Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the impact of sweet taste perception on dietary habits among students. Furthermore, the relationship between dietary habits and caries was studied.

Methodology:

cross-sectional study was conducted among 200 college-going students aged 18–23 years from the Asan Memorial Institutions. The frequency of consumption of certain food items was analyzed from a Beverage and Snack Questionnaire, and the dietary record was obtained for 3 days. The sweet taste perception level was determined as sweet taste threshold and sweet taste preference. According to the sweet taste perception level, children were grouped into low, medium, and high. Decayed, missing, and filled teeth index was used for recording the incidence of caries.

Results:

High sweet threshold and preference groups showed an increased incidence of dental caries compared to the low and medium threshold and preference groups.

Conclusion:

Sweet taste perception level influenced the dietary habits and intake of sweets. The relationship between the dietary habits and the caries was found to be significant.

KEYWORDS: Dental caries, diet, taste sensitivity, threshold

INTRODUCTION

Healthy diet plays an important role in growth, development, and protection against nutritional diseases.[1] Physiological requirements, psychosocial pressures, and other factors alter dietary habits from children to adolescents.[2] A healthy diet should constitute a greater proportion of whole grains, cereals, pulses, fruits, and vegetables, which has reduced now in our daily life and has been replaced by refined sugar, refined grains, and salts in recent years that leads to several health problems.[3] Dietary habits are dominated by cognitive factor (taste perception) that permits the individual to allot subjective reward to specific type of foods.[4] The sensory information of taste perception on the tongue is carried through the nervous system.[5] Sugar consumption is done in the form of sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, agave nectar, caramel, and brown sugar.[6] Sweetness is detected by sweet taste receptors (TASR2 and TASR3) located on the taste bud. Stimulation of these receptors causes the opening of sodium or potassium channel in the cells where the development of receptor potential occurs followed by activation of G protein.[7] Sweet taste receptors are also expressed in the digestive system, pancreas where they do not vitalize sweet sensation but they play an important role in glucose homeostasis, insulin secretion, and adipogenesis.[8,9] Overconsumption of sugar affects the oral health at an early stage of teeth development.[10,11,12] The aim of this study was to assess the perception of sweets in relation to dietary habits and influence of dietary habits on dental caries.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional study. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board. Study comprised 200 students aged 18–23 years from the Asan Memorial Institution. Students, who are medically compromised, undergoing orthodontic treatment were excluded from the study. Data collection was conducted using pro forma, which consists of demographic profile, decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFS) index, sweet taste perception level measurements, food intake records, and beverage and snack intake questionnaire. Students were examined under natural light in classroom setting using disposable dental examination kits according to WHO criteria.

Criteria 1

Three-day food records were collected. Students were asked to report the food and drink intakes in terms of time and quantity from any 2 weekdays and from 1 weekend as a breakfast, lunch, and dinner from which we calculated the number of main meal intake. Any food intake within 30 min was considered as one intake.[13]

Criteria 2

Sweet intake frequency was calculated using beverage and snack intake questionnaire which was adopted from Sarah Kehoe's dietary pattern in the South Indian population. This questionnaire consists of nine food and drinks items which include tea/coffee, milk/milk-based drinks, fruit drinks, fruit-based drinks, sweetened drinks, cakes, biscuits, confectionary, and sugary foods, totally which had five drinks and four snack items.[14] Students were asked to select options ranging from never (score-0) to more than 3 times (score-4) for each items per day. To calculate beverage intake score and snack intake score, items were summed up accordingly.[15]

Criteria 3

The sweet taste perception level of the participants was assessed by using a modified version of Furquim et al.,[16] method which was originally described by both Zengo AN et al.,[17]& Nilsson B et al.[18] To assess sweet taste perception, two variables such as sweet taste threshold and sweet taste preference were used. Sweet taste threshold is the minimum concentration at which taste sensitivity to sweets can be perceived by the participant. And sweet taste preference is the preferred solution chosen by the participant that matches the level of sugar that he/she might like in a drink.

