Abstract

Objective

Warfarin anticoagulation management requires sequential decision-making to adjust dosages based on patients’ evolving states continuously. We aimed to leverage reinforcement learning (RL) to optimize the dynamic in-hospital warfarin dosing in patients after surgical valve replacement (SVR).

Materials and Methods

10 408 SVR cases with warfarin dosage–response data were retrospectively collected to develop and test an RL algorithm that can continuously recommend daily warfarin doses based on patients’ evolving multidimensional states. The RL algorithm was compared with clinicians’ actual practice and other machine learning and clinical decision rule-based algorithms. The primary outcome was the ratio of patients without in-hospital INRs >3.0 and the INR at discharge within the target range (1.8–2.5) (excellent responders). The secondary outcomes were the safety responder ratio (no INRs >3.0) and the target responder ratio (the discharge INR within 1.8–2.5).

Results

In the test set (n = 1260), the excellent responder ratio under clinicians’ guidance was significantly lower than the RL algorithm: 41.6% versus 80.8% (relative risk [RR], 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48–0.55), also the safety responder ratio: 83.1% versus 99.5% (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81–0.86), and the target responder ratio: 49.7% versus 81.1% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.58–0.65). The RL algorithms performed significantly better than all the other algorithms. Compared with clinicians’ actual practice, the RL-optimized INR trajectory reached and maintained within the target range significantly faster and longer.

Discussion

RL could offer interactive, practical clinical decision support for sequential decision-making tasks and is potentially adaptable for varied clinical scenarios. Prospective validation is needed.

Conclusion

An RL algorithm significantly optimized the post-operation warfarin anticoagulation quality compared with clinicians’ actual practice, suggesting its potential for challenging sequential decision-making tasks.

Keywords: anticoagulation, clinical decision-making, dynamic treatment regime, reinforcement learning, warfarin

INTRODUCTION

Background and significance

A dynamic treatment regime (DTR), or an adaptive treatment strategy, refers to a sequence of decision rules that determines specific treatments at each time step along the treatment course,1,2 which fits into the general concept of personalized medicine by integrating individualized treatment into a time-varying setting.3 DTRs are widely practiced in managing chronic conditions and high-stake situations that require repeatedly tailoring treatment decisions according to the patient’s dynamic states. Achieving the optimal DTR can be challenging as it demands clinicians to promptly assess the accrued treatment information, predict the future trajectory, and make sequential decisions. One of the typical and challenging DTR scenarios in current clinical practice is anticoagulation management.

Patients undergoing surgical valve replacement (SVR) require immediate anticoagulation after surgery. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, is the most widely used oral anticoagulant and the only lifelong oral anticoagulation choice after mechanical valve replacement, as well as the short-term option for bioprosthetic valve.4,5 However, known for its wide inter- and intraindividual variability in response and delayed onset and offset of action, warfarin anticoagulation management is challenging. In the immediate post-operation setting, clinicians need to carefully manage warfarin by continuously monitoring the prothrombin time international normalized ratio (INR) and adjusting the dose accordingly. This is a delicate process that demands extensive experience with increased workload, and yet still often results in suboptimal outcomes.6 The consequences of imprecise or delayed warfarin titration can be even more significant in the post-operation setting, including increased bleeding or thromboembolism risk, prolonged hospital stay, etc. Except for general guidance,4,7 currently there are no practical tools as continuous decision support in guiding clinicians through the in-hospital warfarin dosing process either reliably or flexibly.

Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) have achieved outstanding performance in various clinical tasks, with high computational capacity and self-learning and decision-making ability.8,9 Leveraging the abundance of electronic health record (EHR) data generated daily, AI can help optimize clinical care. Reinforcement learning (RL), a semisupervised AI technology in the intersection of machine learning (ML) and control theory,10,11 is specialized in solving tasks characterized by sequential decision-making, stochasticity, and individualization. RL operates in a trial-and-error approach through interaction with the environment to learn and gradually improve its decision-making ability and can continuously receive input information and offer optimal output recommendations. These intrinsic properties make RL desirable for solving complex decision-making problems in clinical practice. Recently, apart from its original popularity in nonmedical industries, RL has been successfully experienced in several clinical scenarios, including mechanical ventilation support,12 sepsis management,13 erythropoiesis-stimulating agent therapy in renal anemia,14 treatment of epilepsy15 and schizophrenia,16 HIV therapy,17 cancer treatment planning,18 blood glucose control,19 and multimorbidity care,20 etc.

Objective

To solve the dynamic task of determining the best warfarin dosage at each time step for SVR patients during the post-operation hospital stay, we trained an RL algorithm, from EHR records containing high-volume real-world warfarin dosage–response experience, that can guide and optimize the DTR of warfarin dosing. Several ML algorithms and a clinical decision rule-based algorithm were also constructed for comparison. We hypothesized that the RL algorithm could significantly outperform the clinicians’ actual guidance of warfarin dosing on real-world SVR patients, with respect to the overall anticoagulation quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and data set

We retrospectively identified and included all adult patients undergoing isolated SVR in Fuwai hospital (Beijing) between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2018. The inclusion criteria were all patient admissions with records of isolated valve replacement in the above period, identified with surgery codes in the hospital EHR system. Cases were excluded if: (1) age less than 18 years old, (2) valve replacement performed in transcatheter approach (including transfemoral and transapical assess), or (3) surgical procedures involving valve replacement but primarily intended for correcting nonvalvular lesions or without prosthetic implants (eg, Bentall procedure, Wheat’s procedure, or Ross procedure). We further excluded cases without any same-day post-operation INR results and warfarin orders. Cases were reassigned separately for patients with more than 1 SVR record. All the remaining cases were linked with the unique case identifiers and constitute the final data set. Cases performed after January 1, 2018 constituted the test set. Cases from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2017 were further randomly divided (9:1) into training and validation sets.

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institute review board (IRB) at Fuwai hospital. Informed consent requirement was waived by the IRB as all patient data were collected retrospectively, and all case records were deidentified before analysis.

