Abstract

Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) are important therapeutic targets, playing a crucial role in the regulation of many cellular processes and being linked to many diseases. Yet, there is still much to be understood regarding their functions and the biological pathways in which they are involved, as well as on the structural requirements that could drive the development of selective modulators of PRMT activity. Here we report a deconstruction–reconstruction approach that, starting from a series of type I PRMT inhibitors previously identified by us, allowed for the identification of potent and selective inhibitors of PRMT4, which regardless of the low cell permeability show an evident reduction of arginine methylation levels in MCF7 cells and a marked reduction of proliferation. We also report crystal structures with various PRMTs supporting the observed specificity and selectivity.

Introduction

The post-translational methylation of the guanidinium group of arginine residues of histone and nonhistone proteins by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) plays a fundamental role in many key cellular functions, including gene regulation, signal transduction, RNA processing, and DNA repair.1−7 On the other hand, the aberrant expression of PRMTs or the dysregulation of PRMT activity is associated with several diseases, including many types of cancer.1,3,5,8−11

On the basis of their methylation products, monomethylarginine (Rme1),12 asymmetric dimethylarginine (Rme2a), or symmetric dimethylarginine (Rme2s),1,8 the nine PRMT isoforms identified in human genome to date are classified into three subfamilies:13 type I PRMTs (PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, PRMT4, PRMT6, and PRMT8), catalyzing mono- and asymmetric dimethylation, type II PRMTs (PRMT5 and PRMT9), catalyzing mono- and symmetric dimethylation, and PRMT7, the sole member of type III, which only catalyzes the formation of Rme1.14 Arginine methylation and PRMTs have been associated with a variety of diseases, including cancer and neurological and inflammatory diseases.13

Also, viral proteins from several viruses are methylated by PRMTs,15−19 including SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein, the methylation of which at residues R95 and R177 is crucial for viral replication.20 Indeed, over the past 15 years the medicinal chemistry community has paid a growing attention to PRMTs,11,13,21−26 in particular to PRMT5 (with a few inhibitors in clinical trials)21,27−33 and to type I enzymes (both pan-type I22,34−36 and selective24,37−45).

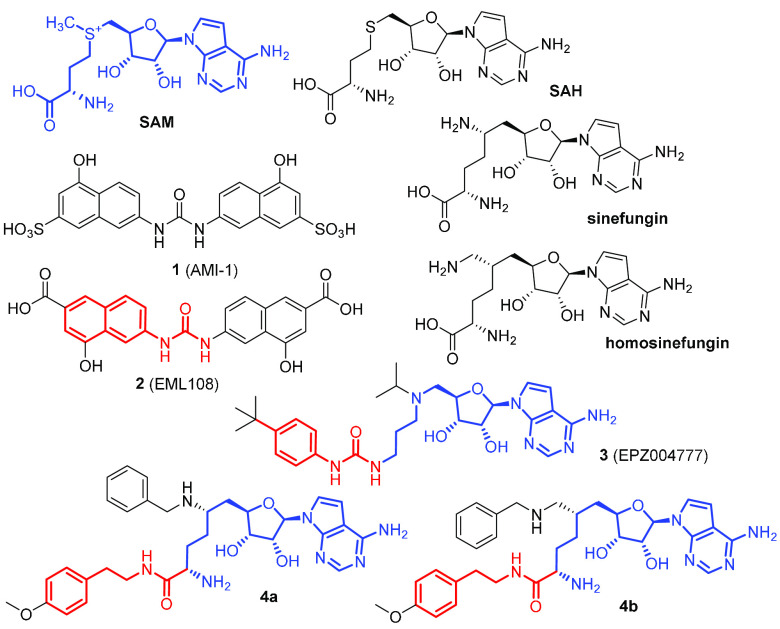

In our early studies in the field,46 we developed a series of type I PRMT inhibitors starting from 7,7′-(carbonylbis(azanediyl))bis(4-hydroxynaphthalene-2-sulfonic acid) 1 (AMI-1, Chart 1). In particular, the isosteric bis-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid 2 (EML108, Chart 1) was able to prevent arginine methylation of cellular proteins in whole-cell assays, with activities comparable to AMI-1 (or even better than it). Moreover, compound 2 and its derivatives were found to be selective for arginine methyltransferases and essentially inactive against the lysine methyltransferase SET7/9.47

Chart 1. Structure of the Cofactor SAM, the Byproduct SAH, and Representative Inhibitors of PRMTsa.

a Similar moieties (see text) are depicted in the same blue or red color.

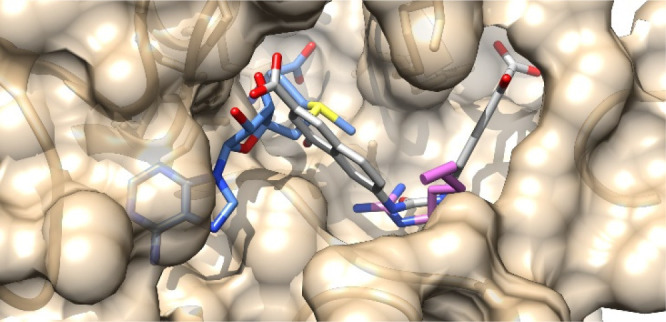

On the basis of molecular modeling studies (docking and binding mode analysis, confirmed by structure-based 3-D QSAR models),46,48 we found that such inhibitors, as well AMI-1, bind PRMT1 (at that time chosen as representative of type I enzymes) between the S-adenosine-l-methionine (SAM) cofactor and substrate arginine binding sites without entirely occupying them. In particular, the binding site of the Arg guanidine group as well as both the adenosine and the methionine ends of the SAM binding pocket seems to be largely unoccupied (Figure 1). This is consistent with previously reported kinetics experiments.49 Therefore, a further decoration of the scaffold of compound 2 aimed to better occupy these pockets could, in principle, result in a gain of affinity.

Figure 1.

Predicted binding mode of 2 (EML108, in sticks, carbon atoms in gray) into PRMT1 (tan) catalytic site (PDB ID: 1OR8).46−48 SAM is depicted in cornflower blue, histone Arg in orchid (for clarity, only the side chain is shown).

Soon after our studies, Epizyme reported on the development of compound 3 (EPZ004777, Chart 1), a potent and selective inhibitor of lysine methyltransferase DOT1L based on the chemical structures of SAM and the corresponding product (S-adenosylhomocysteine, SAH) of DOT1L catalysis reaction as well as on its mechanism.50 We were intrigued by the structural similarity between the 4′-alkylphenylurea in this compound and the N-naphthylurea moiety of compound 2. Although showing a remarkable selectivity against other histone methyltransferases, compound 3 was confirmed to inhibit also PRMT5 and PRMT7 (with IC50 values of 0.52 and 7.5 μM, respectively).51 Similarly, the amidic derivatives 4a and 4b (Chart 1) of the nonspecific SAM-dependent enzyme inhibitors sinefungin and 6′-homosinefungin were recently reported as PRMT inhibitors, with IC50 values against PRMT4 of 43 nM and 1.9 μM, respectively.52 Again, just like the 4′-alkylphenylurea in compound 3, the N-phenethylamide portion in compounds 4a and 4b resembles the naphthylurea (in red in Chart 1) and mimics the lysine substrate covalently linked to a SAM-like moiety (in blue in Chart 1). It is noteworthy that 4b inhibits modestly (IC50 = 1.9 μM) but selectively PRMT4 with no appreciable activity on other PRMTs. On the other hand, 4a, which differs from 4b only by the methylene group bridging the C5 position of the hexanamide with the benzylamine nitrogen, shows a dramatic increase of potency against PRMT4 (IC50 of 43 nM) but maintains a definite activity against type II and III PRMTs. This supports the hypothesis that the distance between the pharmacophoric moieties that are correlated with PRMTs inhibition plays a key role in potency and selectivity.

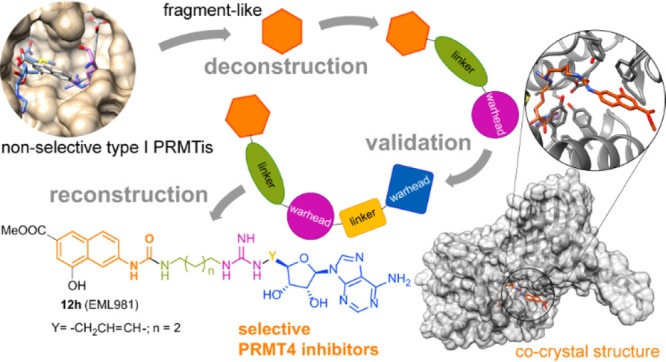

Based on these considerations and pursuing our interest in the identification of potent and selective PRMT inhibitors,7,44,46,47,53−59 we resolved to reduce the structure of 2 to a single N-naphthylurea moiety and to grow it into a more complex structure incorporating warheads able to better bind the above-mentioned available pockets. The derivatives resulting from this design concept (Figure 2) were screened using in vitro biochemical assays to study their potency and selectivity in the inhibition of the various PRMTs. Herein, we report the design and synthesis of such compounds and the identification of 12h (EML981) as a potent and selective inhibitor of PRMT4/CARM1. We also report cocrystallization studies supporting the observed specificity and selectivity of compound 12h.

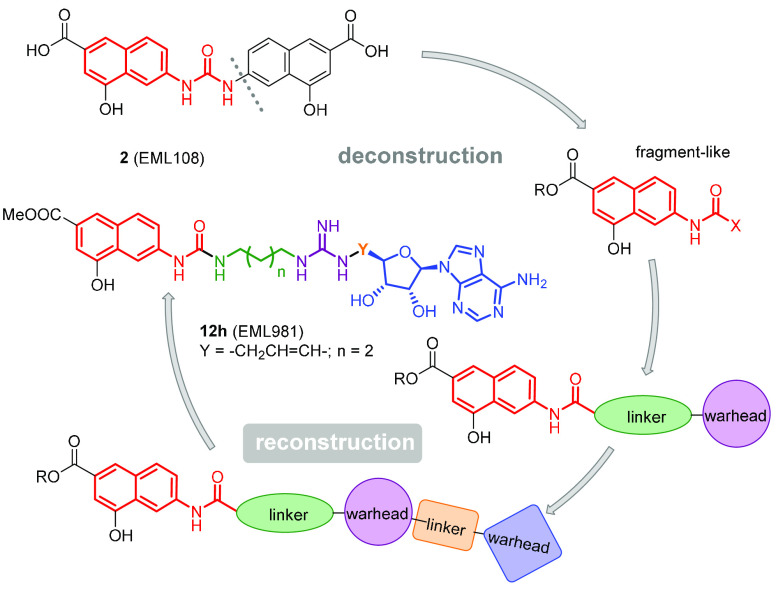

Figure 2.

Flowchart of our design strategy.

Results and Discussion

Design Strategy

Our previous molecular modeling studies46,48 performed on compound 2 and its derivatives had suggested a binding mode between the cofactor and substrate binding pockets, without fully occupying them. In particular, one of the two 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic moieties partially occupies the substrate binding site without establishing interactions with the two conserved glutamate residues of the so-called “double-E loop” critical for chelating and orienting the Arg guanidine group.60 On the other hand, the binding of the second 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic moiety seems to leave the SAM binding pocket largely unoccupied (Figure 1). Therefore, we decided to base our design strategy, schematically depicted in Figure 2, on a “deconstruction–reconstruction” approach that has gained traction in recent years.61−63 The concept underlying this approach is simple: since traditional fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) combines fragments into a final molecule,64 it is typically possible to deconstruct a known ligand to obtain a relatively smaller fragment library.65,66 Therefore, we deconstructed our previously identified PRMTs inhibitors and decided to extend the resulting naphthylamide fragment using a growing approach.67

