Abstract

Objective

This study was aimed to assess patient and provider perceptions of a postpartum patient navigation program.

Study Design

This was a mixed-method assessment of a postpartum patient navigation program. Navigating New Motherhood (NNM) participants completed a follow-up survey including the Patient Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationship with Navigator (PSN-I) scale and an open-ended question. PSN-I scores were analyzed descriptively. Eighteen provider stakeholders underwent in-depth interviews to gauge program satisfaction, perceived outcomes, and ideas for improvement. Qualitative data were analyzed by the constant comparative method.

Results

In this population of low-income, minority women, participants (n = 166) were highly satisfied with NNM. The median PSN-I score was 45 out of 45 (interquartile range [IQR]: 43–45), where a higher score corresponds to higher satisfaction. Patient feedback was also highly positive, though a small number desired more navigator support. Provider stakeholders offered consistently positive program feedback, expressing satisfaction with NNM execution and outcomes. Provider stakeholders noted that navigators avoided inhibiting clinic workflow and eased clinic administrative burden. They perceived NNM improved multiple clinical and satisfaction outcomes. All provider stakeholders believed that NNM should be sustained long-term; suggestions for improvement were offered.

Conclusion

A postpartum patient navigation program can perceivably improve patient satisfaction, clinical care, and clinic workflow without burden to clinic providers.

Keywords: navigator, patient navigation, postpartum, program evaluation, stakeholder feedback

Women’s engagement in postpartum care is critical in promoting short- and long-term maternal health.1 Yet, reports suggest postpartum appointment attendance is inadequate.1,2 Furthermore, significant disparities in utilization of postpartum appointments exist based on maternal race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance type, education, and age, with women from low-resourced communities being less likely to access postpartum care.3–8

Patient navigation has been suggested as one mechanism to ameliorate such utilization disparities by reducing barriers to seek and access health care.9–15 Patient navigation interventions employ trained personnel to identify patient-level barriers and facilitate complete and timely access to health services. Navigation has been used across a variety of women’s health contexts, including cancer screening and care, with success in increasing patient satisfaction, retaining more patients in care, improving continuity, and promoting more timely follow-ups on screening or diagnostic results.16–21 Furthermore, evaluations of provider stakeholders involved with patient navigation programs demonstrate that they view navigation as a positive, well-integrated intervention model with the ability to enhance clinical services and reduce provider workload.22,23

Given the success of patient navigation programs with women’s health issues in other communities, a patient navigation program, “Navigating New Motherhood” (NNM), was implemented in a large tertiary care center’s hospital-based women’s health clinic for a 1-year period. This program was designed to improve attendance at the postpartum appointment and to provide psychosocial and logistical postpartum support in a community of low-income, largely minority women. Compared with women who received care at the same clinic prior to implementation of NNM, women who attended the clinic during the NNM period showed improvement in several clinical outcomes, including postpartum visit attendance.24 However, the original study did not explore patients’ and provider stakeholders’ perceptions of the program. Such feedback on areas of program strengths and weaknesses is crucial to understand the long-term sustainability of such a program and to optimizing the effectiveness and reach of similar, future programs. Furthermore, previous work has indicated a shortage of studies analyzing patient satisfaction with navigation.11

In this study, we performed comprehensive patient and provider stakeholder assessments to evaluate understanding of program details, satisfaction with program execution and outcomes, and perceived areas for improvement. Such assessments may allow future navigation programs to capitalize on existing successes and maximize patient outcome improvement, provider stakeholder collaboration, and patient and provider stakeholder satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, mixed-method analysis of feedback from patient and provider stakeholders who either participated in the NNM program or who provided care at Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s Prentice Ambulatory Care Clinic throughout the program’s duration. Stakeholders were defined as individuals with a vested clinical, financial, educational, and/or personal interest in patients’ return for postpartum care. Stakeholders thus included patients and clinic providers (nurses, clinic support staff, administrators, and physicians).

In brief, NNM consisted of a patient-centered navigation approach to enhance quality and quantity of postpartum care in an obstetric clinic serving largely minority (>80% non-White), low-income women from June 2015 to May 2016. The program was patient-centered in that the psychosocial and logistical support offered by the navigator were driven by patient needs and preferences; patient input directly informed the development and execution of the navigation program. The NNM navigation team consisted of a full-time navigator and a part-time navigator. The navigators had previous experience navigating low-income women through women’s health cancer screenings and treatment; they received training specific to postpartum care. Both navigators had the key skill sets of excellent communication, comfort speaking with the health care team and acting as a bridge between patients and health care team members, and comfort working with patients from diverse backgrounds. The navigators introduced themselves to eligible patients (English-speaking, ≥18 years, and Medicaid-funded prenatal care) either during late third-trimester prenatal appointments or the inpatient hospitalization to describe NNM and enroll interested patients. NNM was designed to function independently of physicians’ direct involvement, since the patients in this practice were cared for by rotating physician teams.

