Abstract

Soluble forms of Bacillus signal peptidases which lack their unique amino-terminal membrane anchor are prone to degradation, which precludes their high-level production in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Here, we show that the degradation of soluble forms of the Bacillus signal peptidase SipS is largely due to self-cleavage. First, catalytically inactive soluble forms of this signal peptidase were not prone to degradation; in fact, these mutant proteins were produced at very high levels in E. coli. Second, the purified active soluble form of SipS displayed self-cleavage in vitro. Third, as determined by N-terminal sequencing, at least one of the sites of self-cleavage (between Ser15 and Met16 of the truncated enzyme) strongly resembles a typical signal peptidase cleavage site. Self-cleavage at the latter position results in complete inactivation of the enzyme, as Ser15 forms a catalytic dyad with Lys55. Ironically, self-cleavage between Ser15 and Met16 cannot be prevented by mutagenesis of Gly13 and Ser15, which conform to the −1, −3 rule for signal peptidase recognition, because these residues are critical for signal peptidase activity.

Secretory preproteins are synthesized with an amino-terminal signal peptide, which is required to target these proteins to the preprotein translocase in the membrane and initiate the translocation process (12, 27, 28). During or shortly after translocation, membrane-bound type I signal peptidases (SPases) remove this signal peptide in order to release the mature secretory protein from the trans side of the membrane (4).

To perform its functions in the secretion process, the signal peptide has a typical tripartite structure, consisting of a positively charged n region, a hydrophobic h region, and a polar c region that contains the SPase cleavage site (4, 27, 29). Statistical studies of sequences surrounding the SPase cleavage site led to the formulation of the −1, −3 or Ala-X-Ala rule, defining the preferred residues (i.e., Ala) at the −1 and −3 positions relative to the cleavage site as critical determinants for signal peptide recognition and cleavage (25, 26). In accord with this specificity rule, which applies to bacterial and endoplasmic reticulum-type SPases (5, 6, 15), mutant and wild-type preproteins are cleaved only with Ala, Gly, Ser, Cys, or Pro at the −1 position or with Ala, Gly, Ser, Cys, Thr, Val, Ile, Leu, or Pro at the −3 position. Almost any residue can be tolerated at the −2, −4, and −5 positions. Notably, SPase activity was shown to be inhibited by mutant preproteins with a Pro residue at the +1 position (1, 10). Insight into the molecular basis for this substrate specificity was gained from the recent elucidation of the crystal structure of the SPase I (also known as leader peptidase [Lep]) of Escherichia coli (11). This structure revealed relatively small hydrophobic S1 and S3 substrate-binding sites that can accommodate only side chains of small, aliphatic residues. Furthermore, these substrate-binding sites appear to be surface exposed. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the c region of a signal peptide has a β structure, which implies that the side chain of the −2 residue points in the opposite direction relative to the side chains of the −1 and −3 residues. Finally, a major outcome of analysis of the crystal structure of the E. coli SPase I was confirmation of the hypothesis that type I SPases make use of a Ser-Lys catalytic dyad (4).

Interestingly, the largest number of type I SPases in one single species has thus far been found in the gram-positive eubacterium Bacillus subtilis, which contains five paralogous chromosomally encoded enzymes of this type (SipS, SipT, SipU, SipV, and SipW) (2, 19, 20, 22). Various studies have shown that these enzymes have different but overlapping substrate specificities (19–21). This prompted us to initiate the purification and in vitro characterization of Bacillus type I SPases. To this end, we wanted to make use of soluble forms of these enzymes that, in principle, are easier to work with than detergent-solubilized intact proteins containing the membrane anchor. Recent studies have shown that the high-level production of truncated soluble forms of SipS of B. subtilis [SipS (Bsu)], SipS of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens [SipS (Bam)], and SipC of Bacillus caldolyticus in E. coli, using a T7 expression system, was difficult. Nevertheless, the hexahistidine-tagged truncated soluble form of SipS (Bam) [sf-SipS-His (Bam)] could be purified and was shown to be active without the addition of detergents or phospholipids (our unpublished results). However, as evidenced by the copurification of specific degradation products, purified sf-SipS-His (Bam) appeared to be prone to degradation. The latter observation is important, as it most likely explains why various attempts to overproduce truncated soluble signal peptidases from bacilli and other eubacterial and eukaryotic species have met with little or no success. Therefore, the present study was aimed at determining whether the high-level production of truncated soluble Bacillus SPases in E. coli was prevented by proteolysis. The results show that this is indeed the case and that self-cleavage of sf-SipS-His is the major problem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and media.