Data extraction and preprocessing

All pertinent information was extracted from EHRs through automatic capture and supplemented with manual entries. A total of 31 variables were selected as baseline features for each patient (Supplementary Table S1), including demographics, comorbidities, routine peri-operation echocardiographic and laboratory test results prior to warfarin initiation, surgery-related information, including post-operation major bleeding events before warfarin initiation, adjudicated per the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium Type 4 bleeding21 definition by 2 clinicians independently. All daily INR records and warfarin orders were extracted in bulk and were linked to the unique case identifiers individually. To determine the same-day INR-warfarin pair, we matched the reporting date of INR records to the beginning date of warfarin orders for each case. If more than 1 INR record exited on 1 day, the last INR record before warfarin order placement was chosen as the decision-making INR. If more than 1 warfarin order were placed and executed on 1 day, all these warfarin doses were summed as the decided warfarin dosage.

Clinical scenario modeling and RL algorithm development

In clinical practice, an INR target range is recommended as the warfarin treatment goal to ensure therapeutic anticoagulation, and patients should be maintained within this range.4,5 In our center, SVR patients after surgery are promptly anticoagulated with warfarin and routinely monitored for INRs on a daily basis, with test results available the next morning. The treating clinicians decide the daily warfarin dosage based on the morning INR, and the goal is to guide the INR toward the target range of 1.8–2.5 and then maintain it within the range. This target range was lower than those commonly recommended in the Western guidelines due to the generally lower-intensity anticoagulation in the Eastern practice, given the known greater sensitivity of Eastern populations to warfarin and the corresponding much higher bleeding risk. Within a framework termed the Markov decision process used to model the sequential decision-making tasks in RL,22,23 an agent with an initial state (S) takes an action (A) and interacts with the environment. Each action it takes comes with the feedback of reward (R) and transition to the next state (S′), through which the agent upgrades its understanding of the environment. After a series of action-feedback explorations, the agent gradually learns an optimal policy (π*) that can maximize its future overall reward. Policy (π) is a term in RL that governs an agent’s actions in each possible state. A detailed explanation of the computational environment for RL is described in the Supplementary Materials.

The aforementioned 31 variables, including the daily INRs, were used to construct a multidimensional vector representing the patient’s daily state (S) at each warfarin dosage deciding time step for RL. Based on the state, the RL algorithm recommends an action of the warfarin dosage (A). Following each action taken, a reward (R) is assigned based on the next-day feedback INR relative to the target range to inform how good or bad each action is, through which the algorithm learns and improves its policy (π). Detailed reward assignment rules are shown in Supplementary Table S2. After training iterations, the obtained optimal policy (π*) can then govern the RL algorithm recommendation during implementation to achieve the maximal overall reward. A full description of RL algorithms is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Other warfarin dosing algorithms for comparison

Several warfarin dosing algorithms based on clinical dosing protocols or ML technology were constructed additionally for comparison. For the baseline clinical protocol algorithm, a warfarin dosing protocol (Supplementary Table S4) designed for post-operation valve replacement patients aiming at the same INR target range of 1.8–2.524 was used and constructed into a decision rule-based (RB) algorithm. For ML-based algorithms, we constructed a long short-term memory (LSTM) algorithm of recurrent neural networks,25 a feedforward artificial neural network (ANN) algorithm,26 an evolutionary ensemble modeling (EEM) algorithm with genetic programming and genetic algorithm,27 and a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm.28 To construct these ML algorithms traditionally used for prediction tasks to tackle the sequential decision-making task of warfarin dosing, we used only the high-quality anticoagulation patients from the clinicians’ actual practice as training samples so that the trained algorithms can predict warfarin dosages similar to the high-quality decisions made by clinicians. The aforementioned 31 variables (including daily INR), with the addition of the last day INR, constituted the algorithm’s daily input, based on which ML algorithms sequentially predicted the daily dosages.

k-Nearest neighbors prediction

Evaluating algorithm performance in an offline RL study design is challenging, because retrospectively, the current algorithm recommendations could not actually be implemented in patients, and all the INR-warfarin trajectories were already pre-determined in reality. Therefore, we adopted a semi-online approach where the trained algorithms recommended warfarin dosages to the patient representatives that shared the same initial states with the real patient at each time step, and the resulting INR responses were immediately predicted using the k nearest neighbors (kNN) method.29 Thus, algorithms can continuously interact with patient representatives, enabling directly comparing outcomes of interests between the real-world patients under clinicians’ guidance and the same patient representatives under algorithms’ guidance. In the current study, kNN predicted the next-day INR following each algorithm-recommended dosage using the known actual INRs from the other k most clinically similar patients who actually received the same or similar dosage in reality. Both the all-feature and key-feature strategies were used to profile the clinical similarities of neighbors. A full description of kNN prediction and a list of key features (Supplementary Table S5) are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

Reward-based evaluation of RL algorithm performance

As each action of warfarin dosage was assigned with a reward based on the next-day INR feedback, an overall reward can be calculated for each patient by accumulating all rewards following the INR trajectory. The overall rewards under the clinician- and all algorithm-guided strategies were compared in the test set.

Study outcomes and metrics for anticoagulation quality

To assess the overall anticoagulation quality, we defined 2 criteria for high-quality warfarin anticoagulation: (1) no INRs > 3.0 after warfarin initiation during the entire post-operation stay; (2) the INR at discharge within the target range of 1.8–2.5. The patient fulfilling both the above criteria was termed the excellent responder (ER), and the primary outcome of was the excellent responder ratio (ie, the proportion of patients adjudicated as the excellent responder in the test set). The individual components of the above criteria defined the safety responder (SR) (no INRs > 3.0 after warfarin initiation) and the target responder (TR) (the discharge INR within 1.8–2.5), respectively. The SR and TR ratios were 2 secondary outcomes. To illustrate the dynamic anticoagulation process, the INR trajectories under 2 strategies were visualized from warfarin initiation to discharge or 30 days after surgery (whichever came first). Two important time-related metrics, the mean time to INRs first reaching the target range and the mean time of INRs maintained within the target range, were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared with the Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for nonnormally distributed data. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The time-to-event outcome was analyzed with the Kaplan–Meier method and tested with log-rank analysis, with Cox proportional-hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HR). Subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the consistency of treatment effects across different subgroups. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all sample variability in the estimates, which have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons and should not be used to infer definitive effects. All comparisons were 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P < .05. All statistical analysis and plotting were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Data sets and patient characteristics

