Summary

Background

After the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, public health restrictions were introduced to slow COVID-19 transmission and prevent health systems overload globally. Work-from-home requirements, online schooling, and social isolation measures required adaptations that may have exposed parents and children to family violence, including intimate partner violence and child abuse and neglect, especially in the early days of the pandemic. Thus, we sought to: (1) examine the occurrence of family violence; (2) identify factors associated with family violence; and (3) identify relevant recommendations, from COVID-19 literature published up to 1 year after the pandemic declaration.

Methods

This review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021241622), employed rapid review methods, and extracted data from eligible papers in medical and health databases published between December 1, 2019 and March 11, 2021 in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Embase.

Findings

28 articles including 29 studies were included in the rapid review. While many studies of families/households revealed rises in family violence incidence, official justice, police, and emergency department records noted declines during the pandemic. Parental stress, burnout, mental distress (i.e. depression), difficulty managing COVID-19 measures, social isolation, and financial and occupational losses were related to increases in family violence. Health services should adopt approaches to prevent family violence, treat victims in the context of public health restrictions, and increase training for digital service usage by health and educational professionals.

Interpretation

Globally, restrictions aimed to limit the spread of COVID-19 may have increased the risk factors and incidence of family violence in communities. Official records of family violence may be biased toward under-reporting in the context of pandemics and should be interpreted with caution.

Funding

RESOLVE Alberta, Canada and the Emerging Leaders in the Americas Program (ELAP), Global Affairs Canada.

Keywords: Family violence, Child abuse and neglect, COVID-19, Rapid review, Global

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In the first year after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, three reviews of pandemic impacts on family violence were available, each with limitations.1, 2, 3 In one review, it was unclear if child abuse and neglect (CAN) was included and recommendations to address family violence were not offered.1 Other reviews focused on prevention and intervention research rather than risk factors,2 or did not rely on data since the pandemic onset.3 To address these limitations, we undertook a rapid review of published health and medicine literature to examine the occurrence of family violence up to one year after the pandemic declaration, to identify factors associated with family violence and relevant recommendations. We searched literature published between December 1, 2019 and March 11, 2021 using iterations of search terms including COVID-19, pandemic, quarantine, social isolation, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, gender-based violence, child abuse, verbal abuse, physical abuse, psychological abuse, and sexual abuse.

Added value of this study

This study adds value to existing evidence by: (1) including a wide range of definitions of family violence including intimate partner violence and CAN, relying on both self-report and official records, (2) focusing on identification of risk factors for family violence in the context of COVID-19, and (3) providing recommendations to address family violence in the context of COVID-19.

Implications of all the available evidence

Supported by two reviews,2,4 findings revealed that many self-report studies of community households showed a rise of family violence incidence, while official records noted an overall decline during the pandemic. Multiple factors appeared to increase the risk for family violence including parental distress, difficulty managing COVID-19 measures, social isolation, and financial losses. Key recommendations include health professionals adopting approaches to prevent family violence and to treat victims in the context of public health restrictions, as well as health and educational professionals attaining training for digital service use and care delivery.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2.5 After first gaining international attention in December, 2019, COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020, due to its rapid spread through the transmission of viral droplets by individuals in close contact.5 A range of COVID-19 public health restrictions were implemented around the world to limit viral transmission and decrease hospitalisation rates including self-isolation for suspected or demonstrated exposures of illness, lockdowns of communities in whole or part, elimination or limits on social gatherings, transition of primary and secondary schooling to online learning from home, and work-from-home requirements. 2,3,6,4 These restrictions increased the risk for mental health concerns, isolation, loneliness, economic vulnerability, job loss, and business closures and failures that heavily impacted families.6 While many families7 and relevant support systems2,3,8,9 adapted to the pandemic over time, impacts may have been greatest in the first year of the pandemic, and potentially contributed to increased family violence, specifically intimate partner violence (IPV) and child abuse and neglect (CAN).2,8,10

Pre-pandemic, 30% of women aged 15 and over experienced IPV during their lifetimes, with regional variation ranging from a low of 16% in East Asia to a high of 65% in Sub-Saharan Central Africa.11 IPV includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by a current or former spouse or non-marital partner in the context of coercive control, which includes threats, humiliation, intimidation and other abuse meant to harm, punish, or frighten the victim.12 Studies conducted prior to the pandemic showed that women who considered their partners to be controlling experienced higher rates of IPV.13 Women comprise the majority of victims, and IPV is linked to a wide range of physical and mental health problems that may persist long after the abuse ends.14 Exposure to IPV is recognised as a form of CAN with child witnesses at increased risk for psychological and behavioural problems.15

CAN includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and neglect toward children (0 to 18 years of age inclusive) that causes substantial adverse health, educational, and behavioral consequences through the lifespan.16 Globally, the prevalence of any type of child abuse ranges from a low of 3% (sexual abuse) in the United Kingdom to 72% (emotional abuse) in China and for neglect ranges from 3% in Denmark to 36% in Hong Kong.16 CAN is considered toxic to children's healthy development16 as the associated stress contributes to prolonged stimulation of the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary axis resulting in poorer developmental outcomes of the cardiovascular, immune, and metabolic systems.17 Further, exposure to both IPV and CAN increases the risk for emotional-behavioral difficulties in childhood and mental health problems, substance abuse, and IPV in adulthood, suggesting intergenerational impacts.18

Controlling abusers often monitor their victims’ communications, cut off or regulate internet or telephone service, and refuse to allow their victims to leave the home,18,19 all of which can be more easily achieved with the COVID-19 restrictions.10 IPV and CAN victims may also demonstrate increased hesitancy to reach out to mental health providers, shelters, or police due to fear of contracting COVID-19 or close proximity to controlling abusers,18 who may restrict victims from seeking safety or assistance from family, friends, or service providers.18,19 Children typically require help outside the home environment to report the violence,20 with teachers and health professionals most often responsible for reporting CAN.21 However, COVID-19 prevention measures abruptly separated children from positive and supportive relationships with such professionals in schools as well as with extended family, and other members of their community who may notice CAN.21,22

Globally, more than 168 million children were estimated to be affected by school closures in 2020 and 2021.23 School closures strained and burdened parents, forcing them to adapt to the new reality of managing working from home, while maintaining their households, caring for children, and assisting children with online school if needed.24 Compounding this situation, parents were affected by unemployment and financial insecurity. For example, a 15.5% drop in employment was observed in Canada alone when comparing April 2020 to April 2019, reflecting a decrease of 2.7 million employment positions and demonstrating increased occupational and financial instability.25 Globally, the gross domestic product was forecast to fall by 2% overall, and 2.5% for developing countries, and 1.8% for industrial countries, declines of nearly 4% below the world benchmark.26 Financial insecurity is linked to a host of outcomes including stress and distress such as depression and anxiety, particularly in male intimate partners.27 Parental burnout, defined as a reduction in caregiving abilities due to parental exhaustion resulting from parental responsibilities and chronic stress, is also likely when parents have low levels of social support and lack leisure time.28

The pandemic likely stressed intimate partner relationships, negatively affecting partners’ abilities to meet each other's needs for intimacy and affection.28 Further, parental burnout and mental distress such as depression or anxiety increase the risk of conflict and violent behaviors such as CAN29 and IPV through a dose-response relationship.28,30 .Maternal depressive symptoms, for example, may negatively impact children's internalising and externalising behaviours, due to increased use of psychological and physical violence.30 Economic stress, mental distress, and parental burnout all increase the risk for developing harmful coping mechanisms, such as excessive alcohol consumption and substance misuse,31 with one study showing increased parental alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic.32 Excessive alcohol consumption is also linked to increased risk for IPV and CAN.26,33 Parental burnout may cause fatigue and decreased engagement that may impede healthy parenting.28 Parents affected by mental health problems such as depression or substance abuse often have reduced capacity to respond appropriately to children's needs, increasing the risk for CAN.30

The objective of this study was to rapidly review COVID-19 literature published up to and including the one-year anniversary of the pandemic declaration in order to: (1) examine family violence (including IPV and CAN) occurrence during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) examine factors that contribute to family violence during the pandemic; and (3) identify relevant recommendations to address family violence during this and future pandemics. We did not seek to specify causation between COVID-19 public health measures and family violence or to demonstrate change, rather our intention was to describe and offer recommendations.