Table 1 lists the plasmids and bacterial strains used. TY medium contained Bacto Tryptone (1%), Bacto Yeast Extract (0.5%), and NaCl (1%). If required, medium for E. coli was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| MC1061 | F−araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7696 galE15 galK16 Δ(lac)X743 rpsL hsdR2 mcrA mcrB1 | 31 |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT rB− mB− λDE3 | 16 |

| B. subtilis 168 | trpC2 | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEF+ | Contains T7 promoter and terminator, f1(+) origin, and pBR322 origin; Apr, 3.1 kb | 14 |

| pS-S43A | Encodes the S43A mutant of SipS of B. subtilis; Apr Kmr, 8.1 kb | 23 |

| pS-S43C | Encodes the S43C mutant of SipS of B. subtilis; Apr Kmr, 8.1 kb | 23 |

| pS-K83A | Encodes the K83A mutant of SipS of B. subtilis; Apr Kmr, 8.1 kb | 23 |

| pGEFdSH | pGEF+ derivative; encodes sf-SipS-His of B. subtilis; Apr, 3.6 kb | This study |

| pGEFdSH-S43A | pGEF+ derivative; encodes sf-SipS-His S43A of B. subtilis; Apr, 3.6 kb | This study |

| pGEFdSH-S43C | pGEF+ derivative; encodes sf-SipS-His S43C of B. subtilis; Apr, 3.6 kb | This study |

| pGEFdSH-K83A | pGEF+ derivative; encodes sf-SipS-His K83A of B. subtilis; Apr, 3.6 kb | This study |

| pT712 | pUC12c derivative; contains the M13mp10/pUC12 polylinker downstream of the T7 promoter; Apr, 2.8 kb | GenBank accession no. L08949 |

| pT7dS | pT712 derivative; encodes sf-SipS from B. subtilis; 3.3 kb | This study |

| pT7dAH | pT712 derivative; encodes sf-SipS-His from B. amyloliquefaciens; 3.3 kb | This study |

| pGDL46.21 | Encodes SipS of B. amyloliquefaciens; Apr Ems Kmr, 8.8 kb | 9 |

DNA techniques.

Procedures for DNA purification, restriction, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli were carried out as described in reference 13. Enzymes were from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. PCR was carried out with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) as described in reference 23. DNA and protein sequences were analyzed with the PCGene program (version 6.7; Intelligenetics Inc.) and ClustalW version 1.74 (18).

