ABSTRACT

Hesperidin, a flavonoid enriched in citrus peel, can be enzymatically glycosylated using CGTase with significantly improved water solubility. However, the reaction catalyzed by wild-type CGTase is rather inefficient, reflected in the poor production rate and yield. By focusing on the aglycon attacking step, seven residues were selected for mutagenesis in order to improve the transglycosylation efficiency. Due to the lack of high-throughput screening technology regarding to the studied reaction, we developed a size/polarity guided triple-code strategy in order to reduce the library size. The selected residues were replaced by three rationally chosen amino acids with either changed size or polarity, leading to an extremely condensed library with only 32 mutants to be screened. Twenty-five percent of the constructed mutants were proved to be positive, suggesting the high quality of the constructed library. Specific transglycosylation activity of the best mutant Y217F was assayed to be 935.7 U/g, and its kcat/KmA is 6.43 times greater than that of the wild type. Homology modeling and docking computation suggest the source of notably enhanced catalytic efficiency is resulted from the combination of ligand transfer and binding effect.

IMPORTANCE Size/polarity guided triple-code strategy, a novel semirational mutagenesis strategy, was developed in this study and employed to engineer the aglycon attacking site of CGTase. Screening pressure was set as improved hesperidin glucoside synthesis ability, and eight positive mutants were obtained by screening only 32 mutants. The high quality of the designed library confirms the effectiveness of the developed strategy is potentially valuable to future mutagenesis studies. Mechanisms of positive effect were explained. The best mutant exhibits 6.43 times enhanced kcat/KmA value and confirmed to be a superior whole-cell catalyst with potential application value in synthesizing hesperidin glucosides.

KEYWORDS: mutagenesis strategy, cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase, transglycosylation, hesperidin

INTRODUCTION

Cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase (CGTase, EC 2.4.1.19) belongs to the GH13 family which is the largest glycoside hydrolase family, including 44 subfamilies and more than 130,000 identified enzymes according to the May 2022 update of the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database (CAZY, http://www.cazy.org/GH13.html) (1). Enzymes in GH13 family are consistent with (β/α)8-barrel fold that active in processing α-glucosidic linkages following retaining mechanisms (2). In the case of CGTase, the enzyme is specifically active on α(1→4)-linked glucosidic bond following a double displacement retaining mechanism that involves the formation of a β(1→4)-linked enzyme-glycosyl intermediate, followed by the attack of a glycosyl acceptor (3, 4). The uniqueness of CGTase is its intramolecular transglycosylation ability in utilizing the hydroxyl group at the nonreducing end of the intermediate to form cyclic maltooligomers, known as cyclodextrins (5). Besides, CGTase catalyzes intermolecular transglycosylations through coupling and disproportionation using a variety of carbohydrates (6–9) as well as many other chemicals species such as ascorbic acid (10), hesperidin (11), rutin (12), sophoricoside (13), and ginsenoside (14) as acceptors, forming glucosides with random numbers of glucose units attached. The synthesized glucosides exhibit enhanced water solubility and bioavailability with promising application values (15).

On the other hand, most CGTase catalyzed transglycosylation processes are not efficient enough for industrial production of glucosides. For example, the glycosylation of ascorbic acid catalyzed by a commercial CGTase from Thermoanaerobacter sp. gives only 30% yield (16). Insufficient conversions were also observed in CGTase-catalyzed glycosylation of rutin (17) and hesperidin (18). Enzyme engineering has been proved to be an effective approach to alter the CGTase’s catalytic properties to reach the target product (19–21). Early studies of CGTase engineering have been focusing on the traditional application of CGTase in producing either α-, β-, or γ-cyclodextrins, and reported improved product specificity can be achieved through the modification of the enzyme-glycosyl binding site (22–27). Recently, engineering of CGTase to improve its intermolecular transglycosylation ability in regard of synthesizing glucosides, such as alkyl glucosides, ascorbic acid 2-glucoside, sophoricoside glucoside, has attracted wide attentions (28–31).

Hesperidin glucoside is a derivative of hesperidin which is a natural bioflavonoid enriched in citrus peel (32–35). Compared with hesperidin, its glucosylation form presents significantly improved water solubility (1,970 g/L compared with 0.09 mg/L under room temperature) and bioavailability. Hesperidin glucoside inherits the antihyherlipidaemic, antioxidation, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, and antimicrobial functions of hesperidin through in vivo hydrolysis (36), and it has now been applied in skin care products to protect tissues from cold shock and promote skin rejuvenation (37, 38). The wild-type CGTase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. A2-5a shows hesperidin glycosylation ability but with poor synthetic rate and yield (18, 39). By focusing on the aglycon attacking step, we engineered the residues that potentially interact with the attacking aglycon. One bottleneck in this case of study is the difficulty to set up high-throughput screening as hesperidin and its glucosides share the same absorption spectra, so a finely designed library becomes distinctively important to reduce the screening effort while maintaining the library quality.

Sophisticated mutagenesis strategies have been developed lately to achieve such goal. Sun et al. developed the triple-code saturation mutagenesis strategy which employed reduced amino acid alphabet in engineering the catalytic pocket of limonene epoxide hydrolase (LEH). The strategy generally involves three steps: (i) locate the key residues in the catalytic pocket; (ii) analyze the common feature of the key residues; (iii) choose three amino acids sharing the same feature as the reduced amino acid alphabet (40, 41). On the other hand, such strategy is difficult to be applied when the common feature of the key residues cannot be identified. Other studies used homologous alignment to build different codon degeneracies at different selected sites (42, 43).

In this study, we focused on the size and polarity of the selected residues, and developed a size/polarity guided triple-code strategy to adapt our case where the mutual features of the selected residues are unclear. The size/polarity guided triple-code strategy involves three steps: (i) locate the key residues in the catalytic pocket; (ii) group the residues either by the polarity or size of the side chain; (iii) choose three amino acids either sharing similar polarity or size as the reduced amino acid alphabet. Eight positive mutants were obtained by screening only 32 transformants after single-site mutation. kcat/KmA value of the best mutant Y217F is enhanced 6.43 times compared with the wild type.

