Abstract

Racism is an established health determinant across the world. In this 3-part series, we argue that a disregard of how racism manifests in pain research practices perpetuates pain inequities and slows the progression of the field. Our goal in part-1 is to provide a historical and theoretical background of racism as a foundation for understanding how an antiracism pain research framework - which focuses on the impact of racism, rather than “race,” on pain outcomes - can be incorporated across the continuum of pain research. We also describe cultural humility as a lifelong self-awareness process critical to ending generalizations and successfully applying antiracism research practices through the pain research continuum. In part-2 of the series, we describe research designs that perpetuate racism and provide reframes. Finally, in part-3, we emphasize the implications of an antiracism framework for research dissemination, community-engagement practices and diversity in research teams. Through this series, we invite the pain research community to share our commitment to the active process of antiracism, which involves both self-examination and re-evaluation of research practices shifting our collective work towards eliminating racialized injustices in our approach to pain research.

Keywords: Racism, antiracism, pain disparities, critical race theory, cultural humility, pain inequities

In the past year, there has been a growing consensus regarding the need for health practitioners and researchers to actively stand against racism to overtly acknowledge, address, and ameliorate the effects of racism on health and well-being.16,24,52,77 This movement and growing concern has been motivated by events in the United States (US), including the murder of George Floyd, ongoing police brutality against Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities, a stark increase in hate crimes against Asian American communities, and the systematic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and well-being of racialized groups.3,93 We will use the term “racialized groups” throughout this series, instead of acronyms or groupings such as “racial minorities” or Black and/or Indigenous and/or People of Color (BIPOC), to specifically acknowledge that these identity categories are socially and politically constructed labels imputed to individuals as a way of creating social hierarchies.42 In doing so, the dominant group in a specific society connotes hierarchical valuations of worth (often emphasizing phenotypical and cultural differences).8,84,86,87 The recent events highlighted above are the product of centuries of systematic injustices and oppression affecting racialized groups that bring our attention once again to the urgent need to advance racial justice.49

The process of racialization (Table 1 for definition) is dynamic and attached to status and unequal power between groups, thereby highlighting experiences of oppression.84,95 Racialization is not static because it involves changing practices that link racialized meanings to people based on what the dominant group finds valuable. This source of oppression occurs in many countries. In most cases, this oppression is caused by deeper racist histories experienced by specific groups as a result of colonization and post-colonial social relations among its members. For example, in the US, immigrants from European ethnic groups (eg, Irish, Ashkenazy Jewish, Greek, Italian, and Eastern European) were all at some time considered “non-White” by White people in power and thus were subject to the process of racialization. However, once the dominant group reclassified individuals from these nationalities as “White” in the 20th century, they became less marginalized and gained more power and privileges of Whiteness.48

Table 1.

Explanations of Common Language Choices in Scientific Narratives and a Commonly Used Underlying Research Framework in Pain Research With Proposed Shifts Based on an Antiracism Framework

| Common Approach |

Proposed Shift* |

Rationale for Shift | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Term | Definition | Key Term | Definition | |

| Common Underlying Research Framework | ||||

|

| ||||

| Non-Racism | The passive rejection, opposition, and disassociation from behaviors, discourses, and ideologies that are considered racist | Antiracism | The active process of eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices, and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably | Calls on investigators to actively build cultural humility, self-reflect on study design choices, and engage in power-sharing and other behaviors that will bring the field of pain closer to justice for racialized groups |

|

| ||||

| Common Language Choices in Scientific Narratives | ||||

|

| ||||

| Race/Racial | Social classification of individuals based on a mix of physical features (eg, skin tone and hair texture) | Racialized identity or racialized group identity when referring to racialized groups; “Race” (in quotations) when referring to White people or the general construct | A social process by which racialized meaning is ascribed to a group of individuals that previously did not identify as such; historically, White Europeans racialized individuals who did not have similar physical features to their own, leading to “othering” and differential treatment; because White people initiated the process of racialization, in our series, we do not refer to White people as being racialized | Indicates the action of White European societal and structural influences in creating and perpetuating racialized groups and hierarchies based on those groups (ie, acknowledges the sociopolitical process) rather than implying distinct classes of people (ie, might be inferred as biologically based); We use quotation marks around the term “race” where relevant to connote that it is a socially constructed, dynamic phenomenon |

| Minority | A distinct group that coexists with, but is subordinate to, a more dominant group | Minoritized | Group(s) in society that are defined as “minorities” by a dominant group | While used by some to denote minority percentage of the population, this term has taken on connotation that that racialized groups are relegated to a “minority” status by White dominant society |

| Social Determinants of Health | The conditions in the environments where people are born, live, work, play, and age that affect health, functioning, and quality of life that ultimately lead to poor health outcomes | Social Indicators of Health | An imperfect replacement term that seeks to emphasize social factors that contribute to health outcomes while moving away from deterministic language (see Salerno & Bogard, 2019) | Indicates that conditions are not fixed and can change across the lifespan, be surpassed because of resilience factors, or change with intervention |

| People of Color, BIPOC, non-White | Naming conventions typically used to refer to racialized groups | Use individuals’ preferred identities or “racialized group(s)” | For example, “Black” or “African American” or “Jamaican American” when referring to a particular identity; “Racialized groups” can be used when referring to individuals spanning more than one pan-ethnic category | Rather than passively cluster pan-ethnic identities – which erases their heterogeneity – using individuals’ preferred identity is a step toward recognizing unique lived experiences, and using “racialized” actively acknowledges the reason for lumping these groups together |

Abbreviation: BIPOC, Black, Indigenous, People of Color.

Because semantic change occurs continually, the utility of these proposed shifts should be closely monitored over time. As needed, new terms that hold systems accountable and validate the experiences of racialized individuals should be used.

The advantages of being White and the marginalization of dark-skinned individuals is observed worldwide. For instance, because of colorism, many individuals from Asian cultures are exposed to caste-discriminatory exclusion and ethnocentric prejudice.12,99 In Latin America, skin-color prejudice is observed when there is a preference for partners with light skin tones and more European phenotypes (ie, “mejorando la raza” or “improving the “race”); thus, within-group oppression is again driven by the power and status associated with Whiteness.1,23 It is also worth noting that specific categories can change, and their content and implications vary by time and place. Hence, these examples are insufficient to illustrate the ongoing multidimensional practices that attach racialized meaning to people and the heterogeneity of experiences with racism and prejudice affecting racialized communities.

