Ixodes

spp. are commonly found on dogs and cats throughout the world. In the eastern United States, 16S rDNA sequence of Ixodes scapularis, the predominant species, reveals two clades—American and Southern. To confirm the species and clades of Ixodes spp. ticks submitted from pets, we examined ticks morphologically and evaluated 16S rDNA sequence from 500 ticks submitted from 253 dogs, 99 cats, 1 rabbit, and 1 ferret from 41 states. To estimate pathogen prevalence, flaB of Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb) sensu stricto and 16S rDNA of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ap) were amplified and sequenced. Most Ixodes spp. from the Northeast (n = 115/115; 100%) and the Midwest (n = 77/80; 96.3%) were I. scapularis, American clade. Borrelia spp. were identified in 34 of 192 (17.8%) and Ap in 5 of 192 (2.6%) I. scapularis. Two Ixodes cookei and one Ixodes texanus were identified from Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan. In contrast, 156 of 261 (59.8%) Ixodes spp. from the Southeast were I. scapularis, American clade; 86 of 261 (33.0%) were I. scapularis, Southern clade; 9 of 261 (3.4%) were Ixodes affinis; and 10 of 261 (3.8%) were I. cookei. Southern clade was significantly more common in Florida and less common in the upper South (p < 0.0001). One I. scapularis (1/242; 0.4%) from the Southeast (Kentucky) tested positive for Bb and 6 of 242 (2.5%) were positive for Ap. In the West, most (34/44; 77.3%) Ixodes spp. were Ixodes pacificus, with Ixodes angustus (n = 6) submitted from dogs in Alaska, Washington, and Oregon and Ixodes haerlei (n = 4) preliminarily identified from a dog in Montana. Pathogens were not detected in any ticks from the West. Although I. scapularis, American clade, predominated in the Northeast and Midwest, additional Ixodes spp. were found on dogs and cats in other regions and pathogens were less commonly detected. The role of less common Ixodes spp. as disease vectors, if any, warrants continued investigation.

Keywords: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi, cat, dog, Ixodes, tick

Introduction

Ticks are the most important arthropod vectors of disease agents in North America, transmitting ∼95% of vector-borne infections identified in people in the United States (Adams et al. 2016, Eisen et al. 2017). Dogs and cats in North America are commonly infested with ticks and infected with tick-borne pathogens, many of which are zoonotic (Bowman et al. 2009, Little et al. 2014, 2018, Saleh et al. 2019). Although as many as 35 different Ixodes spp. are found in North America, Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus are the most common Ixodes spp. ticks recovered from pets and people on the continent (Keirans and Clifford 1978, Koch 1982, Durden and Keirans 1996, Merten and Durden 2000, Little et al. 2018, Saleh et al. 2019). Both ticks are primary vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), sometimes referred to as Borreliella burgdorferi, but without scientific consensus, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ap), the agents of Lyme disease and granulocytic anaplasmosis, respectively, in humans, dogs, cats, and horses in North America, and are known to transmit a number of other disease agents in this region (Bowman et al. 2009, Little 2010, Adeolu and Gupta 2014, Eisen et al. 2017, Margos et al. 2020).

More than 400,000 human cases of Lyme disease are estimated to occur in the United States annually (Hinckley et al. 2014, Nelson et al. 2015, CDC, 2018), and the number of reported cases continues to increase. Ongoing geographic expansion of the tick-pathogen maintenance system has resulted in a 2.5 to 3-fold increase in the number of high incidence counties (Kugeler et al. 2015, Adams et al. 2016). Similarly, human cases of granulocytic anaplasmosis caused by Ap increased from 348 in 2000 to 5762 in 2017 (Dahlgren et al. 2015, CDC 2018). Clinical disease owing to these agents also occurs in dogs and cats (Bowman et al. 2009, Little 2010, Hoyt et al. 2018) and infection is common, with antibodies reactive to Bb or Ap identified in 5–20% of dogs and cats in endemic regions (Billeter et al. 2007, Little et al. 2014, Hoyt et al. 2018, Dewage et al. 2019).

Other Ixodes spp. are present in North America and occasionally reported from dogs and cats (Table 1). Of these, I. scapularis is the most common and occurs throughout the eastern half of the United States along with the South where Lyme disease is rare (Dennis et al. 1998, Eisen et al. 2016). As a species, I. scapularis can be divided into two clades—American and Southern—which can be further resolved into haplotypes (Norris et al. 1996). Geographic comparison shows that, although both clades and most haplotypes are found in the South, only American clade and associated haplotypes are present in the Northeast and upper Midwest (Norris et al. 1996, Qiu et al. 2002, Krakowetz et al. 2014). As I. scapularis continues to expand in North America (Sonenshine 2018), accurate understanding of the species and haplotypes infesting animals in different regions and at different times of the year may offer insight into the patterns and processes of the changing distribution of this preeminent tick vector. The aim of this study was to determine the diversity of Ixodes spp. feeding on dogs and cats throughout the United States, the haplotypes and seasonality of I. scapularis infesting pets in the eastern United States, and the prevalence of infection with pathogens in different regions.

Table 1.