Methods

This rapid review was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42021241622) and conducted in accordance with the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools guidelines.34 We report on the methods for the review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A rapid review method was selected to enable a timely review of the literature and identify pertinent recommendations that could be acted upon in the context of COVID-19. Ethical approval was not required for this study as data were derived from already published studies.

Search strategy

The search focused on four health-related databases from medicine, psychology, nursing and allied health, and rapid review methods excluded searching grey literature and reference lists of identified sources to expedite data collection.35 The sources used for searching the literature consisted of: MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to March 10, 2021, (OVID); Embase 1974 to 2021 March 10 (OVID); APA PsycInfo 1806 to March Week 1, 2021 (OVID); and CINAHL Plus with Full Text (Ebsco) to March 10, 2021. The search strategy was developed by an expert health sciences librarian (KH) in collaboration with the research team. Searches were conducted between March 11, 2021 and April 2, 2021 to attain literature published between December 1, 2019 and March 11, 2021. The search strategy was developed in Medline (OVID) and included two main themes: family violence (including IPV and CAN) and COVID-19 pandemic.36 Keywords and subject headings were used for each concept, where subject headings were adapted according to each database's indexing (Table 1). All search strategies are available in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Database(s): Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub ahead of print, in-process, in-data-review & other non-indexed citations and daily 1946 to March 11, 2021.

| 1 | exp coronavirus infections/ or COVID-19/ |

| 2 | epidemics/ or disease outbreaks/ or pandemics/ |

| 3 | (cornoavirus* or 2019-ncov or ncov19 or ncov-19 or 2019-novel Cov or ncov or covid or covid19 or COVID-19 or covid 2019 or "coronavirus 2" or sars-cov2 or sars-cov-2 or sarscov2 or sarscov-2 or Sars-coronavirus2 or sars-coronavirus-2 or SARS-like coronavirus* or coronavirus-19 or corna virus* or novel coronavirus*).mp. |

| 4 | ((novel or new or nouveau) adj2 (CoV or nCoV or covid or coronavirus* or corona virus or Pandemic*2)).mp. |

| 5 | Quarantine/ or Social Isolation/ or physical distancing/ |

| 6 | (lockdown* or lock down* or quarantin*).tw,kf. |

| 7 | ((social or physical) adj2 (isolat* or distanc*)).tw,kf. |

| 8 | or/1-7 |

| 9 | intimate partner violence/ or spouse abuse/ or domestic violence/ or Gender-Based Violence/ |

| 10 | child abuse/ or child abuse, sexual/ |

| 11 | Physical Abuse/ or Emotional Abuse/ or Punishment/ |

| 12 | sex offenses/ or rape/ |

| 13 | (child* adj2 (abus* or maltreat* or neglect)).tw,kf. |

| 14 | ((intimate or partner or spouse or spousal or family or familial or domestic or interpersonal or gender or inter parental or interparental) adj2 violence).tw,kf. |

| 15 | ((sex* or physical or psychological or verbal or emotional) adj2 (abus* or violence)).tw,kf. |

| 16 | ((physical or emotional or psychological) adj2 neglect).tw,kf. |

| 17 | ((corporal or physical) adj2 punishment).tw,kf. |

| 18 | ((verbal or physical or psychological) adj2 aggression).tw,kf. |

| 19 | or/9-18 |

| 20 | 8 and 19 |

| 21 | 20 and 20191201:20301231.(dt). |

| 22 | limit 19 to COVID-19 |

| 23 | 21 or 22 |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included studies: (1) were eligible papers in medical and health databases, (2) were studies published in peer-reviewed journals; (3) were written in English, Portuguese, or French as languages spoken by the team of reviewers; (4) contained data related to family violence (IPV or CAN) during the COVID-19 pandemic; (5) were descriptive or observational studies; and (6) examined families with children up to 18 years of age inclusive. Opinion papers, letters to the editor, grey literature (e.g., newspaper articles), qualitative studies, dissertations, and conference abstracts were excluded. Specifically, five types of family violence were investigated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of violence explored in the rapid review and associated definitions.

| Type of violence | Definition for the purpose of this study |

|---|---|

| Physical Violence of a Family Member | The intentional use of force against a family member without their consent. The use of force can cause physical pain or injury that may last a long time.37 For children, this includes those from birth to 18 years inclusive. |

| Emotional Abuse of a Family Member | A pattern of behaviour in which one person in a family deliberately and repeatedly subjects another to nonphysical acts detrimental to behavioral and affective functioning and overall mental well-being.38 For children, this includes those from birth to 18 years inclusive. |

| Sexual Violence of a Family Member | Any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against a person's sexuality using coercion. This is by any person in a family.12 For children, this includes those from birth to 18 years inclusive. |

| Emotional Abuse of Children | Focused on children from birth to 18 years inclusive, failure of a parent or caregiver to provide an appropriate and supportive environment, and includes acts that have an adverse effect on the emotional health and development of a child, including restricting a child's movements, denigration, ridicule, threats and intimidation, discrimination, rejection and other nonphysical forms of hostile treatment.12 |

| Child Neglect | Focused on children from birth to 18 years inclusive, failure of a parent or caregiver to provide for the development of the child – where the parent is in a position to do so – in one or more of the following areas: health, education, emotional development, nutrition, shelter and safe living conditions.12 |

Study selection and data extraction

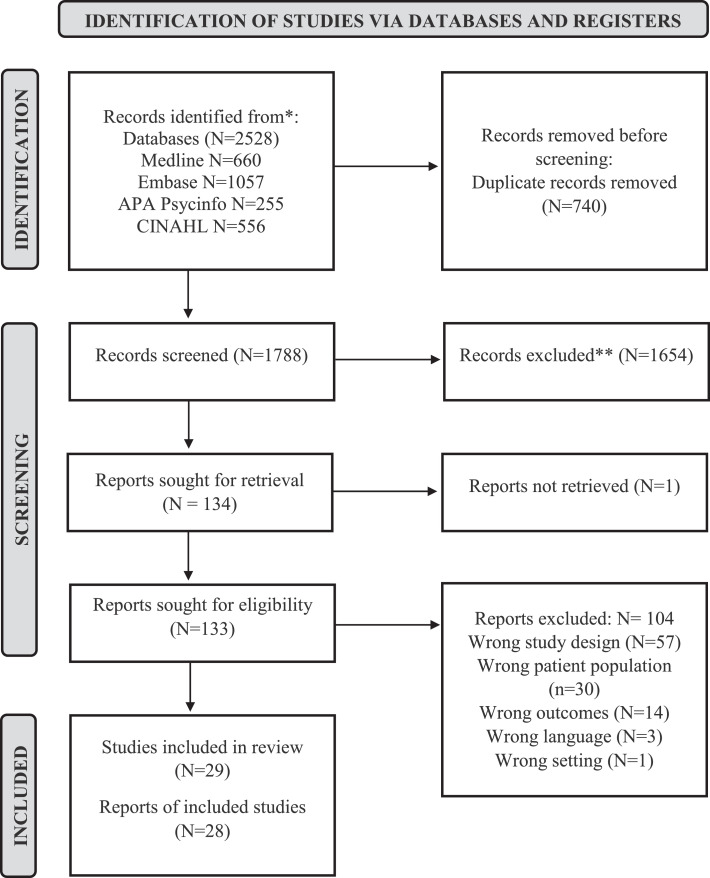

All database search results were uploaded to Covidence, an online screening and data extraction tool,39 where they were auto-deduplicated. A calibration exercise using 50 randomly selected titles and abstracts was first conducted with Excel to ensure the inclusion/exclusion selection criteria were applied consistently amongst all reviewers, and to clarify the selection criteria. Two reviewers (ML, SK) independently screened the titles and abstracts, followed by the full-texts using Covidence. In case of conflict, the reviewers consulted one another and made a mutual decision. A third reviewer (NL) made the final decisions when no consensus could be reached. 2528 articles were initially identified through the search. After screening, 28 reports, including 29 studies, met all inclusion criteria and addressed the research question (Figure 1). To facilitate speed of completion in this rapid review, two reviewers (ML, SK) extracted the data, and NL checked work for accuracy and completeness.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Critical appraisal