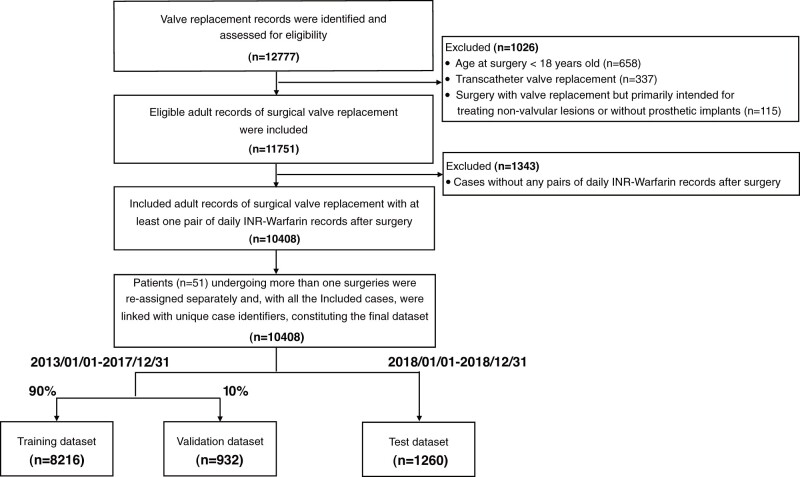

A total of 11 751 eligible SVR cases were included. After excluding cases without any same-day warfarin-INR record pairs (n = 1343), 10 408 cases constituted the final data set, with a total volume of 76 556 same-day warfarin-INR record pairs. Cases before January 1, 2018 was randomly divided (9:1) into the training (n = 8216) and validation set (n = 932), whereas cases after January 1, 2018 formed the test set (n = 1260) (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study dataset development. Overlapping existed among cases that were excluded due to different exclusion criteria. INR: international normalized ratio.

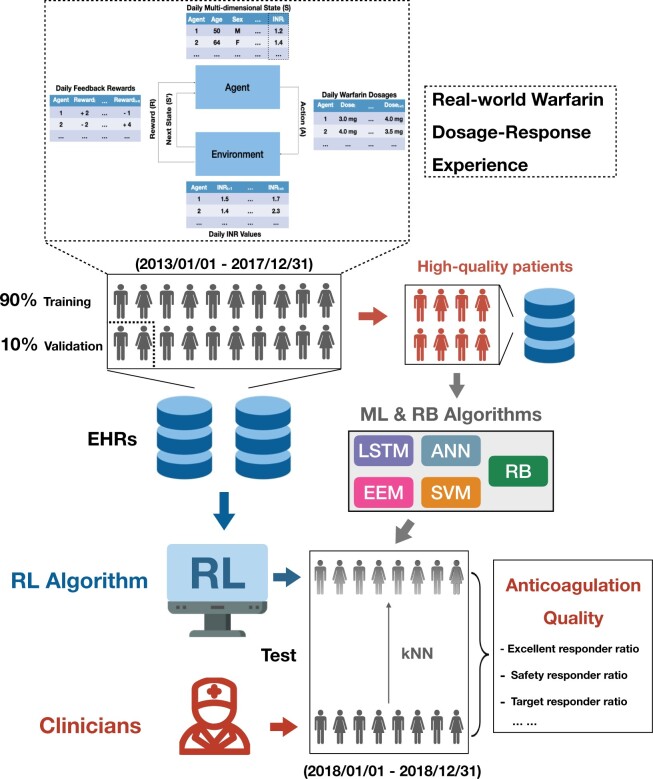

Figure 2.

Illustration of the overall study design. ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; EHRs, electronic health records; INR, international normalized ratio; kNN, k nearest neighbors; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; SVM: support vector machine.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total cohort | Training set | Validation set | Test set | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10 408) | (n = 8216) | (n = 932) | (n = 1260) | ||

| Age, years | 53.4 (11.7) | 53.2 (11.8) | 54.0 (11.1) | 54.3 (11.8) | <.01 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 5468 (52.5) | 4322 (52.6) | 510 (54.7) | 636 (50.5) | .16 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | .06 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 (3.5) | 23.9 (3.5) | 23.9 (3.4) | 24.0 (3.4) | .32 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 2954 (28.4) | 2361 (28.7) | 258 (27.7) | 335 (26.6) | .11 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 48 (0.5) | 40 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | .22 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 157 (1.5) | 116 (1.4) | 12 (1.3) | 29 (2.3) | .02 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 3974 (38.2) | 3 146 (38.3) | 389 (41.7) | 439 (34.8) | .02 |

| Prior cerebrovascular events, n (%) | 750 (7.2) | 597 (7.3) | 65 (7.0) | 88 (7.0) | .72 |

| Prior valve procedure, n (%) | 680 (6.5) | 533 (6.5) | 64 (6.9) | 83 (6.6) | .89 |

| LEVF, % | 59.8 (7.5) | 59.8 (7.6) | 60.0 (7.7) | 59.3 (6.8) | <.01 |

| NYHA class ≥3, n (%) | 4582 (44.0) | 3654 (44.5) | 440 (47.2) | 488 (38.7) | <.01 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | .17 |

| Pre-op anticoagulation, n (%) | 3218 (30.9) | 2534 (30.8) | 318 (34.1) | 366 (29.1) | .20 |

| Post-op eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 3940 (37.9) | 3151 (38.4) | 350 (37.6) | 439 (34.8) | .02 |

| Post-op liver dysfunction, n (%) | 2132 (21.0) | 1796 (22.3) | 185 (20.1) | 151 (12.9) | <.01 |

| Valve implant type, n (%) | .65 | ||||

| Mechanical | 7851 (75.4) | 6205 (75.5) | 687 (73.7) | 959 (76.1) | – |

| Biological | 2557 (24.6) | 2011 (24.5) | 245 (26.3) | 301 (23.9) | – |

| Valve implant position, n (%) | .06 | ||||

| Aortic or pulmonary | 3123 (30.0) | 2423 (29.5) | 282 (30.3) | 418 (33.2) | – |