The navigators coordinated postpartum appointment scheduling for participants through direct communication with clinic administrative staff. In addition to appointment scheduling, the navigator role involved: providing emotional, informational, and logistical support to patients; facilitating contraception uptake by answering contraception-related questions and communicating patient needs to clinic staff; coordinating care within the study clinic by advocating to providers regarding individual patients; connecting participants to outside clinicians as needed for maternal or neonatal concerns; and reminding patients of appointments. Further details about the findings and procedures of NNM have been described previously.24

During postpartum appointments with patient stakeholders (or later via phone if necessary), navigators conducted patient follow-up surveys. Each question was read aloud to the participant to account for literacy disparities. Surveys consisted of both quantitative and qualitative sections. In the quantitative section, patient satisfaction with the navigation program was assessed using the Patient Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationship with Navigator (PSN-I) survey,25 a metric shown to be highly correlated with patient satisfaction with overall care.26 This survey consisted of nine questions regarding a patient’s satisfaction with her interpersonal relationship with her navigator; items are scored from 1 to 5 (5 indicates high satisfaction). In addition, patients were asked to rate how easy it was to make a postpartum appointment on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 indicates high ease). Participants were given the option to provide additional comments regarding their interpersonal relationship with the patient navigator; both positive and negative feedback was encouraged. Overall PSN-I survey scores from completed surveys were analyzed through a histogram of observed survey scores and descriptive statistics. Medians and interquartile range (IQR) are reported due to the left-skew in PSN-I scores. Open-ended feedback was analyzed using the qualitative methods described below.

To evaluate provider experiences, we performed in-depth qualitative interviews of provider stakeholders following NNM completion. Provider stakeholders’ perceptions were assessed using semistructured interviews, each approximately 25 to 30 minutes, designed to gauge understanding of program procedures and implementation, program satisfaction, perceived outcomes, ideas for improvement, and possible patient population expansions. The interview guide was adapted from a similar assessment of a DuPage County cancer-patient navigation program22 and included many of the same major categories. The modified interview guide also included follow-up prompts for each question to reduce variation between interviews. The only DuPage County interview guide categories excluded from the NNM guide were those specifically referring to the DuPage County program design or to cancer care. Interview topics from the adapted NNM interview guide used in this study are shown in ►Table 1.

Table 1.

Provider stakeholder interview structure

| Question categories | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| General navigation context | • Understanding of navigation |

| • Perceived beneficial services of navigation | |

| • Perceived challenges patients experience with postpartum care | |

|

| |

| Program procedures and implementation | • Day-to-day NNM implementation into clinic |

| • Patient-navigator interactions | |

| • Provider-navigator interactions | |

|

| |

| Provider stakeholder satisfaction | • NNM and patient navigation as a concept |

| • Successes of NNM implementation | |

| • Perceived patient outcomes due to NNM | |

| • Mutual benefits of navigation | |

|

| |

| Areas of improvement | • Limitations of NNM |

| • Suggestions for improving navigation efficacy and support | |

|

| |

| Patient population expansions/focuses | • Patients who especially needed or could most benefit from navigation |

| • Patients who were particularly receptive to navigation | |

| • Preferences and suggestions for program sustainability | |

Abbreviation: NNM, navigating new motherhood.

We approached all permanent staff members who had cared for NNM patients, as well as a convenience sample of trainee physicians (residents and fellows), who provided clinical care at the study site during NNM. All provider stakeholders were informed that their interviews would be digitally recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription company unaware of interviewer identity; interviewees were informed that their responses would be anonymous on transcripts other than their professional role. Fifteen provider stakeholders were interviewed in person and three by phone, as they were no longer on-site. In-person interviews were conducted in private exam rooms at the study clinic. Each provider stakeholder received a gift card following the interview. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. All patient participants provided written informed consent for their participation in NNM, and all provider participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the evaluation phase.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996-certified professional transcription service. Dedoose (www.dedoose.com), a secure data management and qualitative data analysis software, was used to facilitate thematic analysis of the transcripts by the first and second authors using the constant comparative method.27 Analysts broke transcripts into identical excerpts and applied codes based on the same criteria for consideration. An initial codebook was established through exploratory analysis of the transcripts and was used by both analysts. Standardized operational code definitions were created via research team discussions. Any codes which emerged inductively during the subsequent coding process were added to the shared codebook. All codes were reassessed for effectiveness of capturing themes after an initial coding; ineffective themes were removed or reclassified. Discrepancies between analysts in code application were reviewed by the analysts. If a discrepancy was resolved through discussion, it was changed to reflect the agreement. If not, a disagreement was noted and both analysts’ codes were applied to the excerpt for the sake of analysis. Following this review process, Cohen’s Kappa was used to assess interrater agreement and was found to be 0.91 between the two analysts for 999 total coded excerpts.