To assess the validity of included studies, a critical appraisal was completed using the evidence-based librarianship (EBL) checklist.40 This critical appraisal checklist was selected as it allows for the evaluation of diverse study designs and methods. The EBL checklist consists of 26 different questions reflecting the quality of the sample, data collection, study design, and results.40 Each question can be answered with “yes”, “no”, “unclear” or “not applicable” and 1 point is given for every “yes” response.40 According to the EBL checklist recommendation, a study is rated valid overall if the percent of “yes” responses out of the sum of all responses, excluding not applicable, is equal to or greater than 75%.40 Any studies below 75% are considered as being less valid. In this review, two reviewers examined each study independently (ML, SK), subsequently compared results to determine agreement, and together verified the underlying data. In case of dispute, a third reviewer (NL) provided the final rating. Risk of bias was not explicitly assessed in this review, however, the EBL checklist has components assessing for bias. (In the review registration, we selected a different critical appraisal tool that ultimately did not allow the team to appraise the broad range of study designs that were retrieved for analysis. Thus the EBL selection represents a change from the registration protocol.)

Data analysis and synthesis

As planned in our registered review protocol, studies were described with percentages and frequencies and categorised according to similarities and differences. The exposure variable was considered to be COVID-19 and the outcome was family violence, and we undertook a narrative synthesis of findings from included studies and created summary tables to descriptively quantify family violence occurrence during the COVID-19 pandemic, examine factors that contribute to family violence during the pandemic, and identify relevant recommendations.

Role of the funding source

Funding was provided by RESOLVE Alberta and the Emerging Leaders in the Americas Program (ELAP) which provided funding for research assistants and students. All authors had access to the data and contributed to the decision to submit for publication. The funding sponsors did not participate in the study.

Results

Critical appraisal results

After resolving four disagreements between the reviewers, six studies were deemed to have lower quality, with validity scores ranging from 29% to 71%,41, 42, 43, 44 based on the quality of sample selection and data collection, whereas the study design and results were generally considered valid. For this latter reason, they were retained for review. The rest of the studies were considered to be of acceptable to high quality with validity scores ranging from 75% to 100%. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of scores on EBL Critical Appraisal Checklist for included studies.

| Included Studies with Descriptive Data on Family Violence Occurence |

Included Studies on Factors Associated with Family Violence Occurence |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBL Checklist Items | Barboza, et al., 202045 | Dapic, et al., 202043 | McLay, 202046 | Musser, et al., 202147 | Rapoport, et al., 202048 | Whelan, et al., 202049 | Chong, et al., 202050 | Holland, et al., 202151 | Kaiser, et al., 202152 | Swedo, et al., 202053 | Hamadani, et al., 202054 | Kimura, et al., 202155 | Mahmood, et al., 202156 | Malkawi, et al., 202157 | #1 Rodriguez, et al., 202158 | #2 Rodriguez, et al., 202158 | Saji, et al., 202144 | Shah, et al., 202141 | Sharma, et al., 202159 | Tierolf, et al., 202160 | Bérubé, et al., 202061 | Calvano, et al., 202162 | Chung, et al., 202063 | Lawson, et al., 202064 | Lee, et al., 202165 | Manja, et al., 202042 | Pinchoff, et al., 202166 | Wong, et al., 202167 | Xu, et al., 202068 |

| Is the study population representative of all users, actual and eligible, who might be included in the study? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | X | X | X | X | √ | √ | X | X | X | X | √ | X | X |

| Are inclusion and exclusion criteria definitively outlined? | √ | X | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | X | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Is the sample size large enough for sufficiently precise estimates? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | √ | X | X | X | X | √ | X | X |

| Is the response rate large enough for sufficiently precise estimates? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Is the choice of population bias-free? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| If a comparative study…(multiple questions) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Was informed consent obtained? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Are data collection methods clearly described? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| If a face-to-face survey, were inter-observer and intra-observer bias reduced? | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | √ | n/a | n/a |

| Is the data collection instrument validated? | X | X | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ |

| If based on regularly collected statistics, are the statistics free from subjectivity? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | X | √ | X | X |

| Does the study measure the outcome at a time appropriate for capturing the intervention's effect? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | √ | X | X | X | X | X | √ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Is the instrument included in the publication? | √ | X | X | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ |

| Are questions posed clearly enough to be able to elicit precise answers? | X | X | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Were those involved in data collection not involved in delivering a service to the target population? | X | X | √ | √ | X | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Is the study type / methodology utilized appropriate? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Is there face validity? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Is the research methodology clearly stated at a level of detail that would allow its replication? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Was ethics approval obtained? | X | X | X | X | X | X | √ | X | X | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | X | X | √ | √ | X |

| Are the outcomes clearly stated and discussed in relation to the data collection? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Are all the results clearly outlined? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Are confounding variables accounted for? | √ | X | √ | √ | X | X | X | X | X | X | √ | √ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | √ | √ | X | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Do the conclusions accurately reflect the analysis? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Is subset analysis a minor, rather than a major, focus of the article? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Are suggestions provided for further areas to research? | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Is there e√ternal validity? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ |

| Total (%) | 75 | 29 | 83 | 83 | 64 | 67 | 75 | 75 | 79 | 79 | 92 | 96 | 75 | 88 | 79 | 79 | 71 | 58 | 88 | 79 | 79 | 88 | 79 | 75 | 86 | 42 | 92 | 76 | 79 |

Study characteristics

Out of the 28 eligible articles, 11 were completed in 202041, 42, 43,45, 46, 50, 53, 54, 63, 64, 68 and 17 in 2021.44,47, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 65, 66, 67 Of those, 13 were conducted in North America (United States and Canada),45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 58, 61, 64, 65, 68 nine were conducted in Asia (Bangladesh, China, India, Japan, Singapore),41,42,44,50,54,59, 63,65,67 three were conducted in Europe (Croatia, Germany, Netherlands),43,60,62 two were conducted in the Middle East (Iraq and Jordan),56,57 and one was conducted in Africa (Kenya).66 Rodriguez et al.58 consisted of two studies, creating a total of 29 included studies. All eligible studies were published in English; none of the Portuguese- or French-language studies met criteria. Studies were either done in families (n=19) with samples comprised of household members, or based on data from Emergency Department (ED), justice, or police records and databases (n=10). Sample sizes for family/household studies ranged from 8044 to 2424.54 Of the studies done using records from an ED, only one reported the sample size (n=58,367),50 and of those that used records from justice or police data, four reported the sample size which ranged from 461846 to 29,4462.47

Most studies were cross-sectional (n=15), however, eight studies were descriptive,43,46, 47, 48, 49, 50,51,53 three were longitudinal,55,58,66 one was a retrospective cohort,52 and one was an ecological study.45 Concerning the type of family violence, CAN was the primary type of violence investigated in 2042, 43, 44, 45,47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53,58,60,61,62,63,64,67,68 out of the 29 included studies. Other types of family violence investigated included violence between household members in the presence of a child (witnessing family violence) and IPV between the parents.