Representative Reports of Ixodes spp. Other Than Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus from Dogs and Cats in North America

| Ixodes species | Dogs (number ticks) | Cats (number ticks) | State or province | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ixodes angustus | 33 | 18 | Alaska | Durden et al. (2016) |

| 1 | — | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) | |

| 1 | 3 | Maine | Rand et al. (2007) | |

| Ixodes affinis | 3 | 2 | Virginia | Nadolny and Gaff (2018) |

| — | 1 | North Carolina | Harrison et al. (2010) | |

| 1 | — | Florida | Kohls and Rogers (1953) | |

| 1 | — | South Carolina | Clark et al. (1996) | |

| 14 | — | Georgia | Wells et al. (2004) | |

| Ixodes auritulus | 1 (relocated from OR) | — | Alaska | Durden et al. (2016) |

| Ixodes Banksi | — | 1 | New York | Little et al. (2018), pers. comm. |

| Ixodes cookie | 732 | 719 | Maine | Rand et al. (2007) |

| 168 | Yes, number NR | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) | |

| 4 | 52 | Wisconsin | Lee et al. (2019) | |

| 1 | 1 | Connecticut | Magnarelli and Swihart (1991) | |

| 3 | — | Georgia | Goldberg et al. (2002) | |

| 5 | — | Oklahoma, Arkansas | Koch (1982) | |

| 2 | — | Ontario | Smith et al. (2018) | |

| 1 | — | Georgia | Wells et al. (2004) | |

| 28 | — | Ontario | James et al. (2019) | |

| Ixodes kingi | 10 | — | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) |

| Ixodes marxi | 1 | 6 | Maine | Rand et al. (2007) |

| 3 | — | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) | |

| Ixodes muris | 4 | — | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) |

| 61 | 51 | Maine | Rand et al. (2007) | |

| 41 | 43 | Maine | Lacombe et al. (1999) | |

| 1 | — | Prince Edward Island | Strong-Klefenz and Gaskill (2008) | |

| Ixodes sculptus | 1 | — | Michigan | Walker et al. (1998) |

| Ixodes texanus | 1 | — | Iowa | Darsie and Anatos (1957) |

| — | 3 | Wisconsin | Lee et al. (2019) |

NR, not reported; OR, Oregon.

Materials and Methods

Tick submissions

Veterinary practices in all 50 states were invited to submit ticks removed from cats and dogs; data analysis for this article was limited to ticks collected from March 2018 to February 2019. Ticks removed from each patient were collected in one container, placed in a sealed bag, and shipped to Oklahoma State University. Information on submission forms included patient identification, geographic location when tick was removed, and date of removal (Saleh et al. 2019). Ticks were collected by practicing veterinarians with valid veterinary-client-patient relationships; IRB approval was not required. For analysis, four main geographic regions of the United States (Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and West) were designated as previously described (Fig. 1) (Blagburn et al. 1996).

FIG. 1.

Geographic origin of haplotypes of Ixodes scapularis from pets in the United States.

Tick identification

Immediately upon receipt, tick stage was recorded (larva, nymph, male, and female) and species were identified morphologically by comparison with standard keys (USDA 1976, Keirans and Clifford 1978, Keirans and Litwak 1989, Durden and Keirans 1996). Ticks were placed in 70% alcohol and stored at −20°C. For molecular identification, individual ticks were dissected and nucleic acid extracted using a commercial kit (Illustra Genomic Prep Kit; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) according to manufacturer's instructions and a 16S rRNA gene fragment amplified as previously described (Macaluso et al. 2003, Nadolny et al. 2011). When no 16S rRNA gene sequence was available in the database (Ixodes texanus and Ixodes haerlei), a Cox1 fragment was amplified as previously described (Folmer et al. 1994). Amplicons were column-purified and sequenced directly at the Oklahoma State University Molecular Core Facility (Stillwater, OK) with an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer at the Oklahoma State University core facility. Electropherograms were verified by visual inspection, compared with all available sequences in GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and with a curated set of sequences from North American Ixodes spp. (Table 2), and GenBank accession numbers of sequences with the closest identity reported. For I. scapularis, clade (American or Southern) and haplotype (A–O) was also assigned (Qiu et al. 2002).

Table 2.

Reference Sequences from North American Ixodes spp.

| Species | Accession number | Haplotype |

|---|---|---|

| I. scapularis | AF309014 | A |

| AF309020 | B | |

| AF309015 | C | |

| AF309022 | D | |

| AF309013 | E | |

| AF309018 | F | |

| AF309027 | G | |

| AF309028 | H | |

| AF309021 | I | |

| AF309026 | J | |

| AF309019 | K | |

| AF309017 | L | |

| AF309011 | M | |

| AF309012 | N | |

| AF309013 | O | |

| I. affinis | U95879 | — |

| I. angustus | AB819225 | — |

| Ixodes cookei | U95883 | — |

| Ixodes haerlei | Not available | — |

| Ixodes pacificus | AF309008 | — |

| I. texanus | KX360412 | — |

Pathogen detection

Extracted DNA from each Ixodes spp. tick was tested for the presence of Bb and Ap using previously described nested PCR assays. In brief, ∼290 bp region of Borrelia species flagellin or ∼387 bp region of Ap 16S rRNA gene were amplified (Barbour et al. 1996, Little et al. 1997, Massung et al. 2002, Shukla et al. 2003). Amplicons were column purified (Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit; Promega) and sequenced and identified as described previously. Ap sequences were also compared with those described as human disease agents and those only reported from wild vertebrates (Massung et al. 2002).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of clade (American or Southern) of I. scapularis by region, percent of haplotype infected with pathogens, and percent of adult I. scapularis collected by month were compared using chi-squared tests with significance assigned at alpha = 0.05.