At the forefront, racism has been identified as the fundamental root cause of racialized health inequities, often the primary reason underlying uneven access to care,6,107 differences in quality of care,65,94 and an array of health factors, including disparities in pain outcomes.2,70,79,101 Hence, unequal allocation of power and resources among other systems of oppression limits the opportunities to achieve optimal health by all individuals. For pain researchers, addressing justice for racialized groups means identifying and confronting racism to achieve equal care for all individuals living with pain. Each pain investigator - not just those primarily focused on pain disparities - can become personally accountable for addressing the inequitable experiences caused by racism that lead to racialized pain disparities. As discussed in greater detail below, racism reflects a system of deep-seated inequities created by social structures, policies and practices. Racism also encompasses overt antagonism, prejudice, and discrimination against racialized individuals or groups,22,38,67,84 as well as the more subtle reactive states of uneasiness, discomfort and fear, which can motivate an unwillingness to acknowledge prejudiced attitudes and beliefs within oneself.7,102

The Role of Pain Researchers in Advancing Justice for Racialized Groups

Research plays a powerful role in underscoring how racism manifests in pain outcomes and ultimately impact individuals’ livelihoods. For example, many research studies, case reports, and reviews have identified the impact of racism (often documented as implicit bias, stereotypes, myths, etc.) on pain management.19,53,54,76,79,81,105 A 2016 study conducted in the US documented the presence of false beliefs (eg, Black people have thicker skin with fewer nerve endings and feel less pain) among medical trainees that echo narratives used throughout US history as justification for painful abuse during and after slavery.54 There is also evidence that pain-specific biases,5 independent of more general attitudes and beliefs about racialized groups, contribute to racialized disparities in pain treatment. Experimentally, implicit visual or verbal cues revealing a patient’s “race” result in differential detection of or belief in a person’s pain.75,80,85 It is widely documented that racist cultural stereotypes contribute to differences in pain tolerance based on racialized identity.74,100,105 Provider bias is also a frequently examined determinant of inequitable pain treatment.41,53,83 In fact, underdiagnosis and undertreatment of pain are prominent for racialized individuals in clinical and experimental settings. For example, a 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis found that Black individuals were less likely to receive an opioid prescription than Non-Hispanic White (NHW) individuals for the same type of pain.78

Patients suffering from chronic pain are already more likely to be stigmatized, marginalized, and experience psychosocial sequelae secondary to their pain condition.29,45,73,76,79 People from racialized groups with chronic pain face additional injustice76; not only experiencing a greater burden of pain and disability, but also inadequate pain treatment despite the greater need.18,45,51 Such inequity is exemplified in sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder. Sickle cell disease is an example of racialized condition due to its higher prevalence among people whose ancestors were from sub-Saharan Africa, India, Saudi Arabia and Mediterranean countries and the differential treatment experienced by this population. Undoubtedly, sickle cell disease pain (ie, vaso-occlusive) episodes are painful, but research in the US has demonstrated that patients with sickle cell disease experience invalidation by medical professionals,18,62 wait 50% longer to be seen by physicians than patients with long bone fractures,51 and report experiencing high levels of racialized discrimination.50,73,104 Furthermore, sickle cell disease research receives less than half of the federal funds per patient compared to cystic fibrosis - a similarly rare chronic disease with a high prevalence of people of Northern European descent.37These findings underscore the urgent need to develop new research paradigms that account for the noxious impact of racism and its correlates to advance pain care for racialized individuals.

In pain science, our commitment to interrogating racism in how our research is conceptualized, conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated is a collective responsibility that is fundamental to improving the pain care of all individuals. This also means recognizing the importance of engaging people with lived experiences of racism and pain, as well as advocates, community members, and practitioners to be more effective at identifying knowledge gaps. Furthermore, the collaborative approach will allow us to truly interrogate the multidimensionality of pain and its associated outcomes in both pre-clinical and human-participant research. The significant benefits of partnering with community members have been widely documented and recognized. For example, at the national level in the US, the N.I.H. Heal Community Partner Committee (HCPS), composed of patients, advocates, patient liaisons and family members of those living with pain, foster dialogue in shaping community-responsive research priorities. Over the years, the implementation of these models into pain research has been rapidly growing, including as a recommended approach to increase the inclusion and engagement of understudied and diverse populations into pain research.61 For many who conduct pain research, an antiracism stance that includes the input and advocacy of patients should also be considered a measure of “good science” and an ethical responsibility as enforced by our respective disciplines (eg, APA Ethics Code, AMA Ethics Code).22,67

Antiracism Framework

Our 3-paper series titled “Confronting Racism in Pain Research” is informed by the efforts of the Antiracism CoaliTION in Pain Research (ACTION-PR; also informally known as the Pain Justice League), a group of pain researchers (co-authors in the series) with expertise in pain inequities, clinical pain research, basic science, and translational research who envisioned a need for change in pain research to address racism. Our group’s full efforts in generating this series are discussed below under “A Call to Action: Introducing an Antiracism Approach to Pain Research.” We use a 3-part series format, rather than a single paper, to comprehensively review the entrenched history of racism in the field of pain, highlight how the ACTION-PR developed, promote guides for antiracism practices in pre-clinical and human-participants research, and discuss the persistent inequities in the conduct of research and the academy. Given the complexities of the topic, a 3-part series is arguably too short.

Across our series, we utilize an antiracism framework, which seeks to identify, challenge, and act to eliminate racism, and we have adapted it specifically for pain research. Within this framework, the equal humanity yet unequal effects of racism on racialized groups is capitalized, which helps investigators remain cognizant of health equity throughout the research process and acknowledges that racism is the reason for health inequities across racialized groups.24,39,65,94 As noted previously, even well-meaning individuals can perpetuate racism when there is a lack of critical self-awareness and understanding of racialization,32,102 including how anti-Black attitudes (types of racism towards Black individuals) manifest across the world. Thus, authors, reviewers, editors, and consumers of research findings, must proactively reflect on ways that racism can pervade ideologies, behaviors, and scholarship, especially as it pertains to studying the lived experiences of racialized individuals and our documentation and dissemination of findings (see Hood et al., this issue, for a more detailed explanation).56

By utilizing an antiracism framework, we can begin to interrogate and recognize the many forms of racism and non-racism (ie, passive opposition of racism without active change in the attitudes or behaviors) that show up in our work (from attitudes to behaviors and practices). In doing so, we can begin to create change and attempt new approaches that move beyond conducting studies that enroll mostly middle-class and White participants to understand pain inequities “to a more inclusive research agenda that helps us understand the role of racism in the pain experience”. For example, in pre-clinical studies, researchers could employ assays that measure psychosocial aspects of pain or develop behavioral models to illustrate social indicators contributing to pain inequities (see Letzen et al., this issue, for application of an antiracism framework to pre-clinical and translational research designs).68 Throughout the series, we will attempt to illustrate how an antiracism framework is applied across pain research. Although we are far from having all the answers, it is our intention for every researcher to consider how our guides could be applied to their work.

To start, in part-1 of the series, we will review historical events and definitions to understand how “race” is constructed, leads to racism, and generates health disparities, including pain-related outcomes. Then, to acknowledge how racism occurs, contributes to justified medical mistrust, and consequently perpetuates obstacles to equal opportunity and justice, we will describe Critical Race Theory (CRT)38 and its implications for our proposed antiracism framework in pain research. Finally, we will share information about the ACTION-PR’s efforts that lead to this series and describe the importance of cultural humility, which is the lifelong process of self-exploration and willingness to learn from people who have different experiences from our own and to recognize and address our own biases. Lastly, the included positionality statement illustrates how the author’s identities and experiences shaped the writing of the series and the limitations encountered by the ACTION-PR in learning and introducing an antiracism framework in pain research.

