Abstract

In the past several decades, three-dimensional (3D) printing has provided some viable tissues and organs for repairing or replacing damaged tissues and organs. However, the construction of sufficient vascular networks in a bioartificial organ has proven to be challenging. To make a fully functional bioartificial organ with a branched vascular network that can substitute its natural counterparts, various studies have been performed to surmount the limitations. Significant progress has been achieved in 3D printing of vascularized liver, heart, bone, and pancreas. It is expected that this technology can be used more widely in other bioartificial organ manufacturing. In this review, we summarize the specific applications of 3D printing vascularized organs through several rapid prototyping technologies. The limitations and future directions are also discussed.

Keywords: 3D printing, Vascularized organs, Organ manufacturing, Tissue engineering, Stem cells

1. Introduction

Organ is a collection of tissues that structurally form a functional unit specialized to perform one or more particular functions. A few typical examples of organs include sensory organs, internal organs, hollow organs, and support organs. Organ failure of liver, heart, kidney, and lung accounts for over millions death worldwide annually and has resulted in huge burden in health care. There is a booming demand of donors for organ transplantation[1]. For example, about 1.5 million patients in our country (China) who need to receive organ transplants each year, but <1% of them can get suitable donors[2]. It is significantly challenging to fulfill the needs for transplantation just from human donors. To solve the problem of organ shortage, great efforts have been made to create bioartificial organs with multiple cell types, biocompatible materials (i.e., biomaterials), and advanced biotechnologies[3,4]. Especially, patient-specific cells can be cultivated in the laboratory and combined with biomaterials for personalized manufacturing and malfunctional organ restoration. This became the prototype for customized organ engineering in three-dimensional (3D) printing areas.

Despite the improvement of the quality of human life, the repair of organ defects caused by diseases, congenital malformations, and traffic accidents has become a huge social burden, which forms a powerful driving force for the development of 3D printing or manufacturing of human organs[5,6]. The principal target of organ manufacturing lies in developing fully functional bioartificial organs that are sustainable in vivo[7]. Some parts of organs, such as the bone, skin, heart, and others, have been constructed[8]. However, only a few of these studies have successfully translated the bioartificial organs from the laboratories into clinical applications[9,10]. This is because vascularized networks are the fundamental basis for the constant supplementation of oxygen and nutrients to the cells[8,11]. The insufficiency of functional blood vessels in the 3D constructs had obstructed the translation from experimental organs into clinical application[12]. Physically, vascular networks can be constructed from endothelial cells (ECs) or the germination of existing blood vessels[12]. The living cells survive within the limitation of 100 – 200 μm oxygen diffusion[13]. Therefore, it is vitally important to meet the requirements for the cells to be biologically functional inside the 3D constructs.

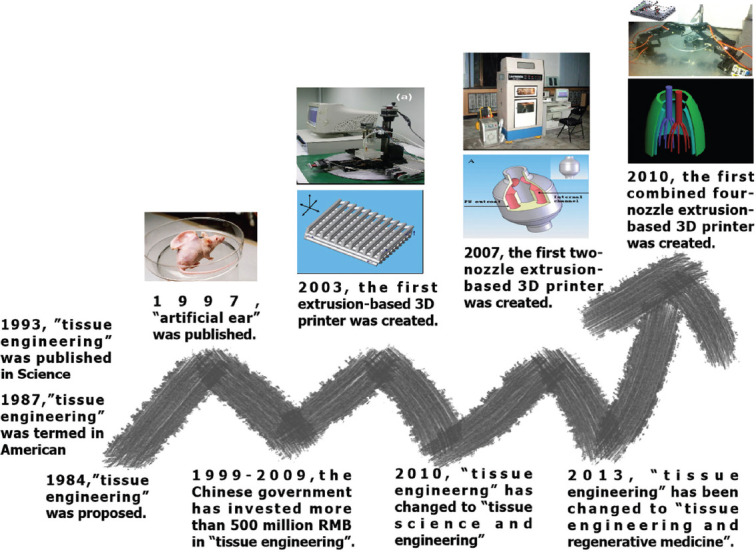

To achieve functional, consistent, and reproducible techniques for generating vascular networks in 3D printing organs, massive financial and intellectual supports are required for specific building materials and unique structural designs. 3D bioprinting has so far provided the most advanced solution for the generation of vascular network due to the controllability, reproducibility, and repeatability (Figure 1). Until present, the combination of different 3D printing techniques with various cell-laden hydrogels has enabled the fast formation of branched vascular networks[8], however, the complexity and functionality of the capillaries have been challenging to be completely simulated. In this review, we present the promising 3D printing strategies for vascularized organ construction. The importance of the manufacturing condition, printing accuracy, and material biocompatibility that are necessary for building vascular networks has been highlighted. The limitations and prospects for future complex vascularized organ manufacturing have also been emphasized.

Figure 1.

The development of tissue engineering and 3D bioprinting.

2. Physiological characteristics of vascular system

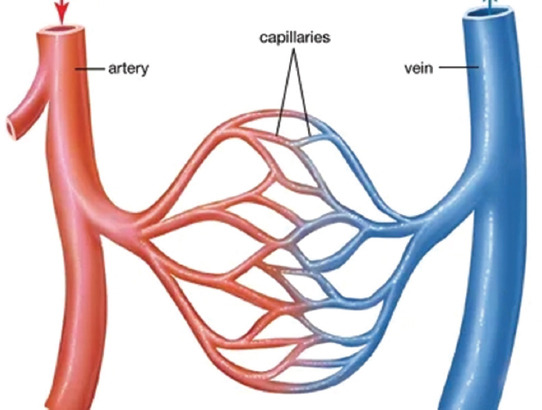

Natural vascular system contains branched vascular trees with more than 3 types of cells that coordinate simultaneously to support the transportation of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic wastes throughout the body[14] (Figure 2). The effectiveness of the bioartificial vascular network relies on how close the functional simulation to the physiology. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the development of natural blood vessels is of great significance for both the design of a stable internal environment and the functional implementation of the vascular networks[15].

Figure 2.

Circulatory system in human organs.

2.1. Vascular trees

As shown in Figure 2, the vascular network is a series of branched vessels in the human or animal body in which blood circulates. In general, the large vascular vessels that carry blood away from the heart are called arteries, and their very small branches are known as arterioles. Meanwhile, the very small branches that collect the blood from the various organs are called venules. The venules unite to form veins, which return the blood to the heart. Among which, the unidirectional valve in the meridians can effectively promote the blood returns to the heart. Capillaries are the minute thin-walled vessels that connect the arterioles and venules. It is through the capillaries that nutrients and wastes are exchanged between the body organs.

There are many branched tree-like blood vessels in an internal organ, such as the liver, heart, and kidney. The branched tree-like blood vessels can be divided into three main parts according to their internal diameters, blood pressures, and physiological functions: (i) Arteries (diameter > 1 mm), which maintain the highest blood pressure in the organ and function as the carrier of blood to the peripheral tissues; (ii) veins (diameter > 1 mm), which return the blood to the cardinal veins; and (iii) capillaries (diameter between 10 and 15 µm), which connect the arteries and veins, and provide nutrients for most of the parenchyma cells. Between the large blood vessels and capillaries, the diameters of arterioles and venules often range from 0.3 to 1 mm.

Emphasis should be given to the arteries, which have three obvious layers in their vessel walls with different cell types and biomolecules or extracellular matrices (ECMs). The outermost layer, adventitia, is composed of fibroblasts, nerve fibers, and ECMs with a lot of collagen, which can effectively maintain vascular morphology and increase vascular elasticity. The middle membrane, tunica media (or elastica), is mainly composed of smooth muscle cells and pericytes. It has unique cardiac protective functions such as angiogenesis and chronic inflammation alleviation with the thickest structure. The innermost layer, intima, is mainly consisted of ECs, which plays an important role in regulating blood flow, platelet, and blood cell function[16].

2.2. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis

In human body, neovascularization is the formation of functional microvascular networks with red blood cell perfusion. The formation of microvascular networks is generally through two physiological processes, that is, vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. In the early embryonic stage, blood vessels develop de novo at the same time as hematopoiesis[17,18]. Endothelial progenitor cells and hematopoietic stem cells (or angioblasts) aggregate to form distinct blood islands in the liver. ECs gradually fuse and form lumen structures within the ECMs and subsequently develop the primitive capillary plexus[17]. This process is called vasculogenesis, in which the blood vessel forms through embryonic differentiation of ECs. Angiogenesis is another type of neovascularization, in which the blood vessel forms through the proliferation and migration of ECs from the existing mature vessels in tissues. The latter happens any time during an organism’s life except the embryonic stage and can repair the damaged vascular networks. As the germination of the blood vessels develops, ECM remodeling plays a key role in the angiogenesis process to form the circulatory system[19].

In the process of angiogenesis, blood vessel expansion is actively regulated by cell interactions and the ECM microenvironment. The secretion of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) from vascular ECs regulates the Notch signaling pathway and influence cell proliferation and migration[20]. Besides, ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells secrete the platelet-derived growth factor to recruit stromal cells and stabilize the vascular networks[21]. The perivascular stromal cells function as the stabilization and increase the pro-angiogenic factors, this not only stabilizes the microstructures of the vascular networks but also dilates the blood vessels[22]. Apart from vascular chemokines, ECM provides structural support for ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells, and plays a critical role in the process of vascular remodeling, expansion, and extension. The membrane of the basement vascular is in the dynamic balance of disruption and formation. The interaction of plasma-derived fibrinogen, vitronectin, and fibronectin results in a provisional matrix that supports angiogenesis[23-25].