Results

Tick submissions

A total of 500 Ixodes spp. (475 adults and 25 nymphs) removed from 253 dogs, 99 cats, 1 rabbit, and 1 ferret were evaluated (Table 3), including 115 Ixodes spp. from the Northeast (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont), 80 from the Midwest (Indiana, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, and Wisconsin), 261 from the Southeast (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia), and 44 from the West (Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Washington).

Table 3.

Species, Clade, and Haplotype of Ixodes spp. Ticks (Number, %, 95% Confidence Interval) Collected from Pets in the United States

| Species | Northeast | Midwest | Southeast | West | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. scapularis | 115 (100; 96.1–100) | 77 (96.3; 89.1–99.2) | 242 (92.7; 88.9–95.4) | 0 | 434 (86.8; 83.5–89.5) |

| American | |||||

| A | 9 (7.8) | 1 (1.3) | 7 (2.9) | ||

| D | 10 (8.7) | 12(15.6) | 14 (5.8) | ||

| F | 64 (55.7) | 53 (68.8) | 86 (35.5) | ||

| H | 10 (8.7) | 2 (2.6) | 19 (7.9) | ||

| K | 2 (1.7) | 3 (3.9) | 19 (7.9) | ||

| Othera | 20 (17.4) | 5 (6.5) | 11 (4.5) | ||

| Southern | |||||

| M | — | — | 21 (8.7) | ||

| N | — | — | 44 (18.2) | ||

| O | — | 1 (1.3) | 21 (8.7) | ||

| I. angustus | — | — | — | 6 (13.6) | 6 (1.2) |

| I. affinis | — | — | 9 (3.4) | — | 9 (1.8) |

| I. cookei | — | 2 (2.5) | 10 (3.8) | — | 12 (2.4) |

| Ixodes haerlei | — | — | — | 4 (9.1) | 4 (0.8) |

| I. pacificus | — | — | — | 34 (77.3) | 34 (6.8) |

| I. texanus | — | 1 (1.3) | — | — | 1 (0.2) |

| Total Ixodes spp. | 115 | 80 | 261 | 44 | 500 |

Haplotypes E, G, I, J, and L were also identified.

All 115 Ixodes spp. (100%, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 96.1–100) from the Northeast and the majority (77/80; 96.3%, 95% CI = 89.1–99.2) from the Midwest were I. scapularis (Table 3). Two Ixodes cookei were identified from the Midwest, including a dog in Ohio and a ferret in Illinois, and one dog in Michigan had I. texanus. In the Southeast, I. scapularis constituted 242 of 261 (92.7%; 95% CI = 88.9–95.4) Ixodes spp. examined. Nine Ixodes affinis (3.5%, 95% CI = 1.7–6.5) were identified from 2 cats and 5 dogs, one of which was also infested with I. scapularis, and 10 I. cookei (3.8%, 95% CI = 2.0–7.0) were identified from 3 dogs, one of which also had I. scapularis. Of the 10 I. cookei, 5 were adults and 5 were nymphs. In the West, 34 of 44 (77.3%, 95% CI 62.8–87.3) ticks were I. pacificus, 6 were Ixodes angustus, and 4 were tentatively identified as I. haerlei. Sequences of I. haerlei are not available in the database for comparison (Table 2); those generated from this study have been deposited (Accession numbers pending).