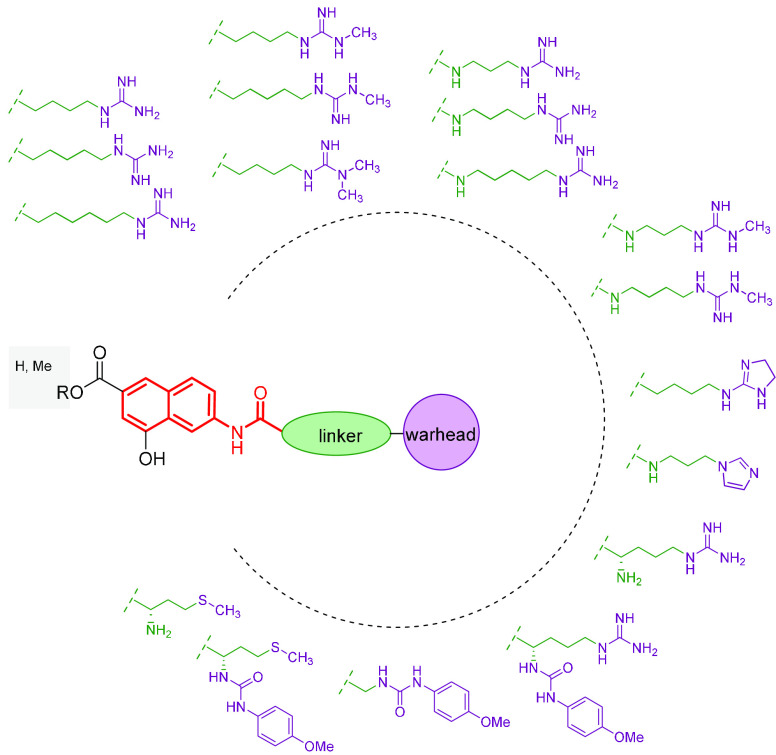

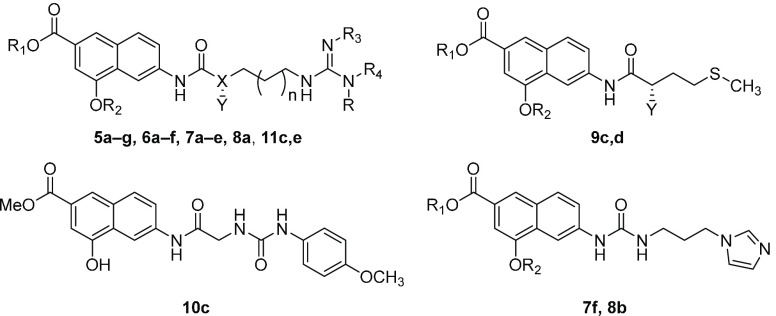

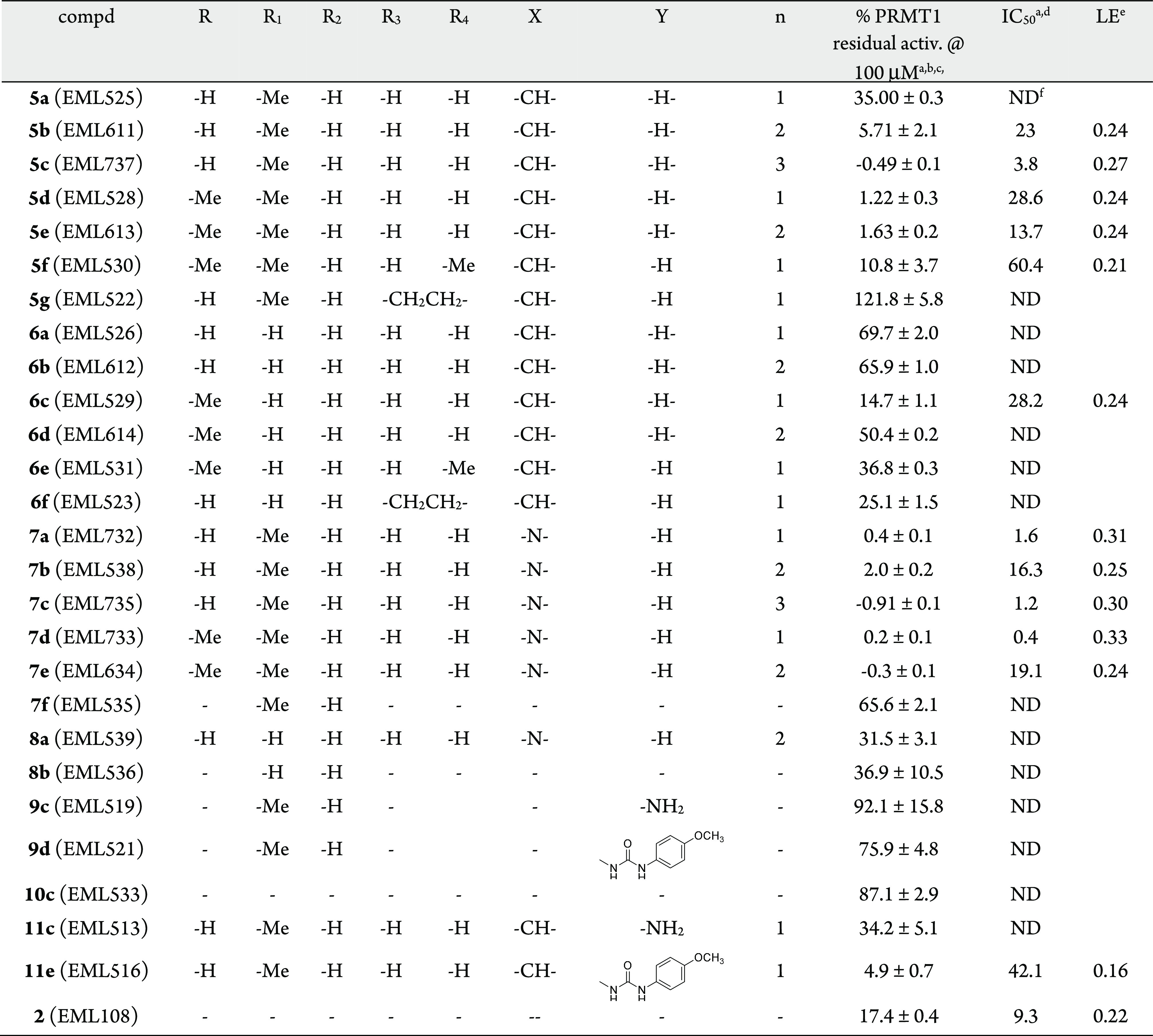

We then designed a series of derivatives (Figure 3) incorporating the 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic group bridged by an amide or urea group with an arginine surrogate (arginine mimetic moiety). The effect of the introduction of a methionine was also explored. The compounds (5–11, Table 1) were synthesized and, at first, analyzed for known classes of assay interference compounds.68 All derivatives were not recognized as PAINS according to the SwissADME web tool (http://www.swissadme.ch),69 the Free ADME-Tox Filtering Tool (FAF-Drugs4) program (http://fafdrugs4.mti.univ-paris-diderot.fr/),70 and the “False Positive Remover” software (http://www.cbligand.org/PAINS/)71 nor as aggregators according to the software “Aggregator Advisor” (http://advisor.bkslab.org/).72

Figure 3.

Compounds designed for the first reconstruction step.

Table 1. Inhibitory Activities of Compounds 5–11 against hPRMT1.

AlphaLISA was used for both fixed dose and IC50 determinations against human recombinant PRMT1 (0.9 nM, final concentration). Histone H4 (1–21) peptide, biotinylated (100 nM, final concentration), and SAM (2 μM, final concentration) were used as substrate and cofactor, respectively.

Compounds were tested at a 100 μM fixed concentration.

Enzyme residual activity percentage calculated with respect to DMSO.

Compounds were tested in 10-concentration IC50 mode with threefold serial dilutions starting at 100 μM. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0) for IC50 curve fitting.

Ligand efficiency (LE) calculated from IC50 as a surrogate for KD.

ND, not determined.

Then, we resolved to determine their effect on the catalytic activity of human recombinant PRMT1, chosen as representative of class I PRMTs. To this aim, we used an in-house peptide-based AlphaLISA assay measuring the levels of H4R3me, developed by us (see the Experimental Section) because the commercially available homogeneous assay kit (BPS, #52054) did not work properly in our hands and gave an unacceptably narrow assay window. All the compounds were tested at a fixed concentration of 100 μM using 2 (EML108) as the reference compound. Then, the compounds that displayed a greater than 85% inhibition (residual enzyme activity <15%) were selected, and the corresponding IC50 values were determined (Table 1).

Overall, the results show that one of the two 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic groups could be efficiently replaced by an arginine-mimetic group moiety. This result is consistent with our initial assumption that our PRMTs inhibitors bind PRMT1 between the SAM and arginine binding sites without fully occupying them.

Structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis of tested compounds suggested that, in general, ester derivatives are better than the corresponding acids (for example, compare inhibiting activities of compounds 5a, 5b, 5d, and 5e with those of 6a–6d, respectively) and urea derivatives are more active (compare 7a–7d with 5a–5d, respectively) or comparable (7e vs 5e) to their amide counterparts. The presence of a single methyl on one of the terminal nitrogen atoms of the guanidine group also improves the activity in the amide series (compare 5d and 5e with 5a and 5b, respectively), whereas this is less evident in the urea series (compare 7d and 7e with 7a and 7b, respectively) and in carboxylic acids with respect to ester derivatives. On the contrary, the introduction of a second methyl group on the same nitrogen atom leads to a decrease of inhibiting activity (compare 5f with 5d). When both terminal nitrogens are substituted and blocked into an imidazoline ring (as in the case of compounds 5g and 6f), the inhibiting activity is even lower. Similarly, in the urea series the replacement of the guanidine group with an imidazole leads to the loss of activity (compare 7f with 7a). Regarding the effect of the methylene linker length, in the amide series the activity seems to increase with the number of carbon atoms of the linker (see, for example, the activities of compounds 5a–5c and 7a–7c) at least for ester derivatives, whereas for the corresponding acids the effect is less evident (6a vs 6b) or opposite (6c vs 6d). On the other hand, an “odd/even effect”73−75 seems to occur in the urea series, where an even number of carbon atoms in the alkyl spacer (as in the case of 7b and 7e, n = 2, total carbon atoms in the linker = 4) is less favorable than an odd number (as in the case of 7a and 7d—n = 1, total carbon atoms in the linker = 3—or 7c—n = 3, total carbon atoms in the linker = 5).

The introduction of an α-amino group (as in derivative 11c) does not improve the activity of the compound. On the contrary, the introduction at the same position of a p-methoxyphenylurea resulted in compounds with improved inhibiting capability, even if compared to the α-unsubstituted compounds (compare 11e with 11c and 5a). Last, the removal of the guanidine group is detrimental for the inhibiting activity and cannot be compensated by the sole presence of a p-methoxyphenylurea in the α position relative to the amide carbonyl group. In fact, both the methionine and glycine derivatives 9c, 9d, and 10c are inactive or scarcely active. Noteworthy, the effects appear to be additive. In fact, the ester derivative of the urea series, with three carbon atoms in the linker and a methyl group on the terminal nitrogen of the guanidine, namely compound 7d, is the most active and the most efficient ligand among the tested compounds, showing a submicromolar IC50 value (0.4 μM) and a ligand efficiency76 value (LE) of 0.33.

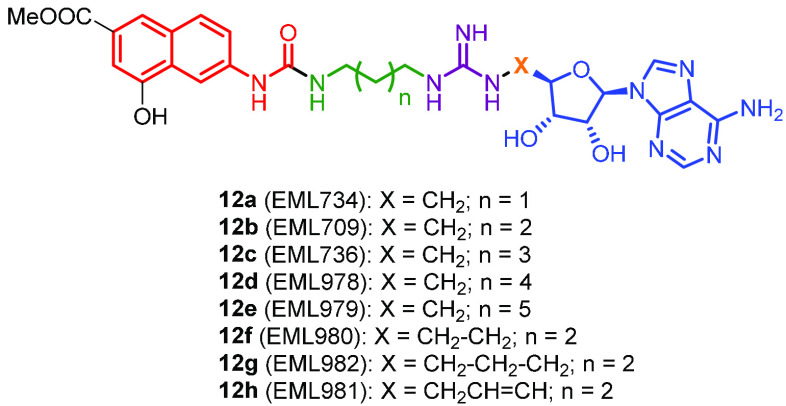

Therefore, on the basis of the structure–activity relationships, we resolved to select the scaffold of the latter compound for the second step of the construction of our multisubstrate ligands. Considering the effect of the linker length on the activity against PRMT1 and also with the aim to explore a possible difference among various PRMTs, first we designed and synthesized three derivatives in which the linker between the urea and the guanidine groups included three, four, or five carbon atoms and the adenosine moiety was connected to a guanidine ω-nitrogen through a methylene group (Figure 4, derivatives 12a, 12b, and 12c, respectively).

Figure 4.

Compounds designed for the second fragment-growing step.

