Summary

Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) syndrome is a rare genetic condition associated with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. Preclinical evidence suggests that low-dose ketamine may induce expression of ADNP and that neuroprotective effects of ketamine may be mediated by ADNP. The goal of the proposed research was to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and behavioral outcomes of low-dose ketamine in children with ADNP syndrome. We also sought to explore the feasibility of using electrophysiological markers of auditory steady-state response and computerized eye tracking to assess biomarker sensitivity to treatment. This study utilized a single-dose (0.5 mg/kg), open-label design, with ketamine infused intravenously over 40 min. Ten children with ADNP syndrome ages 6 to 12 years were enrolled. Ketamine was generally well tolerated, and there were no serious adverse events. The most common adverse events were elation/silliness (50%), fatigue (40%), and increased aggression (40%). Using parent-report instruments to assess treatment effects, ketamine was associated with nominally significant improvement in a wide array of domains, including social behavior, attention deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and sensory sensitivities, a week after administration. Results derived from clinician-rated assessments aligned with findings from the parent reports. Overall, nominal improvement was evident based on the Clinical Global Impressions - Improvement scale, in addition to clinician-based scales reflecting key domains of social communication, attention deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, speech, thinking, and learning, activities of daily living, and sensory sensitivities. Results also highlight the potential utility of electrophysiological measurement of auditory steady-state response and eye-tracking to index change with ketamine treatment. Findings are intended to be hypothesis generating and provide preliminary support for the safety and efficacy of ketamine in ADNP syndrome in addition to identifying useful endpoints for a ketamine clinical development program. However, results must be interpreted with caution given limitations of this study, most importantly the small sample size and absence of a placebo-control group.

Keywords: Helsmoortel-Van der Aa syndrome, ADNP, ketamine, autism spectrum disorder, ASD

Introduction

Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) syndrome (MIM: 615873) is a rare condition but a leading genetic cause of intellectual disability (ID) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).1, 2, 3 Common features include aberrant behavior, language delays, attention deficit and hyperactivity, sensory seeking behavior, anxiety, and sleep disturbance.2,4, 5, 6 Other phenotypic features are varied and may include gastrointestinal problems, endocrine and growth problems, hypotonia, gait abnormalities, and visual abnormalities.2,5 ADNP syndrome is caused by de novo pathogenic variants in the ADNP gene, leading to haploinsufficiency.2 Over 400 genes are regulated by ADNP, which play critical roles in brain formation and other organ development.7, 8, 9 ADNP haploinsufficiency alters neurodevelopment and ADNP-deficient mice show reduced dendritic spine density, spatial learning deficits, memory impairment, muscle weakness, and communication problems.10,11

Advances in understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of ADNP syndrome have created important opportunities for developing novel and potentially disease modifying therapeutics. Using the artificial intelligence software mediKanren,12 preclinical evidence demonstrating ADNP induction by ketamine was uncovered and provided an opportunity to examine the therapeutic effect of low-dose ketamine in children with ADNP syndrome.13,14

Ketamine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that disrupts calcium homeostasis in neurons15,16 and is widely used for anesthesia. Recently, low-dose ketamine was demonstrated to be efficacious as an adjunctive therapy in adults with treatment-resistant depression17, 18, 19 indicating therapeutic potential beyond conventional use. In pediatric populations, ketamine is reported to have both neuroprotective and neurotoxic effects.20 High-dose ketamine is believed to cause neurotoxicity by induction of neuronal apoptosis. However, low-dose ketamine is extensively used for sedation and analgesia in pediatric patients with an acceptable safety profile.21 Studies in juvenile rats demonstrated that neurotoxic effects of high-dose ketamine can be prevented by pretreatment with the ADNP fragment neuroprotective activity peptide (NAP) in a dose-dependent manner as well as by pretreatment with low-dose ketamine.22 Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo treatment with low-dose ketamine showed dose-dependent induction of ADNP in rat neurons suggesting that neuroprotective effects of low-dose ketamine may be, at least in part, mediated by ADNP.13 Interestingly, this mechanism also appears to be at play in colon cancer models where ketamine-induced overexpression of ADNP acted as a repressor of WNT signaling, inhibited tumor growth, and prolonged survival.14 This result was further corroborated by an association between higher expression levels of ADNP in tumor biopsies from individuals with colon cancer and favorable prognosis. Based on the potential of low-dose ketamine to induce ADNP overexpression, we hypothesized that treatment with low-dose ketamine would have a beneficial effect in individuals with ADNP syndrome by compensating for ADNP haploinsufficiency.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and behavioral outcomes of low-dose ketamine in children with ADNP syndrome. In addition, we sought to explore the feasibility of objective biological markers using electrophysiological measurement of auditory steady-state response (ASSR) and computerized eye-tracking in order to assess sensitivity to change with treatment. ASSR has been shown to index the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neural systems modulated by GABAergic and glutamatergic activity,23, 24, 25 and it is an especially compelling potential biomarker given the mechanism of action of ketamine and findings that ADNP haploinsufficiency may affect glutamatergic neurotransmission.26

Subjects and methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects, and all caregivers signed informed consent. The informed consent procedure included extensive discussion of potential risks of ketamine, including sedation, headache, nausea, elevated blood pressure and heart rate, and perceptual disturbances.27 While this study involved only a single dose, caregivers were also informed that repeated ketamine use has been associated with structural and functional brain changes,28 cognitive problems, and increased inflammatory cytokines.29 Ten participants were screened, and all met criteria for inclusion and were enrolled between August 2020 and May 2021. For inclusion, participants had to be 5–12 years old at the time of informed consent and have a diagnosis of ADNP syndrome confirmed by molecular genetic testing. All participants were required to have a Clinical Global Impression-Severity score of four (moderately ill) or greater at screening. Concomitant medication, including anti-epileptic and/or behavioral medications, and supplements were at a stable dose for at least 4 weeks before enrollment.