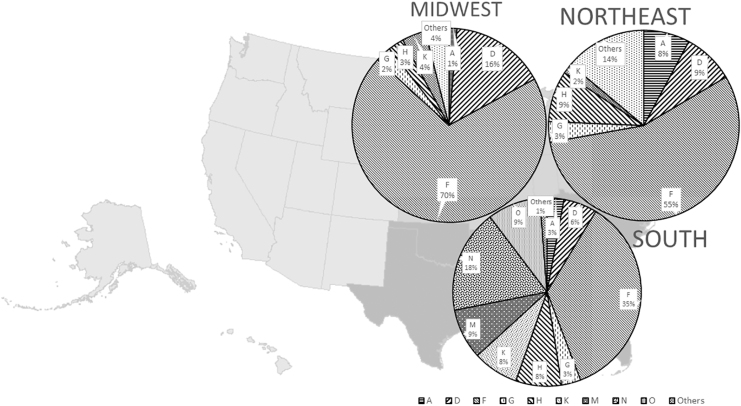

All I. scapularis from the Northeast were American clade and primarily haplotypes F (64/115; 55.7%), D (10/115; 8.7%), H (10/115; 8.7%), and A (9/115; 7.8%). Almost all (76/77; 98.7%) I. scapularis from the Midwest were American clade, primarily haplotypes F (53/77; 68.8%) and D (12/77; 15.6%); a single I. scapularis from a dog in Kansas was Southern clade, haplotype O. In the Southeast, 64.5% (156/242) of I. scapularis were American clade, including haplotypes F (86/156; 55.1%), H (19/156; 12.2%), K (19/156; 12.2%), and D (14/156; 9.0%), and 35.5% (86/242) were Southern clade including haplotypes M (21/86; 24.4%), N (44/86; 51.2%), and O (21/86; 24.4%). In Florida, the southernmost state in the range, 22% of I. scapularis were American clade (F, H) and 78% were Southern clade (M, N) (χ2 = 29.709, p < 0.0001). In the lower Southeast (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas), 47% were American clade (A, D, F, G, H, J, and K) and 53% were Southern clade (M, N, and O) (χ2 = 9.741, p = 0.0018). In the upper Southeast (Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia), 87% were American clade (A, D, F, G, H, I, K, and L) and 13% were Southern clade (M, N, and O) (χ2 = 28.071, p < 0.0001). The great majority of I. scapularis from Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, and North Carolina were American clade (81/85; 95.3%). No I. scapularis were submitted from the West (Table 3 and Fig. 1). A phylogenetic tree of the haplotypes found in different regions is provided (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of haplotypes of I. scapularis identified from pets in the United States according to geographic region. American clade is shown in blue and southern clade is shown in red.

All I. scapularis from the Southeast were adults, and collection date differed significantly by month (χ2 = 432.259, p < 0.0001), with almost all (229/242; 94.6%) collected from October to February, including adults of both American clade (149/156; 95.5%) and Southern clade (80/86; 93.0%) (Fig. 3). Most I. scapularis from the Northeast (99/115; 86.1%) were adults although nymphs (16/115; 13.9%) were also collected. Adult I. scapularis collection date in the Northeast differed significantly by month (χ2 = 111.355, p < 0.0001) and were collected primarily from April to June (41.4%; 41/99) and October through February (53.5%; 53/99) (Fig. 3). Almost all I. scapularis from the Midwest (74/77) were adults although a few nymphs (3/77; 3.9%) were also collected. Adult I. scapularis collection date in the Midwest differed significantly by month (χ2 = 76.134, p < 0.0001) and were collected primarily from April to June (52.7%; 39/74) and October through February (39.2%; 29/74) (Fig. 3). Collection date was not reported for one I. scapularis, and month of collection did not vary by clade or haplotype within a region.

FIG. 3.

Month of collection of adult I. scapularis from pets in different regions of the United States.

Pathogens detected

Pathogens were detected in a total of 44 ticks, all American clade I. scapularis and predominantly from the Northeast and Midwest. Borrelia spp. were detected in 35 I. scapularis, including 22 adult ticks in the Northeast (22/155, 14.2%; 95% CI = 9.5–20.6) and 12 adult ticks in the Midwest (12/77, 15.6%; 95% CI = 9.0–25.5). Specifically, Bb sensu stricto (CP001205, CP002228, and CP031412) was identified in 29 ticks, 28 of which were from the Northeast and Midwest; Borrelia miyamotoi (CP017126) was found in two ticks from the Northeast, and Borrelia mayonii (CP015780) in one tick from the Midwest. One I. scapularis from the Southeast, an adult female from a dog in Kentucky, also had Bb sensu stricto (Table 4). Three ticks with Borrelia spp. amplicons failed to sequence despite repeated attempts. I. scapularis that tested positive for Bb were predominantly haplotype F in the Northeast and Midwest although haplotypes A, D, G, H, and L were also found to harbor infection. Infection was not significantly more common in any I. scapularis haplotype (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Prevalence of Borreliella (Borrelia) burgdorferi sensu Stricto and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in ixodes spp. from Pets in the United States

| Species | Northeast |

Midwest |

Southeast |

West |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bb | Ap | Bb | Ap | Bb | Ap | Bb | Ap | |

| I. scapularis haplotype | 20/115 (17.4%) | 3/115 (2.6%) | 11/77 (14.3%) | 2/77 (2.6%) | 1/242 (0.4%) | 6/242 (2.5%) | — | — |

| A | 1/9 (11.1%) | 0/9 | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 | 0/7 | 0/7 | — | — |

| D | 2/10 (20%) | 1/10 | 3/12 (2.5%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 0/14 | 1/14 (7.1%) | — | — |

| H | 1/10 (10%) | 0/10 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/19 | 0/19 | — | — |

| F | 14/64 (21.9%) | 2/64 (3.1%) | 6/53 (11.3%) | 1/53 | 1/86 (1.2%) | 4/86 (4.7%) | — | — |

| G | 0/4 | 0/4 | 1/2 (50%) | 0/2 | 0/8 | 0 | — | — |

| K | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/19 | 1/19 (5.3%) | — | — |

| L | 2/4 (50%) | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/1 | 0 | — | — |

| M | — | — | — | — | 0/21 | 0/21 | — | — |

| N | — | — | — | — | 0/44 | 0/44 | — | — |

| O | — | — | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/21 | 0/21 | — | — |

| Ixodes sppa | — | — | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/19 | 0/19 | 0/44 | 0/44 |

| Total | 20 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Borrelia spp., Borreliella spp., or Ap were not detected in any ticks other than I. scapularis; Borrelia miyamotoi was identified in two ticks from the Northeast, and Borrelia mayonii was identified in one tick from the Midwest. Multiple sequencing attempts failed to identify the Borrelia/Borreliella spp. in three PCR-positive ticks.