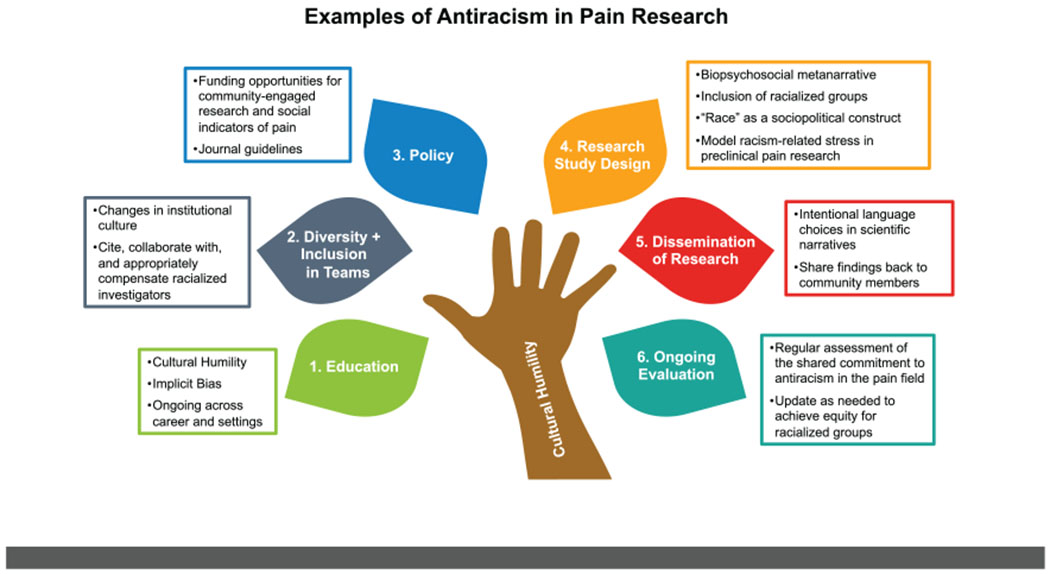

As seen in Figure 1, the proposed framework supports cultural humility as the foundation for applying an antiracism framework in pain research. Through self-reflection at every stage of the research process, we can begin to question, learn, and examine our current approaches. As a result, we call on all pain researchers to disrupt old ways of thinking and apply these concepts as they question racism and/or non-racism and create opportunities for action. We also recognize that our urging will not result in change without first preparing all readers with the foundational knowledge and understanding of the theories explaining the sociopolitical construct of “race” and racism that have been appreciated in fields beyond biomedical research (ie, cultural anthropology).46 Building on this knowledge, we have included a list of key terms in Table 1 to illustrate how an antiracism framework can be applied to the common underlying framework in the field of pain (ie, non-racism) as well as language in scientific narratives that are commonly used in our research to advance the field. Although we cannot include every term in the literature or the numerous factors that contribute to pain inequities, we have focused on racism as the root problem that must be addressed to help dismantle and rebuild our research approaches that were created in structurally unjust systems and methods to improve current practice; therefore, we have reiterated these concepts and definitions across the 3-paper series.

Figure 1.

Shared commitments for antiracism in pain research.

In the remaining papers, the primary goal is to propose how the field of pain might incorporate antiracism in our research and promote solutions by facilitating critical thought that addresses specific aspects of the research process. Part 2 of this series discusses the tension between science and pre-clinical basic science and antiracism reframes for these design choices with options for investigators to consider. Finally, Part 3 of the series calls for a shared commitment from pain scientists to diversify our research environments (eg, teams, departments, institutions), engage racialized groups in pain research by shifting towards a more community-based research process, and change our recruitment and retention methods to improve diversity in our samples and increase the generalizability of findings. Alongside these changes, Part 3 also proposes a significant shift in our dissemination methods, including the language and terminology used, how we interpret and distribute our findings outside traditional silos with involvement from community members.

We want to emphasize that this series is a critical step towards addressing inequities and disparities in pain. As noted above, it does not include all of the answers to eliminate racialized pain inequities, and the information discussed should not be applied in a “one size fits all” manner. Innovative approaches to pain science and clinical practice would be more impactful if all stakeholders in the field of pain, not just researchers focused on pain inequities, accept shared responsibility and commit to antiracism in their actions wherever possible. Given the current inequities, change must begin immediately, and our series proposes how this change can start. However, we understand that these changes in research praxis will continue to evolve as we learn new information and as researchers gain the necessary skills to prioritize antiracism, cultural humility and ongoing education. By initiating and sustaining discussions within the pain research community (particularly centering on the lived and pain experiences of racialized individuals-including the perspective of racialized investigators), we can steadily shift the impact of our collective work to benefit all communities.

Racialization, “Race”, and Racism

The Meaning of “race”

As described above, racialization is the dynamic, sociopolitical process by which “racial” categories are assigned to groups of people.86,95 Depending on the point in history and society in question, different groups of people might be racialized differently from today88,89 [for an anthropologic history, see Smedley & Smedley].95 “Race” was sociopolitically constructed as a physico-biological concept that categorizes people based on overt physical features, such as skin color, nose shape/size, and skull size. These features were used to distinguish individuals by the geographic origin of their ancestors, resulting in the racialization of individuals, for example, as Black and/or African American in the United States, British Asian in the United Kingdom, and American Indian or Alaska Native in North America. However, despite this conceptualization, to be clear, there is no genetic basis of “race.” As W.E.B. Du Bois argued over 100 years ago, “race” is not a biological entity or an explanation for categorizing discrete groups into “Whites” or “Blacks” to understand disparities in health outcomes; instead, he advanced the notion that is a sociocultural (sometimes historical and political) factor conceptualized to give a dominant group (typically, people racialized as White) a privileged position in social standing.43 Thus, contemporary investigators view “race” as a social construct.4,96 Causing most harm, the utilization of these social classifications as biological variables perpetuates racism. For example, despite acknowledging that human genetic variations do not constitute biological differences across “races,”69,95 the use of “race” as a categorization to understand human bio-diversity remains; thereby encouraging the false belief that “race” is a genetic category and adding to the perpetuation of negative stereotypes and racial inferiority across groups. However, “race” is a concept with social meaning, and contemporary investigators should clearly define and conceptualize “race” as a sociopolitical construction that may profoundly impact the pain experience of racialized individuals.4,96

“Race” and ethnicity are often ignored, underreported, or left unexplored in pain research. When “race is reported, it is commonly controlled for, or alternatively, used in pain research to assess pain disparities. Participants in the US are commonly asked to select their “race” based on federally recognized categories established by the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB): White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander, and Some Other “race.” In addition to these federal “racial” categories that are sociopolitically constructed and imposed into specific groups, sociological evidence suggests that Middle Eastern and/or North African and Hispanic and/or Latinx individuals – particularly those who do not have phenotypic features traditionally associated with European or African ancestry – are uniquely racialized in US society.13

“Race” and ethnicity are separate from genetic ancestry, which is the set of genealogical paths through which an individual’s genome has been inherited.72 Unlike “race” that has no biological significance but predominantly categorizes individuals based on phenotypic characteristics for hegemony, genetic ancestry focuses on understanding how genetic drift, migration, and natural selection affect the unfolding of an individual’s history and reflects the fact that human variation is linked to the geographical origins of their ancestors. Ethnicity, on the other hand, reflects a multidimensional construct of phenotypic features, geographic origin, and sociocultural factors (eg, norms, customs, beliefs, and traditions) among individuals who may or may not share common ancestry.82 This conflation of “race” and ancestry is exemplified in the misguided conceptualization of sickle cell disease as a “Black disease.” Sickle cell trait (inheritance of 1 sickle cell gene from parents) is protective from some strains of malaria,103 a potentially deadly mosquito-borne infectious disease endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. This malaria resistance means more people in sub-Saharan Africa have sickle cell trait, and although sickle cell disease is a recessive disorder where, without treatment, most people do not make it out of childhood, the sickle allele remains in the population. This is the distinction between ancestry (ie, having origins from one place where sickle cell trait was protective) versus “race” (people from sub-Saharan African have darker skin color and are racialized as Black). In pain research, the practice of grouping individuals into a “non-White” or “other race” category perpetuates racism by oversimplifying diversity, discrediting or dismissing how an individual identifies and implying that Whiteness is the societal norm.