Medical history and physical health were assessed through physical examination and laboratory-based assessments, including electrocardiography (ECG), urinalysis, and blood sampling for hematology and chemistry. All participants were assessed for ASD using gold-standard instruments, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),30 the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2),31 and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).32 In addition, all participants were evaluated for psychiatric disorders using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and the Anxiety, Depression, and Mood Scale (ADAMS).33 Intellectual functioning was assessed using age- and developmental level-appropriate standardized measures; developmental quotients were calculated as previously described in the literature.34 Adaptive functioning was measured with the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third Edition (Vineland-3)35 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Demographic categories | Proportion or mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Total N | 10 | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 3/10 | |

| Male | 7/10 | |

| Age: years | 9.50 (2.30) | 6.35–12.85 |

| Developmental quotient | ||

| VDQ | 26.71 (15.33) | 5.65–52.48 |

| NVDQ | 31.28 (16.13) | 8.87–58.42 |

| FSDQ | 28.81 (15.42) | 7.26–54.5 |

| ASD | 4/10 | |

| ADHD | 7/10 | |

| Genetic mutation | ||

| Frameshift | 6/10 | |

| Nonsense | 4/10 | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2/10 | |

| White | 8/10 | |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FSDQ: full scale developmental quotient; NVDQ: nonverbal developmental quotient; VDQ: verbal developmental quotient.

Study design

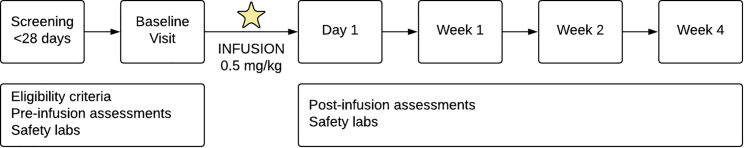

This study utilized a single-dose (0.5 mg/kg), open-label design to investigate the safety, tolerability, and behavioral outcomes of treatment with low-dose ketamine in ten children with ADNP syndrome. The study was comprised of the following: (1) screening period within the 4 weeks preceding a baseline visit; (2) baseline visit for assessments followed by administration of study drug; (3) clinic visits for safety, clinical outcome, and biomarker assessments at day 1, week 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 1). Results were intended to inform ketamine clinical development, endpoints, and the design of future and larger studies in ADNP syndrome.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of study design

The six study visits are outlined.

Study visits

Assessment of safety

All participants were evaluated for drug safety and tolerability using physical examination, laboratory assessments, and vital signs that were monitored throughout the infusion and at all clinic visits. Monitoring for adverse events (AEs) was conducted during all clinic visits using the Systematic Longitudinal Adverse Events Scale (SLAES).36

Assessment of efficacy

Clinical outcome assessments and exploratory measures were collected at baseline, day 1, and weeks 1, 2, and 4. Outcome assessments were selected to measure ADNP core symptom domains and included (1) parent-rated instruments, (2) clinician-rated instruments, and (3) objective assessments.

-

a.

Parent-rated questionnaires: (1) Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC),37 (2) Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R),38 (3) Sensory Profile,39 (4) ADAMS,33 (5) Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ),40 (6) Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CGSQ),41 (7) Conners 3rd Edition (Conners)42.

-

b.

Clinician-rated measures: (1) Clinical Global Impression Scale for ADNP syndrome (severity and improvement; CGI-S and CGI-I),43 (2) ADNP Syndrome Specific Concerns Visual Analog Scale (Figure S1), (3) Vineland-3,35 (4) Sensory Assessment for Neurodevelopmental Disorders (SAND),44 (5) the Beery Visual-Motor Integration, Sixth Edition (VMI-6)45; (6) Expressive Vocabulary Test, Third Edition (EVT-3),46 (7) Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fifth Edition (PPVT-5),47 and (8) SLAES.

-

c.

Objective measures: (1) computerized eye tracking and (2) ASSR.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

EEG data were recorded at 128 electrode sites using Hydrocel Geodesic Sensor Nets and EGI Magstim NetStation Software version 5.4.2. Participants were seated in a dark, quiet room and watched a silent video of their choice during data acquisition. Auditory steady-state stimuli were presented through Presentation software and delivered through a speaker or through Etymotic headphones, depending on participant tolerance. In separate blocks, participants heard a 500-ms click at either a stimulation rate of 40 or 20 Hz. Click trains were presented 150 times each, with an intertrial interval of 50 ms, at approximately 60 db. All data cleaning was conducted using NetStation tools. Data were filtered using 0.50 high-pass and 60 Hz notch filters. Data were then referenced to the average of all electrodes, and segments were created extending 250 ms before and 750 ms after the stimulus. Data were cleaned using artifact detection; segments were marked as bad if they contained more than 10% bad channels (>200 μv), if they contained an eyeblink (>140 μv), or if they contained eye movement (>55 μv). Channels were marked as bad if greater than 20% of segments were marked as bad. Channels were marked as bad for all segments if bad for greater than 20% of segments, and they were replaced using bad channel replacement tools. Wavelets were created for frequencies between 10 and 50 Hz, and time-frequency analysis was conducted in MATLAB to extract intertrial phase coherence (ITC) at 20 and 40 Hz. ITC is a value between 0 and 1, where 0 reflects a random distribution of phase angles, and 1 reflects absolute neural synchrony.

Computerized eye tracking

Eye tracking data were captured via EyeLink 1000 plus eye tracker in a dark, quiet room using head-free mode. Participants were seated approximately 50 cm from the monitor and eye tracker, and each participant completed a 13-point calibration prior to the start of the task. A Joint Attention task was utilized to measure attention.

Joint Attention

A series of 12 pseudo-randomized trials were presented during which a video displays a woman seated at the center of the frame, first looking down for 5 s, and then looking up and turning her head to direct attention using eye gaze at either an object on the lower right or lower left of the screen for 10 s. Average latency to saccade to the target object, proportion of trials where the target item is looked at before the distractor, and average proportion of time spent dwelling on the target (versus distractor) were calculated.48

Study drug administration

Racemic ketamine hydrochloride was administered intravenously (IV) with an infusion pump at 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min. Dosing was based on clinical guidelines in children,49 adults with major depressive disorder50 and posttraumatic stress disorder,51 and review of the safety literature.52,53 Dosing followed a pre-fixed paradigm according to participants’ weight. The drug substance is commercially available and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an anesthetic for children in the proposed age range; an investigational new drug (IND) application was approved by the FDA for this study (IND 147201). All preparation and packaging were performed in the Mount Sinai Research Pharmacy. An indwelling catheter was placed, and pulse, blood pressure, pulse-oximetry, and an ECG strip were used for continuous monitoring. A pediatric anesthesiologist (RL) was present throughout the administration of ketamine and during the recovery period so that potential AEs could be evaluated and treated promptly. Following the infusion protocol, the participant was monitored for at least 1 hour. After a physical examination and check of vital signs, the participant was discharged.

