Abstract

Background:

The noninvasive subtype of encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (eFVPTC) has been reclassified as noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) in 2016 to reflect the indolent behavior and favorable prognosis of this type of tumor. This terminology change has also de-escalated its management approach from cancer treatment to a more conservative treatment strategy befitting a benign thyroid neoplasm.

Objective:

To characterize the reduced health care costs and improved quality of life (QOL) from management of NIFTP as a nonmalignant tumor compared with the previous management as eFVPTC.

Methods:

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed by creating Markov models to simulate two management strategies for NIFTP: (i) de-escalated management of the tumor as NIFTP involving lobectomy with reduced follow-up, (ii) management of the tumor as eFVPTC involving completion thyroidectomy/radioactive iodine ablation for some patients, and follow-up recommended for carcinoma. The model was simulated for 5 and 20 years following diagnosis of NIFTP. Aggregate costs and quality-life years were measured. One-way sensitivity analysis was performed for all variables.

Results:

Over a five-year simulation period, de-escalated management of NIFTP had a total cost of $12,380.99 per patient while the more aggressive management of the tumor as eFVPTC had a total cost of $16,264.03 per patient (saving $3883.05 over five years). Management of NIFTP provided 5.00 quality-adjusted life years, whereas management as eFVPTC provided 4.97 quality-adjusted life years. Sensitivity analyses showed that management of NIFTP always resulted in lower costs and greater quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) over the sensitivity ranges for individual variables. De-escalated management for NIFTP is expected to produce ∼$6–42 million in cost savings over a five-year period for these patients, and incremental 54–370 QALYs of increased utility in the United States.

Conclusion:

The degree of cost savings and improved patient utility of de-escalated NIFTP management compared with traditional management was estimated to be $3883.05 and 0.03 QALYs per patient. We demonstrate that these findings persisted in sensitivity analysis to account for variability in recurrence rate, surveillance approaches, and other model inputs. These findings allow for greater understanding of the economic and QOL impact of the NIFTP reclassification.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness analysis, follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features, quality-adjusted life years

Introduction

In 2016, the term noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) was proposed to reclassify noninvasive subtype of encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (eFVPTC) (1). The change in nomenclature was suggested to more accurately reflect the indolent nature of these neoplasms, as well as their favorable prognosis, a characteristic that has been demonstrated in numerous studies (1–5). Revising the nomenclature to remove the designation of “cancer” reduces both the psychosocial and financial consequences of a cancer diagnosis, and may decrease the morbidity by potentially curtailing aggressive treatment. The most updated criteria for diagnosing NIFTP are: (i) encapsulation or clear demarcation from adjacent thyroid parenchyma; (ii) follicular growth pattern with no well-formed papillae, no psammoma bodies and <30% solid/trabecular/insular growth pattern; (iii) nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC; nuclear score 2–3); (iv) no vascular or capsular invasion; and (v) no tumor necrosis or high mitotic activity (6).

eFVPTC had traditionally been managed similarly to low-risk classical PTC with the majority of guidelines recommending lobectomy (7,8). However, depending on the preferences of the patients and treating physician(s), the therapeutic intervention has occasionally been more aggressive by incorporating total/completion thyroidectomy ± radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy given the malignant diagnosis despite the favorable prognosis (9). Given the increased morbidity and cost associated with this additional therapy, the reclassification of this entity can have significant impact on both the individual patient as well as the entire health care system. Thyroid cancer has a large financial impact with an estimated $1.6 billion in U.S. health care costs in 2013, and a projected cost of $3.5 billion in 2030 (10). Diagnosis, surgery, and adjuvant therapy for newly diagnosed patients (41%) constitute the greatest proportion of costs, followed by surveillance of survivors (37%) (10). NIFTP is estimated to affect 45,000 patients annually and, if considered as a cancer, accounts for ∼4.4–9.1% of all PTC cases worldwide, with higher incidence rates in the United States (15–28%), thus creating a measurable impact on the national costs associated with thyroid disease (11,12).

The new classification of NIFTP as a premalignant lesion has led many to recommend de-escalated management consisting of lobectomy alone, and with a less aggressive surveillance regimen than recommended for low-risk differentiated thyroid malignancies (13).