Ap, Anaplasma phagocytophilum; Bb, Borrelia burgdorferi.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum sensu lato was detected in 11 adult I. scapularis, including 3 from the Northeast (3/115, 2.6%; 95% CI = 0.6–7.7), 2 from the Midwest (2/77, 2.6%; 95% CI = 0.2–9.5), and 6 from the Southeast (6/242, 2.5%; 95% CI = 1.0–5.4). Sequence evaluation identified human agent Ap (Ap-ha, U02521) in nine ticks, including two from the Northeast, two from the Midwest, and five from the Southeast, and Ap variant 1 (Ap-v1, AY193887) in one tick each from the Northeast and Southeast. Two I. scapularis were coinfected with both Bb and Ap. In all geographic regions the I. scapularis haplotypes that commonly tested positive for Ap were F and D. Significance between haplotype and Ap infection was not assessed because of low prevalence. Pathogens were not found in any Ixodes spp. other than I. scapularis in this study (0/66).

Discussion

I. scapularis is commonly found infesting dogs and cats in the eastern half of the United States, including in the South where infection with I. scapularis-transmitted pathogens such as Bb is rare (Koch 1982, Little et al. 2014, 2018). This study confirms that adult I. scapularis are commonly removed from pets throughout the eastern United States, although immature stages were less commonly identified. Only 4.4% of I. scapularis in this study were nymphs and all were from dogs and cats in the Northeast and Midwest. Nymphs of I. scapularis have previously been reported from cats in the northern United States, but not from cats or dogs in the South (Koch 1982, Thomas et al. 2016, Little et al. 2018), perhaps because of host preferences and questing behavior of immature stages in this region (Arsnoe et al. 2015, 2019).

Seasonality of infestation with adult I. scapularis also varied by geography. Although only identified on dogs and cats in the fall and winter in the Southeast, two periods of apparent adult activity—one in early spring and a second in fall and winter—were evident in the northern United States (Fig. 3). The single period of activity for adult I. scapularis in the Southeast is supported by findings from year-round surveys in this region, although collection efforts early in the year in the northern United States are understandably limited by inclement weather and, in some regions, snow cover (Ogden et al. 2018). The finding in this study of two apparent periods of activity for adult I. scapularis in the upper Midwest and Northeast suggests additional field research earlier in the year, when conditions allow, is warranted in this region, particularly in the face of ongoing shifts in climate (Ogden et al. 2006, 2018). Nonetheless, our data confirm that I. scapularis attaches and feeds on pets throughout the cooler months and support recommendations that dogs and cats be protected from ticks through year-round, routine acaricide use (Creevy et al. 2019).

The American clade of I. scapularis is found throughout eastern North America, whereas the Southern clade has only been reported from the southern United States (Norris et al. 1996, Qiu et al. 2002, Sakamoto et al. 2014). Haplotypes of I. scapularis from dogs and cats in this study (Table 1) largely reflected what has been reported from the environment (Qiu et al. 2002). As expected, almost all (99.5%) I. scapularis from pets in the northern United States were American clade, predominantly haplotypes F and D (Qiu et al. 2002, Sakamoto et al. 2014). The prevalence of American clade I. scapularis from pets in this study decreased with latitude, with a majority American clade in the upper Southeast, approximately half in the middle Southeast, and a minority (22%) in Florida. Although the two clades (American and Southern) of I. scapularis successfully interbreed and produce offspring, differences in phenology and host preferences in nature, particularly for immature stages, may lead to predominance of one in a given region (Oliver et al. 1993, Qiu et al. 2002, Arsnoe et al. 2015, Ogden et al. 2018).

Similar to earlier reports, Bb was detected in >15% of I. scapularis removed from pets in the northern United States in this study, but in only one I. scapularis from the Southeast (Little et al. 2014, 2018, Shannon et al. 2017). Questing ticks from the environment show a similar pathogen prevalence, with Bb commonly detected in ticks in the northeastern United States, but rarely, if at all, from the Southeast (Eisen and Eisen 2018). The single adult I. scapularis from the Southeast identified as infected with Bb in this study was removed from a dog from Kentucky, a state in the upper Southeast where established, local transmission of the agent of Lyme disease has recently been recognized (Buchholz et al. 2018, Lockwood et al. 2018). Together, these data support the longstanding interpretation that although Bb transmission risk remains high in the northern and mid-Atlantic states, and may be increasing in the upper South, much of the middle and lower southern United States does not have evidence of active Bb transmission despite the common presence of I. scapularis ticks (Oliver 1996, Little et al. 2014). Vaccination of dogs against Bb and close attention to early diagnosis and treatment is recommended in areas where Lyme borreliosis is endemic or emerging (Creevy et al. 2019).