RESULTS

Selection of mutation sites and library design.

FASTA sequences alignment of the studied CGTase with Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase results in 73.6% sequence similarity (Fig. S1), and a homology model was constructed from the resolved structure (PDB: 1CDG) (44). Crystal structure of Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase in complex with a maltononaose inhibitor (PDB: 2DIJ) was used to determine the aglycon attacking site (45). Residues within 4 Å radius of the two glucose units at the +1 and +2 subsites were selected as the “aglycon attacking site” and aligned with the corresponding residues in the studied CGTase. RMSD of their alpha-carbons was calculated to be 0.081 Å (Fig. S2). The small difference suggests the high similarity of the two aglycon attacking sites, and confirms the reliability of the defined aglycon attacking site from the resolved crystal structure. Besides the catalytic triad (D251, E279, and D350), the selected residues, including F205, Y217, A252, K254, H255, and F281 plus G283 located next to the +2 subunit were subjected to mutagenesis as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Aglycon attacking site defined as the residues within 4 Å radius of the two glucose units (azure) in the +1 and +2 subsites. Other than the catalytic triad (yellow), the residues in the head pocket plus G283 (gray) were subjected to mutagenesis.

Libraries were then designed by the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy from two aspects: (i) maintain the side chain’s structural properties and change the hydrophobicity, from which three libraries were designed as L1, L2, and L3 with bulk ring, long, or short side chains, respectively; (ii) maintain the side chain’s hydrophobicity and change the structural properties, from which two libraries were designed as L4 and L5 with hydrophilic and hydrophobic side chains, respectively. The mutagenesis strategy was summarized as Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Libraries design based on the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy

| Strategy 1: maintain the size and change the polarity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Libraries | Wild type | Triple code | ||

| L1 (bulk ring) | F205, Y217, H255, F281 | Y | H | F |

| L2 (long chain) | K254 | R | L | I |

| L3 (short chain) | A252, G283 | S | T | G |

| Strategy 2: maintain the polarity and change the size | ||||

| L4 (hydrophilic) | Y217, K254, H255 | S | H | R |

| L5 (hydrophobic) | F205, A252, F281, G283 | F | V | L |

Generation of mutagenesis libraries and first-round screening.

According to the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy shown in Table 1, five mutagenesis libraries were generated using pET-22b(+)/CGTase-6×His as the templet and the corresponding primers. The resulting plasmids were confirmed to carry the CGTase expressing gene by gel electrophoresis (Fig. S3), and then inserted into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Overall 32 transformants were constructed and the desired mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The first-round screening was performed through whole-cell catalysis. Whole-cell transglycosylation activities (WCTAs) were assayed with parallels according to equation 1 in order to determine the specific transglycosylation activity per unit of cell density. Fig. 2 shows the relative WCTAs of the 32 mutants compared with the wild type. Mutations at three specific residues, F205, Y217, and G283 were found to be effective, and eight mutants, including F205H, F205V, F205L, Y217S, Y217F, G283T, G283V, and G283L were subjected to the second-round of screening.

| (1) |

FIG 2.

Thirty-two mutants were constructed based on the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy and cultured in shake flasks. First-round screening determines positive mutants (red arrow) based on the relative WCTAs compared with the wild type. Enzyme activities were assayed at pH 10.0, 40°C, with 50 mL shake flask cultured cells.

Purification of CGTases and second-round screening.

In order to determine the specific transglycosylation activity (STA) of each mutant, the eight positive mutants together with the wild type were purified with nickel column. The purified enzymes were characterized by SDS-PAGE to confirm the protein size and purity (Fig. S4). After determining the protein content in each of the purified enzymes, STAs defined as the substrate converted in unit of time and protein content were assayed with parallels according to equation 2. STAs of mutants and wild type are shown in Fig. 3. The second round of screening confirms the eight mutants to be positive. STA of the best mutant Y217F was assayed to be 935.7 U/g, which is 6.96 times that of the wild type.

| (2) |

FIG 3.

Eight mutants obtained by the first-round screening together with the wild type were purified and assayed with their STA. Enzyme activities were assayed at pH 10.0, 40°C, with 20 μL purified enzyme.

Characterizations of wild-type CGTase and Y217F mutant.

Based on equation 3, disproportion kinetics of wild type and Y217F were further investigated (Fig. S5), and kinetics parameters are listed in Table 2. Compared with the wild type, kcat value of Y217F is 10.41-fold higher, where KmA (hesperidin) and KmB (maltodextrin) values after mutation are increased by 67% and 129%, respectively. When maltodextrin is in abundance, approximation of ping-pong mechanism leads to Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and kcat/KmA of Y217F is 6.43-fold higher than that of the wild type.

| (3) |

TABLE 2.

Disproportionation kinetic parameters of wild-type CGTase and Y217F

| Enzyme |

Kcat (min−1) |

KmA (hesperidin) (g L−1) |

KmB (maltodextrin) (g L−1) |

Kcat/KmA (L g−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0.47 | 6.52 | 0.92 | 0.07 |

| Y217F | 4.85 | 10.86 | 2.11 | 0.45 |

Temperature and pH profiles of the wild type and Y217F were further compared with the target reaction (Fig. S6). Characterized properties of the wild type are consistent with the previous study reported by Kometani et al. (39), and we found that mutant share similar features with the wild type. Due to the poor solubility of hesperidin at acid to neutral pH, only the alkaline region (pH ≥10.0) was characterized. Transglycosylation activity gradually decreases with increasing pH at pH above 10.0. Both enzymes were found most active at 60°C when being assayed at 15 min under 20°C to 70°C. But the enzymes are relatively stable at temperature below 50°C.

Hesperidin glucoside production by whole-cell catalysis.

Industrial application value of the constructed mutant was further assessed by whole-cell catalysis. Batch fermentation was applied to prepare whole-cell catalysts with OD600 ~20, and hesperidin glycosylation processes catalyzed by the wild-type CGTase and the best mutant Y217F were compared. Fig. 4 shows the substrate and products change during whole-cell catalysis analyzed by HPLC. Fast utilization of substrate by the Y217F mutant was observed in the first 2-h catalysis and almost reached equilibrium after 4 h, where catalysis by the wild-type showed a linear decrease of substrate suggesting it is remained at the initial catalytic state. Products, including α-glucosyl hesperidin and α-oligoglucosyl hesperidin were observed in both catalysis, and the mutant exhibited significantly higher production rate. Substrate utilization rate in 4-h catalysis by Y217F whole-cell catalyst reached 3.65 g/L per h, which is 2.35 times higher than that of the wild type.

