporin A

Calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporin A or tacrolimus/FK506 are commonly used to treat autoimmune diseases and are administered to allograft recipients to prevent graft rejection. Calcineurin is released from its auto inhibitory loop upon T cell activation by antigen presentation and then dephosphorylates nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (53). NFAT migrates to the nucleus where it is responsible for the transcription of many pro-inflammatory genes, e.g. IL-2 (53). Besides NFAT, calcineurin inhibitors also target the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, and both these pathways play an important role in the myeloid cell lineage (53). The immunosuppressive properties of CsA could be linked to MDSC recruitment in vitro and in vivo (53). Daily treatment with CsA was found to increase MDSCs number, IDO and CXCR2 expression in a murine skin allograft transplantation model (53). Wang et al. suggested that the MDSC regulating effect of CsA is achieved by downregulation of NFATc1 (53). In addition, in skin grafted mice, the combined administration of GM-CSF and CsA was shown to increase MDSCs number and activity, by means of promoting iNOS expression (54). Therefore, calcineurin and NFAT appear to be interesting targets for MDSC regulation and induction.

2.2.15 Glucosamine

Glucosamine is an essential substrate for the glycosylation of proteins and lipids. Recently, glucosamine was shown to promote the generation of MDSCs from murine bone marrow cells in vitro as well as in mice treated for 14 days with intraperitoneal injections of glucosamine (58). Furthermore, glucosamine also increased MDSC activity confirmed by T cell suppression assays and increased levels of Arg-1 and iNOS expression (58). Further analysis showed this effect was likely mediated via the STAT3 and ERK1/2 pathways (58).

2.2.16 Glatirameracetat

GA has been found capable of promoting Tregs and Th2 lineage, while suppressing CD8+ T cell activity, and is therefore frequently used in relapsing-remitting MS (113). Recently, treatment with GA was demonstrated to increase the number and activity of MDSCs in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease with improving health condition (66). The underlying mechanism was shown to involve binding of GA to the paired immunoglobulin (Ig) -like receptor B (PIR-B) in mice, or to the human ortholog leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor-B (LILRB) in humans (66). This interaction inhibited the STAT1 pathway and resulted in an increased IL-10 and TGF-β secretion (66). The results of inhibiting LILRBs in mice tumor models support this finding, since a decrease in MDSC number and STAT6 phosphorylation, a shift of the macrophage balance towards M2-like macrophages as well as increased STAT1/JAK activity had been observed, which all oppose MDSC promotion (67). As the regulation of the myeloid lineage is a highly complex net of signals in which the role of LILRBs is not fully explained yet, further research is needed.

2.3 Potential pharmacological targets on MDSCs in cancer

MDSCs accumulate in cancer and promote invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis formation and reduce the effectiveness of anti-tumor immunity (1, 3). Considering the negative role of MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment, one of the main goals of cancer research has been to suppress both MDSCs number and activity (1, 3). Many pharmacological targets have already been identified, which were shown to be involved in modulating the number and activity of MDSCs in different types of cancer, and were able to be targeted with different compounds ( Table 2 ). As this review focusses on promoting MDSCs number and activity instead of inhibiting, in order to promote the anti-inflammatory immunity, the suggested MDSC-suppressing drugs are of course not of interest. However, the same targets that are used to suppress MDSCs in the context of the tumor microenvironment, might also be targeted in the complete opposite direction, in order to promote MDSCs in the context of potentially beneficial anti-inflammatory immunity. Several pharmacological targets that were manipulated to reduce the number and/or activity of MDSCs in the context of cancer, such as TLR4, β2-AR, EP4 and CXCR2, have already been described as potential targets for promoting the number and/or activity of MDSCs, as discussed above. For example, a β2-AR blocker, propranolol, was shown to reduce MDSC number and activity (20), while a β2-AR agonist, terbutaline, was shown to have the opposite effect (52). Similarly, the EP4 receptor antagonists, E7046 and YY001, were shown to reduce MDSC number and activity in the context of cancer (181, 182), while a EP4 receptor agonist, L-902,688, was shown to have the opposite effect in a murine model of asthma (57). However, there remain pharmacological targets of MDSC inhibition, which were identified in cancer research, that have so far not been studied in the context of MDSC promotion yet may provide efficient targets in novel anti-inflammatory therapies through generation and activation of these immune suppressive cells.

Table 2.