Data analysis

Demographic data and baseline characteristics are presented using descriptive statistics (Table 1). Treatment emergent AE data are summarized as frequencies and percentages (Table 2). To examine treatment effects, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests assessed the differences in data distributions (change over time) from baseline to week 1, week 2, and to week 4. However, our primary analysis was to test differences between baseline and week 1. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a non-parametric test and does not require the data to follow a particular distribution; it is robust to single gross outliers and has higher power than a t test, unless the data follow exactly a Gaussian distribution, and then the power is very close.54

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Adverse event type | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Elated/silly | 5 (50) |

| Aggression | 4 (40) |

| Fatigue | 4 (40) |

| Decreased appetite | 3 (30) |

| Anxiety | 3 (30) |

| Increased appetite | 2 (20) |

| Restless | 2 (20) |

| Increased fluid intake | 2 (20) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (20) |

| Moody/irritable | 2 (20) |

| Dry mouth | 2 (20) |

| Gagging/reflux | 1 (10) |

| Self-injury | 1 (10) |

| Loose stool | 1 (10) |

| Difficulty falling asleep | 1 (10) |

| Early morning wakening | 1 (10) |

| Limping with possible pain | 1(10) |

| Decreased fluid intake | 1 (10) |

| Distractibility | 1 (10) |

| Constipation | 1 (10) |

| Increased frustration | 1 (10) |

| Oppositional | 1 (10) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (10) |

| Agitation | 1 (10) |

All tests of statistical hypotheses were on the two-sided 5% level of significance and presented together with the associated point estimate and two-sided 95% confidence interval. Since this was an initial proof-of-concept study to evaluate safety and identify potential endpoints for larger controlled trials, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. If we were to apply methods to address multiplicity (e.g., using Bonferroni-Holm),55 none of the results would reach statistical significance. SPSS was used to perform statistical analyses.

Sample size and statistical power

The sample size was not based on statistical criteria but determined by what was pragmatic and achievable for this pilot study given that ADNP syndrome is a rare disease. However, power estimates were based on a sample size of 10 individuals using baseline to week 1 change scores. Our type I error rate (α) was set at .05 and with adequate power to detect large effects in the within-subject analysis based on the key outcome measure of efficacy, the Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement Scale. A large effect size was deemed feasible based on the potentially disease modifying effects of ketamine in ADNP syndrome. However, our primary aim was to evaluate safety and then to detect signal of improvement.

Results

Participants ranged in age from 6 to 12 years old (mean = 9.50; SD = 2.30) and were predominantly male (7:3) (Table 1). Ketamine was generally well tolerated, and treatment emergent AEs were all mild to moderate, and no participant required any interventions. During infusions, no AEs were observed except for nausea and vomiting in one participant with a history of vomiting. The most common AEs were elation/silliness in five participants (50%), all of whom had a history of similar symptoms. Drowsiness and fatigue were present in four participants (40%), and two of the four had a history of drowsiness. Aggression was likewise relatively commonly reported (40%) but present in all affected participants at baseline. Decreased appetite emerged as a new AE for three participants (30%), increased anxiety occurred in three (30%), and irritability, nausea/vomiting, and restlessness each occurred in two participants (20%) (Table 2). There were no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory or cardiac monitoring, and there were no serious AEs.

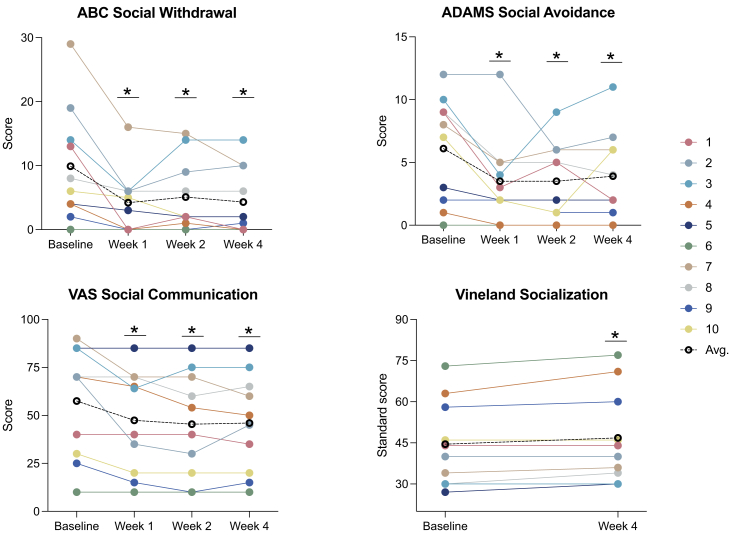

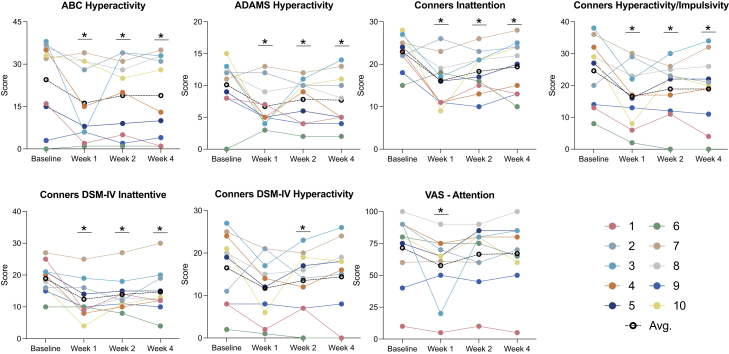

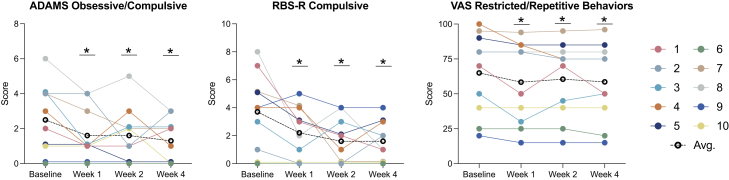

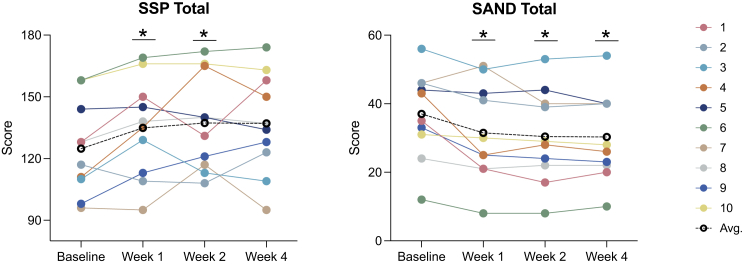

Ketamine was associated with nominally significant improvement on several important measures. Here we use “nominally” because we are not accounting for multiple statistical testing. In our primary analysis examining treatment effects at week 1, the main caregiver-rated instruments (Table 3) showed that ketamine was associated with nominally significant improvement in a wide array of domains and across multiple measures, including social (ABC, ADAMS) (Figure 2), ADHD symptoms (ABC, ADAMS, Conners) (Figure 3), restricted and repetitive behaviors (ADAMS, RBS-R) (Figure 4), and sensory reactivity (SSP) (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Caregiver-rated assessments