Forms of Racism

Many definitions of racism have been suggested, all centering around unfairness, unequal power, and oppression and/or dominance among groups of people.10,17–24 In their seminal work, Clark and colleagues defined racism as “the beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation.”25 In other words, racism is a racial hierarchy that deems racialized groups inferior (and White people as superior), supported by institutional practices and societal norms. As mentioned above, this hierarchy occurs globally (because of racialized categories or colorism) and leads to unfair distribution of power, resources, opportunities, and privileges based on ethnic, racialized identity, religious, or sociocultural differences. Such privileges include rights and opportunities, economic rewards, and psychological protection through a political alliance with institutional power and law enforcement.43

Racism spans structural (systemic or institutional), interpersonal, and intrapersonal (internalized) levels.10 Conceptually, structural racism refers “to the normalization and legitimization of an array of dynamics-, historical, cultural, institutional and interpersonal – that routinely advantage White people in many parts of the world while producing cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color.”24 Structural racism leads to processes, policies, and practices that maintain racial hierarchy and produce health inequities.10,24 Among individuals, interpersonal racism can manifest as interracial (between individuals of 2 different groups) or intra-racial (between people of the same racialized group) racism.10 These interpersonal forms of racism are the most obvious and acknowledged type of racism. However, internalized racism – defined as the internalization of racist stereotypes, norms, values, ideas, and behaviors perpetuated by the White dominant society to support racism – is one of the major effects of racism.31 Like systemic racism, internalized racism is not readily seen; racialized individuals can unconsciously support and get rewarded for supporting White hegemony.31,60 Irrespective of the level of occurrence, racism is perpetuated by unfairness, dominance, repression, stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminatory behaviors, all of which contribute to racialized disparities in pain outcomes (see Letzen et al., this issue, and Hood et al., this issue, in the series for examples).56,68 Employing an antiracism framework in pain research will enable us to acknowledge the impact of racism and change discriminatory practices that promote inequities in pain care.

The Impact of Racism

The primary reason for focusing on racism as the root cause of health disparities is that racism or the perception of environmental stimuli as racist causes tremendous physiological and psychological stress, known to affect disease risk. In addition to direct and overt effects, racism also causes inequities in upstream factors that further exacerbate health disparities, such as the impact of racism socioeconomic, environmental, demographic, behavioral, existing (patho)-physiological, and coping mechanisms. One mechanism by which racism can affect health outcomes is epigenetics. In fact, epigenetics modifications are the mechanisms by which environmental stimuli (including political, sociocultural, economic) influence biological function by regulating gene expression without altering the DNA sequence.4,34 This means that “the social and political world is incorporated into the muscles, hormones, fluids, tissues, and chemicals of human bodies” and passed on from generation to generation.34 These differential expressions of genes may represent underlying mechanisms that cause and sustain racialized disparities in pain.4

The significant impact of racialized discrimination in the experience of pain and pain treatment are well documented.96 Further, racialized discrimination is a risk factor for pain and opioid misuse.4 Studies documenting the impact of discrimination typically compare racialized group(s), primarily those self-reporting as Black or African American, to White participants. Although these comparisons are useful to better understand disparities and inequities, most, likely inadvertently, have placed a value system on racialized identity and neglect to measure or describe the proximal mediators, relevant structural or social factors, systems, policies and practices that may influence outcomes9,19,33,63,66,79,81,83,97 See Letzen et al., this issue, for further review.59 Moreover, the variability in how racialization affects each group (ie, colorism, antiblack attitudes) is overlooked, and subsequently, the intra-group variability in the pain experience goes unnoticed. For instance, Black Americans are not genetically identical and do not share the same lived experiences yet are frequently categorized in pain research into a singular group without respect of genetic and social variability. That racialization missed the implications of the unique lived experiences of darker skin (relative to lighter skin) or US-born (relative to being born in Africa) African Americans.

The impact of racism is perhaps most profoundly understood by considering the mistreatment of racialized individuals in medical research. Medical practice is entrenched with exploitation, marginalization, oppression, violence, and involuntary experimentation of Black people. From the exhumation of buried Black bodies for dissection, involuntary collection and storage of body parts, to painful experimentation without anesthesia and involuntary sterilization, medical mistreatment has violated the public trust in medical and academic research and demonstrated a singular devaluing of Black bodies.92

In the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” which began in 1932 in the US, Black men were deceived about their diagnosis and deprived of the standard of care (life-saving penicillin treatments for syphilis), which resulted in additional infections and death of family members. This violation was perpetrated by investigators but also by many other authority figures who were complicit in this atrocity, including the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Medical Association, and National Medical Association, who endorsed the study.90 We can often think of the Tuskegee study as historical, from a bygone era without ethical safeguards in the research community.64 However, it is critical to understand that this study continued well after the establishment of the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki – both requiring informed consent and justice, which continued to be violated in the ongoing Tuskegee study.

Another example of the disregard for the autonomy and agency of Black people in medical research is the story of Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman in the US whose cervical cancer cells were collected, analyzed, cultured, and distributed without consent. These cervical cancer HeLa cells (HeLa from the first 2 letters of her first and last name) were the first human cells to be cultured for use in medical research.71 The Lacks family was not made aware of the line’s existence until 1975, whilst others profited both financially and professionally from their sale and distribution.58 Apologies and remuneration for these injustices were slow and hard won. Ultimately, mistreatment from medical providers, institutions, and government organizations have done significant harm to healthcare utilization and research participation by Black communities.

Modern medicine continues to exploit knowledge gained through unethical means. Between 1990 and 1994, members of the Havasupai Tribe provided blood samples to examine the genetic link to diabetes as part of a study led by researchers at the Arizona State University in the US. A lawsuit was filed upon discovery that DNA samples were also used to examine genetic links with mental health disorders, ethnic migration, and population inbreeding, taboo topics in the Havasupai tribe. Such evidence of the deliberate misuse of genetic samples undermines trust in medical researchers, particularly among Indigenous communities who value DNA as deep cultural connections.40 Failure to properly assess whether the population of focus understands the study goals can cause extreme harm to a community and raises issues regarding the respect of cultural views and scientific discovery.26

Multiple studies have found that this justified, deep-seated mistrust of research and experiences of discrimination that lower participation in research continues to be reinforced by current healthcare system encounters.27,36 Lower involvement in research by marginalized, racialized communities decreases the generalizability of findings and perpetuates pain disparities. As explained in the third paper of the series,56 the perception that racialized individuals are not willing to engage in research studies or that they are hard to recruit could be significantly challenged and successfully eliminated by employing culturally-responsive research practices, including partnering with stakeholders and community organizations to rebuild trust and communicate our shared goal around improving understanding of the pain experience and pain outcomes in racialized groups.