FIG 4.

Whole cell catalyzed hesperidin glycosylation by Y217F (red triangle,  ) and wild-type (blue circle,

) and wild-type (blue circle,  ). GH: hesperidin glucoside, G2H: hesperidin maltoside, G3H: hesperidin maltotrioside.

). GH: hesperidin glucoside, G2H: hesperidin maltoside, G3H: hesperidin maltotrioside.

DISCUSSION

Selection of mutation sites at the aglycon attacking site.

Our previous kinetics study on a GH13 enzyme revealed the catalytic efficiency is dependent on the selective transglycosylation scheme, where the formed enzyme-glucosyl intermediate is competitively reacted by the target aglycon, water, and side products with different efficiencies (46). In the case of CGTase, there are four reaction routes for the enzyme-glycosyl intermediate to go through selective transglycosylations: (i) react with the aglycon to form the target glycosides; (ii) react with water to form a glucan; (iii) react with another glucose or glucan to form polysaccharides; (iv) react with its own nonreducing end to form cyclodextrin (47). Among the possible routes, only the first one leads to substrate conversion. Side reactions not only competitively consume the formed enzyme-glucosyl intermediate, but also yield cyclodextrins and maltooligomers known to inhibit CGTase (48, 49). In this case, strengthening the transglycosylation preference to the target aglycon than other acceptors is critical in improving the glycosylation efficiency.

As followed by the double displacement mechanism, transglycosylation preference is dependent on the second displacement step where an aglycon molecule attacks the enzyme-glucosyl intermediate, and, therefore, residues near the aglycon attacking site are potentially important to control the transglycosylation efficiency. Several CGTase crystal structures have been resolved favoring to determine the aglycon attacking site. In the structure of CGTase in complex with a maltononaose inhibitor, two parts of glucosyl units (seven from the nonreducing end and two from the reducing end) were separated by the catalytic triad and the surrounding residues of the corresponding glucosyl unit were defined as subsites −7 to +2 (45). Based on another structure of CGTase in complex with the transglycosylation product, γ-cyclodextrin, aglycon was found to be bound at the +1 and +2 subsites and attacks from the reducing end (50).

Previous studies have reported the intermolecular transglycosylation behavior of CGTase can be impacted by engineering the +1 and +2 subsites. For example, L277 mutants of Bacillus stearothermophilus NO2 CGTase (51), F183, F195, and A230 mutants of Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase (52), F184, A231, and F260 mutants of Bacillus subtilis strain DB104A (53), their transglycosylation preferences were significantly altered. By enhancing the affinity between enzyme and the target aglycon, CGTases with engineered +1, +2 subsites can potentially exhibit improved ability in synthesizing glycosides. Han et al. engineered three residues in the +2 subsite of Paenibacillus macerans CGTase, and obtained a mutant with 60% improved ascorbic-2-glucoside (AA-2G) synthetic rate (54). Tao et al. mutated 9 residues on the +1 and +2 subsites of Bacillus stearothermophilus NO2 CGTase based on a consensus strategy, and obtained a mutant with 2.69-fold increased kcat/Km in synthesizing AA-2G (30). In this case, we attempted to define residues at the +1 and +2 subsites for mutagenesis.

By aligning structures of Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase and our studied enzyme, we confirmed the similarity of the +1 and +2 subsites of the two enzymes (Cα RMSD = 0.081 Å), and F205, Y217, A252, K254, H255, and F281 were defined as the aglycon attacking site. All selected residues have their side chains pointing to the pocket, confirming their mutagenesis will impact on the enzyme-aglycon interactions. G283, although not located in the selected area, is subjected to mutagenesis, as it is located right next to the +2 subsite, and may interact with the aglycon with extended side chain.

Mutagenesis with the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy.

With the defined aglycon attacking site, a suitable mutation strategy is critically important in terms of engineering efficiency. One can employ site-specific saturated mutagenesis that involves the exchange of a selected residue by all of the other 19 canonical amino acids. Such strategy gives a thorough coverage of the possible mutants but may involve vast screening efforts. If followed by such strategy, 140 transformants need to be screened when employing single-site saturated mutagenesis, 560 transfromants when employing multiple-site saturated mutagenesis in an iterative order (55), and 1.28 × 109 transformants when employing multiple-site saturated mutagenesis in a random order in our case with seven selected residues.

Other strategies involve the reduced amino acid alphabets that helps to minimize to the mutagenesis library. The proposed single-code and triple-code strategy have been successfully employed in engineering limonene epoxide hydrolase with enhanced stereoselectivity (41, 56). In such strategy, the choice of the reduced amino acid alphabets is significantly important to maintain the target mutants in the library, and previous experiences suggest successful engineering is favored by preserving the natural properties of the selected residues (57).

On the other hand, diverse features were observed in the residues constituting the defined aglycon attacking site, and using a single amino acid alphabet with sufficient property features can easily lead to large library size. Size/polarity guided triple-code strategy was developed considering the important features of side chain size and polarity in influence of enzyme-ligand interaction, ligand transportation (58) and binding (59) for example, that different amino acid alphabets were applied at each residue in change of either side chain size or polarity. By performing single-site mutagenesis, an extremely condensed library was constructed containing only 32 mutants, and eight were screened to be positive. The small size of the library and the high ratio of positive mutants confirmed the effectiveness of the size/polarity guided triple-code strategy to be applied in our case.

The positive mutant Y217F with the highest transglycosylation activity was further prepared through batch fermentation. Under 20 g/L initial substrate loading, 3.65 g/L per h hesperidin conversion rate can be reached within 4-h catalysis by the Y217F mutant as whole-cell catalyst. Final substrate conversion reached 75%, and further hesperidin conversion was impeded, potentially due to the reversible nature of transglycosylation catalyzed by CGTase (60). By comparing the catalytic process of Y217F and wild type, the superiority of Y217F as whole-cell catalyst was confirmed with potential application value.