| Assessment tool | Domain | Mean (SD) |

Week 1 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| ABC | Irritability | 20.5 (13.33) | 10.9 (10.6) | 0.015∗ |

| Social withdrawal | 9.9 (8.96) | 4.2 (4.96) | 0.007∗ | |

| Motor stereotypies | 7.8 (5.31) | 4.5 (3.66) | 0.007∗ | |

| Hyperactivity | 24.5 (14.66) | 16.2 (13.35) | 0.041∗ | |

| Inappropriate speech | 3.6 (2.88) | 3.3 (2.21) | 0.61 | |

| ADAMS | Hyperactivity | 10.1 (4.23) | 6.7 (3.5) | 0.05∗ |

| Depressed | 2.6 (3.31) | 2.1 (2.69) | 0.35 | |

| Social avoidance | 6.1 (4.23) | 3.5 (3.47) | 0.018∗ | |

| General anxiety | 6.3 (5.96) | 4.3 (4.74) | 0.06 | |

| Obsessive/compulsive | 2.5 (2.01) | 1.6 (1.51) | 0.041∗ | |

| RBS-R | Stereotyped | 6.6 (3.31) | 5.1 (4.93) | 0.14 |

| Self-injury | 5.9 (4.79) | 4.2 (3.49) | 0.17 | |

| Compulsive | 3.7 (2.75) | 2.2 (1.87) | 0.041∗ | |

| Ritualistic | 2.9 (3.63) | 2.9 (2.38) | 0.78 | |

| Sameness | 5.6 (6.33) | 4.3 (5.46) | 0.27 | |

| Restricted | 3.9 (3.14) | 3.6 (2.37) | 0.67 | |

| Overall | 28.6 (17.56) | 22.3 (14.28) | 0.21 | |

| CSHQ | Total | 2.83 (0.75) | 2.93 (0.82) | 0.48 |

| SSP | Tactile sensitivity | 26.7 (5.96) | 29.7 (4.14) | 0.02∗ |

| Taste smell | 13.9 (5.57) | 13.5 (6.7) | 0.89 | |

| Movement | 11 (3.4) | 11.2 (4.37) | 0.72 | |

| Under-responsive | 18.4 (4.95) | 21.1 (5.26) | 0.06 | |

| Auditory filtering | 18.7 (5.7) | 20.9 (4.2) | 0.091 | |

| Low energy/weak | 17.5 (5.66) | 19 (6.06) | 0.33 | |

| Visual/auditory | 18.6 (3.2) | 19.5 (3.81) | 0.23 | |

| SSP total | 124.8 (22.64) | 134.9 (24.15) | 0.022∗ | |

| CGSQ | Objective strain | 2.79 (1.11) | 2.45 (0.99) | 0.10 |

| Subjective externalized strain | 2.18 (1.11) | 1.62 (0.69) | 0.046∗ | |

| Subjective internalized strain | 3.3 (1.15) | 2.7 (0.97) | 0.10 | |

| Global score | 8.27 (3.08) | 6.77 (2.32) | 0.06 | |

| Conners | Inattention | 22.9 (3.96) | 16.1 (5.65) | 0.022∗ |

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity | 24.6 (10.29) | 16.6 (9.52) | 0.028∗ | |

| Learning problems | 17.1 (5.99) | 16.7 (6.52) | 0.951 | |

| Executive functioning | 13.7 (4.27) | 10.6 (5.36) | 0.082 | |

| Defiance/aggression | 7.5 (4.74) | 4.4 (3.06) | 0.123 | |

| Peer relations | 10.5 (5.13) | 8.8 (4.49) | 0.341 | |

| Conners 3 Global Index | 19.2 (7.55) | 13.2 (7.27) | 0.038∗ | |

| DSM-IV-TR ADHD Inattentive | 18.9 (5) | 12.4 (6.17) | 0.012∗ | |

| DSM-IV-TR ADHD Hyperactive-Impulsive | 16.5 (8.58) | 11.7 (7.24) | 0.065 | |

| DSM-IV-TR Conduct Disorder | 4.2 (3.39) | 2.8 (2.1) | 0.436 | |

| DSM-IV-TR Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 6.9 (4.89) | 4.2 (3.65) | 0.074 | |

| Positive impression | 3.8 (1.14) | 3.8 (1.48) | 0.739 | |

| Negative impression | 1.9 (1.97) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.34 |

Abbreviations: ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADAMS: Anxiety, Depression and Mood Scales; ADHD: attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorder Fourth Edition, Text Revision; CSHQ: Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire; CGSQ: Caregiver Strain Questionnaire; RBS-R: Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised; SSP: Short Sensory Profile; ∗p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Social communication

(Left to right) Change from baseline to week 4 on the ABC Social Withdrawal subscale, ADAMS Social Avoidance subscale, and the VAS Social Communication domain. Colored lines represent different individuals; black dotted line represents the cohort average. Lower scores indicate improvement in each domain. ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADAMS: Anxiety, Depression, and Mood Scale; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; Avg: average.

Figure 3.

Attention deficit and hyperactivity

Top (left to right): Change from baseline to week 4 on the ABC Hyperactivity subscale, ADAMS Hyperactivity subscale, Conners Inattention domain, and Conners Hyperactivity/Impulsivity domain. Bottom (left to right): Change from baseline to week 1 on the Conners DSM-IV Inattentive domain, Conners DSM-IV Hyperactivity domain, and the VAS ADHD domain per individual. Colored lines represent different individuals; black dotted line represents the cohort average. Lower scores indicate improvement in each domain. ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADAMS: Anxiety, Depression, and Mood Scale; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; ADHD: attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Avg: average.

Figure 4.

Restricted and repetitive behaviors

(Left to right) Change from baseline to week 4 on the ADAMS Obsessive Compulsive subscale, RBS-R Compulsive subscale, and the VAS Restricted/Repetitive Behavior domain. Colored lines represent different individuals; black dotted line represents the cohort average. Lower scores indicate improvement in each domain. ADAMS: Anxiety, Depression, and Mood Scale; RBS-R: Repetitive Behavior Domain – Revised; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; Avg: average.