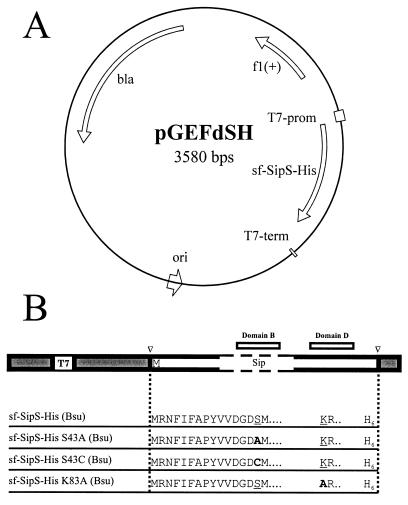

Plasmid pGEFdSH (Fig. 1A), specifying sf-SipS-His (Bsu), was constructed as follows. First, part of the sipS gene was amplified by PCR with the primers SipS009 and SipS014 (Table 2), which specify EcoRI and BamHI sites, respectively. B. subtilis 168 chromosomal DNA was used as a template. Next, after restriction with EcoRI and BamHI, this PCR-amplified fragment was subcloned in pUC18. Finally, the resulting plasmid was cleaved with RcaI and DdeI, and the resultant sipS-specific fragment was ligated into the NcoI site of the expression vector pGEF+. The same primers and a very similar cloning strategy were used to construct pGEFdSH-S43A, pGEFdSH-S43C, and pGEFdSH-K83A, specifying truncated hexahistidine-tagged forms of SipS with the S43A, S43C, and K83A mutations, respectively (Fig. 1B). For this purpose, plasmids pS-S43A, pS-S43C, and pS-K83A (23) were used as templates for PCR. In pGEF+, the translation of genes, cloned in the NcoI site downstream of the T7 promoter, is controlled by a ribosome-binding site and ATG start codon derived from pET-3d (14). The latter start codon was used as the translation start for all pGEF+-based sipS constructs used in this study. Plasmid pT7dS, specifying sf-SipS (Bsu), was constructed by ligating a SalI- and BamHI-cleaved PCR-amplified fragment of sipS (Bsu) into the corresponding sites of pT712. The sipS (Bsu)-specific fragment was amplified by PCR with the primers SipS001 and Lbs91 (Table 2), using B. subtilis 168 chromosomal DNA as a template. Plasmid pT7dAH, specifying sf-SipS-His (Bam), was constructed by ligating an EcoRI- and SalI-cleaved PCR-amplified fragment of sipS (Bam) into the corresponding sites of pT712. The sipS (Bam)-specific fragment was amplified by PCR with the primers SipA001 and SipAHis02 (Table 2), using pGDL46.21 as a template. In pT7dS and pT7dAH, the translation of sip genes, cloned downstream of the T7 promoter, is controlled by the efficient ribosome-binding site and start codon from the B. subtilis obg gene (30). To prevent the selection of nonoverexpressing variants, all plasmids were first constructed using E. coli MC1061, which does not contain the gene for the T7 RNA polymerase.

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of constructs for overproduction of truncated soluble SPases. (A) Vector pGEFdSH is derived from pGEF+ (14) and contains the sf-sipS-His gene under the transcriptional control of the T7 promoter (T7-prom), the origin of replication of pBR322 (ori), an f1(+) origin of replication, and a β-lactamase gene (bla). (B) All constructs used for the overproduction of sf-SipS-His (Bsu), sf-SipS-His S43A (Bsu), sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu), and sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu) are based on plasmid pGEF+ (filled areas). PCR-amplified sequences specifying the sf-Sip proteins were cloned downstream of the T7 promoter of pGEF+, using the unique NcoI restriction site marked with a triangle. The catalytic Ser and Lys residues of SipS are underlined. Residues used to replace the active-site Ser and Lys residues are indicated in bold. All sf-SipS proteins contain a C-terminal hexahistidine tag (H6). Conserved domains B and D, as defined in references 4, 22, and 23, are indicated as boxes.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| Lbs91 | CGGGATCCCGGGACTAATTTGTTTTGCGC |

| SipS001 | GACTAGTCGACGGAGGACAATTATGCGCAACTTTATTTTTGC |

| SipS009 | GGAATTCATGAGAAACTTTATTTTTGCGCCG |

| SipS014 | CGGGATCCTCATGACTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGATTTGTTTTGCGCATTTCG |

| SipA001 | GGAATTCGTCGACGGAGGACAATTATGCGCAACTTTTTATTTGCTCC |

| SipAHis02 | GGAATTCTTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGATCGATTTCGTCTTGCGAA |

Protein overproduction and purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for the isopropyl-B-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced overproduction of sf-SipS-His (Bam), sf-SipS (Bsu), sf-SipS-His (Bsu), sf-SipS-His S43A (Bsu), sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu), or sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu). For this purpose, transformants containing pT7dAH, pT7dS, pGEFdSH, pGEFdSH-S43A, pGEFdSH-S43C, or pGEFdSH-K83A were grown overnight in TY medium at 37°C. One liter of fresh TY medium was inoculated with 10 ml of this overnight culture and incubated at 37°C. When the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.9, the production of SPase was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cells were collected by centrifugation ±3 h after induction. In the case of sf-SipS-His (Bam) and sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu), the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM phosphoramidon, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] [pH 8.0] and disrupted by three passages through a chilled French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2. Cells and debris were removed from the extract by centrifugation at 5,000 × g (15 min, 4°C). To separate the soluble sf-SipS-His (Bam) or sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) from the membrane-bound E. coli SPase I, membranes were removed from the supernatant by two subsequent ultracentrifugation steps (100,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). Finally, sf-SipS-His (Bam) or sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) was isolated by metal affinity chromatography, using a column containing 5 ml of Talon resin (Clontech Laboratories Inc.) that was preequilibrated with lysis buffer. The column was washed with 25 ml of lysis buffer, and sf-SipS-His (Bam) or sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) was eluted with elution buffer (lysis buffer with 300 mM imidazole). To verify the level of purification, samples from 0.5-ml fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequent staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) or by Western blotting. Fractions containing the purified sf-SipS-His (Bam) were pooled and transferred to a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0) by gel filtration with a PD-10 Sephadex G-25 M column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Pure sf-SipS-His (Bam) was stored at either 4 or −80°C in the presence of 20% (vol/vol) glycerol.