Critical Race Theory and Public Health

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a rich scholarly tradition and social philosophy focused on the impacts of racialization and structural racism in perpetuating a caste system that assigns non-Whites groups to the lowest tiers.39 CRT originated from legal scholars and puts forth the concept that racism is influenced and created more by societal structures and cultural assumptions than by individual “bad apples.” Key tenets of CRT include recognition that 1) “race” is socially constructed and significant, but not biologically real, 2) racism is a manifestation of embedded and intentional structural institutions and practices, as well as systemic racism, and 3) the systemic nature of racism is responsible for maintaining inequities. Further, it highlights the importance of building awareness of one’s levels of privilege and valuing the lived experiences of people within socially marginalized groups to create equity (ie, centering the margins).38 Importantly, CRT asserts that ignoring racialized identity does not represent “neutrality” but instead perpetuates the existing racial hierarchy (racism).

Ford and Airhihenbuwa (2010) called for public health scholars to adopt antiracism research practices grounded in CRT (a model called Public Health Critical Race praxis; PHCR) to promote health equity.38 They explained that consciousness about racialized identities – rather than colorblindness – in research is necessary for understanding how health constructs and mechanisms might apply to some groups but not others.38 Additionally, they emphasized that researchers should remain attentive to health equity at every stage of the research process. Finally, they encouraged researchers to center scientific practices around marginalized groups’ perspectives, rather than the usual practice of centering on privileged groups’ perspectives. Based on CRT and PHCR praxis, as well as recent scholarly work,39 the ACTION-PR drafted potential “guiding principles” to introduce an antiracism framework specific to pain research.

A Call to Action: Introducing an Antiracism Approach to Pain Research

In the summer and fall of 2020, scholars from many fields released position statements for taking an antiracism stance in their respective disciplines.16,24,30 The ACTION-PR wanted to approach the call for antiracism in the field of pain by first bringing together colleagues for discussion on these issues, rather than simply imposing our views to create change. First, the ACTION-PR was formed in September 2020 and worked together to develop guidelines for antiracism practices in pain research practice, based on CRT, PHCR, and recommendations from other fields.15,30 Next, we invited colleagues to come together and engage in group reflection on ways that racism might be operating in our field of pain science and discuss the ideas proposed in our original “guiding principles” in a think tank. Colleagues with their area of research or clinical expertise working with racialized communities and who might be interested in contributing to this think tank were contacted and told they could invite additional colleagues who might be interested. The majority of researchers contacted were previous members of the Pain and Disparities Special Interest Group of the now dissolved American Pain Society (APS).

The goal of these think tanks was to come together as a community of pain disparities researchers and policymakers to brainstorm ways of improving the quality of how we conduct our work.’ It was not to yield generalizable knowledge about pain researchers’ perspectives on antiracism. We informed our colleagues that the purpose of these discussions was to brainstorm ways to improve how we conduct our work and get feedback on our draft of “guiding principles” for antiracism in pain research (see Supplement A for discussion questions and proposed draft). We provided discussion questions to help facilitate conversations; however, our colleagues were told they could provide feedback or discuss topics related to racism and/or antiracism in pain research that they had beyond our discussion questions.

We used smaller think tanks of 5 to 7 individuals to facilitate brainstorming, with ACTION-PR members as facilitators. In total, 39 colleagues joined the virtual think tanks on either October 27, 2020, or November 6, 2020) that lasted 2 hours each. Researchers who wanted to share their feedback on the “guiding principles” document but could not attend either meeting were offered the option of meeting separately with the ACTION-PR or providing feedback in written form. All attendees were notified that they would be acknowledged, if they liked, for their role in shaping the ACTION-PR’s effort. The Acknowledgments section in each paper includes the colleagues who provided written approval to be named in the series. In December 2020, members of the ACTION-PR (AMH, CAM, JEL and LCC) presented a symposium on these efforts at the US Association for the Study of Pain (USASP) inaugural meeting. This event was recorded and can be viewed at the USASP website (https://www.usasp.org/december-9-11-2020-past).

Since these think tanks, the ACTION-PR has continued to discuss the development of our framework. The content of this series is based heavily on these subsequent discussions among ACTION-PR members, our literature reviews in preparing this series, and the important feedback from peer reviewers. Overall, this series draws on literature from public health, nursing, and statistics as well as literature outside of traditional biomedical fields, including medical anthropology, critical race studies, history, and sociology. The feedback from the think tanks, however, importantly helped our shared approach to disseminate a call for antiracism in pain research (as discussed below).

Shared Commitments to Antiracism in Pain Research

Through our think tanks, clear support for establishing an antiracism framework in pain research emerged; however, our colleagues had varying opinions on how this goal might be achieved. Based on the diversity of opinions shared in the think tanks, we have shifted from describing our call to action as “guiding principles” since it imposes one approach to study design, analyses, interpretations, and dissemination to a shared commitment for antiracism that holds the field (including ACTION-PR) accountable for individual and collective learning. As mentioned earlier, we do not propose having all the answers with this series and encourage research teams to consider our suggestions and apply them as most appropriate for their work. This series is a starting point and is offered as a “living document” that will continue to evolve as research on these approaches occurs and new recommendations emerge. In that vein, we strongly encourage continued conversations among researchers, clinicians, policy-makers, patients, and advocates to achieve justice for racialized groups in the field of pain.

As depicted in Figure 1, antiracism in pain research is grounded in cultural humility and often begins with antiracism education and self-reflect on biases and assumptions that influence the conceptualization of research questions to understand how various aspects of identity intersect and affect the pain experience (ie, “how systemic racism influences pain outcomes?”). Researchers can enhance this approach through partnerships and co-production with local community advisory boards and stakeholders to develop and review study questions, assist with the research design, and help with best recruitment practices and strategies. For example, a researcher using an antiracism framework might investigate the effects of racism and differences in the lived experiences rather than racialized group differences in pain. During data collection, the researcher may increase the diversity of the sample (ensuring that the sample reflects the population the research is intended for) to improve the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the researcher may ensure that the instruments used in data collection are culturally appropriate and have been validated in a diverse sample. During the analysis phase, the antiracism framework calls to move beyond group comparisons and instead explore within-group heterogeneity to elucidate mechanisms contributing to observed group differences. Finally, at the dissemination phase, researchers applying an antiracism framework would document areas of parity, refrain from blaming racialized groups for their experiences, and hold oppressive forces accountable (ie, systematic racism, power distribution). During this process, researchers should also consider how their research might impact a patient living with pain and how the narrative may affect racialized groups. The aforementioned practices are not universal for all study designs; yet, they illustrated the many opportunities in the process in which researchers could implement an antiracism research framework (see Letzen et al.,56 this issue, and Hood et al.,68 this issue, for a more comprehensive review of research designs, analysis and disseminations examples).

We advocate the need to re-convene a diverse group of pain research experts (spanning clinical and basic science) regularly, such as every 5 years or as feasible based on geographic location and research needs to review and update proposed practices and meet in no less than every 10 years to consider significant revisions. The regular evaluation will help determine the impact of antiracism on pain inequities and begin to inform future pain policies. Ultimately, collaborative efforts, ongoing reflection, and communication across all areas of pain research are vital to evaluate how implementing the antiracism framework in pain research promotes pain equity and good scientific practice. Focused research findings and shared testimonies are a critical channel by which the current approaches to antiracism research will gain support from the pain science community for future implementation. Moving forward, it will be essential to identify core components and specific recommendations that could be used to inform national policies to promote equitable pain care.