Potential pharmacological targets on MDSCs in cancer.

| Target | Potential pharmacological drug for cancer treatment | Effect of potential drug on MDSCs | Cancer type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A20 | A20-siRNA | Reduced number | Lymphoma Melanoma |

(114) |

| AMPKα | AMPKα inhibitor (dorsomorphin-compound), metformin | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Esophageal carcinoma Lung carcinoma Ovarian carcinoma |

(115–118) |

| Arginase-1, L-Arginine | L-Arginine, Arginase inhibitor (Nor-NOHA, CB-1158), ODC inhibitor (DFMO) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Melanoma Mammary carcinoma Ovarian carcinoma |

(119–123) |

| Aurora A | Aurora A inhibitor (alisertib) | Reduced number | Mammary carcinoma | (124) |

| Bcl-xL | Bcl-xL inhibitor (ABT-737) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma |

(125) |

| β2-AR/β3-AR | β-AR-blocker (propranolol), β3-AR-blocker (SR59230A) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Fibrosarcoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(20, 126–128) |

| Caspases | Ganoderic acid A, caspase 8 inhibitor (Z-IETD-FMK) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Lymphoma |

(129, 130) |

| CCL2/CCR2 | CCR2 inhibitor (RS-102895, RS-504393), CCL2 inhibitor (BHC, propagermanium) | Reduced number | Basal cell carcinoma Bladder carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Rhabdomyosarcoma |

(131–134) |

| CCL5/CCR5 | CCL5 Ab, CCR5 inhibitor (Met-RANTES, Maraviroc) | Reduced number | Lymphoma Malignant melanoma Mammary carcinoma |

(135–138) |

| CCRK | CCRK inhibitor | Reduced number | HCC | (139) |

| CD33 | CD33 Ab (BI 836858), CD33/CD3-bispecific T-cell engager (AMG 330, AMV564) | Reduced number | Leukemia Melanoma |

(140–142) |

| CD40 | CD40 Ab | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Gastric carcinoma Renal carcinoma |

(143–146) |

| c-Rel (member of NF-κB family) | c-Rel inhibitor (R96A) | Reduced number | Lymphoma Melanoma |

(147) |

| CSF-1/CSF-1 receptor | CSF-1 receptor inhibitor (GW2580, pexidartinib, PLX647, PLX5622, BLZ945) | Reduced number | Melanoma Neuroblastoma Prostate carcinoma |

(148–151) |

| CXCR1/2/CXCL1/2/5 | CXCR1/CXCR2 inhibitor (SX-682), CXCR2 inhibitor (SB-265610, benzocyclic sulfone derivatives) CXCR2 Ab | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Rhabdomyosarcoma |

(4, 41, 152–158) |

| CXCR4 | CXCR4 inhibitor (TFF2, plerixafor), poly polymerase inhibitor (olaparib), NAMPT inhibitor (FK866, MV87) | Reduced number | Colorectal carcinoma Fibrosarcoma Leukemia Mammary carcinoma Pancreatic carcinoma |

(159–164) |

| D1(-like) receptor | Dopamine, D1-like receptor agonist (SKF38393) | Reduced activity | HNSCC Lung carcinoma Melanoma Prostate carcinoma |

(165) |

| D2 receptor | D2 receptor agonist (cabergoline) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma | (166) |

| Dectin-1 | Dectin-1 agonist (WGP) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Lymphoma | (167) |

| Dkk1/β-catenin | Dkk1 Ab, galactosaminyltransferase | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Melanoma |

(168, 169) |

| DNA synthesis | Cytostatic drugs (gemcitabine, cisplatin, capecitabine, 5FU, lurbinectedin, 6-thioguanine, decitabine) | Reduced number | Bladder carcinoma Lymphoma Mammary carcinoma Myeloma Pancreatic carcinoma Thymoma |

(170–179) |

| ENTPD2 | ENTPD2 inhibitor | Reduced number | HCC | (180) |

| EP4 receptor | EP4 receptor antagonist (E7046, YY001) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Adenocarcinoma Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Prostate carcinoma |

(181, 182) |

| FAO | FAO inhibitor | Reduced activity | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma |

(183) |

| Fcγ receptor | Fc portion of monoclonal Ab (Cetuximab) | Reduced activity | HNSCC | (184) |

| FGL2 | FGL2 Ab | Reduced number | Glioma | (185) |

| G-CSF | G-CSF Ab, polyacetylenic glycoside (BP-E-F1) | Reduced number | Colorectal carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Sarcoma |