Sf-SipS-His S43A (Bsu) and sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu) were purified from cytosolic inclusion bodies. For this purpose, pGEFdSH-S43A- or pGEFdSH-K83A-containing cells were grown and induced as described above. Cells collected by centrifugation were resuspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), and 1.5 mg of lysozyme per ml was added. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C, the cells were disrupted by three passages through a chilled French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2. The lysate was centrifuged at 27,000 × g to collect the inclusion bodies. To remove contaminating membranes and membrane proteins, the inclusion body-containing pellet was washed twice by resuspension in 5 ml of lysis buffer with 0.5% Triton X-100 and once in lysis buffer without Triton X-100. After each washing step, the inclusion bodies were collected by centrifugation at 27,000 × g. Next, the inclusion body pellet was dissolved in 5 ml of guanidinium-HCl buffer (4 M guanidinium-HCl, 30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]). Finally, to remove undissolved material, the resulting solution was centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g. Sf-SipS-His S43A (Bsu) and sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu) were further purified to homogeneity by metal affinity chromatography. For this purpose, the supernatant was mixed with 5 ml of preequilibrated Talon metal affinity resin, incubated for 1 h on ice, and washed twice with 5 to 10 ml of guanidinium-HCl buffer. The hexahistidine-tagged mutant SPases were eluted with 5 ml of lysis buffer containing 0.5 M imidazole at pH 8.0. Aliquots were stored at −80°C in the presence of 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. Protein purification was monitored by SDS-PAGE and subsequent staining of the gels with CBB.

N-terminal protein sequencing.

Purified sf-SipS-His (Bam) was incubated overnight at 37°C in buffer containing 50 mM glycine (pH 10). Intact sf-SipS-His (Bam) and its apparent degradation products d1 and d2 were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) by semi dry electroblotting as described in reference 8. Protein bands on the membrane were visualized by CBB staining. Next, the three major bands were excised, and the first seven residues of the corresponding proteins were determined by automated Edman degradation (Eurosequence).

RESULTS

Degradation of sf-SipS-His (Bam).

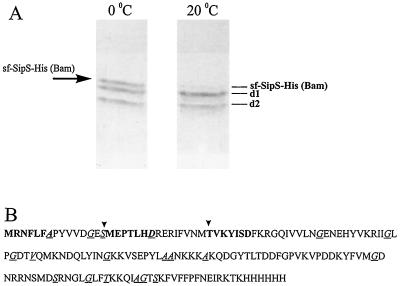

Our previous unpublished studies indicated that sf-SipS-His (Bam) is prone to proteolytic degradation, apparently resulting in two major degradation products (d1 and d2) that are copurified with intact sf-SipS-His (Bam) upon metal affinity chromatography (Fig. 2A). To obtain insight in the mechanism of sf-SipS-His (Bam) degradation, the proteins obtained after purification were incubated in 50 mM glycine buffer (pH 10) for various periods of time and at different temperatures. At pH 10, sf-SipS-His (Bam) shows optimal SPase activity (data not shown). A typical result of such an incubation (Fig. 2A) shows that overnight incubation at 20°C, compared to 0°C, resulted in a strong decrease of intact sf-SipS-His (Bam) and a concomitant increase of degradation product d1. Similarly, sf-SipS-His (Bam) was degraded at 37°C, leading to a concomitant increase of degradation product d1. These degradation events were not inhibited by the presence of protease inhibitors such as EDTA, phosphoramidon, or PMSF (data not shown). In contrast, the amount of degradation product d2 was not visibly affected by incubation at 20°C (Fig. 2A) or other temperatures (data not shown). Notably, upon incubation at 0°C (Fig. 2A) or at pH 5, a pH at which sf-SipS-His (Bam) is almost completely inactive, the relative amounts of sf-SipS-His (Bam) and the degradation products d1 and d2 did not change (data not shown). These observations suggested that the degradation of sf-SipS-His (Bam) was, at least in part, due to autodigestion.

FIG. 2.

Degradation of sf-SipS-His (Bam). (A) Purified sf-SipS-His (Bam) and copurified degradation products were incubated overnight at 0 and 20°C in 50 mM glycine buffer (pH 10) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequent CBB staining. Bands corresponding to degradation products of sf-SipS-His (Bam) are indicated as d1 and d2. (B) Amino acid sequence of sf-SipS-His (Bam). Sites of degradation, identified by automated Edman degradation, are marked with arrows. The −1 residues of potential SPase Ala-X-Ala recognition sequences (based on reference 25) are indicated in italics and underlined. Residues indicated in bold were identified by N-terminal sequencing.