Synergetic mutation effect from ligand transportation and binding.

To understand the enhanced tranglycosylation activity, we first analyzed the mutagenesis from a structural aspect. The catalytic pocket was identified with Fpocket based on the constructed homology model (61). As shown in Fig. 5, among the three identified “hot spots” (F205, Y217, and G283), F205 and Y217 are located at the entrance of the pocket. The side chains of the two residues point to each other forming the pocket edge. A bump at the pocket entrance formed by Y217 was observed. Five positive mutants at these two locations all involve side chain shrinkage. Taking the large molecular size of hesperidin into consideration, the positive effect can be a result from expansion of the substrate tunnel, leading to easier access of hesperidin to the catalytic pocket.

FIG 5.

Relative locations of F205, Y217, and G283 to the catalytic pocket.

On the other hand, access to the catalytic pocket should not be sterically hindered by G283, as the side chain of G283 is minimized and it locates far from the catalytic pocket (Fig. 5). It was speculated the positive effect is resulted from the extended side chain that potentially interacts with hesperidin and stabilizes its binding. To prove this hypothesis, the mutagenesis of G283 together with the other two residues were further analyzed by molecular docking. The covalent intermediate (PDB: 1CXL) that also resolved from Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase was employed in this part of study (62).

By referring to the covalent intermediate structure, relative locations of the docked hesperidin and the enzyme-glycosyl intermediate can be determined, and distance of the bond-forming atoms was restrained to ensure the docked hesperidin is in an effective attacking pose. Fig. 6 shows the docked structure, in which the bond forming atoms are 2.8 Å away. This distance is within the van der Waals contact distance of the two bond-forming atoms (rC + rO = 3.35 Å), suggesting the docked hesperidin can potentially attack the enzyme-glycosyl intermediate and complete transglycosylation (63).

FIG 6.

Hesperidin docked with the enzyme-glycosyl covalent complex. The distance between bond forming atoms (d = 2.8 Å) is within the van der Waals contact distance.

Hesperidin interactions with the three “hot spots” in the wild-type are shown in Fig. 7a. F205 lays under the flavonoid skeleton of hesperidin forming stacking interactions. Hydrogen bond between Y217 and Glu-OH3 of hesperidin was observed. G283 locates at the side of flavonoid skeleton but too distant to form significant interactions. Ligand interactions of the three F205 mutants are shown in Fig. 7b. F205H forms similar stacking interactions as the wild type. F205L and F205V lose such interaction but their side chains branching toward the flavonoid skeleton potentially strengthens intermolecular interactions. Two Y217 mutants lose the hydrogen bond and have their side chains withdrawn from the ligand as displayed in Fig. 7c. G283, as shown in Fig. 7d, has its side chain extended to the flavonoid skeleton after mutation, and because of the hydrophobic nature of V, I, and L, mutants can potentially form stronger hydrophobic interactions with the ligand and stabilize the binding.

FIG 7.

Enzyme-ligand interactions before and after mutation. (a) wild type; (b) F205 mutants (F205H, orange; F205V, yellow; F205L, green); (c) Y217 mutants (Y217F, green; Y217S, yellow); (d) G283 mutants (G283T, navy; G283L, yellow; G283V, green).

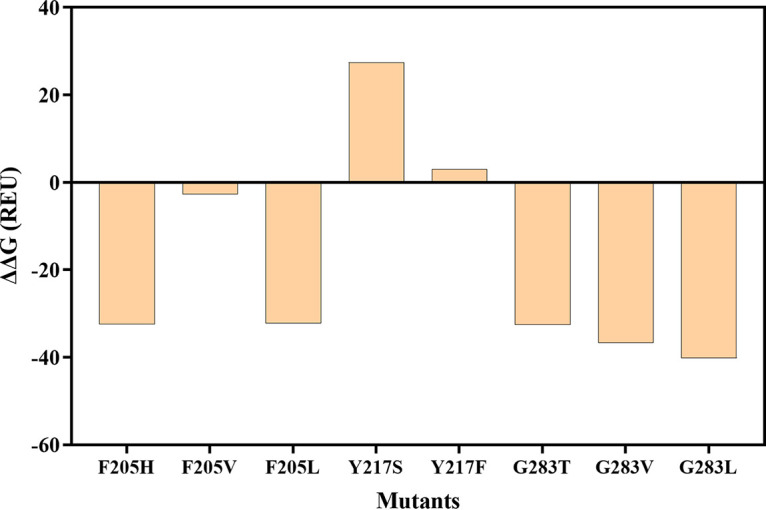

Changes of binding energy (ΔΔG) before and after mutagenesis were further analyzed based on equation 4 using the Rosetta scoring function (64, 65).

| (4) |

The three mutations at G283 all result in reduced binding energy as shown in Fig. 8, suggesting their enhanced ligand affinity. The order of stabilization effect G283L>G283V>G283T is consistent with the STAs as assayed. Ligand stabilization effect was also observed in the mutations at F205. The positive effect at Y217 can still be dominated by the reduced steric hindrance due to the reduced ligand affinity, which is consistent with the enhanced KmA value, but the two effects can work in combination. For example, Y217S, with smaller side chain than Y217F, displays lower STA due to its destabilizing effect. F205V, despite of its smallest side chain among the three F205 mutants, exhibits lower STA due to its weakest ligand stabilization effect.

FIG 8.

Changes of binding energy (ΔΔG) before and after mutagenesis.

Conclusions.