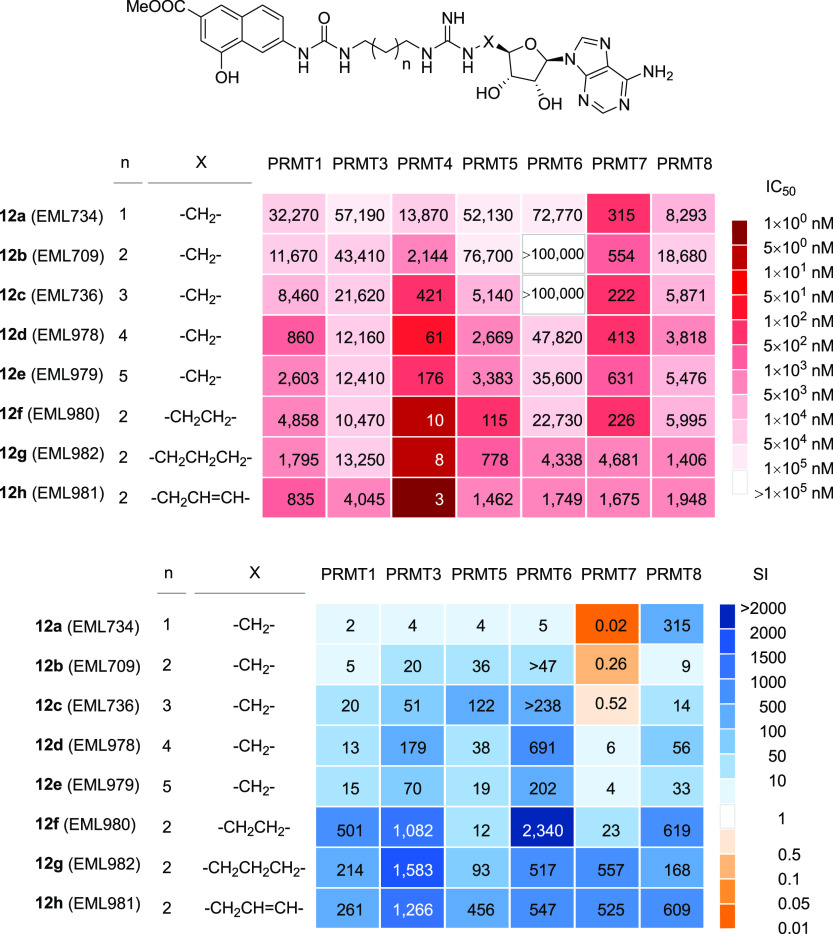

As in the case of derivatives 5–11, we first determined the effect of compounds 12a–12c on the catalytic activity of human recombinant PRMT1, using our AlphaScreen assay. As expected, the introduction of the adenosine moiety increased the inhibiting activity against PRMT1 as all the derivatives showed IC50 values in the submicromolar range (Table 2, values in parentheses). Prompted by these results, we next used a secondary screening approach to profile the activity of the compounds against a panel of four PRMTs (PRMT1, PRMT3, PRMT4, and PRMT5) using a radioisotope-based filter-binding assay. If compared to the results obtained from the AlphaScreen assay, in the more sensitive radioisotope-based assay compounds 12a–12c were found to be less potent inhibitors of PRMT1 activity, but the IC50 values were still in the micromolar range (Table 2). Noteworthy, they were appreciably more active against PRMT4. We also noticed that the distance between the methyl 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety and the arginine-mimetic group significantly affects the inhibition of PRMT4 activity, whereas it has no significant effect on the activity of PRMT5 and only a moderate effect on PRMT1 and PRMT3. In fact, compound 12c exhibits a submicromolar activity (IC50 = 0.42 μM) only against PRMT4, with a selectivity for the latter ranging from 20-fold (over PRMT1; Table 2) to 122-fold (over PRMT5; Table 2). Based on these outcomes, we speculated that more potent and selective PRMT4 inhibitors could be generated by modulating the distance between the three pharmacophoric moieties. Therefore, we synthesized a second set of derivatives (compounds 12d–12h, Figure 4) in which the distance between the 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety and the guanidine group (compound 12d and 12e) or the distance between the guanidine group and the adenosine moiety (compounds 12f–12h) was further increased. Again, all compounds 12a–12h were analyzed for known classes of assay interference compounds68 and were not recognized as PAINS nor as aggregators. The compounds were then tested against a wider panel of PRMTs (including also PRMT6, PRMT7, and PRMT8) using the same radioisotope-based filter-binding assay. The results are reported in Table 2 and summarized as heatmaps in Figure 5. As expected, increasing the linker length between the 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate and the guanidine group up to a total of four or five carbon atoms yielded a gain in the inhibitory activity against PRMT4, although moderate (6.2-fold for 12d and 2.4-fold for 12e). However, a similar gain was observed also against PRMT1, PRMT5, and PRMT6 (e.g., 9.8-fold and 3.2-fold against PRMT1 and 19.8-fold and 15.2-fold against PRMT5, for 12d and 12e, respectively), with a consequent reduction of selectivity. A lesser effect was observed against PRMT8, and a slight decrease of inhibiting activity was observed against PRMT7. On the other hand, we were pleased to find out that compounds 12f–12h, featuring an increased distance between the guanidine group and the adenosine moiety, showed a remarkable and selective increase in potency against PRMT4, with a consistent gain in selectivity over six other human PRMTs. In particular, compound 12h (EML981) showed a 668-fold gain in potency over its shorter counterpart 12b and 261- to 1266-fold selectivity over the other PRMTs.

Table 2. Inhibitory Activities of Compounds 12a–12h against Various PRMTs.

| IC50 (μM)a,b |

selectivity index for PRMT4 vs other

PRMTsc |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | PRMT1 | PRMT3 | PRMT4 | PRMT5 | PRMT6 | PRMT7 | PRMT8 | PRMT1 | PRMT3 | PRMT5 | PRMT6 | PRMT7 | PRMT8 | LEd |

| 12a | 32.27 (0.5)e | 57.19 | 13.84 | 52.13 | 72.77 | 0.32 | 8.29 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.14 |

| 12b | 11.67 (0.43)e | 43.41 | 2.14 | 76.7 | >100 | 0.55 | 18.68 | 5 | 20 | 36 | >47 | 0.26 | 9 | 0.18 |

| 12c | 8.46 (0.3)e | 21.26 | 0.42 | 51.41 | >100 | 0.22 | 5.87 | 20 | 51 | 122 | >238 | 0.52 | 14 | 0.19 |

| 12d | 0.86 | 12.2 | 0.068 | 2.6 | 47 | 0.41 | 3.82 | 13 | 179 | 38 | 691 | 6 | 56 | 0.21 |

| 12e | 2.6 | 12.4 | 0.176 | 3.38 | 35.6 | 0.631 | 5.84 | 15 | 70 | 19 | 202 | 4 | 33 | 0.20 |

| 12f | 4.86 | 10.5 | 0.0097 | 0.115 | 22.7 | 0.226 | 6 | 501 | 1082 | 12 | 2340 | 23 | 619 | 0.24 |

| 12g | 1.80 | 13.3 | 0.0084 | 0.778 | 4.34 | 4.68 | 1.41 | 214 | 1583 | 93 | 517 | 557 | 168 | 0.24 |

| 12h | 0.835 | 4.05 | 0.0032 | 1.46 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.95 | 261 | 1266 | 456 | 547 | 525 | 609 | 0.25 |

Compounds were tested in 10-concentration IC50 mode with threefold serial dilutions starting at 100 μM. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0) for IC50 curve fitting.

Unless differently indicated, the values were obtained in a radioisotope-based filter assay, using 5 μM histone H4 (for PRMT1, PRMT3, and PRMT8), histone H3 (for PRMT4), histone H2A (for PRMT5), or GST-GAR (for PRMT6 and PRMT7) as the substrate and S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-3H]methionine (1 μM) as methyl donor.

Selectivity index for PRMT4 over the specified PRMT, calculated as the ratio between the IC50 against the specified PRMT and the IC50 against PRMT4 and rounded to the nearest integer.

Ligand efficiency (LE) for PRMT4 calculated from IC50 as a surrogate for KD.

Obtained in the AlphaLISA assay, using human recombinant PRMT1 (0.9 nM, final concentration). Histone H4 (1–21) peptide, biotinylated (100 nM, final concentration), and SAM (2 μM, final concentration) were used as the substrate and cofactor, respectively.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory activities of compounds 12a–12h: the heatmaps depict the IC50 values (nM) for compounds 12a–12h (top panel) and the selectivity index (fold) for PRMT4 over the specified PRMT (bottom).

The selectivity of compound 12h was further assessed against a panel of eight lysine methyltransferases (KMTs), including the SET-domain-containing proteins ASH1L/KMT2H, EZH2/KMT6, MLL1/KMT2A, SET7/9/KMT7, SETD8/KMT5A, SUV39H2/KMT1B, and SUV420H1/KMT5B and the non-SET-domain-containing DOT1L/KMT4.77 To this aim, the inhibition of 12h toward these selected enzymes was assessed at two different concentrations (1 and 10 μM, respectively, >300 and >3000 fold higher than the IC50 value against PRMT4) using SAH,78−80 chaetocin (for ASH1L),81 or ryuvidine (for SETD8)82 as reference compounds. Noteworthy, we found that none of the enzymes was inhibited by 12h even at the higher tested concentration (Figure S2 and Table S1, Supporting Information).

SPR-Based Studies of Binding to PRMT4

First identified as a transcriptional regulator,83 PRMT4, also known as coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1), is a type I enzyme that regulates gene expression by numerous mechanisms. It positively regulates transcription by methylating H3R17 and H3R26,84,85 methylates steroid receptor coactivators including SRC3 and CBP/p300, and can directly act as a transcriptional coactivator of nuclear receptors.86,87 PRMT4 also methylates a variety of other targets, including splicing factors such as CA150,91 to regulate the exon skipping, and RNA-binding proteins (e.g., PABP1, HuR, and HuD),88−90 to modify their ability to bind to the transcription-related proteins. PRMT4 also regulates the looping of enhancers and promoters by methylating MED12, which is a component of the mediator.92

It has been demonstrated that PRMT4 is overexpressed in various cell lines of hematologic cancers and solid tumors, such as leukemia,93,94 breast,95 prostate,96 liver,97 and colorectal cancers.98,99 Moreover, the enzyme is overexpressed in ischemic hearts and hypoxic cardiomyocytes, and it has been suggested that PRMT4 has an essential role in myocardial infarction and cardiomyocyte apoptosis.100 Other emerging functions of PRMT4 include autophagy, metabolism, early development, pre-mRNA splicing and export, and localization to paraspeckles.101 Also, it was recently found that in lymphomas that carry mutation in p300/CBP, PRMT4 loss or inhibition is a vulnerability.102 Therefore, PRMT4 is considered an appealing therapeutic target for anticancer drug development, and in fact a few inhibitors have been developed with different degrees of potency and selectivity.24,41,52,103

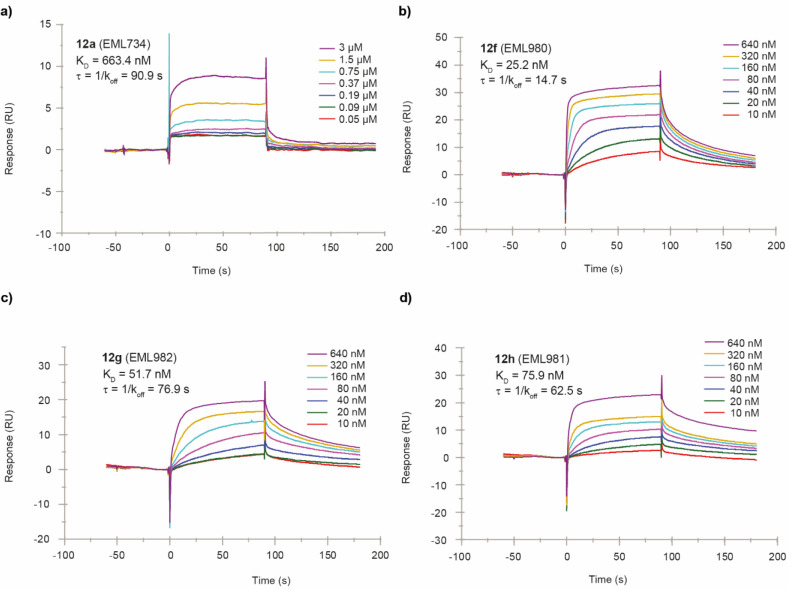

To further characterize the effect of compounds 12a–12h on PRMT4, we resolved to evaluate their direct binding to the target protein using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). To this aim, human PRMT4 (full length) was covalently immobilized on a sensor chip surface using an amine-coupling approach, and the three compounds were injected at different concentrations over the protein surface. To reduce false positives from detergent-sensitive, nonspecific aggregation-based binding, detergents (0.05% Tween-20) were added to the running buffer in all experiments. A specific and strong binding interaction was demonstrated between PRMT4 and each compound, with equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values in the nanomolar range for the most active derivatives 12f–12h (Figure 6 and Table 3). Compound 12f interacts with PRMT4 with higher affinity (KD = 25.2 nM; Table 3) compared to 12g (KD = 51.7 nM) and 12h (KD = 75.9 nM). As shown by the sensorgrams depicted in Figure 6 and Figure S1 (Supporting Information), compounds 12f–12h dissociate from the protein slower than compounds 12a–12e. Nonetheless, the in vitro residence time (τR)104 values are quite similar (Table 3), in particular for compounds 12b, 12c, 12e, 12g, and 12h, and cannot account alone for the higher potency of compounds 12g and 12h. On the contrary, the association rate constants (Kon) certainly contribute to the affinity for the target, being significantly higher for compounds 12f–12h than for compounds 12a–12e (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Sensorgrams obtained from the SPR interaction analysis of compounds 12a and 12f–12h (panels a–d, respectively) binding to immobilized PRMT4. Each compound was injected at different concentrations (from 3 to 0.05 μM for 12a and from 640 to 10 nM for 12f–12h) with an association and a dissociation time of 90 s, with a flow rate of 30 μL/min. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were derived from the ratio between kinetic dissociation (koff) and association (kon) constants.