Results

Patient Stakeholders

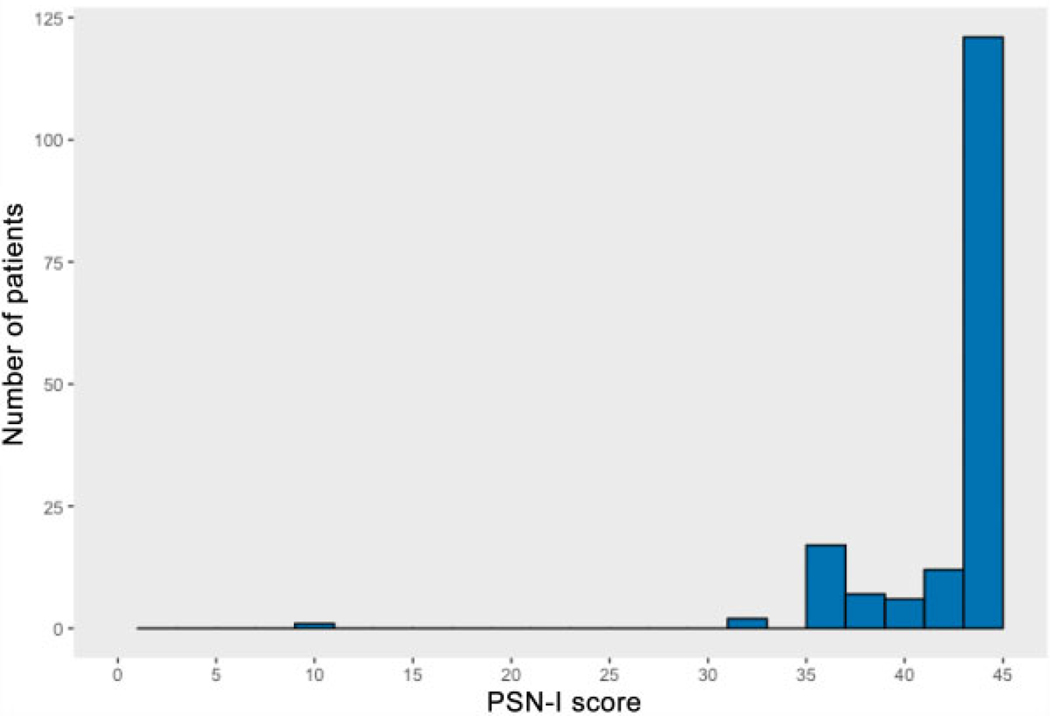

In total, 218 women enrolled in NNM, and 192 returned for a postpartum appointment. Women in NNM were largely non-Hispanic black (49.5%) or Hispanic (32.6%) and multiparous (70.2%); the majority delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery (65.1%). All had prenatal care funded by public insurance (►Table 2). Follow-up surveys were administered to 94.3% (n = 181) of the 192 NNM participants who returned. Of these 181 surveys, 99.4% (n = 180) of participants answered the question about ease of appointment scheduling, and 91.7% (n = 166) fully completed the PSN-I survey. Almost all (n = 178, 98.9, 95% confidence intervals calculated via the Wilson method 95.2 to 99.4%) reported that they “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement “My postpartum appointment was easily made.” The PSN-I survey has a maximum score of 45, corresponding with high satisfaction; participant PSN-I survey scores had a median of 45, with a first quartile of 43 and third quartile of 45 (►Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 28.9 (5.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 28 (12.8) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 108 (49.5) |

| Hispanic | 71 (32.6) |

| Asian | 10 (4.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.5) |

| Publicly funded insurance | 218 (100.0) |

| Married | 67 (31.0) |

| Primiparous | 65 (29.8) |

| Total number of prenatal visits (excluding transfers of care) | 9.4 (3.1) |

| Maternal-fetal medicine patient | 81 (37.3) |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 38.3 (3.1) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 142 (65.1) |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 7 (3.2) |

| Cesarean delivery | 69 (31.7) |

| Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia | 24 (11.0) |

| Excess hospital length of stay (>2 for vaginal delivery, >4 for cesarean delivery) | 16(7.3) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 47 (21.7) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 1.

Histogram of Patient Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationship with Navigator (PSN-I) survey scores from patients who returned to care and fully completed patient satisfaction surveys (n = 166).

Thirty-eight surveyed participants provided qualitative program feedback, with six themes identified (►Table 3). Generally, comments discussed patients’ overall experiences with their navigator and/or the navigators’ role as a support structure. Positive themes included positive navigation experiences (n = 37), logistical support from the navigator (n = 11), emotional support from the navigator (n = 7), and appreciation of text message-based communication (n = 2). Other themes included negative navigation experiences (n = 1) and desire for more navigator support (n = 3).

Table 3.

Patient stakeholder qualitative feedback on the patient navigation program

| Themes | n | Example excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Navigation experience was positive | 37 | “Overall great experience. (My navigator) was extremely helpful and knowledgeable regarding my healthcare needs and concerns.” |

| Navigator was logistically supportive | 11 | “I think I still have mommy brain so it was helpful to have reminders.” “You were very helpful and I would not have made it to my appointment had you not reminded me.” |

| Navigator was emotionally supportive | 7 | “She is awesome. Always there when I need someone to talk to.” “You helped me to get where I am because I was so lost.” |

| Navigator could have provided more support | 3 | “Even more contact, phone calls, emails, check-ups, etc.” |

| Text message communication was beneficial | 2 | “I liked the fact we received texts versus calls. It was much easier to answer” |

| Navigation experience was negative | 1 | “I was uncomfortable and didn’t feel like I could answer the questions because I only saw (the navigator) for 30 minutes.” |