To further investigate this possibility, metal affinity-purified sf-SipS-His (Bam)-specific polypeptides were incubated overnight (pH 10; 37°C), separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Next, the bands corresponding to intact sf-SipS-His (Bam), d1, and d2 (for positions, see Fig. 2A) were subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequencing. The results of the sequence analysis are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2B.

TABLE 3.

N-terminal sequencing of sf-SipS-His (Bam) and its major degradation products d1 and d2

| Construct | % in bandsa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MRNFLFA | MEPTLHD | TVKYISD | |

| sf-SipS-His (Bam) | 100 | ||

| d1 | 71 | 29 | |

| d2 | 10 | 90 | |

N-terminal amino acid sequences of polypeptides corresponding to sf-SipS-His (Bam) and its major degradation products, identified as bands d1 and d2 upon SDS-PAGE, were determined by automated Edman degradation. Sequencing of bands d1 and d2 showed that each of these represented a mixture of different polypeptides with the same mobility on SDS-PAGE. The relative amounts of polypeptides starting with the sequence MRNFLFA, MEPTLHD, or TVKYISD in the bands that were used for sequencing are indicated.

First, the data confirm that the band predicted to correspond to the intact sf-SipS-His (Bam) was indeed sf-SipS-His (Bam), as all proteins migrating in this band started with the sequence MRNFLFA. Second, bands d1 and d2 were shown to consist of proteins derived from sf-SipS-His (Bam). Third, cleavage of sf-SipS-His (Bam) was shown to occur between residues Ser15 and Met16 and between residues Met30 and Thr31 (Fig. 2B). In addition, the results indicate that sf-SipS-His (Bam) was cleaved C terminally, as band d1 in the polypeptide mixture obtained after self-incubation contained not only polypeptides starting with the sequence MEPTLHD (derived from cleavage between Ser15 and Met16) but also polypeptides starting with the N terminus of sf-SipS-His (Bam) (i.e., MRNFLFA). In fact, our results indicate that about 70% of the polypeptides in band d1 were cleaved C terminally (Table 3). Similarly, band d2 contained both molecules starting with the sequence TVKYISD (derived from cleavage between Met30 and Thr31; about 90%) and the N terminus of sf-SipS-His (Bam) (about 10%). These observations indicate that C-terminal cleavage of sf-SipS-His (Bam) had occurred in at least two distinct sites. Strikingly, the residues located N terminally of Met16 strongly resembled a typical SPase I recognition site, Gly13 and Ser15, conforming to the −1, −3 rule (25, 26). Taken together, these observations indicate that the cleavage between residues Ser15 and Met16 of sf-SipS-His (Bam) is due to autodigestion. In contrast, the residues located N terminally of Thr31 do not resemble those of an SPase I recognition site, suggesting that the cleavage between Met30 and Thr31 is not due to autodigestion but mediated by cytosolic proteases of E. coli. Furthermore, as the molecules analyzed were isolated on the basis of their C-terminal hexahistidine tag, our results imply that the C-terminal cleavage was due to autodigestion.

High-level production of inactive soluble SPases.