Figure 5.

Sensory reactivity

(Left to right) Change from baseline to week 4 on the SSP total score and on the SAND total score. Colored lines represent different individuals; black dotted line represents the cohort average. Higher scores on the SSP indicate improvement, lower scores on the SAND indicate improvement. SSP: Short Sensory Profile; SAND: Sensory Assessment for Neurodevelopmental Disorders; Avg: average.

In secondary analyses, we examined the persistence of treatment effects beyond week 1 and observed sustained, nominally significant improvement at week 2 and week 4 in most domains and across caregiver (Table S1) and clinician-based (Table S2) tools, including social (ABC, ADAMS, VAS, Vineland-3) (Figure 2), ADHD symptoms (ABC, ADAMS, Conners, VAS) (Figure 3), restricted and repetitive behaviors (ADAMS, RBS-R, VAS) (Figure 4), and sensory reactivity (SSP, SAND) (Figure 5).

Results derived from clinician-rated assessments replicated findings from the caregiver reports (Table 4). Overall, nominally significant global improvement was evident based on the CGI-I, in addition to clinician-based visual analog scales reflecting key domains of social communication (Figure 2), ADHD symptoms (Figure 3), restricted and repetitive behaviors (Figure 4), speech, thinking, and learning, and activities of daily living. Nominally significant improvement was seen in sensory reactivity symptoms reflected by the SAND total score and the caregiver-rated SSP (Figure 5), but not on the clinician-rated VAS. No significant improvement was seen in sleep in either caregiver-report or clinician-rated measures.

Table 4.

Clinician-rated assessments

| Assessment tool | Domain | Mean (SD) |

Week 1 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| CGI | Severity | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.4 (1.07) | 0.32 |

| Improvementa | 0 (0) | 1.3 (0.82) | 0.009∗ | |

| Clinician VAS | Speech | 71 (21.32) | 59.5 (21.66) | 0.011∗ |

| Thinking and learning | 78.6 (9.29) | 65 (12.91) | 0.007∗ | |

| Attention, impulsivity, Hyperactivity | 71.5 (27.69) | 57.6 (26.18) | 0.028∗ | |

| Gross motor | 36 (28.36) | 34.5 (27.33) | 0.32 | |

| Restricted and repetitive behaviors | 65 (29.25) | 58.4 (29.5) | 0.027∗ | |

| Social communication | 57.5 (28.7) | 47.4 (26.73) | 0.027∗ | |

| Sensory sensitivities | 69.5 (15.17) | 65.5 (18.63) | 0.20 | |

| Activities of daily living | 62.1 (27.62) | 50.4 (27.09) | 0.011∗ | |

| Sleep | 43 (40.84) | 36 (33.81) | 0.08 | |

| SAND | Hyperreactivity | 5.9 (4.93) | 4.9 (4.12) | 0.49 |

| Hyporeactivity | 11 (7.20) | 8.9 (6.94) | 0.08 | |

| Sensory seeking | 20.1 (8.05) | 17.7 (8.84) | 0.08 | |

| Total score | 37 (12.73) | 31.5 (14.16) | 0.025∗ | |

| PPVT-5 | Standard score | 49 (10.96) | 52.8 (17.38) | 0.416 |

| Raw score | 51.1 (41.97) | 56.6 (52.26) | 0.859 | |

| EVT-3 (n = 6) | Standard score | 61.83 (13.78) | 62.33 (15.29) | 0.715 |

| Raw score | 51.33 (29.42) | 53 (30.64) | 0.463 | |

| VMI-6 (n = 7) | Standard score | 43.57 (4.16) | 44.57 (6.8) | 0.317 |

| Raw score | 6.57 (4.47) | 7.29 (3.99) | 0.096 |

CGI, Clinical Global Impression Scale; SAND, Sensory Assessment for Neurodevelopmental Disorders; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; PPVT-5, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fifth Edition; EVT-3, Expressive Vocabulary Test, Third Edition, VMI-6: Visual Motor Integration, Sixth Edition, ∗p < 0.05.

CGI-Improvement scale change was measured from a baseline of 0 where 1 = minimally improved, 2 = much improved, and 3 = very much improved.

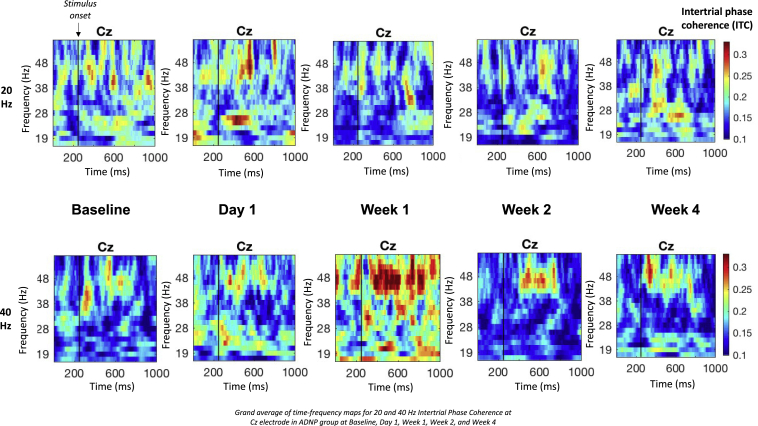

EEG data were collected from 10 participants at all study time points. After data cleaning and excluding participants with fewer than five wavelets at any time point, 7 participants were included in 40-Hz analyses, and eight participants were included in 20-Hz analyses. Average ITC at each time point was calculated from central electrode Cz. Results from EEG measures show that 40-Hz (gamma) ITC significantly increased from baseline to week 1 (p = 0.05) and 20-Hz (beta) ITC significantly decreased from baseline to week 1 (p = 0.05) (Figure 6; Table S3). No significant differences were found in gamma or beta ITC between baseline and any other time point (p > 0.1).

Figure 6.

Time-frequency maps for 20- and 40-Hz intertrial phase coherence

Grand average of time-frequency maps for 20- and 40-Hz intertrial phase coherence at Cz electrode in ADNP group at baseline, day 1, week 1, week 2, and week 4.