(18, 186, 187) |

| Glutaminase/Glutathione/glutathione synthase | ATRA, glutaminase antagonist (JHU083) | Reduced number | Colorectal carcinoma Lung carcinoma Melanoma Mammary carcinoma Sarcoma |

(188–195) |

| GM-CSF | GM-CSF Ab | Reduced number | HCC Mammary carcinoma Pancreatic carcinoma |

(152, 196–198) |

| HDAC | HDAC inhibitor (entinostat, valproic acid) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Renal cell carcinoma |

(199–201) |

| Histamine | Histamine antagonist (ranitidine), HDC | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colorectal carcinoma Lymphoma Mammary carcinoma |

(202, 203) |

| HMGB1 | HMGB1 inhibitor (ethyl pyruvate, glycyrrhizin) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(204) |

| HOXA1 | HOTAIRM1 | Reduced activity | Lung carcinoma | (205) |

| IDO | IDO inhibitor (1-MT, INCB023843, EOS200271), IDO-vaccine, gemcitabine, superoxide dismutase mimetic |

Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colorectal carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Pancreatic carcinoma |

(46, 206–212) |

| IFN-γ | IFN-γ Ab | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Leukemia Lymphoma Melanoma |

(213) |

| IL-1β | IL-1 receptor antagonist, anti-IL-1β Ab | Reduced number | Gastric carcinoma Melanoma Prostate carcinoma |

(27, 214, 215) |

| IL-4 | IL-4 receptor-α blockade with RNA aptamer | Reduced activity | Fibrosarcoma Mammary carcinoma |

(216, 217) |

| IL-6 | IL-6-neutralizing Ab/IL-6-silencing vector | Reduced number | HCC Lung carcinoma Malignant melanoma Prostate carcinoma |

(218–223) |

| IL-8 | IL-8 Ab (HuMax-IL8) | Reduced number | Mammary carcinoma | (224, 225) |

| IL-10 | IL-10 Ab, IL-10 receptor Ab | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Mammary carcinoma Ovarian carcinoma |

(226, 227) |

| IL-12 | IL-12 | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma |

(228, 229) |

| IL-13Rα2 | IL-13-PE (immunotoxin of IL-13 fused to the Pseudomonas exotoxin A) | Reduced number | HNSCC | (230) |

| IL-18 | IL-18 Ab (SK113AE4) | Reduced number | Melanoma Multiple myeloma Osteosarcoma |

(231–233) |

| IL-33 | IL-33 Ab | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Melanoma | (234) |

| iNOS | iNOS inhibitor (L-NIL, L-NAME) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Lymphoma Malignant melanoma Melanoma Thymoma |

(51, 235, 236) |

| IRF-4 | IL4 | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(237–239) |

| Jagged1/2 | Anti-Jagged1/2-blocking Ab (CTX014) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Melanoma Thymoma |

(240) |

| Kinases | Multikinase inhibitor (Sorafenib, Cabozantinib, BEZ235, Lenvatinib) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

HCC Malignant melanoma Renal cell carcinoma Urothelial carcinoma |

(197, 241) |

| Lactate | Anti-LDH Ab, ketogenic diet for glucose depletion | Reduced number | Pancreatic carcinoma | (242) |

| LILRB | LILRB antagonist | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma | 30352428 |

| LXR | LXR agonist (RGX-104, GW3965) | Reduced number | Colorectal carcinoma Lung carcinoma Melanoma Renal carcinoma Sarcoma Uterine carcinoma |

(243, 244) |

| MEK/BRAF | MEK inhibitor (trametinib, cobimetinib, GDC-0623), BRAF inhibitor (Vemurafenib) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(245–247) |

| MIF | MIF inhibitor (Sulforaphane) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Mammary carcinoma |

(248) |

| mTOR | mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin, AZD2014, OSU-53) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Ovarian carcinoma |

(249–252) |

| Myd88 | Myd88 inhibitor (IMG2005, TJ-M2010-5) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colorectal carcinoma | (253, 254) |

| NK1 receptor | Substance P | Reduced number | Mammary carcinoma | (255) |

| NOX2 | NOX2 inhibitor | Reduced activity | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Sarcoma Thymoma |

(44) |

| Osteactivin (DC-HIL) | Anti-DC-HIL Ab | Reduced activity | Colorectal carcinoma | (256) |

| P38 kinase | P38 inhibitor (LY2228820) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(257, 258) |

| PD-L1 | Anti-PD-L1 Ab | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma HNSCC Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Ovarian carcinoma |