| Mitral or tricuspid | 1392 (13.4) | 1133 (13.8) | 114 (12.2) | 145 (11.5) | – |

| Bivalvular | 5893 (56.6) | 4660 (56.7) | 536 (57.5) | 697 (55.3) | – |

| Isolated valve surgery, n (%) | 9753 (93.7) | 7701 (93.7) | 866 (92.9) | 1186 (94.1) | .59 |

| VKORC1 genotypea, n (%) | <.01 | ||||

| N.A. | 9277 (89.1) | 7820 (95.2) | 888 (95.3) | 569 (45.1) | – |

| GG | 7 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.5) | – |

| GA | 150 (1.4) | 59 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) | 89 (7.1) | – |

| AA | 974 (9.4) | 336 (4.1) | 42 (4.5) | 596 (47.3) | – |

| CYP2C9 genotypea, n (%) | <.01 | ||||

| N.A. | 9277 (89.1) | 7820 (95.2) | 888 (95.3) | 569 (45.2) | – |

| *1/*1 | 1035 (9.9) | 365 (4.4) | 36 (3.9) | 634 (50.3) | – |

| *1/*2 | 11 (0.1) | 3 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.5) | – |

| *1/*3 | 81 (0.8) | 26 (0.3) | 5 (0.5) | 50 (4.0) | – |

| *3/*3 | 4 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | – |

Note: Values are mean (SD) unless specified otherwise.

BSA: body surface area; BMI: body mass index; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; N.A.: not available; NYHA: New York Heart Association; Post-op: post-operation; Pre-op: pre-operation.

The VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genotyping for warfarin PK/PD were not routinely performed in our center before January 1, 2018.

P values refer to 2-tailed analysis between the training and test set.

KNN prediction

The kNN prediction accuracy in estimating INR response to algorithm-recommended warfarin dosages was assessed by comparing the kNN-predicted INRs under the clinicians’ actual decisions against the ground truth of the actual INRs. Varying the value of k for the number of the nearest neighbors, we found that the gaps between kNN-predicted INRs and the actual INRs were relatively insensitive when k ≥ 12, with no significant difference observed when using either all features or only the key features. Therefore, k = 12 was chosen as the number of the most clinically similar neighbors used in kNN prediction during the algorithm evaluation in the test set.

Reward-based evaluation

Compared with the clinicians’ guidance, the overall rewards were significantly higher under the guidance of the RL algorithms, all the ML algorithms, and the RB algorithms, with the RL algorithm achieving significantly higher overall rewards than all the other guiding algorithms (Supplementary Figure S1).

Anticoagulation quality outcomes

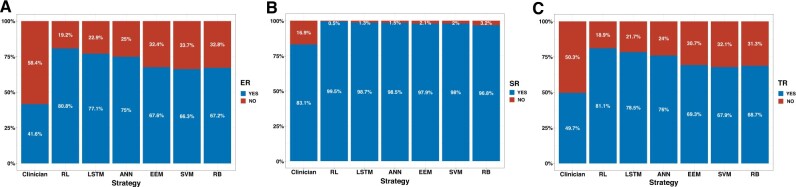

The algorithm performance in improving the overall warfarin anticoagulation quality was evaluated in the test set (n = 1260) (Figure 3 and Table 2). For the primary outcome of the excellent responder ratio, the clinicians’ actual practice was significantly lower than the RL algorithm-guided strategy (41.6% vs 80.8%; relative risk [RR] 0.51; 95% CI, 0.48–0.55, P < .001). All the other algorithms also achieved significantly lower excellent responder ratios than the RL algorithm. For the secondary outcomes, the safety responder ratio was significantly lower under the clinicians’ actual guidance than the RL algorithm (83.1% vs 99.5%; RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81–0.86; P < .001); The clinicians’ actual guidance achieved significantly lower target responder ratio compared with the RL algorithm’ guidance (49.7% vs 81.1%; RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.58–0.65; P < .001). Both the safety and target responder ratios were significantly lower in all the other algorithms than the RL algorithm.

Figure 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes of the anticoagulation quality. Comparison of the excellent responder ratio (A), the safety responder ratio (B), and the target responder ratio (C) under different strategies in the test set. ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; ER: excellent responder; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; SR: safety responder; SVM: support vector machine; TR: target responder.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes of anticoagulation quality

| Strategy | No. of events (%) | Comparison (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome—excellent responder ratio | |||

| RL | 1018/1260 (80.8) | 1 (Reference) | – |

| Clinicians | 524/1260 (41.6) | RR 0.51 (0.48–0.55) | <.001 |

| LSTM | 972/1260 (77.1) | RR 0.95 (0.92–0.99) | .025 |

| ANN | 945/1260 (75.0) | RR 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | <.001 |

| EEM | 852/1260 (67.6) | RR 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <.001 |

| SVM | 836/1260 (66.4) | RR 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | <.001 |

| RB | 847/1260 (67.2) | RR 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | <.001 |

| Secondary outcome—safety responder ratio | |||

| RL | 1254/1260 (99.5) | 1 (Reference) | – |

| Clinicians | 1047/1260 (83.1) | RR 0.83 (0.81–0.86) | <.001 |

| LSTM | 1244/1260 (98.7) | RR 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | .032 |

| ANN | 1241/1260 (98.5) | RR 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | .002 |

| EEM | 1234/1260 (97.9) | RR 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <.001 |

| SVM | 1235/1260 (98.0) | RR 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <.001 |

| RB | 1220/1260 (96.8) | RR 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | <.001 |

| Secondary outcome—target responder ratio | |||

| RL | 1022 (81.1) | 1 (Reference) | – |

| Clinicians | 626 (49.7) | RR 0.61(0.58–0.65) | <.001 |

| LSTM | 986 (78.3) | RR 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | .075 |

| ANN | 957 (76.0) | RR 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | .009 |

| EEM | 873 (69.3) | RR 0.85 (0.82–0.89) | <.001 |

| SVM | 856 (67.9) | RR 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <.001 |

| RB | 866 (68.7) | RR 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | <.001 |

ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; HR: hazard ratio; INR: international normalized ratio; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; RR: relative risk; SVM: support vector machine.