The aim of this study was to characterize the impact on the extent of health care costs and decreased morbidity resulting from reclassifying and treating this disease as NIFTP compared with traditional management of the neoplasm as FVPTC. To our knowledge, the cost-effectiveness of managing NIFTP as a nonmalignant neoplasm has not been modeled. This information provides an estimate that illustrates the broader economic and quality-of-life (QOL) impact arising from a de-escalated NIFTP management.

Methods

Institutional Review Board approval from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine was waived as this study did not include any patients. A Markov state-transition patient-level model was created in TreeAge Pro Healthcare 2020 (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA) to compare de-escalated management of NIFTP compared with the management of the tumor as eFVPTC. This model intended to quantify the reduction in cost and improvement in QOL yielded by de-escalated management.

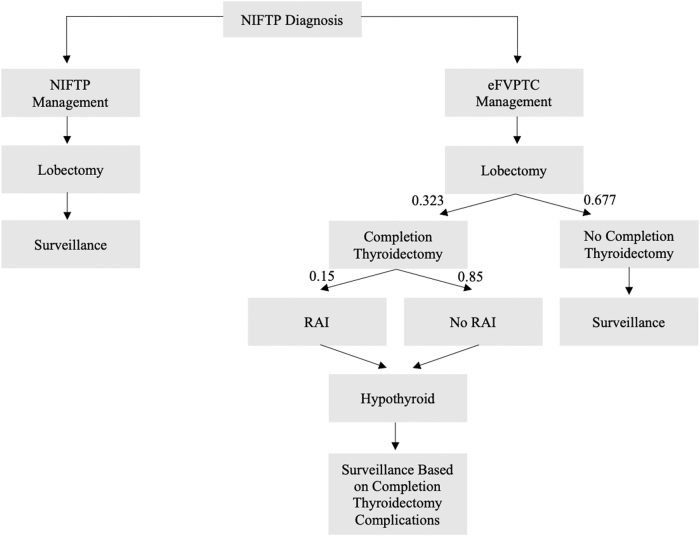

A diagram depicting the state transitions within the Markov model was created (Fig. 1). In this model, a patient diagnosed with NIFTP after lobectomy either undergoes management of the disease as eFVPTC or as NIFTP. This model simulated 5 and 20 years following diagnosis of NIFTP. The management regimen for patients diagnosed with eFVPTC ranges from conservative annual surveillance to completion thyroidectomy sometimes followed by RAI ablation. Of note, a small percentage of patients undergoing completion thyroidectomy may experience various surgical complications, including permanent and temporary recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, or permanent and temporary hypoparathyroidism (Table 1), which are not necessarily mutually exclusive (e.g., a patient who suffers temporary hypoparathyroidism may still suffer a recurrent laryngeal nerve injury).

FIG. 1.

Markov model of NIFTP management vs. eFVPTC management. eFVPTC, encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; RAI, radioactive iodine.

Table 1.

Cost-Effectiveness Comparison Between Five-Year Markov Models of De-Escalated Management as NIFTP vs. Traditional Management as eFVPTC

| Variable | 5-Year estimate | 5-Year range | 20-Year estimate | 20-Year range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost ($) | ||||

| NIFTP | 12,380.99 | 11,612.94–12,715.25 | 12,380.99 | 11,612.94–16,972.67 |

| eFVPTC | 16,264.03 | 13,243.55–16,890.07 | 21,031.43 | 17,579.91–21,731.68 |

| Difference | 3883.05 | 1630.61–4,174.83 | 8650.45 | 4759.01–5966.97 |

| Effectiveness (QALY) | ||||

| NIFTP | 5.000 | — | 20.000 | — |

| eFVPTC | 4.966 | 4.917–4.971 | 19.860 | 19.668–19.880 |

| Difference | 0.034 | 0.029–0.083 | 0.140 | 0.120–0.332 |

eFVPTC, encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

A subset of patients receiving completion thyroidectomy will also be treated with radioiodine. All patients who underwent completion thyroidectomy will necessitate lifelong hormone replacement therapy. In the other arm of the model, patients managed as NIFTP will not undergo completion thyroidectomy or RAI therapy. The range of follow-up of NIFTP patients managed in this arm was determined by the authors and ranged from a single follow-up following lobectomy to a similar follow-up recommended by the ATA guidelines for a low-risk differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) (8).