Table 3. Affinity and Kinetic Parameters Derived from SPR Experiments.

| compound | KD (nM) | kon (1/Ms) | koff (1/s) | τR (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12a | 663.4 | 1.67 × 104 | 0.011 | 90.9 |

| 12b | 2300 | 6.52 × 103 | 0.015 | 66.7 |

| 12c | 359.2 | 3.49 × 104 | 0.013 | 76.9 |

| 12d | 2800 | 2.70 × 105 | 0.760 | 1.31 |

| 12e | 603.4 | 2.58 × 104 | 0.015 | 66.7 |

| 12f | 25.2 | 2.70 × 106 | 0.068 | 14.7 |

| 12g | 51.7 | 0.25 × 106 | 0.013 | 76.9 |

| 12h | 75.9 | 0.21 × 106 | 0.016 | 62.5 |

| SAM | 9.6 | 2.90 × 105 | 0.003 | 333.3 |

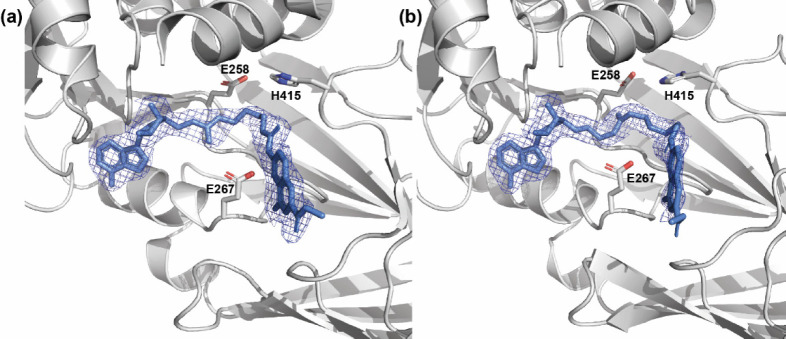

Structural Studies

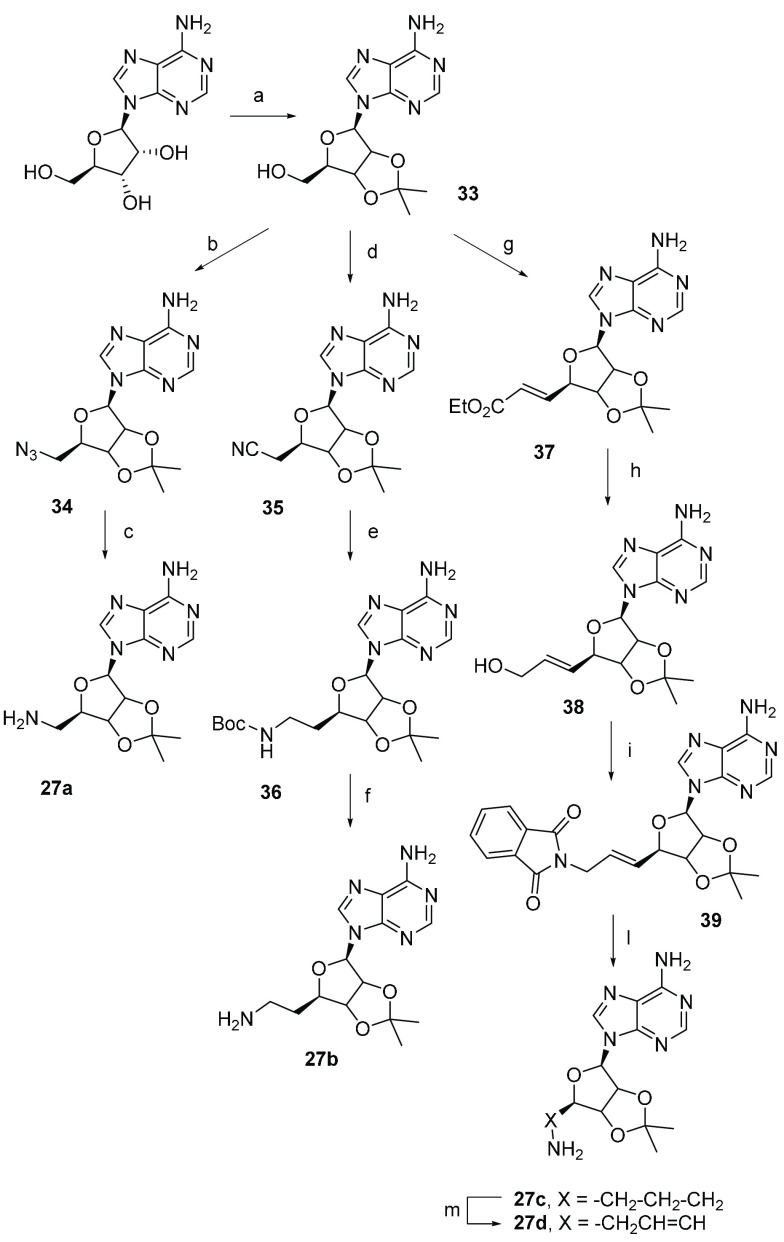

Then we resolved to study and compare the binding modes of compounds 12a–12h with different PRMTs. In particular, we resolved to compare compounds 12a–12c (less potent and selective PRMT4 inhibitors in the series 12, upper part of the heatmaps in Figure 5) and compounds 12f–12h (most potent and selective PRMT4 inhibitors of the series, lower part of the heatmaps in Figure 5) in cocrystallization studies performed using five PRMTs, namely isolated domains of mmPRMT4 (Mus musculus PRMT4, residues 130–487 or 140–497), full length and truncated Rattus norvegicus PRMT1, full length Mus musculus PRMT2, mmPRMT6 (Mus musculus PRMT6, residues 34–378), and full length Mus musculus PRMT7.

Unfortunately, no cocrystals were obtained with PRMT1, PRMT2, or PRMT7. On the contrary, we were able to cocrystallize the compounds in the complex with both PRMT4 and PRMT6. Crystallization, data collection, and structure refinement are fully described in the Experimental Section.

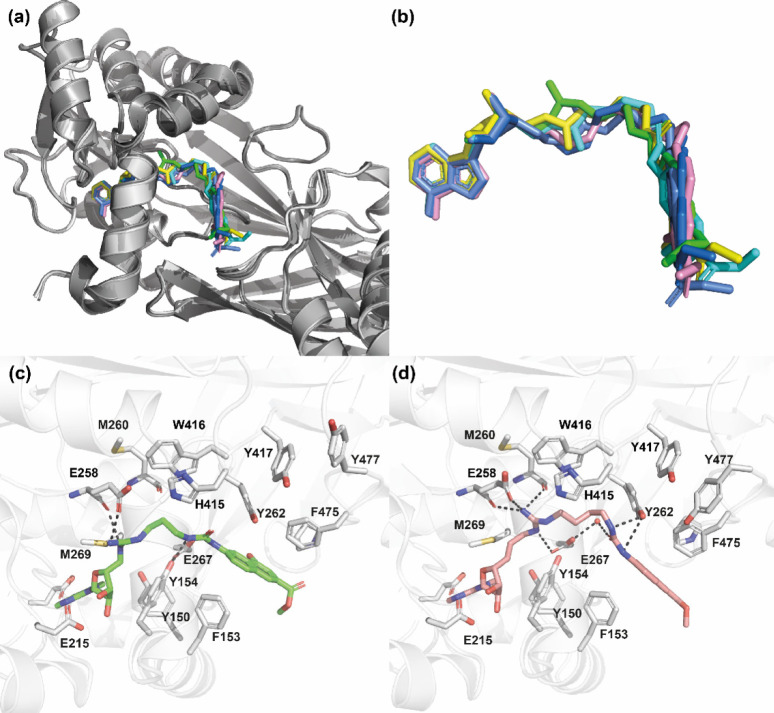

In the case of the complexes with PRMT4, all structures were solved and refined (depending on crystals, resolution ranged from 2.1 to 2.4 Å at ESRF or SOLEIL synchrotron beamlines) in the space group P21212 and contain one copy of the PRMT4 tetramer in the asymmetric unit, as previously described.106 In all cases, each PRMT4 monomer binds one molecule of the ligand (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table 4. The electron density maps obtained in the cocrystallization studies with compounds 12a–12c and 12f–12h reveal the conformation of each compound on all four monomers of the asymmetric unit (Figure 7). All six cocrystallized compounds (12a–12c and 12f–12h) adopt an overall similar conformation in the complex with PRMT4, revealing two common anchoring platforms, the methyl 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate and the adenosine moieties, each one occupying the same binding site on PRMT4 regardless of the different linker lengths (Figure 8a and b). On the contrary, distinctive conformations are observed for the linker in each compound (see below for details).

Table 4. X-ray Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for PRMT4 Complexes with Compounds 12a–12c and 12f–12h.

| ligand | 12a (EML734) | 12b (EML709) | 12c (EML736) | 12f (EML980) | 12g (EML982) | 12h (EML981) |

| PDB ID | 7PV6 | 7PPY | 7PPQ | 7PU8 | 7PUQ | 7PUC |

| data processing | ||||||

| wavelength (Å) | 0.968 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.980 |

| resolution range (Å)a | 48.40–2.40 (2.46–2.40) | 42.53–2.42 (2.49–2.42) | 45.80–2.10 (2.13–2.10) | 48.07–2.19 (2.23–2.19) | 48.01–2.09 (2.12–2.09) | 46.06–2.19 (2.23–2.19) |

| space group | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 |

| unit cell | 75.0 99.5 208.5 90 90 90 | 74.7 98.8 207.0 90 90 90 | 74.8 98.5 206.9 90 90 90 | 75.2 98.8 208.4 90 90 90 | 75.1 98.7 207.8 90 90 90 | 75.3 98.9 208.2 90 90 90 |

| total reflections | 424165 (30752) | 249037 (11755) | 382899 (10013) | 1073363 (40161) | 1237125 (48566) | 1072170 (46596) |

| unique reflections | 61974 (4383) | 58136 (3623) | 89784 (3974) | 80189 (3738) | 92014 (4053) | 80457 (3971) |

| multiplicity | 6.8 (7.0) | 4.3 (3.2) | 4.3 (2.5) | 13.4 (10.7) | 13.4 (12.0) | 13.3 (11.7) |

| completeness (%) | 99.7 (96.8) | 98.3 (80.0) | 99.1 (86.7) | 98.7 (81.5) | 99.5 (90.2) | 99.2 (87.0) |

| mean ⟨I/σI⟩b | 11.3 (1.1) | 8.8 (0.9) | 9.2 (0.9) | 14.4 (1.3) | 17.8 (1.8) | 11.1 (1.1) |

| resolution limit for ⟨I/σI⟩ > 2c | 2.63 | 2.69 | 2.33 | 2.24 | 2.13 | 2.39 |

| Wilson B-factor | 50.5 | 46.1 | 38.4 | 46.2 | 42.5 | 45.3 |

| Rmeas | 0.140 (2.177) | 0.131 (1.441) | 0.101 (1.282) | 0.104 (1.678) | 0.089 (1.387) | 0.164 (2.950) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.547) | 0.998 (0.441) | 0.998 (0.416) | 0.999 (0.543) | 1.000 (0.831) | 0.999 (0.511) |

| refinement | ||||||

| resolution range | 46.17–2.40 (2.49–2.40) | 42.53–2.42 (2.51–2.42) | 45.80–2.10 (2.17–2.10) | 46.09–2.19 (2.27–2.19) | 48.01–2.09 (2.16–2.09) | 46.06–2.19 (2.27–2.19) |

| Rwork | 0.191 (0.318) | 0.205 (0.339) | 0.194 (0.323) | 0.194 (0.322) | 0.181 (0.264) | 0.202 (0.351) |

| Rfree | 0.237 (0.338) | 0.235 (0.359) | 0.228 (0.351) | 0.229 (0.344) | 0.217 (0.304) | 0.230 (0.364) |

| number of non-hydrogen atoms | 11684 | 11303 | 11827 | 11483 | 11659 | 11408 |

| macromolecules | 11282 | 10971 | 11001 | 11000 | 11001 | 10993 |

| ligands | 455 | 436 | 398 | 368 | 410 | 342 |

| solvent | 165 | 104 | 614 | 283 | 442 | 223 |

| validation | ||||||

| RMS(bonds) | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.009 |

| RMS(angles) | 0.75 | 1.32 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 1.21 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.08 | 96.47 | 96.70 | 97.14 | 96.77 | 97.58 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| rotamer outliers (%) | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| average B-factor | 55.96 | 49.51 | 45.06 | 52.70 | 48.59 | 52.36 |

| macromolecules | 55.77 | 49.31 | 44.75 | 52.68 | 48.00 | 51.59 |

| ligands | 69.79 | 60.51 | 57.20 | 58.28 | 63.01 | 85.17 |

| solvent | 49.58 | 46.85 | 46.45 | 49.52 | 48.59 | 61.75 |

| Clashscore | 4.24 | 3.72 | 2.95 | 3.22 | 6.35 | 2.64 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest-resolution shell.

See ref (105) for crystallographic definitions.

The resolution limits for ⟨I/σI⟩ > 2 are reported.

Figure 7.

Electron density (2Fobs – Fcalc) weighted maps. Compound 12b (a) and compound 12h (b) bound to subunit B of mmPRMT4 (PDB IDs: 7PV6 and 7PUC). PRMT4 is represented as a gray cartoon, and compounds are represented as cornflower blue sticks. Maps are represented as a mesh, with the contouring level set to 1σ. For clarity, N-terminal helices (residues 135–155) of PRMT4 are not shown. E258 and E267 belonging to the double-E loop and H415 of the THW loop are also displayed as sticks.

Figure 8.

Structures of mmPRMT4 in complex with compounds 12a–12c and 12f–12h (PDB IDs: 7PV6, 7PPY, 7PPQ, 7PU8, 7PUQ, and 7PUC, respectively). (a) Superimposition (done on protein backbones) of compounds (12a, 12b, 12c, 12f, 12g, and 12h) bound to subunit B of mmPRMT4. Each PRMT4 subunit is represented as a cartoon (shades of gray, lime, cyan, marine, yellow, gray, and pink ribbons), and compounds are represented as sticks (in lime, yellow, cyan, cornflower blue, sea blue, and pink, respectively). (b) Close-up view of bound compound conformations. (c) Binding interactions of compound 12a (lime sticks) with mmPRMT4 monomer B (ribbon). (d) Binding interactions of compound 12h (pink sticks) with mmPRMT4 monomer B (ribbon). Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. For clarity, N-terminal helices (residues 135–165) of PRMT4 are not shown.