Provider Stakeholders

Eighteen provider stakeholders involved with the care of NNM participants were approached approximately 2 months after the program’s completion; all agreed to participate in this study (►Table 4). Interviewees were first queried regarding the implementation of NNM to determine their familiarity with the program’s goals and procedures. Regarding specific navigator responsibilities, provider stakeholders relayed that they had observed navigators executing the logistical support, social support, and health education duties, described in ►Table 5, suggesting they had a good understanding of NNM program design and navigator actions. For example, when asked about program logistics, provider stakeholders appropriately identified that the navigators introduced themselves to patients during late third-trimester prenatal appointments, recruited patients for navigation after delivery, and helped schedule postpartum appointments while women were inpatient. Interviewees noted that the navigators discussed postpartum issues over text or by phone, communicated issues raised by the patient to clinic providers (in person or via secure email), and met with patients during the postpartum appointment to provide continued support (►Table 5).

Table 4.

Provider stakeholders (n = 18)

| Job Category | Provider stakeholders | n interviewed/n eligible |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Clinic coordinator/nursea | 1/1 |

| Full-time staff nursesa | 2/2 | |

| Patient care techniciansa | 2/2 | |

| Clinic Support | Social workera | 1/1 |

| Breastfeeding peer counselora | 1/1 | |

| Administrative | Clerical staff a | 2/2 |

| Navigators | 2/2 | |

| Physician | Chief obstetrics/ gynecology residents | 1/12b |

| Obstetrics/ gynecology residents | 4/36b | |

| Maternal-fetal medicine fellows | 2/3b |

Full-time clinic staff.

A convenience sample of physicians who had frequent interactions with navigating new motherhood was approached for interviews. Although only a small proportion of total house staff was interviewed, 100% of those approached agreed to be interviewed.

Table 5.

Provider stakeholder perception of navigator-executed responsibilities

| Common Themes | n | Example excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Logistical support | ||

| Scheduling postpartum appointments | 17 | “I think that having someone who could contact patients right after their delivery before they leave the hospital and have them leave with an appointment in hand was very helpful. … getting people established in care before they leave the hospital is important”—Fellow |

| Facilitating contraception uptake | 16 | “The navigators would send me and one of the clerical staff an email: ‘Mrs. Smith would like a Mirena. Mrs. Jones would like Nexplanon.’ So, it was kind of nice to have that, and we could prep for it and put it right in their notes so the doctor who was seeing them at that appointment, he would say ‘Can you get me a Mirena.’”— Clinical coordinator/nurse |

| Facilitating postpartum follow-up/appointments | 16 | “My understanding of patient navigation is that there is somebody who basically helps the moms coordinate. They call them; they make sure that they have appropriate follow-up, and when the patient is in the clinic when they come back at postpartum appointment, the navigator makes sure that they’re getting what they need.”—Resident |

| Meeting with patients postdelivery | 12 | “First, I would look at the list and see who delivered and see if they were eligible … Then I would give them a phone call to say (…) ‘I am going to stop by your room before you get discharged to help you set up your six-week follow-up appointment.’ Then, I would come by and see the patients in their room and conduct the first set of surveys with them and kind of assess the situation.”—Navigator |

| Helping with insurance issues | 6 | “If the patient was out of network and we weren’t able to help them out, we explained it to the navigator, so that if the patient questioned [the navigator], at least [the navigator] knew what to say and wasn’t so confused about the process as well.”—Nurse |

| Helping with transportation issues | 4 | “The navigator helped patients to get what they needed despite any obstacles that were in the way, or sometimes going above and beyond and assisting patients, you know, get to their appointments. If they didn’t have money to get on the bus or whatever, the navigator was, you know, making a way to make sure that they got here and then they got what they needed.”—Patient care technician |

| Provided patients with readily-available contact | 7 | “I think that having one or two consistent people that people can talk to and communicate with directly rather than having to go through Northwestern [central phone desk] is helpful.”—Fellow |

| Social support and health education | ||

| Providing emotional support to patients | 12 | “The fact that the navigator was there representing the clinic so that [the patients] know that there is actually a human element about this. … that is the one thing.”— Clerical staff |

| Facilitating breastfeeding continuation | 10 | “If the patient felt like they didn’t get good breastfeeding support and they needed help with breastfeeding, they knew their navigator was associated with the study clinic. So their navigator would say to me, ‘Can you come see this patient’ and we kind of team-worked together or we would go over together.”—Breastfeeding peer counselor |

| Providing contraception education | 9 | “I focused on making sure that they had a birth control picked out and if not educate them on the different types of birth control. I gave them a packet and helped them kind of look through and see. … I mean, obviously I would refer them back to the doctor if they had any medical questions, but generally speaking I would come in, do the surveys, and educate them on birth control options.”—Navigator |

| Encouraging prioritization of self-care for new mothers | 8 | “A lot of the moms have a lot going on and sometimes put their own health needs and requirements to the side after they have a newborn. Having a navigator kind of gives it to somebody else to try to help coordinate their own schedules and make sure that they can follow up appropriately.”—Resident |

| Facilitating depression screenings | 3 | “[The navigators] were very good at making sure we actually got our [Patient Health Questionnaire]-9 depression screens done.”—Resident |

Next, interviews covered four major evaluation categories as follows: provider satisfaction and perceived program benefits, perceived clinical and administrative outcomes, suggestions for improvement, and suggestions for patient population expansion. Themes identified in each of these categories are summarized and quantified (by proportion of respondents who described this theme) in ►Table 6. Further examples of ►Table 5 themes can be found in ►Tables 7 and 8.