Dynamic anticoagulation process improvement

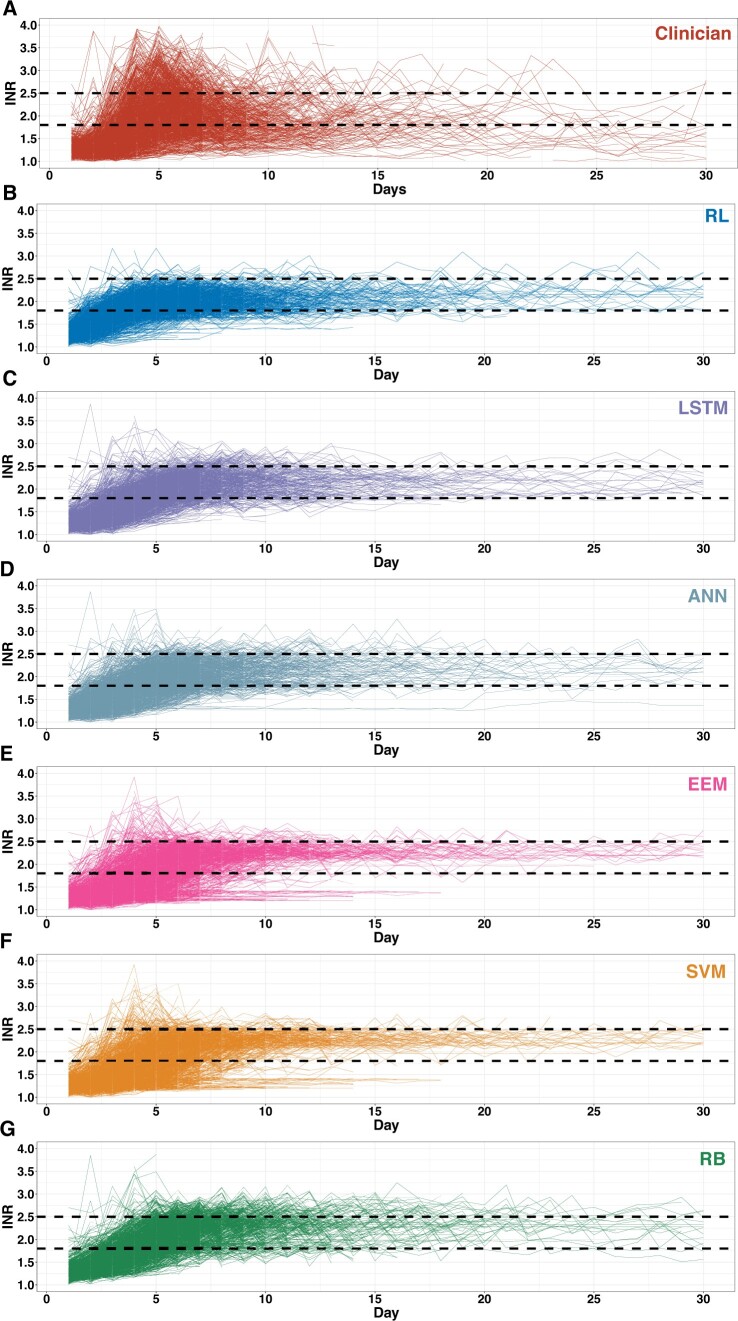

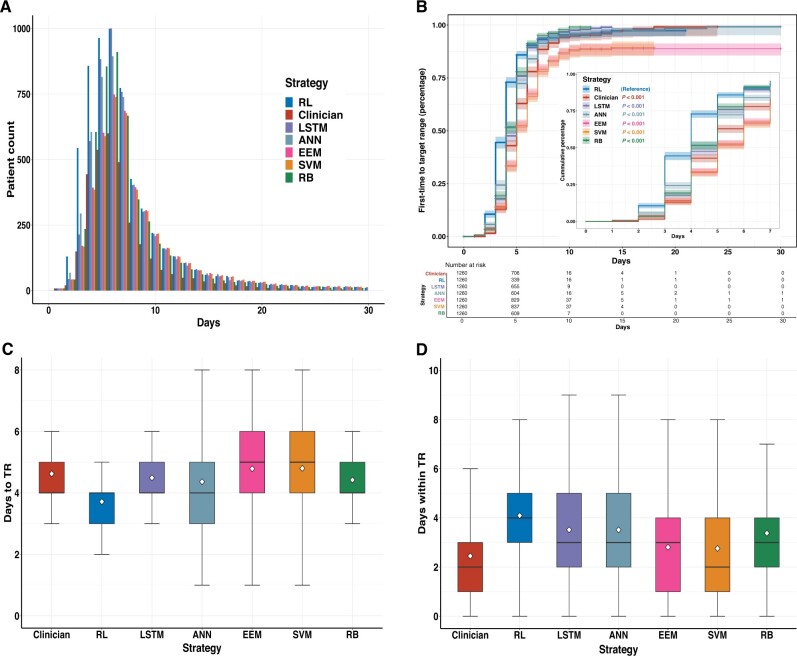

The dynamic anticoagulation process was visualized as the actual INR trajectory under the clinician-guided strategy and the kNN-predicted INR trajectory under the algorithm-guided strategies (Figure 4). The daily numbers of within-target-range patients under the RL, LSTM, ANN, and RB algorithm’s guidance consistently exceeded the clinicians’ actual practice (Figure 5A). Significant differences were demonstrated for the outcome of first time INRs reaching the target range in the Kaplan–Meier analysis (P < .001) (Figure 5B). For the time-related metrics (Table 3), among patients whose INRs were ever within the target range, the mean time INRs first reaching the target range was significantly shorter under the RL algorithm-guided strategy than the clinicians’ actual guidance (3.77 ± 1.32 days vs 4.73 ± 1.52 days; absolute difference [AD], 0.96; 95% CI, 0.84–1.08; P < .001), as well as significantly faster than all the other algorithms (Figure 5C); The mean time INRs maintained within the target range was significantly longer for the RL algorithm than the clinicians’ actual practice (4.88 ± 3.85 days vs 2.57 ± 2.29 days [AD], 2.31; 95% CI, 2.06–2.56; P < .001) and all the other algorithms (Figure 5D).