(259–262) |

| PI3K | PI3K inhibitor (IPI-145, Alpelisib, quinic acid), Artemisinin | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma HNSCC Mammary carcinoma Melanoma |

(263–266) |

| PPARγ | PPARy agonists | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Lung carcinoma | (267, 268) |

| PNT | PNT inhibitor (CDDO-Me), PNT scavenger (MnTBAP) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Lung carcinoma Melanoma Thymoma |

(51, 269) |

| Phosphatidylserine | Anti-phosphatidylserine Ab (Bavituximab) | Reduced number | Mammary carcinoma Prostate carcinoma |

(270, 271) |

| PDE-5 | PDE-5 inhibitor (Sildenafil, Tadalafil), Paclitaxel | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Lymphoma Melanoma |

(235, 272–277) |

| PGE2 | Celecoxib, SC58125, SC58236 (cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors), Indomethancin (IND), EP2/4 antagonist | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Ovarian carcinoma Pancreatic carcinoma |

(41, 55, 278–283) |

| Rac | Rac inhibitor (EHT-1864) | Reduced number | Colitis-associated carcinoma | (284) |

| RLH | RLH ligand (polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) | Reduced activity | Pancreatic carcinoma | 31694706 |

| RORC1/RORγ | RORC1 inhibitor | Reduced number | Sarcoma | (285) |

| ROS | CDDO-Me (Triterpenoid), Doxorubicin | Reduced activity | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Renal cell carcinoma Sarcoma Thymoma |

(286, 287) |

| RTKs/BTK | RTK inhibitor (Sunitinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, sorafenib, UNC4241), BTK inhibitor (ibrutinib) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Cervical carcinoma Colon carcinoma HNSCC Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Pancreatic carcinoma Renal cell carcinoma |

(288–301) |

| S100A8/9/RAGE | anti-S100A8/9 Ab, S100A9 inhibitor (Tasquinimod), Anti-RAGE Ab | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Gastric carcinoma Lung carcinoma Lymphoma Mammary carcinoma Sarcoma |

(189, 302–309) |

| S1P | LCL521 | Reduced activity | HNSCC Sarcoma |

(310, 311) |

| SCARB1 | Synthethic high-density lipoprotein-like nanoparticles | Reduced activity | Melanoma | (312) |

| Semaphorin 4D | Semaphorin 4D Ab | Reduced number Reduced activity |

HNSCC | (313, 314) |

| SIRT1 via HIF-1α | SIRT1 activator (SRT1720), HIF-1α inhibitor (2-ME) | Reduced number | Lymphoma Melanoma |

(315) |

| STAT3 | STAT3 inhibitor (JSI-124, Stattic, AG490, Nifuroxazide, S3I, FLLL32, BBI608, napabucasin, quercetin), Sunitinib (TKI), Curcumin, Notch signaling blocker (selective CK2 inhibitor (TBCA), (γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI-IX, DAPT)) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Gastric carcinoma HCC HNSCC Lung carcinoma Lymphoma Mammary carcinoma Melanoma Ovarian carcinoma Pancreatic carcinoma Renal cell carcinoma Sarcoma |

(23, 32, 46, 60, 316–331) |

| STING | STING agonist | Reduced number | Colorectal carcinoma Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

(211, 332) |

| TGF-β1 | Anti-TGF-β1 Ab, TGF-β inhibitor (Pirfenidone) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

HCC Lung carcinoma Lymphoma Melanoma Renal cell carcinoma |

(309, 333) |

| TLR1/2 | TLR1/TLR2 agonist (synthethic bacterial lipoprotein), HSP70 ligand/blocker (A8 peptide) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Lymphoma Melanoma |

(334, 335) |

| TLR4 | TLR4-inducer (Asparagus polysaccharide, cinnamaldehyde) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Colorectal carcinoma |

(336, 337) |

| TLR7/8 | TLR7 agonist (imiqimod), TLR8 agonist (motolimod), TLR7/8 agonist (resiquimod) | Reduced number Reduced activity |

HNSCC Melanoma |

(338–342) |

| TLR9 | TLR9 agonist (CpG), TLR9-targeted STAT3siRNA | Reduced number Reduced activity |