As expected, the adenosine moiety occupies the SAM binding site, and as previously described,106 the main interactions are with Y150, E215, E244, and M269 (Figure 8c and d).

On the other hand, the methyl 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety partially occupies the peptide substrate binding site on PRMT4 and mainly interacts with Y262, P473, F475, and Y477 on one side and F153 on the other side (Figure 8c and d). Interestingly, superimposition of the conformation of 12h cocrystallized with PRMT4 with the conformations of the PABP1 peptide transition state mimics recently developed by us44 allowed us to assess that the moiety occupies position −1 to −4 of the peptide substrate binding site, −1 being the position of the amino acid located at the N-terminal side of the arginine to be methylated (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Despite slight modifications observed among monomers inside a given tetramer, the crystal structures of compounds 12a–12c and 12f–12h revealed that the conformations of the protein side chains are identical for all compounds.

Surrounded by such a “frozen” binding site, the linker of each compound adopts a unique and distinctive conformation stabilized by interactions with the protein platform in a region mapped on one side by catalytic residues M260, E258, H415, and W416 and on the other side by F153, Y154, and E267 (Figure 8c and d and Figures S4 and S5, Supporting Information). Depending on the length and the nature of the linker, strong hydrogens bonds are established with such frozen sites, and the number and the strength of the binding interactions of each compound appear to be correlated with the affinity and, consequently, with the IC50 value. In fact, longer compounds 12f–12h showed IC50 values in the low nM ranges compared to the μM range observed for shorter compounds 12a–12c.

In the case of compound 12h, the best inhibitor herein reported, the guanidine group lies between the catalytic glutamate residues (E258 and E267) of the double-E loop in the binding site of the guanidine moiety of the peptide transition state, and the N5 atom establishes two hydrogen bonds with the oxygen atoms of the main chain of E258 and M260 (Figure 8d and Figure S10, Supporting Information).

As revealed by the crystal structures, at least a two-carbon atom long linker between the adenosine moiety and the guanidine group is required to bring the latter within the catalytic clamp formed by E258 and E267, with a three-carbon atom linker (as in compounds 12g and 12h) being even better. If the linker is shorter (as in the case of compounds 12a–12c), the two guanidine-stabilizing hydrogen bonds established with the PRMT4 main chain are lost, and this may account for a weaker affinity compared to derivatives 12f–12h. This observation is in agreement with an improvement in inhibition capability observed for compounds 12f–12h compared to compounds 12a–12c (see Table 2 above). In addition, the trans conformation imposed by the double bond in 12h is less constrained than the one adopted by 12g (also featuring a three-carbon atom linker between the adenosine moiety and the guanidine group) and, therefore, more favorable.

Regarding the linker between the naphthylurea moiety and the guanidine group, a length increase from three carbon atoms (n = 1, 12a) to four or five (n = 2, 12b, and n = 3, 12c, respectively) brings additional van der Waals interaction with W416 and Y262, thus substantiating an increase in affinity and a corresponding decrease in IC50 values.

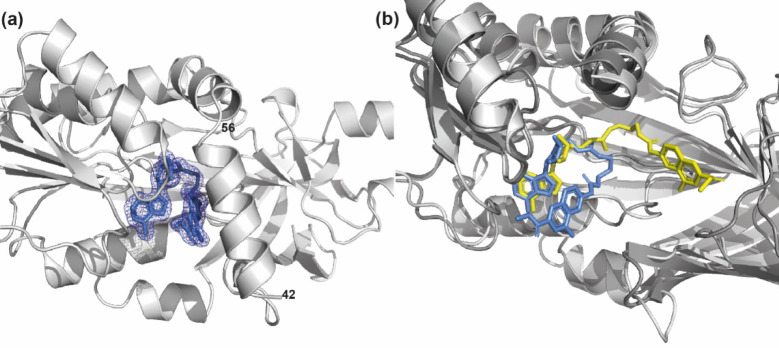

In the case of the complexes with PRMT6, all structures were solved and refined (depending on crystals, resolution ranging from 1.65 to 2.3 Å) in the space group P21 with one copy of the PRMT6 dimer in the asymmetric unit as previously described.107 Structure determinations and refinements revealed that only compounds 12a, 12c, and 12f are visible in the active site of each monomer of the PRMT6 dimer.

For the complexes with the other compounds, a molecule of SAH (constitutively contained in the purified Mus musculus PRMT6) was observed in the active site. Crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table 5. In all the structures of the complexes with PRMT6, the electron density for the compound is always better in one monomer. Compound 12a is the only one for which a complete electron density is visible in one monomer of the PRMT6 structure (Figure 9), whereas for 12c and 12f the electron density becomes fragmented after the guanidine group and the density for the methyl-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety is weak. Moreover, for compound 12f, the active site of one monomer is occupied by both the compound and SAH.

Table 5. X-ray Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for PRMT6 Complexes with Compounds 12a, 12b, and 12f.

| ligand | 12a (EML734) | 12c (EML736) | 12f (EML980) |

| PDB ID | 7NUD | 7NUE | 7P2R |

| data processing | |||

| wavelength (Å) | 1.54178 | 1.54178 | 1.54178 |

| resolution range (Å)a | 45.08–1.65 (1.68–1.65) | 45.26–2.00 (2.05–2.00) | 45.34–2.30 (2.39–2.30) |

| space group | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| unit cell (Å, deg) | 41.8 118.1 72.0 90 104.3 90 | 41.8 118.5 71.9 90 103.1 90 | 41.8 118.7 72.1 90 102.8 90 |

| total reflections | 1494775 (29889) | 174449 (10045) | 119380 (8711) |

| unique reflections | 80845 (4071) | 45652 (3074) | 30045 (2880) |

| multiplicity | 18.5 (7.3) | 3.8 (3.3) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| completeness (%) | 99.6 (99.8) | 98.7 (91.4) | 98.7 (90.6) |

| ⟨I/σI⟩b | 14.9 (1.1) | 14.4 (2.0) | 7.2 (2.0) |

| resolution limit for ⟨I/σI⟩ > 2c | 1.72 | 2.00 | 2.30 |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 21.3 | 27.9 | 35.2 |

| Rmeas | 0.123 (2.215) | 0.112 (0.737) | 0.130 (0.597) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.479) | 0.996 (0.679) | 0.989 (0.780) |

| refinement | |||

| resolution range (Å) | 37.46–1.65 (1.71–1.65) | 38.53–2.0 (2–2.0) | 45.34–2.3 (2–2.3) |

| % Rwork | 0.1961 (0.2903) | 0.1957 (0.2659) | 0.1990 (0.2649) |

| % Rfree | 0.2135 (0.3114) | 0.2434 (0.3227) | 0.2685 (0.3706) |

| number of non H atoms | 5375 | 5341 | 5396 |

| protein | 5148 | 5126 | 5266 |

| ligands | 152 | 92 | 92 |

| water | 139 | 123 | 38 |

| validation | |||

| RMS(bonds) | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| RMS(angles) | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.03 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 98.61 | 97.83 | 98.18 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| rotamer outliers (%) | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.90 |

| average B-factor (Å2) | 30.87 | 33.39 | 40.92 |

| protein | 30.69 | 33.02 | 40.59 |

| ligands | 43.30 | 58.06 | 62.86 |

| water | 29.82 | 30.33 | 32.21 |

| Clashscore | 3.49 | 4.08 | 3.32 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest-resolution shell.

See ref (105) for crystallographic definitions.

The resolution limits for ⟨I/σI⟩ > 2 are reported.

Figure 9.

(a) Electron density (2Fobs – Fcalc) weighted maps of compound 12a (represented as cornflower blue sticks) bound to subunit B of mmPRMT6 (represented as a gray cartoon; PDB ID: 7NUD). Maps are represented as a mesh, with the contouring level set to 1σ. For clarity, N-terminal helices (residues 42–56) of mmPRMT6 are not shown. (b) Superimposition (done on protein backbones) of the conformations of compound 12a (yellow or cornflower blue sticks, respectively) when bound to subunit B of mmPRMT4 (represented as a dark gray cartoon) and when bound to mmPRMT6 (represented as a light gray cartoon). For clarity, N-terminal helices of PRMT4 and PRMT6 are not shown.

The crystal structure revealed an unusual distorted U-shaped conformation adopted by compound 12a (and probably also 12c and 12f) in the binding to PRMT6, with a folding at the level of the guanidine group (Figure 9 and Figure S11, Supporting Information). Whereas the adenosine moiety lies into its canonic binding pocket, the guanidine group of the compounds is unable to reach the PRMT6 double-E loop clamp because the linker with the sugar is too short, even for the longer compound 12f. Instead of binding in the arginine substrate pocket as observed with PRMT4 (Figures S2 and S8–S10, Supporting Information), the methyl-4 hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety is sandwiched between the adenosine and the side chains of Y50 and Y51 residues of the α helix motif I (Figure S12, Supporting Information). Hence, the binding of compounds 12a, 12c, and 12f affects the proper folding of the PRMT6 alpha-X helix containing the motif I (Y50-Y51-X-X-Y54).

If compared to the structures obtained in the presence of SAH, the binding site of the complex of PRMT6 with compound 12a is larger due to a displacement of the α helix and the flipping of the side chains of Y50 and Y51 residues to give room for the compound naphthoate moiety. As a consequence, the E267 residue of the double-E loop is not coordinated anymore by residues Y50 and Y54 of motif 1 and adopts a different conformation (Figure S11, Supporting Information).

Assessment of Functional Potency and Cell Toxicity in Various Cell Lines

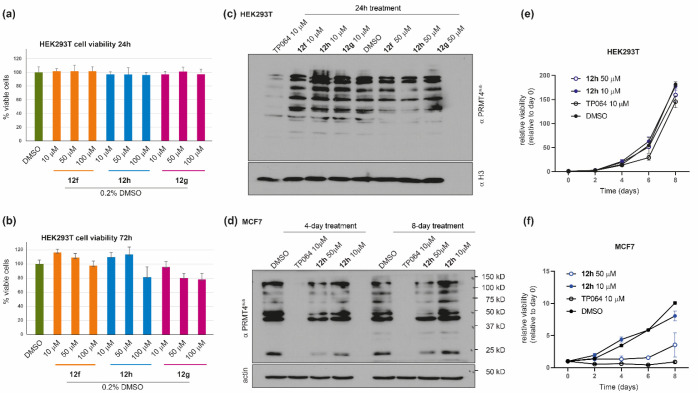

As mentioned above, this study was designed as a proof of concept of our approach to probe the structural differences among the various PRMTs and to develop potent and selective inhibitors. Therefore, we were not surprised to find that, at this stage, compounds 12f–12h showed poor apparent permeability in a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA), using the reference drugs propranolol (highly permeable) and the furosemide (poorly permeable) as positive and negative controls, respectively (see the Supporting Information). Nonetheless, we resolve to investigate if, regardless of the low cell permeability, the compounds were able to affect the activity of PRMT4 in a cellular context. First, we assessed cell toxicity in human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells. To this aim, we incubated the cell line with different concentrations (10, 50, and 100 μM) of each compound and assessed cell viability after 24 and 72 h using the MTT assay. We observed that none among the tested compound was able to reduce the number of metabolically active cells in comparison with the vehicle, at all the tested concentrations (up to 100 μM, Figure 10a). Even after 72 h of treatment cell viability remained above 80% (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Cellular effects of compounds 12f–12h. (a, b) The viability of HEK293T cells was assessed by measuring the mitochondrial-dependent reduction of MTT to formazan, with respect to DMSO, after treatment with compounds 12f–12h at three different concentrations (10, 50, and 100 μM) for (a) 24 h and (b) 72 h. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of four independent experiments. (c, d) Western blot analyses were performed (a) on lysates from HEK293T cells after treatment with compounds 12f–12h at 10 and 50 μM for 24 h and (d) on lysates from MCF7 cells after treatment with compound 12h at 10 and 50 μM for 4 and 8 days. Methylation was detected by immunoblotting with a pan-PRMT4 substrate antibody (PRMT4sub; see the main text).102 Total histone H3 (c) or actin (d) was used to check for equal loading. The cell-permeable PRMT4 inhibitor TP064 (10 μM) was used as a reference compound. (e, f) Relative proliferation of (e) HEK293T and (f) MCF7 cells with different concentration of 12h for different time points. The medium was changed at day 4. All the data points represent the relative viability normalized to day 0. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates performed at each time point.

We next investigated the functional potency of compounds 12f–12h in reducing the cellular level of arginine methylation catalyzed by PRMT4. To this aim, HEK293T cells were incubated for 24 h with the three compounds (at 10 and 50 μM) or with compound TP-064 (10 μM)24 and used as a positive control, and total cell lysates were then immunoblotted with a pan-PRMT4 substrate antibody (PRMT4sub), originally raised against the R388 site of Nuclear Factor 1 B-type (NFIB-Me) but also capable of recognizing many PRMT4 substrates.102,108 As shown in Figure 10c, the results confirmed the proof of concept concerning the design of these derivatives. In fact, although with a lower effect compared to the cytopermeable TP-064, the compounds, in particular 12h, are able to reduce the activity of PRMT4 in a concentration-dependent way. Noteworthy, TP-064 concentrations higher than 10 μM led to cell death. Based on these findings, we resolved to investigate the effects of compound 12h also on the MCF7 breast cancer cell line, the proliferation of which was previously found to be dependent on PRMT4.109,110 MCF7 cells were incubated with 12h (at 10 and 50 μM) or with the control TP-064 (10 μM) for 4 and 8 days used as positive control, and total cell lysates were then immunoblotted with the pan-PRMT4 substrate antibody PRMT4sub. As shown in Figure 10d, the arginine methylation levels in MCF7 cells are profoundly affected by TP064 but also by the significantly less permeable 12h, in a concentration- and time-dependent way. More importantly, both 10 μM TP064 and 50 μM 12h markedly decreased the proliferation of MCF7 cells, whereas no effect was observed in HEK293T cells (Figure 10e and f).