Probabilities, costs, and utilities

Each outcome described in the model was represented by a probability (probability of receiving completion thyroidectomy and RAI, probability of complications). These probabilities were identified from the literature or from expert consensus, and aggregated using a pooled analysis. The events and states simulated by the model were associated with direct costs that reflected societal cost from the payer perspective. Costs were measured in U.S. dollars and were derived from the fee schedules from the centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services and the literature. (Tables 1 and 2). Costs were inflation-adjusted to reflect costs in the year 2019 and a discount rate of 3% was used.

Table 2.

Costs Associated with Five-Year Markov Models of De-Escalated Management as NIFTP vs. Traditional Management as eFVPTC

| Parameter | Estimate | Reference (first author) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost ($) | ||

| Diagnostic cost | 1608.94 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Completion thyroidectomy w/ ND | 10,248.24 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019), Patoir |

| Completion thyroidectomy | 9364.11 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019), Patoir |

| One-year follow-up, NIFTP | 401.39 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| One-year follow-up, eFVPTC | 401.39 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Annual thyroid hormone supplementation | 110.62 | Micromedex REDBOOK (2013) |

| Lobectomy | 9212.91 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| RAI w/ rTSH | 5345.34 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| RAI w/ thyroid hormone withdrawal | 1982.24 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Thyroid complication costs | ||

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 1680.90 | White |

| Permanent RLN injury | 6742.29 | White |

| Temporary hypoparathyroidism | 883.89 | White |

| Temporary RLN injury | 2264.27 | White |

| Surgical death | 56,990.80 | White |

| Thyroid follow-up costs | 401.39 (total) | |

| Thyroglobulin + thyroglobulin Ab | 35.51 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Endocrinology follow-up | 80.01 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Surgery follow-up | 80.01 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Serum TSH | 93.35 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

| Neck ultrasound | 112.51 | CMS Fee Schedule (October 2019) |

RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; rTSH, recombinant thyroid stimulating hormone; TSH, thyrotropin.

The events and states also possessed health utilities that captured changes in QOL—health utilities ranged from 0 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which represented death, to 1 QALY (assumed to be normal follow-up after an NIFTP diagnosis). Changes in utility for surgical complications were based on their temporal nature. Utility values were identified from the literature to characterize different qualities of life caused by complications. Temporary surgical complications were assumed to last for 30 days and were prorated to incur the appropriate reduced utility (30 days/365 days in a year*health utility of complicated state) while permanent complications incurred reduced utility for the entire year. Although rare, if multiple complications occurred, the health state with the lowest utility has been assumed (e.g., a patient with hypothyroidism and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve injury would be assigned the lower of the two health utilities).

Cost and QOL analysis

After the model was run for 5 and 20 years following diagnosis of NIFTP, total costs and utilities were accrued to quantify differences between the two management strategies. While incremental cost-effectiveness ratios are typically used to compare management approaches, they were not applicable to this study as NIFTP management was expected to be less costly and more effective. One-way sensitivity analysis was also performed for cost, probability, and utility variables to determine how variance altered the cumulative costs and utilities of the two management strategies.

Results

Cost and QOL analysis

The estimated five-year cost for managing a single NIFTP patient with the traditional eFVPTC approach was $16,264.03, whereas the five-year cost of managing with a de-escalated NIFTP approach was $12,380.99. De-escalated management of NIFTP had an incremental cost savings of $3883.05 per patient over five years (Table 3). Management of NIFTP as NIFTP provided 5.00 QALYs, while management as eFVPTC provided 4.97 QALYs. Thus, de-escalated management of NIFTP had an incremental effectiveness advantage of 0.03 QALYs (Table 4). Given the incidence of NIFTP in the United States is 1613–10,885 (12.23 per 100,000 (2017 from SEER explorer) * 329,751,497 population (U.S. Census) * 4–27% NIFTP rate) (14), de-escalated management is expected to produce ∼$6–42 million in cost savings over a five-year period for these patients and incremental 54–370 QALYs of increased utility in the United States.