Colon carcinoma Gastric carcinoma Prostatic carcinoma |

(343, 344) |

| TNF/TNFR2 | TNF Ab/inhibitor (XPro1595, etanercept, infliximab), TNFR2 inhibitor (TNFR2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, TNFR2-Fc fusion protein) | Reduced number | Colon carcinoma Lung carcinoma Sarcoma |

(345, 346) |

| TRAIL receptors | TRAIL receptor 2 agonist (DS-8273a) | Reduced number | Advanced stage solid tumors Lung carcinoma |

(347, 348) |

| Nrf2 | Nrf2 inducer (CDDO-Im) | Reduced activity | Lung carcinoma | (349) |

| VEGF/VEGF receptor | VEGF receptor inhibitor (SAR131675, pazopanib), VEGF Ab (bevacizumab) | Reduced number | Lung carcinoma Mammary carcinoma Prostate carcinoma |

(350–354) |

1-MT, 1-methyl-L-tryptophan; 2-ME, 2-Methoxyestradiol; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; Ab, Antibody; AR, Adrenergicreceptor; AMPKα, AMP-activated protein kinase alpha; ATRA, All-trans retinoic acid; Bcl-xL, B-cell lymphoma-extra large; BHC, Benzamide hydrochloride; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; BRAF, v-RAF murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B gene; CCL, Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CCR, C-C chemokine receptor; CCRK, Cell cycle-related kinase; CD, Cluster of differentiation; CDDO-Im, CDDO-Imidazolide; CDDO-Me, Methyl-2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9 (11)-dien-28-oate; CK2, Casein kinase 2; CSF-1, Colony stimulating factor-1; CXCL, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; DC-HIL, Dendritic cell heparan sulfate proteoglycan integrin-dependent ligand; DFMO, Difluoromethylornithine; Dkk1, Dickkopf-related protein 1; ENTPD2, Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2; ER, Endoplasmic reticulum; FAO, Fatty acid oxidation; FGL2, Fibrinogen-like protein 2; G-CSF, Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF, Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; HDAC, Histone deacetylase; HDC, Histamine dihydrochloride; HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; HMGB1, High-Mobility-Group Protein B1; HNSCC, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HOXA1, Homeobox protein Hox-A1; HOTAIRM1, HOXA transcript antisense RNA myeloid specific 1; IDO, Indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase; IFN, Interferon; IL, Interleukin; iNOS, Inducable nitric oxide synthases; IRF-4, Interferon-regulatory factor 4; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; LILRB, Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B; L-NAME, N(G) nitro L-arginine methyl ester; L-NIL, N6-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine; LXR, Liver-X nuclear receptor; MEK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MIF, Macrophage migration inhibitory factor; MnTBAP, Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; Myd88, Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NAMPT, Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NAPDH, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NK1, Neurokinin 1; Nor-NOHA, Nω-Hydroxy-nor-L-arginine; NOX2, NADPH oxidase 2; ODC, Ornithine decarboxylase; Nrf2, Transcription factor NF-E2-related factor-2; PDE-5, Phosphodiesterase-5; PD-L1, Programmed death-ligand 1; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PNT, Peroxynitrite; PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; RAGE, Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts; RANTES, Regulated upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and presumably Secreted; RLH, RIG-I-like helicase; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; siRNA, Small interfering RNA; RORC1/RORγ, Retinoic-acid-related orphan receptor; SCARB1, Scavenger receptor type B-1; SIRT1, Sirtuin (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog) 1; STAT3, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; STING, Stimulator of interferon genes; TBCA, Tetrabromocinnamic acid [(E)-3-(2,3,4,5-tetrabromophenyl)acrylic acid; TGF-β, Transforming growth factor β; TNF, Tumor necrose factor; WGP, Whole β-glucan particles; RTK, Receptor tyrosine kinase; TLR, Toll-like receptor; VEGFR, Vascular endothelial growth factor.

3 Discussion

Findings on the modulation of the generation, recruitment, and activation of MDSCs open the door to novel pharmacological approaches that can be used to dampen inflammation in a variety of diseases or conditions characterized by excessive and detrimental immune responses (such as autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, transplantation and GVHD). Taking all the mentioned mechanisms and the potential pharmacological targets into consideration, the in vitro generation of MDSCs combined with adoptive transfer (MDSC cell therapy) as well as the in vivo recruitment and activation of endogenous MDSCs seem to both be promising approaches. Nonetheless, cell therapies always bear additional risks, e.g. reaction of the immune system against transferred cells, and adverse side effects, and, as a result, need to be studied carefully before applying it to the clinical setting. Alternatively, the promotion of endogenous MDSCs could create safer, easier, and potentially equally or more efficient MDSC-targeted therapies in the future.