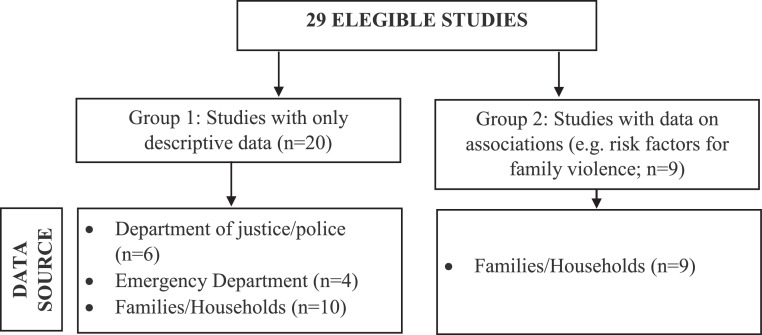

Results of studies with descriptive (Group 1) and association data (Group 2)

The studies were grouped as per Figure 2. Group 1 comprises the studies that used descriptive data on the occurrence of family violence before and after the onset of the pandemic. Group 2 consists of studies that examined factors (e.g. risks) associated with the occurrence of family violence during the pandemic.

Figure 2.

Categorisation of eligible studies and their data sources.

Family violence occurrence

Of the 20 studies with descriptive data in Group 1, six used justice and police records,43,45, 46, 47, 48, 49 four used ED records,50, 51, 52, 53 and 10 used data collected in families/households from spouses or parents and guardians such as grandparents.41,44,54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60

The six studies that used police and justice records showed an overall decline in the number of CAN reports during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the preceding period.43,45, 46, 47, 48, 49 four used ED records,50, 51, 52, 53 There was not only a decline in the number of CAN reports, but also a reduction in the filings of sexual abuse and family violence in the presence of a minor.49 However, an increase in the number of youth placed in foster care due to family violence was also reported in one of the six studies.47 Regarding the studies with ED records, three of the four studies showed that the number of hospital visits related to CAN was lower during the pandemic compared with the number of visits prior.51, 52, 53 The fourth study showed that while a greater proportion of children presented in the ED due to child abuse during the pandemic than prior, the mean number of child abuse injuries remained constant at about 1 per day.50

In contrast, all the studies undertaken in families/households showed an increase in family violence after the onset of the pandemic.41,44,54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 IPV (7/10 studies) and CAN (3/10 studies) were the two main types of family violence observed, with only one study60 examining both. Tierolf et al.’s study60 from the Netherlands was the only study in which family violence occurrence did not change with the onset of the pandemic; however, family violence was still reported as high, with frequent or serious violence before and after the pandemic was reported as 50.3% and 53.3%, respectively. Of those describing IPV, emotional and verbal abuse were identified as the most prominent types.54,56,59 Those examining CAN mostly identified shouting, verbal abuse, and neglect toward children, followed by physical violence.44,58 Hamadani et al.’s study54 from Bangladesh of IPV revealed that more than 50% of women reported an increase in emotional and physical violence and 8% reported increased sexual violence since pandemic onset. As well, Kimura et al.’s Japanese55 and Malkawi et al.’s Jordanian57 studies reported an increase of partner aggression of 2.4% and of family violence of 27.4%, respectively. In both American studies reported by Rodriguez et al.,58 there was an increase in physical and verbal abuse along with emotional neglect. Additionally, Shah et al.’s study44 from India found that parental behaviors such as verbal abuse and punishment increased by 25% and 27.1 %, respectively, in their sample of families of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). See Table 4 for details.

Table 4.

Characteristics of included studies with descriptive data (n=20).

| Authors, Year, Country | Objective and Hypothesis | Participants and study design | Type of violence | Measure of outcome | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies from Justice and Police Department Records (n=6) | |||||

| Barboza, et al., 2020,45 United States. | “To provide unique insights into the spatial and temporal distribution of child abuse and neglect (CAN) in relation to COVID-19 outcomes”.45p1) | Cases (n=661 pre-COVID-19; n=614 post COVID-19 onset) of CAN against children under 18 years reported to the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) from July 24th of 2019 to July 19th of 2020. Spatiotemporal ecological study. | CAN. | CAN in California as defined by Penal Code 273d and 270. | A decrease of 7.95% in the number of CAN reports during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the same time period immediately preceding it. |

| Dapic, et al., 2020,43 Croatia. | To analyze “trends of recent data of the Ministry of Interior with practical guidelines for improved child protection during the COVID-19 pandemic”.43(p1) | Registered number of children victims of mis-demeanour crime in the family, registered number of child abuse (CA) in the family, and number of criminal offences against children in the family (n=324 in March 2020; n=502 in March 2019) Descriptive study. |

CA classified as: misdemeanour crimes; criminal offense; or sexual abuse and exploitation. |

CA incidents. | A decrease of 35% in CA in March 2020 compared to the same time in the preceding year. Between January-March 2019 and the same period in 2020, there was a decrease of 31% in sexual abuse and exploitation offences against children. The number of registered perpetrators of family violence against children was 28% lower in 2020 than in 2019. |

| McLay, 2020,46 United States. | “The COVID-19 pandemic's impacts on domestic violence (DV) with the following research questions: 1) Did DV occurring during the pandemic differ on certain variables from cases occurring on a typical day the previous year? 2) Did DV occurring after the implementation of shelter-in-place orders differ (on these same variables) from cases occurring prior to shelter-in-place orders?”46(p1) | 4618 police reports on cases that occurred during the months of March 2019 and March 2020 were utilized from the Chicago Police Department (CPD). Descriptive study. |

Reports involving some kind of physical or sexual violence toward a person. These offences included any kind of assault, any kind of battery, homicide, criminal sexual assault, any sex offence against an adult, and any physical or sexual offences against children. | Occurrence of DV during COVID-19 pandemic, occurrence of DV during Shelter-in-Place order, sex crime, use of weapon, arrests, presence of child victim(s), and location of offense. | The number of child victims involved in March 2019 (3.55%) was more than the number during the pandemic (2.35%). A DV case with a child victim was 67% less likely (than cases without child victims) to have occurred during the shelter-in-place order. |

| Musser, et al., 2021,47 United States. | To “examine rates of documented, substantiated child maltreatment resulting in foster care placement, as well as demographic correlates of child maltreatment within the foster care system, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic”.47(p1) | Data from 294,462 youth aged 0–17 years were compiled from the State Automated Child Welfare Information System (SACWIS) maintained by Florida's Safe Families Network (FSFN) from January 1, 2001 through June 30, 2020. Descriptive study. |

Child maltreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, medical neglect, inadequate supervision, and emotional abuse and neglect. | Demographic and youth characteristics, child maltreatment and primary caregiver characteristics at removal. | There was a decrease of 24.08% in the number of youths placed in foster care in April, 2020 compared to April, 2019. The percentage of youth removed and placed in foster care due to DV was 42.7% greater for April, 2020 than for April, 2019 while the percentage of youth exposed to emotional neglect was lower for April, 2020 (23.6%) than for April, 2019 (27.6%). |

| Rapoport, et al., 2020,48 United States. | “To assess associations between the pandemic public health response and the number of allegations of CAN”.48(p1) | The number of CAN allegations received monthly by NYC's Administration for Children's Services (2020) (n=4562 March 2020, n=2806 April 2020, n=3474 May 2020). Descriptive study. |

Child maltreatment. | Maltreatment allegations, stratified by reporter type (e.g., mandated reporter, education personnel, or healthcare personnel), as well as the number of Child Protective Services investigations warranting child welfare preventative services. | Fewer allegations of child maltreatment were reported than expected in March (-28.8 %, deviation: 1848, 95 % CI: [1272, 2423]), April (-51.5 %, deviation: 2976, 95 % CI: [2382, 3570]), and May 2020 (-46.0 %, deviation: 2959, 95 % CI: [2347, 3571]). Significant decreases in child maltreatment reporting were also noted for all reporter subtypes examined for March, April, and May 2020. Fewer CPS investigations warranted preventative services than expected in March 2020 (-43.5 %, deviation: 303, 95 % CI: [132, 475]). |

| Whelan, et al., 2020,49 United States. | “To analyze the impact of COVID-19 and Stay-at-Home orders on CA, neglect and exposure to DV filings using the Oklahoma State Court Network”.49(p2) |