Table 3.

Utilities Associated with Five-Year Markov Models of De-Escalated Management as NIFTP vs. Traditional Management as eFVPTC

| Parameter | Estimate | Reference (first author) |

|---|---|---|

| Utilities (QALY) | ||

| Hypothyroid | 0.990 | Wang |

| Hypoparathyroid | 0.78 | Kebewbew, Seajan, Heller |

| Unilateral RLN injury | 0.63 | Kebewbew, Seajan, Heller |

| Hypothyroid + Hypoparathyroid | 0.630 | Heller, Leiker, Kebewbew |

| Hypoparathyroid + Unilateral RLN injury | 0.630 | Heller, Seajan, Kebewbew |

| RAI-induced sialadenitis | 0.595 | Kowalczyk |

| Recurrence | 0.540 | Kebewbew |

| Death | 0 | |

| Normal | 1.000 | |

Table 4.

Transition Probabilities Associated with Five-Year Markov Models of De-Escalated Management as NIFTP vs. Traditional Management as eFVPTC

| Parameter | Estimate | Reference (first author) |

|---|---|---|

| Transition probabilities | ||

| Completion thyroidectomy | 0.323 | Robinson, Stenson, Sugino |

| Permanent hypocalcemia w/o neck dissection | 0.024 | Pappalardo, Rafferty, Eroglu, Chao, Mishra, Kupferman, Bergamaschi, El-Sharaky |

| Permanent hypocalcemia w/ ND | 0.089 | Caliskan, Shen, Giordano (2), Eroglu, Henry, Sywak, Roh (2), Bardet, Palestini, Rosenbaum |

| Permanent RLN injury w/o ND | 0.010 | Pappalardo, Rafferty, Chao, Mishra, Kupferman, Bergamaschi, El-Sharaky |

| Permanent RLN injury w/ ND | 0.019 | Shen, Giordano (2), Henry, Sywak, Roh (2), Bardet, Palestini, Rosenbaum |

| RAI | 0.150 | Agrawal |

| Surgical death | 0.003 | Hundahl |

| Temporary hypocalcemia w/o ND | 0.101 | Pappalardo, Rafferty, Eroglu, Chao, Mishra, Kupferman, Bergamaschi, El-Sharaky |

| Temporary hypocalcemia w/ ND | 0.231 | Hundahl, Caliskan, Shen, Giordano (2), Eroglu, Henry, Lee, Sywak, Roh (2), Bardet, Palestini, Cavicchi, Rosenbaum |

| Temporary RLN w/o ND | 0.030 | Pappalardo, Rafferty, Eroglu, Chao, Mishra, Kupferman, Bergamaschi, El-Sharaky |

| Temporary RLN w/ ND | 0.043 | Hundahl, Shen, Giordano (2), Eroglu, Henry, Pereira, Sywak, Roh (2), Bardet, Palestini, Rosenbaum |

| Temporary sialadenitis w/ RAI | 0.46 | Kowalczyk |

| Permanent sialadenitis w/ RAI | 0.27 | Kowalczyk |

ND, neck dissection.

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses for incremental cost and incremental effectiveness were performed for the following variables: utilities (hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, and unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury), probabilities (completion thyroidectomy, temporary recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, temporary hypoparathyroidism), and the costs of surgical death. The sensitivity analyses demonstrated that over the ranges of each aforementioned variable, NIFTP management yielded reduced costs as well as greater/equivalent QALYs than traditional eFVPTC management (Table 5). The range of incremental cost savings of de-escalated NIFTP management across all one-way sensitivity analysis ranged from $883.61–4399.43. The variable for completion thyroidectomy probability (5.0–37.0%) accounted for the entire range of incremental costs, which was the largest sensitivity range out of any variable. The range of incremental effectiveness across all one-way sensitivity analysis ranged from 0.030 to 0.54.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Analysis of Selected Variables Using NIFTP Management as Baseline and eFVPTC as Comparator; Represents Changes in Incremental Effectiveness and Cost of eFVPTC Compared with NIFTP Management