Since the vascular networks can be created through vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, it is necessary to choose the appropriate strategy according to the normal physiological characteristics of the target organs. In organ 3D printing, the “bioinks” used in 3D printing of vascular networks should present the special hierarchical vascular structure generation capability to promote cell accommodation, survival, growth, and differentiation. Besides, the biochemical properties of the polymeric “bioinks” should conform to specific engineering configures, which are biocompatible, biodegradable, and feasible for implantation. The selection of versatile “bioinks” will be discussed in the following section.

2.3. Blood vessels and cell sources

As stated above, the blood vessels can be classified into arteries, veins, and connecting capillary networks with different dimensions and layers to fulfill various biochemical and biophysical functions[26,27]. For vascular 3D printing, it is important to take into account the differences in blood vessel types associated with their specific physiological functionalities when designing an extracorporeal vascular system. The selection of cell types needs to be taken into serious consideration according to the targeted organs, especially for capillary construction. To make sure that the 3D-printed bioartificial organs are fully functional, sufficient blood supply is critical for stabilizing the cell survival microenvironments. For arterial blood vessel construction, a large amount of smooth muscle cells is necessary to form a thick concentric elastic muscle wall, and effectively cope with high blood pressure and lateral shear stress. In contrast, ECs in the vein are surrounded by a thin layer of smooth muscle cells with medium mechanical properties. Until present, it is hard to mimic the one direction valves in the veins to prevent backflow and promote circulation of blood[28].

In the vascular networks of a natural organ, the capillary wall is the thinnest, only composed of ECs, perivascular cells, and ECMs. The stability of the capillary is mainly dependent on the arrangement of ECMs. The velocity of blood in capillaries is relatively slow for efficient oxygen and nutrition perfusion[29]. Until the present, constructing a complete vascular network with delicate capillaries through 3D printing is still challenging.

ECs are one of the basic elements of vascular composition. As the innermost cells of the vascular walls, ECs are widely involved in various physiological activities of blood vessels. It is, therefore, one of the important cell types in 3D printing vascular networks[30]. In general, ECs are derived from endothelial progenitor cells, which are derived from the supportive cells in bone marrow[31]. Endothelial progenitor cells can be significantly regulated by laminar shear stress and promote vasculogenesis. Yamamoto et al. proved that laminar shear stress can effectively animate the proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells and promote the migration of ECs[32]. Thus, a dynamic microenvironment has a positive influence on vasculogenesis. VEGF is an important angiogenic activator secreted by ECs and can induce EC chemotaxis. In 3D printing, exogenous VEGF can also be used to accelerate the formation of the expected vascular networks.

Smooth muscle cells are very important in the outer layer of ECs in large blood vessels. These cells can self-migrate and integrate, and have important physiological functions during the processes of large vessel formation and vasodilation. After 3D printing, coculture of different types of cells, especially vascular cells, in a construct can effectively simulate the physiological environment and promote angiogenesis. For example, the coculture of ECs and human mesenchymal stem cells can stimulate cell viability and activate angiogenesis[30,33]. Levenberg et al. cocultured myoblasts, embryonic fibroblasts, and ECs in the ratio of 40:13:47 on poly-L-lactic acid/polylactic-glycolic acid (PLGA) scaffolds and achieved a maximize vascularization in a mouse model[34]. Consistent vessel generation was achieved in the transplantation. The vascularization level was measured in terms of the EC areas, the number of lumens, and the total lumen area. In another study, ECs were cocultured with keratinocytes and fibroblasts on a porous collagen scaffold[35,36]. When the 3D-printed bioartificial skin was implanted in animals, the vascular network fused with the vasculature of the host. It was found that porous structures, such as hollow channels within silk fibroin scaffolds, could also effectively increase the adhesion of ECs, and promote angiogenesis with vascular cell fusion after transplantation[37]. These studies indicated that the coculture of functional parenchymal cells of the target organs with ECs could activate vascular network generation and stabilization when the combinations were transplanted in vivo.

3. 3D printing technologies and “bioinks”

3.1. 3D printing technologies

3D printing, also named as rapid prototyping (RP), solid freeform fabrication, or additive manufacturing, is based on the dispersion-accumulation (i.e., discrete accumulation) principle of computer-aided manufacturing techniques. Before 3D printing, an object can be divided into numerous two-dimensional (2D) layers by computers with a defined thickness. These 2D layers can be piled up by selectively adding the desired materials in a high reproductive layer-by-layer manner under the instruction of computer-aided design (CAD) models[38-40].

Based on the working principles, 3D printing technologies can been divided into several classes: (i) Extrusion-based 3D printing; (ii) inkjet-based 3D printing; (iii) selective laser sintering (SLS); (iv) fused deposition modeling (FDM); and (v) stereolithography apparatuses (SLAs). At present, only extrusion-based 3D printing techniques have been widely used for vascularized organ construction[41-43].

(1) Extrusion-based 3D printing

Extrusion-based 3D printing is an automatic fluid dispensing system, in which polymeric materials are selectively dispensed through one or more nozzles or orifices. Different form FDM, the extrusion-based extrusion processes do not involve any heating procedures except for special circumstances. Polymer solutions or hydrogels with or without cells, growth factors, and other bioactive agents can be extruded through nozzles by pneumatic pressure or physical force (i.e., a piston or screw) in a controllable manner[44]. The printing system generates continuous filaments under the control of CAD models. At present, this kind of 3D printing is capable to deposit multiple living cells along with biocompatible polymers with very high cell densities. The solidification of polymer solutions or hydrosols is achieved through a series of physical and/or chemical procedures, such as sol-gel transformation (i.e., physical crosslinking), polymerization, chemical crosslinking, and enzymatic reaction, before, during, or after 3D printing[45-47].

The main objective of extrusion-based organ 3D printing technologies is to print cell-laden hydrogels along with other biomaterials in layers using CAD models. Recent advances in the development of the multi-nozzle 3D printers have significantly enhanced their applications in producing large scale-up vascularized organs, such as the skin, liver, heart, lung, and pancreas[48-51].

The advantages of extrusion-based 3D printing in vascularized organ construction include high cell densities, large scale-up structures, and extremely sophisticate compositions. A large number of biomaterials, including cells, growth factors, and other bioactive agents, can be simultaneously deposited with polymeric solutions or hydrogels. With the increase of extrusion nozzles, a variety of heterogeneous constructs with multiple polymer and cell types can be constructed. Many researchers have addressed the effects of extrusion process parameters, such as speed of 3D dispensing, pressure, temperature, nozzle size, viscosity, and shear thinning of polymeric solutions or hydrogels, on cell viabilities[52-55].

(2) Inkjet-based 3D printing

Inkjet-based 3D printing is a non-contact AM technique, adapted from industrial 2D printers, in which droplets of building materials are selectively deposited. Example materials include photopolymers and waxes. By changing the content of “inks,” cells and polymers can also be patterned into desired shapes[56]. Until present, most of the inkjet-based 3D printers are used for printing tissue engineering scaffolds for cell seeding. Limited by the soft hardware systems of the commercially available 3D printers, inkjet printheads with multiple nozzles can hardly be updated to increase the printing complexity and construct size.

There are many limitations for the inkjet-based 3D printing technologies to be used for vascularized organ construction. These limitations include low polymer viscosity (ideally below 10 centipoise), low cell density (<10 million cells/mL), and low structural heights (<10 million cells/mL)[57]. To provide a higher polymer concentration or cell density, crosslinking agents are often used, resulting in some drawbacks, such as blocking the nozzles and changing the material properties[58,59].

(3) Laser-assisted printing technology

The technological base of laser navigated 3D printing is laser-induced interaction. It adopts a specific “Ribbon,” which is composed of metal (i.e., gold or titanium), a laser energy absorption layer, and “ink” at the bottom. The metal layer was evaporated by laser to induce the formation of “bioink” droplets and deposited on the collecting substrate. Compared with other 3D printing technologies, this technique is relatively effective in arranging single cells, including human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) and ECs, thus, it may offer some advantages in the construction of capillaries[60].

(4) SLA

In the process of 3D printing, the commonly used materials for SLA are polylactic acid, polyhexyl acetate, protein, and polysaccharide. This technique is often used for producing tissue engineering scaffolds. The scaffolds generated with laser energy, even though are not mechanically robust, provide precise control of resolution. Compared with the above-mentioned inkjet-based 3D printing, the microscale laser tip is advanced in printing accuracy. However, the limitation of this technique in vascularized organ construction is that polymers have to be photopolymerizable to generate solidified layers in the reservoir. Living cells cannot be 3D-printed directly. Besides, the microstructures can be easily distorted or shrunk when they are excessively exposed to the laser energy[61].

3.2. Biochemistry characteristics of the “bioinks”

Compared with the traditional industrial manufacture, 3D printing can precisely arrange living cells, biological polymers, and bioactive agents under the control of a CAD model in a layer-by-layer fashion. It can produce bioartificial organs with specialized biomaterials, complex shapes, and internal microstructures[62].