Charges issued for CAN from 01/01/2010 through 06/30/2020 in the Oklahoma State Court Network (n=87, 100, 83, 80, 42, February to June 2002 respectively). Descriptive study. |

Physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and DV. | CA categorized as physical abuse including murder, sexual abuse including indecent or lewd acts, counts of enabling or permitting abuse (by type), neglect, solicitation of a minor, DV in the presence of a minor, failure to report abuse or neglect of a minor, and failure to protect a minor. | Fewer reports of CAN were made since the beginning of the COVID-19 compared to prior. Criminal charges for CAN between February and June 2020 averaged 78.4 (SD=19.4) monthly compared to 98.0 (SD=11.5) in 2019. A reduction in filings of sexual abuse and DV in the presence of a minor of 52.9 % and 71.7 % was observed. Sexual abuse and DV in the presence of a minor both decreased in June, with actual sexual abuse cases from 21.1 to 10 (95 % CI 11.2–31.2) and actual DV from 42 to 12 (95 % CI 24.9–59.9). |

| Chong, et al., 2020,50 Singapore. | “To study the impact of COVID-19 on the utilization of pediatric hospital services including emergency department (ED) attendances, hospitalizations, diagnostic categories, and resource utilization in Singapore”.50(p1) | Children aged 0 - 18 years (n=58367) seen in the ED. Descriptive study. |

Physical CA. | The SNOMED-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) for ED diagnoses and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD 10-AM) diagnostic codes for inpatient diagnoses were used. Components of the local triage system were used which are similar to the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. | A total of 226 children were diagnosed with CA-related injuries during the study period. While the mean number remained constant at about 1 per day throughout the pandemic, these children constituted a greater proportion of children seen during lockdown (44, 0.5%) and post-lockdown (79, 0.6%) compared to pre-lockdown levels (36, 0.2%) (p < 0.001). |

| Holland, et al., 2021,51 United States. | “To examine changes in US ED visits for mental health conditions, suicide attempts, overdose, and violence outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic”.51(p1) | The study includes data from the EDs (n=3119 in 2019 and 3598 in 2020). Descriptive study. |

Suspected CAN (SCAN). | SCAN ED visit counts and rates. | ED visits for SCAN exhibited a more pronounced decrease than overall ED visits between March 15 and May 17, 2020 (range, 30.8%-50.7%). There was a decrease of 57% of SCAN compared to the same period in 2019 (n = 452 in 2020 vs 1052 in 2019). |

| Kaiser, et al., 2021,52 United States. | To compare the volume and severity of child physical abuse encounters in children's hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic to that of previous years | The volume of CPA encounters from January 1 to August 31, 2020, was compared to that of the same timeframe in previous years (2017–2019) to understand overall trends (multiple n's for potentially overlapping CAN observations, ranging from 12-1267). Retrospective cohort study. |

CPA. | Change in volume of encounters in which CPA was diagnosed, defined by using International Classification of Diseases. Secondary outcomes included markers of CPA severity: intensive care unit use, number of injuries (a higher total is more severe), injury type, hospitalization resource intensity scores for kids, and in-hospital mortality. | There was a sharp decline in the all-cause, overall volume of ED and inpatient encounters in children's hospitals in March of 2020. When comparing trends in the volume of CPA encounters in 2020 to that of previous years, a significant decline was also found (263.4 cases [95% confidence interval: 291.8 to 235.9]. |

| Swedo, et al., 2020,53 United States. | "To examine national trends in ED visits for suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect during January 6, 2019–September 6, 2020, the period before and during the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic”.53(p2) | Visits were included if the ED provider or facility documented suspected or confirmed physical, sexual, or emotional abuse or physical or emotional neglect of a child or adolescent aged <18 years by a parent or other caregiver (n's not provided). Descriptive study. |

Physical, sexual, emotional abuse, or physical/emotional neglect of a child. | Suspected or confirmed physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; or physical or emotional neglect as perpetrated by parents, caregivers, or an authorized custodian of the child. Acts of violence perpetrated by peers, siblings, or intimate partners are excluded from the CAN definition. | The total number of 2020 ED visits for CAN began decreasing to below the number of visits that occurred during the corresponding 2019 pre-pandemic period in March 15–March 22. At the same time, the proportion per 100,000 ED visits began increasing above the proportion seen during the corresponding period in 2019. During the 4-week period following the early pandemic nadir (March 29–April 25), the number of ED visits related to CAN among children and adolescents aged <18 years averaged 53% less than the number that occurred during the corresponding period in 2019 (March 31–April 27). The number of ED visits related to CAN was lower during this period in 2020, compared with visits during the corresponding period in 2019 for every age group, with the largest proportional declines in the number of visits by children aged 5–11 years (61%). The percentage of ED visits related to CAN ending in hospitalization increased significantly among children and adolescents aged <18 years, from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020 p<0.001). |

| Hamadani, et al., 2020,54 Bangladesh. |

“To determine the immediate impact of COVID-19 lockdown orders on women and their families in rural Bangladesh”.54(p1) | Mothers (or female guardians) of children enrolled in the Benefits and risks of iron interventions in children were contacted by telephone to complete a questionnaire (n=2424). Interrupted time-series study design. |

IPV: emotional, physical, and sexual violence. |

IPV questions were based on the WHO multi-country survey tool, and specifically addressed emotional, physical, and sexual violence by the woman's husband since the last days of March 2020. | Among mothers, emotional violence (insult) was reported by 19.9% of of which 68.4% reported an increase since lockdown; humiliation was reported by 8.9%, of which 66.0% reported an increase; intimidation was reported by 13.5% of which 68.7% reported an increase; physical violence was reported by 6.5%, of which 56% reported an increase; and sexual violence was reported by 3.0%, of which 50.8% reported an increase. |

| Kimura, et al., 2021,55 Japan. | “To examine the relationships between changes due to COVID-19 pandemic and the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms among mothers of infants and/or preschoolers in Japan”.55(p1) | Women aged 20–49 years and had at least one young child (0–6 years; n=2286). Longitudinal prospective follow-up. | IPV: physical and emotional abuse. | Whether a respondent's husband/partner was violent towards them was assessed as follows: ‘Between March to May 2020, my husband/partner shouted at me more often’ and ‘Between March to May 2020, my husband/ partner was violent with me’. If the participant responded to both or either one with ‘yes’, we treated it as ‘yes=1’, and if the participant responded ‘no’ to both, we treated it as ‘no=0’. | 54 (2.4%) participants reported an increase in partner aggression during the pandemic. |

| Mahmood, et al., 2021,56 Iraq. | “To assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender-based violence by comparing the prevalence of spousal violence against women before and during the COVID-19 related lockdown periods”.56(p1) | Married women aged 18 years and older and residing in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq completed the online survey (n=346). Cross-sectional. |

IPV: physical, emotional, and sexual violence. | A 30-item survey examining emotional abuse, physical violence, sexual violence, severity of injuries, and frequency of children witnessing violence. | The prevalence of any violence significantly increased from 32.1% to 38.7% during lockdown (p = .001). The prevalence of emotional abuse (29.5% to 35.0%, p = .005) and physical violence (12.7% to 17.6%, p = .002) significantly increased during lockdown. Being physically forced to have sexual intercourse significantly increased during lockdown (6.6% to 9.5%, p = .021). A higher proportion of violence occurred in front of children during the two months preceding the lockdown (13.0%) than the lockdown period (10.7%), but this difference was not statistically significant. |

| Malkawi, et al., 2021,57 Jordan. | To investigate “reported mental health and changes in lifestyle practices among Jordanian mothers during COVID-19 quarantine”. 57(p1) | Mothers who had at least one child between the ages of 4–18 years, mothers’ ages ranging from 20 to 60 years, living in Jordan, of any nationality, and able to read and write (n=2103). Cross-sectional. |

DV. | Domestic violence was measured by question included in the lifestyle change section |