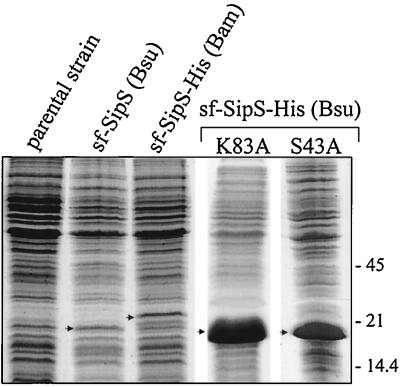

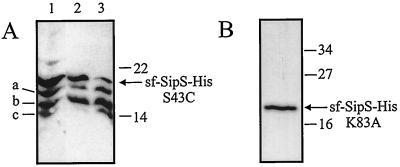

To verify the idea that the degradation of soluble Bacillus SPases is, at least in part, a process of self-cleavage, soluble SipS mutant proteins with low or no catalytic activity were constructed (Fig. 1B). For this purpose, the active-site Ser and Lys residues (corresponding to Ser43 and Lys83 in the wild-type SipS of B. subtilis) of the truncated sf-SipS-His (Bsu) were replaced by Ala residues. In the wild-type enzyme, the equivalent mutations resulted in complete inactivity (23). Alternatively, the active-site Ser residue of sf-SipS-His (Bsu) was replaced with Cys, which resulted in strongly reduced SPase activity of the wild-type enzyme (23). Next, the mutant sf-sipS-His (Bsu) genes were placed downstream of the T7 promoter of pGEF+ (14). The resulting constructs, named pGEFdSH-S43A, -S43C, and -K83A, respectively (Fig. 1B), were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3). Unexpectedly, even in the absence of IPTG, the presence of pGEFdSH-S43A or pGEFdSH-K83A in E. coli BL21(DE3) resulted in the formation of inclusion bodies that could be readily observed by phase-contrast microscopy (data not shown). This observation indicates that synthesis of the T7 RNA polymerase in E. coli BL21(DE3) was not completely repressed in the absence of IPTG. As shown in Fig. 3, upon IPTG induction, the sf-SipS-His S43A and K83A proteins were overproduced to very high levels. In contrast, E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pGEFdSH-S43C did not form inclusion bodies, even if T7-dependent transcription of the sf-sipS-His S43C (Bsu) gene was induced with IPTG. In fact, upon induction with IPTG, the sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) protein was produced to levels (data not shown) comparable to the production levels of sf-SipS (Bsu) and sf-SipS-His (Bam) (Fig. 3). As shown by Western blotting (Fig. 4A), at least three degradation products of sf-SipS-His S43C were formed upon IPTG induction. All three degradation products contained the His-tagged carboxyl terminus, as evidenced by their binding to the Talon metal affinity resin (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 3.

Overproduction of truncated soluble forms of SipS. Cells of E. coli BL21(DE3), transformed with plasmid pT7dS, pT7dAH, pGEFdSH-K83A, or pGEFdSH-S43A, were grown in TY medium. The overproduction of sf-SipS (Bsu), sf-SipS-His (Bam), sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu), and sf-SipS-His S43A (Bsu), respectively, was induced with IPTG as described in Materials and Methods. Cells containing the empty vector (pT712) were used as a negative control (parental strain). Samples of cells, collected 3 h after induction with IPTG, were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with CBB. Arrows indicate positions of the overproduced truncated SPases. The positions of molecular mass reference markers are indicated in kilodaltons.

FIG. 4.

Different stabilities of sf-SipS-His S43C and K83A (Bsu). (A) E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with plasmid pGEFdSH-S43C was grown in TY medium, and the production of sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) was induced with IPTG. Cells were collected 3 h after induction, and disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell. Samples of the disrupted cells were subject to metal affinity chromatography, and fractions were analyzed for the presence of sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) and its degradation products (a, b, and c) by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and immunodetection with specific antibodies. Note that sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu) and its degradation products a, b, and c have different affinities for the metal affinity resin, as evidenced by their elution at different imidazole concentrations. Lane 1, cytoplasmic fraction of IPTG-induced cells; lanes 2 and 3, fractions obtained upon elution with buffer containing increasing concentrations of imidazole. The positions of sf-SipS-His S43C (Bsu), its degradation products (a, b, and c), and molecular mass reference markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated. (B) Sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu), as purified from inclusion bodies that were isolated from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pGEFdSH-K83A. Purified sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequent CBB staining. The positions of molecular mass reference markers are indicated in kilodalton.