To achieve the ideal functionality and biocompatibility of the “bioinks,” special characteristic requirements need to be fulfilled for the generation of vascularized organs. Most critically, biomaterials should show the inherent characteristics for vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and biofunction of natural blood vessels. Natural hydrogels, comprised collagen, gelatin, elastic fibers, elastic lamellae, and proteoglycan, have been used frequently as organ printing “bioinks”[63]. The activity, proliferation, and differentiation of cells in the “bioinks” are one of the main factors affecting organ functions. Besides, thin printing filaments of polymers have become the mainstream for lowering cell apoptosis due to the nutrient permeation capabilities. In addition to the branched vascular networks, a “bioink” should possess the characteristics of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and biostability. Therefore, polymers occupy the preponderance of “bioinks” for their inherent engineering properties.

Natural polymers have many advantages for being used as “bioinks” for bioartificial organ 3D printing. First, they are widely available and can be easily extracted from animals, crustaceans, trees, and microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi. Second, natural polymers are biodegradable, biocompatible, and chemically/physically/enzymatically cross-linkable with different biofunctional groups. Third, most of the natural polymers can dissolve in water, the resulting solutions can be easily transformed to hydrogels, for accommodating cells with no harms. Fourth, the biodegraded products of natural polymers can be recycled or discharged by human bodies. One limitation of natural polymers for vascularized organ construction is that the mechanical properties of the cell-laden hydrogels are too low to be anti-suture. To overcome this shortcoming, synthetic polymers are often employed to improve the biophysical properties of the 3D-printed constructs[64].

To generate proper “bioinks” for vascularized organ 3D printing, biomechanical features of the 3D printable polymers are the primary consideration for the application of the vascular networks. Biocompatibility of the polymers can effectively maintain cell viability, degradability, as well as promotes cell proliferation and vascular network formation. As for tissues with abundant capillary networks, such as liver and kidney, multitubular structures are often needed. Therefore, the printing accuracy, setting speed, and crosslinking capability of the “bioinks” are all needed to be considered[65]. Printability plays a critical role in regulating the fabrication process of the vascular networks. A series of organ manufacturing theories that involve cell-laden polymer solution solidification and crosslinking mechanisms have been proposed by Professor Wang[66].

3.3. Approach of vascular network 3D printing

There are two approaches for vascularize network 3D printing, direct printing and indirect printing. Direct printing has fewer requirements in manufactory steps as it generates the vascular networks in a continuous, layer-by-layer process. Direct printing can be widely used in all printing systems with outstanding feasibilities during and after printing. On the contrary, indirect printing utilizes a sacrificial template to achieve an advantage in geometrical and microfluidic perspectives compared with direct printing. The accurate of the external structures is restricted.

Vascularized organs with blood vessels can be effectively generated using a direct approach. Suri et al. fabricated a microchannel incorporated 3D scaffold using glycidyl methacrylate hyaluronic acid[67]. The utilization of pre-patterned substrate within the SLA system introduced the partial photopolymerization of the “bioinks.” Layers were incorporated with the process of consecutive deposition-wash-off deposition. Various microstructures with different internal patterns are printable in sandblasted and acid-etched SLA[68]. Laschke et al. generated PLGA-based scaffolds and created angiogenetic vascular networks with the additive of growth factors[69]. Gravity is the common cause of the pleated in the microlayer and the micronozzles are easily blocked causing an erratic fluid stream. To eliminate the obvious issues in the direct horizontal 3D printing system, Hinton et al. introduced a modified thermoplastic extrusion-based 3D printing system[70]. The extra syringe pump extrusion system is integrated with gelatin microparticles for 3D printing using cell-laden hydrogels as the “bioinks.” The direct printing platform was highly functional in generating coronary-like vascular trees and other complex curvilinear structures with hydrogels.

The indirect printing approach utilizes sacrificial materials to generate a specific template with the desired geometrical features. The non-sacrificial “bioinks” are printed around the sacrificial template. Afterward, the sacrificial template is removed. In the circumstances of vascular network generation, some sacrificial templates are effective in the creation of complicated networks simulating in vivo vasculature. For instance, microchannels with opening ends were precisely generated utilizing the liquefaction temperature difference between the polydimethylsiloxane substrate and the gelatin mesh[71]. The gelatin mesh with micromodulation is one of the commonly used sacrificial materials. In another study, after collagen hydrogel was encapsulated in the gelatin template and heated up to 37°C, interconnected channels formed when the gelatin was removed using phosphate-buffered saline. ECs were implanted in the channels and perfused through a microfluidic method and demonstrated certain viability[72]. Likewise, various studies have proven that gelatin is a suitable sacrificial material as impermanent template for collagen-based vascular generation[73,74].

Even though the utilization of a sacrificial template is superior in geometrical and microfluidic aspects, constraints such as fabrication and feasibility are still encountered in the post-printing processes. The accurate modification on the external of the vascularized network is difficult to conduct because of the surroundings of the hydrogel. Besides, an effective approach is needed to connect blood vessels by simulating natural vascular networks with a complex design. Most of the previous studies are concentrated on the vascularized networks which are placed horizontally or stacked vertically. These are limited methods to simulate the complexity of natural vascular networks.

4. Vascularized organ 3D printing and applications

Clinically, bioartificial vascular grafts should have the following characteristics: (i) Excellent blood compatibility with no or a lower risk of thrombosis; (ii) sufficient mechanical properties and anti-suture strength; (iii) high-grade biodegradability and tissue restoration capability; (iv) non-toxicity and no immune rejection with the dissolved, exudated, and degraded products; and (v) simple preparation method, wide source of materials, and low price[75].

To simulate and function of the natural organs, the 3D-printed vascular networks ought to provide supplements and oxygen for the tissues and remove the cell wastes and carbon dioxide. The robust generation of a permeable vascular network is critical for the 3D printing vascularized organs[12]. 3D printing of a vascular network requires high precision since the limitation of cells to capillaries is within 200 μm[8]. Limited by the diffusion ability of oxygen and nutrients, the widening of the distance between cells and capillaries may lead to hypoxia and apoptosis. Under the background of delayed autophagic digestion of apoptotic debris, further aggravation of the necrosis may set up a vicious circle.

In organ 3D printing, the hierarchical architecture integration of the different parts of the vascular network is critical. It requires precise geometrical and functional control of the building processes, especially at the submicron level. In the following section, we mainly introduce the technologies used to construct the 3D vascular networks, including cardiovascular systems, vascularized liver tissues, vascularized bones, and vascularized pancreas. The innovation of these techniques in printing complex structures and functional characteristics is analyzed.

4.1. Cardiovascular system

According to the World Health Organization statistics, cardiovascular diseases are among the highest incidence and mortality rates in the world[76]. More than 17 million people die of heart diseases every year. Cardiovascular diseases have become the leading cause of death in developed countries, accounting for about 40% of the total number of deaths. More than 1.4 million vascular grafts are needed a year in the United States alone[77]. In China, the lower limb venous diseases and coronary artery bypass surgeries have increased dramatically along with the congenital heart disease rate 6.7/thousand[78]. The clinical demand for the vascular graft is increasing prominently. 3D printing of vascular structures can effectively solve the problem of graft shortage.

At present, autologous transplantation or allogeneic transplantation is mainly adopted in clinical vascular transplantation, and the source of donors is greatly restricted. The myocardium, endocardium, and pericardium are the primary cells that constitute the heart. A high-density capillary network (3000 vessels/mm2) located in the myocardium functions to regulate the metabolic activity of contraction and works to confine the distance between cardiomyocytes and ECs within a range of 2 – 3 μm. Therefore, along with the development of 3D vascularized networks, the replacement of these cardiovascular tissues using 3D printing technology has been considered as an important issue in the clinical perspective. The use of 3D printing technology can easily and quickly produce transplantable blood vessels, including vascular networks.

3D printing heart tissues have been a long-term dream for many researchers. Professor Norotte of Columbia University developed a 3D printing technology of biogel spheres based on the 3D automatic computer-assisted deposition. This technology has repetitive and quantifiable advantages in the printing of non-stents small diameter blood vessels[38]. Mironov et al. used a modified inkjet printer to print a layer of vascular ECs on a layer of matrix material, forming a quasi-3D structure similar to a doughnut[79]. A Japanese researcher imitated and modified this process to manufacture the inkjet printers, which are characterized by fast response speed, high forming accuracy, high solidification speed, and low viscosity of forming materials[80]. However, this technology is still in its infancy due to the defects in mechanical strengths, anticoagulant properties, degradation rates, and processability. Leong et al. analyzed the suitable polymers for SLS technology for manufacturing vascular stents[81].

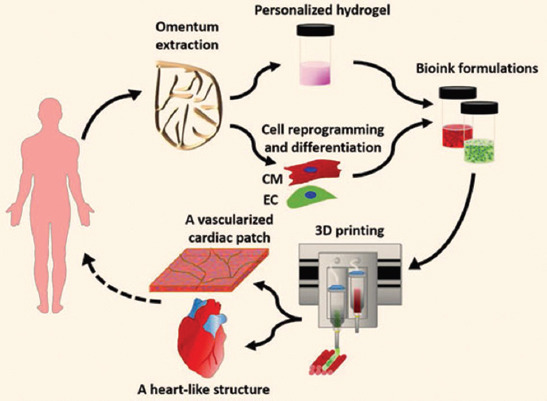

In 2019, researchers at Tel Aviv University announced a breakthrough in heart 3D printing. The authors claimed that they have printed a whole living heart with the vascular networks (Figure 3)[82]. This report has captured the attention worldwidely. However, it is just another development branch of the extrusion-based RP technology developed in Tsinghua University in 2003. The printing process occurs in a medium instead of air. The obvious differences of this technique with the former reported series of RP techniques developed in Tsinghua University include polymeric materials, cell types, and CAD models. The movement of blood has been mimicked but the vascular networks are totally forged without any living cells. Thus, 3D printing of thick vascularized heart tissues that can fully match the patient still remains an unmet challenge in cardiac organ engineering.