Eye tracking data were successfully collected from nine participants for the Joint Attention task, but only four participants (three male, Mage = 9.38 ± 2.32) had >25% valid trials at all three time points and were included in analysis. The proportion of trials in which participants made saccades to the target before the distractor increased at both day 1 (r = 0.91, p = 0.068) and week 1 (r = 0.80; p = 0.109). The proportion of time participants spent looking at the target also increased at day 1 (r = 0.91, p = 0.068) and week 1 (r = 0.913; p = 0.068). However, there was no significant change in saccade latency to target from baseline to either day 1 (r = 0.18, p = 0.72) or week 1 (r = 0.37, p = 0.47) (Table 5 and Table S4).

Table 5.

Joint attention eye-tracking paradigm

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

Baseline to day 1 |

Baseline to week 1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Day 1 | Week 1 | Effect size (r) | p | Effect size (r) | P | |

| Proportion of target-first saccades | 0.53 (0.14) | 0.75 (0.17) | 0.70 (0.14) | 0.91 | 0.068 | 0.8 | 0.109 |

| Latency to first saccade (ms) | 2319.38 (1202.34) | 2089.96 (754.70) | 1674.18 (301.93) | 0.18 | 0.715 | 0.37 | 0.465 |

| Proportion of target dwelling | 0.51 (0.19) | 0.59 (0.13) | 0.66 (0.11) | 0.91 | 0.068 | 0.91 | 0.068 |

Average proportion of trials in which participants made saccades to the target before the distractor, latency to first saccade to the target (ms), and proportion of time participants spent dwelling on the target versus distractor. An analysis using a Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was applied to assess differences in each of these measures from baseline to both day 1 and week 1.

Discussion

The results of this small, but unique study are intended to be hypothesis generating and suggest that ketamine was generally safe and well tolerated in children with ADNP syndrome. The most common treatment emergent AEs were fatigue, increased aggression, elated/silly behavior, decreased appetite, and worsening anxiety. Only one participant experienced an adverse event (vomiting) during the infusion; other AEs were mild to moderate in severity, and none required intervention or changes to the study protocol.

Nominally significant treatment effects were evident across several domains using a wide variety of measurement tools. Ketamine was associated with global improvement in addition to significant improvement in specific domains of social behavior, attention deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and sensory reactivity. No significant improvement was seen in sleep in either caregiver-report or clinician-rated measures. Importantly, results across clinician-rated and caregiver-rated assessments were largely consistent.

Using ASSR, the increase in evoked gamma band oscillations at week 1 suggests an effect of ketamine related to enhancing glutamatergic functioning, likely caused by NMDA receptor modulation. Conversely, the decrease in beta ITC at week 1 may be indicative of ketamine inhibiting GABAergic interneurons and causing decreased GABA concentrations.56, 57, 58 These findings may be important in the treatment of ADNP syndrome; gamma and beta neural oscillations are implicated in several cognitive processes, such as working memory,59, 60, 61 in addition to sensory processing,62 and suggest the potential of ASSR as a biomarker of ketamine treatment response.

Findings from eye-tracking technology using the Joint Attention task suggest a trend toward improved Joint Attention at day 1 and week 1 demonstrated by both an increase in Joint Attention accuracy and in time spent looking at the target. Saccade latency to the target did not change, suggesting that accuracy and attention, but not speed, were sensitive to treatment. Further, eye-tracking improvements were seen within 1 day after treatment, providing preliminary evidence that this tool may be a useful biomarker to index early change in social attention with ketamine.

In ASD broadly, only one study has previously examined the effect of ketamine. Using a placebo-controlled crossover design in a heterogeneous sample of affected adults, investigators applied two fixed doses of ketamine delivered through intranasal administration. Results suggested that ketamine was safe, but no significant improvement in social withdrawal or other clinical outcome assessments were detected.63 However, single gene causes of ASD, such as ADNP syndrome, represent important opportunities to constrain ASD heterogeneity and identify a subset of individuals for targeted treatment and perhaps enhanced response. With the exception of a single case report supporting the use of risperidone (0.2 mg twice daily) for irritability in a 2.5-year-old child with ADNP syndrome,64 there have been no published treatment studies in the condition to date, and there remains a large unmet need. In addition, developing new treatments in ADNP syndrome may eventually inform treatment development in ASD more broadly based on common underlying molecular pathways or shared electrophysiological profiles.

Results must also be interpreted with caution given the small number of participants, the absence of a placebo-control group, and the use of clinical outcome measures that have not been well validated in ADNP syndrome. Furthermore, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons that may increase the risk of type I error. In addition, while the potential for increased ADNP gene expression served as the rationale for this clinical trial, preliminary analysis revealed that the variance in expression was too high in this small sample to draw any definitive conclusions. Despite these limitations, findings from this initial pilot study clearly provide support for continuing the ketamine clinical development program in ADNP syndrome and identify useful endpoints for such a program.

Future studies will employ a randomized, placebo-controlled design and study the effects of repeated ketamine dosing over a longer duration of time and in a larger cohort of participants. Future studies will also use RNA sequencing to measure change in ADNP expression and other genes, as well as DNA methylation analysis, which has been previously described as relevant in ADNP syndrome.65,66

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the families who participated and to the ADNP Kids Research Foundation and the Foundation for Mood Disorders for their support. Support for mediKanren was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through the Biomedical Data Translator Program, awards OT2TR003435 and OT2TR002517. Any opinions expressed in this document are those of the Translator community at large and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCATS, individual Translator team members, or affiliated organizations and institutions.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04388774, Low-Dose Ketamine in Children with ADNP Syndrome, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04388774.