An increase of 27.4% in DV at home was reported. |

| Rodriguez, et al., 2021,58 United States. | “The goal of the first study was to determine whether parents’ economic concerns, worries, and loneliness were significantly associated with perceived increases in adverse parenting during the pandemic. In the second study, mothers participating in a longitudinal study reported on their CA risk and parenting during the pandemic”.58(p3) | Study 1: Parents of at least one child who was 12 years of age or younger (n=405). Cross-sectional. Study 2: Mothers enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study in the Southeast U.S. (n=119). Longitudinal prospective cohort. |

Verbal, physical, and emotional abuse/neglect. | Emotional neglect was measured using one item from the parental neglect subscale of the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale CTSPC, and CA risk was assessed via the Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 and the Brief Child Abuse Potential Inventory. |

Study 1: 20.3% of parents indicated increased use of discipline; 5.3% reported they spanked or hit more than usual; 24.9% indicated yelling/ screaming more; 30.7% indicated they had more conflicts with their children; 4.9% indicated they had to leave their children alone more; 12.6% indicated they used harsh words toward their children more often; and 26.7% indicated they had engaged in emotional neglect. Study 2: Only 3% of mothers indicated they were hitting more often (either “agree” or “strongly agree”), but 33.3% reported more yelling, 34.9% reported more conflict, and 11.9% reported speaking more harshly. 7.5% of mothers reported leaving their children alone more often, 1.8% reported more difficulty feeding their children, and 1.8% reported showing less love toward their child since the pandemic began. |

| Saji, et al., 2020,44 India. | “To study the social impact of post-COVID-19 lockdown in Kerala from a community perspective”.41(p1) | The study information was collected from families in total from the 14 districts of Kerala, India, during the lockdown period (n=700). Cross-sectional. |

DV. | Data was collected using a pilot-tested structured questionnaire via a chain-referral procedure in which participants recruit one another, akin to snowball sampling. | The survey picked up an increase in the prevalence of DV (13.7%) during the lockdown period. |

| Shah, et al., 2021,41 India. | "To assess the impact of lockdown on children with ADHD, and their families”.41(p1) | Parents of children diagnosed with ADHD, who were actively following up before the lockdown, were contacted by phone (n=80). Cross-sectional. |

CAN. | Questionnaire designed to assess the behavior of children with ADHD and their parents during the ongoing lockdown period. |

There was an increase in shouting at (43.8%), verbal abuse (25%), and punishing the child (27.1%). |

| Sharma, et al., 2021,59 India. | “To find out the prevalence of DV and coping strategies among married men and women during lockdown in India”.59(p2) | Married men and women across the country (n=96). Cross-sectional. |

DV (physical, emotional, sexual, verbal, and financial abuse). | DV was defined as “any act by partner or family member residing in a joint family which harms or injures or endangers the safety and well-being of the victim as defined under the protection of women from domestic violence act, 2005.” (p.2) The forms of abuse included in DV are physical, verbal, sexual, and financial abuse. The perpetrators of the DV could be the partner or other family members. | Out of 94 study participants, about 7.4% (n=7) had faced DV during lockdown. Out of these 7 participants, about 85.7% (n=6) reported increased frequency of DV during lockdown. The most common type of violence which was reported to be increased during lockdown was verbal violence (57.1%, n=4). |

| Tierolf, et al., 2021,60 Netherlands. | “To gain insight by a mixed-method study on what has happened during the lockdown within families who were already known to social services”.60(p1) | Families recruited before the pandemic (n=159), and families recruited during the lockdown (n=87) through child protection services including parents with children between 3 and 18 years of age, and children aged between 8 and 18 years of age. Cross-sectional. |

Physical, sexual, emotional abuse/neglect, and CAN. | For measuring the violence within the families, the Revised CTSPC & Revised Conflict Tactics Scale-2 were used. | No difference was found in violence between families who participated before and after the lockdown. The level of violence is still high in most families. |

Note: (S)CAN = (Suspected) Child Abuse and Neglect; CA = Child Abuse; CPA = Child Physical Abuse; CTSPC = Conflict Tactics Scale Parent-Child; DV = Domestic Violence; ED = Emergency Department; IPV = Intimate Partner Violence.

Factors associated with family violence occurrence

Group 2 contains studies examining factors associated with family violence during the pandemic. High parental stress was associated with increased family violence in two studies from the United States,61,63 and also observed when grandparents were kinship caregivers in India.68 Also in the United States, parental burnout was associated with an increased occurrence of CAN42 and parental perceived social isolation was associated with increased probability of parents physically and emotionally abusing their children, including: “shouting, yelling, or screaming; using more discipline; having more conflicts with their child(ren) than usual; and spanking or hitting their child(ren) more often than usual”.65(p5) Pinchoff et al.’s66 study from Kenya identified family tension, combined with arguing, violence, and fear of being harmed, as associated with increasing family violence. Grandparents’ mental distress as measured via a general mental health scale, was associated with increased use of corporal punishment, psychological maltreatment toward children, and neglectful caregiving.68 Parental depression was also associated with psychological maltreatment toward children in the United States.64 Use of corporal punishment was associated with parents’ report of struggling to discuss issues related to COVID-19 with their children, whereas greater confidence in managing the health preventative measures of COVID-19 restrictions with their children was associated with reduced use of corporal punishment in China.67

Occupational and/or financial losses during the pandemic were also associated with the occurrence of family violence in four studies, by increasing the risk for: verbal and emotional abuse for all family members and children witnessing family violence in Germany;62 psychological maltreatment toward children in the United States;64 severe and very severe physical assaults towards children in China;67 and household tension and violence in Kenya.66 Employment change was associated with increased emotional neglect and occurrences of spanking or slapping children in Japan.65 See Table 5 for details.

Table 5.

Characteristics of included studies examining factors associated with family violence during the pandemic (n=9).

| Authors, Year, Country | Objective and Hypotheses | Participants and study design | Type of violence | Measures | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bérubé, et al., 2020,61 Canada. | “To examine parents’ reports on the response their children received [from them] to their needs during the COVID-19 crisis”.61(p1) | Parents of children aged 0 and 17 years (n=414). Cross-sectional. |

Neglect. | Cognitive and Affective Needs scale, the Security Needs scale, and the Basic Care Needs scale. | Parents with high levels of parental stress related to parent-child interactions associated with changes required to manage COVID-19 protocols (e.g. masking) also reported less response to their child's cognitive and affective needs than those with lower levels of parental stress (F (1,317) = 23.4, p 4.59, SD = 0.46, respectively). |

| Calvano, et al., 2021,62 Germany. | “To generate representative data on pandemic-related stress, parental stress, parental subjective and mental health, and the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and to describe risk factors for an increase in ACEs”.62(p1) | Parents of underage children (n=1024). Cross-sectional. | Verbal emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, nonverbal emotional abuse, and children witnessing DV. | Pandemic Stress Scale, the Parental Stress Scale, general stress, patient mental health, subjective health, ACEs, and positive and negative experiences during the pandemic. | 6.5% (n=66) of parents reported on their children's lifetime occurrence of severe stressful life experiences including violence, abuse, or neglect. Of these, 34.8% reported an increase in occurrence during the pandemic (17.6% no change, 47.5% decrease). The highest lifetime ACE occurrence was reported for children witnessing DV (n=332, 32.4%) and for verbal emotional abuse against the children (n=332, 32.4%). There were few reports of sexual abuse (n=14) and physical neglect (n=11). Across the subtypes, 27.1–46.2% of cases reported no change in occurrence and that in 11.6−34.3% of cases, a decrease was reported. 48.4% of the families with job losses during the pandemic reported an increase in witnessing DV (p=0.013), and 62.1% reported an increase in verbal emotional abuse (p=0.024). In families reporting significant financial losses during the pandemic, 53.0% reported an increase in verbal emotional abuse (p=0.021). |

| Chung, et al., 2020,63 Singapore. |

“To yield better understandings of the effects of COVID-19 on parents and their parenting”.63(p4) | Parents at least 18 years old, who lived in Singapore as citizens or permanent resisdents with at least one child 12 years or younger (n=258). Cross-sectional. |