Conclusions

The pivotal role played by PRMT-mediated arginine methylation in the regulation of many cellular processes and the implications in the genesis of various diseases have attracted growing interest toward PRMTs as potential therapeutic targets. Yet, even if a few clinical-grade small-molecule inhibitors have been identified for these proteins,11 there is still much to be understood about their functions and the biological pathways in which they are involved, as well as on the structural requirements that could drive the development of selective modulators of PRMT activity.11

In this work, starting from a series of type I PRMT inhibitors previously identified by us and with molecular modeling studies of their binding mode,46,47 we deconstructed such ligands into a 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic fragment and then applied a step-by-step growing approach, in which the fragment was bridged by an amide or urea group with an arginine mimetic or methionine moiety. As a primary screening, we gauged the effect of the synthesized compounds (derivatives 5–11) on the catalytic activity of human recombinant PRMT1, chosen as representative of class I PRMTs, using a purpose-developed AlphaLISA assay. The compounds showing an inhibition greater than 85% were selected, and the corresponding IC50 values were determined. The structure–activity relationships identified a scaffold (namely compound 7d) featuring both naphthylurea and methylguanidine groups as the best candidate for the further growing step. Then, another series of compounds (12a–12h) were designed and synthesized, introducing also an adenosine moiety and exploring the distance between the three groups.

A radioisotope-based filter-binding assay was used as a secondary screening to profile the activity of the compounds against type I PRMT1, PRMT3, PRMT4, PRMT6, and PRMT8, type II PRMT5, and type III PRMT7. The overall length of the compounds and, even more, the length of the two linkers resulted to be crucial for the inhibitory activity especially against PRMT4 and, at a minor extent, against PRMT1. In fact, derivative 12h featuring a four-carbon atom linker between the 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate and the guanidine group and a three-carbon atom linker between the latter and the adenosine resulted to be the most potent inhibitor against PRMT4 (IC50 = 3 nM), with a 261- to 1266-fold selectivity over the other PRMTs. Noteworthy, 12h was found to be selective also and further assessed against a panel of eight KMTs, including the SET-domain-containing proteins ASH1L/KMT2H, EZH2/KMT6, MLL1/KMT2A, SET7/9/KMT7, SETD8/KMT5A, SUV39H2/KMT1B, and SUV420H1/KMT5B and the non-SET-domain-containing DOT1L/KMT4, showing no inhibiting effect against these enzymes even at the higher tested concentration (>3000 fold higher than the IC50 value against PRMT4). SPR studies confirmed a specific and strong binding interaction between PRMT4 and 12h with a KD value in the nanomolar range (KD = 75.9 nM; τR = 62.5 s), and crystallographic studies showed that the three-carbon atom long linker between the adenosine moiety and the guanidine group brings the latter within the catalytic clamp formed by E258 and E267 of the double-E loop, allowing the establishing of stabilizing hydrogen bonds between the guanidine N5 atom and the main chain oxygen atoms of E258 and M260. The trans conformation imposed by the double bond in 12h impedes the formation of more constrained rotamers. On the other hand, the methyl 4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety partially occupies the peptide substrate binding site on PRMT4 and mainly interacts with Y262, P473, F475, and Y477 on one side and F153 on the other side.

Whereas a similar trend was observed also against PRMT1 and PRMT5, the effect of the linker length on the inhibiting activity was less significant (if any) in the case of PRMT3, PRMT8, and, particularly, PRMT6. In the case of the latter, cocrystallization studies revealed that the compounds adopt an odd distorted U-shaped conformation, where the guanidine group is unable to reach the PRMT6 double-E loop clamp and the methyl-4 hydroxy-2-naphthoate moiety does not bind to the arginine substrate pocket, but it is sandwiched between the adenosine and the side chains of Y50 and Y51 residues of α helix motif I. Interestingly, in the case of PRMT7 the shorter compound 12a shows a certain selective inhibition (IC50 = 0.3 μM; selectivity from 26-fold to 231-fold) compared to other tested PRMTs, in agreement with the restrictive and narrow active site for PRMT7.111

Surprisingly, regardless of the low cell permeability, 12h is able to affect the activity of PRMT4 in a cellular context, showing an evident reduction of arginine methylation levels in MCF7 cells and a marked reduction of proliferation.

In conclusion, this study confirmed the feasibility of our deconstruction–reconstruction approach to achieve potency and selectivity against a specific PRMT isoform starting from nonselective PRMT inhibitors. Although nonoptimized for cell permeability, the identified PRMT4 inhibitor 12h (EML981) is able to reduce the activity of PRMT4 in a concentration-dependent way and can be used for further development of cell-active PRMT4 inhibitors. Also, the approach is versatile and can be applied to identify selective inhibitors of other PRMTs.

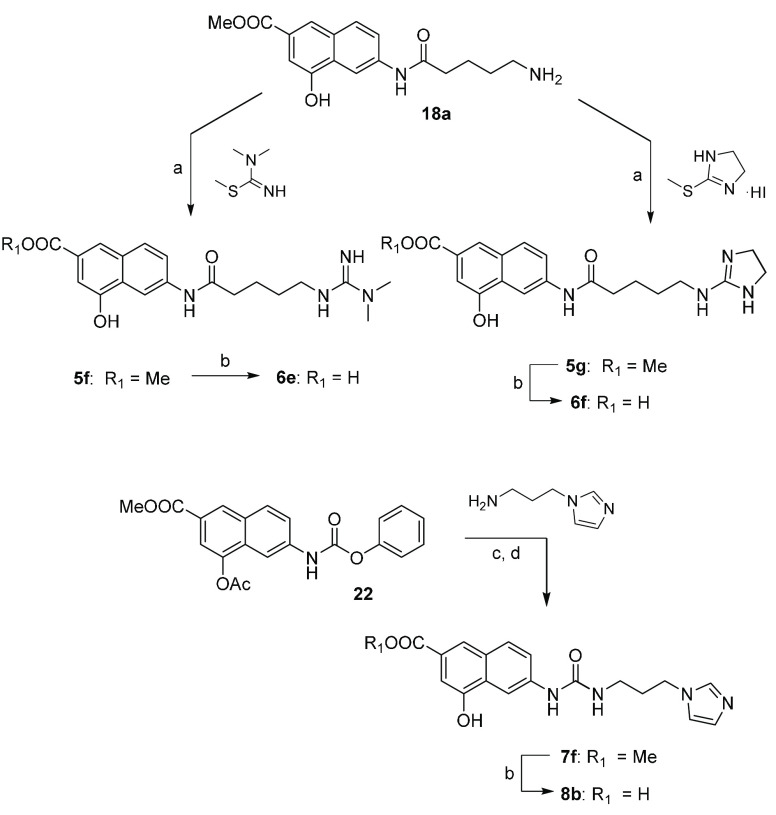

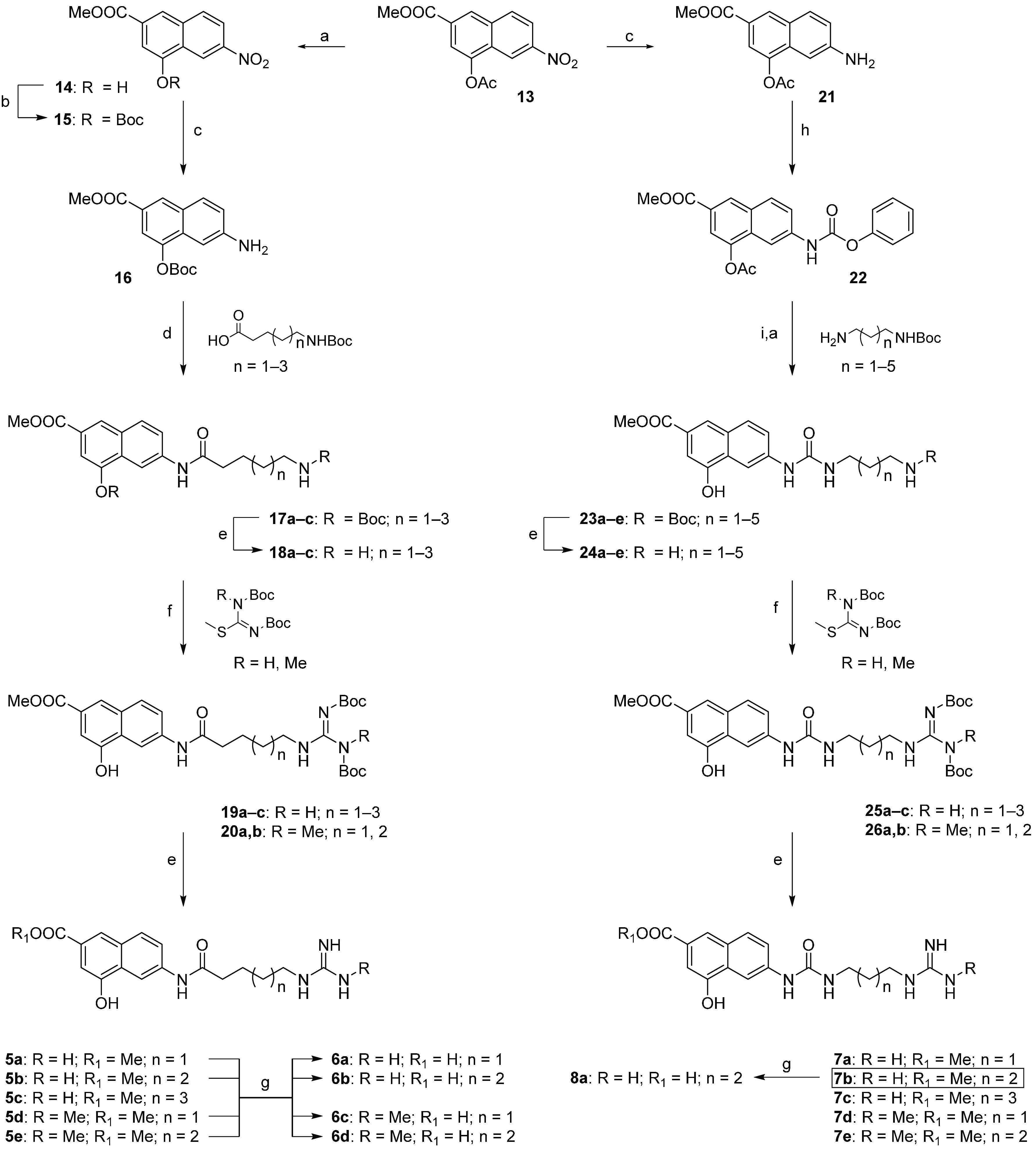

Chemistry

The synthetic protocol for the preparation of compounds 5–8 is depicted in Schemes 1 and 2. The 4-acetoxy-6-nitro-2-naphthoate 13, prepared as previously reported by us,47 was straightforwardly transformed in the 4-hydroxy-6-nitro-2-naphthoate 14,112 through treatment with piperidine in dichloromethane (DCM; Scheme 1). Protection of the hydroxyl group with di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Boc2O) in the presence of triethylamine (TEA) and N,N-dimethyl-4-aminopyridine (DMAP) yielded the intermediate 15 which was then reduced with zinc dust in acetic acid to give the corresponding arylamine 16. The reaction of the latter with the proper Boc-protected aminoalkanoic acid, in the presence of N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and DMAP, furnished amides 17a–17c. After deprotection with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in DCM, the resulting amines 18a–18c were reacted with Boc-protected S-methylisothiourea or N,S-dimethylisothiourea to yield the protected guanidines 19a–19c and 20a and 20b. Removal of the tert-butoxycarbonyl group under acidic conditions gave ester derivatives 5a–5e, from which the corresponding carboxylic acids 6a–6d were obtained by hydrolysis with lithium hydroxide aqueous solution. A similar synthetic pathway was followed to prepare ureido derivatives 7a–7e and 8a (Scheme 1). Briefly, naphthylamine 21, prepared from the same key building block 13 as previously reported by us,47 was reacted with phenyl chloroformate to yield phenyl carbamate 22. The reaction of the latter with the proper mono-Boc-protected alkyldiamine, followed by treatment with piperidine in DCM, furnished derivatives 23a–23e. After trifluoroacetic acid deprotection, the corresponding amines 24a–24e were reacted with Boc-protected S-methylisothiourea or N,S-dimethylisothiourea to yield compounds 25a–25c, 26a, and 26b. Finally, deprotection gave esters 7a–7e. The carboxylic acid derivative 8a was obtained by hydrolysis of ester 7b. As depicted in Scheme 2, the amine 18a was also reacted with 1,1,2-trimethylisothiourea to give the substituted guanidine derivative 5f or with 2-methylthio-2-imidazoline hydroiodide to yield the imidazoline derivative 5g. The carboxylic acids 6e and 6f were obtained from 5f and 5g, respectively, by hydrolysis with lithium hydroxide aqueous solution. Reaction of phenyl carbamate 22 with 3-imidazolylpropan-1-amine followed by treatment with piperidine in DCM furnished ester derivative 7f. Finally, the carboxylic acid 8b was obtained by basic hydrolysis.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Derivatives 5a–5e, 6a–6d, 7a–7e, and 8a.