| Parameter | Parameter range (low; high) | 5-Year range |

20-Year range |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incremental cost savings | Incremental QALY improvement | Incremental cost savings | Incremental QALY improvement | ||

| Utility | |||||

| Hypothyroid | 0.67; 0.99 | — | 0.54; 0.034 | — | 2.15; 0.14 |

| Hypoparathyroid | 0.78; 0.89 | — | 0.034; 0.030 | — | 0.14; 0.12 |

| Unilateral RLN Injury | 0.63; 0.89 | — | 0.034; 0.030 | — | 0.14; 0.12 |

| Transition probability | |||||

| Completion thyroidectomy | 0.05; 0.37 | 883.61; 4399.43 | 0.039; 0.005 | 5219.97; 9241.04 | 0.16; 0.02 |

| RAI | 0.1; 0.2 | 3826.75; 3939.33 | — | 8594.16; 8706.73 | — |

| Temporary RLN injury | 0.003; 0.03 | 3863.31; 3881.39 | — | 8630.71; 8648.79 | — |

| Temporary hypoparathyroid | 0; 0.18 | 3854.21; 3905.45 | 0.035; 0.034 | 8621.61; 8672.85 | — |

| Cost | |||||

| Surgical death | 24,874.78; 74,623.22 | 3851.92; 3900.13 | — | 8619.33; 8667.53 | — |

The lowest incremental effectiveness occurred at the highest utility states for hypoparathyroidism and unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (0.89); the highest incremental effectiveness occurred at the lowest health utility of hypothyroidism (0.67). The variable that resulted in the largest range of incremental effectiveness was the health utility of hypothyroidism.

Discussion

The Markov analysis presented in this study quantified the amount of cost savings and improved QOL resulting from de-escalated management of NIFTP compared with traditional management as eFVPTC. Over the course of five years, de-escalated management is projected to save $3883.05 and improve QOL by 0.034 QALYs per patient. The cost in this model was based on societal cost and was estimated by Medicare reimbursement information rates. In this analysis, the typical willingness-to-pay threshold did not apply because de-escalated management improved effectiveness and decreased cost. The costs saved from de-escalated management were attributed to avoiding completion thyroidectomy, surgical complications, radioiodine therapy, and additional follow-up and surveillance. The improvement in utility were attributed to reduced QOL from hypothyroidism secondary to completion thyroidectomy as well as possible iatrogenic complications from the surgery.

Given the estimated national annual incidence of 10,000 patients diagnosed with NIFTP in the United States, our estimates suggest that de-escalated NIFTP management may result in ∼$40 million decreased expenditure and 340 QALYs saved annually. However, it is important to recognize that this impact may be less pronounced in East Asian countries, where NIFTP occurrence is eight times lower than in Western Europe and North America (11). Additionally, the cost benefit would certainly be more muted in countries outside of the United States where health care costs are not as inflated.

Our results differ from a recent retrospective study of 40 NIFTP cases by Agrawal et al. reporting that aggressive NIFTP management consisting of completion thyroidectomy and/or RAI (average cost $17,629) was nearly twice the amount of conservative management consisting of initial lobectomy or appropriately indicated total thyroidectomy (average cost $8637) (15). That study did not account for complications from completion thyroidectomy or reduced follow-up in de-escalated management, and was based on the 2013 Medicare reimbursement schedule. The difference in cost savings can be mostly accounted for by the increased rates of completion thyroidectomy estimated in that study (52%) compared with the estimates of the more actual, de-escalated approach with 32% presented in this study, which is in line with recommendations by society guidelines (8,16).

The cost and effectiveness advantages persisted even when accounting for the potential of a nonzero recurrence rate, which remains a controversial topic. While most large-scale studies have supported the indolent behavior of NIFTP, there have been reports of regional recurrences or aggressive disease in a few studies (17–19). Diagnostic accuracy for NIFTP can be imperfect, especially at the onset and in lower volume settings. In a retrospective review of 102 patients reclassified as NIFTP, Parente et al. found one patient with a pulmonary metastasis and 5 patients with central neck disease (17). Cho et al. found central neck lymph node micrometastases in 3% of their cases (18), but this may have been attributed to the routine use of prophylactic central neck dissection. The highest rate of disease failure was seen in a Canadian population study by Eskander et al., in which the authors found a recurrence rate of 9.4% (20).