Table 6.

Summary of themes generated by provider stakeholders regarding navigation program outcomes and areas for improvement

| Categories | Common themes | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived benefits of NNM and program satisfaction | Navigation should be sustained long-term | 18 (100) |

| Navigators did not inhibit normal clinic flow | 18 (100) | |

| Providers and navigators had positive overall relationship | 18 (100) | |

| Navigators facilitated coordination of care between providers | 14 (78) | |

| Patients and navigators formed strong relationships | 13 (72) | |

| Navigators scheduled postpartum appointment while patients were still in-patients | 12 (67) | |

| Navigators helped follow-up with patients | 12 (67) | |

| Providers and navigators regularly communicated about patients and their additional needs | 11 (61) | |

| Navigators reduced burden to clinic providers | 10 (56) | |

| Navigators improved provider ability to provide care | 10 (56) | |

| Navigators reminded patients of postpartum appointments regularly | 7 (39) | |

| Navigators provided patients with readily-available contact for questions and logistical issues | 7 (39) | |

| Clinical and administrative improvements of NNM | Increased postpartum appointment attendance | 17 (94) |

| Increased contraception uptake | 13 (72) | |

| Increased breastfeeding support | 8 (44) | |

| Increased quality of postpartum appointments | 7 (39) | |

| Increased contraception education | 7 (39) | |

| Increased patient support | 6 (33) | |

| Increased patient satisfaction with care | 6 (33) | |

| Decreased patient anxiety during appointment | 6 (33) | |

| Increased patient trust in health care systems | 4 (22) | |

| Suggestions for improvement | More medically knowledgeable navigators | 7 (39) |

| More communication with physician providers, even though the program could run independently of physician input | 7 (39) | |

| More discussion on postpartum appointment preparation with patients | 2 (11) | |

| More general postpartum education for patients | 2 (11) | |

| Suggestions for patient population expansions | Non-English speaking or poor health literacy patients | 12 (67) |

| Socially, economically, or mentally high-risk patients | 11 (61) | |

| Pregnant patients | 11 (61) | |

| Young patients | 10 (56) | |

| Medically or obstetrically high-risk pregnant patients | 6 (33) | |

| Abnormal pap smear patients | 3 (17) | |

| Gynecologic surgery patients | 3 (17) |

Abbreviations: NNM, navigating new motherhood.

Table 7.

Provider stakeholder satisfaction and perceived benefits of the postpartum patient navigation program

| Common themes | n | Example excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Should be sustained long-term | 18 | “I think [sustaining navigation] all comes down to the patients. … I think if the patients thought it was helpful: … it may have helped them either feel like they had an additional resource, feel like they had someone to help them understand sort of the path of their (… postpartum) care, I think it’s only a win if the patients think so, you know, I think the idea is certainly wonderful and I think if the patients see benefit then it is something we should absolutely continue.”—Resident |

| Did not inhibit normal clinic flow | 18 | “She made her presence known which I think is really important, but she was very respectful and like kind of made you aware that she was there to help you but she wasn’t like in your way”—Fellow |

| Had overall positive interactions with navigator | 18 | “[The navigators] were very good. It was a very positive thing. The right people were doing them definitely. They were made for the role I think. … very approachable people that relate and empathize with our population.”—Clerical staff |

| Facilitated coordination of care between providers | 14 | “There were some instances where she would tell me ‘oh your patient can’t come on this day so I rescheduled her,’ so that was really helpful because I could tell that somebody else was keeping track. I think it was probably more helpful for the resident clinic. … the patients are seeing different residents at different times so it is really hard for the residents to keep track of all of their patients, so having someone to help keep track, I am sure, was really helpful.”—Fellow |

| Formed strong patient-navigator relationships | 13 | I would say whoever is the navigator will have to have a wonderful personality like [our navigator] did. … she has a personality who gets along with different kinds of different personalities. … I think the patients have to feel comfortable with who they speak. Some patients are guarded so just whoever were to take on this role just has to be a people person.”—Nurse |

| Had regular provider-navigator communication about patients’ needs | 11 | “I remember there was like one patient who was coming in for her postpartum [appointment], and she needed to have her Glucola because she had gestational diabetes, and [the navigator] was like, ‘Oh, she is coming in for her Glucola’ to remind me. … that was kind of nice that she already knew what each patient needed when they came in.”—Fellow |

| Improved provider ability to provide care | 10 | “I don’t know how much the navigators talked about stuff with the patients, but [the patients] definitely sort of came, I think, and were able to kind of discuss what had been going on a little bit better. So, I just felt like when we were having the appointment, we got a lot more out of it than we’ve had in the past.”—Resident |

| Reduced burden to clinic providers | 10 | “[The navigators] would either call or text us or send us a message and we scheduled for her (patient). It was easier for us because that was one less phone call we were getting from the patient to schedule.”—Clerical staff |

Table 8.