In contrast, Ap, including the strain associated with human disease (Ap-ha), was identified in ticks removed from pets throughout the eastern United States. Indeed, several ticks from the Southeast harbored Ap-ha although human disease with this pathogen is rarely reported from this region (CDC 2018). Regardless of geographic region or specific variant, Borrelia spp. and Ap were only identified in the American clade of I. scapularis in this study, and prevalence of infection did not differ significantly by haplotype (Table 4). Continued geographic spread of I. scapularis in North America is expected to result in ongoing changes in pathogen distribution (Clow et al. 2018, Eisen and Eisen 2018). Although both Bb and Ap are vectored by I. scapularis, the patterns and processes of geographic expansion of these two agents appear to differ (Bowman et al. 2009, Little et al. 2014, McMahan et al. 2016, Watson et al. 2017).

This study confirms that a diverse array of Ixodes spp. are found on pets in the United States (Table 1), identifying seven Ixodes spp. from pets (Table 3). In addition to I. scapularis, dogs and cats in the eastern United States were infested with I. affinis, I. cookei, and I. texanus (Table 3). I. affinis is speculated to play a role in the maintenance of enzootic transmission of Bb in the southeastern United States (Oliver et al. 2003, Rudenko et al. 2013) and has been reported from dogs and cats along the southern Atlantic Coast (Table 1). Ixodes cookei is often reported from dogs and cats throughout eastern North America, whereas I. texanus is only occasionally found on pets (Table 1). In the West, I. pacificus predominated, although I. angustus and I. haerlei (tentative) were also identified (Table 3). I. haerlei is considered a rare tick (Keirans and Clifford 1978), and sequence data are not available for confirmation (Table 2). Awareness of Ixodes spp. other than I. scapularis and I. pacificus on pets is low. The findings in this article underscore the importance of accurate identification of ticks recovered from pets and expand our understanding of pet tick risk because different species are active in different seasons and habitats (Walker et al. 1998, Rand et al. 2007, Durden et al. 2016, Lee et al. 2019).

One limitation of this study is that it relied on ticks collected from dogs and cats in veterinary practices. Although this approach allowed random sampling from a wider geographic distribution than previously reported in North America, complete travel history was not available for each pet, and geographic translocation of ticks attached to pets 1–2 weeks previously may have occurred. Movement of hosts is thought to account for reports of findings such as I. scapularis on people in the western United States or dogs testing positive for Bb in the South (Little et al. 2014, Xu et al. 2019). The lack of Southern clade I. scapularis in the Northeast and the complete absence of Bb infection in I. scapularis from areas of the Southeast where the infection is not known to be autochthonously transmitted suggest such translocation events, although possible, are uncommon.

Conclusion

Seven different species of Ixodes ticks were recovered from pets in the United States, and the diversity of Ixodes spp. was particularly high in the Southeast and the West. Pathogens, including Bb, B. miyamotoi, B. mayonii, and Ap were also detected. Monitoring the species of and pathogens in Ixodes ticks from dogs and cats can enhance our understanding of the diversity, distribution, and infection risk posed by this group of arthropods.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many veterinarians and technicians who collected and submitted ticks for this research, and the members of the Little laboratory at Oklahoma State University for processing the ticks received in the national survey and maintaining the database.

Author Disclosure Statement

In the past 5 years, S.E.L. has received honoraria and research support from veterinary pharmaceutical and diagnostic companies that manufacture tick control products or diagnostic devices for tick-borne disease agents; these relationships did not influence this article. All other authors have no competing financial interests.

Funding Information

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (IIA-1920946) and by the Krull-Ewing Endowment at Oklahoma State University.

References

- Adams DA, Thomas KR, Jajosky RA, Foster L, et al. Summary of notifiable infectious diseases and conditions–United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 63:1–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeolu M, Gupta RS. A phylogenomic and molecular marker based proposal for the division of the genus Borrelia into two genera: The emended genus Borrelia containing only the members of the relapsing fever Borrelia, and the genus Borreliella gen. nov. containing the members of the Lyme disease Borrelia (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014; 105:1049–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsnoe I, Tsao JI, Hickling GJ. Nymphal Ixodes scapularis questing behavior explains geographic variation in Lyme borreliosis risk in the eastern United States. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019; 10:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsnoe IM, Hickling GJ, Ginsberg HS, McElreath R, et al. Different populations of blacklegged tick nymphs exhibit differences in questing behavior that have implications for human Lyme disease risk. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0127450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG, Maupin GO, Teltow GJ, Carter CJ, et al. Identification of an uncultivable Borrelia species in the hard tick Amblyomma americanum: Possible agent of a Lyme disease–like illness. J Infect Dis 1996; 173:403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter SA, Spencer JA, Griffin B, Dykstra CC, et al. Prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in domestic felines in the United States. Vet Parasitol 2007; 147:194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagburn BL, Lindsay DS, Vaughan JL, Rippey NS, et al. Prevalence of canine parasites based on fecal floatation. Comp Cont Ed Pract Vet 1996; 18:483–509. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman D, Little SE, Lorentzen L, Shields J, et al. Prevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in dogs in the United States: Results of a national clinic-based serologic survey. Vet Parasitol 2009; 160:138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz MJ, Davis C, Rowland NS, Dick CW. Borrelia burgdorferi in small mammal reservoirs in Kentucky, a traditionally non-endemic state for Lyme disease. Parasitol Res 2018; 117:1159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, 2017 Annual Tables of Infectious Disease Data. Atlanta, GA: CDC Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance, 2018. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/infectious-tables.html [Google Scholar]