However, the authors acknowledged that they did not have access to the histopathologic slides for formal pathology review and thus were only able to reclassify the tumors based on the reports, thereby potentially hindering the classification accuracy. Thus, while accurately diagnosed NIFTP should have a recurrence rate of zero, we tested the model with nonzero recurrence rates to account for potential misclassification of NIFTP; of note, de-escalated management remained less expensive and more efficacious up to an assumed recurrence of 10%.

The model presented in this study also accounted for the lack of consensus on appropriate surveillance and follow-up for NIFTP. While some recommend more aggressive follow-up (17,18), others posit that the excellent prognosis and strict diagnostic criteria should allow for reduced postoperative surveillance. The American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Nodules/Differentiated Thyroid Cancer state that serum thyroglobulin measurements and ultrasound surveillance are not mandatory (8). We determined that the appropriate follow-up to apply to our baseline scenario in our model included 1full follow-up visit every six months in the first year and one full follow-up visit in the second year (Table 2). After the second year, there were no further follow-up costs. Even at the upper range of follow-up that included full follow-up annually for the entire five years of the model projection, we still observed $4174.83 cost reduction with the 0.083 QALYs of improved efficacy. As reported by Lubitz et al., 37% of DTC management costs stem from chronic surveillance; hence, appropriate reduction in surveillance can play a large role in reducing health care costs (10).

The psychological impact of a being diagnosed with cancer versus a “neoplasm” has been qualitatively examined with mixed results (21–23). Nickel et al. (21) recruited 47 individuals with no personal history of thyroid cancer for a focus group regarding changing the terminology of low-risk thyroid cancers. Overall, while the study subjects generally understood the reason for the proposed nomenclature shift, and could see potential benefits, including reducing the negative psychological impact and stigma associated with the term “cancer,” many still had reservations. The majority of the concerns were that the terminology shift may create confusion and cause patients not to take the diagnosis, and its associated managements, seriously. There was a strong overarching desire for greater patient and public education around overdiagnosis and overtreatment in thyroid cancer that should complement any revised terminology and de-intensification strategies. Another study by the same research group of 550 Australian participants in a randomized crossover trial were the study groups presented with three hypothetical scenarios where the participant is told they are diagnosed with a papillary thyroid cancer, a papillary lesion, or abnormal cells (23).

Participants were exposed to all three scenarios in a randomized fashion. A higher proportion of participants (108 [19.6%]) chose total thyroidectomy when PTC was used compared with the percentage of participants who chose total thyroidectomy when papillary lesion (58 [10.5%]) or abnormal cells (60 [10.9%]) terminology was given. At first exposure, the PTC terminology led 60 of 186 participants (32.3%) to choose surgery compared with 46 of 191 participants (24.1%) who chose surgery after being exposed to papillary lesion terminology first (risk ration [RR], 0.73; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53–1.02) and 47 of 173 participants (27.2%) after being exposed to abnormal cell (RR, 0.82; CI, 0.60–1.14) terminology first. After the first exposure, participants who viewed PTC terminology reported significantly higher levels of anxiety (mean, 7.8 of 11 points) compared with those who viewed the papillary lesion (mean, 7.0 of 11 points; mean difference, −0.8; CI, −1.3 to −0.3) or abnormal cells (mean, 7.3 of 11 points; mean difference, −0.5; CI, −1.0 to 0.01). Including a possible quantitative measure of the psychological impact, as well as additional prospective QOL data, could further help elucidate the impact of the nomenclature shift to NIFTP.