Challenges and areas for improvement with postpartum patient navigation program

| Common themes | n | Example excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| More communication with physician providers, though the program could run independently of physician input |

7 | “Although I benefitted from the program as a doctor,… I think probably it could have been more explicitly told to us. … We probably could have [coordinated more] with a lot of the [NNM] coordinators if we had a better sense of what was going on.”— Resident |

| More medically knowledgeable navigators | 7 | “Having the navigators trained in things regarding like contraception, postpartum mood changes. … It wouldn’t be their role to take care of that for the patients but at least maybe have some more education and understanding themselves so they can assist the patient more.”—Social worker |

| More discussion on postpartum appointment preparation with patients |

2 | “Things I think could be more helpful for the future is, I think we learned more about the gestational diabetes patients as we were doing the program. Upfront, we didn’t make it part of our protocol to officially remind them multiple times that they need to be fasting, that they need to plan for two hours. …making sure that information would have been crystal clear, I think, really important.”—Navigator |

| More general postpartum education for patients | 2 | “If we were to expand the program, I think we should add … a health educator (component) where the navigators are able to do a lot of the postpartum rounding that the residents didn’t do whether that’s contraceptive counseling, helping with lactation, helping facilitate with patient services, helping to get the patients connected to the lactation peer counselor in the office, you know, I really think that that’s the next step in terms of what’s feasible.”—Resident |

First, provider stakeholders were queried regarding perceived benefits of NNM and their satisfaction with the program. Provider stakeholders unanimously agreed that the program was implemented well, provided a valuable service to patients, and should be sustained (►Table 7). Provider stakeholders did not report that the navigator’s presence impeded clinic flow or otherwise negatively impacted clinical care. Rather, provider stakeholders described the navigators were well-integrated, worked well with the team, frequently communicated with clinic staff, and provided a bridge between patients and providers (►Table 7). For example, regarding patient medical inquiries, one nurse explained, “(The navigator) would call us and let us know what was going on, and then we would reach out to the patient. Instead of like, telling the patient to just call the clinic, she actually tried to make sure all of us knew that there was a link.”

Second, interviewees viewed navigators as having improved both administrative and clinical outcomes. Provider stakeholders not only perceived the navigation program as improving clinical communication, but they also reported it helped them to provide better care and improved subjective and objective patient outcomes (►Table 6). The most common perceived outcomes were increase in postpartum attendance (n = 17), contraception uptake (n = 13), and breastfeeding counseling (n = 8). Provider stakeholders also perceived improvements in depression screening, quality of postpartum appointment, continuity of care, patient satisfaction, and patient support. For example, one fellow noted she perceived patients were more likely to get their desired contraception during the study period, stating, “If they want a Nexplanon, for example, they need to have a Nexplanon-certified provider in the clinic, so … she (the navigator) worked with the clinic coordinator a lot, to make sure patients were scheduled for days when they could actually get the Nexplanon.” From the administrative viewpoint, provider stakeholders saw navigators reduce the scheduling burden of patient and provider stakeholders and increase coordination of care between residents rotating through clinic (►Table 6).

Third, though NNM successfully improved many clinical patient outcomes24 and aligned well with the goals of various patient and provider stakeholders, interviewees noted limitations in program design and implementation (►Table 8). Some resident physicians felt disconnected from the program due to lack of formal communication between them and the navigators and were thus unsure of the extent to which navigators were following-up with their patients. Seven interviewees noted that NNM navigators were not medically experienced or medically knowledgeable and suggested using medical professionals as navigators in future programs. Provider stakeholders also would have liked the navigator to educate and better prepare patients for their postpartum appointments, rather than focusing on appointment attendance. For example, one fellow mentioned it would be beneficial for navigators to inform patients who had gestational diabetes that the oral glucose tolerance test administered at the postpartum appointment would require them to be fasting.

Finally, when asked about possible populations in which women’s health patient navigation could be beneficial outside the scope of this study, provider stakeholders described a range of potential patient beneficiaries (►Table 6). A majority described navigation as being potentially helpful for non-English speaking, teenage, and other socially or medically high-risk patients. Importantly, provider stakeholders widely believed that patient navigation programs should continue to focus on socially, economically, or mentally high-risk patient populations.