Figure 4.

Visualization of the dynamic INR trajectories. The individual INR trajectories under different strategies, plotted with daily INR against reporting date from warfarin initiation to discharge or 30 days after surgery (whichever came first), in the test set. The 2 black dotted lines represent the INR target range of 1.8–2.5. ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; INR: international normalized ratio; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; SVM: support vector machine.

Figure 5.

Time-related metrics of the dynamic anticoagulation process. In the test set, the dynamic anticoagulation process under different strategies was illustrated as: the daily distribution of patient counts within the target range until discharge or 30 days after surgery (A); the Kaplan–Meier curve illustrates the time-to-first-event outcome of INRs first reaching the target (the inset shows the same data but up to 7 days after warfarin initiation) (B); the mean time INRs first reaching the target range (C). the mean time INRs maintained within the target range (D). The central lines of boxplots indicate the median, and the top and bottom edges of box indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The vertical lines extend 1.5 times of the interquartile range. The white diamond symbols represent means. ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; INR: international normalized ratio; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; SVM: support vector machine.

Table 3.

Time-related metrics of the dynamic anticoagulation process

| Strategy | Days (±SD) | Comparison (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-related metrics—mean time INR first reaching the target range | |||

| RL | 3.77 (±1.32) | (Reference) | – |

| Clinicians | 4.73 (±1.52) | AD 0.96 (0.84–1.08) | <.001 |

| LSTM | 4.53 (±1.29) | AD 0.76 (0.65–0.87) | <.001 |

| ANN | 4.45 (±1.63) | AD 0.68 (0.56–0.80) | <.001 |

| EEM | 4.87 (±1.54) | AD 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | <.001 |

| SVM | 4.89 (±1.57) | AD 1.12 (0.99–1.24) | <.001 |

| RB | 4.46 (±1.24) | AD 0.69 (0.59–0.80) | <.001 |

| Time-related metrics—mean time INR maintained within the target range | |||

| RL | 4.88 (±3.85) | (Reference) | – |

| Clinicians | 2.57 (±2.29) | AD 2.31 (2.06–2.55) | <.001 |

| LSTM | 4.33 (±4.47) | AD 0.54 (0.22–0.87) | <.001 |

| ANN | 4.23 (±4.50) | AD 0.65 (0.32–0.97) | <.001 |

| EEM | 3.67 (±4.87) | AD 1.21 (0.87–1.55) | <.001 |

| SVM | 3.65 (±5.00) | AD 1.23 (0.88–1.58) | <.001 |

| RB | 3.92 (±3.85) | AD 0.96 (0.66–1.26) | <.001 |

AD: absolute difference; ANN: artificial neural network; EEM: evolutionary ensemble modeling; INR: international normalized ratio; LSTM: long short-term memory; RB: rule-based; RL: reinforcement learning; SVM: support vector machine.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

Several subgroups were exanimated for potential interactions with the guiding strategies (Supplementary Figures S2–S4). The benefits of the RL algorithm over clinicians regarding the primary and secondary outcomes were consistent across the following subgroups: patients with or without post-operation liver dysfunction, post-operation renal dysfunction, pre-operation anticoagulation, warfarin genotype availability, and more than once dosing on 1 day.

To evaluate the robustness of the RL algorithm, several sensitivity analyses were conducted, including changing the INR safety threshold to INR > 4.5 (Supplementary Table S6), changing to a wider INR target range of 1.5–2.5 (Supplementary Table S7), retraining the RL algorithm with more penalties to under-anticoagulation in reward assignment rules (Supplementary Tables S3 and S8), and retraining with 7:1:2 randomly-split data set. The RL algorithm consistently outperformed the clinicians with these changes (Supplementary Table S9). The potential scalability of the RL algorithm to other practices with different INR target ranges was also explored by retraining with the target range of 2.0–3.0 (Supplementary Table S10).

DISCUSSION

We presented an AI algorithm of RL to optimize the DTR of warfarin dosing in patients after SVR. In a semi-online approach of the real-world patients and their representatives, the RL algorithm-guided strategy significantly outperformed the clinicians’ actual practice as well as other ML and clinical decision rule-based algorithms, regarding the overall anticoagulation quality. Under the RL algorithm’s guidance, the rate of excessively high INRs was significantly reduced, the proportion of patients achieving the target range at discharge was significantly increased, and the overall INR trajectory reached and maintained within the target range significantly faster and longer. This is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of using RL to tackle the dynamic decision-making tasks of warfarin dosing in the immediate post-operation setting using real-world patient data.

Previous works in assisting warfarin dosing mainly centered on predicting the optimal initial or maintenance dosage by constructing multivariate linear models30–32 or AI/ML models with patients’ static variables.33–35 However, this approach has not been proved to be practical or improve clinical outcomes.36–38 The main issue of this prediction approach is that it did not reflect the actual warfarin dosing decision-making process. In practice and as guidelines suggested,4,7 clinicians decide the warfarin dosage primarily based on the observed dynamic warfarin-INR response patterns, with additional consideration of patient-specific static characteristics (eg, age, weight). Also, this one-dose prediction offers little clinical support in actual practice, as clinicians still need guidance on how to better adjust dosages in the process between the initial and maintenance dosage.

Traditional prediction approaches are often burdensome and impractical as clinical decision support for complex dynamic decision process. Many sequential decision-making tasks in clinical practice can instead often be solved as multistage optimization problems. Extending from its broad application in nonmedical sectors (eg, self-driving cars, gaming, market trading), RL has emerged as the preferred strategy with its model-based or model-free versatility and computational efficiency for high-dimensional sequential problems. By sequentially solving each sub-task, RL can offer solutions that optimize the ultimate outcomes for many dynamic, uncertain clinical situations, like post-operation warfarin dosing. For the dynamic decision process in the current study, we employed a model-free offline-trained RL algorithm approach. Although there are other dynamic modeling strategies, including model-based strategies (eg, model predictive control,39 linear control system40) that require full knowledge or complete modeling of target systems, and model-free online strategies (eg, evolutionary algorithm41) that require direct interaction with target systems, they are less suitable for the current study, considering the complexity of human body system for warfarin response and our retrospective study design.