Antiracism pain praxis holds researchers, educators, and clinicians accountable for active antiracism training throughout their careers to combat potential biases, misbeliefs, and comfort in privileged positions that perpetuate pain inequities. Antiracism is the critical stance because it is not enough to take a more passive “non-racist” approach; antiracism is a prerequisite for pain research that will effectively apply across humans. As eloquently detailed by Ghoshal et al, it is essential that a willful, organized, and multi-faceted approach that combines policy, opportunities for racialized scholars in and health equity roles, and individualized approach to pain assessment and treatment41 Further, a “paradigmatic revision in the models under which pain care professionals are trained,” including mandatory annual training and initiatives at every level to increase the number of minoritized students in medical school and other health professions,52,77 will be critical to move towards delivery of equitable pain care. As would be expected, the optimal type of training will vary based on the target for intervention (ie, individual-level, organizational-level)11; yet, it is important to acknowledge that at the core of many of these interventions lies bringing awareness to biases, which is the starting place for changing attitudes and behaviors that perpetuate ideologies and practices.21,44,47 As discussed in more detail in Part 2, subjectivity and advocacy in science have long been sources of biases, yet they are inherent in science in many ways. For instance, subjectivity is embedded in the choice of who is included and valued on the research team, study design, and dissemination of findings, and research funding priorities and the training of future researchers in our field are shaped by advocacy related to how best meet the needs of individuals with pain. Thus, acknowledging subjectivity – rather than denying its existence – can help us be aware of our choices and provide needed context to the pain science arena.

A foundational shift in the pain field is our call for individual investigators to develop cultural humility. As described in more detail below, cultural humility is a fundamental process of self-reflection and humbleness that allows us to interrogate and mitigate racism while applying antiracism practices successfully.

Cultural Humility: A Foundation for Antiracism Pain Research

Understanding how various aspects of racialized individuals’ lived experiences intersect and influence pain is vital for moving the field of pain research away from conceptualizations that perpetuate structural, institutional, interpersonal, and intrapersonal racism in understanding and treating pain. However, appreciating the context of others’ lives carries with it the expectation that one is aware and reflective of one’s background and the inherent limitations one’s individual experiences imposes on the capacity for understanding the lived experiences of others. The stance that building cultural knowledge about others requires self-knowledge and self-reflection is foundational to the concept of cultural humility.

Cultural humility was first articulated in the clinical care context as “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture but starts with an examination of their own beliefs and cultural identities.98,106“ Building on the foundation of self-knowledge, cultural humility also involves acknowledging one’s own biases and forms of privilege, as well as acting to redress the power imbalances that disadvantage racialized and minoritized individuals and populations.57,106

Until recently, a term that has been used more widely than cultural humility and has received significant uptake in organizational and clinical settings (eg, universities, hospitals, etc.) is cultural competence. In comparing cultural humility to cultural competence, Yeager and Bauer-Wu assert that cultural competence is measured against knowledge about the ‘other’ with less emphasis on self-awareness since the goal is to learn about the other person’s culture rather than reflect on one’s background.98 However, without the critical self-reflection that is part of cultural humility, it can be difficult to bring into conscious awareness one’s motivations for maintaining a status quo that confers privilege rather than working for change.

To start, privilege refers to an ”unearned power that is only easily or readily available to some people simply as a result of their social (or racialized) group membership.98” Privilege provides advantages that are often invisible to those who are privileged but describing the components of privilege can bring these advantages into conscious awareness for those who are engaged in reflective practice. At its core, privilege encompasses dominance, identification, and centeredness conferred by society to some, resulting in a self-sustaining hierarchy to the advantage of the few and disadvantage of the many.106 Dominance positions those with privilege as leaders by default. Identification positions those with privilege as the norm against which others are compared. Finally, centeredness positions those with privilege at the center of positive attention (eg, hero role), leaving the non-privileged to be largely marginalized and only centered or visible in the context of negative attention (eg, crime, poverty).35 Cultural humility can help change how one wields privilege by building the capacity to operate against self-interest and become other-oriented regarding addressing power imbalances.35

Consistent with the stance of Yeager and Bauer-Wu (2013), this paper also asserts that cultural humility is critical not just for the clinical context in which the concept was first applied but also for pain research.35 Cultural humility is imperative for closing the research gap between the predominantly White pain research community and racialized groups who are underrepresented as researchers and research participants.14 Without it, we are left ill-equipped to understand and learn from those who are different from ourselves, across all the cultural identities borne out of or shaped by the social constructs of “race” and ethnicity, the very identities positioned in hierarchies that determine how pain is experienced, and the extent to which it will be appropriately assessed and treated.57,59,106 In the pain field, increasing training in cultural humility will facilitate a greater understanding of the pain experience across racialized groups and create an environment conducive for antiracism in research practices. One way to practice cultural humility is to practice self-reflection by exploring our biases, recognizing personal privilege and engaging in ongoing self-evaluation.14,20,61

Positionality Statement

For many years, qualitative researchers have used positionality statements to inform readers of the authors’ social positions, lived experiences, and training backgrounds as these identities affect the conceptualization, design, assessment, and interpretation of research findings.28,55 More recently, some quantitative journals have adopted a similar stance.91 In keeping with this stance and its foundation in cultural humility, we include a positionality statement below to describe the personal and professional lenses through which the authors view the field of pain research. It is from this collection of perspectives that this series was written. Importantly, the following is just 1 way a positionality statement can be shared. The information provided includes identities that each author put forward as salient in their approach to this series.

The ACTION-PR is a diverse group of investigators that shares the values of social justice and equity in pain care as well as research that focuses on pain disparities. Each author would like to acknowledge the following aspects of their identity that they think informed their work on this series. C.A.M. is a first-generation immigrant from Peru, a first-generation college graduate trained in clinical psychology, is a pain inequities researcher, and is perceived as Hispanic in the US. E.N.A. is an immigrant African American male and PhD prepared Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist perceived as Black in the US. S. Q. B. is an African American woman, millennial, born and raised in the deep South in a predominantly Black community, third-generation college graduate, nurse scientist, and Christian. C.M.C. is a White, first-generation college graduate, pain researcher and clinical psychologist. L.C.C. is a Black woman born and raised in the American South, trained in clinical health psychology. B. R. G. is a White man born and raised in the rural Midwest US., a first-generation college graduate, and a clinical health psychologist by training. A.M.H. is a dual British and American citizen Black woman trained in clinical psychology whose grandparents emigrated from Jamaica to the UK as part of the Windrush generation. M.R.J. is trained in health behavior, community health sciences, and social epidemiology. She is a White cisgender woman raised in a working-class family in the midwestern U.S. and is the granddaughter of immigrants from Montenegro in southeastern Europe. J.E.L. completed her training in clinical psychology, is the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Argentina, identifies as Argentine American, and is perceived as white in the US. V.A.M. is a diversity scientist with interdisciplinary training and a research focus on pain disparities. The child of an immigrant from India raised in a multicultural and mixed-racial family in Texas, she identifies as multiracial but is perceived as white in the US. E.N.M. is US born and self-identifies as a cisgender Black woman. She has interdisciplinary training as a clinical and translational scientist, is a licensed physical therapist, and has a research focus on obesity-related pain inequities.