- Clark KL, Wills W, Tedders SH, Williams DC. Ticks removed from dogs and animal care personnel in Orangeburg county, South Carolina. J Agromedicine 1996; 3:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Clow KM, Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Russell CB, et al. A field-based indicator for determining the likelihood of Ixodes scapularis establishment at sites in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 2018; 13:e019; 3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creevy KE, Grady J, Little SE, Moore GE, et al. 2019 AAHA canine life stage guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2019; 55:267–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren FS, Heitman KN, Drexler NA, Massung RF, et al. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis in the United States from 2008 to 2012: A summary of national surveillance data. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 93:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darsie RJ, Anatos G. Geographical distribution and hosts of Ixodes texanus bank (Acarina, Ixodidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 1957; 50:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis DT, Nekomoto TS, Victor JC, Paul WS, et al. Reported distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. J Med Entomol 1998; 35:629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewage BG, Little S, Payton M, Beall M, et al. Trends in canine seroprevalence to Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma spp. in the eastern USA, 2010–2017. Parasit Vectors 2019; 12:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durden LA, Beckmen KB, Gerlach RF. New records of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from dogs, cats, humans, and some wild vertebrates in Alaska: Invasion potential. J Med Entomol 2016; 53:1391–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durden LA, Keirans JE. Nymphs of the genus Ixodes of the United States. Lanham, MD: Entomological Society of America, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen RJ, Eisen L. The blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis: An increasing public health concern. Trends Parasitol 2018; 34:295–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen RJ, Eisen L, Beard CB. County-scale distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the continental United States. J Med Entomol 2016; 53:349–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen RJ, Kugeler KJ, Eisen L, Beard CB, et al. Tick-borne zoonoses in the United States: Persistent and emerging threats to human health. ILAR J 2017; 58:319–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, et al. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 1994; 3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M, Recha Y, Durden LA. Ticks parasitizing dogs in northwestern Georgia. J Med Entomol 2002; 39:112–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BA, Rayburn WH Jr., Toliver M, Powell EE, et al. Recent discovery of widespread Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) distribution in North Carolina with implications for Lyme disease studies. J Vector Ecol 2010; 35:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinckley AF, Connally NP, Meek JI, Johnson BJ, et al. Lyme disease testing by large commercial laboratories in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:676–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt K, Chandrashekar R, Beall M, Leutenegger C, et al. Evidence for clinical anaplasmosis and borreliosis in cats in Maine. Top Companion Anim Med 2018; 33:40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James CA, Pearl DL, Lindsay LR, Peregrine AS, et al. Risk factors associated with the carriage of Ixodes scapularis relative to other tick species in a population of pet dogs from southeastern Ontario, Canada. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019; 10:290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans JE, Clifford CM. The genus Ixodes in the United States: A scanning electron microscope study and key to the adults. J Med Entomol Suppl 1978; 2:1–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans JE, Litwak TR. Pictorial key to the adults of hard ticks, family Ixodidae (Ixodida: Ixodoidea), east of the Mississippi River. J Med Entomol 1989; 26:435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch HG. Seasonal incidence and attachment sites of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on domestic dogs in southeastern Oklahoma and northwestern Arkansas, USA. J Med Entomol 1982; 19:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls GM, Rogers AJ. Note on the occurrence of the tick Ixodes affinis Neumann in the United States. J Parasitol 1953; 39:669. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowetz CN, Lindsay LR, Chilton NB. Genetic variation in the mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA gene of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasit Vectors 2014; 7:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugeler KJ, Farley GM, Forrester JD, Mead PS. Geographic distribution and expansion of human Lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1455–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe EH, Rand PW, Smith RP Jr. Severe reaction in domestic animals following the bite of Ixodes muris (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol 1999; 36:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee X, Murphy DS, Hoang Johnson D, Paskewitz SM. Passive animal surveillance to identify ticks in Wisconsin, 2011–2017. Insects 2019; 10:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SE. Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40:1121–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SE, Barrett AW, Nagamori Y, Herrin BH, et al. Ticks from cats in the United States: Patterns of infestation and infection with pathogens. Vet Parasitol 2018; 257:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SE, Beall MJ, Bowman DD, Chandrashekar R, et al. Canine infection with Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma spp., and Ehrlichia spp. in the United States, 2010–2012. Parasit Vectors 2014; 7:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SE, Dawson JE, Lockhart JM, Stallknecht DE, et al. Development and use of specific polymerase reaction for the detection of an organism resembling Ehrlichia sp. in white–tailed deer. J Wildl Dis 1997; 33:246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood BH, Stasiak I, Pfaff MA, Cleveland CA, et al. Widespread distribution of ticks and selected tick-borne pathogens in Kentucky (USA). Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2018; 9:738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso KR, Mulenga A, Simser JA, Azad AF. Differential expression of genes in uninfected and rickettsia-infected Dermacentor variabilis ticks as assessed by differential-display PCR. Infect Immun 2003; 71:6165–6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnarelli LA, Swihart RK. Spotted fever group rickettsiae or Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes cookei (Ixodidae) in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29:1520–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margos G, Fingerle V, Cutler S, Gofton A, et al. Controversies in bacterial taxonomy: The example of the genus Borrelia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2020; 11:101335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massung RF, Lee K, Mauel M, Gusa A. Characterization of the rRNA genes of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophila. DNA Cell Biol 2002; 21:587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan CS, Wang D, Beall MJ, Bowman DD, et al. Factors associated with Anaplasma spp. seroprevalence among dogs in the United States. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten HA, Durden LA. A state-by-state survey of ticks recorded from humans in the United States. J Vector Ecol 2000; 25:102–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadolny RM, Gaff HD. Natural history of Ixodes affinis in Virginia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2018; 9:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadolny RM, Wright CL, Hynes WL, Sonenshine DE, et al. Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) in southeastern Virginia and implications for the spread of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. J Vector Ecol 2011; 36:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Saha S, Kugeler KJ, Delorey MJ, et al. Incidence of clinician–diagnosed Lyme disease, United States, 2005–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1625–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JS, Keirans JE, Black WCt. Population genetics of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 16S and 12S genes. J Med Entomol 1996; 33:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden NH, Maarouf A, Barker IK, Bigras-Poulin M, et al. Climate change and the potential for range expansion of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada. Int J Parasitol 2006; 36:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden NH, Pang G, Ginsberg HS, Hickling GJ, et al. Evidence for geographic variation in life-cycle processes affecting phenology of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. J Med Entomol 2018; 55:1386–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JH Jr., Lin T, Gao L, Clark KL, et al. An enzootic transmission cycle of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes in the southeastern United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:11642–11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JH Jr., Owsley MR, Hutcheson HJ, James AM, et al. Conspecificity of the ticks Ixodes scapularis and I. dammini (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol 1993; 30:54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JH Jr. Lyme borreliosis in the southern United States: A review. J Parasitol 1996; 82:926–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WG, Dykhuizen DE, Acosta MS, Luft BJ. Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the northeastern United States. Genetics 2002; 160:833–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand PW, Lacombe EH, Dearborn R, Cahill B, et al. Passive surveillance in Maine, an area emergent for tick–borne diseases. J Med Entomol 2007; 44:1118–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH Jr. The rare ospC allele L of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, commonly found among samples collected in a coastal plain area of the southeastern United States, is associated with Ixodes affinis ticks and local rodent hosts Peromyscus gossypinus and Sigmodon hispidus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:1403–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto JM, Goddard J, Rasgon JL. Population and demographic structure of Ixodes scapularis Say in the eastern United States. PLoS One 2014; 9:e101389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh MN, Sundstrom KD, Duncan KT, Ientile MM, et al. Show us your ticks: A survey of ticks infesting dogs and cats across the USA. Parasit Vectors 2019; 12:595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon AB, Rucinsky R, Gaff HD, Brinkerhoff RJ. Borrelia miyamotoi, other vector–borne agents in cat blood and ticks in eastern Maryland. Ecohealth 2017; 14:816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla SK, Vandermause MF, Belongia EA, Reed KD, et al. Importance of primer specificity for PCR detection of Anaplasma phagocytophila among Ixodes scapularis ticks from Wisconsin. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Oesterle PT, Jardine CM, Dibernardo A, et al. Powassan virus and other arthropod-borne viruses in wildlife and ticks in Ontario, Canada. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018; 99:458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine DE. Range expansion of tick disease vectors in North America: Implications for spread of tick–borne disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong-Klefenz JE, Gaskill CL. A possible canine tick-bite reaction to Ixodes muris. Can Vet J 2008; 49:280–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JE, Staubus L, Goolsby JL, Reichard MV. Ectoparasites of free-roaming domestic cats in the central United States. Vet Parasitol 2016; 228:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA. Ticks of Veterinary Importance. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Walker ED, Stobierski MG, Poplar ML, Smith TW, et al. Geographic distribution of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Michigan, with emphasis on Ixodes scapularis and Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol 1998; 35:872–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SC, Liu Y, Lund RB, Gettings JR, et al. A Bayesian spatio-temporal model for forecasting the prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi, causative agent of Lyme disease, in domestic dogs within the contiguous United States. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0174428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells AB, Durden LA, Smoyer III JH. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing domestic dogs in southeastern Georgia. J. Entomol Sci 2004; 39:426–432. [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Pearson P, Dykstra E, Andrews ES, et al. Human–biting Ixodes ticks and pathogen prevalence from California, Oregon, and Washington. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2019; 19:106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]