Limitations

While this model incorporates common surgical complications from thyroidectomy and neck dissections, it does not include the cost and lost QOL associated with potential complications of radioiodine therapy (e.g., sialadenitis, xerostomia, epiphora, secondary malignancies) (24). Additionally, this model does not account for lost patient work productivity from additional surgery, treatment, and follow-up appointments. Incorporating these factors, as well as prospective QOL data, would augment the estimated cost savings and utility benefits from de-escalated NIFTP management. The model is also limited by lack of consensus about the management and clinical behavior of NIFTP. The authors were consulted whenever there was ambiguity (e.g., surveillance approach), and sensitivity analysis was performed to account for the range of variability. However, the lack of specific guidelines may have prevented a more precise estimation of cost and effectiveness. Finally, since our analysis only modeled five years of management, it does not fully capture the extent of cost savings from avoiding long-term surveillance.

Conclusion

The degree of cost savings and improved patient utility of de-escalated NIFTP management compared with traditional management was estimated to be $3883.05 and 0.034 QALYs per patient. Given the estimated national annual incidence of 10,000 patients diagnosed with NIFTP in the United States, our estimates suggest that de-escalated NIFTP management may result in ∼$40 million decreased expenditure and 340 QALYs saved annually. We demonstrate that these findings persist in sensitivity analysis to account for variability in recurrence rate, surveillance approaches, and other model inputs. These findings emphasize the magnitude of the economic and QOL ramifications resulting from the NIFTP reclassification.

Authors' Contributions

V.M. and A.N.: Contribution to design of work, data acquisitions, approval of version to be published, accountability, data analysis, and drafting of the work.

D.L., L.D., B.R.H., P.A.K., S.J.M., Y.E.N., D.S.R., J.J.S., R.M.T., and G.W.R.: Contribution to design of work, data acquisitions, approval of version to be published, and accountability.

Author Disclosure Statement

G.W.R.: G.W.R. has received a research grant (no personal fees) from Eisai. G.W.R. is the President of the International Thyroid Oncology Group (ITOG) and is the Administrative Division Chair of the American Head and Neck Society (AHNS).

J.J.S.: J.J.S. receives book royalties from Evidence-Based Otolaryngology, Shin JJ, Randolph GW, editors; New York: Springer, 2008 and Otolaryngology Prep and Practice, Shin JJ, Cunningham MJ, editors; Plural Publishing, 2013.

J.J.S. is a recipient of funding from American Academy of the Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, the Brigham Care Redesign Program Award, the BWell Funds Awards, and a Brigham Innovations Award.

B.R.H.: Research support from Merck and Eiasi.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Nikiforov YE, Seethala RR, Tallini G, Baloch ZW, Basolo F, Thompson LD, Barletta JA, Wenig BM, Al Ghuzlan A, Kakudo K, Giordano TJ, Alves VA, Khanafshar E, Asa SL, El-Naggar AK, Gooding WE, Hodak SP, Lloyd RV, Maytal G, Mete O, Nikiforova MN, Nosé V, Papotti M, Poller DN, Sadow PM, Tischler AS, Tuttle RM, Wall KB, LiVolsi VA, Randolph GW, Ghossein RA. 2016. Nomenclature revision for encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a paradigm shift to reduce overtreatment of indolent tumors. JAMA Oncol 2:1023–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu J, Singh B, Tallini G, Carlson DL, Katabi N, Shaha A, Tuttle RM, Ghossein RA. 2006. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of a problematic entity. Cancer 107:1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rivera M, Ricarte-Filho J, Knauf J, Shaha A, Tuttle M, Fagin JA, Ghossein RA. 2010. Molecular genotyping of papillary thyroid carcinoma follicular variant according to its histological subtypes (encapsulated vs infiltrative) reveals distinct BRAF and RAS mutation patterns. Mod Pathol 23:1191–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosario PW, Penna GC, Calsolari MR. 2014. Noninvasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: is lobectomy sufficient for tumours ≥1 cm? Clin Endocrinol 81:630–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ganly I, Wang L, Tuttle RM, Katabi N, Ceballos GA, Harach HR, Ghossein R. 2015. Invasion rather than nuclear features correlates with outcome in encapsulated follicular tumors: further evidence for the reclassification of the encapsulated papillary thyroid carcinoma follicular variant. Hum Pathol 46:657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nikiforov YE, Baloch ZW, Hodak SP, Giordano TJ, Lloyd RV, Seethala RR, Wenig BM. 2018. Change in diagnostic criteria for noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillarylike nuclear features. JAMA Oncol 4:1125–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tarasova VD, Tuttle RM. 2017. Current management of low risk differentiated thyroid cancer and papillary microcarcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 29:290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2016. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goffredo P, Thomas SM, Dinan MA, Perkins JM, Roman SA Sosa JA. 2015. Patterns of use and cost for inappropriate radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer in the United States: use and misuse. JAMA Intern Med 175:638–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lubitz CC, Kong CY, McMahon PM, Daniels GH, Chen Y, Economopoulos KP, Gazelle GS, Weinstein MC. 2014. Annual financial impact of well-differentiated thyroid cancer care in the United States. Cancer 120:1345–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bychkov A, Jung CK, Liu Z, Kakudo K. 2018. Noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features in Asian practice: perspectives for surgical pathology and cytopathology. Endocr Pathol 29:276–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruanpeng D, Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Hennessey JV, Shrestha RT. 2019. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) on cytological diagnosis and thyroid cancer prevalence. Endocr Pathol 30:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosario PW Mourão GF 2019. Follow-up of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). Head Neck 41:833–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. SEER*Explorer. An Interactive Website for SEER Cancer Statistics. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/ (accessed April 15, 2020).