Figure 3.

Omentum tissue is extracted from the patient and while the cells are separated from the matrix, the latter is processed into a personalized thermoresponsive hydrogel, the cells are reprogrammed to become pluripotent and are then differentiated to cardiomyocytes and ECs, followed by encapsulation within the hydrogel to generate the bioinks used for printing, the bioinks are then printed to engineer vascularized patches and complex cellularized structures, the resulting autologous engineered tissue can be transplanted back into the patient, to repair or replace injured/diseased organs with low risk of rejection. (from ref. [82] licensed under Creative Commons Attribution license).

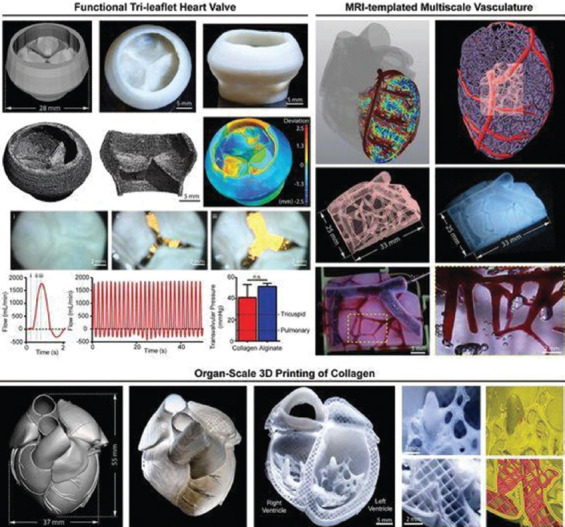

Collagen is a major component of human ECMs. However, it is hard to replicate the structure and function of human organs using collagen solutions due to the special solidification properties of collagen molecules. In 2019, Lee et al. described a 3D printing technique to build complex collagen scaffolds to engineer biological heart tissues[83]. They presented a method to 3D print collagen using freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels (FRESHs) to engineer components of the human heart at various scales. Control of pH-driven gelation provides 20 µm filament resolution, a porous microstructure that enables rapid cellular infiltration and microvascularization. The FRESH 3D-bioprinted hearts accurately reproduce patient-specific anatomical structure as determined by micro-computed tomography. Cardiac ventricles printed with human cardiomyocytes showed synchronized contractions, directional action potential propagation, and wall thickening up to 14% during peak systole (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

3D printing of human hearts. Republished with permission of American Association for the Advancement of Science, from 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart, Lee A, Hudson AR, Shiwarski DJ, et al., Vol. 365 No. 6452, 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

It was found that collagen gelation was controlled by modulation of pH and could provide up to 10 µm resolution on printing. Cells could be embedded in the collagen hydrogel and introduced into the scaffold through embedding of gelatin spheres. This technique is similar to the double-nozzle 3D printer developed in Tsinghua University, in which two different materials have been printed[3,43,47]. However, the vascular networks, including capillaries, are hard to be printed using the collagen hydrogels. There is a long way for the multiscale vasculature and trileaflet valves to be used clinically.

Many other 3D printing heart tissues are still on the way. For example, Duan et al. used a flat-shaped model to print trileaflet valve conduits using a combination of methacrylated hyaluronic acid and methacrylated gelatin with encapsulation of human aortic valve interstitial cells[84]. Stiffness and adhesivity control aortic valve interstitial cell behavior within hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels have been achieved. Hockaday et al. used axially symmetric shape and a combination of 700 and 8000 Mw poly(ethylene glycol)diacrylate to print valve conduits with biomechanical heterogeneity, where the leaflets were more flexible, while the root remained relatively rigid[85]. However, evidence has shown that vascularized heart 3D printing still faces many challenges, such as the real vascular network construction, the anti-thrombotic material selection, and physiological function realization.

4.2. Lung

The lung is a very complex internal immunologic organ who responds in a variety of ways to inhaled antigens, infectious materials, or saprophytic agents. It’s commonly known that certain diseases are linked with occupations like lung disease in coal miners. Until present, there are few references for lung 3D printing.

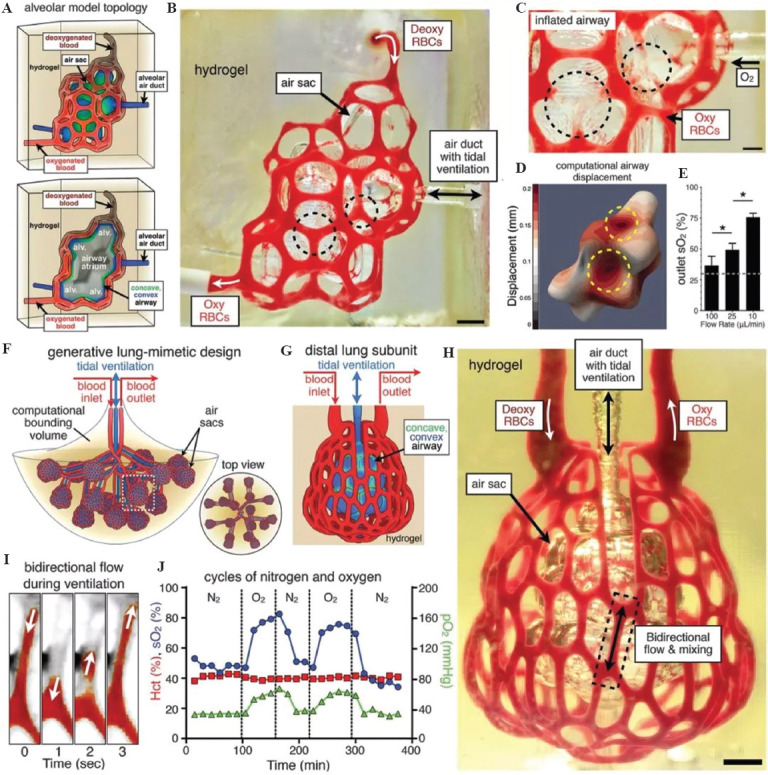

In 2019, Grigoryan et al. established an intravascular and multivascular design freedoms with photopolymerizable hydrogels using food dye additives as biocompatible photoabsorbers[86]. They demonstrated that monolithic transparent hydrogels, produced in minutes, can efficiently mimic the intravascular 3D fluid mixers and bicuspid valves. Nevertheless, they are not the true vascular networks with the typical features of arteries, veins, and capillaries. It is far away for these constructs to be used as bioartificial lungs for anti-suture implantation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A-J) 3D printing of human lungs. Republished with permission of American Association for the Advancement of Science, from Multivascular networks and functional intra vascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels., Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, et al, Vol. 364 No. 6439, 2019 ; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

4.3. Liver

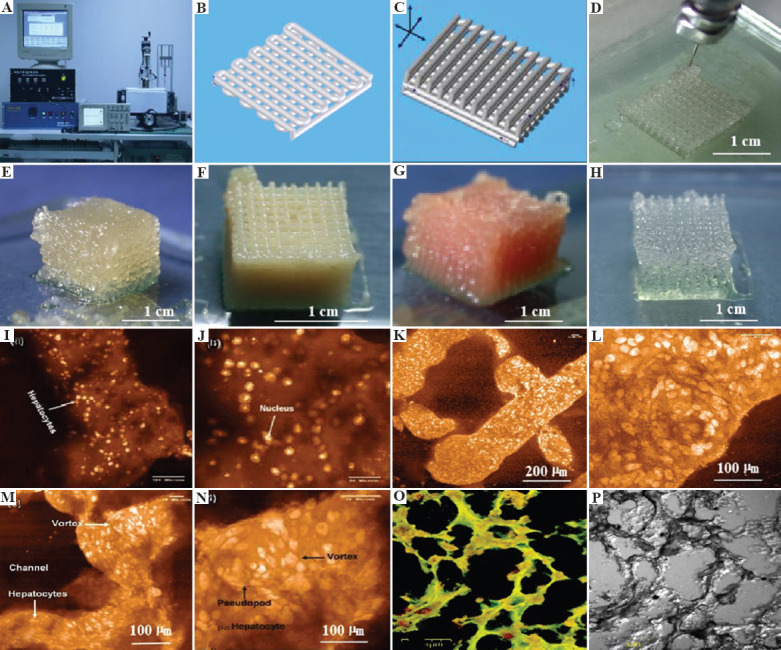

The liver is regarded to be the most vital organ for its critical multiple biological functions in metabolism and metabolic regulation. 3D bioprinting of livers is one of the research hotspots with relatively rapid progression. The first liver pertinent 3D printing technology was reported in 2005 in which alginate was used as an additive in gelatin-based cell-laden “bioinks” (Figure 6)[87-89]. This is also the first scale-up larger hepatic tissue construction report using extrusion-based RP techniques and cell-laden hydrogels. With the instruction of CAD models, a brand new era for fully automatic manufacturing of bioartificial organs has begun. The RP techniques together with the resulted living constructs have been later used widely in many biomedical fields, such as controlled cell transplantation, high-throughput drug screening, customized organ restoration, pathological mechanism analysis, and long-term bioartificial tissue/organ cryopreservation[90-93]. Thus, it is a fundamental breakthrough in large scale-up organ 3D printing.