Upon IPTG-induced overproduction, the sf-SipS-His S43A and K83A proteins accumulated in very large inclusion bodies, allowing the rapid purification of these proteins by metal affinity chromatography. As shown for sf-SipS-His K83A (Fig. 4B), degradation products as identified with the active truncated SPase (Fig. 2A) or sf-SipS-His S43C (Fig. 4A) were absent from these preparations. Furthermore, even after prolonged incubation of the purified sf-SipS-His K83A (Bsu) at 37°C, no breakdown products were detectable (data not shown). These results show that the catalytically inactive soluble forms of SipS are not, or are only to levels below detection, prone to degradation. Taken together, our observations imply that self-cleavage is the primary cause for the low levels of production of catalytically active soluble forms of SipS in E. coli.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that soluble forms of catalytically active SipS derivatives are, to a large extent, subject to self-cleavage. First, only catalytically inactive soluble forms of SipS could be overproduced to high levels, and only with the inactive forms were degradation products undetectable. Second, catalytically active soluble forms of SipS, purified on the basis of their C-terminal hexahistidine tag, were prone to N- and C-terminal cleavage upon incubation under conditions suitable for SPase activity. This cleavage was not observed upon incubation at pH 5 or 0°C, both of which are conditions preventing SPase activity. Also, consistent with the fact that type I SPases in general (4) and the type I SPases of B. subtilis in particular (24) are not sensitive to typical protease inhibitors, the in vitro degradation of SipS was not inhibited by EDTA phosphoramidon or PMSF. Third, the region located N terminally of at least one of the identified cleavage sites (between Ser15 and Met16) strongly resembled a typical SPase recognition site, conforming to the −1,−3 rule (25, 26). Finally, in addition to the cleavage site between Ser15 and Met16, numerous potential SPase cleavage sites are present in sf-SipS-His (Bam) (Fig. 2B), some of which may account for the observed C-terminal cleavage. Taken together, these observations indicate that the primary degradation steps of soluble forms of SipS are self-cleavage events in the cytoplasm of E. coli, the host organism for the production of these proteins. Notably, the purified SPase of E. coli (Lep) was also subject to autodigestion, but self-cleavage of this enzyme occurred largely at one site that was located between the two N-terminal membrane anchors, thereby not inactivating the enzyme (17).

In addition to autodigestion, active soluble forms of SipS also seem to be subject to degradation by one or more cytosolic proteases of E. coli. First, as shown for sf-SipS-His (Bam), cleavage occurred at a site (i.e., between Met30 and Thr31) that did not resemble typical SPase cleavage sites. Second, no further cleavage between Met30 and Thr31 was observed upon incubation of sf-SipS-His (Bam) under conditions optimal for SPase activity. As no degradation of catalytically inactive soluble forms of SipS was detected, it seems that the degradation by cytosolic proteases can occur only upon a first autodigestion event. Such an autodigestion event could be required to expose certain protease cleavage sites in SipS or to destabilize the folded protein.

Strikingly, the presumed self-cleavage between Ser15 and Met16 disrupts the catalytic site of sf-SipS-His (Bam), Ser15 being equivalent to the active-site Ser residue of intact SipS. Thus, one of the major degradation events described here results in the inactivation of sf-SipS-His (Bam). Unfortunately, this problem could not be solved by changing Met16 to Pro, as the M44P mutation in SipS (Bsu) resulted in the complete loss of SPase activity (data not shown). The rationale of the latter experiment was that Pro residues at the +1 position relative to an SPase cleavage site have a very strong inhibiting effect on SPase activity (1, 10). The potential alternative solution of changing residues at the −1 position (i.e., the active-site Ser residue) or the −3 position (i.e., Gly13), also is not an option to solve this problem, as these residues are critical for SPase activity (23). Thus, it seems that solutions for the overproduction of catalytically active soluble forms of SipS must be sought in alternative strategies. For example, the temperature-sensitive SipS mutant proteins L74A and Y81A, which are structurally stable but catalytically inactive at 48°C (3), could be used for this purpose in future studies.

Finally, the unique membrane anchor of SipS seems to protect the enzyme against autoproteolytic and other degradation events, as the intact hexahistidine-tagged SipS (Bam) could be overproduced to very high levels. Moreover, the purified enzyme appeared to be relatively resistant to autodigestion (our unpublished observations). At present, we do not know how the membrane anchor prevents degradation. However, one might speculate that it limits the possibilities for interactions between different SipS molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Schanstra for kindly providing plasmid pGEF+ and A. Bolhuis, H. Tjalsma, and other members of the European Bacillus Secretion Group for stimulating discussions.