This study focused on the engineering of a wild-type CGTase in order to improve its transglycosylation activity in synthesizing α-glycosyl hesperidin. Seven residues were rationally chosen to be engineered at the aglycon attacking site that aims to optimize the enzyme-ligand interactive pattern. An extremely condensed library with 32 mutants was constructed and eight were screened to be positive. The best mutant Y217F exhibited 6.43-fold higher kcat/KmA value than the wild type. Positive mutants were found to be focalized on F205, Y217, and G283. From a structural aspect, F205 and Y217 were found at the entrance of the catalytic pocket. Their positive effect most likely a result of the easier transportation of hesperidin from the bulk environment to the catalytic pocket. Further molecular docking and binding energy analysis revealed that F205 mutants also help to stabilize the attacking pose of hesperidin, and such stabilization effect can also be provided by positive mutants at G283 (G283T, G283V, and G283L) with extended side chain. The assayed transglycosylation activities strongly suggest that the two effects of ligand transfer and binding work in combination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials, plasmids, and strains.

The nucleotide sequence encoding CGTase (NCBI accession number BAA31539.1) was synthesized with polyhistidine tag attached on the C-terminus (66). The synthesized sequence was amplified by PCR with a Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA polymerase Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols and purified using a gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Guangzhou, China). The plasmid pET-22b(+) was linearized by BamHI and NdeI (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China) and purified with a gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Guangzhou, China). The recombinant vector pET-22b(+)/CGTase-6×His was constructed by ligating the purified PCR product and the linearized pET-22b(+) with a One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). E. coli BL21(DE3) were maintained at the Institute of Fermentation Technology, Zhejiang University of Technology, and used for heterologous expression of the wild-type CGTase and its mutants. Hesperidin, dextrin, and other chemicals where purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). His60 Ni Superflow Resin & Gravity Columns (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China) was purchased from TaKaRa Bio (Dalian, China).

Structure modeling and molecular docking.

Theoretical structure was obtained by performing homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL (67) with the crystal structures of Bacillus circulans strain 251 CGTase (PDB: 1CDG) as template (44). Crystal structure of the enzyme in complex with a maltononaose inhibitor (PDB: 2DIJ) was referred to determine the aglycon attacking site (45). Crystal structure of the enzyme’s covalent complex (PDB: 1CXL) (62) was used to perform molecular docking using Autodock (68), and one docked structure with 2.807 Å distance between the bond forming atoms was selected for further analysis. Binding energies before and after mutation (ΔΔG) were calculated based on the Rosetta scoring function (64, 65).

Preparation of mutant libraries.

Primers were synthesized as listed in Table 3. Target mutation was constructed by amplifying the entire plasmid pET-22b(+)/CGTase-6×His using the corresponding primers. PCR conditions were followed according to the instructions of Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA polymerase kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). PCR product was then digested with Dpn I (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) and circulated with One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), leading to the plasmid with the target mutation. The plasmid was then transformed into competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The above procedures were repeated with different primers to create the libraries with CGTase mutants for screening.

TABLE 3.

Primers used for point mutations

| Primersa | Sequence (5′−3′ direction) xxx: mutation site |

Target mutation (codon) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F205-R | tatgaggatagcatttaccgcaatctgtat | L | V | Y | H | ||

| F205-F | gtaaatgctatcctcatagctgctxxxatccgt | (taa) | (aac) | (ata) | (atg) | ||

| Y217-R | gcggattacgatctgaataacaccgtgatg | S | R | H | F | ||

| Y217-F | attcagatcgtaatccgccagatcxxxcagatt | (gct) | (gcg) | (atg) | (aaa) | ||

| A252-R | cacatgagcgaaggctggcagactagcctg | L | V | F | G | T | S |

| A252-F | ccagccttcgctcatgtgtttaacxxxatccac | (cag) | (cac) | (aaa) | (gcc) | (ggt) | (gct) |

| K254-R | ttgatggcattcgcgtggatgcggttxxxcacatgagcgaag | H | R | L | S | I | |

| K254-F | cacgcgaatgccatcaatgcctttgtccagcca | (cat) | (cgc) | (ctg) | (agc) | (att) | |

| H255-R | gaaggctggcagactagcctgatgagcgatatt | Y | S | R | F | ||

| H255-F | gctagtctgccagccttcgctcatxxxtttaac | (gta) | (gct) | (gcg) | (gaa) | ||

| F281-R | agcggcgaagttgatccgcagaaccatcat | L | V | H | Y | ||

| F281-F | cggatcaacttcgccgctgcccagxxxccattc | (taa) | (cac) | (atg) | (ata) | ||

| G283-R | ggcgaagttgatccgcagaaccatcattttgcg | S | V | T | L | F | |

| G283-F | gttctgcggatcaacttcgccgctxxxcagaaa | (gct) | (cac) | (ggt) | (cag) | (aaa) | |

F: forward, R: reverse.

Screening of positive mutants.

Two rounds of screening were performed to obtain the positive mutants. For the first round of screening, recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were inoculated to 50 mL aliquots of LB medium with 10 g/L glycerol and 100 mg/L ampicillin in shake flasks. After culturing at 37°C for 6 h, 50 μL of IPTG (500 mM) was supplemented, and the incubation temperature was reduced to 22°C for CGTase expression. After another 4 h of culturing, the cells were harvested and OD600 of each culture were determined. Whole-cell catalysis was performed with the culture under 40°C and pH = 10.0 adjusted by 1 M NaOH. Dextrin (100 g/L, DE = 13.31 determined by DNS method) and hesperidin (10 g/L) were supplemented as glycosyl donor and acceptor, respectively. WCTA was determined using equation 1, where CS,0 and CS,t (g/L) stand for the hesperidin concentrations at the beginning and 60 min after the reaction, and MS is the molecular weight of hesperidin. Samples were added to 1 M NaOH to quench the reaction. Mutants with WCTA larger than the wild type were subjected to the second round of screening.

The second round of screening was performed with CGTase purified according to the procedures described in our previous study (17). The obtained CGTases were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and the protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method. Specific transglycosylation activities (STA) were assayed by adding 20 μL enzyme to 2 mL solution containing dextrin (100 g/L, DE = 13.31) and hesperidin (10 g/L) under 40°C at pH = 10.0 adjusted by 1 M NaOH. STA was determined by equation 2, where CS,0 and CS,t (g/L) stand for the hesperidin concentrations at the beginning and 15 min of the reaction, MS is the molecular weight of hesperidin, and CE (g/L) stands for the protein concentration.

Influence of reaction pH and temperature on hesperidin glycosylation.