Discussion

Patient navigation has significant potential to improve health care access and health outcomes for low-income women in the postpartum period. NNM was a postpartum patient navigation program aimed at improving postpartum care received in a population of largely minority, low-income women.24 This program was designed to improve patient outcomes by integrating one-on-one support into a preexisting clinical structure without interrupting typical workflow.24 In this study, we assessed patient and provider stakeholder feedback on NNM performance. Patient satisfaction surveys suggested that patients perceived navigation to be beneficial, with the vast majority of women reporting positive experiences with their navigator. Next, although provider stakeholders had limited previous experience with navigation and were generally uninvolved with NNM processes, they accurately discerned navigation processes, as well as several program benefits. Major program benefits perceived by provider stakeholders were well-aligned with the measured clinical outcomes of the program.24 Other perceived benefits included emotional and logistical support, patient education, and improved continuity of care, all of which are consistent with findings of other navigation programs.28,29 Provider stakeholders also noted successful integration of navigation into clinic.

Our findings align with the few previous studies that have examined patient navigation’s effects on patient and provider satisfaction. Like the present study, a provider stakeholder feedback study conducted on an oncology navigation program in DuPage County, IL, also showed positive provider stakeholder perceptions of navigation, including beliefs that navigation enhances clinical services and reduces workload of clinic staff.22 A qualitative patient and provider evaluation of a patient navigation program for Latinos with severe mental illnesses found that patients viewed navigators as sources of emotional support, informational support, assistance with navigating the health care system, and increased continuity of care.30 Like provider stakeholders in the present study, patient navigators in the mental health program also saw a need for more communication between the navigation team and clinic providers, as well as advocated for additional training needs of patient navigators.30 As in our study, prior work suggests that another area for improvement is educating provider stakeholders about navigation’s goal which is to connect patients with a nonmedical source of interpersonal and systems support. Another study observing differences between highly effective and less effective sites of patient navigation found that navigators operating at highly effective sites more actively collaborated with clinical staff by more frequently coordinating referrals with providers, facilitating communication between patients and providers, and working with providers to complete paperwork, such as health insurance forms.31 These previous studies support the present study’s findings regarding navigator roles, as well as patients’ and provider stakeholders’ satisfaction and criticisms.

This evaluation revealed areas for improvements in the clinic, as well as in the navigation program. For example, provider stakeholders’ feedback identified that one major area benefitted by navigation was the facilitation of contraception approvals and logistical requirements which aligns with the primary study’s outcome of improved uptake of high-quality contraception with navigation. These findings suggest a potential clinic improvement may be implemented by having dedicated staff to manage contraception approvals. Regarding navigation processes, some comments of provider stakeholder suggested that NNM did not successfully educate providers regarding navigation goals; for example, some suggested increased navigation intervention in patients’ care tasks, such as coordinating laboratory tests, whereas this task may be better fulfilled by health care professionals who can appropriately explain the medical rationale and procedures for such tests. Providers also desired more knowledge about the general goals of navigation. Future programs should consider methods to better educate providers about navigation goals and to integrate providers into the program without adding logistical burdens to already busy clinical schedules. This finding also demonstrates provider stakeholders viewed navigation primarily as a burden-reducing intervention, rather than as an opportunity to learn from navigation techniques, such as relationship-building and intentional communication, and to improve based on the care deficiencies identified via navigation. Indeed, this evaluation identified a shortcoming of NNM in fully educating providers, but it also demonstrated how navigation processes can highlight areas for improvement in the health care setting itself. Rather than being a permanent solution, we posit that navigation should reveal areas of care processes in need of change and teach us how to improve systems on a clinic-based and broader level.

Major strengths of this study are the inclusion of multiple diverse patient and provider stakeholders and the use of rigorous mixed methodology. All invited provider stakeholder participants agreed to participate in the study, and all full-time clinic staff were represented. Additionally, this study more comprehensively evaluated NNM than prior published navigation program evaluations; in addition to complete validated satisfaction surveys, patients were given the opportunity to provide open-ended comments about their experiences, while provider stakeholders were given opportunities to discuss several program aspects. These interviews were assessed using rigorous, reproducible methods by analysts who were not clinic staff members, supervisors of interviewees, or part of the NNM implementation team. Additionally, the interviews were performed immediately after NNM completion such that provider stakeholders had recent memories of the program. Moreover, interviews were conducted before the actual NNM study results had been presented; thus, most interviewees were unaware of health outcomes related to the program when sharing perceptions.

Limitations

There are limitations of this evaluation. First, selection bias likely exists within the PSN-I survey score data, as this follow-up survey was only completed for patients who returned for their postpartum appointment, and these patients may have been more satisfied with their interpersonal relationship with their navigator than those who did not return. Regarding provider stakeholder interviews, although interviewees did not know the interviewers well prior to the interview, there may also be a potential for social desirability bias, although both positive and negative feedbacks were requested. Additionally, NNM was implemented in a specific setting within a large academic center. Thus, while we believe these results may help to improve and expand navigation programs, particularly in the field of reproductive health, findings may not be fully generalizable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patient navigation in the postpartum period was perceived as highly beneficial by patients and provider stakeholders alike. This perception suggests that extension of the patient navigation program beyond the study period would likely maintain patient and provider support, and efforts to implement such a program for similar patient populations could be equally welcomed. As patient navigation programs are still new in perinatal care, further work must be done to optimize programs with respect to efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and other measures.32 It is also essential to continue both qualitative and quantitative assessment of navigation programs through frequent feedback from participants of varying perspectives. Such assessments may demonstrate how navigation programs can be beneficial in and of themselves but, perhaps more importantly, may also highlight areas for long-term systems improvement in provision of perinatal care and provide techniques to enact them.