Figure 6.

3D bioprinting of chondrocytes, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, and adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) into living tissues/organs using a pioneered 3D bioprinter made at Prof. Wang’s laboratory in Tsinghua University: (A) The pioneered 3D bioprinter, (B) schematic description of a cell-laden gelatin-based hydrogel being printed into a grid lattice using the 3D bioprinter, (C) schematic description of the cell-laden gelatin-based hydrogel being printed into large scale-up 3D construct using the 3D bioprinter, (D) 3D printing process of a chondrocyte-laden gelatin-based construct, (E) a grid 3D construct made from a cardiomyocyte-laden gelatin-based hydrogel, (F) hepatocytes encapsulated in a gelatin-based hydrogel after 3D printing, (G) hepatocytes in a gelatin-based hydrogel after 3D printing, (H) a gelatin-based hydrogel after 3D printing, (I-P) hepatocytes in some gelatin-based hydrogels after certain periods of in vitro cultures. Reprinted from, Cryobiology, Vol 61 Issue 3, Wang X, Xu H, Incorporation of DMSO and dextran-40 into a gelatin/alginate hydrogel for controlled assembled cell cryopreservation, 345-351., Copyright (2010), with permission from Elsevier.

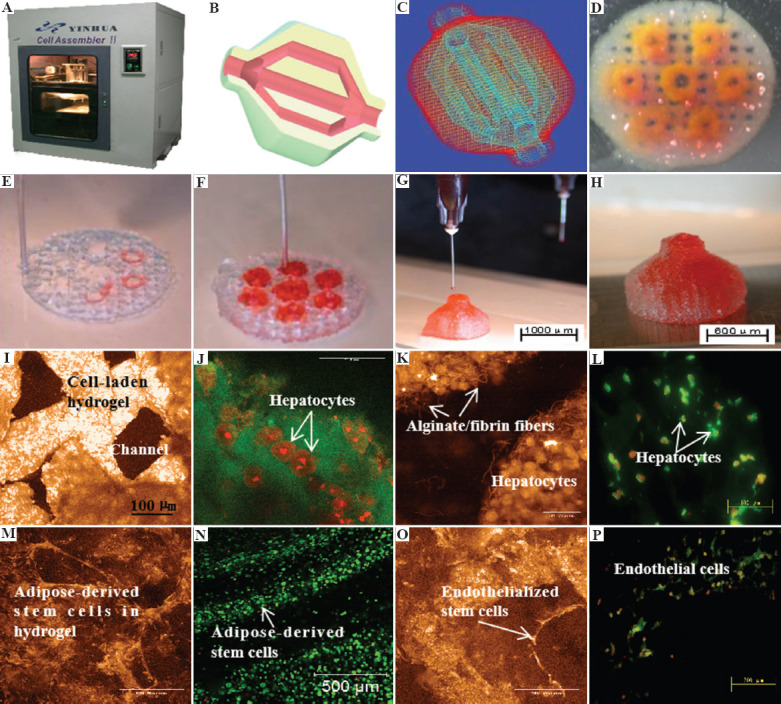

In 2009, a double-nozzle/syringe RP technique was created at Professor Wang’s laboratory. Since then, various gelatin-based composite “bioinks,” such as gelatin/alginate, gelatin/fibrin, gelatin/chitosan, gelatin/hyaluronate, and gelatin/alginate/fibrin, gelatin/alginate/dextron (glaycerol or dimethyl sulfoxide), have been explored for bioartificial organ, especially liver, manufacturing (Figure 7)[94]. The viscosity of the gelatin-based “bioinks” depends largely on the polymer concentration, molecular weight, and cell density. A series of two-step stabilization strategies, containing both the thermosensitive physical and ionic chemical crosslinks, for the 3D-printed constructs have been exploited. The chemical crosslinking methods include glutaraldehyde for gelatin, CaCl2 for alginate, sodium tripolyphosphate for chitosan, and thrombin for fibrinogen. Ten years later, this classical RP principles, the hydrogel solidifications, the “bioink” formulations, and the polymer crosslinking strategies have been extensively adapted by many other groups[95-99].

Figure 7.

A large scale-up 3D-printed bioartificial organ with vascularized liver tissue constructed through the double-nozzle 3D bioprinter created in Tsinghua University, Prof. Wang’s laboratory: (A) The double-nozzle 3D bioprinter, (B) a CAD model containing a branched vascular network, (C) a CAD model containing the branched vascular network, (D) a few layers of the 3D bioprinted construct containing both adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) encapsulated a gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel and hepatocytes encapsulated in a gelatin/alginate/chitosan hydrogel, (E-H) 3D printing process of a semi-elliptical construct containing both ASCs and hepatocytes encapsulated in different hydrogels, (I-L) hepatocytes encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogels after 3D bioprinting and different periods of in vitro cultures, (M-P) ASCs encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogels after 3D bioprinting and different periods of in vitro cultures as well as growth factor inductions. Li S, Yan Y, Xiong Z, et al, J Bioact Compat Polym (24:84–99), Copyright © 2022 by SAGE Publications. Reprinted by permission of SAGE publications.

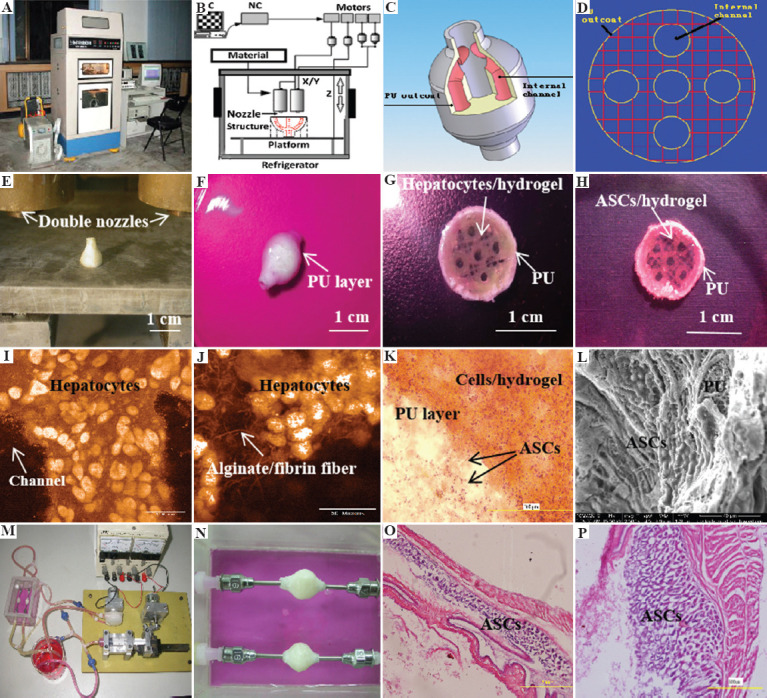

A critical limitation of the 3D-printed cell-laden hydrogels for organ manufacturing is the notorious weak mechanical properties of the products without anti-suture and anti-stress functions. A practicable solution is to integrate mechanical strong enough synthetic polymers into the 3D constructs. However, most synthetic polymers, such as PLGA and polyurethane (PU), do not have sol-gel transition (or phase transformation, traditionally glass transition) temperatures between 1°C and 10°C. To overcome this shortcoming, Professor Wang has explored several series of low-temperature deposition manufacturing technologies equipped with one, two, or more extrusion nozzles[50,100-104]. Under the low-temperature conditions, such as minus 20 – 30°C, both natural and synthetic polymers are frozen and distributed into predefined space to form elaborated 3D constructs (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

A large scale-up 3D-printed complex organ with vascularized liver tissue constructed through the double-nozzle 3D bioprinter created at Prof. Wang’s laboratory in Tsinghua University: (A) The double-nozzle 3D bioprinter, (B) a computer-aided design (CAD) model containing a branched vascular network, (C) a CAD model containing the branched vascular network, (D) a cross-section of the CAD model containing five sub-branched channels, (E) working platform of the 3D bioprinter containing two nozzles, (F) an ellipse sample containing both a cell-laden natural hydrogel and a synthetic polyurethane (PU) overcoat, (G) several layers of the ellipse sample in the middle section containing a hepatocyte-laden gelatin-based hydrogel and a PU overcoat, (H) several layers of the ellipse sample in the middle section containing an adipose-derived stem cell (ASC)-laden gelatin-based hydrogel and a PU overcoat, (I) hepatocytes encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogel, (J) a magnified photo of (I) showing the alginate/fibrin fibers around the hepatocytes, (K) ASCs encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogel growing into the micropores of the PU layer, (L) ASCs on the inner surface of the branched channels, (M) pulsatile culture of two ellipse samples, (N) two samples cultured in the bioreactor, (O) static culture of the ASCs encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogel, (P) pulsatile culture of the ASCs encapsulated in the gelatin-based hydrogel. Reprinted from Materials Science and Engineering: C, Vol 33, Issue 6, Huang Y, He K, Wang X, Rapid prototyping of a hybrid hierarchical polyurethane-cell/hydrogel construct for regenerative medicine, 3220-3229., Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

The control of the double-nozzle 3D printer parameters can provide a strong connection between the different polymer systems, such as the PLGA solution-gelatin hydrogel and PU solution/cell-laden gelatin-based hydrogel. The supportive synthetic polymers, such as PLGA and PU, and the ECM-like gelatin-based hydrogels can be adjusted to degrade at different time points during the organ construction and maturation stages. With proper selection of natural and synthetic polymer components, the 3D-printed bioartificial organs can avoid all the risks of vascular rupture, stress shrinkage, immune rejection, and otherwise reactions during the implantation stages[47,105,106]. These are all long-awaited breakthroughs in bioartificial organ manufacturing areas. This is also a long-term dream for other pertinent hot research fields, such as tissue engineering, biomaterials, drug screening, organ transplantation, and pathological analysis, with respect to the in vitro automatic manufacturing processes and in vivo failed/defective organ repair/replacement/restoration applications.