Effect of pH and temperature was analyzed with purified enzymes. STAs were assayed as described at pH ranging from 10.0 to 12.0, and temperature ranging from 20°C to 70°C. Enzyme stability was studied by assaying STAs under 40°C at pH = 10.0 after being incubated in a metal bath at 30°C to 60°C with different durations.

Disproportion kinetics of wild-type CGTase and Y217F mutant.

Disproportionation kinetic parameters were measured for 15 min under 40°C at pH = 10.0 using purified enzymes. Glycosylation rate was detected by various hesperidin concentration from 6 g/L to 14 g/L while fixing maltodextrin concentration at 1.5 g/L, and various maltodextrin concentration from 1 g/L to 2.5 g/L while fixing hesperidin concentration at 8 g/L. The obtained experimental data were fit to the ping-pong mechanism as in equation 3 (47), where v (g/L min·mg) stands for the disproportion rate catalyzed by 1 mg of enzyme, [A] and [B] stands for the hesperidin and maltodextrin concentrations (g/L), respectively.

α-glycosyl hesperidin production by batch whole-cell catalysis.

CGTase-wild type and CGTase-Y217F expressing recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) strains were cultured in 2 L fermenters by batch fermentation according to the procedures as previously described (17). Cells were harvested when OD600 reaches ~20. Batch whole-cell catalysis were performed by mixing cell cultures with substrate solutions in a 1:3 volume ratio under 40°C and pH = 10.0. Catalytic media initially contain 100 g/L dextrin and 30 g/L hesperidin. Samples were taken periodically to analyze the media composition.

Data availability.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of the wild-type CGTase are available at NCBI (accession number BAA31539.1). Other data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21908196), and National Ten Thousand Talent Program (2017). We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Xiaolong Chen, Email: richard_chen@zjut.edu.cn.