Reagents and conditions: (a) piperidine, DCM, room temperature (r.t.), 30 min. (93–99%); (b) Boc2O, TEA, DMAP, DCM, r.t., 12 h (70%); (c) Zn, AcOH, r.t., 1 h (98–99%; (d) DCC, DMAP, DCM, r.t., 8–12 h (80–88%); (e) DCM/TFA, 9:1, r.t., 1 h (60–99%); (f) TEA, DMAP, DMF, r.t., 24 h (30–85%); (g) LiOH, MeOH/H2O, r.t., 48 h (80–92%); (h) phenyl chloroformate, TEA, EtOAc, r.t., 12 h (70%); (i) TEA, DMF, r.t., 24 h (80–87%).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Derivatives 5f, 5g, 6e, 6f, 7f, and 8b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) TEA, DMAP, DMF, r.t., 24 h (57–67%); (b) LiOH, MeOH/H2O, r.t., 48 h (62–89%); (c) TEA, DMAP, DMF, r.t., 24 h; (d) piperidine, DCM, room temperature (r.t.), 30 min (71%, over two steps).

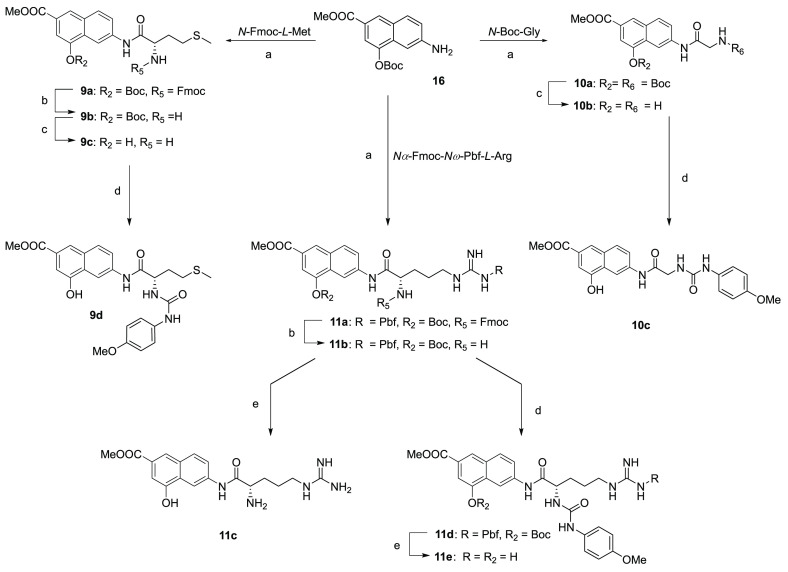

Derivatives 9–11 were in turn prepared (Scheme 3) starting from the O-Boc-aminohydroxynaphthoate 16 that was reacted with the orthogonally protected N-Fmoc-l-methionine, N-Boc-glycine, or Nα-Fmoc-Nω-Pbf-l-arginine in the presence of DCC and DMAP to give the corresponding amides 9a, 10a, or 11a. After deprotection with piperidine and/or TFA in DCM, the corresponding compounds 9c, 10b, and 11b were reacted with 4-methoxyphenyl isocyanate in the presence of TEA to obtain ureas 9d, 10c, and 11d. Derivatives 11c and 11e were obtained from 11b and 11d, respectively, after the removal of Pbf protection.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Derivatives 9–11.

Reagents and conditions: (a) proper N-protected amino acid, DCC, DMAP, DCM, r.t., 8–12 h (79–81%); (b) piperidine, DCM, 30 min (72–99%); (c) DCM/TFA, 9:1, r.t., 1 h (68–74%); (d) 4-methoxyphenyl isocyanate, TEA, THF, r.t., 4 h (79–82%); (e) DCM/TFA, 1:9, r.t., 24 h (68–77%).

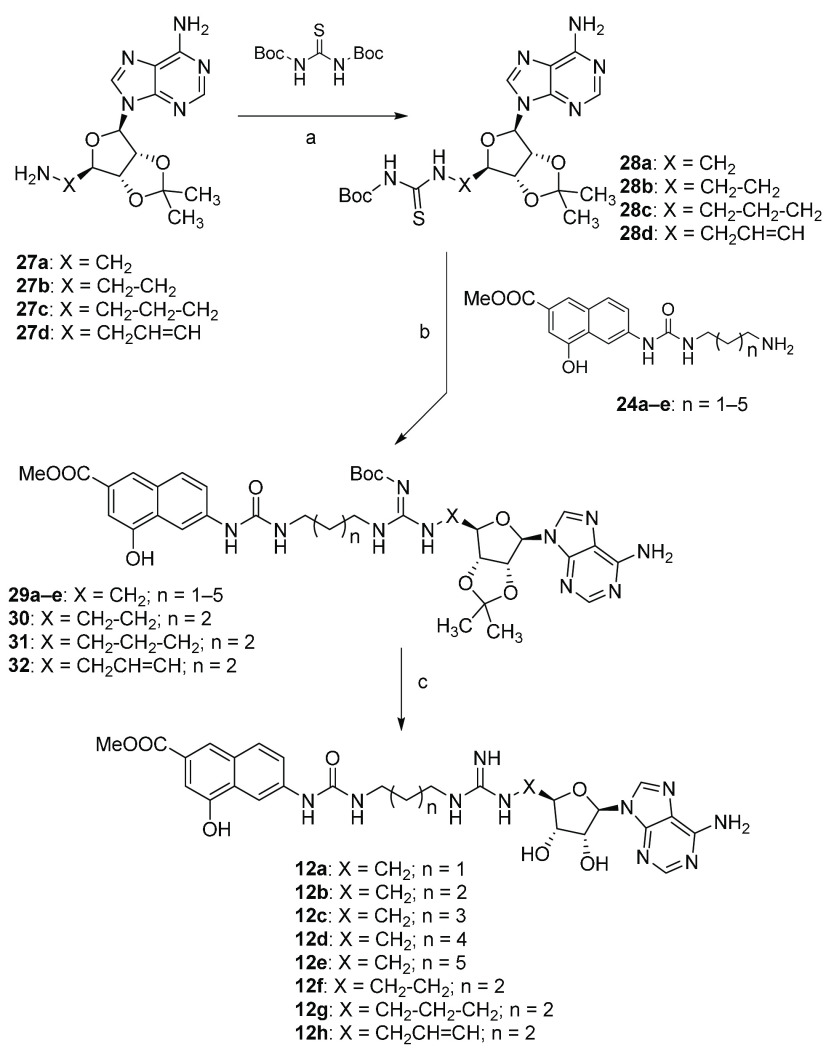

Compounds 12a–12h were prepared as outlined in Scheme 4. Adenosine derivatives 27a–27d,44,113−115 obtained according to a slight modification of previously reported procedures116,117 (Scheme 5), were reacted with N,N′-di-Boc-thiourea in the presence of trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) and sodium hydride118 to give thioureas 28a–28d. A coupling reaction with amino derivatives 24a–24e in the presence of EDC hydrochloride as an activating agent yielded derivatives 29–32 which were deprotected with TFA to obtain the target compounds 12a–12h.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Derivatives 12a–12h.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaH 60% mineral oil, TFAA, dry THF, r.t., 16 h (33–53%); (b) EDC hydrochloride, TEA, DCM, r.t., 18 h (72–81%); (c) DCM/TFA, 1:1, r.t., 2 h (74–80%).

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Derivatives 27a–27d.

Reagents and conditions: (a) acetone, HClO4 70%, r.t., 5 h (81%); (b) NaN3, DPPA, DBU, 15-crown-5, dioxane, 2 h (86%); (c) H2, Pd/C 10%, MeOH, r.t., 5 h (99%); (d) α-hydroxyisobutyronitrile, DEAD, PPh3, dry THF, 0–20 °C, 24 h, (89%); (e) Boc2O, NaBH4, NiCl2·6H2O, dry MeOH, 0 °C, 2 h (80%); (f) DCM/TFA 95:5, t.a, 8 h, (65%); (g) o-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX), CH3CH2O2CCH=P(C6H5)3, DMSO, 20 °C, 72 h, (70%); (h) DIBAL-H, DCM, −78 °C, 2 h, (98%); (i) phthalimide, DEAD, PPH3, dry THF, 20 °C, 16 h, (70%); (l) NH2NH2·H2O, MeOH, 0–25 °C, 16 h, (90%); (m) H2, Pd/C 10%, AcOEt, 20 °C, 18 h (99%).

Experimental Section

Chemistry

General Directions

All chemicals, purchased from Merck KGaA and Fluorochem Ltd., were of the highest purity. All solvents were reagent grade and, when necessary, were purified and dried by standard methods. All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were conducted under a positive atmosphere of nitrogen in oven-dried glassware. Standard syringe techniques were used for anhydrous addition of liquids. Reactions were routinely monitored by TLC performed on aluminum-backed silica gel plates (Merck KGaA, Alufolien Kieselgel 60 F254) with spots visualized by UV light (λ = 254, 365 nm) or using a KMnO4 alkaline solution. Solvents were removed using a rotary evaporator operating at a reduced pressure of ∼10 Torr. Organic solutions were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Chromatographic purification was done on an automated flash-chromatography system (Isolera Dalton 2000, Biotage) using cartridges packed with KP-SIL, 60 Å (40–63 μm particle size). All microwave-assisted reaction were conducted in a CEM Discover SP microwave synthesizer equipped with a vertically focused IR temperature sensor.

Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Shimadzu SPD 20A UV/vis detector (λ = 220 and 254 nm) using a C-18 column Phenomenex Synergi Fusion-RP 80A (75 × 4.60 mm; 4 μm) at 25 °C using a mobile phase A (water + 0.1% TFA) and B (ACN + 0.1% TFA) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Preparative HPLC was performed using a Shimadzu Prominence LC-20AP with the UV detector set to 220 and 254 nm. Samples were injected onto a Phenomenex Synergi Fusion-RP 80A (150 × 21 mm; 4 mm) C-18 column at room temperature. Mobile phases of A (water + 0.1% TFA) and B (ACN + 0.1% TFA) were used with a flow rate of 20 mL/min.

1H spectra were recorded at 400 MHz on a Bruker Ascend 400 spectrometer while 13C NMR spectra were obtained by distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer quaternary (DEPTQ) spectroscopy on the same spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm) relative to the internal reference tetramethylsilane (TMS). Low-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Finnigan LCQ DECA TermoQuest mass spectrometer in electrospray positive and negative ionization modes (ESI-MS). High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a ThermoFisher Scientific Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer in electrospray positive ionization modes (ESI-MS). All tested compounds possessed a purity of at least 95% established by HPLC unless otherwise noted.

Methyl 6-(5-Guanidinopentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (5a)

Compound 19a (280 mg, 0.501 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of a solution of DCM/TFA (9:1), and the mixture was stirred for 48 h. The solvent was evaporated, and the resulting solid was washed with CHCl3 to give the TFA salt of compound 5a as a brown solid (201 mg, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.45 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.24 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.01–7.95 (m, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.21–6.75 (m, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.18–3.12 (m, 2H), 2.42 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.68–1.53 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.96, 167.02, 156.91, 153.20, 138.43, 130.18, 130.14, 127.79, 126.06, 121.49, 121.09, 110.05, 106.93, 40.90, 40.42, 36.21, 28.35, 22.48. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H22N4O4 + H+: 359.1714. Found: 359.1705.

Methyl 6-(6-Guanidinohexanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (5b)

The TFA salt of compound 5b was obtained as a pale brown solid (254 mg, 81%) starting from compound 19b (370 mg, 0.646 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.43 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.20 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.22–6.83 (m, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.12–3.10 (m, 2H), 2.39 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.67–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.37–1.33 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.94, 167.05, 157.18, 153.45, 138.77, 130.27, 130.19, 128.00, 126.10, 121.55, 121.13, 110.05, 107.10, 52.51, 41.13, 36.82, 28.84, 26.23, 25.13. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H24N4O4 + H+: 373.1870. Found: 373.1863.

Methyl 6-(7-Guanidinoheptanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (5c)

The TFA salt of compound 5c was obtained as a pale brown solid (76 mg, 90%) starting from 19c (100 mg, 0.170 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.45 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.20 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H) 7.71 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.23–6.77 (m, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.12–3.07 (m, 2H), 2.38 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.65–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.51–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.35–1.33 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.04, 167.05, 157.22, 153.45, 138.79, 130.26, 130.19, 128.01, 126.09, 121.55, 121.15, 110.05, 107.09, 52.50, 41.21, 36.88, 28.81, 28.75, 26.39, 25.44. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C20H26N4O4 + H+: 387.2027. Found: 387.2017.

Methyl 4-Hydroxy-6-(5-(3-methylguanidino)pentanamido)-2-naphthoate (5d)

The TFA salt of compound 5d was obtained as a brown solid (204 mg, 86%) starting from 20a (280 mg, 0.489 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.47 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.28 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H) 7.96 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.45 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.36–7.34 (m, 3H, 2H exchangeable with D2O), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.18–3.14 (m, 2H), 2.75–2.74 (m, 3H), 2.44–2.40 (m, 2H), 1.68–1.53 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.85, 167.09, 156.80, 153.47, 138.73, 130.29, 130.20, 128.01, 126.12, 121.53, 121.15, 110.10, 107.11, 52.51, 41.13, 36.42, 28.64, 28.39, 22.67. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H24N4O4 + H+: 373.1870. Found: 373.1873.