Declaration of interests

Alexander Kolevzon is on the scientific advisory boards of Ovid Therapeutics, Ritrova Therapeutics, and Jaguar Therapeutics and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Clinilabs Drug Development Corporation, and Scioto Biosciences. Paige M. Siper and Mount Sinai licensed the Sensory Assessment for Neurodevelopmental Disorders (SAND) developed by PMS to Stoelting, Co. Sandra Sermone is on the board of directors of ADNP Kids Research Foundation, has patent applications filed for ketamine and ketamine/NAP for the treatment of ADNP syndrome and related neurological conditions, and is a parent of a child with ADNP syndrome. Matthew Davis is on the scientific advisory board of ADNP Kids Research Foundation, has patent applications filed for ketamine and ketamine/NAP for the treatment of ADNP syndrome and related neurological conditions, and is a parent of a child with ADNP syndrome. Joseph D. Buxbaum consults for BridgeBio Pharma. The remainder of the authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2022.100138.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Satterstrom F.K., Kosmicki J.A., Wang J., Breen M.S., De Rubeis S., An J.Y., Peng M., Collins R., Grove J., Klei L., et al. Large-scale exome sequencing study implicates both developmental and functional changes in the neurobiology of autism. Cell. 2020;180:568–584.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helsmoortel C., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T., Coe B.P., Vandeweyer G., Rooms L., van den Ende J., Schuurs-Hoeijmakers J.H.M., Marcelis C.L., Willemsen M.H., Vissers L.E.L.M., et al. A SWI/SNF-related autism syndrome caused by de novo mutations in ADNP. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:380–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature. 2017;542:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nature21062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett A.B., Rhoads C.L., Hoekzema K., Turner T.N., Gerdts J., Wallace A.S., Bedrosian-Sermone S., Eichler E.E., Bernier R.A. The autism spectrum phenotype in ADNP syndrome. Autism Res. 2018;11:1300–1310. doi: 10.1002/aur.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dijck A., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T., Cappuyns E., van der Werf I.M., Mancini G.M., Tzschach A., Bernier R., Gozes I., Eichler E.E., Romano C., et al. Clinical presentation of a complex neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in ADNP. Biol. Psychiatry. 2019;85:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siper P.M., Layton C., Levy T., Lurie S., Benrey N., Zweifach J., Rowe M., Tang L., Guillory S., Halpern D., et al. Sensory reactivity symptoms are a core feature of ADNP syndrome irrespective of autism diagnosis. Genes. 2021;12:351. doi: 10.3390/genes12030351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandel S., Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein constitutes a novel element in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34448–34456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandel S., Rechavi G., Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) differentially interacts with chromatin to regulate genes essential for embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2007;303:814–824. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merenlender-Wagner A., Malishkevich A., Shemer Z., Udawela M., Gibbons A., Scarr E., Dean B., Levine J., Agam G., Gozes I. Autophagy has a key role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:126–132. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vulih-Shultzman I., Pinhasov A., Mandel S., Grigoriadis N., Touloumi O., Pittel Z., Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein snippet NAP reduces tau hyperphosphorylation and enhances learning in a novel transgenic mouse model. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323:438–449. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacohen-Kleiman G., Yizhar-Barnea O., Touloumi O., Lagoudaki R., Avraham K.B., Grigoriadis N., Gozes I. Atypical auditory brainstem response and protein expression aberrations related to ASD and hearing loss in the Adnp haploinsufficient mouse brain. Neurochem. Res. 2019;44:1494–1507. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patton M., Rosenblatt G., Byrd W.E., Might M., editors. mediKanren: A System for Bio-Medical Reasoning. The 2020 Workshop on miniKanren. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown B.P., Kang S.C., Gawelek K., Zacharias R.A., Anderson S.R., Turner C.P., Morris J.K. In vivo and in vitro ketamine exposure exhibits a dose-dependent induction of activity-dependent neuroprotective protein in rat neurons. Neuroscience. 2015;290:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaj C., Bringmann A., Schmidt E.M., Urbischek M., Lamprecht S., Fröhlich T., Arnold G.J., Krebs S., Blum H., Hermeking H., et al. ADNP is a therapeutically inducible repressor of WNT signaling in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:2769–2780. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slikker W., Jr., Zou X., Hotchkiss C.E., Divine R.L., Sadovova N., Twaddle N.C., Doerge D.R., Scallet A.C., Patterson T.A., Hanig J.P., et al. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;98:145–158. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinner B., Friedrich O., Zink W., Martin E., Fink R.H.A., Graf B.M. Ketamine stereoselectively inhibits spontaneous Ca2+-oscillations in cultured hippocampal neurons. Anesth. Analg. 2005;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150946.18875.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fava M., Freeman M.P., Flynn M., Judge H., Hoeppner B.B., Cusin C., Ionescu D.F., Mathew S.J., Chang L.C., Iosifescu D.V., et al. Correction: double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) Mol. Psychiatry. 2020;25:1604. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0311-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen M.H., Cheng C.M., Gueorguieva R., Lin W.C., Li C.T., Hong C.J., Tu P.C., Bai Y.M., Tsai S.J., Krystal J.H., Su T.P. Maintenance of antidepressant and antisuicidal effects by D-cycloserine among patients with treatment-resistant depression who responded to low-dose ketamine infusion: a double-blind randomized placebo-control study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:2112–2118. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0480-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen M.H., Lin W.C., Tu P.C., Li C.T., Bai Y.M., Tsai S.J., Su T.P. Antidepressant and antisuicidal effects of ketamine on the functional connectivity of prefrontal cortex-related circuits in treatment-resistant depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, longitudinal resting fMRI study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;259:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan J., Jiang H. Dual effects of ketamine: neurotoxicity versus neuroprotection in anesthesia for the developing brain. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2014;26:155–160. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurdi M.S., Theerth K.A., Deva R.S. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth. Essays Res. 2014;8:283–290. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.143110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner C.P., Gutierrez S., Liu C., Miller L., Chou J., Finucane B., Carnes A., Kim J., Shing E., Haddad T., Phillips A. Strategies to defeat ketamine-induced neonatal brain injury. Neuroscience. 2012;210:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivarao D.V., Chen P., Senapati A., Yang Y., Fernandes A., Benitex Y., Whiterock V., Li Y.W., Ahlijanian M.K. 40 Hz auditory steady-state response is a Pharmacodynamic biomarker for cortical NMDA receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2232–2240. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Light G.A., Zhang W., Joshi Y.B., Bhakta S., Talledo J.A., Swerdlow N.R. Single-dose memantine improves cortical oscillatory response dynamics in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2633–2639. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tada M., Kirihara K., Koshiyama D., Fujioka M., Usui K., Uka T., Komatsu M., Kunii N., Araki T., Kasai K. Gamma-band auditory steady-state response as a neurophysiological marker for excitation and inhibition balance: a review for understanding schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2020;51:234–243. doi: 10.1177/1550059419868872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sragovich S., Malishkevich A., Piontkewitz Y., Giladi E., Touloumi O., Lagoudaki R., Grigoriadis N., Gozes I. The autism/neuroprotection-linked ADNP/NAP regulate the excitatory glutamatergic synapse. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9:2. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0357-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yavi M., Lee H., Henter I.D., Park L.T., Zarate C.A., Jr. Ketamine treatment for depression: a review. Discov. Ment. Health. 