M.L.V.R. was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs through ABON (Associatie Biologische Onderzoeksscholen Nederland); J.D.H.J. was supported by grant 805-33.605 from SLW (Stichting Levenswetenschappen); and A.K., S.B and J.M.V.D. were supported by grants Bio2-CT93-0254, Bio4-CT96-0097, QLK3-CT-1999-00415, and QLK3-CT-1999-00917 from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkocy-Gallagher G A, Bassford P J J. Synthesis of precursor maltose-binding protein with proline in the +1 position of the cleavage site interferes with the activity of Escherichia coli signal peptidase I in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolhuis A, Sorokin A, Azevedo V, Ehrlich S D, Braun P G, de Jong A, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. Bacillus subtilis can modulate its capacity and specificity for protein secretion through temporally controlled expression of the sipS gene for signal peptidase I. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:605–618. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-4676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolhuis A, Tjalsma H, Stephenson K, Harwood C R, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. Different mechanisms for thermal inactivation of Bacillus subtilis signal peptidase mutants. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15865–15868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalbey R E, Lively M O, Bron S, van Dijl J M. The chemistry and enzymology of the type I signal peptidases. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1129–1138. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fikes J D, Barkocy-Gallagher G A, Klapper D G, Bassford P J J. Maturation of Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein by signal peptidase I in vivo. Sequence requirements for efficient processing and demonstration of an alternate cleavage site. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3417–3423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folz R J, Nothwehr S F, Gordon J I. Substrate specificity of eukaryotic signal peptidase. Site-saturation mutagenesis at position −1 regulates cleavage between multiple sites in human pre (delta pro) apolipoprotein A-II. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2070–2078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessières P, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyhse-Andersen J. Electroblotting of multiple gels: a simple apparatus without buffer tank for rapid transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide to nitrocellulose. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984;10:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer W J J, de Jong A, Wisman G B A, Tjalsma H, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. The endogenous Bacillus subtilis (natto) plasmids pTA1015 and pTA1040 contain signal peptidase-encoding genes: identification of a new structural module on cryptic plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:621–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17040621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilsson I, von Heijne G. A signal peptide with a proline next to the cleavage site inhibits leader peptidase when present in a sec-independent protein. FEBS Lett. 1992;299:243–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paetzel M, Dalbey R E, Strynadka N-C J. Crystal structure of a bacterial signal peptidase in complex with a beta-lactam inhibitor. Nature. 1998;396:186–190. doi: 10.1038/24196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schanstra J P, Rink R, Pries F, Janssen D B. Construction of an expression and site-directed mutagenesis system of haloalkane dehalogenase in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1993;4:479–489. doi: 10.1006/prep.1993.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen L M, Lee J I, Cheng S, Kuhn H-J A, Dalbey R E. Use of site-directed mutagenesis to define the limits of sequence variation tolerated for processing of the M13 procoat protein by the Escherichia coli leader peptidase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11775–11781. doi: 10.1021/bi00115a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;6:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talarico T L, Dev I K, Bassford P J, Jr, Ray P H. Inter-molecular degradation of signal peptidase I in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181:650–656. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91240-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjalsma H, Bolhuis A, van Roosmalen M L, Wiegert T, Schumann W, Broekhuizen C P, Quax W J, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. Functional analysis of the secretory precursor processing machinery of Bacillus subtilis: identification of a eubacterial homolog of archaeal and eukaryotic signal peptidases. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2318–2331. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjalsma H, Noback M A, Bron S, Venema G, Yamane K, van Dijl J M. Bacillus subtilis contains four closely related type I signal peptidases with overlapping substrate specificities. Constitutive and temporally controlled expression of different sip genes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25983–25992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tjalsma H, van den Dolder J, Meijer W J J, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. The plasmid-encoded signal peptidase SipP can functionally replace the major signal peptidases SipS and SipT of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2448–2454. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2448-2454.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dijl J M, de Jong A, Vehmaanperä J, Venema G, Bron S. Signal peptidase I of Bacillus subtilis: patterns of conserved amino acids in prokaryotic and eukaryotic type I signal peptidases. EMBO J. 1992;11:2819–2828. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dijl J M, de Jong A, Venema G, Bron S. Identification of the potential active site of the signal peptidase SipS of Bacillus subtilis: structural and functional similarities with LexA-like proteases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3611–3618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vehmaanperä J, Görner A, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. In vitro assay for the Bacillus subtilis signal peptidase SipS: systems for efficient in vitro transcription-translation and processing of precursors of secreted proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Heijne G. Patterns of amino acids near signal-sequence cleavage sites. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Heijne G. How signal sequences maintain cleavage specificity. J Mol Biol. 1984;173:243–251. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Heijne G. Signal sequences. The limits of variation. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Heijne G. Sec-independent protein insertion into the inner E. coli membrane. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Heijne G. Getting greasy: how transmembrane polypeptide segments integrate into the lipid bilayer. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:249–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3351702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh K M, Trach K A, Folger C, Hoch J A. Biochemical characterization of the essential GTP-binding protein Obg of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7161–7168. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7161-7168.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wertman K F, Wyman A R, Botstein D. Host/vector interactions which affect the viability of recombinant phage lambda clones. Gene. 1986;49:253–262. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]