Haruyuki Atomi, Kyoto University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. 2014. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D490–D495. 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeček Š, Svensson B, MacGregor E. 2014. α-Amylase: an enzyme specificity found in various families of glycoside hydrolases. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:1149–1170. 10.1007/s00018-013-1388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uitdehaag JC, van der Veen BA, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. 2002. Catalytic mechanism and product specificity of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase, a prototypical transglycosylase from the α-amylase family. Enzyme Microb Technol 30:295–304. 10.1016/S0141-0229(01)00498-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uitdehaag JC, Van Alebeek GJW, van der Veen BA, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. 2000. Structures of maltohexaose and maltoheptaose bound at the donor sites of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase give insight into the mechanisms of transglycosylation activity and cyclodextrin size specificity. Biochemistry 39:7772–7780. 10.1021/bi000340x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szerman N, Schroh I, Rossi AL, Rosso AM, Krymkiewicz N, Ferrarotti SA. 2007. Cyclodextrin production by cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans DF 9R. Bioresour Technol 98:2886–2891. 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greffe L, Jensen MT, Bosso C, Svensson B, Driguez H. 2003. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of branched oligo-and polysaccharides as potential substrates for starch active enzymes. Chembiochem 4:1307–1311. 10.1002/cbic.200300692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitahata S, Hara K, Fujita K, Nakano H, Kuwahara N, Koizumi K. 1992. Acceptor specificity of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus stearothermophilus and synthesis of α-D-glucosyl O-β-D-galactosyl-(1→4)-β-D-glucoside. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 56:1386–1391. 10.1271/bbb.56.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin MT, Alcalde M, Plou FJ, Dijkhuizen L, Ballesteros A. 2001. Synthesis of malto-oligosaccharides via the acceptor reaction catalyzed by cyclodextrin glycosyltransferases. Biocatal Biotransform 19:21–35. 10.3109/10242420109103514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gastón JAR, Costa H, Rossi AL, Krymkiewicz N, Ferrarotti SA. 2012. Maltooligosaccharides production catalysed by cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans DF 9R in batch and continuous operation. Process Biochem 47:2562–2565. 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song K, Sun J, Wang W, Hao J. 2021. Heterologous expression of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase my20 in Escherichia coli and its application in 2-O-α-D-glucopyranosyl-L-ascorbic acid production. Front Microbiol 12:664339. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.664339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poomipark N, Chaisin T, Kaulpiboon J. 2020. Synthesis and evaluation of antioxidant and β-glucuronidase inhibitory activity of hesperidin glycosides. Agric Nat Resour 54:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi SS, Park HR, Lee K. 2021. A comparative study of rutin and rutin glycoside: antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory effect, effect on platelet aggregation and blood coagulation. Antioxidants 10:1696. 10.3390/antiox10111696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han R, Chai B, Jiang Y, Ni J, Ni Y. 2022. Engineering of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Paenibacillus macerans for enhanced product specificity of long-chain glycosylated sophoricosides. Mol Catal 519:112147. 10.1016/j.mcat.2022.112147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han R, Ge B, Jiang M, Xu G, Dong J, Ni Y. 2017. High production of genistein diglucoside derivative using cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Paenibacillus macerans. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 44:1343–1354. 10.1007/s10295-017-1960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi Q, Zimmermann W. 2005. Cyclodextrin glucanotransferase: from gene to applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 66:475–485. 10.1007/s00253-004-1781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudiminchi RK, Towns A, Varalwar S, Nidetzky B. 2016. Enhanced synthesis of 2-O-α-D-glucopyranosyl-l-ascorbic acid from α-cyclodextrin by a highly disproportionating CGTase. ACS Catal 6:1606–1615. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Alfonso JL, Poveda A, Arribas M, Hirose Y, Fernández-Lobato M, Olmo Ballesteros A, Jiménez-Barbero J, Plou FJ. 2021. Polyglucosylation of rutin catalyzed by cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from Geobacillus sp.: optimization and chemical characterization of products. Ind Eng Chem Res 60:18651–18659. 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c03070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kometani T, Terada Y, Nishimura T, Takii H, Okada S. 1994. Transglycosylation to hesperidin by cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from an alkalophilic Bacillus species in alkaline pH and properties of hesperidin glycosides. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 58:1990–1994. 10.1271/bbb.58.1990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Veen BA, Uitdehaag JC, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. 2000. Engineering of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase reaction and product specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1543:336–360. 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han R, Li J, Shin HD, Chen RR, Du G, Liu L, Chen J. 2014. Recent advances in discovery, heterologous expression, and molecular engineering of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase for versatile applications. Biotechnol Adv 32:415–428. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leemhuis H, Kelly RM, Dijkhuizen L. 2010. Engineering of cyclodextrin glucanotransferases and the impact for biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:823–835. 10.1007/s00253-009-2221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly RM, Dijkhuizen L, Leemhuis H. 2009. The evolution of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase product specificity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 84:119–133. 10.1007/s00253-009-1988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penninga D, Strokopytov B, Rozeboom HJ, Lawson CL, Dijkstra BW, Bergsma J, Dijkhuizen L. 1995. Site-directed mutations in tyrosine 195 of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251 affect activity and product specificity. Biochemistry 34:3368–3376. 10.1021/bi00010a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YH, Bae KH, Kim TJ, Park KH, Lee HS, Byun SM. 1997. Effect on product specificity of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem Mol Biol Int 41:227–234. 10.1080/15216549700201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonnendecker C, Zimmermann W. 2019. Change of the product specificity of a cyclodextrin glucanotransferase by semi-rational mutagenesis to synthesize large-ring cyclodextrins. Catalysts 9:242. 10.3390/catal9030242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Zhang J, Wang M, Gu Z, Du G, Li J, Wu J, Chen J. 2009. Mutations at subsite −3 in cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Paenibacillus macerans enhancing α-cyclodextrin specificity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 83:483–490. 10.1007/s00253-009-1865-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa H, Distéfano AJ, Marino-Buslje C, Hidalgo A, Berenguer J, de Jiménez Bonino MB, Ferrarotti SA. 2012. The residue 179 is involved in product specificity of the Bacillus circulans DF 9R cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 94:123–130. 10.1007/s00253-011-3623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ara KZG, Linares-Pastén JA, Jönsson J, Viloria-Cols M, Ulvenlund S, Adlercreutz P, Karlsson EN. 2021. Engineering CGTase to improve synthesis of alkyl glycosides. Glycobiology 31:603–612. 10.1093/glycob/cwaa109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han R, Liu L, Shin HD, Chen RR, Du G, Chen J. 2013. Site-saturation engineering of lysine 47 in cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Paenibacillus macerans to enhance substrate specificity towards maltodextrin for enzymatic synthesis of 2-OD-glucopyranosyl-L-ascorbic acid (AA-2G). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:5851–5860. 10.1007/s00253-012-4514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao X, Wang T, Su L, Wu J. 2018. Enhanced 2-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-l-ascorbic acid synthesis through iterative saturation mutagenesis of acceptor subsite residues in Bacillus stearothermophilus NO2 cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase. J Agric Food Chem 66:9052–9060. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han R, Ni J, Zhou J, Dong J, Xu G, Ni Y. 2020. Engineering of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase reveals pH-regulated mechanism of enhanced long-chain glycosylated sophoricoside specificity. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e00004-20. 10.1128/AEM.00004-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Mauro A, Fallico B, Passerini A, Rapisarda P, Maccarone E. 1999. Recovery of hesperidin from orange peel by concentration of extracts on styrene−divinylbenzene resin. J Agric Food Chem 47:4391–4397. 10.1021/jf990038z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homayouni F, Haidari F, Hedayati M, Zakerkish M, Ahmadi K. 2018. Blood pressure lowering and anti-inflammatory effects of hesperidin in type 2 diabetes; a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res 32:1073–1079. 10.1002/ptr.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valls RM, Pedret A, Calderón-Pérez L, Llauradó E, Pla-Pagà L, Companys J, Moragas A, Martín-Luján F, Ortega Y, Giralt M, Romeu M, Rubió L, Mayneris-Perxachs J, Canela N, Puiggrós F, Caimari A, Del Bas JM, Arola L, Solà R. 2021. Effects of hesperidin in orange juice on blood and pulse pressures in mildly hypertensive individuals: a randomized controlled trial (Citrus study). Eur J Nutr 60:1277–1288. 