CA, verbal emotional abuse, physical abuse, and emotional abuse. | Coronavirus Impacts Questionnaire (financial impact, resource impact, and psychological impact), the Parental Stress Scale, and parenting outcomes (harsh parenting behaviors and parent-child relationship closeness). | Parents who were more impacted by COVID-19 experienced more parenting stress (b=.22, p<.001) than those who felt they were less impacted by COVID-19, and parents who experienced more parenting stress indicated that they had used more harsh parenting (b=2.63, p< .001). |

| Lawson, et al., 2020,64 United States. | To investigate “factors associated with child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, including parental job loss, and whether cognitive reframing moderated associations between job loss and child maltreatment”.64(p1) | Parents of 4 to 10-year-olds recruited from Facebook ads and from Amazon Mechanical Turk (n=342). Cross-sectional. |

Psychological maltreatment and physical abuse. | The Conflict Tactics Scale Parent-Child version (CTSPC) was used to determine whether parents psychologically maltreated and physically abused their children within the past year and within the past week during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

Parents who lost their jobs (OR =4.86, CI95%: [1.19, 19.91], p =.03) and were more depressed (OR =1.05, CI 95% [1.02, 1.08], p <.01) were more likely to psychologically maltreat during the pandemic. |

| Lee, et al., 2021,65 United States. | To examine “the association of parents’ perceived social isolation and recent employment loss to risk for child maltreatment (neglect, verbal aggression, and physical punishment) in the early weeks of the pandemic”.65(p1) | AParents with at least one child living at home between the ages of 0–12 years (n=555). Cross-sectional. |

Physical, verbal, and emotional neglect/abuse. | CTSPC items were used to assess risk for physical neglect, emotional neglect, verbal aggression, and physical abuse. To measure increases in parental neglect and discipline since COVID-19, parents were asked to report: “Since approximately 2 weeks ago, when the Coronavirus/COVID-19 global health crisis began:” “I have increased the use of discipline with my child(ren)”; “I have yelled at/screamed at my child(ren) more often than usual”; “I have had more conflicts with my child(ren) than usual”; “I have had to leave my child(ren) home alone more often than usual” and “I have spanked or hit my child(ren) more often than usual” (0=no, 1=yes, 2=not applicable). | A one unit increase in parental perceived social isolation was associated with a 71% increase in the odds of parents physically neglecting their children; an 84% increase in the odds of emotional neglect; a 103% increase in the odds of shouting, yelling, or screaming; a 55% increase in the odds of parents using more discipline; a 77% increase in the odds of parents yelling or screaming at their child(ren) more often than usual; a 92% increase in the odds of parents having more conflicts with their child(ren)than usual; a 132% increase in the odds of parents leaving their child alone more often than usual; and a 124% increase in the odds of spanking or hitting a child(ren) more often than usual. Experiencing an employment change was associated with a 151% increase in the odds of emotional neglect and with a 275% increase in the odds of spanking or slapping. |

| Manja, et al., 2020,42 Malaysia. | “To discover the impact of parental burnout during Movement Control Order”.42(p5) | Parents that were affected by Movement Control Order 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (n=158). Cross-sectional. |

Neglect, verbal violence, and physical violence. | Parental Burnout Inventory including assessment of parental burnout, neglect and violence | Parental burnout significantly associated with neglect and violence. (p<0.001). |

| Pinchoff, et al., 2021,66 Kenya. | “To assess the short-term economic, social, and health effects of COVID-19 and related mitigation measures among a prospective, longitudinal cohort of households sampled from five of Nairobi's informal settlements, with a focus on disproportionate burden placed on women”.66(p3) | Households across five informal settlements in Nairobi, sampled from two previously interviewed cohorts (n=2009). Prospective longitudinal cohort. |

Arguing, tension, household violence, or fear that partner would harm them due to COVID-19. |

Questions regarding social and economic effects on households, for example, loss of employment, skipping meals, household costs, and gender-based violence or tensions experienced in the household. |

In May, households reported more tension, arguing, violence, or fear that partners would harm them. In fully adjusted models, women, married and/or cohabiting couples, and those who reported lost income were more likely to report concerns regarding household tension and violence. |

| Wong, et al., 2021,67 China. | “To investigate whether job loss, income reduction, and parenting affect child maltreatment”.67(p1) | Randomly sampled parents aged 18 years or older who had and lived with a child under 10 years old in Hong Kong between May 29 to June 16,2020 (n=600). Cross-sectional. |

Physical and emotional abuse. | The CTSPC was used to determine psychological aggression, nonviolent disciplinary behaviors (corporal punishment), severe physical assault, and very severe physical assault. | Income reduction was significantly associated with severe (OR = 3.29,95% CI = 1.06, 10.25) and very severe physical assaults (OR = 7.69, 95% CI = 2.24, 26.41) towards children. Job loss or large income reduction were also significantly associated with severe (OR= 3.68,95% CI = 1.33, 10.19) and very severe physical assaults (OR = 4.05, 95% CI = 1.17, 14.08) towards children. Income reduction (OR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.53) and job loss (OR = 0.47,95% CI = 0.28, 0.76) were significantly associated with less psychological aggression. Exposure to IPV between parents was significantly associated with all types of child maltreatment. Having higher levels of difficulty in discussing COVID-19 with children was significantly associated with more corporal punishment (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.05,1.34), whereas having higher level of confidence in managing preventive COVID-19 behaviors with children was negatively associated with corporal punishment (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.76, 0.99) and very severe physical assaults (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.58, 0.93). |

| Xu, et al., 2020,68 United States. | “To examine (1) the relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting practices, such as psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors towards their grandchildren during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (2) whether grandparent kinship caregiver's mental health is a potential mediator between parenting stress and caregivers psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors”.68(p1) | Grandparent kinship caregivers (n=362). Cross-sectional. |

Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. | Psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors were measured through the CTSPC. Child and grandparent Kinship caregivers’ characteristics. Mental health via Mental Health Inventory-5 scale. Parenting stress via the Parent Stress Index. | Grandparent kinship caregivers’ high parenting stress and low mental health were associated with more psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful parenting behaviors during COVID-19. Grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health partially mediated the relationships between parenting stress and their psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors. |

Note: (S)CAN = (Suspected) Child Abuse and Neglect; CA = Child Abuse; CPA = Child Physical Abuse; CTSPC = Conflict Tactics Scale Parent-Child; DV = Domestic Violence; IPV = Intimate Partner Violence.

Discussion

This rapid review of COVID-19 literature published up to the one-year anniversary of the pandemic, addressed three objectives including investigation of the occurrence of family violence, identifying associated factors (e.g. risks), and deriving relevant recommendations. This latter focus distinguishes the review from other reviews on the topic. In examining global family violence occurrence during the COVID-19 pandemic, findings from eight of the ten reviewed studies employing official records (i.e. police, justice, and ED) revealed decreases in family violence including CAN. In contrast, all studies that relied on self-report data from families in households showed an increase in family violence including IPV and CAN. In other words, depending on the data source, either a decrease or an increase in the occurrence of family violence was revealed. This review also showed that increased family tension and child witnessing of family violence was common in the self-report data. Factors including parental stress, burnout, social isolation, family tension, mental distress such as depression, challenges managing public health restrictions with children, and occupational and financial losses/changes during the pandemic were related to the increases in family violence from community studies conducted worldwide during the pandemic.