The ACTION-PR would like to note 2 areas that particularly influence the conceptualization and interpretation of this Confronting Racism series. First, we have all completed our research training and currently conduct research in WEIRD countries, which means we do not have authors with a first-hand experience perspective of currently living and working in the Global South. Second, the ACTION-PR includes 1 translational researcher, 10 clinical researchers, and 1 collaborator in Part 2 who is an expert in pre-clinical pain models. Therefore, the critical perspectives from a diverse group of pre-clinical and translational pain researchers are not included. Finally, the ACTION-PR members have research efforts dedicated to understanding the mechanisms and solutions for racialized pain inequities with varied years of experience, methodologies, and levels of expertise that complement each other’s knowledge. We have various degrees of expertise in antiracism, but our collective scholarship is newer to this area relative to our other areas of research. As such, the ACTION-PR is actively seeking to continue 1) learning from scholars from various disciplines dedicating their careers to critical race theory and antiracism, 2) developing our cultural humility, 3) reflecting on our research practices, and 4) using these combined practices to advocate for research methods that will advance pain equity.

Closing Statement

In this paper, we assert that addressing racism within pain research requires an antiracism framework to dismantle racist practices and policies to pursue greater racial equality and social justice for racialized groups. Although the effects of racism on pain have started to be examined in the context of pain science,29 there remains a critical gap in knowledge and skills to stop the perpetuation of racism and develop multi-system change. In general, applying an antiracism approach to pain research encourages us to open new avenues of inquiry by considering issues of power, privilege, racism, and other forms of oppression to help solve long-standing social problems that exacerbate the pain experience and inadequate pain. The think tank organized by the ACTION-PR and ongoing communication among our coauthors has led to the call for a shared commitment for antiracism in pain research, including the urgent need to promote antiracism in pain education. We were also encouraged by the overwhelming support to continue collaborative efforts to assess the ongoing impact of the current recommendations and inform future changes. In the 2 subsequent papers of this series, we discuss strategies that will help create a shift toward antiracism in pain research strategies. We invite the reader to reflect on their work and adopt these suggestions to counter and remove any unintentional bias in their research. In doing so, we hope that our multidisciplinary, multidimensional field of pain science will demonstrate accountability leading to substantial changes in our current research practices.

Supplementary Material

Perspective:

We call on the pain community to dismantle racism in our research practices. As the first paper of the 3-part series, we introduce dimensions of racism and its effect on pain inequities. We also describe the imperative role of cultural humility in adopting antiracism pain research practices.

Acknowledgments

In the Fall of 2020, several of our pain disparities colleagues joined us for a virtual think tank about antiracism in pain research. We appreciate their time and valuable insights that shaped the approach to this series. The following individuals have provided written approval to acknowledge their individual role in the think tank: Emily Bartley, PhD; Amber Brooks, MD; Yenisel Cruz-Almeida, PhD; Troy Dildine; Roger Fillingim, PhD; Elizabeth Losin, PhD; Megan Miller, PhD; Chung Jung Mun, PhD; Andrea Newman, PhD; Michael “Alec” Owens, PhD; Fenan Rassu, PhD; Jamie Rhudy, PhD; Keesha Roach, PhD; Sheria Robinson-Lane, PhD, RN; Ellen Terry, PhD; Benjamin Van Dyke, PhD. Additionally, we would like to thank the 4 researchers and 8 National Institutes of Health affiliates who will remain anonymous.

Funding sources include the following: 5P30AG059297-04S1 (NIH/NIA, Morais); UAB Obesity Health Disparities Research Center (OHDRC) Award & R01AR079178 (NIH/NIAMS, Aroke); K23NS124935 (NIH/NINDS, Letzen); R01MD009063 (NIH/NIMHD, CM Campbell); 5K01AG050706 (NIH/NIA, Janevic); R01MD010441 (NIH/NIMHD) & R01HL147603 (NIH/ NHLBI, Goodin); K23AR076463 (NIH/NIAMS, Booker)

Footnotes

Special note: The Journal of Pain presents the following trilogy of Focus Articles, in which the authors argue that a disregard for how racism manifests in pain research perpetuates pain inequities and also slows the progression of the field. The authors discuss how an antiracism pain research framework can be incorporated across the continuum of pain research. This series advocates for a shared commitment toward an antiracism framework in pain research.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2022.01.009.