10.1007/s00394-020-02279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammadi M, Ramezani-Jolfaie N, Lorzadeh E, Khoshbakht Y, Salehi-Abargouei A. 2019. Hesperidin, a major flavonoid in orange juice, might not affect lipid profile and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Phytother Res 33:534–545. 10.1002/ptr.6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg A, Garg S, Zaneveld LJD, Singla AK. 2001. Chemistry and pharmacology of the citrus bioflavonoid hesperidin. Phytother Res 15:655–669. 10.1002/ptr.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YS, Woo JB, Ryu SI, Moon SK, Han NS, Lee SB. 2017. Glucosylation of flavonol and flavanones by Bacillus cyclodextrin glucosyltransferase to enhance their solubility and stability. Food Chem 229:75–83. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada M, Tanabe F, Arai N, Mitsuzumi H, Miwa Y, Kubota M, Chaen H, Kibata M. 2006. Bioavailability of glucosyl hesperidin in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:1386–1394. 10.1271/bbb.50657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kometani T, Terada Y, Nishimura T, Takii H, Okada S. 1994. Purification and characterization of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from an alkalophilic Bacillus species and transglycosylation at alkaline pHs. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 58:517–520. 10.1271/bbb.58.517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Z, Lonsdale R, Wu L, Li G, Li A, Wang J, Zhou J, Reetz MT. 2016. Structure-guided triple-code saturation mutagenesis: efficient tuning of the stereoselectivity of an epoxide hydrolase. ACS Catal 6:1590–1597. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Z, Lonsdale R, Ilie A, Li G, Zhou J, Reetz MT. 2016. Catalytic asymmetric reduction of difficult-to-reduce ketones: triple-code saturation mutagenesis of an alcohol dehydrogenase. ACS Catal 6:1598–1605. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandström AG, Wikmark Y, Engström K, Nyhlén J, Bäckvall JE. 2012. Combinatorial reshaping of the Candida antarctica lipase A substrate pocket for enantioselectivity using an extremely condensed library. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:78–83. 10.1073/pnas.1111537108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans BS, Chen Y, Metcalf WW, Zhao H, Kelleher NL. 2011. Directed evolution of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase AdmK generates new andrimid derivatives in vivo. Chem Biol 18:601–607. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawson CL, van Montfort R, Strokopytov B, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, de Vries GE, Penninga D, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. 1994. Nucleotide sequence and X-ray structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251 in a maltose-dependent crystal form. J Mol Biol 236:590–600. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strokopytov B, Knegtel RM, Penninga D, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. 1996. Structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase complexed with a maltononaose inhibitor at 2.6 Å resolution. Implications for product specificity. Biochemistry 35:4241–4249. 10.1021/bi952339h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H, Yang S, Xu A, Jiang R, Tang Z, Wu J, Zhu L, Liu S, Chen X, Lu Y. 2019. Insight into the glycosylation and hydrolysis kinetics of alpha-glucosidase in the synthesis of glycosides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:9423–9432. 10.1007/s00253-019-10205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Veen BA, van Alebeek GJW, Uitdehaag JC, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. 2000. The three transglycosylation reactions catalyzed by cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans (strain 251) proceed via different kinetic mechanisms. Eur J Biochem 267:658–665. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gastón JAR, Szerman N, Costa H, Krymkiewicz N, Ferrarotti SA. 2009. Cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans DF 9R: activity and kinetic studies. Enzyme Microb Technol 45:36–41. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2009.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Veen BA, Leemhuis H, Kralj S, Uitdehaag JC, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. 2001. Hydrophobic amino acid residues in the acceptor binding site are main determinants for reaction mechanism and specificity of cyclodextrin-glycosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 276:44557–44562. 10.1074/jbc.M107533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uitdehaag JC, Kalk KH, van der Veen BA, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. 1999. The cyclization mechanism of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase (CGTase) as revealed by a γ-cyclodextrin-CGTase complex at 1.8-Å resolution. J Biol Chem 274:34868–34876. 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kong D, Wang L, Su L, Wu J. 2021. Effect of Leu277 on disproportionation and hydrolysis activity in Bacillus stearothermophilus NO2 cyclodextrin glucosyltransferase. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e03151-20. 10.1128/AEM.03151-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leemhuis H, Rozeboom HJ, Wilbrink M, Euverink GJW, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. 2003. Conversion of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase into a starch hydrolase by directed evolution: the role of alanine 230 in acceptor subsite+ 1. Biochemistry 42:7518–7526. 10.1021/bi034439q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly RM, Leemhuis H, Dijkhuizen L. 2007. Conversion of a cyclodextrin glucanotransferase into an α-amylase: assessment of directed evolution strategies. Biochemistry 46:11216–11222. 10.1021/bi701160h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han R, Liu L, Shin HD, Chen RR, Li J, Du G, Chen J. 2013. Systems engineering of tyrosine 195, tyrosine 260, and glutamine 265 in cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Paenibacillus macerans to enhance maltodextrin specificity for 2-O-d-glucopyranosyl-l-ascorbic acid synthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:672–677. 10.1128/AEM.02883-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reetz MT, Carballeira JD, Vogel A. 2006. Iterative saturation mutagenesis on the basis of B factors as a strategy for increasing protein thermostability. Angew Chem 118:7909–7915. 10.1002/ange.200602795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun Z, Lonsdale R, Kong XD, Xu JH, Zhou J, Reetz MT. 2015. Reshaping an enzyme binding pocket for enhanced and inverted stereoselectivity: use of smallest amino acid alphabets in directed evolution. Angew Chem 127:12587–12592. 10.1002/ange.201501809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reetz MT, Wu S. 2008. Greatly reduced amino acid alphabets in directed evolution: making the right choice for saturation mutagenesis at homologous enzyme positions. Chem Commun (Camb) 43:5499–5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furmanová K, Jarešová M, Byška J, Jurčík A, Parulek J, Hauser H, Kozlíková B. 2017. Interactive exploration of ligand transportation through protein tunnels. BMC Bioinf 18:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biela A, Nasief NN, Betz M, Heine A, Hangauer D, Klebe G. 2013. Dissecting the hydrophobic effect on the molecular level: the role of water, enthalpy, and entropy in ligand binding to thermolysin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 52:1822–1828. 10.1002/anie.201208561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tewari YB, Goldberg RN, Sato M. 1997. Thermodynamics of the hydrolysis and cyclization reactions of α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrin. Carbohydr Res 301:11–22. 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le Guilloux V, Schmidtke P, Tuffery P. 2009. Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinf 10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uitdehaag JC, Mosi R, Kalk KH, van der Veen BA, Dijkhuizen L, Withers SG, Dijkstra BW. 1999. X-ray structures along the reaction pathway of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase elucidate catalysis in the α-amylase family. Nat Struct Biol 6:432–436. 10.1038/8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hur S, Bruice TC. 2003. Just a near attack conformer for catalysis (chorismate to prephenate rearrangements in water, antibody, enzymes, and their mutants). J Am Chem Soc 125:10540–10542. 10.1021/ja0357846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khatib F, Cooper S, Tyka MD, Xu K, Makedon I, Popovic Z, Baker D, Players F. 2011. Algorithm discovery by protein folding game players. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:18949–18953. 10.1073/pnas.1115898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maguire JB, Haddox HK, Strickland D, Halabiya SF, Coventry B, Griffin JR, Pulavarti SVSRK, Cummins M, Thieker DF, Klavins E, Szyperski T, DiMaio F, Baker D, Kuhlman B. 2021. Perturbing the energy landscape for improved packing during computational protein design. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinf 89:436–449. 10.1002/prot.26030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohdan K, Kuriki T, Takata H, Okada S. 2000. Cloning of the cyclodextrin glucanotransferase gene from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. A2-5a and analysis of the raw starch-binding domain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 53:430–434. 10.1007/s002530051637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, Lepore R, Schwede T. 2018. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. 1998. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem 19:1639–1662. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S6. Download aem.01027-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.5 MB (550.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of the wild-type CGTase are available at NCBI (accession number BAA31539.1). Other data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.