2022;2:9. doi: 10.1007/s44192-022-00012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strous J.F.M., Weeland C.J., van der Draai F.A., Daams J.G., Denys D., Lok A., Schoevers R.A., Figee M. Brain changes associated with long-term ketamine abuse, A systematic review. Front. Neuroanat. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2022.795231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer H.F., Berman R.Y., Boese M., Zhang M., Kim S.Y., Radford K.D., Choi K.H. Effects of an intravenous ketamine infusion on inflammatory cytokine levels in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:75. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02434-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Association A.P. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lord C., Rutter M., DiLavore P., Risi S., Gotham K., Bishop S. Western Psychological Services; California: 2012. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, (ADOS-2) Modules 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutter M., Le Couteur A., Lord C. Vol. 29. Western Psychological Services; 2003. p. 30. (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esbensen A.J., Rojahn J., Aman M.G., Ruedrich S. Reliability and validity of an assessment instrument for anxiety, depression, and mood among individuals with mental retardation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003;33:617–629. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005999.27178.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer C., Golden C., Thurm A. Concurrent validity of the differential ability scales, second edition with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning in young children with and without neurodevelopmental disorders. Child Neuropsychol. 2016;22:556–569. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2015.1020775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sparrow S., Cicchetti D., Saulnier C. Third edition. American Guidance Service; 2016. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spanos M., Chandrasekhar T., Kim S.J., Hamer R.M., King B.H., McDougle C.J., Sanders K.B., Gregory S.G., Kolevzon A., Veenstra-VanderWeele J., Sikich L. Rationale, design, and methods of the autism centers of excellence (ACE) network study of oxytocin in autism to improve reciprocal social behaviors (SOARS-B) Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2020;98 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aman M.G., Singh N.N., Stewart A.W., Field C.J. Psychometric characteristics of the aberrant behavior checklist. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 1985;89:492–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam K.S.L., Aman M.G. The repetitive behavior scale-revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007;37:855–866. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn W. Psychological Corporation; 1999. Sensory Profile. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owens J.A., Spirito A., McGuinn M. The children's sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23:1043–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brannan A.M., Heflinger C.A., Bickman L. The caregiver strain questionnaire: measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 1997;5:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conners C.K., Rzepa S.R., Pitkanen J., Mears S. Conners. 3rd Edition. Springer; Cham: 2018. (Conners 3; Conners 2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guy W. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siper P.M., Kolevzon A., Wang A.T., Buxbaum J.D., Tavassoli T. A clinician-administered observation and corresponding caregiver interview capturing DSM-5 sensory reactivity symptoms in children with ASD. Autism Res. 2017;10:1133–1140. doi: 10.1002/aur.1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beery K.E. Pearson; 2004. Beery VMI: The Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams K. Third Edition. Pearson; 2018. Expressive Vocabulary Test. (EVT-3) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn D. Fifth Edition. Pearson; 2018. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. (PPVT-5) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedford R., Elsabbagh M., Gliga T., Pickles A., Senju A., Charman T., Johnson M.H., BASIS team Precursors to social and communication difficulties in infants at-risk for autism: gaze following and attentional engagement. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012;42:2208–2218. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green S.M., Krauss B. Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation in children. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2004;44:460–471. doi: 10.1016/S0196064404006365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murrough J.W., Soleimani L., DeWilde K.E., Collins K.A., Lapidus K.A., Iacoviello B.M., Lener M., Kautz M., Kim J., Stern J.B., et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:3571–3580. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feder A., Parides M.K., Murrough J.W., Perez A.M., Morgan J.E., Saxena S., Kirkwood K., Aan Het Rot M., Lapidus K.A.B., Wan L.B., et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2014;71:681–688. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green S.M., Roback M.G., Krauss B., Brown L., McGlone R.G., Agrawal D., McKee M., Weiss M., Pitetti R.D., Hostetler M.A., et al. Predictors of airway and respiratory adverse events with ketamine sedation in the emergency department: an individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8, 282 children. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009;54:158–168.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green S.M., Roback M.G., Krauss B., Brown L., McGlone R.G., Agrawal D., McKee M., Weiss M., Pitetti R.D., Hostetler M.A., et al. Predictors of emesis and recovery agitation with emergency department ketamine sedation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8, 282 children. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009;54:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hodges J.L., Lehmann E.L. The efficiency of some nonparametric competitors of the $t$-Test. Ann. Math. Statist. 1956;27:324–335. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumgarten T.J., Oeltzschner G., Hoogenboom N., Wittsack H.J., Schnitzler A., Lange J. Beta peak frequencies at rest correlate with endogenous GABA+/Cr concentrations in sensorimotor cortex areas. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jensen O., Goel P., Kopell N., Pohja M., Hari R., Ermentrout B. On the human sensorimotor-cortex beta rhythm: sources and modeling. Neuroimage. 2005;26:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdallah C.G., Sanacora G., Duman R.S., Krystal J.H. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015;66:509–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carr M.F., Karlsson M.P., Frank L.M. Transient slow gamma synchrony underlies hippocampal memory replay. Neuron. 2012;75:700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lundqvist M., Rose J., Herman P., Brincat S.L., Buschman T.J., Miller E.K. Gamma and beta bursts underlie working memory. Neuron. 2016;90:152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto J., Suh J., Takeuchi D., Tonegawa S. Successful execution of working memory linked to synchronized high-frequency gamma oscillations. Cell. 2014;157:845–857. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugiyama S., Ohi K., Kuramitsu A., Takai K., Muto Y., Taniguchi T., Kinukawa T., Takeuchi N., Motomura E., Nishihara M., et al. The auditory steady-state response: electrophysiological index for sensory processing Dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Front. Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.644541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wink L.K., Reisinger D.L., Horn P., Shaffer R.C., O'Brien K., Schmitt L., Dominick K.R., Pedapati E.V., Erickson C.A. Brief report: intranasal ketamine in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder-initial results of a randomized, controlled, crossover, pilot study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021;51:1392–1399. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04542-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shillington A., Pedapati E., Hopkin R., Suhrie K. Early behavioral and developmental interventions in ADNP-syndrome: a case report of SWI/SNF-related neurodevelopmental syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2020;8 doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Breen M.S., Garg P., Tang L., Mendonca D., Levy T., Barbosa M., Arnett A.B., Kurtz-Nelson E., Agolini E., Battaglia A., et al. Episignatures stratifying Helsmoortel-Van der Aa syndrome show modest correlation with phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;107:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bend E.G., Aref-Eshghi E., Everman D.B., Rogers R.C., Cathey S.S., Prijoles E.J., Lyons M.J., Davis H., Clarkson K., Gripp K.W., et al. Gene domain-specific DNA methylation episignatures highlight distinct molecular entities of ADNP syndrome. Clin. Epigenetics. 2019;11:64. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0658-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.