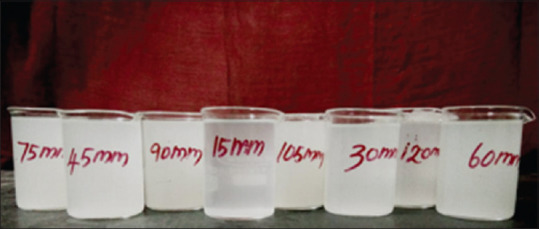

The participants were asked to taste all the eight different glucose solutions with the varying concentration ranging from 15 mM/L to 120 mM/L with a gradation of 5Mm/L in each beaker [Figure 1].[19] The participants were asked to rinse their mouth every time with filtered water before tasting each solution with different glucose concentrations. The students were asked to taste the solutions in increasing concentration and identify their sweet taste threshold level and sweet taste preference and mark the solution number, respectively, on the sheet. They were given 10 ml of sugar solution, to stimulate the taste buds for at least 5 s and spit it out after which the students were grouped according to sweet taste threshold and sweet taste preference of their choice. The students were grouped as “LOW” when they chose a solution between 15 and 30 mM/L, “MEDIUM” when they chose solution between 45 and 75Mm/L, and “HIGH” if the solution's concentration ranges between 90 and 120 mM/L.

Figure 1.

This picture shows eight different solutions with the varying glucose concentrations ranging between 15mM/L and 120mM/L

Criteria 4

Dental caries was assessed using DMFS index. The DMFS index is defined as the sum of the decayed, missed and filled tooth surfaces. No radiographs were taken.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 21 Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparison of mean DMFS, sweet intake, and main meal intake among low, medium, and high sweet taste threshold and sweet taste preference groups was done using one-way analysis of variance analysis. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sweet taste threshold

On comparison of all the variables, sugar threshold showed positive correlation between DMFS and sweet intake and negative correlation between DMFS and main meal. Results of sugar threshold showed positive correlation between DMFS and sweet intake and negative correlation between DMFS and main meal. Statistically, a significant difference was found among low, medium, and high threshold groups in DMFS and sweet intake (P ≤ 0.001) and was not significant in main meal intake (P ≤ 0.71) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean DMFT, sweet intake and main meal among the various sweet threshold levels

| Variable | Low threshold | Medium threshold | High threshold | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFS | 1.71±2.53 | 3.64±3.11 | 11.00±0.0 | 0.001* |

| Sweet intake | 5.28±3.02 | 5.24±2.58 | 14.00±0.0 | 0.001* |

| Main meal | 2.85±0.51 | 2.82±0.62 | 2.00±0.0 | 0.71 |

DMFS: Decayed, missed, and filled surface

Sweet taste preference

On comparison of all the variables, sweet taste perception showed positive correlation between DMFS and main meal and negative correlation between DMFS and sweet intake. Results of sweet taste perception showed positive correlation between DMFS and main meal and negative correlation between DMFS and sweet intake. There was a statistically significant difference between low, medium, and high preference groups in sweet intake (P ≤ 0. 002) and was not significant in DMFS and main meal intake (P ≤ 0.51 and P ≤ 0.30) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean DMFS, sweet intake and main meal among the various sweet preference levels

| Variable | Low preference | Medium preference | High preference | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFS | 1.93±3.29 | 2.03±2.59 | 2.50±3.09 | 0.51 |

| Sweet intake | 3.50±2.65 | 4.84±2.32 | 5.91±3.15 | 0.002* |

| Main meal | 2.75±0.68 | 2.81±0.46 | 2.90±0.48 | 0.30 |

DMFS: Decayed, missed, and filled surface

DISCUSSION

Our study was to elevate the effect of sweet taste perception on dietary habits, which leads to dental caries. According to our study, the sweet taste threshold and preference were directly related to the number of sweet intake events and indirectly related to the number of main meal intake. These results were supported by Ashi et al.,[15] and Mithra et al.,[20] who stated that sweet perception can affect the dietary habits, which influences the selection of food items leading to more sugar and snack consumption.

In this study, high sweet threshold and preference group showed higher intake of sweets and a smaller number of main meal intake. High thresholds over a period of time can alter taste which leads to consumption of more sweets to acquire their preference taste. Simultaneously, we also found that higher sweet taste group showed higher incidence of caries. These findings were similar to studies done by Peres et al., 2010[21] in which higher sugar consumer groups had a higher incidence of dental caries and Bernab et al. 2014[22] found that drinking sweetened beverages on a daily basis is related to greater risk of caries. And Mathur et al., 2015[23] found that consumption of sweet, sugary foods, and increased snacking in between meals is one of the most important factors for caries.