Methyl 4-Hydroxy-6-(6-(3-methylguanidino)hexanamido)-2-naphthoate (5e)

The TFA salt of compound 5e was obtained as a pale brown solid (279 mg, 80%) starting from 20b (410 g, 0.699 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.48 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.24 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.40 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.34–7.32 (m, 3H, 2H exchangeable with D2O), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.13–3.09 (m, 2H), 2.73 (s, 3H), 2.39 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.66–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.50 (m, 2H), 1.36–1.33 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.96, 167.05, 156.73, 153.45, 138.77, 130.25, 130.20, 128.00, 126.10, 121.55, 121.12, 110.05, 107.10, 52.51, 41.23, 36.82, 28.86, 28.40, 26.22, 25.14. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C20H26N4O4 + H+: 387.2027. Found: 387.2020.

Methyl 6-(5-(3,3-Dimethylguanidino)pentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (5f)

To a stirred solution of 18a (200 mg, 0.464 mmol) and DMAP (6 mg, 0.046 mmol) in dry DMF (2.5 mL), TEA (65 μL, 0.464 mmol) and 1,3-bis(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea (228 mg, 0.929 mmol) were added. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The solution was diluted with AcOEt (30 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (gradient Hex/AcOEt 80:20 to 20:80) to give 5f as a white solid (268 mg, 67%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.46 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.24 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.55 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.37 (t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.36–7.34 (m, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.23–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.96 (s, 6H), 2.42 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.68–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.57 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.87, 167.05, 156.20, 153.46, 138.72, 130.30, 130.22, 127.99, 126.14, 121.55, 121.13, 110.09, 107.11, 52.51, 42.13, 38.60, 36.47, 28.67, 22.63. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C20H26N4O4 + H+: 387.2027. Found: 387.2019.

Methyl 6-(5-((4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)amino)pentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (5g)

Compound 5g was obtained as a white product (136 mg, 61%) by the reaction of compound 18a (250 mg, 0.58 mmol) with 2-methylthio-2-imidazoline hydroiodide (283 mg, 1.16 mmol) following the procedure described for 5f. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.45 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.23 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 4.27–3.97 (m, 4H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.19–3.14 (m, 2H), 2.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.66–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.51 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.79, 167.04, 159.87, 153.45, 138.70, 130.30, 130.22, 127.99, 126.14, 121.55, 121.13, 110.09, 107.11, 52.51, 42.92, 42.49, 36.39, 28.85, 22.62. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C20H24N4O4 + H+: 385.1870. Found: 385.1863.

6-(5-Guanidinopentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (6a)

To a stirred solution of 5a (100 mg, 0.211 mmol) in 4 mL of MeOH, an aqueous solution (1 mL) of LiOH (15 mg, 0.633 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48–72 h (TLC analysis). The resulting mixture was acidified with 1 N HCl and then concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) to afford 6a as the TFA salt (89 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.81 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.38 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.23 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.99–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.22–6.75 (m, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.19–3.10 (m, 2H), 2.43 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.69–1.53 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.26, 167.64, 156.71, 152.78, 137.95, 129.86, 129.61, 127.30, 121.07, 120.48, 109.65, 107.07, 40.54, 35.91, 28.13, 22.17. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C17H20N4O4 + H+: 345.1557. Found: 345.1549.

6-(6-Guanidinohexanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (6b)

The TFA salt of compound 6b was obtained as a white solid (149 mg, 77%) starting from 5b (200 mg, 0.411 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.79 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.38 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.21 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.97–7.92 (m, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (br t 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.17–6.77 (m, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.12–3.09 (m, 2H), 2.39 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H),1.67–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.50 (m, 2H), 1.37–1.34 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.08, 168.13, 157.06, 153.24, 138.35, 130.33, 130.13, 127.72, 127.26, 121.61, 120.95, 110.14, 107.51, 41.13, 36.74, 28.76, 26.18, 25.13. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H22N4O4 + H+: 359.1714. Found: 359.1707.

4-Hydroxy-6-(5-(3-methylguanidino)pentanamido)-2-naphthoic Acid (6c)

The TFA salt of compound 6c was obtained as a pale brown solid (84 mg, 88%) starting from 5d (100 mg, 0.204 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.79 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.37 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.22 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.99–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.30 (m, 5H, 4H exchangeable with D2O), 3.19–3.14 (m, 2H), 2.76 (s, 3H), 2.45–2.40 (m 2H), 1.70–1.53 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.87, 168.10, 138.28, 130.35, 130.16, 127.75, 127.27, 121.63, 121.05, 110.17, 107.46, 41.02, 36.34, 28.55, 28.23, 22.63. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H22N4O4 + H+: 359.1714. Found: 359.1709.

4-Hydroxy-6-(6-(3-methylguanidino)hexanamido)-2-naphthoic Acid (6d)

The TFA salt of compound 6d was obtained as a white solid (155 mg, 80%) starting from 5e (200 mg, 0.399 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.75 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.37 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.26 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.55 (s, 1H), 7.97–7.92 (m, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (br t, 1H,, exchangeable with D2O) 7.50–7.34 (m, 4H, 3H exchangeable with D2O), 3.15–3.10 (m, 2H), 2.74 (s, 3H), 2.40 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.68–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.51 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.36 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.97, 168.15, 156.89, 153.29, 138.55, 130.31, 130.03, 127.82, 127.29, 121.54, 121.01, 110.11, 107.56, 41.20, 36.82, 28.84, 28.38, 26.21, 25.17. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H24N4O4 + H+: 373.1870. Found: 373.1862.

6-(5-(3,3-Dimethylguanidino)pentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (6e)

Compound 6e was obtained as a pale brown solid (74 mg, 62%) starting from 5f (95 mg, 0.245 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.37 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.21 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.53 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.37 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.33 (s, 1H), 3.23–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.42 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.70–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.53 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.81, 168.13, 156.20, 153.27, 138.45, 130.35, 130.10, 127.80, 127.35, 121.57, 120.97, 110.14, 107.56, 42.13, 38.60, 36.47, 28.67, 22.65. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H24N4O4 + H+: 373.1870. Found: 373.1865.

6-(5-((4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)amino)pentanamido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (6f)

Compound 6f was obtained as a pale brown solid (84 mg, 79%) starting from 5g (85 mg, 0.221 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.78 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.37 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.21 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.53 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 3.67–3.54 (m, 4H), 3.20–3.15 (m, 2H), 2.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.69–1.59 (m, 2H), 1.59–1.52 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.74, 168.13, 159.87, 153.27, 138.44, 130.35, 130.10, 127.80, 127.35, 121.56, 120.97, 110.15, 107.56, 42.92, 42.49, 36.39, 28.85, 22.63. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H22N4O4 + H+: 371.1714. Found: 371.1706.

Methyl 6-(3-(3-Guanidinopropyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (7a)

The TFA salt of compound 7a (36 mg, 99%) was obtained starting from 25a (43 mg, 0.077 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.26 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.94 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.24 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.47 (m, 2H, 1H exchangeable with D2O), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.07 (br s, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 6.40 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.11 (m, 4H), 1.70–1.58 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.62, 156.75, 155.32, 152.54, 139.72, 129.70, 128.77, 127.91, 124.63, 121.23, 120.16, 107.22, 106.46, 51.92, 38.44, 36.45, 29.39. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C17H21N5O4 + H+: 360.1666. Found: 360.1659.

Methyl 6-(3-(4-Guanidinobutyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (7b)

The TFA salt of compound 7b was obtained as a yellow solid (39 mg, 97%) starting from compound 25b (49 mg, 0.082 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.30 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.96 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.28 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.52 (m, 2H, 1H exchangeable with D2O), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.06 (br s, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 6.44 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.23–3.03 (m, 4H), 1.60–1.39 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.63, 156.67, 155.18, 152.52, 139.79, 129.70, 128.72, 127.93, 124.58, 121.23, 120.10, 107.08, 106.45, 51.92, 27.04, 26.00. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H23N5O4 + H+: 374.1823. Found: 374.1816.

Methyl 6-(3-(5-Guanidinopentyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (7c)

The TFA salt of compound 7c was obtained as a yellow solid (77 mg, 90%) starting from compound 25c (100 mg, 0.170 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.29 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.91 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.28 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.52 (m, 2H, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.08 (br s, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 6.36 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.15–3.08 (m, 4H), 1.53–1.45 (m, 4H), 1.36–1.31 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.13, 157.19, 155.61, 153.02, 140.33, 130.19, 129.20, 128.44, 125.05, 121.74, 120.58, 107.52, 106.95, 52.41, 41.21, 29.88, 28.67, 23.94. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H25N5O4 + H+: 388.1979. Found: 388.1969.

Methyl 4-Hydroxy-6-(3-(3-(3-methylguanidino)propyl)ureido)-2-naphthoate (7d)

The TFA salt of compound 7d was obtained as a yellow solid (39 mg, 97%) starting from compound 26a (47 mg, 0.082 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.29 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.95 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.27 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.30 (m, 4H, 3H exchangeable with D2O), 6.39 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.20–3.15 (m, 4H), 2.76 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 1.72–1.65 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.12, 156.76, 155.82, 153.03, 140.19, 130.21, 129.28, 128.40, 125.15, 121.73, 120.66, 107.74, 106.96, 52.43, 36.97, 29.89, 28.44. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H23N5O4 + H+: 374.1823. Found: 374.1816.

Methyl 4-Hydroxy-6-(3-(4-(3-methylguanidino)butyl)ureido)-2-naphthoate (7e)

The TFA salt of compound 7e was obtained as a yellow solid (136 mg, 92%) starting from compound 26b (125 mg, 0.250 mmol) following the procedure described for 5a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.30 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.94 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.28 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.21 (m, 4H, 3H exchangeable with D2O), 6.41 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.26–3.08 (m, 4H), 2.74 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 3H), 1.60–1.42 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.63, 156.23, 155.21, 152.53, 139.81, 129.69, 128.72, 127.94, 124.58, 121.23, 120.11, 107.09, 106.45, 51.91, 40.60, 38.59, 27.91, 27.04, 26.01. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H25N5O4 + H+: 388.1979. Found: 388.1972.

Methyl 6-(3-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)propyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (7f)

To a stirring solution of methyl 4-acetoxy-6-((phenoxycarbonyl)amino)-2-naphthoate 22 (400 mg, 1.05 mmol) in dry DMF (4 mL), a solution of 3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-1-amine (263 mg, 2.11 mmol) and TEA (293 μL, 2.10 mmol) in dry DMF (4 mL) was added, and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. NaHCO3 saturated solution was added (25 mL), and the resulting mixture was extracted with AcOEt (3 × 25 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with NaHCO3 saturated solution (2 × 10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a light brown solid that was purified by flash chromatography (gradient AcOEt/MeOH 100:0 to 90:10) yielding a mixture of acetylated and deacetylated compounds. Therefore, the solid was suspended in DCM (15 mL), and piperidine (290 μL) was added. After 1 h, the solvent was removed, and the crude product was diluted with AcOEt (50 mL). The organic layer was washed with 1 N HCl (3× 20 mL) and brine (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure, yielding pure 7f as a white solid (274 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.32 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.87 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.27 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.00–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.56 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 6.36 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 4.02 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.12–3.07 (m, 2H), 1.94–1.87 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.12, 155.65, 153.03, 140.20, 137.75, 130.19, 129.25, 128.87, 128.40, 125.11, 121.72, 120.65, 119.80, 107.70, 106.95, 52.41, 44.16, 36.92, 31.85. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H20N4O4 + H+: 369.1557. Found: 369.1550.

6-(3-(4-Guanidinobutyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (8a)

The TFA salt of compound 8a was obtained as a yellow solid (45 mg, 92%) starting from compound 7b (50 mg, 0.102 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.23 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.94 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 8.27 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.52 (m, 2H, 1H exchangeable with D2O), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.25–6.63 (br s, 3H, exchangeable with D2O), 6.44 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 3.23–3.05 (m, 4H), 1.68–1.39 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.73, 156.66, 155.21, 152.35, 139.50, 129.59, 128.79, 127.73, 125.80, 121.26, 119.95, 107.16, 106.92, 27.06, 26.00. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C17H21N5O4 + H+: 360.1666. Found: 360.1658.

6-(3-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)propyl)ureido)-4-hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid (8b)

Compound 8b was obtained as a yellow solid (62 mg, 89%) starting from compound 7f (72 mg, 0.195 mmol) following the procedure described for 6a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.69 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 10.22 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 9.13 (s, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.89–7.83 (m, 2H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.56 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 6.53 (br t, 1H, exchangeable with D2O), 4.26 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.18–3.13 (m, 2H), 2.05–1.98 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.21, 155.84, 152.87, 139.90, 135.99, 130.06, 129.35, 128.20, 126.36, 122.47, 121.74, 120.65, 120.54, 107.86, 107.42, 46.92, 36.51, 30.94. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C18H18N4O4 + H+: 355.1401. Found: 355.1394.

Methyl (S)-6-(2-((((9H-Fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)-4-(methylthio)butanamido)-4-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)oxy)-2-naphthoate (9a)