On the one hand, in vitro generation of MDSCs with the help of cytokines – like GM-CSF and IL-6 – or pharmacological compounds – such as PGE2 –, followed by adoptive transfer is an effective and increasingly established treatment in murine models of chronic inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, and allograft transplantation. Here, it is possible to circumvent the potential systemic side effects of unspecific pharmacological compounds and transfer a purified subset of immunosuppressive cells to dampen inflammation. On the other hand, efficient endogenous MDSC generation and activation was achieved with a double CFA injection containing M. tuberculosis or MVs through the TLR pathway, mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, dexamethasone, GA, EP4 receptor agonist as well as with other medications (48, 56, 57, 63, 64, 66, 67, 79, 81, 82, 84, 86, 87). Furthermore, many chemokines, and their receptors, have been identified to be involved in MDSC recruitment, with the most noteworthy chemokine being CXCR2, with its most important ligands CXCL1 and CXCL2. CXCR2 ligands can be used to regulate the migration of generated MDSCs to the site of interest, e.g. the intestines in Crohn’s disease, or the lungs of asthmatic patients. In this context, allografts could be coated with chemokine agonists to promote local MDSC accumulation - similar to vascular stents coated with anticoagulants and anti-proliferative drugs, like rapamycin. However, the in vivo generation of endogenous MDSCs may be a more straightforward therapy compared to MDSC cell therapy, which would ideally be accomplished with a selective drug and pharmacological targets, in order to reduce possible side effects as much as possible.

The safety of adoptively transferred MDSCs is not very well known and remains one of the primary challenges in bringing MDSC therapy to a clinical setting (355). Similarly, the safety of inducing endogenous MDSCs remains largely unknown. One concern may be the immature characteristic of MDSCs, which makes them susceptible to the induction of differentiation into other immune cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils or DCs, depending on specific microenvironmental cues. The negative role of MDSCs in the context of cancer also raises the following questions: Can MDSC inducing therapy only be applied in patients who are “certainly tumor-free”? And if so, how is it possible to identify this patient group? Or is the expected beneficial effect so great that the increased risk of metastasis can be accepted? Is there a way to inhibit MDSCs in undesired parts of the body? As the vast majority of studies on MDSCs are cancer-related and the systemic MDSC induction has been linked to tumor progression, metastasis and impaired survival, a method of local induction of MDSCs would be necessary to reduce the risk of MDSC-induced cancer progression as well as potential other side effects of systemic immunosuppression, e.g. opportunistic infections.

The increasing number of potential pharmacological targets that have been shown to be involved in modulating the number and activity of MDSCs provide significant number of opportunities for novel pharmacological approaches. Especially considering the potential targets, which were previously mainly studied in the context of cancer ( Table 2 ), to inhibit the MDSC response, where this effect may be reversed (e.g. changing from an agonist to antagonist or the other way around), in order to promote the MDSC response. The interest in the modulation of MDSC outside the context of cancer is also increasing, as the importance of MDSCs in many different immune-related pathological conditions is being unraveled (356). Furthermore, transplantation research has also increased its attention towards MDSC immunomodulation as a promising candidate to increase tolerance and improve transplant outcome (357). Thus, the pharmacological approaches which can be applied in MDSC modulation, as discussed in this review, may provide novel opportunities in the future of tolerance-inducing agents in the context of transplantation.

Taken together, there are many different promising pharmacological targets to generate and activate MDSCs, and their beneficial potential in certain pathological conditions has been established in animal studies. Therefore, MDSC therapies may prove to be effective alternatives to other immunosuppressive therapies. The selective harnessing of regulatory immune cells, here expanding suppressive activity of MDSCs on T cells, may bring an advanced possibility to protect, limit or ameliorate the initiation or progression of autoimmunity, inflammation, transplant rejection or GVHD, promote inflammation resolution and transplantation tolerance and pave the way toward precise medical therapy in inflammation/autoimmunity/transplant medicine.