In 2013, Professor Wang developed a combined four-nozzle 3D bioprinter for complex organ manufacturing (Figure 9)[66]. This system can be used for a wide range of bioartificial organ manufacturing[107-109]. At the same time, the concept of vascularization and neutralization of the large scale-up 3D-printed tissues has been adapted rapidly all over the world.

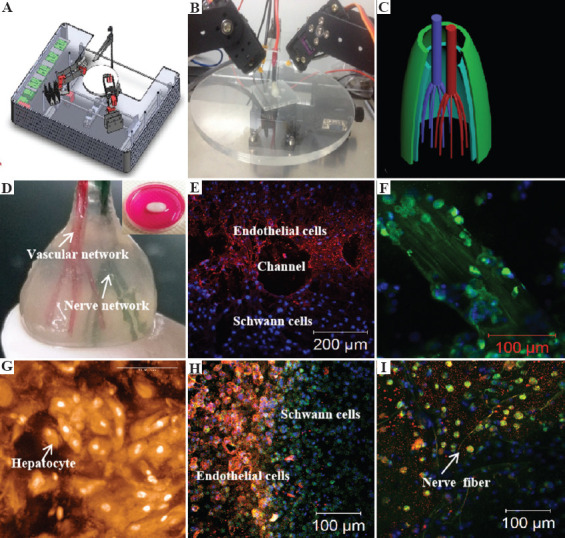

Figure 9.

A combined four-nozzle organ three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting technology created at Prof. Wang’s laboratory in Tsinghua University in 2013[66]: (A) Equipment of the combined four-nozzle organ 3D bioprinter, (B) working state of the combined four-nozzle organ 3D printer, (C) a computer-aided design (CAD) model representing a large scale-up vascularized and innervated hepatic tissue, (D) a semi-ellipse 3D construct containing a poly (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) overcoat, a hepatic tissue made from hepatocytes in a gelatin/chitosan hydrogel, a branched vascular network with a fully confluent endothelialized adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) on the inner surface of the gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel, and a hierarchical neural (or innervated) network made from Schwann cells in the gelatin/hyaluronate hydrogel, the maximal diameter of the semi-ellipse can be adjusted from 1 mm to 2 cm according to the CAD model, (E) a cross-section of (D) showing the endothelialized ASCs and Schwann cells around a branched channel, (F) a large bundle of nerve fibers formed in (D), (G) hepatocytes underneath the PLGA overcoat, (H) an interface between the endothelialized ASCs and Schwann cells in (D), (I) some thin nerve fibers. (from ref. [66] licensed under Creative Commons Attribution license).

Especially, with this integration of RP technology with cell-laden hydrogels, all the bottleneck problems, such as large scale-up tissue/organ manufacturing, in vivo biocompatibilities of implanted biomaterials, hierarchical vascular/nerve network construction with a fully endothelialized inner surface and anti-suture capability, long-term preservation of bioartificial tissues/organs, step-by-step ASCs differentiation in a 3D construct, in vitro metabolism model establishment, high-throughput drug screening, which have perplexed tissue engineers, biomaterial researchers, pharmaceutist, and other scientists for more than several decades, have been solved properly[97-99].

Over the last decade, extrusion-based 3D printing has been the most developed technologies for biomedical applications. Especially, multi-nozzle extrusion-based 3D printing technologies have many advantages for complex vascularized organ construction. It was found that the positions of the multiple polymeric “bioinks” (i.e., polymer solutions or hydrogels) can be changed sophistically according to the CAD models and nozzle states (e.g., diameter, position, and speed). For most of the polymeric hydrogels, the width of the printed filaments is mainly influenced by the fluid flow rate and nozzle moving speed[110-113]. Several polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles for the complex vascularized organ 3D printing with the incorporation of multiple cell types, stem cells/growth factors, and hierarchical vascular/neural networks with anti-suture and anti-stress properties.

From the above statements, it can be seen that the multi-functions of the liver need multiple nozzles to realize. The internal branched vascular networks need specific soft hardware to fulfill. Especially, blood supply system consists of hepatic artery and portal vein. How to distribute more than 3 kinds of high-density functional cells, including hepatocytes, hepatic stellates, and ECs, in a 3D construct and make them form tissues is the primary task. In 2005, Wang et al. in the organ manufacturing center of Tsinghua University first assembled ASCs and adult hepatocytes into a liver precursor[86-98]. In 2007, this group generated a branched vascular network and transformed ASCs into vascular ECs using their second-generation double-nozzle 3D bioprinter[50,99-104]. There are some other groups trying for liver 3D printing. For example, Chang et al. provided several sets of baseline parameters for direct printing of biomaterials according to the different humidity of the Pluronic F127 hydrogel system[114]. Miller et al. used sugar to print out a network that allows blood vessels to grow in the desired direction and melts off the stents after angioplasty[115]. It eventually grows into a conduit system in tissue. However, Birchall and De Coppi pointed out that what can be printed is undoubtedly feasible[116]. The key lies in the vascular system that can transport nutrients and remove waste. The transplantation of 3D-printed liver in patient has proven to be potentially effective in the connection between artificial vascular networks in liver with human vasculature. Before the 3D printing, details in dimensions of the donor livers, recipient socket, and diameters of connecting vessels should be precisely recorded with micro-scanning technology[10]. The outcome demonstrated that the artificial liver holds some value in clinical applications.

4.4. Pancreas

Anatomically, pancreas is a large elongated glandular organ, situated behind the stomach, that secretes insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin into the blood stream, and pancreatic juice (including digestive enzymes) into the duodenum[117]. In diabetes, the body produces insufficient insulin. Some people are genetically predisposed to diabetes. In certain patients, diabetes is caused by a fault in the insulin production. Diabetics have long been considered to be particularly prone to infection. A possible way to control juvenile-onset diabetes is through pancreas transplant. However, the number of donors is extremely limited.

The first 3D-printed vascularized pancreas was reported in 2010 in Professor Wang’s laboratory using her home-made double-nozzle 3D bioprinter[99]. In this study, ASCs in a gelatin-based hydrogel, that is, gelatin/alginate/fibrin, were assembled and induced to differentiate into two target cell types, that is, adipocytes and ECs, based on their positions within an orderly arranged 3D construct; pancreatic islets were then implanted at designated locations and constituted adipoinsular axis with adipocytes. Analysis of the factors involved in energy metabolic showed that the system captured more physiological and pathophysiological features of energy metabolic in vivo (Figure 10).

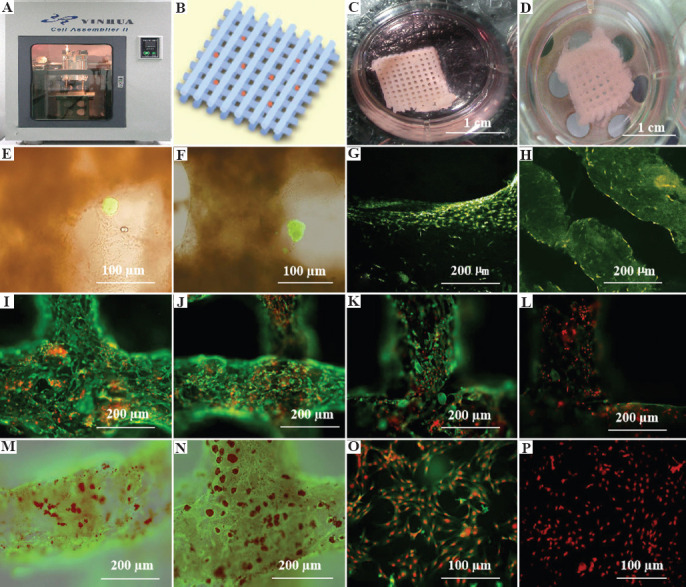

Figure 10.