- 15. Agrawal N, Abbott CE, Liu C, Kang S, Tipton L, Patel K, Persky M, King L, Deng FM, Bannan M, Ogilvie JB, Heller K, Hodak SP. 2017. Noninvasive follicular tumor with papillary-like nuclear features: not a tempest in a teapot. Endocr Pract 23:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yi KH 2016. The Revised 2016 Korean thyroid association guidelines for thyroid nodules and cancers: differences from the 2015 American Thyroid Association Guidelines. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 31:373–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parente DN, Kluijfhout WP, Bongers PJ, Verzijl R, Devon KM, Rotstein LE, Goldstein DP, Asa SL, Mete O, Pasternak JD. 2018. Clinical safety of renaming encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: is NIFTP Truly benign? World J Surg 42:321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho U, Mete O, Kim MH, Bae JS, Jung CK. 2017. Molecular correlates and rate of lymph node metastasis of non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features and invasive follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma: the impact of rigid criteria to distinguish non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features. Mod Pathol 30:810–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hahn SY, Shin JH, Lim HK, Jung SL, Oh YL, Choi IH, Jung CK. 2017. Preoperative differentiation between noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) and non-NIFTP. Clin Endocrinol 86:444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eskander A, Hall SF, Manduch M, Griffiths R, Irish JC. 2019. A population-based study on NIFTP incidence and survival: is NIFTP really a “benign” disease? Ann Surg Oncol 26:1376–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nickel BA-O, Semsarian C, Moynihan R, Barratt A, Jordan S, McLeod D, Brito JP, McCaffery K. 2019. Public perceptions of changing the terminology for low-risk thyroid cancer: a qualitative focus group study. BMJ Open 9:e025820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shih P, Nickel B, Degeling C, Thomas R, Brito JP, McLeod DSA, McCaffery K, Carter SM. 2021. Terminology change for small low-risk papillary thyroid cancer as a response to overtreatment: results from three Australian community juries. Thyroid 31:1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nickel B, Barratt A, McGeechan K, Brito JP, Moynihan R, Howard K, McCaffery K. 2018. Effect of a change in papillary thyroid cancer terminology on anxiety levels and treatment preferences: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144:867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singer MC, Marchal F, Angelos P, Bernet V, Boucai L, Buchholzer S, Burkey B, Eisele D, Erkul E, Faure F, Freitag SK, Gillespie MB, Harrell RM, Hartl D, Haymart M, Leffert J, Mandel S, Miller BS, Morris J, Pearce EN, Rahmati R, Ryan WR, Schaitkin B, Schlumberger M, Stack BC, Van Nostrand D, Wong KK, Randolph G. 2020. Salivary and lacrimal dysfunction after radioactive iodine for differentiated thyroid cancer: American Head and Neck Society Endocrine Surgery Section and Salivary Gland Section joint multidisciplinary clinical consensus statement of otolaryngology, ophthalmology, nuclear medicine and endocrinology. Head Neck 42:3446–3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]