Author contributions

SK conceptualized the review. CG, CH, AD and SK contributed to the original draft. CG and SK contributed to revising and final approval of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the Universities Giessen Marburg Lung Center (UGMLC) and the German Center for Lung Disease (DZL German Lung Center, no. 82DZL005B2), the Foundation for Pathobiochemistry and Molecular Diagnostics grant and the ƒortüne program of the University of Tuebingen (# 2458-0-0, # 2606-0-0) for SK. Open access was funded by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Philipps-Universität Marburg with support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) and the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Tübingen.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

- 1. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(3):162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bronte V, Apolloni E, Cabrelle A, Ronca R, Serafini P, Zamboni P, et al. Identification of a Cd11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/Cd31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing Cd8(+) T cells. Blood (2000) 96(12):3838–46. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.12.3838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Rev Cancer (2013) 13(10):739–52. doi: 10.1038/nrc3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun L, Clavijo PE, Robbins Y, Patel P, Friedman J, Greene S, et al. Inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cell trafficking enhances T cell immunotherapy. JCI Insight (2019) 4(7):e126853. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albeituni SH, Ding C, Yan J. Hampering immune suppressors: Therapeutic targeting of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer J (2013) 19(6):490–501. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorhoi A, Du Plessis N. Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in chronic infections. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1895. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cripps JG, Gorham JD. Mdsc in autoimmunity. Int Immunopharmacol (2011) 11(7):789–93. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deshane JS, Redden DT, Zeng M, Spell ML, Zmijewski JW, Anderson JT, et al. Subsets of airway myeloid-derived regulatory cells distinguish mild asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2015) 135(2):413–24 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clements VK, Long T, Long R, Figley C, Smith DMC, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Frontline science: High fat diet and leptin promote tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukoc Biol (2018) 103(3):395–407. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4HI0517-210R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pawelec G, Verschoor CP, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Not only in tumor immunity. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1099. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun (2016) 7:12150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Condamine T, Dominguez GA, Youn JI, Kossenkov AV, Mony S, Alicea-Torres K, et al. Lectin-type oxidized ldl receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci Immunol (2016) 1(2):aaf8943. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alshetaiwi H, Pervolarakis N, McIntyre LL, Ma D, Nguyen Q, Rath JA, et al. Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci Immunol (2020) 5(44):eaay6017. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katzenelenbogen Y, Sheban F, Yalin A, Yofe I, Svetlichnyy D, Jaitin DA, et al. Coupled scrna-seq and intracellular protein activity reveal an immunosuppressive role of Trem2 in cancer. Cell (2020) 182(4):872–85 e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Condamine T, Mastio J, Gabrilovich DI. Transcriptional regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukoc Biol (2015) 98(6):913–22. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4RI0515-204R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thorn M, Guha P, Cunetta M, Espat NJ, Miller G, Junghans RP, et al. Tumor-associated gm-csf overexpression induces immunoinhibitory molecules Via Stat3 in myeloid-suppressor cells infiltrating liver metastases. Cancer Gene Ther (2016) 23(6):188–98. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peng D, Tanikawa T, Li W, Zhao L, Vatan L, Szeliga W, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells endow stem-like qualities to breast cancer cells through Il6/Stat3 and No/Notch cross-talk signaling. Cancer Res (2016) 76(11):3156–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li W, Zhang X, Chen Y, Xie Y, Liu J, Feng Q, et al. G-Csf is a key modulator of mdsc and could be a potential therapeutic target in colitis-associated colorectal cancers. Protein Cell (2016) 7(2):130–40. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0237-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Waight JD, Netherby C, Hensen ML, Miller A, Hu Q, Liu S, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell development is regulated by a Stat/Irf-8 axis. J Clin Invest (2013) 123(10):4464–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI68189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mohammadpour H, MacDonald CR, Qiao G, Chen M, Dong B, Hylander BL, et al. Beta2 adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling regulates the immunosuppressive potential of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest (2019) 129(12):5537–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI129502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreira D, Adamus T, Zhao X, Su YL, Zhang Z, White SV, et al. Stat3 inhibition combined with cpg immunostimulation activates antitumor immunity to eradicate genetically distinct castration-resistant prostate cancers. Clin Cancer Res (2018) 24(23):5948–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hellsten R, Lilljebjorn L, Johansson M, Leandersson K, Bjartell A. The Stat3 inhibitor galiellalactone inhibits the generation of mdsc-like monocytes by prostate cancer cells and decreases immunosuppressive and tumorigenic factors. Prostate (2019) 79(14):1611–21. doi: 10.1002/pros.23885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guha P, Gardell J, Darpolor J, Cunetta M, Lima M, Miller G, et al. Stat3 inhibition induces bax-dependent apoptosis in liver tumor myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncogene (2019) 38(4):533–48. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0449-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mundy-Bosse BL, Lesinski GB, Jaime-Ramirez AC, Benninger K, Khan M, Kuppusamy P, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell inhibition of the ifn response in tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res (2011) 71(15):5101–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schroder M, Krotschel M, Conrad L, Naumann SK, Bachran C, Rolfe A, et al. Genetic screen in myeloid cells identifies tnf-alpha autocrine secretion as a factor increasing mdsc suppressive activity Via Nos2 up-regulation. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):13399. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31674-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Porta C, Consonni FM, Morlacchi S, Sangaletti S, Bleve A, Totaro MG, et al. Tumor-derived prostaglandin E2 promotes P50 nf-Kappab-Dependent differentiation of monocytic mdscs. Cancer Res (2020) 80(13):2874–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell (2008) 14(5):408–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hu CE, Gan J, Zhang RD, Cheng YR, Huang GJ. Up-regulated myeloid-derived suppressor cell contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development by impairing dendritic cell function. Scand J Gastroenterol (2011) 46(2):156–64. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.516450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tannenbaum CS, Rayman PA, Pavicic PG, Kim JS, Wei W, Polefko A, et al. Mediators of inflammation-driven expansion, trafficking, and function of tumor-infiltrating mdscs. Cancer Immunol Res (2019) 7(10):1687–99. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi JN, Sun EG, Cho SH. Il-12 enhances immune response by modulation of myeloid derived suppressor cells in tumor microenvironment. Chonnam Med J (2019) 55(1):31–9. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2019.55.1.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yan G, Zhao H, Zhang Q, Zhou Y, Wu L, Lei J, et al. A Ripk3-Pge2 circuit mediates myeloid-derived suppressor cell-potentiated colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res (2018) 78(19):5586–99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng P, Kumar V, Liu H, Youn JI, Fishman M, Sherman S, et al. Effects of notch signaling on regulation of myeloid cell differentiation in cancer. Cancer Res (2014) 74(1):141–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morello S, Miele L. Targeting the adenosine A2b receptor in the tumor microenvironment overcomes local immunosuppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology (2014) 3:e27989. doi: 10.4161/onci.27989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tcyganov E, Mastio J, Chen E, Gabrilovich DI. Plasticity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Curr Opin Immunol (2018) 51:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li BH, Garstka MA, Li ZF. Chemokines and their receptors promoting the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells into the tumor. Mol Immunol (2020) 117:201–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hsu YL, Yen MC, Chang WA, Tsai PH, Pan YC, Liao SH, et al. Cxcl17-derived Cd11b(+)Gr-1(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to lung metastasis of breast cancer through platelet-derived growth factor-bb. Breast Cancer Res (2019) 21(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1114-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oliveira AC, Fu C, Lu Y, Williams MA, Pi L, Brantly ML, et al. Chemokine signaling axis between endothelial and myeloid cells regulates development of pulmonary hypertension associated with pulmonary fibrosis and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2019) 317(4):L434–L44. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00156.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taki M, Abiko K, Baba T, Hamanishi J, Yamaguchi K, Murakami R, et al. Snail promotes ovarian cancer progression by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells Via Cxcr2 ligand upregulation. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1685. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03966-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neamah WH, Singh NP, Alghetaa H, Abdulla OA, Chatterjee S, Busbee PB, et al. Ahr activation leads to massive mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells with immunosuppressive activity through regulation of Cxcr2 and microrna mir-150-5p and mir-543-3p that target anti-inflammatory genes. J Immunol (2019) 203(7):1830–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang C, Wang S, Li J, Zhang W, Zheng L, Yang C, et al. The mtor signal regulates myeloid-derived suppressor cells differentiation and immunosuppressive function in acute kidney injury. Cell Death Dis (2017) 8(3):e2695. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Katoh H, Wang D, Daikoku T, Sun H, Dey SK, Dubois RN. Cxcr2-expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential to promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell (2013) 24(5):631–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Han X, Shi H, Sun Y, Shang C, Luan T, Wang D, et al. Cxcr2 expression on granulocyte and macrophage progenitors under tumor conditions contributes to Mo-mdsc generation Via Sap18/Erk/Stat3. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10(8):598. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1837-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ohl K, Tenbrock K. Reactive oxygen species as regulators of mdsc-mediated immune suppression. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2499. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]