3D bioprinting of adipose-derived stem cell (ASC)-laden gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel for organ manufacturing at Prof. Wang’s laboratory in Tsinghua University: (A) A pioneering double-nozzle 3D bioprinter made in this laboratory; (B) schematic description of the cell-laden gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel and pancreatic islets being printed into a grid construct using the 3D bioprinter; (C) a large scale-up 3D-printed grid construct containing ASC-laden gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel cultured in a plate; (D) a grid ASC-laden gelatin/alginate/fibrin construct after being cultured for 1 month; (E) a multicellular construct after 3 weeks culture, containing both ASCs encapsulated in the gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel before epidermal growth factor (EGF) engagement and relatively integrated pancreatic islets seeding in the predefined channels (immunostaining with anti-insulin in green); (F) some envelopes of the islets were broken after 1 month of culture; (G) immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD31+ cells (i.e., mature endothelial cells (ECs) from the ASC differentiation after 3 days of culture with EGF added in the culture medium) in green, having a fully confluent layer of ECs (i.e., endothelium) on the surface of the predefined channels; (H) a vertical image of the 3D construct showing the fully confluent endothelium (formed from ECs) and the predefined go-through channels; (I) immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD34+ cells (i.e., ECs) in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red; (J) immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD34+ ECs in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red after 3 days of culture without EGF added in the culture medium; (K) immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD31+ ECs in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red after 3 days of culture with EGF added in the culture medium; (L) a control of (K), immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD31+ ECs differentiated from the ASCs in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red after 3 days of culture without EGF added in the culture medium; (M) immunostaining of the 3D construct with mAbs for CD31+ cells in green and oil red O staining for adipocytes in red, showing both the heterogeneous tissues coming from the ASC differentiation after a cocktail growth factor engagement, that is, on the surface of the channels the endothelium coming from the ASCs differentiation after being treated with EGF for 3 days, deep inside the gelatin/alginate/fibrin hydrogel the adipose tissue coming from the ASC differentiation after being subsequently treated with insulin, dexamethasone, and isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) for another 3 days; (N) a control of (M) showing all the ASCs in the 3D construct differentiated into target adipose tissue after 3 days of treatment with insulin, dexamethasone, and IBMX, but no EGF; (O) immunostaining of two-dimensional (2D) cultured ASCs with mAbs for CD31+ ECs in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red after 3 days of culture with EGF added in the culture medium; (P) immunostaining of 2D cultured ASCs with mAbs for CD31+ ECs in green and pyridine (PI) for cell nuclei (nucleus) in red after 3 days of culture without EGF added in the culture medium. Reprinted from Biomaterials, Vol 31 Issue 14, Xu M, Wang X, Yan Y, et al., A Cell-Assembly Derived Physiological 3D Model of the Metabolic Syndrome, Based on Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells and a Gelatin/Alginate/Fibrinogen Matrix, 3868-3877., Copyright (2010), with permission from Elsevier.

Notably, after pre-cultured with high glucose, the glucose-induced insulin secretion peak of the assembled β-cells was delayed compared to normal controls, this delay could be revised by nateglinide. After long-term exposure to high glucose, adipocytes became obese and secreted more free fatty acids, leptin, and resistin, which actively involved in crosstalk with β-cell, decreased and delayed the insulin secretion peak value of β-cell. ECs form vascular wall-like structure, which serves as the endothelial barrier between the adipocytes and β-cells in vivo. Drugs known to have effects on metabolic syndrome showed accordant effect in the system.

This technique is automatic, versatile, rapid, and highly productive, it has significant potentials in high-content drug screening areas. Construction of such a multicellular system can help us to better understand pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome, develop new technologies for drug discovery and metabolomic profiling. Nevertheless, more than 10 years have passed since then. No further literature was reported in this area.

4.5. Vascularized bone

As the highest biological strength of tissue in the human body, bone is a flinty composition of hydroxyapatite and collagen with naturally balanced intensity and elasticity modulus. To maintain proper elasticity and avoid brittle fracture, the blood vessels in the bone tissue are abundant to maintain high level of metabolic activity and maintain the balance of bone resorption and bone reconstruction. The cortical bone has 10 – 30% porosity, meanwhile, the cancellous bone has 30 – 90% porosity[118]. The porous structure enables an active vascularized system to maintain the normal function of bone metabolism[119,120]. The distance between the intraosseous blood vessels and the nearest capillaries is within 100 μm in case of ischemic necrosis. Besides, the intravascular system provides advanced functions to maintain bone integrity, such as bone reconstruction, development, and fracture repair[121].

In traditional clinical application, typical bone graft models have been expected to have many characteristics, including osseointegration, bone conduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis[122]. Since 3D printing technology has been regarded as an excellent alternative to traditional bone graft manufacturing, vascularization in 3D bone printing has become the focus of researchers. Therefore, angiogenesis has become the essential process that must be considered in the design of 3D bone substitutes. Wang et al. described the process of vascularized osteogenesis using viral activated matrix and arginine glycine aspartate peptide phage nanofibers combined with 3D printing[120]. The scaffolds sowed with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell were used as bone defect fillers, which proved effectively, generate new blood vessels and increase osteogenesis. Temple et al. generated vascularized bone grafts using polycaprolactone (PCL) in 3D printing system[122]. The biodegradable PCL and the utilization of human ASCs enable the vascular network to be automatically modified when it was fused with recipient’s vessels. Furthermore, PCL was proved to be deferoxamine sustained releasing. Yan et al. believed that the PCL-based bone scaffolds are the ideal material for promoting vascularization and osteogenesis[123]. A biologically inspired nano coating technique was integrated into a 3D printing scaffold to achieve intelligent delivery of dual growth factors (BMP-2 and VEGF) and release them in a spatiotemporal coordinated order.[124] In another study, the authors combined the advances of dual 3D printing and regional immobilization strategy of bioactive factors for complex vascularized bone regeneration.[125,126] The combination of hard PLA scaffolds and soft gelatin vessels provides a promising platform for obtaining hierarchical bionic structures with multiphasic features and vascular networks[127-129].

5. Conclusions and perspectives

The procedure of vascularized organ 3D printing involves a series of material property changing processes at molecular, cell, tissue, and organ levels. A typical property of vascularized organ 3D printing is that it produces new functional objects which are totally different from the raw materials. It is an emerging new interdisciplinary field that needs a large scope of talent cooperation, such as biomaterials, biology, physics, chemistry, computers, mechanics, bioinformatics, and medicine. With the combination of innovative technologies, 3D printing has significant advantages in the construction of vascular networks in organs. For a long time, researchers have developed a variety of biocompatible 3D printing platforms with high sustainability and output. As an irreplaceable permanent vascular network generation approach, 3D printing technology has attracted many researchers because of its feasibility, diversity, and precise controllability. Current and future studies on 3D printing should target to overcome the technical drawbacks, such as the precise regulation of the vessel sizes, the accurate calculation of the branched angles and the exact building of the capillaries (with a diameter about 5 – 8 μm). It is necessary to improve the printing resolution in most of the 3D printing technologies with much more biocompatible polymers. Undoubtedly, 3D printing of vascularized organs will become a promising research trend in biomedical fields in view of the unlimited automaticity, producibility, and repeatability of the techniques.

Funding

The work was supported by grants from the Key Research and Development Project of Liaoning Province (No. 2018225082), the 2018 Scientist Partners of China Medical University (CMU) and Shenyang Branch of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (No. HZHB2018013), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 81571832).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