In contrast to the findings of our study, Nilsson and Holm 1983[17] found that there was no relation between sugar intake and dental caries, and Ashi et al., 2017[15] found that there was no significant correlation between sweet intake and dental caries and also Van Loveren 2019[24] found that sugar intake and dental caries showed no relation or relatively low.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the study, there is a direct relationship between sweet threshold and dental caries. The person who is addicted to sweets is found to have more density of dopamine receptors which stimulates the reward center which in turn makes them crave for sweets. To spread awareness of sweet addiction and reduce their sweet intake, health education should be given to the participants to improve the dietary habits, oral, and general health.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, Hu FB, Hunter D, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1577–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ. Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:279–93. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popkin BM. An overview on the nutrition transition and its health implications: The Bellagio meeting. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:93–103. doi: 10.1079/phn2001280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslin PA, Spector AC. Mammalian taste perception. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang LD, Cuellar-Partida G, Ong JS, Breslin PA, Reed DR, MacGregor S, et al. Sweet taste perception is associated with body mass index at the phenotypic and genotypic level. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2016;19:465–71. doi: 10.1017/thg.2016.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati S, Misra A. Sugar intake, obesity, and diabetes in India. Nutrients. 2014;6:5955–74. doi: 10.3390/nu6125955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolls ET. Taste, olfactory, and food reward value processing in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2015;127-128:64–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laffitte A, Neiers F, Briand L. Functional roles of the sweet taste receptor in oral and extraoral tissues. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:379–85. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masubuchi Y, Nakagawa Y, Ma J, Sasaki T, Kitamura T, Yamamoto Y, et al. A novel regulatory function of sweet taste-sensing receptor in adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernabé E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Lundqvist A, Suominen AL. The shape of the dose-response relationship between sugars and caries in adults. J Dent Res. 2016;95:167–72. doi: 10.1177/0022034515616572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheiham A, James WP. A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: Implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:2176–84. doi: 10.1017/S136898001400113X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moynihan P. Sugars and dental caries: Evidence for setting a recommended threshold for intake. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:149–56. doi: 10.3945/an.115.009365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall TA, Broffitt B, Eichenberger-Gilmore J, Warren JJ, Cunningham MA, Levy SM. The roles of meal, snack, and daily total food and beverage exposures on caries experience in young children. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:166–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kehoe SH, Krishnaveni GV, Veena SR, Guntupalli AM, Margetts BM, Fall CH, et al. Diet patterns are associated with demographic factors and nutritional status in South Indian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:145–58. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashi H, Campus G, Bertéus Forslund H, Hafiz W, Ahmed N, Lingström P. The influence of sweet taste perception on dietary intake in relation to dental caries and BMI in Saudi Arabian schoolchildren. Int J Dent. 2017;2017:4262053. doi: 10.1155/2017/4262053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furquim TR, Poli-Frederico RC, Maciel SM, Gonini-Júnior A, Walter LR. Sensitivity to bitter and sweet taste perception in schoolchildren and their relation to dental caries. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zengo AN, Mandel ID. Sucrose tasting and dental caries in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1972;17:605–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(72)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson B, Holm AK. Taste thresholds, taste preferences, and dental caries in 15-year-olds. J Dent Res. 1983;62:1069–72. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayasinghe SN, Kruger R, Walsh DC, Cao G, Rivers S, Richter M, et al. Is sweet taste perception associated with sweet food liking and intake? Nutrients. 2017;9:750. doi: 10.3390/nu9070750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Thapar R, Kumar N, Hegde S, Mangaldas Kamat A, et al. Snacking behaviour and its determinants among college-going students in Coastal South India. J Nutr Metab. 2018;2018:6785741. doi: 10.1155/2018/6785741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peres MA, Sheiham A, Liu P, Demarco FF, Silva AE, Assunção MC, et al. Sugar consumption and changes in dental caries from childhood to adolescence. J Dent Res. 2016;95:388–94. doi: 10.1177/0022034515625907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernabé E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: A 4-year prospective study. J Dent. 2014;42:952–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathur A, Vikram P, Aggarwal V, Mathur A. Inclination of sugar rich diet and its effect on oral health among school children. Int J Healthc Sci. 2015;3:178–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Loveren C. Sugar restriction for caries prevention: Amount and frequency?Which is more important. Caries Res. 2019;53:168–75. doi: 10.1159/000489571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]