Funding

Navigating New Motherhood was supported by the Northwestern Memorial Foundation/Friends of Prentice FY 2015 Grants Initiative. L.M.Y. is supported by the NICHD K12 HD050121-11.

Footnotes

Note

This study was presented as a poster at the Society for Reproductive Investigation 65th Annual Scientific Meeting, Orlando, FL, March 2017.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Committee opinion no. 666: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127(06):e187–e192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harney C, Dude A, Haider S. Factors associated with short interpregnancy interval in women who plan postpartum LARC: a retrospective study. Contraception 2017;95(03):245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu MC, Prentice J. The postpartum visit: risk factors for nonuse and association with breast-feeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187(05):1329–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant AS, Haas JS, McElrath TF, McCormick MC. Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in healthy start project areas. Matern Child Health J 2006;10(06):511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Use of postpartum care: predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy 2014;2014:530769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of non-attendance to the postpartum follow-up visit. Matern Child Health J 2016;20 (Suppl 1):22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rankin KM, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, Handler A. Healthcare utilization in the postpartum period among Illinois women with Medicaid paid claims for delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J 2016;20(Suppl 1):144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bromley E, Nunes A, Phipps MG. Disparities in pregnancy healthcare utilization between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women in Rhode Island. Matern Child Health J 2012;16(08):1576–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. ; Patient Navigation Research Program. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer 2008;113(08):1999–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer 2007;109(2, Suppl):359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon MA, Tom LS, Nonzee NJ, et al. Evaluating a bilingual patient navigation program for uninsured women with abnormal screening tests for breast and cervical cancer: implications for future navigator research. Am J Public Health 2015;105(05):e87–e94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markossian TW, Darnell JS, Calhoun EA. Follow-up and timeliness after an abnormal cancer screening among underserved, urban women in a patient navigation program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21(10):1691–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paskett ED, Dudley D, Young GS, et al. ; PNRP Investigators. Impact of patient navigation interventions on timely diagnostic follow up for abnormal cervical screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25 (01):15–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman HJ, LaVerda NL, Young HA, et al. Patient navigation significantly reduces delays in breast cancer diagnosis in the District of Columbia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012; 21(10):1655–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenney KM, Martinez NG, Yee LM. Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(03):280–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush ML, Kaufman MR, Shackleford T. Adherence in the cancer care setting: a systematic review of patient navigation to traverse barriers. J Cancer Educ 2018;33(06):1222–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuland DS, Brenner AT, Hoffman R, et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(07):967–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallington S, Oppong B, Dash C, et al. A community-based outreach navigator approach to establishing partnerships for a safety net mammography screening center. J Cancer Educ 2018; 33(04):782–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castaldi M, Safadjou S, Elrafei T, McNelis J. A multidisciplinary patient navigation program improves compliance with adjuvant breast cancer therapy in a public hospital. Am J Med Qual 2017;32(04):406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baik SH, Gallo LC, Wells KJ. Patient navigation in breast cancer treatment and survivorship: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(30):3686–3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battaglia TA, Darnell JS, Ko N, et al. The impact of patient navigation on the delivery of diagnostic breast cancer care in the National Patient Navigation Research Program: a prospective meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;158(03):523–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de la Riva EE, Hajjar N, Tom LS, Phillips S, Dong X, Simon MA. Providers’ views on a community-wide patient navigation program: implications for dissemination and future implementation. Health Promot Pract 2016;17(03):382–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabitova G, Burke NJ. Improving healthcare empowerment through breast cancer patient navigation: a mixed methods evaluation in a safety-net setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee LM, Martinez NG, Nguyen AT, Hajjar N, Chen MJ, Simon MA. Using a patient navigator to improve postpartum care in an urban women’s health clinic. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(05):925–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Winters PC, et al. ; Patient Navigation Research Program Group. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: a multi-site patient navigation research program study. Psychooncology 2012;21(09):986–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jean-Pierre P, Winters PC, Clark JA, et al. ; Patient Navigation Research Program Group. Do better-rated navigators improve patient satisfaction with cancer-related care? J Cancer Educ 2013;28(03):527–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965;12(04):436–445 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan CH, Wilson S, McConigley R. Experiences of cancer patients in a patient navigation program: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports 2015;13(02):136–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotlib Conn L, Hammond Mobilio M, Rotstein OD, Blacker S. Cancer patient experience with navigation service in an urban hospital setting: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016; 25(01):132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan L, Torres A, Lara JL, et al. ; Latino Consumer Research Team. Qualitative evaluation of a peer navigator program for latinos with serious mental Illness. Adm Policy Ment Health 2018;45(03):495–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunn C, Battaglia TA, Parker VA, et al. What makes patient navigation most effective: defining useful tasks and networks. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2017;28(02):663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Battaglia T, et al. ; Patient Navigation Research Program. Costs and outcomes evaluation of patient navigation after abnormal cancer screening: evidence from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer 2014;120(04): 570–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]