S.L.: Original draft preparation, edition, revision, and supplement; S.L. Supplement; X.W.: Revision and correction. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chatterjee P, Venkataramani AS, Vijayan A, et al. The Effect of State Policies on Organ Donation and Transplantation in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1323–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson MP, Hinde RL, Lavee J. Analysis of Official Deceased Organ Donation Data Casts Doubt on the Credibility of China's Organ Transplant Reform. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:79. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0406-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Liu C. Enabling Cutting Edge Technology for Regenerative Medicine. Vol. 1. Berlin: Spirnger; 2018. 3D Bioprinting of Adipose-derived Stem Cells for Organ Manufacturing; pp. 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei M, Wang X. Biodegradable Polymers and Stem Cells for Bioprinting. Molecules. 2016;21:539. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050539. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21050539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu F, Liu C, Chen Q, et al. Progress in Organ 3D Bioprinting. Int J Bioprinting. 2017;4:1–15. doi: 10.18063/IJB.v4i1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeong WY, Chua CK, Leong KF, et al. Rapid Prototyping in Tissue Engineering:Challenges and Potential. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:643–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.10.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozbolat IT, Hospodiuk M. Current Advances and Future Perspectives in Extrusion-Based Bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2016;76:321–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui H, Nowicki M, Fisher JP, et al. 3D Bioprinting for Organ Regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1601118. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601118. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201601118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith LG, Wu B, Cima MJ, et al. In Vitro Organogenesis of Liver Tissue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;831:382–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52212.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zein NN, Hanouneh IA, Bishop PD, et al. Three-Dimensional Print of a Liver for Preoperative Planning in Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1304–10. doi: 10.1002/lt.23729. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulsen SJ, Miller JS. Tissue Vascularization Through 3D Printing:Will Technology bring us Flow? Dev Dyn. 2015;244:629–40. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24254. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow SY, Yen-Chow YC, Woodbury DM. Studies on pH Regulatory Mechanisms in Cultured Astrocytes of DBA and C57 Mice. Epilepsia. 1992;33:775–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02181.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992tb02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kannan RY, Salacinski HJ, Sales K, et al. The Roles of Tissue Engineering and Vascularisation in the Development of Micro-Vascular Networks:A Review. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1857–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segal SS. Cell-to-cell Communication Coordinates Blood Flow Control. Hypertension. 1994;23:1113–20. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1113. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folkman J, Haudenschild C. Angiogenesis In Vitro. Nature. 1980;288:551–6. doi: 10.1038/288551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeno-Guanzon JG, Lee S, Berg JR, et al. Trends in Tissue Engineering for Blood Vessels. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:956345. doi: 10.1155/2012/956345. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/956345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risau W, Flamme I. Vasculogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, et al. Postnatal Vasculogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;100:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00522-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Risau W. Angiogenesis and Endothelial Cell Function. Arzneimittelforschung. 1994;44:416–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellstrom M, Phng LK, Gerhardt H. VEGF and Notch Signaling:The Yin and Yang of Angiogenic Sprouting. Cell Adh Migr. 2007;1:133–6. doi: 10.4161/cam.1.3.4978. https://doi.org/10.4161/cam.1.3.4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg JI, Shields DJ, Barillas SG, et al. A Role for VEGF as a Negative Regulator of Pericyte Function and Vessel Maturation. Nature. 2008;456:809–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07424. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flamme I, Frolich T, Risau W. Molecular Mechanisms of Vasculogenesis and Embryonic Angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 1997;173:206–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199711)173:2<206::AID-JCP22>3.0.CO;2-C. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199711)173:2206:AID-JCP223.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Breaching the Basement Membrane:Who, When and How? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:560–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senger DR, Davis GE. Angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005090. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005090. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a005090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senger DR, Perruzzi CA. Cell Migration Promoted by a Potent GRGDS-Containing Thrombin-Cleavage Fragment of Osteopontin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1314:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(96)00067-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4889(96)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkins GB, Jain MK, Hamik A. Endothelial Differentiation:Molecular Mechanisms of Specification and Heterogeneity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1476–84. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.228999. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.228999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swift MR, Weinstein BM. Arterial-Venous Specification during Development. Circ Res. 2009;104:576–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188805. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tkachenko E, Gutierrez E, Saikin SK, et al. The Nucleus of Endothelial Cell as a Sensor of Blood Flow Direction. Biol Open. 2013;2:1007–12. doi: 10.1242/bio.20134622. https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.20134622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aird WC. Phenotypic Heterogeneity of the Endothelium:II. Representative Vascular Beds. Circ Res. 2007;100:174–90. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui H, Miao S, Esworthy T, et al. 3D Bioprinting for Cardiovascular Regeneration and Pharmacology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;132:252–69. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badorff C, Brandes RP, Popp R, et al. Transdifferentiation of Blood-Derived Human Adult Endothelial Progenitor Cells into Functionally Active Cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 2003;107:1024–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051460.85800.bb. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000051460.ↄ0.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto K, Takahashi T, Asahara T, et al. Proliferation, Differentiation, and Tube Formation by Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Response to Shear Stress. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2081–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00232.2003. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh A, Singh A, Sen D. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cardiac Regeneration:A Detailed Progress Report of the Last 6 Years (2010-2015) Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:82. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0341-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0341-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levenberg S, Rouwkema J, Macdonald M, et al. Engineering Vascularized Skeletal Muscle Tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:879–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berthod F, Saintigny G, Chretien F, et al. Optimization of Thickness, Pore Size and Mechanical Properties of a Biomaterial Designed for Deep Burn Coverage. Clin Mater. 1994;15:259–65. doi: 10.1016/0267-6605(94)90055-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0267-6605(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tremblay PL, Hudon V, Berthod F, et al. Inosculation of Tissue-Engineered Capillaries with the Host's Vasculature in a Reconstructed Skin Transplanted on Mice. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1002–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00790.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Wray LS, Rnjak-Kovacina J, et al. Vascularization of Hollow Channel-Modified Porous Silk Scaffolds with Endothelial Cells for Tissue Regeneration. Biomaterials. 2015;56:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norotte C, Marga FS, Niklason LE, et al. Scaffold-Free Vascular Tissue Engineering Using Bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5910–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rider P, Zhang Y, Tse C, et al. Biocompatible Silk Fibroin Scaffold Prepared by Reactive Inkjet Printing. J Mater Sci. 2016;51:8625–30. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen K, Xu C, Chai W, et al. Freeform Inkjet Printing of Cellular Structures with Bifurcations. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1047–55. doi: 10.1002/bit.25501. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.25501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Ao Q, Tian X, et al. 3D Bioprinting Technologies for Hard Tissue and Organ Engineering. Materials. 2016;9:802. doi: 10.3390/ma9100802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9100802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu F, Chen Q, Liu C, et al. Natural Polymers for Organ 3D Bioprinting. Ploymers. 2018;10:1278. doi: 10.3390/polym10111278. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10111278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X. Handbook of Intelligent Scaffolds for Regenerative Medicine. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Pan Stanford Publishing; 2016. 3D Printing of Tissue/Organ Analogues for Regenerative Medicine; pp. 557–70. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu F, Wang X. Synthetic Polymers for Organ 3D Printing. Polymers. 2020;12:1765. doi: 10.3390/polym12081765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S, Tian X, Fan J, et al. Chitosans for Tissue Repair and Organ Three-Dimensional (3D) Bioprinting. Micromachines. 2019;10:765. doi: 10.3390/mi10110765. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi10110765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Yan Y, Zhang R. Gelatin-based Hydrogels for Controlled Cell Assembly. In: Ottenbrite RM, editor. Biomedical Applications of Hydrogels Handbook. New York:USA: Springer; 2010. pp. 269–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X. Bioartificial Organ Manufacturing Technologies. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:5–17. doi: 10.1177/0963689718809918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963689718809918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Tuomi J, Mäkitie AA, et al. The Integrations of Biomaterials and Rapid Prototyping Techniques for Intelligent Manufacturing of Complex Organs. In: Lazinica R, editor. Advances in Biomaterials Science and Applications in Biomedicine. London: InTech; 2013. pp. 437–63. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao X, Wang X. Preparation of An Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ADSC)/Fibrin-PLGA Construct Based on a Rapid Prototyping Technique. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2013;28:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao X, Liu L, Wang J, et al. In Vitro Vascularization of a Combined System Based on a 3D Bioprinting Technique. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014;10:833–42. doi: 10.1002/term.1863. https://doi.org/10.1002/term.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schrepfer I, Wang X. Progress in 3D Printing Technology in Health Care. In: Wang X, editor. Organ Manufacturing. Hauppauge. New York, USA: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2015. pp. 29–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leberfinger AN, Dinda S, Wu Y, et al. Bioprinting Functional Tissues. Acta Biomater. 2019;95:32–49. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibson I, Rosen D, Stucker B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies. 2nd ed. New York, USA: Springer; 2015. The Impact of Low-Cost AM Systems; pp. 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panwar A, Tan LP. Current Status of Bioinks for Micro-Extrusion-Based 3D Bioprinting. Molecules. 2016;21:685. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060685. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21060685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Midha S, Dalela M, Sybil D, et al. Advances in 3D Bioprinting of Bone:Progress and Challenges. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13:925–45. doi: 10.1002/term.2847. https://doi.org/10.1002/term.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gudapati H, Dey M, Ozbolat I. A Comprehensive Review on Droplet-Based Bioprinting:Past, Present and Future. Biomaterials. 2016;102:20–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hansen CJ, Saksena R, Kolesky DB, et al. High-Throughput Printing Via Microvascular Multinozzle Arrays. Adv Mater. 2013;25:96–102. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203321. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201203321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim JD, Choi JS, Kim BS, et al. Piezoelectric Inkjet Printing of Polymers:Stem Cell Patterning on Polymer Substrates. Polymer. 2010;51:2147–54. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skardal A, Zhang J, Prestwich GD. Bioprinting Vessel-Like Constructs Using Hyaluronan Hydrogels Crosslinked with Tetrahedral Polyethylene Glycol Tetracrylates. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gruene M, Pflaum M, Hess C, et al. Laser Printing of Three-Dimensional Multicellular Arrays for Studies of Cell-Cell and Cell-Environment Interactions. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2011;17:973–82. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0185. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten. TEC.2011.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gittard SD, Narayan RJ. Laser Direct Writing of Micro-and Nano-Scale Medical Devices. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7:343–56. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.14. https://doi.org/10.1586/erd.10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Erben A, Hörning M, Hartmann B, et al. Precision 3D-Printed Cell Scaffolds Mimicking Native Tissue Composition and Mechanics. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9:e2000918. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202000918. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202000918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu L, Wang X. Creation of a Vascular System for Complex Organ Manufacturing. Int J Bioprinting. 2015;1:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heinrich MA, Liu W, Jimenez A, et al. 3D Bioprinting:From Benches to Translational Applications. Small. 2019;15:e1805510. doi: 10.1002/smll.201805510. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201805510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Ao Q, Tian X, et al. Gelatin-Based Hydrogels for Organ 3D Bioprinting. Polymers. 2017;9:401. doi: 10.3390/polym9090401. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9090401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X. Advanced Polymers for Three-Dimensional (3D) Organ Bioprinting. Micromachines. 2019;10:814. doi: 10.3390/mi10120814. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi10120814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suri S, Han LH, Zhang W, et al. Solid Freeform Fabrication of Designer Scaffolds of Hyaluronic Acid for Nerve Tissue Engineering. Biomed Microdevices. 2011;13:983–93. doi: 10.1007/s10544-011-9568-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-011-9568-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin H, Zhang D, Alexander PG, et al. Application of Visible Light-Based Projection Stereolithography for Live Cell-scaffold Fabrication with Designed Architecture. Biomaterials. 2013;34:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laschke MW, Rücker M, Jensen G, et al. Incorporation of Growth Factor Containing Matrigel Promotes Vascularization of Porous PLGA Scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85:397–407. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.31503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]