To addresss family violence during the pandemic, six main types of recommendations were made in the reviewed literature, including: (1) adapting/reinforcing service delivery models to manage the challenges arising from COVID-1944,45,51,64; (2) improving training of health professionals and the public46,48,50,60,61,67; (3) policies to prevent family violence and to assist those experiencing it42,49,52,54,64,66,67,68; (4) improvement to care and other services52,54,55,58,62,63,65,68; (5) using a proactive and preventative public health lens47,53,55,57,58,59; and (6) focusing on future research.41,43,46,53,55,56,58,59,65,67,68 The most common recommendation in the reviewed studies was the need for digital access to services and increased training for educational or health professionals to utilise online platforms to identify signs of family violence. Consistent with the findings of another review,69 an additional recommendation was for health services to adopt measures and interventions to prevent family violence and treat victims in the context of pandemic public health restrictions. Reviewed studies also recommended enhanced training and funding for mental health and social service providers to prevent and treat family violence, especially in the context of pandemics.70 See Table 6 for details.

Table 6.

Recommendations and examples.

| Recommendation | Examples |

|---|---|

| Adapting/Reinforcing Service Delivery Models |

|

| Training of Health Professionals and the Public |

|

| Policies as a means to prevent family violence as well as assist families |

|

| Improvements to care and other services |

|

| A proactive, preventative, and public health-oriented approach |

|

| Future Research |

|

Findings addressing the first objective are supported by other reviews of global literature2,4,71,72 that observed mixed findings in studies relying on official records, and trends toward increases in family violence in studies that relied on self-report. In our review, most studies on families with parent, guardian, or kinship care provider self-reports, conducted in Bangladesh, India, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, and the United States, revealed an increase in family violence compared to their pre-pandemic experiences.41,44,54,55, 56, 57, 58, 59 While an increase in family violence reports via official ED, justice, and police records may have been expected during the pandemic,72 the decline observed in this review may be explained by three key factors, underpinned by underreporting or reduced access to services as suggested by three related reviews.2,4,70 First, due to the pandemic's unpredictability, health services were forced to adapt quickly to manage routine care. This may have made it difficult for victims to know where to access help.8,9 Second, victims of IPV or CAN may have been reluctant to seek help due to fears of: (1) contracting the virus by accessing health services, or (2) the perpetrator discovering the victim's attempts to seek help. Kourti et al.’s review further suggested that increased proximity of perpetrators to victims under pandemic health restrictions such as work-from-home requirements may have increased coercive control and prevented victims’ help seeking.4 Interestingly, they also noted greatest increases in family violence in the first week after lockdown, with a decline thereafter, attributing the decline to victims finding ways to access help and escape family violence.4 Third, pandemic restrictions typically reduced children's in-person contacts to those solely within their household, which eliminated opportunities for outsiders to notice CAN.48 Typically, health care providers and educators account for the most CAN reports, for example identifying one-third of CAN cases in the United States in 2019.21 In Katz et al.’s review that compared nations’ responses to CAN in the context of COVID-19, in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa, they noted that official reports of CAN decreased and attributed this to the closures of schools and reduced contact with teachers.73 Kourti et al.’s4 review regarded school attendance to be protective against CAN in the context of COVID-19, highlighting the importance of teachers and other professionals to children's protection, as children do not typically report CAN.74

Of the studies examining IPV, emotional abuse was most common, a pattern reflected in other literature75 and in Kourti et al.’s review.4 Emotional abuse has been identified as a potential precursor for physical and verbal abuse,76 so not surprisingly these were also reported frequently in the context of IPV in the reviewed studies. Only three of the studies in our review that included descriptive data focused on CAN; however, all three reported an increase in all types of violence against children.44,58 Yelling and verbal abuse were the most prominent types of violence observed, followed by physical violence. Verbal abuse or yelling reflect a component of psychological maltreatment, a form of family violence that has recently been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reflecting its potential impact on health outcomes.76

With respect to factors contributing to family violence, social isolation was identified as a risk factor for IPV,31 especially for women,77 in this review and others.5, 78 Hoome confinement isolated victims with their perpetrators, resulting in increased violence, but reduced reports.5 Parental perceived social isolation was associated with an increased odds of parents physically and emotionally neglecting their children.49 Social connection has been identified as a vital aspect of human well-being by promoting healthy behaviors, increasing feelings of connection, and benefitting physiological functioning.79 Conversely, social isolation is linked to mental distress79 potentially impeding parents’ abilities to care for their children.30 Negative feelings due to perceived social isolation in parents may increase the risk for CAN. Aligned with our findings, previous research and other reviews related to COVID-19 impacts identified family mental health problems, couple distress30 and parental behavioral change as predictors for CAN.5 Many recommendations (see Table 6) suggested means to address social isolation and concomitant mental health, couple relationship and parenting behavior changes such as delivering home-based services45 and training in and utilisation of text-message and digital interventions.48,60

Parental stress was also identified as a risk factor for increased family violence,61,63,68 as associated with mental distress, fatigue, and decreased enjoyment when interacting with children, ultimately undermining parental capacity to care for their children under the stress of pandemic conditions.24 Caregiver mental distress such as depression during the pandemic was associated with the use of corporal punishment and psychological maltreatment toward children,68 a pattern commonly seen in other studies.30 Persistently high levels of stress may also lead to parental burnout, an additional factor associated with CAN.42 With daycares, schools, and recreational programs shutting down, the demands associated with parenting increased significantly during the pandemic, increasing the risk for burnout.28 Our review and others’ revealed that the association between parental stress or burnout with CAN remained present even when taking into account socioeconomic demographics.4,42 Our findings are also supported by Silva's scoping review80 of impacts of COVID-19 on violence against children that identified parental stress and anxiety, economic stress, and financial insecurity as risk factors. Mittal et al.’s review also revealed that mental distress in partners increases the risk for IPV against women.77

Occupational and financial losses during the pandemic were also related to CAN, including an increase of children witnessing IPV and experiencing verbal emotional abuse,62 increased psychological maltreatment,64 severe and very severe physical assaults,67 and household tension and violence.66 Employment change was associated with increased CAN,65 findings that are supported by another review5 and literature81 specifically showing that economic pressures on parents undermine developmental outcomes in children, as a result of decreased caregiving capacity. Another review also identified many of the same factors that contribute to family violence including lost income and employment.2 Recommendations suggested that policies should address socio-economic factors,42 including not only financial relief,52,54,68 but also provision of low-barrier, easily accessible, psychological support to bolster mental health and effective coping strategies.64

As a mental health crisis has emerged concomitantly with the COVID-19 pandemic82 and poorer parental mental health acts as a risk factor for CAN,30 recommendations point to the urgent need for enhanced mental health services and supports for parents and families during and following the pandemic to prevent CAN.52,55,58,62,63,65 Supporting parents’ ability to manage public health restrictions’ impacts on their children (e.g. masking, social distancing) is also key, as decreased parental comfort with restrictions may increase corporal punishment.54 Only one study suggested that increased CAN was related to worsening children's behavior (i.e. increased ADHD symptoms)44 whereas the others were unrelated to children's behaviors.42,61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 Enabling parents to effectively communicate and manage the behavior changes imposed on children, in the context of pandemic restrictions, may help prevent CAN.67

Consistent with Pereda et al.’s theoretical review3 of socioecological models, parental stress, burnout, mental health and depression, comfort in managing COVID-19 measures and children's behaviors, and perceived social isolation,42,61,63,65,68 all reflective of individual-level factors, along with environmental factors such as occupational or financial losses during the pandemic,62,64,65,67 were associated with family violence. There also appears to be interconnections between individual and environmental factors as contributors to family violence (i.e. occupational and financial losses during the pandemic led to increased parental stress). This highlights the importance of considering the co-occurrence of interconnected risk factors for family violence in designing prevention and treatment efforts,31 such as mental health services for internal factors and governmental financial supports for external factors.

Consistent with results of two other reviews,2,70 focusing on strategies and interventions to support families and prevent violence between partners and toward children affected by pandemics, appears essential. Longitudinal studies should be performed to identify not only the effects of COVID-19 on family violence during the pandemic, but also the long-term consequences to intimate partners’ and children's health and development. Research could identify targets for future interventions to limit/attenuate negative impacts of pandemics to promote higher family functioning and optimal mental and physical health outcomes of all family members. Studies were not found that examined the effectiveness of interventions or policies to reduce family violence in the context of the pandemic, and would be warranted in future.