Compared with previous RL studies, our current approach had several advantages and implications for using RL in clinical settings: (1) a deep neural network was used to more efficiently approximate the expected reward returns for complex clinical scenarios such as warfarin dosing that consists of tremendous amounts of possible states. Whereas RL algorithms from previous studies mainly using policy or value iteration were limited to more simplistic clinical scenarios.12–19 (2) a conservative Q-learning strategy was used to mitigate the common out-of-distribution problems in offline/retrospective RL studies (ie, situations unseen in training could lead to inappropriately unsafe recommendations by the algorithm during external testing). This is particularly important for high-stake domains like healthcare. (3) our RL algorithm was trained from a large retrospective, offline data set and safely tested in the patient representatives. This approach enabled direct evaluation of algorithm performance on important clinical metrics (eg, INRs) instead of terms like the expected reward returns that are often hard to comprehend by clinicians, and the predicted patient responses can be more convincing as it was obtained from actual real-world experience, rather than through theoretical simulation.

Potential clinical utility of RL-assisted clinical support tools includes: (1) the interactiveness property of RL could enable flexible interaction between clinicians and the algorithm in practice, as the algorithm can continuously receive the latest patient input information and offer output recommendations in return. This guarantees timely, constant support for clinicians when dealing with complex dynamic decision-making problems. (2) the practicality of RL algorithms can be achieved by either being integrated into the hospital EHR system as clinical decision support tools that could automatically capture patients’ latest metrics and make the next recommendation, or incorporated at the point-of-care to facilitate ambulatory patient management. A possible example of the latter could be using RL algorithms to assist the long-term warfarin patient self-management, where previous studies have shown promising results of improved anticoagulation quality but are limited due to concerns over patient guidance and cost-effectiveness.42–44 (3) the scalability of RL algorithms to different clinical tasks could be efficiently achieved by retraining or transfer learning. This generally requires algorithm adjustment with new training data collected from other clinical scenarios. Overall, in the context of personalized medicine, the RL-assisted approach could further extend the scope of individualized treatment into a time-varying care mode, offering more adaptive treatment recommendations and potentially leading to better outcomes.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, the current RL algorithm was developed in a single-center patient cohort of Chinese descent and only validated in a more recent patient population. Potential temporal changes in practice patterns might also exist. Thus, the generalizability of the current RL algorithm to different healthcare systems or patient populations remains unknown and should be further externally validated in multi-center, diverse patient populations. Second, differences existed in the warfarin management standards between the current study and Western practice. Due to the generally lower anticoagulation intensity in Eastern practice, the INR thresholds were much lower than those recommended in the Western guidelines.4,5,7 This could also affect the algorithm generalizability, and therefore further training and external validation with patient populations in Western practice are needed. Also, the proportion of patients with on-target INRs at discharge in our practice might be relatively low. Sensitivity analysis with a wider INR target range of 1.5–2.5 showed that the RL algorithm still outperformed the clinicians’ guidance (Supplementary Table S7). Third, it is not completely clear whether and how the warfarin metabolism genotype information will affect the RL algorithm performance, given their relatively low availability in the current study. Therefore, further evaluation in patients with warfarin genotype information is needed. Fourth, the INR response under algorithms’ guidance was predicted using kNN. The validity of algorithm performance should be ascertained in future prospective studies with actual patient responses. Given the complexity of the human body system, intricate patient responses (eg, real-time INR response) are often difficult to simulate with traditional parametric approaches (eg, using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models45,46), The nonparametric prediction methods (eg, kNN) based on actual patient responses, may be more appropriate.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we developed a RL algorithm that significantly optimized the dynamic in-hospital warfarin dosing process in patients after SVR in comparison with clinicians’ actual practice, with the rate of excessively high INRs markedly reduced, on-target INRs at discharge significantly increased, and the overall INR trajectory reaching and maintained within the target range significantly faster and longer. Our work illustrated the potential of RL in improving treatment efficacy and safety for challenging clinical scenarios characterized by extensive sequential decision-making, great uncertainty, and individualization. This interactive RL framework could potentially be implemented as a clinical decision support system or integrated into the point-of-care and adaptable to other scenarios. Future studies to rigorously evaluate algorithm performance through broad external validation, prospectively test the clinical benefit in clinical trials, and further explore the clinical utility in varied settings are warranted.

FUNDING

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of People’s Republic of China (2016YFC1302001), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (D171100002917001), and the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH; No. 2016-1-4031), all to ZZ. This study was also supported by the grant from the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-GSP-QN-10), to SL. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ZZ, XYJ, and SL conceived the overall study. JTZ and SL designed the experiments. JTZ, XTS, and YZ performed the data acquisition, extracting, and cleaning. JZS, HCZ, XCL, and JTZ performed the data processing, and conducted the experiments. HCZ and JZS designed and implemented the algorithm. JTZ and XTS analyzed the data. XYJ and ZZ directed the project. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and JTZ drafted the final manuscript, which was reviewed, revised, and approved by all authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xu Wang at the Information Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases for help with data acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Contributor Information