References

- 1.Adames HY, Chavez-Dueñas NY, Organista KC: Skin color matters in Latino/a communities: Identifying, understanding, and addressing Mestizaje racial ideologies in clinical practice. Prof Psychol: Res and Practice 47:46–55, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10:1187–1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anyane-Yeboa A, Sato T, Sakuraba A: Racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths reveal harsh truths about structural inequality in America. J Intern Med 288:479–480, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aroke EN, Joseph PV, Roy A, Overstreet DS, Tollefsbol TO, Vance DE, Goodin BR: Could epigenetics help explain racial disparities in chronic pain? J Pain Res 12:701–710, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avenanti A, Sirigu A, Aglioti SM: Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Curr Biol 20:1018–1022, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT: How structural racism works - racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med 384:768–773, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT: Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 389:1453–1463, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barot R, Bird J: Racialization: the genealogy and critique of a concept. Ethnic and racial Studies 24:601–618, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates MS, Edwards WT: Ethnic variations in the chronic pain experience. Ethn Dis 2:63–83, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman G, Paradies Y: Racism, disadvantage and multi-culturalism: Towards effective anti-racist praxis. Ethn Racial Stud 33:214–232, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berzukova K, Spell CS, Perry JL, Jehn KA: A meta-analytical integration of over 40 years of research on diversity in training education. Psychol Bull 142:1227–1274, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettache K: A call to action: The need for a cultural psychological approach to discrimination on the basis of skin color in Asia. Perspect Psychol Sci 15:1131–1139, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beydoun KA: Boxed in: Reclassification of Arab Americans on the US census as progress or peril. Loy U Chi LJ 47:693, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booker SQ, Bartley EJ, Powell-Roach K, Palit S, Morais C, Thompson OJ, Cruz-Almeida Y, Fillingim RB: The imperative for racial equality in pain science: A way forward. J Pain, 2021. Jun 30. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR: On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog 10:1377, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breny JM: Continuing the journey toward health equity: Becoming antiracist in health promotion research and practice. Health Educ Behav 47:665–670, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brondolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF: Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J Behav Med 32:1–8, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulgin D, Tanabe P, Jenerette C: Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 39:675–686, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB: Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain 113:20–26, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell LC, Robinson K, Meghani SH, Vallerand A, Schatman M, Sonty N: Challenges and opportunities in pain management disparities research: Implications for clinical practice, advocacy, and policy. J Pain 13:611–619, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter ER, Onyeador IN, Lewis NA: Developing & delivering effective anti-bias training: Challenges & recommendations. Behav Sci Policy 6:57–70, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaet DH: AMA code of medical ethics’ opinions related to discrimination and disparities in health care. AMA J Ethics 18:1095–1097, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavez-Dueñas NY, Adames HY, Organista KC: Skin-color prejudice and within-group racial discrimination. Hisp J Behav Sci 36:3–26, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, Sanchez E, Sharrief AZ, Sims M, Williams O: Call to action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 142:e454–e468, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR: Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol 54:805–816, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claw KG, Anderson MZ, Begay RL, Tsosie KS, Fox K, Garrison NA: A framework for enhancing ethical genomic research with Indigenous communities. Nat Commun 9:2957, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S: Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med 14:537–546, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corlett S, Mavin S: Reflexivity and Researcher Positionality. The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods, 2018, pp 377–398 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig KD, Holmes C, Hudspith M, Moor G, Moosa-Mitha M, Varcoe C, Wallace B: Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. Pain 161:261–265, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crear-Perry J, Maybank A, Keeys M, Mitchell N, Godbolt D: Moving towards anti-racist praxis in medicine. Lancet 396:451–453, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David EJR, Schroeder TM, Fernandez J: Internalized racism: A systematic review of the psychological literature on racism’s most insidious consequence. J Soc Issues 75:1057–1086, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiAngelo RJ: White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, 1st ed. Beacon Press, 2018, pp 186. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominick KL, Baker TA: Racial and ethnic differences in osteoarthritis: Prevalence, outcomes, and medical care. Ethn Dis 14:558–566, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupont C, Armant DR, Brenner CA: Epigenetics: Definition, mechanisms and clinical perspective. Semin Reprod Med 27:351–357, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan D, Johnson AG: Privilege, power, and difference. Teach Sociol 30:266, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer DF, Jackson SA, Camacho F, Hall MA: Attitudes of African American and low socioeconomic status white women toward medical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 18:85–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farooq F, Mogayzel PJ, Lanzkron S, Haywood C, Strouse JJ: Comparison of Us federal and foundation funding of research for sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis and factors associated with research productivity. JAMA Netw Open 3: e201737, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO: Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health 100(Suppl 1):S30–S35, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO: The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med 71:1390–1398, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrison NA: Genomic justice for Native Americans: Impact of the Havasupai case on genetic research. Sci Technol Human Values 38:201–223, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghoshal M, Shapiro H, Todd K, Schatman ME: Chronic noncancer pain management and systemic racism: Time to move toward equal care standards. J Pain Res 13:2825–2836, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez-Sobrino B, Goss DR: Exploring the mechanisms of racialization beyond the black–white binary. Ethn Racial Stud 42:1–6, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gooding-Williams R: WEB Du Bois, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gopal DP, Chetty U, O’Donnell P, Gajria C, Blackadder-Weinstein J: Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc J 8:40–48, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kalauokalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH: The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277–294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hage G: Recalling anti-racism. Ethn Racial Stud 39:123–133, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagiwara N, Kron FW, Scerbo MW, Watson GS: A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks. Lancet 395:1457–1460, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haley JM: Intersectional and relational frameworks: Confronting anti-blackness, settler colonialism, and neoliberalism in US social work. J Progressive Human Serv 31:210–225, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hattery AJ, Smith E: Policing Black Bodies: How Black Lives Are Surveilled and How to Work for Change, 319. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haywood C, Lanzkron S, Bediako S, Strouse JJ, Haythornthwaite J, Carroll CP, Diener-West M, Onojobi G, Beach MC: Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med 29:1657–1662, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haywood C, Tanabe P, Naik R, Beach MC, Lanzkron S: The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 31:651–656, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrenkohl TI, Wooten NR, Fedina L, Bellamy JL, Bunger AC, Chen D-G, Jenson JM, Lee BR, Lee JO, Marsh JC: Advancing our commitment to antiracist scholarship. J Society Soc Work Res 11:365–368, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirsh AT, Hollingshead NA, Ashburn-Nardo L, Kroenke K: The interaction of patient race, provider bias, and clinical ambiguity on pain management decisions. J Pain 16:558–568, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN: Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:4296–4301, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holmes AG: Researcher positionality–a consideration of Its influence and place in qualitative research–a new researcher guide. Shanlax Int J Educ 8:1–10, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hood AM, Booker SQ, Morais CA, Goodin BR, Letzen JE, Campbell LC, Merriwether EN, Aroke EN, Campbell CM, Mathur VA, Janevic MR: Confronting racism in all forms of pain research: A shared commitment for engagement, diversity, and dissemination. J Pain 23:913–928, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington EL, Utsey SO: Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J Couns Psychol 60:353–366, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hudson KL, Collins FS: Family matters. Nature 500:141–142, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughes V, Delva S, Nkimbeng M, Spaulding E, Turkson-Ocran R-A, Cudjoe J, Ford A, Rushton C, D’Aoust R, Han HR: Not missing the opportunity: Strategies to promote cultural humility among future nursing faculty. J Prof Nurs 36:28–33, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.James D: Health and health-related correlates of internalized racism among racial/eEthnic minorities: A review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 7:785–806, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janevic MR, Mathur VA, Booker SQ, Morais C, Meints SM, Yeager KA, Meghani SH: Making pain research more inclusive: Why and How. J Pain 23:707–728, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jenerette CM, Brewer CA, Ataga KI: Care seeking for pain in young adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Manag Nurs 15:324–330, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jordan JM: Effect of race and ethnicity on outcomes in arthritis and rheumatic conditions. Curr Opin Rheumatol 11:98–103, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, Green BL, Wang MQ, James SA, Russell SL, Claudio C: The tuskegee legacy project: Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 17:698–715, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khazanchi R, Evans CT, Marcelin JR: Racism, not race, drives inequity across the COVID-19 continuum. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2019933, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, Goyal M, Chen C, Ma Y, Meltzer AC: Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 37:1770–1777, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leong FTL, Pickren WE, Vasquez MJT: APA efforts in promoting human rights and social justice. Am Psychol 72:778–790, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Letzen JE, Mathur VA, Janevic MR, Burton MD, Hood AM, Morais CA, Booker SQ, Campbell CM, Aroke EN, Goodin BR, Campbell LC, Merriwether EN: Confronting racism in all forms of pain research: Reframing designs. J Pain 23:893–912, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Long JC, Kittles RA: Human genetic diversity and the nonexistence of biological races. Hum Biol 75:449–471, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Losin EAR, Woo C-W, Medina NA, Andrews-Hanna JR, Eisenbarth H, Wager TD: Neural and sociocultural mediators of ethnic differences in pain. Nat Hum Behav 4:517–530, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Masters JR: HeLa cells 50 years on: The good, the bad and the ugly. Nat Rev Cancer 2:315–319, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mathieson I, Scally A: What is ancestry? PLoS Genet 16:e1008624, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mathur VA, Kiley KB, Haywood C, Bediako SM, Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Buenaver LF, Pejsa M, Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Campbell CM: Multiple levels of suffering: Discrimination in health-care settings is associated with enhanced laboratory pain sensitivity in sickle cell disease. Clin J Pain 32:1076–1085, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathur VA, Morris T, McNamara K: Cultural conceptions of Women’s labor pain and labor pain management: A mixed-method analysis. Soc Sci Med 261:113240, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mathur VA, Richeson JA, Paice JA, Muzyka M, Chiao JY: Racial bias in pain perception and response: Experimental examination of automatic and deliberate processes. J Pain 15:476–484, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mathur VA, Trost Z, Ezenwa MO, Sturgeon JA, Hood AM: Mechanisms of injustice: What we (don’t) know about racialized disparities in pain. Pain. 2021. Nov 1. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matsui EC, Perry TT, Adamson AS: An antiracist framework for racial and ethnic health disparities research. Pediatrics 146, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM: Time to take stock: A meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med 13:150–174, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meints SM, Cortes A, Morais CA, Edwards RR: Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Manag 9:317–334, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mende-Siedlecki P, Qu-Lee J, Backer R, Van Bavel JJ:Perceptual contributions to racial bias in pain recognition. J Exp Psychol Gen 148:863–889, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]