Juntong Zeng, National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Jianzhun Shao, Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Shen Lin, National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Hongchang Zhang, Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Xiaoting Su, National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Xiaocong Lian, Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology (BNRist), Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Yan Zhao, National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Xiangyang Ji, Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology (BNRist), Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Zhe Zheng, National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine, Fuwai Central-China Hospital, Central-China Branch of National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to patient privacy and human participant data regulation. All data was stored on the secured cloud server within the Fuwai hospital system and was approved for research purposes in Fuwai hospital only. Any external use requires additional consent and ethical approval from Fuwai hospital IRB. The data could be shared on reasonable request made to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tsiatis A, Davidian M, Holloway S, et al. Dynamic Treatment Regimes: Statistical Methods for Precision Medicine. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lavori PW, Dawson R.. Adaptive treatment strategies in chronic disease. Annu Rev Med 2008; 59: 443–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chakraborty B, Murphy SA.. Dynamic treatment regimes. Annu Rev Stat Appl 2014; 1: 447–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2021; 43 (7): 561–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2017; 135 (25): e1159–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, et al. US emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events, 2013–2014. JAMA 2016; 316 (20): 2115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012; 141 (2 Suppl): e152S–e84S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med 2019; 25 (1): 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson KW, Torres Soto J, Glicksberg BS, et al. Artificial intelligence in cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71 (23): 2668–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Recht B. A tour of reinforcement learning: the view from continuous control. Annu Rev Control Robot Auton Syst 2019; 2 (1): 253–79. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sutton R, Barto A.. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu C, Liu J, Zhao H.. Inverse reinforcement learning for intelligent mechanical ventilation and sedative dosing in intensive care units. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019; 19 (Suppl 2): 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Komorowski M, Celi LA, Badawi O, et al. The Artificial Intelligence Clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat Med 2018; 24 (11): 1716–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Escandell-Montero P, Chermisi M, Martínez-Martínez JM, et al. Optimization of anemia treatment in hemodialysis patients via reinforcement learning. Artif Intell Med 2014; 62 (1): 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pineau J, Guez A, Vincent R, et al. Treating epilepsy via adaptive neurostimulation: a reinforcement learning approach. Int J Neural Syst 2009; 19 (4): 227–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shortreed SM, Laber E, Lizotte DJ, et al. Informing sequential clinical decision-making through reinforcement learning: an empirical study. Mach Learn 2011; 84 (1–2): 109–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parbhoo S, Bogojeska J, Zazzi M, et al. Combining kernel and model based learning for HIV therapy selection. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2017; 2017: 239–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Y, Zeng D, Socinski MA, et al. Reinforcement learning strategies for clinical trials in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Biometrics 2011; 67 (4): 1422–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oroojeni Mohammad Javad M, Agboola SO, Jethwani K, et al. A reinforcement learning-based method for management of type 1 diabetes: exploratory study. JMIR Diabetes 2019; 4 (3): e12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zheng H, Ryzhov IO, Xie W, et al. Personalized multimorbidity management for patients with type 2 diabetes using reinforcement learning of electronic health records. Drugs 2021; 81 (4): 471–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 2011; 123 (23): 2736–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bennett CC, Hauser K.. Artificial intelligence framework for simulating clinical decision-making: a Markov decision process approach. Artif Intell Med 2013; 57 (1): 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alagoz O, Hsu H, Schaefer AJ, et al. Markov decision processes: a tool for sequential decision making under uncertainty. Med Decis Making 2010; 30 (4): 474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu Z, Zhang SY, Huang M, et al. Genotype-guided warfarin dosing in patients with mechanical valves: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 106 (6): 1774–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee H, Kim HJ, Chang HW, et al. Development of a system to support warfarin dose decisions using deep neural networks. Sci Rep 2021; 11 (1): 14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma W, Li H, Dong L, et al. Warfarin maintenance dose prediction for Chinese after heart valve replacement by a feedforward neural network with equal stratified sampling. Sci Rep 2021; 11 (1): 13778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Y Tao Y, Chen YJ, Fu X, et al. Evolutionary ensemble learning algorithm to modeling of warfarin dose prediction for Chinese. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2019; 23 (1): 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu R, Li X, Zhang W, et al. Comparison of nine statistical model based warfarin pharmacogenetic dosing algorithms using the racially diverse International Warfarin Pharmacogenetic Consortium cohort database. PLoS One 2015; 10 (8): e0135784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Z. Introduction to machine learning: k-nearest neighbors. Ann Transl Med 2016; 4 (11): 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med 2009; 360 (8): 753–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wadelius M, Chen LY, Lindh JD, et al. The largest prospective warfarin-treated cohort supports genetic forecasting. Blood 2009; 113 (4): 784–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gage BF, Eby C, Johnson JA, et al. Use of pharmacogenetic and clinical factors to predict the therapeutic dose of warfarin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008; 84 (3): 326–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gu ZC, Huang SR, Dong L, et al. An adapted neural-fuzzy inference system model using preprocessed balance data to improve the predictive accuracy of warfarin maintenance dosing in patients after heart valve replacement. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021; doi: 10.1007/s10557-021-07191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li X, Liu R, Luo ZY, et al. Comparison of the predictive abilities of pharmacogenetics-based warfarin dosing algorithms using seven mathematical models in Chinese patients. Pharmacogenomics 2015; 16 (6): 583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Truda G, Marais P.. Evaluating warfarin dosing models on multiple datasets with a novel software framework and evolutionary optimisation. J Biomed Inform 2021; 113: 103634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verhoef TI, Ragia G, de Boer A, et al. ; EU-PACT Group. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. N Engl J Med 2013; 369 (24): 2304–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kimmel SE, French B, Kasner SE, et al. ; COAG Investigators. A pharmacogenetic versus a clinical algorithm for warfarin dosing. N Engl J Med 2013; 369 (24): 2283–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, et al. Randomized trial of genotype-guided versus standard warfarin dosing in patients initiating oral anticoagulation. Circulation 2007; 116 (22): 2563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Camacho EF, Bordons C.. Model Predictive Control. London: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Datta BN. Numerical Methods for Linear Control Systems. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moriarty DE, Schultz AC, Grefenstette JJ.. Evolutionary algorithms for reinforcement learning. jair 1999; 11: 241–76. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heneghan C, Alonso-Coello P, Garcia-Alamino JM, et al. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2006; 367 (9508): 404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heneghan C, Ward A, Perera R, et al. , Self-Monitoring Trialist Collaboration. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2012; 379 (9813): 322–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Connock M, Stevens C, Fry-Smith A, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of managing long-term oral anticoagulation therapy: a systematic review and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11 (38): iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fusaro VA, Patil P, Chi CL, et al. A systems approach to designing effective clinical trials using simulations. Circulation 2013; 127 (4): 517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hamberg AK, Dahl ML, Barban M, et al. A PK-PD model for predicting the impact of age, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 genotype on individualization of warfarin therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 81 (4): 529–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to patient privacy and human participant data regulation. All data was stored on the secured cloud server within the Fuwai hospital system and was approved for research purposes in Fuwai hospital only. Any external use requires additional consent and ethical approval from Fuwai hospital IRB. The data could be shared on reasonable request made to the corresponding author.